Abstract

Background

Anorexia of aging (AA) is a condition in older adults that includes loss of appetite and reduced food intake. There is a lack of detailed analysis of the potential influence of educational initiatives in addressing AA. This study aimed to clarify the current state of knowledge and practice regarding AA and its relationship with the availability of continuing education opportunities among Japanese healthcare professionals involved in treating older patients.

Methods

The Japan Geriatrics Society and the Japanese Association on Sarcopenia and Frailty, in collaboration with the Society on Sarcopenia, Cachexia, and Wasting Disorders, conducted an online questionnaire survey on the knowledge and practices in AA detection and management. Questions were asked in the areas of demographics, screening, definition/diagnosis, treatment, referral, and awareness, with those who ‘participate’ in continuing education and professional development programmes in nutrition for their patients were classified as the ‘education group’ and those who ‘do not participate’ were classified as the ‘non‐education group’. The results for each question were compared.

Results

The analysis included 870 participants (physicians, 48%; registered dietitians, 16%; rehabilitation therapists, 14%; pharmacists, 12%; nurses, 6%; and other professionals, 5%). The education group (45%) was more likely than the non‐education group (55%) to use the Mini‐Nutritional Assessment Short Form (MNA‐SF) to screen for AA (49% vs. 27%) and less likely not to use a validated tool (33% vs. 47%). More participants used evidence‐based tools and materials for AA care (38% vs. 12%), and fewer used their clinical judgement (23% vs. 35%) or were unaware of the tools and materials (9% vs. 23%). The proportion using a team of professionals experienced in AA care were 47% and 24% of the education and non‐education groups, respectively. By profession, few physicians used specific validated tools and resources for AA screening and treatment. More than half of the dietitians used the MNA‐SF regardless of training opportunity availability. Regarding professional availability and team use, differences in educational opportunities were particularly large among physicians.

Conclusions

Participation in continuing education programmes on nutrition is associated with responsiveness to AA screening and treatment and the availability of a team of professionals, which may influence the quality of AA treatment. Nutrition education may support the confidence of healthcare professionals working with older adults in AA with complex clinical signs and encourage them to conduct evidence‐based practice.

Keywords: Anorexia of aging, Continuing education, Geriatric anorexia, Healthcare professionals, Older patients

Introduction

Loss of appetite and reduced food intake in older adults are common symptoms affecting approximately 30–40% of hospitalized older adults, 10% of community‐dwelling older adults, and 10–30% of nursing home residents. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 The prevalence of this syndrome increases with age, raising concerns that they may be perceived as an inevitable consequence of aging and thus overlooked without appropriate intervention despite having numerous reversible aetiologies. 4 , 6 , 7

Untreated conditions increase the risk of malnutrition, sarcopenia, frailty, and cachexia, often culminating in adverse outcomes such as hospitalization and mortality. 2 , 4 , 5 , 7 , 8 , 9 Consequently, these symptoms in older people were conceptualized in the late 1980s as a geriatric syndrome termed anorexia of aging (AA). 10 , 11 Addressing AA has become imperative, particularly in aged societies.

Recognizing this urgency, the Society on Sarcopenia, Cachexia, and Wasting Disorders (SCWD) conducted a survey in 2022 among healthcare professionals, including physicians and dietitians, who specialize in caring for older adults with AA. 12 Although many respondents demonstrated familiarity with the concept, the use of evidence‐based assessment tools for screening and diagnosing AA remains limited. Instead, appetite assessments often rely on subjective interviews and clinical judgement. In addition, a significant proportion of the respondents perceived appetite loss in older adults as inevitable and cited the lack of robust evidence for effective treatments as a barrier to intervention.

As new knowledge and expert opinions are updated on these issues, it is essential to have opportunities for active information gathering and education to better respond to these issues. Among the survey respondents, approximately 60% reported participation in voluntary nutrition education, and the remaining 40% did not have such opportunities. We raise a question regarding the potential influence of educational initiatives in addressing AA. However, detailed analyses of this influence are lacking. 12

Therefore, this study aimed to analyse data from the aforementioned SCWD questionnaire survey of healthcare professionals caring for older adults in Japan, specifically examining the association between current understanding and management of AA and continuing education opportunity availability.

Methods

The project was spearheaded by the SCWD and was conducted in collaboration with relevant societies in Europe, Japan, Latin America, and the United States. 12 This international effort included several components: (1) a comprehensive literature review of both seminal and recent articles elucidating the definition, aetiology, and therapeutic strategies related to AA; (2) focus group discussions with clinical authorities; and (3) a survey of practicing healthcare professionals (HCPs) affiliated with the collaborating societies to obtain quantitative evidence. A mixed‐methods approach was used to ensure a comprehensive exploration. An International Advisory Board (IAB) was convened to review the current standards of care for anorexia in older adults and to identify deficiencies in professional practice among HCPs in their respective countries.

The formulation of the Japanese iteration of the questionnaire was overseen by the SCWD in collaboration with members of the Japan Geriatrics Society and the Japanese Association on Sarcopenia and Frailty. A web‐based survey was administered to relevant societies, including the Japan Geriatrics Society, the Japanese Association on Sarcopenia and Frailty, the Japanese Association of Rehabilitation Nutrition, the Japanese Society of Geriatric Pharmacy, the Japan Geriatric Therapy Society, the Japan Academy of Gerontological Nursing, the Japanese Society of Clinical Nutrition, and the Japan Home Nutrition Management Society.

Survey

The quantitative survey comprised 26 items, including multiple‐choice, Likert scale, and open‐ended formats. The online questionnaire took approximately 20 min to complete and included various domains, including respondent demographics (four items), screening (five items), defining/diagnosing (five items), treating (four items), referrals (two items), and attitudes/perceptions (six items). The Japanese version of the survey was distributed electronically using QuestionPro between 16 June and 5 October 2022. Upon completion of the survey, data were extracted from QuestionPro© and analysed. To ensure confidentiality, all data were collected anonymously, and IP addresses were removed.

The selection criteria for respondents in this analysis were those who selected ‘Japan’ in response to item 4 ‘Please enter the country where you are currently working.’ Those who did not respond to the following items were excluded from the analysis: item 1, ‘Please indicate your current health care profession.’; item 10, ‘In the absence of an explicit cause such as acute illness, anorexia in older adults is most accurately defined as:’; item 15, ‘I use tools and resources such as evidence‐based guidelines developed by experts to care for my older patients with anorexia.’, item 26, ‘I participate in continuing education/continuing professional development on nutrition for (select all that apply).’

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, and percentages, were included in the analysis, along with summaries of open‐ended responses. The response rates were assessed by dividing the single‐response items by the total number of respondents per item. For multiple response items (select all that apply), the response rate was calculated based on the number of respondents included in the analysis, regardless of any reduction in the number of respondents over time. For item 26, ‘I participate in continuing education/continuing professional development on nutrition for (select all that apply):’ respondents who selected ‘All patients’, ‘Older patients’, or ‘Older patients with anorexia’ were categorized as the ‘education group’, while those who selected ‘I do not engage in continuing education/continuing professional development on nutrition’ were categorized as the ‘non‐education group’. Single‐response items were compared between the two groups using the chi‐square test. For certain items, only physicians or registered dietitians, who typically have greater opportunities to intervene independently in patients experiencing AA, were selected for comparison based on their educational status. All reported P‐values were two‐tailed, and a significance level of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using EZR (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan), 13 a modified version of R commander designed to include commonly used statistical functions in biostatistics based on R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

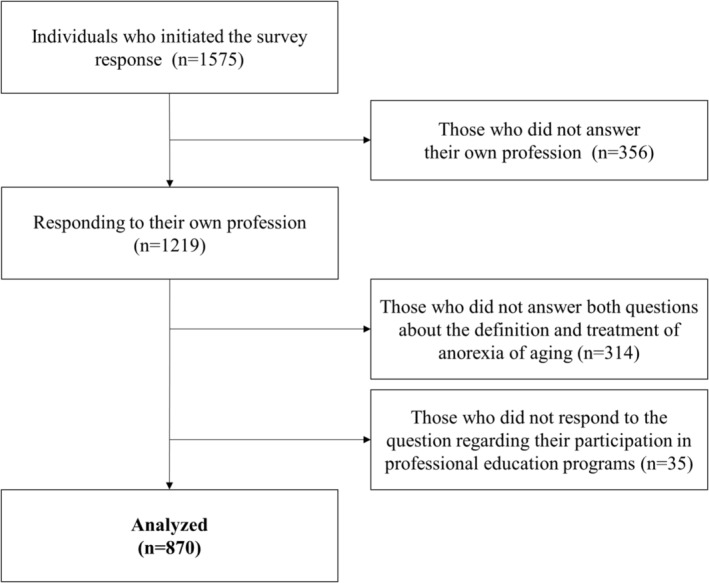

From the 1575 respondents initially surveyed, individuals who did not respond to questions about their profession (n = 356), definition and treatment of AA (n = 314), and participation in professional education programmes (n = 35) were excluded. A total of 870 respondents were included (Figure 1). The participant pool comprised 416 physicians (47.8%), 140 registered dietitians (16.1%), 120 rehabilitation therapists (physical therapists, occupational therapists, and speech‐language pathologists) (13.8%), 100 pharmacists (11.5%), 50 nurses (5.7%), and 44 other professions (5.1%). The most common specialties among the respondents were physical medicine/rehabilitation (16.4%) (19 physicians, 2.2% of the total), geriatrics (15.6%), and internal medicine (9.5%) (Table 1). Regarding the practice setting, most respondents (59.7%) worked primarily in hospitals, followed by home health care or clinics (18.4%) and nursing homes (11.3%) (data not shown). Of the respondents, 395 (45.4%) had participated in continuing education or professional development programmes focused on patient nutrition. The distribution of educational participants in each job category was as follows: 42.0% physicians, 24.3% registered dietitians, 14.4% therapists, 9.1% pharmacists, 5.1% nurses, and 5.1% other professions (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the selection of subjects in the Japanese subgroup analysis.

Table 1.

Respondent demographics

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Health profession | ||

| Primary care or general practice physician/medical doctor | 186 | 21.4% |

| Specialist physician/medical doctor | 230 | 26.4% |

| Physician assistant | 2 | 0.2% |

| Advanced practice nurse (e.g., nurse practitioner) | 16 | 1.8% |

| Registered nurse/nurse | 34 | 3.9% |

| Pharmacist | 100 | 11.5% |

| Occupational therapist | 14 | 1.6% |

| Physical therapist | 76 | 8.7% |

| Dietitian/registered dietitian | 140 | 16.1% |

| Social worker | 2 | 0.2% |

| Psychologist | 2 | 0.2% |

| Speech/language therapist | 30 | 3.4% |

| Other mental health provider/counsellor | 1 | 0.1% |

| Education specialist | 4 | 0.5% |

| Other (free text) | 33 | 3.8% |

| Specialty (if applicable) | ||

| Allergy and immunology | 3 | 0.3% |

| Cardiology | 52 | 6.0% |

| Endocrinology | 36 | 4.1% |

| Geriatrics | 136 | 15.6% |

| Gastroenterology | 15 | 1.7% |

| Internal medicine | 83 | 9.5% |

| Neurology | 55 | 6.3% |

| Oncology | 2 | 0.2% |

| Otorhinolaryngology | 4 | 0.5% |

| Physical medicine/rehabilitation | 143 | 16.4% |

| Psychiatry | 16 | 1.8% |

| Pulmonology | 16 | 1.8% |

| Rheumatology | 3 | 0.3% |

| General surgery | 14 | 1.6% |

| Surgical specialty | 15 | 1.7% |

| Other | 169 | 19.4% |

| Missing system | 108 | 12.4% |

| Primary practice location | ||

| Academic medical centre | 124 | 14.3% |

| Private hospital | 272 | 31.3% |

| Public hospital | 123 | 14.1% |

| Multispecialty group practice | 14 | 1.6% |

| Long‐term care/nursing home | 98 | 11.3% |

| Solo practice | 57 | 6.6% |

| Specialty group practice | 5 | 0.6% |

| Community‐based health centre/clinic | 19 | 2.2% |

| Home health care | 79 | 9.1% |

| Veterans administration medical centre/military facility | 0 | 0.0% |

| National health service/government | 11 | 1.3% |

| Other | 49 | 5.6% |

| Missing system | 19 | 2.2% |

Table 2 presents the findings regarding AA screening. Significantly higher percentages of respondents in the education group reported assessing appetite and taking weight at each visit than those without training. The most commonly used screening tool was the Mini‐Nutritional Assessment Short Form (MNA‐SF), used by 49.1% of the respondents in the education group and 27.4% in the non‐education group. Conversely, almost half of the respondents in the non‐educated group and approximately one‐third in the educated group did not use any screening tools.

Table 2.

Domain (screening): Screening for anorexia of aging

| Overall (n = 870) | Education group (n = 395) | Non‐education group (n = 475) | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Is appetite in older adults assessed at each visit? | |||||||

| Yes | 619 | 71.1% | 302 | 76.5% | 317 | 66.7% | 0.006 |

| No | 165 | 19.0% | 67 | 17.0% | 98 | 20.6% | |

| Unsure | 27 | 3.1% | 7 | 1.8% | 20 | 4.2% | |

| Not applicable for my practice setting | 53 | 6.1% | 17 | 4.3% | 36 | 7.6% | |

| Missing system | 6 | 0.7% | 2 | 0.5% | 4 | 0.8% | |

| Are older adults weighed at each visit using a weighing scale? | |||||||

| Yes | 341 | 39.2% | 186 | 47.1% | 155 | 32.6% | <0.001 |

| No | 428 | 49.2% | 172 | 43.5% | 256 | 53.9% | |

| Unsure | 20 | 2.3% | 8 | 2.0% | 12 | 2.5% | |

| Not applicable for my practice setting | 71 | 8.2% | 25 | 6.3% | 46 | 9.7% | |

| Missing system | 10 | 1.1% | 4 | 1.0% | 6 | 1.3% | |

| How often should older adults be screened for appetite loss (select all that apply)? | |||||||

| At each appointment | 395 | 45.4% | 198 | 50.1% | 197 | 41.5% | |

| At least annually | 154 | 17.7% | 74 | 18.7% | 80 | 16.8% | |

| When the older adult has lost a determined percentage of body weight (example: >10% body weight in the last 3 months) | 465 | 53.4% | 205 | 51.9% | 260 | 54.7% | |

| When the older adult or family member expresses concern | 242 | 27.8% | 106 | 26.8% | 136 | 28.6% | |

| I do not know | 15 | 1.7% | 5 | 1.3% | 10 | 2.1% | |

| I do not screen older adults for appetite | 16 | 1.8% | 3 | 0.8% | 13 | 2.7% | |

| Who is responsible for screening older adults for appetite loss (choose all that apply)? | |||||||

| The primary treating physician | 518 | 59.5% | 231 | 58.5% | 287 | 60.4% | |

| The nurse (nurse or advanced practice nurse) | 508 | 58.4% | 228 | 57.7% | 280 | 58.9% | |

| Physician assistant | 33 | 3.8% | 13 | 3.3% | 20 | 4.2% | |

| The dietitian/registered dietitian/nutritionist (non‐physician) | 436 | 50.1% | 226 | 57.2% | 210 | 44.2% | |

| Medical or nursing assistant | 51 | 5.9% | 28 | 7.1% | 23 | 4.8% | |

| Physical therapist | 105 | 12.1% | 52 | 13.2% | 53 | 11.2% | |

| Pharmacist | 73 | 8.4% | 34 | 8.6% | 39 | 8.2% | |

| Social worker | 34 | 3.9% | 18 | 4.6% | 16 | 3.4% | |

| I do not know | 24 | 2.8% | 11 | 2.8% | 13 | 2.7% | |

| No one | 21 | 2.4% | 4 | 1.0% | 17 | 3.6% | |

| Other (free text) | 76 | 8.7% | 41 | 10.4% | 35 | 7.4% | |

| Not applicable for my practice setting | 10 | 1.1% | 2 | 0.5% | 8 | 1.7% | |

| The tools used in my practice setting to screen older adults for appetite loss include (select all that apply) | |||||||

| Appetite, Hunger and Sensory Perception Questionnaire (AHSPQ) | 10 | 1.1% | 6 | 1.5% | 4 | 0.8% | |

| Council on Nutrition Appetite Questionnaire (CNAQ) | 23 | 2.6% | 15 | 3.8% | 8 | 1.7% | |

| Functional Assessment of Anorexia and Cachexia Therapy (FAACT) | 6 | 0.7% | 3 | 0.8% | 3 | 0.6% | |

| Malnutrition Screening Tool (MST) | 17 | 2.0% | 9 | 2.3% | 8 | 1.7% | |

| Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST) | 33 | 3.8% | 22 | 5.6% | 11 | 2.3% | |

| Mini‐Nutritional Assessment Short Form (MNA‐SF) | 324 | 37.2% | 194 | 49.1% | 130 | 27.4% | |

| Nutritional Risk Screening (NRS) | 21 | 2.4% | 11 | 2.8% | 10 | 2.1% | |

| Rapid Geriatric Assessment (RGA) | 5 | 0.6% | 3 | 0.8% | 2 | 0.4% | |

| Simplified Nutritional Appetite Questionnaire (SNAQ) | 17 | 2.0% | 11 | 2.8% | 6 | 1.3% | |

| Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) | 11 | 1.3% | 3 | 0.8% | 8 | 1.7% | |

| Informal clinical interview | 56 | 6.4% | 31 | 7.8% | 25 | 5.3% | |

| Tool developed by my organization or association | 19 | 2.2% | 10 | 2.5% | 9 | 1.9% | |

| We do not use a tool to screen older patients for appetite loss | 350 | 40.2% | 129 | 32.7% | 221 | 46.5% | |

| I do not know | 74 | 8.5% | 20 | 5.1% | 54 | 11.4% | |

| I do not screen older adults for appetite loss | 49 | 5.6% | 13 | 3.3% | 36 | 7.6% | |

| Other (free text) | 42 | 4.8% | 21 | 5.3% | 21 | 4.4% | |

Data are presented as N, %, chi‐square test.

Table 3 presents items related to the definition and treatment of AA. Among the respondents, 52.5% defined AA as a loss of appetite and/or low food intake in older adults’. Regarding the use of evidence‐based tools and resources to treat AA, those with educational opportunities were more likely to use such tools and were less likely to report being unaware of them. In addition, a significantly higher proportion of respondents in the education group expressed confidence in the provision of nutritional and physical activity recommendations to older adults with anorexia. The most commonly selected general evidence‐based or consensus‐developed interventions for anorexia were the treatment of swallowing disorders (84.9%), addressing dentition issues (84.8%), and incorporating energy‐ and protein‐fortified foods into the diet (81.4%). In addition, more respondents in the education group reported having access to specialists for further assessment and treatment than those in the non‐education group.

Table 3.

Domain (defining and treating): Defining and treating anorexia of aging

| Overall (n = 870) | Education group (n = 395) | Non‐education group (n = 475) | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| In the absence of an explicit cause such as acute illness, anorexia in older adults is most accurately defined as | |||||||

| Loss of appetite and/or low food intake in older adults | 457 | 52.5% | 207 | 52.4% | 250 | 52.6% | 0.830 |

| Unintended weight loss in older adults | 155 | 17.8% | 71 | 18.0% | 84 | 17.7% | |

| Sarcopenia or loss of muscle mass, strength and/or function | 77 | 8.9% | 38 | 9.6% | 39 | 8.2% | |

| Nutrition risk, malnutrition or undernutrition in older adults | 115 | 13.2% | 53 | 13.4% | 62 | 13.1% | |

| Frailty in geriatric patients | 66 | 7.6% | 26 | 6.6% | 40 | 8.4% | |

| I use tools and resources such as evidence‐based guidelines developed by experts to care for my older patients with anorexia. | |||||||

| Yes, all of the time | 50 | 5.7% | 37 | 9.4% | 13 | 2.7% | <0.001 |

| Yes, most of the time | 160 | 18.4% | 114 | 28.9% | 46 | 9.7% | |

| Rarely | 189 | 21.7% | 100 | 25.3% | 89 | 18.7% | |

| No, I prefer to use my own clinical judgement | 259 | 29.8% | 92 | 23.3% | 167 | 35.2% | |

| No, I am not aware of tools and resources to care for my geriatric patients with anorexia | 142 | 16.3% | 35 | 8.9% | 107 | 22.5% | |

| No, I do not use tools and resources because I do not have access to them | 19 | 2.2% | 5 | 1.3% | 14 | 2.9% | |

| Not applicable for my professional role/responsibility | 51 | 5.9% | 12 | 3.0% | 39 | 8.2% | |

| When a diagnosis of anorexia in older adults is made, evidence‐based or consensus developed interventions may include (select all that apply) | |||||||

| Incorporating energy‐ and protein‐fortified foods in the diet | 708 | 81.4% | 334 | 84.6% | 374 | 78.7% | |

| Recommending oral nutritional supplements (e.g., Boost and Ensure) | 691 | 79.4% | 312 | 79.0% | 379 | 79.8% | |

| Addressing dentition issues | 738 | 84.8% | 338 | 85.6% | 400 | 84.2% | |

| Treating swallowing disorders (if present) | 739 | 84.9% | 343 | 86.8% | 396 | 83.4% | |

| Prescribing appetite stimulants (e.g., megace and dronabinol) | 166 | 19.1% | 85 | 21.5% | 81 | 17.1% | |

| Prescribing antidepressants | 263 | 30.2% | 134 | 33.9% | 129 | 27.2% | |

| Prescribing physical exercise | 434 | 49.9% | 197 | 49.9% | 237 | 49.9% | |

| Prescribing nutritional counselling | 508 | 58.4% | 238 | 60.3% | 270 | 56.8% | |

| Revising current prescriptions that are causing side effects | 614 | 70.6% | 282 | 71.4% | 332 | 69.9% | |

| Treating constipation | 609 | 70.0% | 278 | 70.4% | 331 | 69.7% | |

| Reviewing already prescribed medications | 616 | 70.8% | 281 | 71.1% | 335 | 70.5% | |

| Referring to specialist for psychosocial support | 298 | 34.3% | 136 | 34.4% | 162 | 34.1% | |

| Referring to support services (e.g., social worker, financial counsellor, and transportation assistance) | 355 | 40.8% | 155 | 39.2% | 200 | 42.1% | |

| Screening for abuse and/or neglect | 247 | 28.4% | 111 | 28.1% | 136 | 28.6% | |

| Other (free text) | 3 | 0.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 3 | 0.6% | |

| I do not know | 6 | 0.7% | 2 | 0.5% | 4 | 0.8% | |

| Not applicable for my professional role/responsibility | 10 | 1.1% | 3 | 0.8% | 7 | 1.5% | |

| I am confident in providing nutrition recommendations for older patients with anorexia. | |||||||

| Strongly agree | 199 | 22.9% | 116 | 29.4% | 83 | 17.5% | <0.001 |

| Agree | 395 | 45.4% | 198 | 50.1% | 197 | 41.5% | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 193 | 22.2% | 62 | 15.7% | 131 | 27.6% | |

| Disagree | 45 | 5.2% | 13 | 3.3% | 32 | 6.7% | |

| Strongly disagree | 12 | 1.4% | 1 | 0.3% | 11 | 2.3% | |

| Not applicable for my professional role/responsibility | 22 | 2.5% | 4 | 1.0% | 18 | 3.8% | |

| Missing system | 4 | 0.5% | 1 | 0.3% | 3 | 0.6% | |

| I am confident in providing physical activity recommendations for older patients with anorexia. | |||||||

| Strongly agree | 151 | 17.4% | 88 | 22.3% | 63 | 13.3% | <0.001 |

| Agree | 413 | 47.5% | 210 | 53.2% | 203 | 42.7% | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 212 | 24.4% | 73 | 18.5% | 139 | 29.3% | |

| Disagree | 55 | 6.3% | 15 | 3.8% | 40 | 8.4% | |

| Strongly disagree | 6 | 0.7% | 1 | 0.3% | 5 | 1.1% | |

| Not applicable for my professional role/responsibility | 26 | 3.0% | 5 | 1.3% | 21 | 4.4% | |

| Missing system | 7 | 0.8% | 3 | 0.8% | 4 | 0.8% | |

| There are sufficient specialists available for me to refer my older adult patients with anorexia for additional assessment and/or treatment. | |||||||

| Yes, all of the time | 63 | 7.2% | 42 | 10.6% | 21 | 4.4% | <0.001 |

| Yes, most of the time | 287 | 33.0% | 153 | 38.7% | 134 | 28.2% | |

| Rarely | 166 | 19.1% | 83 | 21.0% | 83 | 17.5% | |

| No | 267 | 30.7% | 87 | 22.0% | 180 | 37.9% | |

| Not applicable for my professional role/responsibility | 83 | 9.5% | 26 | 6.6% | 57 | 12.0% | |

| Missing system | 4 | 0.5% | 4 | 1.0% | 0 | 0.0% | |

Data are presented as N, %, chi‐square test.

Table 4 presents items related to attitudes and perceptions about AA. Just over 50% of respondents agreed with the statements ‘Anorexia is unavoidable in geriatric patients’ and ‘Lack of high‐quality evidence to guide the care and treatment of older patients with anorexia makes it challenging for me as a clinician to choose treatment’. In addition, 46.6% of those with educational opportunities reported having access to a team of professionals experienced in caring for older adults with anorexia, compared with 24.2% of those without educational opportunities.

Table 4.

Domain (attitudes and perceptions): Perceptions and attitudes in the care of older patients with anorexia of aging

| Overall (n = 870) | Education group (n = 395) | Non‐education group (n = 475) | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Anorexia is unavoidable in geriatric patients. | |||||||

| Strongly agree | 146 | 16.8% | 76 | 19.2% | 70 | 14.7% | 0.307 |

| Agree | 363 | 41.7% | 164 | 41.5% | 199 | 41.9% | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 235 | 27.0% | 101 | 25.6% | 134 | 28.2% | |

| Disagree | 119 | 13.7% | 50 | 12.7% | 69 | 14.5% | |

| Strongly disagree | 6 | 0.7% | 4 | 1.0% | 2 | 0.4% | |

| Missing system | 1 | 0.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.2% | |

| The regular use of standardized tools to evaluate older patients for weight loss is critical. | |||||||

| Strongly agree | 355 | 40.8% | 182 | 46.1% | 173 | 36.4% | 0.012 |

| Agree | 442 | 50.8% | 191 | 48.4% | 251 | 52.8% | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 57 | 6.6% | 17 | 4.3% | 40 | 8.4% | |

| Disagree | 11 | 1.3% | 3 | 0.8% | 8 | 1.7% | |

| Strongly disagree | 2 | 0.2% | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | 0.2% | |

| Missing system | 3 | 0.3% | 1 | 0.3% | 2 | 0.4% | |

| Lack of high‐quality evidence to guide the care and treatment of older patients with anorexia makes it challenging for me as a clinician to choose treatment. | |||||||

| Strongly agree | 94 | 10.8% | 41 | 10.4% | 53 | 11.2% | 0.046 |

| Agree | 368 | 42.3% | 174 | 44.1% | 194 | 40.8% | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 236 | 27.1% | 91 | 23.0% | 145 | 30.5% | |

| Disagree | 142 | 16.3% | 71 | 18.0% | 71 | 14.9% | |

| Strongly disagree | 27 | 3.1% | 17 | 4.3% | 10 | 2.1% | |

| Missing system | 3 | 0.3% | 1 | 0.3% | 2 | 0.4% | |

| I have access to an interprofessional team with experience in the care of older adults with anorexia. | |||||||

| Yes, all of the time | 66 | 7.6% | 45 | 11.4% | 21 | 4.4% | <0.001 |

| Yes, most of the time | 233 | 26.8% | 139 | 35.2% | 94 | 19.8% | |

| Rarely | 192 | 22.1% | 94 | 23.8% | 98 | 20.6% | |

| No | 343 | 39.4% | 109 | 27.6% | 234 | 49.3% | |

| Not applicable for my professional role/responsibility | 33 | 3.8% | 6 | 1.5% | 27 | 5.7% | |

| Missing system | 3 | 0.3% | 2 | 0.5% | 1 | 0.2% | |

| I involve caregivers such as family members as collaborators in supporting the older adult with anorexia. | |||||||

| Strongly agree | 213 | 24.5% | 112 | 28.4% | 101 | 21.3% | <0.001 |

| Agree | 539 | 62.0% | 250 | 63.3% | 289 | 60.8% | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 100 | 11.5% | 29 | 7.3% | 71 | 14.9% | |

| Disagree | 12 | 1.4% | 2 | 0.5% | 10 | 2.1% | |

| Strongly disagree | 3 | 0.3% | 1 | 0.3% | 2 | 0.4% | |

| Missing system | 3 | 0.3% | 1 | 0.3% | 2 | 0.4% | |

Data are presented as N, %, chi‐square test.

Tables 5, 6, 7 present the results for physicians and registered dietitians, focusing mainly on items where differences were observed due to participation in the educational programme. For screening for anorexia in older adults, a higher percentage of physicians refrained from using screening tools compared to the total respondent pool, with 40.4% in the education group and 59.6% in the non‐education group. In contrast, more than half of the registered dietitians in both groups used the MNA‐SF (Table 5). Regarding the treatment of anorexia in older patients, the majority of physicians with no education reported relying on their own clinical judgement (Table 6). In addition, consultation with specialists and teams was significantly higher among both physicians and registered dietitians with education, with particularly pronounced differences among physicians based on education status (Table 7).

Table 5.

Comparison of screening for anorexia of aging in physicians and registered dietitians with and without education

| Physicians (n = 416) | Registered dietitians (n = 140) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education group (n = 166) | Non‐education group (n = 250) | P value | Education group (n = 96) | Non‐education group (n = 44) | P value | |||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| Is appetite in older adults assessed at each visit? | ||||||||||

| Yes | 134 | 80.7% | 197 | 78.8% | 0.250 | 79 | 82.3% | 30 | 68.2% | 0.074 |

| No | 32 | 19.3% | 45 | 18.0% | 8 | 8.3% | 8 | 18.2% | ||

| Unsure | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 0.8% | 1 | 1.0% | 3 | 6.8% | ||

| Not applicable for my practice setting | 0 | 0.0% | 4 | 1.6% | 8 | 8.3% | 3 | 6.8% | ||

| Missing system | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 0.8% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | ||

| Are older adults weighed at each visit using a weighing scale? | ||||||||||

| Yes | 88 | 53.0% | 100 | 40.0% | 0.026 | 55 | 57.3% | 19 | 43.2% | 0.268 |

| No | 77 | 46.4% | 143 | 57.2% | 26 | 27.1% | 19 | 43.2% | ||

| Unsure | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.4% | 4 | 4.2% | 1 | 2.3% | ||

| Not applicable for my practice setting | 0 | 0.0% | 4 | 1.6% | 10 | 10.4% | 4 | 9.1% | ||

| Missing system | 1 | 0.6% | 2 | 0.8% | 1 | 1.0% | 1 | 2.3% | ||

| The tools used in my practice setting to screen older adults for appetite loss include (select all that apply) | ||||||||||

| Appetite, Hunger and Sensory Perception Questionnaire (AHSPQ) | 6 | 3.6% | 3 | 1.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | ||

| Council on Nutrition Appetite Questionnaire (CNAQ) | 7 | 4.2% | 2 | 0.8% | 6 | 6.3% | 3 | 6.8% | ||

| Functional Assessment of Anorexia and Cachexia Therapy (FAACT) | 3 | 1.8% | 2 | 0.8% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | ||

| Malnutrition Screening Tool (MST) | 7 | 4.2% | 5 | 2.0% | 1 | 1.0% | 0 | 0.0% | ||

| Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST) | 7 | 4.2% | 5 | 2.0% | 12 | 12.5% | 1 | 2.3% | ||

| Mini‐Nutritional Assessment Short Form (MNA‐SF) | 69 | 41.6% | 48 | 19.2% | 59 | 61.5% | 22 | 50.0% | ||

| Nutritional Risk Screening (NRS) | 2 | 1.2% | 7 | 2.8% | 4 | 4.2% | 1 | 2.3% | ||

| Rapid Geriatric Assessment (RGA) | 1 | 0.6% | 1 | 0.4% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | ||

| Simplified Nutritional Appetite Questionnaire (SNAQ) | 6 | 3.6% | 2 | 0.8% | 5 | 5.2% | 1 | 2.3% | ||

| Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) | 0 | 0.0% | 5 | 2.0% | 2 | 2.1% | 0 | 0.0% | ||

| Informal clinical interview | 17 | 10.2% | 17 | 6.8% | 5 | 5.2% | 1 | 2.3% | ||

| Tool developed by my organization or association | 5 | 3.0% | 5 | 2.0% | 4 | 4.2% | 4 | 9.1% | ||

| We do not use a tool to screen older patients for appetite loss | 67 | 40.4% | 149 | 59.6% | 22 | 22.9% | 12 | 27.3% | ||

| I do not know | 2 | 1.2% | 12 | 4.8% | 4 | 4.2% | 3 | 6.8% | ||

| I do not screen older adults for appetite loss | 5 | 3.0% | 17 | 6.8% | 3 | 3.1% | 3 | 6.8% | ||

| Other (free text) | 5 | 3.0% | 13 | 5.2% | 8 | 8.3% | 2 | 4.5% | ||

Data are presented as N, %, chi‐square test.

Table 6.

Comparison of treating for anorexia of aging in physicians and registered dietitians with and without education

| Physicians (n = 416) | Registered dietitians (n = 140) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education group (n = 166) | Non‐education group (n = 250) | P value | Education group (n = 96) | Non‐education group (n = 44) | P value | |||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| I use tools and resources such as evidence‐based guidelines developed by experts to care for my older patients with anorexia. | ||||||||||

| Yes, all of the time | 10 | 6.0% | 8 | 3.2% | <0.001 | 15 | 15.6% | 2 | 4.5% | 0.140 |

| Yes, most of the time | 48 | 28.9% | 16 | 6.4% | 35 | 36.5% | 11 | 25.0% | ||

| Rarely | 42 | 25.3% | 39 | 15.6% | 23 | 24.0% | 12 | 27.3% | ||

| No, I prefer to use my own clinical judgement | 50 | 30.1% | 129 | 51.6% | 13 | 13.5% | 10 | 22.7% | ||

| No, I am not aware of tools and resources to care for my geriatric patients with anorexia | 13 | 7.8% | 47 | 18.8% | 6 | 6.3% | 6 | 13.6% | ||

| No, I do not use tools and resources because I do not have access to them | 2 | 1.2% | 6 | 2.4% | 1 | 1.0% | 2 | 4.5% | ||

| Not applicable for my professional role/responsibility | 1 | 0.6% | 5 | 2.0% | 3 | 3.1% | 1 | 2.3% | ||

| I am confident in providing nutrition recommendations for older patients with anorexia. | ||||||||||

| Strongly agree | 52 | 31.3% | 39 | 15.6% | <0.001 | 37 | 38.5% | 19 | 43.2% | 0.201 |

| Agree | 81 | 48.8% | 108 | 43.2% | 50 | 52.1% | 16 | 36.4% | ||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 24 | 14.5% | 75 | 30.0% | 8 | 8.3% | 8 | 18.2% | ||

| Disagree | 6 | 3.6% | 23 | 9.2% | 1 | 1.0% | 1 | 2.3% | ||

| Strongly disagree | 1 | 0.6% | 2 | 0.8% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | ||

| Not applicable for my professional role/responsibility | 1 | 0.6% | 1 | 0.4% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | ||

| Missing system | 1 | 0.6% | 2 | 0.8% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | ||

| I am confident in providing physical activity recommendations for older patients with anorexia. | ||||||||||

| Strongly agree | 41 | 24.7% | 35 | 14.0% | <0.001 | 16 | 16.7% | 7 | 15.9% | 0.043 |

| Agree | 89 | 53.6% | 109 | 43.6% | 58 | 60.4% | 17 | 38.6% | ||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 30 | 18.1% | 78 | 31.2% | 15 | 15.6% | 17 | 38.6% | ||

| Disagree | 5 | 3.0% | 20 | 8.0% | 2 | 2.1% | 2 | 4.5% | ||

| Strongly disagree | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 0.8% | 1 | 1.0% | 1 | 2.3% | ||

| Not applicable for my professional role/responsibility | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 0.8% | 2 | 2.1% | 0 | 0.0% | ||

| Missing system | 1 | 0.6% | 4 | 1.6% | 2 | 2.1% | 0 | 0.0% | ||

Data are presented as N, %, chi‐square test.

Table 7.

Comparison of referrals for anorexia of aging in physicians and registered dietitians with and without education

| Physicians (n = 416) | Registered dietitians (n = 140) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education group (n = 166) | Non‐education group (n = 250) | P value | Education group (n = 96) | Non‐education group (n = 44) | P value | |||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| There are sufficient specialists available for me to refer my older adult patients with anorexia for additional assessment and/or treatment. | ||||||||||

| Yes, all of the time | 18 | 10.8% | 13 | 5.2% | <0.001 | 13 | 7.8% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.029 |

| Yes, most of the time | 66 | 39.8% | 73 | 29.2% | 38 | 22.9% | 18 | 7.2% | ||

| Rarely | 39 | 23.5% | 46 | 18.4% | 20 | 12.0% | 6 | 2.4% | ||

| No | 33 | 19.9% | 102 | 40.8% | 15 | 9.0% | 13 | 5.2% | ||

| Not applicable for my professional role/responsibility | 8 | 4.8% | 16 | 6.4% | 9 | 5.4% | 7 | 2.8% | ||

| Missing system | 2 | 1.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.6% | 0 | 0.0% | ||

| I have access to an interprofessional team with experience in the care of older adults with anorexia. | ||||||||||

| Yes, all of the time | 19 | 11.4% | 11 | 4.4% | <0.001 | 12 | 7.2% | 3 | 1.2% | 0.034 |

| Yes, most of the time | 58 | 34.9% | 50 | 20.0% | 32 | 19.3% | 10 | 4.0% | ||

| Rarely | 46 | 27.7% | 61 | 24.4% | 23 | 13.9% | 8 | 3.2% | ||

| No | 42 | 25.3% | 122 | 48.8% | 25 | 15.1% | 23 | 9.2% | ||

| Not applicable for my professional role/responsibility | 1 | 0.6% | 6 | 2.4% | 4 | 2.4% | 0 | 0.0% | ||

| Missing system | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | ||

Data are presented as N, %, chi‐square test.

Discussion

In this study, a Japanese sub‐analysis of global surveys was conducted among healthcare professionals involved in anorexia treatment in older adults. 12 Our findings shed light on several key aspects of AA. Despite the high frequency of appetite assessment, over 40% of the respondents did not use professionally developed tools for screening and treatment. In addition, more than half of the respondents believed that appetite loss is inevitable in older patients and lamented the lack of high‐quality evidence for treatment, which poses a challenge in initiating interventions for AA. In addition, a significant proportion of the respondents did not participate in continuing education or professional development programmes related to nutrition. Notably, participation in such educational initiatives correlated with more standardized measures of response to screening and treatment for AA, as well as improved access to specialist referrals and interdisciplinary teams. These findings underscore the importance of continuous education in this field.

In this study, there were notable disparities in the screening and treatment of appetite loss among older adults as a function of participation in continuing education and professional development programmes focused on nutrition. In our Japanese survey, less than half the respondents participated in continuing education opportunities related to nutrition, a proportion lower than that observed in the overall survey dataset. 12 This may be due to the lack of an established continuing medical education system in Japan compared to other countries, which may have resulted in fewer opportunities for Japanese respondents to participate in educational efforts. Individuals with educational opportunities demonstrated higher frequencies of appetite assessment and weighing as well as increased use of evidence‐based screening tools. They also demonstrated greater confidence in recommending nutritional and physical activity interventions for older adults with anorexia during treatment. Additionally, respondents with educational opportunities were more likely to report access to a team of professionals experienced in managing anorexia among older adults. Those with educational opportunities likely recognized the importance of a collaborative team approach for treating anorexia in older patients. In addition, the presence of experts in their environments may have acted as a catalyst for their participation in educational programmes. Thus, the interplay between environmental factors and educational opportunities may have a notable influence on the quality of the evaluation and treatment of AA.

Next, results highlight the need for a comprehensive review of clinical nutrition education programmes in Japan. Although the MNA‐SF has emerged as the most widely used screening tool among individuals with educational opportunities, it primarily assesses nutritional status, with decreased food intake being the only assessment parameter. 14 The use of appetite‐specific tools such as the Functional Assessment of Anorexia and Cachexia Therapy (FAACT), 15 , 16 Council on Nutrition Appetite Questionnaire (CNAQ), 17 , 18 and Simplified Nutritional Appetite Questionnaire (SNAQ) 17 , 19 remained minimal among those with educational opportunities as well as among registered dietitians. In addition, even among those who received continuing education, approximately 30% did not incorporate evidence‐based tools or materials into the screening and treatment protocols for anorexia in older adults. More than half of the respondents acknowledged the paucity of high‐quality evidence on AA, indicating the critical need for further education in this area. While existing nutrition education programmes in Japan, such as TNT‐Geriatric 20 and TNT‐Rehabilitation, 21 and educational programmes of clinical nutrition‐related societies provide adequate content on nutritional status assessment and disease‐specific nutrition management, they offer relatively limited coverage on the assessment and treatment of anorexia. Because AA is due to a variety of factors, including age‐related changes in the gastrointestinal tract and sensory organs, as well as the influence of diseases and medications, 8 medical interventions for anorexia must adopt a comprehensive approach based on analytical, diagnostic reasoning, rather than simply attributing it to aging or relying solely on oral nutritional supplementation. 22 There is an urgent need to revise existing training programmes to incorporate the FAACT, CNAQ, SNAQ, and other tools specific to anorexia and appetite assessment. In addition, the curricula should be revised to equip health professionals with diagnostic reasoning‐based methodologies. Furthermore, educational programmes in geriatrics have been shown to benefit from multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary content, the incorporation of group learning, and the use of case studies. 23 Notably, evidence from a one‐day educational programme on frailty among primary care providers demonstrated sustained improvements in participants' perceptions of frailty and screening practices. 24 However, there is a lack of research evaluating the effectiveness of educational programmes focused on AA, which warrants further investigation.

The significance of this study lies in its use of a web‐based survey format, which facilitated responses not only from hospital staff but also from a wide range of healthcare professionals involved in caring for older patients in various settings, including nursing homes and home care. By juxtaposing knowledge and practices regarding AA with the availability of educational opportunities in nutrition management for patients, this study identified pertinent issues related to educational programmes in this area.

However, this study has several limitations. First, the survey respondents were primarily members of academic societies related to geriatrics, most of whom were healthcare professionals with some familiarity with the management of AA. Therefore, the results may not be fully representative of clinical practice. In addition, the response rate for the survey was moderate, with only 56.7% (893/1575) of all respondents providing complete responses without omissions, suggesting a potential bias in the dataset.

Conclusions

Healthcare professionals' participation in continuing education programmes on clinical nutrition is associated with their responsiveness in screening, diagnosing, and treating older adults with anorexia and the availability of expert teams, which may affect the quality of care for AA. Nutrition education may support the confidence of health care professionals working with older adults in AA with complex clinical signs and encourage them to conduct evidence‐based assessments.

Conflict of interest

MA received research funding from Eisai, Kracie Pharma, Mitsubishi‐Tanabe Pharma, and Tsumura and lecture fees from Bayer HealthCare, Daiichi Sankyo, Toa Eiyo, and Towa Pharmaceutical. IA has received consultancy fees from Pfizer. AC has received honoraria and/or lecture fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Menarini, Novartis, Servier, Vifor, Abbott, Actimed, Arena, Cardiac Dimensions, Corvia, CVRx, Enopace, ESN Cleer, Faraday, Impulse Dynamics, Respicardia, and Viatris. SDA has received grants and personal fees from Vifor and Abbott Vascular and personal fees for consultancies, trial committee work and/or lectures from Actimed, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, BioVentrix, Brahms, Cardiac Dimensions, Cardior, Cordio, CVRx, Cytokinetics, Edwards, Farraday Pharmaceuticals, GSK, HeartKinetics, Impulse Dynamics, Novartis, Occlutech, Pfizer, Repairon, Sensible Medical, Servier, Vectorious, and V‐Wave. He has been named co‐inventor of two patent applications regarding MR‐proANP (DE 102007010834 and DE 102007022367), but he does not benefit personally from the related issued patents. The rest of the authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Pfizer Inc. as an independent educational grant and the Research Funding of Longevity Sciences (grant number: 22‐4). The authors thank Dr. John E. Morley, Department of Medicine, Division of Geriatrics, Saint Louis University, and all respondents to this survey. The authors certify that they comply with the ethical guidelines for authorship and publishing of the Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle. 25

Takagi S., Satake S., Sugimoto K., Kuzuya M., Akishita M., Arai H., et al (2024) Survey on the knowledge and practices in anorexia of aging diagnosis and management in Japan, Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle, doi: 10.1002/jcsm.13566.

References

- 1. Donini LM, Dominguez LJ, Barbagallo M, Savina C, Castellaneta E, Cucinotta D, et al. Senile anorexia in different geriatric settings in Italy. J Nutr Health Aging 2011;15:775–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pilgrim AL, Baylis D, Jameson KA, Cooper C, Sayer AA, Robinson SM, et al. Measuring appetite with the simplified nutritional appetite questionnaire identifies hospitalised older people at risk of worse health outcomes. J Nutr Health Aging 2016;20:3–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Okamoto K, Harasawa Y, Shiraishi T, Sakuma K, Momose Y. Much communication with family and appetite among elderly persons in Japan. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2007;45:319–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tsutsumimoto K, Doi T, Nakakubo S, Kim M, Kurita S, Ishii H, et al. Association between anorexia of ageing and sarcopenia among Japanese older adults. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2020;11:1250–1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Landi F, Lattanzio F, Dell'Aquila G, Eusebi P, Gasperini B, Liperoti R, et al. Prevalence and potentially reversible factors associated with anorexia among older nursing home residents: results from the ULISSE project. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2013;14:119–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. de Souto BP, Cesari M, Morley JE, Roberts S, Landi F, Cederholm T, et al. Appetite loss and anorexia of aging in clinical care: an ICFSR task force report. J Frailty Aging 2022;11:129–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cox NJ. Consequences of anorexia of aging in hospital settings: an updated review. Clin Interv Aging 2024;19:451–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Merchant RA, Woo J, Morley JE. Editorial: anorexia of ageing: pathway to frailty and sarcopenia. J Nutr Health Aging 2022;26:3–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Morley JE. Anorexia of ageing: a key component in the pathogenesis of both sarcopenia and cachexia. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2017;8:523–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Morley JE, Silver AJ. Anorexia in the elderly. Neurobiol Aging 1988;9:9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wurtman JJ. The anorexia of aging: a problem not restricted to calorie intake. Neurobiol Aging 1988;9:22–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aprahamian I, Coats AJ, Morley JE, Klompenhouwer T, Anker SD, International Advisory Board, and Regional Advisory Boards for North America, Latin America, Europe and Japan . Anorexia of aging: an international assessment of healthcare providers' knowledge and practice gaps. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2023;14:2779–2792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy‐to‐use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant 2013;48:452–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kaiser MJ, Bauer JM, Ramsch C, Uter W, Guigoz Y, Cederholm T, et al. Validation of the Mini Nutritional Assessment short‐form (MNA‐SF): a practical tool for identification of nutritional status. J Nutr Health Aging 2009;13:782–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ribaudo JM, Cella D, Hahn EA, Lloyd SR, Tchekmedyian NS, von Roenn J, et al. Re‐validation and shortening of the functional assessment of anorexia/cachexia therapy (FAACT) questionnaire. Qual Life Res 2000;9:1137–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Blauwhoff‐Buskermolen S, Ruijgrok C, Ostelo RW, de Vet HCW, Verheul HMW, de van der Schueren MAE, et al. The assessment of anorexia in patients with cancer: cut‐off values for the FAACT‐A/CS and the VAS for appetite. Support Care Cancer 2016;24:661–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wilson M‐MG, Thomas DR, Rubenstein LZ, Chibnall JT, Anderson S, Baxi A, et al. Appetite assessment: simple appetite questionnaire predicts weight loss in community‐dwelling adults and nursing home residents. Am J Clin Nutr 2005;82:1074–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tokudome Y, Okumura K, Kumagai Y, Hirano H, Kim H, Morishita S, et al. Development of the Japanese version of the Council on Nutrition Appetite Questionnaire and its simplified versions, and evaluation of their reliability, validity, and reproducibility. J Epidemiol 2017;27:524–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nakatsu N, Sawa R, Misu S, Ueda Y, Ono R. Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the simplified nutritional appetite questionnaire in community‐dwelling older adults. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2015;15:1264–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Michel J‐P, Cha HB. Filling the geriatric education gap around the world. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2015;16:1010–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Inoue T, Iida Y, Takahashi K, Shirado K, Nagano F, Miyazaki S, et al. Nutrition and physical therapy: a position paper by the physical therapist section of the Japanese Association of Rehabilitation Nutrition (Secondary Publication). JMA J 2022;5:243–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wakabayashi H, Maeda K, Momosaki R, Kokura Y, Yoshimura Y, Fujiwara D, et al. Diagnostic reasoning in rehabilitation nutrition: position paper by the Japanese Association of Rehabilitation Nutrition (secondary publication). J Gen Fam Med 2022;23:205–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Warren N, Gordon E, Pearson E, Siskind D, Hilmer SN, Etherton‐Beer C, et al. A systematic review of frailty education programs for health care professionals. Australas J Ageing 2022;41:e310–e319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kotsani M, Avgerinou C, Haidich A‐B, Smyrnakis E, Soulis G, Papageorgiou DI, et al. Feasibility and impact of a short training course on frailty destined for primary health care professionals. Eur Geriatr Med 2021;12:333–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. von Haehling S, Coats AJS, Anker SD. Ethical guidelines for publishing in the Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle: update 2021. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2021;12:2259–2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]