Abstract

The activation of yes‐associated protein 1 (YAP1) and transcriptional co‐activator with PDZ‐binding motif (TAZ) has been implicated in both regeneration and tumorigenesis, thus representing a double‐edged sword in tissue homeostasis. However, how the activity of YAP1/TAZ is regulated or what leads to its dysregulation in these processes remains unknown. To explore the upstream stimuli modulating the cellular activity of YAP1/TAZ, we developed a highly sensitive YAP1/TAZ/TEAD‐responsive DNA element (YRE) and incorporated it into a lentivirus‐based reporter cell system to allow for sensitive and specific monitoring of the endogenous activity of YAP1/TAZ in terms of luciferase activity in vitro and Venus fluorescence in vivo. Furthermore, by replacing YRE with TCF‐ and NF‐κB‐binding DNA elements, we demonstrated the applicability of this reporter system to other pathways such as Wnt/β‐catenin/TCF‐ and IL‐1β/NF‐κB‐mediated signaling, respectively. The practicality of this system was evaluated by performing cell‐based reporter screening of a chemical compound library consisting of 364 known inhibitors, using reporter‐introduced cells capable of quantifying YAP1/TAZ‐ and β‐catenin‐mediated transcription activities, which led to the identification of multiple inhibitors, including previously known as well as novel modulators of these signaling pathways. We further confirmed that novel YAP1/TAZ modulators, such as potassium ionophores, Janus kinase inhibitors, platelet‐derived growth factor receptor inhibitors, and genotoxic stress inducers, alter the protein level or phosphorylation of endogenous YAP1/TAZ and the expression of their target genes. Thus, this reporter system provides a powerful tool to monitor endogenous signaling activities of interest (even in living cells) and search for modulators in various cellular contexts.

Keywords: cell‐based screening, highly sensitive reporter system, Hippo‐YAP1/TAZ pathway, lentivirus, YAP1/TAZ modulators

In this report, a lentivirus‐based reporter cell system using a highly sensitive YAP1/TAZ/TEAD‐responsive DNA element was established. This system provides a versatile tool for assessing the endogenous YAP1/TAZ activity and exploring their novel modulators.

Abbreviations

- IL‐1β

interleukin‐1β

- IRAK4

interleukin‐1‐receptor‐associated kinase 4

- LATS

large tumor suppressor homolog kinases

- NF‐κB

nuclear factor‐κB

- TAZ

transcriptional co‐activator with PDZ‐binding motif

- TCF

T‐cell factor

- YAP1

yes‐associated protein 1

- YRE

YAP1/TAZ/TEAD‐responsive DNA element

1. INTRODUCTION

The Hippo pathway is critical for controlling organ size, tumor suppression, and tissue regeneration in flies and mammals. 1 Its primary role is to inhibit the transcription co‐activators, YAP1 and transcriptional TAZ, by phosphorylation. The unphosphorylated form of YAP1/TAZ is translocated into the nucleus, where it associates with the TEAD family of transcription factors, which are the predominant functional partners, to elicit the expression of a wide range of genes that promote cell growth, proliferation, and survival. 2 In mice, the hyperactivation of YAP1/TAZ forced by the YAP transgene or deletion of upstream Hippo components such as neurofibromin 2, mammalian STE20‐like kinases, adapter protein Salvador homolog1, LATS, and Mps one binder kinase activator‐1 triggers the formation of various types of tumors, thereby demonstrating that YAP1/TAZ and Hippo components function as potent oncoproteins and tumor‐suppressors, respectively. 3 YAP1/TAZ accumulate in most cancers and their increased levels are associated with poor prognosis and therapeutic resistance in various cancers, such as gastric, esophageal, urogenital, pleural mesothelial, ovarian, and skin cancers, thus highlighting them as noteworthy targets for cancer therapy. 3 , 4 However, despite the high levels of YAP1/TAZ in these cancers, genetic mutations in Hippo components and YAP1/TAZ are not frequently observed, implying that some kind of stress or signaling in the tumor microenvironment may significantly regulate them.

In addition to the tumorigenic activities of YAP1/TAZ, they play a pivotal role in tissue repair and organ regeneration. Upon organ injury, the activation of YAP1 is specifically initiated in regenerating cells in the liver, intestine, neonatal heart, and lungs, which subsequently terminates upon completion of regeneration, 5 implying that the YAP1/TAZ activity is strictly controlled by the surroundings of the injury during these processes. Conditional depletion of YAP1/TAZ resulted in reduced cell proliferation and retarded or impaired recovery from injured tissues in the liver, intestine, heart, lungs, and skin, in an organ‐specific manner, 6 indicating a significant contribution of YAP1/TAZ to the regeneration of various organs. Moreover, although most adult organs exhibit limited regeneration after injury, artificial hyperactivation of YAP1/TAZ by means of transgenes or depletion of upstream Hippo components expedites regeneration in the liver, intestine, heart, and lungs. 5 Thus, the role of YAP1/TAZ as a promoter of regeneration highlights the possibility that artificially controlled activation of YAP1/TAZ may provide an attractive therapeutic strategy for tissue recovery in these organs.

Numerous studies aimed at understanding the molecular basis of upstream regulators of the Hippo pathway have revealed that Hippo components and YAP1/TAZ are context‐dependently modulated by external and internal stimuli as diverse as cytoskeleton‐mediated mechanical force, cell polarity, cell adhesion, cellular energy stress, endoplasmic reticulum stress, genotoxic stress, hypoxia, and other signaling pathways including receptor tyrosine kinase‐mediated, integrin‐Src, G protein‐coupled receptor, and Wnt signaling, 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 thereby demonstrating that the activities of YAP1/TAZ respond in a versatile manner to a variety of cellular inputs. However, it remains unclear which upstream stimuli specifically direct the activity of YAP1/TAZ in regeneration or tumorigenesis, the so‐called maintenance or disruption of tissue homeostasis.

In this study, we aimed to develop a highly sensitive YRE, and then use it to construct a lentivirus‐based reporter system with the ability to monitor the endogenous activity of YAP1/TAZ in various types of human cells. Taking advantage of this system, we aimed to perform reporter screening of an inhibitor library and identify various signal inhibitors and stress inducers that could serve as modulators of the endogenous activity of YAP1/TAZ. We hope that the assay system developed in this study will help identify therapeutic targets for antitumor agents and regenerative medicine.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

The materials and methods concerning plasmids, preparation of lentivirus, Dual‐Luciferase® assay, screening using Screening Committee for Anticancer Drug (SCAD) kits, cell culture, quantitative PCR (qPCR), western blotting, MTT assay, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay are detailed in Document S1. The sequences of oligonucleotide used for plasmid construction, qPCR and siRNA are described in Table S1. The list of chemical inhibitors in SCAD kit 1, 2, 3, and 4 is given in Table S2.

3. RESULTS

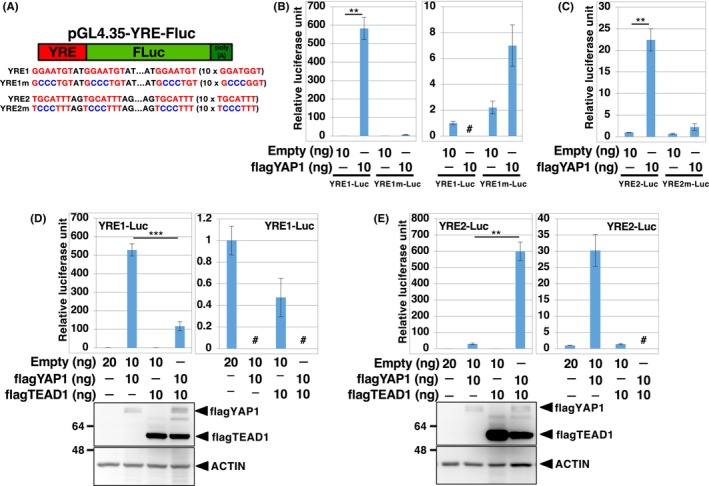

3.1. Evaluation of TEAD‐dependent YREs

TEAD transcription factors, the major binding partners of YAP1/TAZ, are known to recognize multiple TEAD‐binding motifs following DGHATNT (IUPAC codes for nucleotides: N = A, T, C, or G; D = A, T, or G; H = A, T, or C). 13 , 14 , 15 Moreover, it has been shown that direct double motifs with a 2‐bp spacer are enriched in many YAP1/TAZ‐binding sites and implicated in the cooperative binding of TEAD to DNA as a dimer. 13 , 16 , 17 , 18 To generate sensitized YREs, we utilized a typical TEAD‐binding motif (GGAATGT) in various target genes such as MCAT, CTGF, and ANKRD1 15 , 19 and a putative TEAD‐binding motif (TGCATTT) in the Sox2 gene 20 to construct reporter DNAs, as the expression of these genes has been shown to be strongly upregulated upon YAP1 overexpression. 15 , 17 , 20 , 21 We generated luciferase reporter genes under the control of two YREs and their mutants, in which there were 10 direct tandem repeats of TEAD‐binding motifs (10× GGAATGT: YRE1‐Luc, 10× GCCCTGT: YRE1m‐Luc, 10× TGCATTT: YRE2‐Luc, and 10× TCCCTTT: YRE2m‐Luc) with a 2‐bp spacer, and assessed their activities in response to exogenous YAP1 (Figure 1A). In HEK293T cells, YRE1‐Luc exhibited more striking activation by YAP1 alone than YRE2‐Luc and 8×GTIIC‐Luc, 22 a conventional TEAD reporter DNA containing eight typical TEAD‐binding motifs (8xGGAATGT) (Figure S1A), whereas YRE1m‐Luc and YRE2m‐Luc displayed a significant loss in their response (Figure 1B,C). Additionally, we tested another TEAD‐binding motif (CATTCCT) 23 and generated a third YRE reporter, which contained 10 direct tandem repeats of almost the reverse complement sequence of YRE1 (YRE3‐Luc: 10× CATTCCT) with a 2‐bp spacer (Figure S1B) and confirmed that YRE3‐Luc, similar to YRE1‐Luc, showed high sensitivity in its response to YAP1 (Figure S1C). Interestingly, the co‐expression of TEAD1 or TEAD4 with YAP1 resulted in the inhibition of YRE1‐Luc (Figure 1D and Figure S2A), but synergistic activation of YRE2‐Luc (Figure 1E and Figure S2B). Thus, the activity of TEAD proteins seems to be suppressive or synergistic with that of YAP1 depending on their binding motifs.

FIGURE 1.

YRE1‐Luc is highly sensitive to YAP1. (A) Sequences of YREs and their mutants. The sequences of the two YREs and their mutants were inserted into pGL4.35, a firefly reporter plasmid, to generate YRE1‐Luc, YRE2‐Luc, YRE1m‐Luc, and YRE2m‐Luc. (B–E) HEK293T cells seeded into a 96‐well plate were transfected with 19 ng of YRE‐Luc and 1 ng of pRL‐TK. The transfected cells were cultured for 24 h, following which Dual‐Luciferase® analysis was performed. In the right‐hand panels of (B, D, and E) the bars marked # have been removed to allow for a more quantitative comparison of the other bars. The bottom panels of (D) and (E) represent western blot analyses from the same set of experiments to compare the protein expression levels of the transfected DNAs. The empty pCS2‐flag construct containing no insert was used as a negative control. Data were normalized to the activity of the empty construct, which was set to 1. The data are representative of three independent experiments and have been presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001, analyzed using the t‐test.

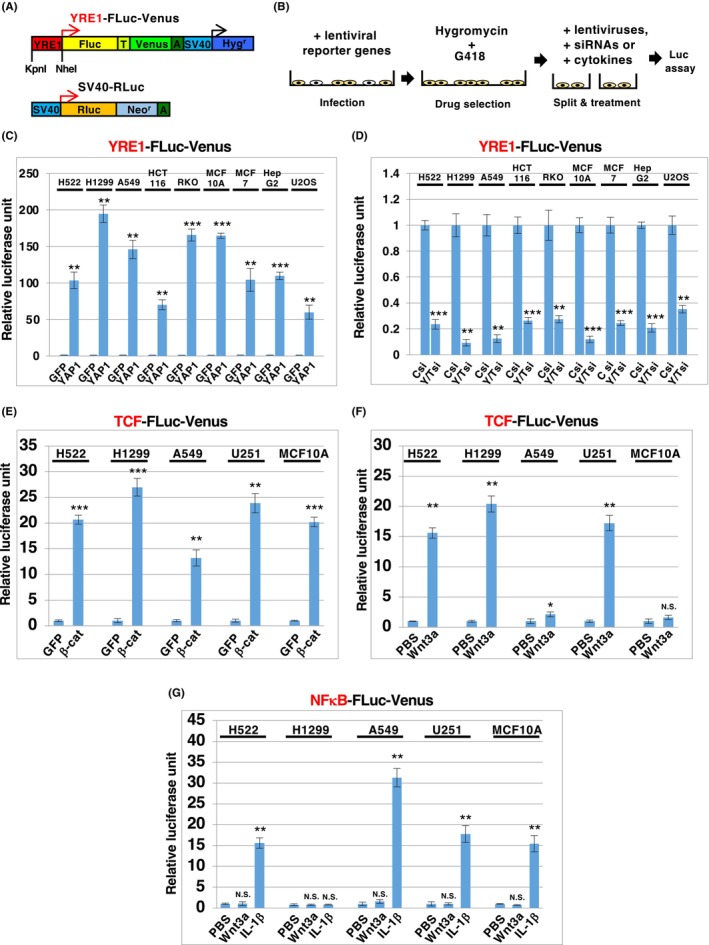

3.2. Generation of a YRE1‐dependent lentiviral reporter system

To obtain a highly sensitive YAP1/TAZ/TEAD‐responsive reporter gene applicable to various human cells, we generated a hygromycin‐selective lentiviral reporter system in which firefly luciferase binds to the T2A peptide and the Venus fluorescent protein is under the control of YRE1 (YRE1‐Fluc‐Venus) (Figure 2A). To normalize the experimental variation in the Dual‐Luciferase® assay, we constructed another lentiviral reporter expressing the Renilla luciferase‐neomycin fusion protein under the control of the constitutive SV40 promoter (SV40‐hRluc) (Figure 2A). The human cell lines were simultaneously infected with YRE1‐Fluc‐Venus and SV40‐hRluc, cultured in the presence of hygromycin and G418 for drug selection, and split into experimental groups for the Dual‐Luciferase® assay (Figure 2B). We observed that YRE1‐Fluc‐Venus exhibited strong activation of luciferase in response to re‐infection with the YAP1 lentivirus in multiple human cell lines, including lung cancer (H522, H1299, and A549), colon cancer (HCT116 and RKO), mammary gland epithelial (MCF10A), breast cancer (MCF7), liver cancer (HepG2), and osteosarcoma (U2OS) cells (Figure 2C). Importantly, reporter activation in cells cultured at low density was blocked by the depletion of YAP1/TAZ with siRNAs (Figure 2D), indicating that this reporter system specifically monitors the endogenous activity of YAP1/TAZ. In addition, there is a unique site for restriction enzymes, KpnI and NheI, at both ends of the YRE1 element in YRE1‐Fluc‐Venus, so that YRE1 can be replaced with other DNA‐binding motifs (Figure 2A). To further confirm the applicability of this reporter system to other signaling pathways, such as Wnt/β‐catenin‐ and interleukin (IL)‐1‐mediated signaling, we constructed TCF‐Fluc‐Venus and NF‐κB‐Fluc‐Venus, respectively, which contain TCF‐ and NF‐κB‐binding motifs, respectively, and performed Dual‐Luciferase® assays in H522, H1299, A549, and MCF10A cells, and the glioma cell line U251. TCF‐Fluc‐Venus was activated by β‐catenin in all cells and by the Wnt3a ligand in H522, H1299, and U251 cells, although it did not respond to the Wnt3a ligand in A549 and MCF10A cells, probably because of the lack of signaling components of the Wnt/β‐catenin pathway in these cells (Figure 2E,F). On the other hand, NF‐κB‐Fluc‐Venus was highly sensitive to IL‐1β, a ligand of the IL‐1 receptor/NF‐κB‐mediated signaling pathway, but not to Wnt3a in these cells (Figure 2G), confirming that reporter activation is dependent on the DNA‐binding motif. Moreover, not only did the depletion of β‐catenin block the activation of TCF‐Fluc‐Venus by Wnt3a in U251, but also that of IRAK4, 24 a key component of the IL‐1 receptor pathway, and suppress the IL‐1β‐induced activation of NF‐κB‐Fluc‐Venus in U251 (Figure S3A–C), further supporting the notion of signal‐specific response of these reporter genes. Thus, this drug‐selective lentiviral reporter system allowed us to assess the specific signal transduction mediated by YAP1/TAZ, β‐catenin, and NF‐κB in a variety of human cells that could be infected with lentiviruses.

FIGURE 2.

The lentiviral‐mediated reporter system developed can be applied for the quantification of YAP1‐, β‐catenin‐ and NFκB‐mediated signaling pathways in various human cells. (A) Structures of lentiviral constructs for YRE1‐FLuc‐Venus and SV40‐RLuc. In YRE1‐Fluc‐Venus, the firefly luciferase (Fluc) linked to the Venus protein by a T2A sequence (T) with polyA (A) and hygromycin resistance gene (Hygr) were under the control of the YRE1 and SV40 promoters, respectively. YRE1‐FLuc‐Venus contains unique restriction enzyme sites for KpnI and NheI. YRE1 in YRE1‐FLuc‐Venus was replaced at KpnI and NheI with seven direct tandem repeats of TCF‐binding sites (TCF‐FLuc‐Venus) or five direct tandem repeats of NFκB‐binding sites (NFκB‐FLuc‐Venus). SV40‐RLuc, a construct for normalization of the Dual‐Luciferase® analysis, contains Renilla luciferase (RLuc) fused with the neomycin resistance gene (Neor), under the control of the SV40 promoter (B). YRE1‐FLuc‐Venus (C and D), TCF‐FLuc‐Venus (E and F), and NFκB‐FLuc‐Venus (G) were introduced into human cells together with SV40‐RLuc, by means of lentiviral infection. Human cells infected with lentiviral reporter genes were cultured in the presence of hygromycin and G418 for 5–7 days and then split into experimental groups in 96‐well plates (~10,000 cells/well). The split cells were treated with lentivirus (C, E), siRNA (D), or cytokines (F, G). Human cells treated with lentiviruses or siRNA for 12 h were cultured for 2 days, following which Dual‐Luciferase® analysis was performed. Human cells treated with cytokines such as 100 ng/mL Wnt3a or 10 ng/mL IL‐1β for 24 h were subjected to Dual‐Luciferase® analysis. Data were normalized to the activity of negative controls (GFP, Csi, and PBS), which were set to 1. The data are representative of three independent experiments and presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and N.S., not significant, analyzed using t‐test. Y/Tsi, mixture of YAP1 and TAZ siRNA; Csi, control siRNA; β‐cat, β‐catenin; IL‐1β, interleukin‐1β.

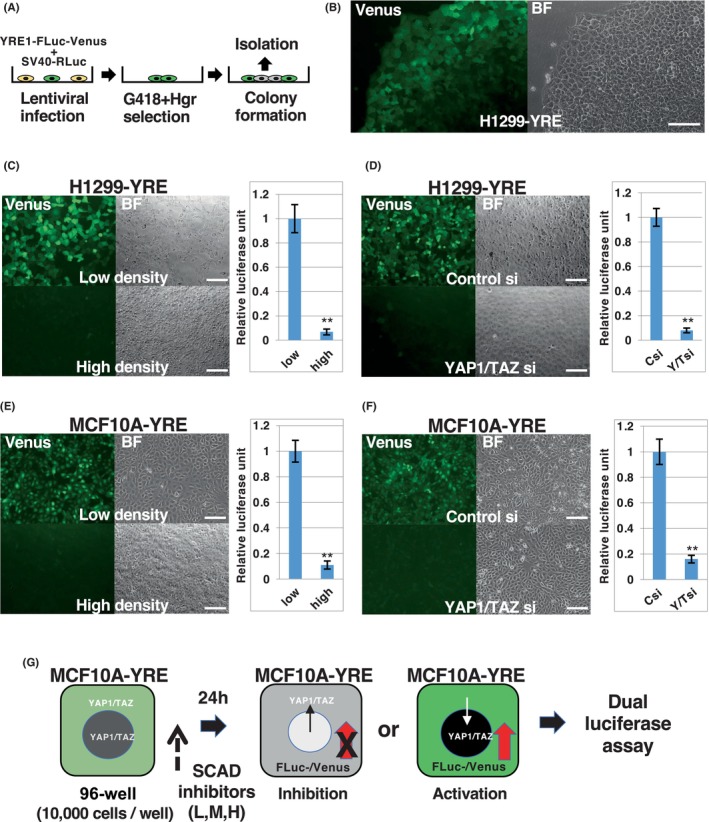

3.3. Establishment of YRE1 reporter‐introduced human cell lines displaying endogenous YAP1/TAZ activity

To investigate whether YRE1‐Fluc‐Venus could detect endogenous YAP1/TAZ activity in living cells, H1299 cells infected with YRE1‐Fluc‐Venus and SV40‐Rluc were subsequently subjected to colony formation from single cells (Figure 3A). Many colonies showed marginal expression of Venus (Figure 3B), whereas some showed ubiquitous expression, even in the central region (Figure S4). The expression pattern of Venus in the former colonies was expected to represent the endogenous activity of YAP1/TAZ, as the activity of YAP1/TAZ was suppressed by the Hippo pathway triggered by cell–cell contact in the center of the colony for a longer time than in the margin during colony formation. Thus, the former colonies were selected and expanded for further analysis (H1299‐YRE). As expected, Venus expression was observed in H1299‐YRE cells cultured at low density but not high density, which agrees with the luciferase activity of the same set of samples (Figure 3C). Notably, both Venus expression and luciferase activity were abolished by YAP1/TAZ siRNA in H1299‐YRE cells (Figure 3D and Figure S5A). We also established YRE1 reporter‐introduced MCF10A lines (MCF10A‐YRE) from a single cell, as MCF10A cells are non‐cancerous epithelial cells that are widely utilized for studying the Hippo pathway. Similar to H1299‐YRE, the cellular response of MCF10A‐YRE was dependent on cell density and YAP1/TAZ function (Figure 3E,F and Figure S5B). Taken together, H1299‐YRE and MCF10A‐YRE reflect the endogenous activities of YAP1/TAZ in terms of Venus fluorescence in living cells and can also be applied for quantitative assays based on luciferase activity.

FIGURE 3.

YRE1 reporter‐introduced cells from a single cell represent the endogenous activity of YAP1/TAZ in living cells. (A) Colony formation from a single cell harboring YRE1‐FLuc‐Venus and SV40‐RLuc. H1299 and MCF10A cells infected with YRE1‐FLuc‐Venus and SV40‐RLuc were plated onto a 10‐cm dish (~200 cells/dish) and cultured for 10–14 days in the presence of G418 and Hgr, to obtain colonies from a single cell transduced with the reporter genes (H1299‐YRE and MCF10A‐YRE, respectively). (B) Venus fluorescence image of a living colony. BF: bright field (right). Green fluorescence indicates Venus expression under the control of YRE1 (left). Scale bar, 100 μm. (C–F) Venus fluorescence images of H1299‐YRE and MCF10A‐YRE cells. H1299‐YRE (C) and MCF10A‐YRE (E) cells were plated into 96‐well plates at low (5000 cells/well, top) or high (50,000 cells/well, bottom) density and cultured for 2 days. H1299‐YRE (D) and MCF10A‐YRE (F) cells were plated into 96‐well plates (10,000 cells/well), transfected with siRNA as indicated for 12 h, and cultured for 2 days. Luciferase assays were performed using the same set of experiments (C–F, right panels). Data from the luciferase assay were normalized to the activity of controls (low, Csi) set to 1 and represented as mean ± SD (n = 3). **p < 0.01; analyzed using t‐test. Scale bars, 100 μm. (G) First screening using the SCAD inhibitor kits. MCF10A‐YRE or U251‐TCF was plated onto 96‐well plates (10,000 cells/well) and treated with inhibitors from SCAD kits [MCF10A‐YRE: 1 μM (H), 50 nM (M), and 2.5 nM (L); U251‐TCF: 1 μM (H) and 100 nM (H)] for 24 h, following which Dual‐Luciferase® assay was carried out. The screening was repeated to select compounds that reproducibly showed less than one‐third inhibition or more than 3‐fold activation in comparison to that observed in the DMSO‐treated cells. The list of chemical inhibitors in SCAD kit‐1, ‐2, ‐3, and ‐4 is given in Table S2. Hgr, hygromycin.

3.4. Identification of chemical inhibitors modulating the activity of YAP1/TAZ and β‐catenin using SCAD inhibitor kits

Next, to confirm the utility of this reporter system and explore chemical inhibitors that can modulate endogenous YAP1/TAZ activity, we screened SCAD inhibitor kits consisting of 364 known compounds (Table S2). MCF10A‐YRE cells cultured at medium density in 96‐well plates were treated with 1 μM (Figures S6, S8, S10, and S12), 50 nM (Figures S7, S9, S11, and S13), and 2.5 nM (Tables 1 and 2) of each compound for 24 h, and then analyzed using Dual‐Luciferase® assay (Figure 3G). In agreement with previous reports on the YAP1/TAZ regulation by various signaling pathways, 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 multiple compounds, including the Src family (damnacanthal, PP2, AG957, nilotinib, imatinib mesylate, and dasatinib), ataxia‐telangiectasia mutated (ATM) (ATM/ataxia‐telangiectasia and Rad3‐related kinase inhibitor, ATM kinase inhibitor), Aurora (Aurora kinase inhibitor II, III, ENMD‐2076, and MLN8237), phosphoinositide 3‐kinase (LY294002 and wortmannin), and mammalian target of rapamycin (rapamycin, temsirolimus, and everolimus) suppressed the YAP1/TAZ‐dependent reporter activation (Table 1), thus validating the effectiveness of this screening. This initial screening also suggests that several potassium ionophores (valinomycin, nigericin, and bafilomycin A1 32 ) may be novel inhibitors of the transcriptional activity of YAP1/TAZ. In contrast, distinct JAK (JAK Inhibitor I and JAK3 Inhibitor VI), platelet‐derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR; SU11652 and AG1296), and cyclin‐dependent kinase (Cdk1/2 inhibitor III and kenpaullone) inhibitors facilitated the reporter gene in addition to heat shock protein 90 inhibitors (17‐AAG and radicicol), which are a known activator of YAP1/TAZ that deplete LATS proteins (Table 2). 33 Notably, multiple DNA/RNA synthesis inhibitors, also known as genotoxic stress inducers, such as actinomycin D (DNA/RNA polymerase inhibitor), camptothecin (topoisomerase I inhibitor), and daunorubicin (topoisomerase II inhibitor) were also likely activators for TEAD‐dependent transcription.

TABLE 1.

YAP/TAZ inhibitors from SCAD kits.

| Compounds | SCAD no. a | Category | Working concentrations for inhibition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paclitaxel | kit‐1 2A | Stabilization of microtubule assembly | 1 μM, 50 nM |

| Damnacanthal | kit‐1 8B | Lck (p56), Src family inhibitor | 1 μM |

| PP2 | kit‐3 8E | Lck inhibitor, Src family inhibitor | 1 μM |

| AG957 | kit‐1 3F | Bcr‐Abl inhibitor, Src family inhibitor | 1 μM |

| Nilotinib | kit‐4 2B | Bcr‐Abl inhibitor, Src family inhibitor | 1 μM, 50 nM |

| Imatinib mesylate | kit‐4 2F | Bcr‐Abl/Kit inhibitor, Src family inhibitor | 1 μM |

| Dasatinib | kit‐4 3D | Bcr‐Abl/Src inhibitor | 50 nM |

| ATM/ATR kinase inhibitor | kit‐3 1G | ATM inhibitor | 1 μM |

| ATM kinase inhibitor | kit‐3 1H | ATM inhibitor | 1 μM |

| Aurora kinase inhibitor II | kit‐3 2B | Aurora inhibitor | 1 μM |

| Aurora kinase inhibitor III | kit‐3 2C | Aurora inhibitor | 1 μM |

| ENMD‐2076 | kit‐4 9C | Aurora inhibitor | 1 μM |

| MLN8237 | kit‐4 9D | Aurora inhibitor | 1 μM, 50 nM |

| Rotenone | kit‐2 7C | mitochondrial complex I inhibitor | 1 μM |

| Oligomycin | kit‐2 2C | F1‐ATPase inhibitor | 1 μM |

| Bafilomycin A1 | kit‐2 2D | V‐ATPase inhibitor, K ionophore | 1 μM, 50 nM, 2.5 nM |

| Monensin | kit‐2 4F | Na ionophore | 1 μM, 50 nM |

| Valinomycin | kit‐2 5D | K ionophore | 1 μM, 50 nM, 2.5 nM |

| Nigericin | kit‐2 5E | K ionophore | 1 μM, 50 nM |

| Thapsigargin | kit‐2 6E | Ca‐ATPase inhibitor | 1 μM, 50 nM, 2.5 nM |

| LY294002 | kit‐1 10D | PI3K inhibitor | 1 μM |

| Wortmannin | kit‐1 10E, kit‐3 10C | PI3K inhibitor | 1 μM |

| Rapamycin | kit‐1 9D | p70 S6K inhibitor, mTOR inhibitor | 1 μM, 50 nM |

| Temsirolimus | kit‐4 2D | mTOR inhibitor | 1 μM |

| Everolimus | kit‐4 3E | mTOR inhibitor | 1 μM |

| Cdk4 inhibitor | kit‐3 4A | CDK inhibitor | 1 μM |

| Staurosporine | kit‐1 11A | PKC, PKA, PKG, MLCK inhibitor | 50 nM, 2.5 nM |

| KN‐93 | kit‐3 2G | CAMKII inhibitor | 1 μM |

| Cantharidin | kit‐1 11D | PP2A | 1 μM |

| AG1478 | kit‐1 5E | EGFR inhibitor | 1 μM |

| AG1024 | kit‐1 7D, kit‐3 7C | IGF‐IR inhibitor | 1 μM |

| Crizotinib | kit‐4 6G | EML4‐ALK inhibitor | 1 μM |

| Pazopanib | kit‐4 3F | Multi‐kinase inhibitor | 1 μM |

| U‐0126 | kit‐3 8H | MEK inhibitor | 1 μM |

| Orlistat | kit‐4 7A | Lipase inhibitor | 1 μM |

| S2101 (LSD1 inhibitor II) | kit‐4 7G | LSD1 inhibitor | 1 μM |

| NS‐398 | kit‐1 4H | COX‐2 | 1 μM |

| FH535 | kit‐4 5A | Wnt inhibitor | 1 μM |

| TWS119 | kit‐4 11C | GSK‐3 inhibitor | 1 μM |

List of chemical inhibitors in SCAD kit‐1, kit‐2, kit‐3, and kit‐4 is described in Table S2.

TABLE 2.

YAP/TAZ activators from SCAD kit.

| Compound | SCAD no. a | Category | Working concentrations for activation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daunorubicin, HCl | kit‐1 2C | Topoisomerase II inhibitor | 1 μM |

| Actinomycin D | kit‐1 2F | DNA RNA polymerase inhibitor | 50 nM, 2.5 nM |

| Camptothecin | kit‐1 2G | Topoisomerase I inhibitor | 1 μM |

| 17‐AAG | kit‐1 7C | HSP90 inhibitor | 1 μM |

| Radicicol | kit‐3 11G | Hsp90 inhibitor | 1 μM |

| Glibenclamide | kit‐2 5A | K channel inhibitor | 1 μM |

| Cdk1/2 inhibitor III | kit‐3 3F | CDK inhibitor | 50 nM |

| Kenpaullone | kit‐3 3B | CDK inhibitor | 1 μM |

| JAK Inhibitor I | kit‐3 7H | Jak inhibitor | 1 μM, 50 nM |

| JAK3 Inhibitor VI | kit‐3 8A | Jak3 inhibitor | 1 μM, 50 nM |

| SU4984 | kit‐3 6B | FGFR, PDGFR inhibitor | 1 μM |

| AG1296 | kit‐3 9G | PDGFR inhibitor | 1 μM |

| SU11652 | kit‐3 9F | PDGFR inhibitor | 1 μM |

| TrkA inhibitor | kit‐3 12E | TrKA inhibitor | 1 μM |

| Axitinib | kit‐4 10C | Multi‐kinase inhibitor | 1 μM |

List of chemical inhibitors in SCAD kit‐1, kit‐2, kit‐3, and kit‐4 is described in Table S2.

Furthermore, we tested the applicability of this reporter system for other signaling pathways by using a TCF‐Fluc‐Venus‐introduced U251 cell population (U251‐TCF) and SCAD kits (Figures S14–S21), which specifically responded to the Wnt3a ligand and β‐catenin (Figure 2E,F and Figure S3B). Using the aforementioned method (Figures 2A and 3G), U251‐TCF was treated with SCAD inhibitors at concentrations of 1 μM (Figures S14, S16, S18, and S20) and 100 nM (Figures S15, S17, S19, and S21). Verification of the effectiveness of this screening system again not only revealed that many kinds of glycogen synthase kinase‐3 inhibitors activated TCF‐Fluc‐Venus in U251‐TCF cells, as expected (Table 3), but also identified ouabine, JAK3 inhibitor VI, PDGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor IV, RNA‐dependent protein kinase inhibitor, and SB218078 (Chk1 inhibitor) as novel candidates for negative or positive modulators of the Wnt/β‐catenin signaling pathway (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Modulators of β‐catenin/TCF‐dependent signaling from SCAD kit.

| Compound | SCAD no. a | Category | Working concentrations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibitors | |||

| Ouabain | kit‐2 4G | Na/K ATPase inhibitor | 1 μM, 100 nM |

| Akt Inhibitor IV | kit‐3 1C | AKT inhibitor | 1 μM |

| JAK3 Inhibitor VI | kit‐3 8A | JAK inhibitor | 1 μM |

| PDGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor IV | kit‐3 10A | PDGFR inhibitor | 1 μM |

| Activators | |||

| Kenpaullone | kit‐1 4A, kit‐3 3B | CDK/GSK inhibitor | 1 μM |

| Alsterpaullone, 2‐cyanoethyl | kit‐3 3E | CDK/GSK inhibitor | 1 μM |

| GSK‐3 inhibitor IX | kit‐3 6G | GSK inhibitor | 1 μM, 100 nM |

| 1‐Azakenpaullone | kit‐3 6H | GSK inhibitor | 1 μM |

| Indirubin‐3′‐monoxime | kit‐3 7A | GSK inhibitor | 1 μM |

| BIO | kit‐4 11B | GSK inhibitor | 1 μM |

| CT9902 | kit‐4 11D | GSK inhibitor | 1 μM |

| SB 218078 | kit‐2 7A, kit‐3 4C | Chk 1 inhibitor | 1 μM |

| PKR inhibitor | kit‐3 11B | PKR inhibitor | 1 μM |

| Axitinib | kit‐4 10C | Multi‐kinase inhibitor | 1 μM |

List of chemical inhibitors in SCAD kit‐1, kit‐2, kit‐3, and kit‐4 is described in Table S2.

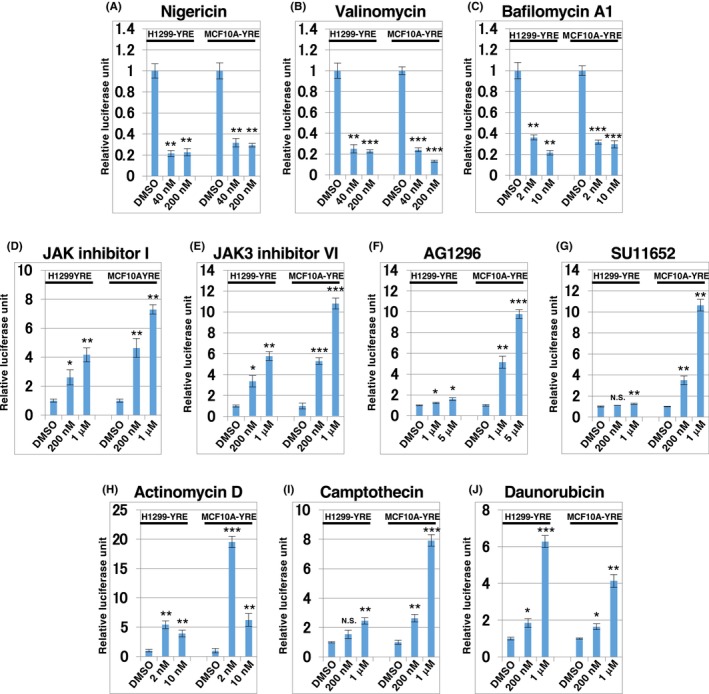

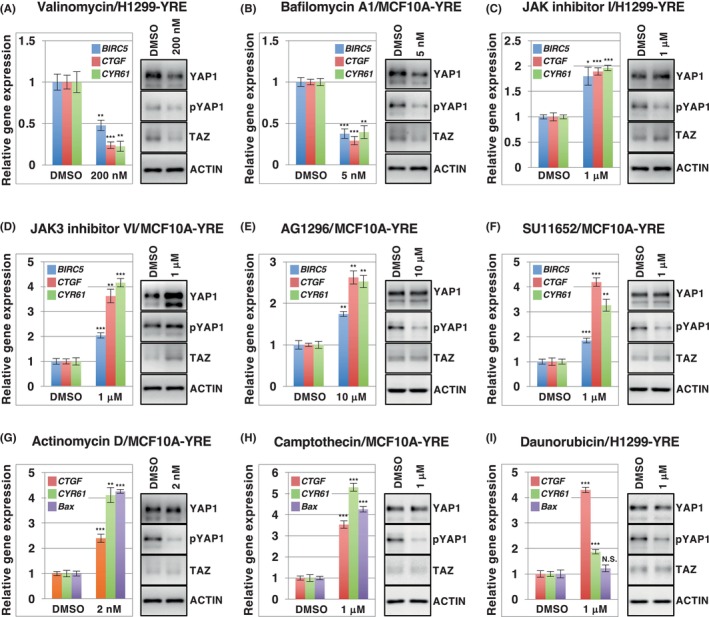

Next, to further analyze and validate the YAP1/TAZ modulators identified in the first screening, we commercially obtained nigericin, valinomycin, bafilomycin A1, JAK inhibitor I, JAK3 inhibitor VI, AG1296, Su11652, actinomycin D, camptothecin, and daunorubicin and examined the dose–response of their effect on reporter activation of H1299‐YRE and MCF10A‐YRE. Nigericin, valinomycin, and bafilomycin A1 effectively inhibited reporter activation, with only subtle effects on cell growth and viability in both cell lines (Figure 4A–C and Figure S22). In contrast, JAK inhibitor I (pan‐JAK inhibitor), JAK3 inhibitor VI (JAK3‐selective inhibitor), AG1296, and SU11652 also activated the reporter gene in a dose‐dependent manner, whereas PDGFR inhibitors had no obvious effect in H1299‐YRE cells (Figure 4D–G). In addition, actinomycin D, camptothecin, and daunorubicin, which are genotoxic stress inducers, activated TEAD‐dependent reporter genes in both the cell lines, whereas actinomycin D exhibited stronger activation of this reporter at lower doses (Figure 4H–J). Thus, the luciferase assay data demonstrated that the small compounds identified in the first screening significantly modulated the TEAD‐mediated activity of the YRE1 reporter.

FIGURE 4.

Identification of YAP1/TAZ modulators using SCAD inhibitor kits. H1299‐YRE or MCF10A‐YRE was plated onto 96‐well plates (10,000 cells/well), treated with YAP1/TAZ modulators identified in the first screening with SCAD inhibitor kits: Nigericin (A), valinomycin (B), bafilomycin A1 (C), JAK inhibitor I (D), JAK3 inhibitor VI (E), AG1296 (F), SU11652 (G), actinomycin D (H), camptothecin (I), and daunorubicin (J) for 24 h, at the doses indicated, and then analyzed by means of Dual‐Luciferase® assay. The data of the luciferase assay were normalized to the activity of the control (DMSO) set to 1. Data are representative of three independent experiments and presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; analyzed using t‐test.

3.5. Evaluation of the effects of the identified compounds on YAP1/TAZ proteins and their target genes

Next, to investigate whether the results obtained from the reporter assay correlated with the actions of the target genes and protein levels of YAP1/TAZ, we carried out qPCR analysis to determine the expression of known TEAD‐dependent target genes, such as BIRC5, CTGF, and CYR6 and western blot analysis to examine the total protein level of YAP1/TAZ and the phosphorylation of YAP (S127) to verify its negative regulation. Valinomycin and bafilomycin A1 suppressed the expression of BIRC5, CTGF, and CYR61 and protein levels of YAP1 and TAZ in both cell lines (Figure 5A,B and Figure S23A,B). In contrast, JAK inhibitor I and JAK3 inhibitor VI caused an increase in the expression of these target genes and protein levels of YAP1 and TAZ in these cells, with decreased phosphorylation of YAP1 (Figure 5C,D and Figure S23C,D). AG1296 and SU11652 also significantly enhanced the expression of the three genes in MCF10A‐YRE cells; however, they seemed to affect only the phosphorylation level of YAP1, not the amount of protein (Figure 5E,F). We also analyzed the expression of BAX, CTGF, and CYR61 in response to the genotoxic compounds actinomycin D, camptothecin, and daunorubicin (Figure 5G–I), as YAP1 has previously been shown to activate proapoptotic genes such as BAX and p53AIP1 in a p73‐dependent manner in response to other genotoxic stress inducers such as cisplatin (DNA replication inhibitor), doxorubicin (DNA/RNA polymerase and topoisomerase II inhibitor), and etoposide (topoisomerase II inhibitor). 34 , 35 Interestingly, actinomycin D and camptothecin could activate the expression of the three genes and lower YAP1 phosphorylation in MCF10A‐YRE cells (Figure 5G,H), whereas daunorubicin failed to induce BAX gene expression, even with low phosphorylation of YAP1 in H1299‐YRE cells, which lack p53 expression because of a homozygous partial deletion of TP53 gene (Figure 5I). Additionally, CYR61 expression was inhibited by YAP1/TAZ, but not by p53 depletion, in actinomycin D‐treated MCF10A‐YRE cells, indicating that YAP1/TAZ is required for CYR61 expression to be enhanced by actinomycin D. However, BAX expression showed the opposite effect under the same conditions (Figure S24), suggesting that the actinomycin D‐mediated genotoxic effect on BAX expression depends on p53, rather than on the p73/YAP1 complex in MCF10A‐YRE cells. Thus, our reporter screening system using the YRE reporter enabled the identification of several compounds from SCAD kits as novel modulators of TEAD‐dependent YAP1/TAZ function.

FIGURE 5.

The effect of YAP1/TAZ modulators on the YAP1/TAZ protein level, YAP1 phosphorylation, and expression of YAP1/TAZ target genes. H1299‐YRE and MCF10A‐YRE were treated with the indicated concentration of valinomycin (A), bafilomycin A1 (B), JAK inhibitor I (C), JAK3 inhibitor VI (D), AG1296 (E), SU11652 (F), actinomycin D (G), camptothecin (H), or daunorubicin (I) for 24 h, at the indicated doses, and subjected to the quantitative PCR analysis for known YAP1/TAZ target genes: BIRC5, CTGF, CYR61, and/or BAX (A–I, left). The cells treated with the indicated inhibitors for 12 h were analyzed by means of western blot, with antibodies against YAP1, TAZ, phosphorylated YAP1 at S127 (pYAP1), and actin (A–I, right). Data from the quantitative PCR analysis were normalized to the activity of controls (DMSO) set to 1. All data represent three independent experiments and have been presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; analyzed using t‐test.

4. DISCUSSION

We observed that YRE1 and YRE2 respond inversely to TEAD in the presence of YAP1 (Figure 1D,E and Figure S2A,B). Although YRE1 and YRE2 are artificial TEAD‐binding elements, our results imply that excess amounts of TEAD proteins for the YAP1 protein act as transcriptional repressors, as previously shown, 36 , 37 , 38 and that the sensitivity of endogenous TEAD proteins to YRE1 is possibly much higher than that to YRE2. Therefore, we selected YRE1 to generate a lentivirus‐mediated reporter gene, YRE1‐Fluc‐Venus, which can be specifically used to detect the activity of endogenous YAP1/TAZ in terms of luciferase activity. Lentivirus‐mediated gene transfer enables the stable expression of inserted genes in host cells and is widely applicable to various mammalian cells, including non‐dividing cells. Therefore, compared to the conventional transient transfection method, the measurement values of the luciferase assay in this system seem to have relatively smaller error bars in the tested cells, and the reporter‐introduced cells are usable even after multiple passages of cell culture, leading to the ease of expansion of the cell population. In addition, the presence of resistance genes for the selective antibiotics hygromycin and neomycin in YRE1‐Fluc‐Venus and SV40‐Rluc, respectively, allowed for the reporter‐incorporated cells to be selected in the presence of these antibiotics, even in cells with low efficiency of lentiviral infection. Importantly, YRE1 in the YRE1‐Fluc‐Venus construct can be replaced by other signaling DNA elements of interest at the restriction enzyme sites. The activation of TCF‐Fluc‐Venus and NFκB‐Fluc‐Venus depended on specific upstream ligands (Figure 2F,G) and downstream signal components (Figure S3B,C). Furthermore, SCAD kit screening with TCF‐Fluc‐Venus successfully identified various modulators of β‐catenin/T‐cell factor‐dependent transcriptional activity (Table 3). Thus, the reporter system we established is likely to serve as a versatile tool for assessing the signaling activity of interest in various cellular contexts and for performing large‐scale chemical screening using a high‐throughput system. Moreover, the expression of Venus fluorescence in the reporter‐transfected cell lines (H1299‐YRE and MCF10A‐YRE) from a single colony represents the endogenous activity of YAP1/TAZ in living cells, because Venus expression was detectable in the marginal region of a growing colony (Figure 3B), diminished in a highly dense culture (Figure 3C,E), and blocked upon YAP1/TAZ depletion (Figure 3D,F). Therefore, Venus fluorescence in these cells is a hallmark of YAP1/TAZ activation and facilitates real‐time measurements in living cells.

To evaluate the utility of YRE1‐Fluc‐Venus, we performed small‐scale screening using SCAD kits containing ~400 inhibitors and MCF10A‐YRE cells. The first screening identified multiple inhibitors targeting the previously known signaling pathways or novel modulators of YAP1 activity, in addition to paclitaxel, thapsigargin, and staurosporine (Tables 1 and 2), 39 , 40 , 41 guaranteeing that this cell‐based luciferase screening using MCF10A‐YRE is effective enough to select compounds that affect endogenous YAP1 activity. We also observed that actinomycin D, camptothecin, and daunorubicin activate TEAD‐dependent target genes of YAP1/TAZ in MCF10A‐YRE cells (Figures 4H–J and 5G–I, and Table 2), although previous studies reported that YAP triggers p73‐dependent expression of pro‐apoptotic gene and initiates programmed cell death in response to other genotoxic stress agents such as cisplatin, doxorubicin, etoposide, and γ‐irradiation. 8 , 34 , 35 , 42 This may be in line with previous reports as ultraviolet irradiation, cisplatin, doxorubicin, and etoposide can activate YAP to drive TEAD‐dependent genes for resisting cell death or senescence as well. 43 , 44

Oku et al. performed SCAD screening to seek YAP1/TAZ inhibitors on the basis of the nuclear localization of endogenous YAP1/TAZ and identified dasatinib, lovastatin, and pazopnib 45 ; our screening with medium‐density MCF10A‐YRE cells could identify not only the inhibitors, including dasatinib and pazopanib (Table 1), but also the activators (Table 2). However positive compounds need to be carefully selected, because the cell density after drug treatment also affects the activation of YRE1‐Fluc‐Venus. In fact, several compounds, such as baicalein (12‐lipoxygenase inhibitor), sanguinarine (Na/K/Mg ATPase inhibitor), and PD98059 (MEK inhibitor), were false positives for the YAP1/TAZ activator (Figures S9–S11), because they did not display a significant effect on YAP1/TAZ/TEAD target genes in the cells harvested at a density similar to the control. To exclude false positives, confirming cell density and Venus fluorescence in MCF10A‐YRE before the luciferase assay would be advisable. In particular, large‐scale screening requires a second validation analysis, for example, the expression of target genes, protein level of YAP1/TAZ, or sphere formation. 46

In this study, we demonstrated that a lentivirus‐based reporter cell system using YRE1‐Fluc‐Venus could identify potassium ionophores, JAK inhibitors, and PDGF inhibitors as novel modulators of YAP1/TAZ/TEAD activity. However, as the mechanisms underlying their YAP1‐modulating activity remain unknown, there is a need for future studies investigating the molecular action of these compounds in the Hippo‐YAP1/TAZ pathway. Nevertheless, the small‐scale reporter screening described herein and the much larger scope in the future for exploring compounds such as signal inhibitors and stress inducers that regulate the endogenous activity of YAP1/TAZ might offer clues for artificially controlling YAP1/TAZ activity for cancer therapy and tissue regeneration.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Hiroki Hikasa: Conceptualization; funding acquisition; investigation; project administration; validation; writing – original draft. Kohichi Kawahara: Investigation; resources; supervision; validation. Masako Inui: Investigation. Kohei Otsubo: Resources. Shojiro Kitajima: Investigation; resources. Miki Nishio: Supervision. Akira Suzuki: Conceptualization; funding acquisition; supervision; validation. Yukichika Yasuki: Formal analysis. Keita Yamashita: Formal analysis. Kazunari Arima: Formal analysis; supervision. Motoyoshi Endo: Supervision. Masanori Taira: Supervision.

FUNDING INFORMATION

JSPS KAKENHI: JP16H06276 (AdAMS) (H.H.), 18K06232 (H.H.), 21K06830 (H.H.), 23K07296 (K.K.), and 21H04806 (A.S.) AMED: Grant number 23ama221117h0002 (P‐PROMOTE, A.S.), JP24ama121052 (K.K.), JP24ym0126801 (K.K.), JP24ym0126809 (K.K.) Project Mirai Cancer Research Grants (A.S.).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

S. Akira is an editorial board member of Cancer Science. Other authors do not have a Conflict of interest. All the authors are responsible for all aspects of this article.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study was approved by the Genetic Modification Safety Committee of the University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Fukuoka, Japan (DP190003C6).

Supporting information

Figure S1.

Table S1.

Table S2.

Data S1.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Dr. Yasuhiro Mimura and Professor Hikaru Ueno for their technical support and helpful opinions. We also thank the Molecular Profiling Committee, Grant‐in‐Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas “Platform of Advanced Animal Model Support” from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan for providing us with the SCAD inhibitor kits and Inder Verma for kindly gifting us the lentiviral vectors. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI grant numbers JP16H06276 (AdAMS), 18K06232, and 21K06830 (all awarded to H.H.), 23K07296 (K.K.), and 21H04806 (A.S.), AMED grant number 23ama221117h0002 (P‐PROMOTE, A.S.), JP24ama121052 (K.K.), JP24ym0126801 (K.K.) and JP24ym0126809 (K.K.), and Project Mirai Cancer Research Grants (A.S.).

Hikasa H, Kawahara K, Inui M, et al. A highly sensitive reporter system to monitor endogenous YAP1/TAZ activity and its application in various human cells. Cancer Sci. 2024;115:3370‐3383. doi: 10.1111/cas.16316

REFERENCES

- 1. Zheng Y, Pan D. The Hippo signaling pathway in development and disease. Dev Cell. 2019;50(3):264‐282. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2019.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Currey L, Thor S, Piper M. TEAD family transcription factors in development and disease. Development. 2021;148(12):dev196675. doi: 10.1242/dev.196675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zanconato F, Cordenonsi M, Piccolo S. YAP/TAZ at the roots of cancer. Cancer Cell. 2016;29(6):783‐803. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nishio M, Maehama T, Goto H, et al. Hippo vs. Crab: tissue‐specific functions of the mammalian Hippo pathway. Genes Cells. 2017;22(1):6‐31. doi: 10.1111/gtc.12461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moya IM, Halder G. Hippo‐YAP/TAZ signalling in organ regeneration and regenerative medicine. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20(4):211‐226. doi: 10.1038/s41580-018-0086-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dey A, Varelas X, Guan KL. Targeting the Hippo pathway in cancer, fibrosis, wound healing and regenerative medicine. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020;19(7):480‐494. doi: 10.1038/s41573-020-0070-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wu H, Wei L, Fan F, et al. Integration of Hippo signalling and the unfolded protein response to restrain liver overgrowth and tumorigenesis. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6239. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Raj N, Bam R. Reciprocal crosstalk between YAP1/Hippo pathway and the p53 family proteins: mechanisms and outcomes in cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2019;7:159. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2019.00159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ma S, Meng Z, Chen R, Guan KL. The Hippo pathway: biology and pathophysiology. Annu Rev Biochem. 2019;88:577‐604. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-013118-111829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Azad T, Rezaei R, Surendran A, et al. Hippo signaling pathway as a central mediator of receptors tyrosine kinases (RTKs) in tumorigenesis. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(8):2042. doi: 10.3390/cancers12082042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wu Z, Guan KL. Hippo signaling in embryogenesis and development. Trends Biochem Sci. 2021;46(1):51‐63. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2020.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Franklin JM, Wu Z, Guan KL. Insights into recent findings and clinical application of YAP and TAZ in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2023;23(8):512‐525. doi: 10.1038/s41568-023-00579-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jiang SW, Desai D, Khan S, Eberhardt NL. Cooperative binding of TEF‐1 to repeated GGAATG‐related consensus elements with restricted spatial separation and orientation. DNA Cell Biol. 2000;19(8):507‐514. doi: 10.1089/10445490050128430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang L, Ren F, Zhang Q, Chen Y, Wang B, Jiang J. The TEAD/TEF family of transcription factor Scalloped mediates Hippo signaling in organ size control. Dev Cell. 2008;14(3):377‐387. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zanconato F, Forcato M, Battilana G, et al. Genome‐wide association between YAP/TAZ/TEAD and AP‐1 at enhancers drives oncogenic growth. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17(9):1218‐1227. doi: 10.1038/ncb3216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mahoney WM, Hong JH, Yaffe MB, Farrance IK. The transcriptional co‐activator TAZ interacts differentially with transcriptional enhancer factor‐1 (TEF‐1) family members. Biochem J. 2005;388(Pt 1):217‐225. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhao B, Ye X, Yu J, et al. TEAD mediates YAP‐dependent gene induction and growth control. Genes Dev. 2008;22(14):1962‐1971. doi: 10.1101/gad.1664408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stein C, Bardet AF, Roma G, et al. YAP1 exerts its transcriptional control via TEAD‐mediated activation of enhancers. PLoS Genet. 2015;11(8):e1005465. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Joshi S, Davidson G, Le Gras S, et al. TEAD transcription factors are required for normal primary myoblast differentiation in vitro and muscle regeneration in vivo. PLoS Genet. 2017;13(2):e1006600. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lian I, Kim J, Okazawa H, et al. The role of YAP transcription coactivator in regulating stem cell self‐renewal and differentiation. Genes Dev. 2010;24(11):1106‐1118. doi: 10.1101/gad.1903310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bora‐Singhal N, Nguyen J, Schaal C, et al. YAP1 regulates OCT4 activity and SOX2 expression to facilitate self‐renewal and vascular mimicry of stem‐like cells. Stem Cells. 2015;33(6):1705‐1718. doi: 10.1002/stem.1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dupont S, Morsut L, Aragona M, et al. Role of YAP/TAZ in mechanotransduction. Nature. 2011;474(7350):179‐183. doi: 10.1038/nature10137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mar JH, Ordahl CP. A conserved CATTCCT motif is required for skeletal muscle‐specific activity of the cardiac troponin T gene promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85(17):6404‐6408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.17.6404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jain A, Kaczanowska S, Davila E. IL‐1 receptor‐associated kinase signaling and its role in inflammation, cancer progression, and therapy resistance. Front Immunol. 2014;5:553. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Si Y, Ji X, Cao X, et al. Src inhibits the Hippo tumor suppressor pathway through tyrosine phosphorylation of Lats1. Cancer Res. 2017;77(18):4868‐4880. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sugihara T, Werneburg NW, Hernandez MC, et al. YAP tyrosine phosphorylation and nuclear localization in cholangiocarcinoma cells are regulated by LCK and independent of LATS activity. Mol Cancer Res. 2018;16(10):1556‐1567. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-18-0158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Conboy CB, Yonkus JA, Buckarma EH, et al. LCK inhibition downregulates YAP activity and is therapeutic in patient‐derived models of cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 2023;78(1):142‐152. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2022.09.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chakravarti D, Hu B, Mao X, et al. Telomere dysfunction activates YAP1 to drive tissue inflammation. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):4766. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18420-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chang SS, Yamaguchi H, Xia W, et al. Aurora a kinase activates YAP signaling in triple‐negative breast cancer. Oncogene. 2017;36(9):1265‐1275. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fan R, Kim NG, Gumbiner BM. Regulation of Hippo pathway by mitogenic growth factors via phosphoinositide 3‐kinase and phosphoinositide‐dependent kinase‐1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(7):2569‐2574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216462110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yuan P, Hu Q, He X, et al. Laminar flow inhibits the Hippo/YAP pathway via autophagy and SIRT1‐mediated deacetylation against atherosclerosis. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(2):141. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-2343-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Teplova VV, Tonshin AA, Grigoriev PA, Saris NE, Salkinoja‐Salonen MS. Bafilomycin A1 is a potassium ionophore that impairs mitochondrial functions. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2007;39(4):321‐329. doi: 10.1007/s10863-007-9095-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Huntoon CJ, Nye MD, Geng L, et al. Heat shock protein 90 inhibition depletes LATS1 and LATS2, two regulators of the mammalian hippo tumor suppressor pathway. Cancer Res. 2010;70(21):8642‐8650. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Strano S, Monti O, Pediconi N, et al. The transcriptional coactivator yes‐associated protein drives p73 gene‐target specificity in response to DNA damage. Mol Cell. 2005;18(4):447‐459. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lapi E, Di Agostino S, Donzelli S, et al. PML, YAP, and p73 are components of a proapoptotic autoregulatory feedback loop. Mol Cell. 2008;32(6):803‐814. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Koontz LM, Liu‐Chittenden Y, Yin F, et al. The Hippo effector Yorkie controls normal tissue growth by antagonizing scalloped‐mediated default repression. Dev Cell. 2013;25(4):388‐401. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.04.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Liu F, Wang X, Hu G, Wang Y, Zhou J. The transcription factor TEAD1 represses smooth muscle‐specific gene expression by abolishing myocardin function. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(6):3308‐3316. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.515817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhang W, Xu J, Li J, et al. The TEA domain family transcription factor TEAD4 represses murine adipogenesis by recruiting the cofactors VGLL4 and CtBP2 into a transcriptional complex. J Biol Chem. 2018;293(44):17119‐17134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.003608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fu W, Zhao P, Li H, et al. Bazedoxifene enhances paclitaxel efficacy to suppress glioblastoma via altering Hippo/YAP pathway. J Cancer. 2020;11(3):657‐667. doi: 10.7150/jca.38350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Liu Z, Wei Y, Zhang L, et al. Induction of store‐operated calcium entry (SOCE) suppresses glioblastoma growth by inhibiting the Hippo pathway transcriptional coactivators YAP/TAZ. Oncogene. 2019;38(1):120‐139. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0425-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ma X, Li P, Chen P, et al. Staurosporine targets the Hippo pathway to inhibit cell growth. J Mol Cell Biol. 2018;10(3):267‐269. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjy016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Levy D, Adamovich Y, Reuven N, Shaul Y. Yap1 phosphorylation by c‐Abl is a critical step in selective activation of proapoptotic genes in response to DNA damage. Mol Cell. 2008;29(3):350‐361. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lee KK, Yonehara S. Identification of mechanism that couples multisite phosphorylation of yes‐associated protein (YAP) with transcriptional coactivation and regulation of apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(12):9568‐9578. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.296954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ma K, Xu Q, Wang S, et al. Nuclear accumulation of yes‐associated protein (YAP) maintains the survival of doxorubicin‐induced senescent cells by promoting survivin expression. Cancer Lett. 2016;375(1):84‐91. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.02.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Oku Y, Nishiya N, Shito T, et al. Small molecules inhibiting the nuclear localization of YAP/TAZ for chemotherapeutics and chemosensitizers against breast cancers. FEBS Open Bio. 2015;5:542‐549. doi: 10.1016/j.fob.2015.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yang Z, Nakagawa K, Sarkar A, et al. Screening with a novel cell‐based assay for TAZ activators identifies a compound that enhances myogenesis in C2C12 cells and facilitates muscle repair in a muscle injury model. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34(9):1607‐1621. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01346-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1.

Table S1.

Table S2.

Data S1.