Abstract

Nucleotide excision repair (NER) is a major DNA repair system and hereditary defects in this system cause critical genetic diseases (e.g. xeroderma pigmentosum, Cockayne syndrome and trichothiodystrophy). Various proteins are involved in the eukaryotic NER system and undergo several post-translational modifications. Damaged DNA-binding protein 2 (DDB2) is a DNA damage recognition factor in the NER pathway. We previously demonstrated that DDB2 was SUMOylated in response to UV irradiation; however, its physiological roles remain unclear. We herein analysed several mutants and showed that the N-terminal tail of DDB2 was the target for SUMOylation; however, this region did not contain a consensus SUMOylation sequence. We found a SUMO-interacting motif (SIM) in the N-terminal tail that facilitated SUMOylation. The ubiquitination of a SUMOylation-deficient DDB2 SIM mutant was decreased, and its retention of chromatin was prolonged. The SIM mutant showed impaired NER, possibly due to a decline in the timely handover of the lesion site to XP complementation group C. These results suggest that the SUMOylation of DDB2 facilitates NER through enhancements in ubiquitination.

Keywords: DDB2, DNA damage response, nucleotide excision repair (NER), SUMOylation, ubiquitination

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Abbreviations

- NER

nucleotide excision repair

- DDB2

damaged DNA-binding protein 2

- SUMO

small ubiquitin-like modifier

- SIM

SUMO-interacting motif

- XP

xeroderma pigmentosum

- XPC

XP complementation group C

- CPDs

cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers

- 6–4 PPs

6–4 pyrimidine pyrimidone photoproducts

- PTMs

post-translational modifications

- PAR

poly(ADP-ribose)

- PIAS

protein inhibitor of activated STAT

- GG-NER

global genome NER

- RNAi

RNA interference

- CRISPR

clustered regularly interspaced palindromic repeat

- Cas

CRISPR-associated proteins

- FRAP

fluorescence recovery after photobleaching

DNA repair is an indispensable process that protects genomic integrity against DNA damage induced by environmental agents and DNA replication. Damaged DNA-binding protein 2 (DDB2) is a crucial protein for the detection of DNA lesions in nucleotide excision repair (NER). NER is a versatile DNA repair pathway that removes a wide variety of DNA lesions, such as UV-induced cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPDs), 6–4 pyrimidine pyrimidone photoproducts (6-4PPs), intrastrand cross-links and bulky base adducts (1). The eukaryotic NER system is a multistep process that recognizes DNA damage in the context of chromatin, removes single-stranded DNA containing lesions, synthesizes new fragments of DNA and ligates nicks. Xeroderma pigmentosum (XP) complementation group E cells lacking functional DDB2 are deficient in the repair of CPDs but competent in the repair of 6-4PPs at reduced rates (2, 3). However, a previous study demonstrated that DDB2 was not essential in an in vitro constituted NER system for the repair of naked DNA (4), suggesting that its role is restricted to the repair of UV-damaged DNA in the context of chromatin.

DDB2 participates in the recognition of UV-induced CPD as a subunit of the ubiquitin E3 ligase complex CRL4DDB2 (5, 6). The CRL4DDB2 complex ubiquitinates DDB2 itself and XP complementation group C (XPC) at damaged sites. The poly-ubiquitination of DDB2 reduces its affinity for damaged DNA, which promotes the subsequent recruitment of XPC for damage recognition and verification (7, 8). The CRL4DDB2 complex further ubiquitinates the XPC protein that accumulates at damaged sites, which enhance the binding of XPC to UV-damaged DNA (7). Moreover, this E3 ligase ubiquitinates histones H2A, H3 and H4, which may facilitate the removal of CPD from the chromatin structure (9, 10).

In addition to UV-dependent ubiquitination, DDB2 is subjected to several post-translational modifications (PTMs). DDB2 is modified by poly(ADP-ribose) (PAR) via poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 at DNA lesions (11). The PARylation of DDB2 regulates its stability as well as its retention on damaged chromatin, which facilitates CPD repair (11, 12). Furthermore, we found that DDB2 was SUMOylated in a UV-dependent manner and identified PIASy as its major SUMO E3 ligase (13).

SUMOylation regulates many cellular processes, such as transcription, replication, repair, and the cell cycle, by modulating specific protein–protein interactions (14, 15). SUMO is covalently attached to proteins through the ε-amino group of a specific lysine residue, which is in the consensus sequence ψKXE (ψ, large hydrophobic residue). The conjugation pathway of SUMO is similar to that of ubiquitin and includes a cascade of E1 (activation), E2 (conjugation) and E3 (ligase) enzymes. The SUMOylation of related proteins sometimes plays a crucial role in the repair process of damaged DNA. For example, Siz1 and Siz2, orthologues of mammalian PIAS family SUMO E3 ligases, are required for efficient global genome NER (GG-NER) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (16). In addition, we performed RNA interference (RNAi) screening on SUMO E3 ligases and found that PIAS1, PIASy and Pc2 were involved in the repair of UV-damaged DNA (17).

In this study, we showed functional interplay between the SUMOylation and ubiquitination of DDB2. A mutation analysis of DDB2 suggested that multiple lysines in the N-terminal region were SUMOylated in a UV-dependent manner and the SUMO-interacting motif (SIM) in this region facilitated this modification. We also demonstrated that DDB2 SUMOylation enhanced its ubiquitination and that the crosstalk of these PTMs was necessary for optimal NER activity.

Materials and Methods

Establishment of stably transformed cell lines

The cDNA encoding FLAG-DDB2 was inserted into the mammalian expression vector pcDNA4/TO/Myc-His (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Various mutations were introduced into DDB2 gene in this construct using site-directed mutagenesis. Plasmid DNAs were linearized and introduced into HeLa cells by Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Stable cell lines were selected by culturing cells in the presence of 100 μg/ml Zeocin (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Cell culture and UV irradiation

HeLa cells and their derivatives that stably expressed FLAG-tagged human DDB2 (HeLa/DDB2-WT), and DDB2 mutants were maintained in DMEM high glucose medium (SIGMA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin, and streptomycin.

To disrupt the endogenous DDB2 gene, electroporation was performed using NEPA21 (NEPAGENE). A total of 1 × 106 cells were electroporated with a ribonucleoprotein complex of 10 μg recombinant Cas9 (IDT, Integrated DNA Technologies) and 2.5 μg of IVT gRNA (target sequence in exon 1 of human DDB2 gene, 5′-GGGGCGUAAUACAAUCUCGGAGG-3′). Single colonies were isolated, and the knockout of DDB2 was checked by genome sequencing and Western blotting.

To induce photo lesions, exponentially growing cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and UV irradiated (20 J/m2) using a UV Crosslinker (CL-1000 Series, Analytik Jena AG). Cells were incubated in growth medium following UV exposure to allow the repair of DNA lesions for a defined period.

RNA interference

The double-strand siRNAs were synthesized by Hokkaido System Science. The sequences of sense strand used in the present study were as follows: siPIASy, 5′-UUCCGGAUCAACUCCACCUGUCUUG-3′; and siCUL4A, 5′-CAAGACCUGUUGGACUUCAAGGACA-3′. MISSION siRNA Universal Negative Control (SIGMA) was used as a control scramble siRNA. These siRNAs (40 nM) were transfected to half-confluent HeLa or HeLa/DDB2-WT cells using Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer’s instructions. UV (20 J/m2) was irradiated 48 h post-transfection.

Fractionation of nuclear proteins

Cells were washed twice with PBS, resuspended in hypotonic buffer (10 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.9, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl and protease inhibitor mixture (Protease Inhibitor Mixture, DMSO Solution for Mammalian Cell and Tissue Extracts, FUJIFILM Wako), vortexed to isolate nuclei and then centrifuged at 20,000×g at 4 °C for 10 s. Nuclear pellets were further extracted consecutively with increasing concentrations of NaCl (0.3, 0.5 and 2.0 M) in nuclear lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES–KOH pH 7.9, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA and the protease inhibitor mixture).

To collect the chromatin fraction, nuclear pellets were resuspended in nuclear lysis buffer containing 420 mM NaCl, and samples were centrifuged at 20,000 × g at 4 °C for 2 min. Pellets were collected as chromatin fractions and dissolved in 1 × SDS sample buffer (65 mM Tris–HCl pH 6.8, 3% SDS, 10% glycerol and 5% β-mercaptoethanol).

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

Immunoprecipitation was conducted under denaturing conditions to detect UV-induced SUMOylated DDB2. HeLa/DDB2-WT or HeLa/DDB2 mutant cells, into which SUMO1 and/or HA-Ub expression plasmids were introduced, were washed twice with PBS and resuspended in SDS lysis buffer (62.5 mM Tris–HCl pH 6.8, 10% glycerol, 2% SDS and 10 mM N-ethylmaleimide). Well mixed lysates were boiled to denature proteins and were then diluted 10-fold with RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 1% NP-40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM N-ethylmaleimide, 150 mM NaCl and the protease inhibitors mixture) followed by two rounds of sonication. After separating insoluble materials by centrifugation, an ANTI-FLAG M2 affinity gel (SIGMA) was added, and FLAG-associated immunoprecipitates were recovered, followed by denaturation in 1× SDS sample buffer. Proteins were detected by Western blotting with primary antibodies and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies. Rabbit anti-SUMO1 was prepared by immunizing rabbits with affinity purified GST-SUMO1. The antiserum was absorbed by GST-Sepharose to remove a GST reactive fraction, then purified with affinity chromatography with GST-SUMO1-immobilized Sepharose. The purified antibody was used as primary antibody at a concentration of 1 μg/ml. Rat anti-HA high affinity (Roche Diagnostics, 3F10, 1:1000), mouse anti-DYKDDDDK tag (FUJIFILM Wako, 1E6, 1:1000), mouse anti-His (MBL, MEDICAL & BIOLOGICAL LABORATORIES, 6C4, 1:1000), mouse anti-β-actin (MBL, 6D1, 1:1000), rabbit anti-PIASy (CST, Cell Signaling Technology, D2F12, 1:1000), rabbit anti-CUL4A (Bethyl Laboratories, A300739A, 1:1000), mouse anti-DDB2 (Abnova Corporation, 1F11, 1:1000), rabbit anti-DDB1 (CST, D4C8, 1:1000) and rabbit anti-XPC (Bethyl Laboratories, A301-122A, 1:1000) were used as primary antibodies. Anti-rat IgG, HRP-linked antibody (CST, #7077, 1:2000), anti-rabbit IgG (H + L chain), HRP-linked antibody (MBL, Code No. 458, 1:5000) and anti-mouse IgG (H + L chain) and HRP-linked antibody (MBL, Code No. 330, 1:5000) were used as secondary antibodies. The blot images were quantified with ImageJ software.

Protein purification and pulldown assay

His-SUMO1 and His-HA-ubiquitin were cloned into a pET15b (Novagen) vector and expressed in Escherichia coli (E. coli) strain Rosetta (DE3). The recombinant protein was purified on a TALON metal affinity resin (Clontech) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Fig. S1). CRL4DDB2 complexes were purified from HeLa/DDB2-WT or HeLa/DDB2-SIMm. These cells were washed twice with PBS and resuspended in the hypotonic buffer, and samples were then centrifuged at 20,000×g at 4 °C for 10 s. Pellets were resuspended in the RIPA buffer followed by two rounds of sonication. After separating insoluble materials by centrifugation, an ANTI-FLAG M2 affinity gel (SIGMA) was added, and FLAG-associated immunoprecipitates were washed with wash buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 1% NP-40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM N-ethylmaleimide and 500 mM NaCl). In the pulldown assay, recombinant His-SUMO1 was added and incubated with the CRL4DDB2 complexes on beads in binding buffer (20 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.9, 150 mM KCl and 0.025% Tween-20). The beads were washed three times and eluted in 1 × SDS sample buffer. Purified CRL4DDB2 complexes were confirmed by silver staining using Silver Stain II Kit Wako (FUJIFILM Wako), and pulldown samples were detected by Western blotting.

In vitro SUMOylation and ubiquitination assay

Regarding in vitro SUMOylation, purified CRL4DDB2 complexes on beads were incubated with 125 ng Aos1/Uba2 heterodimer (Enzo Life Sciences), 500 ng Ubc9 (Enzo Life Sciences), and 10 μg His-SUMO1 in 10 μL SUMO/ubiquitination buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT and 5 mM ATP) at 37 °C for 60 min. To detect the SUMOylation of DDB2, samples after the in vitro SUMOylation were immunoprecipitated by an ANTI-FLAG M2 affinity gel under denaturing conditions followed by Western blotting as described above.

Concerning in vitro ubiquitination, the CRL4DDB2 complex obtained with the in vitro SUMOylation reaction was washed on beads and incubated with 400 ng UBA1 (Boston Biochem), 1 μg UbcH5a (Boston Biochem) and 10 μg His-HA-ubiquitin in 20 μL SUMO/ubiquitination buffer. To detect the ubiquitination of DDB2, samples after the reaction were immunoprecipitated under denaturing conditions followed by Western blotting as described above.

ELISA

Genomic DNA was purified from mock-treated or UV-irradiated (5 J/m2) cells using the GenElute™ Mammalian Genomic DNA Miniprep Kit (SIGMA). DNAs (10 ng in PBS) were denatured and distributed to protamine sulfate-precoated 96-well assay plates (AGC Techno Glass), and plates were completely dried. Plates were then washed with PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20, followed by blocking with 2% FBS. After washing, an anti-CPD antibody (Cosmo Bio) diluted in PBS (1:1000) was distributed to each well, and plates were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. After washing, samples were incubated with the Biotin-F(ab’)2 fragment of anti-mouse IgG (H + L) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 1:10000) at 37 °C for 30 min, followed by an incubation with Peroxidase-Streptavidin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 1:10000). Captured CPDs were visualized using BD OptEIA™ Substrate Reagent A and B (BD Biosciences).

FRAP

In the fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) analysis, DDB2-knockout cells stably expressing eGFP-XPC were seeded onto 35-mm glass-bottomed dishes (AGC Techno Glass) and transiently transfected with mCherry-tagged DDB2-WT or DDB2-SIMm. FRAP imaging was performed using a confocal laser-scanning microscope (LSM 900, Carl-Zeiss) at 37 °C. mCherry-positive cells were selected and photobleached inside the nucleus by laser pulses at 488 nm (100% power, once capture). Thereafter, fluorescence recovery was monitored every 126 msec for 34 s. Fluorescent recovery was evaluated according to the published method (18).

Results

UV-induced DDB2 SUMOylation requires binding to damaged DNA

DDB2 is a DNA repair protein in GG-NER and is subjected to many types of PTMs, such as phosphorylation (19), ubiquitination (7, 20) and PARylation (11, 12). We also previously demonstrated that DDB2 was SUMOylated in a UV irradiation-dependent manner (13). In many cases, these PTMs are dependent on damaged DNA binding. Therefore, we herein investigated whether the interaction between DDB2 and damaged DNA was required for SUMOylation. To achieve this, we established HeLa cell lines that stably expressed FLAG-tagged wild-type DDB2 (DDB2-WT) or a DNA-binding deficient DDB2 mutant (DDB2-K244E) (21). These stable cells were UV irradiated and further cultured for 30 min followed by the immunoprecipitation of FLAG-tagged DDB2s and immunoblotting with an anti-SUMO1 antibody. The immunoprecipitation of denatured cell lysates revealed that DDB2 was SUMOylated in DDB2-WT stable cells, but to a markedly lesser extent in DDB2-K244E stable cells (Fig. S2). These results suggest that UV-induced DDB2 SUMOylation was dependent on binding to damaged DNA possibly in the context of chromatin.

DDB2 is SUMOylated at multiple sites in the N terminus

DDB2 does not contain any consensus amino acid sequences for SUMOylation sites (ψKXE). Therefore, to identify the target lysine residue(s) for SUMOylation, we divided the lysine residues of the DDB2 protein that localized at the surface of the CRLDDB2 complex into three groups based on its structure. DDB2 has a structurally disordered N-terminal tail and an intervening helix–loop–helix segment that interacts with DDB1, followed by a 7-bladed WD40 β-propeller domain (22). Group 1 had seven lysines (K4, K5, K11, K22, K35, K36 and K40) within the N-terminal tail, which were previously identified as primary targets for ubiquitination (23). Group 2 contained five lysines (K233, K242, K243, K268 and K278) that were on the surface of WD40 blades 3 and 4. Group 3 included nine lysines (K106, K144, K146, K151, K187, K309, K362, K381 and K427) in blades 1, 2 and 5–7. We established stable cell lines expressing mutant DDB2 with lysine-to-arginine substitutions at all seven group 1 lysines (DDB2-N7KR), at all group 2 lysines (DDB2-WD5KR) and at all group 3 lysines (DDB2-WD9KR). The expression levels of these mutants were similar to those of FLAG-tagged DDB2-WT (Fig. S3A). To establish whether these lysine residues were targets for SUMOylation in vivo, DDB2-WT and mutants were immunoprecipitated and analysed by immunoblotting with an anti-SUMO1 antibody. UV-dependent SUMOylation was observed with DDB2-WT; however, only a faint band was observed in the absence of UV irradiation. SUMOylated DDB2 decreased in the DDB2-N7KR mutant (Fig. 1A). In contrast, the two other mutants retained high levels of SUMOylation. This result showed that group 1 lysine residues contained major SUMOylation site(s). To examine SUMOylation in detail, we generated revertants of each lysine of DDB2-N7KR (DDB2-N6KR4K, DDB2-N6KR5K, DDB2-N6KR11K, DDB2-N6KR22K DDB2-N6KR35K, DDB2-N6KR36K and DDB2-N6KR40K), which contained only one lysine residue among seven residues substituted by arginine in the N-terminal tail. The expression levels of these mutants are shown in Fig. S3B. Among these mutants, DDB2-N6KR22K showed the recovery of SUMOylation (Fig. 1B). In addition, DDB2-N6KR35K and DDB2-N6KR40K showed bands of SUMO conjugates that were thinner than that of DDB2-N6KR22K (Fig. 1B). K5, K11, K35 and K40 were previously identified as major ubiquitination sites in the N terminus (23), suggesting that SUMOylation and ubiquitination sites partially overlap. Furthermore, although SUMOylation in a single lysine mutant (DDB2-K22R) decreased, this mutant was still SUMOylated at a low level (Fig. 1C). These results suggest the potential of multiple lysine residues as SUMO1 acceptors within the N-terminal tail of DDB2; however, K22 may be a major SUMOylation site.

Fig. 1.

DDB2 is SUMOylated at multiple sites in the N terminus. (A) Immunoprecipitation was conducted under denaturing conditions with HeLa cells stably expressing FLAG-tagged human DDB2-WT or lysine mutants exposed to UV light (20 J/m2). Cells were exposed to UV and then incubated for 30 min. (B, C) Immunoprecipitation was conducted under denaturing conditions with HeLa cells stably expressing the N-terminal lysine mutant or revertants. Lysine revertants of the N-terminal tail (B), and the K22R mutant of the major SUMOylation site (C). * indicates the immunoglobulin heavy chain. Representatives of three independent experiments are shown.

SUMOylation of DDB2 stimulates ubiquitination

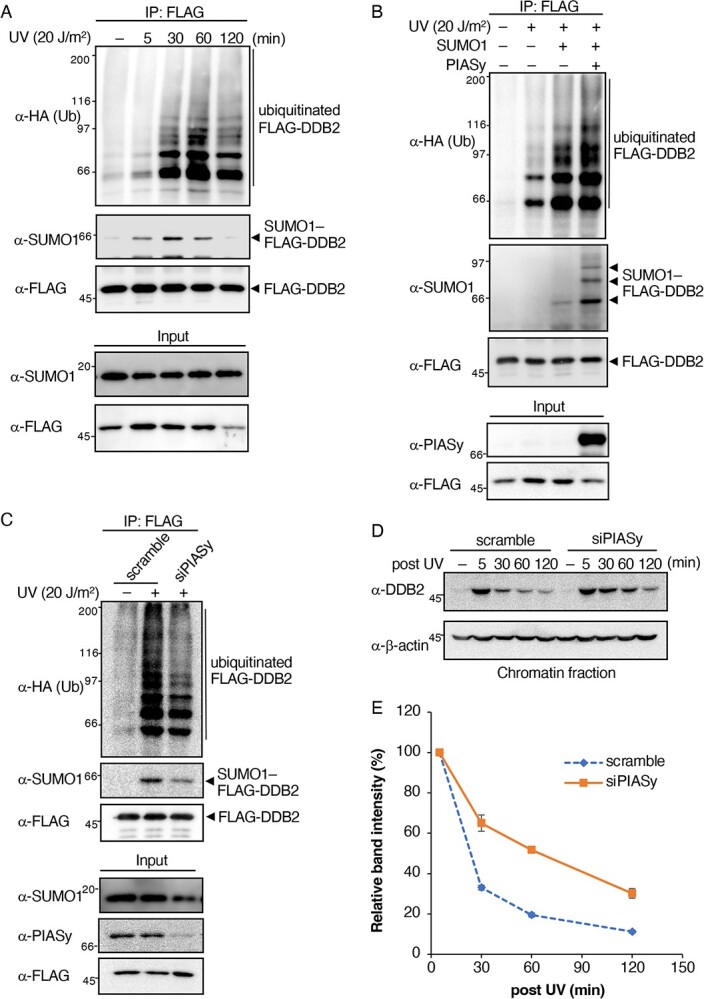

In the DDB2 molecule, K22 has been identified as a major SUMOylated site and nearby lysine residues in the N terminus are known to be ubiquitinated, which suggests an interaction between these PTMs. To examine the crosstalk between the SUMOylation and ubiquitination of DDB2, we initially investigated time-dependent changes in the amount of SUMO/ubiquitin-modified DDB2. To facilitate the detection of changes, SUMO1 and HA-tagged ubiquitin (HA-Ub) were co-transfected, followed by UV irradiation of stable cells expressing FLAG-tagged DDB2-WT, which were then incubated for a specified period. As shown in Fig. 2A, Western blotting using an anti-SUMO1 antibody detected a band of SUMO1-conjugated DDB2 in FLAG-associated immunoprecipitates. This band appeared immediately after UV irradiation (5 min). SUMOylation peaked approximately 30 minutes after irradiation, and SUMOylated DDB2 was not detected 120 minutes after irradiation. We observed that FLAG-DDB2 was SUMOylated in a similar manner without exogenously expressing SUMO1 (13). On the other hand, smear bands of poly-ubiquitinated DDB2 began to appear 30 minutes after UV irradiation, reached a maximum after approximately 60 minutes, and then decreased. Ubiquitinated DDB2 may subsequently be degraded. These results suggest that the N-terminal region of DDB2 underwent SUMOylation prior to ubiquitination. In addition, the depletion of CUL4A using siRNA, a key factor of the CRL4DDB2 ubiquitin ligase complex, inhibited DDB2 ubiquitination as expected, which did not suppress SUMOylation (Fig. S4). These results were consistent with DDB2 initially being SUMOylated upon UV irradiation and then undergoing ubiquitination.

Fig. 2.

SUMOylation of DDB2 stimulates ubiquitination. (A) SUMO1 and HA-Ub were co-transfected into HeLa/DDB2-WT cells. Cells were harvested 5, 30, 60 and 120 min after irradiation (20 J/m2). SUMO1- or ubiquitin-conjugated DDB2 was detected using the anti-SUMO1 or anti-HA antibody with FLAG-associated immunoprecipitates. (B, C) The expression vector (B) or siRNA (C) of PIASy was co-transfected with HA-Ub only or together with SUMO1 into HeLa/DDB2-WT, and cells were UV irradiated (20 J/m2) and then incubated for 30 min. Cells were then lysed and the lysate was immunoprecipitated with the anti-FLAG antibody, followed by Western blotting with the anti-SUMO1 or anti-HA antibody. (D) siRNA of PIASy was transfected into HeLa cells, and chromatin-bound endogenous DDB2 was then fractionated, followed by Western blotting with the anti-DDB2 antibody. β-actin was used as the loading control. (E) Relative amounts of chromatin-bound endogenous DDB2 were assessed from band intensities in (D), and plotted as a function of retention time after UV irradiation. The band intensities were normalized with those of β-actin. Means and standard errors were calculated from three independent experiments. Representatives of three independent experiments are shown in Fig. 2A–D.

These results prompted us to examine the requirement of SUMOylation for poly-ubiquitination. To achieve this, we attempted to detect changes in the amount of ubiquitin-conjugated DDB2 under different SUMOylation states by the overexpression or knockdown of PIASy, which we previously identified as a major SUMO E3 ligase for DDB2 (13). The overexpression of PIASy together with SUMO1 and HA-Ub led to an increase in SUMOylated DDB2 with multiple bands in the immunoprecipitation experiment (Fig. 2B). Based on their molecular masses, these bands appeared to be SUMO-modified DDB2 at multiple sites due to the ectopic expression of PIASy. The poly-ubiquitination level of DDB2 was higher in PIASy-overexpressing cells. Consistent with this result, the reduction in SUMOylation by the knockdown of PIASy with siRNA induced a decrease in poly-ubiquitination (Fig. 2C). In this experiment, a certain part of FLAG-DDB2 was SUMOylated, whereas PIASy was mostly depleted. Alternative minor SUMO E3 ligase(s) of DDB2 may contribute to this SUMOylation (13). These results strongly suggest that the SUMOylation of DDB2 upon UV irradiation was a precedence for ubiquitination.

The ubiquitination of DDB2 has been shown to dissociate DDB2 from UV-damaged chromatin (7, 8). Therefore, we examined the UV-induced dissociation of endogenous DDB2 in PIASy-knockdown cells. HeLa cells were transfected with scramble or PIASy siRNA followed by UV irradiation, and the amount of DDB2 in chromatin-bound fractions at various time points was analysed. In PIASy siRNA-transfected cells, the dissociation of DDB2 from chromatin appeared to be slower than that in scramble siRNA-transfected cells (Fig. 2D). The retention time of DDB2 was more than two-fold longer in PIASy-knockdown cells than in control cells (scramble siRNA) (Fig. 2E). Therefore, DDB2 SUMOylation appears to play important roles through its interaction with damaged chromatin via ubiquitination.

DDB2 SIM is important for SUMOylation

The overexpression and knockdown of PIASy suggested that SUMOylation of DDB2 facilitated ubiquitination and that this modification was required for the appropriate dissociation of DDB2 from chromatin. Since PIASy potentially functions as a SUMO E3 ligase to several other proteins, these results may have been attributed to the SUMOylation of lysine residues outside of the N-terminal region of DDB2 or those of other proteins involved in NER. Therefore, we attempted to generate a SUMOylation-deficient mutant to clarify the physiological role of DDB2 SUMOylation in the N-terminal tail. Since DDB2 lacks consensus sequences for SUMOylation, we speculated that SUMO-loaded Ubc9 was recruited to DDB2 via an interaction with the SIM of target proteins, which increased the modification of proximal lysine residues (24, 25). The GPS-SUMO software (26) predicted the presence of one SIM within the N-terminal tail of DDB2 (Fig. 3A). To establish whether DDB2 interacts with SUMO1 through the putative SIM, we performed a pulldown assay using the CRL4DDB2 complex containing either wild type or SIM mutated DDB2 (DDB2-SIMm), which were purified from the stable lines. Purified complexes were analysed by silver staining (Fig. S5A), which showed that the protein components between DDB2-WT and DDB2-SIMm did not significantly differ and also that the amounts of CUL4A and DDB1 in these complexes were similar (Fig. S5B). Recombinant His-SUMO1 was purified and incubated with CRL4DDB2 complex-bound FLAG beads, followed by the pulldown assay. As shown in Fig. 3B, His-SUMO1 was detected in the binding fraction of the DDB2-WT complex, but was reduced in the DDB2-SIMm complex, suggesting that SIM interacted with SUMO1. Since a non-negligible amount of SUMO1 bound to the CRL4DDB2 complex containing DDB2-SIMm, other proteins in the CRLDDB2 complex may have weakly interacted with SUMO1. The interaction was not confirmed with the purified N-terminal fragment of DDB2 expressed in E. coli (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

DDB2 SIM is important for its SUMO modification. (A) Amino acid sequences of SIM in the N-terminal region of DDB2 from various species and its substitution mutant. Core hydrophobic SIM residues are boxed. (B) Purified CRL4DDB2 complexes containing FLAG-tagged DDB2-WT or DDB2-SIMm were incubated with the recombinant SUMO1 protein and extensively washed. The bound SUMO1 protein was probed with the anti-His antibody. (C) Immunoprecipitation was conducted under denaturing conditions with HeLa cells stably expressing FLAG-tagged DDB2-WT or DDB2-SIMm. Cells were exposed to UV (20 J/m2) and then incubated for 30 min. (D) Scheme of the in vitro SUMOylation assay. Purified CRL4DDB2 complexes containing FLAG-tagged DDB2-WT or DDB2-SIMm were subjected to in vitro SUMOylation. (E) In vitro SUMOylation reactions were performed with CRL4DDB2 complexes. SUMOylated DDB2 was immunopurified from the complexes and subjected to Western blotting with the anti-SUMO1 antibody. * indicates the immunoglobulin heavy chain. Representatives of two (Fig. 3C) and three (Fig. 3B and E) independent experiments are shown.

To observe the SUMOylation state of this mutant, the lysates of the DDB2 cell lines were immunoprecipitated with an anti-FLAG antibody. SUMOylation was negligible in the immunoprecipitates of UV-irradiated DDB2-SIMm stable cells (Fig. 3C), suggesting that DDB2 was SUMOylated in a SIM-dependent manner. Furthermore, we analysed the SIM-dependent SUMOylation of DDB2 in vitro (Fig. 3D). Purified CRL4DDB2 complexes from DDB2-WT or DDB2-SIMm stable cells were subjected to in vitro SUMOylation, DDB2s were immunoprecipitated under denaturing conditions, and the degree of DDB2 SUMOylation was measured. The SUMOylation of DDB2-SIMm also decreased in vitro, although a low level of this modification was still observed (Fig. 3E). The reason for weak SUMOylation was not elucidated in this study. Collectively, these results showed that the SIM sequence in DDB2 facilitated its SUMOylation.

UV-induced DDB2 dissociation from chromatin is regulated by its SUMOylation states

The above results on the relationship between the SUMOylation and ubiquitination of DDB2 in vivo suggest that SUMOylation enhanced the poly-ubiquitination of DDB2. Therefore, we herein investigated whether DDB2 SUMOylation enhanced its poly-ubiquitination using an in vitro assay (Fig. 4A). Similar to the experiments shown in Fig. 3D, CRL4DDB2 complexes, including DDB2-WT or DDB2-SIMm, were immunopurified and subjected to in vitro SUMOylation. After washing, SUMOylated complexes on beads underwent an in vitro ubiquitination reaction in the presence of UBA1/UbcH5a as E1/E2 enzymes. In both DDB2-WT and DDB2-SIMm, the UBA1/UbcH5a-mediated poly-ubiquitination of DDB2 was detected at a low level without in vitro SUMOylation because the lysine residues of DDB2-SIMm remained intact. On the other hand, enhanced ubiquitination was only observed when DDB2-WT had been SUMOylated in vitro (Fig. 4B and C).

Fig. 4.

The CRL4 DDB2-dependent ubiquitination of DDB2 is stimulated by SUMOylation in vitro. (A) Scheme of in vitro SUMOylation/ubiquitination assays. Purified CRL4DDB2 complexes containing FLAG-tagged DDB2-WT or DDB2-SIMm were subjected to in vitro SUMOylation. Washed SUMOylation products subsequently underwent in vitro ubiquitination. (B) In vitro SUMOylation/ubiquitination reactions were performed with CRL4DDB2 complexes. Modified DDB2 after in vitro ubiquitination was immunopurified from the complexes and subjected to Western blotting with the anti-HA antibody. * indicates the immunoglobulin heavy chain. (C) Relative amounts of ubiquitinated DDB2 were assessed from band intensities in (B). The band intensities in the region containing ubiquitinated DDB2 (indicated by a bar in (B)) were quantified, and the intensity of SUMOylated DDB2-WT without ubiquitination reaction was subtracted as background. The band intensities were normalized with those of FLAG-DDB2. Means and standard errors were calculated from three independent experiments.

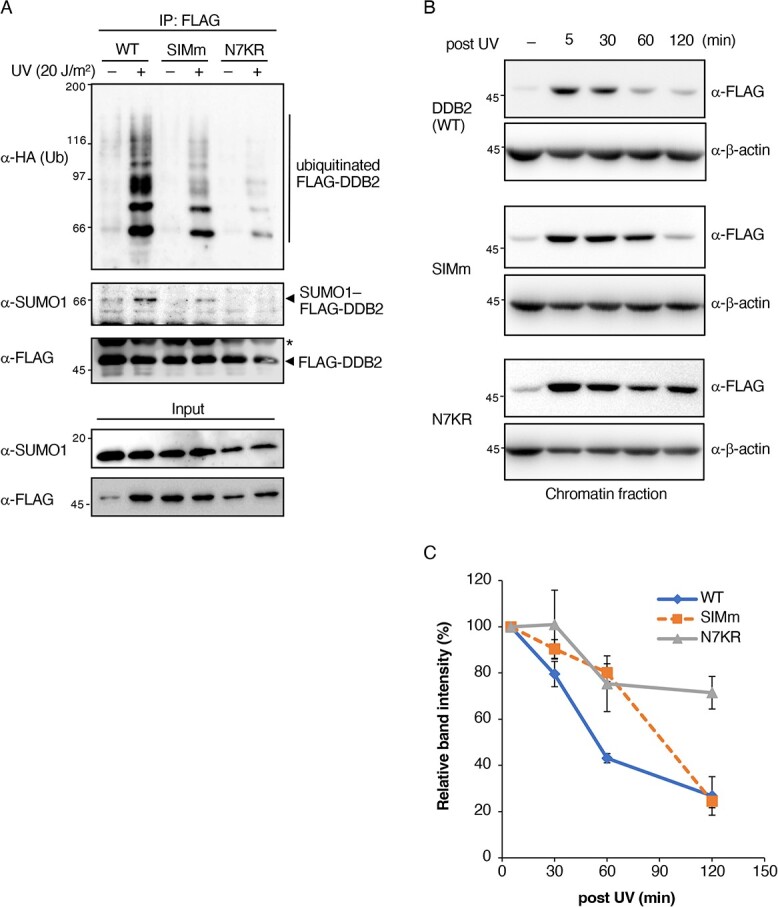

We then investigated the intracellular poly-ubiquitination levels of DDB2 mutants. In previous studies, the mutation or deletion of the N-terminal tail of DDB2 induced a significant decrease in ubiquitination and a delay in chromatin dissociation in vivo (8, 18). We confirmed these ubiquitination-related processes using DDB2-SIMm and DDB2-N7KR cell lines. The UV-induced ubiquitination of DDB2-SIMm was markedly lower than that of DDB2-WT. A certain degree of ubiquitination was observed with DDB2-SIMm, whereas that of DDB2-N7KR was negligible after UV irradiation due to the lack of major ubiquitination sites (Fig. 5A). We then examined the chromatin fractions separated from stable cells expressing these mutants or wild-type control cells at several time points (Fig. 5B). Upon UV irradiation, DDB2-WT was transiently associated with chromatin and then dissociated with time, whereas DDB2-N7KR remained bound, as previously reported (8). Furthermore, the dissociation kinetics of DDB2-SIMm showed an intermediate pattern between DDB2-WT and DDB2-N7KR, but DDB2-SIMm eventually disappeared from the chromatin fraction after 120 minutes (Fig. 5C). These results reconfirmed that N-terminal lysine residues were the main target of ubiquitination, which regulated its dissociation from chromatin, and also that SIM-dependent SUMOylation stimulated poly-ubiquitination in response to UV-induced DNA damage.

Fig. 5.

UV-induced DDB2 dissociation from chromatin is regulated by its SUMOylation state. (A) SUMO1 and HA-Ub were co-transfected into HeLa cells expressing DDB2-WT or SUMOylation-deficient DDB2 mutants. Cells were harvested 30 min after irradiation (20 J/m2). SUMO1- or ubiquitin-conjugated DDB2 was detected using the anti-SUMO1 or anti-HA antibody with FLAG-associated immunoprecipitates. * indicates the immunoglobulin heavy chain. Representatives of three independent experiments are shown. (B) HeLa cells stably expressing DDB2-WT or SUMOylation-deficient DDB2 mutants were irradiated with UV (20 J/m2) and harvested after 5, 30, 60, and 120 min. Chromatin-bound DDB2 was fractionated and subjected to Western blotting with the anti-FLAG antibody. Representatives of three independent experiments are shown. (C) Relative amounts of chromatin-bound DDB2-WT or mutants were assessed from band intensities in (B) and plotted as a function of retention time after UV irradiation. The band intensities were normalized with those of β-actin. Means and standard errors were calculated from three independent experiments.

DDB2 SIM is required for efficient NER

Recent studies revealed that the poly-ubiquitination of DDB2 was required for its dissociation from photolesions and the handover of damaged sites to XPC (8, 18, 27), which is a key process for the efficient progression of the NER reaction, particularly the repair of CPDs. To confirm whether the SUMOylation of DDB2 contributed to NER, we measured the repair rate of UV-induced CPDs. In this experiment, we generated DDB2-knockout cells using the CRISPR/Cas9 system and established rescued cell lines with DDB2-WT or DDB2-SIMm to exclude the effects of endogenous DDB2. The expression levels of rescued DDB2s were several-fold higher than those of endogenous DDB2 and were similar between rescued cell lines (Fig. 6A). The rescued cells expressing DDB2-SIMm showed decreased SUMOylation to those of DDB2-WT (Fig. S6). As expected from previous studies (13), DDB2-knockout cells lost most of their CPD repair capacity (Fig. 6B). The rescued cell line of DDB2-WT repaired CPDs more efficiently than original HeLa cells due to their higher expression levels. On the other hand, the DDB2-SIMm line showed a lower repair capacity than that of the rescued cell line of DDB2-WT (Fig. 6B). These results showed that DDB2 SIM and SIM-dependent SUMOylation were necessary for DDB2 to efficiently repair CPD lesions.

Fig. 6.

DDB2 SIM is required for efficient NER. (A) Expression of rescued DDB2 in DDB2-knockout (DDB2-KO) and rescued (WT rescue and SIMm rescue) cell lines detected by Western blotting. β-actin was used as the loading control. (B) Repair kinetics of UV-induced CPDs in DDB2-rescued cell lines (WT rescue and SIMm rescue). The remaining CPDs were detected at the indicated time points after UV irradiation. * indicates significant differences between DDB2-WT and DDB2-SIMm rescued cells by the unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test (P < 0.05). Mean values and standard errors were calculated from four independent experiments. (C) A FRAP analysis of eGFP-XPC, which was stably expressed in DDB2-KO. Cells were transfected with mCherry-tagged DDB2-WT or DDB2-SIMm, treated with mock or 20 J/m2 UV at 24 h post-transfection and subjected to FRAP within 30 min. After photobleaching, fluorescent recovery was monitored and plotted as a function of time. At least 20 cells were analysed for each condition. (D) Immobile fraction of eGFP-XPC in DDB2-KO stably expressing eGFP-XPC was calculated from the slope in (C). Fluorescent recovery was evaluated according to the published method (18). * indicates significant differences by the unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test (P < 0.05); NS, not significant.

We hypothesized that the decreased repair capacity of DDB2-SIMm is a disorder of DNA damage handover from DDB2 to XPC due to prolonged binding to damaged chromatin. To confirm this by a fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) analysis, we generated an eGFP-tagged XPC (eGFP-XPC) stable cell line based on DDB2-knockout cells (Fig. S7A). After confirming the expression and localization to the nucleus of eGFP-XPC (Fig. S7B), we measured the mobility of eGFP-XPC in cells transiently expressing mCherry-tagged DDB2-WT or DDB2-SIMm (Fig. 6C). The UV-induced immobilization of eGFP-XPC was higher in DDB2-WT than in DDB2-deficient cells (Fig. 6D). This is consistent with previous findings showing that DDB2 enhanced the UV-dependent immobilization of XPC (18, 28). In contrast, DDB2-SIMm did not significantly increase the immobile fraction of eGFP-XPC (Fig. 6D). These results support our hypothesis that a decrease in the ubiquitination of SUMO-deficient DDB2 impairs efficient handover to XPC, which lowers CPD repair activity.

Discussion

The present results demonstrated that a major SUMOylation site exists at the N terminus of DDB2; however, this does not exclude the existence of other SUMOylation sites. A mass spectrometric analysis of global SUMOylation in human cells revealed that K309 in human DDB2 is spontaneously SUMOylated (29). In addition, a previous study reported that among three computer-predicted SUMOylation sites, K309 underwent UV-dependent SUMOylation and SUMOylation of this residue is a key for CPD repair (30). The lysine residue corresponding to human K309 is conserved in cow but not in mouse or rat (Fig. S8). Furthermore, the DDB2-N7KR mutant showed a significant decrease in UV-dependent SUMOylation compared to DDB2-WD9KR that contained K309 mutation by our hand (Fig. 1A). From these, we analysed SUMOylation of N-terminal lysine residues in the present study. However, we could not rule out the possibility that SUMOylation at K309 facilitates CPD repair.

In the N-terminal tail of DDB2, we did not detect any consensus sequences for SUMOylation. According to the analysis by Hendriks et al. (29), approximately 50% of modifications by SUMO occur at non-consensus sites. Since the SUMO–SIM interaction is considered to play an important role in non-consensus SUMO modifications, we searched for SIM and identified a candidate sequence at the N terminus of DDB2. In pulldown experiments, the binding of SUMO1 to DDB2 through SIM was observed using the CRL4DDB2 complex containing DDB2-WT, and a weaker interaction was noted with DDB2-SIMm. The reduced affinity of DDB2-SIMm to SUMO1 may inhibit the SUMOylation of DDB2 in vivo and in vitro.

Since the SUMO–SIM interaction is generally weak (31, 32), other factors may affect the SUMO–SIM interaction of DDB2. For example, the phosphorylation of serine and threonine residue(s) adjacent to the hydrophobic core of the SIM sequence has been suggested to reinforce the SUMO–SIM interaction (32, 33). A previous study reported that serines 24 and 26 of the DDB2 N-terminal tail, which is adjacent to the identified SIM, are phosphorylated (34). Therefore, phosphorylation may affect the SUMOylation of DDB2 through the SUMO–SIM interaction.

In this study, we showed that DDB2 underwent UV-induced SUMOylation, and the modification enhanced its ubiquitination. So far, we have not found evidence that a single DDB2 molecule was SUMOylated and ubiquitinated simultaneously. For instance, the ubiquitinated DDB2 could not be detected with the anti-SUMO1. Although the mechanisms underlying the enhancement of ubiquitination in this study have not yet been elucidated, SUMO-dependent ubiquitination has been reported in many studies (35, 36). RNF4 and RNF111 are the most extensively studied members of the SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligase family of proteins that link SUMO and the ubiquitin pathway (37); however, these ligases mainly recognize poly-SUMOylation by SUMO2/3. In addition, BRCA1, a key player in DNA double-strand break repair, showed the conjugation of SUMO1, which enhanced its intrinsic E3 ubiquitin ligase activity as a BRCA1/BARD1 heterodimer (38). In another example, the transcription factor HIF-1α was modified by SUMO1 during hypoxia, which facilitated binding to the ubiquitin ligase von Hippel–Lindau protein, followed by degradation in a ubiquitination-dependent manner (39).

On the other hand, CRL4DDB2 E3 ligase activity was shown to be regulated by NEDD8 modifications (6, 23). The present results demonstrated that the SUMOylation of DDB2 promoted its ubiquitination by CRL4DDB2 E3 ligase in vivo and in vitro (Figs 4B and 5A). We did not investigate the relationship between the SUMOylation of DDB2 and this well-known regulation systems of CRL4DDB2.

SUMO and ubiquitin conjugations are frequently observed in the DNA damage response and play an essential role in its regulation (37, 40, 41). XPC is also regulated by dual ubiquitination systems by CRL4DDB2 and RNF111 in NER (42). The CRL4DDB2-mediated K48-linked ubiquitination of XPC enhances the recognition of damaged DNA. SUMO-dependent K63-linked ubiquitination by RNF111 subsequently promotes the release of XPC from damaged DNA and is required for the incorporation of NER endonucleases (XPG and ERCC1/XPF) into damaged sites. In addition, the SUMOylation-deficient mutant of XPC was shown to inhibit the recruitment of downstream repair factors and exhibited partially impaired NER activity (28, 43). In this study, the partial loss of NER activity was observed in SUMOylation-deficient DDB2-SIMm in the UV-induced CPD type of DNA damage (Fig. 6B). The poly-ubiquitination of DDB2 was found to decrease affinity to DNA lesions (7, 8), and stimulated its degradation (20, 23) and extraction from chromatin by p97/VCP segregase (18, 27), suggesting that the ubiquitination of DDB2 promotes damage handover. Since the retention of DDB2-SIMm on chromatin was prolonged in the present study (Fig. 5), the SUMOylation of DDB2 may control NER by regulating the handover to XPC via the promotion of ubiquitination. FRAP experiments using DDB2-knockout cells rescued with DDB2-WT or DDB2-SIMm demonstrated that the immobilization of eGFP-XPC decreased in DDB2-SIMm-expressing cells (Fig. 6C and D). This result suggests that the SUMOylation of DDB2 facilitated the handover of lesion sites to XPC.

An excess or shortage of the DDB2 protein causes genome instability and is harmful to cells (18); therefore, the amount of DDB2 needs to be strictly controlled. Different types of PTMs functionally cooperate in fine-tuning protein activity and abundance (14, 44–46). In this regard, it is important to note that DDB2, as well as DDB1, was subjected to PARylation upon UV irradiation, which affected the stability of DDB2 (11, 12), and the site of this modification was the lysine residue in the first 40 amino acids of the N-terminal region containing seven lysine residues. Therefore, four PTMs (SUMOylation, ubiquitination, phosphorylation and PARylation) occur in the narrow region of DDB2. Systematic analyses of crosstalk between the four PTMs are important for obtaining further insights into the initial step of NER, including the recognition of damaged sites.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. S. Kiyonaka (Department of Biomolecular Engineering, Graduate School of Engineering, Nagoya University) for the use of LSM 900 and kind discussion.

Contributor Information

Hidenori Kaneoka, Department of Biomolecular Engineering, Graduate School of Engineering, Nagoya University, Furo-cho, Chikusa-ku, Nagoya 464-8603, Japan.

Kazuhiko Arakawa, Department of Biomolecular Engineering, Graduate School of Engineering, Nagoya University, Furo-cho, Chikusa-ku, Nagoya 464-8603, Japan.

Yusuke Masuda, Department of Biomolecular Engineering, Graduate School of Engineering, Nagoya University, Furo-cho, Chikusa-ku, Nagoya 464-8603, Japan.

Daiki Ogawa, Department of Biomolecular Engineering, Graduate School of Engineering, Nagoya University, Furo-cho, Chikusa-ku, Nagoya 464-8603, Japan.

Kota Sugimoto, Department of Biomolecular Engineering, Graduate School of Engineering, Nagoya University, Furo-cho, Chikusa-ku, Nagoya 464-8603, Japan.

Risako Fukata, Department of Biomolecular Engineering, Graduate School of Engineering, Nagoya University, Furo-cho, Chikusa-ku, Nagoya 464-8603, Japan.

Maasa Tsuge-Shoji, Department of Biomolecular Engineering, Graduate School of Engineering, Nagoya University, Furo-cho, Chikusa-ku, Nagoya 464-8603, Japan.

Ken-ichi Nishijima, Department of Biomolecular Engineering, Graduate School of Engineering, Nagoya University, Furo-cho, Chikusa-ku, Nagoya 464-8603, Japan.

Shinji Iijima, Department of Biomolecular Engineering, Graduate School of Engineering, Nagoya University, Furo-cho, Chikusa-ku, Nagoya 464-8603, Japan.

Funding

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI grant (17H06157 and 20K05226).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Data Availability

All data that support the results of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Tang, J. and Chu, G. (2002) Xeroderma pigmentosum complementation group E and UV-damaged DNA-binding protein. DNA Repair (Amst) 1, 601–616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hwang, B.J., Ford, J.M., Hanawalt, P.C., and Chu, G. (1999) Expression of the p48 xeroderma pigmentosum gene is p53-dependent and is involved in global genomic repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 424–428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moser, J., Volker, M., Kool, H., Alekseev, S., Vrieling, H., Yasui, A., Van Zeeland, A.A., and Mullenders, L.H.F. (2005) The UV-damaged DNA binding protein mediates efficient targeting of the nucleotide excision repair complex to UV-induced photo lesions. DNA Repair (Amst) 4, 571–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aboussekhra, A., Biggerstaff, M., Shivji, M.K.K., Vilpo, J.A., Moncollin, V., Podust, V.N., Protić, M., Hübscher, U., Egly, J.M., and Wood, R.D. (1995) Mammalian DNA nucleotide excision repair reconstituted with purified protein components. Cell 80, 859–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shiyanov, P., Nag, A., and Raychaudhuri, P. (1999) Cullin 4A associates with the UV-damaged DNA-binding protein DDB. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 35309–35312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Groisman, R., Polanowska, J., Kuraoka, I., Sawada, J.I., Saijo, M., Drapkin, R., Kisselev, A.F., Tanaka, K., and Nakatani, Y. (2003) The ubiquitin ligase activity in the DDB2 and CSA complexes is differentially regulated by the COP9 signalosome in response to DNA damage. Cell 113, 357–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sugasawa, K., Okuda, Y., Saijo, M., Nishi, R., Matsuda, N., Chu, G., Mori, T., Iwai, S., Tanaka, K., Tanaka, K., and Hanaoka, F. (2005) UV-induced ubiquitylation of XPC protein mediated by UV-DDB-ubiquitin ligase complex. Cell 121, 387–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Matsumoto, S., Fischer, E.S., Yasuda, T., Dohmae, N., Iwai, S., Mori, T., Nishi, R., Yoshino, K.I., Sakai, W., Hanaoka, F., Thomä, N.H., and Sugasawa, K. (2015) Functional regulation of the DNA damage-recognition factor DDB2 by ubiquitination and interaction with xeroderma pigmentosum group C protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 1700–1713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kapetanaki, M.G., Guerrero-Santoro, J., Bisi, D.C., Hsieh, C.L., Rapić-Otrin, V., and Levine, A.S. (2006) The DDB1-CUL4ADDB2 ubiquitin ligase is deficient in xeroderma pigmentosum group E and targets histone H2A at UV-damaged DNA sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 2588–2593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang, H., Zhai, L., Xu, J., Joo, H.Y., Jackson, S., Erdjument-Bromage, H., Tempst, P., Xiong, Y., and Zhang, Y. (2006) Histone H3 and H4 ubiquitylation by the CUL4-DDB-ROC1 ubiquitin ligase facilitates cellular response to DNA damage. Mol. Cell 22, 383–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Robu, M., Shah, R.G., Petitclerc, N., Brind’amour, J., Kandan-Kulangara, F., and Shah, G.M. (2013) Role of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 in the removal of UV-induced DNA lesions by nucleotide excision repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 1658–1663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pines, A., Vrouwe, M.G., Marteijn, J.A., Typas, D., Luijsterburg, M.S., Cansoy, M., Hensbergen, P., Deelder, A., de Groot, A., Matsumoto, S., Sugasawa, K., Thoma, N., Vermeulen, W., Vrieling, H., and Mullenders, L. (2012) PARP1 promotes nucleotide excision repair through DDB2 stabilization and recruitment of ALC1. J. Cell Biol. 199, 235–249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tsuge, M., Masuda, Y., Kaneoka, H., Kidani, S., Miyake, K., and Iijima, S. (2013) SUMOylation of damaged DNA-binding protein DDB2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 438, 26–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gareau, J.R. and Lima, C.D. (2010) The SUMO pathway: emerging mechanisms that shape specificity, conjugation and recognition. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 861–871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Johnson, E.S. (2004) Protein modification by SUMO. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73, 355–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Silver, H.R., Nissley, J.A., Reed, S.H., Hou, Y.M., and Johnson, E.S. (2011) A role for SUMO in nucleotide excision repair. DNA Repair (Amst) 10, 1243–1251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tsuge, M., Kaneoka, H., Masuda, Y., Ito, H., Miyake, K., and Iijima, S. (2015) Implication of SUMO E3 ligases in nucleotide excision repair. Cytotechnology 67, 681–687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ribeiro-Silva, C., Sabatella, M., Helfricht, A., Marteijn, J.A., Theil, A.F., Vermeulen, W., and Lans, H. (2020) Ubiquitin and TFIIH-stimulated DDB2 dissociation drives DNA damage handover in nucleotide excision repair. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhao, Q., Barakat, B.M., Qin, S., Ray, A., El-Mahdy, M.A., Wani, G., Arafa, E.S., Mir, S.N., Wang, Q.E., and Wani, A.A. (2008) The p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase augments nucleotide excision repair by mediating DDB2 degradation and chromatin relaxation. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 32553–32561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. El-Mahd, M.A., Zhu, Q., Wang, Q.E., Wani, G., Prætorius-Ibba, M., and Wani, A.A. (2006) Cullin 4A-mediated proteolysis of DDB2 protein at DNA damage sites regulates in vivo lesion recognition by XPC. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 13404–13411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shiyanov, P., Hayes, S.A., Donepudi, M., Nichols, A.F., Linn, S., Slagle, B.L., and Raychaudhuri, P. (1999) The naturally occurring mutants of DDB are impaired in stimulating nuclear import of the p125 subunit and E2F1-activated transcription. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 4935–4943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Scrima, A., Koníčková, R., Czyzewski, B.K., Kawasaki, Y., Jeffrey, P.D., Groisman, R., Nakatani, Y., Iwai, S., Pavletich, N.P., and Thomä, N.H. (2008) Structural basis of UV DNA-damage recognition by the DDB1-DDB2 complex. Cell 135, 1213–1223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fischer, E.S., Scrima, A., Böhm, K., Matsumoto, S., Lingaraju, G.M., Faty, M., Yasuda, T., Cavadini, S., Wakasugi, M., Hanaoka, F., Iwai, S., Gut, H., Sugasawa, K., and Thomä, N.H. (2011) The molecular basis of CRL4DDB2/CSA ubiquitin ligase architecture, targeting, and activation. Cell 147, 1024–1039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Knipscheer, P., Flotho, A., Klug, H., Olsen, J.V., van Dijk, W.J., Fish, A., Johnson, E.S., Mann, M., Sixma, T.K., and Pichler, A. (2008) Ubc9 sumoylation regulates SUMO target discrimination. Mol. Cell 31, 371–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Flotho, A. and Melchior, F. (2013) Sumoylation: a regulatory protein modification in health and disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 82, 357–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhao, Q., Xie, Y., Zheng, Y., Jiang, S., Liu, W., Mu, W., Liu, Z., Zhao, Y., Xue, Y., and Ren, J. (2014) GPS-SUMO: A tool for the prediction of sumoylation sites and SUMO-interaction motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, W325–W330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Puumalainen, M.R., Lessel, D., Rüthemann, P., Kaczmarek, N., Bachmann, K., Ramadan, K., and Naegeli, H. (2014) Chromatin retention of DNA damage sensors DDB2 and XPC through loss of p97 segregase causes genotoxicity. Nat. Commun. 5, 3695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Akita, M., Tak, Y.S., Shimura, T., Matsumoto, S., Okuda-Shimizu, Y., Shimizu, Y., Nishi, R., Saitoh, H., Iwai, S., Mori, T., Ikura, T., Sakai, W., Hanaoka, F., and Sugasawa, K. (2015) SUMOylation of xeroderma pigmentosum group C protein regulates DNA damage recognition during nucleotide excision repair. Sci. Rep. 5, 1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hendriks, I.A., D’Souza, R.C.J., Yang, B., Verlaan-De Vries, M., Mann, M., and Vertegaal, A.C.O. (2014) Uncovering global SUMOylation signaling networks in a site-specific manner. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 21, 927–936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Han, C., Zhao, R., Kroger, J., He, J., Wani, G., Wang, Q.E., and Wani, A.A. (2017) UV radiation-induced SUMOylation of DDB2 regulates nucleotide excision repair. Carcinogenesis 38, 976–985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hicke, L., Schubert, H.L., and Hill, C.P. (2005) Ubiquitin-binding domains. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 610–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hecker, C.M., Rabiller, M., Haglund, K., Bayer, P., and Dikic, I. (2006) Specification of SUMO1- and SUMO2-interacting motifs. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 16117–16127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Stehmeier, P. and Muller, S. (2009) phospho-regulated sumo interaction modules connect the SUMO system to CK2 signaling. Mol. Cell 33, 400–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Olsen, J.V., Blagoev, B., Gnad, F., Macek, B., Kumar, C., Mortensen, P., and Mann, M. (2006) Global, in vivo, and site-specific phosphorylation dynamics in signaling networks. Cell 127, 635–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Praefcke, G.J.K., Hofmann, K., and Dohmen, R.J. (2012) SUMO playing tag with ubiquitin. Trends Biochem. Sci. 37, 23–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jackson, S.P. and Durocher, D. (2013) Regulation of DNA damage responses by ubiquitin and SUMO. Mol. Cell 49, 795–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chang, Y.C., Oram, M.K., and Bielinsky, A.K. (2021) Sumo-targeted ubiquitin ligases and their functions in maintaining genome stability. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 5391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Morris, J.R., Boutell, C., Keppler, M., Densham, R., Weekes, D., Alamshah, A., Butler, L., Galanty, Y., Pangon, L., Kiuchi, T., Ng, T., and Solomon, E. (2009) The SUMO modification pathway is involved in the BRCA1 response to genotoxic stress. Nature 462, 886–890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cheng, J., Kang, X., Zhang, S., and Yeh, E.T.H. (2007) SUMO-specific protease 1 is essential for stabilization of HIF1α during hypoxia. Cell 131, 584–595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Schwertman, P., Bekker-Jensen, S., and Mailand, N. (2016) Regulation of DNA double-strand break repair by ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like modifiers. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 17, 379–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rüthemann, P., Pogliano, C.B., and Naegeli, H. (2016) Global-genome nucleotide excision repair controlled by ubiquitin/Sumo modifiers. Front. Genet. 7, 1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Poulsen, S.L., Hansen, R.K., Wagner, S.A., van Cuijk, L., van Belle, G.J., Streicher, W., Wikström, M., Choudhary, C., Houtsmuller, A.B., Marteijn, J.A., Bekker-Jensen, S., and Mailand, N. (2013) RNF111/Arkadia is a SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligase that facilitates the DNA damage response. J. Cell Biol. 201, 797–807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Van Cuijk, L., Van Belle, G.J., Turkyilmaz, Y., Poulsen, S.L., Janssens, R.C., Theil, A.F., Sabatella, M., Lans, H., Mailand, N., Houtsmuller, A.B., Vermeulen, W., and Marteijn, J.A. (2015) SUMO and ubiquitin-dependent XPC exchange drives nucleotide excision repair. Nat. Commun. 6, 7499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Perry, J.J.P., Tainer, J.A., and Boddy, M.N. (2008) A SIM-ultaneous role for SUMO and ubiquitin. Trends Biochem. Sci. 33, 201–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hoege, C., Pfander, B., Moldovan, G.L., Pyrowolakis, G., and Jentsch, S. (2002) RAD6-dependent DNA repair is linked to modification of PCNA by ubiquitin and SUMO. Nature 419, 135–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hunter, T. (2007) The age of crosstalk: phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and beyond. Mol. Cell 28, 730–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data that support the results of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.