Abstract

Background.

Nontyphoidal Salmonella is the leading cause of bacterial gastroenteritis in the United States. Meal replacement products containing raw and ‘superfood’ ingredients have gained increasing popularity among consumers in recent years. In January 2016, we investigated a multistate outbreak of infections with a novel strain of Salmonella Virchow.

Methods.

Cases were defined using molecular subtyping procedures. Commonly reported exposures were compared with responses from healthy people interviewed in the 2006–2007 FoodNet Population Survey. Firm inspections and product traceback and testing were performed.

Results.

Thirty-five cases from 24 states were identified; 6 hospitalizations and no deaths were reported. Thirty-one (94%) of 33 ill people interviewed reported consuming a powdered supplement in the week before illness; of these, 30 (97%) reported consuming Product A, a raw organic powdered shake product consumed as a meal replacement. Laboratory testing isolated the outbreak strain of Salmonella Virchow from: leftover Product A collected from ill people’s homes, organic moringa leaf powder (an ingredient in Product A), and finished product retained by the firm. Firm inspections at three facilities linked to Product A production did not reveal contamination at the facilities. Traceback identified that the contaminated moringa leaf powder was imported from South Africa.

Conclusions.

This investigation identified a novel outbreak vehicle and highlighted the potential risk with similar products not intended to be cooked by consumers before consuming. The company issued a voluntary recall of all implicated products. As this product has a long shelf-life, the recall likely prevented additional illnesses.

Keywords: Salmonella, raw food, organic food, supplement, outbreak

Introduction

Salmonella enterica is a diverse pathogen with >2,500 recognized serotypes, many animal and environmental reservoirs, and varying degrees of pathogenicity in human hosts [1, 2]. Burden estimates attribute 1 million foodborne illnesses to salmonellosis in the United States annually, and Salmonella is the leading cause of bacterial gastroenteritis [3]. Nontyphoidal Salmonella enterica is the second most common cause of foodborne disease outbreaks in the United States, and poultry and fresh produce consumption are well established outbreak vehicles [4, 5]. Low-moisture foods, including spices and seasonings; dried protein products such as dried egg or dried milk; and seeds have been increasingly implicated as the source of foodborne salmonellosis outbreaks [6–8].

Raw food diets and consumption of ‘superfoods’ have gained increasing interest among consumers in recent years. While there are no standard definitions or official guidelines to what companies can market as ‘raw’ foods or ‘superfoods’, raw generally refers to ingredients or foods, including fruits, nuts, and sprouted seeds that are unprocessed and/or minimally cooked [9]. Some raw ingredients or foods might be heated, but often at temperatures that are not high enough to eliminate pathogenic microorganisms or to reduce the potential for foodborne illness. ‘Superfood’ is a marketing term for nutrient-dense foods, such as chia seeds, quinoa, and blue-green algae, with purported health benefits [10]. We report on an investigation of a multistate outbreak of infections with a novel strain of Salmonella Virchow linked to an organic raw powdered meal replacement product sold nationwide.

Methods

Detection of the Outbreak

On January 11, 2016, PulseNet, the national molecular subtyping network for foodborne disease surveillance [11], detected a cluster of six Salmonella Virchow infections from five states with an indistinguishable pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) pattern. This was a new pattern to the PulseNet database. An underlying assumption of PulseNet for multistate outbreak detection is that bacterial isolates with indistinguishable PFGE patterns are more likely to share a common source, especially if the PFGE pattern is novel or rare. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), local and state health departments, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) initiated a multistate investigation of the outbreak to determine the source and prevent additional illnesses.

Case Definition and Case Finding

A case was defined as infection with the outbreak strain of Salmonella Virchow (PFGE XbaI pattern TDXX01.0219) in a person with illness onset dates, or isolation dates if illness onsets were unknown, from December 5, 2015 to April 26, 2016.

PulseNet was used to detect cases. Salmonella isolates from ill people were sent to PulseNet-affiliated public health laboratories for PFGE using standardized protocols [12]. In addition, PulseNet USA shared the PFGE pattern with PulseNet International, a global laboratory network dedicated to bacterial foodborne disease surveillance, comprised of the national, regional, and sub-regional laboratory networks of Africa, Asia Pacific, Canada, Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean, and the Middle East to identify possible cases outside the United States [13].

Hypothesis Generation

To determine the source of the outbreak, state and local public health officials interviewed ill people with state-specific enteric disease questionnaires to identify common foods and other exposures occurring in the week preceding illness onset. CDC compared exposures commonly reported by ill people with responses from healthy people previously interviewed as part of the 2006–2007 FoodNet Population Survey. This survey asked people residing in the surveillance areas about various exposures, including foods consumed in the week before interview, and is representative of 15% of the U.S. population [14]. After investigators identified a suspected food product, CDC developed a focused questionnaire to collect brand, flavor, and other detailed product and purchase information about the suspected food product and similar foods consumed in the week before illness onset. State and local public health officials used this questionnaire for subsequent interviews.

Traceback Investigation and Firm Inspections

Based on lot numbers, best-by dates, and other information about the suspected food product obtained during interviews with ill people, FDA conducted a traceback investigation to determine whether there was a common source of contamination in the production or distribution chain for the suspected product consumed by case-patients. FDA inspected two facilities involved in the production of the suspected product to collect environmental samples and assess manufacturing practices. During the investigations of these facilities, FDA also collected samples of raw ingredients and unopened packages of retained finished product. In addition, FDA inspected a third facility that supplied ingredients for the suspected product and collected environmental and ingredient samples. All environmental, ingredient, and finished product samples collected during these inspections were sent to FDA laboratories and tested for the presence of Salmonella [15].

Additional Product Testing

State departments of health and agriculture collected opened containers of the suspected food product from the homes of ill people and unopened containers from retail stores for pathogen testing in state laboratories. State and federal laboratories performed serotyping and subtyping by PFGE using standard PulseNet protocols on all Salmonella isolates identified [12].

Results

Description of the Outbreak

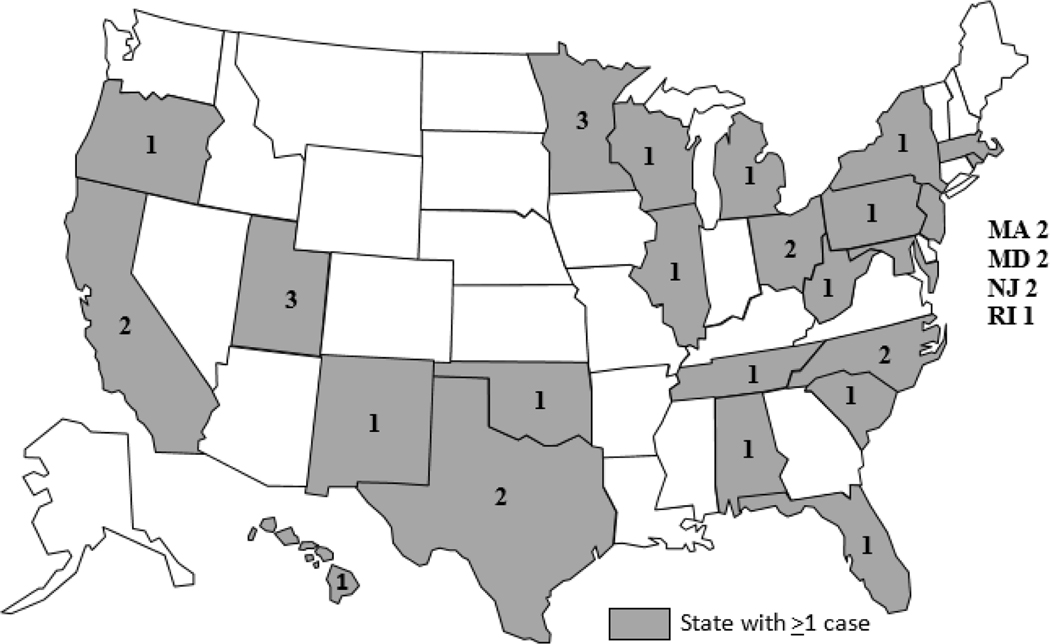

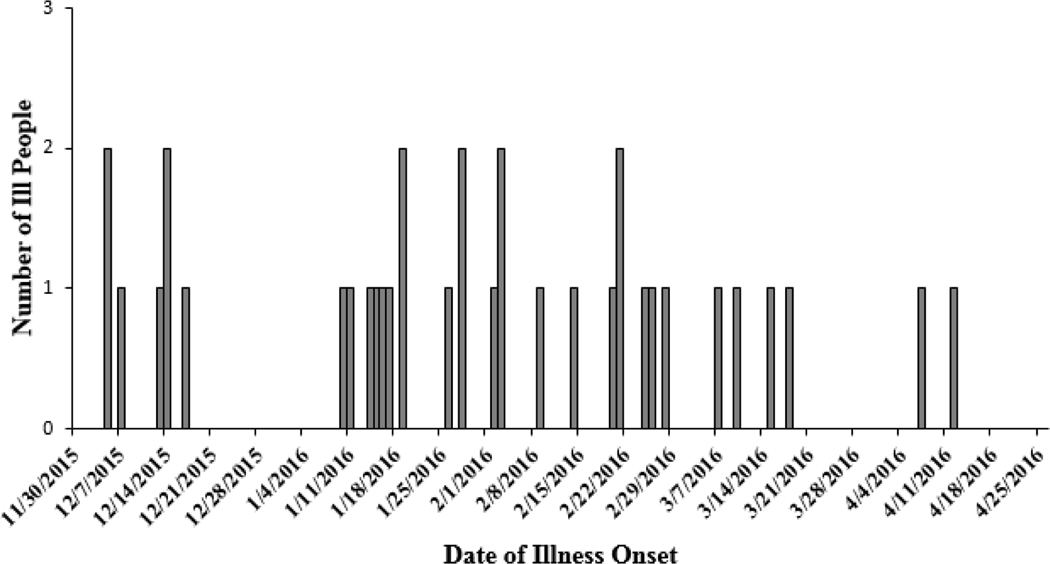

A total of 35 cases were identified from 24 states (Fig 1); illness onset dates ranged from December 5, 2015 to April 12, 2016 (Fig 2). The median age of ill people was 35 years (range <1–84 years); 58% were female. Six (22%) of 27 ill people with available information were hospitalized, and no deaths were reported. No cases were identified outside of the United States.

Figure 1.

Outbreak-associated Salmonella Virchow cases by state of residence, United States, December 5, 2015–April 26, 2016 (n=35)

Figure 2.

Outbreak-associated cases of Salmonella Virchow by date of illness onset, United States, December 5, 2015–April 12, 2016 (n=35)

Hypothesis Generation

Review of five state-specific questionnaires available on January 25, 2016, revealed that 5 (100%) ill people reported eating leafy green vegetables and 4 (80%) ill people reported eating chicken. However, a variety of different types of chicken and leafy greens were reported. These food items were not reported significantly more frequently by ill people than healthy people in the FoodNet Population Survey. Three (60%) ill people reported consuming powdered supplements, but the type and brand of powdered supplement consumed was initially available for only one ill person from Minnesota. Oregon and Utah state health partners re-interviewed the other two ill people who reported consuming powdered supplements to obtain additional information about the products. All three ill people reported consuming the same brand of raw powdered meal replacement product (hereafter defined as “Product A”).

Based on this information, investigators developed a questionnaire focusing on powdered supplements and powdered meal replacements to collect detailed product and purchase information. On January 29, 2016, eight (100%) of eight ill people interviewed reported consuming Product A in the week before becoming ill; of these, six provided product lot numbers and best-by dates. Three common lot numbers with the same best-by date of September 2017, were identified among the six ill people.

At the conclusion on the investigation, 31 (94%) of 33 ill people interviewed with the focused questionnaire reported consuming a powdered supplement or a powdered meal replacement product in the week before becoming ill; of these, 30 (97%) reported consuming Product A. Detailed product information on lot numbers and flavors was available from 22 ill people. Seven lot numbers were identified, with the best-by dates of September 2017 and October 2017. Three of the four flavors of Product A available for purchase were reported by ill people, with chocolate (n=12) and vanilla (n=9) most commonly reported.

Traceback Investigation and Firm Inspections

Product A is an organic, shelf-stable, powdered product intended to be rehydrated by the consumer to consume as a drinkable snack or meal replacement shake. It contains over 40 raw organic ingredients, including plant-based proteins, seeds, sprouts, greens, fruits, and vegetables. It also contains live probiotics, enzymes, vitamins, and minerals. Product A is marketed as a healthy and nutritious raw and organic meal replacement.

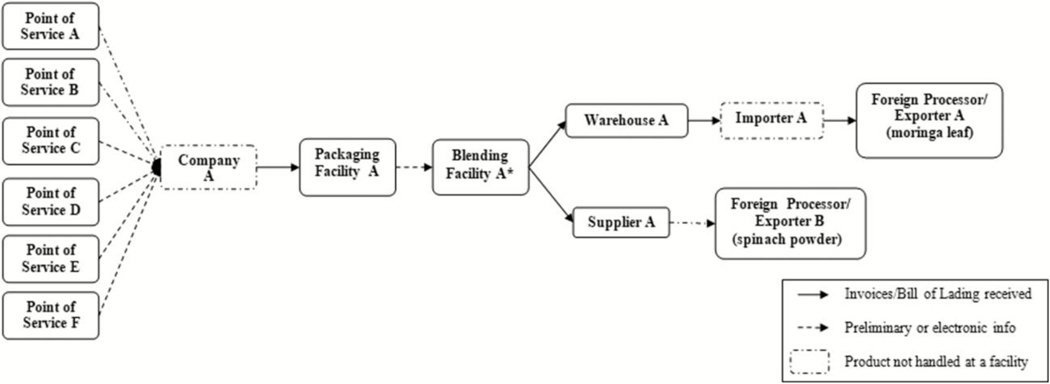

During its traceback investigation, FDA determined that Product A was blended and packaged by the manufacturer (Company A) in two facilities in Utah, and then distributed nationally (Fig 3). FDA inspected the blending and packaging facilities in early February 2016, and did not identify any production practices that might lead to contamination. Three pooled environmental samples (242 swabs total) collected from the blending and packaging facilities were cultured by FDA and did not yield Salmonella.

Figure 3.

Informational Traceback Diagram, Product A January 2016. Points of Service included in the traceback had cases with the most complete and available purchasing and product information as of 7/26/2016. *The raw ingredient, moringa leaf, yielded the outbreak strain of Salmonella Virchow.

FDA also collected 16 samples of individual raw ingredients used to make Product A. Two of these 16 samples yielded Salmonella: one sample of organic moringa leaf powder and one sample of spinach powder. The sample of organic moringa leaf powder yielded the outbreak strain of Salmonella Virchow. The sample also yielded Salmonella Zanzibar and Salmonella II 42:z29:−. The sample of spinach powder yielded Salmonella Enteritidis only. Neither of these two raw ingredients nor the finished product were heat-treated or otherwise treated with a processing step to eliminate bacterial pathogens before packaging.

The results of microbiological testing prompted further traceback investigations of both contaminated raw ingredients. Company A used the organic moringa leaf powder exclusively to manufacture Product A. The organic moringa leaf powder was supplied by an exporter in South Africa (Exporter A). The shipments of organic moringa leaf were imported via a company in Washington (Importer A); the shipments went from Exporter A in South Africa to a warehouse in the United States (Warehouse A) and then were shipped to the manufacturing facilities in Utah. The investigation also identified that in September 2015, Company A had reformulated Product A to include moringa leaf powder in Product A for the first time. Product A has a two-year shelf life, thus the best-by dates reported during this investigation correspond to the time that the formulation changed [16].

Review of records indicated the contaminated spinach powder was supplied by a supplier in Illinois (Supplier A). FDA inspected this facility and did not identify any production practices that might lead to contamination at the facility. FDA collected one pooled environmental sample (125 swabs total) and 14 samples of products available at the time of inspection, including spinach powder, for testing; none yielded Salmonella. Further investigation determined that Product A packages containing the contaminated lot of spinach powder had not been distributed to retailers and, thus, would not have been available for purchase by consumers.

Additional Product Testing

State partners collected seven open containers of leftover Product A from the homes of ill people in six states. Testing isolated the outbreak strain of Salmonella Virchow from three opened containers of leftover product collected from the homes of ill people in Oklahoma, Utah, and Oregon. The leftover product from Utah also yielded Salmonella Zanzibar and Salmonella II 42:z29:−. The PFGE patterns of these two isolates were indistinguishable from those of the Salmonella isolated from a sample of organic moringa leaf powder collected by FDA at the blending facility. A query of the PulseNet database did not identify any human illnesses with Salmonella Zanzibar or Salmonella II 42:z29:−. Twelve unopened containers having the same lot numbers as those reported by ill people were collected from various retail stores in Minnesota, and testing did not yield Salmonella.

Public Health Action

Based on information from the epidemiologic investigation, on January 29, 2016, Company A voluntarily recalled 30 lots of Product A with best-by dates of August 2017–October 2017. After isolating the outbreak strain of Salmonella Virchow from organic moringa leaf powder, the company expanded the recall on February 12, 2016, to include all lots containing this raw ingredient [16]. Company A also announced the removal of organic moringa leaf powder from all of its products.

On February 24, 2016, FDA detained an incoming shipment of organic moringa leaf powder from Exporter A. On March 16, 2016, FDA placed Exporter A on Import Alert 99–19 based on investigation findings showing that moringa leaf powder from Exporter A was contaminated with Salmonella [17]. The import alert stipulated that Exporter A was found to be in violation of FDA regulations, and that moringa leaf powder from Exporter A may no longer be accepted into in the United States. The import alert also informed FDA field personnel that shipments of organic moringa leaf from this exporter may be detained until the exporter provides evidence that these products are not contaminated with Salmonella.

Throughout the investigation, CDC, FDA, and state partners issued public communications to inform consumers of the investigation findings, product recalls, and actions they could take to prevent illness. These communications included web announcements, social media messaging, and state and national media reports [18, 19].

Discussion

We describe a nationwide outbreak of Salmonella Virchow infections linked to a powdered meal replacement product made with organic, raw ingredients. Past illness outbreaks have been linked to dietary supplements or food supplements, including a 1966 salmonellosis outbreak linked to a food supplement that was served as a warm gruel in multiple institutions [20–23]. This investigation identified a raw, reconstituted meal replacement shake as a novel vehicle causing a multistate salmonellosis outbreak. The strong epidemiologic signal of nearly all ill people consuming a rare product was supported by isolating the outbreak strain from the implicated food product and one of its raw ingredients. The outbreak investigation led to a nationwide recall of all Product A lots containing the contaminated organic moringa leaf powder, which likely prevented additional illnesses.

Powdered products such as Product A are shelf-stable foods with low water activity, also referred to as low-moisture foods. Salmonella is the most frequently implicated pathogen in reported enteric illness outbreaks linked to low-moisture foods [21, 24, 25]. In a recent review of worldwide low-moisture food outbreaks, Salmonella was found to have caused 45% of the outbreaks [6]. Additionally, Salmonella can survive in low-moisture foods such as black pepper, peanut butter, and powdered products for over a year under normal storage conditions [26–28]. Although low-moisture foods do not normally support the growth of Salmonella, once contaminated, Salmonella can survive at levels sufficient to cause clinical illness if consumed, as demonstrated by this and other foodborne salmonellosis outbreaks linked to low-moisture foods. Some examples include a 2007 outbreak linked to a broccoli powder added to a vegetable-coated snack food, a 2008 outbreak linked to peanut butter and other peanut products, and a 2009 outbreak linked to black and red pepper used to coat dried salami [7, 24, 29]. Since Salmonella had the potential to survive in the contaminated Product A for much of its 2-year shelf life, a prolonged outbreak with additional illnesses would likely have occurred without the recall.

Meal replacement products have grown in popularity in the United States with product sales increasing from $8.2 billion in 2011 to $10.7 billion in 2014 [30]. These products are marketed as weight loss aides, nutritional supplements, or convenience foods for consumers with busy lifestyles. Meal replacement products are sold in a variety of forms, including dry powders that are reconstituted as shakes, and can be made from raw organic plant or animal derived ingredients, often sourced from a global supply chain. When manufacturing processes lack controls to effectively reduce microbial burden, pathogen contamination of any ingredients could result in contamination of the final product, which might lead to human illnesses when consumed [28].

Product A was marketed as a raw, organic, healthy meal replacement and shake, containing multiple ‘superfoods’ and other nutritional benefits, such as a rich source of vitamins, minerals, protein, and antioxidants. Products marketed as ‘superfoods’ and raw foods appear to be increasingly important vehicles for foodborne Salmonella outbreaks, which might coincide with the rise in the number of products available. Over the course of the year 2015, there was a 30% rise in ‘superfood’ products in the United States [31]. As the popularity of these ‘superfoods’ has increased, CDC and state health partners have identified foodborne outbreaks linked to them. For example, a 2014 outbreak involving multiple Salmonella serotypes was linked to raw sprouted chia powder in the United States and Canada [32, 33]. Another example is the 2015 outbreak of Salmonella Paratyphi B variant L(+) tartrate(+) infections linked to raw sprouted nut butter spreads [34].

Although the ultimate cause of Product A contamination in this outbreak was not determined, isolating the Salmonella Virchow outbreak strain from the organic moringa leaf powder supports that this ingredient was likely the means by which Product A became contaminated. This is further supported by the fact that Company A started using moringa leaf powder from the implicated supplier shortly before the outbreak began [16]. Moringa leaf, which comes from the moringa tree (Moringa oleifera) grows throughout tropical and subtropical countries [35]. All parts of the moringa tree, including the leaves, immature pods, seeds, bark, and flowers, are widely used and reported to be highly nutritious and display a number of medicinal properties [35, 36].

Application of a pathogen reduction treatment, such as heat pasteurization or irradiation, to low-moisture food products aims to reduce the risk of product contamination and foodborne illness [26]. During the production of Product A, no pathogen reduction treatment was applied to any of the raw ingredients or the finished product before Product A was distributed to consumers. This was an intentional practice by the manufacturer since it advertises health benefits attributed to the raw product. However, if a pathogen reduction step had been applied during the production of Product A it could have mitigated the risk.

This investigation identified a novel outbreak vehicle responsible for illness in 35 people in 24 states. It highlights the potential food safety risk carried by raw powdered ingredients that do not undergo a pathogen reduction step during their manufacture. This investigation also demonstrates the importance of close collaboration among state and federal public health investigators to resolve foodborne outbreaks quickly and decisively to prevent additional cases of illness, particularly when shelf-stable products are implicated. Finally, this outbreak emphasizes the complex nature of food safety when raw food products are not intended to be cooked by the consumer before use—for these types of products, food safety depends on both the careful manufacture and distribution of the final product as well as the use of ingredients that are free from contamination.

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank local, state, and federal public health and regulatory officials in jurisdictions affected by the outbreak for their assistance with and contributions to this investigation, including the following: Alabama; California; Florida; Hawaii; Illinois; Massachusetts; Maryland; Michigan; Minnesota; North Carolina; New Jersey; New Mexico; New York; Ohio; Oklahoma; Oregon; Pennsylvania; Rhode Island; South Carolina; Tennessee; Texas; Utah, Salt Lake County and Utah County Health Departments; Wisconsin; West Virginia; and U.S. Food and Drug Administration Denver Laboratory, Human and Animal Food Division 1 E (New York District), Division 6E (Chicago District), Division 4E (Florida District), Division 5E (New Orleans), Division 1W (Minneapolis District), Division 3W (Dallas District), Division 4W (Denver District), Division 5W (Los Angeles District), Division 6W (Seattle District), and Division of South West Imports.

Funding:

The authors have no funding sources to disclose.

Disclaimer:

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or institutions with which the authors are affiliated.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Serotypes and the Importance of Serotyping Salmonella. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/reportspubs/salmonella-atlas/serotyping-importance.html. Accessed 5 April 2017.

- 2.Jones TF, Ingram LA, Cieslak PR et al. Salmonellosis outcomes differ substantially by serotype. J Infect Dis. 2008; 198(1): 109–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scallan E, Hoekstra RM, Angulo FJ, et al. Foodborne illness acquired in the United States--major pathogens. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011; 17(1): 7–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crowe SJ, Mahon BE, Vieira AR, Gould LH. Vital Signs: Multistate Foodborne Outbreaks - United States, 2010–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015; 64(43): 1221–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surveillance for Foodborne Disease Outbreaks, United States, 2014, Annual Report. US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Young I, Waddell L, Cahill S, Kojima M, Clarke R, Rajic A. Application of a Rapid Knowledge Synthesis and Transfer Approach To Assess the Microbial Safety of Low-Moisture Foods. J Food Prot. 2015; 78(12): 2264–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sotir MJ, Ewald G, Kimura AC, et al. Outbreak of Salmonella Wandsworth and Typhimurium infections in infants and toddlers traced to a commercial vegetable-coated snack food. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009; 28(12): 1041–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Doren JM, Neil KP, Parish M, Gieraltowski L, Gould LH, Gombas KL. Foodborne illness outbreaks from microbial contaminants in spices, 1973–2010. Food Microbiol. 2013; 36(2): 456–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hobbs SH. Attitudes, practices, and beliefs of individuals consuming a raw foods diet. Explore (New York, NY) 2005; 1(4): 272–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cunningham E What is a raw foods diet and are there any risks or benefits associated with it? J Am Diet Assoc. 2004; 104(10): 1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swaminathan B, Barrett TJ, Hunter SB, Tauxe RV. PulseNet: the molecular subtyping network for foodborne bacterial disease surveillance, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001; 7(3): 382–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ribot EM, Fair MA, Gautom R, et al. Standardization of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis protocols for the subtyping of Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella, and Shigella for PulseNet. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2006; 3(1): 59–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nadon C, Van Walle I, Gerner-Smidt P, Campos J, Chinen I, Concepcion-Acevedo J et al. PulseNet International: Vision for the implementation of whole genome sequencing (WGS) for global food-borne disease surveillance. Euro Surveill. 2017; 22(23). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Foodborne Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet) Population Survey Atlas of Exposures, 2006–2007. US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.United States Food and Drug Administration. Bacteriological Analytical Manual (BAM). Available at: https://www.fda.gov/Food/FoodScienceResearch/LaboratoryMethods/ucm2006949.htm. Accessed 1 June 2017.

- 16.Cabrera D RAW Meal Voluntary Recall Expanded to Include Additional Lots. 2016. Available at: https://www.gardenoflife.com/content/raw-meal-voluntary-recall-expanded-to-include-additional-lots/. Accessed 15 June 2017.

- 17.United States Food and Drug Administration. Import Alert 99–19, “Detention Without Physical Examination Of Food Products Due To The Presence of Salmonella”. 2016. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cms_ia/importalert_263.html. Accessed 8 May 2017.

- 18.Minnesota Department of Health. State officials investigating Salmonella cases linked to powdered meal replacement. 2016. Available at: http://www.health.state.mn.us/news/pressrel/2016/salmonella012916.html. Accessed 2 May 2017.

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Multistate Outbreak of Salmonella Virchow Infections linked to a powdered meal replacement product (final update). 2016. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/virchow-02-16/. Accessed 2 May 2017.

- 20.Stocker P, Rosner B, Werber D et al. Outbreak of Salmonella Montevideo associated with a dietary food supplement flagged in the Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed (RASFF) in Germany, 2010. Euro Surveill. 2011; 16(50): 20040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCall CE, Collins RN, Jones DB, Kaufmann AF, Brachman PS. An interstate outbreak of salmonellosis traced to a contaminated food supplement. Am J Epidemiol. 1966; 84(1): 32–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foley S, Butlin E, Shields W, Lacey B. Experience with OxyELITE pro and acute liver injury in active duty service members. Dig Dis Sci. 2014; 59(12): 3117–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacFarquhar JK, Broussard DL, Melstrom P et al. Acute selenium toxicity associated with a dietary supplement. Arch Intern Med. 2010; 170(3): 256–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gieraltowski L, Julian E, Pringle J et al. Nationwide outbreak of Salmonella Montevideo infections associated with contaminated imported black and red pepper: warehouse membership cards provide critical clues to identify the source. Epidemiol Infect. 2013; 141(6): 1244–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beuchat LR, Komitopoulou E, Beckers H et al. Low-water activity foods: increased concern as vehicles of foodborne pathogens. J Food Prot. 2013; 76(1): 150–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keller SE, VanDoren JM, Grasso EM, Halik LA. Growth and survival of Salmonella in ground black pepper (Piper nigrum). Food Microbiol. 2013; 34(1): 182–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rachon G, Penaloza W, Gibbs PA. Inactivation of Salmonella, Listeria monocytogenes and Enterococcus faecium NRRL B-2354 in a selection of low moisture foods. Int J Food Microbiol. 2016; 231: 16–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Podolak R, Enache E, Stone W, Black DG, Elliott PH. Sources and risk factors for contamination, survival, persistence, and heat resistance of Salmonella in low-moisture foods. J Food Prot. 2010; 73(10): 1919–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cavallaro E, Date K, Medus C, et al. Salmonella typhimurium infections associated with peanut products. N Engl J Med. 2011; 365(7): 601–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lundahl D 2014 Meal Replacement Study: 5 Mega-Trends. 2014. Available at: https://cdn2.hubspot.net/hub/148641/file-1355689198-pdf/docs/2014_meal_replacement_mega-trends_report.pdf.html. Accessed 24 August 2016.

- 31.Mintel Marketing. Super growth for “super” foods: New product development shoots up 202% globally over the past five years. 2016. Available at: http://www.mintel.com/press-centre/food-and-drink/super-growth-for-super-foods-new-product-development-shoots-up-202-globally-over-the-past-five-years. Accessed 17 May 2017.

- 32.Dechet AM, Herman KM, Chen Parker C, et al. Outbreaks caused by sprouts, United States, 1998–2010: lessons learned and solutions needed. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2014; 11(8): 635–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harvey RR, Heiman Marshall KE, Burnworth L et al. International outbreak of multiple Salmonella serotype infections linked to sprouted chia seed powder, USA and Canada, 2013–2014. Epidemiol Infect. 2017; 145(8): 1535–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Multistate Outbreak of Salmonella Paratyphi B variant L(+) tartrate(+) Infections Linked to JEM Raw Brand Sprouted Nut Butter Spreads (final update). 2016. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/paratyphi-b-12-15/. Accessed 2 May 2017.

- 35.Stohs SJ, Hartman MJ. Review of the Safety and Efficacy of Moringa oleifera. Phytother Res. 2015; 29(6): 796–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anwar F, Latif S, Ashraf M, Gilani AH. Moringa oleifera: a food plant with multiple medicinal uses. Phytother Res. 2007; 21(1): 17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]