Abstract

Physical training in heat or hypoxia can improve physical performance. The purpose of this parallel group study was to investigate the concurrent effect of training performed simultaneously in heat (31 °C) and hypoxia (FIO2 = 14.4%) on anaerobic capacity in young men. For the study, 80 non-trained men were recruited and divided into 5 groups (16 participants per group): control, non-training (CTRL); training in normoxia and thermoneutral conditions (NT: 21 °C, FIO2 = 20.95%); training in normoxia and heat (H: 31 °C, FIO2 = 20.95%); training in hypoxia and thermoneutral conditions (IHT: 21 °C, FIO2 = 14.4%), and training in hypoxia and heat (IHT + H: 31 °C, FIO2 = 14.4%). Before and after physical training, the participants performed the Wingate Test, in which peak power and mean power were measured. Physical training lasted 4 weeks and the participants exercised 3 times a week for 60 min, performing interval training. Only the IHT and IHT + H groups showed significant increases in absolute peak power (p < 0.001, ES = 0.36 and p = 0.02, ES = 0.26, respectively). There were no significant changes (p = 0.18) after training in mean power. Hypoxia appeared to be an environmental factor that significantly improved peak power, but not mean power. Heat, added to hypoxia, did not increase cycling anaerobic power. Also, training only in heat did not significantly affect anaerobic power. The inclusion of heat and/or hypoxia in training did not induce negative effects, i.e., a reduction in peak and mean power as measured in the Wingate Test.

Keywords: Training, Muscle power, Environment, Hypoxia, Heat, Normoxia, Wingate test

Subject terms: Physiology, Environmental sciences, Anatomy, Biomarkers, Health care, Health occupations, Medical research, Signs and symptoms

Introduction

Training in extreme environmental conditions (in hypoxia and heat) can be an additional factor in enhancing the effects of training performed in normoxia and thermoneutral conditions1. Such training can be used for two purposes: first, as preparation (adaptations) for competition in conditions different from the usual training being performed; second, as conditioning training to improve performance2. Hypoxia and heat stress are considered conditions that can significantly improve physical performance compared to the effects of the same training performed under thermoneutral and/or normoxic conditions3. From a sporting perspective, the physiological response to prolonged exposure to heat and/or hypoxia may be beneficial, both during passive exposure and during physical exercise under such environmental conditions, as the observed metabolic effects on such training promote improved physical capacity and performance.

Both hypoxic training and hypoxic exposure can improve the metabolic profile and increase exercise tolerance during both submaximal and maximal intensity exercise3. The effects of hypoxia on aerobic performance are fairly well described4, with improvements in aerobic capacity achieved, among other things, by increasing red blood cell count and blood oxygen capacity (due to increased erythropoietin production)4. Compared to the reported data on the effects of hypoxic training on aerobic capacity, the number of data presenting the effects of hypoxic training on anaerobic capacity is limited and such studies are relatively rare. Anaerobic capacity may be defined as the maximal amount of ATP formed by the anaerobic processes during a single bout of maximal exercise5. Anaerobic capacity (anaerobic power) is an important parameter for sports performance, not only for short high-intensity activities, but also for breakaway efforts and end spurts during endurance competitions6. Intermittent hypoxic training may enhance glycolytic enzyme activity7 and muscle buffering capacity8, which may promote improved anaerobic performance. However, the effectiveness of hypoxic training in improving anaerobic performance is inconclusive: after training in hypoxia, both improvements in exercise capacity based on anaerobic metabolism have been reported9,10,11,12,13, as well as no effect14,15.

Heat is also a strong stressor during exercise and induces adaptive changes other than hypoxia, which can potentially benefit muscle force production16 and thus muscle power. It has been suggested that prolonged exposure to heat stress (without exercise) may be effective in increasing muscle strength and inducing muscle hypertrophy17. However, the reported data are unclear: it has been indicated both, that heat stress was an effective way to prevent muscle atrophy18, and improved lower and upper body strength19, muscle volume and strength20 or was not effective in improving performance: it was reported that, supplemental heating of active muscle during and after each bout of resistance training showed no clear positive (or negative) effect on training-induced hypertrophy or function21.

Acclimation to one environmental stressor could enhance adaptation to various other environmental stressors22. This phenomenon is named cross-tolerance. Cross-adaptation (or cross-tolerance) has been observed between heat acclimation and hypoxia23. Heat acclimation may attenuate physiological stress at rest and during moderate-intensity exercise at altitude through adaptations associated with improved oxygen delivery to metabolically active tissues, likely as a consequence of increased plasma volume and decreased body temperature. At the cellular level, the responses of heat shock proteins to altitude are attenuated by prior heat intervention, suggesting that there has been an attenuation of the cellular stress response and thus a reduced disruption of homeostasis at altitude23.

Hypoxia and heat are stressors that induce different adaptive mechanisms and may ultimately be beneficial to the body1,24. For logistical or technical reasons, i.e., the impossibility of simultaneous exposure to hypoxia and heat24, the two environments have so far most often been combined by applying them one after the other (not simultaneously) - thus their cross-adaptation has been demonstrated1,23. Combining these two environments may be the most beneficial model for training using environmental conditions to improve performance25. Although these two environments are primarily used to improve aerobic capacity1, it has been indicated that training under these conditions may also be beneficial for improving anaerobic capacity4, although such studies are rare. Many sports require both good aerobic and anaerobic capacity. The provision of anaerobic energy is important in high-intensity exercise situations, such as sprinting, in which energy demands far exceed the rate that aerobic systems can provide. This situation is common in stop-and-go sports, where transitions from lower to higher energy needs are numerous, and providing both aerobic and anaerobic energy contributes to athletic success26. Thus, training in hypoxia and heat may prove to be a versatile training method that can improve both aerobic and anaerobic capacity.

The purpose of this study was to determine not only the effects of training in a hot environment or hypoxia on anaerobic capacity, but more importantly, to examine the effects of the simultaneous application of hypoxia and heat in training on anaerobic capacity in untrained men. We hypothesized that the concurrent use of hypoxia and heat in training would be the most effective method of improving anaerobic capacity. Physiological adaptation to heat and to hypoxia may enhance the effects of training under normoxia and thermoneutral conditions, resulting in greater improvements in anaerobic performance than usual training under thermoneutral and normoxia conditions.

Methods

Experimental design

The study involved 80 men, divided into 5 groups of 16 participants each, training in different environmental conditions. Men aged 19–30 years were recruited for the study. All participants completed the study. Only healthy men, not training and not exposed to hypoxia in the 6 months prior to the intervention were included in the study. Participants who were training, taking specialized diet and dietary supplements, experienced in hypoxic training and working/training in high temperatures, had medical contraindications to exercise, and had abnormal levels of red blood cells, hemoglobin, transferrin, iron and other blood morphological indices were excluded from the study. The study included: medical qualification, somatic measurements, diet analysis, physical activity assessment and anaerobic capacity measurement (Fig. 1). Somatic and anaerobic capacity measurements were taken twice under thermoneutral and normoxic conditions: 5–7 days before the start of training and 7–10 days after the end of training. The anaerobic capacity test was performed in normoxia. The exercise intervention lasted 4 weeks with training frequency of 3 times per week. A single training session lasted 60 min. Training loads were determined by the results of a graded test conducted in normoxia, performed by each participant prior to the intervention. Training sessions took place in a thermoclimatic hypoxia chamber (Hypoxico, Germany), which allows simultaneous modification (and control) of air composition (FIO2 ± 0.1%), temperature (± 0.5 °C) and humidity (± 1%). During the workout, the CO2 level (ppm) inside the chamber is also monitored This allowed the creation of a variety of environmental conditions in which participants trained:

Fig. 1.

Study flowchart.

Normoxia and thermoneutral conditions (NT): 21 °C, FIO2 = 20.95%, humidity 40%;

Normoxia and heat (H): 31 °C, FIO2 = 20.95%, humidity 40%;

Hypoxia and thermoneutral conditions (IHT): 21 °C, FIO2 = 14.4% (simulated altitude: 3000 m), humidity 40%;

Hypoxia and heat (IHT + H): 31 °C, FIO2 = 14.4% (simulated altitude: 3000 m), humidity 40%.

In addition, a 5th group (control group) was formed, with no exercise intervention, in which only an anaerobic capacity test was conducted 4 weeks apart. Participants were asked not to change their usual diet for the duration of the study, and not to undertake any additional physical activity. The study was approved by the Bioethical Commission of the Regional Medical Chamber in Krakow, Poland (opinion no. 47/KB/OIL/2022). The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent after being informed about the study protocol.

Participants

The study included 80 young men of approximately the same age, with no medical contraindications to exercise. They did not engage in competitive sports, but were physically active and performed efforts of varying intensity, form and duration. Detailed body composition, declared physical activity, characteristics of the participants’ diet, and results of graded test are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Age, caloric intake, percentage of proteins, carbohydrates and fat in diet and physical activity of participants.

| Variable | Condition | Mean ± SD | ANOVA | Post-hoc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f p ƞp2 | p | ||||

| Age (yrs) | ctrl | 22.88 ± 2.91 |

2.47 0.05 0.11 |

||

| NT | 20.50 ± 1.03 | ||||

| H | 22.47 ± 3.67 | ||||

| IHT | 21.50 ± 1.55 | ||||

| IHT + H | 22.13 ± 1.57 | ||||

|

Caloric intake (kcal/week) |

ctrl | 21,291 ± 2434 |

0.78 0.54 0.04 |

||

| NT | 21,233 ± 3352 | ||||

| H | 19,749 ± 2108 | ||||

| IHT | 20,707 ± 3656 | ||||

| IHT + H | 20,738 ± 2438 | ||||

|

Proteins (%) |

ctrl | 20.71 ± 4.17 |

1.48 0.21 0.07 |

||

| NT | 19.06 ± 1.03 | ||||

| H | 18.06 ± 1.39 | ||||

| IHT | 19.25 ± 3.56 | ||||

| IHT + H | 19.44 ± 3.27 | ||||

|

Carbohydrates (%) |

ctrl | 46.18 ± 5.27 |

0.77 0.55 0.03 |

||

| NT | 45.81 ± 5.28 | ||||

| H | 45.29 ± 3.46 | ||||

| IHT | 48.00 ± 6.48 | ||||

| IHT + H | 45.44 ± 4.09 | ||||

|

Fat (%) |

ctrl | 34.24 ± 4.50 |

1.15 0.24 0.06 |

||

| NT | 34.94 ± 4.02 | ||||

| H | 36.06 ± 2.46 | ||||

| IHT | 32.94 ± 4.68 | ||||

| IHT + H | 34.44 ± 5.34 | ||||

| METs-min/week | ctrl | 6582 ± 2831 |

1.96 0.10 0.09 |

||

| NT | 6154 ± 2509 | ||||

| H | 4936 ± 2068 | ||||

| IHT | 6376 ± 1881 | ||||

| IHT + H | 6944 ± 1580 | ||||

| VO2max (L/min) | ctrl | 3.34 ± 0.43 |

3.93 0.005 0.17 |

IHT vs. HT: p = 0.006 NT vs. HT: p = 0.01 |

|

| NT | 3.55 ± 0.37 | ||||

| H | 3.02 ± 0.43 | ||||

| IHT | 3.59 ± 0.53 | ||||

| IHT + H | 3.41 ± 0.55 | ||||

| HRmax (bpm) | ctrl | 183 ± 11.9 |

1.05 0.38 0.05 |

||

| NT | 184 ± 10.8 | ||||

| H | 187 ± 10.8 | ||||

| IHT | 181 ± 7.4 | ||||

| IHT + H | 186 ± 5.7 | ||||

| MWL (W) | ctrl | 273.2 ± 39.6 |

0.91 0.43 0.04 |

||

| NT | 285.3 ± 33.1 | ||||

| H | 266.9 ± 50.8 | ||||

| IHT | 286.0 ± 41.5 | ||||

| IHT + H | 291.1 ± 45.6 | ||||

ctrl: control group; NT: training in normoxia and thermoneutral condition; IHT: intermittent hypoxia training; H: training in heat and normoxia; IHT + H: intermittent hypoxia training and heat; MET: metabolic equivalent of task; VO2max: absolute maximal oxygen uptake noted in graded test; HRmax: maximal heart rate; MWL: maximal workload in graded test;.

Table 2.

Somatic build of participants.

| Variable | Condition | Baseline | Post | ANOVA | Post-hoc | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect: Group f p ƞp2 |

Effect: Time f p ƞp2 |

Interaction f p ƞp2 |

Baseline vs. Post p |

||||

|

BH (cm) |

ctrl | 178.9 ± 5.9 | - | - | - | - | - |

| NT | 179.7 ± 5.6 | - | - | ||||

| H | 177.0 ± 5.8 | - | - | ||||

| IHT | 182.0 ± 5.5 | - | - | ||||

| IHT + H | 179.1 ± 5.7 | - | - | ||||

|

BM (kg) |

ctrl | 75.8 ± 11.5 | 75.9 ± 11.7 |

0.57 0.67 0.03 |

0.27 0.60 0.003 |

0.39 0.80 0.02 |

- |

| NT | 76.7 ± 8.3 | 76.9 ± 8.2 | - | ||||

| H | 74.2 ± 12.1 | 74.1 ± 13.1 | - | ||||

| IHT | 79.6 ± 10.4 | 79.2 ± 9.6 | - | ||||

| IHT + H | 76.8 ± 7.3 | 76.7 ± 7.3 | - | ||||

|

BF (%) |

ctrl | 18.3 ± 5.3 | 18.0 ± 5.0 |

0.25 0.90 0.01 |

6.09 0.02 0.07 |

1.87 0.12 0.08 |

0.97 |

| NT | 17.6 ± 3.9 | 17.7 ± 4.4 | 0.99 | ||||

| H | 18.4 ± 6.8 | 18.4 ± 7.0 | 1.00 | ||||

| IHT | 17.4 ± 3.9 | 16.3 ± 3.8 | 0.13 | ||||

| IHT + H | 18.5 ± 3.4 | 17.8 ± 3.8 | 0.59 | ||||

|

BMI (kg/m2) |

ctrl | 23.6 ± 2.9 | 23.7 ± 2.9 |

0.07 0.99 0.003 |

0.17 0.68 0.002 |

0.23 0.91 0.01 |

- |

| NT | 23.7 ± 2.2 | 23.8 ± 2.2 | - | ||||

| H | 23.5 ± 3.2 | 23.6 ± 3.6 | - | ||||

| IHT | 24.0 ± 2.3 | 23.9 ± 2.1 | - | ||||

| IHT + H | 23.9 ± 1.6 | 23.9 ± 1.7 | - |

ctrl: control group; NT: training in normoxia and thermoneutral condition; IHT: intermittent hypoxia training; H: training in heat and normoxia; IHT + H: intermittent hypoxia training and heat; BH: body height; BM: body mass; BF: body fat; BMI: body mass index.

Somatic measurements

Before and after the exercise intervention, body mass (BM) and body composition (body fat (%BF)) were measured using bioelectrical impedance (Jawon Medical, IOI-353, Korea). Body composition was measured in the morning, while the participant was fasting. The participant’s feet and hands, as well as the electrodes (8 electrodes on the upper and lower extremities), were degreased before measurement. The measurement was performed only in underwear. The accuracy of the measurement was 0.1 kg (BM) and 0.1% BF. Body height (BH) was measured with a stadiometer (Seca 217, Germany) with an accuracy of 0.1 cm.

Declared physical activity

During recruitment, the subjects completed an International Physical Activity Questionnaire in the Polish version27,28. A researcher was present when the questionnaire was completed and instructed each participant on how to complete the questionnaire. Activity volume was calculated based on its energy requirements, defined as a multiple of resting metabolic rate (MET), and expressed in MET-minutes per week. MET-minutes were calculated by multiplying the MET score of an activity by the number of minutes performed.

Diet

Prior to the start of the exercise intervention, participants completed food diaries for 7 days using the Fitatu (Poland) application29. The men were instructed on how to use the application and were required to enter the name of each food they consumed into the application, including weight or volume. Based on the data entered, the weekly caloric content of the diet (kcal/week) and the percentage of protein, carbohydrate and fat in the diet were determined.

Exercise tests

The participants performed two exercise tests, usually day after day. In the pre-test, in two cases the tests were performed within three days. The results of the first test, i.e., the graded test, were used to determine training loads corresponding to the first (VT1) and second (VT2) ventilatory thresholds, determined individually for each participant. The second test, the Wingate Test30, was used to assess anaerobic capacity, i.e. primarily to determine anaerobic peak power and average power. Due to the presence of a practice effect in the Wingate test31 a familiarization session was scheduled. In familiarization session participants performed a trial supramaximal anaerobic all-out test. Participants were instructed not to participate in any exercises 24 h before the exercise test. No alcohol or caffeinated drinks were allowed for at least 24 h before the tests. Men had to proceed the tests properly hydrated about 2 h after a light meal.

The graded test was performed on a bicycle ergometer (eBike Comfort, GE Health Care, USA) and consisted of a 4-minute warm-up with a load of 60 Watts and progressive exercise (ramp protocol) during which the load increased at a rate of 15 Watts/min until volitional exhaustion. The metabolic cart (MetaLyzer 3R, Cortex, Germany) measured the following metrics using a breath-by-breath method: oxygen uptake (VO2), carbon dioxide output (VCO2), pulmonary ventilation (VE), respiratory exchange ratio (RER), fractional concentrations of expired CO2 (%FECO2) and O2 (%FEO2), ventilatory equivalent ratio for oxygen (VE/VO2) and carbon dioxide (VE/VCO2). The ventilatory thresholds were determined using the method of respiratory equivalents32,33. The VT1 was detected by the power output at which the VE/VO2 ratio and FEO2 reached a minimum. The VT2 was determined at workload at which the VE/VCO2 ratio reached a minimum and the FECO2 reached a maximum.

The Wingate test was preceded by a 5-minute warm-up with a load of 90 watts on a cycloergometer (Monark E834, Sweden) during which the participant performed (in the second and fifth minute) two maximal accelerations lasting about 5 seconds. After the warm-up, there was a 5-minute rest break before the main test. The test had a stationary start34 and lasted 30 seconds, with a load of 7.5% of body mass. At a signal, the participant began an ‘all-out’ effort during which he or she was expected to pedal as fast as possible for the duration of the test. During the test, the participant was verbally motivated loudly. The following variables were measured in the test: peak power (PP), mean power (MP), time to reach peak power (TTR-PP), peak power maintenance time (MT-PP) i.e., the duration for which peak power was maintained after it was reached, fatigue index (FI) expressed as % difference between peak power and power at the end of the test, power decrease (PD) showing the rate of power decline with time (W/s), and total work (TW). MCE 5.1 software (JBA Staniak, Poland) was used to calculate the variables.

Training

Under all conditions, participants performed the same training. The training sessions were performed between 8 a.m. and 2 p.m. A single workout lasted 60 min and was interval in design. The main part of the workout lasted 54 min. The workout began with a 6-minute warm-up with power at VT1 and then the participants performed 6 series of interval efforts in a pattern: 6 min of effort with power at VT2 and 3 min of active recovery with power at VT1. Power at VT1 and at VT2 was individually determined by the results of a graded test performed in normoxia. For 4 weeks of training, the loads were not changed. The training was performed on Wattbike (UK) cycloergometers. During the workout, heart rate was measured (Polar H10, Finland) continuously and at the end of the workout, during the last interval (55 min), participants subjectively indicated the rate of perceived exertion (RPE) using the Borg scale35. Training characteristics (loads, heart rate, intensity) are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Training characteristics (data recorded during the first training session).

| Variable | Condition | Mean ± SD | ANOVA | Post -hoc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f p ƞp2 | p | ||||

| Pex (W) | NT | 162.5 ± 21.1 |

5.07 0.003 0.19 |

IHT vs. HT: 0.001 | |

| H | 145.5 ± 30.4 | ||||

| IHT | 183.8 ± 29.3 | ||||

| IHT + H | 164.1 ± 30.7 | ||||

| Prec (W) | NT | 70.8 ± 17.6 |

2.89 0.04 0.12 |

IHT vs. NT: 0.04 | |

| H | 74.9 ± 16.5 | ||||

| IHT | 90.5 ± 22.8 | ||||

| IHT + H | 81.8 ± 23.7 | ||||

| HR (bpm) | NT | 147 ± 15.0 |

9.71 < 0.001 0.32 |

IHT vs. HT: 0.004 IHT vs. IHT + H: 0.003 NT vs. H: <0.001 NT vs. IHT + H: <0.001 |

|

| H | 164 ± 9.5 | ||||

| IHT | 183.8 ± 29.2 | ||||

| IHT + H | 164.1 ± 30.7 | ||||

| %HRmax | NT | 79.7 ± 7.8 |

6.68 < 0.001 0.25 |

NT vs. H: 0.003 NT vs. IHT + H: 0.003 |

|

| H | 87.9 ± 5.1 | ||||

| IHT | 82.2 ± 7.6 | ||||

| IHT + H | 88.2 ± 5.3 | ||||

| Borg (RPE) | NT | 12.3 ± 1.30 |

2.26 0.08 0.10 |

||

| H | 14.0 ± 2.37 | ||||

| IHT | 13.6 ± 2.3 | ||||

| IHT + H | 13.9 ± 2.2 | ||||

Pex: power during exercise; Prec: power during active recovery in interval training; HR: heart rate; RPE: rate of perceived exertion (Borg scale).

Statistical analysis

Before the study sample size was calculated (G*Power 3.1.9.7, Germany). The following data were entered into the software: test family = f tests; statistical test = ANOVA repeated measures, within-between interaction; type of power analysis = compute required sample size - given α, power, and effect size. Input parameters into the software were as follows: effect size f: 0.25; α error probability: 0.05; power: 0.95; number of groups: 5; number of measurements: 2; correlation among measures: 0.5; nonsphericity correction: 1.0). The required total sample size was 80 participants (16 men per group).

Data were presented as mean and standard deviation. Before performing analysis of variance (ANOVA), assumptions of variance were checked: homogeneity of variance was checked with Levene’s test and data distribution was checked with Shapiro-Wilk test. ANOVA with repeated measures was used to detect the differences between groups, differences between baseline and post measurements (change in time) and to assess the effect size (partial eta squared (ƞp2)). The following main effects were analyzed: group, time (baseline vs. post) and the interaction between these two main factors. One-way ANOVA was used to determine differences in physical activity levels, dietary calories and data from graded test. The effect size (ƞp2) was interpreted as small (0.01), medium (0.06), or large (0.14)36. If the ANOVA results were significant, the Tukey test was used for post-hoc analysis. In addition, if the results of the post hoc analysis were significant, a Cohen’s d (effect size: ES) was additionally determined between baseline and post training data. The ES was interpreted as small (0.20), medium (0.50), or large (0.80)36. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using STATISTICA 13 (StatSoft, Inc., USA).

Results

Men from all groups reported similar habitual physical activity (f = 1.96, p = 0.10) (Table 1). There were also no significant between-group differences in dietary calories (f = 0.78, p = 0.54) and percentages of dietary fat (f = 1.15, p = 0.24), carbohydrates (f = 0.77, p-0.55) and protein (f = 1.48, p = 0.21) (Table 1). The study groups also did not differ in body mass (f = 0.57, p = 0.67) or body composition (Table 2). The applied training did not cause significant changes in body mass (f = 0.27, p = 0.60) and body composition (Table 2).

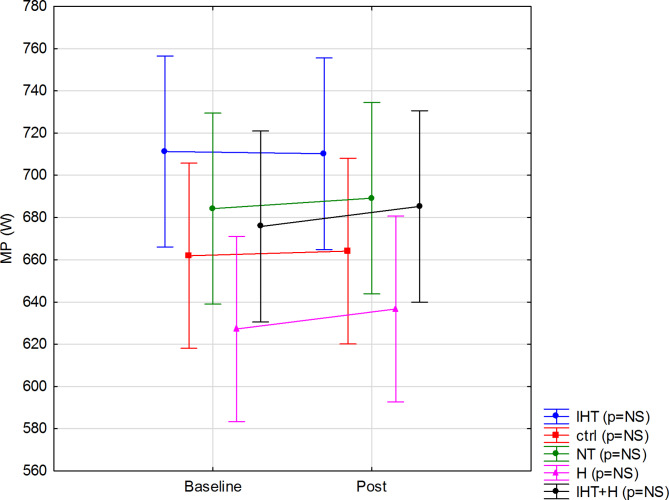

Only IHT and IHT + H groups significantly improved absolute PP (p < 0.001, ES = 0.36 and p = 0.02, ES = 0.26, respectively; Table 4; Fig. 2). A similar effect was noted for relative PP (Table 4). The mean power did not change after training in either group (Fig. 3). The remaining variables did not change significantly under training in any environmental conditions (Table 4). Only in the control group was there a significant (p = 0.02, ES = 0.81) reduction in power maintenance time.

Table 4.

Effects of different environmental conditions on variables measured in Wingate Test.

| Variable | Condition | Baseline | Post | ANOVA | post-hoc | ES | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect: Group f p ƞp2 |

Effect: Time f p ƞp2 |

Interaction f p ƞp2 |

Baseline vs. Post p |

Baseline vs. Post | ||||

| TW (kJ) | ctrl | 19.85 ± 2.90 | 19.92 ± 2.97 |

1.76 0.14 0.08 |

1.40 0.24 0.02 |

0.23 0.91 0.01 |

- | - |

| NT | 20.52 ± 2.21 | 20.67 ± 2.58 | - | - | ||||

| H | 18.82 ± 2.55 | 18.94 ± 2.52 | - | - | ||||

| IHT | 21.33 ± 3.14 | 21.30 ± 2.84 | - | - | ||||

| IHT + H | 20.27 ± 2.79 | 20.47 ± 2.68 | - | - | ||||

| PP (W) | ctrl | 867.4 ± 153.2 | 882.9 ± 150.4 |

0.65 0.17 0.08 |

37.9 < 0.001 0.32 |

2.71 0.03 0.12 |

0.66 | - |

| NT | 889.9 ± 119.5 | 909.9 ± 107.4 | 0.35 | - | ||||

| H | 816.7 ± 125.6 | 821.9 ± 116.4 | 0.99 | - | ||||

| IHT | 889.3 ± 120.1 | 934.4 ± 130.2 | < 0.001 | 0.36 | ||||

| IHT + H | 906.4 ± 115.3 | 936.4 ± 119.9 | 0.02 | 0.26 | ||||

| PP (W/kg) | ctrl | 11.44 ± 1.02 | 11.64 ± 1.00 |

1.46 0.22 0.07 |

33.78 < 0.001 0.30 |

2.23 0.07 0.10 |

0.78 | - |

| NT | 11.62 ± 1.00 | 11.88 ± 1.18 | 0.48 | - | ||||

| H | 11.30 ± 1.24 | 11.42 ± 1.09 | 0.99 | - | ||||

| IHT | 11.19 ± 0.92 | 11.77 ± 0.86 | < 0.001 | 0.65 | ||||

| IHT + H | 11.81 ± 0.93 | 12.21 ± 0.80 | 0.04 | 0.46 | ||||

| MP (W) | ctrl | 661.9 ± 96.9 | 664.1 ± 99.2 |

1.78 0.14 0.08 |

1.81 0.18 0.02 |

0.30 0.87 0.01 |

- | - |

| NT | 684.2 ± 73.9 | 589.1 ± 86.2 | - | - | ||||

| H | 627.6 ± 85.0 | 631.5 ± 84.3 | - | - | ||||

| IHT | 711.3 ± 104.7 | 710.2 ± 94.7 | - | - | ||||

| IHT + H | 675.7 ± 93.2 | 685.3 ± 89.9 | - | - | ||||

| MP (W/kg) | ctrl | 8.77 ± 0.77 | 8.78 ± 0.74 |

0.49 0.73 0.03 |

2.59 0.11 0.03 |

0.22 0.92 0.01 |

- | - |

| NT | 8.95 ± 0.72 | 9.00 ± 1.01 | - | - | ||||

| H | 8.73 ± 1.05 | 8.79 ± 0.90 | - | - | ||||

| IHT | 8.93 ± 0.69 | 8.98 ± 0.67 | - | - | ||||

| IHT_H | 8.80 ± 0.78 | 8.94 ± 0.77 | - | - | ||||

| PD (W/s) | ctrl | 16.65 ± 4.39 | 18.35 ± 4.64 |

1.08 0.37 0.05 |

39.99 0.002 0.11 |

1.39 0.24 0.07 |

0.29 | - |

| NT | 16.63 ± 4.00 | 17.88 ± 1.92 | 0.74 | - | ||||

| H | 15.87 ± 5.03 | 15.61 ± 3.53 | 0.99 | - | ||||

| IHT | 16.03 ± 2.92 | 17.78 ± 3.51 | 0.29 | - | ||||

| IHT + H | 17.77 ± 2.82 | 17.73 ± 3.38 | 1.0 | - | ||||

| FI (%) | ctrl | 24.4 ± 5.65 | 27.4 ± 5.82 |

0.55 0.69 0.03 |

3.07 0.08 0.04 |

2.12 0.08 0.09 |

- | - |

| NT | 24.5 ± 5.16 | 25.4 ± 3.87 | - | - | ||||

| H | 24.83 ± 5.64 | 24.4 ± 2.56 | - | - | ||||

| IHT | 23.8 ± 4.63 | 25.2 ± 4.06 | - | - | ||||

| H | 26.5 ± 5.00 | 26.3 ± 5.21 | - | - | ||||

| MT-PP (s) | ctrl | 4.46 ± 1.47 | 3.46 ± 1.01 |

1.73 0.15 0.08 |

5.99 0.02 0.07 |

3.36 0.01 0.15 |

0.02 | 0.81 |

| NT | 3.79 ± 1.07 | 3.58 ± 0.54 | 0.99 | - | ||||

| H | 3.73 ± 0.79 | 3.66 ± 0.79 | 1.00 | - | ||||

| IHT | 4.65 ± 1.28 | 4.01 ± 0.90 | 0.42 | - | ||||

| IHT + H | 3.54 ± 0.86 | 3.83 ± 1.30 | 0.99 | - | ||||

| TTR-PP (s) | ctrl | 5.79 ± 1.25 | 5.24 ± 0.82 |

2.64 0.04 0.12 |

15.23 < 0.001 0.17 |

0.49 0.73 0.03 |

0.19 | - |

| NT | 6.12 ± 1.28 | 5.82 ± 1.42 | 0.91 | - | ||||

| H | 5.64 ± 1.13 | 5.37 ± 1.16 | 0.98 | - | ||||

| IHT | 5.42 ± 0.74 | 4.94 ± 0.61 | 0.40 | - | ||||

| IHT + H | 5.12 ± 0.77 | 4.85 ± 0.62 | 0.96 | - |

ctrl: control group; NT: training in normoxia and thermoneutral condition; IHT: intermittent hypoxia training; H: training in heat and normoxia; IHT + H: intermittent hypoxia training and heat; TW: total work; PP: peak power; MP: mean power; PP and MP in W/kg: relative peak power and relative mean power, respectively; PD: power decrease; FI: fatigue index; MT-PP: peak power maintenance time; TTR-PP: time to reach peak power.

Fig. 2.

Effects of physical training in various environmental conditions on absolute peak anaerobic power (IHT: hypoxia; ctrl control; NT: normoxia-thermoneutral; H: normoxia-heat; IHT + H: hypoxia-heat; vertical bars indicate 0.95 confidence interval; *p < 0.05 pre- vs. post measurement in group).

Fig. 3.

Effects of physical training in various environmental conditions on absolute mean anaerobic power (IHT: hypoxia; ctrl control; NT: normoxia-thermoneutral; H: normoxia-heat; IHT + H: hypoxia-heat; vertical bars indicate 0.95 confidence interval).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the effects of the same physical training performed under different environmental conditions on anaerobic power. The study was designed as a parallel study in which groups trained under normoxia, hypoxia, heat or a combination of these conditions. Our results indicate, that when performing the same training under different environmental conditions (heat, hypoxia), only training under hypoxic conditions induced an increase in peak power. In contrast, training under these environmental conditions did not improve mean power.

Previously reported data suggest, that hypoxic training may be effective in improving anaerobic capacity12,37. Exercise under hypoxic conditions, increases anaerobic ATP production, causing lactate and hydrogen ions to accumulate in the blood38. This results in additional recruitment of motor units to maintain mechanical power3, as confirmed using surface electromyography39, during both resistance40, and endurance exercise41. Early fatigue of type I oxidative fibers due to hypoxia is considered to require recruitment of type II fibers13. Increased workload on type II fibers can lead to improvements in muscular performance13. Power output is a product of strength and speed, so changes in it can result from changes in these two components. Only a few papers have indicated that hypoxic training can improve anaerobic performance: increases in strength13, jump performance10 or anaerobic power9,11 have been reported after hypoxic training. The lack of effect of hypoxic training on anaerobic capacity has also been reported14,15.

Exposure to heat stress alone can be effective in increasing strength and muscle mass17. This is associated with increased/decreased transcription of heat stress-induced genes. It was shown that the transcript level of ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase binding protein (UQCRB) increased threefold under heat stress. UQCRB is thought to be one of the oxidative phosphorylation-associated genes, suggesting that exposure to heat can stimulate ATP synthesis17. However, these changes were observed with a longer (10 weeks) exposure to heat than in our study (4 weeks). Other suggested adaptive mechanisms induced by training in hot conditions that could potentially improve anaerobic capacity are upregulated anabolic hormonal responses18,19 or upregulated pathways facilitating protein synthesis21. These training-induced changes were noted after resistance training, while there is no confirmation of these data in other types of training performed in the heat, including interval training (as in this study).

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the simultaneous effects of heat and hypoxia on cycling peak and mean anaerobic power. Previous similar studies have focused on the effects of combinations of these two environments on endurance performance42 or assessed the physiological response43,44 to training in such an environment. The simultaneous use of hypoxia and heat in training was not shown to be more effective in improving endurance performance than hypoxia alone or heat alone42,45,46. It was also shown that the combined stimuli (hypoxia + heat) did not provide additional physiological benefits in heat adaptation during exercise in a hot environment43. The combined stresses of heat and hypoxia during endurance exercise caused modifications in metabolic and hormonal regulation compared to the same exercise under hypoxic conditions: when heat exposure was combined during endurance exercise under hypoxic conditions, the exercise-induced increase in growth hormone was significantly increased47, and growth hormone can enhance the anaerobic capacity48. The only previous study focusing on changes in anaerobic metabolism under simultaneous hypoxia and heat evaluated only the acute effects of such stimulation - additional heat stress when sprinting repeatedly in hypoxia improved repeated sprint performance49. A similar effect was also noted after acute heat exposure - muscle strength in the vertical jump increased significantly50. These changes suggest that exogenous heat was more a form of warm-up and therefore improved muscle power51.

Previous studies have shown that hypoxia-only training11,37 and heat-only training18,19,20 can be beneficial in improving exercise capacity based on anaerobic metabolism (strength, power, jump performance). Our particular interest was to investigate whether the simultaneous effects of hypoxia and heat could be the combination that would most strongly improve anaerobic power. Thus, we hypothesized that training under combined conditions of heat and hypoxia would be more effective than training only in hypoxia or only in heat. The results of our study, however, do not support our hypothesis. We noted a significant improvement only in peak power (no significant improvement in mean power), only after training taking place in hypoxia (IHT and IHT + H). However, we did not find an improvement in mean power - this suggests that the potential mechanisms that improve the glycolytic pathway did not improve under hypoxia, and only those, that could potentially affect the phosphagen pathway and enhance peak power improved. However, this requires further research and confirmation. Training in heat, as in normoxia and thermoneutral conditions, did not significantly affect the level of any variable characterizing anaerobic performance. Thus, we partially confirmed the results of previous studies9,11,37, which showed, that hypoxia can improve anaerobic power. At the same time, we did not confirm previously reported data that training in heat18,19, or even passive heat exposure17, can contribute to improving anaerobic power.

Limitations on the study.

The environments (hypoxia and heat) in which the training was performed are an additional load, and thus affect the intensity of the training performed. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of the same training, but performed under different environmental conditions. One of the effects of training in extreme environments is the change in exercise intensity at a given load. In this study, while training in different environmental conditions, we did not adjust the workloads to each environmental condition and they were determined by a graded test performed in normoxia. Nevertheless, the intensity of exercise (%HRmax) performed under different environmental conditions varied - especially was higher during the intervention with heat. Heat significantly increases hear rate which makes it difficult to assess real work intensity expressed as %HRmax.

Another issue is the environmental conditions in which the training took place - in our study it was: FIO2 = 14.4%, humidity = 40% and 31 °C. Different conditions can produce different effects on anaerobic capacity. For this reason, the results of our study are limited only to the training protocol used and the environmental characteristics used in training and to untrained men. Training men and athletes were excluded from our study. This was primarily for methodological reasons. Training men/athletes perform a variety of training and by participating in our study they would have had to resign from routine training and could not perform any other training during the intervention. Our study was one of the first of its kind and we depended on a strong methodology with control for confounding variables. Previous research on the effect of environment on performance indicates that the greater observable effect of such training is in untrained individuals. The physiological response to training in heat and hypoxia in elite athletes is less clear52. However, verifying the effectiveness of training in hypoxia/heat in athletes, can have great practical application and be of great importance in their maximization of exercise capacity.

The training protocol in this study was of submaximal intensity. Perhaps maximal or supramaximal intensity training in hypoxia52,53 (such as sprint interval training) would be more targeted to improve anaerobic capacity, although the data reported so far are also inconclusive: both indicate that such training is similarly effective in hypoxia and normoxia54,55 and more effective than training in normoxia56.

In this study, performance improvement was measured 7–10 days after the training. Hendriksen and Meeuwsen57 reported, that performance during a single Wingate effort improved when assessed 9 days but not 2 days after the hypoxic training and 7–9 days allow sufficient recovery from the intervention to measure positive effects54.

The METs-min/week of the H group was lower (not significantly) compared to the other groups. In our opinion, this difference did not affect the results of the study. Declared physical activity presents the physical activity of the participants before the intervention. During the intervention, the participants participated only in our training sessions. Our study focuses primarily on assessing changes in the indicators studied in a given group under the influence of a given environment.

In this study, we focused on the effects of training simultaneously in heat and hypoxia, while we did not investigate the mechanisms underlying the observed changes. In our opinion, the study of these mechanisms should be the subject of future research. Future studies should focus on the chronic effects of training in heat and/or hypoxia and its effect on adaptive (physiological/biochemical/molecular) changes occurring in muscle (including energetics) and, in the case of hypoxia, on its non-hematological effects, that could potentially affect strength, power or shortening rate of muscle fibers. An exemplary line of inquiry might be to study the effects of heat-based interventions alone or in combination with exercise on basal signaling and applied physiological outcomes associated with hypertrophy, and the role of heat shock proteins (HSPs) in these mechanisms. HSPs may participate in intracellular signaling pathways that provide hypertrophic benefits58. Future inestigations should also consider increasing the duration of training and the frequency of exposure to hypoxia and heat. In our study, it was 12 training sessions in heat and hypoxia over 4 weeks, and this allowed us to observe the reported effects.

Strengths of the study.

The unquestionable strength of this study is the use of a hypoxic thermoclimatic chamber, in which it is possible to create different environmental conditions simultaneously. In our study, these were hypoxia and heat and constant humidity. Studies in which two (or more) environmental stressors are simultaneously interacted with are rare; in the absence of the technical feasibility of applying two stressors simultaneously, it is necessary to apply the two stressors one after the other. Our study therefore allowed us to assess the synergistic effect of hypoxia and heat on anaerobic capacity.

Conclusions

Compared to training in normoxia, physical training in hypoxia was effective in improving peak power, but did not significantly affect mean power in the Wingate test. Heat, added to hypoxia, did not increase the effect observed in hypoxia. Also, training only in heat did not affect anaerobic power. The inclusion of heat and/or hypoxia in training did not produce negative effects, i.e., a reduction in peak and mean power as measured by the Wingate Test.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, M.M., T.P.; methodology, M.M., T.P., M.W.; validation, M.M., T.P; formal analysis, M.M.; investigation, M.M., T.P., Z.S.; data curation, M.M., T.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M.; writing—review and editing, T.P., M.W., Z.S.; project administration, M.M. All authors have reviewed and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study and APC was funded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education (Poland), grant number: MEIN 2021/DPI/229.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declaration

The study was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Bioethical Commission of the Regional Medical Chamber in Kraków, Poland (opinion No. 47/KB/OIL/2022; date 11 April 2022). All participants were informed about the study protocol, voluntarily took part in the experiment and signed informed consent.

Footnotes

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article, all the authors were incorrectly affiliated with ‘Department of Clinical Rehabilitation, University of Physical Education, Krakow, Poland'. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction for this Article.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

11/11/2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41598-024-79007-9

References

- 1.Sotiridis, A., Debevec, T., Geladas, N., & Mekjavic, I. B. Cross-adaptation between heat and hypoxia: mechanistic insights into aerobic exercise performance. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol.323(5), R661–R669. 10.1152/ajpregu.00339.2021 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Wilber, R. L. Practical application of altitude/hypoxic training for Olympic medal performance: the team USA experience. J. Sci. Sport Exerc.4(4), 358–370. 10.1007/s42978-022-00168-y (2022).

- 3.Burtscher, J. et al. Mechanisms underlying the health benefits of intermittent hypoxia conditioning. J. Physiol.10.1113/JP285230 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Girard, O., Brocherie, F., & Millet, G. P. Effects of altitude/hypoxia on single-and multiple-sprint performance: a comprehensive review. Sports Med.47, 1931–1949. 10.1007/s40279-017-0733-z (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Gastin, P. B. Quantification of anaerobic capacity. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports4(2), 91–112. 10.1111/j.1600-0838.1994.tb00411.x (1994).

- 6.Noordhof, D. A., Skiba, P. F., & de Koning, J. J. Determining anaerobic capacity in sporting activities. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform.8(5), 475–482. 10.1123/ijspp.8.5.475 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Katayama, K. et al. Effect of intermittent hypoxia on oxygen uptake during submaximal exercise in endurance athletes. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 92, 75–83. 10.1007/s00421-004-1054-0 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Gore, C. J. et al. Live high:train low increases muscle buffer capacity and submaximal cycling efficiency. Acta Physiol. Scand.173(3), 275–286. 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2001.00906.x (2001). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Ambroży, T. et al. The effects of intermittent hypoxic training on anaerobic and aerobic power in boxers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health17, 9361. 10.3390/ijerph17249361 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Coşkun, B., Aras, D., Akalan, C., Kocak, S., & Hamlin, M. J. Plyometric Training in normobaric hypoxia improves jump performance. Int. J. Sports Med.43, 519–525. 10.1055/a-1656-9677 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Czuba, M. et al. Intermittent hypoxic training improves anaerobic performance in competitive swimmers when implemented into a direct competition mesocycle. PLoS One12(8), e0180380. 10.1371/journal.pone.0180380 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Hamlin, M. J., Marshall, H. C., Hellemans, J., Ainslie, P. N., & Anglem, N. Effect of intermittent hypoxic training on 20 km time trial and 30 s anaerobic performance. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports20(4), 651–661. 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.00946.x (2010). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Manimmanakorn, A. et al. Effects of resistance training combined with vascular occlusion or hypoxia on neuromuscular function in athletes. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol.113, 1767–1774. 10.1007/s00421-013-2605-z (2013). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Millet, G. et al. Effects of intermittent training on anaerobic performance and MCT transporters in athletes. PloS one9(5), e95092. 10.1371/journal.pone.0095092 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Morton, J. P., & Cable, N. T. The effects of intermittent hypoxic training on aerobic and anaerobic performance. Ergonomics48(11–14), 1535–1546. 10.1080/00140130500100959 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Périard, J. D., Racinais, S., & Sawka, M. N. Adaptations and mechanisms of human heat acclimation: applications for competitive athletes and sports. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports25, 20–38. 10.1111/sms.12408 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Goto, K. et al. Responses of muscle mass, strength and gene transcripts to long-term heat stress in healthy human subjects. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol.111, 17–27. 10.1007/s00421-010-1617-1 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Yoon, S. J., Lee, M. J., Lee, H. M., & Lee, J. S. Effect of low-intensity resistance training with heat stress on the HSP72, anabolic hormones, muscle size, and strength in elderly women. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 29, 977–984. 10.1007/s40520-016-0685-4 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Miles, C. et al. Resistance training in the heat improves strength in professional rugby athletes. Sci. Med. Footb.3(3), 198–204. 10.1080/24733938.2019.1566764 (2019).

- 20.Nakamura, M., Yoshida, T., Kiyono, R., Sato, S., & Takahashi, N. The effect of low-intensity resistance training after heat stress on muscle size and strength of triceps brachii: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelt. Disord.20, 1–6. 10.1186/s12891-019-2991-4 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Stadnyk, A. M., Rehrer, N. J., Handcock, P. J., Meredith-Jones, K. A., & Cotter, J. D. No clear benefit of muscle heating on hypertrophy and strength with resistance training. Temperature5(2), 175–183. 10.1080/23328940.2017.1391366 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.White, A. C. et al. Does heat acclimation improve exercise capacity at altitude? A cross-tolerance model. Int. J. Sports Med.35(12), 975–981. 10.1055/s-0034-1368724 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Gibson, O. R., Taylor, L., Watt, P. W., & Maxwell, N. S. Cross-adaptation: heat and cold adaptation to improve physiological and cellular responses to hypoxia. Sports Med.47, 1751–1768. 10.1007/s40279-017-0717-z (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Baranauskas, M. N. et al. Heat versus altitude training for endurance performance at sea level. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev.49, 50–58. 10.1249/JES.0000000000000238 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Buchheit, M. et al. Adding heat to the live-high train-low altitude model: a practical insight from professional football. Brit. J. Sports Med.47, i59–i69. 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092559 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Hargreaves, M., & Spriet, L. L. Skeletal muscle energy metabolism during exercise. Nature Metabol.2(9), 817–828. 10.1038/s42255-020-0251-4 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.https://sites.google.com/view/ipaq/home (accessed on 18.02.2022)

- 28.Biernat, E., Stupnicki, R., Lebiedziński, B., & Janczewska, L. Assessment of physical activity by applying IPAQ questionnaire. Phys. Educ. Sport.52, 83–89 (2008).

- 29.Mistura, L., Comendador Azcarraga, F. J., D’Addezio, L., Martone, D., & Turrini, A. An Italian case study for assessing nutrient intake through nutrition-related mobile apps. Nutrients13(9), 3073. 10.3390/nu13093073 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Inbar, O., Bar-Or, O., & Skinner, J. S. The Wingate anaerobic test. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics (1996).

- 31.Barfield, J. P., Sells, P. D., Rowe, D. A., & Hannigan-Downs, K. Practice effect of the Wingate anaerobic test. J. Strength Cond. Res. 16, 472–473 (2002). [PubMed]

- 32.Bhambhani, Y., & Singh, M. Ventilatory thresholds during a graded exercise test. Respiration47, 120—128. 10.1159/000194758 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Binder, R.K. et al. Methodological approach to the firstand second lactate threshold in incremental cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Prev. Rehabil.15, 726–734. 10.1097/HJR.0b013e328304fed4 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Coleman, S., Hale, T., & Hamley, E. A comparison of power outputs with rolling and stationary starts in the Wingate anaerobic test. J. Sports Sci.3, 207–208 (1985).

- 35.Borg, G.A. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med. Sci. Sports Exer.14, 377–381 (1982). [PubMed]

- 36.Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the behavioral sciences. (Routledge Academic: New York, NY, USA, 1988).

- 37.Maciejczyk, M., Palka, T., Wiecek, M., Masel, S., & Szygula, Z. The Effects of Intermittent Hypoxic Training on Anaerobic Performance in Young Men. Appl. Sci.14, 676. 10.3390/app14020676 (2024).

- 38.Katayama, K., Yoshitake, Y., Watanabe, K., Akima, H., & Ishida, K. Muscle deoxygenation during sustained and intermittent isometric exercise in hypoxia. Med. Sci. Sports Exer.42, 1269–1278. 10.1249/mss.0b013e3181cae12f (2010). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Fernández-Lázaro, D. et al. Electromyography: A simple and accessible tool to assess physical performance and health during hypoxia training. A systematic review. Sustainability12(21), 9137. 10.3390/su12219137 (2020).

- 40.Scott, B. R., Slattery, K. M., Sculley, D. V., Lockhart, C., & Dascombe, B. J. Acute physiological responses to moderate-load resistance exercise in hypoxia. J. Strength Cond. Res.31, 1973–1981. 10.1519/JSC.0000000000001649 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Amann, M., Romer, L. M., Subudhi, A. W., Pegelow, D. F., & Dempsey, J. A. Severity of arterial hypoxaemia affects the relative contributions of peripheral muscle fatigue to exercise performance in healthy humans. J. Physiol.581, 389–403. 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.129700 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Sotiridis, A., Miliotis, P., Ciuha, U., Koskolou, M., & Mekjavic, I. B. No ergogenic effects of a 10-day combined heat and hypoxic acclimation on aerobic performance in normoxic thermoneutral or hot conditions. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol.119(11), 2513–2527. 10.1007/s00421-019-04215-5 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.McCleave, E. L. et al. Impaired heat adaptation from combined heat training and “live high, train low” hypoxia. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform.14(5), 635–643. 10.1123/ijspp.2018-0399 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Yamaguchi, K. et al. Acute performance and physiological responses to repeated-sprint exercise in a combined hot and hypoxic environment. Physiol. Rep.8(12), e14466. 10.14814/phy2.14466 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.McCleave, E. L. et al. Concurrent heat and intermittent hypoxic training: No additional performance benefit over temperate training. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform.15(9), 1260–1271. 10.1123/ijspp.2019-0277 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Rendell, R. A. et al. Effects of 10 days of separate heat and hypoxic exposure on heat acclimation and temperate exercise performance. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol.313(3), R191–R201. 10.1152/ajpregu.00103.2017 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Yatsutani, H. et al. Endocrine and metabolic responses to endurance exercise under hot and hypoxic conditions. Front. Physiol.11, 932. 10.3389/fphys.2020.00932 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Chikani, V., Cuneo, R. C., Hickman, I., & Ho, K. K. Growth hormone (GH) enhances anaerobic capacity: impact on physical function and quality of life in adults with GH deficiency. Clin. Endocrinol.85, 660–668. 10.1111/cen.13147 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Yamaguchi, K., Imai, T., Yatsutani, H., & Goto, K. A combined hot and hypoxic environment during maximal cycling sprints reduced muscle oxygen saturation: a pilot study. J. Sports Sci. Med.20(4), 684. 10.52082/jssm.2021.684 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Hedley, A. M., Climstein, M., & Hansen, R. The effects of acute heat exposure on muscular strength, muscular endurance, and muscular power in the euhydrated athlete. J. Strength Cond. Res.16(3), 353–358 (2002). [PubMed]

- 51.Toro-Román, V. et al. Effects of High Temperature Exposure on the Wingate Test Performance in Male University Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health20(6), 4782. 10.3390/ijerph20064782 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Bergeron, M. F. et al. International Olympic Committee consensus statement on thermoregulatory and altitude challenges for high-level athletes. Brit. J. Sports Med.46, 770–779. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091457 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Millet, G. P., Girard, O., Beard, A., & Brocherie, F. Repeated sprint training in hypoxia–an innovative method. Dtsch. Z. Sportmed. 5, 115–122. 10.5960/dzsm.2019.374 (2019).

- 54.Takei, N., Kakinoki, K., Girard, O., & Hatta, H. Short-Term Repeated Wingate Training in Hypoxia and Normoxia in Sprinters. Front. Sports Act. Living2, 43. 10.3389/fspor.2020.00043 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Warnier, G. et al. Effects of Sprint Interval Training at Different Altitudes on Cycling Performance at Sea-Level. Sports8, 148. 10.3390/sports8110148 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Pramkratok, W., Songsupap, T., & Yimlamai, T. Repeated sprint training under hypoxia improves aerobic performance and repeated sprint ability by enhancing muscle deoxygenation and markers of angiogenesis in rugby sevens. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol.122, 611–622. 10.1007/s00421-021-04861-8 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Hendriksen, I. J., & Meeuwsen, T. The effect of intermittent training in hypobaric hypoxia on sea-level exercise: a cross-over study in humans. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 88, 396–403. 10.1007/s00421-002-0708-z (2003). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Fennel, Z. J., Amorim, F. T., Deyhle, M. R., Hafen, P. S., & Mermier, C. M. The heat shock connection: skeletal muscle hypertrophy and atrophy. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol.323, R133–R148. 10.1152/ajpregu.00048.2022 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.