Highlights

-

•

An integrated campaign of skin screening and mass drug administration is feasible.

-

•

Cost savings may not be a guaranteed outcome of an integrated campaign.

-

•

People in remote areas appreciate a comprehensive service package in a campaign.

-

•

Campaign quality can be improved with better planning, training, and supervision.

Keywords: Campaign cost, Integration, Skin related neglected tropical disease, Mass drug administration, Peopulation acceptance

Abstract

Background

The World Health Organization advocates integrating neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) into common delivery platforms to combat them in resource-constrained settings. However, limited literature exists on the benefits of integration. This study examines the feasibility and impact of adding skin screening to a mass drug administration (MDA) campaign in Côte d'Ivoire.

Methods

In June 2023, the Ministry of Health and Public Hygiene of Côte d'Ivoire piloted screening for skin-related NTDs alongside a national MDA campaign targeting soil-transmitted helminthiases and schistosomiasis. Two districts, Fresco and Koro, were selected for the pilot. The study applied both quantitative and qualitative assessments. The quantitative aspect focused on campaign costs and outputs, using an ingredient approach for costing. The qualitative evaluation employed an empirical phenomenological approach to analyze the campaign's operational feasibility and appreciation by stakeholders.

Findings

MDA activities cost $0·66 per treated child and skin screening $0·62 per screened person, including medical products. The MDA campaign exceeded coverage targets in both districts, whereas skin screening coverage varied by locality and age group. Both the service delivery team and the beneficiaries expressed appreciation for the integrated campaign. However, opportunities for improvement were identified.

Conclusion

Integrating MDA and skin NTD screening proved operationally feasible in this context but had not recorded cost-saving effects. The performance of the MDA campaign was not negatively affected by additional skin screening activities, but effective integration requires thorough joint planning, strengthened training, and proper supervision.

Introduction

Implementing integrated service delivery for communities living in the same areas and facing multiple neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) is advocated as a key approach in the fight against NTDs by the World Health Organization (WHO) [1,2]. Two groups of NTDs are often targeted for integrated delivery of interventions: NTDs requiring preventive chemotherapy (PC) through mass drug administration (MDA) campaigns; and skin-related NTDs (skin NTDs) requiring similar control strategies [[3], [4], [5], [6], [7],8].

Although MDA and skin screening activities against NTDs often target the same populations or communities, integration across both types of campaigns is less common. As consequence, published studies assessing both the cost and the impact of an integrated campaign are scarce. The current study aims to fill that gap by incorporating skin NTD screening into a planned MDA campaign against soil-transmitted helminthiases and schistosomiasis in two districts (Fresco and Koro) in Côte d'Ivoire.

The study aimed to answer three questions: (1) What are the costs and outputs of this integrated campaign? (2) Is such integration feasible? and (3) How do the stakeholders appreciate such integration? The findings from this study are expected to provide valuable insights for decision-makers on the conditions under which the integration of different public health interventions into a single campaign could be advantageous.

Methods

Study design

The pilot study was carried out in Côte d'Ivoire. In June 2023, the PC program planned a nationwide MDA campaign to distribute albendazole and praziquantel to school-aged children (SAC) of 5-14 years old as a measure to control the prevalence of soil-transmitted-helminthiases and schistosomiasis among the targeted population.

The two districts covered by the planned MDA campaign, Fresco and Koro, were selected to add skin screening activities during their respective MDA campaigns.

The choice was guided by several factors: (1) both districts were endemic for most NTDs with cutaneous manifestations; (2) they had different vegetation, with Fresco in the southern forest zone and Koro in the northern savannah zone; and (3) both districts were scheduled for MDA in the same period.

Fresco and Koro health districts were endemic for schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiases. Annual treatment with albendazole was administered in all endemic districts. For schistosomiasis, the treatment protocol varies by disease prevalence. In 2023, Koro received both albendazole and praziquantel, whereas Fresco, not scheduled for treatment, only received albendazole. In both districts, skin screening targeted Buruli ulcer, leprosy, yaws and other skin conditions. Although SAC is the main targeted population, skin screening was also open to all other age groups presented at the campaign.

The campaign was organized during the period when schools were closed, so activities were conducted door-to-door.

Data analyzing approaches

This study encompassed both quantitative and qualitative assessments. The quantitative approach addressed the cost and outputs of the campaign. An ingredient approach was used for costing to reflect the value of resources based on the first-hand data on the consumption of inputs.

The qualitative evaluation employed an empirical phenomenological approach to record and analyze the feasibility and appreciation by beneficiaries and stakeholders of the integrated campaign. Interviewees were selected using purposive sampling; the primary criterion was their active involvement in implementing the integrated campaign.

Results

A total of 50 749 SAC received albendazole for soil-transmitted helminthiases, of whom 21 791 in Koro also received praziquantel concurrently. Community health workers (CHWs) screened 61 344 individuals, of whom 3125 (5%) were referred to nurses for additional diagnosis and treatment. In total, 333 patients with skin diseases were detected.

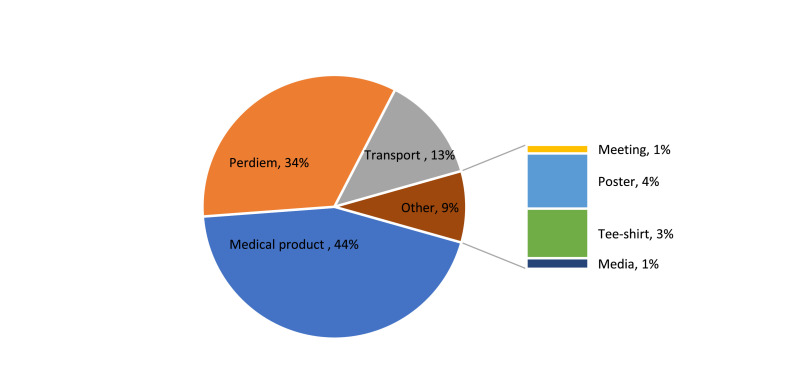

The integrated campaign cost $71 414, including $31 741 for medical products (44%) and $39 673 for operational costs (56%). Among the operational costs, MDA activities cost $16 708(47%) and skin screening cost $22 964 (53%). MDA activities cost $0·66 per child, including medicines, and $0·33 without medicines. Skin screening activities cost $0·62 per person including medicines, and $0·37 without medicines (Table 1). Regarding cost by input, medical products emerged as the primary cost driver, followed by human resources and transportation (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Coverage and costs of the integrated campaign.

| Activity | District | Age group | Targeted population | Reached populationa | Coverage | Total campaign cost |

Cost per person |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical productsb | Operation | Total | Medical products | Operation | Total | ||||||

| MDA | Fresco | 5-14 y | 28,978 | 28,958 | 99.93% (target 75%) | $16,957 | $16,708 | $33,665 | $0·33 | $0·33 | $0·66 |

| Koro | 5-14 y | 20,531 | 21,791 | 106·14% (target 75%) | |||||||

| Total | 49,509 | 50,749 | 103% | ||||||||

| Skin screening | Fresco | <5 y | 13,658 | 3342 | 24% | $14,784 | $22,965 | $37,749 | $0·24 | $0·37 | $0·62 |

| 5-14 y | 28,978 | 25,798 | 89% | ||||||||

| ≥15 y | 55,488 | 8468 | 15% | ||||||||

| Total | 98,124 | 37,608 | 38% | ||||||||

| Koro | <5 y | 13,765 | 3193 | 23% | |||||||

| 5-14 y | 20,531 | 6238 | 30% | ||||||||

| ≥15 y | 42,641 | 14,305 | 34% | ||||||||

| Total | 76,937 | 23,736 | 31% | ||||||||

| Total | 273,185 | 98,952 | 36% | ||||||||

| Grand total | 322,694 | 149,701 | – | $31,741 | $39,673 | $71,414 | $0.57 | $0.70 | $1.28 | ||

“Reached population” for MDA campaign refers to the people having received the drugs; and for skin screening campaign it refers to the people being examined for their skin conditions.

Medical products include the following: for MDA, albendazole and praziquantel; for Skin screening, Dual Path Platform (DPP), rapid diagnostic test (RDT), Azithromycin and other drugs for treatment, medical supplies and consumables.

Figure 1.

Cost distribution by input.

The MDA coverages of 106% in Koro and 99.93% in Fresco exceeded the national coverage average of 92% for the MDA campaign in the same year. The beyond 100% coverage in Koro implies that certain children out of scope may have also received medicines.

For skin screening, a total of 38% and 31% of the targeted populations were screened for skin conditions in Fresco and Koro respectively (Table 1). These coverages are comparable to coverage of 42% by a yaws mapping campaign in 15 health districts in the country in the same year.

For the SAC age group, in Fresco district, proactive efforts in searching the targeted population during MDA activities led to a high skin NTD screening of 89%. Conversely, in Koro district, a misunderstanding of the process during training and insufficient supervision during the campaign resulted in low coverage of skin screening for SAC of 30%.

Appreciation of the campaign was evaluated through individual interviews. The interview guide was organized around two questions: (1) is such integration feasible? and (2) how do the stakeholders appreciate such integration?

A total of 53 in-depth interviews were conducted with 23 nurses, 16 CHWs, 12 community leaders, and two managers of the district health centers.

The interview revealed the following findings: (1) Trainees in both Koro and Fresco appreciated the integrated training. However, another simultaneous nutrition campaign in Koro disrupted the training, causing confusion among interviewees. (2) The targeted population was informed about the campaign but unclear about its purpose. (3) The engagement of CHWs was key to delivering the services in remote area. However, they need close supervision and support from healthcare professionals. In Fresco, CHWs were clear about the objectives and efficiently planned activities. In Koro, CHWs were confused about the campaign process due to overburdened training. (4) The local population appreciated that adults, in addition to children, could receive services during the health campaign. Postcampaign interviews revealed that people continued to request medicines, visited health centers for skin problems, and demonstrated a strong community need and acceptance of treatment for skin NTDs.

Discussion and conclusion

This study explores integrating different interventions into a single campaign, focusing on combining MDA with skin NTD screening. It collected data on outcomes, resource needs, feasibility and acceptance. The campaign identified a high number of skin diseases among children and adults and raised awareness among communities about their skin NTD burden. The MDA campaign's performance remained stable despite concurrent skin screening, thanks to the dedication of CHWs. However, CHWs faced time constraints, highlighting the need to address workload in campaign design.

MDA targeted SAC, while skin screening included other age groups. To avoid overburdening MDA activities, skin screening was conducted only on those who presented for MDA. There was no active effort to screen everyone in the two districts. Consequently, skin screening coverage was low for age groups not targeted by MDA in both districts. The success of the campaign depended on supportive activities such as supervision, training and social mobilization, which required significant financial investment. Supervision, especially by national expert teams, was the largest cost driver, suggesting that enhancing local supervision could reduce costs and improve quality.

The pilot study did not confirm cost savings from integration, aligning with similar findings in the United Republic of Tanzania [9]. One potential reason was the lack of mutual planning on resource use. Effective integration requires joint planning, which was lacking in this pilot study. Nevertheless, the feasibility of the integrated campaign was demonstrated, and community acceptance was high, especially for services benefiting adults. Continued service provision is crucial for treating diseases and building trust.

This study contains the following limitations. (1) Given the lack of a control group, the study could not provide direct evidence of the incremental cost-effectiveness of an integrated campaign versus separate campaigns for MDA and skin NTD screening. (2) Our analysis of the integrated campaign could not distinguish the general challenges, such as rainy season or school closures, faced by both districts. (3) The study did not include any analysis based on sex or gender.

In conclusion, integrating MDA and skin NTD screening is technically feasible and appreciated by the population. Improved planning and training could enhance outcomes and reduce costs. Resource-limited countries should plan integrated campaigns as cohesive projects rather than combining separate activities.

Disclaimer

The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions, or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated

Data sharing statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT in order to improve language and readability. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Declarations of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Funding source

The Anesvad Foundation funded this project, covering the costs associated with integrating skin NTD screening into the Mass Drug Administration campaign at the pilot sites. This funding also supported the entire research project, encompassing study design, field missions, data collection, and analysis.

Ethical approval statement

The study protocol for this research has been approved by the National committee of research ethics (Comité National d’Éthique de la Recherche) of Côte d'Ivoire (199–23/MSHPCMU/CNESVS-km) on 9 October 2023.

Author contributions

X.X. Huang and B.V. Kone: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, visualization, writing – original draft. They have directly accessed and verified the underlying data reported in the manuscript. A.P. Koffi, Y.D. Koffi, M.L. Amoin, B. Kouma, C. Blanche: investigation, validation investigation, resources, methodology and writing – review & editing. K.B. Asiedu, N.R. N’DRI, Y.T. Barogui, A.J.C. AKPA: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, supervision, validation investigation, and writing – review & editing.

References

- 1.WHO Global Neglected Tropical Disease Programme . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2020. Ending the neglect to attain the sustainable development goals: a road map for neglected tropical diseases 2021–2030. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [Google Scholar]; http://apps.who.int/iris

- 2.AFR-RC72-7 . World Health Organization, Regional Office for Africa; Brazzaville, Republic of Congo: 2022. Framework for the control elimination and eradication of tropical and vector-borne diseases in the African region. [Google Scholar]; https://www.afro.who.int/sites/default/files/2022-07/AFR-RC72-7%20Framework%20for%20the%20control%20elimination%20and%20eradication%20of%20tropical%20and%20vector-borne%20diseases%20in%20the%20African%20Region.pdf

- 3.Clements A.C.A., Deville M.-A., Ndayishimiye O., Brooker S., Fenwick A. Spatial co-distribution of neglected tropical diseases in the East African Great Lakes region: revisiting the justification for integrated control. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15(2):198–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02440.x. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2875158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evans D., Mcfarland D., Adamani W., Eigege A., Miri E., Schulz J., et al. Cost-effectiveness of triple drug administration (TDA) with praziquantel, ivermectin and albendazole for the prevention of neglected tropical diseases in Nigeria. Ann Trop Med Parasite. 2011;105(8):537–547. doi: 10.1179/2047773211Y.0000000010. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4089800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cano J., Basáñez M.-G., O’Hanlon S.J., Tekle A.H, Wanji S., Zouré H.G., et al. Identifying co-endemic areas for major filarial infections in sub-Saharan Africa: seeking synergies and preventing severe adverse events during mass drug administration campaigns. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11(1):70. doi: 10.1186/s13071-018-2655-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lo N.C., Bogoch I.I., Blackburn B.G., Raso G., N’Goran E.K., Coulibaly J.T., et al. Comparison of community-wide, integrated mass drug administration strategies for schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis: a cost-effectiveness modelling study. Lancet Global Health. 2015;3(10):e629–e638. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00047-9. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214109X15000479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brady M.A., Hooper P.J., Ottesen E.A. Projected benefits from integrating NTD programs in sub-Saharan Africa. Trends Parasitol. 2006;22(7):285–291. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ending the neglect to attain the sustainable development goals: a strategic framework for integrated control and management of skin-related neglected tropical diseases. World Health Organization; 2022. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240051423.

- 9.Mwingira U.J., Means A.R., Chikawe M., Kilembe B., Lyimo D., Crowley K., et al. Integrating neglected tropical disease and immunization programs: the experiences of the Tanzanian Ministry of Health. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;95(3):505–507. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]