Abstract

Since its inception 30 years ago, Photovoice has gained increasing popularity as a research method and more recently has been incorporated within randomized controlled trial (RCT) designs. Photovoice is a participatory action research method that pairs photography with focus group discussions to record community strengths and concerns, build critical consciousness, and reach policymakers. Adherence of Photovoice implementation to these original tenets of Photovoice varies. This article provides the Photovoice protocol developed by the authors to improve the methodological rigor of Photovoice integration into RCTs and help contextualize the landscape for the HEALing Communities Study (HCS: NCT04111939), a greater than $350 million investment by the National Institute on Drug Abuse along with the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration to reduce opioid overdose deaths in 67 of the hardest-hit communities in four states (Kentucky, Massachusetts, New York, and Ohio). The product of a cross-state collaboration, this HCS Photovoice protocol provides ethical and methodological tools for incorporating Photovoice into RCT designs to enhance community engagement, communication campaigns, and data-driven decision-making about evidence-based practice selection and implementation.

Keywords: Photovoice, participatory action research, opioid crisis, people with lived experience

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Photovoice: Goals and Use Cases

Since its introduction by Caroline Wang and Mary Ann Burris more than 30 years ago, Photovoice has become a commonly used participatory action research (PAR) approach. The goals of Photovoice as envisioned by Wang and Burris are “1) to enable people to record and reflect their community’s strengths and concerns; 2) to promote critical dialogue and knowledge sharing about important issues through large and small group discussion of photographs; and 3) to reach policymakers” (Wang & Burris, 1997a). Researchers have applied Photovoice in several different fields (Suprapto et al., 2020) and tailored to various use cases. In a recent review, these reported uses included: 1) a “photovention” supporting improvements in individual-level knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, skills, and self-efficacy; 2) a participatory community needs assessment tool; 3) a community capacity-building initiative to increase decision maker awareness of prioritized health issues; and 4) a mechanism for policy, programmatic, and systems change (Strack et al., 2022).

1.2. Photovoice in Randomized Controlled Trials

An additional use is the incorporation of Photovoice into randomized controlled trails (RCTs), which has been limited and varies widely. The addition of Photovoice into RCTs has included it as an exploratory qualitative method (Kohrt et al., 2018) and as the qualitative arm of a larger mixed-methods study (Martinez et al., 2020). Notably, one study used Photovoice both as formative work to inform intervention content and later as part of the intervention (Quintiliani et al., 2015). A growing number of RCTs use concepts from Photovoice as part of interventions to change individual health behaviors related to a variety of health issues (Baig et al., 2015; Bylander, 2021; Moore et al., 2022; Rosas et al., 2015; Russinova et al., 2014; Russinova, Gidugu, et al., 2018; Sessford et al., 2022; Singh et al., 2020). These studies apply aspects of the method to achieve more therapeutic goals, in the vein of “photovention.” A few studies have reported results from Photovoice projects as an exposure in a treatment-control evaluation to compare perspectives of stigma among those who experienced a Photovoice exhibit with those who did not (Flanagan et al., 2016; Tippin & Maranzan, 2022). Common among these RCTs, Photovoice is employed at prescriptively specific but variable points during the intervention period. Additionally, there are limitations to existing Photovoice research, as outlined in a 2022 review covering three decades of Photovoice literature reviews (Seitz & Orsini, 2022): inconsistent adherence to the tenets of PAR that stipulate participants should be engaged in every step of the Photovoice project (Golden et al., 2015); a lack of evaluation of Photovoice outcomes, impacts, and exhibit audience characteristics (Liebenberg, 2022; Seitz & Orsini, 2022; Teti & Myroniuk, 2022); and inadequate efforts to embed appropriate ethical procedures at every step (Seitz & Orsini, 2022). Herein we propose a Photovoice protocol addressing these limitations that supplements an RCT intervention with contextual information to inform implementation at any point of its delivery.

1.3. Photovoice in Substance Use Disorder Research

Researchers have theorized that Photovoice may promote empowerment via dissemination efforts that move participants and audiences through the four stages of critical consciousness-raising, from passive adaptation to their communities’ health issues to emotional engagement and root-cause analysis of those issues, leading to the intention to change those issues and transformative social action (Carlson et al., 2006; Matthews, 2014; Teti & Myroniuk, 2022). Because of the consciousness-raising and empowerment goals of the method, Photovoice is ideal for understanding the experiences of marginalized and/or socially stigmatized groups who have unique insights into their conditions, related social determinants of health, and possibilities for health improvement that researchers may not possess (Wang & Burris, 1997b). Researchers have employed Photovoice with numerous minoritized and stigmatized groups, such as HIV+ individuals, gender non-binary young adults, people with mental illness, and people with substance use disorder (SUD) (Cosgrove et al., 2021; Davtyan et al., 2016; Martinez et al., 2020; Russinova, Mizock, et al., 2018; Van Steenberghe et al., 2021).

People with lived experience (PWLE) of SUD represent a particularly stigmatized group in the U.S. and internationally (Yang et al., 2017). Given the severity of the opioid epidemic in the U.S., which has claimed more than a half million lives since 2000 (Mattson et al., 2021), learning from PWLE of opioid use disorder (OUD) and those who work directly with them can provide unique insight into OUD, the local context, and strategies and resources needed to prevent overdoses and support recovery. Only a small number of studies have used Photovoice to consult people with SUD in order to understand contexts and factors influencing recovery (Cabassa et al., 2013; De Seranno & Colman, 2022; Mizock et al., 2014; Muroff et al., 2023; Smith et al., 2022; Van Steenberghe et al., 2021). Yet, people who inject drugs have expressed interest in sharing their experiences through Photovoice (Drainoni et al., 2019). The nuanced knowledge about recovery challenges generated by this small but significant Photovoice literature on SUD and the acceptability of Photovoice to people with OUD indicate that Photovoice is an underutilized tool in OUD research and RCTs.

1.4. Complementing the HEALing Communities Study RCT with Photovoice

1.4.1. Parent RCT

The HEALing Communities Study (HCS: NCT04111939) offered a unique opportunity to design a rigorous protocol for the complementary, flexible use of Photovoice in an OUD-related RCT. In 2019, the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) invested more than $350 million in the HCS to reduce opioid overdose fatality in heavily impacted communities (Chandler et al., 2020). The multi-site cluster randomized trial includes 67 communities in four research sites: Kentucky, Massachusetts, New York, and Ohio. The HCS protocol has been published elsewhere (Walsh et al., 2020). HCS employs the Communities That HEAL (CTH) intervention, which is guided by three pillars: community engagement, the selection and implementation of evidence-based practices (EBPs), and communications campaigns (Walsh et al., 2020). HCS staff randomized communities to receive the CTH intervention as part of Wave 1 (i.e., randomized to receive the CTH intervention first) or Wave 2 (i.e., delayed intervention reception). Community engagement in the CTH involves a phased coalition planning process (Sprague Martinez et al., 2020), during which coalitions collectively discuss and make intervention selection and implementation decisions (Young et al., 2022). A member from each local coalition as well as current or former local- or state-level policymakers serve on each site’s state-level Community Advisory Board (CAB) to provide guidance on study implementation. Coalitions select EBPs from a menu of Opioid-overdose Reduction Continuum of Care Approach (ORCCA) options using data to inform their decisions (Winhusen et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020). Examples of EBPs in the ORCCA include overdose education and naloxone distribution and linkage to medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) treatment. Coalitions implement study-specific communications campaigns to drive uptake of EBPs and reduce stigma about OUD in communities (Lefebvre et al., 2020).

1.4.2. Adding Context to the CTH Intervention with Photovoice

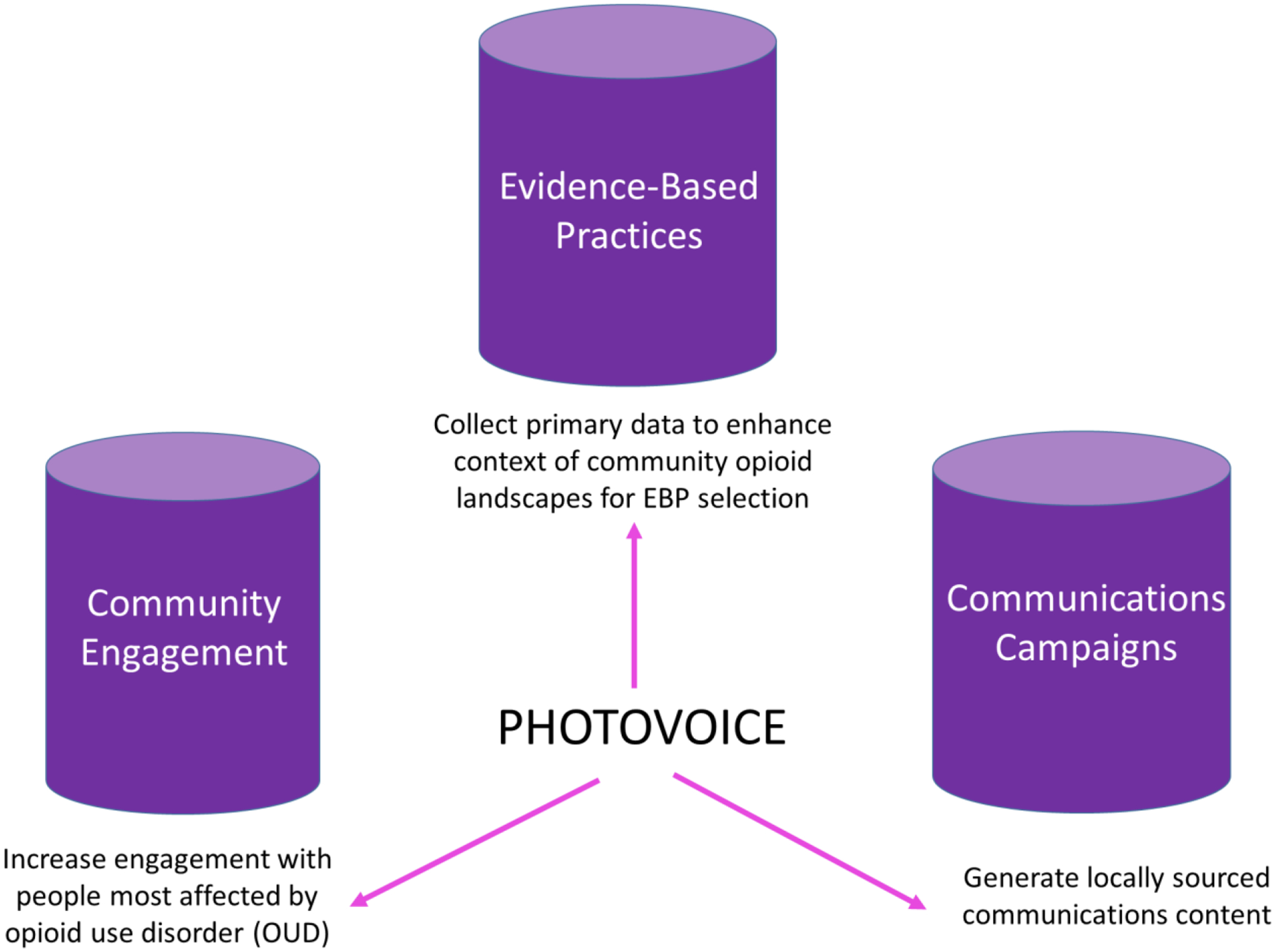

The authors proposed Photovoice as an optional tool that can complement and provide community-specific context to enhance any of the three CTH pillars at any phase in the RCT, such as 1) increasing the engagement of community members most affected by OUD; 2) collecting additional primary, local data to inform EBP selection, implementation, uptake, and sustainability; and 3) producing locally sourced photographs and qualitative quotes to support community-tailored communications messaging and material development (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Photovoice augments the three pillars of the CTH.

Although Photovoice neither is a core process of the RCT nor spans the life of the RCT, Photovoice can be a useful supplement at any phase of the CTH for different of reasons (Figure 2). The early CTH phases are dedicated to building coalitions and CABs and introducing members to the community context through data. By engaging people most affected by the opioid epidemic, including PWLE of OUD, families of people with OUD, and front-line workers, Photovoice may help coalitions gain diverse and equitable community perspectives. These unique and valuable data can help elucidate gaps and opportunities in the continuum of care and inform intervention selection and community-tailored communications efforts. The Photovoice process also creates bonds among participants and facilitators that may increase community engagement across the planning process. During later phases of the CTH intervention, Photovoice can contextualize OUD service delivery and inform how EBPs could be modified to increase uptake. The community engagement structure of HCS comprising community-specific coalitions and state-level CABs offers ideal fora for exhibiting Photovoice products to decision-makers for the study and OUD policymaking in each state more generally. Discrete Photovoice projects undertaken at any point of the CTH timeline can contribute to defining a community’s context and evolving needs for addressing the opioid epidemic to support sustainability planning, including supplying primary data for grant applications.

Figure 2:

HEALing Communities Study CTH phases (Sprague Martinez et al., 2020; Walsh et al., 2020) and phase-specific activities with purple boxes indicating how Photovoice could complement work in the phase.

In this protocol paper, we explain the incorporation of a Photovoice protocol that adheres to the three original goals of the method (Wang & Burris, 1997a) while affording CTH intervention implementation partners the opportunity to gather community-sourced data to help contextualize the opioid epidemic locally and focus response efforts at any point in CTH’s phased RCT design. We detail how these optional Photovoice projects can be used to gather contextual information from participating communities at any phase within the HCS RCT in a methodologically uniform but logistically adaptable way across study sites that ensures the rigor of Photovoice implementation, particularly in terms of adherence to the method, evaluation, and ethical procedures. A toolkit to promote implementation of the protocol in future studies and RCTs accompanies this article (see Appendix Toolkit).

2. METHODS

2.1. Ethics and Feasibility of Photovoice as a Tool in the HCS RCT

The approval and integration of the Photovoice protocol into the HCS require ethical consideration to meet the standards of a large RCT. Because Photovoice was not initially part of the study design, authors needed approval prior to developing this protocol. Thus, as a first step, the authors presented the Photovoice method and proposed an integration plan described herein to the HCS Steering Committee for approval. The HCS Steering Committee is the decision-making body for the study and comprises Principal Investigators and Project Directors from the four sites, plus the coordinating center (RTI International), and NIDA senior study leadership. As a contingency of approval, Photovoice could be used as a tool to contextualize the opioid epidemic in communities but not an intervention in and of itself to prevent threats to the validity of the CTH. As the incorporation of Photovoice into the HCS RCT is neither an intervention nor an RCT, this protocol paper follows applicable STROBE checklist guidelines for cross-sectional studies (i.e., checklist items that are not related to reporting on data collected using the protocol, which is not within the scope of this manuscript).

Prior to IRB approval and broad implementation in participating HCS sites, one community in Massachusetts tested a pilot Photovoice project to assess feasibility and refine procedures. HCS community-embedded research staff were interested in how Photovoice could uncover and address how stigma may be influencing the uptake of a newly implemented MOUD service. Pilot Photovoice participants were all PWLE recruited from a recovery center within the community. The pilot consisted of seven sessions, including an orientation, five photo discussion sessions, and a final session to discuss dissemination. Based on the pilot, HCS-PW confirmed the feasibility and benefits of using Photovoice to support the CTH pillars and further refined the HCS Photovoice protocol by reducing the number of photo discussions to increase participant retention. Pilot data are not included because this formative project was not covered by the IRB protocol.

Following HCS Steering Committee approval and the Massachusetts pilot, authors from the Massachusetts, Kentucky, and Ohio sites formed a cross-site HCS Photovoice Workgroup (HCS-PW). New York did not participate due to budget and scheduling constraints. The HCS-PW collaboratively designed a common protocol. Using this protocol, the HCS-PW received approval from the central Institutional Review Board (IRB; Advarra Inc.) to ensure human subject protection; all described protocols were IRB-approved.

2.2. Photovoice Facilitation

In this protocol, members of the HCS-PW meet regularly to develop shared processes, discuss site-specific progress, troubleshoot challenges, and coordinate cross-site analysis and dissemination. HCS-PW members are experienced Photovoice facilitators who lead Photovoice discussion sessions or conduct trainings to support less experienced staff. Photovoice is facilitated by HCS staff with prior experience in the method or community-embedded staff who have undergone training in Photovoice facilitation. The train-the-facilitator model involves multiple training sessions on all aspects of Photovoice and includes general information on qualitative and PAR methods, focus group facilitation, and interim analysis (see Appendix Toolkit for orientation and focus group guiding materials). Sites offer weekly office hours to supplement training and support community-embedded staff through the research process.

2.3. Photovoice Implementation

Photovoice is an optional tool available to be implemented in HCS communities during any phase of the CTH. The HCS Photovoice protocol allows for up to six sessions, including an orientation, between two and four photo discussion sessions, and a final session to determine project dissemination content and approach. A facilitator schedules and runs each session. The scheduling of sessions is designed to be flexible, although facilitators are encouraged to schedule sessions at least a week apart, allowing time for participants to take photos and facilitators to review and synthesize information from the prior session. Participants develop photo-topics related to the opioid epidemic in their community, take representative photos between sessions, and engage in facilitated discussions with photos serving as prompts for critical dialogue. Sessions, which may be held in-person or virtually using a video conferencing platform, last up to two hours. Site-specific compensation ranges from $25–50 in gift cards per session.

2.3.1. Participant Recruitment

The HCS Photovoice protocol limits participation in each HCS community-based Photovoice project to 16 individuals per community; each Photovoice group session is capped at eight participants to maximize inclusive conversation. We encourage maintaining the same participants across sessions as a way to increase comfortability and open conversation among participants. For recruitment, the protocol recommends seeking community-specific key informants with insight into the localized opioid epidemic, including members of local coalitions and those they work with and serve. These key local informants may be PWLE of opioid use, family and friends of people with OUD, behavioral health providers, addiction treatment providers, public health and social service staff, criminal legal system staff, harm reduction service providers, first responders, members of cultural or faith-based institutions, and others with experience or knowledge of OUD within the community. Photovoice facilitators and HCS community-embedded staff with the support of community-specific coalitions recruit participants through personal connections, local service providers and coalition members, and/or locally relevant social media. These local recruitment methods allow for intentional group formation (i.e., forming multiple smaller groups) to enhance group dynamics and reduce the potential of self-censoring due to power differences among participants (e.g., between PWLE and criminal-legal system staff members). Facilitators contact potential participants who have indicated interest via email, phone, or at an in-person meeting using scripts for each form of engagement (See Appendix Toolkit). Facilitators invite interested individuals to either in-person or virtual sessions based on the mode deemed most accessible to the group members.

2.3.2. Orientation Session

During orientation, Photovoice facilitators first introduce potential participants to the project, explain expectations, and obtain written or oral consent from those interested in participating. HCS-PW members developed an orientation slide deck to introduce the Photovoice method, the Photovoice process in HCS, the ethics of photography (including how to document permission to use identifying photos and strategies for taking photos that do not identify subjects), and informed consent (See Appendix Toolkit). Consent forms include a description of the purpose of the study, participant roles, risks, and benefits associated with participation in the project, and compensation for participating (See Appendix Toolkit). When written consent is not feasible for online sessions, facilitators can allow oral consent and sign unique consent documents for each participant. Participants next fill out the confidential digital or paper demographic survey. Demographic questions include age, gender, race/ethnicity, community, education level, relation, if any, to HCS, and connection to SUD. The purpose of the survey is to enhance comparisons of results across communities and sites (See Appendix Toolkit).

Due to the sensitive nature of the topic and because photography may identify individuals, facilitators educate participants on the ethics of photography consistent with recent recommendations for informed consent in Photovoice projects with people in SUD recovery (Smith et al., 2024). The main goal of this section of the orientation is to ensure that the sharing of photography does not harm anyone involved. Facilitators explain that documented consent is needed if participants want to photograph another person in a way that the subject of the photo is identifiable. However, subject do not need to consent if the photo is taken in such a way that the person is not recognizable. For example, facilitators may encourage participants to be creative in their photography, such as taking a photo of someone’s shadow, a partial body shot, or from a distance to mask identity and mitigate the need for consent. Consent is also not necessary for photos of public figures and groups of people such that the individuals of focus are not recognizable. As a general guideline, facilitators encourage participants to consider whether the focus of their photo is controversial and could be problematic if seen by others and should refrain from taking photographs that could harm the reputation or safety of others.

Next, participants develop photo-topics for photography and discussion sessions using the nominal group technique (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2018). This inclusive and collaborative photo-topic development process assures participant-driven identification of topics they believe to be most pertinent to understanding the opioid epidemic in their community. To ground the group, the Photovoice facilitator 1) refreshes participants on the three primary goals of Photovoice (documenting community strengths and challenges, critically discussing these strengths and challenges, and informing policy-making and action), 2) reminds participants that the overarching focus of the project is the opioid epidemic, then 3) asks participants to consider important factors driving or protecting against the opioid epidemic in their communities. Facilitators then prompt participants to write a list of potential photo-topics silently and independently for a few minutes. To spur creativity, the facilitator may share a few examples of photo-topics that have been used in other OUD-related projects, such as “what stigma looks like in my community,” “hidden populations – who we are missing?”, and “what I wish others knew about addiction.” Group members share what they have written while a Photovoice facilitator documents the collective ideas using chart paper or screenshare. The group then votes on a photo-topic from the generated list for the following Photovoice session. After agreeing on a photo-topic, the facilitator asks for examples of what photos participants plan to take to represent the topic. This prompt can be useful to ensure that the chosen topic is broad enough for varied photography and discussion. At successive discussion sessions, the facilitator displays the photo-topic list again, and participants can suggest additional ideas before a vote on the subsequent photo-topic.

The orientation concludes with the distribution of cameras for photography. Sites have the option to purchase cameras (disposable or digital) or ask participants to use the camera on their mobile device (phone or tablet). If purchased cameras are to be used, then facilitators give a brief tutorial on camera function. Facilitators instruct participants to use the time between sessions to take photographs representative of the photo-topic to share with the group. Facilitators provide directions on how to share photographs using Box university accounts (https://www.box.com/) or Epicollect5 (https://five.epicollect.net/), two HIPAA-compliant platforms where partcipants can share and store photos.

2.3.3. Photovoice Discussion Sessions

The HCS Photovoice protocol allows Photovoice facilitators to offer between two and four photo discussion sessions, based on community interest and site-specific considerations. To begin the session, facilitators instruct participants to share one or two photos they took for the current photo-topic and briefly share 1) what they photographed, 2) why they chose to photograph it, and 3) how it relates to the photo-topic. Upon completion of individual photo sharing, facilitators ask participants to collectively select a photo among all shared that best represents the photo-topic. Selected photo(s) are used as a prompt for a facilitated discussion using the empowerment education-based SHOWeD method of inquiry that explores the meaning of the image as experienced by participants and ends with a brainstorm on how to address the issue at hand (Shaffer, 1985). Researchers have commonly used the SHOWeD method to facilitate Photovoice discussions, dating back to the early years of Photovoice (Strack et al., 2004). The SHOWeD mnemonic prompts include: What do you See here? What is really Happening here? How does this relate to Our lives? Why does this concern, situation, or strength exist? What can we Do about it? Time permitting, participants can select another photo to discuss using the SHOWed questions. Facilitators audio-record all discussions for transcription and analysis.

2.4. Interim Analysis

Building off similar projects (Balvanz et al., 2016; Muroff et al., 2023; Sprague Martinez et al., 2018), the HCS-PW determined that the domains of ecological models provide an excellent structure for documenting what participants say drives the opioid epidemic and what can help address it (McLeroy et al., 1988). Ecological models acknowledge that there are multiple levels of helpful and harmful influences on health behaviors, and these levels interact (Sallis et al., 2015). For our purposes in a community-based study, HCS-PW proposed the Socioecological Model (SEM) with its domains of individual, interpersonal, organizational, community, and policy on which to map these influences (Golden et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2017). Between sessions, facilitators review transcripts, notes, and photographs to document community strengths and concerns related to the domains of the SEM (See Figure 3 for example). In addition to documenting community strengths and concerns according to SEM domains, facilitators note participant responses to the final SHOWeD question, “What can we do?”. While reviewing transcripts, facilitators flag quotes that represent documented community concerns and strengths to be shared at the final session along with participant photography. At the beginning of the next session, Photovoice facilitators report to participants interim analysis results sorted by SEM domains and suggested actionable steps.

Figure 3.

Example of community concerns and strengths related to a potential HCS photo-topic listed by SEM domains

The purposes of these interim analyses are multifold. First, they offer a chance to member-check with participants, allowing researchers to engage participants in confirming the accuracy of qualitative results (Lincoln & Guba, 1986). Community strengths and concerns organized by SEM domains also offer a succinct format to share with coalitions and other decision-makers what participants identify as contextual drivers and protections against the opioid epidemic to inform transformative actions. Additionally, results from these interim analyses may be used to inform preliminary codes for later thematic analysis after final data collection. Finally, this process engages participants in analysis activities per PAR principles.

2.5. Project Dissemination and Next Steps

The final session is designed for participants to strategize how to leverage their project to achieve Wang and Burris’ (1997a) third objective of reaching decision-makers to encourage the adoption of health-promoting policies and awareness of the issue explored through the Photovoice project. In preparation for the final session, Photovoice facilitators consolidate findings from each session onto a single table organized by SEM domains, noting specific actions recommended by participants. Photovoice facilitators then gather participant photographs, strengths and concerns captured on the SEM table, and representative quotes to review with participants. To begin the final session, Photovoice facilitators share the prepared summary materials with participants. Collectively, the group determines what findings they want to prioritize and with whom they will be shared. Facilitators encourage participants to help develop exhibits of results to share with their decision-making HCS partners (e.g., community coalition and/or state-level CAB). Beyond this dissemination step organized by facilitators, facilitators and participants can determine the extent and modes in which they may want to disseminate their materials. Facilitators may suggest additional activities such as holding a local or statewide community forum, creating a photo display with images and quotations from focus groups, or showing video montages of their work in public venues. Participants decide their level of involvement in dissemination activities, affording control of their public disclosure of being a Photovoice participant after contributing de-identified photos and quotes to the group project. The ability to self-determine participation in public forums is important considering the stigma associated with OUD and the potential backlash against Photovoice products documenting community concerns.

Participants are integral to the development of dissemination materials. The HCS-PW developed dissemination materials (e.g., PowerPoint slides, poster templates, postcards) that can be adapted and modified by site to meet the capacities and preferences of participants and facilitators. Facilitators may choose to work with participants to develop a narrative for each photo that collaboratively captures the group’s insight into the topic or work with participants to extract quotes from past session transcripts to accompany photos. For the latter, facilitators compile participant quotes which express specific strengths or concerns by photo-topics into a single document, then assign participants to match photos to the quotes they feel best represent each photo.

The group can decide to present Photovoice content, including visuals with quotes and community concerns and strengths listed by SEM domain, to HCS coalitions and CABs. The resulting Photovoice products thereby represent the engagement of community members deeply affected by the opioid epidemic. As the community’s decision-making body for the HCS, the coalitions and CABs can use Photovoice findings to better understand the community resource landscape, inform EBP selection, and improve EBP implementation. Additionally, coalitions may decide how to leverage Photovoice project products, like posters or videos, to support community-specific communications.

2.6. Dissemination Evaluation

The HCS Photovoice protocol includes a mixed-methods data collection instrument to evaluate the experiences of participants and people who attend events and interact with efforts to disseminate Photovoice project findings. This tool helps address the gap in the Photovoice literature on evaluations of how Photovoice projects contribute to the method’s goals of discussing community strengths and concerns, raising critical consciousness, and reaching policymakers to inspire social change. The instrument gathers demographics, including age, gender, race/ethnicity, education level, and community role in relation to the opioid epidemic, and three Likert-type responses to prompts about the extent to which the project meets Photovoice’s three goals. Participants indicate the extent to which they feel involved with and empowered by their Photovoice work. Finally, there are five open-ended questions for audience members and participants asking them to share two words that describe their Photovoice experience, the most impactful elements of the project, and any intended actions inspired by their Photovoice experiences. The tool can provide insights on participant and audience intentions to act and empowerment related to their involvement in Photovoice as well as feedback to inform protocol implementation improvements and broader HCS community engagement and EBP implementation efforts (See Appendix Toolkit).

2.7. Cross-site Analysis

Cross-site analysis occurs after the completion of Photovoice project sessions and evaluation data collection to explore and categorize the variation in participant photo-topic selection, interim analyses, and transcribed photo discussions across HCS sites. HCS-PW members, their students, Photovoice facilitators, and interested Photovoice participants use the template analysis method to further refine and define themes captured in interim analyses that represent significant features of the data and organize them into a hierarchal structure indicating conceptual relationships among themes (King & Brooks, 2017). Template analysis entails data familiarization, preliminary coding of a subset of data, clustering of codes into meaningful and hierarchically ordered groups, production of an initial template (or codebook) that is applied to additional data and modified iteratively to capture relevant topics, and coding of the full dataset to the final version of the template. The preliminary research question for cross-site analysis is to identify the range, diversity, and prevalence of topics featured in the HCS Photovoice project and how these topics relate to characteristics of the communities and participants (e.g., rural vs. urban, community role related to the opioid epidemic). This preliminary cross-site analytical step generates a comprehensive codebook of the topical contents of the Photovoice dataset to inform HCS-PW members’ development of proposals for scholarly and policy-related publications and presentations.

3. Discussion

HCS is innovative in scale, methods, and goals as a multisite RCT of an intervention to reduce opioid overdose fatality in highly impacted communities. The addition of Photovoice to HCS contributes to these ambitious goals as a tool to provide supplemental community contextual data within the phased CTH approach while supporting its guiding pillars of community engagement, EBP selection and implementation, and/or communications campaigns. The HCS Photovoice initiative is novel because of its focus on one topic (OUD) in multiple communities as part of an RCT. The HCS Photovoice protocol also addresses some common implementation gaps identified in the literature, including engagement of participants at each stage of the Photovoice project, adequate ethical considerations, and participant and audience evaluation of the method’s impacts (Seitz & Orsini, 2022). Participants decide which photo-topics are most relevant to understanding community strengths and concerns in responding to the opioid epidemic. Participants receive interim analyses of discussions to ensure accuracy and engage them in reflective analysis, and, in the case of incomplete information, to seek further details. Participants also contribute to the development of dissemination materials, including photos, captions, and recommendations for action. Finally, interested participants have the opportunity to contribute to analysis for scholarly and policy publication. Adherence to ethical standards is ensured through IRB approval of the protocol, consent, guidance on photography to do no harm, and participants’ self-determination of how they want to be involved in the dissemination of Photovoice projects’ results. Each project concludes with an evaluation of personal experiences of dissemination events and whether the project met the goals of Photovoice (Wang & Burris, 1997a).

The HCS Photovoice protocol has several strengths. One of the biggest strengths of Photovoice in HCS is the expanded methodological toolkit to inform coalition decision-making with the voices and insight of community members most affected by the opioid epidemic. By recruiting PWLE and others deeply involved with addressing OUD, we seek equity of participation by those less likely to be in decision-making roles. The findings and products of these projects will result in contextual, local data that can be consulted when selecting and implementing interventions, promoting EBP uptake and sustained use, and informing community communications materials. The potential for sharing results to guide policy issues spans from local- to state- to national-level application. Another strength is that the common protocol across sites provides for cross-site analysis and development of broader themes. The HCS-PW developed the HCS Photovoice protocol to work within the context of various sites and communities with consistent procedures to allow a common analytic approach. The HCS-PW plans to disseminate cross-site results in the form of manuscripts and conference presentations. We anticipate that this protocol can inform other similar RCTs and large multi-site studies beyond HCS and the topic of the opioid epidemic. The protocol also has accounted for variability in site context and personnel by leaving room for adaptations. For example, the Photovoice protocol incorporates flexibility in implementation to occur at any CTH phase, enables individuals from various HCS roles to be Photovoice facilitators, offers both in-person and virtual session formats, allows incentives based on site parameters and budgets, and provides for modifiable dissemination strategies to meet the goals of individual communities and participants.

This work has several limitations. First, the adaptability of the protocol to the needs of specific communities means that project results will not be generalizable to all communities affected by the opioid epidemic. Community strengths and concerns related to addressing the opioid epidemic identified in interim and cross-site analyses may be specific to individual participants’ perspectives, and these findings may not resonate from community to community given the diversity of communities in the study (i.e., rural/urban) or state-level policies. However, as this is community-based and action-oriented research, our goal is not generalizability but rather the development of a detailed protocol for a Photovoice supplement to the HCS RCT design that could inform the intervention and future OUD research and RCTs. Second, although Photovoice is intended as a tool in the HCS to help contextualize the opioid epidemic locally and inform work in participating communities, there may be ways in which Photovoice has therapeutic or other effects on participants in communities and thus may impact results. However, the potential impact of Photovoice on the HCS intervention is minimal, given the projected small scale of Photovoice project participation (i.e., fewer than 16 individuals per community maximum) relative to community size; additionally, as a community-based study, HCS communities may use other tools to contextualize and inform their work. Also, because stigma reduction was not a main outcome of the CTH, this paper does not contribute to the growing literature on Photovoice as a stigma reduction intervention reviewed in Section 1.2.

Despite these limitations, the addition of Photovoice to the HCS RCT provides an example of how Photovoice integration into RCTs can benefit study goals for community engagement, intervention selection and uptake, and community-sourced communications materials. The protocol also could improve the rigor of future efforts to incorporate Photovoice into RCTs by offering procedural guidance on how three distinct HCS research sites adhere to the three foundational objectives of the Photovoice method, engage participants most affected by the opioid epidemic from Photovoice project start to finish, administer a consistent informed consent process approved by HCS’s consortium-level regulatory agency, and evaluate exhibits of Photovoice products that are sponsored by HCS. This protocol supports the rigorous and participatory use of Photovoice in RCTs and OUD research.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

Photovoice is a creative methodology for understanding stigmatized health conditions

Photovoice can enhance community engagement in randomized controlled trials

Photovoice products include communications materials and data to inform decision

This manuscript provides a Photovoice implementation toolkit

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the HEALing Communities Study Steering Committee for considering and approving use of Photovoice in the study. The implementation of Photovoice benefitted from the contributions from other researchers in the study including Bridget Freisthler, Darcy Freedman, Amy Kuntz, Amy Farmer, Curtis Walker, and the late Rebecca Jackson as well as the HCS Community Engagement Core. The approach benefitted from a pilot led by Merielle Saucier and Nikki Lewis. We are particularly thankful for Photovoice participants who are instrumental to the Photovoice process and contributing to HCS goals.

Funding:

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration through the NIH HEAL (Helping to End Addiction Long-termSM) Initiative under award numbers UM1DA049406, UM1DA049412, UM1DA049417 (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04111939). This study protocol (Pro00038088) was approved by Advarra Inc., the HEALing Communities Study single Institutional Review Board. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration or the NIH HEAL InitiativeSM.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

- Recruitment Script

- Informed Consent

- Photo Consent

- Orientation Slides

- Photovoice Session SEM Table

- Demographic Survey

- Evaluation

References

- Baig AA, Benitez A, Locklin CA, Gao Y, Lee SM, Quinn MT, Solomon MC, Sánchez-Johnsen L, Burnet DL, Chin MH, & Little Village Community Advisory Board. (2015). Picture Good Health: A Church-Based Self-Management Intervention Among Latino Adults with Diabetes. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 30(10), 1481–1490. 10.1007/s11606-015-3339-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balvanz P, Dodgen L, Quinn J, Holloway T, Hudspeth S, & Eng E (2016). From Voice to Choice: African American Youth Examine Childhood Obesity in Rural North Carolina. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 10(2), 293–303. 10.1353/cpr.2016.0036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bylander J (2021). A Mental Health Center Uses Photos To Connect People To Community. Health Affairs, 40(9), 1354–1358. 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabassa LJ, Nicasio A, & Whitley R (2013). Picturing recovery: A photovoice exploration of recovery dimensions among people with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 64(9), 837–842. 10.1176/appi.ps.201200503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson ED, Engebretson J, & Chamberlain RM (2006). Photovoice as a Social Process of Critical Consciousness. Qualitative Health Research, 16(6), 836–852. 10.1177/1049732306287525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2018). Gaining Consensus Among Stakeholders Through the Nominal Group Technique (Brief 7; Evaluation Briefs). https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/evaluation/pdf/brief7.pdf

- Chandler RK, Villani J, Clarke T, McCance-Katz EF, & Volkow ND (2020). Addressing opioid overdose deaths: The vision for the HEALing communities study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 217, 108329. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove D, Bozlak C, & Reid P (2021). Service Barriers for Gender Nonbinary Young Adults: Using Photovoice to Understand Support and Stigma. Affilia, 36(2), 220–239. 10.1177/0886109920944535 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davtyan M, Farmer S, Brown B, Sami M, & Frederick T (2016). Women of Color Reflect on HIV-Related Stigma through PhotoVoice. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 27(4), 404–418. 10.1016/j.jana.2016.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Seranno S, & Colman C (2022). Capturing recovery capital: Using photovoice to unravel recovery and desistance. Addiction Research & Theory, 30(4), 237–245. 10.1080/16066359.2021.2003787 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drainoni M-L, Childs E, Biello KB, Biancarelli DL, Edeza A, Salhaney P, Mimiaga MJ, & Bazzi AR (2019). “We don’t get much of a voice about anything”: Perspectives on photovoice among people who inject drugs. Harm Reduction Journal, 16(1), 61. 10.1186/s12954-019-0334-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan EH, Buck T, Gamble A, Hunter C, Sewell I, & Davidson L (2016). “Recovery Speaks”: A Photovoice Intervention to Reduce Stigma Among Primary Care Providers. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 67(5), 566–569. 10.1176/appi.ps.201500049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden SD, McLeroy KR, Green LW, Earp JAL, & Lieberman LD (2015). Upending the Social Ecological Model to Guide Health Promotion Efforts Toward Policy and Environmental Change. Health Education & Behavior, 42(1_suppl), 8S–14S. 10.1177/1090198115575098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King N, & Brooks JM (2017). Template Analysis for Business and Management Students. SAGE Publications Ltd. 10.4135/9781473983304 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kohrt BA, Jordans MJD, Turner EL, Sikkema KJ, Luitel NP, Rai S, Singla DR, Lamichhane J, Lund C, & Patel V (2018). Reducing stigma among healthcare providers to improve mental health services (RESHAPE): Protocol for a pilot cluster randomized controlled trial of a stigma reduction intervention for training primary healthcare workers in Nepal. Pilot and Feasibility Studies, 4(1), 36. 10.1186/s40814-018-0234-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BC, Bendixsen C, Liebman AK, & Gallagher SS (2017). Using the socio-ecological model to frame agricultural safety and health interventions. Journal of Agromedicine, 1059924X.2017.1356780. 10.1080/1059924X.2017.1356780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre RC, Chandler RK, Helme DW, Kerner R, Mann S, Stein MD, Reynolds J, Slater MD, Anakaraonye AR, Beard D, Burrus O, Frkovich J, Hedrick H, Lewis N, & Rodgers E (2020). Health communication campaigns to drive demand for evidence-based practices and reduce stigma in the HEALing communities study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 217, 108338. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebenberg L (2022). Photovoice and Being Intentional About Empowerment. Health Promotion Practice, 23(2), 267–273. 10.1177/15248399211062902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln YS, & Guba EG (1986). But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New Directions for Program Evaluation, 1986(30), 73–84. 10.1002/ev.1427 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez LS, Chassler D, Cortes MA, Baum M, Guzman-Betancourt G, Reyes D, Lopez LM, Roberts M, De Jesus D, Stewart E, & Muroff J (2020). Visual Ethnography: Decriminalization and Stable Housing Equals Motivation, Stability, and Recovery Among Latinx Populations. American Journal of Public Health, 110(6), 840–841. 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews C (2014). Critical pedagogy in health education. Health Education Journal, 73(5), 600–609. 10.1177/0017896913510511 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson CL, Tanz LJ, Quinn K, Kariisa M, Patel P, & Davis NL (2021). Trends and Geographic Patterns in Drug and Synthetic Opioid Overdose Deaths—United States, 2013–2019. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 70(6), 202–207. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7006a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, & Glanz K (1988). An Ecological Perspective on Health Promotion Programs. Health Education Quarterly, 15(4), 351–377. 10.1177/109019818801500401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizock L, Russinova Z, & Shani R (2014). New Roads Paved on Losses: Photovoice Perspectives About Recovery From Mental Illness. Qualitative Health Research, 24(11), 1481–1491. 10.1177/1049732314548686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore SJ, Wood-Palmer DK, Jones MD, Doraivelu K, Newman A Jr, Harper GW, Camacho-González A, del Río C, Sutton MY, & Hussen SA (2022). Feasibility and acceptability of B6: A social capital program for young Black gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men living with HIV. Health Education Research, 37(6), 405–419. 10.1093/her/cyac028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muroff J, Do D, Brinkerhoff CA, Chassler D, Cortes MA, Baum M, Guzman-Betancourt G, Reyes D, López LM, Roberts M, De Jesus D, Stewart E, & Martinez LS (2023). Nuestra Recuperación [Our Recovery]: Using photovoice to understand the factors that influence recovery in Latinx populations. BMC Public Health, 23(1), 81. 10.1186/s12889-023-14983-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintiliani LM, Russinova ZL, Bloch PP, Truong V, Xuan Z, Pbert L, & Lasser KE (2015). Patient navigation and financial incentives to promote smoking cessation in an underserved primary care population: A randomized controlled trial protocol. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 45, 449–457. 10.1016/j.cct.2015.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosas LG, Thiyagarajan S, Goldstein BA, Drieling RL, Romero PP, Ma J, Yank V, & Stafford RS (2015). The Effectiveness of Two Community-Based Weight Loss Strategies among Obese, Low-Income US Latinos. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 115(4), 537–550.e2. 10.1016/j.jand.2014.10.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russinova Z, Gidugu V, Bloch P, Restrepo-Toro M, & Rogers ES (2018). Empowering individuals with psychiatric disabilities to work: Results of a randomized trial. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 41(3), 196–207. 10.1037/prj0000303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russinova Z, Mizock L, & Bloch P (2018). Photovoice as a tool to understand the experience of stigma among individuals with serious mental illnesses. Stigma and Health, 3, 171–185. 10.1037/sah0000080 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Russinova Z, Rogers ES, Gagne C, Bloch P, Drake KM, & Mueser KT (2014). A randomized controlled trial of a peer-run antistigma photovoice intervention. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 65(2), 242–246. 10.1176/appi.ps.201200572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis Owen, & Fisher. (2015). Ecological Models of Health Behavior. In Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice (4th ed., pp. 465–482). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Seitz CM, & Orsini MM (2022). Thirty Years of Implementing the Photovoice Method: Insights From a Review of Reviews. Health Promotion Practice, 23(2), 281–288. 10.1177/15248399211053878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessford JD, Chan K, Kaiser A, Singh H, Munce S, Alavinia M, & Musselman KE (2022). Protocol for a single group, mixed methods study investigating the efficacy of photovoice to improve self-efficacy related to balance and falls for spinal cord injury. BMJ Open, 12(12), e065684. 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-065684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer R (1985). Beyond the Dispensary. Amref. [Google Scholar]

- Singh H, Scovil CY, Bostick G, Kaiser A, Craven BC, Jaglal SB, & Musselman KE (2020). Perspectives of wheelchair users with spinal cord injury on fall circumstances and fall prevention: A mixed methods approach using photovoice. PLOS ONE, 15(8), e0238116. 10.1371/journal.pone.0238116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith E, Carter M, Walklet E, & Hazell P (2022). Investigating recovery from problem substance use using digital photovoice. Journal of Community Psychology, jcop.22957. 10.1002/jcop.22957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith E, Carter M, Walklet E, & Hazell P (2024). Exploring the Methodological Benefits and Challenges of Utilising a Photovoice Methodology With Individuals in Recovery From Problem Substance Use. Qualitative Health Research, 10497323231217600. 10.1177/10497323231217601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprague Martinez L, Rapkin BD, Young A, Freisthler B, Glasgow L, Hunt T, Salsberry PJ, Oga EA, Bennet-Fallin A, Plouck TJ, Drainoni M-L, Freeman PR, Surratt H, Gulley J, Hamilton GA, Bowman P, Roeber CA, El-Bassel N, & Battaglia T (2020). Community engagement to implement evidence-based practices in the HEALing communities study. Drug and Alcohol ependence, 217, 108326. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprague Martinez L, Walter AW, Acevedo A, López LM, & Lundgren L (2018). Context Matters: Health Disparities in Substance Use Disorders and Treatment. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 18(1), 84–98. 10.1080/1533256X.2017.1412979 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strack RW, Magill C, & McDonagh K (2004). Engaging Youth through Photovoice. Health Promotion Practice, 5(1), 49–58. 10.1177/1524839903258015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strack RW, Orsini MM, & Ewald DR (2022). Revisiting the Roots and Aims of Photovoice. Health Promotion Practice, 23(2), 221–229. 10.1177/15248399211061710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suprapto N, Sunarti T, Suliyanah S, Wulandari D, Hidayaatullaah HN, Adam AS, & Mubarok H (2020). A systematic review of photovoice as participatory action research strategies. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education (IJERE), 9(3), 675. 10.11591/ijere.v9i3.20581 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teti M, & Myroniuk T (2022). Image to Action: Past Success, Ongoing Questions, and New Horizons for Photovoice Exhibits. Health Promotion Practice, 23(2), 262–266. 10.1177/15248399211054774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tippin GK, & Maranzan KA (2022). Photovoice as a Method to Reduce the Stigma of Mental Illness Among Health Care Students. Health Promotion Practice, 23(2), 331–337. 10.1177/15248399211057152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Steenberghe T, Vanderplasschen W, Bellaert L, & De Maeyer J (2021). Photovoicing interconnected sources of recovery capital of women with a drug use history. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 28(5), 411–425. 10.1080/09687637.2021.1931033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh SL, El-Bassel N, Jackson RD, Samet JH, Aggarwal M, Aldridge AP, Baker T, Barbosa C, Barocas JA, Battaglia TA, Beers D, Bernson D, Bowers-Sword R, Bridden C, Brown JL, Bush HM, Bush JL, Button A, Campbell ANC, … Chandler RK (2020). The HEALing (Helping to End Addiction Long-term SM) Communities Study: Protocol for a cluster randomized trial at the community level to reduce opioid overdose deaths through implementation of an integrated set of evidence-based practices. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 217, 108335. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, & Burris MA (1997a). Photovoice: Concept, Methodology, and Use for Participatory Needs Assessment. Health Education & Behavior, 24(3), 369–387. 10.1177/109019819702400309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, & Burris MA (1997b). Photovoice: Concept, Methodology, and Use for Participatory Needs Assessment. Health Education & Behavior, 24(3), 369–387. 10.1177/109019819702400309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winhusen T, Walley A, Fanucchi LC, Hunt T, Lyons M, Lofwall M, Brown JL, Freeman PR, Nunes E, Beers D, Saitz R, Stambaugh L, Oga EA, Herron N, Baker T, Cook CD, Roberts MF, Alford DP, Starrels JL, & Chandler RK (2020). The Opioid-overdose Reduction Continuum of Care Approach (ORCCA): Evidence-based practices in the HEALing Communities Study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 217, 108325. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu E, Villani J, Davis A, Fareed N, Harris DR, Huerta TR, LaRochelle MR, Miller CC, & Oga EA (2020). Community dashboards to support data-informed decision-making in the HEALing communities study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 217, 108331. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang LH, Wong LY, Grivel MM, & Hasin DS (2017). Stigma and substance use disorders: An international phenomenon. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 30(5), 378–388. 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AM, Brown JL, Hunt T, Sprague Martinez LS, Chandler R, Oga E, Winhusen TJ, Baker T, Battaglia T, Bowers-Sword R, Button A, Fallin-Bennett A, Fanucchi L, Freeman P, Glasgow LM, Gulley J, Kendell C, Lofwall M, Lyons MS, … Walsh SL (2022). Protocol for community-driven selection of strategies to implement evidence-based practices to reduce opioid overdoses in the HEALing Communities Study: A trial to evaluate a community-engaged intervention in Kentucky, Massachusetts, New York and Ohio. BMJ Open, 12(9), e059328. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-059328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.