Abstract

Aims

The liner design is a key determinant of the constraint of a reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (rTSA). The aim of this study was to compare the degree of constraint of rTSA liners between different implant systems.

Methods

An implant company’s independent 3D shoulder arthroplasty planning software (mediCAD 3D shoulder v. 7.0, module v. 2.1.84.173.43) was used to determine the jump height of standard and constrained liners of different sizes (radius of curvature) of all available companies. The obtained parameters were used to calculate the stability ratio (degree of constraint) and angle of coverage (degree of glenosphere coverage by liner) of the different systems. Measurements were independently performed by two raters, and intraclass correlation coefficients were calculated to perform a reliability analysis. Additionally, measurements were compared with parameters provided by the companies themselves, when available, to ensure validity of the software-derived measurements.

Results

There were variations in jump height between rTSA systems at a given size, resulting in large differences in stability ratio between systems. Standard liners exhibited a stability ratio range from 126% to 214% (mean 158% (SD 23%)) and constrained liners a range from 151% to 479% (mean 245% (SD 76%)). The angle of coverage showed a range from 103° to 130° (mean 115° (SD 7°)) for standard and a range from 113° to 156° (mean 133° (SD 11°)) for constrained liners. Four arthroplasty systems kept the stability ratio of standard liners constant (within 5%) across different sizes, while one system showed slight inconsistencies (within 10%), and ten arthroplasty systems showed large inconsistencies (range 11% to 28%). The stability ratio of constrained liners was consistent across different sizes in two arthroplasty systems and inconsistent in seven systems (range 18% to 106%).

Conclusion

Large differences in jump height and resulting degree of constraint of rTSA liners were observed between different implant systems, and in many cases even within the same implant systems. While the immediate clinical effect remains unclear, in theory the degree of constraint of the liner plays an important role for the dislocation and notching risk of a rTSA system.

Cite this article: Bone Jt Open 2024;5(10):818–824.

Keywords: Shoulder arthroplasty, Reverse shoulder replacement, Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty, Stability ratio, Dislocation, reverse total shoulder arthroplasty, glenospheres, Constrained liners, arthroplasty, Shoulder, Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), Shoulder Arthroplasty, glenoid, humeral components, scapula

Introduction

Reverse shoulder arthroplasty (rTSA) is an effective surgical option to relieve pain and improve shoulder function for a variety of indications.1 Surgical technique and implant design have evolved over the last decade, which has led to an overall decrease in complication rates.2 However, periprosthetic instability is still one of the most commonly reported complications following rTSA.2,3 Factors reported to be associated with periprosthetic instability include patient-related factors such as male sex, BMI > 30 kg/m2, decreased bone mineral density, subscapularis deficiency, soft-tissue pathologies (e.g. Ehler-Danlos), Parkinson’s disease, and prior surgery or trauma of the affected limb.2-10 Furthermore, the risk of periprosthetic instability is influenced by various implant configuration aspects, such as centre of rotation (COR) offset, glenosphere diameter, humeral length, inclination and torsion, as well as the degree of constraint of the liner.2,5,11-13 To our knowledge, the degree of constraint of liners of different rTSA systems has not been systematically compared (Figure 1).

Fig. 1.

Example of a humeral liner for reverse total shoulder arthroplasty made out of polyethylene (Univers Reverse; Arthrex, USA).

The stability ratio of a ball and socket joint is defined as the ratio between the maximum translational force against which the joint offers resistance, and dislocation at a given concavity compression force. In the past, a mathematical formula to calculate the stability ratio of a shoulder joint based on jump height and radius measurements has been published and validated.14,15 The same formula can be used to determine the stability ratio of different ball and socket joints including a rTSA.

The aim of this study was to measure the jump height and determine the stability ratio of different RTSA liners, allowing comparisons of the degree of constraint of liners between different implant systems.

Methods

The measurements were performed using the implant-provider independent 3D planning software mediCAD 3D shoulder v. 7.0; module v. 2.1.84.173.43 (mediCAD Hectec, Germany). Measurements were performed for all 13 rTSA systems available as templates on the software. The included rTSA systems were:

Affinis Inverse Ceramys and CoCrMo Inlay (Mathys, Switzerland)

Comprehensive Shoulder Arthroplasty System (Zimmer Biomet, USA)

δ XTEND Prothesis (DePuy Synthes, USA)

Embrace Shoulder System – UHMWPE and Enduro-S (CoCrMo)-Inlay (Link, Germany)

Equinoxe Shoulder Reverse System (Exactech, USA)

Perform Reversed (Stryker, USA)

Reverse Shoulder Prosthesis (Enovis, USA)

Reverse Shoulder System (Medacta International, Switzerland)

SMR Reverse Shoulder (LimaCorporate, Italy)

Trabecular Metal Shoulder Arthroplasty System (Zimmer Biomet)

Unic Reverse (Evolutis, France)

Univers Reverse Shoulder System (Arthrex, USA)

Verso shoulder System (Innovative Design Orthopaedics, UK)

Moreover, the official measurement parameters of liners from the companies themselves could be obtained for Equinoxe Shoulder Reverse System (Exactech), Reverse Shoulder System (Medacta), and Univers Reverse Shoulder System (Arthrex).

All available glenosphere/cup sizes were analyzed and both constrained and standard liners were evaluated. Ten out of the 13 systems provided both a standard and a constrained liner, whereas three systems only provided standard liner options. Two systems had two different material types of standard liners, which were evaluated separately.

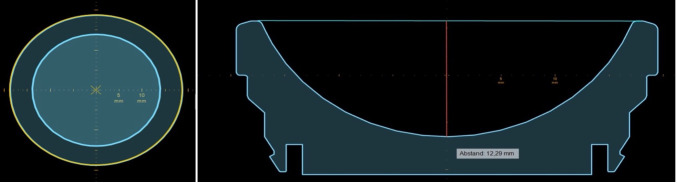

Within the planning programme, the templates of the different liners were positioned with their concavity surface strictly parallel with the axial plane. Then, the centre of the liners’ concavity was determined using a best-fit circle. The resulting frontal plane passing through the midpoint was used for further measurements. After drawing a tangential line on top of the concavity, the middle of its diameter was marked, and an orthogonal line drawn until reaching the bottom of the concavity. The length of the orthogonal line resembled the jump height. The radius was determined by dividing the size of the glenosphere/cup combination by two (Figure 2).

Fig. 2.

Screenshot of a measurement on mediCAD 3D shoulder. Left: axial view; the liner is positioned strictly parallel to the axial plane; the centre of the liners’ concavity is determined by using a best-fit circle. Right: frontal view; first a tangential line is drawn on top of the concavity (blue line). Then, the jump height is determined by drawing an orthogonal line (red) from the middle to the bottom of the concavity.

The measurements were performed independently by an orthopaedic fellow (ES) and a medical student (JP). The average of both raters was used for further calculations.

rTSA stability ratio

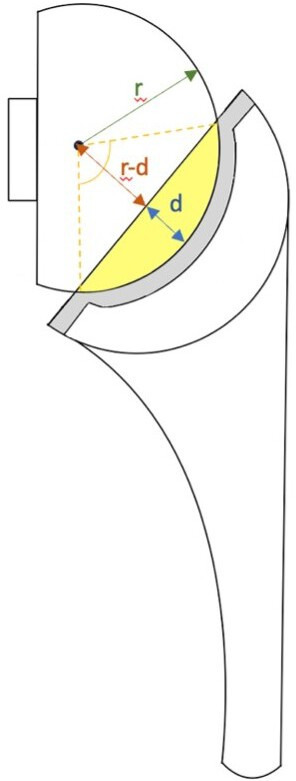

A mathematical formula, as previously described,15 was validated for calculating the bony shoulder stability ratio (BSSR),16 and adapted to calculate the liner stability ratio (LSR). The BSSR quantifies the shoulder’s bony stability by calculating the ratio of the maximum translational force (T) that can be resisted by a given compressive force (C), based on the geometry of the glenoid concavity and the humeral head. It is derived using Pythagorean trigonometric identities, incorporating the radius of the glenoid (r) and the concavity depth (d) to model the ball-and-socket configuration of the joint. To adapt the BSSR to the LSR, the humeral head radius was replaced by the glenosphere radius, and the glenoid depth by the jump height of the liner. The LSR approximates the ratio of the maximum translational force that can be withstood by the rTSA at a given compression force before a dislocation will occur (Figure 3).

Fig. 3.

Illustration of a reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: radius (r) of the glenosphere and concavity depth (d) or jump height of the liner are required to calculate the liner stability ratio (LSR) using the aforementioned formula. Yellow area: the extent of the glenosphere covered by the liner; yellow striped line: angle of coverage (degree of glenosphere coverage by the liner).

The final formula was:

To calculate the degree of glenosphere coverage by the liner, the following formula is used:

Statistical analysis

All measurements were performed by both raters independently and the average of the measurement results was used for comparisons against industry presented data. The normality of the distribution of the differences was tested using QQ plots using the MatPlotLib PyPlot package in Python. Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) estimates and their 95% CIs were calculated using the Pingouin statistical package in Python. For comparison of rater agreement in MediCad, a two-way single random raters ICC model (ICC2) was used.17 For comparison of MediCad measurements and company-provided measurements, a two-way single fixed raters ICC model (ICC3) was used.18 To assess agreement between the average rater measurement in MediCad and company provided measurements, Bland-Altman plots were created with the Pingouin package in Python. All stability ratio calculations were performed with Excel v. 16.76 (Microsoft, USA). Only the measured data, not the industry-presented data, were used for stability ratio calculation purposes.

Results

Jump height measurement comparison between raters showed a high concordance with excellent intraclass correlation coefficient (0.9998 (95% CI 0.9997 to 0.9999)). There was also high concordance between the measured jump heights and the provided company data (Table I). The mean of differences was 0.05 mm (95% CI 0.02 to 0.08) and the 95% limits of agreement were -0.04 mm (95% CI -0.09 to 0.00) to 0.15 mm (95% CI 0.10 to 0.20). The ICC was 0.9998 (95% CI 0.9993 to 0.9999).

Table I.

Comparison between the measured jump heights and jump heights provided by companies.

| Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty system | Cup/glenosphere size | Inlay type | Company jump height, mm | Measured height, mm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equinoxe (Exactech) | 38 | Standard | 8.2 | 8.2 |

| 42 | Standard | 8.5 | 8.4 | |

| 38 | Constrained | 11.7 | 11.6 | |

| 46 | Constrained | 12.3 | 12.2 | |

| Reverse Shoulder System (Medacta) | 32 | Standard | 6.4 | 6.4 |

| 36 | Standard | 7.2 | 7.1 | |

| 39 | Standard | 7.8 | 7.8 | |

| 42 | Standard | 8.4 | 8.4 | |

| Univers Reverse Humeral Prosthesis (Arthrex) | 36 | Standard | 9.8 | 9.7 |

| 39 | Standard | 10.6 | 10.6 | |

| 42 | Standard | 11.4 | 11.4 | |

| 36 | Constrained | 12.3 | 12.3 | |

| 39 | Constrained | 13.1 | 13.0 | |

| 42 | Constrained | 13.9 | 13.9 |

There were variations in jump height between rTSA systems at a given size resulting in large differences in stability ratio between systems (Table II and Table III). Standard liners exhibited a stability ratio range from 126% to 214% (mean 158% (SD 23%)) and constrained liners a range from 151% to 479% (mean 245% (SD 76%)).

Table II.

Standard liner jump height, liner stability ratio, and angle of coverage of different reverse total shoulder arthroplasty systems.

| Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty system | Cup/glenosphere size | Jump height, mm | Stability ratio, % | Angle of coverage, ° |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affinis Inverse (Ceramys) Inlay (Mathys) | 36 | 7.5 | 139 | 109 |

| 39 | 8.6 | 148 | 112 | |

| 42 | 9.9 | 160 | 116 | |

| Affinis Inverse (CoCrMo) Inlay (Mathys) | 36 | 7.9 | 147 | 111 |

| 39 | 9.0 | 156 | 115 | |

| 42 | 10.4 | 170 | 119 | |

| Comprehensive Shoulder Arthroplasty (Zimmer Biomet) | 36 | 9.5 | 187 | 124 |

| 41 | 9.6 | 160 | 116 | |

| δ XTEND (DePuy Synthes) | 38 | 8.3 | 147 | 112 |

| 42 | 9.4 | 151 | 113 | |

| Embrace Shoulder System - Enduro-S (CoCrMo) Inlay (Link) | 39 | 8.9 | 155 | 114 |

| 42 | 8.8 | 141 | 109 | |

| Embrace Shoulder System UHMWPE Inlay (Link) | 36 | 8.9 | 169 | 119 |

| 39 | 8.9 | 155 | 114 | |

| 42 | 9.0 | 144 | 110 | |

| Equinoxe (Exactech) | 38 | 8.2 | 144 | 110 |

| 42 | 8.4 | 134 | 107 | |

| 46 | 8.7 | 126 | 103 | |

| Reverse Shoulder Prosthesis (DJO/Encore) | 32 | 8.7 | 193 | 125 |

| 36 | 9.9 | 197 | 126 | |

| 40 | 10.9 | 194 | 126 | |

| 44 | 12.0 | 197 | 126 | |

| Reverse Shoulder System (Medacta) | 32 | 6.4 | 134 | 107 |

| 36 | 7.1 | 132 | 106 | |

| 39 | 7.8 | 134 | 106 | |

| 42 | 8.4 | 133 | 106 | |

| SMR Reverse shoulder (LimaCorporate) | 36 | 10.4 | 214 | 130 |

| SMR Reverse shoulder - HP (LimaCorporate) | 40 | 8.9 | 150 | 113 |

| 44 | 8.8 | 134 | 107 | |

| Trabecular Metal Reverse (Zimmer Biomet) | 36 | 8.1 | 153 | 114 |

| 40 | 7.7 | 128 | 104 | |

| Tornier Perform Reversed (Stryker) | 33 | 7.3 | 150 | 113 |

| 36 | 8.0 | 149 | 112 | |

| 39 | 8.5 | 146 | 111 | |

| 42 | 9.9 | 160 | 116 | |

| Unic (Evolutis) | 33 | 7.9 | 164 | 117 |

| 37 | 8.4 | 154 | 114 | |

| Univers Reverse Humeral Prosthesis (Arthrex) | 36 | 9.7 | 193 | 125 |

| 39 | 10.6 | 194 | 125 | |

| 42 | 11.4 | 194 | 125 | |

| Verso shoulder system (Innovative Design Orthopaedics) | 36 | 8.0 | 149 | 112 |

| 41 | 10.4 | 175 | 121 |

Table III.

Constrained liner jump height, liner stability ratio, and angle of coverage of different reverse total shoulder arthroplasty systems.

| Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty system | Cup/glenosphere size | Jump height, mm | Stability ratio, % | Angle of coverage, ° |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive Shoulder Arthroplasty (Zimmer Biomet) | 36 | 12.6 | 315 | 145 |

| 41 | 11.7 | 209 | 129 | |

| δ XTEND (DePuy Synthes) | 38 | 12.0 | 251 | 137 |

| 42 | 13.2 | 248 | 136 | |

| Equinoxe (Exactech) | 38 | 11.6 | 235 | 134 |

| 42 | 12.2 | 217 | 131 | |

| 46 | 12.8 | 201 | 127 | |

| Reverse Shoulder Prosthesis (DJO/Encore) | 32 | 9.9 | 244 | 135 |

| 36 | 11.1 | 243 | 135 | |

| 40 | 12.4 | 245 | 136 | |

| 44 | 13.7 | 244 | 135 | |

| SMR Reverse shoulder - HP (LimaCorporate) | 40 | 9.8 | 169 | 119 |

| 44 | 9.9 | 151 | 113 | |

| Trabecular Metal Reverse (Zimmer Biomet) | 36 | 9.7 | 193 | 125 |

| 40 | 9.1 | 153 | 114 | |

| Tornier Perform Reversed (Stryker) | 33 | 9.6 | 216 | 130 |

| 36 | 9.8 | 194 | 126 | |

| 39 | 10.5 | 191 | 125 | |

| 42 | 11.0 | 184 | 123 | |

| Unic (Evolutis) | 37 | 11.9 | 264 | 139 |

| Univers Reverse Humeral Prosthesis (Arthrex) | 36 | 12.3 | 300 | 143 |

| 39 | 13.0 | 281 | 141 | |

| 42 | 13.9 | 277 | 140 | |

| Verso shoulder system (Innovative Design Orthopaedics) | 36 | 13.9 | 426 | 154 |

| 41 | 16.3 | 479 | 156 |

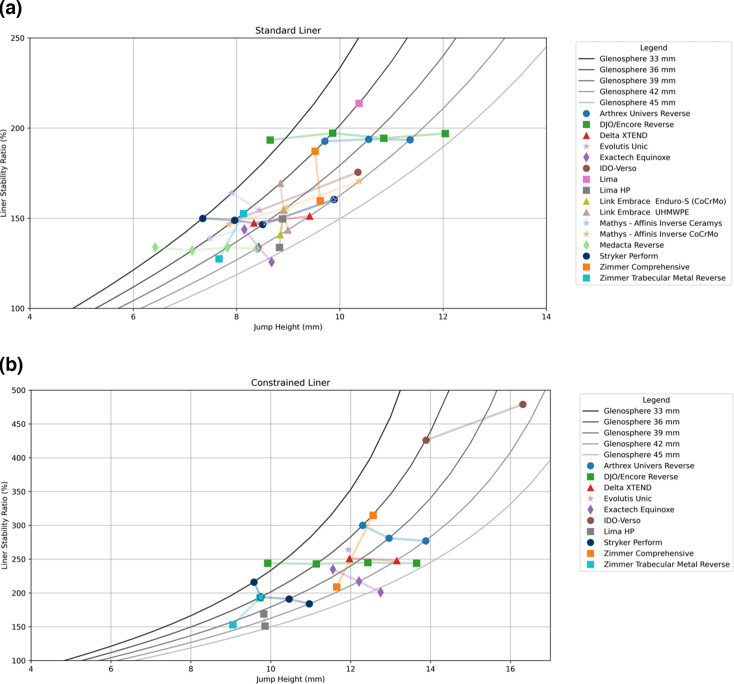

Four arthroplasty systems maintained a consistent stability ratio for standard liners across the different sizes (within 5%). Slight inconsistencies (within 10%) were seen in one system. Ten arthroplasty systems exhibited notable inconsistencies in the range of 10% to 28%. For the inconsistency group, we analyzed the trend of the stability ratio as glenospheres increased in size. An increase in stability ratio with larger sizes was noted in three systems, a decrease in seven systems, and a wavering trend was seen in one system (Table IV and Figure 4).

Table IV.

Stability ratio for standard liners across their own different sizes.

| Arthroplasty system | Trend |

|---|---|

| Stable stability ratio (< 5%) | |

| δ XTEND (DePuy Synthes) | ↔ |

| Reverse Shoulder Prosthesis (DJO/Encore) | ↔ |

| Reverse Shoulder System (Medacta) | ↔ |

| Univers Reverse Humeral Prosthesis (Arthrex) | ↔ |

| Slight inconsistencies (5% to 10%) | |

| Unic (Evolutis) | ↘ |

| Notable inconsistencies (> 10%) | |

| Affinis Inverse Ceramys Inlay (Mathys) | ↗ |

| Affinis Inverse CoCrMo Inlay (Mathys) | ↗ |

| Comprehensive Shoulder (Zimmer Biomet) | ↘ |

| Embrace Shoulder System; Enduro-S Inlay (Link) | ↘ |

| Embrace Shoulder System; UHMWPE Inlay (Link) | ↘ |

| Equinoxe (Exactech) | ↘ |

| SMR Reverse shoulder HP liners (LimaCorporate) | ↘ |

| Trabecular Metal Reverse Arthroplasty (Zimmer Biomet) | ↘ |

| Tornier Perform Reversed (Stryker) | ↘↗ |

| Verso shoulder system (IDO) | ↗ |

Fig. 4.

Diagrams illustrating the liner stability ratio of different reverse total shoulder arthroplasty systems across glenosphere/cup sizes. The reference lines (shades of grey) represent the standard change in stability ratio per increase in jump height for different cup/glenosphere sizes. a) Standard liners. b) Constrained liners.

The stability ratio of constrained liners was constant in two arthroplasty systems, and inconsistent in seven systems, with a range of 18% to 106%. One system showed an increase in stability ratio with larger sizes, while six showed a decrease (Figure 4).

The angle of coverage had a range of 103° to 130° (mean 115° (SD 7°)) for standard and 113° to 157° (mean 133° (SD 11°)) for constrained liners. The maximum variance of the angle of coverage between the different sizes within one implant system was 9.7° for standard and 16° for constrained liners.

Discussion

The instability rate of rTSAs varies between 2.3% and 5%.4,19-21 Many implant properties have been studied and modified to reduce complications and improve stability after rTSA. The usage of larger glenospheres,22 an inferior baseplate inclination of 10,°23 and glenoidal eccentricity were proven to lower the risk of rTSA dislocation.23,24 Moreover, humeral lengthening results in higher compression forces, which increases stability but may have a negative effect on the deltoid muscle.5,25 Other than compressive forces provided by the muscles, the liner depth is the second most important stability-generating factor in rTSA.7,24 A deepening of the concavity leads to a steep increase in stability ratio, which becomes exponential as the concavity depth approaches the joint radius.15

In this present study, a wide spread of liner-dependent stability ratios was observed when comparing different arthroplasty models from various providers. The variation is so pronounced that constrained liners of some companies offer the same degree of constrained than the standard liners of other companies. Moreover, in a single implant system, the stability ratio increased by an additional 106% with a change in glenosphere/cup size. Certain companies exhibit a decreasing trend in the degree of constraint as glenospheres increase in size. This challenges the belief that larger glenospheres inherently result in greater stability by means of increased soft-tissue tensioning compared to smaller sizes,22 due to the concomitant loss of constraint on the liner side.

Certainly, the stability ratio created by a concave liner is affected by the tilt of the liner in comparison to the direction of the dislocation force. Therefore, humeral component inclination and version also has an effect in clinical reality. Nonetheless, the range of inclination of humeral components is limited, with systems generally exhibiting comparable angles within the range of 135° to 155°, and mostly the version of all systems is 0° with few exceptions allowing for 10° tilt.

Although a higher stability ratio can reduce dislocation, a potential consequence of greater jump height may be increased scapular notching. Depending on the arm position, the likelihood of inferior scapula impingement grows.26,27 Repetitive impaction of the prothesis’s humeral component against the bone leads to erosion on the scapula neck, primarily occurring during arm adduction,28-30 but also seen in anteversion and external rotation.31,32 Nonetheless, in a clinical matched-cohort study,33 no differences in range of motion (ROM) in rTSA using standard or constrained liners in a system with lateralized glenoid design and 135° humeral neck shaft angle were observed supporting the use of liners with a higher jump height and degree of constraint in lateralized rTSA designs.33 The negative effect of a constrained liner on notching might, however, be more pronounced in a Grammont-style rTSA system. Depending on various studies the positioning of the glenosphere,32 as well as its eccentricity and the humeral cup design, influences the risk of inferior scapula notching.34 In theory, the greater glenosphere coverage of more constrained liners decreases impingement-free ROM; however, this depends on the amount of glenosphere overhang over the glenoid.32 Accordingly, another clinical study showed that constrained liners were not necessarily associated with a higher risk of scapular notching than conventional liners.35 Moreover, subcoracoid and subacromial impingement should not be affected by the degree of constraint of the liner.

Considering the unexpected inconsistencies in liner design between different and even within the same implant systems, it becomes apparent that this may not only impact stability, but also potentially influence notching. This underscores the need for further analysis and potential adjustments by companies to ensure optimal stability and performance.

Limitations

A limitation of this study is the dependence on the accuracy of the templates provided by the implant companies to the mediCAD software. However, we validated the measurements by comparing the performed measurements on the software with available actual measurement data of companies showing no relevant differences. Furthermore, reliability of the measurement process between raters was confirmed by our data. An additional limitation is the fact that the glenosphere size was used to determine the radius, while in reality usually the cup has a minimally larger radius than the glenosphere, to allow for production tolerances. As this was the same for all analyzed rTSA systems, comparability is not compromised. Furthermore, the differences in radius are minimal and thus do not affect the actual values to a relevant degree.

In conclusion, large differences in jump height and resulting degree of constraint of rTSA liners were observed between different implant systems, and in many cases even within the same implant systems. While the immediate clinical effect remains unclear, in theory the degree of constraint of the liner plays an important role in the dislocation and notching risk of a rTSA system.

Take home message

- Significant variations in jump height and the resulting degree of constraint in reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (rTSA) liners are evident both between different implant systems and, in many cases, within the same system.

- While the immediate clinical impact is still unclear, theoretically, the degree of constraint plays a crucial role in influencing the risk of dislocation and notching in a rTSA system.

Author contributions

P. Moroder: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing

E. Herbst: Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing

J. Pawelke: Investigation

S. Lappen: Validation, Writing – review & editing

E. Schulz: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft

Funding statement

The authors received no financial or material support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ICMJE COI statement

P. Moroder is a consultant and receives royalties from Arthrex and Medacta, unrelated to this study. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Data sharing

The data that support the findings for this study are available to other researchers from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Schwyzer Stiftung for funding the work of Eva Herbst.

Ethical review statement

Ethical approval was not required for this study as it did not involve human subjects, animals, or any sensitive personal information.

Open access funding

The authors report that the open access funding for this manuscript was self-funded.

© 2024 Moroder et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) licence, which permits the copying and redistribution of the work only, and provided the original author and source are credited. See https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

Contributor Information

Philipp Moroder, Email: Philipp.Moroder@kws.ch.

Eva Herbst, Email: Eva.Herbst@kws.ch.

Jonas Pawelke, Email: Jonas.Pawelke@kws.ch.

Sebastian Lappen, Email: Sebastian.Lappen@kws.ch.

Eva Schulz, Email: schulz.eva@gmail.com.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings for this study are available to other researchers from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Mahmood A, Malal JJG, Waseem M. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty: a literature review. Open Orthop J. 2013;7:366–372. doi: 10.2174/1874325001307010366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Galvin JW, Kim R, Ment A, et al. Outcomes and complications of primary reverse shoulder arthroplasty with minimum of 2 years’ follow-up: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2022;31(11):e534–e544. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2022.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zumstein MA, Pinedo M, Old J, Boileau P. Problems, complications, reoperations, and revisions in reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(1):146–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chalmers PN, Rahman Z, Romeo AA, Nicholson GP. Early dislocation after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(5):737–744. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2013.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chae J, Siljander M, Wiater JM. Instability in reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2018;26(17):587–596. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-16-00408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cheung E, Willis M, Walker M, Clark R, Frankle MA. Complications in reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19(7):439–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gutiérrez S, Keller TS, Levy JC, Lee WE, Luo ZP. Hierarchy of stability factors in reverse shoulder arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(3):670–676. doi: 10.1007/s11999-007-0096-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rogers T, Werthel J-D, Crowe MM, et al. Shoulder arthroplasty is a viable option in patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2021;30(11):2484–2490. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2021.03.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reddy C, Venishetty N, Jones H, Mounasamy V, Sambandam S. Factors that increase the rate of periprosthetic dislocation after reverse shoulder arthroplasty. Arthroplasty. 2023;5(1):57. doi: 10.1186/s42836-023-00214-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. ASES Complications of RSA Research Group. Lohre R, Swanson DP, et al. Predictors of dislocations after reverse shoulder arthroplasty: a study by the ASES complications of RSA multicenter research group. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2024;33(1):73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2023.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pena L, Pena J, López-Anglada E, Braña AF. Instability after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: risk factors and how to avoid them. Acta Orthop Belg. 2022;88(2):372–379. doi: 10.52628/88.2.8495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Molé D, Favard L. Excentered scapulohumeral osteoarthritis. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 2007;93(6):37–94. doi: 10.1016/s0035-1040(07)92708-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lädermann A, Denard PJ, Burkhart SS. Injury of the suprascapular nerve during latarjet procedure: an anatomic study. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(3):316–321. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.08.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lazarus MD, Sidles JA, Harryman DT, Matsen FA. Effect of A chondral-labral defect on glenoid concavity and glenohumeral stability. A cadaveric model. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78-A(1):94–102. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199601000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Moroder P, Ernstbrunner L, Pomwenger W, et al. Anterior shoulder instability is associated with an underlying deficiency of the bony glenoid concavity. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(7):1223–1231. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2015.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ernstbrunner L, Werthel J-D, Hatta T, et al. Biomechanical analysis of the effect of congruence, depth and radius on the stability ratio of a simplistic “ball-and-socket” joint model. Bone Joint Res. 2016;5(10):453–460. doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.510.BJR-2016-0078.R1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Watson PF, Petrie A. Method agreement analysis: a review of correct methodology. Theriogenology. 2010;73(9):1167–1179. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979;86(2):420–428. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Trappey GJ, O’Connor DP, Edwards TB. What are the instability and infection rates after reverse shoulder arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(9):2505–2511. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1686-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Guarrella V, Chelli M, Domos P, Ascione F, Boileau P, Walch G. Risk factors for instability after reverse shoulder arthroplasty. Shoulder Elbow. 2021;13(1):51–57. doi: 10.1177/1758573219864266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bufquin T, Hersan A, Hubert L, Massin P. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of three- and four-part fractures of the proximal humerus in the elderly: a prospective review of 43 cases with a short-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89-B(4):516–520. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B4.18435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Langohr GDG, Giles JW, Athwal GS, Johnson JA. The effect of glenosphere diameter in reverse shoulder arthroplasty on muscle force, joint load, and range of motion. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(6):972–979. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2014.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Randelli P, Randelli F, Arrigoni P, et al. Optimal glenoid component inclination in reverse shoulder arthroplasty. How to improve implant stability. Musculoskelet Surg. 2014;98 Suppl 1:15–18. doi: 10.1007/s12306-014-0324-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Clouthier AL, Hetzler MA, Fedorak G, Bryant JT, Deluzio KJ, Bicknell RT. Factors affecting the stability of reverse shoulder arthroplasty: a biomechanical study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(4):439–444. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2012.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Giles JW, Langohr GDG, Johnson JA, Athwal GS. Implant design variations in reverse total shoulder arthroplasty influence the required deltoid force and resultant joint load. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(11):3615–3626. doi: 10.1007/s11999-015-4526-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Erickson BJ, Frank RM, Harris JD, Mall N, Romeo AA. The influence of humeral head inclination in reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(6):988–993. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gutiérrez S, Levy JC, Frankle MA, et al. Evaluation of abduction range of motion and avoidance of inferior scapular impingement in a reverse shoulder model. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(4):608–615. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sirveaux F, Favard L, Oudet D, Huquet D, Walch G, Molé D. Grammont inverted total shoulder arthroplasty in the treatment of glenohumeral osteoarthritis with massive rupture of the cuff. Results of a multicentre study of 80 shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86-B(3):388–395. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.86b3.14024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nicholson GP, Strauss EJ, Sherman SL. Scapular notching: recognition and strategies to minimize clinical impact. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(9):2521–2530. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1720-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nyffeler RW, Werner CML, Gerber C. Biomechanical relevance of glenoid component positioning in the reverse Delta III total shoulder prosthesis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(5):524–528. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sadoghi P, Leithner A, Vavken P, et al. Infraglenoidal scapular notching in reverse total shoulder replacement: a prospective series of 60 cases and systematic review of the literature. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:101. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kolmodin J, Davidson IU, Jun BJ, et al. Scapular notching after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: prediction using patient-specific osseous anatomy, implant location, and shoulder motion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100-A(13):1095–1103. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.17.00242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Goodloe JB, Denard PJ, Lederman E, Gobezie R, Werner BC. No difference in range of motion in reverse total shoulder arthroplasty using standard or constrained liners: a matched cohort study. JSES Int. 2022;6(6):929–934. doi: 10.1016/j.jseint.2022.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Smith T, Bäunker A, Krämer M, et al. Biomechanical evaluation of inferior scapula notching of reverse shoulder arthroplasty depending on implant configuration and scapula neck anatomy. Int J Shoulder Surg. 2015;9(4):103–109. doi: 10.4103/0973-6042.167932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kowalsky MS, Galatz LM, Shia DS, Steger-May K, Keener JD. The relationship between scapular notching and reverse shoulder arthroplasty prosthesis design. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(10):1430–1441. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings for this study are available to other researchers from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.