Abstract

Fungal natural products from various species often feature hydroxamic acid motifs that have the ability to chelate iron. These compounds have an array of medicinally and ecologically relevant activities. Through genome mining, gene deletion in the host Aspergillus terreus, and heterologous expression experiments, this study has revealed that a nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) TamA and a specialized cytochrome P450 monooxygenase TamB catalyze the sequential biosynthetic reactions in the formation of terramides A-C, a series of diketopiperazines (DKPs) with hydroxamic acid motifs. Feeding experiments showed that TamB catalyzes an unprecedented di-hydroxylation of the amide nitrogens in the diketopiperazine core. This tailoring reaction led to the formation of two bidentate iron-binding sites per molecule with an unusual iron-binding stoichiometry. The structure of the terramide A-Fe complex was characterized by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), Raman spectroscopy and electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy (EPR). Antimicrobial assays showed that the iron-binding motifs are crucial for the activity against bacteria and fungi. Murine infection experiments indicated that terramide production is crucial for the virulence of A. terreus and could be a potential antifungal drug target.

Subject terms: Oxidoreductases, Biosynthesis, Metabolic pathways

Terramides A-C are produced by Aspergillus terreus and feature hydroxamic acid motifs in diketopiperazines to chelate iron; however, their biosynthesis is not fully understood. Here, the authors probe the function of two key enzymes TamA and TamB and propose the biosynthesis of terramides A-C as well as their function in the virulence of A. terreus.

Introduction

Iron is one of the essential elements for life system, but its low solubility limits the uptake and utilization by organisms1. Microorganisms growing under iron-limiting conditions will synthesize low molecular-weight iron chelators. Most of these molecules are produced by nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) or NRPS-independent (NIS), and they can be further classified into different groups: catecolates, carboxylates, hydroxamates, and mixed types2. Hydroxamic acids are a class of weakly acidic compounds that can form stable chelates with a variety of transition metals3. Fungi mainly synthesize hydroxamic acid siderophores, which have great chelating ability to Fe(III). They can be divided into monohydroxamic acid, such as aspergillic acid, bishydroxamic acids, such as mycelianamide, schizokinen, terregens factor, rhodotorulic acid, mycobactins P and T, and trihydroxamic acids, such as ferrichrome, coprogen, fusarinine C and ferrioxamine4. Due to their iron-chelating ability, siderophores are produced by various pathogenic microorganisms as virulence factors during host infection to acquire essential iron from the host5. For example, the iron uptake system of Aspergillus fumigatus has been well characterized and shown to be indispensable for fungal infection6. While the production of siderophores is a hallmark of pathogenicity, these compounds can also be repurposed for beneficial applications, including targeted antibiotic delivery, cancer treatment, vaccine development, and diagnostics7–11.

Siderophores can be connected to antibiotic molecules through a molecular linker. The siderophore part will be recognized and actively taken up into the cell where the antibiotic part of the conjugate can kill the pathogen12. In addition, deferoxamine B is used in the clinical treatment of iron ion poisoning caused by metabolic disorders13,14. Recently, siderophores produced by A. fumigatus have been shown to be potential markers for infection15. Lastly, the conjugation of siderophores with fluorescent dyes, or loading them with Ga(III) makes it possible to produce imaging compounds, enabling the combination of positron emission tomography and optical imaging for clinical application16,17. Terramides were first isolated in 1986 from Aspergillus terreus, and their stereochemistry was assigned based on hydrolysis and amino acid analysis18. Later it was shown that terramides have antifungal activity19. More recently their antibacterial activity was shown to be related to the iron content of the production medium20. Because A. terreus is one of the most common causative agents of aspergillosis, a life-threatening infection in humans, we started to investigate the biosynthesis, biological functions of terramides and their role in Aspergillus terreus infection.

Results and discussion

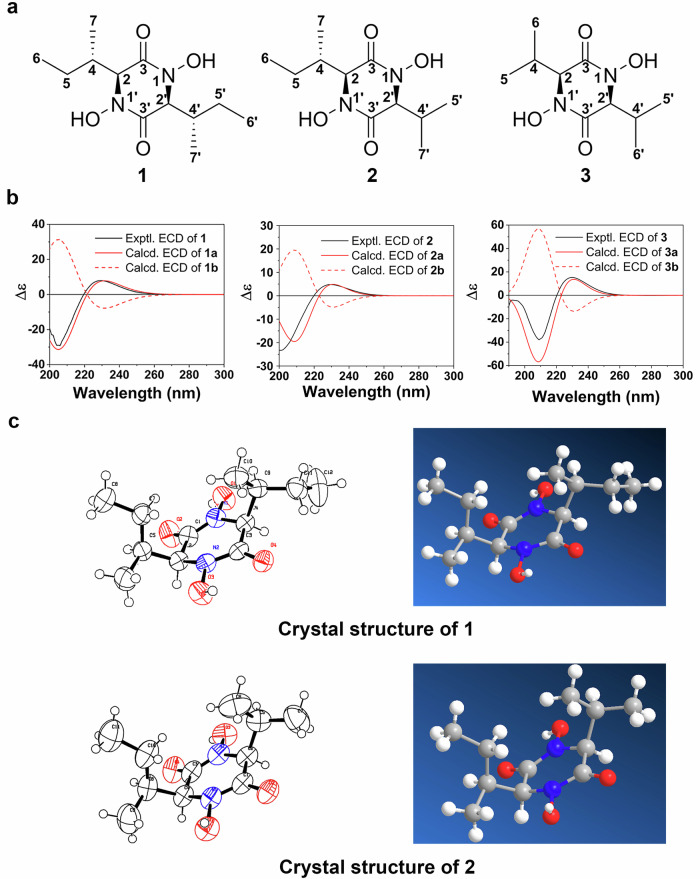

Structural analysis

At first, we optimized the culture conditions for A. terreus to achieve higher production of terramides A-C (1-3) (Fig. 1a)18. Feeding the hypothetical precursor21 amino acids valine, isoleucine, and creating iron-deficient conditions22, through the addition of bathophenanthrolinedisulfonic acid, we could increase the production of 1-3. Terramide A (1), B (2), and C (3) were next extracted and purified (Fig. S1). The substances and their associated iron complex were dissolved in methanol, the UV absorption characteristics of these compounds were determined by HPLC (Figs. S19–27). Their molecular formulas were established by LC-MS, and the structures were elucidated by 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR (Tables S1–6, Figs. S3–14). They correspond to previously published data20. We observed the presence of single peaks with m/z of [M+H]+ 259.1653, 245.1504 and 231.1334 which refer to 1 ([M+H]+ Calcd for C12H23N2O4+ 259.1652), 2 ([M+H]+ Calcd for C11H21N2O4+ 245.1496) and 3 ([M+H]+ Calcd for C10H19N2O4+ 231.1339), respectively (Fig. S2). Electronic circular dichroism (ECD) was applied to determine the configurations of C-2 and C-4 of 1-3, which showed consistent configurations with their corresponding diketopiperazines 4-6 (Fig. S15). The experimental ECD spectrum showed the main positive feature at 230 nm and the negative feature at 205 nm, which were well-reproduced by the calculated ECD curve for (2S, 4S)-1, (2S, 4S)-2, (2S)-3 (Fig. 1a, b, Tables S7–12, Figs. S16–S18). The configurations of C-2 and C-4 of 4-6 are similar. Furthermore, the crystal structure of 1 and 2 (Tables S13–18, Fig. 1c, Supplementary Data 2) confirmed the configuration established by ECD. The absolute configuration of 3 is likely the same as that of 1 and 2 due to the shared biosynthetic origin, which will be illustrated later.

Fig. 1. Structural analysis of terramides A-C (1, 2, 3).

a Structures of 1, 2, 3. b Experimental ECD curves of 1, 2, 3, 1a = (2S, 4S, 2′S, 4′S)-1, 1b = (2 R, 4 R, 2′R, 4′R)-1, 2a = (2S, 4S, 2′S)-2, 2b = (2 R, 4 R, 2′R) -2, 3a = (2S, 2′S)-3, and 3b = (2 R, 2′R)-3. c Crystal structures of 1 and 2.

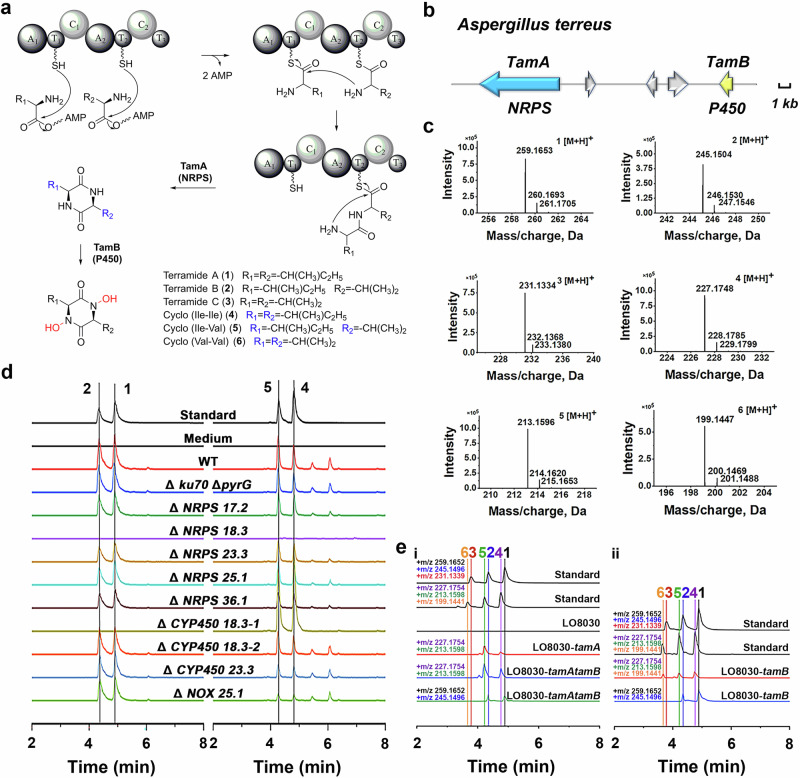

Exploration of terramides biosynthetic pathway

We hypothesized that 1, 2, and 3 are formed through the condensation of isoleucine and valine, which afterward would require a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase (CYP450) gene for hydroxylation at the amide nitrogen position (Fig. 2a–c). We sequenced the genome of A. terreus and analyzed it using antiSMASH fungal version 6.0.123. A total of 41 NRPS (including NRPS-like) genes could be identified. Five NRPS genes containing two complete sets of A (adenylation domain)-PCP (peptidyl carrier protein domain)-C (condensation domain) motifs (hereinafter referred to as NRPS 17.2, NRPS 18.3, NRPS 23.3, NRPS 25.1 and NRPS 36.1, respectively) were selected for further investigation (Fig. S28). In addition, three CYP450 genes and one NADH oxidase (NOX) gene present in spatial proximity were selected (hereinafter referred to as CYP450 18.3-1, CYP450 18.3-2, CYP450 23.3 and NOX 25.1, respectively) based on the requirement of hydroxylation at the amide nitrogen24.

Fig. 2. Biosynthesis of 1, 2, and 3.

a Biosynthetic pathway of 1-6. b Genetic organization of the tam gene cluster for terramides biosynthesis in A. terreus CMI44339. c Mass (positive mode) spectra of 1-6. d LC-MS analyses of metabolites produced by A. terreus strains. e Heterologous expressions and feeding experiments in A. nidulans.

To allow genetic manipulation of the producer strain, we deleted two genes, ku70 and pyrG. Deletion of ku70 reduces non-homologous end joining and makes gene deletions more efficient25. The pyrG gene, encoding a phosphate decarboxylase, can be used as a selective marker after its disruption26. Therefore, the genes were deleted to eliminate non-homologous end joining and to construct an auxotrophic strain using a CRISPR-Cas9 method27–29. The A. terreus mutant named ATEG002 (Δku70, ΔpyrG), was used as a starting strain. On this basis, five NRPS genes, three CYP450 genes, and one NADH oxidase gene were individually disrupted to identify the genes associated with the biosynthesis of terramides (Figs. S29, 30). Deletion of NRPS 18.3 (ATEG004 or ΔtamA) caused abrogation of 1-6 production. The addition of valine/isoleucine to the medium upregulated the expression level of tamA and led to a higher production of terramides (Fig. S32). Further deleting the CYP450 18.3-1 (ATEG008 or ΔtamB) alone, lead to sole production of 4-6 but no formation of 1-3, suggesting that this CYP450 is likely responsible for the N-hydroxylation of DKPs (Fig. 2d).

To further verify the gene function, the genes were heterologously expressed in the Aspergillus nidulans strain LO8030 (Fig. S31)30. The strain carrying NRPS 18.3 (mutant strain LO8030-tamA) successfully produced 4 and 5, and the strain carrying both NRPS 18.3 (tamA) and CYP450 18.3-1 (tamB) successfully produced 1 and 2, in contrast to the control LO8030 (Fig. 2e, i). To provide further evidence that TamB can catalyze the hydroxylation of DKPs, LO8030-tamB was administered with 4-6, and the production of compounds 1-2 could be detected in the fermentation medium (Fig. 2e, ii). Formation of 3 could not be detected, potentially attributable to low uptake or enzyme-substrate affinity.

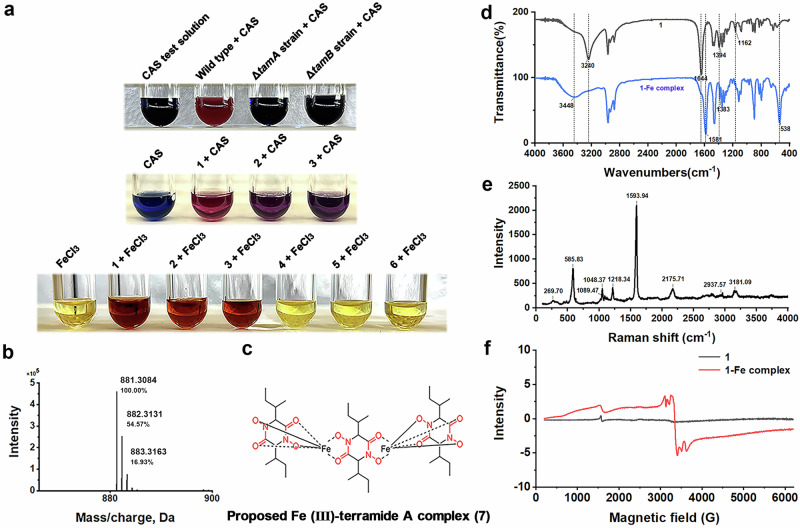

Determination of Fe (III)-terramide A complex

After establishing the biosynthetic route for 1-3, we explored their ability to bind iron ions. We incubated the fermentation supernatant with CAS (Chrome azurol S) test solution, which turns red in the presence of iron-chelating compounds. Incubation with supernatant from wild-type strain leads to red coloration, indicating the formation of an iron chelator. However, incubation with supernatant from tamA or tamB deletion strains (ATEG004 and ATEG008) shows no red color formation. We conclude that 1-3 are the major iron-chelating compounds produced by A. terreus under these conditions (Fig. 3a). Moreover, 1 has the strongest ability to chelate iron ions in comparison to 2-3 (Fig. 3a, see Supplementary information for data). Incubation of pure 1-3 with Fe3+ (200 μM FeCl3) results in a red iron complex, whereas 4-6 cannot form such a complex likely due to the absence of N-hydroxyl groups.

Fig. 3. Determination of Fe (III)-terramide A complex (7).

a CAS siderophore testing. b High-resolution mass spectrum of 7. c Proposed structure of 7-Fe complex. d FT-IR spectra of 1 and 1-Fe complex. e Raman spectrum of 1-Fe complex. f EPR spectra of 1 and 1-Fe complex.

LC-MS was used to analyze the complex of 1 with Fe3+. The complex 7 was detected (C36H60N6O12Fe2, [M+H]+ 881.3084) (Fig. 3b, c) and based on the molecular mass a ratio of 1 to Fe3+ of 3:2 could be inferred.

The chelation of Fe with 1 and the resulting complex was characterized by FT-IR, EPR and Raman spectroscopy. The HOH stretching vibrations significantly shifted to higher range frequencies, from 3240 cm−1 to 3448 cm−1, due to the dissociation of the hydroxyl groups caused by coordination to Fe (III). Also, the O-H deformation band at 1394 cm−1 disappeared due to iron binding. The band at 1162 cm−1 in the spectrum of 1, assigned to one type of C-N vibration, disappeared in the spectrum of 1-Fe complex. The new strong band at 538 cm−1 in the FT-IR spectra of 1-Fe complex was attributed to the Fe-O stretching vibration. The band at 1644 cm−1 of 1 shifted to 1581 cm−1 (1-Fe complex), due to the overlapping of the C=O stretching vibrations of the secondary amides and the C=O stretching vibrations of the hydroxamate groups whose oxygen atoms are involved in the Fe (III) bonding. Shifting the electrons towards the oxygen atom, causes C=O stretching vibration (~1600 cm−1) to transform into C=N+ stretching vibration (~1580 cm−1)31. (Table S21, Fig. 3d). The observed features of the spectrum are consistent with those of desferrioxamine B and ferrioxamine B32,33. The Raman spectrum shows a characteristic Fe-O (585.83 cm−1) signal (Fig. 3e)33,34. EPR can detect the signal of non-paired electrons, and the signal at G ~ 1500 observed in the spectrum of the iron complex is characteristic for Fe3+ from Fe3+-O, indicating the successful binding of Fe3+. The appearance of the signal at G ~ 3400 may be caused by the dipole-dipole interactions between Fe3+ ions attributed to the formation of Fe3+-O-Fe3+ bonds (Fig. 3f)35.

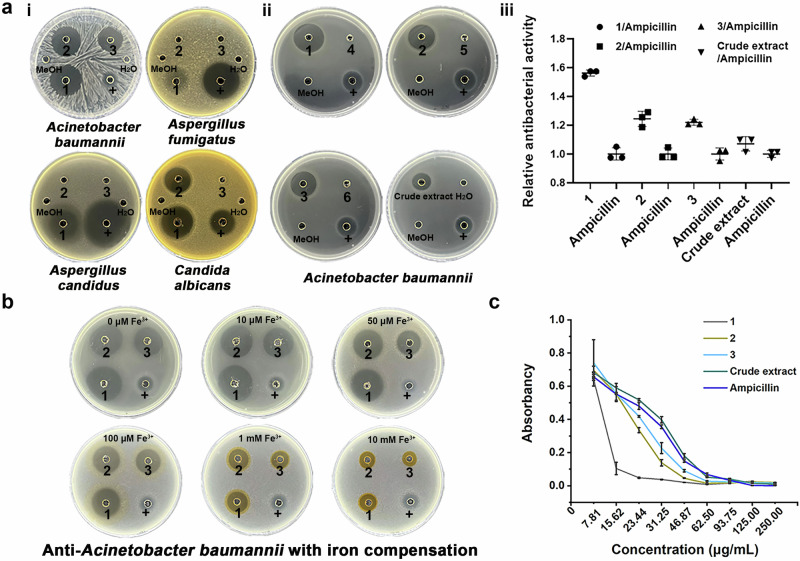

Antimicrobial activity of terramides

Given the unique structures of 1, 2, and 3, their antimicrobial activities were investigated. Five bacterial strains (Streptococcus pneumoniae BNCC338425, Staphylococcus aureus BNCC186335, Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC19606, Salmonella enteritidis BNCC103134, Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1), and three fungal strains (Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus candidus, Candida albicans) were selected to detect antibacterial and antifungal activity of 1-6 (Fig. 4a, Figs. S33, 34). The results showed that 1, 2, and 3 had a significant growth inhibition effect on A. baumannii, 1 had a significant growth inhibition effect on A. candidus, 1 and 2 had a significant growth inhibition effect on C. albicans (Fig. 4a, i). This suggests that structural differences between the three compounds lead to differences in activity. The structural changes might impact the iron affinity of the compounds and therefore explain the differences in activity.

Fig. 4. Antimicrobial activity and the effect of iron addition to the medium on antibacterial activity of 1-3.

a (i) Antimicrobial activity of 1-3 against Acinetobacter baumannii, Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus candidus, and Candida albicans, “+” is ampicillin for bacterial, hygromycin B for fungi, (ii) Anti-A. baumannii activity of 1-3 (10 mg × mL−1) compared with 4-6 (10 mg × mL−1), (iii) Relative anti-A. baumannii activity. n = 3, different letters indicate significant difference, p < 0.05. b Effect of iron addition to the medium on antibacterial activity of 1, 2, 3 (10 mg × mL−1). c MIC of 1, 2, 3 and crude extract.

The DKPs 4-6 did not show any antimicrobial activity against the tested bacteria and fungi (Fig. 4a ii, iii, Fig. S34). Thus, the N-hydroxylation 1-3 was deduced to be the key factor for their antimicrobial activity. We also observed that the addition of iron to the medium results in a significant loss of antibacterial activity of 1-3 (Fig. 4b). Therefore, iron complexation is likely to be the underlying mechanism for the observed antibacterial activity. The MICs (minimum inhibitory concentrations) of 1-3 on A. baumannii were measured. The MIC of 1-3 and ampicillin were 23.44, 46.87, 62.5, and 93.75 μg × mL−1 (Fig. 4c), respectively, indicating that terramides have stronger inhibition effects against A. baumannii than ampicillin.

The effect of terramides production in Aspergillus terreus infection

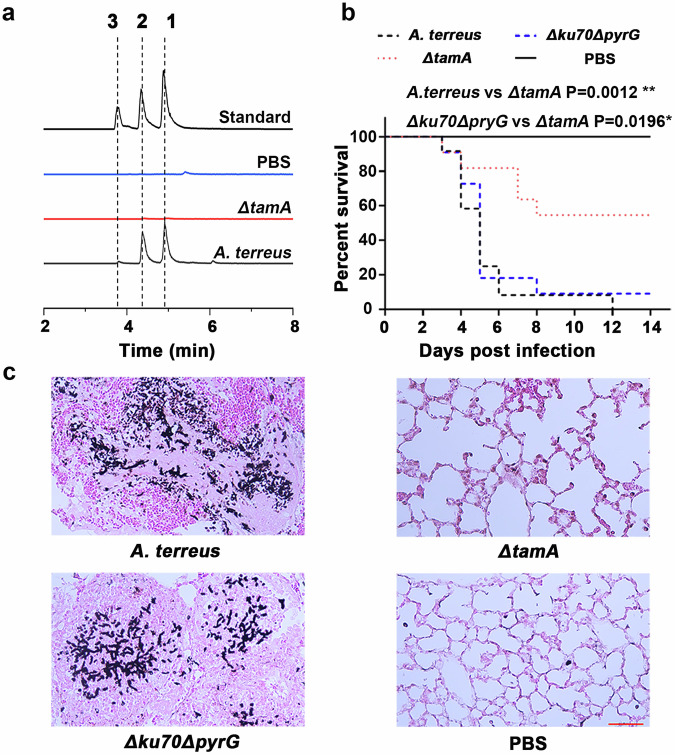

Aspergillus terreus, a pathogenic microorganism causing invasive and disseminated aspergillosis, is an acute threat to human health that produces a range of secondary metabolites35–38 and production of siderophores is thought to be a critical factor for fungal virulence39. Therefore, we investigated the roles of terramides in A. terreus virulence. We assessed the virulence of the ΔtamA strain (ATEG004) in immune-compromised mice. All of the mice infected with the wild-type strain succumbed to the disease within 12 days after the infection. The Δku70ΔpyrG strain (ATEG002) killed 90% of the mice, in contrast, only 50% of mice died in the group infected with ΔtamA (ATEG004) deletion strain (Fig. 5b). Histopathology revealed invasive hyphal growth in mice lungs infected with the wild-type strain, whereas surviving mice from ΔtamA infection group showed complete fungal clearance (Fig. 5c). The in vivo relevance of terramide production is emphasized by the fact that the compounds can be detected in organic extracts from infected lung tissue (Fig. 5a). Thus, we conclude that the deletion of tamA attenuates the virulence of A. terreus in a murine infection model and that production of 1-3 is crucial for acquiring iron in the host environment.

Fig. 5. The effect of terramides production in Aspergillus terreus infection.

a LC-MS detection of 1, 2 and 3 in lungs from infected mice. b Survival curve of wild-type, ΔtamA, Δku70ΔpyrG strains in a murine infection model. Statistical significance was assessed using a one-way ANOVA test with multiple comparisons. c Histopathology of lungs from infected mice, scale bar 50 µm.

In summary, the terramide biosynthetic pathway was elucidated. TamA is the NRPS gene responsible for the formation of 4-6, and TamB catalyzes the N-hydroxylation of two amide nitrogens. This reaction is a novel addition to the currently known set of DKP tailoring biotransformations and might be useful for pathway engineering attempts. Overall, terramide biosynthesis shows similarities to aspergillic acid production. In this pathway, the NRPS enzyme AsaC is responsible for the condensation of the leucinecarboxyl group and isoleucineamine group, which is then released by reduction to form dipeptide aldehyde (NH-Leu-Ile-CHO-). Multiple steps and final oxidation by the P450 enzyme AsaD lead to the product aspergillic acid, containing hydroxamic acid group. Aspergillic acid can complex ferric ions to form the chelate ferriaspergillin40. In addition, pulcherriminic acid from Bacillus species is also able to partially chelate Fe (III) with its two hydroxamic acids and is thought to work as an antibiotic or a siderophore. Pulcherriminic acid biosynthesis starts with two Leu, which are cyclized by the cyclic dipeptide synthetase YvmC. Afterward, the P450 enzyme Cyp134A1 (CypX) forms the dihydroxamic acid. This compound can chelate iron to form the extracellular red pigment pulcherrimin41,42. The terramide-iron complex was identified through LC-MS and further analyzed using various spectroscopic methods to suggest a structural formula for the complex. Furthermore, we could show that the production of terramides plays a key role in the virulence of A. terreus and that tamA could be targeted to block the accumulation of iron. In addition, terramides might be useful as biomarkers of infection. This class of siderophores could be used as lead structures for small iron-chelating compounds with an unusual iron-binding stoichiometry different from previously described iron chelators.

Methods

General

ECD spectra were measured on an Applied Photophysics/Chirascan spectrometer with a 1-mm path length cuvette. The NMR experiments were performed on a nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometer (BRUKER AVIII500M). All LC-MS analyses were performed on a SCIEX OS LC-MS (Zeno TOF 7600 system equipped with a diode array detector, and Agilent poroshell 120 phenyl-hexyl 1.9 µm, 2.1 × 150 mm2 column) using positive mode electrospray ionization with a linear gradient acetonitrile-water program: acetonitrile-water, flow rate of 0.25 mL × min−1, 0–12.00 min 10%–100% acetonitrile, 12.01–14.00 min 100% acetonitrile. Preliminary separation was performed on a flash chromatography system (Santai Technologies, Inc.) first. Subsequent purification was performed using a Shimadzu semi-preparative HPLC with a photodiode array (PDA) detector using a Phenomenex Luna C18 column (250 × 10 mm2, 5 μm), at 25 °C with a linear gradient acetonitrile-water program: acetonitrile-water, flow rate of 4 mL × min−1, 0–13.00 min 30%–60% acetonitrile, 13.01–17.00 min 100% acetonitrile, 17.01–20.00 min 100% acetonitrile, 20.01–25.00 min 10% acetonitrile. Acetonitrile (LC/MS grade for LC-MS analyses, HPLC grade for HPLC analyses) was purchased from Merck KGaA. The acetonitrile-water mixture was treated with ultrasound for half an hour.

Strains and culture conditions

Aspergillus terreus (A. terreus) CMI 44339 was cultivated in still medium (per liter, 50 g sucrose, 2 g NaNO3, 1 g K2HPO4, 0.5 g KCl, 0.25 g MgSO4, and 0.01 g FeSO4, 5 g yeast powder, pH 7.5) with 20 μM bathophenanthrolinedisulfonic acid, 10 mM valine, and 10 mM isoleucine added at 28 °C for 14 days, using a previously described method18. Aspergillus nidulans LO8030 was used as the heterologous expression host strain, and transformants were cultivated in CD medium (per liter, 10 g Glucose, 50 mL 20x Nitrate salts, 1 mL Trace elements, 218.6 g Sorbitol, 20 g Agar, pH 6.5) and CD-ST medium (per liter, 20 g Starch, 20 g Tryptone, 50 mL 20x Nitrate salts, 1 mL Trace elements, pH 6.5) with appropriate supplements (uracil, uridine, riboflavin, and pyridoxine-HCl) at 28 °C for 5 days43. Additionally, Escherichia coli DH5α strain was cultivated in the LB medium with 100 μg × mL−1 ampicillin at 37 °C for plasmid amplification. The strains and primers used in this study are listed in Tables S19, 20.

Compounds

A. terreus CMI 44339 was cultivated in the still medium at 28 °C for 14 days and extracted with ethyl acetate (EtOAc). The EtOAc extract was concentrated in vacuo and extracted with n-hexane, and further diluted to 50% methanol before being extracted with trichloromethane (TCM). The TCM fraction was applied to a flash chromatography system (Santai Technologies, Inc.) to yield eight fractions (FrA-H). FrD (25.45 mg), which was applied to the Shimadzu semi-preparative HPLC system with the Phenomenex Luna C18 column to yield 1 (Fre, 4.53 mg, tR = 10.4 min), 2 (Frd, 4.82 mg, tR = 7.6 min) and 3 (Frc, 1.83 mg, tR = 5.4 min). The purification flow chart is shown in Fig. S1. 4-6 were purchased from Yiqing Biotechnology (Jiangsu) Co. Ltd as a standard for LC-MS and used to help judge the absolute configuration of 1-3.

Conformational analyses and computational details

The absolute configurations of 1, 2, and 3 were determined by quantum chemical calculations of their theoretical ECD spectra. According to the biosynthetic pathway, (2S, 4S, 2′S, 4′S)-1, (2S, 4S, 2′S)-2, and (2S, 2′S)-3 were arbitrary chosen for theoretical studies. Conformational analyses were first carried out via Monte Carlo searching using molecular mechanism with MMFF force field in the Spartan 18 program44. The results showed 11 lowest energy conformers of (2S, 4S, 2′S, 4′S)-1 and (2S, 4S, 2′S)-2 and 6 lowest energy conformers of (2S, 2′S)-3 within an energy window of 2 Kcal × mol−1. Those conformers were then reoptimized using DFT at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level using the Gaussian 09 program45. The B3LYP/6-31G(d) harmonic vibrational frequencies were further calculated to confirm their stability and only 5 conformers of (2S, 4S, 2′S, 4′S)-1, 6 conformers of (2S, 4S, 2′S)-2, and 5 conformers of (2S, 2′S)-3 whose relative Gibbs free energies in the range of 0–1.5 Kcal × mol−1, were refined and considered for next step. The energies, oscillator strengths, and rotational strengths of the first 60 electronic excitations were calculated using the TDDFT methodology at the ωB97XD/TZVP level in acetonitrile. The ECD spectra were simulated by the overlapping Gaussian function (σ = 0.53 eV of (2S, 4S, 2′S, 4′S)-1, σ = 0.40 eV of (2S, 4S, 2′S)-2 and (2S, 2′S)-3)46. To get the final ECD spectrum, the simulated spectra of the lowest energy conformers were averaged according to the Boltzmann distribution theory and their relative Gibbs free energy (ΔG). The theoretical ECD curve of (2R, 4R, 2′R, 4′R)-1, (2R, 4R, 2′R)-2, and (2R, 2′R)-3 was obtained by directly reverse that of (2S, 4S, 2′S, 4′S)-1, (2S, 4S, 2′S)-2, and (2S, 2′S)-3, respectively.

Compared to the experimental ECD curve of 1, 2, and 3 in the 200–300 nm region, the calculated ECD curve for (2S, 4S, 2′S, 4′S)-1, (2S, 4S, 2′S)-2, and (2S, 2′S)-3 correspondingly showed similar trends. Qualitative analyses of the results allowed the assignment of (2S, 4S, 2′S, 4′S)-configuration for 1, (2S, 4S, 2′S)-configuration for 2, and (2S, 2′S)-configuration of 3, respectively.

Preparation of single crystals and crystal structure determination of 1 and 2

Methanol was used as the solvent to make a saturated solution of 1 and 2 (if it is not completely dissolved, it can be completely dissolved by ultrasound, and then cooled down after reaching saturation). The saturated solution was sealed with a thin film with 2–3 holes and left at 4 °C to make the solvent evaporate slowly until crystal precipitation. Finally, colorless transparent cube 1 and 2 crystals were obtained, and the crystal structure was analyzed by X-ray single-crystal characterization.

A suitable crystal was selected and placed on a diffractometer. The crystal of 1 was kept at 170.00 K during data collection. Using Olex247, the structure was solved with the SHELXT48 structure solution program using Intrinsic Phasing and refined with the SHELXL48 refinement package using Least Squares minimization. The crystal of 2 was kept at 250.15 K during data collection. Using Olex2, the structure was solved with the olex2.solve49 structure solution program using Charge Flipping and refined with the XL50 refinement package using Least Squares minimization.

Crystal data for C12H22N2O4 (M = 258.31 g × mol−1): monoclinic, space group P21 (no. 4), a = 10.1134(5) Å, b = 7.1301(3) Å, c = 19.1280(9) Å, β = 90.254(2)°, V = 1379.30(11) Å3, Z = 4, T = 170.00 K, μ(GaKα) =0.491 mm−1, Dcalc = 1.244 g × cm−3, 21,025 reflections measured (7.606° ≤ 2Θ ≤ 132.902°), 6780 unique (Rint = 0.0456, Rsigma = 0.0521) which were used in all calculations. The final R1 was 0.0388 (I > 2σ(I)) and wR2 was 0.0997. Crystal Data for C11H20N2O4 (M = 244.29 g × mol−1): orthorhombic, space group P212121 (no. 19), a = 6.7650(2) Å, b = 9.4925(4) Å, c = 20.0776(8) Å, V = 1289.32(8) Å3, Z = 4, T = 250.15 K, μ(CuKα) = 0.795 mm−1, Dcalc = 1.258 g × cm−3, 11782 reflections measured (12.834° ≤ 2Θ ≤ 133.424°), 2257 unique (Rint = 0.1571, Rsigma = 0.0779) which were used in all calculations. The final R1 was 0.0836 (I > 2σ(I)) and wR2 was 0.2446.

Simultaneous deletion of ku70 and pyrG gene of A. terreus CMI44339

The positions for double-strand breaks in ku70 and pyrG genes were designed to be near the start and end of gene sequence. Using plasmid pFC902 (Addgene) as the template and the combination of primers (CSN438+ Deletion of ku70-PS1R, Deletion of ku70-PS1F+Deletion of ku70-PS2R, Deletion of ku70-PS2F+Deletion of pyrG-PS1R, Deletion of pyrG-PS1F+Deletion of pyrG-PS2R, Deletion of pyrG-PS2F, CSN790) containing dU bases, five DNA fragments were amplified using Phusion U Hot Start DNA Polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) which were seamlessly cloned by USER51 into vector pFC332 (Addgene) (containing hph resistance gene) double-digested by PacI/Nt.BbvcI. The plasmid pFC332-ATEGku70pyrG was verified by colony PCR and sequencing. Subsequently, it was propagated in E. coli DH5α for plasmid extraction. To construct the ku70 and pyrG repair templates, the gDNA of A. terreus CMI44339 was used as a template to amplify fragments of about 2 kb upstream and downstream of the gene. Among them, the fragments contain sequences to facilitate the fusion PCR reaction with the other fragments. The overhang sequence GGGTTTAAU- was added to the forward primer, and the extended sequence GGTCTTAAU- was added to the reverse primer. One microliter fusion PCR reaction was taken as the template. The modified nested PCR reaction was performed using a designed PCR primer containing one base dU and Phusion U hot start DNA polymerase, and the PCR reaction products were purified. The length of the target fragment was about 4 kb. Plasmid pUC57_500 was integrated into a 500-bp DNA fragment containing PacI/Nt.BbvcI digestion sites based on the universal plasmid pUC5727. After modification, PacI/Nt.BbvcI double digestion and purification were performed before USER transformation. The products of the final nested PCR reaction were seamlessly cloned to the enzyme-digested vector pUC57_500 by USER, and then colony PCR and sequencing were performed to obtain two plasmids PUC57_500-KU70UPdW and PUC57_500-PyrGUPDW which then were propagated in E. coli DH5α for plasmid extraction.

Filamentous fungi protoplasts preparation and transformation were performed as described by Xiong et al.52 with some modifications. A. terreus protoplastation: 2.2 g VinoTaste® Pro powder was added into solution I (20 mL, 0.6 M KCl), mixed evenly, filtered and sterilized; fresh mycelia cultured in AMM liquid medium (per liter, 10 g Glucose, 6 g NaNO3, 0.52 g KCl, 0.52 g MgSO4·7H20, 1.52 g K2HPO4, 1 mL trace elements) was transferred to the protoplastation solution and incubated at 28 °C and 90 rpm for 2–4 h. The lytic mixture was then filtered through a 40 µm filter, and the filtrate was centrifuged at 3500 rpm at 4 °C for 10 min. Solution II (0.6 M KCl, 50 mM CaCl2) was added to the sediment, washed twice, and then re-suspended in 1 mL ATB (1.2 M Sorbitol, 50 mM CaCl2, 20 mM Tris, 0.6 M KCl, pH 7.2).

For protoplast transformation, the CRISPR plasmid pFC332-ku70pyrG and the template plasmids pUC57_500-ku70updw and pUC57_500-pyrGupdw were added to 100 µL fresh protoplasts, respectively. Then 150 µL pre-cooled PCT solution (50% w/v PEG8000, 50 mM CaCl2, 20 mM Tris, pH 7.5) was added and gently mixed. After reaction at room temperature for 10 min, 250 µL ATB solution (1.2 M Sorbitol, 50 mM CaCl2, 20 mM Tris, 0.6 M KCl, pH 7.2) was added, mixed and evenly plated on ATM plate (per liter, 1 M Sorbitol, 6 g NaNO3, 0.815 g KH2PO4, 1.045 g K2HPO4, 10 g Glucose, 20 g Agar, 1 mL trace elements, 2.5 mL 20% MgSO4) containing 100 µg × mL−1 hygromycin, 10 mM uracil and uridine28. After 5 days of incubation, the colonies were transferred to a new plate containing 100 µg × mL−1 hygromycin and 10 mM uracil and uridine for 3 generations, and gDNA of stable resistant transformants was selected for PCR verification. The double mutant strain was selected for spore streak plating until the homozygous double mutant was isolated and named strain ATEG002.

Deletion of biosynthesis genes and LC-MS analysis

On the basis of mutant strain ATEG002 (Δku70, ΔpyrG), five NRPS genes and four P450 genes were deleted, respectively. For each CRISPR plasmid, Phusion U hot-start DNA polymerase was used to obtain three DNA fragments containing U bases, using plasmid pFC902 as a template. These fragments were seamlessly cloned by USER into PacI/Nt.BbvcI -digested plasmid pFC330 (containing pyrG gene), and verified by PCR and sequencing. The constructed plasmids pFC330-NRPS17.2, pFC330- NRPS18.3, pFC330-NRPS23.3, pFC330-NRPS25.1, pFC330-NRPS36.1, pFC330-ATEGP45018.3-1, pFC330-P45018.3-2, pFC330-P45023.3, pFC330-NRPS25.1 were propagated in E. coli DH5α for plasmid extraction. The protoplast transformation process refers to the above operation, except for the following two differences: 1. General ATM plate screening without any antibiotics and nutrients; 2. The repair template is 90 nt, where 45 nt is upstream of the gene and 45 nt is downstream of the gene. After incubation at 30 °C for about 3 days, monoclonal colonies were selected to extract gDNA for PCR and sequencing verification.

The mutant strains successfully constructed were named ATEG003-011. The above mutants were subsequently cultured to extract metabolites for LC-MS analysis.

Construction of heterologous expression system

Heterologous expression system in A. nidulans was performed according to Tang et al.43. The target genes tamA and tamB were amplified using gDNA of A. terreus CMI44339 as templates, respectively. The transformation plasmid of A. nidulans was constructed by homologous recombination. The amplified genes were inserted into vectors pANR (riboB, 0.125 µg × mL−1 Riboflavin), pANP (pyroA, Pyridoxine HCl), pANU (pyrG, 10 mM Uridine + 5 mM Uracil) containing nutritional markers. Transformation plasmid and 100 µL of protoplasts were mixed, placed on ice for 60 min, and then 600 µL PEG solution (60% PEG6000, 50 mM CaCl2, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5) was added. After incubating for 20 min at room temperature, the mixture was spread on CD plates containing the corresponding markers. After 1–2 days of incubation at 37 °C, monoclonal colonies were selected and incubated in CD-ST medium at 28 °C, 220 rpm for 5 days, and then the fermentation solution was extracted for LC-MS analysis.

Effects of amino acid feeding and iron chelator feeding on terramides pathway gene level and terramides production

Here, 10 mM valine/isoleucine and 20 μM bathophenanthrolinedisulfonic acid were added to the terramide production medium. Total RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer’s protocol of the RNeasy Plant Mini kit (Qiagen). Reverse transcription was performed using the Prime Script RT Reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (TaKaRa, Japan). Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) was conducted using TB Green Premix Ex Taq II (TaKaRa, Japan) on a Bio-Rad CFX96 real-time PCR system, following the program: 95 °C for 30 s/40 cycles at 95 °C for 5 s/60 °C for 30 s. Gene relative expressions were calculated by the 2−△△comparative critical threshold (CT) method and were normalized to tubulin gene expression. The PCR primers are shown in Table S14.

Determination of minimum bacteriostatic concentration

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of terramides against A. baumannii was measured using the microbroth dilution method recommended by CLSI (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2017 edition). First, the target compound was dissolved in a sterilized LB liquid medium and double diluted on a 96-well cell culture plate, then inoculated in an equal volume of bacterial suspension with a concentration of 106 CFU × mL−1. At the same time, negative and positive control groups were set up and then cultured in an incubator at 37 °C for 16–18 h. When the absorbance difference with negative control group is less than 0.05, the corresponding compound concentration is considered as the minimum inhibitory concentration. Relative anti-A. baumannii activity was determined by measuring the diameter of the antibacterial zone and comparing to that of ampicillin.

Detection of siderophore

CAS (Chrome azurol S) test solution is a complex made of chrome azurol sulfonate, hexadecy-ltrimethyl-ammonium bromide and iron ions in a bright blue color. When the iron ion of the blue detection solution is bound by the siderophore, the detection solution turns red. CAS testing was performed according to the instructions of Modified CAS Agar Medium Kit (PM0821-2, Coolabar, Beijing). Appropriate amount of compounds was taken and mixed with CAS detection solution. After leaving it in the dark for 30 min, the absorption value (As) at 630 nm was measured, and methanol was used as blank. The light absorption value of CAS detection solution was used reference ratio (Ar), and the relative content of siderophore was obtained according to the formula [(Ar-As)/Ar] × 100%. The relative content of 1, 2, and 3 at the same concentration were 62.06% ± 1.11, 53.20% ± 0.82 and 47.95% ± 1.00, respectively, among which 1 had the best chelating ability with iron ion.

FT-IR and EPR detection

The IR spectra was recorded using a Nicolet iS50 Fourier transform infrared spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) with a frequency range of 4000–400 cm−1. The Raman detection was performed using a XploRA Plus automatic microscopic Raman spectrometer (Horiba, France). The EPR detection was performed by ESRA-300 electronic paramagnetic resonance spectrometer (Bruker, Germany).

Murine infection models

The experiment was conducted in accordance with the Guidelines for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of Zhejiang University and approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Zhejiang University (protocol number ZJU20220150).

Six to eight-weeks-old CD1 female mice (23 ± 2 g, Slac Laboratory Animal Co. Ltd.) were kept in a sanitized environment under the specific conditions (temperature: 24 °C, humidity: 55 ± 10%, light: 12 h light/dark cycle) with sterile water and standard basal diet. A. terreus strains and ΔtamA strain were grown on malt extract agar (MAG) at 28 °C for 5 days. Fresh conidia were collected via flooding with PBS-T and counted using a Neubauer chamber. The mice were randomly divided into four groups (12 mice in each group): A. terreus wild-type, Δku70ΔpyrG, ΔtamA and PBS groups. The mice were immunosuppressed with cortisone acetate (Aladdin, 1 mg × g−1), which was injected intraperitoneally 3 days before and immediately prior to the infection with conidia (day 0). The immunosuppressed mice anesthetized with tribromoethanol (Aladdin, 125–250 mg × kg−1, IP) were infected via the tracheal instillation of suspensions of 1.0 × 106 conidia in 20 μL PBS solution, PBS tracheal instillation was applied as a negative control. Mortality was monitored for 14 days. Statistical significance was assessed using a one-way ANOVA test with multiple comparisons. The lungs of infected and mock-infected mice (1.10 g/mouse) were collected and grinded with liquid nitrogen and extracted with ethyl acetate three times (10 mL), the organic layer was concentrated and the residual dissolved with methanol (50 μL) for LC-MS analysis.

Histopathology

The lungs of mice were resected and fixed in 10% formalin buffer, sectioned (5 μm), dehydrated, paraffin-embedded, stained with GMS (Grocott’s methenamine silver), then photographed with a microscope (Olympus CK53).

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

Y.G. discloses support for the research of this work from the International Postdoctoral Exchange Fellowship Program (Talent-Introduction Program) of the Office of China Postdoc Council (OCPC) (grant number. YJ20210168) and the Zhejiang Provincial Postdoctoral Research Project (grant number ZJ2022084). We thank Professor Yi Tang (UCLA) and Professor Berl R. Oakley (University of Kansas) for providing the A. nidulans expression system. We acknowledge Yanwei Li from the Core Facilities, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, for technical support. Jianyang Pan from Research and Service Center, College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Zhejiang University for NMR analysis, Dan Wu from Research and Service Center, College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Zhejiang University for help with HR-ESI-MS, Jiyong Liu from Chemical Analysis Center, College of Chemistry, Zhejiang University for help with crystal structure determination. Lijuan Mao from the Analysis Center of Agrobiology and Environmental Sciences, Zhejiang University, for help with FT-IR analysis. Chen Chen from the Chemical Experimental Teaching Demonstration Center, College of Chemistry, Zhejiang University, for help with Raman spectroscopy analysis. Xinyu Wang from Chemical Analysis Center, College of Chemistry, Zhejiang University, for help with EPR analysis.

Author contributions

Yi Han, Yaojie Guo: Investigation, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data provision and curation, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing, Funding acquisition. Nan Zhang: Investigation, Data provision. Fan Xu: Investigation. Jarukitt Limwachiranon: Funding acquisition. Zhenzhen Xiong: Validation. Liru Xu: Investigation. Xu-Ming Mao: Resources. Daniel H. Scharf: Conceptualization, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Writing-review & editing. Yi Han and Yaojie Guo contributed equally to this work. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks Trevor Clark and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Data availability

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information and supplementary data files. Supplementary Data 1: Figures original data. Supplementary Data 2: The cif files of compounds 1 and 2. The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this Article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers CCDC 2340113, 2380314. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. Supplementary Data 3: NMR spectra.

Code availability

The code used for the simulations is available from the authors upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Yi Han, Yaojie Guo.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s42004-024-01311-2.

References

- 1.Maio, N. et al. Mechanisms of cellular iron sensing, regulation of erythropoiesis and mitochondrial iron utilization. Semin. Hematol.58, 161–174 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee, J. Y. et al. Biosynthetic analysis of the petrobactin siderophore pathway from Bacillus anthracis. J. Bacteriol.189, 1698–1710 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu, W., Liang, Y. & Si, X. Hydroxamic acid hybrids as the potential anticancer agents: an overview. Eur. J. Med. Chem.205, 112679 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haas, H. Fungal siderophore metabolism with a focus on Aspergillus fumigatus. Nat. Prod. Rep.31, 1266–1276 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silva, M. G. et al. Molecular characterization of siderophore biosynthesis in Paracoccidioides brasiliensis. IMA Fungus11, 11 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schrettl, M. et al. Siderophore biosynthesis but not reductive iron assimilation is essential for Aspergillus fumigatus virulence. J. Exp. Med.200, 1213–1219 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swayambhu, G., Bruno, M., Gulick, A. M. & Pfeifer, B. A. Siderophore natural products as pharmaceutical agents. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol.69, 242–251 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schalk, I. J. Siderophore-antibiotic conjugates: exploiting iron uptake to deliver drugs into bacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Infect.24, 801–802 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al Shaer, D., Al Musaimi, O., de la Torre, B. G. & Albericio, F. Hydroxamate siderophores: natural occurrence, chemical synthesis, iron binding affinity and use as Trojan horses against pathogens. Eur. J. Med. Chem.208, 112791 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnstone, T. C. & Nolan, E. M. Beyond iron: non-classical biological functions of bacterial siderophores. Dalton Trans.44, 6320–6339 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tonziello, G., Caraffa, E., Pinchera, B., Granata, G. & Petrosillo, N. Present and future of siderophore-based therapeutic and diagnostic approaches in infectious diseases. Infect. Dis. Rep.11, 8208 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khasheii, B., Mahmoodi, P. & Mohammadzadeh, A. Siderophores: importance in bacterial pathogenesis and applications in medicine and industry. Microbiol. Res.250, 126790 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobs, A. Iron chelation therapy for iron loaded patients. Br. J. Haematol.43, 1–5 (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Entezari, S. et al. Iron chelators in treatment of iron overload. J. Toxicol. 2022, 4911205 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Luptáková, D. et al. Siderophore-based noninvasive differentiation of Aspergillus fumigatus colonization and invasion in pulmonary aspergillosis. Microbiol. Spectr.11, e0406822 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petrik, M., Pfister, J., Misslinger, M., Decristoforo, C. & Haas, H. Siderophore-based molecular imaging of fungal and bacterial infections—current status and future perspectives. J. Fungi6, 73 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pfister, J., Lichius, A. & Summer, D. Live-cell imaging with Aspergillus fumigatus-specific fluorescent siderophore conjugates. Sci. Rep.10, 15519 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garson, M. J., Jenkins, S. M., Staunton, J. & Chaloner, P. A. Isolation of some new 3,6-dialkyl-I.4-dihydroxypiperazine-2, 5-diones from Aspergillus terreus. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans.1, 901–903 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kinoshita, H., Yoshioka, M., Ihara, F. & Nihira, T. Cryptic antifungal compounds active by synergism with polyene antibiotics. J. Biosci. Bioeng.121, 394–398 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qi, J., Chen, C., He, Y. & Wang, Y. Genomic analysis and antimicrobial components of M7, an Aspergillus terreus strain derived from the South China Sea. J. Fungi8, 1051 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miceli, N., Kwiecień, I. & Nicosia, N. Improvement in the biosynthesis of antioxidant-active metabolites in in vitro cultures of Isatis tinctoria (Brassicaceae) by biotechnological methods/elicitation and precursor feeding. Antioxidants12, 1111 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haas, H. Iron—a key nexus in the virulence of Aspergillus fumigatus. Front. Microbiol.3, 28 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blin, K., Shaw, S. & Kloosterman, A. M. antiSMASH 6.0: improving cluster detection and comparison capabilities. Nucleic Acids Res.49, W29–W35 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang, X. et al. Cytochrome P450 enzymes in fungal natural product biosynthesis. Nat. Prod. Rep.38, 1072–1099 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zahid, S. et al. The multifaceted roles of Ku70/80. Int. J. Mol. Sci.22, 4134 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eom, H. et al. The Cas9-gRNA ribonucleoprotein complex-mediated editing of pyrG in Ganoderma lucidum and unexpected insertion of contaminated DNA fragments. Sci. Rep.13, 11133 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nødvig, C. S., Hoof, J. B. & Kogle, M. E. Efficient oligo nucleotide mediated CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing in Aspergilli. Fungal Genet. Biol. 115, 78–89 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Nødvig, C. S., Nielsen, J. B., Kogle, M. E. & Mortensen, U. H. A CRISPR-Cas9 system for genetic engineering of filamentous fungi. PLoS ONE10, 1–18 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo, Y. J. et al. Biosynthesis of calipyridone A represents a fungal 2‑pyridone formation without ring expansion in Aspergillus californicus. Org. Lett.24, 804–808 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chiang, Y. M., Ahuja, M. & Oakley, C. E. Development of genetic dereplication strains in Aspergillus nidulans results in the discovery of aspercryptin. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl.55, 1662–1665 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kruft, B. I., Harrington, J. M., Duckworth, O. W. & Jarzęcki, A. A. Quantum mechanical investigation of aqueous desferrioxamine B metal complexes: trends in structure, binding, and infrared spectroscopy. J. Inorg. Biochem.129, 150–161 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siebner-Freibach, H., Yariv, S., Lapides, Y., Hadar, Y. & Chen, Y. Thermo-FTIR spectroscopic study of the siderophore ferrioxamine B: spectral analysis and stereochemical implications of iron chelation, pH, and temperature. J. Agric. Food Chem.53, 3434–3443 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mak, P. J., Thammawichai, W., Wiedenhoeft, D. & Kincaid, J. R. Resonance Raman spectroscopy reveals pH-dependent active site structural changes of lactoperoxidase compound 0 and its ferryl heme O-O bond cleavage products. J. Am. Chem. Soc.137, 349–361 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cozar, O. et al. IR, Raman and surface-enhanced Raman study of desferrioxamine B and its Fe (III) complex, ferrioxamine B. J. Mol. Struct.788, 1–3 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Racolta, D. et al. Influence of the structure on magnetic properties of calcium-phosphate systems doped with iron and vanadium ions. Int. J. Mol. Sci.24, 7366 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lass-Flörl, C., Dietl, A. M., Kontoyiannis, D. P. & Brock, M. Aspergillus terreus species complex. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 34, e0031120 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Steinbach, W. J. et al. Infections due to Aspergillus terreus: a multicenter retrospective analysis of 83 cases. Clin. Infect. Dis.39, 192–198 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scharf, D. H., Heinekamp, T. & Brakhage, A. A. Human and plant fungal pathogens: the role of secondary metabolites. PLoS Pathog.10, e1003859 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Happacher, I., Aguiar, M., Yap, A., Decristoforo, C. & Haas, H. Fungal siderophore metabolism with a focus on Aspergillus fumigatus: impact on biotic interactions and potential translational applications. Essays Biochem.67, 829–842 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lebar, M. D., Cary, J. W. & Majumdar, R. Identification and functional analysis of the aspergillic acid gene cluster in Aspergillus flavus. Fungal Genet. Biol.116, 14–23 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Neilands, J. B. Hydroxamic acids in nature. Science156, 1443–1447 (1967). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Giessen, T. W. & Marahiel, M. A. Rational and combinatorial tailoring of bioactive cyclic dipeptides. Front. Microbiol.6, 785 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yee, D. A. & Tang, Y. Investigating fungal biosynthetic pathways using heterologous gene expression: Aspergillus nidulans as a heterologous host. Methods Mol. Biol.2489, 41–52 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spartan 18 (Wavefunction, Inc.). (2018).

- 45.Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian 09, Revision A.1. (Gaussian, Inc., 2009).

- 46.Stephens, P. J. & Harada, N. ECD Cotton effect approximated by the Gaussian curve and other methods. Chirality22, 229–233 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dolomanov, O. V. et al. OLEX2: a complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Crystallogr.42, 339–341 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sheldrick, G. M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. C71, 3–8 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bourhis, L. J. et al. The anatomy of a comprehensive constrained, restrained refinement program for the modern computing environment—Olex2 dissected. Acta Crystallogr.A71, 59–75 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sheldrick, G. M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr.A64, 112–122 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nour-Eldin, H. H., Geu-Flores, F. & Halkier, B. A. Plant secondary metabolism engineering. Methods Mol. Biol.643, 185–200 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xiong, Z. et al. Urease of Aspergillus fumigatus is required for survival in macrophages and virulence. Microbiol. Spectr. 11, e0350822 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information and supplementary data files. Supplementary Data 1: Figures original data. Supplementary Data 2: The cif files of compounds 1 and 2. The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this Article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers CCDC 2340113, 2380314. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. Supplementary Data 3: NMR spectra.

The code used for the simulations is available from the authors upon request.