Abstract

Starting October 2022, the Boston Public Health Commission implemented a neighborhood-level wastewater-based epidemiology program to inform strategies to reduce COVID-19 inequities. We collected samples twice weekly at 11 neighborhood sites, covering approximately 18% of Boston, Massachusetts’s population. Results from the program’s first year revealed inequities unobservable in regional wastewater data both between the City of Boston and the greater Boston area and between Boston neighborhoods. We report program results and neighborhood-specific recommendations and resources to help residents interpret and use our findings. (Am J Public Health. 2024;114(11):1217–1221. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2024.307749)

In Boston, Massachusetts, communities made vulnerable by systems of oppression have disproportionately borne COVID-19’s impact, with inequities in SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2) testing, COVID-19 vaccine uptake, and treatment.1,2 Wastewater-based epidemiology is an important tool for measuring community-level infection independent of disease severity or access to testing and clinical care and can inform public health efforts to address structural inequities.3–5 Wastewater SARS-CoV-2 testing has been ongoing in the greater Boston area since March 2020 through the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority. However, this regional program samples north and south influent covering 43 municipalities at Deer Island Treatment Plant and thus cannot identify inequities between the greater Boston area’s cities and towns and between the City of Boston neighborhoods.6

INTERVENTION AND IMPLEMENTATION

The Boston Public Health Commission (BPHC) developed a neighborhood-level, wastewater-based epidemiology program to elucidate inequities in the SARS-CoV-2 burden between the City of Boston and the greater Boston region and between Boston’s neighborhoods. These data inform the implementation of community-based strategies to reduce racialized and socioeconomic inequities in COVID-19 outcomes. We outline a concept to practice model for planning, implementing, and validating a neighborhood-level wastewater-based epidemiology program at a local health department.

BPHC launched a wastewater-based epidemiology program in October 2022 in collaboration with City of Boston partners and Biobot Analytics, a local wastewater-based epidemiology company.

Sampling Site Identification

Neighborhoods structure the health and well-being of residents through multiple intersecting pathways.7 Boston and the surrounding metro area are economically and racially segregated, with persistent inequities across neighborhoods (Figure A; Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).1 To evaluate potential sampling sites, we compared the size and sociodemographics of sewershed populations to those of surrounding neighborhoods (Table B; Figure B, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). We selected 11 sites covering 13 neighborhoods to maximize population coverage and representativeness citywide and by neighborhood, prioritizing neighborhoods most affected by persistent health inequities (Figure C; Supplementary Methods [available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org]). We excluded sampling along major roadways, which would have required hiring police officers to direct traffic.8 This enabled us to maintain a consistent sampling schedule and reduce program costs while avoiding traffic disruptions, occupational hazards for sample collectors, and additional police presence.

Wastewater Sampling and Processing

We collected time-weighted, 24-hour composite samples at each site twice weekly using autosamplers mounted in sewer holes. We processed samples according to previously described Biobot Analytics methods, including using a concentration of pepper mild mottle virus to normalize the concentration of the SARS-CoV-2 N1 gene (Supplementary Methods).9

PLACE, TIME, AND PERSONS

The 11 selected neighborhood sampling sites cover an estimated 119 179 people (∼18% of Boston’s population; Figure C). Sites ranged in estimated population from 1869 to 34 412 (Figure C), with 60% identifying as Black, Indigenous, Latinx, or other People of Color (Table C, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). In addition, this population was representative of the wider City of Boston on a range of sociodemographic characteristics that may shape the risk of SARS-CoV-2 exposure and severe COVID-19 outcomes, including educational attainment, poverty, household crowding, health insurance, and transportation to work (Table C). We collected samples twice weekly from each site and used data collected over the program’s first year in our analyses (October 2022–September 2023).

PURPOSE

To describe and validate program data as a measure of community-level SARS-CoV-2 infection, we compared wastewater SARS-CoV-2 concentrations to greater Boston area regional wastewater data and other COVID-19 clinical indicators (Table D, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org), focusing on both Boston citywide average comparisons and neighborhood-level comparisons.

We compared the citywide, population-weighted average SARS-CoV-2 concentration across all sites to regional wastewater concentrations to elucidate any inequities between the City of Boston and the greater Boston region. Next, we assessed the strength of correlation and timeliness of citywide average SARS-CoV-2 concentrations compared with regional wastewater trends and other citywide COVID-19 indicators with various lead or lag times (Table D).

We examined neighborhood-level inequities by comparing average SARS-CoV-2 concentrations across neighborhood sites. Finally, we compared spatial patterns observed in neighborhood-level wastewater data to those observed in clinical indicators (Table D).

EVALUATION AND ADVERSE EFFECTS

In the program’s first year, Boston’s citywide population-weighted average SARS-CoV-2 concentrations were consistently higher than regional wastewater concentrations (Figure D, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org): approximately 67% and 56% higher than Massachusetts Water Resources Authority North and South, respectively (Table E, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Temporal trends in citywide average SARS-CoV-2 concentrations were consistent with those observed in Massachusetts Water Resources Authority North regional wastewater (Figure 1). Citywide SARS-CoV-2 wastewater concentrations were also strongly correlated with subsequent clinical indicators: COVID-19 case rates (two-day lead; r = 0.89), emergency department visits (three-day lead; r = 0.94), new hospital admissions (10-day lead; r = 0.89), total inpatient hospitalizations (15-day lead; r = 0.94), total adult intensive care unit hospitalizations (17-day lead; r = 0.90), and COVID-19 deaths (21-day lead; r = 0.77; Figure 1; Figure E, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

FIGURE 1—

Trends, Lead Time, and Correlation in Citywide Population-Weighted Average SARS-CoV-2 Concentration Observed Across BPHC Sampling Sites Compared With (a) MWRA North Location Wastewater Concentration, (b) Reported COVID-19 Case Rates, (c) MWRA South Location Wastewater Concentration, (d) COVID-19 Emergency Department Visits, (e) New COVID-19 Hospital Admissions, and (f) COVID-19 Deaths: Boston, MA, October 2022–September 2023

Note. BPHC = Boston Public Health Commission; MWRA = Massachusetts Water Resources Authority; MWRA North = northern location; MWRA South = southern location. Red lines show SARS-CoV-2 concentration. Blue lines show COVID-19 indicators. COVID-19 clinical indicators included Boston-area regional wastewater concentrations from MWRA. All indicators were scaled and centered, with mean zero and units in SDs from the mean and shown with a LOESS (locally estimated scatterplot smoothing) line with a span of 0.15. Indicators were ordered by shortest lead time (MWRA North, 0 d) to longest lead time (COVID-19 deaths, +21 d). Details for each individual data source can be found in Table D (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org), and corresponding data for total inpatient hospitalizations and total adult intensive care unit hospitalizations can be found in Figure E (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

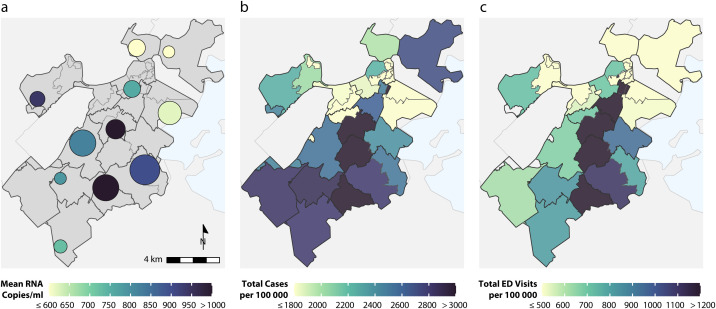

We observed substantial inequities in average SARS-CoV-2 concentrations across neighborhoods (Figure 2). In Roxbury, the neighborhood with the highest average values, wastewater concentrations were 2.5 times those observed in Charlestown, the neighborhood with the lowest average values (1179 copies/mL vs 463 copies/mL, respectively; Table F, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Overall, neighborhood-level inequities in wastewater concentrations corresponded with inequities in COVID-19 case rates and COVID-19 emergency department visits over the same period (Figure 2; Table F; Figure F, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) and also corresponded with neighborhood-level social vulnerability indices (Figure G, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). In some neighborhoods, wastewater concentrations may supplement clinical data. For example, in Allston–Brighton, the neighborhood with the highest test positivity, wastewater concentrations were relatively high compared with reported COVID-19 case rates and emergency department visits (Table F; Figure F).

FIGURE 2—

Representation of (a) Wastewater SARS-CoV-2 Concentration at BPHC Wastewater Neighborhood Sampling Sites, (b) Cumulative Reported COVID-19 Case Rates per 100 000 Population Across Boston ZCTAs, and (c) Cumulative COVID-19 Emergency Department (ED) Visits per 100 000 Population Across Boston ZCTAs: Boston, MA, October 2022–September 2023

Note. Sample size was n = 11. BPHC = Boston Public Health Commission; RNA = ribonucleic acid; ZCTA = zip code tabulation area. In panel a, the size of the circle corresponds to the population covered by the neighborhood sampling site. Table D (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) provides indicator definitions and sampling site description and details. Figure C (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) provides a list of neighborhood sampling sites.

We are unaware of any adverse effects of our intervention.

SUSTAINABILITY

Wastewater data are a robust, leading indicator of COVID-19 hospitalizations and reveal inequities across Boston neighborhoods unobservable in regional wastewater data, demonstrating the value of sustaining this program.10 Additionally, reported COVID-19 case rates rely on polymerase chain reaction testing and have become increasingly unreliable as at-home testing has increased and accessibility of clinical testing has decreased, highlighting the importance of wastewater data.

PUBLIC HEALTH SIGNIFICANCE

Results from the first year of BPHC’s program underscore the importance of city-specific and neighborhood-level wastewater epidemiology as a supplement to measuring trends at larger spatial scales. Despite widespread population immunity during the study period, citywide wastewater levels were strongly correlated with and provided critical lead time to increases in hospitalizations and deaths, consistent with previous work.11 As an early indicator of severe disease, wastewater data signal the onset of emerging COVID-19 surges and are shared to inform local interventions, including policies on masking and preparedness for health care capacity in local hospitals. However, although citywide and regional temporal trends were similar, citywide wastewater levels in Boston were consistently higher, which may indicate higher burden in Boston compared with surrounding cities and towns. Reliance on regional wastewater data alone, therefore, may not be an accurate measure of community SARS-CoV-2 infection, masking inequities if City of Boston rates are higher than those in surrounding areas.

Neighborhood-level wastewater results revealed stark inequities in community burden of SARS-CoV-2 infection. These neighborhood-level wastewater patterns were largely consistent with reported COVID-19 case rates and emergency department visits. However, in several instances, wastewater data added key information not observed in clinical data, specifically in neighborhoods where community-level SARS-CoV-2 infection is less likely to be reported or to result in severe COVID-19 (owing to, e.g., low testing rates, younger ages).

Nevertheless, the persistence of social and environmental inequities, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, underscores the need for equitable implementation of wastewater epidemiology programs.4,12 Structural barriers to health equity continue, including discriminatory housing policies and practices resulting in racialized socioeconomic segregation in the Boston area.7 BPHC’s program uniquely addresses these issues via neighborhood-level sampling so that inequities in SARS-CoV-2 infection across neighborhoods can be identified and addressed. Primarily, this community-based wastewater epidemiology program will inform mitigation strategies and reduce health inequities through neighborhood-level interventions (e.g., vaccine clinics), prioritizing neighborhoods for increased provision of personal protective equipment (e.g., high-quality masks and antigen tests) and enhancing outreach to community organizations serving residents at high risk (e.g., congregate care settings) in these neighborhoods.

We routinely report program results alongside recommendations and neighborhood-specific resources to help residents interpret and act on our findings. Given the findings that wastewater signals precede upcoming increases in clinical care requirements, BPHC uses wastewater data to inform area hospitals, government officials, and community-based organizations of impending COVID-19 surges.

This work had several limitations. We were unable to directly account for variation introduced by differences in sewer network engineering, climate, and SARS-CoV-2 evolution. Although this is likely somewhat addressed via normalizing with pepper mild mottle virus, these factors may also partially explain observed differences in SARS-CoV-2 concentrations. Additionally, because of sewerage infrastructure and resource constraints, two neighborhoods did not have sampling sites, and several covered small shares of the neighborhood populations. Future work will further examine spatiotemporal trends in wastewater and clinical indicators to assess whether wastewater data serve as a sentinel at the neighborhood level.

Our concept to practice model for a neighborhood-level wastewater-based epidemiology program measures and informs actions to mitigate inequities in community SARS-CoV-2 infection. The program’s first-year results revealed inequities between the City of Boston and the greater Boston area and between neighborhoods in the City of Boston unobservable in regional wastewater data. This program’s results will continue to inform community-based mitigation strategies to reduce health inequities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding for Boston Public Health Commission’s (BPHC’s) wastewater epidemiology program comes from the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021.

We thank the Infectious Disease Bureau, Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response, and Informatics Team at BPHC, especially Sreedevi Ravi and Tahir Arif, for their assistance with data collection and analysis of COVID-19 clinical indicators and programmatic support. We thank our partners at Boston Water and Sewer Commission for their assistance with selecting sampling sites and programmatic support and collaboration that makes the program possible. We also thank our partners at Biobot Analytics and Flow Assessment Services for their assistance with sample collection, laboratory processing, data management and analysis, and programmatic support.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

Data for this study were de-identified and collected and analyzed as part of routine public health practice and therefore did not require institutional review board oversight or approval.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boston Public Health Commission. Health of Boston 2023: the provisional mortality and life expectancy report. 2023. Available at: https://www.boston.gov/sites/default/files/file/2023/05/HOB_Mortality_LE_2023_FINAL_May12.pdf. Accessed July 8, 2024.

- 2.Njoku AU. COVID-19 and environmental racism: challenges and recommendations. Eur J Environ Public Health. 2021;5(2):em0079. 10.21601/ejeph/10999 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. How COVID-19 created a “watershed” moment for wastewater surveillance. May 13, 2022. Available at: https://publichealth.jhu.edu/2022/how-covid-19-created-a-watershed-moment-for-wastewater-surveillance. Accessed May 3, 2024.

- 4.Alonso C, Keppard B, Bates S, Cortez D, Amaya F, Dinakar K. The Chelsea Project: turning research and wastewater surveillance on COVID-19 into health equity action, Massachusetts, 2020–2021. Am J Public Health. 2023;113(6):627–630. 10.2105/AJPH.2023.30725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson LB, Ness HD, Holm RH, Smith T. Wastewater-informed digital advertising as a COVID-19 geotargeted neighborhood intervention: Jefferson County, Kentucky, 2021–2022. Am J Public Health. 2024;114(1):34–37. 10.2105/AJPH.2023.307439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Massachusetts Water Resources Authority. Wastewater COVID-19 tracking . July 5, 2024. . Available at: https://www.mwra.com/biobot/biobotdata.htm . Accessed May 3, 2024.

- 7.Arcaya MC, Ellen IG, Steil J. Neighborhoods and health: interventions at the neighborhood level could help advance health equity. Health Aff (Millwood). 2024;43(2):156–163. 10.1377/hlthaff.2023.01037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.City of Boston. Permits for street work; conditions thereof. Vol. 11-6.9. Available at: https://codelibrary.amlegal.com/codes/boston/latest/boston_ma/0-0-0-9607. Accessed May 3, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xiao A, Wu F, Bushman M, et al. Metrics to relate COVID-19 wastewater data to clinical testing dynamics. Water Res. 2022;212:118070. 10.1016/j.watres.2022.118070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolfe MK. Invited perspective: the promise of wastewater monitoring for infectious disease surveillance. Environ Health Perspect. 2022;130(5): 51302. 10.1289/EHP11151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keshaviah A, Huff I, Hu XC, et al. Separating signal from noise in wastewater data: an algorithm to identify community-level COVID-19 surges in real time. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023;120(31): e2216021120. 10.1073/pnas.2216021120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Korfmacher KS, Harris-Lovett S. Invited perspective: implementation of wastewater-based surveillance requires collaboration, integration, and community engagement. Environ Health Perspect. 2022;130(5):51304. 10.1289/EHP11191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]