Abstract

This study analyzed qualitative and quantitative survey responses from 51 pediatric PSC patients and caregivers using the PSC Partners Patient Registry–Our Voices survey. The most common symptoms reported by children/caregivers include: fatigue (71%), abdominal pain (69%), anxiety (59%), appetite loss (51%), insomnia (49%), and pruritus (45%). When experiencing symptoms at their worst, over half of patients/caregivers reported limitations in physically demanding activities (67%), work/school duties (63%), social life activities (55%), and activities for fun or exercise (53%). Over half of patients/caregivers expressed willingness to participate in clinical trials, however none reported ever participating in trials for new or investigational PSC drugs. This study revealed a substantial patient/caregiver-reported symptom burden for children with PSC that impacts quality of life and limits access to clinical trials. Future efforts should focus on developing patient-centered clinical endpoints for PSC trials, increasing trial availability for pediatric PSC patients, and reducing logistical barriers to trial involvement.

INTRODUCTION

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a rare, cholestatic liver disease characterized by stricturing, inflammation, and fibrosis of the biliary tree, which can result in cirrhosis and cholangiocarcinoma.1 PSC affects approximately 0.2 to 1.5 children per 100,000.2,3 Patients may experience debilitating symptoms such as intractable pruritus, abdominal pain, fatigue, anxiety, and depression,4,5 which can interfere with work, school, leisure activities, and overall quality of life (QOL).4,6 The etiology of PSC remains unclear, and there are no effective or FDA-approved disease modifying therapies. Moreover, medications aimed at symptom relief have variable efficacy.1,7 Patients with intractable or debilitating symptoms, such as pruritus, and those that progress to end-stage liver disease often require liver transplantation.8 Even after liver transplantation, the disease recurs in approximately 25% of patients over a 10-year period.9

PSC research has mainly focused on adult patients recruited from highly specialized medical centers.6,10,11 Few studies characterize symptom burden in PSC and the disease’s impact on QOL.4 In 2014, PSC Partners Seeking a Cure launched the international PSC Partners Patient Registry to facilitate and expedite PSC research and to capture the lived experiences of adult and pediatric patients living with PSC.12 The Our Voices survey was developed by PSC Partners in preparation for the Externally-Led Patient-Focused Drug Development (EL-PFDD) Forum held in 2020 in conjunction with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). In this study, we analyzed the Our Voices survey to characterize the symptom burden, QOL, and barriers to clinical trial enrollment in children with PSC.

METHODS

The PSC Partners Patient Registry was established by PSC Partners Seeking a Cure in collaboration with the National Institutes of Health Office of Rare Disease Research (NIH ORDR), National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS). The Registry is a web-based, patient-driven program which has been reviewed and approved by North Star Review Board.12 This study was reviewed and approved by the UCSF Institutional Review Board.

The EL-PFDD meeting was developed in conjunction with the FDA and hosted by PSC Partners on October 23, 2020. The purpose of this initiative was to capture and incorporate PSC patient experiences, perspectives, and priorities into drug development and regulatory review. PSC Partners conducted the 40-question Our Voices survey to gather data on the PSC patient experience. The Our Voices survey was given to patients or parents/guardians of patients enrolled in the PSC Partners Patient Registry starting in July 2020. Patients not enrolled in the Patient Registry could also complete the survey through an external website. The survey13 includes information about demographics, disease status, concurrent diagnoses, medications, clinical trial enrollment, and QOL.

Statistical Analysis

We performed descriptive statistics to analyze the prevalence of symptoms and their impact on patients’ functioning and QOL. We reviewed free text responses from the Our Voices survey and transcribed caregiver/patient testimonials from the EL-PFDD meeting. Using a Grounded Theory framework14, we qualitatively analyzed these responses.

RESULTS

The Our Voices survey was distributed to 114 pediatric patients/caregivers with PSC, of which there were 51 participants (response rate 44.7%). The majority of responses came from caregivers of pediatric patients with PSC (90%). Demographic characteristics of survey respondents are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of pediatric and caregiver survey respondents from the PSC Partners Patient Registry Our Voices survey.

| Characteristic | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| N | 51 |

| Who is the PSC patient? | |

| Self | 5 (10) |

| Child/Stepchild | 46 (90) |

| Age at time of survey | |

| Under 5 years | 1 (2) |

| 5-12 years | 16 (31) |

| 13-17 years | 34 (67) |

| Age at PSC diagnosis | |

| Under 5 years | 6 (12) |

| 5-12 years | 26 (51) |

| 13-17 years | 19 (37) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 23 (45) |

| Male | 28 (55) |

| Race | |

| White | 44 (86) |

| Asian | 1 (2) |

| Mixed | 3 (6) |

| Other/Not reported | 3 (6) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic, Non-Latino | 45 (88) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 6 (12) |

| Additional diseases/conditions | |

| Ulcerative Colitis | 28 (55) |

| Crohn’s Disease | 10 (20) |

| Autoimmune Hepatitis | 22 (43) |

| Other | 17 (33) |

| Medications for PSC | |

| Ursodeoxycholic acid | 36 (71) |

| Steroids | 7 (14) |

| Long-term antibiotics for cholangitis | 3 (6) |

| Vancomycin | 19 (37) |

| Clinical trial medications | 0 (0) |

| Medications for PSC symptom management | |

| Pain medications | 1 (2) |

| Itching medications | 6 (12) |

| Nausea/vomiting medications | 3 (6) |

| Antidepressants | 3 (6) |

| Fatigue medications | 0 (0) |

| Clinical trial medications | 0 (0) |

| Other | 3 (6) |

Abbreviations: PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Symptom Burden

Almost 70% of caregivers/children report that they experienced symptoms at the time of diagnosis. The most common symptoms caregivers/children reported included: fatigue (71%), abdominal pain (69%), anxiety (59%), appetite suppression (51%), insomnia (49%), and pruritus (45%). According to caregivers, the symptoms that most impacted how children felt and functioned included: fatigue (39%), loss of appetite (33%), pruritus (29%), nausea/vomiting (26%), and anxiety (22%). When experiencing symptoms at their worst, over half of caregivers/children reported that the pediatric patients were limited in their ability to do physically demanding/strenuous activities or work (67%), work/school duties (63%), social life activities (55%), and less physically demanding activities for fun or exercise (53%). Some caregivers/children also reported needing help completing activities of daily living including taking medications (28%), helping with home chores (26%), eating meals (24%), and showering/personal care (22%).

Patients and caregivers report various concerns about living with PSC. The most common concerns include “uncertainty (such as about healthcare insurance, or the unpredictability of disease progression, or difficulty making plans, or developing cancer, or developing other autoimmune diseases, or uncertainty about future health, or the constant uncertainty in life)” and “worries now or in the future (such as having an incurable disease, or needing a transplant, or not being able to get a transplant),” which about 75% of caregivers/children report feeling. Moreover, caregivers and children shared their concerns about the uncertainty surrounding PSC in their free-text survey responses and testimonials at the PFDD meeting:

“I have no definitive answer on my daughter’s health and life expectancy.”

“He lives with the uncertainty that comes along with PSC. He doesn’t know as healthy as he is today whether he’ll wake up tomorrow morning again fighting for his life.”

Clinical Trial Enrollment

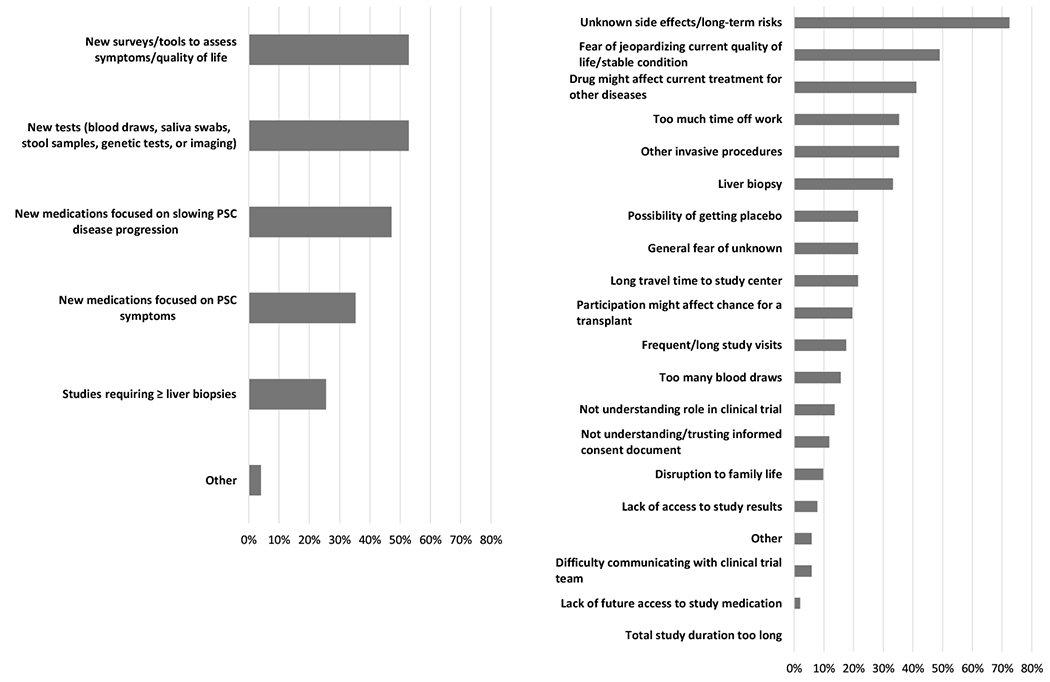

None of the caregivers/children reported currently or ever being involved in a clinical trial for new or investigational drugs for PSC. Only one caregiver/child (2%) reported ever being asked to be involved in a treatment-focused clinical trial. Most children (71%) had also never participated in other observational PSC studies. Overall, most caregivers/children (78%) reported that trials focused on interrupting PSC disease progression were most important to them. A smaller percentage reported that reducing their risk of cholangiocarcinoma (16%) and reducing symptom burden (2%) were most important. Figure 1a displays the reasons and types of clinical trials that children and their caretakers would be willing to participate in—the most common being “new surveys or tools to assess symptoms or QOL” (53%) and “new tests, which may involve blood draws, saliva swabs, stool samples, genetic tests, or imaging tests” (53%).

Figure 1.

a. Percent of children and caregivers who report they are willing to participate in the following types of clinical trials.

b. Most common reasons for not joining a clinical trial for children with PSC and their caregivers.

Percent of patients who reported the following concerns in their top 5 reasons for not joining a clinical trial

Barriers to Clinical Trial Enrollment

Patient/caregiver reported barriers to clinical trial enrollment included: unknown side effects or long-term risks (73%), “fear of jeopardizing current QOL and/or stable condition” (49%), “the possibility the drug might affect [their] current treatment for [their] other diseases” (41%), “too much time off school or work” (35%), and invasive procedures such as an endoscopy or colonoscopy (35%), and a liver biopsy (35%) (Figure 1b). Almost half of caregivers/children (49%) reported that they would turn to their hepatologist/gastroenterologist if they had questions about joining a clinical trial.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to expansively characterize patient/caregiver reported outcomes and barriers to clinical trial enrollment for pediatric PSC. This study demonstrates that PSC greatly impacts the QOL, functioning, and overall health of the children who live with it. Caregivers/children reported significant symptom burden, with symptoms prohibiting patients from participating in work/school activities, social life activities, and activities of daily living. Generally, the prevalence of the symptoms did not vary across those with concurrent conditions (e.g., autoimmune hepatitis, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)). However, none of the children or caregivers in our cohort report currently or ever participating in a PSC clinical trial for new or investigational treatments, despite a willingness to participate, underscoring the need for greater investment in developing and testing therapeutics for children living with PSC.

There are currently no approved or proven effective treatments or cure for the progression of PSC.1,7 Despite this, there remains a paucity of research studies directly aimed at pediatric PSC and improving symptoms and interrupting the natural history of the disease. In fact, as of 2024, there are only four actively recruiting pediatric PSC clinical trials focused on investigational treatments or testing modalities.15 That we see such a mismatch between those willing to participate in clinical trials and those actually participating, suggests that efforts should focus on increasing availability, accessibility, and knowledge of PSC clinical trials.

PSC has proven to be a difficult disease to study for a variety of reasons, with many drug trials failing to show convincing evidence of disease improvement or cure, and thus ending in the pilot phase.16 One reason for this is a lack of appropriate and measurable clinical endpoints.16 In the past, clinical endpoints assessing disease status included death, liver transplantation, cholangiocarcinoma, and cirrhosis.16 However, despite significant symptom burden and poor prognosis, the median transplant-free survival for patients with PSC is over 20 years, resulting in an annual rate of clinically relevant events of less than 4%.17 That said, caregivers/children in the Our Voices survey reported that, in addition to the outcomes mentioned above, endpoints such as symptom management, tools to assess quality-of-life, and reduction in symptom burden are important to patients as well. A potential therapeutic option that may help decrease symptom burden in patients is ileal bile acid transport (IBAT) inhibitors. IBAT inhibitors, which are used in other cholestatic conditions such as primary biliary cholangitis to decrease pruritus18, have recently been shown to be effective in managing pruritus in adult PSC19, but have never been studied in children with PSC. In line with the goals of the PSC Partners Patient Registry, future PSC research should focus on clinical endpoints that are important to patients and caregivers, and effort should be made to include pediatric patients in PSC clinical trials.

In designing pediatric PSC trials, we must account for patient/caregiver concerns about trial enrollment. In designing these trials, effort should be made to accommodate caregivers’ logistical concerns and minimize study appointments and the need for invasive procedures. Home visits or conducting some visits via telehealth are evolving strategies to address the logistical concerns that were raised in this survey. These concerns may be particularly salient for patients with low-income and economic marginalization as this group is often underrepresented among clinical trial participants.20 The need to take extra time off school or work may place undue burden on these individuals and disincentivize certain populations from participating in clinical trials. Finally, a large majority of caregivers/children (74%) report that they would not participate in trials requiring liver biopsies. Thus, less invasive ways to measure disease progression and treatment response should be considered in trial design.

This survey highlights the importance of trust for clinical trial enrollment, with around half of patients and caregivers reporting that they would turn to either their primary care physician or their gastroenterologist/hepatologist first if they had questions about participating in a clinical trial. Thus, one way to improve clinical trial participation and decrease patient concerns may be to strengthen partnerships between the trial team, the treating gastroenterologist/hepatologist, and the primary care physician. Another potential resource could be patient advocacy groups such as PSC Partners Seeking a Cure. Groups like PSC Partners strive to integrate the patient voice into clinical trial design and may act as a bridge between clinical trial teams, physicians, and patients while providing educational resources to patients wishing to join trials.

Strengths and Limitations

This study is not without limitations. First, this study includes a relatively small and homogeneous sample. Almost all (86%) participants identified as White, and there were no respondents who identified as Black. Future work should focus on increasing participation by marginalized communities. Second, the large majority of survey responses came from caregivers of pediatric patients rather than the patients themselves, which may not adequately capture the perspectives of the patients. However, this is a patient/caregiver-driven registry with important perspectives from PSC caregivers/children. Moreover, the use of both multiple choice and free text answers in the Our Voices survey also allows us to obtain data at a more granular level than chart reviews and non-patient driven registries. Third, there may be recall and non-response biases. For example, we observed that almost 40% of this cohort reported taking vancomycin. It is possible that patients and caregivers with more significant symptom burden or experiencing a concurrent diagnosis such as IBD have more interactions with the healthcare system, take more medications, and are, therefore, more likely to respond to the Our Voices survey. However, this is the largest registry of patient-reported outcomes in pediatric PSC, underscoring the need for future large-scale registries.

CONCLUSIONS

PSC is a chronic and understudied disease. The children/caregivers in this cohort report significant symptom burden, but none of these patients have ever participated in a PSC treatment-focused clinical trial. Future efforts should focus on increased funding for pediatric PSC-focused clinical trials, developing patient-centered clinical endpoints for PSC trials, and increasing the availability and accessibility of trials for pediatric PSC patients.

WHAT IS KNOWN

Primary sclerosing cholangitis is a chronic liver disease characterized by symptoms such as intractable pruritus, abdominal pain, fatigue, anxiety, and depression.

There are no effective or FDA-approved disease modifying therapies available for PSC.

WHAT IS NEW

Children with PSC experience significant symptom burden that negatively impacts their quality of life.

There is a paucity of research studies directly aimed at pediatric PSC and improving symptoms or interrupting the natural history of the disease.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Stephen Rossi, PharmD, for survey development support and Susan O’Dell, SM for data management and analytical support.

FUNDING/SUPPORT

UCSF Liver Center P30 DK026743 (SIW, JCL)

K23 K23DK132454 (SIW)

Bill Falik UCSF PSC Research Program (JCL, ML, SIW, HPS)

ROLE OF THE FUNDER/SPONSOR

The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition.

References:

- 1.Tabibian JH, Bowlus CL. Primary sclerosing cholangitis: A review and update. Liver Res. 2017;1(4):221–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stevens JP, Gupta NA. Recent Insights into Pediatric Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis. Clin Liver Dis. 2022;26(3):489–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaplan GG, Laupland KB, Butzner D, Urbanski SJ, Lee SS. The burden of large and small duct primary sclerosing cholangitis in adults and children: a population-based analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(5):1042–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marcus E, Stone P, Krooupa AM, Thorburn D, Vivat B. Quality of life in primary sclerosing cholangitis: a systematic review. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2021;19(1):100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marcus E, Stone P, Thorburn D, Walmsley M, Vivat B. Quality of life (QoL) for people with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC): a pragmatic strategy for identifying relevant QoL issues for rare disease. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2022;6(1):76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuo A, Gomel R, Safer R, Lindor KD, Everson GT, Bowlus CL. Characteristics and Outcomes Reported by Patients With Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis Through an Online Registry. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(7):1372–1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lazaridis KN, LaRusso NF. Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(12):1161–1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kemme S, Mack CL. Pediatric Autoimmune Liver Diseases: Autoimmune Hepatitis and Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2021;68(6):1293–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Montano-Loza AJ, Bhanji RA, Wasilenko S, Mason AL. Systematic review: recurrent autoimmune liver diseases after liver transplantation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45(4):485–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindkvist B, Benito de Valle M, Gullberg B, Björnsson E. Incidence and prevalence of primary sclerosing cholangitis in a defined adult population in Sweden. Hepatology. 2010;52(2):571–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weismüller TJ, Trivedi PJ, Bergquist A, et al. Patient Age, Sex, and Inflammatory Bowel Disease Phenotype Associate With Course of Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(8):1975–1984.e1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.PSC Partners Seeking a Cure Patient Registry. https://pscpartners.org/about/participate/patient-registry.html. Published 2023. Accessed 01/20, 2023.

- 13.Condition-Specific Meeting Reports and Other Information Related to Patients’ Experience. https://www.fda.gov/industry/prescription-drug-user-fee-amendments/condition-specific-meeting-reports-and-other-information-related-patients-experience. Published 2023. Accessed.

- 14.Chun Tie Y, Birks M, Francis K. Grounded theory research: A design framework for novice researchers. SAGE Open Med. 2019;7:2050312118822927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/search?cond=Primary%20Sclerosing%20Cholangitis&term=PSC,%20pediatric. Published 2024. Accessed 01/28, 2024.

- 16.Ponsioen CY. Endpoints in the design of clinical trials for primary sclerosing cholangitis. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2018;1864(4 Pt B):1410–1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boonstra K, Weersma RK, van Erpecum KJ, et al. Population-based epidemiology, malignancy risk, and outcome of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2013;58(6):2045–2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hegade VS, Kendrick SF, Dobbins RL, et al. BAT117213: Ileal bile acid transporter (IBAT) inhibition as a treatment for pruritus in primary biliary cirrhosis: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016;16(1):71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bowlus CL, Eksteen B, Cheung AC, et al. Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of maralixibat in adults with primary sclerosing cholangitis: Open-label pilot study. Hepatol Commun. 2023;7(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ford JG, Howerton MW, Lai GY, et al. Barriers to recruiting underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials: a systematic review. Cancer. 2008;112(2):228–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]