Abstract

Patient: Male, 72-year-old

Final Diagnosis: Cancer of the cecum

Symptoms: Fever

Clinical Procedure: —

Specialty: Bioinformatics

Objective:

Rare coexistence of disease or pathology

Background:

Gas in the portal venous system, or hepatic portal venous gas, is a rare occurrence associated with ischemic colitis, inflammatory bowel disease, or any cause of bowel perforation, including from a necrotic tumor. This report presents the case of a 72-year-old man with diabetes who had carcinoma of the ileocecal region, sepsis due to Klebsiella pneumoniae, and hepatic portal venous gas.

Case Report:

A 72-year-old man with ileocecal cancer was admitted to our hospital for preoperative diabetes control. He developed a fever and septic shock, without abdominal symptoms or signs of peritoneal irritation. Klebsiella pneumoniae was detected in blood cultures. Abdominal ultrasonography showed hepatic portal venous gas, and a simple computed tomography scan revealed gas in the vasculature and hepatic portal vein in the lateral segment, which led us to believe that the ileocecal mass was the source of infection, and emergency surgery was performed. The patient was discharged from the hospital on postoperative day 34 with good progress despite dehydration due to high-output syndrome.

Conclusions:

Sepsis due to necrosis of ileocecal cancer is often difficult to diagnose because it is not accompanied by abdominal symptoms, as in our case. However, abdominal ultrasound is useful because it allows for a broad evaluation. This report has demonstrated and highlighted that the findings of hepatic portal venous gas on imaging should be regarded seriously, requiring urgent investigation to identify the cause and commence treatment in cases of infection or sepsis.

Key words: Colonic Neoplasms, Sepsis, Portal Vein, Colorectal Surgery

Introduction

This report presents the case of a 72-year-old man with diabetes who had carcinoma of the appendix, sepsis due to Klebsiella pneumoniae, and hepatic portal venous gas.

Sepsis and hepatic portal venous gas secondary to colorectal cancer without obstructive colitis have been rarely reported. In recent years, with the widespread use of computed tomography (CT), several cases of hepatic portal venous gas have been reported; however, only a few cases have been detected using abdominal ultrasonography [1].

We describe a case of preoperative sepsis of unknown etiology in a patient with cecal cancer. The discovery of hepatic portal venous gas on abdominal ultrasonography led us to conclude that the sepsis was caused by the collapse of the intestinal defense mechanism, due to necrosis at the tumor site, and we performed emergency surgery to save the patient’s life. Although portal vein gas due to tumor necrosis of colorectal cancer is rare, we believe that it will have a significant impact on future treatment strategies for sepsis associated with colorectal cancer.

Case Report

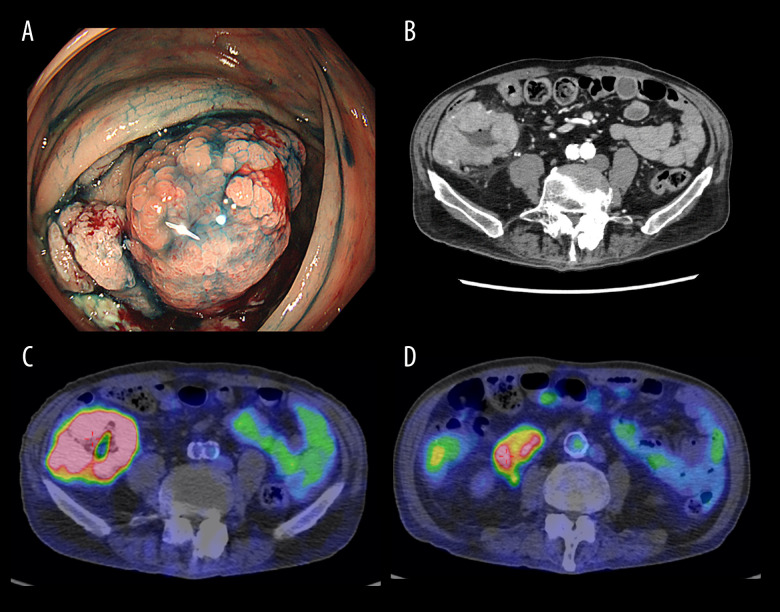

The patient was a 72-year-old man with a history of diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and lower extremity atherosclerosis. During hospitalization for preoperative diabetes control in ileocecal cancer (cT4aN1bM0 H0PPUL cStage IIIc; Figure 1), the patient developed fever, nausea, and septic shock. Vital signs were as follows: pulse 105 beats/min, blood pressure 78/46 mmHg, and temperature 38.3ºC. Physical examination revealed no abdominal or muscular defense or recoil pain. Blood biochemical test values were as follows: white blood cells count 9800 μL, red blood cell count 421×103 μL, hemoglobin 12 g/dL, hematocrit 37.4%, platelet count 28.9×104 μL, levels of blood urea nitrogen 27 mg/dL, creatinine 1.48 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase 17 U/L, alanine transaminase 7 U/L, C-reactive protein 29.8 mg/dL, calcium19-9 5.0 U/mL, and carcinoembryonic antigen <9.0 ng/mL. The patient was dehydrated and exhibited signs of inflammation. Klebsiella pneumoniae was detected in the blood culture.

Figure 1.

(A) Hemorrhagic circumferential ulcer lesion in the ileocecal region. (B) Wall thickening mainly in the cecum. The serosal surface is irregular and fatty tissue density is elevated. There is a lymphadenopathy of less than 6 cm in length in the vicinity of the lesion. (C) SUVmax 13.9 in the primary lesion. There is also irregular wall thickening, suggesting a known mass lesion. (D) Lymph nodes also accumulated with SUV max 5.7.

The blood gas analysis (under air respiration) values were as follows: pH 7.418, partial pressure of oxygen 87.9 mmHg, partial pressure of carbon dioxide 29.1 mmHg, bicarbonate-18.4 mmol/L, and BE-5.2 mmol/L.

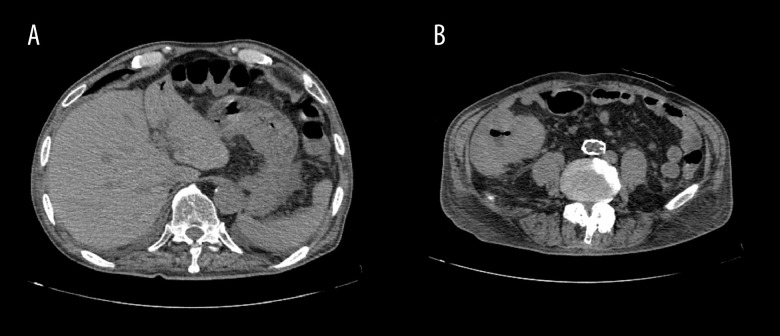

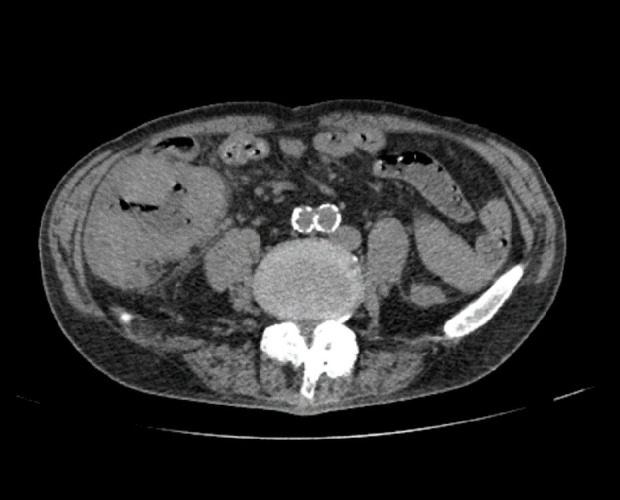

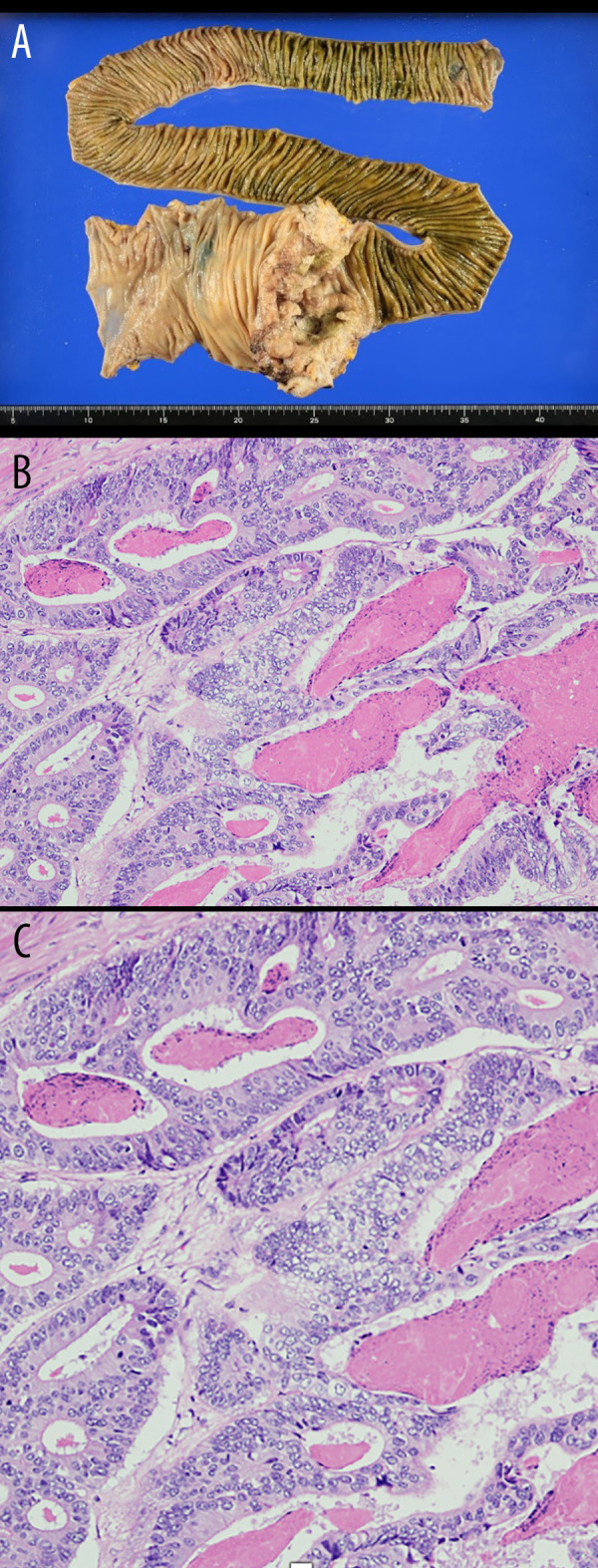

A simple CT scan revealed a mild edematous thickening of the ileal mass, with no evidence of free air, perforation, or abscess formation, which could have caused the shock (Figure 2). Abdominal echocardiography as well as simple CT of the abdomen showed portal venous gas in the lateral area of the liver (Video 1). Sepsis quickly resolved with meropenem antibiotics and infusion therapy. Four days later, the patient developed a fever again, without abdominal symptoms or signs of peritoneal irritation. Abdominal ultrasound revealed hepatic portal venous gas. Simple CT revealed dendritic air in the extrahepatic area, as observed on echography, and gas was observed in the vascular ducts in lateral segment (Figure 3). The patient underwent laparotomy for ileal resection, colostomy, colonic mucosal fistula, and D3 lymph node dissection. Postoperatively, the inflammatory response improved quickly, and the portal gas disappeared on bedside ultrasonography. Pathological examination revealed pT3, N2a, M0, and fStage IIIb tumors and showed no evidence of bacterial infection (Figure 4); however, the tumor was highly necrotic and was considered the cause of sepsis on postoperative day 34. The patient showed good progress despite dehydration, due to high-output syndrome.

Figure 2.

The patient experienced septic shock. The mass is only mildly edematous and thickened, with no evidence of free air or abscess formation.

Video 1.

Ultrasonography shows portal vein gas.

Figure 3.

The patient had fever again after recovery, with portal vein gas. (A) Simple computed tomography scan shows portal vein gas in the lateral area. (B) Primary tumor is edematous, no free air.

Figure 4.

Pathological examination. (A) Moderately differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma: tub 2 > tub 1. pT3(SS), lymph node; [#201(0/5), #202(4/6), #203(0/0)]. (B) Severe tumor necrosis. No bacteria were observed in the tissues. (C) A photomicrograph of the histopathology of the primary adenocarcinoma of the ileocecal region in a 72-year-old man with diabetes. The histopathology shows an adenocarcinoma with gland formation, cells with cytological atypia, mitoses, and areas of inflammation and necrosis, consistent with a moderate to high grade adenocarcinoma. Hematoxylin and eosin. Magnification × 40.

Discussion

Hepatic portal venous gas is a relatively rare complication of intestinal necrosis but is associated with high mortality and poor prognosis [2]. In 1955, Wolfe et al found gas images on the abdominal radiographs of 6 cases of neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis that were consistent with hepatic portal venous gas migration, and an autopsy confirmed the presence of hepatic portal venous gas [3]. Later, in 1960, Susman et al first reported this case in an adult patient [4]. In 1978, Liebman et al identified damage to the gastrointestinal mucosa, including intestinal infarction and ulceration, increased intestinal pressure due to gas retention, and sepsis, including the presence of gas-producing bacteria in the blood and intestinal necrosis, as factors in the occurrence of portal gas. This study included 64 patients with hepatic portal venous gas, with a fatal mortality rate of 75% [5].

In the present case, Klebsiella pneumoniae invaded the blood vessels from the mucosal surface because of internal necrosis of the colorectal cancer, resulting in portal gas and septic shock. In addition, the factors that lead to tumor necrosis are thought to be a combination of factors, including bacterial infection in the intestinal tract, increased intestinal pressure due to obstruction, impaired mucosal blood supply due to smooth muscle spasm associated with increased peristalsis, and microvascular lesions due to diabetes mellitus. Our patient also had diabetes mellitus and was prone to infection.

In a prognostic study of 20 patients (14 women and 6 men; mean age 75.4 years) with hepatic portal venous gas, 4 patients underwent emergency surgery, and 16 patients received conservative treatment, with an overall in-hospital mortality rate of 25% [6,7].

Moser et al also reported a fatality rate of > 50% in cases of combined hepatic portal venous gas and bowel necrosis [8,9]. However, in recent years, reports of hepatic portal venous gas of benign etiology have increased with the widespread use of CT, which may be a factor contributing to the lower mortality rate in patients with findings of hepatic portal venous gas [10]. Wayne et al demonstrated that the treatment strategy for hepatic portal venous gas should be based on the underlying disease, and that the indication for emergency surgery should be determined by the underlying disease, given the high mortality rate associated with bowel necrosis [11]. Regarding the relationship between colorectal cancer and sepsis, sepsis caused by Streptococcus bovis has been previously reported, although not in the present case. In some cases, clusters of fungi were observed by Gram staining [12].

Diagnosing septic shock due to bacterial translocation, as in the present case, is difficult. In our case, abdominal ultrasound enabled a rapid response to changes in symptoms over time, and the detection of hepatic portal venous gas led to the diagnosis of a breakdown in the mucosal defense mechanism of colorectal cancer. Emergency surgery was performed to save the patient’s life. There have been few reports of cases in which hepatic portal venous gas was diagnosed by abdominal ultrasound and emergency surgery was performed. We believe that this technique is useful for the diagnosis of hepatic portal venous gas because it allows easy evaluation over time. Our patient’s HbA1c level was 6.5, and his blood glucose level was controlled using preoperative diet control. During hospitalization, his blood glucose level was generally below 200 mg/dL and was under control. On day 10 after admission, he developed septic shock with fever and hypotension. We performed laparotomy for ileal resection, colostomy, colonic mucous fistula, and D3 lymph node dissection in this case, but anastomosis can also be considered depending on the operative findings and the patient’s condition. At present, there are only a few reports of septic shock resulting from tumor necrosis due to colorectal cancer. With the recent proliferation of imaging tests, such as CT and abdominal echography, the detection of portal vein gas can help in early intervention. Many cases of colorectal cancer tumor necrosis associated with portal vein gas are considered to have gone unnoticed because portal vein gas was not discovered at the time, as was the case in the present investigation.

Conclusions

Sepsis due to necrosis of colorectal cancer is often difficult to diagnose because it is not accompanied by abdominal symptoms, as in our case. However, abdominal ultrasound is useful because it allows evaluation over time. When sepsis of an unknown etiology is observed before colorectal cancer surgery, tumor necrosis should be considered when treating the patient. This report has demonstrated and highlighted that the findings of hepatic portal venous gas on imaging should be regarded seriously, requiring urgent investigation to identify the cause and commence treatment in cases of infection or sepsis.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher

Declaration of Figures’ Authenticity

All figures submitted have been created by the authors who confirm that the images are original with no duplication and have not been previously published in whole or in part.

References:

- 1.Li Z, Su Y, Wang X, et al. Hepatic portal venous gas associated with colon cancer: A case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(50):e9352. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000009352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kinoshita H, Shinozaki M, Tanimura H, et al. Clinical features and management of hepatic portal venous gas: Four case reports and cumulative review of the literature. Arch Surg. 2001;136(12):1410–14. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.136.12.1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolfe JN, Evans WA. Gas in the portal veins of the liver in infants; A roentgenographic demonstration with postmortem anatomical correlation. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1955;74(3):486–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Susman N, Senturia HR. Gas embolization of the portal venous system. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1960;83:847–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liebman PR, Patten MT, Manny J, et al. Hepatic – portal venous gas in adults: Etiology, pathophysiology and clinical significance. Ann Surg. 1978;187(3):281–87. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197803000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y, Liu HL, Tang M, et al. Clinical features and management of 20 patients with hepatic portal venous gas. Exp Ther Med. 2022;24(2):525. doi: 10.3892/etm.2022.11452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou C, Kilpatrick MD, Williams JB, et al. Hepatic portal venous gas: A potentially lethal sign demanding urgent management. Am J Case Rep. 2022;23:e937197. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.937197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moser A, Stauffer A, Wyss A, et al. Conservative treatment of hepatic portal venous gas consecutive to a complicated diverticulitis: A case report and literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;23:186–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2016.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kesarwani V, Ghelani DR, Reece G. Hepatic portal venous gas: A case report and review of literature. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2009;13(2):99–102. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.56058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ginesu GC, Barmina M, Cossu ML, et al. Conservative approach to hepatic portal venous gas: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2017;30:183–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2016.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wayne E, Ough M, Wu A, et al. Management algorithm for pneumatosis intestinalis and portal venous gas: Treatment and outcome of 88 consecutive cases. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14(3):437–48. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-1143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suzuki T, Ichikawa S, Kashiwagura S, et al. A case of sigmoid colon cancer with septic shock due to Streptococcus bovis. Japanese Journal of Clinical Surgery. 2016;77(8):2000–6. [Google Scholar]