Abstract

Ecosystem restoration interventions often utilize visible elements to restore an ecosystem (e.g. replanting native plant communities and reintroducing lost species). However, using acoustic stimulation to help restore ecosystems and promote plant growth has received little attention. Our study aimed to assess the effect of acoustic stimulation on the growth rate and sporulation of the plant growth-promoting fungus Trichoderma harzianum Rifai, 1969. We played a monotone acoustic stimulus (80 dB sound pressure level (SPL) at a peak frequency of 8 kHz and a bandwidth at −10 dB from the peak of 6819 Hz—parameters determined via review and pilot research) over 5 days to T. harzianum to assess whether acoustic stimulation affected the growth rate and sporulation of this fungus (control samples received only ambient sound stimulation less than 30 dB). We show that the acoustic stimulation treatments resulted in increased fungal biomass and enhanced T. harzianum conidia (spore) activity compared to controls. These results indicate that acoustic stimulation influences plant growth-promoting fungal growth and potentially facilitates their functioning (e.g. stimulating sporulation). The mechanism responsible for this phenomenon may be fungal mechanoreceptor stimulation and/or potentially a piezoelectric effect; however, further research is required to confirm this hypothesis. Our novel study highlights the potential of acoustic stimulation to alter important fungal attributes, which could, with further development, be harnessed to aid ecosystem restoration and sustainable agriculture.

Keywords: ecoacoustics, acoustic restoration, fungi, plant growth-promoting fungi, sonic restoration, soil health

1. Introduction

Ecosystem restoration is imperative in the face of escalating degradation and global biodiversity loss [1]. Efforts to restore ecosystems often focus on physical and visible interventions, such as revegetation [2], species reintroductions [3] and, more recently, microbial inoculations [4]. Moreover, global food systems are under threat from widespread land degradation [5]. Developing tools to promote ecosystem recovery and sustainable agriculture is imperative. While the more traditional and tangible approaches are crucial for ecosystem recovery, it is also vital to apply lateral thinking and explore alternative approaches. To this end, there remains a notable gap in our understanding of how acoustic domains could promote healthy ecosystems. The rising recognition of the importance of acoustic domains in ecosystems [6] invites questions about whether acoustic stimulation—the application of sound to a particular ecological receptor—could promote features that benefit ecological and food systems.

Ecological acoustic surveys or ‘ecoacoustics’ have proven successful at monitoring soil biodiversity [7], which is a vital but challenging-to-monitor ecosystem component. Recently, Robinson et al. [8] demonstrated that it is possible to record soniferous species below ground using piezoelectric microphones and audio recording devices in a restoration context. The authors built acoustic indices of audible soil diversity, complexity and normalized differential signals that reflected the recovery of soil biodiversity in a temperate forest context. Moreover, Görres & Chesmore [9] used similar acoustic technology to detect scarab beetle larvae stridulation in a soil pest monitoring setting.

However, the role of acoustic stimulation in fostering ecosystem recovery and sustainable food systems remains underexplored. The emerging field of ‘acoustic restoration’ aims to broadcast soundscapes in disturbed areas to facilitate the recolonization of animals, microorganisms and/or biogenic compounds [10]. For instance, McAfee et al. [11] enriched marine soundscapes to enhance recruitment and habitat building on oyster reefs. They deployed low-cost marine speakers at four sites and compared oyster recruitment rates. The authors found that soundscape playback significantly increased oyster recruitment at 8 of the 10 study sites.

Sound is a fundamental aspect of the environment and holds immense potential to influence ecological processes and shape ecosystem dynamics [12,13]. Similarly, anthropogenic sounds (often classed as ‘noise’ if the sound has detrimental effects) can alter ecosystem dynamics [14]. However, the impact of sound stimulation on the growth rate and activity of microbiota has received little attention. According to a recent review [15], studies have shown that acoustic stimulation using monotonous anthropogenic sound can change the community composition, growth rate and biomass of lab-grown bacteria [16], algae [17] and pathogenic fungi [18]. The mechanisms to explain how sound could stimulate microbial activity may be through a piezoelectric effect, whereby a mechanical pressure (i.e. an acoustic wave) is converted into a voltage, as seen in viruses, peptides, amino acids and proteins [19] or more likely via mechanoreceptors in microbiota converting mechanical stimuli (e.g. sound) into biochemical signals within the organism [20]. However, there have been no studies on the effect of anthropogenic sound exposure on the activity of plant growth-promoting microbiota.

This knowledge gap presents an opportunity to explore the relationship between acoustic stimulation and functional ecological components (beneficial microbiota). Microorganisms, including fungi, bacteria, viruses and others, drive fundamental ecosystem processes including plant immunoregulation and growth and nutrient cycling [21]. Investigating the potential effects of acoustic stimulation on the plant growth-promoting activity of microbiota could provide valuable insights that can eventually aid ecosystem recovery and sustainable agriculture.

We sought to take the first steps in understanding whether certain acoustic parameters could affect plant growth-promoting fungal activity. Specifically, we aimed to assess the effect of acoustic stimulation on the growth rate and sporulation of the plant growth-promoting fungus Trichoderma harzianum. We played a monotone acoustic stimulus over 5 days to T. harzianum (control samples received only ambient sound stimulation less than 30 dB). The acoustic stimulus consisted of continuous band-limited noise, with a peak frequency of 8 kHz and a bandwidth at −10 dB from the peak of 6819 Hz. It was played back at an amplitude of 80 dB SPL as measured at the location of the fungal samples. While we aim to conduct comprehensive follow-up studies with refined acoustic stimulus parameters and detailed microbiomic or metabolomic techniques (e.g. deep sequencing to determine functional responses and molecular mechanisms), the objective of this novel study was to establish the foundations.

2. Methods

(a). Experimental setup

The acoustic stimulation of the plant growth-promoting fungus T. harzianum was done in a lab at Flinders University, South Australia, between December 2023 and January 2024. The lab was kept at a constant 25°C, and the local environment was monitored with a ThermoPro TP50 digital indoor thermometer. We sterilized the lab space using a 1% Virkon solution to prevent contamination. Recording acoustic samples in ambient conditions may capture sounds from variable detection spaces. To address this and create controlled conditions, we built and installed three sterilized sound attenuation chambers (one for storing the sound treatment samples, one for storing the ambient control samples and one for applying sound). The sound attenuation chambers were made from heavy-duty 80-l plastic containers with secure lids and Advanced Acoustics (305 mm) Wedge acoustic studio foam installed on each internal wall of the container using Velcro strips. This set-up was chosen based on our previous testing conducted for another study [8], which assessed the chambers’ ability to reduce ambient sound.

(b). Trichoderma harzianum culture assay

We selected T. harzianum as our focal plant growth-promoting fungus for three reasons: (i) it has several potential beneficial functions that could enhance ecosystem restoration (e.g. P solubilization, ability to synthesize beneficial phytohormones and ability to outcompete plant pathogens) [22–24]; (b) it is not an obligate symbiont and is, therefore, relatively easy to culture; and (c) it produces vivid green conidia (spores) that can enhance the quantification process. We used T. harzianum (Isolate Td22; Organic Crop Protectants) and created a modified potato dextrose agar culture medium with 125 g potato, 15 g dextrose, 10 g baker’s yeast extract and 850 ml of distilled water [25]. The medium was created in aseptic conditions and poured, then set under a laminar flow hood (Lab Systems). We combined 5 g of the T. harzianum per litre of distilled water to create a suspension and homogenized by gently shaking the flask for 30 s. We then used a sterile loop to inoculate the culture medium with T. harzianum in a random order, placing one small circular streak (5 mm diameter) in the centre of the Petri dish (again, under a laminar flow hood). This allowed for efficient mycelium radial growth measurements. The Petri dishes (acoustic stimulation treatment n = 20; control group n = 20) were then sealed with Parafilm and placed into their respective sound attenuation chambers using a digital randomizer.

(c). Acoustic stimulation of Trichoderma harzianum

To facilitate acoustic stimulation, we downloaded (from YouTube) an 8-h video playing a monotonous 8 kHz sound (=Tinnitus Flosser Masker at 8 kHz by Dalesnale). We tested the frequency using a Wildlife Acoustics Echo Meter Touch Pro bat detector (USA), designed to capture high-frequency acoustic signals. We selected 80 dB SPL for our acoustic stimulus based on previous pilot research (electronic supplementary material, figure S1) and a review [15]. The acoustic stimulus consisted of continuous band-limited noise, with a peak frequency of 8 kHz and a bandwidth at −10 dB from the peak of 6819 Hz. It was played back at an amplitude of 80 dB SPL as measured at the location of the fungal samples (the Petri dishes were placed directly on the speaker). We determined the peak frequency in Audacity (v. 3.4.2) by plotting the spectrum with an fast Fourier transform (FFT) size of 1024. This acoustic stimulus was applied to the 20 Petri dishes in the acoustic stimulation treatment group only using a randomized controlled trial design. We randomly selected individual Petri dishes to be stimulated for 30 min each per day so that all 20 dishes received stimulation in a random order. This was repeated over 5 days. We used three sound attenuation chambers: one (chamber 1) to store the acoustic-stimulation treatment group, one (chamber 2) to store the control group (no stimulation) and another (chamber 3) to use for the Petri dishes isolated for stimulation—these were placed directly on a Bluetooth speaker (Anker Soundcore Bluetooth speaker A3102), USA), which was on the base of the chamber facing upwards and connected via Bluetooth to a tablet (Lenovo Tab (M8), China). In other words, only chamber 3 was used for the acoustic treatment (chambers 1 and 2 were for storing the treatment and control group, respectively. These were kept in the same conditions while not being stimulated). To determine the amplitude level in the sound attenuation chambers, we used a Uni-T Professional Meter (TUT352, China) with an amplitude detection range of 30–130 dB and adjusted the tablet sound accordingly. Considering our environment involved playing a monotonous sound in a chamber, we used the fast setting on the Uni-T Professional Meter. The fast setting is more appropriate for capturing stable sound levels in a controlled environment with a consistent sound source, ensuring accurate and responsive measurements. The SPL meter was set to A-weighting.

(d). Trichoderma harzianum radial growth and conidia density quantification

We measured the radial growth of the T. harzianum mycelium in each Petri dish each day using a standard ruler and recorded the diameter at four points to get an average diameter in millimetre. We also used a novel raster analysis approach in Python (v. 3.12.10; described in §2e). To measure T. harzianum conidia (spores) density, we poured 10 ml of distilled water over each Petri dish after 5 days and collected the fungal biomass in 15 ml centrifuge tubes (figure 1a–f). We then filtered out non-target fungal biomass in each sample using a sterilized sieve with a 50 μm pour size (Retsch 41105003 Test sieve) and retained the suspension containing the conidia. These were stored at 4°C. We inoculated a haemocytometer (Ozlab, Neubauer-improved, 0.1 mm depth) with 1 μl of the conidia suspension and covered the well with a cover slip (figure 1g). We used a microscope (Wild M3 Stereo) to count the cells in the four corner squares and the central square of the haemocytometer, as per standard protocols [26,27]. The suspensions were diluted by 10× to reduce the conidia density enough for quantification.

Figure 1.

Three randomly selected conidia suspension tubes from each treatment group ((a–c) from the acoustic stimulation group and (d–f) from the control group) and (g) haemocytometer methods for counting T. harzianum conidia (inset digitally enhanced for visual aid).

(e). Statistics and data analysis

Statistics were conducted in R v. 4.3.1 [28] in 2023.06.0 ‘Beagle Scouts’ [29] and Python. Paired two-sample t-tests were used to compare the means in conidia density. The distributions of model residuals were assessed with a Shapiro–Wilk test and QQ plots using the ‘qmath’ function of the lattice package in R. As per manufacturer instructions for our haemocytometer, we calculated the average number of conidia per square × the dilution factor (=10) × 10 000 to acquire conidia cells ml−1 (each haemocytometer square holds 10−4 ml of the suspension).

We applied raster analyses in Python to assess the growth of conidia while in the Petri dishes. Images were acquired using a Fujifilm X-T4 camera. Images were saved in Portable Network Graphics (PNG) format and cropped to remove any irrelevant background. Image colour representation was converted from RGB (red, green, blue) and to HSV (hue, saturation, value) using the OpenCV library in Python. This conversion was chosen for its ability to separate colour components, providing a more intuitive representation, and greenness was isolated due to the colour of T. harzianum conidia. The green colour range in the HSV colour space was defined as {35, 35, 35} to {180, 255, 255}. This range was determined through a combination of literature review and empirical analysis of image characteristics. A binary mask was created by thresholding the images using the defined green colour range. This step resulted in the isolation of regions corresponding to green colour. The quantification of the green colour involved automated counting of the number of green pixels in the binary mask. The percentage of greenness was calculated (i.e. automated) by dividing the count of green pixels by the total number of pixels in the image. Statistical analyses, including mean and standard deviation estimations, were performed on the quantified green colour data to assess variations across samples. We used the Mann–Whitney U-test (Wilcoxon rank-sum test) in R to compare the percentage of green coverage between treatment groups. Data visualizations were produced using a combination of R, Python and Adobe Illustrator Creative Cloud 2022 [30].

3. Results

(a). Radial (mycelial) growth

Acoustic stimulation had a strong effect on increasing mycelial radial growth on day 2 (acoustic treatment: x̄ = 60.5 mm, s.d. = 3.09; control: x̄ = 58.5 mm, s.d. = 1.89; t = 2.5, d.f. = 18, p = 0.02). On day 3, there was no effect of acoustic stimulation on mycelial radial growth (t = 0.5, d.f. = 18, p = 0.58). However, by day 4, there was a strong effect of acoustic stimulation, and mycelial growth had increased substantially (acoustic treatment: x̄ = 89.5 mm, s.d. = 1.07; control: x̄ = 82.8 mm, s.d. = 8.5; t = 3.66, d.f. = 18, p = 0.001). By day 5, there was again a strong effect of acoustic stimulation on mycelial radial growth (acoustic treatment: x̄ = 89.6 mm, s.d. = 1.07; control: x̄ = 83.4 mm, s.d. = 7.8; t = 3.37, d.f. = 18, p = 0.003).

(b). Conidia growth (proxy)

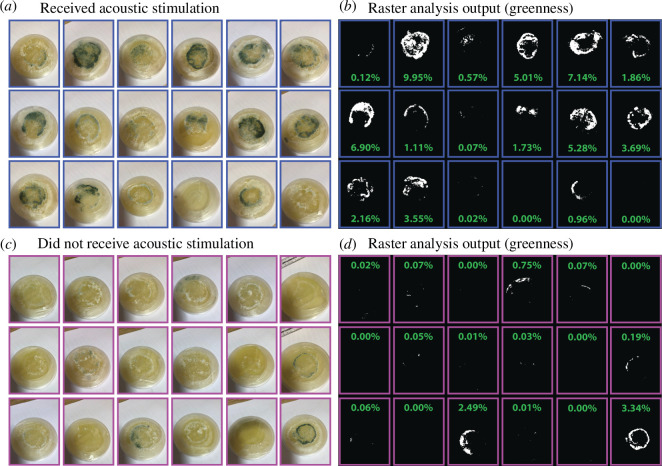

Acoustic stimulation had a strong effect on increasing conidial growth (figure 2; day 5 acoustic treatment: x̄ = 2.8% coverage, s.d. = 2.9; control: x̄ = 0.39% coverage, s.d. = 0.94; W = 61.5, d.f. = 18, p = 0.001).

Figure 2.

Images of the Petri dishes containing T. harzianum culture on day 5 and the outputs of the raster analysis of greenness—including the percentage of green cover as a proxy for conidia growth. (a) Acoustic stimulation group, (b) acoustic stimulation group, (c) culture control group and (d) raster analysis output for the control group).

(c). Conidia cell density

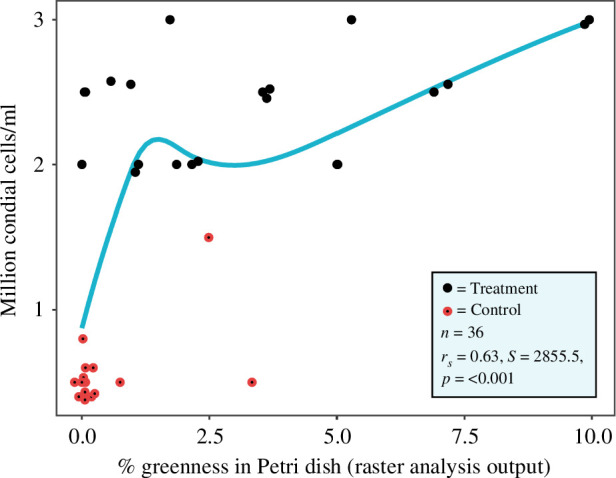

Acoustic stimulation had a strong effect on increasing conidial density (day 5 acoustic stimulation: conidial density: x̄ = 2.42 × 106 cells ml−1; control: x̄ = 5.42 × 105 cells ml−1; t = 18.2, d.f. = 18, p = < 0.001). Cell density was strongly and positively correlated with the percentage of green cover in the Petri dishes (rs = 0.63, S = 2855, p = < 0.001; figure 3).

Figure 3.

Correlation between the conidia cell density (determined via the haemocytometer) and the percentage greenness coverage in the Petri dishes. The blue line represents a smoothing (direction and strength of correlation) fitted to the data points.

4. Discussion

Sound is a critical component of ecosystems, and we can detect acoustic properties to monitor the restoration of soil biodiversity via ecoacoustics [8]. However, the application of acoustic properties in a targeted way to alter and potentially enhance natural components (e.g. microbiota) that could benefit restoration remains unexplored. We show that acoustic stimulation increased the growth rate and sporulation of T. harzianum, a well-known plant growth-promoting fungus [31]. Our novel raster analysis provided a good measure of conidia growth and coverage in Petri dishes and the haemocytometer counts. The potential mechanisms causing such effects may be mechanoreceptor stimulation and less likely a piezoelectric effect, but this needs further investigation. Piezoelectric effects, induced by mechanical pressure (e.g. from acoustic waves) on piezoelectric materials, may influence cellular and molecular processes in living organisms (e.g. in peptides, amino acids and proteins) and viruses [32]. Mechanoreceptor stimulation, such as the activation of mechanosensitive ion channels in cells (e.g. by touch, sound and other mechanical stimulation), plays a pivotal role in translating mechanical signals into cellular responses, impacting processes such as gene expression and cell signalling pathways [33]. Acoustic stimulation can also affect the production of various metabolites in Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast in a liquid medium [34,35]. It can also influence the production of quorum-sensing-regulated pigments, prodigiosin and violacein [34]. Therefore, with refinement, acoustic stimulation has the potential to be developed into a tool to affect specific ecological functions (e.g. organic matter decomposition). Our results are consistent with previous studies, including Hofstetter et al. [18], who showed that refrigerator acoustic vibrations can increase fungal biomass at high frequencies (above 5 kHz, as per our study), and Harris et al. [35], who found that 90 dB acoustic stimulation increased fungal growth in liquid media. Hofstetter et al. [18] also suggested that low frequencies (below 165 Hz) could reduce the growth rate of Botrytis sp.

Whether certain sound parameters influence particular fungal species or guilds is yet to be determined. This is a worthwhile research inquiry because it could have broad-reaching implications, such as improving ecosystem restoration and sustainable agricultural outcomes (e.g. increasing the biomass of desirable fungi including plant growth-promoting and commercial species and suppressing undesirable fungi such as pathogens towards humans and desirable plants). Of course, the potential unintended or undesirable consequences of using this technology also need to be investigated (e.g. non-target impacts). However, if our study results hold in larger trials, they could revolutionize our understanding of how microbiota respond to environmental conditions.

In ecosystem restoration and sustainable agriculture contexts, we suggest two priority applications to further develop: (i) applying acoustic stimulation to enhance the production efficiency of microbial inoculants (e.g. potentially enhancing the growth rate but also the viability, quality and functional potential of beneficial fungal spores) and (ii) the direct application of a sound source in ecosystems (in situ) to help improve their biological integrity via a direct effect on soil and potentially non-soil microbiota. We also note some limitations of our study, including those that would benefit future studies once addressed: (i) improvements to the sound attenuation chambers can be made; for instance, using sound-dampening materials on the exterior of the chamber to reduce ambient sounds from penetrating the interior and (ii) an improved experimental design could be to either replicate the chambers (e.g. multiple per treatment) or rotate the treatments among the chambers to prevent spatial confounders.

While still in the early stages, our results are encouraging the development of innovative restoration techniques that leverage sound to alter soil ecosystem functioning. Considering the broader restoration imperative, exploring the role of acoustic stimulation represents an exciting and underexplored avenue of research. Expanding our understanding of the relationships between ecoacoustics, soil microbiota and ecosystem functioning paves the way for advancements in restoration [36], microbial ecology and sustainable agriculture.

5. Conclusion

Our study introduces a novel dimension to the ecosystem restoration and sustainable agriculture domains by investigating the effects of acoustic stimulation on plant growth-promoting fungi. Demonstrating a tangible impact on fungal activity, our findings suggest that carefully tuned acoustic parameters might be able to enhance ecological processes. We propose two critical avenues for future research: optimizing acoustic stimulation for microbial inoculants for plants and exploring in situ applications to enhance biological integrity and desirable processes in eco- and agrosystems. Despite the need for further investigation into potential unintended consequences, our study marks an important stride toward leveraging sound as an innovative tool to help promote ecosystem restoration.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge that this research was conducted on the land of the Kaurna people in Tarntanya (Adelaide, South Australia).

Contributor Information

Jake M. Robinson, Email: jake.robinson@flinders.edu.au; bio.jmr@gmail.com.

Amy Annells, Email: anne0004@flinders.edu.au.

Christian Cando-Dumancela, Email: christian.candodumancela@flinders.edu.au.

Martin F. Breed, Email: martin.breed@flinders.edu.au.

Ethics

This work did not require ethical approval from a human subject or animal welfare committee.

Data accessibility

Data are available from Flinders ROADS: Repository of Open Access DataSets [37].

Supplementary material is available online [38].

Declaration of AI use

We have not used AI-assisted technologies in creating this article.

Authors’ contributions

J.M.R.: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, software, supervision, validation, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; A.A.: validation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; C.C.-D.: investigation, methodology, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; M.F.B.: supervision, validation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing.

All authors gave final approval for publication and agreed to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Conflict of interest declaration

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

M.F.B. was funded by the Australian Research Council (grants DP210101932, LP190100051 and LP190100484) and the New Zealand Ministry of Business Innovation and Employment (grant UOWX2101).

References

- 1. Tedesco AM, et al. 2023. Beyond ecology: ecosystem restoration as a process for social–ecological transformation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 38, 643–653. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2023.02.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lázaro-González A, Andivia E, Hampe A, Hasegawa S, Marzano R, Santos AMC, Castro J, Leverkus AB. 2023. Revegetation through seeding or planting: a worldwide systematic map. J. Environ. Manage. 337, 117713. ( 10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.117713) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hugron S, Guêné-Nanchen M, Roux N, LeBlanc MC, Rochefort L. 2020. Plant reintroduction in restored peatlands: 80% successfully transferred—does the remaining 20% matter? Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 22, e01000. ( 10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01000) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Singh Rawat V, Kaur J, Bhagwat S, Arora Pandit M, Dogra Rawat C. 2023. Deploying microbes as drivers and indicators in ecological restoration. Restor. Ecol. 31, e13688. ( 10.1111/rec.13688) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hossain A, Krupnik TJ, Timsina J, Mahboob MG, Chaki AK, Farooq M, Bhatt R, Fahad S, Hasanuzzaman M. 2020. Agricultural land degradation: processes and problems undermining future food security. In Environment, climate, plant and vegetation growth, pp. 17–61. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. ( 10.1007/978-3-030-49732-3_2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vega-Hidalgo Á, Flatt E, Whitworth A, Symes L. 2021. Acoustic assessment of experimental reforestation in a Costa Rican rainforest. Ecol. Indic. 133, 108413. ( 10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.108413) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Maeder M, Guo X, Neff F, Schneider Mathis D, Gossner MM. 2022. Temporal and spatial dynamics in soil acoustics and their relation to soil animal diversity. PLoS One 17, e0263618. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0263618) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Robinson JM, Breed MF, Abrahams C. 2023. The sound of restored soil: using ecoacoustics to measure soil biodiversity in a temperate forest restoration context. Restor. Ecol. 31, e13934. ( 10.1111/rec.13934) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Görres CM, Chesmore D. 2019. Active sound production of scarab beetle larvae opens up new possibilities for species-specific pest monitoring in soils. Sci. Rep. 9, 10115. ( 10.1038/s41598-019-46121-y) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Znidersic E, Watson DM. 2022. Acoustic restoration: using soundscapes to benchmark and fast-track recovery of ecological communities. Ecol. Lett. 25, 1597–1603. ( 10.1111/ele.14015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McAfee D, Williams BR, McLeod L, Reuter A, Wheaton Z, Connell SD. 2023. Soundscape enrichment enhances recruitment and habitat building on new oyster reef restorations. J. Appl. Ecol. 60, 111–120. ( 10.1111/1365-2664.14307) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Solan M, Hauton C, Godbold JA, Wood CL, Leighton TG, White P. 2016. Anthropogenic sources of underwater sound can modify how sediment-dwelling invertebrates mediate ecosystem properties. Sci. Rep. 6, 20540. ( 10.1038/srep20540) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Francis CD, et al. 2017. Acoustic environments matter: synergistic benefits to humans and ecological communities. J. Environ. Manage. 203, 245–254. ( 10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.07.041) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kunc HP, Schmidt R. 2019. The effects of anthropogenic noise on animals: a meta-analysis. Biol. Lett. 15, 20190649. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2019.0649) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Robinson JM, Cameron R, Parker B. 2021. The effects of anthropogenic sound and artificial light exposure on microbiomes: ecological and public health implications. Front. Ecol. Evol. 9, 662588. ( 10.3389/fevo.2021.662588) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gu S, Zhang Y, Wu Y. 2016. Effects of sound exposure on the growth and intracellular macromolecular synthesis of E. coli k-12. PeerJ 4, e1920. ( 10.7717/peerj.1920) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cai W, Dunford NT, Wang N, Zhu S, He H. 2016. Audible sound treatment of the microalgae Picochlorum oklahomensis for enhancing biomass productivity. Bioresour. Technol. 202, 226–230. ( 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.12.019) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hofstetter RW, Copp BE, Lukic I. 2020. Acoustic noise of refrigerators promote increased growth rate of the gray mold Botrytis cinerea. J. Food Saf. 40, 12856. ( 10.1111/jfs.12856) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yuan H, Han P, Tao K, Liu S, Gazit E, Yang R. 2019. Piezoelectric peptide and metabolite materials. Research 2019, 9025939. ( 10.34133/2019/9025939) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Martinac B, et al. 2020. Cell membrane mechanics and mechanosensory transduction. Curr. Top. Membr. 86, 83–141. ( 10.1016/bs.ctm.2020.08.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wagg C, Schlaeppi K, Banerjee S, Kuramae EE, van der Heijden MGA. 2019. Fungal–bacterial diversity and microbiome complexity predict ecosystem functioning. Nat. Commun. 10, 4841. ( 10.1038/s41467-019-12798-y) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li RX, Cai F, Pang G, Shen QR, Li R, Chen W. 2015. Solubilisation of phosphate and micronutrients by Trichoderma harzianum and its relationship with the promotion of tomato plant growth. PLoS One 10, e0130081. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0130081) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Illescas M, Pedrero-Méndez A, Pitorini-Bovolini M, Hermosa R, Monte E. 2021. Phytohormone production profiles in Trichoderma species and their relationship to wheat plant responses to water stress. Pathogens 10, 991. ( 10.3390/pathogens10080991) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Swain H, Mukherjee AK. 2020. Host–pathogen–trichoderma interaction. In Trichoderma. Host pathogen interactions and applications, pp. 149–165. Singapore: Springer Singapore. ( 10.1007/978-981-15-3321-1_8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jahan N, Sultana S, Adhikary SK, Rahman S, Yasmin S. 2013. Evaluation of the growth performance of Trichoderma harzianum (Rifai.) on different culture media. J. Agri. Vet. Sci. 3, 44–50. ( 10.9790/2380-0344450) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Abdulmalik Z, Shittu M, Adamu S, Ambali SF, Oyeyemi BF. 2023. Elevated blood mercury and haematological response in free ranging chicken (Gallus gallus domesticus) from gold mining areas in Zamfara State Nigeria. Environ. Chem. Ecotoxicol. 5, 39–44. ( 10.1016/j.enceco.2022.12.003) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Milan KL, Ganesh GV, Mohandas S, Ramkumar KM. 2024. Counting of cells by hemocytometer. In Advanced mammalian cell culture techniques, pp. 28–31. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ( 10.1201/9781003397755-9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. RStudio Team . 2023. RStudio: Integrated Development for R Studio, PBC, Boston, MA

- 29. R Core Team . 2023. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. See https://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Adobe . 2021. Adobe Illustrator. See https://helpx.adobe.com/illustrator/using/whats-new.html (accessed 7 July 2023).

- 31. López AC, Chelaliche AS, Alderete JA, Zapata PD, Alvarenga AE. 2023. Assessment of Trichoderma spp. from Misiones (Argentina) as biocontrol agents and plant growth-promoting fungi on the basis of cell wall degrading enzymes and indole acetic acid production. Ind. Phytopathol. 76, 923–928. ( 10.1007/s42360-023-00658-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lee BY, Zhang J, Zueger C, Chung WJ, Yoo SY, Wang E, Meyer J, Ramesh R, Lee SW. 2012. Virus-based piezoelectric energy generation. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 351–356. ( 10.1038/nnano.2012.69) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mishra R, Minc N, Peter M. 2022. Cells under pressure: how yeast cells respond to mechanical forces. Trends Microbiol. 30, 495–510. ( 10.1016/j.tim.2021.11.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shah A, Raval A, Kothari V. 2016. Sound stimulation can influence microbial growth and production of certain key metabolites. J. Microb. Biotech. Food Sci. 5, 330–334. ( 10.15414/jmbfs.2016.5.4.330-334) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Harris A, Lindsay MA, Ganley ARD, Jeffs A, Villas-Boas SG. 2021. Sound stimulation can affect Saccharomyces cerevisiae growth and production of volatile metabolites in liquid medium. Metabolites 11, 605. ( 10.3390/metabo11090605) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Robinson JM, et al. 2022. Ecosystem restoration is integral to humanity’s recovery from COVID-19. Lancet Plan Health 6, e769–e773. ( 10.1016/S2542-5196(22)00171-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Robinson JM. 2024. Sonic restoration: acoustic stimulation enhances plant growth-promoting fungi activity. Flinders ROADS: Repository of Open Access DataSets ( 10.25451/flinders.25905433) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38. Robinson JM, Annells A, Cando-Dumancela C, Breed M. 2024. Data from: Sonic restoration: Acoustic stimulation enhances plant growth-promoting fungi activity. Figshare. ( 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.7472134) [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from Flinders ROADS: Repository of Open Access DataSets [37].

Supplementary material is available online [38].