Abstract

Objectives. To describe 4 unique models of operationalizing wastewater-based surveillance (WBS) for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in jails of graduated sizes and different architectural designs.

Methods. We summarize how jails of Cook County, Illinois (average daily population [ADP] 6000); Fulton County, Georgia (ADP 3000); Middlesex County, Massachusetts (ADP 875); and Washington, DC (ADP 1600) initiated WBS between 2020 and 2023.

Results. Positive signals for SARS-CoV-2 via WBS can herald a new onset of infections in previously uninfected jail housing units. Challenges implementing WBS included political will and realized value, funding, understanding the building architecture, and the need for details in the findings.

Conclusions. WBS has been effective for detecting outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 in different sized jails, those with both dorm- and cell-based architectural design.

Public Health Implications. Given its effectiveness in monitoring SARS-CoV-2, WBS provides a model for population-based surveillance in carceral facilities for future infectious disease outbreaks. (Am J Public Health. 2024;114(11):1232–1241. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2024.307785)

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) transmission spiked early in carceral populations1 because of congregate living, poor ventilation, and frequent cellblock transfers.2–4 Since before the COVID-19 pandemic, the United States has led the world in incarceration.5 Jails (short-term correctional facilities) averaged 11 million admissions yearly,6 representing 7 to 8 million individuals, when accounting for repeat admissions.7 By January 2023, COVID-19 had caused 3181 deaths in US prisons and jails.8 Surveillance and interventions to decrease COVID-19 incidence and mortality in custody populations are crucial. A safe custodial environment is a human right, and carceral health affects community health.9

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidance on the management of COVID-19 in homeless service sites and in correctional and detention facilities initially focused on individual testing, quarantine, isolation, and mitigation. Revisions added wastewater-based surveillance (WBS) as another mitigation strategy.10 WBS consists of testing wastewater to identify pathogens, which can then be linked to a population source. This surveillance strategy can act as an early warning signal and guide targeted routine diagnostic tests to identify individual cases: WBS complements individual surveillance.

Because the virus persists in fecal matter, WBS is a practical method of mass surveillance. WBS has proven useful for infections that spread rapidly or start with either no or nonspecific symptoms.11 These characteristics align with SARS-CoV-2. College dormitory studies confirmed WBS as a sensitive, low-cost, noninvasive surveillance tool for early detection of SARS-CoV-2 at an institutional level.12–15

Guidance for operationalizing WBS in carceral settings is sparse and needs to consider facility architecture (cells vs dorm rooms), size, and sewer system configuration. To evaluate the acceptability of WBS for COVID-19, we conducted qualitative studies with individuals who experienced incarceration during the COVID-19 pandemic. After finding that WBS was highly acceptable,16,17 we initiated regular WBS at Fulton County Jail (FCJ) in Atlanta, Georgia, and tested the correlation of the proportion of the population infected with SARS-CoV-2 and the level of virus in the wastewater.18 We report on the expanded operationalization of WBS at 4 US jails to demonstrate its wider feasibility and associated effectiveness outcomes.

METHODS

Four jail systems participated in this study: Cook County Jail (CCJ), Chicago, Illinois; FCJ, Atlanta, Georgia; Middlesex Jail and House of Correction (MJHOC), North Billerica, Massachusetts; and the District of Columbia Jail (DCJ), Washington, DC. Each secured funding and was willing to engage in an implementation study to assess the feasibility of WBS for SARS-CoV-2 surveillance and implementation outcomes. One or more authors participated in WBS at each site.

We explored and compared funding, starting points, jail architecture, sample collection processes, and laboratory methods.

Funding, Starting Points, and Laboratory Linkage

Our study included jails of different sizes, architectural designs, sewer system configurations, and funding levels (Table 1). Each jail used external laboratories for wastewater testing.

TABLE 1—

Preliminary Characteristics of WBS Methods Among Enrolled Jails: 4 US Jails, 2020–2024

| Jail: ADP, 2020 | Change Goal | No. of Buildings (No. of Manholes per Building) | Housing Configuration | WBS in Place? Frequency? | Private or Public Funder? Grant Recipients? | Lab for Specimens | Health Care Provider | Specificity of WW Sample to Case Location | How Has WBS Related to Individual Testing? | Championing to Sustain? | Funding Duration | Internal Data Sharing |

| CCJ: 6000 | Refinement: increase efficiency, automation, and throughput; move on to other infectious disease surveillance | 16 (1–4) | Mix of single cell units (few), 2-person cells, 4-person cells, dorms holding ∼40, 1 large 250-person dorm | Multiple (20) collection points 1–2 times/wk | Public and private funding; began with private funding by Chicago area philanthropy foundation. Replaced with funding from Chicago Department of Public Health after 1 y | University of Illinois, Chicago, IL | Public sector | Data from facilities management moderately successful; occasions of discordant results | Pinpointed site of outbreak; could limit where testing is needed (e.g., maximum-security unit) | Medical sees a need; custody also champions it; has helped set up mpox; may add influenza | Ongoing as of 2024 | Via data analyst (sheriff’s office) and infection control department |

| FCJ: 3000 | Refinement: consistent collection schedule with high throughput | 1 main/2 satellite (6 in main jail, 1 in small satellite, 2 in larger satellite) | Predominately 2-person cells | Multiple (≥ 8) collections points; once weekly | Public funder (National Institutes of Health) recipient: private business, to academic institution | Rollins School of Public Health, Atlanta, GA | Private, for-profit | Clarified during study | WBS results inform intensity of testing; individual testing less frequent when/where WW without virus | Sheriff’s office requested additional funding from department of health | Concluded | Disjointed; tried to coordinate |

| DCJ: 1600 | Introduce system: singular collection site | 2 main (4) | Predominately 2-person cells | One collection point | Public funder (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention); recipient: Department of Health | DC Department of Health, Washington, DC | Community FQHC site | Schematic map available | Pilot phase | Yes; DC Department of Health is using the experience of employing granular data in schools to inform jail WBS | Ongoing as of 2024 | Data shared internally with department of health |

| MJHOC: 825 | Sustain collection: explore expanding to more than 1 collection point | 1 main (1) | Mix of single cell units, 2-person cells; dorms holding ∼60 persons | Single collection point once a week with a 2-d turnaround | County funded through the sheriff’s office annual budget | Biobot Analytics, Cambridge, MA | Hybrid model; health services are provided by a contracted vendor and in-house public sector health care employees | Not applicable | Viral load monitored by health services | Initiative of sheriff’s office | Concluded in midyear of 2024 | Data shared internally weekly |

Note. ADP = average daily population; FQHC = federally qualified health center; WBS = wastewater-based surveillance; WW = wastewater. The 4 US jails were Cook County Jail (CCJ), Chicago, IL; Fulton County Jail (FCJ), Atlanta, GA; Middlesex Jail and House of Correction (MJHOC), North Billerica, MA; and the District of Columbia Jail (DCJ), Washington, DC.

CCJ in Chicago, Illinois, used a citywide project monitoring wastewater for SARS-CoV-2 starting November 2020. We included all 16 housing buildings in the CCJ compound in this project and tested them biweekly. A private, quickly mobilized funding source supported CCJ and other Chicago Department of Public Health sites. The University of Illinois at Chicago processed the specimens.

FCJ in Atlanta, Georgia, had WBS funding from federal sources via a private company. Emory University received a subcontract in 2021 to pilot test wastewater at points around the city of Atlanta. Subsequently, Emory University received another grant from a private foundation to demonstrate the efficiency of self-collected nasal swabbing of jail residents, to correlate individual testing with WBS, and to interview relevant stakeholders. Funding was time limited.

MJHOC, the smallest jail included in this study, is ranked as a medium-sized jail by national standards.19 The sheriff’s office provided funding. Biobot Analytics (Cambridge, MA) performed WBS laboratory analysis. MJHOC began weekly sampling of wastewater in April 2021 and continued to fund surveillance through the first half of 2024.

The Washington, DC, Department of Health established WBS at DCJ via federal funding in 2020. The DC Department of Health initially delayed mobilization of funds and commencement of WBS in the jail. There has been a lag in providing feedback of WBS results to jail clinicians. DC Department of Health contracted with EA/Ecological Analysts Engineering (Hunt Valley, MD) for sample collection, and the District of Columbia Public Health Lab (Washington, DC) provided analysis. Sampling at DCJ began in March 2023. Long-term surveillance is expected to continue.

Wastewater Collection and Laboratory Methods

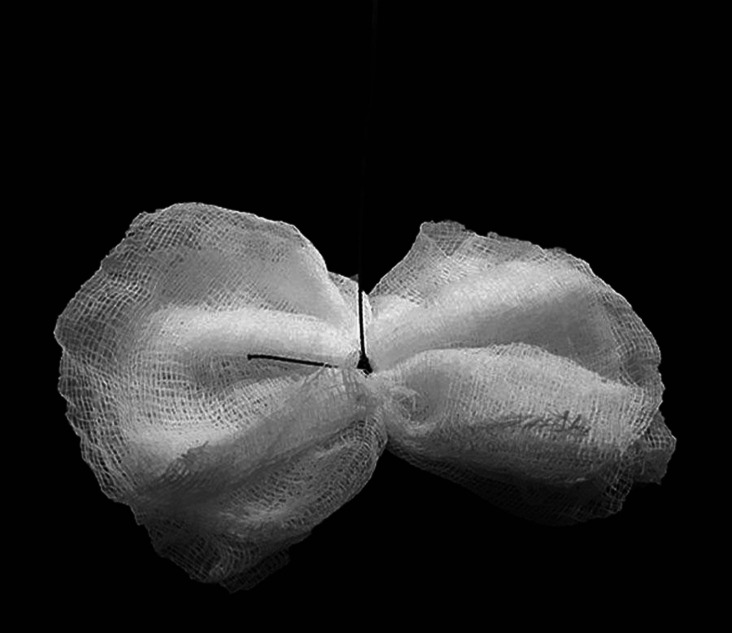

Two principal methods of wastewater sampling are grab samples and Moore swabs: a snapshot and a longitudinal measurement of viral signals, respectively. These 2 collection methods are analogous to a finger-stick blood glucose (single point) measurement and a hemoglobin A1C (period) measurement for monitoring blood glucose in diabetic patients. Moore swabs are 4″ × 4″ gauze squares made from a 48-inch–long gauze strip Z-folded to be 12 ply, then tied in the middle with a fishing line (Figure 1). These are dropped in sewer lines for 24 to 48 hours. Wastewater laboratory analysis provides a semiquantitative measurement of virus in the sample.20,21 Results are presented as cycle thresholds, which are higher with decreasing concentrations of viral RNA. This semiquantitative measurement provides a rough comparison of relative levels of virus over time. WBS can also monitor for the presence of specific gene sequences associated with new variants.20,21

FIGURE 1—

Moore Swab: A 4″ × 4″ Gauze Square, Tied Together With Fishing Line, Which Is Suspended in Wastewater for 24 Hours

Source. Saber et al.18

Operations and Jail Structure

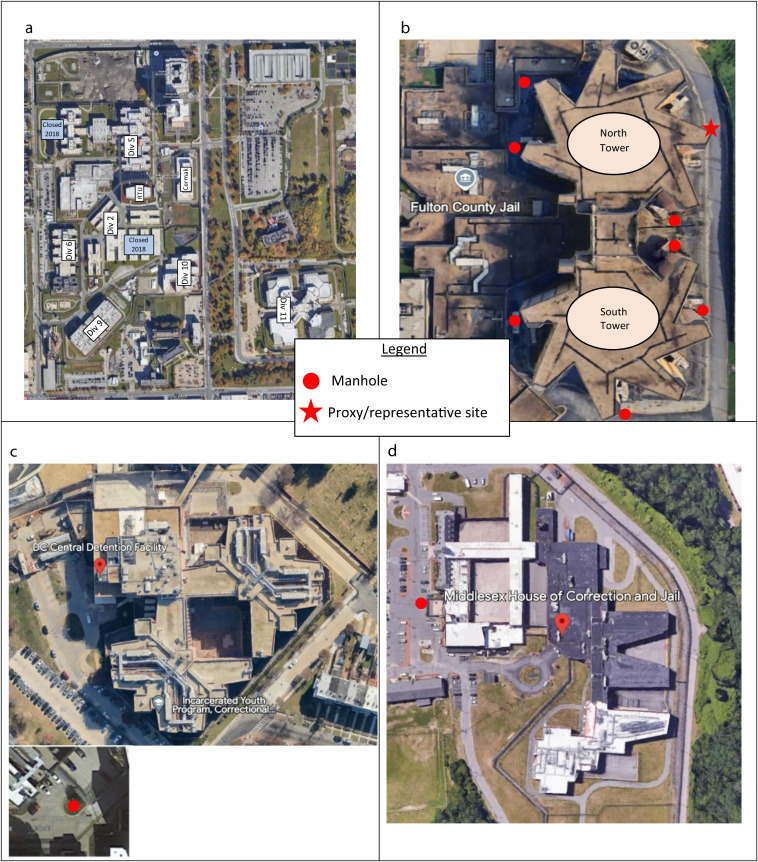

For CCJ, University of Illinois at Chicago School of Public Health researchers tested wastewater samples as part of a larger SARS-CoV-2 surveillance project with the Discovery Partners Institute (Chicago, IL).22 Testing involved collecting grab and Moore samples. We identified more than 30 possible collection sites during the initial site visit to the multibuilding CCJ complex (Figure 2). The leader of CCJ’s infection control team selected which sites to monitor weekly. Initially, 6 sites were tested biweekly, with periodic adjustments based on disease activity. Collection site selection was initially based on confirmed clinical activity or suspicion of new infections to validate the connection between wastewater readings and cases. Subsequently, the strategy shifted to focus on the areas where suspicion of infection was low to provide an early warning of new outbreaks. For buildings in which known cases were rare and the wastewater remained negative, CCJ minimized active surveillance of individuals.

FIGURE 2—

Aerial Photographs, With Locations of Housing Units and Manhole Points, of Jails in (a) Cook County, IL; (b) Fulton County, GA; (c) Middlesex County, MA; and (d) Washington, DC: 2020–2024

Note. Cook County Jail provided residential housing across 16 buildings. Each had its own wastewater-based sampling site. Specific locations are not shared because of security concerns. Proxy/representative site at Fulton County Jail represents sampling site that pools wastewater from the majority of housing sites in the jail.

For FCJ, in April 2021, the Emory University Center for Global Safe Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene performed a pilot wastewater collection at the jail. Its environmental microbiology laboratory followed the RNA extraction and real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) protocol for analyzing specimens previously used in university dorm testing.20,23 Afterward, starting in June 2021, a jail representative collected regular weekly water samples. We collected Moore swabs retrieved after 24-hour placement, grab samples of 40 mL of wastewater, or both weekly, rotating between 11 accessible manholes on the property (Figure 2b; see Supplemental Figure A [available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org] for more details on specific site processing). The semiquantitative results were reported the following day.24

The main FCJ complex consists of a 7-floor structure with 2 towers, both of which contain 6 housing units (Figure 2; Supplemental Figure B [available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org]). Initially, we could not locate FCJ’s sewage system blueprints. We poured tracer dye (EcoClean Solutions, Copiague, NY) into the plumbing system at various source locations, with study staff stationed at manholes relaying when color appeared, which gave us a preliminary indication of wastewater flow. Locating plumbing blueprints in October 2022 confirmed the findings. By early 2023, dye studies demonstrated the precise flow patterns (Supplemental Figure B). With future outbreaks of pathogens that can be tracked in wastewater, the precise origin can thus be narrowed down to a specific housing area in 1 of the towers.

At MJHOC, we sampled wastewater from the single facility manhole site weekly using an automated sampler (Figure 2).25 The commercial laboratory Biobot Analytics (Cambridge, MA) analyzed specimens and delivered the results electronically to the sheriff’s office 48 hours later. Increased viral concentrations in the wastewater prompted the infectious disease consultant and jail staff to meet to discuss enhanced individual testing and mitigation.

At the DC jail, the DC Department of Health used an automatic sampler and selected a single site for collection near the infirmary and a housing unit for mid- to long-term residents (Figure 2). At the time of this report, how DCJ would use the WBS data to inform clinical care was still under consideration.

RESULTS

We have demonstrated the feasibility of using WBS to guide dynamic COVID-19 response protocols that included resident and staff testing in the jails. Three jails used WBS to help guide clinical care.

Individual Testing Procedures

When WBS was established, the CCJ compared results with a rapid PCR (IDNow, Abbot Laboratories, Abbot Park, IL) test at intake and in the urgent care unit. To screen housing units after exposure, before medical procedures, or before prison transfer, staff collected swabs from individuals for laboratory-based PCR testing, which was performed at the John H. Stroger Jr. Hospital (Chicago, IL). Before the Omicron variant emerged, entrants were quarantined in intake housing, and PCR testing was used to clear them for transfer to the general population. This procedure was revised as CDC guidelines evolved.

FCJ conducted opt-out rapid testing of individuals at intake as well as point-of-care testing for suspected cases in the population using point-of-care antigen tests (BinaxNow, Abbot Laboratories, Chicago IL, through January 2022; then QuickVue, QuidelOrtho, San Diego, CA, from February 2022 onward). A team from Rollins School of Public Health performed periodic mass testing. The Gates Foundation suggested that random population testing be done via self-collected SteriPack nasal swabs (SteriPack USA, Lakeland, FL), collection devices for molecular diagnostic testing (Supplemental Figure C, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Before piloting this strategy, the Emory team held 3 focus groups of recently released individuals from local jails to gauge acceptability; these groups specifically endorsed this collection strategy.16

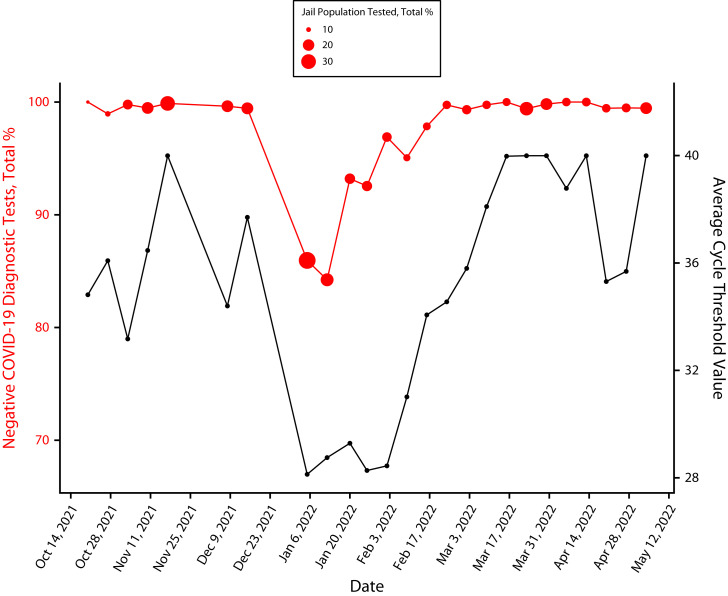

Once mass testing began, the Emory team developed a tracking system to study the relationship between SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic test positivity rates and the signal strength in wastewater.18 Specimens collected at FCJ were tested by Northwell Health Laboratory, which used an LGC Biosearch Technologies SARS-CoV-2 ultrahigh-throughput endpoint reverse transcription PCR test (Middlesex, UK) with 100% sensitivity. Jail medical staff could access results the next day. The individual test positivity rates and the cycle threshold of SARS-CoV-2 in the wastewater were correlated (Figure 3).18

FIGURE 3—

Comparison of Wastewater and Diagnostic Results With Population Percentage: Fulton County Jail, GA, 2021–2022

Source. Saber et al.18

Note. Average cycle threshold refers to the number of cycles needed to detect a florescent signal in a real-time polymerase chain reaction test as a result of detection of amplified nucleic acid (RNA or DNA). It is inversely proportional to the amount of RNA in the initial sample. With increasing percentages of negative tests (fewer people infected, less RNA) the cycle threshold increases as more cycles are required to amplify it to detectable levels.

Testing individuals for SARS-CoV-2 at MJHOC started with PCR testing in April 2020. In November 2021, PCR testing was replaced by rapid antigen testing. The DC Department of Corrections procedures for screening, isolation, and quarantine followed the CDC guidelines as they evolved.26

Adding Individual Testing

Targeted testing can follow a newly positive wastewater signal. The number of possible wastewater collection points, shown in Table 1, is proportional to the size of each jail. With 1 collection point, the readings are akin to a community viral load. However, when wastewater can be collected from multiple collection sites and the source is known to originate from a particular location in the jail, 1 or more positive signals informed the jail to consider testing where there may be highest risk of infection or spread. When positive sites were widespread, negative sites signaled where cases were not occurring and, therefore, resources could be spared. CCJ demonstrated the most progress in using WBS to locate and respond to outbreaks identified by WBS at various jail housing units. Once the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 was widespread in the community at large, wastewater was consistently positive in most buildings. This guided the jail to focus on monitoring for clinical illness through nurse-led symptom checks.

Multiple Wastewater Collection Sites

At CCJ, each manhole access point drains from a single living unit. This permitted infection control teams to plan for optimal isolation housing configurations and identify zones that did not require targeted testing. In October 2021, SARS-CoV-2 was detected in the wastewater from the maximum-security living unit after prolonged negative results. At the time, no individuals were being monitored for infection. The infection control team interpreted the newly positive WBS readings as a harbinger of undetected infection in this unit. They preemptively notified custody staff that new isolation beds were necessary. Transfers out of the building halted to prevent exporting cases without proactive testing. Three days after the WBS signal appeared, clinical cases were diagnosed in the building. This early warning spared staff from scrambling for isolation beds and facilitated the prompt application of infection control measures.

Since the summer of 2021, wastewater results have been shared weekly with health care leadership at FCJ. For the entire duration of WBS, the jail population exceeded its capacity of 2688 persons, limiting their ability to isolate and quarantine infected and exposed populations. WBS spurred testing and led to isolation and quarantine as space permitted. Approaches were different during 2 periods.

Period 1 was from summer 2021 to summer 2022. In summer 2021, wastewater was clear of SARS-CoV-2 for several weeks. Health care staff identified no active cases. Later, the wastewater tested positive, preceding the detection of infected individuals in the population. Because WBS could not pinpoint which housing units had infected individuals, mass testing occurred beginning October 2021. This supplemented ongoing, opt-out antigen testing of entrants and symptomatic individuals. Throughout 2022, the team increasingly understood the source of cases leading to positive wastewater sites (Supplement B).

Period 2 began in fall 2022. Locating the jail’s blueprints (Supplements A and B) permitted the Emory team to map plumbing lines. There are 42 housing units in the north tower and 36 in the south tower. Sewer mapping helped narrow down the source site to 7 housing units (or 14 in the case where 2 spokes of a tower drained into 1 site). The week of October 17, wastewater was positive in the North 5 manhole but negative at North 6, prompting screening in units 500 and 600 of the north tower. A cluster of 4 cases was found on the second floor of the north tower in the 500-housing block and no cases in the latter.

DISCUSSION

As jails around the country ramped up WBS for SARS-CoV-2, we learned that facilities of different sizes found WBS effective for monitoring new outbreaks. We have described 4 jail systems that established WBS systems and used the results to mitigate outbreaks. The average daily population of these jails varied widely, from less than 1000 to several thousand individuals, affording a view of WBS operations across a broad range of jail average daily population sizes (Table 1). Each of these programs had unique, innovative approaches to WBS; they also had challenges to overcome, such as funding issues that delayed the Washington, DC, rollout.

WBS can indicate the emergence of infection after a period of no activity. In CCJ, we observed a lead time on identification of an emerging outbreak, which allowed advance preparation of mitigation practices. The duration of lead time can change with SARS-CoV-2 variants. This effect of a lead time was observed in CCJ, a large jail, and in MJHOC, a smaller one, in August 2021, with the emergence of the Delta strain of SARS-CoV-2 (Supplement D, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). This highlights that WBS can serve as an early warning system for disease detection in multiple jail settings. WBS also functions as a collective signal on behalf of individuals who are unable or reluctant to self-report or self-identify because of barriers faced in jail (e.g., difficulty accessing health services, stigma, mistrust of providers, concerns surrounding isolation).

In larger jails, with multiple collection points corresponding to separate housing units, WBS may offer the added benefit of knowing where to focus, conserving resources. In CCJ, results streamlined resource use by indicating the areas without virus. These areas did not require surveillance testing or advance preparation of quarantine or isolation beds. Conversely, when a jail lacked these features (e.g., MJHOC), mass testing became necessary. Nevertheless, WBS still gave a lead time, which enabled a quicker response.

In jails with numerous prospective collection points but limited knowledge of the source living unit, a delineating step may be introduced. FCJ demonstrated the usefulness of dye testing to confirm wastewater flow, which consequently led to more accurate localization of infections and targeted nasal testing. MJHOC and DCJ used automatic samplers for obtaining samples for WBS. The advantage of this technology is more regulated, periodic sampling of the wastewater, removing the need to use Moore swabs.

When WBS indicates infection, a strategy of focused testing can enhance case-finding efficiency. However, administering an increased volume of individual tests may be labor intensive. In its protocol for follow-up individual testing, FCJ demonstrated that numerous nasal swabs could be collected quickly using barcode scanning to register specimens. The process for developing this strategy for FCJ is discussed in Supplement C. We believe that combining automatic sampling and establishing clear links between collection sites and housing units for precise infection locations will be the most favorable future practice.

We discovered that, aside from jail size, each site’s architectural features had implications for WBS. Configurations of jails varied from a collection of independent buildings, towers with multiple wings, and a singular structure. Each configuration posed different challenges. One such challenge was access to critical points of the drainage lines and interpretation of results obtained from such sites. CCJ had housing units in separate smaller buildings, making it easier to access points in the drainage system that corresponded to separate housing units (each manhole access point drains from a single living unit), compared with the high towers of FCJ. FCJ had a complex interconnecting drainage system that had some drains flowing into others. A knowledge of the direction of flow was also needed to interpret which housing units were associated with positive results from manholes. The pattern of which manholes yielded wastewater suggestive of SARS-CoV-2 indicated the locations of infection (Supplement B). Across the project, residents were housed in dorms, double occupancy cells, single occupancy cells, or mixed housing. Diversity in housing is important to consider when planning testing and other mitigation strategies.

A fundamental component underlying successful implementation of WBS in jails is support from various stakeholders, which will be the focus in future steps of our study. Across the country, early attitudes toward SARS-CoV-2 case finding varied. They ranged from withholding testing of asymptomatic persons, even with known exposure,27 to aggressive identification of all cases and transparently posting results.28 Cooperation between entities included interjail cooperation and communication between custody officials and respective medical operations.

FCJ and MJHOC operated with contracted medical vendors that approved surveillance activity. External jail support included close relationships between jail staff and academic institutions, such as the University of Illinois in Chicago, Emory University, Montefiore Medical Center/Albert Einstein College of Medicine, and Tufts University. Funding entities made study activities possible, as WBS was not yet considered standard population-level surveillance practice. Former jail residents were important to implementing the surveillance project, as their participation was necessary for calibrating individual testing logistics. The diversity represented in our study’s stakeholders was key to its success. Increased participation and awareness between different entities strengthened the process overall.

Our study results suggest that WBS could be a useful population-level system for other emerging infectious diseases, such as mpox, polio, and tuberculosis. Wastewater was archived at CCJ and FCJ starting in May 2022 at the onset of the mpox outbreak. Validation of mpox detection in wastewater has since been demonstrated.29 CCJ observed 2 confirmed cases of mpox30 but did not detect the virus in the weekly wastewater samples archived from the same period. Reasons for missing mpox virus in the wastewater could include waning viral shedding by the day that virus was collected. CCJ has also used WBS for influenza, respiratory syncytial virus, and hepatitis A.

WBS opens the possibility of surveillance for noninfectious agents, such as opioids and other illicit drugs.31 Detection of substances in a sample representing the aggregate of the jail wastewater can provide public health data on what substances are present. Determining the precise location to narrow the search to a single housing unit could lead to an individual’s entrapment. Opinions of persons with lived experience of incarceration, correctional medicine experts, and others are mixed: some support such a move; others believe it may erode residents’ trust in WBS programs. Although targeted searches could save resources and better prevent overdose-associated morbidity and mortality, it could lead to associating WBS with punishment rather than health promotion.

We have demonstrated that WBS can serve as an early warning system for disease detection in carceral settings. Its potential to assist corrections and public health agencies with outbreak mitigation is enormous. The application needs to be thoughtful, and input from a wide range of stakeholders, including those with lived experience of incarceration, could be useful when deciding its scope. Supplemental Figure E (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) provides a flowchart on operationalizing WBS using lessons learned in this project. With all voices at the table planning its implementation, the new technology could change the landscape of infection control in carceral settings and other congregate environments.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by the Gates Foundation (grant INV-035562, 64986), the Walder Foundation, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and a National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics Underserved Populations Program cooperative agreement (U01 DA056000) with Emory University).

We extend our thanks to all participating jails’ sheriff’s offices and collaborating institutions.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

A. J. Wurcel has received funding from the Massachusetts Sheriff Association. C. J. Zawitz has received funding from serving on Gilead Sciences Speaker’s Bureau. M. J. Akiyama reports grants from NIDA, NIH (K99/R00 DA043011; DP2 DA053730), the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (R01 MD016744), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (P30 AI124414), and investigator-initiated funding paid to his institution from Gilead Sciences and Abbvie. A. C. Spaulding has received in the past 3 years funding through her university from Health Resource Services Administration and Health Through Walls, and internal funding from Emory University. She has personally received consulting fees from the Medical Association of Georgia and funding for travel from the Infectious Disease Society of America.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

The study described in this article did not constitute human participant research according to criteria followed by the Emory University institutional review board.

See also Holm and Smith, p. 1156.

REFERENCES

- 1.Marusinec R, Brodie D, Buhain S, et al. Epidemiology of coronavirus disease 2019 at a county jail—Alameda County, California, March 2020–March 2021. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2022;28(1):50–59. 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lofgren ET, Lum K, Horowitz A, Mabubuonwu B, Meyers K, Fefferman NH. Carceral amplification of COVID-19: impacts for community, corrections officer, and incarcerated population risks. Epidemiology. 2022;33(4):480–492. 10.1097/EDE.0000000000001476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Network characteristics and visualization of COVID-19 outbreak in a large detention facility in the United States—Cook County, Illinois, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(44): 1625–1630. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6944a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 B. 1.617. 2 (Delta) variant infections among incarcerated persons in a federal prison—Texas, July–August 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(38):1349–1354. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7038e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Institute for Crime & Justice Policy Research. World prison brief. Available at: https://www.prisonstudies.org. Accessed December 2, 2023.

- 6.Minton TD, Zeng Z. Jail inmates in 2020—statistical tables. December 14, 2021. Available at: https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/jail-inmates-2020-statistical-tables#additional-details-0. Accessed August 29, 2022.

- 7.Spaulding AC, Seals RM, Page MJ, Brzozowski AK, Rhodes W, Hammett TM. HIV/AIDS among inmates of and releasees from US correctional facilities, 2006: declining share of epidemic but persistent public health opportunity. PLoS One. 2009;4(11):e7558. 10.1371/journal.pone.0007558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.UCLA Law. COVID behind bars data project. Available at: https://uclacovidbehindbars.org. Accessed November 2, 2022.

- 9.Akiyama MJ, Spaulding AC, Rich JD. Flattening the curve for incarcerated populations—COVID-19 in jails and prisons. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(22): 2075–2077. 10.1056/NEJMp2005687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidance on management of COVID-19 in homeless service sites and in correctional and detention facilities. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/homeless-correctional-settings.html. Accessed January 30, 2024.

- 11.Daughton CG. Wastewater surveillance for population-wide COVID-19: the present and future. Sci Total Environ. 2020;736:139631. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Betancourt WQ, Schmitz BW, Innes GK, et al. COVID-19 containment on a college campus via wastewater-based epidemiology, targeted clinical testing and an intervention. Sci Total Environ. 2021;779:146408. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.146408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gibas C, Lambirth K, Mittal N, et al. Implementing building-level SARS-CoV-2 wastewater surveillance on a university campus. Sci Total Environ. 2021;782:146749. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.146749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris-Lovett S, Nelson KL, Beamer P, et al. Wastewater surveillance for SARS-CoV-2 on college campuses: initial efforts, lessons learned, and research needs. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(9):4455. 10.3390/ijerph18094455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karthikeyan S, Nguyen A, McDonald D, et al. Rapid, large-scale wastewater surveillance and automated reporting system enable early detection of nearly 85% of COVID-19 cases on a university campus. mSystems. 2021;6(4):e0079321. 10.1128/msystems.00793-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.González-Montalvo MDM, Dickson PF, Saber LB, et al. Opinions of former jail residents about self-collection of SARS-CoV-2 specimens, paired with wastewater surveillance: a qualitative study rapidly examining acceptability of COVID-19 mitigation measures. PLoS One. 2023;18(5): e0285364. 10.1371/journal.pone.0285364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riback LR, Dickson P, Ralph K, et al. Coping with COVID in corrections: a qualitative study among the recently incarcerated on infection control and the acceptability of wastewater-based surveillance. Health Justice. 2023;11(1):5. 10.1186/s40352-023-00205-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saber LB, Kennedy SS, Yang Y, et al. Correlation of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater and individual testing results in a jail, Atlanta, Georgia, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2024;30(suppl 1):S21. 10.3201/eid3013.230775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeng Z, Minton TD. Census of jails, 2005–2019—statistical tables. October 2021. Available at: https://www.ojp.gov/library/publications/census-jails-2005-2019-statistical-tables. Accessed April 22, 2023.

- 20.Liu P, Ibaraki M, VanTassell J, et al. A sensitive, simple, and low-cost method for COVID-19 wastewater surveillance at an institutional level. Sci Total Environ. 2022;807(pt 3):151047. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.151047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen Y, Chen L, Deng Q, et al. The presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the feces of COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol. 2020;92(7):833–840. 10.1002/jmv.25825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Owen C, Wright-Foulkes D, Alvarez P, et al. Reduction and discharge of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in Chicago-area water reclamation plants. FEMS Microbes. 2022;3:xtac015. 10.1093/femsmc/xtac015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.VanTassell J, Raymond J, Wolfe MK, Liu P, Moe C. Wastewater sample collection—Moore swab and grab sample methods. Available at: https://www.protocols.io/view/wastewater-sample-collection-moore-swab-and-grab-s-81wgb6djnlpk/v1. Accessed August 29, 2022.

- 24.Sablon O, VanTassell J, Raymond J, Wolfe MK, Liu P, Moe C. Nanotrap KingFisher concentration/extraction & MagMAX KingFisher extraction protocol. Available at: https://www.protocols.io/view/nanotrap-kingfisher-concentration-extraction-amp-m-bp2l61ke5vqe/v1.2021. Accessed August 28, 2024.

- 25.Curtis A. Middlesex Sheriff’s Office using wastewater analysis to monitor for COVID. Available at: https://www.lowellsun.com/2021/05/10/middlesex-sheriffs-office-using-wastewater-analysis-to-monitor-for-presence-of-coronavirus-at-facility. Accessed August 28, 2024.

- 26.Epting ME, Pluznik JA, Levano SR, et al. Aiming for zero: reducing transmission of COVID-19 in the D.C. Department of Corrections. Available at: https://einstein.elsevierpure.com/en/publications/aiming-for-zero-reducing-transmission-of-coronavirus-disease-2019. Accessed August 28, 2024.

- 27. Rankin W. Lawsuit alleges Clayton Jail indifferent to pandemic spread. Atlanta Journal Constitution. Available at: https://www.ajc.com/news/atlanta-news/lawsuit-alleges-clayton-jail-indifferent-to-pandemic-spread/6UWIHUL3UZCVPGVUMJYXTWDIAY . Accessed 7 December 2022. .

- 28. California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. Population COVID-19 tracking . Available at: https://www.cdcr.ca.gov/covid19/population-status-tracking . Accessed December 7, 2022. .

- 29.Wolfe MK, Yu AT, Duong D, et al. Use of wastewater for mpox outbreak surveillance in California. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(6):570–572. 10.1056/NEJMc2213882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Monkeypox case investigation—Cook County Jail, Chicago, Illinois, July–August 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(40):1271–1277. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7140e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Dyken E, Thai P, Lai FY, et al. Monitoring substance use in prisons: assessing the potential value of wastewater analysis. Sci Justice. 2014;54(5): 338–345. 10.1016/j.scijus.2014.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]