Abstract

Objective:

In order to properly understand the correlation between TN and Chiari malformation type I (CMI), it is imperative to delve into the underlying processes and develop efficacious treatment strategies.

Methods:

A comprehensive search was performed regarding trigeminal neuralgia (TN) in individuals diagnosed with CMI. A total of 19 cases were identified in the existing literature.

Results:

The review of 19 studies showed that the most commonly affected division was V2 (31.6%), followed by V3 (10.5%) and V1 (5.3%). Radiological findings were variable. The medulla oblongata was compressed in 6 patients (31.6%), the cervical spinal cord showed abnormalities in 3 patients (15.8%) abnormalities; one cervical myelocele (5.26%), two cervical syringomyelia (10.53%) while 5 patients (26.3%) showed normal findings. The skull bones in 4 patients (21,1%) showed deformity in the form of small posterior fossa or platybasia. The surgical treatment was conducted in 14 patients (73.7%). The study suggested that posterior fossa decompression (PFD) plus microvascular decompression (MVD) dual surgical modality yielded the best results for V2 distribution (P=0.017).

Conclusion:

Chiari malformation type I can directly influence the occurrence and severity of trigeminal neuralgia. Therefore, an effective management of this malformation, like neurovascular decompression, PFD or ventriculoperitoneal shunt, can act as a potential treatment for trigeminal neuralgia. While the PFD alone was effective in the V3 and V1 distribution of trigeminal neuralgia, PFD plus microvascularplus plus microvascular decompression (MVD) as a dual surgical modality yielded the best results for V2 distribution.

Keywords: Chiari malformation, microvascular decompression, posterior fossa decompression, trigeminal neuralgia

Introduction

Highlights

Vascular compression and subsequent demyelination at the entry zone of the trigeminal nerve root are plausible hypotheses regarding the origin of this phenomenon.

The crucial importance of sophisticated diagnostic imaging in precisely detecting and distinguishing TN linked with CMI.

It is essential to customize therapies according to the exact division of the trigeminal nerve implicated (V1, V2, or V3) in order to maximize results.

Posterior fossa decompression and microvascular decompression when used together provide encouraging outcomes, particularly for V2 distribution.

Trigeminal neuralgia (TN) is a condition characterized by recurrent, sudden, and intense but brief lancinating pain typically localized in the distribution of one or more branches of the trigeminal nerve1–9. It affects an estimated 4.7 individuals per 100 000 persons10. The most common cause of TN is the compression of the trigeminal nerve root, often by an artery or vein, which leads to irritability of the nerve due to demyelination and remyelination at the root entry zone6,10. However, TN can also result from central lesions such as multiple sclerosis, tumors, and brainstem infarcts6,10–19.

In contrast, Chiari malformation type I (CMI) is a complex syndrome characterized by the herniation of cerebellar tonsils into the cervical canal. Its exact pathogenesis remains elusive, with theories suggesting a link to anomalies in the embryological development of the skull base9 or chronic herniation of normally developed structures20. Patients with CMI could be asymptomatic or present with various pain syndromes, as well as more severe cranial nerve and long tract dysfunctions21. The presence or absence of associated conditions like hydrocephalus, basilar invagination, and syringomyelia further complicates the clinical picture22.

Interestingly, in certain reported patients with unilateral TN in the context of CMI malformation, surgical interventions such as posterior fossa decompression (PFD) or shunting procedures have shown promise in alleviating TN symptoms6,10.

While primary (idiopathic) TN is the more common presentation, it can, in rare instances, arise as a secondary condition due to intracranial causes19,23. Diagnosis typically relies on clinical history, a negative neurological examination, and a positive response to carbamazepine treatment. MRI plays a crucial role in cases where the diagnosis is uncertain or other neurological disorders are suspected19,23. Neuroimaging is vital in identifying intracranial causes, which may account for up to 15% of TN cases, differentiating between primary and secondary TN, and guiding appropriate diagnosis and management19,23,

In some unusual cases, TN may also be associated with CMI. This article aims to examine the distribution of disease characteristics among patients, ascertain which divisions of the trigeminal nerve are predominantly affected in conjunction with CMI, and evaluate the impact of various treatment modalities on clinical outcomes.

Methods

The aims and objectives of the study were carefully considered, and a protocol was written to reflect that. Methods for conducting the search, extracting data, synthesizing data, determining which should be included, evaluating the quality of the studies, and ultimately screening them were all documented in the protocol. This review follows the guidelines established by Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA).

Search

A search for Observational studies, series of cases and case reports was carried out through PUBMED (January 1950 until August 2023); SCOPUS (January 1950 until August 2023); Central Cochrane Registry of Controlled Trials (The Cochrane Library) (January 1950 until August 2023); MEDLINE (Ovid) January 1950 until August 2023; EMBASE (Ovid); CINAHL (January 1950 until August 2023); in addition to the reference list of included studies and other relevant data in addition to potentially eligible studies. The strategy will include subject headings (MeSH) and text words connected with Booleans term. Some of the studies that had been reported in the literature in English, the data extraction from other studies in other languages were collected by their mother tongue speakers (medical field workers). The patients didn’t have a particular age for inclusion.

Selection criteria

Inclusion criteria

Studies related to the association between trigeminal neuralgia (TN) and Chiari malformation type I (CMI).

Documents containing demographic data, clinical symptoms, radiological findings, treatment options, outcomes, and follow-up information of patients with CMI and TN.

Studies examining the effects of different treatment interventions, including neurovascular decompression, PFD, or ventriculoperitoneal shunt in managing TN associated with CMI.

Exclusion criteria

Reports without relation between TN and CM type I.

Lacking detailed patient’s information as symptoms, outcomes and follow-up.

The study’s inclusion criteria encompassed research publications published between the years 1950 and August 2023. After removing duplicate and ineligible papers, a thorough analysis of the full-text studies was performed.

Extraction and management of data

The recorded data encompassed patient demographics including sex and age, as well as symptoms, imaging findings, therapy methods, outcome, and follow-up. In order to find the articles that met the systematic review’s inclusion criteria, we screened their titles and abstracts and then read them in their entirety. The studies that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were subjected to a thorough critical review by two reviewers. We first looked at the titles with keywords, then at the abstracts, and finally at the full texts of those that seemed relevant. At the full-text screening stage, all studies were reviewed by an independent reviewer to ensure eligibility. Articles that were selected or included differently by each of the three reviewers were briefly discussed until a consensus was reached.

Results

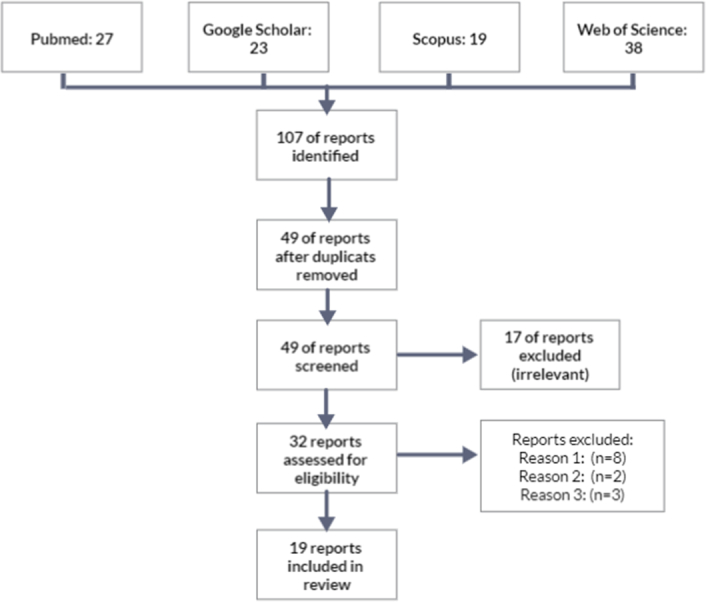

After meticulous screening, a total of 19 studies were deemed suitable based on stringent criteria applied to initial searches across PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar databases (Fig. 1). This study delved into an analysis of patient-level data from a cohort of 19 individuals who presented diverse underlying neuralgia across the three trigeminal nerve divisions associated with CMI.

Figure 1.

Prisma flowchart. Reason 1: Commentary. Reason 2: Erratum. Reason 3: Full-text not available.

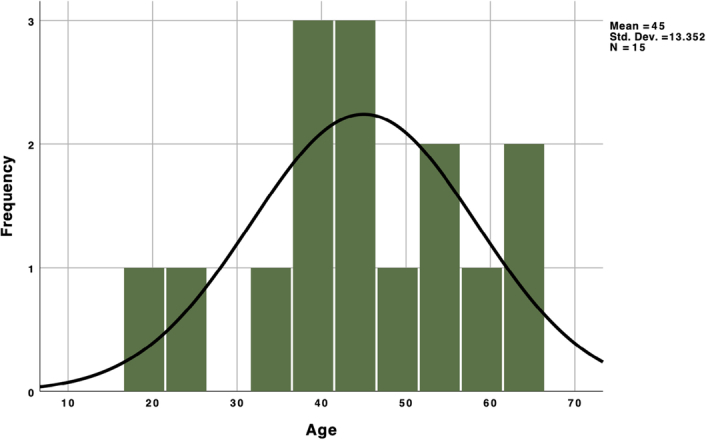

The distribution of ages demonstrated that the middle 50% of participants fell between 38 and 56 years, with the median age being 44 years (Fig. 2). Among these, 10 individuals were identified as male, accounting for 52.6% of the total cohort. There were no discernible statistically significant gender preferences. Refer to (Table 1) for an overview of patient attributes, including symptoms.

Figure 2.

Histogram showing the age distribution in patients with trigeminal neuralgia.

Table 1.

Showing the patients characteristics and the affected division of the trigeminal nerve

| No. | Author | Sex | Age | Side of TN | V1 | V2 | V3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jose Alberto1 1982 | Male | 46 | Left | No | Yes | Yes |

| 2 | Ayuso-Peralta et al.2 1999 | Male | 44 | Left | No | Yes | No |

| 3 | V Iváñez3 1999 | Male | 39 | Right | No | Yes | No |

| 4 | Rosetti et al.4 1999 | Male | 66 | Left | No | Yes | Yes |

| 5 | Chakraborty et al.5 2003 | Female | 38 | Left | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 6 | Gnanalingham et al.6 2004 | Male | 31 | Right | — | — | — |

| 7 | Teo et al.7 2005 | Female | 38 | Right | No | No | Yes |

| 8 | Monzillo et al.8 2007 | Female | 54 | Left | No | Yes | Yes |

| 9 | Dahdaleh et al.9 2008 | Female | 19 | Right | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 10 | Caranci et al.10 2008 | Female | 36 | Left | Yes | No | No |

| 11 | Papanastassiou11 2008 | Male | 63 | Left | No | Yes | No |

| 12 | Panconesi12 2009 | Male | 54 | — | — | — | — |

| 13 | Vince et al.13 2010 | Female | 50 | Bilateral | No | V2 | No |

| 14 | Than et al.14 2011 | Female | 56 | Bilateral | No | No | Yes |

| 15 | Gomez-Camello15 2013 | Male | 44 | Left | No | Yes | No |

| 16 | Liu et al.16 2014 | Male | 24 | Left | No | Yes | Yes |

| 17 | Loch-Wilkinson17 2015 | Female | 39 | Right | — | — | — |

| 18 | Gaunt et al.18 2016 | Female | 58 | Left | No | Yes | No |

| 19 | Khan et al.19 2017 | Male | 65 | Right | — | — | — |

TN, trigeminal neuralgia.

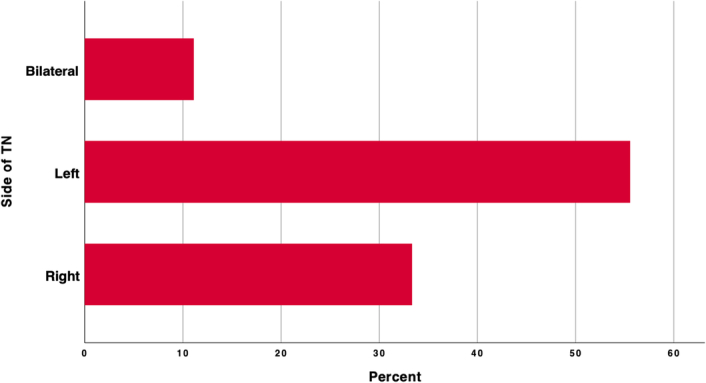

Solo Maxillary division emerged as the most frequent division affected in 6 patients (31.6%), solo mandibular TN (V3) in 2 patients (10.5%) solo ophthalmic TN (V1 TN) in one patient (5.3%). Analyzing combined division affection; 4 patients (21.1%) complaint of V2 TN and V3 TN; two patients complaint of all divisions’ neuralgia (Fig. 3). More than half of the patients [10; (52.6%)] had the symptoms on the left side, two of them had bigger left tonsils. Six patients (31.6%) had the symptoms on the right side, while 2 patients (10.5%) had the symptoms bilaterally, one patient with unknown side (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Showing the distribution of the affected divisions of the trigeminal nerve.

Figure 4.

Showing the affected side of the TN. TN, trigeminal neuralgia.

Other clinical presentations include tingling hand, arm hyposthesia, paresthesia and weakness, and tendon hyperreflexia that occurred in 4 patients (21.1%), denied in 6 patients (31.6%) and unknown in 9 patients (47.4%). Other clinical presentations in the lower limb include hyposthesia, paresthesia and hypo or hyperreflexia in 3 patients (15.8%), denied in 6 patients (31.6%) and unknown in 10 patients (52.6%). Symptoms in the region of the head and neck other than the neuralgia like sluggish or lost ipsilateral corneal reflex, neck Stiffness, blurred vision, vocal cord dysfunction, headaches and retro-orbital pain were founded in 7 patients (36.8%), denied in 6 patients (31.6%), unknown in 6 patients (31.6%). Other reactive autonomic reactions like ipsilateral lacrimation and conjunctival injection and absent gag reflex were reported from 4 patients (21.1%), not found in 6 patients (31.6%), unknown in 9 patients (47,4%).

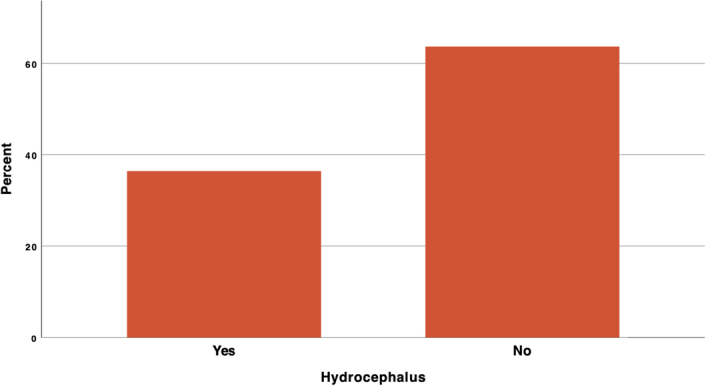

The radiological findings showed that 2 patients (15.8%) with larger left tonsils experienced symptoms on the left side. One patient with a basilar impression and three patients with syrinx. Interestingly, one case was found where a vascular loop crossing over the upper part of the trigeminal ganglion and subsequently the V2 division was affected solo. Only 4 cases (21.1%) showed radiographic evidence of hydrocephalus (Fig. 5). The medulla oblongata was compressed in 6 patients (31.6%), the cervical spinal cord showed abnormalities in 3 patients (15.8%); one cervical myelocele (5.26%), two cervical syringomyelia (10.53%) while 5 patients (26.3%) showed normal findings. The skull bones in 4 patients (21.1%) showed deformity in the form of small posterior fossa or platybasia. The tentorium slope was increased in 2 patients (10.5%).

Figure 5.

Showing the prevalence of hydrocephalus in the documented radiological findings.

The conservative treatment for the TN in patients with CMI was multidisciplinary; 4 patients (21.1%) were treated with muscle relaxant, 3 patients (15.8%) with NSAIDs. We then analyzed the anticonvulsants used; 6 patients (31.6%) received Carbamazepine; other 6 patients (31.6%) received Carbamazepine and Gabapentine; one patient (5.3%) received Carbamazepine and Oxcarbazepine, while three patients weren’t treated with anticonvulsant. Notably, conservative treatment with various modalities was only conducted in 5 patients, and it brought improvement in all of them at the time of discharge.

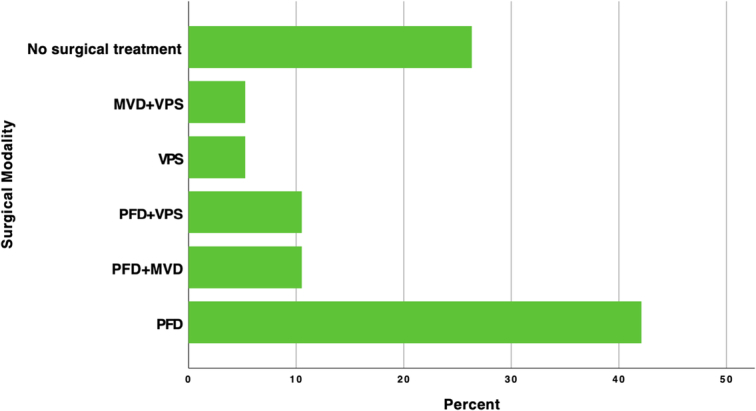

The surgical treatment was conducted in 14 patients (73.7%); 8 patients (42.1%) had only PFD; one patient (5.3%) had only ventriculoperitoneal shunt (VPS); two patients (10.5%) had PFD and VPS; two patients (10.5%) had PFD and microvascular decompression (MVD); one patient (5.3%) had MVD and VPS. Five patients (26.3%) didn’t have surgical intervention. The treatment modalities are presented in (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Showing the surgical modalities used among the patients. MVD, microvascular decompression; PFD, posterior fossa decompression; VPS, ventriculoperitoneal shunt.

After excluding the cases with unknown TN distribution, the overall treatment effect by the time of discharge was significant (P=0.01); conservative treatment; the PFD or VPS as a mono surgical modality; PFD plus MVD or PFD plus VPS as dual surgical modality showed better results than expected, however, the MVD plus VPS as dual surgical modality were less effectiveness at the time of discharge. For V2 distribution (the majority of the cases), patients got the highest profit from the PFD + MVD dual surgical modality, while the PFD alone was less effective than expected (P=0.017). The same with the MVD plus VPS dual surgical modality, they were less effective than expected.

Discussion

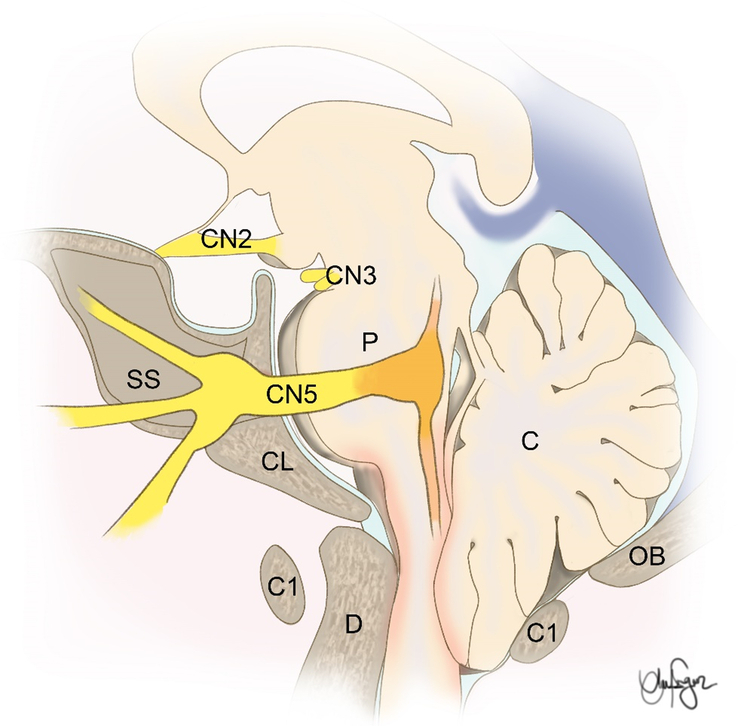

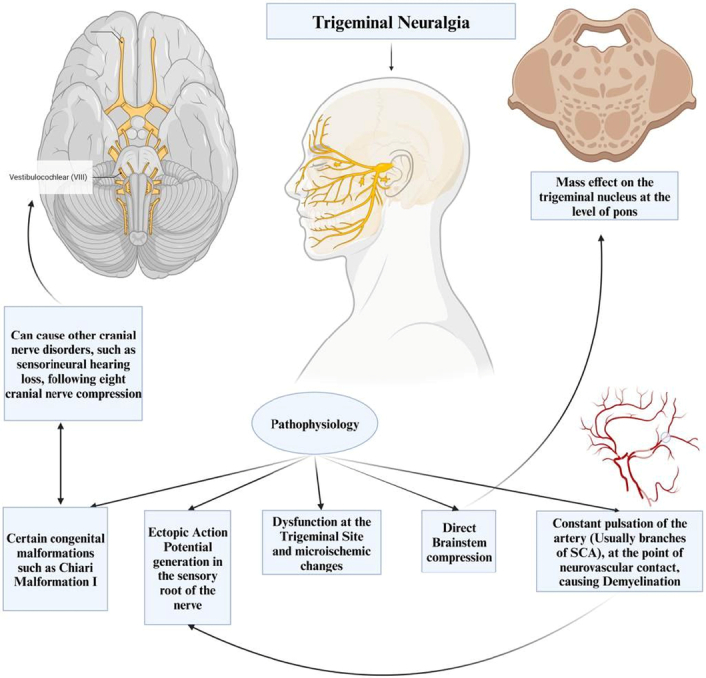

TN stands as the most common paroxysmal facial pain syndrome characterized by distinctive pain distribution patterns and specific triggers6,7,11. Typically, TN’s pain distribution is unilateral and follows the sensory pathways of the trigeminal nerve branches. However, the precise pathophysiological mechanism responsible for TN remains elusive. It’s believed that part of TN’s origin may be attributed to demyelination at the point where neurovascular contact occurs, usually at the branches of the superior cerebellar artery. This demyelination is thought to result from the constant pulsation of the artery11 (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

An anatomical illustration showing the relation of CMI and the trigeminal nerve. C, cerebellum; CL, clivus; D, dens; OB, occipital bone; P, pons; SS, sphenoid sinus.

Additionally, other theories have been put forth. Some suggest dysfunction at the trigeminal site itself, while others propose an ectopic action potential generation in the sensory root of the nerve7. CMI, a congenital mismatch between a small posterior fossa and a normal hindbrain, has been linked to TN24. This malformation can be associated with several cranial nerve disorders, such as TN and sensorineural hearing loss due to eighth nerve compression24,25 (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Showing the pathophysiology of the trigeminal neuralgia.

There is still no clear understanding of the exact mechanism connecting CMI with TN. According to Papanastassiou and colleagues, four potential mechanisms have been suggested. First, TN symptoms could be induced by vascular compression at the nerve root entry zone, influenced by factors like hydrocephalus or anatomical aspects related to CMI. It is reported that a smaller than usual cistern on the affected side, with a steep tentorial angle and a tilted cerebellar tentorium, may result in closer nerve–vessel contact. It has been observed that patients with TN often have small CPA cisternae and/or a crowded posterior fossa16.

Second, it might lead to the stretching of the trigeminal nerve, resulting in demyelination. Third, micro-ischemic changes could play a role. Lastly, direct brainstem compression may result in TN symptoms11. Liu and colleagues reported a patient with ipsilateral TN and HFS secondary to Chiari’s I malformation associated with hydrocephalus and all presenting symptoms improved after shunting favoring the theory of hydrocephalus-induced stretching of the trigeminal nerve26.

Among these, the first two hypotheses appear particularly compelling, as they align with consistent data from various studies showing that TN often results from vascular compression and subsequent demyelination at the trigeminal nerve root entry zone27–29. Similarly, demyelination in the nerve root entry zone is observed in nerve root samples from multiple sclerosis patients with TN. This evidence supports the idea that nerve root entry zone demyelination and the resulting ectopic generation of spontaneous electrical impulses with ephaptic conduction to adjacent axons may be a common mechanism underlying TN30–34.

However, it’s essential to note that while constructive interference in steady-state (CISS) images may show the close relation of the superior cerebellar artery to the trigeminal nerve, there are no histopathological reports confirming that CMI directly leads to stretching or demyelination of the trigeminal nerve. The third proposed mechanism involves micro-ischemic changes, while plausible, lacks direct supporting evidence. Other cases indicate that central lesions or ischemic events can also lead to TN35–39.

The trigeminal nucleus is divided into three parts: the mesencephalic trigeminal nucleus, the main trigeminal nucleus, and the spinal trigeminal nucleus. Fibers forming the spinal tract of the trigeminal nucleus, descend until the C2 level. Because of their poor myelination, they are very susceptible to compression at the foramen magnum in cases of CMI2,4. When it comes to the fourth hypothesis, histologic changes in the trigeminal nucleus may be seen when CMI exerts a mass effect on the brainstem. However, no postmortem studies on patients with TN or CMI have been conducted. Additionally, limited information is available on microscopic parenchymal findings in CMI20,40. Parenchymal findings associated with syringomyelia, often showing vascular dysfunction and fibrosis, have been reported, but the exact relationship to TN in CMI remains unclear40. Whether brainstem compression contributes through demyelination or cellular effects remains uncertain, although increased excitation and decreased inhibition of the trigeminal nuclear complex are considered potential factors in TN41. Autopsy of a patient with TN in the context of CMI showed an elongated medulla oblongata with right side flattening from tonsillar herniation with left medullary atrophy associated with a pronounced reduction in the size of trigeminal nuclei11.

Reports in English, French, and Spanish languages have mentioned cases of TN or facial pain linked to CMI, with19 cases summarized in (Tables 1, 2, 3, 4). According to Chakraborty et al. 5, there were only two cases where neurologic symptoms were not detected during operation. Similarly, in this study, seven patients presented without any symptoms or signs (Tables 1, 2). The situation becomes complex when a patient with CMI develops hydrocephalus. In such cases, the neurosurgeon must determine the cause and consequence. This study reported four cases complicated by hydrocephalus (Table 3). It is likely that hydrocephalus can benefit from treatment, as seen in cases where reducing the mass effect caused the tonsils to ascend42.

Table 2.

Showing the other symptoms, its duration and the possible risk factors

| No. | Author | Head and neck | Upper limb | Lower limb | Autonomic | Cerebellar symptoms | Duration of symptoms in years | Risk factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jose Alberto1 1982 | No | No | No | No | No | — | No |

| 2 | Ayuso-Peralta et al.2 1999 | No | No | No | No | No | — | No |

| 3 | V Iváñez3 1999 | Rluggish ispilateral corneal reflex | — | — | — | — | 31 | No |

| 4 | Rosetti et al.4 1999 | — | Decreased in left, loss of reflexes | Decreased in left, loss of reflexes | — | 19 | Previous history of left paroxymal in the V2 | |

| 5 | Chakraborty et al.5 2003 | Neck stiffness | — | — | — | — | 2 | No |

| 6 | Gnanalingham et al.6 2004 | No | No | No | No | — | 1/2 | No |

| 7 | Teo et al.7 2005 | — | Hand Tingling | — | — | — | 3 | No |

| 8 | Monzillo et al.8 2007 | — | — | — | Ipsilateral tearing and conjunctival injection | — | 4 | No |

| 9 | Dahdaleh9 2008 | Blurred vision facial hypothesia vocal cord dysfunction |

Hyperreflexic deep tendon reflexes | Hyperreflexic deep tendon reflexes | Absent Gag reflex | — | 1/4, | No |

| 10 | Caranci et al.10 2008 | — | — | lacrimation | — | 3 | No | |

| 11 | Papanastassiou11 2008 | — | — | — | — | — | No | |

| 12 | Panconesi12 2009 | Headache | — | — | Ipsilateral conjunctival injection and tearing | — | — | No |

| 13 | Vince et al.13 2010 | Suboccipital headaches, Retro-orbital pain | Weakness and paresthesia of both arms | — | Gait | 10 | No | |

| 14 | Than et al.14 2011 | No | No | No | No | — | 5 | Previous history of TN |

| 15 | Gomez-Camello15 2013 | No | No | No | No | No | 5 | No |

| 16 | Liu et al.16 2014 | Headache | — | — | — | 5 | No | |

| 17 | Loch-Wilkinson17 2015 | No | No | No | No | — | — | No |

| 18 | Gaunt et al.18 2016 | — | — | Progressive paresthesia in her lower limbs, | — | — | — | No |

| 19 | Khan et al.19 2017 | Loss of corneal reflex on the right side | — | — | — | Gait | 10 | No |

TN, trigeminal neuralgia.

Table 3.

Showing the radiological findings for each case

| No. | Author | Herniation of cerebellar tonsills (mm) | Basilar impression | Syrinx | Vascular Kompression on CN V | Hydrocephalus | CSF spaces | Spinal cord | Skull deformity | Increased tentorium slope |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jose Alberto1 1982 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | — | — | — | — |

| 2 | Ayuso-Peralta et al.2 1999 | Yes | No | No | No | No | — | — | — | — |

| 3 | V Iváñez3 1999 | Yes | No | No | No | — | — | Medullar descent | — | — |

| 4 | Rosetti et al.4 1999 | Left tonsil > right | No | No | No | — | — | Cervical myelocele | — | — |

| 5 | Chakraborty et al.5 2003 | Left tonsil > right | No | No | No | No | — | No | No | — |

| 6 | Gnanalingham et al.6 2004 | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Lateral and third Ventriculomegaly | Medulla Kink | Platybasia, small post, fossa | — |

| 7 | Teo et al.7 2005 | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Triventriculomegaly | — | — | — |

| 8 | Monzillo et al.8 2007 | Yes | No | No | No | — | — | Cervical Syringomyelia from the C2 downwards | — | — |

| 9 | Dahdaleh9 2008 | 10 mm | No | No | No | No | — | No | No | No |

| 10 | Caranci et al.10 2008 | 20 mm | No | No | No | No | — | No | No | No |

| 11 | Papanastassiou11 2008 | No | No | C1–C3 | Vessel contacting the V. SCA superior to the trigeminal nerve |

— | — | Compression of medulla | — | — |

| 12 | Panconesi12 2009 | No | No | No | No | — | — | — | Small post fossa | Yes |

| 13 | Vince et al.13 2010 | No | No | No | No | Yes | 4th Vent elongation, narrow Subarachnoidal Space | Medulla Kink | — | Yes |

| 14 | Than et al.14 2011 | 20 mm | No | Cervical | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 15 | Gomez-Camello15 2013 | Yes | No | No | No | — | — | Hydromyelia | — | — |

| 16 | Liu et al.16 2014 | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Lateral and third Ventriculomegaly | — | Platybasia | — |

| 17 | Loch-Wilkinson17 2015 | Yes | No | No | No | — | Tight arachnoid bands | Tented gliotic Medulla | — | — |

| 18 | Gaunt et al.18 2016 | 25 mm | No | No | No | — | — | Medulla and Pons compression | Small post fossa | — |

| 19 | Khan et al.19 2017 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; SCA, superior superior cerebellar artery.

Table 4.

showing the treatment modalities used, postoperative complications, outcome at discharge and follow-up and the total duration of follow-up

| No. | Author | Muscle relaxant | NSAIDs | Anticonvulsant | PFD | MVD | VP-shunt | Others | PostOP complications | Outcome at discharge | Outcome at follow-up | Follow-up (month) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jose Alberto1 1982 | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Improved | — | — |

| 2 | Ayuso-Peralta et al.2 1999 | Yes | — | — | No | No | No | No | No | Improved | Improved | 12 |

| 3 | V Iváñez3 1999 | — | — | Carbamazepine | No | No | No | No | No | Improved | — | — |

| 4 | Rosetti et al.4 1999 | — | — | Carbamezipine, Gabapentine | Yes | Yes | No | Thermocoagulation of V ganglion | No | Improved | Improved | 18 |

| 5 | Chakraborty et al.5 2003 | Baclofen | — | Carbamezipine, Gabapentine | Yes | No | No | No | No | Improved | — | — |

| 6 | Gnanalingham et al.6 2004 | — | — | Carbamezipine | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Improved | Imporved | 3 |

| 7 | Teo et al.7 2005 | — | — | Carbamezipine, Gabapentine | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Improved | Imporved | 3 |

| 8 | Monzillo et al.8 2007 | — | Indomethacin | Carbamezipine | No | No | No | No | No | Improved | Imporved | — |

| 9 | Dahdaleh9 2008 | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Improved | Improved | 2 |

| 10 | Caranci et al.10 2008 | — | Nimesulide, Ibuprofen, Indomethacin | Carbamezipine | Yes | No | No | No | No | Improved | — | — |

| 11 | Papanastassiou11 2008 | — | — | Carbamezipine | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Improved | Improved | 10 |

| 12 | Panconesi12 2009 | — | — | Carbamezipine, Gabapentine | No | No | No | No | No | Improved | — | — |

| 13 | Vince et al.13 2010 | Refractory | Refractory | Refractory | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | — | — | 36 |

| 14 | Than et al.14 2011 | — | — | Carbamezipine, Oxcarbazepine | Yes | No | No | No | No | Improved | Improved | 9 |

| 15 | Gomez-Camello15 2013 | Yes | — | — | Yes | No | No | No | No | Improved | — | — |

| 16 | Liu et al.16 2014 | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Improved | Improved | 14 |

| 17 | Loch-Wilkinson17 2015 | — | Yes | Carbamezipine, Gabapentine | Yes | No | No | No | No | Improved | Imporved | 12 |

| 18 | Gaunt et al.18 2016 | — | — | Carbamezipine | No | No | No | No | No | Improved | Improved | — |

| 19 | Khan et al.19 2017 | — | — | Carbamezipine, Gabapentine | Yes | No | No | No | — | — | — | — |

MVD, microvascular decompression; OP, operative; PFD, posterior fossa decompression; VP, ventriculoperitoneal.

Diagnostic measures for TN include T2-weighted images and high-resolution 3D-CISS sequences to identify vascular loops near the trigeminal root entry zone and assess the region of neurovascular conflict7,11. Initially, non-structural TN is treated with medical therapy, with carbamazepine being the first-line choice. However, the indication for surgery is refractory primary TN or the presence of symptomatic mass lesion, termed secondary TN from central nervous system lesions43.

Ventriculoperitoneal shunting may also resolve acquired CM related to lumbo-peritoneal shunting44. Structural factors like a narrow cerebello-pontine angle and flattening of the skull base (platybasia) can lead to direct compression of the trigeminal nucleus. Platybasia, combined with basilar impression, results in a narrowing of the posterior fossa, which can compress vascular structures and nerves7. This study showed two patients with platybasia (Table 3), one of whom had severe facial pain and ipsilateral face tics with headache16.

A causal relationship between CMI-associated cervical syrinx and TN has been suggested, as the excitability of sensory fibers from the trigeminal nucleus may be enhanced by the presence of a syrinx. Three patients presented with syrinx, with two having TN and one with an unknown status. The relevance of this association becomes evident when syrinx is present. Two previous reports have identified a syrinx in cases of TN and CMI4,45.

In summary, treatment modalities for TN associated with CMI encompass conservative approaches that modulate nerve excitability and manage symptoms, as well as surgical interventions directly targeting structural abnormalities and relieving trigeminal nerve compression17,46. These methods aim to provide relief from the debilitating pain associated with this complex condition. Conservative treatment primarily involves medications, with carbamazepine as the commonest first-line choice47,48. This approach works by dampening excessive neuronal firing in the trigeminal nerve, stabilizing sodium channels in nerve cell membranes, and reducing the likelihood of abnormal electrical impulses responsible for the sharp, paroxysmal pains characteristic of TN49. In some studies, the trigeminal nerve showed abnormal expression of the voltage-gated sodium channels50. While conservative treatment is effective for many patients, those with refractory symptoms or clear structural causes, like CMI, may require invasive interventions51,52.

Surgical treatments for TN associated with CMI include VPS, PFD, and MVD53. VP shunting is essential when hydrocephalus complicates CMI, contributing to TN. This procedure alleviates intracranial pressure, and reduces the mass effect caused by cerebellar tonsillar herniation54. PFD addresses anatomical abnormalities linked to CMI, primarily by creating more space within the posterior fossa. This intervention releases pressure on the cerebellar tonsils, reducing compression on nearby structures, such as the trigeminal nerve. MVD, in turn, targets vascular compression of the trigeminal nerve, often due to pulsating blood vessels like the superior cerebellar artery55,56. It separates the offending blood vessel from the nerve, eliminating mechanical irritation caused by pulsations and ultimately relieving TN pain.

Our results emphasize the significance of personalized treatment for TN based on the specific division of the trigeminal nerve involved (V1, V2, or V3)57–60. Each division innervates distinct facial areas, and the choice of treatment should reflect the primary source of the patient’s pain. Moreover, tailoring the treatment to a specific division helps determine the underlying cause of TN—whether it is vascular compression, structural abnormalities, or unique factors related to that division. For instance, MVD is ideal for V1 vascular compression, while PFD or alternative techniques may better address structural issues in V2 or V3. Recognizing the division involved facilitates a customized treatment plan, minimizing unnecessary procedures and side effects, and underscores the value of personalized medicine in managing TN within CMI patients, highlighting the importance of a thorough diagnostic approach to optimize patient outcomes.

Limitations

This systematic review provides valuable insights into the relationship between CMI and TN. However, it is essential to acknowledge several limitations within this study. First, the relatively small number of identified cases19 from the existing literature may limit the generalizability of our findings. The rarity of this specific condition and the scarcity of comprehensive data may have restricted the depth of our analysis. Data describing morphometric and volumetric features of the posterior fossa, CPA and the pontine cisternae are not recorded in most of these cases, which undermine our understanding of the pathophysiologic involved mechanism. The absence of robust experimental studies that uncover the pathophysiological mechanisms of the association of CMI with TN makes our understanding defective.

Second, there is inherent heterogeneity in the clinical presentations, treatments, and outcomes among the cases included in this review. Variations in diagnostic criteria, surgical approaches, and the duration of follow-up for patients could potentially introduce bias and hinder our ability to draw firm conclusions. The absence of a large sample size case series impairs the generalizability of the results and complicates data heterogeneity.

Matching cohort and case series designated for comparing both CMI-associated TN and isolated TN should be recruited to get robust comprehensive evidence-based data. Matching cohort and case series designated for comparing both CMI-associated TN and isolated TN should be recruited to get robust comprehensive evidence-based data.

Conclusion

In summary, this systematic review highlights the significant impact of CMI on TN, revealing the potential role of this complex condition in both the occurrence and severity of TN. CMI, characterized by the herniation of cerebellar tonsils into the cervical canal, presents a diverse clinical spectrum, ranging from asymptomatic cases to severe cranial nerve dysfunction. Within this spectrum, TN emerges as a notable symptom associated with CMI. The study underscores the critical importance of considering CMI as a potential underlying cause of TN in clinical practice.

Furthermore, the findings highlight the effectiveness of diverse management strategies for CMI, such as MVD, PFD and VPS, in serving as potential treatments for TN. While conservative treatment involving medications, primarily carbamazepine, proves effective for many patients, surgical interventions exhibit varying degrees of success. Notably, the combination of PFD and MVD stands out as a promising dual surgical modality, particularly for TN cases associated with CMI, especially in instances with V2 distribution. Although this study has limitations, including a relatively small number of identified cases, inherent clinical heterogeneity, and the absence of a control group, it underscores the importance of further research and the accumulation of more cases and long-term outcomes. Enhanced comprehension of the intricate relationship between CMI and TN can pave the way for more precise diagnostic and treatment strategies, ultimately enhancing the quality of life for affected individuals and mitigating their suffering. The results of this review contribute significantly to the growing body of knowledge surrounding this complex medical condition and lay the groundwork for future investigations into this challenging and multifaceted issue.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent

Consent to participate: As this is a narrative review and no original data from new patients were collected, consent to participate is not applicable.

Consent for publication: As this is a narrative review and no original data from new patients were collected, consent for publication is not applicable.

Source of funding

Not applicable.

Author contribution

All authors have contributed equally in formation of all forms of manuscript.

Conflicts of interest disclosure

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Research registration unique identifying number (UIN)

Not applicable.

Guarantor

Bipin Chaurasia.

Data availability statement

Not applicable.

Provenance and peer review

Okay.

Footnotes

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

Published online 4 September 2024

Contributor Information

Amr Badary, Email: amr.badary@hotmail.com.

Yasser F. Almealawy, Email: almealawyyasser@gmail.com.

William A. Florez-Perdomo, Email: Williamflorezmd@gmail.com.

Vivek Sanker, Email: viveksanker@gmail.com.

Wireko Andrew Awuah, Email: andyvans36@yahoo.com.

Toufik Abdul-Rahman, Email: Drakelin24@gmail.com.

Arwa Salam Alabide, Email: arwa1999salam@gmail.com.

Sura N. Alrubaye, Email: Surarubaiee22@gmail.com.

Aalaa Saleh, Email: aalaasaleh.16@gmail.com.

Anil Ergen, Email: anilergen@gmail.com.

Bipin Chaurasia, Email: trozexa@gmail.com.

Mohammed A. Azab, Email: mohammed.azab@kasralainy.edu.eg.

Oday Atallah, Email: atallah.oday@mh-hannover.de.

References

- 1.da Silva JA, da Silva EB. Basilar impression as a cause of trigeminal neuralgia: report of a case. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 1982;40:165–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ayuso-Peralta L, Jiménez-Jiménez FJ, Tejeiro J, et al. Trigeminal neuralgia associated with Arnold Chiari malformation. Rev Neurol, 29:1345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iváñez V, Moreno M. Trigeminal neuralgia in children as the only manifestation of Chiari I malformation. Rev Neurol, 28:485–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosetti P, Oulad Ben Taib N, Brotchi J, et al. Arnold Chiari Type I malformation presenting as a trigeminal neuralgia: case report. Neurosurgery 1999;44:1122–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chakraborty A, Bavetta S, Leach J, et al. Trigeminal neuralgia presenting as Chiari I malformation. Minim Invasive Neurosurg 2003;46:47–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gnanalingham K, Joshi SM, Lopez B, et al. Trigeminal neuralgia secondary to Chiari’s malformation-treatment with ventriculoperitoneal shunt. Surg Neurol 2005;63:586–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teo C, Nakaji P, Serisier D, et al. Resolution of trigeminal neuralgia following third ventriculostomy for hydrocephalus associated with Chiari I malformation: case report. Minim Invasive Neurosurg 2005;48:302–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monzillo P, Nemoto P, Costa A, et al. Paroxysmal hemicrania-tic and Chiari I malformation: an unusual association. Cephalalgia 2007;27:1408–1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dahdaleh NS, Menezes AH. Incomplete lateral medullary syndrome in a patient with Chiari malformation Type I presenting with combined trigeminal and vagal nerve dysfunction. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2008;2:250–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caranci G, Mercurio A, Altieri M, et al. Trigeminal neuralgia as the sole manifestation of an Arnold-Chiari type I malformation: case report. Headache 2008;48:625–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Papanastassiou AM, Schwartz RB, Friedlander RM. Chiari I malformation as a cause of trigeminal neuralgia: case report. Neurosurgery 2008. ;63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Panconesi A, Bartolozzi ML, Guidi L. SUNCT syndrome or first division trigeminal neuralgia associated with cerebellar hypoplasia. J Headache Pain 2009;10:461–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vince GH, Bendszus M, Westermaier T, et al. Bilateral trigeminal neuralgia associated with Chiari’s type I malformation. Br J Neurosurg 2010;24:474–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Than KD, Sharifpour M, Wang AC, et al. Chiari I malformation manifesting as bilateral trigeminal neuralgia: case report and review of the literature. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2011;82:1058–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gómez-Camello Á, Pelegrina-Molina J. Trigeminal neuralgia associated to Chiari type I malformation: resolution following suboccipital decompression. Rev Neurol 2013;56:398–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu J, Yuan Y, Zang L, et al. Hemifacial spasm and trigeminal neuralgia in Chiari’s I malformation with hydrocephalus: case report and literature review. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2014;122:64–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loch-Wilkinson T, Tsimiklis C, Santoreneos S. Trigeminal neuralgia associated with Chiari 1 malformation: symptom resolution following craniocervical decompression and duroplasty: Case report and review of the literature. Surg Neurol Int 2015;6(suppl 11):S327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaunt T, Aboelmagd S, Spohr H, et al. Spontaneous regression of a chiari malformation type 1 in a 58-year-old female. BJR Case Rep 2016;2:20160016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khan M, Nishi SE, Hassan SN, et al. Trigeminal neuralgia, glossopharyngeal neuralgia, and myofascial pain dysfunction syndrome: an update. Pain Res Manag 2017;2017:7438326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beuls EAM, Vandersteen MAM, Vanormelingen LM, et al. Deformation of the cervicomedullary junction and spinal cord in a surgically treated adult Chiari I hindbrain hernia associated with syringomyelia: a magnetic resonance microscopic and neuropathological study. Case report J Neurosurg 1996;85:701–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stevens JM, Serva WAD, Kendall BE, et al. Chiari malformation in adults: relation of morphological aspects to clinical features and operative outcome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1993;56:1072–1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenlee JDW, Menezes AH, Bertoglio BA, et al. Syringobulbia in a pediatric population. Neurosurgery 2005;57:1147–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gronseth G, Cruccu G, Alksne J, et al. Practice parameter: the diagnostic evaluation and treatment of trigeminal neuralgia (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the European Federation of Neurological Societies. Neurology 2008;71:1183–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Milhorat TH, Chou MW, Trinidad EM, et al. Chiari I malformation redefined: clinical and radiographic findings for 364 symptomatic patients. Neurosurgery 1999;44:1005–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parker EC, Teo C, Rahman S, et al. Complete resolution of hypertension after decompression of Chiari I malformation. Skull Base Surg 2000;10:149–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rasche D, Kress B, Stippich C, et al. Volumetric measurement of the pontomesencephalic cistern in patients with trigeminal neuralgia and healthy controls. Neurosurgery 2006;59:614–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haines SJ, Jannetta PJ, Zorub DS. Microvascular relations of the trigeminal nerve. An anatomical study with clinical correlation. J Neurosurg 1980;52:381–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamlyn PJ, King TT. Neurovascular compression in trigeminal neuralgia: a clinical and anatomical study. J Neurosurg 1992;76:948–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sindou M, Leston JM, Decullier E, et al. Microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia: the importance of a noncompressive technique—Kaplan-Meier analysis in a consecutive series of 330 patients. Neurosurgery 2008;63(suppl 2):341–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burchiel KJ, Baumann TK. Pathophysiology of trigeminal neuralgia: new evidence from a trigeminal ganglion intraoperative microneurographic recording. Case report J Neurosurg 2004;101:872–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rasminsky M. Ectopic generation of impulses and cross-talk in spinal nerve roots of “dystrophic” mice. Ann Neurol 1978;3:351–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harry Rappaport Z, Govrin-Lippmann R, Devor M. An electron-microscopic analysis of biopsy samples of the trigeminal root taken during microvascular decompressive surgery. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg 1997;68(1-4 Pt 1):182–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Devor M, Govrin-Lippmann R, Rappaport ZH. Mechanism of trigeminal neuralgia: an ultrastructural analysis of trigeminal root specimens obtained during microvascular decompression surgery. J Neurosurg 2002;96:532–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Love S, Coakham HB. Trigeminal neuralgia: pathology and pathogenesis. Brain 2001;124(Pt 12):2347–2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Golby AJ, Norbash A, Silverberg GD. Trigeminal neuralgia resulting from infarction of the root entry zone of the trigeminal nerve: case report. Neurosurgery 1998;43:620–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim JS, Kang JH, Lee MC. Trigeminal neuralgia after pontine infarction. Neurology 1998;51:1511–1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nagata K, Nikaido Y, Yuasa T, et al. Trigeminal neuralgia associated with venous angioma-case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1995;35:310–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peker S, Akansel G, Sun I, et al. Trigeminal neuralgia due to pontine infarction. Headache 2004;44:1043–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Balestrino M, Leandri M. Trigeminal neuralgia in pontine ischaemia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1997;62:297–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rusbridge C, Greitz D, Iskandar BJ. Syringomyelia: current concepts in pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. J Vet Intern Med 2006;20:469–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fromm GH, Terrence CF, Maroon JC. Trigeminal neuralgia. Current concepts regarding etiology and pathogenesis. Arch Neurol 1984;41:1204–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee M, Rezai AR, Wisoff JH. Acquired Chiari-I malformation and hydromyelia secondary to a giant craniopharyngioma. Pediatr Neurosurg 1995;22:251–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Merskey H. Classification of chronic pain. Descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms. Prepared by the International Association for the Study of Pain, Subcommittee on Taxonomy. Pain Suppl 1986;3:S1–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Payner TD, Prenger E, Berger TS, et al. Acquired Chiari malformations: incidence, diagnosis, and management. Neurosurgery 1994;34:429–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peñarrocha M, Okeson JP, Peñarrocha MS, et al. Orofacial pain as the sole manifestation of syringobulbia-syringomyelia associated with Arnold-Chiari malformation. J Orofac Pain 2001;15:170–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Punyani SR, Jasuja VR. Trigeminal neuralgia: An insight into the current treatment modalities. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res 2012;2:188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Obermann M. Treatment options in trigeminal neuralgia. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2010;3:107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lynch ME, Watson CPN. The pharmacotherapy of chronic pain: a review. Pain Research & Management. J Canad Pain Soc 2006;11:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gambeta E, Chichorro JG, Zamponi GW, et al. Trigeminal neuralgia: An overview from pathophysiology to pharmacological treatments. Mol Pain 2020;16:1744806920901890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Siqueira SRDT, Alves B, Malpartida HMG, et al. Abnormal expression of voltage-gated sodium channels Nav1.7, Nav1.3 and Nav1.8 in trigeminal neuralgia. Neuroscience 2009;164:573–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Di Stefano G, Truini A, Cruccu G. Current and innovative pharmacological options to treat typical and atypical trigeminal neuralgia. Drugs 2018;78:1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Al-Quliti KW. Update on neuropathic pain treatment for trigeminal neuralgia: the pharmacological and surgical options. Neurosciences 2015;20:107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Deng X, Wu L, Yang C, et al. Surgical treatment of Chiari I malformation with ventricular dilation. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2013;53:847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zakaria R, Kandasamy J, Khan Y, et al. Raised intracranial pressure and hydrocephalus following hindbrain decompression for Chiari I malformation: a case series and review of the literature. Br J Neurosurg 2012;26:476–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eppelheimer MS, Nwotchouang BST, Pahlavian SH, et al. Cerebellar and brainstem displacement measured with DENSE MRI in Chiari Malformation following posterior fossa decompression surgery. Radiology 2021;301:187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fischer EG. Posterior fossa decompression for Chiari I deformity, including resection of the cerebellar tonsils. Childs Nerv Syst 1995;11:625–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhao Y, Zhang X, Yao J, et al. Microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia due to venous compression alone. J Craniofac Surg 2018;29:178–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang W, Yu F, Kwok SC, et al. Microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia caused by venous offending on the ventral side of the root entrance/exit zone: classification and management strategy. Front Neurol 2022;13:864061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Atallah O, Chaurasia B. Chiari malformation type II and myelomeningocele repair. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2023;32:752–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Atallah O, Wireko AA, Chaurasia B. Respiratory arrest after posterior fossa decompression in patients with Chiari malformations: an overview. J Craniovertebr Junct Spine 2023;14:217–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.