Abstract

The neurexin superfamily, consisting of neurexins and Casprs, play important roles in the development, maintenance, function, and plasticity of neuronal circuits. Caspr/CNTNAP genes are linked to alterations in neuronal circuits and associated with neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative conditions. Casprs are implicated in multiple neuronal signaling pathways, including dopamine; however, the molecular mechanisms by which Casprs differentially alter specific signaling pathways and downstream behaviors are unclear. We find that the C. elegans Caspr nlr-1 functions in neurons to control foraging behaviors, acting in distinct monoamine neurons to modulate locomotor activity in the presence or absence of food. nlr-1 functions in dopamine neurons to reduce activity in the absence of food, similar to the role of dopamine, and regulates dopamine signaling through D2-like receptors. Furthermore, nlr-1 contributes to proper morphology and presynaptic structure of dopamine neurons, dopamine receptor expression and localization, and the behavioral response to dopamine. We find that nlr-1 similarly regulates another dopamine-dependent behavior, the basal slowing response. Therefore, spatial manipulation of a broadly expressed neuronal gene is sufficient to alter neural circuits and behavior and uncovers important functions masked by global manipulation, highlighting the importance of genetic variation and mechanisms that impact spatial expression of genes to behavior.

Subject terms: Feeding behaviour, Molecular neuroscience, Genetics of the nervous system, Cellular neuroscience, Neural circuits

Removal of nlr-1/CNTNAP from monoamine neurons in C. elegans reveals neuron-specific roles in foraging behaviors, including a critical role for nlr-1 in dopamine neuron morphology, synapse structure, and synapse function that resembles loss of dopamine signaling itself.

Introduction

Structural and functional properties of neuronal circuits underlie animal behavior, which can be altered through many modulatory mechanisms, including monoamine signaling pathways. The wiring of neuronal circuits requires proper coordination of synaptic adhesion molecules that facilitate the development and maturation of the connections between neurons at synapses and the maintenance of proper synapse function. The neurexin superfamily of genes, consisting of neurexins and contactin associated proteins (Casprs), are a major class of synaptic adhesion molecules required for the development and function of synapses. Humans have five Caspr genes (CNTNAP1, CNTNAP2, CNTNAP3, CNTNAP4, and CNTNAP5) and several of these genes have been linked to behavioral changes observed in individuals with autism and schizophrenia1–7. Additionally, Casprs have been linked to neurodegenerative diseases, with reduced Caspr2 expression found in the hippocampus of Alzheimer’s Disease patients8, decreased gene expression in the blood of patients with Parkinson’s Disease9 and increased cerebrospinal fluid and plasma expression of Caspr4 in patients with Parkinson’s Disease10.

Mutations in CNTNAP gene orthologues lead to a variety of alterations in the nervous system in animal models. Mice lacking Cntnap2, Cntnap3, and Cntnap4 can have alterations in neural and synaptic development11–16, connectivity17, neuronal gene expression18, channel19 and receptor localization20, and neurophysiology21. Further, Cntnap2, Cntnap3, and Cntnap4 knockout mice have altered behaviors including social behaviors12,15,16,22–24, nest building16, hyperactivity15,24, repetitive behaviors12,15,16,24, and motor behaviors10,21. The conserved monoamine neurotransmitter dopamine, which plays important roles in modulating synaptic circuits by modifying neuronal circuits and behavior, has also been linked to Casprs previously in mice, with Cntnap4 mice having decreased output from cortical GABA neurons, but increased dopamine release from neurons in the nucleus accumbens21. Mice lacking Cntnap4 in dopamine substantia nigra neurons also exhibit increases in α-synuclein, motor dysfunction, and dopamine neuron degeneration, hallmarks of Parkinson’s Disease10. Further, intervention with the dopamine and serotonin-targeting antagonist risperidone reduced repetitive behaviors observed with loss of Cntnap2 in mice16. Thus, there appears to be a link between dopaminergic signaling and Caspr genes, however the mechanisms underlying how Caspr genes control dopamine signaling are unclear. Further, aside from the role of Cntnap4 in dopaminergic and GABAergic synapses, and the role of Cntnap4 in substantia nigra dopamine neurons10,21, little is known about how Caspr genes alter synapse structure and function of specific populations of neurons, and how these alterations impact circuits and behavior.

Behavioral responses to the presence or absence of food are crucial and conserved among all animals and are necessary for survival. C. elegans have a well-characterized neuronal circuit controlling responses to food and food deprivation, with the monoamines dopamine, serotonin, and octopamine (the invertebrate orthologue of norepinephrine), impacting locomotor activity and patterns in response to food levels and overall food-seeking strategies25–34. Dopamine reduces activity when on food through the basal slowing response via the D2-like receptor dop-333. Dopamine also inhibits the RIC interneuron pair25,26, which increases activity via octopamine signaling onto downstream targets30. Previously, we used the WorMotel device30,34–36 to monitor and quantify locomotor activity in C. elegans in the presence and absence of food. This allowed us to identify spatial and isoform-specific functions of the neurexin orthologue nrx-1 in C. elegans response to food deprivation. We also demonstrated that nrx-1 is required for proper octopamine circuit function34, linking neurexins to monoamine function. C. elegans have two orthologues of Caspr genes37, nlr-1 and itx-1, with nlr-1 expressed more broadly in neurons (95 neuron types including dopaminergic CEPs and ADF) and itx-1 expressed at very low levels in a handful of neurons, in intestine, and other nonneuronal tissue38. A recent study defined that nlr-1 localizes adjacent to gap junctions where it binds F-actin and helps cluster gap junction channels39, but roles for nlr-1 in monoamine signaling and dependent behaviors in C. elegans have not been investigated.

Here, we identify a requirement for nlr-1 in controlling the behavioral responses to the presence or absence of food. Through broad neuronal knockout and targeted knockout of nlr-1 in dopamine, octopamine, and serotonin neurons, we unmask roles for nlr-1 in modulating behavioral responses to food and food deprivation that were not observed with global loss of the gene. We further investigated the role of nlr-1 in dopamine signaling and demonstrate that nlr-1 is required for the structure of dopaminergic circuits, including dopamine neuron morphology and pre-synaptic morphology and molecular organization. We find that nlr-1 functions in non-dopamine neurons in the downstream behavioral response to dopamine, having a similar impact on behavior as complete loss of dopamine. We use a pharmacologic screening approach to confirm roles for nlr-1 in monoamine and dopamine signaling and identify candidate dopamine receptors involved in the nlr-1 behavioral phenotype. Validation of these findings with genetic approaches confirmed a role for 2 conserved D2-like dopamine receptors (dop-2/DRD2 and dop-3/DRD3) in the behavior, and that nlr-1 contributes to the expression and localization of the post-synaptic dop-3 receptor. Lastly, we test the role for nlr-1 in another dopamine mediated food behavior, basal slowing response, and find it has the same impact as complete loss of dopamine, expanding our findings to an additional behavior. These results further link the neurexin superfamily of genes to monoamine circuits and highlights that spatial expression of a gene across circuits and subpopulations of neurons can cause many changes in behavior.

Results

nlr-1 functions in distinct monoamine neurons to modulate behavioral responses to food levels

We were interested in the potential role of nlr-1 on the response to food and food deprivation in neurons and subsets of monoamine neurons. Complete loss of nlr-1 is embryonic/larval lethal39, so we obtained animals with a balanced heterozygous deletion in nlr-1. We also obtained animals with flippase recognition sites (frt) flanking regions of the endogenous nlr-1 gene, (coding and noncoding), allowing us to excise nlr-1 in a spatially restricted manner through cell-specific expression of the recombinase flippase (FLP) (Fig. 1A). Here we knocked out nlr-1 through expression of FLP in all neurons (rgef-1p::FLP), serotonin neurons (5-HT, tph-1p::FLP), dopamine neurons (DA, dat-1p::FLP), or octopamine neurons (OA, tbh-1p::FLP) (Supplementary Fig. 1B). This strain includes a mKate tag at the 3’ end of nlr-139, and we found that nlr-1 is expressed broadly in the nerve ring throughout development and into adulthood with some low-level expression in the pharynx (Supplementary Fig. 1C). Expressing FLP in all neurons eliminated expression of nlr-1 in the nerve ring (Supplementary Fig. 1D), and as previously shown, knocking out nlr-1 in neurons circumvents the lethality of homozygous deletions of nlr-1 globally39.

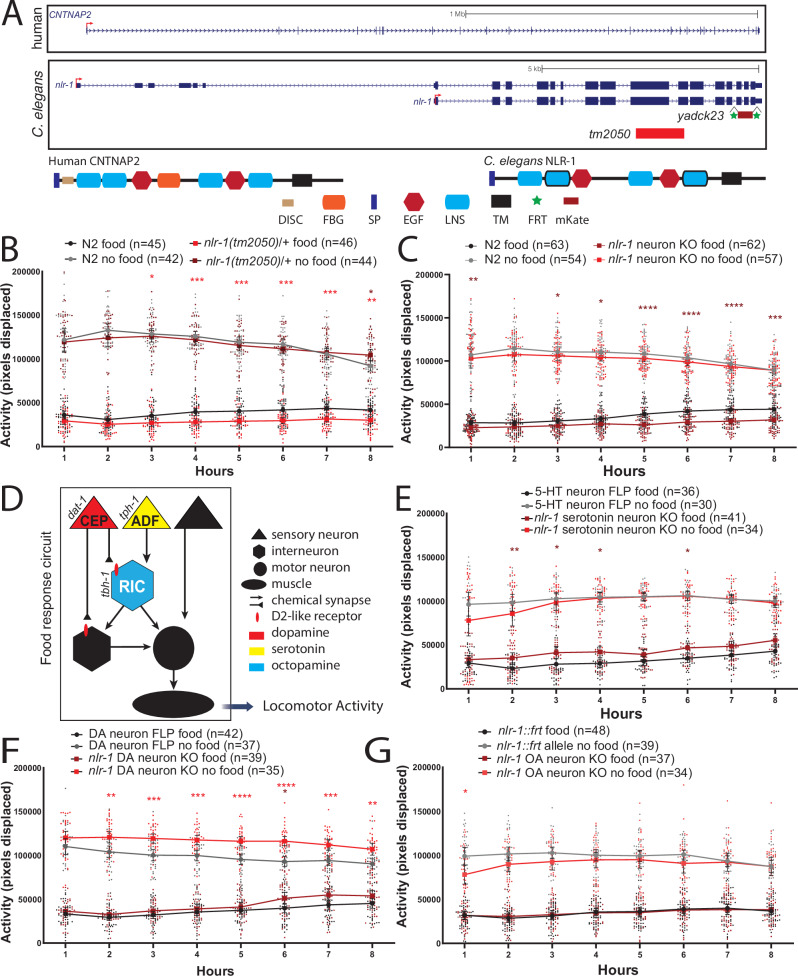

Fig. 1. nlr-1 functions in distinct monoamine neurons to modulate behavioral responses to food levels.

A Schematic of the human CNTNAP2 gene and the nlr-1 gene with the two alleles used in this study and cartoon of protein domains in CNTNAP2 and NLR-1 (DISC discoidin-like, FBG fibrinogen like, SP signal peptide, EGF epidermal growth factor like, LNS laminin/neurexin/sex hormone-binding globulin, TM transmembrane, FRT flippase recognition sites, mKate mKate fluorescent protein). Average activity of day 1 adult N2 control hermaphrodites in the presence (black) or absence of food (gray) compared with average activity of B nlr-1(tm2050)/+ mutants (burgundy with food, red without food), C animals lacking nlr-1 in all neurons (nlr-1::mkate::frt; rgef-1p::NLS::FLP) (burgundy with food, red without food). D Schematic of multiple monoamine neuromodulators acting on the circuit controlling responses to food and food deprivation. Dopamine and serotonin can reduce activity of the octopamine RIC interneurons, which releases octopamine onto downstream motor neurons and muscles to promote increases in activity levels. Dopamine can also act on the post-synaptic targets of RIC to reduce activity of the circuit. Dopamine acts on RIC and downstream targets of the circuit controlling responses to food deprivation predominantly through D2-like dopamine receptors. Average activity of day 1 adult control hermaphrodites in the presence (black) or absence of food (gray) compared with average activity of E animals lacking nlr-1 in serotonin neurons (5-HT, nlr-1::mkate::frt; tph-1p::NLS::FLP) (burgundy with food, red without food), F dopaminergic neurons (DA, nlr-1::mkate::frt; dat-1p::FLP::mNG) or G octopaminergic neurons (OA, nlr-1::mkate::frt; tbh-1::FLP). Control worms for each panel represent those run with each experimental allele respectively. Means are plotted as large dots connected with lines and 95% confidence intervals, smaller dots represent individual datapoints. Results of the two-way ANOVA with Tukey HSD post hoc test: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Color of significance symbols indicate difference from control of same condition (food or no food).

To test if nlr-1 plays a role in the behavioral response to food or food deprivation, we monitored activity of individual day 1 adult worms in the presence or absence of food on WorMotels (Supplementary Fig. 1A)30,34,35. As previously shown, worms deprived of food significantly increase their activity compared to activity when on food (Fig. 1). Heterozygous loss of nlr-1 reduced activity compared to controls on food beginning 2 h after placement on food, which lasted for the remainder of the 8 h recorded (Fig. 1B). nlr-1 heterozygous mutants had similar activity off food compared to controls. Loss of nlr-1 in all neurons (rgef-1p::FLP) significantly reduced activity on food with no effect off food, strongly resembling heterozygous loss of nlr-1 phenotype (Fig. 1C). The nlr-1::frt allele or the rgef-1p-::FLP driver individually did not alter activity on or off food compared to controls (Supplementary Fig. 1E, F). This suggests that nlr-1 in neurons contributes to the behavioral response to food. The circuits controlling the behavioral responses to food and food deprivation include the monoamines dopamine and serotonin acting on octopamine neurons (Fig. 1D). We predicted the reduction in activity seen in the nlr-1 neuron knockout mutants may result from enhanced dopamine or serotonin signaling, as both have roles in reducing speed or activity of animals on food29,31. Loss of nlr-1 in serotonin neurons (tph-1p::FLP), including NSM, ADF, HSN, and RIH (Supplementary Fig. 1B), results in increased activity on food with no consistent significant difference in activity off food compared to controls (Fig. 1E). Loss of nlr-1 in dopamine neurons (dat-1p::FLP), including CEPs, ADE, and PDE (Supplementary Fig. 1B), increased activity levels off food with no difference in activity on food compared to controls (Fig. 1F). Loss of nlr-1 in octopaminergic RIC neurons (Supplementary Fig. 1B) reduced activity levels off food during the first hour of food deprivation with no difference in activity on food compared to controls (Fig. 1G), remarkably similar to what we previously observed in worms lacking tbh-1, the anabolic enzyme that produces octopamine34. These results were in striking contrast to each other and distinct from the behavioral differences observed with loss of nlr-1 in all neurons, indicating that nlr-1 can promote or inhibit activity levels in response to food and suggesting a conserved role of Casprs in monoamine signaling in C. elegans. More broadly, these results indicate that manipulation of expression of nlr-1 in specific monoamine neuron populations reveals roles for nlr-1 in the responses to food that are masked by broader loss of nlr-1 in all neurons.

nlr-1 regulates the response to food deprivation through dopamine signaling

We wanted to further explore the potential role of nlr-1 in dopamine signaling suggested by the behavioral phenotype upon loss of nlr-1 in dopamine neurons and food deprivation (Fig. 2A). Dopamine is made from the conversion of tyrosine to L-DOPA by tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), and then conversion of L-DOPA to dopamine by DOPA-decarboxylase (DDC), with the rate-limiting TH enzyme encoded by the cat-2 gene in C. elegans. We find that animals lacking dopamine due to a mutation in cat-2/TH have increased activity off food compared to controls, with no difference in activity on food (Fig. 2B). This behavioral phenotype is the same as observed in animals lacking nlr-1 in dopamine neurons. To determine whether nlr-1 mediates the response to food deprivation by directly impacting dopamine signaling, we generated animals lacking both cat-2 and nlr-1 in dopamine neurons. These animals had increased activity off food compared to controls, similar to animals lacking nlr-1 in dopamine neurons (Fig. 2C), which suggests that nlr-1 regulates dopamine signaling from dopamine neurons to regulate activity levels off food. Prior studies identified roles for nlr-1 in gap junction formation39. To test the possibility that nlr-1 may alter locomotion in response to food deprivation through gap junctions, we expressed a dominant negative form of UNC-940 in dopamine neurons using the dat-1 promoter. Expression of dominant negative UNC-9 reduced activity in the absence of food, in stark contrast to the phenotype observed with loss of nlr-1 in dopamine neurons (Supplementary Fig. 2G), indicating that nlr-1 likely does not modulate activity levels in the absence of food through gap junctions.

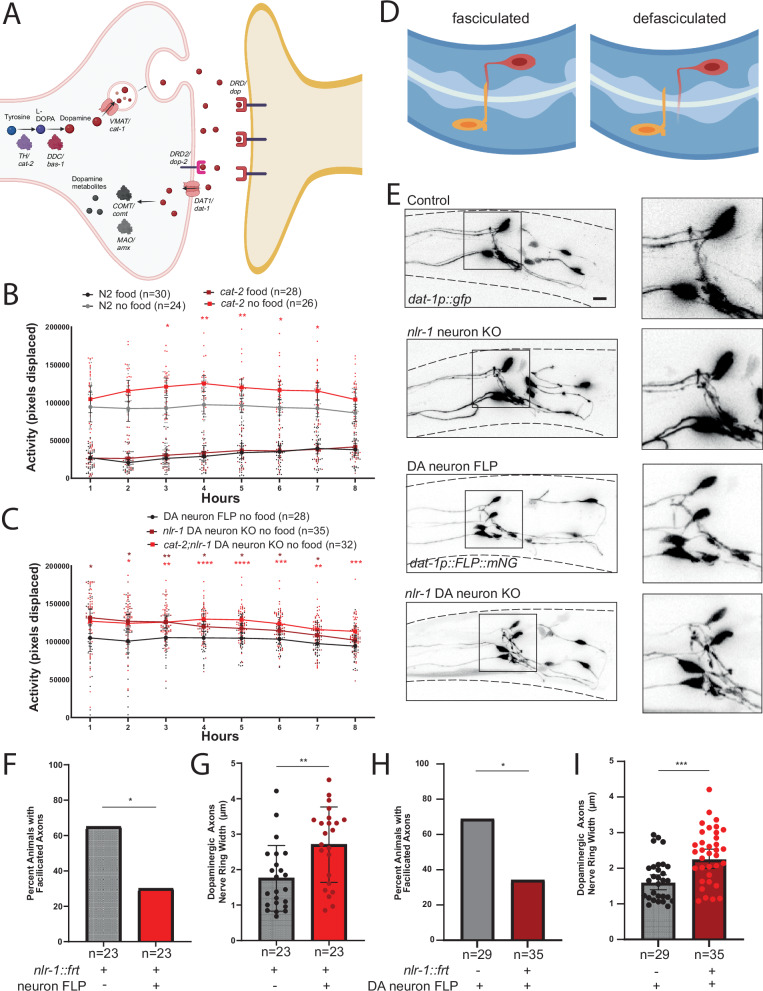

Fig. 2. nlr-1 regulates the response to food deprivation through dopamine signaling and organizes dopamine neuron morphology.

A Schematic of dopaminergic synapses with key genes involved in dopamine signaling with the corresponding C. elegans orthologue labeled. Average activity of day 1 adult control hermaphrodites in the presence (black) or absence of food (gray) compared with average activity of B cat-2 mutants in the presence (burgundy) or absence (red) of food and C cat-2 mutants also lacking nlr-1 in dopamine neurons (cat-2; nlr-1::mkate::frt; dat-1p::FLP::mNG) (red) or just animals lacking nlr-1 in dopamine neurons (burgundy) off food. Control worms for each panel represent those run with each allele respectively. Means are plotted as large dots connected with lines and 95% confidence intervals, smaller dots represent individual datapoints. Results of the two-way ANOVA with Tukey HSD post hoc test: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Color of significance symbols indicate difference from control of same condition. D Cartoon showing dopamine neurons in head of animals with or without properly fasciculated axons in the nerve ring. E Confocal micrographs of dopamine neurons (dat-1p::gfp) in the head of day 1 adult hermaphrodite control worms with the nlr-1 frt allele (nlr-1::mkate::frt), lacking nlr-1 in all neurons (nlr-1::mkate::frt; rgef-1p::FLP;mNG), control worms expressing FLP in dopaminergic neurons (dat-1::FLP::mNG) and worms lacking nlr-1 in dopaminergic neurons (nlr-1::mkate::frt;dat-1::FLP::mNG)(dashed lines outline animal body, scale bar = 10 μm) Quantification of F, H percent of day 1 adult hermaphrodites with fasciculated axons of dopamine neurons in the nerve ring and G, I width of dopamine neuron axons in the nerve ring. Percent of day 1 adult hermaphrodites with fasciculated axons was analyzed with a Fischer’s exact test and the width of dopamine neuron axons in the nerve ring was analyzed using an unpaired t-test: ns = p > 0.05, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

nlr-1 organizes dopamine neuron and synaptic morphology

Synaptic adhesion molecules can impact circuits through many mechanisms, including modification of neuron and synaptic structure and morphology. Casprs can localize and function in axons11,19, so we asked whether loss of nlr-1 impacts dopamine neuron and presynaptic morphology. We used fluorescent labeling of all dopamine neurons using expression of GFP under the dat-1 promoter (dat-1p::GFP) to visualize dopamine neuron morphology in controls and animals lacking nlr-1 in all neurons or lacking in just dopamine neurons. We noticed that the CEP neurons and axons appeared to have defects in nerve ring fasciculation in animals lacking nlr-1 in all neurons and in animals lacking nlr-1 in dopamine neurons (Fig. 2D, E and Supplementary Fig. 2D, E). While approximately 65% of controls had well fasciculated CEP axons, only 30% of nlr-1 neuron knockout animals and 35% of nlr-1 dopamine knockout animals had well fasciculated axons (Fig. 2F, G). We also measured the distance between dopamine neuron axons in the nerve ring, defined as the distance between the top of the most anterior to the bottom of the most posterior axonal projection (Fig. 2D), and found it was greater in nlr-1 neuron knockouts and nlr-1 dopamine neuron knockouts compared to respective controls (Fig. 2H, I). Further, the volume of the dopamine axon projections was also higher in nlr-1 neuron knockouts and in nlr-1 dopamine neuron knockouts (Supplementary Fig. 2A–C). This suggests that nlr-1 plays a role in dopamine neuron structure and morphology. We then visualized the presynaptic morphology of dopamine neurons by expressing a mRuby tagged CLA-1, the C. elegans orthologue of the presynaptic active zone marker bassoon (dat-1p::mRuby::cla-1). Control worms had bright, punctate expression of CLA-1 throughout the nerve ring around the pharynx. While neuronal knockout of nlr-1 eliminates nearly all NLR-1::MKATE expression in the nerve ring (Supplementary Fig. 1D), there is remaining signal in the pharynx, which required us to uniformly threshold all images for quantification using the mRuby-tagged CLA-1 construct (Fig. 3A). With this method we could occasionally observe bright CLA-1 puncta in the nlr-1 neuron knockouts that appeared distinct from any remaining NLR-1::MKATE expression (Fig. 3A). Quantification revealed all control animals with multiple bright CLA-1 puncta localized in the nerve ring, but only in 66% of the nlr-1 neuron knockout animals. Some nlr-1 neuron knockout animals had diffuse signal homogenously distributed across the nerve ring that could be diffuse mRuby tagged CLA-1 or background NLR-1 (Fig. 3A, B). Furthermore, the number of puncta in control animals was significantly higher than the number of presynaptic puncta in nlr-1 neuron knockout animals (Fig. 3C). We replicated these findings using a CLA-1 construct with a GFP tag, with 93% of controls forming bright CLA-1 puncta localized in the nerve ring compared to 70% of nlr-1 neuron knockout animals, and significantly fewer active zone puncta in nlr-1 neuron knockout animals compared to controls (Supplementary Fig. 3). Thus, nlr-1 appears to also have a role in organizing dopamine synaptic morphology that could explain its function we observe in mediating dopamine-dependent behavior.

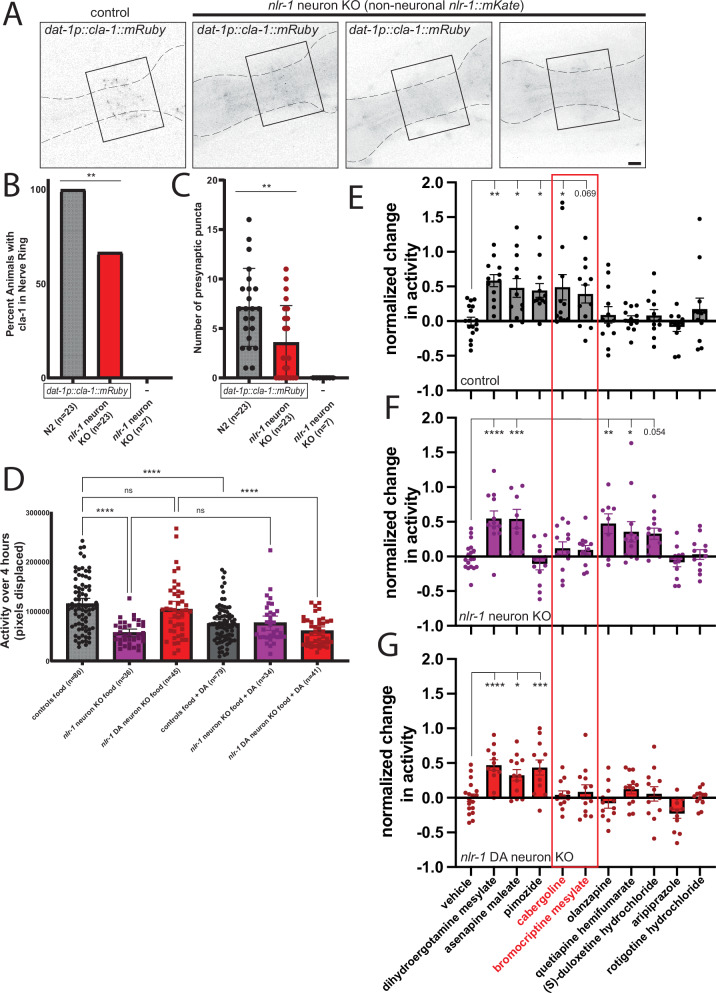

Fig. 3. nlr-1 is required for dopamine neuron pre-synaptic morphology, the behavioral response to dopamine, and dopamine targeting compounds.

A Confocal micrographs of dopamine neuron pre-synaptic sites (dat-1p::cla-1::mRuby) in controls and animals lacking nlr-1 in all neurons (nlr-1::mKate::frt; rgef-1p::FLP; dat-1p::cla-1::mRuby) (2 example images), or non-neuronal signal with no dopamine neuron pre-synaptic marker as a background example (dashed lines show pharynx, with mKate signal in nlr-1::mKate::frt; rgef-1p::FLP panels, solid line box indicates nerve ring location, scale bar = 10 μm). Quantification of percent of day 1 adult hermaphrodites B with dat-1p::cla-1::mRuby in nerve ring or C number of dat-1p::cla-1::mRuby puncta detected using thresholding to remove background and unbiased particle analysis. D Average activity of day 1 adult control hermaphrodites in the presence of food (black) or presence of food with 10 mM dopamine (gray) compared to animals lacking nlr-1 in all neurons (nlr-1::mkate::frt; pregef-1::NLS::FLP) or in dopaminergic neurons (nlr-1::mkate::frt; dat-1p::FLP::mNG) in the presence of food (dark purple and burgundy respectively) or in the presence of food with dopamine (red and light purple respectively). Results of the one-way ANOVA with Tukey HSD post hoc test: ns = p > 0.05, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Normalized change in activity with treatment of 0.1 mM of each compound indicated to vehicle alone in E controls, F nlr-1 neuron knockout (nlr-1::mkate::frt; prgef-1::NLS::FLP), or G nlr-1 dopamine neuron knockout (nlr-1::mkate::frt; dat-1p::FLP::mNG) (Red box indicates D2 receptor agonist compounds) Results of one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test: ns = not shown, p = ~0.05 included numerically, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001).

nlr-1 is required for non-dopamine neuron mediated behavioral responses to dopamine

To further define the role of nlr-1 in dopamine signaling, we asked whether loss of nlr-1 in all neurons or in dopamine neurons alters responsiveness of the circuit to exogenous dopamine. As expected based on previous work29,31,33, control animals on food plus 10 mM dopamine significantly decreased their activity compared to animals on food alone (Fig. 3D). Animals lacking nlr-1 in all neurons again had significantly lower activity on food compared to controls, however they had no significant difference in activity on food compared to on food with dopamine (Fig. 3D). Meanwhile, animals lacking nlr-1 in dopamine neurons had a similar response to exogenous dopamine as controls (Fig. 3D). This suggests that loss of nlr-1 in all neurons disrupts the ability to respond to dopamine, but loss of nlr-1 in dopamine neurons alone does not alter the downstream response to dopamine. These results further indicate that nlr-1 acts in non-dopamine neurons to facilitate the functional response to dopamine signaling, likely in downstream neurons.

Pharmacologic manipulation of monoamine signaling confirms roles for nlr-1 in dopamine signaling

To determine how and where nlr-1 functions within monoamine and dopamine signaling, we utilized a modified setup to test the behavioral impact of pharmacologic agents and compounds that target monoamine and dopamine pathways. Using a 96-well plate WormCamp (Worm Collective Activity Monitoring Platform) with populations of ~30 animals swimming in liquid in each well, we tested the impact of compounds on control and nlr-1 knockout strains (Supplementary Fig. 2F). We compared the impact of each compound on activity levels to activity levels of the respective genotype in vehicle alone (1% DMSO), however, this setup does not reliably allow us to quantify activity levels and relative impact between genotypes. We found that two compounds broadly targeting monoamine signaling systems (dihydroergotamine mesylate and asenapine maleate) increased activity levels in controls and both nlr-1 knockout strains (rgef-1p::FLP and dat-1p::FLP) (Fig. 3E–G and Supplementary Table 1). This demonstrates that we can detect the behavioral impact of compounds at this concentration, and that each genotype can increase activity levels while swimming in liquid buffer without food. Interestingly, we found that compounds targeting dopamine and/or serotonin more narrowly had differential impacts on the genotypes. A D2 dopamine receptor antagonist and serotonin receptor antagonist, pimozide, increased activity levels of controls and nlr-1 dopamine neuron knockouts, but had no impact on nlr-1 neuron knockouts (Fig. 3E–G and Supplementary Table 1). The D2 dopamine receptor agonist, cabergoline, increased activity of controls, but had no impact on either nlr-1 knockout strain (Fig. 3E–G and Supplementary Table 1). We found a similar pattern with another D2 dopamine receptor agonist, bromocriptine mesylate, although the increase in activity in controls did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 3E–G and Supplementary Table 1). Two serotonin antagonist and D2 dopamine antagonist compounds, olanzapine and quetiapine hemifumarate, had no impact on the activity of controls or nlr-1 dopamine neuron knockouts, but increased activity of nlr-1 neuron knockouts (Fig. 3E–G and Supplementary Table 1). A serotonin and dopamine reuptake inhibitor, (S)-duloxetine hydrochloride, had a similar pattern of impact on genotypes, but the increase in nlr-1 neuron knockouts did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 3E–G and Supplementary Table 1). The differential impacts of these compounds between genotypes suggests a complex interplay of serotonin and dopamine signaling, which was indicated by our behavioral characterization of animals lacking nlr-1 in subsets of monoamine neurons (Fig. 1), and suggests that nlr-1 impacts response to drugs targeting dopamine signaling and specifically those targeting D2 dopamine receptors (Supplementary Table 1). We also found compounds that did not impact activity of any of the genotypes (aripiprazole and rotigotine hydrochloride) (Fig. 3E–G).

We were surprised that several of the drugs targeting dopamine increased activity of the swimming animals, which is the opposite of the typical response of animals to dopamine signaling and our previous results (Fig. 3D)29,31,33. It is possible that dopamine alters the activity of swimming animals with and without food differently than crawling animals41. To test the impact of dopamine on the activity levels of animals swimming without food in this setup, we treated the same genotypes with increasing concentrations of exogenous dopamine. Remarkably, we found that control animals swimming without food responded to dopamine by increasing activity levels in a dose-dependent manner (Supplementary Fig. 2H). This unexpected impact of dopamine could be reflective of a change in the pattern of swimming or swimming activity levels41. We found that this impact of dopamine was reduced in magnitude in the nlr-1 knockout strains compared to controls but did result in subtle increases of activity at higher concentrations (Supplementary Fig. 2I, J). Thus, animals swimming without food increase activity with dopamine signaling, which while in contrast to our findings on solid agar in the WorMotel, the pattern of impact of dopamine on each genotype in the WorMotel and the WormCamp are mostly consistent. The reduction in activity of nlr-1 knockout strains in response to agonists of D2 dopamine receptors compared to controls, suggests that this class of receptors may be involved in nlr-1 function in this behavior.

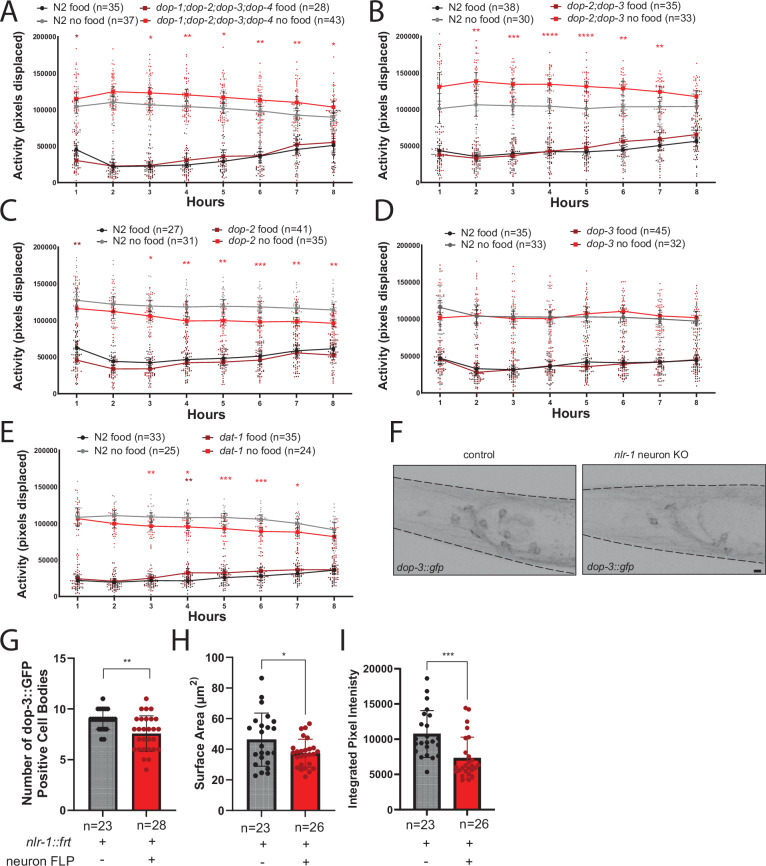

D2-like dopamine receptors mediate the dopamine-dependent response to food deprivation

Like mammals, worms have two classes of dopamine receptors: two D1-like receptors, dop-1 and dop-4, which stimulate neural activity and two D2-like receptors, dop-2 and dop-3, that inhibit neural activity. The differential impact of nlr-1 knockout strains compared to controls in response to compounds targeting D2 receptors suggested their involvement in the behavioral differences we observed in nlr-1 dopamine neurons. To pursue this idea, we obtained various single and combination mutants of these dopamine receptors and tested the impact on the response to food deprivation. We found that similar to cat-2 mutants and animals lacking nlr-1 in dopamine neurons, animals lacking all four dopamine receptors had increased activity off food compared to controls (Fig. 4A). To narrow down between the dopamine receptors, we tested the two D2-like class of dopamine receptors, dop-2 and dop-3, which are implicated in the foraging circuit (Fig. 1D)25. dop-2 and dop-3 double mutant animals also had increased activity off food compared to controls (Fig. 4B). We then tested D2-like receptor single mutants and found that, while dop-3 had no impact on activity levels, the dop-2 mutants had reduced activity off food compared to controls with no consistent differences on food (Fig. 4C, D). Loss of both D2-like receptors replicates the phenotype of loss of cat-2 and dopamine signaling broadly, but individual loss of D2-like receptors has the opposite or no impact. dop-2 can function both as a postsynaptic receptor and as a presynaptic autoreceptor that senses and modulates dopamine release42,43. Therefore, the decrease in activity off food we observe in dop-2 mutants could be explained by alterations in release of dopamine due to putative autoreceptor function. A resulting excess dopamine then acts on the remaining D2-like receptor dop-3 and reduces activity off food. To test this model, we analyzed the impact of loss of dat-1, the dopamine transporter that removes dopamine from the synapse, which thereby increases dopamine levels in the synapse. We found that dat-1 mutants have reduced activity off food compared to controls with no difference in activity on food compared to controls (Fig. 4E), similar to loss of dop-2 alone. Together, these results suggest redundancy in the role of dop-2 and dop-3 in altering responses to food deprivation and implicate dopamine signaling, particularly through D2-like receptors, in modulating responses to food deprivation. The reduction in the behavioral response to exogenous dopamine in the animals lacking nlr-1 in neurons could arise from a lost interaction between nlr-1 and D2-like receptor, altering function, localization, or clustering of the receptor at synapses.

Fig. 4. D2-like dopamine receptors mediate the response to food deprivation and nlr-1 contributes to D2-like receptor dop-3 expression and localization.

Average activity of day 1 adult control hermaphrodites in the presence (black) or absence of food (gray) compared with average activity of A dop-1;dop-2;dop-3;dop-4 quadruple mutants lacking all 4 dopamine receptors, B dop-2;dop-3 double mutants lacking both D2-like receptors, C dop-3 mutants, D dop-2 mutants, and E dat-1 mutants. Control worms for each panel represent those run with each allele respectively. Means are plotted as large dots connected with lines and 95% confidence intervals, smaller dots represent individual datapoints. Results of the two-way ANOVA with Tukey HSD post hoc test: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Color of significance symbols indicate difference from control of same condition. F Confocal micrographs of dop-3 dopamine receptor (dop-3::gfp) in the head of day 1 adult hermaphrodite controls or lacking nlr-1 in all neurons (nlr-1::mkate::frt; rgef-1p::FLP::mNG) (dashed lines outline animal body, scale bar = 10 μm). Quantification of G number of cell bodies with dop-3::gfp, H surface area of dop-3::gfp and I integrated pixel density of dop-3::gfp in controls and nlr-1 all neuron knockouts. Number of cell bodies with dop-3::gfp, surface area of dop-3::gfp, and integrated pixel density of dop-3::gfp were compared using an unpaired t-test: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

nlr-1 contributes to localization/expression of the D2-like dopamine receptor dop-3

To explore whether nlr-1 may be involved in dop-3 receptor localization or function, we obtained worms that express a GFP tagged DOP-3 under its endogenous promoter and utr (fosmid based), and compared expression in controls and nlr-1 neuron knockouts. We compared the number of neurons expressing DOP-3::GFP between controls and nlr-1 neuron knockout mutants and found nlr-1 knockouts had fewer DOP-3::GFP+ neurons than controls (Fig. 4F, G). We then compared the expression of DOP-3::GFP in a putative command interneuron (AVER/L based on expression and location of the neuron), which was present in nearly all animals. We found that DOP-3::GFP covered less surface area in nlr-1 mutants (Fig. 4H), and the mean intensity of DOP-3::GFP was lower than controls (Fig. 4I). These results suggest nlr-1 functions in dopamine receptor expression levels and localization, which may explain the reduced response to exogenous dopamine in animals lacking nlr-1 in all neurons. Collectively, these results demonstrate that nlr-1 has critical roles in the organization of dopamine circuits, controlling proper axonal localization and morphology and postsynaptic receptor localization, providing multiple potential mechanisms underlying the changes in dopaminergic circuit function and behavior we observed.

nlr-1 regulates the food- and dopamine-dependent basal slowing response behavior

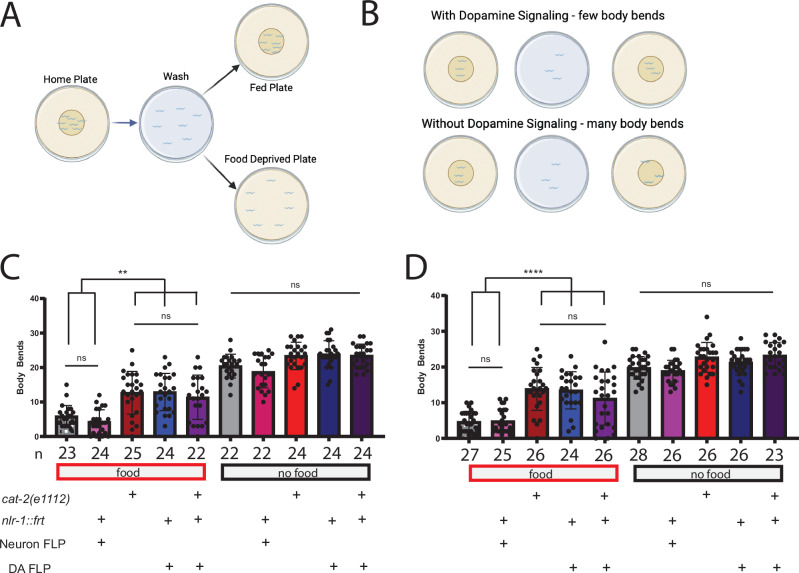

Lastly, we wanted to determine whether nlr-1 contributes to other dopamine-mediated behaviors in C. elegans. The C. elegans basal slowing response behavior is when a well-fed animal encounters the edge of a food patch and undergoes a decrease in activity or slowing to remain on food, which is dependent on dopamine. The slowing response behavior is quantified by comparing the number of body bends of animals that experimentally encounter food (animals placed on a plate with food) to animals that do not encounter food (animals placed on a plate with no food)(Fig. 5A, B). Control worms have significant reductions in body bends on food compared to off food. C. elegans lacking dopamine signaling, particularly through loss of dop-3 receptors, show a higher number of body bends on food compared to controls, with mixed findings as to if the number of body bends on food is significantly lower compared to body bends off food29,33,44. To test if loss of nlr-1 in dopamine neurons alters the basal slowing response, we performed this behavioral assay on the E. coli strain HB101, where the difference in basal slowing response in dopamine mutants was previously shown, and OP50, the primary food source used in the behavioral assays included in this study. As previously reported, controls taken off food, washed, and placed on food have a significant reduction in body bends compared to controls taken off food, washed, and placed on plates without food. This behavioral response was the same in controls regardless of the food source encountered (Fig. 5C, D). cat-2 mutants, which lack dopamine, had a significant reduction in body bends on OP50 and HB101 compared to no food. However, cat-2 mutants did have significantly more body bends on both food sources compared to controls, indicating a significant effect of dopamine loss on body bends as previously reported (Fig. 5C, D)29,33. Animals lacking nlr-1 in all neurons had a significant reduction in body bends when placed on either food source compared to no food, and the number of body bends on either food source did not significantly differ from controls. However, the number of body bends on either food source was lower than cat-2 mutants (Fig. 5C, D). Animals lacking nlr-1 in dopamine neurons had a reduction in body bends on both food sources, but the number of body bends was significantly higher than controls, though not significantly different than cat-2 mutants (Fig. 5C, D). Animals lacking both cat-2 and nlr-1 in dopamine neurons also had a reduction in body bends on either food source, and had a significantly higher number of body bends compared to controls. However, they did not significantly differ in body bend number compared to cat-2 mutants alone or worms that lacking nlr-1 in dopamine neurons alone (Fig. 5C, D). There were no differences in body bends between controls and any other genotype off food (Fig. 5C, D). These results highlight that the role of dopamine signaling in this behavior is completely dependent on nlr-1, similar to our findings with food deprivation. Loss of nlr-1 impacts multiple behaviors to the same levels as complete loss of dopamine, which suggests a strong requirement for nlr-1 in the release of and response to dopamine.

Fig. 5. nlr-1 regulates the food- and dopamine-dependent basal slowing response behavior.

A Schematic of the basal slowing response assay in which well-fed day 1 adults are removed from a home food plate, washed in M9, and placed either on a plate with food or a plate without food. Animals are given 5 min to acclimate and then body bends are counted for each worm for 20 s. B Control worms upon reentering food should have fewer body bends than worms with reduced dopamine signaling C, D body bends of control worms, worms lacking nlr-1 in all neurons, cat-2 mutants, worms lacking nlr-1 in dopaminergic neurons, and cat-2 mutants also lacking nlr-1 in dopamine neurons on C OP50 E. coli as a food source or a D HB101 E. coli as a food source. Means are plotted with 95% confidence intervals. Results of the one-way ANOVA with Tukey HSD post hoc test: ns = p > 0.05, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Discussion

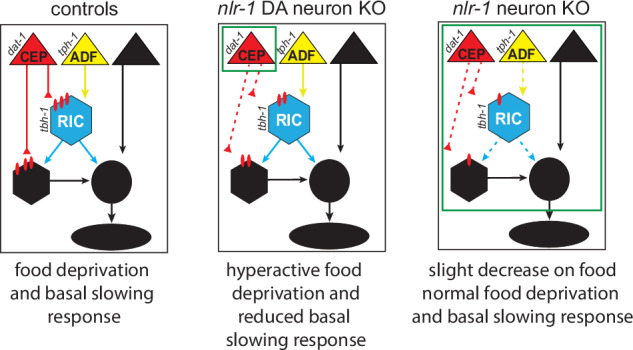

Responding to changes in the environment, including food levels, is critical for an organism’s ability to survive. The behavioral responses to food availability in C. elegans requires multiple neuromodulatory systems, including dopamine, to regulate activity and foraging strategies25–34. Here, we show that the C. elegans CNTNAP/Caspr ortholog nlr-1 modulates activity levels in the presence and absence of food. We find that nlr-1 functions in multiple monoamine neuron subtypes to promote or inhibit activity dependent on food context. We find that nlr-1 functions specifically in dopamine neurons to regulate dopamine signaling through control of synapse morphology, function, and behavior (Fig. 6). These results highlight the importance of considering how spatial expression and manipulation of a gene can uniquely alter behavior, as the role of nlr-1 in controlling dopamine-mediated behaviors was completely masked in broader knockouts of nlr-1. This can be particularly relevant to genes whose expression in neuronal subpopulations is regulated by multiple transcription factors expressed in different cell populations, and where loss of one transcription factor could lead to distinct circuit and behavioral alterations.

Fig. 6. Model for how nlr-1 impacts the food response and food deprivation response circuit.

In control worms, nlr-1 facilitates the function of monoamine circuits such as dopaminergic, serotonergic, and octopaminergic circuits. This involves positioning of dopaminergic axons and organization of pre and postsynaptic molecular structures. In worms lacking nlr-1 in dopamine neurons, dopamine signaling is disrupted, likely through alterations in dopamine axons and synapses, and results in hyperactive responses to food deprivation and reduced basal slowing responses compared to controls. In worms lacking nlr-1 in all neurons, there is likely disruption of multiple monoaminergic circuits that reduces monoamine signaling more broadly. While there are alterations in dopamine signaling, including dopamine axon positioning, synapses, and receptors, the effects these changes would have on behavior are obscured by broader circuit dysfunction of other neuromodulator systems upstream and downstream of dopamine signaling.

The role of nlr-1 in controlling responses to food and food deprivation appears to be dependent on distinct expression in multiple neuronal populations. Global loss of nlr-1 led to subtle hypoactivity on food, which was distinct from loss of nlr-1 in dopamine, octopamine, and serotonin neurons, which increased activity off food, decreased activity off food, and increased activity on food, respectively (Fig. 6). We previously described that spatial misexpression of nrx-1 isoforms across the nervous system can lead to changes in behavior unique from loss of function of the whole gene34. Our results here with nlr-1 suggest that manipulation of spatial expression of an endogenous gene can similarly lead to changes in behavior masked by global loss of function of that gene. This likely results from loss of nlr-1 in specific monoamine populations of neurons disrupting its function only in that specific part of the circuit, which has a unique role in behavioral modulation. For example, loss of nlr-1 in all neurons disrupts its function in serotonin, dopamine, and upstream and downstream neurons, which together balance out and have no major impact on behavior. However, loss of nlr-1 in just dopamine neurons retains function of nlr-1 in other neurons and parts of the circuit, resulting in unveiling the function specific to dopamine neurons. Casprs can have distinct roles in different neurons as reported from global Cntnap4 mutant mice, which had reduced GABAergic synaptic output and enhanced dopamine synaptic output21. A question arising from our findings would be whether loss of Cntnap4 in these specific neuronal populations would have different results than the global knockout. Taken together with our results, this demonstrates the complexity in studying genes expressed broadly in neurons, as results with global knockout may not reflect the exact function in that neuron subtype. This is further complicated by the role of this type of gene in monoamine and modulatory neuron populations, which can have many context dependent impacts on circuits and behaviors.

The spatial expression of many genes like CNTNAP2 can be regulated by multiple and differentially expressed transcription factors. Therefore, in addition to genetic variation that impacts CNTNAP/Caspr function or expression, genetic variation that impacts transcription factors that might alter the spatial expression of CNTNAP/Caspr could have similar or novel alterations in the nervous system and in behavior. CNTNAP2 is regulated by at least four known transcription factors: Storkhead box 1A (STOX1A), Transcription factor 4 (TCF4), Forkhead box P1 (FOXP1) and Forkhead box P2 (FOXP2)8,45–47. TCF4, FOX1A, and FOX1B have been linked to Pitt-Hopkins syndrome and schizophrenia45,48, verbal dyspraxia and impaired linguistic processing, and autism spectrum and intellectual disability respectively45–49. Elevated STOX1A expression and lower CNTNAP2 expression was also found in the hippocampus of individuals with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease8. While expression patterns of STOX1A have yet to be defined, TCF4, FOX1A and FOX1B have differential expression in specific brain regions and can either upregulate or downregulate expression49. Further, mutations in the 5’ promotor region of CNTNAP2 that altered transcription factor binding sites were associated with autism spectrum4. Therefore, circuit and behavioral changes could arise through changes in spatial expression of a synaptic adhesion molecule due to genetic variation in the gene itself, but also in regulatory transcription factors that perturb spatial expression across a circuit.

Here we linked nlr-1 to dopamine signaling through specific impacts on dopamine neurons and signaling mechanisms. Dopamine plays a major role in regulating C. elegans foraging behaviors. We showed that dopamine signaling, specifically through D2-like receptors dop-2 and dop-3, regulates locomotor activity in the absence of food by reducing the activity level of animals. Notably, loss of dop-2, which has described roles as a dopamine autoreceptor, decreased locomotion in the absence of food, which was the opposite of complete loss of dopamine signaling. This is likely the result of enhanced dopamine signaling due to a lack of auto-negative feedback to the dopamine releasing neuron(s), which lack the autoreceptor and have a reduced ability to sense synaptic dopamine levels. Animals with reduced synaptic reuptake of dopamine caused by mutation in the synaptic dopamine transporter, dat-1, had a similar hypoactivity off food, further supporting that excess dopamine signaling with food deprivation reduces activity—in contrast to the loss of dopamine itself, which increases it. Loss of nlr-1 in dopamine neurons regulates activity levels in the absence of food and in the basal slowing response, making it indistinguishable from loss of dopamine signaling altogether, and loss of both did not have an additive impact, supporting the importance of nlr-1 in dopamine signaling. Interestingly, in C. elegans, loss of the sole neuronal Caspr appeared to reduce dopamine signaling while in other organisms such as mice, with multiple neuronal Casprs, loss of a specific Caspr enhanced dopamine signaling. While speculative, the difference in the role of nlr-1 compared to CNTNAP2 and CNTNAP4 in controlling dopamine signaling could be because different mammalian Casprs could be playing different roles in presynaptic or postsynaptic organization leading to enhanced or reduced dopamine signaling (e.g., controlling dopamine metabolism/release, axon receptor localization or guidance, clustering presynaptic active zones and autoreceptors or postsynaptic receptors). This has been demonstrated with different types of neurexins, another group of genes in the neurexin superfamily, with recent studies in NRXN2 inhibiting synapse formation50, which is in contrast to NRXN1 which can promote synapse formation51. Alternatively, this could be the result of loss of upstream or modulatory functions of the same Caspr within the circuit because of global, rather than neuron-specific, knockout. Loss of CNTNAP4 had the opposite impact on GABAergic release compared to dopamine, and one could envision a change in dopamine release resulting from changes in inhibitory signaling.

We show that one molecular impact on dopamine circuit dysfunction results from nlr-1 functioning in shaping the overall neuron morphology and in organizing synapses. In C. elegans lacking nlr-1 in all neurons we found changes to the dopamine neuron axons, pre-synaptic structure, and postsynaptic receptor localization. In mice, Casprs play roles in axonal growth in vitro11 and neural migration in vivo16, suggesting roles of Casprs in correctly localizing neurons and their axons. Perturbations in the ability of the neurons to form and organize their axons could subsequently result in reduced ability to correctly form or localize their synapses, which could decrease presynaptic puncta, dopamine receptor localization, and response to dopamine. Our work defines a role for Casprs in the structure of dopamine circuits at the cellular and molecular level, providing mechanisms that underlie dopamine circuit dysfunction and changes in behavior. We find the opposite direction of impact on dopamine signaling compared with studies in Cntnap2 and Cntnap4 mice, which could be due to distinct roles for different Caspr genes in promoting or inhibiting synaptic output similar to neurexins, or as mentioned before, due to global versus neuron-specific manipulations. Our results suggest axon guidance, synapse formation and maintenance, and receptor localization could be molecular processes influenced by Casprs that can disrupt neuronal circuits controlling behavior.

In this study, we identify and define mechanisms for how the conserved autism and schizophrenia gene nlr-1 regulates dopamine signaling and circuits that underlie foraging behavior. We define the role of dopamine, a neuromodulator system broadly implicated in neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative conditions52, in controlling the behavioral response to food deprivation, including defining the role of autism and schizophrenia associated dopamine related genes in this behavior (dop-2/DRD2, dop-3/DRD3, and dat-1/DAT1)53. Although the foraging behaviors of C. elegans are quite removed from the behaviors altered in the human conditions, the role in multiple aspects of dopamine signaling are likely conserved and provide insight into crucial roles for this gene family in dopamine behavior. Much of the behavioral and neurophysiological work on Casprs focus on animals lacking a single Caspr globally, and often focus on a single brain area or neurotransmitter system, with few exceptions. Our work highlights the need to consider and study genes such as Casprs with spatial expression in mind. Casprs and other synaptic adhesion molecules can have different impacts on behavior based on their functions in different neuron types, where manipulations globally may mask roles in specific circuits, neuron types, and behaviors. Our work also highlights the need to investigate the mechanisms that coordinate spatial expression of genes like CNTNAP/Casprs, which may indirectly alter behavior and neuronal circuits through Caspr expression. We previously demonstrated that mis- or imbalanced expression of even single isoforms of the related neurexin gene nrx-1 can have differential impacts on foraging behaviors compared with global loss34. Isoforms of nlr-1/ CNTNAP are understudied, but as we learn more about the mechanisms regulating spatial and isoform-specific expression of synaptic adhesion molecules like neurexins and Casprs, future studies must carefully characterize spatial and isoform expression and how it changes with various manipulations. This will be necessary to detail how genes contribute to proper synapse development, function, and plasticity of multiple neuronal circuits and ultimately behavior.

Methods

C. elegans strains and cloning

Worms were grown on plates with Nematode Growth Media (NGM) agar seeded with Escherichia coli OP50 bacteria as a food source and raised at 20 °C. Unless otherwise noted, the N2 Bristol strain was used as the control strain. Strains are listed in Supplementary Table 2. To generate tbh-1p::FLP, the tbh-1 promoter (forward primer: acattacttaaattaccctataaacttct, reverse primer: aagcggcgttgtttgtggtgcgcccgtaga) was subcloned to replace the unc-4 promoter in pKE42 (a kind gift of Kelsie Eichel) To generate dat-1p::cla-1::mRuby, the dat-1 promoter (forward primer: gcctattccagtatgacccctttgaagcag, reverse primer: ctgaaaacacatgaatctagtatagtttta) was subcloned to replace the unc-17 promoter in PK18154. To generate dat-1p::cla-1::gfp, the dat-1 promoter (forward primer: gcctattccagtatgacccctttgaagcag, reverse primer: ctgaaaacacatgaatctagtatagtttta) was subcloned to replace the unc-17 promoter in PK06854. To generate dat-1p::unc-9(ΔN18), the dat-1 promoter (forward primer: gcctattccagtatgacccctttgaagcag, reverse primer: ctgaaaacacatgaatctagtatagtttta) was subcloned to replace the flp-13 promoter in pHM104 (flp-13p::unc-9(ΔN18)), a kind gift of Kota Mizumoto40.

tph-1p::FLP strain: To generate plasmid pBN550 tph-1p::FLP for integration into universal MosSCI landing sites55 (a 2.3 kb tph-1p::FLP::glh-2 3’UTR fragment was excised from pBN28056 with XmaI and NotI and inserted into NgoMIV/NotI of pBN857. Single-copy insertion of the tph-1p::FLP construct into the oxTi365 locus on chrV was done by microinjection into the gonads of EG8082 young adult hermaphrodites55,58. Plasmid pBN550 carrying FLP and unc-119(+) as selection marker was injected at 50 ng/µl together with pCFJ601 eft-3p::Mos159 (50 ng/µl), pBN1 lmn-1p::mCh::his-5857 (10 ng/µl), pCFJ90 myo-2p::mCh58 (2.5 ng/µl) and pCFJ104 myo-3p::mCh58 (5 ng/µl).

WorMotel behavioral assays for food deprivation and dopamine response

Worms were tested for behavioral responses to food and food deprivation using WorMotel multi-well PDMS chips30. WorMotels consist of 48 wells in a 6 × 8 grid that are 3 mm in diameter, 3 mm in depth, with a 3 mm deep moat between wells. WorMotels were created by molding PDMS in a 3D-printed WorMotel master mold. WorMotels were made temporarily hydrophilic to facilitate NGM agar filling the wells through treatment with plasma oxygen with RF settings set to medium (Basic Plasma Cleaner PDC-32g, Harrick Plasma). Each well was then filled with boiled NGM agar and allowed to solidify. Wells were then pipetted with 1.5 µL of concentrated liquid OP50 and/or OP50 with 10 mM dopamine (dopamine hydrochloride, Millipore Sigma) to ensure homogenous spread of the food across the entirety of the well. The WorMotels were then left in a 10 cm petri dish to dry with a damp tissue placed to increase humidity so the wells did not desiccate.

Approximately 5 h before WorMotel experiments, C. elegans were collected as late L4s and allowed to grow to day 1 adults on a new plate with a fresh OP50 lawn. Each worm was then transferred to a new NGM plate filled with M9 solution and washed to remove residual food. Worms were then pipetted either onto the agar of a well without food or onto a plate with OP50 before being manually transferred onto a well with food with a sterile platinum wire to not displace the OP50 in the wells. Petri dish lids were coated with 20% Tween 20 (Fisher BP337-500) to prevent water droplets from forming on the lid and then placed in a WormWatcher imaging platform (Tau Scientific Instruments, West Berlin, NJ, USA) with a damp tissue. WormWatchers captured images of the WorMotels every 10 s for 8 h. Images were then analyzed using an established MATLAB code35,36 divides the images into individual wells and calculates activity for individual worms by measuring changes in pixels through pixel subtraction of consecutive images taken 10 s apart from each other. These values were used to calculate activity for every hour or every 4 h. Activity of the worms was assessed before analysis to look for inconsistent values (such as temporary or lasting drops in activity between hours) and wells with abnormal values were further analyzed to ensure the worm did not escape the well. Worms that escaped the wells were not used in the final analysis. Worms from multiple replicates were pooled to ensure sufficient power determined from a power analysis in G*Power. Control worms were included in all WorMotels.

Pharmacologic compound behavioral analysis in WormCamp setups

An optical 96-well plate (Vision 96 Well Standard Black Microplate Clear Flat Bottom from Dot Scientific) was used as a Worm Collective Activity Monitoring Platform (WormCamp)60. In contrast to the WorMotel, the WormCamp measures the collective activity of a population of animals in each well. We selected compounds targeting monoamine pathways from the Tocriscreen FDA-approved drugs library (Tocris brand at Bio-Techne), purchased at 10 mM in DMSO (Supplementary Table 1). These compounds or dopamine (dopamine hydrochloride, Millipore Sigma) were added to wells at concentrations indicated and analyzed for impact on behavior in the WormCamp setup.

Strains were synchronized using standard alkaline hypochlorite solution methods (bleaching) approximately 48 h before setting up the assay allowing for the assay to be run with animals as day 1 adults. The optical 96-well plate was prepared 1 h before strain populations reached adulthood. The inner sixty wells of the 96-well plate were filled with 74 μL of M9 buffer using a multichannel pipette. The surrounding edge wells were not used to avoid edge effects from the WormWatcher camera system due to light refraction. One μL of compound from the library or DMSO vehicle was pipetted into each well. For compound screening each plate included four replicate wells per compound, and six replicates for vehicle alone (0.1 mM final concentration in well). Two or three independent replicate plates were run for each compound and each strain. The plate was left covered with aluminum foil on an orbital shaker at low speed for 1 h to equilibrate.

Fifteen minutes prior to the end of the mixing period the synchronized animals were washed off agar plates with food into a 15 mL conical tube. Once all worms were combined into the conical tube they were centrifuged at low speed for 2 min. The supernatant with food was aspirated off to ensure food-deprived conditions, and the worms were resuspended in 3 mL of M9 buffer. Centrifugation and aspiration was repeated as needed if the supernatant contained visible food. To achieve ~30 worms per well, animals were pipetted up and down to distribute evenly and then 25 μL was pipetted onto a microscope slide. Animals were counted under a dissecting scope and M9 buffer adjusted to dilute the concentration to 30 ± 5 worms/30 μL. The concentration was verified at least three additional times to ensure uniformity. Animals were transferred into a 25 mL Aspir-8™ Reservoir and put on an orbital shaker at high speed to ensure even suspension and distribution. To load the 96-well plate, a multichannel pipette was used to pipette 25 μL of the diluted animal suspension with the orbital shaker adjusted between pipetting to ensure suspension in solution. After all wells were filled with 25 μL (final volume of 100 μL per well) they were visually analyzed to note wells with low numbers of worms (<20 or fewer worms per well). Any such wells were noted and removed from analysis.

For dopamine experiments the protocol above was followed with the dopamine hydrochloride being diluted for stock concentrations in M9 buffer for the following final testing concentrations: 20 mM, 10 mM, 1 mM, 0.1, and 0 mM. Each plate had 12 replicates for each concentration, and each strain was run on three replicate plates per strain.

The loaded 96-well WormCamp plate was then placed in the WormWatcher imaging platform (Tau Scientific Instruments, West Berlin, NJ, USA). WormWatchers captured images of the WormCamp for 8–9 h. 12 images were captured per session (session is equal to 1 min), with sessions sequentially imaged every 10 min, and 6 sessions per hour. Images were processed in a manner similar to that previously described60 and from the WorMotel using analysis software created by Tau Scientific Instruments30. Briefly, sequential images were subtracted for each region of interest (each single well). The activity of each well for a frame was defined as the number of pixels changed within each well. To normalize activity to zero, 5 h of activity for each well was divided by the average activity of all DMSO vehicle alone wells on the same replicate plate for those 5 h minus 1.

Microscopy

An inverted Leica TCS SP8 laser-scanning microscope operated using LAS X software was used to analyze worms via fluorescence microscopy. Prior to imaging, worms were grown up to the desired age and anesthetized using 5 μL of 100 mM sodium azide on glass slides with a 5% agarose pad and then covered using a glass coverslip. Settings for the confocal laser and photomultiplier tube were consistent for each image acquisition setting for a given experiment. Confocal micrographs were generated in FIJI by creating z-stacks with maximum intensity projections. Figures were generated in Adobe Photoshop CS6 and Illustrator CS6.

CEP morphology analysis

CEP neuron morphology was compared using FIJI. Axon fasciculation was first qualitatively assessed by observing if either connection between the CEPDL and CEPVL neurons or CEPDR and CEPVR neurons consisted of converging or diverging axons. Then, using the measure tool in FIJI, the distance between the top of the most anterior axon to the bottom of the most posterior axon was measured in the connection in with the greatest distance between the CEPD and CEPV axons. Finally, using the 3D objects counter in FIJI, the volume of the dopamine axons was determined by selecting a 3D field of view (FOV) consisting of all of the projections, calculating volume of the FOV, and cropping portions in the 3D FOV in which cell bodies or other projections were present and subtracting that volume from the FOV volume.

cla-1 presynaptic puncta analysis

Puncta localization was analyzed using FIJI. Images were opened in FIJI, turned to z-stacks and saved in Adobe Photoshop, where the images were inverted, and the gamma was uniformly adjusted across all images to enhance contrast. The Z-stacks were loaded back into FIJI and thresholded uniformly such that synaptic puncta were visualized but background NLR-1 signal was not. The 3D-objects counter was then used to determine the number of puncta.

dop-3 receptor analysis

dop-3 localization was assessed using strains with a fosmid-based GFP signal fused to the receptor (DOP-3:GFP) and analyzed in FIJI and Adobe Photoshop. Images were opened in FIJI, turned into z-stacks, then opened in Photoshop, and the number of GFP+ cell bodies was counted. The AVEL/R neuron was reliably expressed in nearly all images, so the surface area and average density was calculated for this neuron using FIJI’s object counter.

Basal slowing response

Worms were tested for their basal slowing response as previously described29,33. Briefly, 5–8 worms were raised to day 1 young adults on OP50, washed using M9, and pipetted onto either plates coated with a ring of OP50 or HB101 or a non-seeded plate of NGM. The worms were allowed to acclimate for 5 min and then body bends were counted for each worm for 20 s. Worms were pipetted with enough distance between worms to reduce interactions, as interactions between worms altered their body bend number. Worms on the seeded plates that did not reach the food after 5 min were not used.

Statistics and reproducibility

Food deprivation WorMotel activity values were binned by hour to measure changes in foraging activity overtime and comparisons between activity of each genotype and condition at each time point were analyzed via two-way repeated measures ANOVA with a Tukey HSD post hoc test. A Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied as sphericity was not assumed. The first 4 h of dopamine treatment WorMotels were aggregated and used for analysis, and differences between genotypes and conditions was analyzed via one-way ANOVA with a Tukey HSD post hoc test. The basal slowing response was analyzed using a one-way ANOVA with a Tukey HSD post hoc test. A Fischer’s exact test was conducted to compare the proportion of fasciculated axons between controls and nrl-1 neuron knockout mutants and the proportion of worms with presynaptic puncta between controls and nlr-1 neuron knockout mutants. CEP axonal volume, nerve ring width of dopamine axons, number of DOP-3::GFP+ cell bodies, surface area of DOP-3::GFP expression, average intensity of DOP-3::GFP in interneuron (likely AVER/L), and number of presynaptic puncta between controls and nlr-1 neuron knockout mutants was analyzed via unpaired t-test. Of note, only the comparison between control worms expressing cla-1 and nlr-1 neuron knockout mutants expressing cla-1 could be compared because the nlr-1 neuron knockout condition not expressing cla-1 had a variance of 0. TocriScreen compound and dopamine normalized change in activity from WormCamp assays were compared to vehicle-alone controls using a one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test. Statistical analyses were conducted in Prism and all graphs were generated using Prism. G*Power61 was used to conduct power analysis to determine minimum sample size. Potential well location effects of the WorMotel were addressed by ensuring all genotypes had at least one WorMotel experiment where they were placed on each row. Unbiased computer vision analysis determined the activity values for WorMotel. Sample size is reported in each figure. Biorender.com was used to generate cartoons in Figs. 2A, D and 5A, B and Supplementary Figs. 1B and 2A.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Hart lab for technical assistance. The authors thank Dong Yan for providing NYL2730, which was used to cross nlr-1::mkate::frt into various strains and Peter Askjaer for providing BN1384 and BN1429, which were used to cross dat-1p::FLP::mNG and tph-1p::FLP into various strains, and for writing the methods for creation of BN1384. The authors thank Meera V. Sundaram and David M Raizen for their feedback on this project. The authors also thank Anthony D. Fouad (Tau Scientific) for technical support. Some strains were provided by the CGC, which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440). This work was supported by a Penn NGG Hearst Foundation Fellowship (B.L.B.), and by NIGMS of the NIH under 1R35GM146782 (M.P.H.).

Author contributions

B.L.B. and M.P.H. conceived and designed the study and experiments and B.L.B. conducted all behavioral WorMotel experiments and basal slowing response experiments. M.P.H. designed and generated cloning, plasmids and injected to generate strains. W.R.H. and W.R.S. assisted with behavioral experiments. B.L.B. conducted microscopy experiments. B.L.B. processed and analyzed all WorMotel, basal slowing response, and microscopy data, B.L.B. and M.P.H. wrote the manuscript and all authors reviewed, revised, and approved the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Asuka Takeishi and Benjamin Bessieres. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

All data that support the findings of this study are represented in the article, Supplementary tables, and figures and are available on Mendeley data as Hart, Michael (2024), “nlr-1/CNTNAP regulates dopamine circuit structure and foraging behaviors in C. elegans”, (doi: 10.17632/44g5zg4gt6.1). All data, plasmids, and strains are also available from the corresponding author upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s42003-024-06936-6.

References

- 1.Fang, F. et al. Association between genetic variants in DUSP15, CNTNAP2, and PCDHA genes and risk of childhood autism spectrum disorder. Behav. Neurol.2021, 1–6 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alarcón, M. et al. Linkage, association, and gene-expression analyses identify CNTNAP2 as an autism-susceptibility gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet.82, 150–159 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jang, W. E. et al. Cntnap2-dependent molecular networks in autism spectrum disorder revealed through an integrative multi-omics analysis. Mol. Psychiatry28, 810–821 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiocchetti, A. G. et al. Variants of the CNTNAP2 5’ promoter as risk factors for autism spectrum disorders: a genetic and functional approach. Mol. Psychiatry20, 839–849 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee, I. S. et al. Characterization of molecular and cellular phenotypes associated with a heterozygous CNTNAP2 deletion using patient-derived hiPSC neural cells. npj Schizophr. 1, 15019 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Friedman, J. I. et al. CNTNAP2 gene dosage variation is associated with schizophrenia and epilepsy. Mol. Psychiatry13, 261–266 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ji, W. et al. CNTNAP2 is significantly associated with schizophrenia and major depression in the Han Chinese population. Psychiatry Res.207, 225–228 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Abel, D. et al. Direct downregulation of CNTNAP2 by STOX1A is associated with Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis.31, 793–800 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Infante, J. et al. Identification of candidate genes for Parkinson’s disease through blood transcriptome analysis in LRRK2-G2019S carriers, idiopathic cases, and controls. Neurobiol. Aging36, 1105–1109 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang, W. et al. CNTNAP4 deficiency in dopaminergic neurons initiates Parkinsonian phenotypes. Theranostics10, 3000–3021 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canali, G. et al. Genetic variants in autism-related CNTNAP2 impair axonal growth of cortical neurons. Hum. Mol. Genet.27, 1941–1954 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tong, D. et al. The critical role of ASD-related gene CNTNAP3 in regulating synaptic development and social behavior in mice. Neurobiol. Dis.130, 104486 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ashrafi, S. et al. Neuronal Ig/Caspr recognition promotes the formation of axoaxonic synapses in mouse spinal cord. Neuron81, 120–129 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gdalyahu, A. et al. The autism related protein contactin-associated protein-like 2 (CNTNAP2) stabilizes new spines: an in vivo mouse study. PLoS ONE10, e0125633 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scott, R. et al. Loss of Cntnap2 causes axonal excitability deficits, developmental delay in cortical myelination, and abnormal stereotyped motor behavior. Cereb. Cortex29, 586–597 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peñagarikano, O. et al. Absence of CNTNAP2 leads to epilepsy, neuronal migration abnormalities, and core autism-related deficits. Cell147, 235–246 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lazaro, M. T. et al. Reduced prefrontal synaptic connectivity and disturbed oscillatory population dynamics in the CNTNAP2 model of autism. Cell Rep.27, 2567–2578.e6 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flaherty, E. et al. Patient-derived hiPSC neurons with heterozygous CNTNAP2 deletions display altered neuronal gene expression and network activity. NPJ Schizophr.3, 35 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poliak, S. et al. Caspr2, a new member of the Neurexin superfamily, is localized at the juxtaparanodes of myelinated axons and associates with K+ channels. Neuron24, 1037–1047 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Varea, O. et al. Synaptic abnormalities and cytoplasmic glutamate receptor aggregates in contactin associated protein-like 2/Caspr2 knockout neurons. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA112, 6176–6181 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karayannis, T. et al. Cntnap4 differentially contributes to GABAergic and dopaminergic synaptic transmission. Nature511, 236–240 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Selimbeyoglu, A. et al. Modulation of prefrontal cortex excitation/inhibition balance rescues social behavior in CNTNAP2-deficient mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 9, eaah6733 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Scott, K. E. et al. Loss of Cntnap2 in the rat causes autism-related alterations in social interactions, stereotypic behavior, and sensory processing. Autism Res.13, 1698–1717 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xing, X. et al. Suppression of Akt-mTOR pathway rescued the social behavior in Cntnap2-deficient mice. Sci. Rep.9, 3041 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suo, S., Culotti, J. G. & Van Tol, H. H. M. Dopamine counteracts octopamine signalling in a neural circuit mediating food response in C. elegans. EMBO J.28, 2437–2448 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suo, S. & Ishiura, S. Dopamine modulates acetylcholine release via octopamine and CREB signaling in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS ONE8, e72578 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Izquierdo, P. G., Calahorro, F. & Ruiz-Rubio, M. Neuroligin modulates the locomotory dopaminergic and serotonergic neuronal pathways of C elegans. Neurogenetics14, 233–242 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodríguez-Ramos, Á., Gámez-del-Estal, M. M., Porta-de-la-Riva, M., Cerón, J. & Ruiz-Rubio, M. Impaired dopamine-dependent locomotory behavior of C. elegans neuroligin mutants depends on the catechol-O-methyltransferase COMT-4. Behav. Genet.47, 596–608 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sawin, E. R., Ranganathan, R. & Horvitz, H. R. C. elegans locomotory rate is modulated by the environment through a dopaminergic pathway and by experience through a serotonergic pathway. Neuron26, 619–631 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Churgin, M. A., McCloskey, R. J., Peters, E. & Fang-Yen, C. Antagonistic serotonergic and octopaminergic neural circuits mediate food-dependent locomotory behavior in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Neurosci.37, 7811–7823 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hills, T., Brockie, P. J. & Maricq, A. V. Dopamine and glutamate control area-restricted search behavior in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Neurosci.24, 1217–1225 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krum, B. N. et al. Haloperidol interactions with the dop-3 receptor in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Neurobiol.58, 304–316 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chase, D. L., Pepper, J. S. & Koelle, M. R. Mechanism of extrasynaptic dopamine signaling in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat. Neurosci.7, 1096–1103 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bastien, B. L., Cowen, M. H. & Hart, M. P. Distinct neurexin isoforms cooperate to initiate and maintain foraging activity. Transl. Psychiatry13, 367 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Churgin, M. A. et al. Quantitative imaging of sleep behavior in Caenorhabditis elegans and larval Drosophila melanogaster. Nat. Protoc.14, 1455–1488 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grubbs, J. J., Lopes, L. E., van der Linden, A. M. & Raizen, D. M. A salt-induced kinase is required for the metabolic regulation of sleep. PLoS Biol.18, e3000220 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haklai-Topper, L. et al. The neurexin superfamily of Caenorhabditis elegans. Gene Expr. Patterns11, 144–150 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taylor, S. R. et al. Molecular topography of an entire nervous system. Cell184, 4329–4347.e23 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meng, L. & Yan, D. NLR-1/CASPR anchors F-Actin to promote gap junction formation. Dev. Cell55, 574–587.e3 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hendi, A. et al. Channel-independent function of UNC-9/Innexin in spatial arrangement of GABAergic synapses in C. elegans. Elife11, e80555 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Vidal-Gadea, A. et al. Caenorhabditis elegans selects distinct crawling and swimming gaits via dopamine and serotonin. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA108, 17504–17509 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Formisano, R. et al. Synaptic vesicle fusion is modulated through feedback inhibition by dopamine auto-receptors. Synapse74, e22131 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Pandey, P., Singh, A., Kaur, H., Ghosh-Roy, A. & Babu, K. Increased dopaminergic neurotransmission results in ethanol dependent sedative behaviors in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet.17, e1009346 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Petratou, D., Fragkiadaki, P., Lionaki, E. & Tavernarakis, N. Assessing locomotory rate in response to food for the identification of neuronal and muscular defects in C. elegans. STAR Protoc.5, 102801 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Forrest, M. et al. Functional analysis of TCF4 missense mutations that cause Pitt-Hopkins syndrome. Hum. Mutat.33, 1676–1686 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vernes, S. C. et al. A functional genetic link between distinct developmental language disorders. N. Engl. J. Med.359, 2337–2345 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.O'Roak, B. J. et al. Exome sequencing in sporadic autism spectrum disorders identifies severe de novo mutations. Nat. Genet.43, 585–589 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li, T. et al. Common variants in major histocompatibility complex region and TCF4 gene are significantly associated with schizophrenia in Han Chinese. Biol. Psychiatry68, 671–673 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rodenas-Cuadrado, P., Ho, J. & Vernes, S. C. Shining a light on CNTNAP2: complex functions to complex disorders. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 22, 171–178 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Lin, P. Y. et al. Neurexin-2: an inhibitory neurexin that restricts excitatory synapse formation in the hippocampus. Sci. Adv. 9, eadd8856 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Südhof, T. C. Synaptic neurexin complexes: a molecular code for the logic of neural circuits. Cell171, 745–769 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Franco, R., Reyes-Resina, I. & Navarro, G. Dopamine in health and disease: much more than a neurotransmitter. Biomedicines9, 109 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Nguyen, M. et al. Decoding the contribution of dopaminergic genes and pathways to autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Neurochem. Int.66, 15–26 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Kurshan, P. T. et al. γ-Neurexin and frizzled mediate parallel synapse assembly pathways antagonized by receptor endocytosis. Neuron100, 150–166.e4 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Frøkjær-Jensen, C. et al. Random and targeted transgene insertion in Caenorhabditis elegans using a modified Mos1 transposon. Nat. Methods11, 529–534 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]