The decrease in cigarette smoking among American youths is one of the great public health triumphs of the present century. Yet, few people are talking about it. Public health agencies and tobacco control organizations mention it, if at all, in passing. Media coverage is minimal. Should we not be shouting it from the mountaintops?

THE REMARKABLE DECLINE IN YOUTH SMOKING

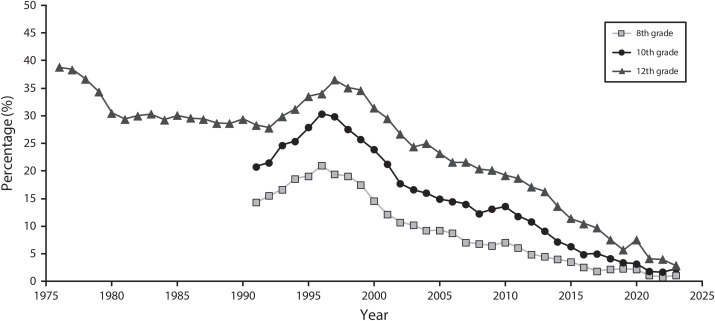

In 2023, 1.9% of US high school students and 1.1% of middle school students reported smoking cigarettes at least once in the past 30 days.1 Past-30-day smoking prevalence among 12th graders rose through the 1990s to 36.5% in 1997, a level from which it fell virtually annually thereafter. Smoking among 10th and 8th graders peaked in 1996 at 30.4% and 21%, respectively, before also decreasing nearly every year (Figure 1; https://bit.ly/4cM1hD2).

FIGURE 1—

30-Day Prevalence of Cigarette Smoking in 8th, 10th, and 12th Grade: United States, 1976–2023

Source. Miech et al.2

Past-30-day smoking includes everything from puffing on a cigarette once to smoking daily. Regarding the latter, in 1997, 24.6% of 12th graders—one of every four high school seniors—smoked every single day. Last year? It was 0.7%—one of every 143 seniors (https://bit.ly/4cM1hD2).

Youth cigar smoking has plummeted as well. Past 30-day use of cigars dropped from 11.3% of high school students in 2011 to 1.8% in 2023. Middle school cigar use was 1.1%, down from 3.7%.1,3

By any measure, youth smoking has nearly ceased to exist.

CAUSES OF THE DECREASE IN YOUTH SMOKING

How did we get here? The principal answer is a major change in social norms. Over time, smoking shifted from desirable, or at least acceptable, to a sizable subset of youths to universally undesirable and unacceptable. Policy changes4 supported social norm change: clean indoor air laws, prohibition of ads attractive to young people, effective counteradvertising, and cigarette price increases.

The last of these reflects a combination of tax increases and industry-imposed wholesale price increases. The latter, exceeding general inflation in recent years, are of particular interest. With young people especially price sensitive,4 industry’s increasing prices indicate that they may be giving up their age-old pursuit of “replacement smokers,” the newly smoking young people who replaced older customers who quit smoking or died. The increased prices likely mean that the industry is focusing on the near-term goal of extracting maximal revenue from their heavily addicted middle-aged and older customers.

The public health community has been fighting youth smoking for decades. Why, therefore, are we not celebrating what is essentially the demise of smoking by adolescents?

PUBLIC PERCEPTIONS OF TOBACCO AND NICOTINE

Several reasons come to mind. One is concern about youth tobacco use in all its forms. In 2023, 10% of middle and high school students had used any tobacco product in the past 30 days.1 While less than half the rate in 2019 (23%),5 this prevalence still represents a consequential proportion of students. Anyone concerned about youth tobacco product use may consider the demise of smoking per se only a step in the right direction. This is especially true for the many people, including public health professionals, who believe that smokeless products are as dangerous as smoking.

Survey data demonstrate the extent of this belief. In 2017, the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) asked respondents, “Do you believe that some smokeless tobacco products, such as chewing tobacco and snuff, are less harmful than cigarettes?” Seventy-one percent answered “No.” Only 13.4% answered “Yes” (https://bit.ly/4dGiZJv). Similarly, the 2020 HINTS asked respondents to compare electronic cigarettes with conventional cigarettes, and 62.2% perceived e-cigarettes to be as harmful as, or more harmful than, smoking. Only 11.2% considered e-cigarettes less harmful (https://bit.ly/3Z4N8hp). A recent survey of physicians found that “More than 60% … believed all tobacco products to be equally harmful.”6

In fact, smokeless tobacco products sold in the United States create substantially less risk than does smoking.7–9 And authoritative bodies have characterized e-cigarettes as significantly less dangerous than combusted tobacco products (https://bit.ly/4cRRdIJ; https://bit.ly/3Mxn9aB).10 Smokeless tobacco products and e-cigarettes have many fewer toxins than does cigarette smoke (https://bit.ly/479xMKc).10 Furthermore, for toxins the products have in common, yields tend to be much higher for cigarettes.11,12 Smoking is responsible for nearly all tobacco-related disease and death. The Surgeon General urged us to keep our eyes on the prize: the elimination of the use of combusted tobacco products.13 With kids, that elusive prize has been won.

A second reason we are not celebrating that victory is that all tobacco products contain nicotine, an addictive drug, and public health professionals and the general public understandably abhor adolescent nicotine use in any form. Adolescent exposure to nicotine per se is a genuine concern for several reasons, ranging from the psychological effects of dependence to the economic consequences (significant expenditures on tobacco products) to concerns that it may foster use of other drugs.14,15 But conflating the issue of nicotine addiction with the presumed disease-producing equivalence of all tobacco products creates the expectation that addiction will lead to substantial risk of morbidity and mortality. Nicotine per se is not the direct cause of the diseases associated with tobacco. Rather, it causes persistent use of the products that expose users to the actual toxins.

Unfortunately, surveys find that the public views nicotine as a principal culprit in smoking-produced disease. In the 2019 HINTS, 56.5% of respondents agreed that “nicotine in cigarettes is the substance that causes most of the cancer caused by smoking.” Only 21.4% disagreed (https://bit.ly/4e1zn7l). Large majorities of physicians incorrectly believe that “nicotine, on its own,” is the direct cause of smoking-associated heart disease, respiratory disease, and cancer.16

THE SPECIAL CASE OF E-CIGARETTES

Nowhere have worries about adolescents using tobacco products and risking nicotine addiction played out more vividly than in the case of e-cigarettes. E-cigarettes gained popularity among adolescents a decade ago, leading to the JUUL-inspired leap in youth vaping in 2018 and 2019, widely labeled an epidemic. Especially because, unlike cigarette smoking, many adolescents from highly educated, affluent families tried vaping,17 the state of alarm among parents reached Red Alert. Youth vaping has declined substantially since then, from 30-day prevalence of 27.5% in high school students in 201918 to 7.8% this year (https://bit.ly/4d9c5LJ). But the anxiety persists.

Worries about youth vaping focus on two issues. One is the contention that nicotine can damage developing adolescent brains or harm health in other ways. Most research regarding brain effects is based on animal models but with potential relevance for humans.14,19 However, the lack of evidence of brain damage in previous generations of people who smoked mitigates this concern. Regarding other serious long-term adverse health consequences, use of e-cigarettes is too recent to know.

The second concern is that vaping can cause nicotine addiction. While warranted, evidence indicates that vaping-induced addiction may be less pervasive than commonly assumed.20 Much adolescent e-cigarette use is experimental and transitory. Furthermore, frequent vaping, the behavior most consistent with addiction, is far more common among adolescents who either smoke or used to smoke and hence may have become nicotine dependent from their smoking. In 2022, 9% of never-smoking high school students had vaped in the past 30 days, 3% frequently (≥ 20 days). In contrast, 54% of ever-smoking students had vaped in the past 30 days, 34% frequently (https://bit.ly/3MqB4iY). Still, that 3% of never-smoking students vape frequently is a legitimate source of concern.

So, too, is the possibility that vaping has sustained, or even increased, the level of youth nicotine dependence compared with what it was when cigarettes were the principal source of addiction. Daily use of a nicotine product likely indicates addiction. In 2013, just before adolescent uptake of e-cigarettes, 8.5% of high school seniors smoked cigarettes daily. In 2019—the peak year of youth vaping—that rate was 2.4%, falling to 0.7% in 2023. The prevalence of daily vaping by 12th graders in 2019 was 11.6%, dropping to 5.8% in 2023.2 The sum of daily smokers and daily vapers totaled 14% in 2019 and 6.5% in 2023. Thus, daily use of these products increased from the year before vaping to vaping’s peak year. It then decreased by nearly 60% to the present. This measure of likely nicotine addiction dropped by a quarter over the decade from before vaping to 2023, and today’s source of likely addiction, e-cigarettes, is substantially less dangerous than was the product in 2013, combustible cigarettes.

Even so, to many observers, worries regarding e-cigarettes have supplanted concerns about youth cigarette smoking. For anyone with this view, vaping’s perceived perils may make celebrating the demise of youth smoking seem unwarranted.

THE LEGACY OF THE DISAPPEARANCE OF YOUTH SMOKING

But is it really? Just over 100 years ago, a medical professor told his students, observing the autopsy of a lung cancer victim, that they were unlikely to ever see this then extraordinarily rare disease again.21 Today, lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in both men and women, with smoking responsible for 80% to 90% of cases. The near disappearance of smoking among today’s young people means that a few decades hence, lung cancer is likely to be a relatively minor cause of cancer. Deaths from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease—80% attributable to smoking—will likely fall as well, as may age-adjusted heart disease mortality.

THE LOGICAL—AND CRUCIAL—NEXT STEP

The rapid and nearly complete disappearance of adolescent smoking is arguably the single most dramatic, and ultimately important, tobacco control achievement to date. Next on the docket is the elimination of adult smoking. Like youth smoking, adult smoking has declined substantially, albeit more slowly, to 11.5%. The benefits of the decrease are uneven, however. Reductions in smoking by younger adults have driven the decline. Smoking has not decreased among older adults, the group most at risk for near-term illness and death.22 Twenty-eight million Americans smoke, and cigarettes continue to claim 480 000 lives every year.23 Furthermore, the overall 11.5% prevalence masks significant disparities in prevalence and mortality. Increasingly, smoking’s victims are society’s marginalized groups—people with lower income and education, those suffering from mental health problems, Indigenous people, and sexual and gender minoritized groups.24 Having essentially eliminated youth smoking, it is time to focus attention on reducing adult smoking25—the prize in tobacco control, according to the Surgeon General.

In the process, and perhaps as a model of success, let us celebrate the near elimination of cigarette smoking among our young people. They will live longer, healthier lives than their parents and grandparents.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author has no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Birdsey J, Cornelius M, Jamal A, et al. Tobacco product use among US middle and high school students—National Youth Tobacco Survey, 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(44): 1173–1182. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7244a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miech RA, Johnston LD, Patrick ME, O’Malley PM. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2023: overview and detailed results for secondary school students. Monitoring the Future Monograph Series. Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan. Available at: https://monitoringthefuture.org/results/annual-reports. Accessed June 16, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang TW, Gentzke A, Sharapova S, Cullen KA, Ambrose BK, Jamal A. Tobacco product use among middle and high school students—United States, 2011–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(22):629–633. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6722a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warner KE. Tobacco policy research: insights and contributions to public health policy. In: Warner KE, ed. Tobacco Control Policy. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2006:3–86. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang TW, Gentzke AS, Creamer MR, et al. Tobacco product use and associated factors among middle and high school students—United States, 2019. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2019;68(12):1–22. 10.15585/mmwr.ss6812a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delnevo CD, Jeong M, Teotia A, et al. Communication between US physicians and patients regarding electronic cigarette use. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(4):e226692. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.6692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fisher MT, Tan-Torres SM, Gaworski CL, et al. Smokeless tobacco mortality risks: an analysis of two contemporary nationally representative longitudinal mortality studies. Harm Reduct J. 2019;16(1):27. 10.1186/s12954-019-0294-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Accortt NA, Waterbor JW, Beall C, Howard G. Chronic disease mortality in a cohort of smokeless tobacco users. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156(8):730–737. 10.1093/aje/kwf106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levy DT, Mumford EA, Cummings KM, et al. The relative risks of a low-nitrosamine smokeless tobacco product compared with smoking cigarettes: estimates of a panel of experts. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13(12):2035–2042. 10.1158/1055-9965.2035.13.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2018. 10.17226/24952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Majeed B, Linder D, Eissenberg T, Tarasenko Y, Smith D, Ashley D. Cluster analysis of urinary tobacco biomarkers among US adults: Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) biomarker study (2013‒2014). Prev Med. 2020;140:106218. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goniewicz ML, Smith DM, Edwards KC, et al. Comparison of nicotine and toxicant exposure in users of electronic cigarettes and combustible cigarettes. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(8):e185937. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.5937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK179276. Accessed September 16, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kandel ER, Kandel DB. A molecular basis for nicotine as a gateway drug. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(10):932–943. 10.1056/NEJMsa1405092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lau L, Conti AA, Hemmati Z, Baldacchino A. The prospective association between the use of e-cigarettes and other psychoactive substances in young people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2023;153:105392. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2023.105392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bover Manderski MT, Steinberg MB, Wackowski OA, Singh B, Young WJ, Delnevo CD. Persistent misperceptions about nicotine among US physicians: results from a randomized survey experiment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(14):7713. 10.3390/ijerph18147713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simon P, Camenga DR, Morean ME, et al. Socioeconomic status and adolescent e-cigarette use: the mediating role of e-cigarette advertisement exposure. Prev Med. 2018;112:193–198. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.04.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cullen KA, Gentzke AS, Sawdey MD, et al. e-Cigarette use among youth in the United States, 2019. JAMA. 2019;322(21):2095–2103. 10.1001/jama.2019.18387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leslie FM. Unique, long-term effects of nicotine on adolescent brain. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2020;197:173010. 10.1016/j.pbb.2020.173010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson SE, Brown J, Jarvis MJ. Dependence on nicotine in US high school students in the context of changing patterns of tobacco product use. Addiction. 2021;116(7):1859–1870. 10.1111/add.15403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blum A. Alton Ochsner, MD, 1896‒1981, anti-smoking pioneer. Ochsner J. 1999;1(3):102–105. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meza R, Cao P, Jeon J, Warner KE, Levy DT. Trends in US adult smoking prevalence, 2011 to 2022. JAMA Health Forum. 2023;4(12):e234213. 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2023.4213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le TTT, Mendez D, Warner KE. New estimates of smoking-attributable mortality in the US from 2020 through 2035. Am J Prev Med. 2024;66(5):877–882. 10.1016/j.amepre.2023.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balfour DJK, Benowitz NL, Colby SM, et al. Balancing consideration of the risks and benefits of e-cigarettes. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(9): 1661–1672. 10.2105/AJPH.2021.306416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Califf RM, King BA. The need for a smoking cessation “care package.” JAMA. 2023;329(3):203–204. 10.1001/jama.2022.24398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]