Abstract

Concussion is a widely recognized environmental risk factor for neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson’s disease (PD). Small-vessel disease of the brain has been reported to contribute to neurodegenerative diseases. In this study, we observed BBB disruption in wild-type (WT) mice, but not in matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) knockout mice, subjected to single severe traumatic brain injury (ssTBI). Furthermore, treating ssTBI mice with the MMP-9 inhibitor GM6001 effectively maintained BBB integrity, promoted the elimination of damaged mitochondria via mitophagy, and then prevented neuronal death and progressive neurodegeneration. However, we did not observe this neuroprotective effect of MMP-9 inhibition in beclin-1−/+ mice. Collectively, these findings revealed that concussion led to BBB disruption via MMP-9, and that GM6001 prevented the development of PD via the autophagy pathway.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10571-020-00933-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Traumatic brain injury, Blood–brain barrier, MMP-9, Mitophagy, Parkinson’s disease

Introduction

A number of studies have identified concussion as an important environmental risk factor for the development of chronic traumatic encephalopathy, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), Parkinson's disease (PD), Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and various neuropsychiatric problems many years after injury (Barrio et al. 2015; Chen et al. 2017; Gardner and Yaffe, 2015). However, the exact mechanistic link between single severe brain injury (ssTBI) and neurodegenerative diseases remains enigmatic, and no effective treatment is available to prevent this pathology (Kondo et al. 2015).

The blood–brain barrier (BBB) limits transport of blood-derived molecules that are crucial for normal neuronal function and information processing—such as glucose and amino acids, pathogens, and cells—into the brain. BBB breakdown is well known as an early biomarker of brain dysfunction (Nation et al. 2019). Contusion could up-regulate matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9), which disrupts the BBB (Seo et al. 2013; Shlosberg et al. 2010). But whether concussion could also cause BBB disruption is still unknown. This prompted us to investigate whether BBB breakdown due to MMP-9 could contribute to post-traumatic neurodegenerative diseases and the specific molecular mechanism by which this happens (Choi et al. 2016).

PD, often considered a proteinopathy, is characterized by the accumulation of misfolded proteins and damaged organelles into large insoluble aggregates. Mitophagy plays an essential role in mitochondrial quality control via fusion and fission dynamics that eliminate dysfunctional and damaged organelles. Accumulating evidence supports the notion that mitophagy does not function sufficiently in PD (Lahiri and Klionsky 2017; Matheoud et al. 2016; Xiong et al. 2009). However, since little is detectable acutely or subacutely after concussive brain injury, whether deficiency or inhibition of mitophagy is a cause or consequence of post-traumatic neurodegeneration is still unknown.

Here, our data demonstrated that concussion led to BBB disruption via MMP-9. Furthermore, genetic or pharmacological inhibition of MMP-9 promoted the elimination of damaged mitochondria via mitophagy, and then reduced functional deficits after head injury in mice.

Materials and Methods

Mice

All wild-type (WT) mice were obtained from the animal center of Nanjing Medical University. In this study, all transgenic mice were in C57BL/6J background. GFP-LC3 transgenic mice were purchased from CasGene Biotech. Co., Ltd. MMP-9−/− and beclin-1−/+ mice were obtained from Jackson laboratory.

This study used 12-week-old C57BL/6 WT mice, both male and female, weighing 20–25 g. Standard laboratory animal feed was provided by Nanjing Medical University. Mice were maintained in a pathogen-free environment and housed with a 12:12-h light/dark cycle under an ambient temperature of 22 ± 2° C.

Traumatic Brain Injury

Mice received a closed head injury simulating concussive brain injury as previously described (Kondo et al. 2015; Zhu et al. 2014). Mice were randomized to undergo either ssTBI or sham injury. Briefly, we anesthetized the mice for 45 s with 4% isoflurane in a 70:30 mixture of N2O:O2. Mice were grasped by the tail and placed on a Kimwipe (Kimberly-Clark Corp., Irvine, TX, USA) under a hollow guide tube. A metal bolt (80 g, 60-inch height) was applied to deliver an impact on the dorsal aspect of the skull through the Kimwipe, resulting in a rotational downward injury to the anterior–posterior plane. Mice in the sham group were anesthetized without head injury.

Evans Blue (EB) Permeability Assay

We performed staining with the perivascular marker isolectin B4 (Ib4, catalog no. L2140; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) and intravascular EB (catalog no. E2129; Sigma-Aldrich) as previously described in standard procedures (Walchli et al. 2015; Menard et al. 2017). After anesthesia, mice were administered 2% (w/v) EB dissolved in saline (6 µL/g of body weight) by retro-orbital injection. After 16 h of circulation followed by 10 min of perfusion, the brain was fixed in 10 mL of freshly prepared cold 4% formaldehyde (FA) + 0.05% glutaraldehyde (GA) and then cut into 40-µm coronal sections on a cryostat for free-floating processing. We incubated the slices for 72 h at 4 °C with biotinylated Ib4 diluted 1:50 in CaCl2-containing buffer, then for 24 h with streptavidin–cyanine 3 (Cy3; 1:500; catalog no. S6402; Sigma-Aldrich) secondary antibody in CaCl2-containing buffer. Sections were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; catalog no. P36931; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) to visualize nuclei. Finally, we acquired images on an LSM-780 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany) and analyzed them using Image J software (National Institutes of Health [NIH], Bethesda, MD, USA).

Quantification of EB extravasation was reported previously. After homogenization with dimethylformamide, the samples were centrifuged for 30 min at 21,000×g. Then, we assessed EB fluorescence in the supernatant using a microplate reader and SoftMax Pro software version 5.2 (Molecular Devices, San José, CA, USA) according to the following formula:

Drug Treatment

We obtained GM6001 and BB-94 (catalog nos. CC1010 and S7155, respectively) from Millipore (Burlington, MA, USA). They were the broad-spectrum MMP inhibitors. Negative control was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (catalog no. 364210). Mice subjected to ssTBI were randomly divided into groups treated with GM6001 or vehicle. Mice in the ssTBI + GM6001 group received 50 mg/kg GM6001 intraperitoneally (i.p.) as pretreatment 3 days prior to injury, as post-injury treatment daily for 2 weeks, and then weekly for 6 m. Mice in the sham group received the same doses of vehicle at the same time points.

Immunoblot Analysis

We homogenized brain tissues in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer. For Western blot of α-syn, we lysed mouse brains using lysis buffer containing 1% Triton X-100 (TX-100; Sigma-Aldrich); the pellets were then resuspended via sonication. We separated proteins using sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and then transferred them to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. After blocking them with 5% milk in tris-buffered saline + Polysorbate 20 (TBST) for 2 h at room temperature (RT), we incubated the membranes with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C, followed by incubation with secondary antibodies for 1 h.

The follow primary antibodies were used: TOM40 (1:100; Abcam, catalog no. ab51884), COXIV (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, catalog no. 11967), MnSOD (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, catalog no. 13141), β-actin (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, catalog no. 3700), claudin-5 (1:1000; Abcam, catalog no. ab15106), ZO-1 (1:1000; novus, catalog no. NBP1-85046), occluding (1:1000; novus, catalog no. NBP1-87402). α-syn (1:1000; novus, catalog no. NBP1-26380), p-α-syn (1:1000; novus, catalog no. NBP2-61121), TH (1:1000; Abcam, catalog no. ab112), MMP-9 (1:1000; novus, catalog no. NBP-2-22181), NeuN (1:1000; Abcam, catalog no. ab104224).

Immunostaining Analysis

In brief, we embedded frozen coronal sections (10 μm thick) onto the slides and incubated them with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Then, we used biotin-conjugated secondary antibodies to enhance signals for 1 h at RT. Labeled sections were observed and captured using the Zeiss confocal microscope or a Nikon fluorescent microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Fluorescent images were captured by microscopy under exactly the same conditions. We analyzed and quantified immunostained images using Image J software.

The follow primary antibodies were used: TOM40 (1:200; Abcam, catalog no. ab51884), ZO-1 (1:200; novus, catalog no. NBP1-85046), α-syn (1:200; novous, catalog no.NBP1-26380), p-α-syn (ser129) (1:200; novus, catalog no. NBP2-61121), TH (1:500; Abcam, catalog no.ab112), NeuN (1:500; Abcam, catalog no. ab104224), CD31 (1:200; novus, catalog no. NB100-64796).

Determination of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

We determined ROS in brain tissues using dihydroethidium (DHE; catalog no. D11347; Thermo Fisher) staining. Briefly, we obtained 20-μm–thick cryosections of frozen brain tissues. The samples were incubated with 10 μM DHE at 37 °C for 30 min in a humidified, dark chamber and then counterstained with DAPI. Fluorescent images were obtained using the Zeiss confocal microscope and determined with Image J software.

Transmission Electronic Microscopy (TEM)

For ultrastructure examination, mice were euthanized and then perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde. After sacrifice, we removed mouse brains and fixed them with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 2 h at RT. The target samples were postfixed with 1% osmium tetroxide for 1 h at 4 °C, dehydrated with an ethanol gradient, and then embedded in epoxy resin. Finally, we used a TEM (Quanta 10; FEI Co., Hillsboro, Oregon, US) to observe the ultrastructure of the selected samples. Multiple fields from one slice were selected to get an average at random and imaged for further analysis.

Behavioral Measurements

We assessed motor coordination and learning using an accelerating RotaRod (TSE Systems GmbH, Bad Homburg, Germany). Length of time before fall was recorded and analyzed using GraphPad Prism Software version 6.04 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, California, US). For the wire suspension performance test, mice were grasped by the tail and placed on a wire suspended between 2 upright bars. Because mice were held up to the wire, they could grip it with both front paws. We recorded the length of time for which mice could remain on the wire. Heat and cold tail pain sensitivity was evaluated by tail flick latency time after exposure.

The same experimenter used a Morris water maze (MWM) to evaluate spatial learning and memory in the mice at approximately the same time each day between 08:00 h and 11:00 h. The water temperature was maintained at 24 °C. For each trial, mice were placed in the pool facing the wall at a random start location (north, south, east, or west). If mice failed to reach the platform within the set time, they were picked up, placed on the platform, and allowed to remain there for 15 s. For probe trials, mice were placed in the tank opposite the target quadrant. Reference memory was determined by number of entries for 60 s when the platform was absent. This trial was done on test days 1–5. On test day 5, a probe trial was done 2 h after the fifth hidden platform trial. Both visible platform trials were performed on test day 6 or 7. When mice were subjected to repeat MWM testing, we moved the platform to a different quadrant than that used previously. Latencies for finding the platform and number of entries were analyzed with a tracking device and software (Chronotrack version 3.0, San Diego Instruments, San Diego, California, US).

Statistical Analysis

All mice were randomly assigned to different groups; no animals were excluded in this study. We predetermined sample sizes for overall power of α = 0.05 and β = 0.8, based on existing data. Data are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Single comparisons were assessed by unpaired t test. We evaluated multiple comparisons using Tukey’s test after 1-way or 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using GraphPad Prism. Significant difference was defined as P < 0.05.

Results

Concussion Caused BBB Breakdown via MMP-9

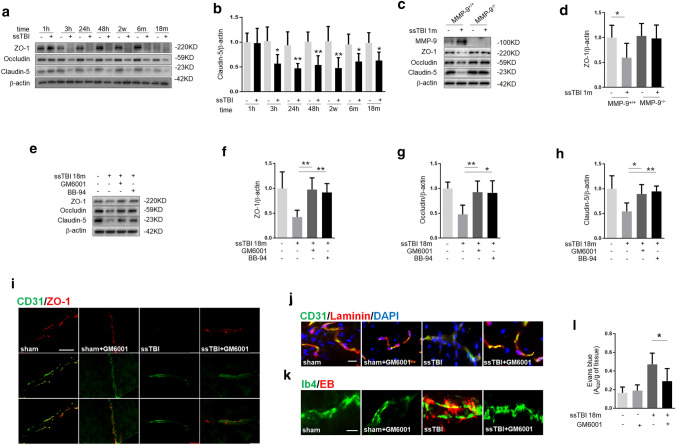

While BBB breakdown has been reported in the brain after experimental and clinical contusion, BBB and its role in concussion merit additional exploration (Charkviani et al. 2019). We observed BBB disruption in ssTBI mice, as evidenced by the decrease in tight-junction proteins (TJPs) claudin-5, occludin, and zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) (Fig. 1a, b). It is well known that MMP-9 mediates BBB permeability after brain injury (Choi et al. 2016; Seo et al. 2013). To understand the role of MMP-9 in our model, we subjected MMP-9+/+ or MMP-9−/− mice to ssTBI and then evaluated BBB integrity. We found that ssTBI resulted in significantly lower levels of claudin-5, occludin, and ZO-1 in the brain at 1 m in MMP-9+/+ mice, but not in MMP-9−/− mice, suggesting that ssTBI induced BBB disruption via MMP-9 (Fig. 1c, d; *P < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Concussion caused BBB damage via MMP-9. a Western blot analysis of the tight-junction proteins ZO-1, occludin and claudin-5 in the cortex of wild-type mice. β-actin was used as the loading control. b Densitometry of claudin-5. n = 5/group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus sham. c Western blot analysis of MMP-9, ZO-1, occludin and claudin-5 in the cortex of MMP-9+/+ or MMP-9−/− mice at 1 m after ssTBI. β-actin was used as a loading control. d Densitometry of ZO-1. n = 5/group.*P < 0.05. e Western blot showed that ssTBI-induced decreases of ZO-1, occludin and claudin-5 were partially reversed by GM6001 or BB-94. Protein was obtained from the cortex at 18 m after ssTBI. β-actin was used as a loading control. n = 5/group. **P < 0.01. f Densitometry of ZO-1. n = 5/group. **P < 0.01. g Densitometry of occludin. n = 5/group. **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05. h Densitometry of claudin-5. n = 5/group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. i Representative fluorescence images depicting CD31 (green) with ZO-1 (red).Scale bar, 100 µm. Samples were obtained at 18 m after ssTBI. j Representative fluorescence images depicting CD31 (green) with laminin (red). Scale bar, 50 µm. k and l Assessment of BBB permeability with Evans blue (EB) dyes revealed significant BBB leakiness after ssTBI. Notably, GM6001 reduced ssTBI-induced EB extravasation. Samples were obtained at 18 m after ssTBI. Scale bar, 50 µm. n = 8/group. *P < 0.05

Next, we treated mice subjected to ssTBI with either a MMP-9 inhibitor or vehicle for 6 m and then assessed BBB 18 m after injury. First, we found that the level of MMP-9 markedly increased after ssTBI (supplemental Fig. 1a, b; **P < 0.01). Furthermore, Western blot analyses revealed that TJP levels were higher in mice treated with MMP-9 inhibitors than in vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 1e–h; **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05). Then, we double-stained ZO-1/Cluster of Differentiation 31 (CD31) or laminin/CD31 to detect the function of MMP-9. The results confirmed that BBB integrity was disrupted by ssTBI, but the MMP-9 inhibitor alleviated this effect (Fig. 1i, j). We also detected infiltration of EB into the cortex of ssTBI mice via far-red autofluorescent proteins and a microplate reader. As expected, GM6001 treatment significantly decreased EB leakage induced by ssTBI (Fig. 1k, l; *P < 0.05). Taken together, these data showed that MMP-9 inhibition could effectively reduce ssTBI-induced BBB damage.

GM6001 Treatment Attenuated Mitochondrial Dysfunction After ssTBI

Increased BBB permeability initiates pathological changes in the neurovascular network and contributes to contusion-induced brain functional decline (Nation et al. 2019). Therefore, we reasoned that BBB disruption was involved in the development of ssTBI-induced PD. Abnormal mitochondria play a key role in the pathogenesis of PD; therefore, we examined the relationship between BBB integrity and mitochondrial function after ssTBI. We sought to learn whether GM6001 treatment could promote clearance of damaged mitochondria via mitophagy in our ssTBI mouse model. Under the TEM, we observed increased amounts of autophagic vacuoles containing damaged mitochondria in GM6001-treated ssTBI mice versus those treated with vehicle, suggesting that MMP-9 contributed to ssTBI-induced mitochondrial dyshomeostasis (Fig. 2a, b; *P < 0.05). Furthermore, western blot analysis showed decreased lipidated microtubule-associated protein light chain 3–phosphatidylethanolamine conjugate (LC3-II) and increased p62 (sequestosome-1 [SQSMT1]) in ssTBI versus control brain tissue, suggesting inhibition of autophagy (Fig. 2c, d; **P < 0.01). Mitochondrial marker protein content from inner (IMM) (COXIV) and outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) (TOM40) and matrix (MnSOD) subcompartments were significantly increased in ssTBI versus control brain tissue in a manner consistent with decreased overall autophagy (Fig. 2c, e; **P < 0.01). Interestingly, these effects were partially reversed by GM6001 treatment (Fig. 2c–e; d, **P < 0.01 and e, ***P < 0.001). In comparison to the ssTBI + vehicle group, GM6001 treatment elicited significant increases in the expression of LC3-II (Fig. 2f, j; *P < 0.05) and co-localization of green fluorescent protein (GFP)–LC3 puncta with mitochondria (Fig. 2f, h; **P < 0.01), indicating preferential increases in autophagosomes and mitophagosomes. Taken together, these data showed that GM6001 could significantly reverse ssTBI-induced inhibition of autophagy and mitophagy.

Fig. 2.

GM6001 treatment attenuated mitochondrial dysfunction after ssTBI. a and b Representative electron-micrograph images of the cortex showing damaged mitochondrion within autophagosome-like structures, such as a double membrane (yellow arrow). Scale bar, 1 µm. c Western blot of autophagic and mitochondrial markers. β-actin was used as a loading control. d Densitometry of LC3-II. n = 5/group. **P < 0.01. e Densitometry of TOM40. n = 5/group. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. f Representative fluorescence images of the co-localization of GFP-LC3 and mitochondrial marker (COXIV, red). Scale bar, 20 µm. g Quantification of GFP-LC3 puncta. n = 8/group. *P < 0.05. h Quantification of the co-localization of GFP-LC3 and mitochondrial marker (Tom40, red). n = 8/group. **P < 0.01. i Representative images of dihydroethidium staining on cortex (i, up) and hippocampus (i, down). Scale bar, 100 µm. j and k Quantifications of dihydroethidium fluorescence intensity on cortex (j) and hippocampus (k), respectively. n = 8/group. *P < 0.05

Given the ability of GM6001 to restore mitophagy, we then wondered whether GM6001 treatment could prevent ssTBI-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and ROS release. We determined ROS levels in the cortex or hippocampus after ssTBI via DHE staining, which is commonly used to detect ROS production. As expected, we observed increased DHE signal in the cortex and hippocampus after ssTBI, which was significantly attenuated by treatment with GM6001 (Fig. 2i–k; *P < 0.05). Taken together, these data showed that GM6001 treatment could effectively promote the clearance of damaged mitochondria via mitophagy to ameliorate mitochondrial dysfunction and reduce ROS production after ssTBI.

GM6001 Treatment Effectively Blocked Lewy Bodies Accumulation After ssTBI

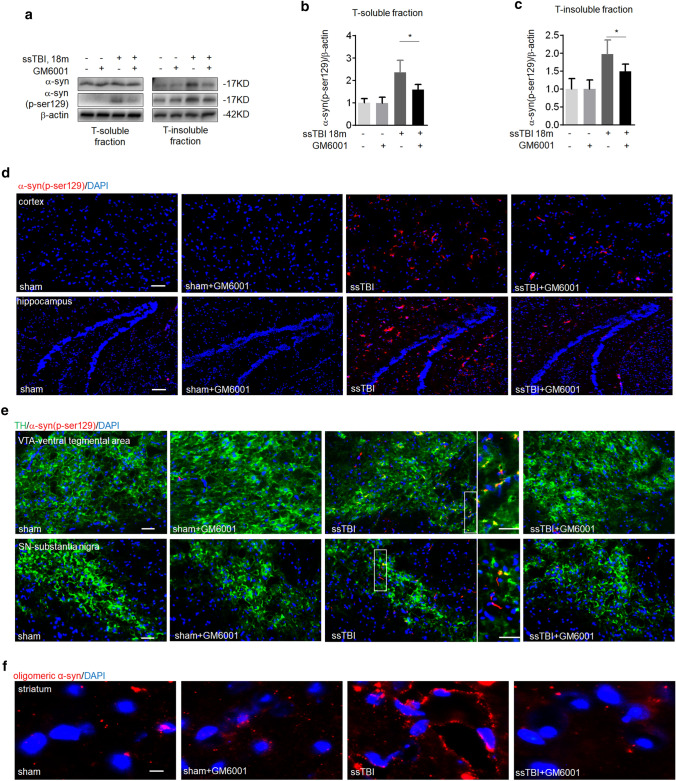

α-Synuclein (α-syn) accumulation is central to the pathogenesis of PD; α-syn is a major component of abnormal neuronal aggregations known as Lewy bodies (LBs) (Spillantini et al. 1997). We homogenized mouse brain samples in TX-100 buffer and resuspended the pellet via sonication. The ssTBI mice had markedly increased α-syn levels in insoluble fractions (Fig. 3a). These levels significantly decreased with GM6001 treatment, but the soluble-α-syn fraction did not change (Fig. 3a). In support, we found more phosphorylated (pSer129) α-syn in ssTBI mice not treated with GM6001 (Fig. 3a–c; *P < 0.05). Similarly, the result showed more pSer129 α-syn in the cortices (Fig. 3d, up) and hippocampi (Fig. 3d, down) of ssTBI mice treated with vehicle than in mice treated with GM6001. Consistently, we found large pathogenic aggregates of pSer129 α-syn in tyrosine hydroxylase–positive (TH+) dopaminergic neurons of the ventral mesencephalon in vehicle-treated ssTBI mice than in GM6001-treated mice (Fig. 3e). In addition, accumulation of oligomeric α-syn was observed on striatum after ssTBI (Fig. 3f). Taken together, these data showed that GM6001 treatment could reduce the accumulation of neurotoxic proteins after ssTBI.

Fig. 3.

GM6001 treatment prevented Lewy bodies accumulation after ssTBI. a Western blot of a-syn and p-ser129 α-syn in soluble (a, left) and insoluble (a, right) basal ganglia fractions (TX-100 soluble and insoluble). β-actin was used as a loading control. b Densitometry of p-ser129 α-syn in T-soluble fractions. n = 5/group. *P < 0.05. c Densitometry of p-ser129 α-syn in T-insoluble fractions. n = 5/group. *P < 0.05. d Representative fluorescence images of p-ser129 α-syn (red) and DAPI (blue) staining on cortex (d, up) and hippocampus (d, down). Scale bar, 100 µm. e Representative fluorescence micrographs illustrating TH (green), p-ser129 α-syn (red) and DAPI (blue) staining on ventral tegmental area (e, up) and substantia nigra (e, down). Scale bar, 100 µm. f Representative fluorescence images of oligomeric α-syn (red) and DAPI (blue) staining on striatum. Scale bar, 500 µm

GM6001 Treatment Effectively Prevented Neuronal Death After ssTBI

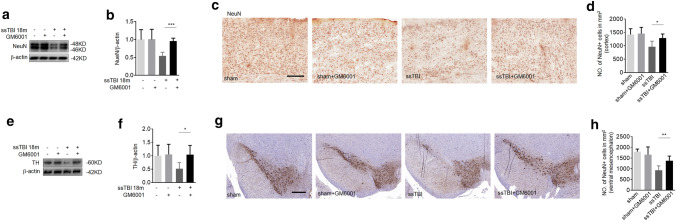

To gain further insight into the role of MMP-9 in the development of PD, we next examined whether ssTBI-caused neuronal death could be reduced by GM6001. First, we found that the level of TH on striatum did not decreased at 18 m after ssTBI versus control in MMP-9−/− mice (supplemental Fig. 2a, b). Western blot analysis showed that GM6001 treatment markedly increased the expression of NeuN in the cortex after ssTBI, compared with vehicle treatment (Fig. 4a, b; ***P < 0.001). Similarly, the number of NeuN-positive cells in the cortex decreased by 20%, which was significantly rescued by GM6001 treatment (Fig. 4c, d; *P < 0.05), indicating the inhibitory activity of GM6001 on ssTBI-induced neuronal death. PD is also characterized by loss of dopaminergic neurons. To study this protective role of GM6001, we assessed dopaminergic neurons after treatment. GM6001 treatment remarkably reduced dopaminergic neuron damage in the striatum (Fig. 4e, f; *P < 0.05) and the ventral mesencephalon (Fig. 4g, h; **P < 0.01), suggesting that MMP-9 contributed to the ssTBI-induced loss of dopaminergic neurons. Taken together, these results suggested that GM6001 treatment could reduce ssTBI-induced neuronal death, including death of dopaminergic neurons.

Fig. 4.

GM6001 treatment prevented neuronal death after ssTBI. a Western blot of NeuN in cortex. β-actin was used as a loading control. b Densitometry of NeuN. n = 5/group. ***P < 0.001. (c and d) Immunohistochemistry (c) and quantification (d) of NeuN staining on the cortex. Scale bar, 100 µm. n = 8/group. *P < 0.05. e Western blot of TH expression in the striatum. β-actin was used as a loading control. f Densitometry of TH. n = 5/goup. *P < 0.05. (g and h) Immunohistochemistry (g) and quantification (h) of TH expression on the ventral mesencephalon. Scale bar, 50 µm. n = 8/group. **P < 0.01

Autophagy was Required for the Neuroprotective Effect of GM6001

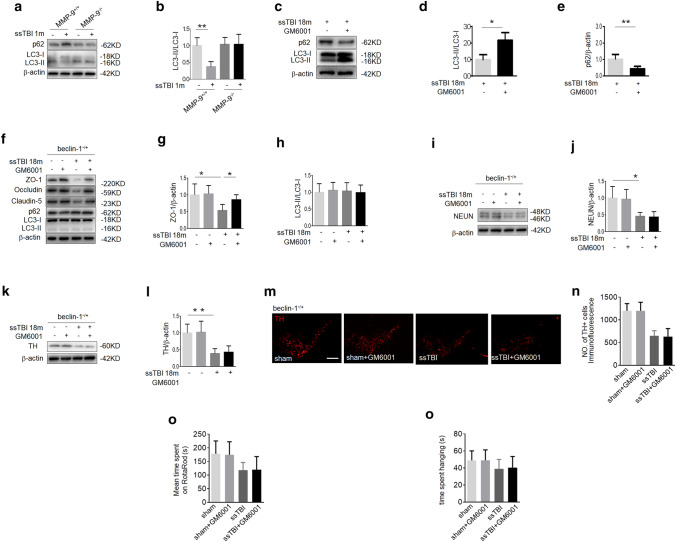

Next, we investigated the specific mechanisms underlying the inhibitory effect of GM6001 on the development of ssTBI-induced PD. The autophagy pathway is responsible for the degradation of misfolded proteins and damaged organelles, which can contribute to neurodegenerative diseases, including PD (Matheoud et al. 2016). We observed a decrease in LC3-II/LC3-I and an increase in p62 at 1 m after ssTBI versus control in MMP-9+/+ mice, suggesting that autophagy was inactivated (Fig. 5a, b; **P < 0.01). However, we did not detect this change at 1 m after ssTBI in MMP-9−/− mice (Fig. 5a, b). As expected, GM6001 treatment significantly reversed ssTBI-induced inhibition of autophagy (Fig. 5c–e; d, *P < 0.05 and e, **P < 0.01). Taken together, these data demonstrated that autophagy was inhibited after ssTBI and that MMP-9 was required for this process.

Fig. 5.

GM6001 treatment prevented ssTBI-induced neurodegeneration via autophagy. a Western blot of LC3 and p62 in the cortex of MMP-9+/+ or MMP-9−/− mice between sham and ssTBI at 1 m after head injury. β-actin was used as a loading control. b Densitometry of LC3-II. n = 5/group. **P < 0.01. c Western blot of LC3 and p62 in the cortex of MMP-9+/+ mice at 18 m after ssTBI. β-actin was used as a loading control. d Densitometry of LC3-II in the cortex of MMP-9+/+ mice. n = 5/group. *P < 0.05. e Densitometry of p62 in the cortex of MMP-9+/+ mice. n = 5/group. **P < 0.01. f Western blot of ZO-1, occludin, claudin-5, LC3 and p62 in the cortex of beclin-1−/+ mice at 18 m after ssTBI. β-actin was used as a loading control. g Densitometry of ZO-1 in the cortex of beclin-1−/+ mice. n = 5/group. *P < 0.05. h Densitometry of LC3-II in the cortex of beclin-1−/+ mice. n = 5/group. i Western blot of NeuN in the cortex of beclin-1−/+ mice at 18 m after ssTBI. β-actin was used as a loading control. j Densitometry of NeuN. n = 5/group. *P < 0.05. k Western blot of TH in the striatum of beclin-1−/+ mice at 18 m after ssTBI. β-actin was used as a loading control. l Densitometry of TH. n = 5/group, **P < 0.01. (m and n) Representative fluorescence images (m) and quantification (n) of TH expression on the ventral mesencephalon of beclin-1−/+ mice at 18 m after ssTBI. Scale bar, 200 µm. n = 8/group. (o) Motor coordination by RotaRod. n = 15/group. (p) Wire suspension performance. n = 15/group

Given the relationship between autophagy and MMP-9, we next examined the effects of GM6001 versus vehicle in beclin-1−/+ mice. Beclin-1, a core component of the autophagic mechanism, plays a key role in the regulation of autophagy by activating Vps34 (Wu et al. 2018). First, we found that GM6001 significantly reduced ssTBI-induced BBB disruption and inhibited the expression of MMP-9 with no effect on general autophagy markers in beclin-1−/+ mice (Fig. 5f-h; g, *P < 0.05; supplemental Fig. 3a, b; *P < 0.05). However, GM6001 could not prevent ssTBI-induced neuronal loss in the cortex of these mice (Fig. 5i, j). Similarly, GM6001 could not reduce the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the striatum (Fig. 5k, l) and the ventral mesencephalon in beclin-1−/+ mice subjected to ssTBI (Fig. 5m, n). Furthermore, we observed no differences in RotaRod or wire suspension test performance between ssTBI + vehicle and ssTBI + GM6001 beclin-1−/+ mice (Fig. 5o, p). Taken together, these results indicated that autophagy was involved in GM6001′s inhibitory effect on ssTBI-induced neurodegeneration.

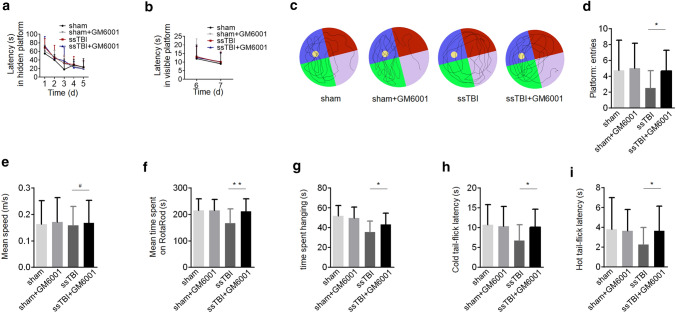

GM6001 Treatment Improved Behavioral Outcomes After ssTBI

To determine the effect of GM6001 on behavioral or functional outcomes after ssTBI, we treated mice with GM6001 or vehicle for 6 m and tested their behavior at 18 m post-injury. MWM performance in the hidden and visible platform trials did not differ among mouse groups (Fig. 6a, b; P > 0.05 by 2-way ANOVA plus Tukey’s test). However, we observed a significant improvement in probe test in the ssTBI + GM6001 group compared with the ssTBI + vehicle group (Fig. 6c, d; *P < 0.05). Swim speed and latency in finding the visible platform did not differ among groups, indicating that MWM performance was not influenced by differences in swimming ability or vision or by motivational deficits (Fig. 6b, e; #P > 0.05). Compared with vehicle-treated ssTBI mice, GM6001-treated mice significantly recovered in motor coordination and learning in the RotaRod test (Fig. 6f; **P < 0.01) and in latency-to-fall time in the wire suspension test (Fig. 6g; *P < 0.05). Furthermore, we assessed somatosensory function using nociception cold- and heat-induced tail flick tests. Latency to tail flick was significantly shorter in ssTBI mice treated with vehicle than in those treated with GM6001, indicating hyperalgesia and defective nociception toward temperature-induced pain (Fig. 6h, i; h, *P < 0.05 and i, *P < 0.05). There was a tendency for GM6001 treatment to normalize the performance of ssTBI mice on these tests. Taken together, these data suggested that GM6001 administration resulted in a possible reduction of PD-like behavioral deficits and restored some functional outcomes after ssTBI.

Fig. 6.

GM6001 treatment reduced functional deficits after ssTBI. a-e Morris water maze (MWM). Graph showing hidden platform trial (a) and visible platform trials (b). Representative images (c) and quantification (d) of probe tests. *P < 0.05. Quantification (e) of swimming speed in MWM. (f) Motor coordination by RotaRod. **P < 0.01. (g) Wire suspension performance. *P < 0.05. (h and i) Cold (h) and heat (i) tail flick latency. *P < 0.05. sham mice, n = 20; GM6001-treated sham mice, n = 20; vehicle-treated ssTBI mice, n = 20; GM6001-treated ssTBI mice, n = 25. a and b were analyzed by two-way ANOVA plus Tukey’s test. d, e, f, g, h and i were analyzed by unpaired student’s t test

Discussion

Increasing evidence has shown that neurovascular dysfunction contributes to neurodegenerative disorders including PD (Nation et al. 2019). In this study, we identified that BBB disruption by MMP-9 leads to leading to the dis-homeostasis of nervous system, in which mitophagy was inhibited. The accumulation damaged mitochondria serve as platforms to cause cell death and promoted the development of PD. Furthermore, our findings showed that treatment with GM6001, a MMP-9 inhibitor, could maintain the BBB integrity, restore ssTBI-induced suppression of mitophagy and subsequently eliminate neurotoxic proteins and damaged mitochondria, and then prevent the development of PD (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Schematic diagram summarizing the proposed role of GM6601 in TBI-induced PD

We discovered that BBB breakdown was the catalyst for the development of ssTBI-induced neurodegenerative diseases. Like many forms of acute injury, TBI causes BBB breakdown through primary injury that is felt to be refractory to treatment and secondary injury that involves multiple pathways of the neurovascular basal lamina and degradation of TJPS, which represent viable therapeutic targets (Doherty et al. 2016; Shlosberg et al. 2010). MMP-9, a member of the zinc and calcium-dependent endopeptidase family, is well known to mediate BBB injury and contribute to the morbidity and mortality after TBI (Asahi et al. 2001; Jia et al. 2014; Rosenberg et al. 1998). As reported, recognized targets of MMP-9 include extracellular-matrix (ECM) laminin, tight-junction components, growth factors, cell surface receptors and cell adhesion molecules (Choi et al. 2016; Navaratna et al. 2013; Turner and Sharp 2016). Disruption of the BBB is a key event in the secondary injury cascade following brain injury, one that exacerbates injury through a number of mechanisms leading to the dis-homeostasis of nervous system to enhance the neuroinflammatory response and neuronal death (Shlosberg et al. 2010). Indeed, alterations in other MMPs beyond MMP-9 have been observed after TBI (Shlosberg et al. 2010). But our data showed that inhibiting MMP-9 via genetic deletion or molecule drugs extenuated TBI-induced BBB breakdown, which was well known to contribute to the development of neurodegeneration (Nation et al. 2019). GM6001 treatment could reduce BBB breakdown, restore mitophagic function, attenuate mitochondrial dysfunction and promote neurorecovery after ssTBI. Taken together, these data suggested that MMP-9 might be a potential target for the treatment of BBB-breakdown-driven diseases.

PD, the second most common neurodegenerative disease, is characterized clinically by slowness of movement, rigidity, tremor and in the later stages, cognitive impairment (Mao et al. 2016). Cognitive and motoric impairments in PD are associated with dopaminergic neuron dysfunction (Mao et al. 2016). Central to the pathogenesis of PD are accumulation and aggregation of α-syn, which is a major component of LBs (Spillantini et al. 1997). α-syn is degraded via different pathways, including autophagy (Cuervo et al. 2004; Engelender 2012). The results of this study indicated that autophagy was suppressed after ssTBI and that ssTBI-induced PD-like pathology was rescued by GM6001. This proteolysis appears to represent an important target for treatment to prevent the development of ssTBI-induced PD.

Mitochondria are dynamic organelles that play key roles in many cellular functions, including energy production, oxidative stress, metabolism and cell death (Heckmann et al. 2019; Nunnari and Suomalainen 2012). One way in which neurons prevent excessive ROS production and avoid cell death is the effective elimination of dysfunctional or damaged mitochondria via a specialized autophagic process, mitophagy (Abudu et al. 2019; Lin et al. 2016). Impaired mitophagy causes an accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria, resulting in loss of dopaminergic neurons (Matheoud et al. 2016; Pickrell and Youle 2015; Wang et al. 2018). Here, our data showed that ssTBI led to the accumulation of damaged mitochondria. GM6001 treatment maintained BBB integrity and subsequently promoted the removal of such mitochondria. As expected, these results indicated that GM6001 could significantly attenuate mitochondrial fragmentation and markedly reduce ROS production by promoting the clearance of damaged mitochondria via mitophagy.

In summary, our results suggested that ssTBI led to BBB disruption and neurodegenerative development. GM6001 treatment attenuated ssTBI-induced BBB damage by inhibiting MMP-9 and prevented the development of PD by promoting the elimination of damaged mitochondria. Given that BBB breakdown is implicated in the development of several neurological diseases, further investigation is required to determine whether MMP-9 inhibition could be applied as a novel therapy for the treatment for other BBB-breakdown-driven diseases.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 (TIF 1978 kb)

Supplemental Fig. 1 GM6001 effectively reduced the level of MMP-9 induced by ssTBI. a Western blot of MMP-9 in the cortex of wild type mice at 18m after ssTBI. β-actin was used as a loading control. b Densitometry of MMP-9. n = 5/group, **P < 0.01.

Supplementary file2 (TIF 145 kb)

Supplemental Fig. 2 the level of TH in MMP-9−/+ mice subjected to brain injury. aWestern blot of TH expression in the striatum at 18m after ssTBI. β-actin was used as a loading control. b densitometry of TH. n = 5/group. *P < 0.05.

Supplementary file3 (TIF 60 kb)

Supplemental Fig. 3 GM6001 effectively reduced the level of MMP-9 in beclin-1−/+ mice subjected to brain injury. a Western blot of MMP-9 in the cortex at 18m after ssTBI. β-actin was used as a loading control. b Densitometry of MMP-9. n = 5/group, *P < 0.05.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81901258, Chao Lin, and 81972153, Jing Ji) and Zhenjiang (Grant No. SH2019030, Cai Ning).

Abbreviations

- ssTBI

Single severe traumatic brain injury

- PD

Parkinson diseases

- GFP

Green fluorescent protein

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- BBB

Blood–brain barrier

- α-syn

α-Synuclein

- MMP-9

Matrix metalloproteinase 9

Author Contributions

CL, WW, HL, YY, LH and NL designed this research and analyzed the experimental data. CL, WL, Lz and ZB performed the experiments. CL and JJ wrote the article. NC, TG and ZL did behavior tests and analyzed the experiments.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no competing interests.

Research Involving Human participants

This article does not contain any study with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Research Involving Animals

All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee and conducted in accordance with the experimental guidelines of the Nanjing Medical University.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Chao Lin, Wei Wu, Hua Lu, and Wentao Li have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Chao Lin, Email: 410linchao@163.com, Email: linchao@njmu.edu.cn.

Jing Ji, Email: jijing@njmu.edu.cn.

Ning Liu, Email: liuning_0853@163.com.

References

- Abudu YP, Pankiv S, Mathai BJ, Lamark T, Johansen T, Simonsen A (2019) NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 act as "eat me" signals to allow sustained recruitment of autophagy receptors during mitophagy. Autophagy 15(10):1845–1847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asahi M, Wang X, Mori T, Sumii T, Jung JC, Moskowitz MA, Fini ME, Lo EH (2001) Effects of matrix metalloproteinase-9 gene knock-out on the proteolysis of blood-brain barrier and white matter components after cerebral ischemia. J Neurosci 21(19):7724–7732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrio JR, Small GW, Wong KP, Huang SC, Liu J, Merrill DA, Giza CC, Fitzsimmons RP, Omalu B, Bailes J, Kepe V (2015) In vivo characterization of chronic traumatic encephalopathy using [F-18]FDDNP PET brain imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112(16):E2039–E2047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charkviani M, Muradashvili N, Lominadze D (2019) Vascular and non-vascular contributors to memory reduction during traumatic brain injury. Eur J Neurosci 50(5):2860–2876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Desai A, Kim HY (2017) Repetitive closed-head impact model of engineered rotational acceleration induces long-term cognitive impairments with persistent astrogliosis and microgliosis in mice. J Neurotrauma 34(14):2291–2302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi YK, Maki T, Mandeville ET, Koh SH, Hayakawa K, Arai K, Kim YM, Whalen MJ, Xing C, Wang X, Kim KW, Lo EH (2016) Dual effects of carbon monoxide on pericytes and neurogenesis in traumatic brain injury. Nat Med 22(11):1335–1341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuervo AM, Stefanis L, Fredenburg R, Lansbury PT, Sulzer D (2004) Impaired degradation of mutant alpha-synuclein by chaperone-mediated autophagy. Science 305(5688):1292–1295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty CP, O'Keefe E, Wallace E, Loftus T, Keaney J, Kealy J, Humphries MM, Molloy MG, Meaney JF, Farrell M, Campbell M (2016) Blood–brain barrier dysfunction as a hallmark pathology in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 75(7):656–662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelender S (2012) alpha-Synuclein fate: proteasome or autophagy? Autophagy 8(3):418–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner RC, Yaffe K (2015) Epidemiology of mild traumatic brain injury and neurodegenerative disease. Mol Cell Neurosci 66:75–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckmann BL, Teubner BJW, Tummers B, Boada-Romero E, Harris L, Yang M, Guy CS, Zakharenko SS, Green DR (2019) LC3-associated endocytosis facilitates beta-amyloid clearance and mitigates neurodegeneration in murine Alzheimer's disease. Cell 178(3):536–551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia F, Yin YH, Gao GY, Wang Y, Cen L, Jiang JY (2014) MMP-9 inhibitor SB-3CT attenuates behavioral impairments and hippocampal loss after traumatic brain injury in rat. J Neurotrauma 31(13):1225–1234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo A, Shahpasand K, Mannix R, Qiu J, Moncaster J, Chen CH, Yao Y, Lin YM, Driver JA, Sun Y, Wei S, Luo ML, Albayram O, Huang P, Rotenberg A, Ryo A, Goldstein LE, Pascual-Leone A, McKee AC, Meehan W, Zhou XZ, Lu KP (2015) Antibody against early driver of neurodegeneration cis P-tau blocks brain injury and tauopathy. Nature 523(7561):431–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahiri V, Klionsky DJ (2017) Functional impairment in RHOT1/Miro1 degradation and mitophagy is a shared feature in familial and sporadic Parkinson disease. Autophagy 13(8):1259–1261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C, Chao H, Li Z, Xu X, Liu Y, Hou L, Liu N, Ji J (2016) Melatonin attenuates traumatic brain injury-induced inflammation: a possible role for mitophagy. J Pineal Res 61(2):177–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao X, Ou MT, Karuppagounder SS, Kam TI, Yin X, Xiong Y, Ge P, Umanah GE, Brahmachari S, Shin JH, Kang HC, Zhang J, Xu J, Chen R, Park H, Andrabi SA, Kang SU, Goncalves RA, Liang Y, Zhang S, Qi C, Lam S, Keiler JA, Tyson J, Kim D, Panicker N, Yun SP, Workman CJ, Vignali DA, Dawson VL, Ko HS, Dawson TM (2016) Pathological alpha-synuclein transmission initiated by binding lymphocyte-activation gene 3. Science 353:6307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheoud D, Sugiura A, Bellemare-Pelletier A, Laplante A, Rondeau C, Chemali M, Fazel A, Bergeron JJ, Trudeau LE, Burelle Y, Gagnon E, McBride HM, Desjardins M (2016) Parkinson's disease-related proteins PINK1 and Parkin repress mitochondrial antigen presentation. Cell 166(2):314–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menard C, Pfau ML, Hodes GE, Kana V, Wang VX, Bouchard S, Takahashi A, Flanigan ME, Aleyasin H, LeClair KB, Janssen WG, Labonte B, Parise EM, Lorsch ZS, Golden SA, Heshmati M, Tamminga C, Turecki G, Campbell M, Fayad ZA, Tang CY, Merad M, Russo SJ (2017) Social stress induces neurovascular pathology promoting depression. Nat Neurosci 20(12):1752–1760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nation DA, Sweeney MD, Montagne A, Sagare AP, D'Orazio LM, Pachicano M, Sepehrband F, Nelson AR, Buennagel DP, Harrington MG, Benzinger TLS, Fagan AM, Ringman JM, Schneider LS, Morris JC, Chui HC, Law M, Toga AW, Zlokovic BV (2019) Blood-brain barrier breakdown is an early biomarker of human cognitive dysfunction. Nat Med 25(2):270–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navaratna D, Fan X, Leung W, Lok J, Guo S, Xing C, Wang X, Lo EH (2013) Cerebrovascular degradation of TRKB by MMP9 in the diabetic brain. J Clin Invest 123(8):3373–3377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunnari J, Suomalainen A (2012) Mitochondria: in sickness and in health. Cell 148(6):1145–1159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickrell AM, Youle RJ (2015) The roles of PINK1, parkin, and mitochondrial fidelity in Parkinson's disease. Neuron 85(2):257–273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg GA, Estrada EY, Dencoff JE (1998) Matrix metalloproteinases and TIMPs are associated with blood–brain barrier opening after reperfusion in rat brain. Stroke 29(10):2189–2195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo JH, Miyamoto N, Hayakawa K, Pham LD, Maki T, Ayata C, Kim KW, Lo EH, Arai K (2013) Oligodendrocyte precursors induce early blood–brain barrier opening after white matter injury. J Clin Invest 123(2):782–786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shlosberg D, Benifla M, Kaufer D, Friedman A (2010) Blood–brain barrier breakdown as a therapeutic target in traumatic brain injury. Nat Rev Neurol 6(7):393–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillantini MG, Schmidt ML, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Jakes R, Goedert M (1997) Alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature 388(6645):839–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Sharp FR (2016) Implications of MMP9 for blood brain barrier disruption and hemorrhagic transformation following ischemic stroke. Front Cell Neurosci 10:56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walchli T, Mateos JM, Weinman O, Babic D, Regli L, Hoerstrup SP, Gerhardt H, Schwab ME, Vogel J (2015) Quantitative assessment of angiogenesis, perfused blood vessels and endothelial tip cells in the postnatal mouse brain. Nat Protoc 10(1):53–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Cho YL, Tang Y, Wang J, Park JE, Wu Y, Wang C, Tong Y, Chawla R, Zhang J, Shi Y, Deng S, Lu G, Wu Y, Tan HW, Pawijit P, Lim GG, Chan HY, Zhang J, Fang L, Yu H, Liou YC, Karthik M, Bay BH, Lim KL, Sze SK, Yap CT, Shen HM (2018) PTEN-L is a novel protein phosphatase for ubiquitin dephosphorylation to inhibit PINK1-Parkin-mediated mitophagy. Cell Res 28(8):787–802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, He Y, Qiu X, Yang W, Liu W, Li X, Li Y, Shen HM, Wang R, Yue Z, Zhao Y (2018) Targeting the potent Beclin 1-UVRAG coiled-coil interaction with designed peptides enhances autophagy and endolysosomal trafficking. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115(25):E5669–E5678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong H, Wang D, Chen L, Choo YS, Ma H, Tang C, Xia K, Jiang W, Ronai Z, Zhuang X, Zhang Z (2009) Parkin, PINK1, and DJ-1 form a ubiquitin E3 ligase complex promoting unfolded protein degradation. J Clin Invest 119(3):650–660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Park J, Golinski J, Qiu J, Khuman J, Lee CC, Lo EH, Degterev A, Whalen MJ (2014) Role of Akt and mammalian target of rapamycin in functional outcome after concussive brain injury in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 34(9):1531–1539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary file1 (TIF 1978 kb)

Supplemental Fig. 1 GM6001 effectively reduced the level of MMP-9 induced by ssTBI. a Western blot of MMP-9 in the cortex of wild type mice at 18m after ssTBI. β-actin was used as a loading control. b Densitometry of MMP-9. n = 5/group, **P < 0.01.

Supplementary file2 (TIF 145 kb)

Supplemental Fig. 2 the level of TH in MMP-9−/+ mice subjected to brain injury. aWestern blot of TH expression in the striatum at 18m after ssTBI. β-actin was used as a loading control. b densitometry of TH. n = 5/group. *P < 0.05.

Supplementary file3 (TIF 60 kb)

Supplemental Fig. 3 GM6001 effectively reduced the level of MMP-9 in beclin-1−/+ mice subjected to brain injury. a Western blot of MMP-9 in the cortex at 18m after ssTBI. β-actin was used as a loading control. b Densitometry of MMP-9. n = 5/group, *P < 0.05.