ABSTRACT

Background: Research shows that adult refugees’ well-being and future in the reception country heavily depend on successfully learning the host language. However, we know little about how adult learners from refugee backgrounds experience the impact of trauma and adversity on their learning.

Objective: The current study aims to investigate the perspectives of adult refugee learners on whether and how trauma and other adversity affect their learning.

Methods: We conducted in-depth interviews with 22 adult refugees (10 women) attending the Norwegian Introduction Programme (NIP). The participants came from six Middle Eastern, Central Asian, and African countries. Two questionnaires were included, one about past stressful life events (SLESQ-Revised), and one about mental health symptoms and current psychological distress following potentially traumatic experiences (PCL-5).

Results: Participants held varying beliefs about trauma’s impact on learning: that it had a constant impact, that it was situational, or that it had no impact. Other aspects they brought up as having an essential effect on learning and school attendance include psychological burdens from past and present school experiences, and post-migration hardships such as loneliness, depression, ongoing violence, and negative social control. Post-migration trauma and hardships exacerbated the burden of previous trauma and were frequently associated with a greater negative influence on learning.

Conclusion: This study adds new insights from adult refugee learners themselves into how post-migration hardships as well as trauma can impact their learning, and the importance of recognising their struggles. A safe space is required for refugees to open up about their difficulties in life and with learning. This knowledge can be used to enhance teaching practices, foster better teacher-student relationships, and inform policy-making decisions, ultimately benefiting both individuals and society.

KEYWORDS: Adult learners from refugee backgrounds, learning, school attendance, traumatic experiences, gender-based violence, forced family separation, post-migration hardships, negative social control, SLESQ, PCL-5

HIGHLIGHTS

Adult refugee learners’ own perspectives on the impact of trauma on learning varied from constant to situational to no impact at all.

Other factors identified as impacting learning and school attendance included, amongst others, psychological burdens from past and present school experiences, ongoing violence, forced family separation, and negative social control.

Post-migration trauma and hardships were frequently associated with a greater negative influence on learning than the burden of previous trauma.

Abstract

Antecedentes: Investigaciones demuestran que el bienestar y el futuro de los refugiados adultos en el país de asilo, dependen de manera importante del éxito en el aprendizaje del idioma del país de acogida. Sin embargo, sabemos poco de cómo quienes aprenden siendo adultos y tienen el antecedente de ser refugiados, experimentan el impacto del trauma y la adversidad en su aprendizaje.

Objetivo: El presente estudio busca investigar la perspectiva de los estudiantes adultos refugiados en cómo, y si es que, el trauma y otras adversidades afectan su aprendizaje.

Métodos: Realizamos entrevistas en profundidad a 22 adultos refugiados (10 mujeres) que asisten al Programa de Introducción Noruego (NIP por sus siglas en ingles). Los participantes provenían de seis países del Medio Oriente, Asia Central y África. Se incluyeron dos cuestionarios: uno acerca de eventos vitales estresantes pasados (SLESQ-Revised), y otro sobre síntomas de salud mental y malestar psicológico actual luego de experiencias potencialmente traumáticas.

Resultados: Los participantes tenían distintas creencias acerca del impacto del trauma en el aprendizaje: que tenía un impacto constante, que era situacional, o que no tenía impacto. Otros aspectos que mencionaron que tenían un efecto esencial en el aprendizaje y la asistencia escolar, incluyen la carga psicológica por experiencias escolares presentes y pasadas, y dificultades postmigración como la soledad, la depresión, la violencia constante, y el control social negativo. El trauma y las dificultades postmigración exacerbaron la carga de traumas previos, y con frecuencia se asociaron con una mayor influencia negativa en el aprendizaje.

Conclusión: Este estudio aporta nuevas perspectivas de los propios estudiantes adultos refugiados, sobre cómo las dificultades postmigración y el trauma pueden impactar en su aprendizaje, y la importancia de reconocer sus dificultades. Se necesita un espacio seguro para que los refugiados hablen abiertamente acerca de sus dificultades en la vida y en el aprendizaje. Este conocimiento puede ser utilizado para mejorar las prácticas docentes, alentar mejores relaciones profesor-estudiante, e informar las decisiones de formulación de políticas, lo que en última instancia beneficia tanto a los individuos como a la sociedad.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Estudiantes adultos procedentes de entornos de refugiados, aprendizaje, asistencia escolar, experiencias traumáticas, violencia basada en género, separación familiar forzada, dificultades postmigración, control social negativo, SLESQ, PCL-5

1. Introduction

An increasing number of newly arrived refugees attend language courses and other educational settings in resettlement countries around the world, including the Scandinavian countries (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2024, p. 6). Many refugees have experienced severe trauma and encounter extensive postmigration difficulties (Li et al., 2016). Many also struggle to learn the new language and other subjects that are important to get a good start in the new country (e.g. Söndergaard & Theorell, 2004). Therefore, an urgent quest for knowledge about the impact of trauma on learning has been raised. Such knowledge is vital as a first step towards knowing how adult education can meet the needs of adult refugee learners who have experienced trauma and are currently facing post-traumatic hardships. In this study, we address this highly relevant topic, focusing on whether and how adult refugee learners themselves experience the impact of trauma and post-migration hardships on learning.

A small number of empirical articles have, as a main focus, addressed this question (e.g. Beiser & Hou, 2001; Gordon, 2011; Ilyas, 2019; Mojab & McDonald, 2008; Santoro, 1997), while others only briefly mention this (e.g. Ćatibušić et al., 2021). The empirical studies vary regarding the number of participants, from three (e.g. Gordon, 2011; Santoro, 1997) to 86 (Söndergaard & Theorell, 2004). Several studies investigate teachers’ perceptions of how mental health issues like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) affect adult learning (e.g. Holmkvist et al., 2018; Stone, 1995; Wilbur, 2017), and some sources also address additional barriers to learning (e.g. Salvo & de C Williams, 2017), or trauma as one of several obstacles to learning (e.g. Kamisli, 2022). Other relevant peer-reviewed sources addressing the potential impact of trauma on adults’ learning, such as theoretical articles, syntheses of existing knowledge and digests (e.g. Adkins et al., 1999; Finn, 2010; Kerka, 2002; McDonald, 2000; Perry, 2006; Wilson, 2017), and grey literature like conference proceedings, reports and political documents (e.g. Ilyas, 2019; Palanac et al., 2023; UKOM - The Norwegian Healthcare Investigation Board, 2021), demonstrate, moreover, that the experiences and voices of adult learners are limited. The sources referred to in this paper are, whenever possible, limited to those focusing on adult refugees and/or migrants.

In this article, the term refugee refers to individuals who have fled their countries due to war and human rights violations (United Nations General Assembly, 1951). We define (potentially) traumatic events or experiences as scary, dangerous, or hurtful events or experiences that may lead to traumatisation. This is in line with van der Kolk’s (2014, p. 82) broad definition of trauma. According to van der Kolk (2014, e.g. p. 111), traumatic events such as emotional neglect, domestic abuse, rape, accidents, and war are overwhelming experiences that go beyond an individual’s coping capacity. These experiences impact ‘(…) the entire human organism – body, mind, and brain’, as well as their relationships, but they do not necessarily lead to traumatisation (van der Kolk, 2014, p. 152). Once, adverse life experiences and trauma were believed to be rare (Herman, 2015, p. 33). Today, traumatic experiences are regarded as common (Kessler et al., 2017; Weathers & Keane, 2007), yet extraordinary, as they overwhelm the ordinary coping capacity of the individual (e.g. Herman, 2015, p. 33). A person’s subjective experience determines whether an event is traumatic (Emdad & Söndergaard, 2005; Weathers & Keane, 2007).

Multiple studies demonstrate that trauma exposure leads to a heavy burden on individuals, families, and societies (e.g. Beiser & Hou, 2001; Johansen & Varvin, 2019). Mental health problems (anxiety, depression, and PTSD) and chronic pain adversely affect many refugees’ everyday functioning (Nissen et al., 2022). Despite previous findings that refugees’ mental health symptoms improve with time (e.g. Porter & Haslam, 2005), both previous (Fazel et al., 2005) and current international studies (Aysazci-Cakar et al., 2022; Blackmore et al., 2020; Henkelmann et al., 2020) show an increased risk of developing mental illness after resettlement. Psychological distress and recurring symptoms can persist for years or even decades after traumatic experiences (e.g. Blackmore et al., 2020; Opaas & Varvin, 2015; Vaage et al., 2010). As in the general population, refugee women report higher levels of psychological distress than men (e.g. Porter & Haslam, 2005; Vallejo-Martin et al., 2021). Severe physical and sexual violence, such as torture and rape, are significantly associated with high levels of post-traumatic physical and psychological distress for both men and women (e.g. Steel et al., 2009). However, sexual violence among refugee boys and men often goes unreported due to social and cultural stigma and taboos. Moreover, men are not typically considered a vulnerable group, which increases the likelihood of their trauma experiences being overlooked or ignored (Chynoweth et al., 2022).

In a literature review on post-migration stressors’ impact on refugees’ mental health, Li et al. (2016) found that post-migration stressors such as financial strain and unstable housing, social isolation, discrimination, ongoing family separation and concern about family abroad, in addition to protracted asylum processes and harsh immigration policies had a greater impact on mental health and well-being than pre-migration trauma. Repeated exposure to stress and trauma, demands from society and feeling a sense of exclusion and isolation may contribute to a higher prevalence of ill-health among migrants and refugees (e.g. Johansen & Varvin, 2020). A Norwegian report indicates that during settlement in Norway, even refugees with good health upon arrival experienced that high demands, expectations, and pressure in everyday life, the Norwegian Introduction Programme (NIP) included, exhausted their coping capacity, and some even developed serious mental health problems (UKOM, 2021). Previous research has also documented the impact of forced family separation on e.g. depression (Liddell et al., 2021). Finally, it is well documented that social isolation, whether deliberate or unwanted, and loneliness are associated with poor mental health and physical health problems (e.g. Liddell et al., 2021; Salway et al., 2020). It is reasonable to assume that these factors can impede adult refugees’ learning and school functioning.

Several other factors, not focused on in this study, can influence individuals’ second language learning. These include culture and background (Hossain, 2024), age, first language characteristics and competence, abilities and learning preferences (Lightbown & Spada, 2021), years of schooling and interrupted schooling (Huang, 2022), and experiences of violence (Horsman, 2000). In addition, technological competencies, bilingual teaching supports, and everyday interactions with members of the reception country can promote learning the host-country language (Ćatibušić et al., 2021).

1.1. Adversity, trauma, and learning

Adverse life experiences and trauma can cause insecurity that impairs people’s capacity, willingness, and courage to explore, discover, and learn (Perry, 2006). For adult refugee learners, previous traumatic experiences can lead to lack of motivation and high levels of anxiety. Especially adult learners with PTSD are academically disadvantaged, as PTSD causes difficulties concerning attention, concentration, and memory, factors that are crucial for learning (Emdad et al., 2005). Adverse life experiences and stress might also impact students’ academic well-being, which is described as students’ academic satisfaction and performance (Shek & Chai, 2020). In the ‘second language classroom,’ such problems represent potential barriers to engaging in verbal interaction (Benseman, 2014; Kerka, 2002), which is a crucial component in successful language acquisition (Lightbown & Spada, 2021). The second language classroom is a term used for the setting where the focus is on teaching and learning a second language (e.g. Lightbown & Spada, 2021).

1.2. A resource and action-oriented approach to learning

Influenced by a sociocultural perspective on learning (e.g. Lightbown & Spada, 2021, pp. 213–216; Vygotsky, 1978), we see adult learners from refugee backgrounds as active, social agents and autonomous co-producers of knowledge, possessing (hidden) resources, willing to take responsibility for both their learning and lives. In this perspective, learning is perceived as integrally tied to and thus situated and mediated within a specific sociocultural context. Consequently, learning experiences are neither socially nor semiotically neutral, rather they represent a specific worldview (de Haan, 2012). We consider social interaction as essential for learning and co-construction of meaning (e.g. Council of Europe, 2020, p. 21) and as an important aspect of recovery after adverse life experiences (Herman, 2015, p. 133).

Searching for adult refugees’ resources and agency does not ignore the severity of their traumatic experiences, post-migration difficulties, and losses, whether it includes relationships and belonging, health, money and property, time, or concentration. Neither does it ignore that many adult refugee learners are not allowed to utilise their resources as they wish or hope for in the new country (Brücker et al., 2023; Ghadi et al., 2019). However, being vulnerable does not exclude strength and being traumatised does not exclude being resourceful.

A resource- and action-oriented view on learning and the learner as an active individual exercising agency is rooted in Norwegian legislation on integration (e.g. Integration Act, 2020, §§1, 15), and international agreements and action plans (UN General Assembly, 2015; United Nations General Assembly, 2018). Moreover, this view is also highlighted in the Curriculum for Norwegian language training for adult immigrants, language levels A1-C1 (Norwegian Directorate for Higher Education and Skills [HK-dir], 2021, p. 3), which is based on the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages’ (the CEFR) proficiency levels and its view on learners as active, social individuals exerting agency (Council of Europe, 2020, pp. 28–30). Facilitating active participant involvement in education and language learning is a prerequisite to comply with these regulations and plans. Learner-centred approaches, where refugee and migrant voices are heard and acted upon, are also highlighted by non-governmental organisations (NGOs) like The European Association for the Education of Adults [EAEA] (2019, p. 4). Listening to participants’ voices in research follows from the view of refugee learners as active co-producers of knowledge.

1.3. The Norwegian Introduction Programme (NIP)

The NIP is a full-time compulsory training programme aiming to equip recently arrived refugees for early integration into the Norwegian society and to become financially independent (Integration Act, 2020, Section 1). Participants in the NIP receive financial support (introduction benefits) from the Norwegian state (§ 19). This mandatory programme can last from a minimum of three months to four years depending on participants’ educational background, age, and the individual’s educational and professional end goal with the programme (Integration Act, § 13). Currently, it includes the following components: Norwegian language training and social studies (course on Norwegian society) and life skills (‘Coping with life in a new country’), parental guidance, and work- and educational elements (Integration Act, § 14).

In Norwegian language training, which is an important part of the NIP, proficiency levels range from illiterate, to A1, A2, B1, B2, and C1. Schools have various options for organising language classes, and refugees and other migrants are often in the same group. Group sizes may range from small to large, with up to 30 participants. The teaching material is a combination of available educational resources and materials created by the teacher. Educators teaching Norwegian are required to have relevant professional and pedagogical competence (Integration Act, § 39).

1.4. Research on adult refugee learning

There is a knowledge gap in academia and a quest for knowledge in the practice field about what impacts adult refugees’ learning and difficulties with learning. Especially, we lack knowledge about learners’ own experiences with trauma and learning. As outlined above, there is not much research to lean on in the search for answers to these questions. Adult learners from refugee backgrounds are of particular interest due to the large number of refugees who have experienced trauma and loss as a result of human rights violations and forced displacement. Moreover, according to international agreements, refugees are entitled to rebuild their lives in the reception country (United Nations General Assembly, 1951), and language learning play a crucial role in this process. There is considerable research on trauma’s impact on refugees’ health (e.g. Handiso et al., 2023). Moreover, studies have demonstrated that health is important to adult refugees’ learning (e.g. Palanac et al., 2023; Steel et al., 2011). Although research shows that trauma affects learning (e.g. Benseman, 2014; Gordon, 2011; Söndergaard & Theorell, 2004), we still know little about how adult refugees themselves experience the impact of trauma and adversity on their learning, and the potential barriers they impose.

1.5. Aims

The purpose of this study is to learn from adult refugees’ own experiences with trauma and adversity, particularly their view of whether and how trauma has impacted their learning and well-being. Their own experiences and views are important to identify approaches that can strengthen teaching and learning. The main research question guiding this study is: How do adult refugee learners experience the impact of trauma and adverse life experiences on learning and well-being?

2. Method

This phenomenological study is based on in-depth interviews with twenty-two adult learners from refugee backgrounds. The study was approved by the Norwegian Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REK, 2018/1186). Participants were recruited by strategic sampling. Inclusion criteria: refugees with a right and obligation to participate in the NIP and who were currently enrolled in or had previously participated in the programme. To ensure the research participation of adult learners who might not otherwise be heard, Norwegian language competence was not required.

2.1. Participants

We e-mailed school leaders at adult education centres throughout Norway, briefly explaining the study and asking them to connect us with teachers who could suggest and contact potential participants. When the respective schools accepted the invitation to participate, we emailed invitation letters and consent forms to the school leaders, who then forwarded them to the contact persons. The contacts explained the purpose of the study to potential participants and distributed written invitations with project details and consent forms. One of the contact persons also gave oral information about the study in the participants’ first languages. Among eligible adult learners who were asked to take part in the study – the number of which we do not know – twenty-two (12 men) consented. In this study, to preserve a sense of individuality and the anonymity of the interviewees, we gave them fictitious names.

2.2. Procedure

The participants were unknown to the interviewer until the scheduled research interviews took place. In order to increase participants’ trust, the contacts introduced the interviewer to the participant and followed them to the room where the research interview took place. All interviews were conducted in a quiet, private room in the respective school. Contacts ensured access to cold drinks. The contact’s presence in the beginning contributed to creating a calm and relaxed atmosphere. However, the contacts were not present during the interview.

If a participant asked for language assistance, or when it was apparent that such assistance was required, a professional telephone interpreter was offered, regardless of the participant’s language proficiency level. With six of the interviewees (four men, two women) we made use of an interpreter. To ensure the best possible interview experience, we used interpreters who had previously interpreted in similar situations and on similar topics.

Before the main interview started, the interviewer repeated the information in the invitation letter (such as the purpose of the study, the participant’s rights, and confidentiality) and she asked if the participant had any questions. All participants provided written informed consent. Also, before the main interview, the participants completed two questionnaires in a language suited to their linguistic background, one regarding past stressful life events (SLESQ-Revised; Goodman et al., 1998), the other on mental health symptoms and current psychological distress (PCL-5; Weathers et al., 2013). The two questionnaires were primarily utilised to identify the participants’ traumatic experiences and the hardships they had endured and to give an impression of their symptom burden. The participants completed the questionnaires alone or, at their request, together with the interviewer. Then the participant and the researcher completed a demographic form together before the qualitative interview started.

To prevent unnecessary psychological distress to the participants during the qualitative interviews, we did not ask further about the traumatic experiences they had reported in the SLESQ-Revised. We also did not encourage them to elaborate on sensitive topics. However, when the participants unsolicited addressed their traumatic and hurtful experiences during the interview, and when appropriate, we asked follow-up questions in a careful and sensitive way. Furthermore, despite the interviewer’s sensitivity to terminology and cultural nuances in languages, occasional ambiguities or misunderstandings occurred. The same applied to the interviews with an interpreter. Occasionally, an interviewee responded to something other than the interviewer’s question. One possible explanation is incorrect translations by the interpreter. For example, when questioned about painful feelings and learning, one interviewee answered that she slept well.

The 22 face-to-face interviews lasted from one to two hours each and were transcribed shortly afterwards. The first author conducted and audio-taped the interviews and took notes during the process. As agreed with the participants, the first author contacted the interviewees two days after the interview to check out how they were doing. She also asked if they wanted to give additional information, if the interview had triggered difficult thoughts and emotions, and if they felt they needed to talk to a professional. A clinical psychologist (the second author) was ready to have a consultation by phone with those who needed it.

In writing up the results, the first author translated quotations from the interviews from Norwegian into English. Names and other identifiable details were changed or removed in order to protect the participants’ anonymity. A related concern was whether providing exact numbers (such as 1f/3 m) could compromise the participants’ anonymity. However, communicating the findings without quantifying might give the impression that, for example, more participants discussed being in combat than the three who did. We have tried to balance the two considerations.

2.3. Questionnaires, demographic form, interview guide, and material aids

Potentially traumatic experiences (PTEs) were recorded by the Stressful Life Events Screening Questionnaire – Revised (SLESQ-; Goodman et al., 1998). Originally, the SLESQ included 13 questions about exposure to stressful life events. The Norwegian version (Thoresen & Øverlien, 2013) is a 15-item measure that assesses lifetime exposure to potentially traumatic experiences. Except for one open-ended question, the participants were asked to indicate whether they had experienced the event (‘yes’ or ‘no’). The participants were asked to indicate with an asterisk (*) the event that impacted them the most at the present time. The SLESQ has good test-retest reliability, and cultural validity is within the recommendation for instruments used in populations other than those for which it was originally developed (Goodman et al., 1998; Green et al., 2006; Raghavan & Sandanapitchai, 2019). However, the SLESQ does not ask about torture, being held captive or a prisoner of war, terrorist attacks or traumatic flight experiences. Nevertheless, the absence of these items may be accounted for by the single open catch-all item, question 13.

Mental health – symptoms of PTSD. Posttraumatic stress reactions were measured using the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5; Weathers et al., 2013), which has 20 items rated on a five-point Likert scale from 0 (Not at all), 1 (A little bit), 2 (Moderately), 3 (Quite a bit), to 4 (Extremely likely). The Norwegian version was performed by Heir (2014). It is divided into four subscales corresponding to the symptom clusters outlined in the DSM-5: B (Intrusion, items 1–5), C (Avoidance, items 6–7), D (Negative Alterations in Cognitions and Mood, items 8–14), and E (Alterations in Arousal and Reactivity, items 15–20). Scores from all 20 items are added, resulting in a sum ranging from 0 to 80. Initial studies suggested a cutoff score of either 31 or 33 as indicative of probable PTSD, depending on the needs of the assessment to be inclusive or stricter (Weathers et al., 2013). Various studies across populations have shown that the PCL-5 is a psychometrically sound measure of PTSD symptoms. However, depending on the population in question, a higher or different cutoff score may be required (e.g. Ashbaugh et al., 2016; Blevins et al., 2015; Boyd et al., 2022). The 22 interviewees rated their level of symptom distress over the previous month. In this study, we employed the guideline’s stricter cutoff score of 33 (Weathers et al., 2013).

After obtaining written permission from the right holders, the two questionnaires were translated from English into Arabic, Tigrinya, and Farsi by a professional translation service in Norway (NORICOM Nord AS, Ålesund).

Sociodemographic characteristics were recorded by a demographic form which included a set of 18 questions (e.g. civil status, social network, housing, education level, employment status and occupation).

The qualitative interview. We constructed a semi-structured interview guide covering questions about their motivation to participate in the study, their perspectives on how trauma affects their learning, the challenges and successes they experienced in managing distressing emotions and thoughts during the school day, and their views on the teachers’ role in assisting them to cope.

Visual aids and concrete materials. Visual aids, in combination with auditory cues, are widely used as supportive learning tools in second language teaching (e.g. Mashhadi & Jamalifar, 2015). As a language teacher, the first author was well familiar with using visual aids to support communication and learning, such as when introducing new words, explaining concepts, or directing the student’s attention to a particular topic. Moreover, discussing abstract concepts such as emotions, health, and learning in a second language are particularly challenging. Therefore, in the research interviews, unless a participant indicated otherwise, we utilised visual aids (photos) and two empty picture frames of different sizes, representing ‘the emotional window of tolerance’ (Siegel, 2012, pp. 281–286), as conversational support. The interviewer (first author) explained to the participants the thoughts behind the window of tolerance in a simple way, such as the idea that when a person operates inside the ‘window’, they can handle emotions and be able to learn. When affects and arousal are too strong, or numbed and frozen, they fall outside the window of tolerance and may not be able to listen, concentrate or learn. The participants responded positively to the use of picture frames, and several actively and on their own initiative used the frames during the interview to describe their internal state in different situations.

2.4. Participants from refugee backgrounds – some considerations

Adult learners from refugee backgrounds are vulnerable due to their multiple hardships, including past and present adverse life experiences and post-migration difficulties. Additional vulnerability factors encompass interviewer-interviewee power asymmetry (Brinkmann & Kvale, 2015, p. 6, 37–38) alongside specific topics that may elicit emotional distress. Moreover, encouraging victims of domestic and other violence to tell about their situation could potentially put them in danger. Hence, the researcher bears a particular responsibility and obligation to attend to the interviewees’ well-being and security. The interviewer, who has extensive experience working and discussing sensitive issues with refugees, attended closely to these concerns during the interviews and after, by making the follow-up phone call, as described.

2.5. Researcher reflexivity

Researchers are both influenced by and influence the research process, and their preconceptions shape how they perceive and assess the research interviews (Brinkmann & Kvale, 2015). The impact of emotions in research and the intimate nature of the interview relationship, as highlighted by Warren (2001)’s reflections on her emotional responses upon recognising herself in the participants’ narratives, requires finding a balance between proximity and distance (e.g. Garrels et al., 2022).

The first author is a language teacher for adult learners from refugee and migrant backgrounds and has many years of experience with individual and group conversations (such as ‘life skills’ groups) with refugee and migrant learners who have experienced traumatic events. The second author is a researcher and clinical psychologist with extensive experience in research and therapy with traumatised refugees. She was available for follow-up by phone if any participant would have wanted or needed it. The researchers are both white, middle-aged, middle-class women, who have taken a professional and personal interest in refugee’s health, learning and wellbeing in this country. Our engagement and empathy towards adult learners from refugee backgrounds, as well as our pre-understandings shaped by factors such as upbringing, educational background and work experience, influence the content of the study, and how findings are interpreted and presented. As a result, certain parts of the data may become unintentionally overlooked or emphasised.

2.6. The analytical process

We conducted thematic analysis of the interviews. An open and exploratory analytical approach is necessary to get insight into the perspectives of the participants (e.g. Flick, 2023, pp. 7–8). The initial analysis of the interviews included repeated reading of the 22 transcriptions and listening to the tape recordings while taking notes of any initial reflections, thoughts, and ideas. This phase of getting familiar with the interview data was also crucial for developing relevant analytical questions. F4analyse software (bit.ly/49EQCtb) was used to structure the material. Throughout the research process, we created memos, analytical notes and summaries, all of which were gathered and stored in the F4analyse. We began the analysis by exploring the participants’ views of whether and how adverse life experiences influenced their learning. Based on the interviewees’ responses on these questions, we returned to the data and asked: What do they, individually and as a group, consider most important? Again, their answers prompted us to revisit the data and look closer into which traumatic events the participants had encountered and what significance they attributed to these experiences in terms of their learning and learning progression.

With each analytical question in mind, each transcript was analysed ‘vertically,’ focusing on one interview at a time. Then, they were analysed ‘horizontally’ across the interviews. The analysis involved a combination of manual approaches and digital tools, allowing for creativity and organisation of a rich material. We organised the identified excerpts from the analytical questions into initial topics, each labelled with a descriptive heading (Magnusson & Marecek, 2015, pp. 93–95). The topics were then sorted and grouped into potential themes, all named with a descriptive title reflecting their content. The themes were sorted, revised and refined in several rounds. Throughout the analytical phases, we used colour coding to identify recurring patterns, variations, and topics that belonged together.

Thematic maps drawn by hand have been invaluable tools. However, we also utilised data visualisation (e.g. Flick, 2023, p. 475) to depict themes and sub-themes developed in the (mainly) manual approach. At this stage of the analysis, we created figures in Smart Art (Microsoft Word), which we printed in A3 format. The figures provided us with an overview of the identified themes and how they were related. Both manual and digital figures aided us in editing and refining themes, sorting and grouping similar themes, identifying overlap, (re-) organising themes into hierarchies, and understanding how they related (or not) to each other, the analytical questions and the overall research question. The process involved a back-and-forth between manual and digital analytical work. We developed two overarching, interrelated themes: Negotiating learning after trauma and The individuals behind the desks, each with their own sub-themes.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

The participants, twelve men and ten women, aged 19–57, came from six different Middle Eastern, Central Asian, and African countries (Table 1). Education levels ranged from no schooling to six years of university. Some had their education interrupted due to conflicts and war. The participants came to Norway between 2011 and 2017 and had been in Norway for two to eight years at the time of the interview. The participants were then enrolled in language training and/or in primary education for adults. The Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration (NAV) provided financial assistance to four out of the five participants who had completed the NIP but needed additional qualifications, such as language training or primary school for adults. Three of the participants who had little or no schooling from their country of origin (0–6 years) had received three years of language training. Because of health issues, they were about to apply for a fourth year, either to continue language training or enter primary education for adults. However, some well-educated participants also applied for an additional year primarily due to factors like health and age.

Table 1.

Demographics of the Participants.

| Females (N=10) n/M (SD) |

Males (N=12) n/M (SD) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Introduction Programme at the time of interview | ||

| Attending Introduction Programme | 7 | 10 |

| Completed Introduction Programme | 3 | 2 |

| Attended Primary School for Adults | 6 | 7 |

| Time of stay in Norway | ||

| 5–8 years | 2 | 1 |

| 4 years | 5 | 5 |

| 3 years | 1 | 1 |

| 1–2 years | 2 | 5 |

| Age | ||

| Average age in years | 34.8 (SD=8.4) | 33.5 (SD=9.4) |

| Variation in age | 23–48 | 19–57 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 5 | 8 |

| Divorced | 3 | 0 |

| Widow(er) | 1 | 0 |

| Single | 1 | 4 |

| Children (average) | ||

| Children | 8/10 | 6/12 |

| Children outside Norway | 2/10 | 2/12 |

| Children, average | 2.5 | 1.4 |

| Family/relatives in Norway | ||

| More than 5 | 5 | 3 |

| Less than 5 | 5 | 6 |

| No family/relatives | 0 | 3 |

| Norwegian friends/acquaintance | ||

| More than 10 | 0 | 3 |

| 6–10 | 0 | 2 |

| 5 or fewer | 6 | 3 |

| No Norwegian friends | 4 | 4 |

| Religious Affiliation | ||

| Muslim | 8 | 9 |

| Christian | 2 | 3 |

| Education, outside Norway | ||

| 0 years | 1 | 2 |

| 1–4 years | 1 | 2 |

| 5–10 years | 4 | 5 |

| 11–13 years | 2 | 1 |

| More than 13 years | 2 | 2 |

| Housing type (rental) | ||

| Apartment | 5 | 7 |

| Single family house, semi-detached | 3 | 2 |

| Row house | 2 | 0 |

| Bedsit | 0 | 3 |

| Work before Norway | ||

| Full time, outside home | 2 | 11 |

| Part time | 2 | 1 |

| Full time, houseparent | 3 | 0 |

| No work | 3 | 0 |

| Work in Norway | ||

| Full time | 0 | 1 |

| Part time | 1 | 2 |

Note. Introduction Programme = a training programme intended to prepare adult refugees for work or education in Norway. For example, the programme may include language training or adult primary school. Housing type (rental): All participants rented housing.

Before they arrived in Norway, two of the ten women and eleven of the twelve men had been working full-time. Four participants combined full-time studies with part-time or full-time work. Regarding social network, the women had fewer Norwegian friends or acquaintances than the men. Equally many women and men reported having no Norwegian friends or acquaintances.

3.2. Wordless, yet not speechless

Many interviewees expressed similar experiences to Mina’s (age 33) description of her trauma experiences: ‘I believe that what I’ve experienced is more than people can think. Or imagine.’ Some stated they had no words to describe their experiences, whether in Norwegian or their native language. The traumatic experiences caused them to feel disconnected from themselves and their loved ones. Several stated that they needed to talk about their difficult life experiences, despite the discomfort. In our experience from the interviews, the participants needed to address these experiences before discussing their possible impact on learning. By thoroughly examining questionnaire responses and interview statements, we acquired valuable insights into the profound impact of traumatic experiences on their lives and learning.

3.3. Adverse life experiences

Although the sample is non-clinical, the results from the SLESQ-Revised (Table 2) show that the men had experienced on average 6.5 and the women 5.8 different kinds of traumatic events. The men’s most frequently reported traumatic experiences were life-threatening accidents, mainly related to their escape, and witnessing violent death due to the war. Among women, the most frequently reported experiences were being subjected to childhood physical abuse and being repeatedly harassed or verbally abused by family members or other close relations. During the interviews it became evident that the participants’ trauma experiences extended far beyond the questions in this questionnaire.

Table 2.

Potentially Traumatic Events Experienced by Gender (SLESQ-Revised).

| Event | Females (N=10) (n) | Males (N=12) (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Life-threatening illness | 0 | 3 |

| Life-threatening accident | 4 | 10 |

| Robbery/mugging | 1 | 7 |

| Loss of loved ones | 4 | 10 |

| Sexual assault, rape | 4 | 1 |

| Attempted sexual assault | 4 | 1 |

| Childhood physical abuse | 6 | 1 |

| Adulthood physical abuse | 4 | 5 |

| Repeatedly ridiculed (in close relations) | 6 | 1 |

| Threatened with weapons | 3 | 8 |

| Witnessed death or assault | 4 | 8 |

| Other injury or life threat | 5 | 7 |

| Other extremely frightening or horrifying event | 8 | 9 |

| Directly impacted by natural disaster | 2 | 4 |

| Repeatedly ridiculed (outside family) | 3 | 3 |

| Total, traumatic experiences | 58 | 78 |

Half of the men identified experiences related to war or escape, noted in the open item, as what impacted them the most at the time of the interview. About one third of the women identified experiences related to war or domestic violence, noted in the open item, as the most painful at the present time. Sami commented: ‘It is difficult to say what bothers me the most since everything is equally painful.’ Several participants recounted their life-threatening boat journeys to freedom. A woman remarked, repeatedly tapping the top of her pen: ‘The first boat capsized, and I saw people swimming, and there were many children, many children, and they died. I saw many children die. It is difficult. I still think about it many days.’

Other experiences perceived as traumatic by the interviewees, elaborated in the open item of the SLESQ and/or in the interviews, included miscarriage (as a result of domestic violence), being sexually exploited (as a result of Internet contact), emotional abuse and hurtful relationships, divorce (alone as a woman – driven to prostitution), food insecurity and hunger, extreme poverty (forced the interviewee into prostitution as a child), being poisoned, being held captive, sexually abused by same-gender adults during fleeing, and severe caregiver mental illness. Four of the men had witnessed or undergone torture while being imprisoned. One woman had been beaten and verbally abused several times when in jail, experiences which were extremely frightening: ‘They beat me and such, and I was very scared.’ These horrifying experiences and subsequent fear prompted all to flee their country.

During the interviews, women addressed a greater number of traumatic experiences before and after migration than men did. As shown in Table 2, women’s traumatic experiences were mainly related to intimate relationships. Unsolicited, three of the five women who reported domestic violence in the SLESQ described experiencing severe physical and psychological violence, as well as financial violence, after arriving in Norway. Ongoing domestic violence negatively affected the women’s school attendance and concentration. Alviva (age 27), who had suffered severe violence, said: ‘Once, my entire body turned black.’ She added (tearful voice): ‘When I was in class, my body was present. But my head was not in that class.’

The men’s adverse life experiences mentioned in the interviews were mainly war-related, for example, being in the military, in combat, or tortured. For many of the men, forced family separation caused great psychological distress and difficulties with concentration and learning. Sometimes, the participants referred to disappointing and discomforting events as ‘traumatic’, which is a common use of the term in everyday speech. For example, one student described her inability to attend school as traumatic, while men characterised as traumatic the waiting for a response from UDI, unpaid debt, or lack of a driver’s license.

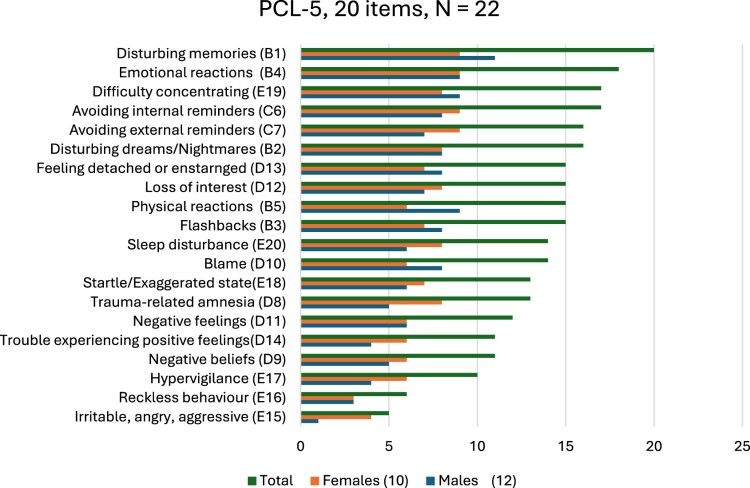

3.4. Posttraumatic reactions

According to the participants’ results on the PCL-5, half of the women and somewhat below half of the men met the criteria for a provisional PTSD diagnosis. Their symptoms had persisted for over a month. However, our interview findings showed that for some, the symptoms had lasted for years. Moreover, the analysis of the interviews suggested that some adult learners who met the provisional PTSD diagnostic criteria had also been depressed or were currently dealing with depression. The adult learners’ PCL-5 responses provided important insight into the duration, severity, and burden of their trauma reactions. See Figure 1. In the interviews, the participants frequently told about trauma reminders, flashbacks, sleeping difficulties, and painful feelings and thoughts as sources of distress. Several participants also addressed physical health issues such as severe headaches, stomach aches, and pain in the back, shoulders and neck. For instance, Noor (age 48) said: ‘In the first days of language training, I went to the toilet crying. I had constant headaches from thinking about that [severe physical violence], and the loud voices from fellow students.’ Another student, Sami (age 19), said: ‘Every part of my body aches.’

Figure 1.

Overview of the 22 participants' PCL-5 results.

Note. PCL-5 = PTSD Checklist for the DSM 5. The capital letters in brackets represent one of four PCL-5 subscales/clusters: B (Intrusion, items 1-5), C (Avoidance, items 6-7), D (Negative Alterations in Cognitions and Mood, items 8-14), and E (Alterations in Arousal and Reactivity, items 15-20). The number following the letter refers to a specific item (1 to 20). For example, Disturbing memories (B1) refers to cluster B (Intrusion), item 1 (of 20), and shows that 20 out of 22 participants (in varying degrees) experienced disturbing memories of the traumatic experience(s).

3.5. Main themes in the interviews

The adult learners’ experiences with the impact of trauma and post-migration hardships on learning addressed in the interviews revolved around two overarching, interrelated themes: Negotiating learning after trauma, with the sub-themes (Not only) past trauma and Learning grief, exploring the variability in their beliefs and a particular consequence of loss, and The individuals behind the desks, with three sub-themes, all representing barriers to learning: The continuing silence, Loneliness and depression, and Gossip – an invisible force. Both overarching themes and their sub-themes explore factors that may not be readily apparent or transparent to the teachers but can be vital to adults’ learning progression after traumatic experiences.

3.6. Negotiating learning after trauma

(Not only) past trauma. This subtheme includes participants’ beliefs regarding the impact of traumatic experiences on learning. The main tendency in the material is that the participants believed that trauma impacted their learning. However, several participants felt that their traumatic experiences only affected their learning in specific situations, such as when other students started to talk about the war. Amal (age 23) shook her head and covered her ears with her hands saying: ‘I will hear nothing about it!’ She explained that on such days she could not concentrate and learn. Sami (age 19), who had experienced extreme traumas, took a deep breath as he reflected on his learning: ‘I know that I have some problems with my language learning. For example, sometimes I use the wrong word or verb tense.’ When the interviewer asked him if he thought about previous traumatic experiences when in class, Sami tapped his forefinger on the table, pointing to each of the 15 items in the SLESQ, and said:

Do you see that I answered yes-yes-yes to everything? How do you think I can get away from that experience, or that? And what should I do with that one? (…) I shouldn’t think about that one either, but it keeps coming!

Before arriving in Norway, 23-year-old August had a life-threatening accident and also tragically lost a loved one to homicide. Throughout the interview, he repeatedly expressed concern about a depressed and isolated sibling and an upcoming language exam (level A1-A2). Sleepless nights, increasing intrusive thoughts and restlessness, led him to wander the neighbourhood at night. Like many interviewees, he equated obtaining citizenship with safety, and failing to meet the citizenship language requirements terrified him. Daily, the teachers trained students for the language exam. However, August’s fear of poor test performance interrupted his concentration. Despite having permanent residency in Norway, he firmly believed that if he failed, he would have to return to his home country, which for him meant death. Consequently, he had to obtain level A2 proficiency. He concluded: ‘There’s a problem with my brain because I think so much about my sibling and how I can achieve [language] level A2.’ At the time of the interview, August had heard rumours about tightening citizenship language requirements (from oral A2 to oral B1), which further exacerbated his concentration difficulties. He believed he would never meet language level B1 requirements for Norwegian citizenship. Some participants expressed feelings of fear and uncertainty in response to media coverage of refugee policy or reference to refugees in general. Despite being granted residency, a young woman chuckled when she remarked: ‘Some news about refugees is not good. I’m sitting like this (staring blankly into the air), not reading. I asked my husband, ‘Why, why study?’ I don’t want to spend years studying only to be sent back.’

Two of the 22 interviewees stated that their traumatic experiences (imprisonment and torture) had strengthened them. One concluded:

In a way, it influences me negatively. However, I believe these experiences have strengthened me. I think I’m stronger than before (…) I’m more patient now. So, when I hear bad news, I don’t react like a few years ago (…) I’m more solid.

Both had higher education from countries outside Norway and were about to complete a two-year introduction programme at the time of the interview. According to the information provided in their demographic forms, their oral levels were A1+ and B1, respectively. However, the level B1 participant said he was unsure whether his learning was negatively affected by the experiences, but his mental health was. The second one, one of the eldest participants, believed his learning problems were age-related. Although the torture he had endured had a devastating impact on his physical health, he underlined that this had little effect on his mental health:

So, I was tortured. They broke my teeth, my scull (…) Of course, it has impacted my health. When I came out of prison, I was half my original weight and my hair had turned grey. I had to get treatment in hospital, but it didn’t affect my psychological health. Today, I’m stronger psychologically.

However, not everyone believed that previous traumatic experiences impacted their learning or life in general. Some participants provided different explanations on what negatively affected their learning. One interviewee who, after two years of Norwegian language training, had reached language level A1+, said:

Traumatic experiences don’t affect my learning at all. The fact that I’ve been separated from my family for years is the only thing influencing my learning outcomes. The family reunification process is in progress, but it’s taking a very long time. That’s why my thoughts are divided: because a father isn’t with his family.

Interestingly, he did not, like some of the others, seem to consider being separated from his family as a traumatic experience. Nevertheless, the forced separation had a devastating impact on his concentration and learning progression.

Learning grief. We propose the term learning grief to capture an aspect of grief that appeared in some of the interviews. First and foremost, learning grief refers to a profound sense of loss regarding one’s own learning capacity. One interviewee stated that life came to a halt after a traumatic event, causing an interruption in learning that persisted for years: ‘I feel like my life has stopped. Oh, how I stopped! I stopped learning. And I can’t remember many things.’ Like several others, because struggling to learn new things and recall new information, he mourned the loss of his former learning capacity. John (age 38) lowered his voice while contrasting his current and past learning abilities: ‘I was an example for others. But not anymore! (…) Maybe I have only 30 per cent of my capacity left.’ Another aspect of learning grief was related to the participants’ educational backgrounds, such as never having had an opportunity to attend school. A young participant’s childhood dream was to become a lawyer. His voice trembled with emotion as he recalled his anguish when realising he could not attend school: ‘I thought: What kind of future do I have if I can’t go to school? I wondered if I should send everything to hell. Maybe die. I have nothing.’ Years later, he still mourned his missed learning opportunities. Despite being offered education in Norway, he struggled to attend, which added to his grief, like it did for several of the other participants. Regardless of educational level, their health problems (e.g. depression), relationship issues, and severe domestic violence prevented some participants from attending language learning. A woman who lost the first year of language instruction due to severe violence and threats from her ex-husband, wept while describing extreme isolation and the grief of having missed a year of learning opportunities: ‘For a year, I didn’t dare to go outside my house. I couldn’t go to school.’ Finally, another element of Learning grief involved experiencing feelings of shame regarding their perceived lack of progress in their learning and, like John, being unable to meet their own expectations as successful learners.

3.7. The individuals behind the desks

During the interviews, some participants shared their concerns about how their teachers perceived their concentration issues and slow learning progression. John (age 38) concluded: ‘When I think about the fact that I’m speaking Norwegian like this, even after two years of language training, I feel really bad.’ Few had experienced their teacher addressing trauma exposure as a potential cause of slow learning progress. One participant who had been incarcerated by ISIS twice and endured what he described as ‘severe beatings’ said: ‘There are no teachers who know why I’m depressed, there is no one who has asked, so they can’t know. It’s very difficult to keep up with school because my head is busy with other things.’ He added: ‘I have huge concentration problems, and I’m not able to remember things.’

The continuing silence. Like many interviewees, Alviva (age 27) had been frequently beaten by her teachers in her home country. She recounted times when teachers beat her in the face or hands with a wooden stick with tiny needles, causing her to bleed. Children being beaten learn nothing, she emphasised. Alviva explained that the worst part was the teachers’ ignorance when she came to school after being beaten by her father, which caused difficulties walking and controlling her bladder. Tearful, she stated: ‘No one! (tearful voice) No one asked us.’ Unfortunately, the silence around refugees’ traumatic experiences often continues in Norway. John (age 38)’s following statement summarised several participants’ experiences during the NIP: ‘It’s ok if the teacher is interested. If he asks, I’ll answer. (…) We talked about my background, if I attended school, and all that. But we’ve never mentioned or talked about my migration journey.’ The participants did not want in-depth discussions about their experiences; instead, they wanted teachers to have the necessary information to understand, appreciate and evaluate their students’ efforts and progress. Some participants mentioned that teachers could better understand slow learning progression, concentration problems, and absence by having some information about their students’ traumatic experiences. The adult learners’ willingness to share such information depended on their sense of safety. One interviewee shook his head and said he refused to respond when, at a school parent meeting, parents from refugee backgrounds were asked to share their traumatic experiences. He quietly concluded: ‘Because I didn’t want to remember the pain.’ Participants generally avoided discussing adverse life experiences in class, such as war or migration journeys, as it caused stress, affecting their concentration and well-being. Amal (23) summarised: ‘If you talk about war, you’ll get stressed, and then you don’t remember well.’

Another aspect of The continuing silence was the lack of interpreter use in teacher-student conversations. Our findings indicate that adult learners faced obstacles in sharing important information about their health and learning situation with their teachers due to lack of access to an interpreter. This contributed to maintaining the silence surrounding their traumatic experiences and their consequences. In these instances, adult learners wanted to communicate openly with their teachers but were unable to do so because an interpreter was not offered. One of these learners was Hana (age 47), who said: ‘I wished I could have spoken with my teacher more.’ Participants with limited literacy skills were particularly at a disadvantage as they had less access to digital resources like Google Translate. Hana concluded: ‘If I had an interpreter, I would have talked much more! I had no one here to talk about my horror, fear, and depression.’

Finally, The continuing silence involved how refugees themselves perpetuated in maintaining the silence surrounding their experiences. Its core is depicted in Mina’s reflections on expectations and norms within her ethnic and cultural group. During the interview, she told she had broken cultural norms by addressing traumatic experiences and gender-based violence, leading to exclusion and silencing by others from her ethnic group. She raised her voice while saying: ‘You shall keep everything inside; don’t talk with others. Keep your emotions to yourself! – To maintain the family, they must follow their childhood rules. They should never break their parents’ rules, even if they live in Europe!’

Loneliness and depression. Ten of the adult learners addressed depression, and some had suffered for years. The men attributed their depression to loneliness and forced family separation. A man who had been imprisoned and tortured stated: ‘Talking about trauma isn’t taboo in my culture, but people dislike hearing about it; they don’t like it. They just enjoy hearing about good things.’ The loneliness had become an enormous burden, and he had been seeing a psychologist for the depression and anxiety that developed after arrival: ‘These experiences [the torture and imprisonment] are just one part. Another part is the feeling of loneliness here in Norway.’ He learned that, although friendly, Norwegians surrounded themselves with an invisible barrier impossible to cross, which intensified his loneliness. He stated: ‘Norwegians are – I always say that – Norwegians are the nicest people in the world. I, I believe so. But at the same time, there is an invisible road you can’t cross – yes, that wall.’ He concluded: ‘I felt completely down because I’d never been alone in my life (…) It was difficult to learn, difficult to concentrate, and difficult to sit in class.’

Unsolicited, five participants addressed experiencing suicidal thoughts after migration. One had attempted suicide several times, and two others had considered suicide, one because of a lengthy asylum process. Living in a remote area with limited public transportation and social interactions increased his anxiety and depression, sleeping difficulties, and loneliness. Two women experienced suicidal thoughts while depressed. Nakia (age 41), who had been sexually exploited both outside and inside Norway, blamed herself and was too ashamed to turn to anyone for support and comfort, including her sibling. Overwhelmed by shame, she could not bear her own reflection: ‘After what I did, I didn’t want to look in the mirror. I don’t want to look at myself in the mirror because these eyes are watching me. I tell myself: You’re not a good person.’ Depressed, she was unable to attend language learning for a year. When she finally attended school, she could not explain to her strict teacher why she frequently missed class, let alone reveal what was wrong. One day, the teacher scolded her for once again failing to do her homework: ‘Why haven’t you done your homework!?’ and for behaving in a way that reflected poorly back on the teacher, who had dual responsibility: ‘I have a responsibility for you, and I also have to answer to my superiors!’ Implicitly, the participant should pull herself together and do what was expected. Nakia said:

I was depressed, and I felt I had no one to confide in. I had a lot of pain in my body, many thoughts in different directions; I wasn’t present, I didn’t comprehend what happened. It was difficult to learn back then. It really affected my learning.

Nevertheless, the reprimands turned out to be a blessing in disguise, as she decided to seek psychological help after having been scolded.

Hana (age 47) appeared open, goal-oriented, and passionate about learning during the interview. She courageously addressed the consequences of a brutal and life-altering traumatic experience on her learning and well-being: ‘In the beginning, I was very, very happy. I was very excited to learn the language. However, my depression kept me from learning much’, Hana explained. Neither did she attempt to hide that her children also suffered because of her depression: ‘When they, for example, said something, I quickly became angry and irritated. And I was sensitive to sounds.’ Nevertheless, unlike several other participants, Hana sought physiological and psychological treatment, which became a significant turning point in her life as she began to recover. Hana’s utterance about her depression captured the experiences of multiple participants and highlighted the profound impact of depression on learning. Offering a glimmer of hope for recovery, she went on to say:

My depression had been ongoing for two years. I sat down and tried to learn, looking at what I was supposed to learn and reading through. And I tried, tried to listen to the teacher, but I wasn’t able to take in or learn anything. (…). I’m doing better with my depression now, so I’m learning better.

According to Hana, the close follow-up from the healthcare system significantly improved her learning capacity. Her excitement regarding her current learning progress was evident as she concluded: ‘Well, today in class, I’m able to sit there and listen, and I can read and pay attention!’

Gossip – an invisible force. Our findings suggest that both men and women kept their traumatic experiences private to avoid shame, being gossiped about, or felt sorry for at school. One man summarised what several others expressed: ‘In my culture, everyone talks and tell others about your problems.’ Fear of gossip, particularly within his ethnic group and among his classmates, prevented him from seeking psychological help. He was not the only one. Another participant distinguished between refugee students and what he referred to as ordinary immigrants (non-refugees) while explaining his deep reluctance to share how he was doing with classmates: ‘Refugees, unlike ordinary immigrants, immediately understand when you are having a bad day because they are or have been in the same situation.’ Like most of the other participants, he spent much effort hiding his experiences and how he felt. Some participants had high absence rates because they stayed home on bad days, unable to bear the questioning from fellow refugee peers. A third participant stated that because of his depression, classmates gossiped about him a lot, and teachers were unable to intervene: ‘Teachers are just teachers! They asked why I’m staying home, and I answered: To avoid being gossiped about.’

3.8. Reactions to taking part in the interviews

Before the interviews, some participants had looked up the interviewer (first author) online and discovered that she had been an examiner for the Norwegian language oral test for years. At times, such as when meeting with August (23), the interviewer was interviewed by the interviewee about the specific elements in the oral test. Several participants stated they felt more comfortable knowing that the interviewer had experience teaching refugees and was thus used to communicating with second-language learners in challenging life situations. The participants also seemed to perceive the interviewer as a spokesperson for their cause and referred to her as a ‘woman in power.’ At times, the interviewer felt pressure because of what she perceived as expectations of communicating their concerns to stakeholders who would listen to her, and act upon it. She clarified expectations by explaining the role of a researcher.

Furthermore, during the follow-up calls two days after the research interview all expressed gratitude for addressing the study topic with them – even though it was painful. None of the participants wanted a follow-up conversation from a professional. Many invited the interviewer to contact them again whenever she wanted.

4. Discussion

In this study, we aimed to investigate adult refugee learners’ views on whether and how trauma and adversity affected their learning. Although the sample was non-clinical, all of these ordinary adult refugee learners had gone through extreme experiences in their countries of origin and during flight. Some participants, mainly women, faced new adverse life events after resettlement. For these women, threats and abuse in close relationships and sexual exploitation posed a barrier to attending language classes in Norway. Likewise, after resettlement, particularly forced family separation caused psychological distress (depression) for the men, who said this greatly affected their learning outcomes. This finding partially echoes Liddell et al. (2021), who found that forced family separation was associated with increased symptoms of depression. Our interview findings suggested that some participants had been struggling with depression, post-traumatic symptoms, and physical pain for years. In the analysis, we discovered new dimensions of challenges faced by the refugee learners, such as the tremendous burden of dealing with post-migration hardships ‘on top of’ traumatic experiences.

4.1. Lessons from adult learners

The two major themes and interrelated sub-themes extracted from the analyses demonstrated important parts of the participants’ perspectives and personal experiences with the impact of trauma and other stress affecting their learning. Participants held varying beliefs about the impact of trauma on learning, ranging from constant to situational to none. Identified as essential for learning but not always noticeable to teachers were adult learners’ psychological burdens from past and present school experiences, loneliness, depression due to pre- and post-migration trauma and post-migration hardships, and, furthermore, negative social control within their ethnic group.

The sub-theme (Not only) past trauma initially indicated a potential contradiction. On the one hand, the participants, unsolicited, and with great passion, described their often extreme, traumatic pre-migration experiences and how these experiences affected them in many ways, including obstructing their learning. Their narratives shed light on adult learners’ enormous burdens, including sleeping problems, concentration, and memory issues. Our non-clinical study suggests that the academic disadvantage faced by adult learners with PTSD, as outlined by Emdad et al. (2005), also applies to other adult learners without a confirmed PTSD diagnosis. On the other hand, most participants felt that post-migration factors even had a greater negative impact on their learning than pre-migration trauma. These post-migration factors included protracted asylum processes, family separation and concerns about their families’ safety, domestic violence, meeting the requirements for language learning and citizenship, and financial struggles (e.g. unpaid debt to human traffickers). One participant even had great worries about a refund claim for excessive benefits received from the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration [NAV] because of difficulties in understanding information written in a complex language. Although our study focuses on learning, these findings resonate with previous research suggesting resettlement stressors can have a more significant negative impact on mental health than pre-migration trauma (e.g. Li et al., 2016). Nevertheless, instead of interpreting our findings as contradictory, the findings complement each other, emphasising the importance of considering post-migration difficulties alongside traumatic experiences to impede successful learning.

A notable yet minor finding within the sub-theme (Not only) past trauma suggests that rumours about stricter refugee legislation can negatively impact adult refugees’ mental health, concentration and academic performance. This finding aligns with previous research on the detrimental effects of harsh immigration policies and unwelcoming or increasingly hostile post-migration environments on refugees’ mental health (Blackmore et al., 2020; Crawley & Skleparis, 2018). Moreover, we found that negative news about refugees could elicit feelings of hopelessness, meaninglessness, and reduced motivation to study. Our findings underline the importance of considering the psychological impact of refugee-related issues mentioned in the media, including its effect on learning.

August’s narrative provided valuable insight into the personal costs of another source of stress – the language tests used for citizenship regulation purposes – and the increased anxiety that changes in language requirements could entail. Currently, Norwegian citizenship language requirements have risen from oral level A2 to B1. Passing these tests, often known as high-stakes tests, determines access to future education, employment opportunities, residency, and citizenship (e.g. Carlsen & Rocca, 2021). Adult learners’ awareness of the requirements to achieve a specific language proficiency level within a short time frame of a training programme can exacerbate stress levels, leading to difficulties in concentration and learning. These findings align with research suggesting that daily life pressure, expectations and high demands can cause exhaustion and even ill health in adult refugee learners (Horsman, 2000; Nissen et al., 2022; UKOM, 2021). Providing adult learners with the necessary support to manage emotional stress is crucial, as stress also may negatively influence their learning outcomes. Such support may also include information about different factors influencing learning. Therefore, it is concerning that some refugees, such as Ukrainians, are not obligated to attend mandatory courses such as a course on Norwegian society and ‘Coping with life in a new country’ (Integration Act, 2020, Chapter 6A). Consequently, these important resources for support and integration into the host society may be unavailable or restricted.

Our study shows a variation in torture survivors’ beliefs about the impact of torture on learning and mental and physical health. All did not necessarily attribute slow language acquisition to the torture they had suffered. It is also noteworthy that some adult learners in our study believed torture negatively impacted their mental health but were unsure if it affected their learning. Still, the participants’ history of torture should draw adult education’s attention to its potential consequences for learning. Our findings add to the literature on the harmful effects of torture on health, as demonstrated by the research of Hvidegaard et al. (2023).

One torture survivor attributed slow language acquisition to age. Maybe it is easier to relate one’s problems to age rather than to the emotional impact of trauma. At any rate, research shows that cognitive functions tend to decrease with age (Lightbown & Spada, 2021). Nevertheless, the number of adult learners subjected to or witnessing torture in our study is of great concern due to the negative impacts on health (e.g. Hvidegaard et al., 2023; Steel et al., 2009), which can profoundly influence academic outcomes. Finally, Hvidegaard et al. highlighted that torture prevalence, particularly among refugee women, is often underreported. This likely applies to our sample since we did not inquire about the participants’ experiences of torture. Awareness among adult educators also needs to be raised regarding the torture-like experiences described by many of the female participants. Experiences such as being repeatedly raped, beaten, and harassed by a partner, may not be defined as torture but may be equally detrimental to their health and prospects of learning. We learned how such ongoing terror and threats could cause concentration difficulties and hinder school attendance.

Our study also identified a recurring theme of grief, Learning grief, in which attending school as an adult and being unable to meet the requirements elicited a profound sense of loss, mainly related to reduced learning capacity and previously missed school opportunities in their home country. Learning grief also included mourning their inability to attend school in Norway due to health issues, threats, and violence. Thus, Learning grief sheds light on a lesser-known aspect of grief that teachers and the students themselves may be unaware of, potentially impacting students’ learning and academic well-being. The consequences of Learning grief add to the burden of having to deal with grieving the loss of, for example, loved ones, the loss of children being removed from the family, as well as the loss of home country and status.

We furthermore found that feelings of shame and fear can prevent students from disclosing violence in intimate relationships as a reason for their school absences or non-attendance. This finding highlights the importance of educational institutions responding promptly and appropriately to students’ non-attendance. Responding appropriately involves being aware that disclosing domestic violence can endanger the student if the abuser finds out about it. It is worth noting, however, that revealing traumatic experiences can be liberating (Horsman, 2000). Moreover, we found that some adult learners with a long-held dream about education and the opportunity to attend school in Norway were unable to seize it due to psychological distress. Failure to seize such opportunities may undermine refugee learners’ confidence in their ability to learn, potentially limiting opportunities for education and employment and thus impacting their future significantly. Finally, while the impact of grief on adult refugees’ health is well documented (e.g. Nickerson et al., 2014), usually related to the loss of dear ones, a home, a country, and the status one used to have, there appears to be a lack of research on the effects of grief on adult refugees’ academic well-being, which needs further exploration.

In the second overarching theme, The individuals behind the desks, a recurring concern raised by the interviewees was what their teachers might think about their slow academic progress. Only a few adult learners had encountered teachers who addressed traumatic experiences as a potential barrier to academic progress. Findings related to the first sub-theme, The continuing silence, showed that the silence around previous and current traumatic experiences in participants’ educational settings in the reception country could be a painful repetition of the silence they encountered by their teachers in their childhood after having experienced severe adversity and trauma. Such silence in the present impacted their concentration, learning and well-being. As shown by Horsman (2000, pp. 52–57), childhood traumatic experiences in school, such as teachers’ and classmates’ violence, as well as parents’ violence at home, can profoundly influence learning in adulthood. According to our participants, teachers’ silence in adult education may signal fear of re-traumatising the student as well as teachers’ discomfort or lack of knowledge. Similarly, Horsman (2000, e.g. pp. 46, 50, 254) highlights that teachers’ silence around domestic and abusive violence can maintain an illusion that traumatic experiences are rare, private, or unspeakable and shameful. Silence may teach students to maintain silence and continue suppressing their emotions instead of learning how to deal with them. Our findings underline that silence may add to an already heavy burden in learning situations and thereby make learning more difficult for adults struggling with traumatic experiences and post-migration difficulties. Most participants did not want to discuss war and adverse experiences in class, but some refugee learners asked that teachers share current knowledge in class on how stress and trauma may affect learning and well-being. By sharing such knowledge, teachers would demonstrate their understanding of the learners’ potential difficulties and slow learning progress. Moreover, such an approach could shift the focus away from slow learning as a characteristic of the individual (a slow learner) and towards contextual conditions (e.g. the need for adult education’s skill development about adverse life experiences’ impact on learning).