Abstract

Citalopram (CTLP) is one of the most common antidepressants prescribed worldwide. It has a narrow therapeutic window and can cause severe toxicity and mortality if the dosage exceeds the safe level. Reports indicated that at-home monitoring of citalopram dosage considerably benefits the patients, yet there are no devices capable of such measurement of citalopram in biofluids. This work presents an affordable citalopram test for at-home and point-of-care monitoring of citalopram levels in urine, ensuring a safe and effective drug compliance. Our platform consists of a citalopram-selective yarn-based electrode (CTLP-SYE) that uses polymeric sensing membranes to provide valuable information about drug concentration in urine. CTLP-SYE is noninvasive and has a response time of fewer than 10 s. The fabricated electrode showed near-Nernstian behavior with a 52.3 mV/decade slope in citalopram hydrobromide solutions ranging from 0.5 μM to 1.0 mM, with a detection limit of 0.2 μM. Results also indicated that neither interfering ions nor pH affects electrode performance. We showed that CTLP-SYE could accurately and reproducibly measure citalopram in human urine (RSD 2.0 to 3.2%, error <12%) at clinically relevant concentrations. This work paves the way for the personalized treatment of depression and accessible companion diagnostics to improve treatment efficacy and safety.

Keywords: potentiometry, point-of-care sensing, mental health, companion diagnostics, solid-contact electrode, SSRI, yarn-based sensor

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Millions of people around the world suffer from mental health disorders- a statistic that is under-reported due to the associated social stigma.1 The incidence of mental health problems has increased as social stress rises due to urbanization, violence, and discrimination.2–4 Despite the growing number of people diagnosed with mental health disorders, there has been little technological innovation for effectively diagnosing and treating these patients. Two contributing factors are the social stigma associated with mental health conditions and the unawareness of technological needs via the scientific community. Additionally, uncertain treatment outcomes and financial concerns make patients less likely to seek medical attention or utilize expensive assistive technologies.5 Consequently, cost-effective and affordable interventions are crucial to improving the treatment of mental health disorders.

Depression is a leading mental health disorder; more than 17% of the world population has experienced at least one period of major depression during their lifetime. It is especially prevalent in patients suffering from a cardiovascular disorder.6 In the United States alone, depression costs the economy over 43 billion dollars annually.7 Studies have also shown that depressed patients are more susceptible to premature death.8,9 The current standard for treating depression is prescription antidepressants.10 While these have successfully produced behavioral changes in rodent models, the extent to which animals can model human mental disorders is unclear, and thus, the11safety of antidepressants is constantly being evaluated.11

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) could inhibit the neuronal uptake pump for serotonin without interfering with other neuroreceptors and have been discovered as a significant therapeutic advance in psychopharmacology.12 Previous studies have shown that, compared to older antidepressants, SSRIs have less effect on patient heart rate, fewer drug interactions, and reduce the risk of acute cardiovascular problems; these factors have made SSRIs the most commonly prescribed class of antidepressants.6,13,14

Citalopram (Figure 1A) is a common SSRI that has been demonstrated to effectively treat various mental disorders such as pervasive developmental disorder, depression, or panic disorder.15–17 As a result, it is now the most-prescribed antidepressant in North America and Europe.18–20 However, in the past two decades, some studies have shown that citalopram has the greatest likelihood of inducing cardiac and neurological toxicity among SSRIs, and frequent reports have shown this toxicity in overdosed patients.19–22 In addition, more recent studies have pointed out that overdosed patients may develop serotonin syndrome, a drug-induced buildup of high levels of serotonin in the body.23,24 Citalopram overdosing has also resulted in the loss of life.20,25,26

Figure 1.

Schematics and images of our platform. (A) Citalopram hydrobromide (CTLP) is one of the most common antidepressants for depression treatment and its chemical structure. (B) Schematic of CTLP-SYE for citalopram therapeutic monitoring. The sensor can be connected to a portable smartphone-connected electrical detector and dipped in urine to measure citalopram. While the figure shows a fully thread-based system that includes a compact reference electrode, this work only develops and discusses the citalopram sensing electrode. (C) Toxic, therapeutic, and subtherapeutic levels of citalopram in urine. (D) Electrical potential (electromotive force, emf) of CTLP-SYE is an indicator of citalopram concentration in urine.

Studies have emphasized the importance of therapeutic drug monitoring in citalopram treatments for personalizing each patient’s drug dosage, particularly for pregnant women wanting to minimize citalopram toxicity toward the fetus.27–29 Therefore, an inexpensive point-of-care (PoC) device for citalopram detection would greatly benefit society.

Currently, citalopram is measured via blood draws and high-performance liquid chromatography.27,30 This test is done in a laboratory setting and requires trained lab technicians to operate intricate equipment and perform complex reagent handling.30,31 As a result, the test is expensive and results in reported turnaround times that range from two business days up to 3 weeks.32 This test is infeasible for patients who need to immediately know their current drug concentration. In the past decade, a few studies have developed sensors for citalopram detection in blood, but certain aspects of their work precluded them from being used as at-home PoC devices. For example, colorimetric sensors were recently developed, but quantifying citalopram concentration by color change proved inaccurate at times.33 Voltammetric and potentiometric sensors were also developed, yet their bulky and expensive setup (such as the use of glassy carbon electrodes, platinum wires, and conventional potentiometric sensors with inner filling solution) makes them unrealistic for the at-home setting.34,35

In addition, blood tests are generally invasive and carry a higher infection risk, and the use of painful needles could intimidate some patients. Therefore, a noninvasive method of monitoring citalopram concentration is desired. Studies show a correlation between the citalopram concentrations in blood and urine. Figure 1C shows the corresponding toxic concentration in urine (≥4.8 μM) and the therapeutic concentration (1.2–4.8 μM).20,36,37 Therefore, this work developed a urine-based test to enable noninvasive, at-home measurement of citalopram for the safe and personalized treatment of depression. We take advantage of citalopram ionization in biofluids to develop a potentiometric sensor for citalopram. Our platform is based on cotton yarn, mesoporous carbon black, and a citalopram sensing membrane that is selected for citalopram based on the drug hydrophobicity. Our simple fabrication process ensures the sensors’ low cost. We validated CTLP-SYE for high-accuracy measurements of citalopram in human urine with a short response time of less than 1 min (Figure 3B and D). CTLP-SYE is a point-of-care or at-home sensor developed for citalopram; we hope it can pave the way for the personalized and safe treatment of depression.

Figure 3.

Characterization of the sensor response to citalopram. Panels (A) and (B) show the emf of a conventional liquid-contact potentiometric citalopram sensor in citalopram solutions (successive dilutions in deionized water). Panels (C) and (D) show the emf of CTLP-SYE in citalopram solutions (successive dilutions in deionized water). All measurements were conducted with 5 replicate electrodes.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials.

Poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC, high molecular weight), 2-nitrophenyl octyl ether (o-NPOE), sodium tetrakis(4-chlorophenyl)-borate (NaTClPB), tetrahydrofuran (THF, inhibitor-free), sodium sulfate, sodium citrate, creatinine hydrochloride, potassium chloride, sodium chloride, calcium chloride, ammonium chloride, potassium oxalate, magnesium sulfate, sodium phosphate monobasic, sodium phosphate dibasic, hydrochloric acid, potassium hydroxide were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Carbon black VCX-72 powder was donated by Cabot Inc. Citalopram hydrobromide was purchased from VWR. Uric acid powder (99% purity) was purchased from Alfa Aeser. Mercerized cotton yarn (a product of Aunt Lydia’s, 400 μm diameter) was purchased from Amazon. Pooled human urine was purchased from Innovative Research.

Electrochemical Measurements.

A double-junction Ag/AgCl/3.0 M KCl/1.0 M LiOAc reference electrode was used in the potentiometric measurements (Model DX200, Mettler Toledo, Greifensee, Switzerland). Potentiometric measurements were carried out with a high impedance input 16-channel EMF monitor (Lawson Laboratories, Inc., Pennsylvania) with an EMFSuite 2.0 interface. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) was conducted using a CHI 760E potentiostat (CH Instruments, Texas). EIS was measured against an open-circuit potential from 0.1 Hz to 100 kHz in a 1X Phosphate buffer solution against a commercial reference electrode (CHI 111, CH Instrument, Inc.), which yielded approximately 26.0 kΩ membrane resistivity (Figure 2C) by fitting data to an equivalent Randles circuit. Zview software (Scribner Associates Inc., North Carolina) was used to plot the fitted Nyquist plot. All EMF values were measured at room temperature (25 ± 3 °C) in stirred solutions. Reading was performed after the electrodes were immersed in test solutions after 5–10 s.

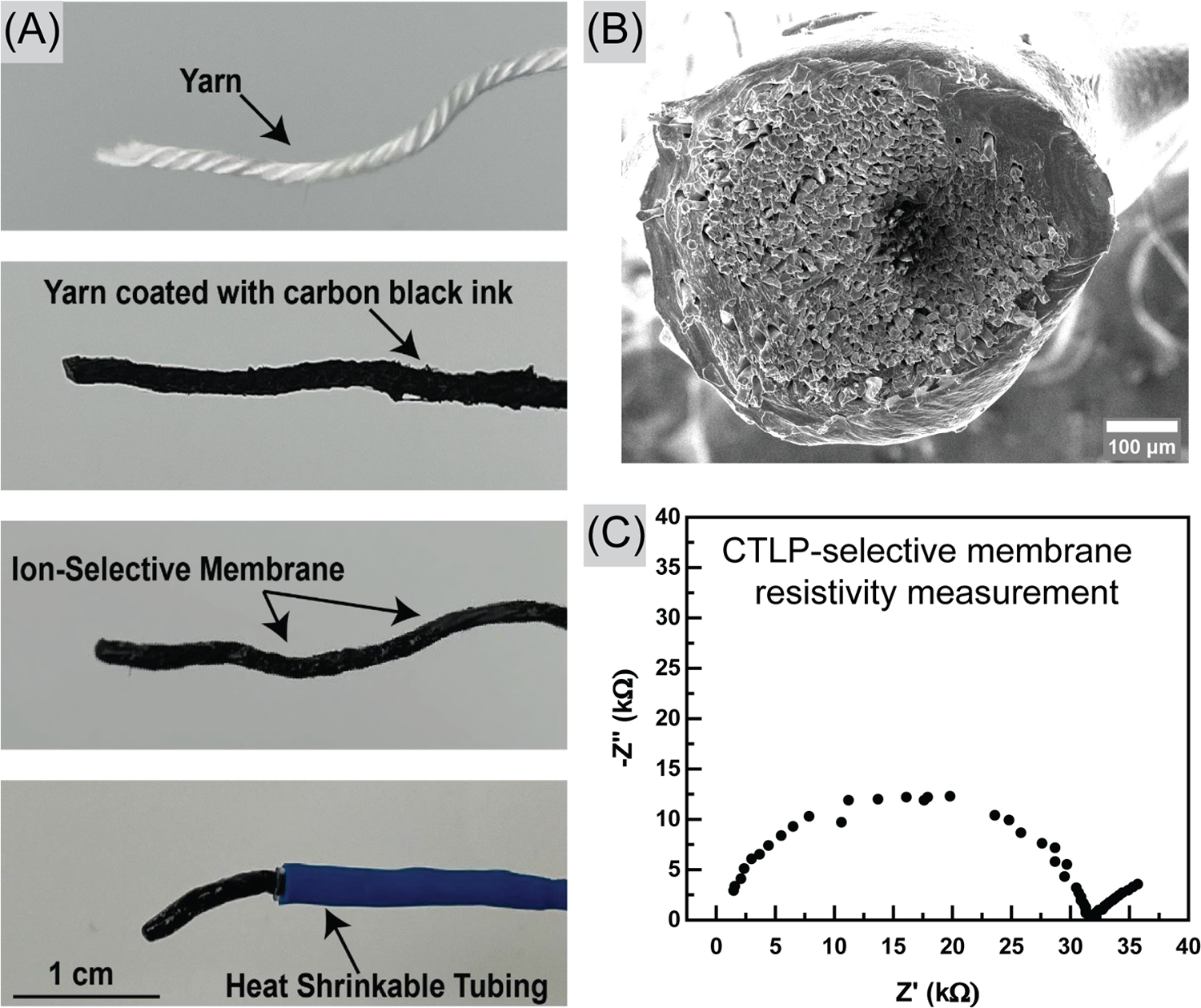

Figure 2.

Fabrication and Characterization of CTLP-SYE. (A) Cotton yarn is coated with carbon black ink, dried, and then dip-coated with the sensing membrane. The exposed carbon black is sealed with heat-shrinkable tubing. (B) SEM shows the cross-section of CTLP-SYE, cotton yarn that is coated with ink and sensing membrane. (C) Nyquist plot of CTLP-SYE measured in PBS solution.

Electrode Fabrication.

Liquid-Contact Potentiometric Sensor.

The ion-selective membrane (ISM) was prepared by dissolving 330 mg of PVC, 660 mg of o-NPOE, and 10 mg of NaTClPB in 3 mL of THF. The mixture was stirred overnight until a homogeneous CLTP-selective precursor was obtained. Next, the liquid membrane was poured into a 60 mm × 15 mm glass Petri dish. The glass dish containing the CTLP-selective membrane was covered and kept under controlled air flow for 24 h. After 24 h period, the membrane solidified. We created a disk-like membrane using a 1/4 in. diameter punch and attached the solid CTLP-selective membrane to a 5.0 cm long Tygon tube via THF. We secured the attachment of the membrane to the Tygon tube by applying constant pressure for 10 s before air-drying electrodes for 10 min. The membrane was conditioned overnight by placing the electrode in a 1.0 mM citalopram hydrobromide solution, where a color change in the membrane was observed. Afterward, the inner filling solution, 1.0 mM KCl, and 1.0 mM citalopram hydrobromide were used to fill the Tygon tube. Finally, a Ag/AgCl wire was placed inside the inner filling solution, and the Tygon tube was sealed using parafilm.

Thread-Based Solid-Contact Sensor.

In Figure 2A, we illustrate the fabrication process. First, we created a polymeric conductive ink mixture by dissolving 250.0 mg of PVC with 500.0 mg of o-NPOE under continuous stirring in the presence of 2.5 mL of THF solvent for 3 h. Next, 250.0 mg of carbon black VCX-72 powder was added to the polymeric ink matrix. The carbon-black-based ink homogeneity was achieved by thoroughly pounding the conductive ink mixture with a mortar and pestle. The 5.0 cm long 100% mercerized cotton yarns were dipped three times in the carbon-black-based ink for ten-second intervals (other types of fibers can be used for fabrication, but the mercerized cotton provided the highest reproducibility). The conductive ink-coated yarns were air-dried for an hour. The CTLP-selective membrane was synthesized by blending 330.0 mg of high molecular weight PVC, 660.0 mg of o-NPOE, 10.0 mg of NaTClPB, and 5.0 mg of citalopram hydrobromide using 3.0 mL of THF solvent. The CTLP-selective membrane was stirred continuously overnight to obtain a homogeneous CTLP-selective precursor. We coated one end of the conductive yarn (Approximately 1.0 cm long) with a CTLP-selective membrane for 10 s and allowed it to dry for 10 s afterward. This dipping process was repeated three times to ensure the CTLP-selective membrane fully coated the conductive yarn electrodes. We then allowed the THF solvent to evaporate overnight at room temperature and ensured bonding between the CTLP-selective membrane and conductive yarn. Finally, a 3.0 cm commercial heat-shrinking tube was placed on the electrodes, exposing 1.0 cm of the membrane-coated and 1.0 cm of the conductive yarn electrode on either end. The heat was applied to the shrink tube via a heat gun for approximately ten seconds to enable proper shrinking.

Artificial Urine (aUrine) Studies.

We synthesized aUrine according to a previous study.38 Briefly, we recapitulate the ionic components of the urine by diluting sodium sulfate 412.0 mM, uric acid 1.5 mM, sodium citrate 2.4 mM, creatinine 7.8 mM, potassium chloride 31.0 mM, sodium chloride 30.1 mM, calcium chloride 1.7 mM, ammonium chloride 23.7 mM, potassium oxalate 0.2 mM, magnesium sulfate 4.4 mM, sodium phosphate monobasic 18.7 mM, and sodium phosphate dibasic 4.7 mM into 100.0 mL of deionized water. Next, the aUrine solution was spiked with a 1.0 mM concentration of the citalopram hydrobromide.

Pooled Human Urine Studies.

Pooled human urine (freshly collected from multiple donors) was purchased from VWR (a product of Innovative Research Inc.). We spiked the pooled human urine sample with 100 μM citalopram hydrobromide. Three different concentrations of spiked solution were chosen (50.0, 12.5, and 3.1 μM), each corresponding to the fatal, acute toxicity, and therapeutic ranges, enabling us to evaluate the sensor’s accuracy in clinical applications (Figure 1C).

pH Studies.

The influence of pH on the potentiometric responses was evaluated in 1.0 mM citalopram hydrobromide spiked in artificial urine with adjusted pH by utilizing 1.0 M HCl and 1.0 M KOH. The potential of hydrogen reading was taken after stabilization using the Thermo Fisher Fisher Orion Star A211 pH meter (Waltham, Massachusetts) to determine the resultant pH of the artificial urine.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Design and Fabrication of CTLP-SYE.

The key design requirements for the CTLP-SYE were: (i) it must be convenient and user-friendly, (ii) it must be a low-cost device, and (iii) it must detect citalopram selectively and accurately. The CTLP-SYE is a low-cost citalopram test that simply requires users to immerse the sensor into a urine sample and read out the data (Figure 1B). Smartphone-compatible electrical detectors can be used for point-of-care data readout (detector development falls outside the scope of this work). The sensor detects citalopram in the urine matrix to be a noninvasive measurement. This is the first solid-contact potentiometric sensor for citalopram and the first point-of-care citalopram sensor in general. Potentiometric sensors have shown promise for the rapid, selective, and accurate detection of drugs, and their electrochemical nature makes data collection and readout on computers and smart devices trivial.39 However, conventional potentiometric electrodes are bulky, expensive, and fragile.39 Recent advances have enabled the construction of sensors from durable, affordable materials.40–43 Additionally, miniature, affordable, and open-source potentiometers such as the Universal Wireless Electrochemical Detector (UWED) and CheapStat enabled mobile potentiometric measurements.44,45

Although citalopram is formulated as a bromide salt when administered as an oral medication (Figure 1A), more than 98% of the drug is present in the cationic form at pH values of less than 8 (based on its high pKa of 9.57).46 Citalopram is also highly hydrophobic with a partition coefficient of 3.5.46 Therefore, citalopram is an ideal candidate for potentiometric detection, where there is inherent selectivity for hydrophobic ionic compounds. The CTLP-SYE takes advantage of these properties, using a hydrophobic membrane to separate the hydrophobic citalopram cation from its hydrophilic bromine counteranion at the membrane-solution interface. The separation at this phase boundary generates a measurable potential that is dependent on the activity of citalopram. This potential is referred to as the electromotive force , which is related to ion activity by the Nernst equation

| (1) |

where is the universal gas constant, is the temperature in kelvin, and are the charge of the ion of interest (citalopram) and the interfering ion is the activity of the interfering ion , and is the Faraday constant. represents the sum of all of the other contributing electrical potentials and energies. The selectivity of the sensor is represented in the selectivity coefficient . This value compares the sensor’s response to the primary ion compared to the interfering ion. Traditionally in potentiometric sensors, the selectivity is tuned by adding an ionophore (chemical compounds with a high affinity for particular ions) to the sensing membrane. However, in the CTLP-SYE, the primary driver of selectivity is the ion’s hydrophobicity. Here, we show that an ionophore-free ion-exchanger membrane can selectively detect citalopram in urine.

Figure 2 shows the fabrication of CTLP-SYE. The sensor is fabricated from cotton yarn, an ideal substrate for low-cost sensors due to its ubiquity, high tensile strength, flexibility, high surface area, and ease of disposal by incineration. We coat the yarn with carbon black ink to make it conductive. We chose carbon black as an ion-to-electron transducer because it is affordable and highly porous (resulting in high capacitance and high signal stability for the sensor). We have previously demonstrated the use of a carbon black-impregnated yarn-based potentiometric sensor for different ions.40,47,48 The conductive yarn was then partially dipped into the THF-solubilized precursor of the citalopram sensing membrane. We used a heat-shrinkable tube to seal the exposed ion-to-electron transducer and prevent shorting, and while traditional ion-selective electrodes require extensive conditioning before use, CTLP-SYEs are immediately ready for use. We accomplished this by spiking the THF-solubilized sensing membrane precursor with citalopram bromide to form the citalopram-ionic site complex without a conditioning process. All measurements were performed with dry-stored electrodes without any conditioning to mimic use in real-life settings.

During and after the fabrication process, we utilized various methods to characterize the sensors. Resistance of five different carbon black ink-coated yarns was first taken, and 386 ± 17 Ω cm−1 was recorded before coating with ISM. Figure 2B shows SEM images of the ink and membrane-coated electrode. The electrode was characterized by using EIS, as shown in Figure 2C, and the charge transfer resistance was estimated to be roughly 26 kΩ. To validate this, we also used the shunt method to measure ISM resistance, as shown in our previous study.48 This method estimated the charge transfer resistance at roughly 40 kΩ, the same order of magnitude as that calculated by EIS (26 kΩ). Both methods record large resistance of the membrane, especially compared to the resistance of carbon black ink-coated yarn (386 Ω cm−1), indicating successful coating of the membrane onto the carbon black ink-coated yarn. The discrepancy between the two results could be due to the different electrodes tested.

Characterization of Sensor Response.

Preliminary experiments were first carried out on conventional liquid-contact electrodes to validate the feasibility of an ion-exchanger electrode to measure citalopram. For this purpose, a conventional potentiometric sensor with an inner filling solution was fabricated and tested. Figure 3A,B shows the calibration curve in citalopram hydrobromide solution, where a linear range of 1 × 10−3 to 1.6 × 10−5 M, with a near-Nerstian slope of 51.5 mV/decade was achieved. The limit of detection (LOD) of the sensor was established at the intersection point of the extrapolated linear working range and the nonlinear range of the calibration plot as recommended by the IUPAC.49 We calculated a detection limit of 2.1 μM, indicating the membrane’s good sensitivity toward detecting the ionized form of the drug in the clinically relevant concentration of citalopram in urine.

While the conventional liquid-contact electrode showed promise for the selective and sensitive detection of citalopram, this system is difficult to use in the point-of-care setting. Conventional liquid-contact electrodes require maintenance of the inner filing solution due to evaporation and are difficult to miniaturize. Solid-contact potentiometric systems are advantageous to liquid-contact electrodes as they have a long shelf life and can be stored without concerns for the evaporation of inner filling solution. Figures 3C, 3D show the calibration curve of the yarn-based electrodes in citalopram hydrobromide solution. The sensors showed a LOD of 0.2 μM with a near-Nerstian slope of 52.3 mV/decade in the linear range of 4.5 × 10−7 to 1 × 10−3 M. The results indicate excellent performance with submicromolar detection limit, with near-Nernstian behavior of the linear range fully covering both the adverse toxicity range and therapeutic range found in human urine.20,36,37 In addition, 9.2 mV of standard deviation calculated from the E° value were recorded. Compared to the standard deviation calculated from a conventional potentiometric sensor (7.9 mV), this indicates similar reproducibility of the yarn-based electrodes compared to the conventional potentiometric sensor with an inner filling solution. The CTLP-SYE showed a better LOD than the traditional liquid-contact electrodes likely due to the elimination of ion fluxes from the inner filling solution to the sample solution.

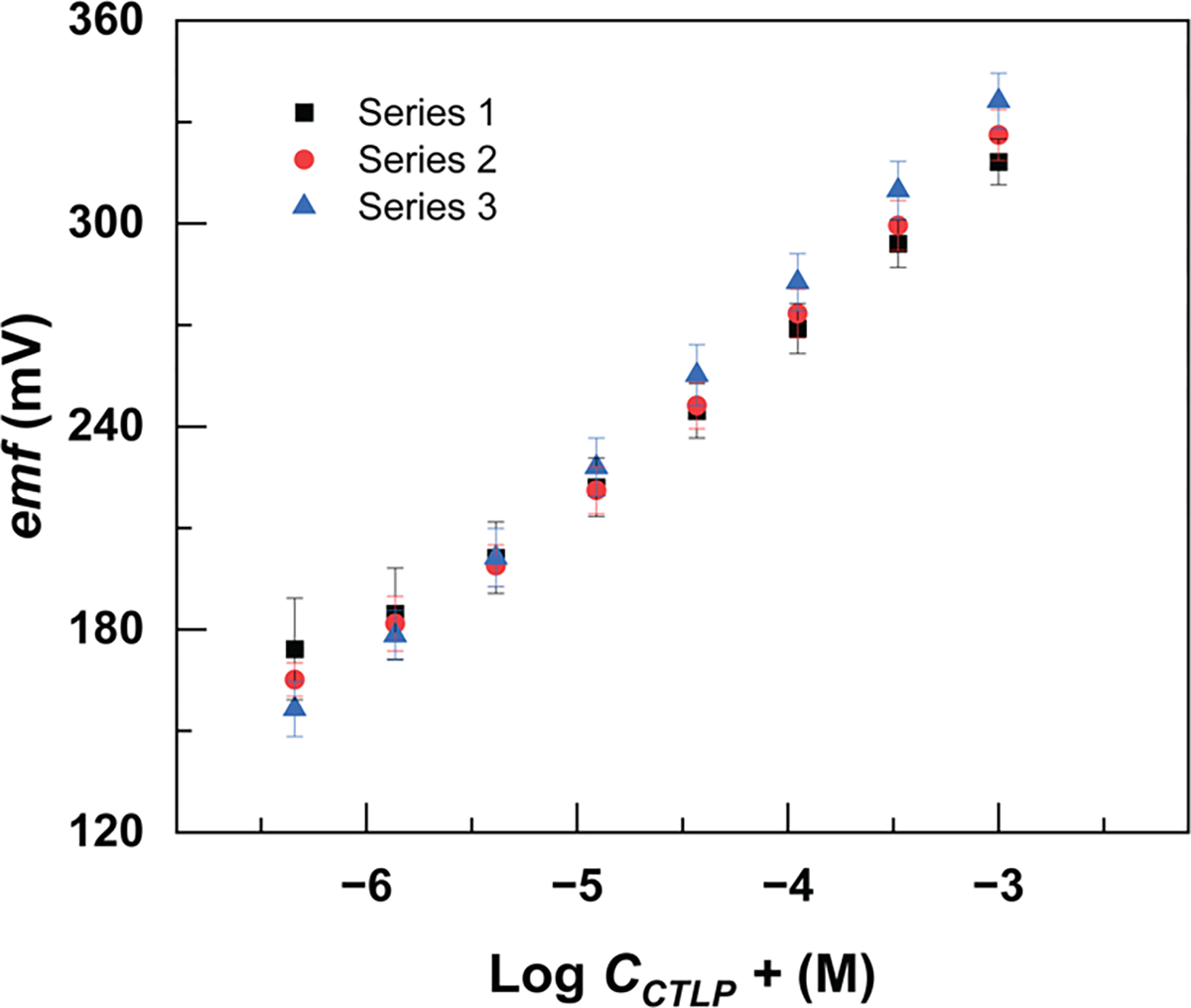

Last, we explored batch-to-batch reproducibility of the yarn-based electrodes. Figure 4 shows the calibration curve of three different batches of the yarn-based electrodes in a citalopram hydrobromide solution. Each batch of electrodes was made 1 week after the previous batch. The standard deviation calculated from the E° value from all 15 electrodes was 16.2 mV. The linear slope and E° value of each individual batch are listed in Table 1.

Figure 4.

Batch-to-batch reproducibility of citalopram-selective electrodes (each series includes five electrodes).

Table 1.

Batch-to-Batch Reproducibility of the Sensorsa

| batch | slope (mV/decade) | E° (mV) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 51.7 | 473.4 ± 9.8 |

| 2 | 55.3 | 504.6 ± 10.9 |

| 3 | 56.1 | 492.0 ± 9.6 |

Reported values are mean and standard deviation of five replicate electrodes calibrated in citalopram chloride solution.

Characterization of Sensor Selectivity.

We measured the sensor selectivity using the fixed interference method (FIM) as established previously.49 We specifically measured the selectivity over ions that are predominantly present in urine, including sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium, and ammonium ions. In FIM, the electrode function is measured in a solution with a fixed concentration of an interfering ion while the concentration of the analyte is changed. Figure 5A shows the results, and Table 2 shows the measured values of the selectivity coefficient. Based on the results, we can conclude that the sensors were minimally affected by the interfering ions and the sensor exhibits sufficient selectivity for direct measurement in urine.

Figure 5.

Selectivity of CTLP-SYE, measured with the established fixed interference method. (A) Emf of CTLP-SYE at different citalopram concentrations was measured in the background of common interfering ions. (B) Emf of CTLP-SYE in spiked artificial urine solutions (successive dilutions in artificial urine). All measurements were conducted with 5 replicate electrodes

Table 2.

Selectivity Coefficient of CTLP-SYE against Interfering Ions

| interfering ion | selectivity coefficient |

|---|---|

| Na+ | −4.45 |

| K+ | −3.19 |

| Ca2+ | −4.39 |

| Mg2+ | −3.97 |

| NH4+ | −3.23 |

The performance of CTLP-SYE was then assessed in spiked artificial urine solution to examine its performance in complex matrices. Figure 5B illustrates the calibration curve. The sensor LOD in artificial urine was 0.6 μM with a near-Nernstian slope of 50.1 mV/decade in the linear range of 1.3 × 10−6 to 1.0 × 10−3 M. Compared to the calibration curve obtained from citalopram hydrobromide solution, we see a small increase in LOD, likely due to the background signal from interfering ions in urine. The linear range, however, still covers the toxic and therapeutic range.

Effect of pH.

Previous clinical studies demonstrated that the urine pH level is between 5 to 7 in patients who were taking citalopram as their primary depression treatment.36 In addition, other studies have shown that different pH levels could affect the protonation state of the drug, which in turn will affect the readout of potentiometric sensors.35,50 As a result, it is necessary to examine the ISEs’ performance in the clinically relevant pH ranges. The readings were conducted by keeping the concentration of citalopram in an artificial urine solution at 1 mM while adjusting the pH level. Figure 6 depicts the emf readings, demonstrating that the sensor is minimally affected by pH changes in the urine sample.

Figure 6.

Impact of pH on the performance of CTLP-SYE. The emf values of CTLP-SYE are recorded at a 1 mM citalopram solution at different pH values. Measured values are from five replicate electrodes.

Application of CTLP-SYE for Measurement of Citalopram in Urine.

Last, we studied the performance of CTLP-SYE in spiked human urine samples. A four-point calibration curve was first constructed between the range of 10−6 and 10−4 M, as shown in Figure 7. This range reflects the clinically relevant concentration range of citalopram in urine. An average linear slope of 45.2 mV/decade (n = 5) was observed in this range, slightly lower than the value obtained from artificial urine calibration (50.1 mV/decade). However, when a similar range of concentration from the artificial urine calibration data was plotted (1.1 × 10−6 to 1.4 × 10−4 M), the average linear slope of 45.8 mV/decade was recorded, indicating consistent performance in complex matrices. Therefore, the main reason the slope was not close to the theoretical value (59.2 mV/decade) is likely due to the interference from background ions present in urine. After the calibration curve was constructed, the emf response of randomly chosen spiked urine samples was measured, and the concentrations were calculated by using the calibration curve established in urine. Concentrations of 50, 12.5, and 3.125 μM citalopram spiked in urine were chosen as they represent fatal, adverse toxicity, and therapeutic range found in human urine samples.20,36,37 Figure 7 and Table 3 show the recovery studies. Recoveries were higher than 88%, and RSD values were below 4% in all cases. The results indicate the suitability of using the proposed all-solid-state yarn-based sensor for determining the citalopram concentration in urine. We showed that CTLP-SYE could monitor the therapeutic concentration of citalopram in human urine with good accuracy and reproducibility.

Figure 7.

Recovery studies with CTLP-SYE. EMF responses of the calibration points and spiked urine samples from the recovery study. Measured values are from five replicate electrodes.

Table 3.

Summary of Recovery Test in Urine Samplesa

| spiked concentration (μM) | measured concentration (μM) | RSD (%) | recovery (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3.1 | 3.03 ± 0.01 | 0.20 | 96.95 ± 2.12 |

| 12.5 | 11.0 ± 0.2 | 1.82 | 88.28 ± 1.95 |

| 50.0 | 51.1 ± 1.7 | 3.32 | 102.16 ± 3.30 |

Measured values are mean ± standard deviation of EMF reading from five replicate electrodes.

CONCLUSIONS

In this work, we present CTLP-SYE, the first all-solid-state yarn-based potentiometric sensor that is capable of measuring citalopram in urine samples with a linear range that fully covers fatal, adverse toxicity, and therapeutic ranges. We showed that CTLP-SYE can accurately determine citalopram in urine with high accuracy (average recovery of 96%) and could serve as a useful tool for point-of-care monitoring of citalopram level in clinical samples. CTLP-SYE is low cost and affordable, as it is fabricated from cotton yarn and inexpensive carbon black. The cost of measurement with CTLP-SYE is significantly reduced compared to that of the current lab-based tests. Additionally, the sensor is also capable of giving a readout after being immersed in the solution for 1 min (Figure 3B and 3D) in contrast to the current lab-based tests that have turnaround times from days up to weeks. Last, the sensor uses urine as its detection biofluid, which makes the testing module non-invasive and reduces the chance of infection that could be caused by blood draw. This sensor can be expanded to other ionizable drugs for therapeutic monitoring.

This work focused on the fabrication and characterization of the sensor itself. Measurements were performed with a bulky, fragile commercial reference electrode. Future work should develop a miniaturized reference electrode in addition to the measuring electrode itself to enable a genuinely low-cost setup for on-site measurements. Other areas of improvement for the sensor are addressing the need for the calibration of each sensor and developing calibration-free solid-contact sensors.

In addition, previous research has pointed out that depression is often accompanied by chronic illnesses such as Alzheimer’s disease or Parkinson’s disease. Therefore, citalopram could be coadministered with drugs such as levodopa or galantamine.51 The calculated log P values for levodopa (−1.7) and galantamine (1.1) show that these drugs are substantially more hydrophilic than citalopram.52 Therefore, it is likely that levodopa and galantamine will not interfere with sensor performance. However, interference from other medications is possible; thus, the medical history of the patient as well as the medications they are taking should be considered before device use.

The ionophore-free sensing membrane used in this work could also be applicable for the detection of other hydrophobic drugs. The inherent selectivity of polymeric potentiometric sensing membrane to hydrophobic molecules is well known as partition coefficient and material distribution between phases are determining factors in sensor selectivity. One limitation of this sensing mechanism is possible interference by other hydrophobic molecules. Therefore, extensive clinical validation should be conducted before the sensors can be used in the field.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was funded by 3M Nontenured Faculty Award to M.M., NIH Director’s New Innovator Award (DP2GM150018), and the Zumberge Team Building Grant from the University of Southern California. F. Amirghasemi thanks the University of Southern California, Viterbi Graduate Fellowship. All authors thank the Core Center of Excellence in Nano Imaging at the University of Southern California and Daniel Goodelman for his suggestions on SEM imaging. R.C. thanks the Viterbi CURVE Research Fellowship and Provost’s Undergrad Fellowship from the University of Southern California.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Ruitong Chen, Alfred E. Mann Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California 90089, United States.

Farbod Amirghasemi, Alfred E. Mann Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California 90089, United States.

Haozheng Ma, Alfred E. Mann Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California 90089, United States.

Victor Ong, Alfred E. Mann Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California 90089, United States.

Ava Tran, Mork Family Department of Chemical Engineering, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California 90089, United States.

Maral P. S. Mousavi, Alfred E. Mann Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California 90089, United States

REFERENCES

- (1).Bharadwaj P; Pai MM; Suziedelyte A Mental health stigma. Econ. Lett. 2017, 159, 57–60. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Sartorius N Stigma and mental health. Lancet 2007, 370, 810–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Valentine SE; Shipherd JC A systematic review of social stress and mental health among transgender and gender non-conforming people in the United States. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 66, 24–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Peen J; Schoevers RA; Beekman AT; Dekker J The current status of urban-rural differences in psychiatric disorders. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2010, 121, 84–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Frank RG; McGuire TG Economics and Mental Health. In Handbook of Health Economics; Elsevier, 2000; Chapter 16, Vol. 1, pp 893–954. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Zhong Z; Wang L; Wen X; Liu Y; Fan Y; Liu Z A meta-analysis of effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on blood pressure in depression treatment: outcomes from placebo and serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor controlled trials. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2017, 13, 2781–2796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Greenberg PE; Stiglin LE; Finkelstein SN; Berndt ER The economic burden of depression in 1990. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1993, 54, 405–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Kerr TA; Schapira K; Roth M The Relationship between Premature Death and Affective Disorders. Br. J. Psychiatry 1969, 115, 1277–1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Harris C; Barraclough B Excess mortality of mental disorder. Br. J. Psychiatry 1998, 173, 11–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Cryan JF; Markou A; Lucki I Assessing antidepressant activity in rodents: recent developments and future needs. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2002, 23, 238–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Wong M-L; Licinio J Research and treatment approaches to depression. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2001, 2, 343–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Vaswani M; Linda FK; Ramesh S Role of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in psychiatric disorders: a comprehensive review. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2003, 27, 85–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Mourilhe P; Stokes PE Risks and Benefits of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors in the Treatment of Depression. Drug Safety 1998, 18, 57–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Maurer-Spurej E; Pittendreigh C; Solomons K The influence of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on human platelet serotonin. Thromb. Haemostasis 2004, 91, 119–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Namerow LB; Thomas P; Bostic JQ; Prince J; Monuteaux MC Use of Citalopram in Pervasive Developmental Disorders. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2003, 24, 104–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Specchio LM; Iudice A; Specchio N; La Neve A; Spinelli A; Galli R; Rocchi R; Ulivelli M; de Tommaso M; Pizzanelli C; Murri L Citalopram as Treatment of Depression in Patients With Epilepsy. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2004, 27, 133–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Wade AG; Lepola U; Koponen HJ; Pedersen V; Pedersen T The effect of Citalopram in panic disorder. Br. J. Psychiatry 1997, 170, 549–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Bugden S; Friesen K The effectiveness and limitations of regulatory warnings for the safe prescribing of citalopram. Drug, Healthcare Patient Saf. 2015, 139, 139–145, DOI: 10.2147/DHPS.S91046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Jonasson B; Saldeen T Citalopram in fatal poisoning cases. Forensic Sci. Int. 2002, 126, 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Luchini D; Morabito G; Centini F Case Report of a Fatal Intoxication by Citalopram. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2005, 26, 352–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Engebretsen KM; Harris CR; Wood JE Cardiotoxicity and late onset seizures with citalopram overdose. J. Emerg. Med. 2003, 25, 163–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Tarabar AF; Hoffman RS; Nelson LS Citalopram overdose: Late presentation of torsades de pointes (TdP) with cardiac arrest. J. Med. Toxicol. 2008, 4, 101–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Grenha J; Garrido A; Brito H; Oliveira MJ; Santos F Serotonin Syndrome after Sertraline Overdose in a Child: A Case Report. Case Rep. Pediatr. 2013, 2013, 1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Muzyk AJ; Jakel RJ; Preud’homme X Serotonin Syndrome After a Massive Overdose of Controlled-Release Paroxetine. Psychosomatics 2010, 51, 437–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Kraai EP; Seifert SA Citalopram Overdose: a Fatal Case. J. Med. Toxicol. 2015, 11, 232–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Öström M; Eriksson A; Thorson J; Spigset O Fatal overdose with citalopram. Lancet 1996, 348, 339–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Lundmark J; Bengtsson F; Nordin C; Reis M; Wålinder J Therapeutic drug monitoring of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors influences clinical dosing strategies and reduces drug costs in depressed elderly patients. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2000, 101, 354–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Ostad Haji E; Mann K; Dragicevic A; Müller MJ; Boland K; Rao M-L; Fric M; Laux G; Hiemke C Potential Cost-effectiveness of for Depressed Patients Treated With Citalopram. Ther. Drug Monit. 2013, 35, 396–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Paulzen M; Goecke TW; Stingl JC; Janssen G; Stickeler E; Gründer, G.; Schoretsanitis, G. Pregnancy exposure to citalopram - Therapeutic drug monitoring in maternal blood, amniotic fluid and cord blood. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2017, 79, 213–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Malfará WR; Bertucci C; Costa Queiroz ME; Dreossi Carvalho SA; de Lourdes Pires Bianchi M; Cesarino EJ; Crippa JA; Costa Queiroz RH Reliable HPLC method for therapeutic drug monitoring of frequently prescribed tricyclic and nontricyclic antidepressants. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2007, 44, 955–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Xiong C; Ruan J; Cai Y; Tang Y Extraction and determination of some psychotropic drugs in urine samples using dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction followed by high-performance liquid chromatography. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2009, 49, 572–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Hall-Flavin DK; Winner JG; Allen JD; Carhart JM; Proctor B; Snyder KA; Drews MS; Eisterhold LL; Geske J; Mrazek DA Utility of integrated pharmacogenomic testing to support the treatment of major depressive disorder in a psychiatric outpatient setting. Pharmacogenet. Genomics 2013, 23, 535–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Tashkhourian J; Afsharinejad M; Zolghadr AR Colorimetric chiral discrimination and determination of S-citalopram based on induced aggregation of gold nanoparticles. Sens. Actuators, B 2016, 232, 52–59. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Madej M; Kochana J; Baś B Selective and Highly Sensitive Voltammetric Determination of Citalopram with Glassy Carbon Electrode. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 166, H359–H369. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Gutiérrez-Climente R; Gómez-Caballero A; Unceta N; Aránzazu Goicolea M; Barrio RJ A new potentiometric sensor based on chiral imprinted nanoparticles for the discrimination of the enantiomers of the antidepressant citalopram. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 196, 496–504. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Kragh-Sørensen P; Overø KF; Petersen OL; Jensen K; Parnas W The Kinetics of Citalopram: Single and Multiple Dose Studies in Man. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1981, 48, 53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Personne M; Sjöberg G; Person H Citalopram Overdose-Review of Cases Treated in Swedish Hospitals. J. Toxicol., Clin. Toxicol. 1997, 35, 237–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Sarigul N; Korkmaz F; Kurultak A New Artificial Urine Protocol to Better Imitate Human Urine. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, No. 20159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Bühlmann P; Chen LD Supramolecular Chemistry; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Ong V; Cortez NR; Xu Z; Amirghasemi F; Abd El-Rahman MK; Mousavi MPS An Accessible Yarn-Based Sensor for In-Field Detection of Succinylcholine Poisoning. Chemosensors 2023, 11, 175. [Google Scholar]

- (41).Mousavi MPS; Abd El-Rahman MK; Mahmoud AM; Abdelsalam RM; Bühlmann P In Situ Sensing of the Neurotransmitter Acetylcholine in a Dynamic Range of 1 nM to 1 mM. ACS Sens. 2018, 3, 2581–2589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Özbek O; Berkel C Recent advances in potentiometric analysis: Paper-based devices. Sens. Int. 2022, 3, No. 100189. [Google Scholar]

- (43).Guinovart T; Parrilla M; Crespo GA; Rius FX; Andrade FJ Potentiometric sensors using cotton yarns, carbon nanotubes and polymeric membranes. Analyst 2013, 138, 5208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Ainla A; Mousavi MPS; Tsaloglou M-N; Redston J; Bell JG; Fernández-Abedul MT; Whitesides GM Open-Source Potentiostat for Wireless Electrochemical Detection with Smartphones. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 6240–6246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Rowe AA; Bonham AJ; White RJ; Zimmer MP; Yadgar RJ; Hobza TM; Honea JW; Ben-Yaacov I; Plaxco KW CheapStat: An Open-Source, “Do-It-Yourself” Potentiostat for Analytical and Educational Applications. PLoS One 2011, 6, e23783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Izadyar A; Arachchige DR; Cornwell H; Hershberger JC Ion transfer stripping voltammetry for the detection of nanomolar levels of fluoxetine, citalopram, and sertraline in tap and river water samples. Sens. Actuators, B 2016, 223, 226–233. [Google Scholar]

- (47).Banks M; Amirghasemi F; Mitchell E; Mousavi MPS Home-Based Electrochemical Rapid Sensor (HERS): A Diagnostic Tool for Bacterial Vaginosis. Sensors 2023, 23, 1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Mousavi MPS; Ainla A; Tan EKW; K Abd El-Rahman M; Yoshida Y; Yuan L; Sigurslid HH; Arkan N; Yip MC; Abrahamsson CK; Homer-Vanniasinkam S; Whitesides GM Ion sensing with thread-based potentiometric electrodes. Lab Chip 2018, 18, 2279–2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Buck RP; Lindner E Recommendations for nomenclature of ionselective electrodes (IUPAC Recommendations 1994). Pure Appl. Chem. 1994, 66, 2527–2536. [Google Scholar]

- (50).Jansod S; Afshar MG; Crespo GA; Bakker E Phenytoin speciation with potentiometric and chronopotentiometric ion-selective membrane electrodes. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 79, 114–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Keller M Citalopram therapy for depression: a review of 10 years of European experience and data from US clinical trials. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2000, 61, 896–908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Viswanadhan VN; Ghose AK; Revankar GR; Robins RK Atomic physicochemical parameters for three dimensional structure directed quantitative structure-activity relationships. 4. Additional parameters for hydrophobic and dispersive interactions and their application for an automated superposition of certain naturally occurring nucleoside antibiotics. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 1989, 29, 163–172. [Google Scholar]