Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Adequate bowel preparation is paramount for a high-quality screening colonoscopy. Despite the importance of adequate bowel preparation, there is a lack of large studies that associated the degree of bowel preparation with long-term colorectal cancer outcomes in screening patients.

METHODS:

In a large population-based screening program database in Austria, quality of bowel preparation was estimated according to the Aronchick Scale by the endoscopist (excellent, good, fair, poor, and inadequate bowel preparation). We used logistic regression to assess the influence of bowel preparation on the detection of different polyp types and the interphysician variation in bowel preparation scoring. Time-to-event analyses were performed to investigate the association of bowel preparation with postcolonoscopy colorectal cancer (PCCRC) death.

RESULTS:

A total of 335,466 colonoscopies between January 2012 and follow-up until December 2022 were eligible for the analyses. As compared with excellent bowel preparation, adenoma detection was not significantly lower for good bowel preparation (odds ratio 1.01, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.9971–1.0329, P = 0.1023); however, adenoma detection was significantly lower in fair bowel preparation (odds ratio 0.97, 95% CI 0.9408–0.9939, P = 0.0166). Individuals who had fair or lower bowel preparation at screening colonoscopy had significantly higher hazards for PCCRC death (hazard ratio for fair bowel preparation 2.56, 95% CI 1.67–3.94, P < 0.001).

DISCUSSION:

Fair bowel preparation on the Aronchick Scale was not only associated with a lower adenoma detection probability but also with increased risk of PCCRC death. Efforts should be made to increase bowel cleansing above fair scores.

KEYWORDS: colorectal cancer screening, bowel preparation, colonoscopy quality, colorectal cancer mortality

INTRODUCTION

Screening colonoscopy is considered the gold standard for the detection and removal of colorectal polyps, thereby preventing colorectal cancer (CRC) and related deaths (1). The notion that CRC screening is most effective when performed under high quality led to the development of multidisciplinary guidelines for CRC screening of average-risk individuals by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (2).

Postcolonoscopy CRC (PCCRC) is an adverse outcome of colonoscopy-based CRC screening programs and includes CRC that develops after a presumably CRC-free colonoscopy has been performed (3). Several factors have been associated with PCCRC, which can either be attributed to patient (polyp) characteristics or procedural (endoscopist) factors (4). As such, the degree of bowel preparation has been discussed as a contributor to PCCRC. Already in the early 2000s, guidelines recommended that bowel preparation for colonoscopy should be adequate to ensure efficient detection of colonic polyps (5). To quantify the extent of bowel preparation, several scales have been developed, such as the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS), the Ottawa Scale, and the Aronchick Scale (6–8). The use of 1 of these 3 scales is recommended in current society guidelines (9,10). Suboptimal bowel preparation leads to incomplete colonoscopies and hampers the detection of colonic neoplasia; therefore, a minimum standard for these bowel preparation scales was proposed (9). Although the BBPS has prevailed as the most validated rating scale, the Aronchick Scale is easy to use due to its 5-tier system (11,12).

However, these scales are highly operator dependent, and the rating is strongly influenced by preference and experience of the endoscopists (13).

Currently, no study has quantified the polyp findings according to bowel preparation in a large CRC screening cohort and linked this quality parameter to the long-term mortality on CRC occurring after screening colonoscopy. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to (i) determine the detection probability of polyps in different qualities of bowel preparation, (ii) quantify the physician influence on bowel preparation rankings, and (iii) integrate these findings into the context of bowel preparation quality in PCCRC deaths of screening patients.

METHODS

Study design and cohort

We conducted a retrospective observational study including individuals who underwent screening colonoscopy in Austria. The study population is derived from colonoscopies that were contributed to the Austrian quality certificate for screening colonoscopy, the “Qualitätszertifikat Darmkrebsvorsorge,” which was founded in 2007. The purpose of the voluntary program was to monitor the quality of screening colonoscopies performed in Austria's opportunistic screening program, introduced in 2005. The quality certificate's database is built by physicians who upload the information of their screening colonoscopies, which includes quality parameters such as the completeness of the colonoscopy, bowel preparation, use of sedation, the histologic diagnosis of the most advanced pathology, and the management of pathologies (biopsy or removal). The correctness and completeness of the uploaded records is audited twice a year, with 3 random samples of original colonoscopy reports that need to be provided by every participating endoscopist. Details and rationale of the Austrian quality certificate for screening colonoscopy have been extensively described before (14,15).

We included persons aged 50 years or older with a screening colonoscopy between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2022. The study period was set to start in 2012 because reporting of bowel preparation became a mandatory requirement in this year. Nevertheless, bowel preparation information was missing for 18,339 screening participants who had to be excluded from the study. Persons with CRC diagnosed at screening were excluded. Only the index colonoscopy was included in the analyses. Because there is only limited information on surveillance colonoscopies in the database, we could not include early repeat colonoscopies due to inadequate bowel preparation in the study.

The study period was also chosen due to the availability of data on CRC deaths in this cohort. A database linkage with the central registry of deaths of Austrian residents provided by Statistics Austria was performed, where data were available until December 31, 2022. Information of deaths was provided as date of death with International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes of causes of death (16,17).

The Austrian nation-wide mandatory health insurance plan recommends screening for individuals at or above the age of 50 years. In addition, an expanded recommendation exists for individuals with a positive family history of CRC, where screening is initiated when the individual is 10 years younger than the first-degree relative's age of CRC diagnosis. Persons over the age of 40 years with a positive fecal occult blood test as part of a health checkup are also eligible for screening colonoscopy. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the Medical University of Vienna (EK 1559/2023).

Variable definitions

Bowel preparation is recorded in the database as a mandatory field for the colonoscopy upload form. Endoscopists report bowel preparation by the 5-point Aronchick Scale, thereby reporting whether bowel preparation was “excellent,” “good,” “fair,” “poor,” or “inadequate” (8). In case of incomplete colonoscopy, endoscopists need to report the cause, which can be due to complications, pain, stenosis, poor, or inadequate bowel preparation or other reasons. A death of CRC was considered when the death registry entry recorded the codes C18, C19, or C20, whereas deaths of any other International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision code were considered deaths of other causes. High-risk polyps were defined according to current guidelines by the European Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE; polyps ≥10 mm, adenomas with high-grade dysplasia, serrated polyps with dysplasia, ≥5 adenomas).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses.

Descriptive statistics were used to report the mean with SD and the median with the 25th and 75th percentile for continuous variables where applicable and report absolute and relative frequencies of sex, polyp size, number of polyps, cecal intubation, and reasons for incomplete colonoscopy by degree of bowel preparation. In addition, we calculated percentages of polyp findings by bowel preparation.

Bowel preparation and PCCRC mortality.

The association of bowel preparation with the primary outcome, time to CRC death, was determined using a cause-specific Cox proportional hazards model adjusted for screening participants' sex and age, where deaths of other causes were considered competing events. Follow-up time was measured from the date of screening colonoscopy until either the occurrence of death from PCCRC or other cause death. All other screening participant's follow-up time was right-censored at the end of the study period (December 31, 2022). We performed a sensitivity analysis where we included colonoscopy completeness (“yes” or “no”) as a variable, to adjust for cecal intubation influencing CRC mortality risk. Hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using robust standard errors were reported. As quality metrics, such as the adenoma detection rate (ADR) and polyp characteristics are associated with PCCRC, we performed additional analyses with adjustments for these variables. Because a surveillance colonoscopy can modify the risk of subsequent PCCRC, we performed an additional sensitivity analysis where screening participants' follow-up time was censored at the time of a surveillance colonoscopy. Like in the logistic regression models, 95% CIs were calculated by using robust standard errors due to the clustering of endoscopists. Model assumptions of proportionality were assessed by Shoenfeld test. We estimated the 10-year cumulative CRC mortality after screening colonoscopy with death from other causes as a competing event.

Variation of bowel preparation rating between endoscopists.

To assess the probability of having excellent bowel preparation vs any other degree of bowel preparation in the context of the observations being clustered at the endoscopist level, we used a mixed-effects logistic regression model. Screening participant's age and sex were included as fixed effects in the model as possible confounders and the endoscopist contributing the observation as a random effect with random intercepts. In addition, a separate analysis was performed where we added the endoscopist's ADR as a random effect with random slopes to the model. To account for nonlinear effects of age on the probability to have one of the bowel preparation scores, we fitted a model with age as a natural spline with 2 knots. The final model (with age as a continuous variable or with age as a natural spline) was chosen based on Akaike Information Criterion.

Similarly, we fitted a mixed-effects model for “good” or “excellent” vs any other quality of bowel preparation as the outcome and 1 model with “fair” or better levels of bowel preparation vs “poor/inadequate” bowel preparation. We calculated the variance between endoscopists' bowel preparation ratings. Furthermore, we aimed to characterize the variation of bowel preparation ratings between endoscopists in contrast to the variation of bowel preparation degrees between individual patients. Therefore, intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) of agreement were calculated to determine the variance that can be explained by the grouping of endoscopists (18). To calculate the ICC, we divided the variance of the random effects by the total variance of the model (residual variance and random effect variance) (18,19). The ICC ranges from 0 to 1. A high ICC means that bowel preparation variability is mostly explained by the grouping structure (endoscopists). A value closer to 0 indicates that most of the variance is due to individual differences of patients in an endoscopist cluster, with little variation between endoscopists.

Bowel preparation and polyp detection.

To determine effect of bowel preparation on the probability of detecting an adenoma, a serrated polyp, or a high-risk polyp, we used a logistic regression model adjusting for age and sex. We performed these analyses with (i) “excellent” bowel preparation as the reference category and (ii) “excellent/good” bowel preparation as the reference category. We calculated odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs for these models. For statistical testing, we set a significance level of P < 0.05. R version 4.3.0 was used for the analyses, using the survminer, lme4, and performance package.

RESULTS

Bowel preparation scores and baseline findings

A total of 368,357 colonoscopies between January 2012 and December 2022 were eligible for inclusion in the study. We excluded 2,783 colonoscopies where CRC was detected at screening, 11,769 individuals younger than 50 years, and 18,339 where bowel preparation information was missing. This led to a final study cohort of 335,466 colonoscopies in our analyses. Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics by degree of bowel preparation. Of the included individuals, 50.92% were female, and the median age of the cohort was 60.0 years. Overall, 125,439 (37%) colonoscopies had excellent bowel preparation, 159,719 (48%) had good bowel preparation, 37,943 (11%) had fair bowel preparation, 9,440 (3%) had poor bowel preparation, and 2,925 (1%) colonoscopies had inadequate bowel preparation. In 2013, 1 year after the introduction of bowel preparation recording, excellent or good bowel preparation was recorded in 9,413 (36.0%) and 12,582 (48.1%) screening colonoscopies, while 3,111 (11.9%), 803 (3.1%), and 252 (1.0%) screening colonoscopies had fair, poor, or inadequate bowel preparation. In 2022, excellent bowel preparation was reported in 16,285 (43.4%) colonoscopies, good bowel preparation was reported in 16,114 (43.0%) colonoscopies, fair bowel preparation was reported in 4,076 (10.9%) colonoscopies, and poor bowel preparation was reported in 722 (1.9%) colonoscopies, while inadequate bowel preparation was observed in 309 (0.8%) colonoscopies. The reported bowel preparation degrees by year since the start of the recording can be seen in Supplementary Figure 1 (see Supplementary Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/AJG/D291). The mean age of screening participants was higher with each worsening bowel preparation rank, with a mean age of 61.12 years (SD 8.53) in individuals with excellent bowel preparation and a mean age of 62.71 years (SD 9.36) in individuals with inadequate bowel preparation. Although there were 3.75% more women in the cohort, excellent bowel preparation frequency was 13% higher in women compared with men. The colonoscopy completeness, indicated by reaching the coecum, was less likely with worsening degrees of bowel preparation. 98.31% of colonoscopies with excellent bowel preparation were completed, while this was true for 98.01% of colonoscopies with good bowel preparation. While still 97.59% of fair colonoscopies were completed, the cecum was reached in 90.13% of cases of colonoscopies with poor bowel preparation. In only 58.56% of colonoscopies with an inadequate bowel preparation, the coecum was reached. Reasons for incomplete colonoscopies are depicted in Supplementary Table 1 (see Supplementary Digital Content 5, http://links.lww.com/AJG/D295). Of the 41.44% and 9.87% of incomplete colonoscopies in inadequate or poor colonoscopies, the reason for incomplete colonoscopy was insufficient bowel preparation in 1,145 (94.47%) and 732 (78.46%) of examinations. Overall reporting of follow-up colonoscopy was low, with up to 77.33% of inadequate colonoscopies missing recommended follow-up intervals (see Supplementary Table 2, Supplementary Digital Content 5, http://links.lww.com/AJG/D295). Of colonoscopies where follow-up recommendations were provided, the median recommended follow-up interval was 12 months in colonoscopies with inadequate bowel preparation. The median recommended follow-up interval was 36 months in colonoscopies with fair bowel preparation and with good bowel preparation (see Supplementary Table 2, Supplementary Digital Content 5, http://links.lww.com/AJG/D295).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics, cecal intubation and polyp characteristics by bowel preparation degree

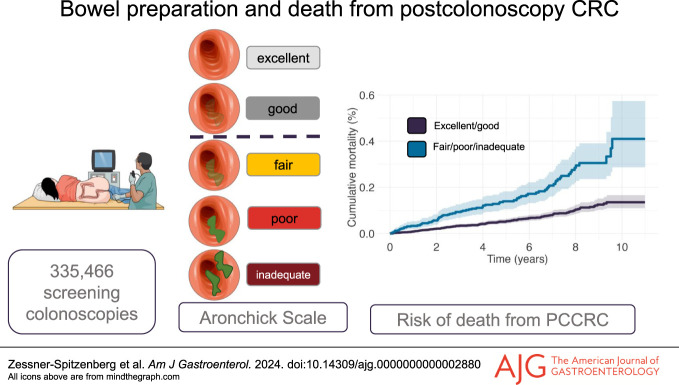

Bowel preparation and CRC death

The median follow-up was 4.60 years (95% CI 4.59–4.62). There were 242 PCCRC deaths in 1.57 million person-years at a follow-up period of up to 11 years, corresponding to a death rate of 15.45 deaths per 100,000 person-years. 10.05 deaths per 100,000 person-years occurred in individuals with excellent bowel preparation, 13.60 deaths per 100,000 person-years occurred after a colonoscopy with good bowel preparation, 31.42 deaths per 100,000 person-years were observed in fair bowel preparation, and 36.01 as well as 58.66 deaths per 100,000 person-years in poor or inadequate bowel preparation, respectively. We found that the hazards for death from CRC were significantly higher in colonoscopies with fair preparation (HR 2.56, 95% CI 1.67–3.94, P < 0.001, Figure 1), poor preparation (HR 2.88, 95% CI 1.63–3.94, P < 0.001), and inadequate preparation (HR 4.66, 95% CI 2.1–10.34, P < 0.001, Figure 1). Even when adjusting for cecal intubation, fair bowel preparation was still significantly associated with CRC death (HR 2.48, 95% CI 1.63–3.78, P < 0.001, see Supplementary Figure 2, Supplementary Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/AJG/D292). The estimates of our sensitivity analysis, where screening participants were censored at the time of follow-up colonoscopy, were comparable with our main analysis (see Supplementary Table 3, Supplementary Digital Content 5, http://links.lww.com/AJG/D295). In addition, in a model adjusting for polyp characteristics, adenoma detection, and proximal serrated polyp detection, the estimates for bowel preparation remained significant (see Supplementary Table 4, Supplementary Digital Content 5, http://links.lww.com/AJG/D295). 10-year cumulative CRC mortality was 0.14% (95% CI 0.11%–0.17%) in screening participants with good or excellent bowel preparation and 0.41% (95% CI 0.29%–0.57%) in participants with fair or worse bowel preparation (Figure 2). The cumulative CRC mortality by all degrees of bowel preparation can be seen in Supplementary Figure 3 (see Supplementary Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/AJG/D293). For screening participants where bowel preparation information was lacking (n = 18,339), and who therefore were excluded from the study, the cumulative PCCRC mortality is depicted in Supplementary Figure 4 (see Supplementary Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/AJG/D294). The 10-year cumulative mortality of PCCRC was 0.18% (95% CI 0.12%–0.27%) in this group. Overall, of the excluded colonoscopies, the cecum was not intubated in 712 (3.9%) colonoscopies. Reasons for incomplete colonoscopy were poor bowel preparation (not further specified) in 141 (19.8%) participants.

Figure 1.

Forest plot with hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals. Bowel preparation was included in the model with excellent bowel preparation as the reference. The estimates were adjusted for screening participant's age and sex.

Figure 2.

Cumulative colorectal cancer mortality since time from colonoscopy in screening participants that had either “excellent” or “good” bowel preparation at screening colonoscopy, as compared with individuals with “fair”, “poor”, or “inadequate” bowel preparation. Estimates were calculated accounting for deaths from other causes as competing risk. PCCR, postcolonoscopy colorectal cancer.

Physician effect on bowel preparation rating

Since bowel preparation is a subjective rating based on the endoscopist's intuition, we were interested in the variability of endoscopist rating in different degrees of bowel preparation. We found that the endoscopist-dependent variance was greatest between the scores excellent vs any other degrees (σ2 4.366, ICC 0.57, Table 2), compared with the rating of good or excellent vs other degrees (σ2 1.019, ICC 0.237), or fair and above vs other degrees (σ2 0.857, ICC 0.207). When adding the endoscopist's ADR to the model estimating the probability of excellent bowel preparation rating, the ICC increased to 0.77.

Table 2.

Results of the mixed-effects model considering clustering of observations at the level of endoscopists

Effect of bowel preparation on polyp detection

We found that there was a significant association of bowel preparation score with the probability to either detect an adenoma, a high-risk polyp or a serrated polyp, when considering excellent bowel preparation as the reference (Table 3), as well as when considering excellent/good bowel preparation as the reference category. While the odds for detecting an adenoma were not significantly lower for good bowel preparation (OR 1.01, 95% CI 0.9971–1.0329, P = 0.1023), they were lower for fair (OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.9408–0.9939, P = 0.0166), poor (OR 0.76, 95% CI 0.7199–0.8005, P < 0.001), and inadequate bowel preparation (OR 0.44, 95% CI 0.3948–0.4924, P < 0.001). The odds for the detection of high-risk polyps were lower in colonoscopies with any degree of bowel preparation lower than excellent; however, the estimates were similar in good (OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.9253–0.986, P = 0.0046) and fair bowel preparation (OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.9342–1.0292, P = 0.4261), although this was not significant. The probability of detecting sessile serrated lesions (SSLs) or traditional serrated adenomas (TSAs) was also significantly associated with bowel preparation. The odds for detecting an SSL/TSA were lower in colonoscopies with good preparation (OR 0.84, 95% CI 0.8022–0.876, P < 0.001) and fair (OR 0.83, 95% CI 0.7728–0.89, P < 0.001) bowel preparation. When combining excellent/good bowel preparation in 1 reference category, fair bowel preparation was still significantly associated with a lower probability to detect adenomas (0.96, 95% CI 0.9347–0.9837, P = 0.0013).

Table 3.

Association of bowel preparation degree with the probability of detecting an adenoma, high-risk polyp, or SSL

DISCUSSION

In this large population-based CRC screening cohort, we investigated how the degree of bowel preparation according to the Aronchick Scale influences the detection of polyps during screening colonoscopy and thereby affects long-term outcomes for screening participants. With worsening degrees of bowel preparation, the odds of detecting an adenoma, high-risk polyp, SSL, or TSA significantly decreased. The detection of adenomas was more than half less likely in screening participants who had inadequate bowel preparation (OR 0.44, 95% CI 0.3948–0.4924, P < 0.001), with a similar pattern for the detection of SSL or TSA (OR 0.53, 95% CI 0.4032–0.7079, P < 0.001). The lower the degree of bowel preparation, the higher was the risk of PCCRC death in the cohort, where hazards for PCCRC death were already significantly higher for screening participants with fair bowel preparation (HR 2.56, 95% CI 1.67–3.94, P < 0.001), even when adjusting for colonoscopy completeness. Although individuals with a good bowel preparation score had a trend for marginally higher hazards for PCCRC death, these were not significant (HR 1.23, 95% CI 0.84–1.8, P = 0.282). Taken together, our findings further support the evidence that bowel preparation is a crucial element of high-quality colonoscopy that affects CRC outcomes in screening participants.

Despite the wide-spread agreement that bowel preparation should be adequate in screening colonoscopy, the degree of bowel preparation that is deemed adequate has not yet been validated with long-term patient PCCRC mortality after screening colonoscopy. Current guidelines of the ESGE suggest that on average, the target rate of screening participants with adequate bowel preparation should be 95%–98% (9,10). In the European recommendation, adequate bowel preparation is defined as a Boston Bowel Preparation Score ≥6 or at least “fair” on the Aronchick Scale (9). However, these data are based on cohort studies that compared the detection of polyps, adenomas, or advanced adenomas as the surrogate outcome, and not the incidence of PCCRC or related deaths. Our data imply that considering “fair” bowel preparation as adequate might not be sufficient when aiming for the lowest possible rate of PCCRC deaths in screening participants. Implications of lowering the threshold of adequate preparation to only “excellent” and “good” might increase the number of repeat colonoscopies being performed, which increases the workload to endoscopy units and increases to healthcare costs. Asides from colonoscopies, healthcare spendings might rise due to a surge in hospital bed use, extended hospital stays, and treatment of complications. To avoid a possible drop in cost-effectiveness of screening colonoscopy, bowel preparation itself must become more efficient. Patient stratification based on probability of poorer bowel preparation (elder screening participants, male participants) and intensified patient education might help mitigate this problem. Patient education should focus on evidence-based measures for bowel cleansing optimization. As such, split-dose bowel preparation with the second dose 3–8 hours before the examination should be the preferred bowel preparation regimen (20,21). In addition, sufficient fluid intake is essential for proper bowel cleaning, alongside dietary restrictions (consumption of a liquid diet the day before the scheduled colonoscopy) (21,22).

A meta-analysis by Clark and colleagues compared the ADRs in 3 different rating scores on the Aronchick Scale (excellent/good, intermediate, poor/inadequate). The authors found no significant difference in ADR between a high-quality preparation vs intermediate preparation, and the pooled OR for intermediate vs low-quality preparation clearly favored the intermediate level above the poor/inadequate level (12). Even on a 4-point scale (excellent/good/fair/poor), the detection of adenomas was not significantly different between optimal or intermediate preparation in a cross-sectional study of 13,022 colonoscopies (23). In our study, we found that when considering excellent bowel preparation or excellent/good bowel preparation as the reference, adenoma detection probability was significantly lower in fair bowel preparation. In addition, there was a significant association with CRC death in screening participants already with fair bowel preparation, with a risk that was more than twice as high as compared with individuals with excellent preparation. As bowel preparation affects cecal intubation (24), we adjusted our estimates for colonoscopy completeness in a sensitivity analysis, where the risk of PCCRC death was still significantly higher in screening participants with fair bowel preparation. These findings suggest that a lower detection ability of adenomas due to poor visualization of the whole colonic mucosa might be the biggest contributor to CRC mortality risk in individuals with fair, poor, or inadequate bowel preparation. Interestingly, we found that the mean number of polyps was higher by worsening degrees of bowel preparation. Moreover, the likelihood to detect polyps was higher by worsening bowel preparation scores. A higher prevalence of increased age and male sex might have contributed to these surprising findings. Nevertheless, the probability to detect adenomas decreased with worsening bowel preparation scores. Sherer and colleagues demonstrated that there was a decrease in detection of polyps with advanced histology (villous histology, high-grade dysplasia, adenocarcinomas) which were small (<10 mm) in patients with poor bowel preparation (25). However, the scoring system of this study only included 3 levels. In our study, we used the Aronchick Scale, which is more nuanced since it has 5 levels to choose the extent of bowel preparation form. The adenoma detection in colonoscopies with fair bowel preparation was only 4 percentage points lower compared with excellent bowel preparation; however, this difference might already contribute to a higher PCCRC mortality risk. Previous studies showed that with every percentage point increase in ADR, the risk of PCCRC decreases by 2–3 percentage points (4,26–28).

The rating of bowel preparation is a subjective measure, which might be depending on the endoscopist's preferences and experience. It has been hypothesized that endoscopists who are low performers in adenoma detection are also the ones who, on average, have more patients with lower bowel preparation levels, explaining the high interphysician variability in ADR (29). However, data from the UK flexible sigmoidoscopy trial suggested otherwise (13). Endoscopists who were low performers more frequently judged bowel preparation to be better, compared with endoscopists who were high performers (13). This indicates higher confidence in judgment of sufficient bowel preparation in low ADR endoscopists. In our study, we observed the highest variance ratings between excellent and lower bowel preparation scores, compared with the cutoff of excellent/good bowel preparation vs lower scores. However, since the likelihood of adenoma detection between excellent and good bowel preparation is similar, and there is no higher risk of PCCRC mortality in screening participants in good vs excellent preparation, the endoscopist-effect mediated to these outcomes might only be marginal.

Strengths of our study include the large cohort based entirely on primary screening colonoscopies. In this study, we used time to PCCRC death as a long-term patient outcome and estimated its association with the bowel preparation degrees and did not use a surrogate outcome such as adenoma detection or size of detected polyps as an approach to determine adequate bowel preparation.

A main limitation of this study is the lack of risk factors of CRC, such as lifestyle aspects, the socioeconomic status of study participants, or comorbidities. Hence, we cannot exclude residual confounding in the group of fair or worse bowel preparation, leading to high mortality rates in this group. In our study, we did not have access to incident CRC of study participants. The data on incident CRC might have helped in understanding the trajectory from a colonoscopy with suboptimal bowel preparation to the death from PCCRC. In addition, it would have helped to assess the cancer stages of PCCRC. Another limitation of this study is the lack of follow-up colonoscopies of scheduled recalls. Surveillance colonoscopies were excluded from the analysis because the follow-up information for screening participants is incomplete. Surveillance colonoscopy ultimately alters PCCRC risk when screening participants follow the recommended follow-up intervals. Therefore, a possible bias from the lack of surveillance colonoscopy information cannot be excluded. Nevertheless, our sensitivity analysis including the 18,670 surveillance colonoscopies where screening participants were censored at follow-up colonoscopy showed comparable results with our main analysis. However, we did have information on the recommended interval of follow-up. The repeating of colonoscopy based on inadequate bowel preparation is recommended by endoscopic societies (22). However, there might be a high confidence of appropriate colonoscopy quality in endoscopists who rated the colonoscopy as “fair”, since current guidelines consider this level of bowel preparation as “adequate”. In inadequate colonoscopies where information on follow-up recommendations was available, follow-up colonoscopy was recommended in a median of 12 months, which is in line with current guidelines (22). However, recommended median intervals were longer for persons with poor or fair bowel preparation (36 and 24 months), longer than the recommended interval in the guidelines. There was a marginal difference in missingness (66.38% vs 65.79%), and no difference in the median recommended follow-up interval (36 months) between colonoscopies with good or fair bowel preparation.

Our results might have limited generalizability to US cohorts, which, depending on the age and sex of patients, have a surveillance rate for adenomas between 5.7% and 30.6% (30).

In this study, we had to exclude 18,339 screening participants due to lacking bowel preparation information, although the bowel preparation degree was introduced as a mandatory field in the database in 2012. Of these colonoscopies, overall PCCRC mortality was high, which might be explained by a lower colonoscopy completion rate than in the whole study cohort. In only 19.8% of the incomplete colonoscopies, the reason for incomplete colonoscopy was in fact poor bowel preparation; however, the exact degree of bowel preparation was unknown, which is a limitation of this study.

In addition, the database lacks information on bowel preparation solutions and preferences of endoscopists on purgatives for their patients or whether split dosing was applied. This might give important insights on the variation of bowel preparation degrees and tolerability of screening participants between endoscopists (31). However, in a prospective study of 5,000 individuals in the Austrian Quality Assurance patient population, bowel preparation quality was comparable between low-volume preparation (300 mL sodium picosulfate), intermediate volume (2 L polyethylene glycol + ascorbic acid and sodium ascorbate), and high-volume (HV, 4 L polyethylene glycol) purgatives (32). In this study by Waldmann et al, endoscopists recommended their preferred bowel cleansing solutions to patients, where 58.5% used a low-volume solution, 16.2% used a HV solution, and 25.3% used an intermediate-volume solution. HV and low-volume purgatives reached an adequate bowel preparation rate of 97.6% and 97.2%, respectively. Intermediate-volume solutions had high success rates (95.3%); however, it was significantly worse compared with low-volume and HV purgatives (32). The colonoscopy database reporting system lacks information on other bowel preparation scales such as the BBPS or the Ottawa Scale. Although the Aronchick Scale has a corresponding cutoff of “adequate” to the BBPS, the BBPS is a valid and reliable measure acknowledged by the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (21) and is considered the preferred scale by the ESGE (9). The BBPS has been well established in American CRC screening programs (21). Limitations of the Aronchick Scale include the lack of evaluation in different colon segments. If the bowel preparation in every segment was known, an evaluation of PCCRC tumor location could have been possible.

We conclude that in colorectal screening participants with excellent or good bowel preparation, the probability of detecting adenomas and having a complete examination is highest. Bowel preparation below a good level is associated with higher PCCRC mortality. Striving for optimal bowel cleansing in screening settings might therefore beneficial. Future studies will demonstrate whether other bowel preparation scales have a similar association with long-term PCCRC outcomes and whether a more refined stratification of bowel preparation is necessary.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Guarantor of the article: Monika Ferlitsch, MD.

Specific author contributions: J.Z.S.: conceptualization, formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation. E.W.: writing—review and editing, data curation, methodology. L.M.R.: project administration, resources. A.K.: formal analysis. E.K.: project administration. D.P.: project administration, resources. A.D. and D.P.: project administration, resources. B.M.: project administration, resources. M.T.: writing—review and editing. M.F.: conceptualization, funding acquisition, project administration, resources, writing—review and editing. All authors approved of the final version of the manuscript.

Financial support: The Main Association of Statutory Insurance Institutions, The Austrian Society for Gastroenterology and Hepatology and the Austrian Cancer Aid are supporting the Austrian quality certificate for screening colonoscopy (Qualitätszertifikat Darmkrebsvorsorge).

Potential competing interests: M.T. had advised for Abbvie, Albireo, BiomX, Boehringer Ingelheim, Falk, Gilead, Genfit, Hightide, Intercept, Jannsen, MSD, Novartis, Phenex, Pliant, Regulus, Siemens, Shire, has received grants/research support from Albireo, Alnylam, Cymabay, Falk Pharma, Gilead, Intercept, MSD, Takeda, UltraGenyx, had received speakersfees form BMS, Falk Foundation, Gilead, Intercept, Madrigal, MSD, Roche, has received travel grants from AbbVie, Falk Foundation, Gilead, Intercept, Janssen, Roche, the Medical Universities of Graz and Vienna have filed patents on medical use of norUDCA and is listed as co-inventor. All other authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Study Highlights.

WHAT IS KNOWN

✓ Several quality parameters have been proposed for screening colonoscopy, including bowel preparation quality.

✓ Current guidelines consider adequate bowel preparation as either “excellent”, “good”, or “fair” on the Aronchick scale.

✓ Bowel preparation rating is a subjective measure depending on the endoscopist's opinion and experience.

✓ Thus far, there is a lack of long-term studies investigating postcolonoscopy colorectal cancer (PCCRC) mortality after screening colonoscopy and its association with quality of bowel cleansing.

WHAT IS NEW HERE

✓ Variability in bowel preparation ranking was highest among colonoscopies between excellent or other scores but lower for the scores good, fair, poor, or inadequate.

✓ We found that adenoma detection was less likely in screening participants with fair or worse bowel preparation.

✓ PCCRC mortality was significantly higher in individuals with fair, poor, or inadequate bowel preparation.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL accompanies this paper at http://links.lww.com/AJG/D291, http://links.lww.com/AJG/D292, http://links.lww.com/AJG/D293, http://links.lww.com/AJG/D294, and http://links.lww.com/AJG/D295

Contributor Information

Jasmin Zessner-Spitzenberg, Email: Jasmin.zessner-spitzenberg@meduniwien.ac.at.

Elisabeth Waldmann, Email: Elisabeth.waldmann@meduniwien.ac.at.

Lisa-Maria Rockenbauer, Email: Lisa-maria.rockenbauer@meduniwien.ac.at.

Andreas Klinger, Email: Andreas.klinger@meduniwien.ac.at.

Entcho Klenske, Email: Entcho.klenske@meduniwien.ac.at.

Daniela Penz, Email: da.penz@hotmail.com.

Alexandra Demschik, Email: alexandra.demschik@meduniwien.ac.at.

Barbara Majcher, Email: barbara.majcher@hotmail.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lin JS, Perdue LA, Henrikson NB, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: Updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2021;325(19):1978–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.European Commission, Directorate-General for Health, Consumers, Executive Agency for Health, Consumers, World Health Organization. European guidelines for quality assurance in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis. Publications Office, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rutter MD, Beintaris I, Valori R, et al. World Endoscopy Organization consensus statements on post-colonoscopy and post-imaging colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 2018;155(3):909–25.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waldmann E, Penz D, Šinkovec H, et al. Interval cancer after colonoscopy in the Austrian National Screening Programme: Influence of physician and patient factors. Gut 2021;70(7):1309–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valori R, Rey JF, Atkin WS, et al. European guidelines for quality assurance in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis. First Edition: Quality assurance in endoscopy in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis. Endoscopy 2012;44(Suppl 3):SE88–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calderwood AH, Jacobson BC. Comprehensive validation of the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale. Gastrointest Endosc 2010;72(4):686–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rostom A, Jolicoeur E. Validation of a new scale for the assessment of bowel preparation quality. Gastrointest Endosc 2004;59(4):482–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aronchick CA, Lipshutz WH, Wright SH, et al. A novel tableted purgative for colonoscopic preparation: Efficacy and safety comparisons with Colyte and Fleet Phospho-Soda. Gastrointest Endosc 2000;52(3):346–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaminski MF, Thomas-Gibson S, Bugajski M, et al. Performance measures for lower gastrointestinal endoscopy: A European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Quality Improvement Initiative. Endoscopy 2017;49(4):378–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rex DK, Schoenfeld PS, Cohen J, et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2015;81(1):31–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark BT, Protiva P, Nagar A, et al. Quantification of adequate bowel preparation for screening or surveillance colonoscopy in men. Gastroenterology 2016;150(2):396–405; quiz e14–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clark BT, Rustagi T, Laine L. What level of bowel prep quality requires early repeat colonoscopy: Systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of preparation quality on adenoma detection rate. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109(11):1714–23; quiz 1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas-Gibson S, Rogers P, Cooper S, et al. Judgement of the quality of bowel preparation at screening flexible sigmoidoscopy is associated with variability in adenoma detection rates. Endoscopy 2006;38(5):456–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waldmann E, Gessl I, Sallinger D, et al. Trends in quality of screening colonoscopy in Austria. Endoscopy 2016;48(12):1102–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferlitsch M, Reinhart K, Pramhas S, et al. Sex-specific prevalence of adenomas, advanced adenomas, and colorectal cancer in individuals undergoing screening colonoscopy. JAMA 2011;306(12):1352–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zessner-Spitzenberg J, Jiricka L, Waldmann E, et al. Polyp characteristics at screening colonoscopy and post-colonoscopy colorectal cancer mortality: A retrospective cohort study. Gastrointest Endosc 2023;97(6):1109–18.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zessner-Spitzenberg J, Waldmann E, Jiricka L, et al. Comparison of adenoma detection rate and proximal serrated polyp detection rate and their effect on post-colonoscopy colorectal cancer mortality in screening patients. Endoscopy 2023;55(5):434–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Vet HCW, Terwee CB, Knol DL, et al. When to use agreement versus reliability measures. J Clin Epidemiol 2006;59(10):1033–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hox J, Moerbeek M, van de Schoot R. Multilevel Analysis: Techniques and Applications. 2nd edn. Routledge: New York, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Radaelli F, Paggi S, Hassan C, et al. Split-dose preparation for colonoscopy increases adenoma detection rate: A randomised controlled trial in an organised screening programme. Gut 2017;66(2):270–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Saltzman JR, Cash BD, et al. Bowel preparation before colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2015;81(4):781–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hassan C, East J, Radaelli F, et al. Bowel preparation for colonoscopy: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline: Update 2019. Endoscopy 2019;51(8):775–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson JC, Butterly LF, Robinson CM, et al. Impact of fair bowel preparation quality on adenoma and serrated polyp detection: Data from the New Hampshire colonoscopy registry by using a standardized preparation-quality rating. Gastrointest Endosc 2014;80(3):463–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Froehlich F, Wietlisbach V, Gonvers JJ, et al. Impact of colonic cleansing on quality and diagnostic yield of colonoscopy: The European Panel of Appropriateness of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy European multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc 2005;61(3):378–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sherer EA, Imler TD, Imperiale TF. The effect of colonoscopy preparation quality on adenoma detection rates. Gastrointest Endosc 2012;75(3):545–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corley DA, Jensen CD, Marks AR, et al. Adenoma detection rate and risk of colorectal cancer and death. N Engl J Med 2014;370(14):1298–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaminski MF, Regula J, Kraszewska E, et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy and the risk of interval cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;362(19):1795–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schottinger JE, Jensen CD, Ghai NR, et al. Association of physician adenoma detection rates with postcolonoscopy colorectal cancer. JAMA 2022;327(21):2114–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Atkin W, Rogers P, Cardwell C, et al. Wide variation in adenoma detection rates at screening flexible sigmoidoscopy. Gastroenterology 2004;126(5):1247–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lieberman DA, Williams JL, Holub JL, et al. Colonoscopy utilization and outcomes 2000 to 2011. Gastrointest Endosc 2014;80(1):133–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gu P, Lew D, Oh SJ, et al. Comparing the real-world effectiveness of competing colonoscopy preparations: Results of a prospective trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114(2):305–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Waldmann E, Penz D, Majcher B, et al. Impact of high-volume, intermediate-volume and low-volume bowel preparation on colonoscopy quality and patient satisfaction: An observational study. United European Gastroenterol J 2019;7(1):114–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]