Abstract

Epilepsy, frequently comorbid with anxiety, is a prevalent neurological disorder. Available drugs often have side effects that hinder adherence, creating a need for new treatments. Potassium channel activators have emerged as promising candidates for treating both epilepsy and anxiety. This study aimed to evaluate the potential anticonvulsant and anxiolytic effects of pinacidil, an ATP-sensitive potassium channel activator used as antihypertensive, in rats. Our results indicate that pinacidil at 10 mg/kg (i.p.) fully protected animals from seizures induced by pentylenetetrazol (PTZ) and provided 85.7%, 100% and 100% protection against pilocarpine-induced seizures at 2.5, 5 and 10 mg/kg (i.p.), respectively. Although the 2.5 and 5 mg/kg (i.p) doses did not significantly protect the animals from PTZ-induced seizures, they did significantly increase the latency to the first seizure. Pinacidil also demonstrated mild anxiolytic activity, particularly at 10 mg/kg (i.p), evidenced by increased time spent in the open or illuminated areas of the Elevated Plus Maze (EPM) and Light-Dark Box (LDB) and increased exploratory activity in the Open Filed, EPM and LDB. Pinacidil did not affect locomotor performance, supporting its genuine anticonvulsant effects. This study holds significant medical and pharmaceutical value by characterizing pinacidil’s anticonvulsant and anxiolytic effects and highlighting its potential for therapeutic repositioning.

Keywords: Anxiety; Potassium channels; Drug repositioning; Epilepsy; N-cyano-N'-pyridin-4-yl-N''-(1,2,2-trimethylpropyl) guanidine

Subject terms: Drug screening, Pharmacology

Introduction

Epilepsy is a chronic brain disease defined by neuronal hyperactivity in specific brain circuits, mainly located in the hippocampal region and the prefrontal cortex, causing synchronous, repeated, and self-sustained electrical discharges1,2. Data from the World Health Organization (WHO) show that epilepsy is one of the most common and disabling neurological pathologies, affecting approximately 50 million people worldwide3. Epilepsy commonly appears in comorbidity with anxiety. Both disorders have common neurobiological bases, including imbalance of GABAergic and glutamatergic neurotransmissions. In addition, many anticonvulsants and/or antiepileptic drugs are also anxiolytic and vice versa, depending mainly on the dose used4,5.

Antiepileptic drugs reduce the incidence or severity of epileptic seizures in different types of patients6. A variety of mechanisms have been proposed for the action of antiepileptic drugs, but the most common are those involving the modulation of specific ion channels, the increase in inhibitory neurotransmission mediated by GABA and the attenuation of excitatory glutamatergic neurotransmission7. In this context, ion channels, particularly those voltage-dependent sodium, calcium, and more recently potassium channels, are pivotal in explaining the neuromolecular basis of epilepsies. Consequently, these ion channels have attracted interest as targets for new antiepileptic drugs8.

Potassium channels are membrane proteins assembled of α and accessory subunits9. Voltage-dependent K+ channels prevent the recurrence of the action potential, participating in the repolarization and hyperpolarization of the membrane after alterations promoted by paroxysmal depolarization. Mutations in the genes responsible for the formation of potassium channels cause a decrease in repolarization and produce neuronal hyperexcitability10. Thus, different potassium channels have a great influence on the regulation of neuronal excitability and, therefore, on the development and maintenance of epilepsy. K+ channels of the KCNQ2/Q3, Kv1 and K-ATP types have been increasingly studied as attractive targets for a better understanding of epilepsy and, therefore, for its treatment11,12. ATP-activated K+ channels, also known as K-ATP channels, are composed of four inward-rectifier potassium channel subunits (Kir6), which are surrounded by regulatory subunits called sulfonylurea receptors (SUR)13,14. ATP binds to the ATP-binding cassette located on the SUR subunit. Although SUR is part of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter family, it does not directly transport ions but instead regulates the K-ATP channel by sensing intracellular ATP and ADP levels14. The activity of K-ATP channels is regulated by the intracellular concentration of ATP. An increase in intracellular ATP causes conformational changes in the K-ATP complex, leading to the efflux of potassium ions through the pore-forming Kir subunits13,14.

Pinacidil (Fig. 1) is a commercial K+ channel activator drug currently used as an antihypertensive, acting by peripheral vasodilation without directly affecting cardiac electrical activity. Pinacidil activates ATP-dependent potassium channels that promote potassium outflow and indirectly hyperpolarizes cell membranes, reducing intracellular calcium and causing vascular smooth muscle to relax15,16. On the other hand, this same drug, based on its mechanism of action, can act on both pre- and postsynaptic regions of various regions of the brain, regulating neuronal metabolism and excitability16. Nicorandil is another activator of ATP-dependent potassium channels, belonging to the same family as pinacidil. Recent studies with nicorandil indicate that these ATP-dependent channels act in the control of neuronal excitability, in the control of seizure propagation and in the definition of the seizure threshold. This increases interest in nicorandil and other potassium channel activators, such as pinacidil, in terms of the potential of these drugs for a better understanding of epilepsy and its treatment17. In fact, Acar and co-workers18 showed that pinacidil inhibited spike and wave epileptiform activity induced by intracortical administration of penicillin in anesthetized rats.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structure of Pinacidil.

Source: MedChemExpress, 2024.

Thus, considering the effects of pinacidil on potassium channels, and the involvement of these channels, especially those dependent on ATP in epilepsy and its potential treatment, the aim of this work will be to evaluate the anticonvulsant and anxiolytic activities of different doses of pinacidil using a combination of different experimental models.

Results

Anticonvulsant screening

In the PTZ test, only the 10 mg/kg dose of pinacidil had a significant anticonvulsant effect, protecting the animals 100% against seizures (p = 0.0006) (Fig. 2A). The other doses of 2.5 mg and 5 mg did not significantly protect the animals against score 7 and 8 seizures, as shown in Fig. 2A.

Fig. 2.

Anticonvulsant effect of pinacidil and diazepam against seizures at maximum Racine score (7/8) in Wistar rats (n = 6). (A) % of protected animals on PTZ-induced seizures (B) % of protected animals on Pilocarpine induced-seizures. Bars represent mean ± SD. ***p < 0.001 significantly in Fisher’s exact test.

In the pilocarpine test, pinacidil showed an anticonvulsant effect for all the doses tested. In fact, the doses of 2.5 mg/kg (p = 0.047), 5 mg/kg (p = 0.006) and 10 mg/kg (p = 0.006) showed significant differences compared to 0.9% saline, as illustrated in Fig. 2B. The doses of 2.5; 5 and 10 mg/kg protected the animals against the 7/8 score seizures by 85.7%, 100% and 100% respectively, as shown in Fig. 2B. The protection against seizures offered by DZP (2 mg/kg) was 100% in both the PTZ and pilocarpine tests (Fig. 2A and B).

As for the latency to first seizure in animals not completely protected against seizures, we observed that the time to first seizure was significantly increased in animals treated with pinacidil compared to the saline control group, especially in the PTZ test. In fact, in the PTZ test the time to first seizure was increased by around 3.5 times compared to the saline group for the 2.5 and 5 mg/kg doses of pinacidil (Table 1).

Table 1.

Latency to seizure onset (score 7–8 in Racine Scale) in Wistar rats (n = 6).

| Latency to seizure onset | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saline (0.9%, i.p.) |

DZP (2 mg/kg, i.p.) |

Pinacidil (2.5 mg/kg, i.p.) |

Pinacidil (5 mg/kg, i.p.) |

Pinacidil (10 mg/kg, i.p.) |

|

|

PTZ (80 mg/kg, i.p.) |

150 ± 29 | NA | 529 ± 304 | 527 ± 266 | NA |

| % seizure free | 0% | 100% | 0% | 42% | 100% |

|

Pilocarpine (320 mg/kg, i.p.) |

1416 ± 202 | NA | 1604* | NA | NA |

| % seizure free | 0% | 100% | 86% | 100% | 100% |

All latencies were expressed as means ± SD. NA – Not applied.

Anxiolytic tests

Open field

Except for a slight increase in exploratory activity induced by pinacidil at a dose of 10 mg/kg (i.p.) [F(4,25) = 4.256; p = 0.0092] (Fig. 3B), no other significant anxiolytic effect was observed after the administration of different doses of pinacidil in the Open Field test. In fact, no statistical differences were observed between animals treated with pinacidil at all doses and the saline group in terms of time spent in the central zone of the apparatus [F(4,25) = 15.59; p < 0.0001], as shown in Fig. 3A. There were also no significant differences between the different doses of pinacidil and the saline group regarding rearing and grooming behaviors, as shown in Fig. 3C and D, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Behavioral analysis in Open Field Test in Wistar rats (n = 6). (A) Time spent in central zone; (B) Total exploration time; (C) Total rearing time and (D) Total grooming time. Bars represent mean ± SD. ***p < 0.001 significantly in ANOVA by the Tukey post-test.

Elevated plus maze

As illustrated in Fig. 4A and B, we observed that the 5 and 10 mg/kg doses of pinacidil showed a statistical difference when compared to the 0.9% saline solution. Our results show that the animals treated with pinacidil spent more time in the open arm [F(4,25) = 13.55; p 0.2180] and less time in the closed arm [F(4,25) = 14.81; p = 0.5150] when compared to the saline group. There was also a significant increase in the number of entries of the animals treated with the 5 and 10 mg/kg doses of pinacidil when compared to the saline group (Fig. 4C; Table 2). The number of entries in the closed arm, as shown in Fig. 4D, did not show significant results when comparing the different doses of pinacidil with the saline group. As for the dips, the doses of 5 and 10 mg/kg showed a statistical difference when compared to the saline control group [F(4,25) = 16.83; p < 0.001] (Fig. 4E).

Fig. 4.

Behavioural analysis in Elevated Plus Maze in Wistar rats (n = 6). (A) Time spent in open arm; (B) Number of open arm entries; (C)Time spent in closed arm; (D) Number of closed arm entries and (E) Number of head dips. Bars represent mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 significantly in ANOVA test followed by Tukey post-test.

Table 2.

Percentage of time in open arms after pinacidil administration in Wistar rats (n = 6).

| Percentage of TOA | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animal 1 | Animal 2 | Animal 3 | Animal 4 | Animal 5 | Animal 6 | Mean ± SD | |

| Saline | 21.3 | 7.3 | 22 | 14 | 12.7 | 25 | 17 ± 6.7 |

| DZP | 56.7 | 56.7 | 67 | 53.3 | 40 | 54.7 | 54.7 ± 8.7*** |

|

Pinacidil (2.5 mg/kg, i.p.) |

13.3 | 18.7 | 31.3 | 33 | 22.3 | 16 | 22.4 ± 8 |

|

Pinacidil (5 mg/kg, i.p.) |

23.3 | 44 | 48.3 | 38 | 43.3 | 45 | 40 ± 8.9** |

|

Pinacidil (10 mg/kg, i.p.) |

68.3 | 38.3 | 45.7 | 42.3 | 24.3 | 38.7 | 42.9 ± 14*** |

All data were expressed as means ± SD. **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 significant in ANOVA test followed by the Newman Kells.

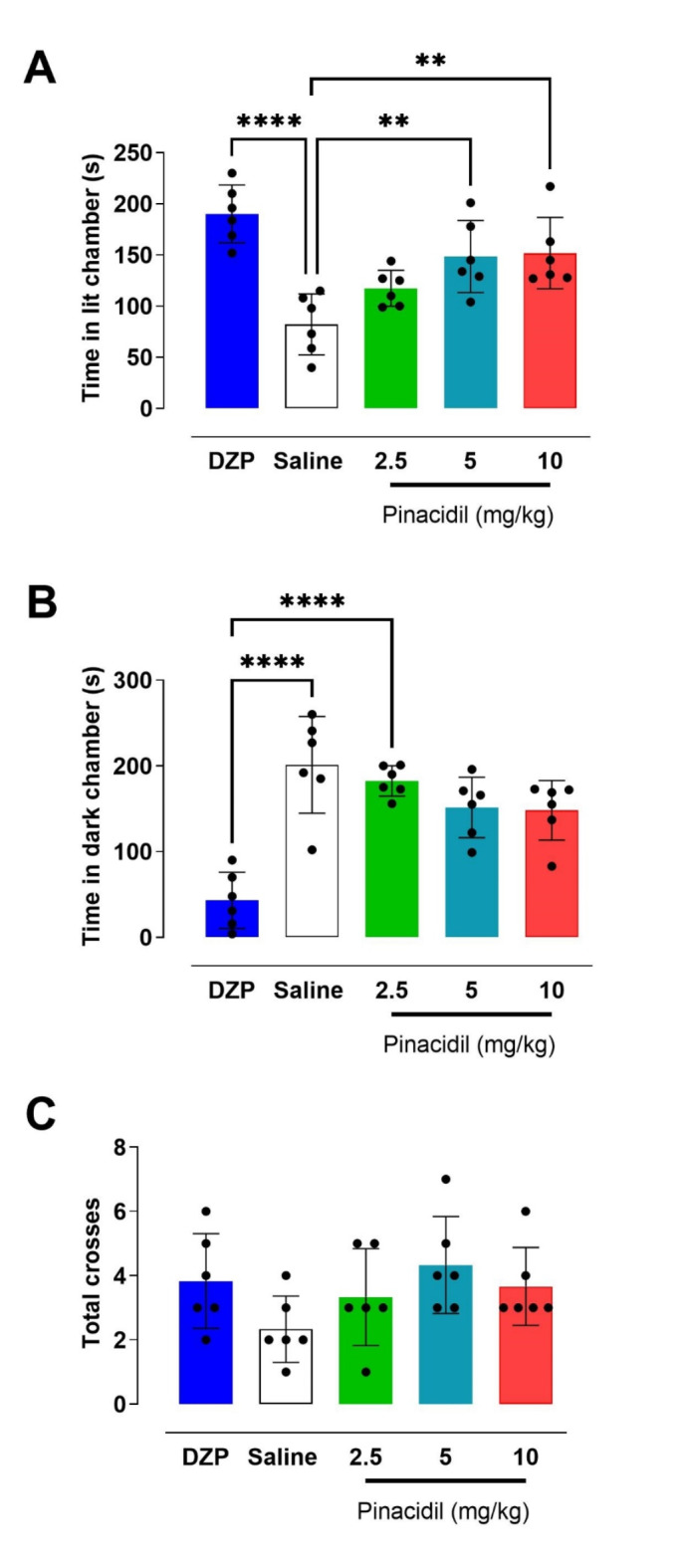

Light-dark Box Test

Regarding the LDB test, One-way ANOVAs showed statistical differences in time spent in light compartment [F(4,25) = 11.11; p < 0.0001]. Post-tests revealed that animals that received diazepam (p < 0.0001) or pinacidil at 5 (p = 0.005) and 10 mg/kg (p = 0.003) spent more time in the light compartment compared to the control animals (Fig. 5A). The analysis of time spent in dark compartment also revealed statistical differences among treatments [F(4,25) = 16.03; p < 0.0001]. However, post-tests showed decrease in time spent in the compartment for animals administered with diazepam in comparison with saline (p < 0.0001), as well as the three doses of pinacidil (p < 0.0005 for all doses; Fig. 5A). The number of crossings between the compartments showed no statistically significant difference between the experimental groups and the saline group [F(4,25) = 1.8; p = 0.15] (Fig. 5B and C).

Fig. 5.

Effect of treatment on rats evaluated in Light and Dark Box Test in Wistar rats (n = 6). (A) Time spent in the illuminated chamber; (B) Time spent in the dark chamber and (C) Total crossings between the two compartments of the box for 5 min. Bars represent mean ± SD. **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 significantly in ANOVA test followed by the Tukey post-test.

Motor performance - rotarod test

The mean fall latencies of the animals in the Rotarod are shown in Table 3. The data show that pinacidil at doses of 10 and 20 mg/kg did not affect the motor performance, force or equilibrium of the treated animals compared to the saline control group (F(4,25) = 0.46; p = 0.8801).

Table 3.

Performance on rotarod after administration of pinacidil in Wistar rats (n = 7).

| Latency to fall (seconds) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 min | 30 min | 45 min | 60 min | 75 min | |

| Saline | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

|

Pinacidil (10 mg/kg, i.p.) |

60 | 53.4 ± 17.3 | 60 | 60 | 58.6 ± 9.8 |

|

Pinacidil (20 mg/kg, i.p.) |

60 | 55 ± 13.2 | 58 ± 2.2 | 60 | 60 |

All data were expressed as means ± SD.

Discussion

Previous studies have shown that potassium channel activators have anticonvulsant activity, highlighting their potential in preventing seizures. Nicorandil, an activator of ATP-dependent potassium channels like pinacidil, had anticonvulsant activity previously demonstrated. Our study is therefore inspired by Rao’ 2015 research, which demonstrated the anticonvulsant effects of different doses of nicorandil in mice. According to these authors, nicorandil increased the latency to seizure onset and/or significantly protect the animals against PTZ-induced seizures. These effects were attributed to nicorandil’s ability to activate potassium channels, restoring ionic balance and regulating the release of neurotransmitters17. Based on pinacidil’s mode of action, we investigated if it could be used as anticonvulsant and potentially be further repositioned beyond its effects on angina and hypertension19,20.

In our study we demonstrated the anticonvulsant effect of pinacidil against behavioral induced by PTZ and Pilocarpine in rats. Also, pinacidil increased the latency time to first seizure in the case of animals not completely protected from PTZ-induced seizures. The anticonvulsant action was confirmed in two types of experimental models, exploring different mechanisms of chemoconvulsion, intended to decrease the possibility of a false positive for the pharmacological activity in question. As observed for nicorandil, the pharmacological effects presented here for pinacidil must be related to its more direct mechanism of action, i.e. the activation of ATP-dependent potassium channels. Our data corroborate previous findings showing that pinacidil inhibits epileptiform spike and wave discharges in anesthetized animals18. However, our results differ from those of Kobayashi and colleagues [2008] that reported no effects of pinacidil in 4-AP induced intracellular sodium increase in isolated hippocampal neurons. Despite being completely different experiments, we attribute the differences in results to the loss of anatomical connections due to cell culture preparations.

In addition, this study also showed the mild anxiolytic effects of pinacidil in the Open Field, EPM and LDB tests. Our results show that pinacidil increased both the exploratory rate and the frequency of behaviors considered risky, we conclude that the drug has anxiolytic activity, albeit discreet. Anxiolytic effects for anticonvulsant drugs are known and even expected according to a large collection of pharmacological examples, including drugs in clinical use21.

An important fact presented here is that pinacidil does not cause any motor impairment in the animals, even at doses twice as high as the highest dose at which the anticonvulsant and anxiolytic effects were observed. It was shown that pinacidil is a drug that is well tolerated by the animals, at least considering extrapyramidal effects and associated motor impairment are concerned. Thus, we can state that the anticonvulsant effect observed for pinacidil is not due to potential motor impairment caused by the drug, but rather to a genuine anticonvulsant pharmacological effect. Furthermore, these results corroborate those showing increased exploratory activity and locomotion in the anxiety tests.

Another important point to consider is that the pharmacological activities observed here for pinacidil occurred after systemic administration, indicating that pinacidil can cross the blood-brain barrier, which is of fundamental importance in the development of new drugs for the treatment of neurological and psychiatric conditions, such as epilepsy and anxiety, making pinacidil even more attractive in pharmacokinetic terms and for pharmaceutical use22.

In this study, we used male Wistar rats aged 4–5 weeks, which are commonly selected for seizure induction due to their heightened susceptibility. However, this age range includes both pre-pubertal and pubertal stages, where differences in GABAergic inhibition may influence the observed anticonvulsant effects. To fully understand the efficacy of pinacidil, future studies should investigate its effects in older, adult animals, considering the potential impact of developmental changes.

One of the main reasons to search for new drugs to control epilepsy and/or anxiety is due to the huge number of side effects exhibited by current available medications23. Among the main adverse effects of the chronic use of these drugs cause are drowsiness, dizziness, gastrointestinal disorders, mood and behavior changes, motor incoordination, impaired cognition, weight gain, lack of libido and liver overload24,25. Therefore, due to this wide range of effects, many patients abandon treatment, resulting in low therapeutic adherence. In addition to side effects, many drugs take time to exhibit their pharmacological effects or may even be ineffective as for cases of medication refractoriness, even when used in drug combination therapy26.

Besides the dual pharmacological effects, anticonvulsant and anxiolytic, presented here at similar doses, pinacidil shows good tolerability in terms of the absence of potential motor effects. It this case, pinacidil is a cyanoguanidine chemically derived from thioureas with potent antihypertensive activity, which are well tolerated by both animals and humans15,27. The discovery of new pharmacological activities for pinacidil is of great medical-pharmaceutical interest, particularly considering its potential for therapeutic repositioning.

Drug repositioning, also known as drug repurposing or reprofiling, refers to the identification of new therapeutic applications for existing drugs that were originally developed for other indications28. Drug repositioning enables the leveraging of investments already made in research, development, and safety testing, significantly reducing the time and costs involved in developing new treatments, as repositioned drugs already have an established safety and toxicity profile in humans. This can accelerate the regulatory approval process and allow patients to benefit more quickly from new therapeutic indications. Additionally, by investigating the properties of a drug in a new therapeutic indication, it is possible to discover new drug mechanisms of action or better understand the underlying molecular and/or cellular mechanisms of a given disease. This can lead to important insights for the development of more effective treatments28,29.

Drug repositioning, including for antihypertensive medications, is not new and can be well exemplified by the expanded use of traditional beta-blockers for the treatment of anxiety30. While this study did not include female rats, our findings demonstrate promising preliminary effects of pinacidil’s anticonvulsant and anxiolytic potential. Future studies incorporating both sexes are essential to fully explore its therapeutic applications. Although further experiments are necessary, the present study highlights, for the first time, new pharmacological activities of pinacidil. This could serve as an important starting point for better understanding its effects on the central nervous system through its anticonvulsant and anxiolytic actions. Once these actions are better characterized, they may suggest new uses for a well-known and already properly characterized drug.

Materials and methods

Drugs

Pinacidil Monohydrate was purchased from Sigma Aldrich, Brazil (CAS number 85 371 -64-8 with a purity of > 98%), as were the proconvulsants pentylenetetrazole (PTZ) (CAS number: 54-95-5) and Pilocarpine (CAS number 54-71-7). Injectable diazepam (DZP) was purchased from União Química (Brazil).

Animals

Male Wistar rats aged 4 to 5 weeks, weighing around 180 to 250 g (n = 6/7 per control or experimental group in all experiments, divided randomly) were purchased from ANILAB (Paulínia, SP). They were separated into four animals per box and housed in a Ventilife mini insulator for rats (497 mm long x 341 mm wide x 265 mm high and 1154 cm2 floor area), maintained with a 12/12 hour light/dark cycle and temperature (20 ± 2°C). Food and water were available ad libitum. All procedures were in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines, the Ethics Committee of the University of Ribeirão Preto (approval # 005/2022), and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Research Council, USA. All experiments were carried out in a soundproofed room between 07h00 and 12h00. All the platforms or arenas used in the different experiments were cleaned with 70% alcohol whenever each animal was replaced. In addition, all the animals were brought into the experimental room at least 30 min before each experiment for acclimatization. Behavior analyses were conducted after experiments by blinded experimenters. Only the supervisor was aware of treatments. After the experiments, animals were appropriately sacrificed using a lethal dose of sodium pentobarbital.

Experimental design

To evaluate the anticonvulsant effect of pinacidil, we used the models of chemoconvulsions induced by PTZ (90 mg/kg; i.p.) and Pilocarpine (320 mg/kg, i.p.). Both PTZ and Pilocarpine were dissolved in 0.9% (w/v) saline solution. The anxiolytic effect of pinacidil was assessed using the Elevated Plus Maze (EPM), Light-Dark Box (LDB) and Open Field tests. For all tests, diazepam 2 mg/kg (i.p.) was used as a positive control and 0.9% saline solution (i.p.) as a negative control. The experimental groups consisted of animals treated with different doses of pinacidil (2.5, 5 and 10 mg/kg; i.p.). The doses of pinacidil were selected based on similar pharmacological trials for nicorandil17. The dose of DZP was based on previous trials in our laboratory31. All experiments were filmed, and copies of the recordings are available.

Anticonvulsant screening

After administering the proposed treatments to control or experimental animals (n = 6/7), a 30-minute interval was observed before administering convulsants, and each animal was kept individually in a transparent acrylic arena (60 cm x 40 cm). The rats were observed and filmed for 30 min for PTZ trials and 45 min for Pilocarpine trials. All the experimental animals were observed for the occurrence of seizures and latency to the first seizure compared to the control groups, based on the Racine index32 modified by Pinel & Rovner33 and the classification of generalized tonic-clonic seizures with a score of 7/8.

Anxiolytic screening

Open Field Test

The circular arena used was the OPO199 model (Insight), with a diameter of 60 cm and a circular acrylic wall 50 cm high. The floor of the device is subdivided into 12 quadrants, with 4 of them forming a central zone and the others corresponding to the peripheral zones. The animals were placed separately in the central quadrant of the platform and, for five minutes, behavioral indicators related to anxiety and potential actions on locomotor performance and animal wakefulness/sedation were analyzed, such as: (I) voluntary locomotor activity (number of times the lines were crossed); (II) the animal’s preference for the center of the field over peripheral areas; (III) frequency of rearings (vertical exploration of the environment) and (IV) groomings (self-cleaning movements)31.

Elevated plus maze

The maze consisted of two open wooden arms measuring 50 × 10 cm and two closed arms measuring 50 × 10 × 40 cm each, arranged so that the open arms were opposite each other. These arms were connected by a central platform measuring 10 × 10 cm, and the maze was kept at a height of 50 cm from the floor, with the open arms surrounded by a small 0.5 cm acrylic border to prevent the animals from falling. After 30 min of the different control or experimental treatments, the animals were placed in the intermediate compartment of the EPM (head facing the open arm) and left to freely explore the apparatus for 5 min34.

During the test, classic behavioral parameters were evaluated, such as time spent in the open arms (TOA), time spent in the closed arms (TCA), percentage TOA (100 x TOA/(TOA + TCA), number of dips and number of entries in the arms.

Light-dark Box Test

The LDB apparatus consisted of a box (46 × 27 × 30 cm) divided into a dark and a light compartment, connected by a small door measuring 7.5 × 7.5 cm. The model of equipment used in the test was the EP158 (Insight, São Paulo, Brazil). After 30 min of the treatments, each control or experimental animal was placed separately in the center of the illuminated compartment (20 W LED lamp, > 300 lx), facing the access opening to the dark field, and was filmed for 5 min for posterior analysis35. In this test, we considered: (I) number of passages between the light and dark fields were evaluated (entered compartment with all four paws); (II) time spent in the light field and (III) time spent in the dark field.

Motor performance evaluation

Rotarod test

The effects of different doses of pinacidil (10 and 20 mg/kg) were evaluated in terms of potential interference in the motor coordination and wakefulness of the animals compared to the control groups. The rotarod apparatus Acceler Rota-rod Jones & Roberts, for rats 7750 (Ugo Basile, Comerio, Italy) with a rotation speed of 4 rev/min was used. The test was preceded by three training sessions with each animal lasting one minute each at the above-mentioned rolling speed. The following day, the animals were subjected to the apparatus again and only those that remained on the bar for 1 min were considered fit to take part in the rotarod test. Thirty minutes after the treatments, the animals were placed on the apparatus for a maximum of one minute, and the latency to the first fall was assessed at different time windows (0 min; 15 min; 30 min; 45 min; 60 min and 75 min).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses and graph construction were performed using GraphPad Prism 5.1. To ensure robust and reliable results, all experiments included appropriate control groups, and researchers conducting the analyses were blinded to the treatment conditions. The sample size (n) was carefully determined to ensure adequate statistical power.

Fisher’s exact test was employed to assess protection against seizures induced by PTZ or pilocarpine. Rotarod data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA. For all other assessments, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-test was applied. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgements

Authors are thankful Fapesp, Capes and CNPq for funding and all the staff at Biotechnology Department at Ribeirão Preto University for technical assistance. Authors also thank Senior Independent Consultant Dr Alexandra Cunha for her critical reading of the manuscript and assistance with language.

Author contributions

A.T.P., E.A.G. and R.O.B. designed the study. A.T.P. and E.A.G. performed all experiments and data analyses. R.O.B. supervised the work and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and added considerations to the final version of the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are freely available from the corresponding author on request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Neri, S. et al. Epilepsy in neurodegenerative diseases. Epileptic Disord. 24(2), 249–273 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loesch, A. M. et al. Seizure-associated aphasia has good lateralizing but poor localizing significance. Epilepsia. 58(9), 1551–1555 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization (WHO). Epilepsy. (2024). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/epilepsy

- 4.Vazquez, B. & Devinsky, O. Epilepsy and anxiety. Epilepsy Behav.4(4), 20–25 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scott, A. J., Sharpe, L., Loomes, M. & Gandy, M. Systematic review and meta-analysis of anxiety and depression in youth with epilepsy. J. Pediatr. Psychol.45(2), 133–144 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boleti, A. et al. Pathophysiology to risk factor and therapeutics to treatment strategies on epilepsy. Brain Sci.14(1), 71 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kobayashi, K., Endoh, F., Ohmori, I. & Akiyama, T. Action of antiepileptic drugs on neurons. Brain Dev.42(1), 2–5 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan, R. et al. Role of potassium ion channels in epilepsy: focus on current therapeutic strategies. CNS Neurol. Disord Drug Targets. 23(1), 67–87 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fan, C. et al. Calcium-gated potassium channel blockade via membrane-facing fenestrations. Nat. Chem. Biol.20, 52–61 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heron, S. E., Scheffer, I. E., Berkovic, S. F., Dibbens, L. M. & Mulley, J. C. Channelopathies in idiopathic epilepsy. Neurother. 4(2), 295–304 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steinlein, O. K. Genetic mechanisms that underlie epilepsy. Nat. Rev. Neurosci.5(5), 400–408 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nilsson, M. et al. An epilepsy-associated KV1.2 charge-transfer-center mutation impairs KV1.2 and KV1.4 trafficking. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA119(17) (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Liss, B. & Roeper, J. Molecular physiology of neuronal K-ATP channels (review). Mol. Membr. Biol.18(2), 117–127 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patton, B. L., Zhu, P., ElSheikh, A., Driggers, C. M. & Shyng, S. L. Dynamic duo: Kir6 and SUR in KATP channel structure and function. Channels. 18(1), 2327708 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedel, H. A., Brogden, R. N. & Pinacidil Drugs39, 929–967 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu, M. et al. Pinacidil ameliorates cardiac microvascular ischemia–reperfusion injury by inhibiting chaperone-mediated autophagy of calreticulin. Basic. Res. Cardiol.119, 113–131 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rao, T. N., Ambadasu, B., Prasad, S. V., Srinivas, A. & Yakaiah, V. Effect of nicorandil on pentylenetetrazole (PTZ) induced convulsions in mice. Int. J. Clin. Biomed. Res.1(2), 99–101 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Acar, Y. et al. Agonist and antagonist effects of ATP-Dependent Potassium Channel on Penicillin Induced Epilepsy in rats. Kafkas J. Med. Sci.6(1), 38–45 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldberg, M. R., Rockhold, F. W., Thompson, W. L. & DeSante, K. A. Clinical pharmacokinetics of pinacidil, a potassium channel opener, in hypertension. J. Clin. Pharmacol.29(1), 33–40 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao, J. et al. Nicorandil exerts anticonvulsant effects in Pentylenetetrazol-Induced seizures and maximal-electroshock-Induced seizures by downregulating excitability in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Neurochem Res.48, 2701–2713 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koh, W., Kwak, H., Cheong, E. & Lee, C. J. GABA tone regulation and its cognitive functions in the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci.24(9), 523–539 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanner, A. M. & Bicchi, M. M. Antiseizure medications for adults with epilepsy: A review. JAMA. 327(13), 1269–1281 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwon, J. Y. Perspective: therapeutic potential of flavonoids as alternative medicines in epilepsy. Adv. Nutr.10(5), 778–790 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar, P., Sheokand, D., Grewal, A., Saini, V. & Kumar, A. Clinical side-effects based drug repositioning for anti-epileptic activity. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn.42(3), 1443–1454 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Panholzer, J. et al. Impact of depressive symptoms on adverse effects in people with epilepsy on antiseizure medication therapy. Epilepsia open.9(3), 1067–1075 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solmi, M. et al. Safety of 80 antidepressants, antipsychotics, anti-attention-deficit/hyperactivity medications and mood stabilizers in children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders: a large scale systematic meta-review of 78 adverse effects. World Psychiatry. 19(2), 214–232 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gordon, T., McInnes, Y. H., Lip, J. E. & Hall Comprehensive Hypertension, Mosby, 1037–1048 (2007).

- 28.Jarada, T. N., Rokne, J. G. & Alhajj, R. A review of computational drug repositioning: strategies, approaches, opportunities, challenges, and directions. J. Cheminform. 12(1), 46 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hua, Y. et al. Drug repositioning: Progress and challenges in drug discovery for various diseases. Eur. J. Med. Chem.15(234), 114239 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Repova, K., Aziriova, S., Krajcirovicova, K. & Simko, F. Cardiovascular therapeutics: a new potential for anxiety treatment? Med. Res. Rev.42(3), 1202–1245 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Oliveira, D. D., Da Silva, C. P., Iglesias, B. B. & Beleboni, R. O. Vitexin possesses anticonvulsant and anxiolytic-like effects in murine animal models. Front. Pharmacol.11, 1181 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Racine, R. J. Modification of seizure activity by electrical stimulation. II. Motor seizure. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol.32(3), 281–294 (1972). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pinel, J. P. & Rovner, L. I. Experimental epileptogenesis: kindling-induced epilepsy in rats. Exp. Neurol.58(2), 190–202 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu, C. et al. Effects of exercise training on anxious-depressive-like behavior in Alzheimer rat. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc.52(7), 1456–1469 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Da Silva, C. P. et al. Antidepressant activity of Riparin A in murine model. Behav. Pharmacol.32(7), 599–606 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are freely available from the corresponding author on request.