ABSTRACT

Lipid droplets (LDs) are highly specialized energy storage organelles involved in the maintenance of lipid homoeostasis by regulating lipid flux within white adipose tissue (WAT). The physiological function of adipocytes and LDs can be compromised by mutations in several genes, leading to NEFA-induced lipotoxicity, which ultimately manifests as metabolic complications, predominantly in the form of dyslipidemia, ectopic fat accumulation, and insulin resistance. In this review, we delineate the effects of mutations and deficiencies in genes — CIDEC, PPARG, BSCL2, AGPAT2, PLIN1, LIPE, LMNA, CAV1, CEACAM1, and INSR — involved in lipid droplet metabolism and their associated pathophysiological impairments, highlighting their roles in the development of lipodystrophies and metabolic dysfunction.

KEYWORDS: Lipid droplet formation, adipogenesis, lipid droplet hydrolysis, lipodystrophy, insulin resistance

Introduction

Lipid droplets (LDs) are specialized cellular organelles that act as reservoirs for neutral lipids within white adipose tissue (WAT) which serves as the body’s primary site of long-term energy storage [1,2]. In fact, the structural organization of WAT is highly adapted to accommodate a single large unilocular lipid droplet which occupies most of the adipocyte’s intracellular volume, allowing for space-efficient energy storage and facilitating thereby the sequestration and mobilization of triacylglycerols (TAGs) in response to metabolic demands [3,4]. Lipid droplet-associated proteins (LD-proteins) occupy a pivotal role in the metabolism of lipids whereby they mediate key lipogenic and lipolytic processes pertaining to unilocular LD formation in adipocytes or non-esterified fatty acid (NEFA) release in the context of positive and negative energy balance, respectively (Figure 1) [7–10]. Aberrant fat partitioning, whether due to defective lipid droplet biogenesis or hydrolysis, can result in elevated levels of circulating NEFAs. The process of excess NEFA accumulation in extra-adipose tissues has been strongly implicated in the pathogenesis of several metabolic diseases characterized by the disruption of whole-body energy homoeostasis [11–14]. Accordingly, the ability of adipocytes to compartmentalize and sequester lipids in unilocular droplets is critical in preventing the detrimental metabolic effects of NEFA-induced lipotoxicity [15,16]. Moreover, the importance of LDs’ NEFA-buffering capacity in the maintenance of lipid homoeostasis is evident in both lipodystrophic and obese patients, wherein lipoatrophy and excessive lipid overflow, respectively, conduce to adipocyte dysfunction, ectopic lipid accumulation, and insulin resistance [17–20]. To truly appreciate the extensive clinical implications, as well as the distinct pathophysiological mechanisms of adipose tissue-associated metabolic phenotypes, we herein investigate a battery of genes whose involvement in lipodystrophies, compromised lipid droplet metabolism, and ensuing comorbidities has been well established in the literature. Mutations in the loci hereunder engender various classes of defects pertaining to lipid droplet formation and fat storage in adipocytes (CIDEC, PPARG, BSCL2, AGPAT2), lipid droplet hydrolysis and fat-store mobilization (PLIN1, LIPE), nuclear protein function (i.e., laminopathic lipodystrophies) (LMNA), and insulin clearance and insulin receptor downstream signalling (CAV1, CEACAM1, INSR), all of which impact lipid droplet physiology and consequently disrupt whole body energy homoeostasis. Examining the functional aberrations in the lipid droplet proteome that contribute to such metabolic disturbances not only allows to delineate the pathophysiological mechanisms of these disorders but also paves the way for identifying and developing targeted molecular therapies.

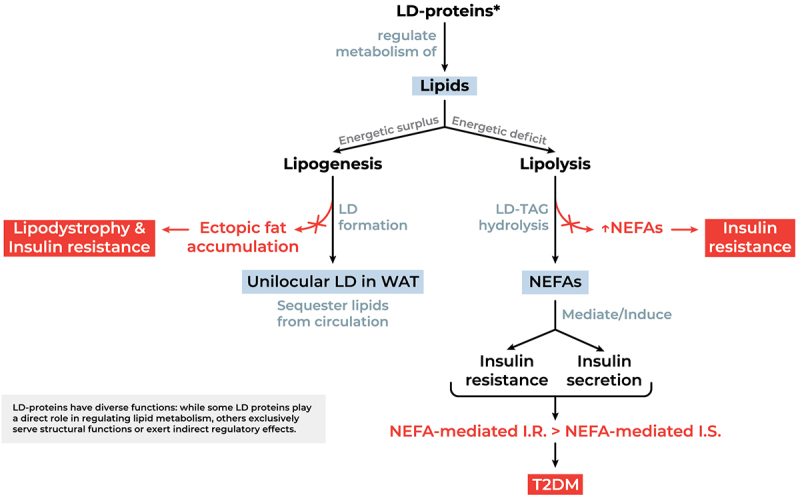

Figure 1.

Functional significance of LD-proteins in lipid metabolism and potential aberrations. NEFAs mediate insulin resistance by hindering insulin-induced glucose uptake and glycogen synthesis. Simultaneously, NEFAs drive glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. This nuance is crucial, as it implies that insulin resistance would not necessarily lead to diabetes as long as NEFA-mediated insulin secretion is able to compensate for NEFA-induced insulin resistance [5,6]. Abbreviations: I.R., insulin resistance; I.S., insulin secretion; LD, lipid droplet; LD-proteins, lipid droplet associated proteins; NEFA, non-esterified (free) fatty acids (plasma-circulating); T2DM, type 2 diabetes Mellitus; TAG, Triacylglycerol; WAT, white adipose tissue.

Impaired lipid droplet formation and fat storage in adipocytes

Cell death-inducing DFFA-like effector C (CIDEC)

The cell death-inducing DNA fragmentation factor-α-like effector (CIDE) “family of” proteins, originally recognized for their putative pro-apoptotic role due to sequence homology with CIDE-N domain proteins that interact with DNA fragmentation factor 45 (DFF45), are now understood as important regulators of lipid homoeostasis [21–23]. This paradigm shift has uncovered the physiological significance of CIDEA, CIDEB, and CIDEC (also known as fat-specific protein 27, Fsp27 in mice) proteins in lipid metabolism that had been hitherto elusive. Despite the unique role of each CIDE protein, contingent on tissue-specific expression and intracellular localization, the literature concurs on the profound regulatory effect they exert on the formation and functional dynamics of lipid droplets in adipocytes [23]. In this section, we shed light on recent advancements in the knowledge pertaining to CIDEC-facilitated mechanisms of lipid storage processes, highlighting its importance in cellular energy homoeostasis and its potential implication in obesity-associated phenotypes and ensuing complications.

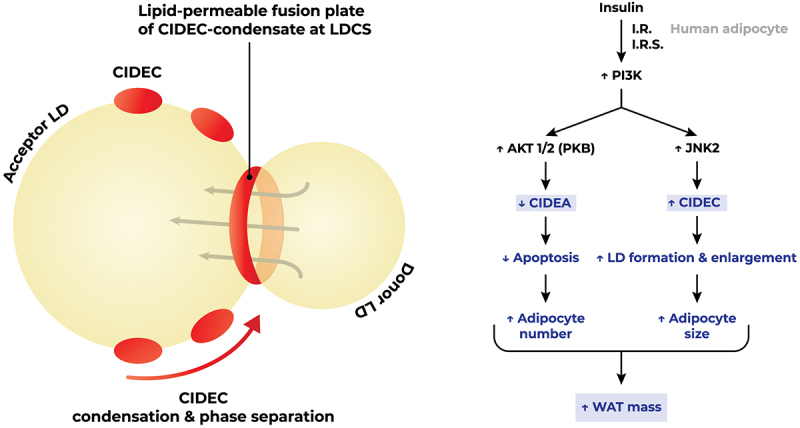

Lyu et al. described the mechanism whereby CIDEC mediates LD fusion occurring at LD contact sites (LDCS) as it undergoes gel-like phase separation. The interaction of CIDEC’s N-terminus induces its condensation, forming dynamic lipid-permeable fusion plates acting as passageways that facilitate the flux of lipids from a donor LD into an acceptor, typically larger, LD [24]. The characteristic ‘unilocular’ phenotype of mature white adipocytes, which allows for more efficient fat storage, is promoted by CIDEC-mediated mechanism of lipid exchange that facilitates the fusion and enlargement of adipocytes. The homodimerization of CIDEC’s CIDE-N domain is crucial for its activity. However, PLIN1 can rescue the function of homodimerization-defective CIDEC mutants by forming a heterodimer with the CIDE-N domain, acting as a co-factor. PLIN1 has been documented to activate CIDEC in adipocytes, enhancing lipid transfer and unilocular LD formation through this interaction. Consequently, PLIN1 serves as an adipocyte-specific activator of CIDEC’s function [25]. The function of CIDEC is also governed by an insulin-dependent regulatory network. The proposed differential regulation model of CIDEA and CIDEC expression posits that upon insulin binding to its, PI3K induces the phosphorylation of downstream Akt and JNK2. The JNK2-induced upregulation of CIDEC expression, which is instrumental in LD formation and enlargement, coupled with the Akt-mediated downregulation of CIDEA expression, which curtails adipocyte apoptosis, trigger adipocyte hyperplasia and hypertrophy, respectively [26,27]. This ultimately conduces to an overall increase in the mass of white adipose tissue (WAT) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Insulin signalling triggers lipid droplet fusion. Insulin-induced anti-apoptosis and lipid droplet formation by differential regulation of CIDEA and CIDEC via Akt1/2 and JNK2-dependent pathways, respectively, in human adipocytes. CIDEC mediates lipid droplet fusion via gel-like condensation on lipid droplet cell surface. Figure readapted from [24] and [26]. Abbreviations: AKT/PKB, protein kinase B; I.R., insulin receptor; I.R.S., insulin receptor substrate; JNK2, c-Jun N-terminal kinase 2; LD, lipid droplet; LDCS, lipid droplet contact site; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; WAT, white adipose tissue.

Aberrations in CIDEC’s expression resulting in impaired CIDEC-mediated LD biogenesis and compromised fatty acid partitioning are tethered to a plethora of metabolic diseases whose hallmarks are insulin resistance and ectopic fat deposition along with the comorbidities appertaining [28,29]. In a preliminary case study, Rubio-Cabezas et al. documented the association of a homozygous nonsense mutation at the CIDEC locus with the occurrence of insulin-resistant diabetes and partial lipodystrophy. Histological analysis of the patient’s adipocytes and functional evaluation of the aberrant protein revealed the following: multi-loculated LDs, increased mitochondrial count, small lipid droplet size, and a failure of the protein to localize around LDs. These observations are reconciled in ratification of CIDEC’s role in optimum lipid storage in WAT and unilocular LD formation [30]. Interestingly, Cidec knockout mice share a phenotype similar to that of the patient, characterized by the accumulation of multiloculated lipid droplets in epididymal and subcutaneous WAT and increased mitochondrial biogenesis. However, these mice are leaner than their wild-type counterparts, protected from high-fat diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance, and exhibit augmented energy expenditure [31]. In fact, CIDEC has been found to correlate with the occurrence of obesity as it is up regulated in the hepatocytes and WAT of ob/ob mice. Moreover, Cidec knockout mice have lower levels of plasma Triglyceride content and circulating free fatty acids. The abrogation of Cidec expression in these mice induces a remarkable increase in mitochondrial size and function in their WAT, which acquires Brown Adipose Tissue (BAT)-like properties, demonstrated by the upregulation of BAT-specific proteins and transcriptional regulators (FoxC2, PPAR and PGC1α) and the downregulation of BAT-differentiation suppressors (Rb, p107 and RIP140) [32].

However, the work of Puri et al. indicates that CIDEC’s expression in WAT is a positive correlate of insulin sensitivity in obese humans. It is suggested that the enhanced storage of TAGs, sustained by the optimal function of CIDEC in LD formation, decreases ectopic fat accumulation and non-esterified fatty acids (NEFAs) in circulation which are common in obesity and lipodystrophic phenotypes, thereby deterring the onset of insulin resistance. Consequently, CIDEC plays a pivotal role in the metabolism of adipocytes and optimal TAG storage in LDs. Conversely, disruption of normal CIDEC function may result in lipodystrophy and associated comorbidities [33]. Moreover, adipose tissue-specific ablation of Cidec expression in mice using the Cre/LoxP system conduces to ectopic fat deposition promoted by an enhanced lipolytic rate and impaired LD storage, the overflow of lipids deposits in extra-adipose organs, notably the liver. Despite their resistance to HFD-induced weight gain, these mice exhibit marked hepatosteatosis, elevated serum TAGs and NEFAs, and systemic insulin resistance upon high-fat diet administration, underscoring the importance of CIDEC in the sequestration of excess lipids to prevent the development of systemic insulin resistance mediated by ectopic fat accumulation [34]. In further corroboration of these observations, human CIDEC transgenic mice are afforded protection against high fat diet-induced insulin resistance and display decreased NEFAs in circulation in comparison to mutated human CIDEC transgenic mice with a truncated variant of the protein [35]. These findings, therefore, demonstrate that CIDEC is crucial in regulating lipolytic activity and maintaining glucose homoeostasis. Other findings suggest that CIDEC regulates the lipolytic activity of adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL), thereby, restricting the hydrolysis of TAGs and the subsequent release of NEFAs via sequestration of comparative gene identification-58 (CGI-58), an activator of TAG hydrolases [36].

CIDEC is essential for optimal TAG storage in LDs, regulation of ATGL-mediated lipolysis and circulating NEFAs, and the consequent counteraction of NEFA-mediated insulin resistance, thus promoting LDs’ insulin-sensitive phenotype. Nonetheless, the differential metabolic outcomes of tissue-specific versus constitutive CIDEC ablation are noteworthy. This variation suggests distinct physiological roles for CIDEC depending on its expression context which warrants the need for further investigation to elucidate its extensive impact on adipocyte metabolism and its collateral implication on insulin-sensitive tissues.

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARG)

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARG) gene encodes for two isoforms of PPAR gamma protein: PPARγ1 and PPARγ2. PPARγ1 is expressed in various cell types including adipose tissue, colon, liver, heart, skeletal muscle while PPARγ2 is expressed almost exclusively in adipose tissue [37]. PPARγ is a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily of ligand-activated transcription factors that plays a critical role in adipocyte differentiation, survival and function, as well as in lipid metabolism, and insulin sensitivity [38]. Genetic variants of the PPARG gene, associated with altered PPARγ transcriptional activity, are documented to conduce to varied metabolic disturbances, including lipodystrophy, obesity, and type 2 diabetes [39]. In fact, significantly lower PPARγ levels observed in obese individuals and T2DM patients emphasize its significance in glucose and lipid metabolism, wherein impairments constitute the stepping stone for insulin resistance and broad-range metabolic dysfunction [40].

The recognition of PPARγ as a master adipogenic regulator is closely tied to the discovery of thiazolidinediones (TZDs), a class of potent synthetic insulin-sensitizing drugs that act as high-affinity PPARγ ligands [41]. PPARγ activation induces systemic insulin sensitization by potentiating a series of complex metabolic events involving multiple organs. Its activation enhances TAG storage and lipid uptake in adipocytes, thereby sequestering circulating NEFAs and preventing their accumulation in extra-adipose organs. Moreover, this curbs intra-adipose pro-inflammatory M1 macrophage polarization, resulting in an enhanced adipose tissue immunological phenotype and a consequently improved metabolic function. Furthermore, PPARγ activation increases peripheral glucose uptake and suppresses hepatic gluconeogenesis. Altogether, the orchestration of these metabolic circuits by PPARγ improves adipocyte function, glycaemic control, insulin sensitivity, and contributes to the maintenance of whole-body energy homoeostasis. Despite their certain efficacy as anti-hyperglycaemic agents, TZDs’ clinical use is curtailed due to risks of cardiovascular adverse events, fluid retention, bone loss and weight gain [42]. Ongoing research is devoted to improving our understanding of the role of PPARγ signalling in health and metabolic disease and to develop safer PPARγ agonists.

The compelling evidence of PPARγ’s importance in adipose tissue function and glucose homoeostasis is brought forth by genetic mutations and polymorphisms at the PPARG locus. The substitution of alanine for proline in PPARG at codon 12 (Pro12Ala), for instance, is associated with a decreased risk of diabetes development in individuals carrying the variant [43]. PPARγΔ5, a naturally occurring splice isoform has been documented to exert a dominant-negative effect on the canonical PPARγ receptor disrupting its function and its ability to promote adipocyte differentiation in precursor cells. Moreover, the expression of the PPARγΔ5 variant is higher in subcutaneous adipose tissue of obese and diabetic or overweight patients correlating positively with their BMI [44]. Barroso et al. described two heterozygous mutations, P467L and V290M, in the ligand-binding domain of PPARγ in three different subjects. Crystallographic analysis revealed that the two missense mutations destabilize the C-terminal alpha helix which mediates the transactivation of the receptor, resulting in the impairment of its transcriptional activity. Moreover, the mutant alleles suppress the activity of its coexpressed wild-type counterpart, indicating a dominant-negative effect. The patients carrying these variants present with severe insulin resistance and develop diabetes mellitus and hypertension at a remarkably early age [45]. Shortly thereafter, two other heterozygous mutations, R425C and F388L, occurring in the ligand-binding domain of PPARγ were identified in patients presenting a typical pattern of partial lipodystrophy coupled to insulin resistance [46,47]. This lipodystrophic phenotype was also reported by Savage and colleagues in individuals bearing the P467L variant which are characterized by scarce limb and gluteal fat and normal subcutaneous and visceral fat deposition. These patients display fasting hyperinsulinemia, acanthosis nigricans, hepatic steatosis, and dysregulated adipose tissue metabolism, which fails to entrap postprandial NEFAs, along with markedly low circulating adiponectin levels [48]. Interestingly, heterozygosity for a frameshift/premature stop codon mutation ([A553ΔAAAiT]fs.185[stop186]) in the DNA binding domain of PPARγ leading to impairment of DNA binding and transcriptional activity is not associated with the development of insulin resistance in carriers, however double heterozygous mutants at this locus and the PPP1R3A locus encoding the muscle-specific regulatory subunit of protein phosphatase 1 exhibit extreme insulin resistance [49]. These findings highlight the interplay between two unrelated defective loci involved in lipid and carbohydrate metabolism that converge to produce a phenotype of severe metabolic abnormality. The panel of mutations at the PPARG locus has been further expanded by Agostini et al. who identified lipodystrophic insulin-resistant patients harbouring (C114R, C131Y, C162W, R357X, [A935ΔC]fs.312[stop315]) variants of the gene that abrogate the function of the wild type receptor through a dominant-negative non-DNA binding mechanism [50]. Schuermans et al. identified a homozygous loss of function mutation in WAT-expressed phospholipid-modifying enzyme PLAAT3 resulting in diminished PPARγ-mediated adipogenesis in seven unrelated patients who suffered from a joint lipodystrophic and neurodegenerative syndrome [51]. PPARG dominant-negative mutations are now collectively recognized as a cause of Familial Partial Lipodystrophy Type 3 (FPLD3), providing a monogenic model for studying the pathophysiology of metabolic syndrome [52]. Metreleptin, a recombinant analog of human leptin, has been effective in people with lipodystrophy [53]. Lambadiari et al. presented in their case report a 61-year-old woman who had been diagnosed with FPLD3. This patient’s extreme hypertriglyceridaemia was improved after six months of treatment with metreleptin. They reported a dramatic decrease in the patient’s fasting plasma triglycerides and HbA1c from 2912 mg/dl to 198 mg/dl and from 10% to 7.9%, respectively [54]. While Leptin administration serves as a viable therapeutic regimen to mitigate metabolic disturbances in lipodystrophic patients, it is nonetheless imperative to address the root cause of PPARγ insufficiency and its contribution to metabolic syndrome.

In vitro and in vivo PPARG knockout and overexpression models further corroborate the significance of this locus in adipogenesis and metabolic homoeostasis. Preliminary in vitro studies demonstrated that PPARγ’s expression is induced during adipocyte differentiation which premised its regulatory role in adipogenesis [55]. Interestingly, the ectopic expression of PPARG in fibroblasts, lacking the adipogenic transcription factor C/EBPα, is sufficient to drive their differentiation into adipocytes, whereas retroviral delivery of C/EBPα in PPARγ-deficient murine embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) fails to produce the same effect [56–59]. These findings position PPARγ as a proximal effector and master regulator of adipogenesis whose expression is both sufficient and obligatory to stimulate the adipogenic program. It is pertinent to note, however, that although PPARγ is indispensable for adipogenic differentiation, C/EBPα is a requisite effector in the maintenance of insulin sensitive adipocytes. This illustrates the regulatory network that governs adipocyte formation and function, while PPARγ orchestrates the initiation of adipogenesis, C/EBPα ensures their proper metabolic function. The model emerging from these findings has ascertained the complementary role of these two transcription factors that interact through a positive regulatory loop: ligand-activation of PPARγ promotes the expression of C/EBPα which, in turn, enhances the expression of PPARγ. In tandem, they collaborate to produce mature adipocytes endowed with an insulin-sensitive phenotype [60].

Several murine Pparg genetic models also lend themselves to study the ensuing phenotypes and metabolic abnormalities in insulin-sensitive tissues resulting from the disruption of this locus. Zhang et al. reported that PPARγ2 knockout (PPARγ2KO) mice exhibit a markedly reduced WAT mass. The WAT of these mice displays histomorphological alterations and appears heterogeneous and smaller in size upon macroscopic examination compared to their wild-type counterparts, indicative of diminished TAG accumulation. This is coupled to a decrease in leptin and adiponectin levels and a significant reduction in the expression of adipogenesis-related genes in WAT of these mice compared to controls. Moreover, PPARγ2KO mice are protected from high-fat diet-induced obesity. Interestingly, exogenous insulin administration to male but not female PPARγ2KO mice, fails to reduce their blood sugar levels, alluding to potential sexual dimorphisms and the potential involvement of a compensatory estrogen-signalling pathway. Insulin resistance in male PPARγ2KO mice was rescued by PPARγ agonist rosiglitazone treatment. The molecular mechanism underlying these metabolic disturbances is associated with a reduction in IRS1 and GLUT 4 expression in liver, skeletal muscle, and WAT, suggesting that the absence of PPARγ2 impairs insulin-signalling and insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in peripheral organs. In vitro transfection of MEFs isolated from PPARγ2KO mice with wild-type PPARγ2 cDNA restores their adipogenic potential [61]. Pparg null mice, however, present placental defects and consequently die in utero. The fusion of tetraploid cells from wild-type Pparg+/+ embryos with Pparg-null embryos, to bypass placental insufficiency, resulted in a single live-born pup which presented a severe lipodystrophic phenotype marked by the complete absence of WAT and BAT [62]. Surprisingly, partial Pparg deficiency (Pparg+/-) confers mice protection from high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance due to the reduction of their adipocyte size which renders them more sensitive to insulin [63,64].

Tissue-specific disruption of PPARγ’s expression has improved much of our understanding of TZDs’ mode of action and the distinct metabolic phenotypes produced by its expression, or rather lack thereof, in various tissues. Cre-LoxP generated Adipose tissue-specific PpargKO mice exhibit progressive lipoatrophy, hepatosteasosis and hepatic insulin resistance, and hyperlipidaemia. However, skeletal muscle of these mice, despite accumulating TAGs, do not develop insulin resistance [65]. These findings suggest that not only is PPARγ critical in adipogenesis, but it is also necessary in maintaining adipocyte survival and function as the deletion is induced only after adipogenesis has occurred unlike Pparg null models, which fail to produce fat depots altogether. Charrier et al. mirrored Pparg deficiency in mice by developing an adipose tissue-specific Zinc finger protein 407 (ZFP407) knockout (AZKO) model, targeting a positive regulator of Pparg’s expression. AZKO mice have reduced fat mass and adipogenesis-related gene expression consistent with partial lipodystrophic phenotypes [66]. Skeletal muscle-targeted disruption of PPARγ results in progressive insulin resistance and a dramatic reduction in insulin-stimulated glucose disposal rate, as well as secondary adipose-tissue and hepatic insulin resistance. TZD treatment lowered circulating FFA in these mice, but did not ameliorate skeletal muscle’s insulin sensitivity. However, TZD administration improved the liver and adipose tissue’s response to insulin [67]. These findings highlight a critical role for PPARγ in the responsiveness of skeletal muscles to insulin stimulation. Moreover, these results demonstrate that the systemic insulin-sensitizing effects of TZDs are not solely achieved through adipose tissue PPARγ activation and that PPARγ occupies a crucial glucoregulatory function in skeletal muscles, wherein impairments result in severe systemic insulin resistance. Liver-specific Pparg deletion in wild-type mice leads to progressive obesity, dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance with age. Moreover, liver-targeted Pparg ablation in ob/ob leptin-deficient mice alleviates fatty liver but aggravates hyperglycaemia and insulin resistance. Additionally, lipoatrophic AZIP mice with Pparg-deficient livers exhibit reduced hepatic steatosis at the expense of an increased hyperlipidaemia, compromised triglyceride clearance, and exacerbated muscle insulin resistance [68,69]. Taken together, these findings suggest that liver PPARγ is crucial for triglyceride homoeostasis and systemic insulin sensitivity through preventing extra-hepatic fat accumulation, despite its pro-steatotic role in lipoatrophic and leptin-deficient phenotypes.

The generation of simultaneous tissue-specific Pparg knockout models would not only enhance our understanding of the aetiology and pathophysiology of metabolic syndrome, but would also give us greater insight into the therapeutic mechanisms of TZDs in relation to their effects on PPARγ’s relevance and activity in different insulin-sensitive tissues. Moreover, the adumbration of these findings not only consolidates the status of PPARγ as a master regulator of adipogenesis, but also underscores its significance in coordinating whole-body metabolic homoeostasis by accommodating the influx of NEFAs in WAT.

BSCL2 lipid droplet biogenesis associated, seipin (BSCL2)

SEIPIN, an integral membrane protein encoded by the BSCL2 gene localizes to the endoplasmic reticulum where it is instrumental in LD biogenesis. Recent structural works have unravelled breakthrough mechanistic insights pertaining to SEIPIN’s role in LD formation and maturation and its consequent significance on lipid and metabolic homoeostasis [70].

Topological analysis revealed that SEIPIN possesses 2 transmembrane regions, a conserved loop that resides within the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum, and two N-terminal and C-terminal domains found in the cytoplasm [71]. As triglycerides and sterol esters accrue into the nascent lipid droplet forming between the ER leaflets, SEIPIN undergoes structural rearrangements and interacts with various cellular components to facilitate this process. Understanding the precise mechanisms through which SEIPIN influences these processes is therefore crucial for elucidating its role in LD formation [70]. For instance, SEIPIN has been demonstrated to interact with the adaptor protein 14-3-3β of significance in adipocyte cytoskeletal organization, indicating an essential role in processes required for LD expansion as well as adipocyte development such as maintaining cell shape, mobility, and intracellular transport pathways [72]. Moreover, SEIPIN exerts a regulatory function on cytosolic calcium influx into the ER lumen via its direct interaction with the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2±ATPase (SERCA) to promote fat storage in adipose tissue [73]. Each monomeric constituent of SEIPIN’s undecameric structure contains two critical subunits for lipid droplet formation. The first is an eight-stranded beta-sandwich fold in its ER luminal domain, which helps SEIPIN bind to lipids, most prominently phosphatidic acid. This binding occurs through both its head group and acyl chains [74]. The second part is a hydrophobic helix present in mammals and insects but absent in yeast, where its activity is compensated by another protein. This domain interacts with DAGs and TAGs, sequestering these neutral lipids to promote nucleation and growth of lipid droplets. Thus, SEIPIN gathers and organizes lipids in the endoplasmic reticulum, concentrating them to ensure proper lipid droplet formation and TAG storage [75–77]. The role of SEIPIN in maintaining stable oligomeric complexes is critical. However, some mutations disrupt oligomerization and by that lead to altered LD morphology and function [74]. SEIPIN’s interaction with neutral lipids via their acyl chain carboxyl esters facilitates TAG accumulation and organization in LDs. SEIPIN’s luminal domain binds neutral lipids such as TAGs and sterol esters through specific residues via hydrogen bonding. SEIPIN also binds free fatty acids and squalenes, though less efficiently due to the absence of carboxyl esters. We can therefore infer that SEIPIN is more specific towards neutral lipids than phospholipids [78]. During lipid droplet biogenesis, SEIPIN localizes to the ER-LD contact sites, stabilizing these sites and reducing their mobility. Thereby, efficient lipid partitioning is ensured due to the stable association of lipid droplets with the ER. Upon SEIPIN depletion, the structure formed at the ER-LD contact site is lost, and by that the formation of several small lipid droplets ensues. The absence of SEIPIN results in disproportional LD growth caused by defective lipid transfer between the ER and the LD due to premature recruitment of Rab18 that is usually prevented by SEIPIN. Accordingly, smaller lipid droplets would shrink, and larger lipid droplets would grow heterogeneously. Thus, SEIPIN ensures efficient lipid storage and prevents the destabilization and excessive nucleation of tiny lipid droplets [79]. Further research focuses on the mechanisms that allow lipid droplets to mature from their nascent stage aided by SEIPIN’s interaction with enzymes involved in lipid synthesis and other proteins required for lipid droplet development. Upon reaching a critical mass, TAGs synthesized in the ER by lipid synthesis enzymes, such as DGAT1, then undergo phase separation and bud from the ER as iLDs. It is suggested that SEIPIN aids in iLD formation, wherein it engages with nascent LDs to facilitate their growth via transfer of additional neutral lipids so to promote their maturation [80]. Studies about SEIPIN’s evolutionarily conserved transmembrane segments underscore their necessity for LD biogenesis. The conserved structure of SEIPIN’s key structural components across species, including the α/β-sandwich fold domain, indicates that these segments might aid in triglyceride phase separation and LD growth. Per the molecular model of SEIPIN’s function during LD formation, TAGs can interact with one another in the SEIPIN cage formed in the ER because it creates an environment with fewer phospholipids. Diffusion of TAGs into the complex can occur via membrane gaps between SEIPIN monomers. The transmembrane segments undergo spatial rearrangements to accommodate the expanding LDs. In fact, the transmembrane segments prompt TAG phase separation upon binding it. SEIPIN oligomers expand towards the cytoplasm as the TAG lens grows where SEIPIN induces the release of the nascent LD bud. Despite some mutations, like R178A, causing minimal disruption, other mutations in the switch region result in SEIPIN complexes that are unable to keep a constricted neck at the ER-LD junction. Rather, they separate and incorporate more seipin subunits, creating ring formations with a huge diameter encircling LDs, profoundly affecting lipid metabolism [81]. Moreover, the transmembrane segments help create an environment in the SEIPIN complex that facilitates lipid droplet formation by stabilizing the ER-LD neck structure and promoting regulated triglyceride transfer. In fact, SEIPIN’s nucleation of triglycerides initially begins by hydrophilic interactions between TAG moieties and SEIPIN residues, along with hydrophobic interactions between TAGs and SEIPIN’s transmembrane segments. These interactions direct lipid coalescence, preserve the shape of the ER-LD neck, and assist in the transport of lipids and proteins from the ER to the LD, further establishing SEIPIN’s critical role in lipid droplet biogenesis and maintenance [82]. SEIPIN’s involvement in protein localization from the ER bilayer to the LD monolayer has also been investigated. Early targeting proteins transit through LD assembly complexes (LDACs), while late targeting proteins transit through established membrane bridges that connect the ER with mature lipid droplets. The function of seipin in forming an oligomeric ring structure at the LDAC in the endoplasmic reticulum imparts selective and controlled access, restricting the access of some late-targeting proteins while allowing early-targeting proteins necessary for newly formed lipid droplets. This, in turn, prevents overcrowding and unneeded protein incorporation during early lipid droplet formation. Thus, seipin acts as a negative regulator of some cargoes during the early formation of lipid droplets [83].

The impairment of SEIPIN-mediated processes of lipid coalescence and lipid droplet formation due to mutations at the BSCL2 locus result in a lipodystrophic phenotype concomitant with severe metabolic disturbances, further highlighting the significance of this locus in lipid homoeostasis as evidenced by SEIPIN-deficient experimental models presenting morphogenic aberrations and defective maturation of lipid droplets. BSCL2 mutation-induced Berardinelli-Seip Congenital Lipodystrophy (BSCL) is a rare autosomal recessive disease. BSCL is classified as the most severe form of lipodystrophy which manifests as a massive absence of adipose tissue, severe insulin resistance, hepatic steatosis, as well as high triglyceride levels [84]. Analogous to the human BSCL phenotype, Bscl2−/− mice present with an almost complete absence of adipose tissue, insulin resistance and hepatosteatosis. Unlike humans, Bscl2−/− mice are, however, hypotriglyceridemic, a consequence attributed to their increased hepatic NEFA uptake, which explains the subsequent development of severe liver steatosis in these mice. Pioglitazone administration to Bscl2-deficient mice mitigates lipoatrophy and increases leptin and adiponectin levels, which, in turn, improves their response to insulin, reduces liver fat deposition, and corrects their hypotriglyceridaemia. Cultured MEFs derived from Bscl2−/− Mice exhibit a delay in adipogenesis-related genes expression, an augmented basal lipolysis, and an irregular morphology compared to wild type-isolated MEFs. TZD treatment partially rectifies the adipogenic impairment of Bscl2 −/− MEFs but does not affect the aberrant lipolytic rate. The Bscl2 KO murine model serves, therefore, as an interesting experimental framework of defective adipogenesis-related hepatosteatosis. It is also pertinent to note that the beneficial effects of TZD administration on the BSCL phenotype in mice could be extrapolated to clinical settings. Moreover, it would be plausible to surmise, in this context, a putative cross-talk between PPARγ and SEIPIN in the development of mature and functional lipid droplets [85,86]. Chen et al. attributes the failure of Bscl2−/− MEFs to undergo terminal adipocyte differentiation to an unrestrained cAMP/PKA-mediated lipolysis that suppresses adipocyte-specific transcription factor expression. Moreover, UCP1 is upregulated in remaining epididymal WAT (EWAT) of Bscl2−/− mice indicating the acquisition of a ‘brown-like’ phenotype. Contrasting to the findings of Prieur and colleagues, PPARγ agonist treatment fails to alleviate the adipogenic impairment, whereas lipolysis inhibitors can [87]. The obligatory function of BSCL2 in adipocyte differentiation was further accentuated by short hairpin RNA BSCL2 knockout in C3H10T1/2 and 3T3-L1 cells. The silencing of BSCL2 expression in these cell lines undermines adipocyte differentiation through impairment of the adipogenic transcriptional cascade upstream of PPARγ [88,89]. Mice with Bscl2-deficient adipocytes (ASKO) replicate the phenotype of adipose-specific Pparg deletion, manifesting adipose tissue inflammation, progressive WAT and BAT lipoatrophy, insulin resistance, and hepatosteatosis. PPARγ agonist treatment is effective in improving the metabolic symptoms of these mice. Adipose tissue-specific SEIPIN deletion, thus, procures compelling evidence of the intricate regulatory network between SEIPIN and PPARγ signalling [90]. SEIPIN is enriched in ER-mitochondria contact sites where it regulates calcium import into the mitochondria. The depletion of SEIPIN in vitro disrupts mitochondrial calcium influx consistent with the reported signs of mitochondrial injury observed in BSCL patients. Moreover, inducible adipocyte-targeted SEIPIN ablation in mice results in compromised mitochondrial functions preceding severe metabolic manifestations because of impaired ATP production in adipocytes. These findings position BSCL2 as a lipodystrophic syndrome secondary to adipose tissue energetic insufficiency [91]. Interestingly, adipose-specific overexpression of short human SEIPIN isoform in transgenic mice using an aP2 promoter/enhancer induces a mild lipodystrophic phenotype, characterized by a significant decrease in adipose tissue mass and increased hepatic TAG accumulation attributable to the increased expression of lipolytic proteins coupled to an increase in basal and isoprotenerol-stimulated lipolysis. It might seem perplexing that the overexpression of an important locus of adipogenesis in adipose tissue leads to an increase in the lipolytic rate. These findings suggest that SEIPIN functions as a rate-limiting factor of lipogenesis in mature adipocytes [92]. Similarly, deletion of the drosophila SEIPIN gene (dSEIPIN) induces a reduction in orthotopic lipogenesis and a build-up of ectopic LD in the salivary glands. This phenotype is suppressed by forced expression of dSEIPIN in the salivary glands, alluding to potential tissue-autonomous SEIPIN functions [93]. SEIPIN-deficient cells have increased activity of GPAT, suggesting that SEIPIN regulates the function of GPATs [94]. Increased GPAT activity leads to phosphatidic acid (PA) accumulation blocking PPARγ activity and diminishing adipogenesis. Further investigating the relationship between GPAT3 and BSCL2, Gao et al. generated Gpat3/Bscl2 knockout mice. They reported that Bscl2-/-/Gpat3-/- double KO mice exhibit a significant improvement in insulin sensitivity and hepatosteatosis compared to Bscl2-/- KO mice with functional Gpat3. Additionally, Bscl2-/-/Gpat3-/- mice present a significant amelioration in WAT and the complete restoration of BAT mass compared to SEIPIN-deficient mice. GPAT inhibitors might serve as a promising therapeutic approach to manage BSCL patients’ lipogenic and metabolic derangements [95].

In conclusion, SEIPIN occupies a primordial role in adipose tissue development and LD biogenesis in the ER which entails its broad implication in metabolic regulation and energy homoeostasis. Its functional significance is most prominently underscored in lipodystrophic BSCL2 mutants, presenting profound disruptions in lipid metabolism due to impaired LD integrity and lipogenic processes associated with compromised mitochondrial function. These findings elucidate the pathogenic mechanisms underlying the BSCL phenotype, characterized by structural and morphogenic aberrations in lipid droplets due to SEIPIN deficiency. These abnormalities can be partially rectified through the use of lipolysis and GPAT inhibitors, as well as PPARγ agonists.

1-acylglycerol-3-phosphate O-acyltransferase 2 (AGPAT2)

Mutations in 1-acylglycerol-3-phosphate-O-acyltransferase 2 (AGPAT2) are mainly linked to an aberrant fat distribution profile. This transferase enzyme catalyzes the esterification of fatty acyl-CoA which donates its fatty acid chain to the sn-2 position of lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) to produce phosphatidic acid (PA); a critical step in the pathway for biosynthesis of both triacylglycerols and glycerophospholipids. Agarwal et al. suggest that triglyceride metabolism in adipose tissues may be radically altered by mutations in this gene [96]. According to Subauste et al. [97], muscle-derived multipotent cells (MDMCs) of lipodystrophic patients bearing AGPAT2 mutations have defective adipogenic development, impaired PI3K/AKT signalling, and high levels of PPARγ inhibitor cyclic phosphatidic acid (CPA). The impairment in adipogenesis is partially improved upon treatment with pioglitazone, a PPARγ agonist, and fully rectified upon administration of a retrovirus expressing AGPAT2. These findings demonstrate that AGPAT2 modulates adipogenesis through regulation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt and PPARγ pathways. Marta et al. [98] observed lower lipid accumulation and aberrant adipocyte marker expression induced by AGPAT2 deficiency, indicating that AGPAT2 is necessary for mouse preadipocytes to develop into mature adipocytes. Agpat2-/- knockout mice that replicate the features of lipodystrophy in humans, develop severe insulin resistance. Sankella and colleagues [99] report that despite maintaining constant Akt levels; Akt is nonetheless considerably dephosphorylated at Thr-308 in the liver of Agpat2-/- mice, indicating that PDK1 is not activated by PIP3, and thus contributing to severe insulin resistance in these mice. Moreover, Agpat2−/− mice also developdiabetes, and fatty liver due to impaired insulin signalling in addition to a reduction in the levels of the adipokine leptin. Leptin administration to mice with lipodystrophy, lacking white and brown adipose tissue, improves the symptoms by decreasing insulin and glucose levels which were initially elevated due to the underlying insulin resistance. Leptin also increases insulin receptor levels, restoring insulin sensitivity [100]. AGPAT2 homozygous and heterozygous mutations have been linked to global lipodystrophy and thus insulin resistance [96]. Leptin-targeted therapies constitute a promising approach to alleviate congenital generalized lipodystrophy disease symptoms [100].

Impaired lipid droplet hydrolysis and fat-store mobilization

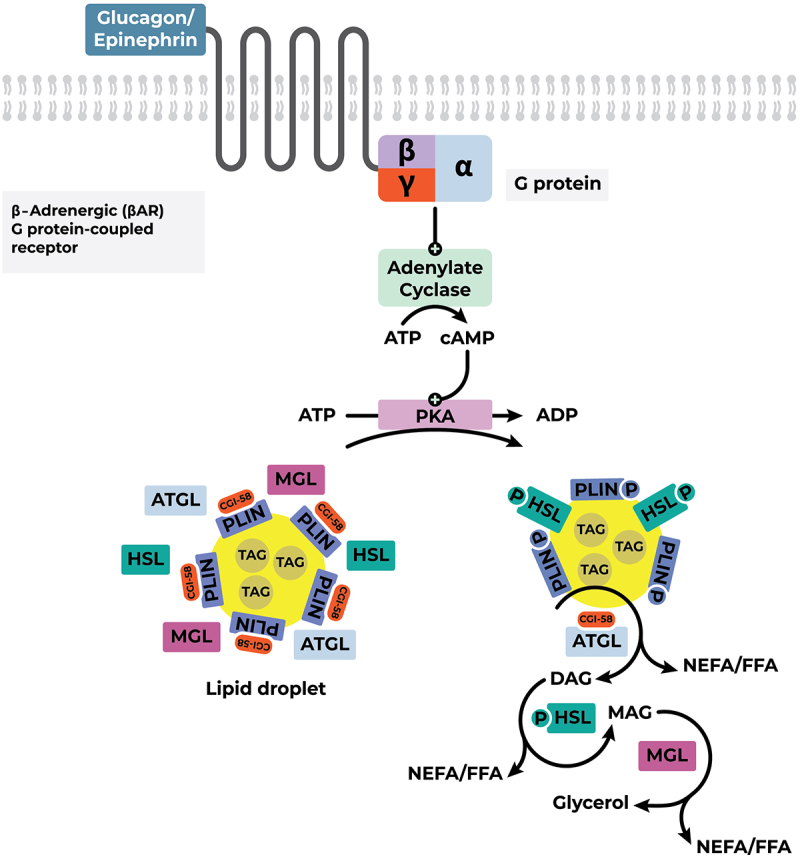

In the context of negative energy balance, the body mobilizes its fat stores in the form of Triacylglycerol (TAG) within lipid droplets of white adipose tissue to sustain physiological processes. The GPCR-mediated activation of adenylate cyclase catalyzes the formation of cyclic AMP (cAMP), which in turn activates protein kinase A (PKA). PKA phosphorylates Perilipin 1 (PLIN1) on the surface of white adipocytes. The phosphorylation of PLIN1 prompts the dissociation of ABHD5 (α/β hydrolase domain-containing protein 5), also known as CGI-58 (Comparative Gene Identification-58), from its surface. This lipase activator subsequently binds onto the Adipose Triglyceride Lipase (ATGL), thereby activating it. ATGL, specific for triglycerides, initiates the breakdown of TAG into diacylglycerol. The hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL), encoded by the LIPE gene and directly activated through PKA-mediated phosphorylation, then preferentially hydrolyzes diacylglycerol into monoacylglycerol, which is ultimately degraded into glycerol and free fatty acids by the monoacylglycerol lipase (MGL). Free fatty acids (non-esterified fatty acids, NEFA) are the major products generated from the breakdown of lipid droplet TAG content [9,101] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Mobilization of TAGs in lipid droplets of white adipose tissue. Abbreviations: ADP, Adenosine diphosphate; ATGL, adipose triglyceride lipase; ATP, Adenosine triphosphate; cAMP, cyclic Adenosine monophosphate; CGI-58, comparative gene identification-58 (co-activator of ATGL); DAG, Diacylglycerol; FFA, free fatty Acids; HSL, hormone sensitive lipase; MAG, Monoacylglycerol; MGL, monoglyceride lipase; NEFA, non-esterified fatty acids; PKA, protein kinase A; PLIN, perilipin-1; TAG, Triacylglycerol.

Perilipin 1 (PLIN1)

The Perilipin protein family (PLIN) has been found to be closely associated with lipid storage droplet proteins. In fact, PLIN proteins are predominantly localized to the surface of LDs in adipocytes. Thus, they can be collectively designated as LD-binding intracellular proteins. The PLIN-protein family comprises five members numbered 1–5 accordingly, with PLIN1 being the major variant with four distinct protein isoforms designated a-d that are distinguished by their different carboxyl ends. The primary site of expression of the most exhaustively investigated perilipin, PLIN1, is adipocytes and steroidogenic cells [101–104].

Research has ascertained the regulatory role of PLIN1 in lipid metabolism and more specifically in lipolysis. Precisely, PLIN1 shields LDs from the catabolic activity of hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL), thus occupying a barrier (sequestering) function. As such, the regulation of lipolysis in adipocytes is tightly governed by distinct downstream signalling pathways that are ultimately conducive to the differential phosphorylation of PLIN1. In fact, PLIN1 is the major substrate of cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA). Consequently, the regulation of lipolysis is contingent upon PLIN1’s phosphorylation state. PLIN1 dephosphorylation inhibits the entry of HSL to LDs and, as such, inhibits lipolysis. However, PLIN1 phosphorylation mediates the hydrolysis of TAG-containing LDs via recruitment of HSL which, in turn, initiates lipolysis. Accordingly, the PLIN-phosphorylation-dependent entry and activation of HSL is obligatory for the mobilization and hydrolysis of TAGs in LDs of adipose tissue. Conversely, PLIN1 dephosphorylation allows for the sustained storage of lipids shielding them from the hydrolytic activity of HSL [103,105]. Considering the aforementioned, the involvement of PLIN1 proteins in affording TAGs a protective coat from HSL activity becomes evident. Consistently, it has been corroborated that the absence of signalling or defects downstream of LD-sequestering proteins, namely PLIN1, is associated with the hyperactivity of lipases as the LDs are found uncovered of their regulatory shield. Consequently, increased hydrolysis of TAG-containing LDs leads to the excessive discharge of FFAs into the bloodstream in the form of NEFAs which in turn disrupts insulin signalling and ultimately results in insulin resistance [7,105–107].

An accruing body of evidence in the literature suggests that PLIN1 plays a modulatory role in the lipolytic rate of LD, and the consequent increase in circulating NEFAs, which extends its involvement in the development of insulin resistance. Tansey et al. demonstrated that Plin1 knockout mice (Plin1−/−) have lower lean body mass compared to wild type controls despite equal feed consumption. Moreover, isolated Plin1−/− mice adipocytes exhibit increased basal lipolytic rate and significantly diminished stimulated lipolysis, underscoring both the regulatory function of perilipin in shielding lipid droplets from lipases and its necessary function in catecholamine-induced lipolysis. Although Plin1−/− mice are leaner, however, these mice possess a greater propensity for peripheral insulin resistance and glucose intolerance. High-fat diet administration to these mice does not promote obesity development, yet they are still prone to glucose intolerance [108]. These findings are corroborated by Martinez-Botas et al. who reported that Plin1−/− mice possess constitutively activated adipocyte HSL which explains their heightened basal lipolysis. However, their work fails to note the occurrence of high plasma glucose and insulin levels in Plin1−/−mice observed in the aforementioned study. This is likely attributed to minute but critical differences in the experimental design of both studies, notably the genetic background and body weight of mice utilized to generate Plin1 knockouts. Interestingly, Leprdb/db mice lacking Plin1 exhibit an augmented metabolic rate and are protected from obesity [109]. In an attempt to understand the metabolic adaptations incurred by Plin1−/− mice due to their unrestrained lipolysis which results in a dramatic reduction of white adipose tissue mass, Saha et al. closely investigated glucose metabolism and fatty acid oxidation in these mice. Their findings suggest that Plin1−/− mice are able to preserve a normal glucose tolerance curve, despite developing progressive peripheral insulin resistance with age, because of a compensatory increase in β-oxidation paired with a reduction in hepatic glucose production [110]. It is nonetheless perplexing that the lean phenotype of Plin1−/− mice is concomitant with peripheral insulin resistance. Sohn et al. were able to answer this query in elucidating the mechanistic triggers of peripheral insulin resistance resulting from Plin1 deficiency. Their data demonstrate that lipid dysregulation in Plin1−/− mice stimulates the recruitment of CD11c+ M1-type adipose tissue macrophages (ATMs). The involvement of this population of pro-inflammatory adipose tissue-infiltrating macrophages in insulin resistance was verified upon macrophage depletion with chlorodronate which ameliorated adipose tissue inflammation and restored insulin sensitivity in these mice [111]. The lean, insulin resistant, and dyslipidemic Plin1−/− mice phenotype is also described by Gandotra et al. who reported similar symptoms in lipodystrophic patients with two distinct heterozygous frameshift mutations in PLIN1. PLIN1 deficiency in humans has been thus identified as a cause of autosomal dominant partial lipodystrophy characterized by significant lipoatrophy and intra-adipose macrophage infiltration along with severe metabolic disturbances, namely diabetes, insulin resistance, hypertriglyceridaemia, hypertension, and hepatosteatosis. This report provides strong evidence that primary disturbances in fat metabolism result in diminished insulin sensitivity and impaired glucose metabolism [112]. It would be plausible to hypothesize that adipose tissue overexpression of PLIN1 would promote obesity considering its pro-adipogenic functions. Interestingly, transgenic mice with adipocyte-specific overexpression of human PLIN1 are protected from diet-induced obesity and exhibit reduced adiposity [113]. Moreover, PLIN1 overexpression in transgenic mice promotes the browning of WAT marked by the upregulation of β-oxidation and thermogenesis-related genes, most notably UCP1 (a BAT-specific protein) through downregulation of Cidec [114]. Interestingly, it seems that knockout and overexpression models of PLIN1 both confer protection against the development of obesity; however, adipose overexpression of PLIN1 ameliorates the metabolic phenotype of transgenic mice, leading to improved glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity, compared to wild-type counterparts administered a HFD [113].

Taken altogether, these studies demonstrate the regulatory role of PLIN1 in energy balance, lipolysis, and overall adipose tissue lipid droplet homoeostasis, thereby modulating insulin sensitivity. It seems therefore pertinent to target PLIN1 as a potential treatment for obesity and defects in lipid metabolism.

Lipase E, hormone sensitive type (LIPE or HSL)

The LIPE gene encodes the hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) that mediates the catalytic breakdown of a wide range of fatty acid esters. The HSL protein has two isoforms, a short and long form, that are expressed in adipocytes and steroidogenic tissues, respectively. Whilst the long form is involved in the production of steroid hormones, the short form hydrolyzes TAGs stored in LDs into circulating NEFAs. The lipolytic activity of HSL is initiated via a catecholamine/hormone-dependent cAMP-mediated activation of PKA which ultimately phosphorylates HSL stimulating its function. The enzymatic activity of HSL assumes broad substrate specificity whereby it hydrolyzes diacylglycerols (DAGs) with greater propensity but is also suitable to catabolize TAGs, monoacylglycerols (MAGs), cholesteryl and retinyl esters [115–118].

Remarkably, mutations at the LIPE locus have been associated with a dysfunctional lipid metabolism i.e. lipodystrophy. In fact, Zolotov et al. provides evidence for the abnormal phenotypic manifestations associated with a novel homozygous mutation at the LIPE locus leading to an atypical presentation of familial partial lipodystrophy. The type of lipodystrophy documented therein is distinguished by partial aberrant subcutaneous fat deposition and multiple symmetric lipomatosis with excessive fat accumulation in the face, neck, shoulders, axillae, back, abdomen, and hypogastrium and reduced subcutaneous fat in lower extremities. Accordingly, the phenotype associated with this mutation has been designated as familial partial lipodystrophy type 6 (FPLD6). In some instances, a progressive myopathy with late onset is described. The aforementioned mutation and its ensuing rare lipodystrophic manifestations have been associated with varying complications relating to insulin resistance, such as diabetes, hypertriglyceridaemia, low levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, and hepatic steatosis [119,120].

The findings of Sollier et al. concur with the earlier observations wherein they identified a novel LIPE null variant in three human subjects that shared a quasi-identical phenotype described prior by Zolotov et al. (i.e. adult-onset hallmarks, lower-extremity lipoatrophy, facial and nuchal lipomatous accumulation, insulin resistance, diabetes, hypertriglyceridaemia, hepatic steatosis, hypertension, and myopathies). The biological sequelae of the LIPE null variant were assayed on adipose stem cells (ASCs). As foreseen, LIPE null ASCs exhibited absence of HSL. Remarkably, the mutated ACSs were characterized by reduced adipogenic differentiation and maturation markers, but also, decreased insulin sensitivity, impaired lipolysis, and a dysfunctional mitochondrial metabolism [121]. Noteworthy are the preliminary works of Farhan et al., Carboni et al., and Albert et al. in identification of several types of mutations at the LIPE locus that have paved the way to establish and ascertain the pathological features which are found to be consistent with the latter works [122–124]. A study conducted on bioengineered HSL-deficient mice (HSL−/−) propounds the involvement of HSL in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. In fact, HSL−/− mice exhibited glucose-intolerance i.e. hyperglycaemia and an absence of plasma insulin secretion in response to a high-glucose dosage (20 mmol/L). Moreover, the findings suggest that HSL−/− mice are insulin-resistant as plasma glucose levels were almost unchanged upon administration of insulin. In comparison to heterozygous (HSL+/-) or wild type (HSL+/+) mice, HSL−/− mice displayed a nearly 2.5-fold higher LD-TAG content than their designated counterparts. Furthermore, under basal conditions, HSL−/− mice presented around 30% less plasma-circulating NEFAs than their defined counterparts. All these observations demonstrate the pivotal role of circulating NEFAs, in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Accordingly, HSL mediates the implication of NEFAs in β-cell glucose signalling and insulin secretion [125].

Interestingly, a long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) sequence, LIPE-AS1, spanning genes CEACAM1 to LIPE, has been shown to be conserved between humans and mice with respect to tissue expression and genomic organization. lncRNA LIPE-AS1, overlapping the LIPE locus, is purported to play a significant role in adipogenesis through its splice variant mLas-V3. It has been demonstrated that mLas-V3 knockdown in OP9 pre-adipocyte cells impairs differentiation as evidenced by the downregulation of adipogenic transcription factors Pparg and Cebpa, and induces apoptotic cell death marked by caspase-3 activation [126]. This compilation attests to the importance of LIPE and/or HSL protein in lipolysis, adipogenesis and adipogenic differentiation, in healthy LD formation and overall lipid metabolism. Its role extends to β-cell glucose signalling and insulin secretion. The cases documented herewith have clearly described the aberrations and phenotypic/metabolic anomalies associated with numerous classes of HSL mutations and/or deficiencies. The ensuing metabolic complications are marked by the onset of a multisystemic disease whose hallmarks are insulin resistance and glucose intolerance.

Impaired nuclear protein function i.e. laminopathic lipodystrophies

Lamin A/C (LMNA)

The LMNA gene encodes the A-type Lamin family of proteins (i.e., Lamin A and C) which are structural proteins that line the interior of the nuclear membrane where they polymerize into a complex fibrous network constituting the nuclear lamina. In addition, Lamin proteins are constituents of the intermediate filament (IF) family of proteins which are major cytoskeletal components. Besides, Lamins are the sole nuclear IF proteins and the main structural component of the nucleus in animal cells. The literature has established the involvement of Lamin proteins in various cellular, and more notably nuclear, processes, such as nuclear integrity, chromatin structure and organization, gene expression, transcriptional regulation, and DNA repair [127,128].

To truly appreciate the versatile roles of Lamin proteins and their functional significance, mutations at the LMNA locus have been associated with numerous human diseases and disorders designated collectively as laminopathies. Laminopathies are associated with striated muscle, adipose tissue, and peripheral nerve. As such, they comprise a wide scope of characterizable clinical manifestations that include: Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome and Werner’s syndrome (premature ageing syndrome), Charcot-Marie-Tooth (neuropathy) disease, Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy, limb girdle muscular dystrophy, dilated cardiomyopathy, restrictive dermopathy, and familial partial lipodystrophy [129–131].

In the enquiry hereafter we shall be concerned with the LMNA mutations that are relevant to lipodystrophic phenotypes. The underlying mechanism by which such a clinical manifestation arises awaits further elucidation. However, the considered conjectures suggest impaired gene transcription resulting from altered binding of the nuclear lamina to chromatin, impaired binding of the nuclear lamina to transcription factors, and a defective nuclear envelope structure. It is worthy to note that lipodystrophy-associated LMNA mutations are predominantly localized in the carboxy terminus of the encoded protein, and as such, they do not alter the three-dimensional structure of the protein, but rather affect protein–protein interactions [131].

The clinical manifestations that are discernible in FPLD-associated (Familial partial lipodystrophy) LMNA mutations are collectively designated as FPLD type 2 (or Dunnigan syndrome). It is an autosomal dominant disease which arises from different heterozygous missense mutations that localize around exon 8, mainly at codon 482, of the LMNA gene [131,132]. In 1974, Dunnigan et al. to whom the disease is eponymous were the first to characterize the ensemble of the clinical hallmarks of FPLD2 [133]. In fact, Dunnigan-type lipodystrophy is discernible by its face-sparing attribute. It is also marked by the loss of subcutaneous fat i.e. lipoatrophy of the limbs and the trunk, hypertrophy of the labia majora, acanthosis nigricans, hirsutism, all of which generally occur upon pubescence. Additionally, FPLD2 is accompanied with several metabolic complications such as dyslipidemia, impaired glucose tolerance, mild to severe insulin resistance, T2DM, hypertriglyceridaemia, eruptive xanthomatosis and pancreatitis, and hepatic steatosis [131,134–136].

Interestingly, Boschmann et al. suggest that the occurrence of insulin resistance in LMNA-associated FPLD is not tied to dysfunctional insulin-mediated glucose uptake, but it is rather due to impaired insulin-mediated glucose oxidation. However, the pathophysiological mechanism whereby LMNA mutations induce FPLD-linked metabolic complications remains lacking. Nonetheless, preliminary findings suggest that LMNA-induced FLPD phenotype targets genes involved in the processes of nuclear transport, thereby, affecting transcription of genes implicated in metabolism [137]. It is postulated that the resulting metabolic disturbances could be attributed to either abnormal prelamin A farnesylation and accumulation or to defective signalling downstream of sterolregulatoryelement-binding protein 1 (SREBP1) and MAPK pathways which result in the inability of adipocytes to adequately store TAGs in LDs [138].

The efforts are concentrated on unravelling the pathophysiological mechanism through which such a diverse array of LMNA mutations is associated with different disorders of varied manifestations and symptoms.

Impaired insulin clearance and defective INSR downstream signalling

Caveolin 1 (CAV1)

Caveolin 1 is a vital component of the plasma membrane that interacts with a variety of signalling systems and is crucially involved in both lipid processing and metabolism. Insulin resistance and an increase in atherogenic plasma lipids and cholesterol are induced by the global deletion of Cav1 in mice [139]. In humans, the homozygous mutation of CAV1 gene is the main cause of congenital generalized lipodystrophy (CGL; also known as Berardinelli-Seip syndrome), diabetes and nearly absent subcutaneous adipose tissue at birth.

The insulin receptor in adipocytes is directly regulated by CAV1 as it modulates insulin signalling and insulin receptor stability [140]. According to Cohen et al. [141], Cav1 deficient mice exhibit insulin-resistance. Another investigation reported a decrease in insulin signalling, as well as substantially lower INSR mRNA levels in the intestines of Cav1IEC-KO mice as compared to controls. CAV1, in addition to its critical function in glucose/lipid homoeostasis, may also modulate mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) signalling. Hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia are linked to overactivation of the aldosterone and MR pathway. Reduced expression of CAV1 may enhance the influence of aldosterone/mineralocorticoid receptor signalling on various pathways, primarily the glycaemic and dyslipidemic pathways. Thus, insulin resistance and impaired glucose metabolism have been attributed to irregular aldosterone signalling resulting from the downregulation of CAV1 expression [142]. On a high fat diet, Cav1 null mice exhibit insulin insensitivity and hyperinsulinemia resulting from a primary defect at the INSR in adipocytes. That is, a reduced level of phosphorylated INSR, in addition to a dramatic downregulation of INSR β-subunit, account for the defective insulin receptor signalling observed in these mice. This is further demonstrated by a response failure of PKB/Akt and GSK-3 after administration of insulin [141]. The effects of hypoxia, a consequence of adipocyte hypertrophy and hyperplasia in obese individuals, on insulin signalling and sensitivity have been investigated in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. 3T3-L1 cells cultured in hypoxic conditions display a drastic reduction in expression of adipocyte differentiation and insulin sensitivity genes, decreased TAG accumulation, and a diminished capacity to uptake glucose in response to insulin via impaired GLUT4 translocation. These findings are associated with the downregulation of Cav1 protein expression and the abrogation of insulin-induced Cav1 phosphorylation through an HIF-1-dependent mechanism. It is therefore inferred that hypoxia-mediated downregulation of CAV1 contributes to the development of insulin resistance [143]. Moreover, CAV1 maintains the stability of the INSR and is a positive activator of insulin signalling [140]. Overall, these findings indicate that during insulin resistance, the separation of IR from CAV1 causes defective insulin signalling and therefore reduced GLUT4 translocation to the membrane, which decreases glucose cellular uptake.

Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 (CEACAM1)

The expression of the Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 (CEACAM1) occurs early in embryonic development. CEACAM1 was initially discovered in the bile and therefore it is also designated as biliary glycoprotein (BGP) [144]. CEACAM1 is also known as CD66a which belongs to the immunoglobin (Ig) superfamily [145,146].

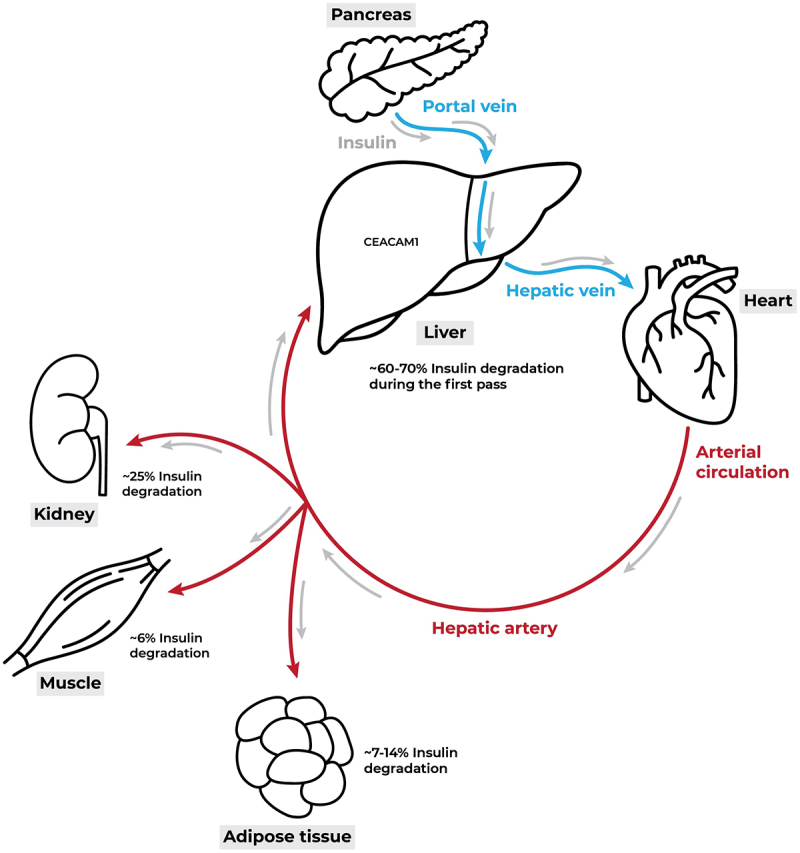

CEACAM1 regulates insulin sensitivity via its facilitation of insulin clearance and through its inhibition of fatty acid synthase (FASN) activity. The insulin receptor tyrosine kinase is activated by phosphorylation following an acute rise of insulin, which in turn leads to CEACAM1 phosphorylation and activation [147,148]. This phosphorylation cascade will direct the clearance of up to 80% of secreted insulin through hepatic CEACAM1-mediated insulin receptor internalization [149–151] (Figure 4). FASN is the key enzyme in de novo lipogenesis whereby it catalyzes the synthesis of palmitate from malonyl-CoA. Phosphorylation of CEACAM1 mediates a suppressive effect on liver lipogenesis by down regulating FASN activity [152]. Mice with null mutation of Ceacam1 (Cc1-/-) exhibit systemic insulin resistance due to impaired insulin clearance [153,154]. In addition, these mice have an increased triglyceride output and redistribution to white adipose tissue, as reflected by elevated visceral obesity [155]. In fact, wild-type (WT) mice subjected to a high-fat (HF) diet exhibit >60% reduction in CEACAM1 levels after 3 weeks of feeding, resulting in impaired insulin clearance and the consequent development of insulin resistance. The onset of diet-induced insulin resistance associated with the reduction in insulin clearance due to the deleterious effects of FFA on insulin metabolism are tethered to a PPARα-dependent mechanism. Notably, adenoviral-mediated CEACAM1 redelivery countered the adverse metabolic effect of the HF diet on insulin resistance, hepatic steatosis and visceral obesity [156]. Similarly, liver-based rescuing of CEACAM1 resulted as well in full normalization of the metabolic phenotype [157]. Moreover, HF diet fed mice teated with nicotinic acid, a potent inhibitor of lipolysis, preserve their insulin sensitivity and hepatic CEACAM1 expression, despite altered insulin signalling in WAT. Thus, highlighting the role of lipolysis-derived NEFAs in downregulating hepatic CEACAM1 expression [156]. These findings strongly propound the therapeutic potential of CEACAM1 in alleviating diet-induced metabolic dysfunction in extra-adipose tissues.

Figure 4.

The journey of insulin. Insulin is discharged from the pancreas into the portal vein in a pulsatile manner, and it is primarily supplied to hepatocytes. The liver is the first organ to receive insulin, and it clears most of the insulin during the first passage, which accounts for around 60–70% of the insulin. The lingering insulin enters the systemic circulation, where peripheral tissues such as muscles, adipose tissue, and kidneys utilize it moderately, and then the liver degrades it again during the second passage through the hepatic artery. Modified from [149].

Insulin receptor (INSR)

The INSR encodes the membrane-bound heterodimeric α and β protein chains comprising the insulin receptor. The α subunit constitutes the soluble ectodomain and the β subunit serves as the membrane anchor. These two subunits are linked by a disulphide bridge, forming the α-β complex, which dimerizes to create the active receptor. The INSR belongs to a group of transmembrane signalling proteins known as ligand-activated receptors and tyrosine kinases [158].

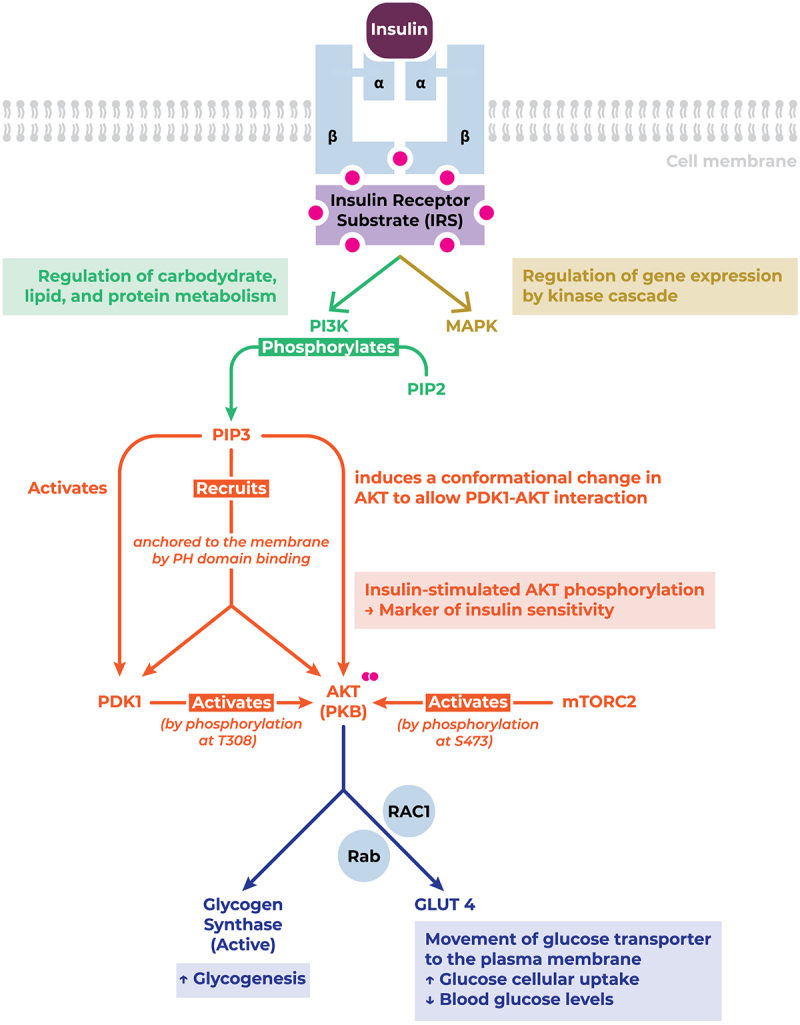

Insulin, produced by the pancreatic islets of Langerhans’ β-cells, is the master regulator of a myriad of metabolic processes of which glucose homoeostasis is the most prominent [159]. Upon binding its cognate receptor, insulin differentially governs glucose homoeostasis via the PI3K/AKT pathway and cell growth and differentiation via the MAPK pathway [160–162]. Furthermore, insulin mediates predominantly anabolic processes in skeletal muscles, liver, adipocytes and other tissues via its complex tyrosine kinase signal transduction pathway [159,163,164] (Figure 5). Insulin induces glycogenesis, adipogenesis, and protein synthesis pathways, whilst inhibiting their catabolic counterparts, such as glycogenolysis and lipolysis. Moreover, insulin suppresses gluconeogenesis and facilitates cellular glucose uptake via inducing glucose transporter 4 (GLUT 4) translocation from its intracellular compartment to the plasma membrane [159].

Figure 5.

INSR structure, downstream signalling pathway, and function. Upon Upon binding to its cognate receptor, insulin triggers the phosphorylation and recruitment of key signalling mediators conducive to their activation, thereby enhancing cellular glucose uptake, and promoting glycogenesis. Abbreviations: AKT/PKB, protein kinase B (serine/threonine-specific protein kinase); GLUT, glucose transporter; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; mTORC2, mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2; PDK1, pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1; PH, pleckstrin homology; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; PIP2, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate; PIP3, phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate; Rab, GTPase; RAC1, GTPase; S473, serine 473 residue; T308, threonine 308 residue.

Thus far, we investigated the aberrations in adipocyte physiology conducing to dysfunctional glucose metabolism and impaired insulin sensitivity. We demonstrated throughout this review that abnormalities in insulin signalling can be in fact attributed to pathological mechanisms extrinsic to the insulin signalling pathway that are rather the result of impaired LD-protein function that affect adipocytes amongst other collateral physiological targets. Insulin resistance is oftentimes associated with, or even brought about by, an aberrant lipid distribution profile (i.e. a lipodystrophic phenotype), underscoring the cross-talk between insulin signalling and adipose tissue physiology [19,159,165]. In this section, however, we focus on the reciprocal effect of INSR signalling on adipocyte phenotype, function, and development and its vital role in adipocyte physiology and metabolic homoeostasis.

Insulin signalling orchestrates the development and maturation of adipose tissue [166]. Specifically, the INSR is crucial for stem cell commitment to adipogenesis during early embryonic stages. Mouse induced pluripotent stem cells (miPSCs) derived from embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) of Insr knockout (IRKO) mice subsequently differentiated to adipocytes exhibit poor adipocytic differentiation markers compared to their control counterparts. In fact, the IRKO miPSC-derived adipocytes fail to develop into mature adipocytes marked by downregulation of key proteins instrumental to the adipose lineage, particularly lipogenic enzymes (Fas and Acc), lipid transporters (Fabp4), and proteins involved in adipocyte and unilocular lipid droplet formation (Cebp, Pparγ, and Fsp27) [167]. These findings underscore the significance of INSR signalling in adipocyte physiology. Specifically, insulin is not an obligatory component of early adipogenesis stages; however, it is essential in terminal adipocyte differentiation and ensuing physiological function [168–170]. Thus, impairment or ablation of INSR signalling is detrimental to adipocyte development and overall phenotype.

In obesity, insulin stimulates adipocyte expansion to store excess energy intake under the form of TAGs in LD. However, chronic exposure to positive energy balance reduces adipocyte response to insulin stimulation which in turn compromises adipose tissue physiology. The failure of adipocytes to respond to insulin stimulation renders them incompetent to store TAGs efficiently, thereby conducing to increased lipolysis and ectopic fat accumulation. Therefore, INSR signalling allows for the sustenance of a healthy lipid droplet phenotype with ‘fat buffering’ capacities to preserve insulin sensitivity and consequently insulin-dependent metabolic processes [171].

The selective abrogation of INSR signalling in different tissues induces disparate metabolic phenotypes. For instance, fat-specific disruption of the insulin receptor gene (FIRKO) in mice, achieved through an adipose-restricted aP2 promoter-driven Cre recombinase, reduces adiposity and ameliorates longevity, all while maintaining normal insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance [172,173]. Pursuant to the aforementioned, Boucher et al. reported significant deterioration in adipose tissue development and deficient thermogenesis of Insr and Igf1r double-knockout mice using the aP2-Cre recombinase system [174]. However, ablation of INSR in adiponectin-expressing cells engenders severe pathological manifestations coupled with aberrant lipid metabolism and impaired glucose homoeostasis, including insulin resistance, lipodystrophy, dyslipediamia, ectopic fat accumulation in the liver (hepatosteatosis), muscles, and islets [175,176]. Moreover, targeted INSR disruption in GLUT4-expressing tissues of transgenic mice results in altered adipose tissue morphology, insulin-resistant adipocytes, and diabetes [177]. This suggests that the suppression of insulin-stimulated glucose cellular uptake arising from defunct INSR affects insulin sensitivity among insulin-responsive tissues differentially. Interestingly, transgenic mice with homozygous peripheral INSR disruption (PerIRKO−/−) via tamoxifen-inducible Cre recombinase system present with a diabetic phenotype characterized by heightened blood glucose and circulating insulin levels, coupled with an an abbreviated lifespan, whereas their hemizygous (PerIRKO±) counterparts exhibit reduced adiposity and mildly enhanced hepatic insulin response, despite no impact on lifespan [178].

In conclusion, INSR signalling, in adipocytes particularly, is indispensable for the maintenance of glucose homoeostasis and insulin sensitivity, thus preserving adipose tissue physiological function, wherein impairments would prompt metabolic disturbances associated with abnormal lipid storage profiles.

Conclusion

The phenotypic manifestations associated with disturbances in adipose tissue metabolism can be attributed to a disparate gamut of mutations and defects that culminate in functional aberrations in adipogenesis and LD-TAG sorting and mobilization, coupled with altered glucose homoeostasis and insulin sensitivity. We have inventoried in the text, and tabulated hereunder (Table 1), the physiological function and the pathophysiological mechanisms resulting from mutations and defects in CIDEC, PPARG, BSCL2, AGPAT2, PLIN1, LIPE, LMNA, CAV1, CEACAM1, and INSR that underlie lipid droplet pathologies which are oftentimes accompanied with more complex metabolic disorders and syndromes that permeate multiple organ systems.

Table 1.

Panel of investigated genes and their associated metabolic pathophysiologies.

| Alias | Name | Protein product | Localization/Nature/Class | Function | Associated pathophysiological impairment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impaired lipid droplet formation and fat storage in adipocytes | |||||

| CIDEC | Cell Death Inducing DNA fragmentation factor α-like Effector C | CIDEC | LD-protein |

|

↓ CIDEC expression/mutation in humans → ↓ LD biogenesis & fatty acid partitioning, Multiloculated LDs, increased mitochondria, small LD size → Partial lipodystrophy, Ectopic fat deposition, insulin-resistant diabetes. ↓ Tissue-specific CIDEC expression in mice (adipose-specific ablation) → ↑ Lipolytic rate & impaired LD storage → Ectopic fat deposition in liver → Hepatosteatosis, elevated serum TAGs & NEFAs → Systemic insulin resistance. Constitutive CIDEC ablation in mice → Leaner phenotype, protected from diet-induced obesity → ↑ Energy expenditure & mitochondrial biogenesis in WAT → WAT acquires BAT-like properties (↑ Mitochondrial size/function, ↑ BAT-specific proteins & transcriptional regulators) → ↓ Obesity risk Human CIDEC transgenic mice → Protection against diet-induced insulin resistance → ↓ Circulating NEFAs |

| PPARG | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma | PPARγ | Nuclear receptor |

|

Genetic mutations in PPARG in humans:

|

| BSCL2 | BSCL2 lipid droplet biogenesis associated, seipin | SEIPIN | Endoplasmic reticulum |

|

BSCL2 mutations in humans: Cause Berardinelli-Seip Congenital Lipodystrophy (BSCL), characterized by severe lipodystrophy, insulin resistance, hepatic steatosis, and hypertriglyceridemia. Bscl2−/− mice: Almost complete absence of adipose tissue, insulin resistance, hepatosteatosis, but hypotriglyceridemic (unlike humans). Bscl2−/− MEFs: Delayed adipogenesis-related gene expression, increased basal lipolysis, irregular morphology. GPAT3/BSCL2 double KO mice: Improved insulin sensitivity and hepatosteatosis, with restoration of WAT and BAT mass compared to SEIPIN-deficient mice. ER-mitochondria contact sites: SEIPIN depletion disrupts mitochondrial calcium influx, leading to mitochondrial injury and impaired ATP production in adipocytes. Adipose-specific overexpression of SEIPIN in transgenic mice: Induces a mild lipodystrophic phenotype with decreased adipose tissue mass and increased hepatic TAG accumulation. Inducible adipocyte-targeted SEIPIN ablation: Results in mitochondrial dysfunction preceding severe metabolic manifestations, emphasizing SEIPIN’s role in energy homoeostasis in adipocytes. |

| AGPAT2 (BSCL1) | 1-acylglycerol-3-phosphate O-acyltransferase 2 | AGPAT2 | Endoplasmic reticulum |

|

AGPAT2 mutations in humans:

|

| Impaired lipid droplet hydrolysis and fat-store mobilization | |||||

| PLIN1 | Perilipin 1 | PLIN1 | LD-protein |

|

Human PLIN1 mutations: Cause partial lipodystrophy → Lipoatrophy, macrophage infiltration, severe metabolic disturbances (diabetes, insulin resistance, hypertriglyceridemia, hypertension, hepatosteatosis). Plin1−/− mice: ↓ Lean body mass, ↑ Basal lipolysis, ↓ Stimulated lipolysis, ↑ Insulin resistance/glucose intolerance via M1-type ATM recruitment. PLIN1 overexpression in mice: Protects against diet-induced obesity, ↑ WAT browning (↑ UCP1), improves glucose tolerance/insulin sensitivity. |

| LIPE | Lipase E, Hormone Sensitive | Hormone Sensitive Lipase (HSL) | LD-protein |

|

Genetic mutations in LIPE in humans:

HSL−/− mice: ↑ LD-TAG content (~2.5-fold higher), ↓ Plasma-circulating NEFAs (~30% less) → Glucose intolerance (hyperglycemia), no plasma insulin secretion with high glucose → Insulin resistance (plasma glucose levels unchanged with insulin). |

| Impaired nuclear protein function (i.e. laminopathic lipodystrophies) | |||||

| LMNA | Lamin A/C | LAMIN A LAMIN C |

Nuclear protein |

|