Abstract

Background

Postnatal care exhibits the lowest coverage levels in the obstetric continuum of care. The highest rates of maternal and newborn morbidity and mortality occur within 24 h of birth. Assessment of women in this time period could improve the detection of postpartum complications and maternal outcomes. This study determined the patterns of maternal assessment and the factors associated with postpartum complications.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study involving observations of immediate postpartum care provided to women following uncomplicated vaginal births at three health facilities in Mpigi and Butambala districts (Uganda) from November 2020 to January 2021. Data were collected using an observation checklist and a data abstraction form for maternal and newborn social demographic data. The collected data were analyzed using Stata version 14.0. Maternal assessment patterns were summarized as frequencies, and the prevalence of postpartum complications was calculated. Logistic regression analysis was performed at both bivariate and multivariate levels to identify factors associated with developing postpartum complications among these women.

Results

We observed 263 women receiving care at three health facilities in the immediate postpartum period. The level of maternal assessments was very low at 9/263 (3.4%), 29/263(11%) and 10(3.8%) within the first two hours, at three hours and at the fourth hour, respectively. The prevalence of postpartum complications was 37/263 (14.1%), with 67.6% experiencing postpartum hemorrhage (PPH), 13.5% having perineal tears, and 10.8% having cervical tears. Mothers who did not undergo a postpartum check in the first three hours (p = 0.001), those who were discharged after 24 h (p = 0.038), and those who were transferred to the postpartum ward after two hours (p = 0.001) were more likely to have developed postpartum complications.

Conclusion

The maternal assessment patterns observed in the population were suboptimal. Women who were not assessed at the third hour and those transferred after two hours to the postnatal ward were more likely to have developed postpartum complications.

Keywords: Maternal assessment, Postpartum care, Postpartum complications

Introduction

While studies have shown that the highest maternal and newborn morbidity and mortality occurs in the immediate postnatal period (within 24 h of birth), postnatal care has the poorest coverage levels in the obstetric continuum of care [1]. This makes failure to make postpartum assessments and early identification of obstetric complications a critical missed opportunity to reduce maternal mortality and morbidity [2]. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the Ministry of Health in Uganda have recently revised the guidelines for immediate postpartum care to ensure that women not only have a positive experience during this time [1, 2] but also have any complications identified and managed promptly through postpartum assessments. These guidelines include the frequency of monitoring and assessments for all postpartum women and the critical parameters that must be assessed. Midwives are required to monitor the uterine tone, vaginal bleeding, and women’s vital signs regularly, and perform a physical examination of the woman/ baby before discharge [1]. Women are required to stay at the health facility for at least 24 h after a vaginal delivery [1].

The key causes of maternal mortality, include postpartum hemorrhage, hypertensive disorders, pre-eclampsia, obstructed labour, and sepsis. These mainly present during childbirth or the immediate postpartum period [1–3]. Additionally, the leading causes of newborn mortality, which include preterm birth complications, infections, and intrapartum conditions such as asphyxia, can be identified in the immediate postnatal period [4]. Most of these are treatable and preventable if promptly recognized and good-quality care is initiated on time [5, 6].

Immediate postnatal care is the initial care trained health workers provide to women in the first 24 h following delivery [1, 2]. It should be provided at home or within a health facility depending on the place of birth or presence of complications [2]. It is recommended that postnatal care is offered to both mother and baby regularly for six weeks [1]. This is because, for every woman who dies from postpartum complications, there are 20 to 30 more who will have a more extended hospital stay and or a slower recovery after discharge due to the resulting morbidity [7, 8]. These could end up readmitted or die within the community of other related complications [9]. Despite the increase in health facility births, in many low-resource settings, 75% of mothers do not receive the adequate postnatal health checks they require or deserve. For instance, while national guidance from the Ugandan Ministry of Health (MOH) for postnatal care exists within the Uganda Clinical Guidelines, which were adopted from the WHO recommendations [10, 11], most recent estimates indicate that the provision of postpartum care is available in less than 50% of facility births making Uganda one of the worst performing countries in sub-Saharan Africa [3, 12]. There is limited data on postnatal care coverage among rural health facilities in sub-Saharan Africa, including Uganda. This is especially true regarding what postnatal assessments are available to women post vaginal delivery [12–15]. Given the lack of data regarding postpartum assessments and limited improvement in postnatal care coverage nationally, there is a need to highlight what postpartum assessments are available to women in this time period [1]. There have been some studies that reported the prevalence of postpartum maternal checks, but some used demographic health survey data, while others were based on exit interviews for women at discharge and document reviews [3, 12, 14]. These could have been limited by recall bias on the women’s side and poor documentation of care practices by the midwives.

We know that women who deliver with a skilled birth attendant are more likely to have a postpartum check compared to those who do not, yet the reported level of postpartum assessments among these women is still low [12]. It is also not clear what postpartum examinations are done and what the frequency of the postpartum assessments is because the different studies tend to have varying definitions of having a postpartum check [12]. A few studies have looked at the postpartum monitoring checks and their outcomes and reported low levels of maternal monitoring [14, 16]. A cross-sectional study on the level of postpartum examinations across sub-Saharan Africa found the level of in-facility postpartum assessments to be low, implying a reduced emphasis on postpartum care in the region [12]. In Uganda, a facility-based audit at a regional referral hospital in the eastern region also reported low levels of postpartum monitoring and that women did not receive further care after being transferred to the postnatal unit [17].

Our studies on the facility’s readiness to provide immediate postpartum care and the midwive’s perspectives about the MOH guidelines showed variations in awareness and the reported practice of postpartum monitoring [18, 19]. Often, the facilities had no written policy on immediate postpartum care, and where they had checklists for monitoring postpartum women, they were not completed appropriately. We also noted that many facilities were discharging the women before 24 h had elapsed due to various facility and individual factors [19]. It was not clear what criteria were used by the midwives to monitor the women in the immediate postpartum period and the outcomes of their assessments. In this study, we observed the postpartum assessments at three rural health facilities in Uganda to document the content of immediate postpartum care, and the prevalence of postpartum complications and associated factors among postpartum women.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

Study design

This was a cross-sectional study using quantitative methods of data collection. This design was chosen to enable the researcher assess the postpartum care (PPC) provided to the mother-baby pairs at the three health facilities selected at a given point in time. There was minimal information on the content of PPC the women receive and the factors associated with postpartum complications in the two districts [3].

Study settings

The study was conducted at 3 health facilities namely; Mpigi Health Centre IV, Gombe, and Nkozi hospitals. These were located in Mpigi and Butambala districts. The researcher purposively selected these facilities because they had more than five midwives in the labour ward, and were also able to provide comprehensive emergency obstetric and neonatal care as per the MOH records [20]. These facilities also had relatively high volumes of patients delivering vaginally every month totaling up to 300, 150, and 200 for Gombe hospital, Nkozi hospital, and Mpigi Health Centre (HC) IV respectively. Each health facility had one maternity unit with the labour ward and postnatal units in the same location.

Two of the health facilities in the study (Gombe hospital and Mpigi Health Centre IV) are government funded facilities where patients are not required to pay for services. However, Nkozi hospital is a private not for profit facility where clients pay a subsidized fee to receive the services. All the facilities act as referral centres for the lower health facilities in the region and thus have functional theatres and offer blood transfusion services.

The Ugandan health care system is organised as a seven-tier system with the first tier at the village level. The care here is provided by lay people providing first-line treatment [21]. The second tier has health centre IIs at the Parish level. At the subcounty level, we have the health centre IIIs followed by the health centre IVs at the health sub district. Then there are the district hospitals and the regional referral hospitals where specialisation in care starts. These refer patients to the National referral hospitals and the national specialised hospitals for super specialised care [21–23]. More details about the Ugandan health system have been documented by Turyamureeba, Yawe and Oryema’s review of the health care system [24]. With regard to maternity care, all women and babies requiring emergency care are referred to higher level facilities starting with health center IV onwards depending on the patient’s needs and level of specialisation required [19].

At the three health facilities selected in this study, the labour room and the postnatal area, where the women are admitted after delivery, are part of the same unit but are located some meters away from each other. At the time of the study, there were 14 midwives working in the labour ward at Gombe hospital, while Mpigi Health Centre IV had 8, and Nkozi had 13 midwives. These midwives were divided into three groups to cover the day, evening and night shifts at each health facility.

Study population

The participants were postpartum women in the immediate postpartum period following a vaginal delivery at Mpigi Health Centre IV, Gombe Hospital, and Nkozi hospital From November 2020 to January 2021.

Inclusion criteria

All postpartum women who had just delivered at the selected facilities (Mpigi Health Centre IV, Gombe and Nkozi hospital) who received care from a midwife, and were willing to participate in the study. They were observed as they received PPC from the delivery of the baby to the time of discharge from the hospital.

Exclusion criteria

All postpartum women who were too sick or were due for referral to another facility were excluded from the study.

Sample size calculation

Using the Kerjcie & Morgan formula for sample size calculation where the population size is known, we aimed to achieve a power of 80% with a confidence interval set at 95% and an error of 0.05 [25]. Based on the number of deliveries per facility, proportionate sampling was done to ascertain the number of observations to be conducted per facility.

| Gombe hospital | Nkozi hospital | Mpigi HCIV | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of deliveries | 300 | 150 | 200 |

| Proportiona | 2.2 | 1.0 | 1.6 |

| No. of women enrolled | 120 | 54 | 89 |

a The proportion here referred to the expected proportion of women delivering at each facility and thus the proportion of participants recruited from the different health facilities in comparison to the overall estimated number of deliveries at the three facilities combined

A total of 263 women were observed in this study with the facility total calculated based on the MoH health facility data [26]

Sampling procedure

The postpartum women at the three health facilities were enrolled consecutively until the required sample was obtained at each health facility.

Study variables

Dependent variable

The dependent variable was postpartum complications developed among mothers during the immediate postpartum period. The data were collected from the participants’ case notes using a data abstraction form. This was a binary categorical variable denoted as 1 if there was a complication present and 0 if there was no complication recorded in the case notes by the attending health worker from the time of delivery to the time of discharge.

Independent variables

The independent variables in this study included socio-demographic characteristics (such as age, marital status, and level of education), Obstetric characteristics (like previous and current obstetric risks during pregnancy), and maternal outcomes (length of hospital stay, status of mother and baby at 24 hours and the postpartum assessments for the mother). Components of immediate postpartum care assessed in this study included timely assessment of vital signs (blood pressure, pulse, and respirations), assessment of the uterine tone and position, assessment of amount of lochia, bladder and bowel emptying, inspection of the perineum/ episiotomy and health education of the mother before discharge. The care received by the women was compared to the ideal postpartum care using a predesigned pretested checklist based on the Ministry of Health guidelines [11]. Care provided to postpartum women was considered “done well’’ if it was provided based on the MOH guidelines and ‘not done’ if it was not provided according to the MOH guidelines.

Data collection tools

Structured observation checklist

A checklist developed using the WHO/MOH guidelines for postpartum care in the immediate and early postpartum period [11, 27] was used to observe the immediate PPC. The checklist was used to document the midwives’ procedures/ actions done when caring for women during the immediate and early postpartum period (assessment of vital signs, uterine tone, vaginal bleeding, episiotomy site, breast condition, baby’s condition, health education and complete physical examination for both mother and baby at discharge).

Data abstraction tool

A data abstraction form was used for the review of casefiles for the patients whose care was observed to capture the socio-demographic data like age, level of education, parity, and obstetric history including, antenatal attendance, antenatal complications, intrapartum complications, and documented care after delivery. This was done to check for the consistency of the observed care with the documented care.

Data collection procedure

Structured observations

Data were collected by MN (a graduate-trained midwife) and five research assistants. The five research assistants were baccalaureate nurses and were trained on the ethical conduct of research and how to use the study tools to collect data. We used an observation checklist to observe the care provided to the women from the time of delivery of the baby to discharge or 24 h, whichever came first. According to the MOH clinical guidelines, new mothers should be observed for a minimum of 24 h before discharge if the woman did not develop life threatening complications [11]. The observations were conducted 24 h a day, throughout November/ December 2020 and January 2021. The data were collected starting with Gombe Hospital followed by Mpigi Health Centre IV and lastly Nkozi Hospital.

The research assistants and MN worked 12-hour rotational shifts to ensure all care provided was documented. The checklist was used to document the midwives’ procedures/ actions done when caring for women during the immediate postpartum period (assessment of vital signs, uterine tone, vaginal bleeding, episiotomy site, breast condition, baby’s condition, and complete physical examination for both mother and baby). This checklist was developed using the WHO/MOH guidelines for immediate postpartum care [11, 27]. Women in the first stage of labour whose case report showed that a vaginal delivery was anticipated were approached by the researcher and the research assistants and given information about the study. Informed consent was then obtained if the mother was eligible for enrolment and then the observer would start data collection as soon as the baby was born. For women who were unable to consent at the time before delivery, the observer would explain the study and ask for verbal consent from the mother before starting their observations. Later when the patient was able to consent to the study, informed consent was obtained from her and her observations were included in the study. All the midwives working in labour ward in the selected health facilities were informed about the study, and all consented to being observed as they provide care to their clients.

Data collection using the data abstraction form

A data abstraction form was employed to gather information regarding the social demographic characteristics of the enrolled women, the existence of postpartum complications, and the outcomes recorded in the patient case files. Data collection was typically initiated in the labor room, and the mother was subsequently followed to the postnatal ward after a short observation period in the labor room.

Data management

All the data collected were kept in a lockable cupboard at the Department of Nursing, Makerere University. Keys to this cupboard are only accessed by the researcher. All information (written data and recorded data) obtained from participants is kept confidential and accessibility is limited to only the researcher and her supervisors on a password-protected computer to ensure privacy. The data will be destroyed after five years from the time of study. No identifying information of the participants was included on the forms and transcripts.

Data analysis

The data were double-entered into Epi data software (version 3.1), cleaned, and then exported to Stata version 16.0 for analysis [28, 29]. Data were analyzed for frequencies and proportions for categorical data. For numerical data, mean and standard deviations were reported for normally distributed data while median and Interquartile range (IQR) were reported for data that was not normally distributed.

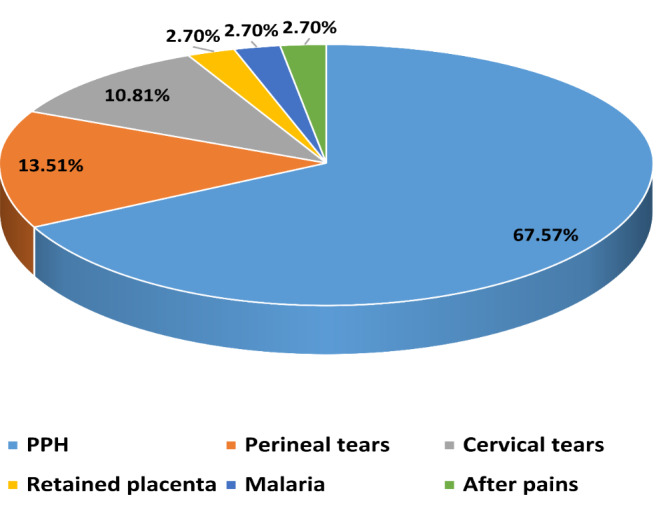

The maternal monitoring and assessments were summarized and presented as proportions stratified by the health facility. We also summarized the overall assessments and the other care provided to the women after 2, 3, and 4 h and presented them as frequencies and percentages. The specific care provided and prevalence of postpartum complications among the women was calculated and presented as a percentage of the total sample population. The types of complications experienced by the women were summarized and presented as a pie chart.

Bivariate analysis was done to compare the different variables with the occurrence of postpartum complications. Collinearity (similarity in variable information) was also tested to determine which variables could be included in the multivariate regression model. We used logistic regression to select the independent variables with a p-value less than 0.2 for inclusion in further multivariate analysis. The independent variables regarding the maternal postpartum assessments at 0 h, 1 h, 2 h and 3 h were included in the multivariate model despite of the level of their p-values since the researcher had hypothesized that, women who were assessed more often would not develop complications. Thereafter, multivariate analysis was done to determine the factors associated with postpartum complications among women in the immediate postpartum period. Interaction and confounding were assessed to develop the final model and variables were considered statistically significant if they had a p-value < 0.05.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of the population

We observed care for 263 women at the three health facilities Gombe (a public hospital, 120), Mpigi (a public HC IV, 89) and Nkozi (a private not-for-profit hospital, 54). The women were aged between 16 and 43 years with a mean age of 25.2 SD ± 6.0, most of them were married 243(92.4%), and nearly all of them had attended antenatal care at least once 262 (99.6%). Over one-third, 94 (37.3%) had experienced pregnancy-related complications in the antepartum period. Nearly all the women, 262 (99.6%), delivered by spontaneous vertex delivery, while 2 (0.4%) had assisted vaginal births. Other characteristics of the mothers and their obstetric characteristics are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2 below.

Table 1.

Mothers’ demographic and antenatal characteristics

| Variable | Frequency (N = 263) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Health facility type | ||

| General Hospital | 120 | 45.6 |

| Health center IV | 89 | 33.8 |

| PNFP Hospital | 54 | 20.5 |

| Age | ||

| Mean | 25.2(6.0) | |

| Range | 16 to 43 | |

| Age (years) | ||

| 16 to 19 a | 45 | 17.1 |

| 20 to 25 | 111 | 42.2 |

| 26 to 30 | 59 | 22.4 |

| 31 to 35 | 25 | 9.5 |

| 36 to 43 | 23 | 8.7 |

| Education level | ||

| No formal education | 6 | 2.3 |

| Primary education | 89 | 33.8 |

| Secondary education | 149 | 56.7 |

| Tertiary | 19 | 7.2 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 243 | 92.4 |

| Single | 20 | 7.6 |

| Number of pregnancies (n = 259)* | ||

| One pregnancy | 82 | 31.2 |

| Two to four pregnancies | 121 | 46.0 |

| Five to eleven pregnancies | 56 | 21.3 |

| ANC attendance | ||

| Yes | 262 | 99.6 |

| No | 1 | 0.4 |

| Number of ANC visits | ||

| 1 to 4 times | 198 | 75.3 |

| 5 to 8 times | 63 | 24 |

| More than 8 times | 1 | 0.4 |

| None | 1 | 0.4 |

| Complications during pregnancy | ||

| No | 169 | 64.3 |

| Yes1 | 94 | 35.7 |

Table 1 above shows the social demographic characteristics of the women enrolled in the study

a The teenage pregnancy rate in Uganda stands at 25% and 34% of girls under 18 are married. There is a national strategy to end teenage pregnancy led by the Government of Uganda and non-government organizations [30]. All the facilities included in this study provided adolescent sexual and reproductive health services

1 Malaria, UTI, Antepartum hemorrhage, HIV, pre-eclampsia/eclampsia

* Number of pregnancies was not documented in the case files of four of the participants

Table 2.

Mothers’ intrapartum and postpartum characteristics

| Variable | Frequency (N = 263) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Mode of delivery | ||

| Spontaneous Vaginal Delivery | 261 | 99.2 |

| Assisted Vaginal delivery | 2 | 0.8 |

| Transfer time to the Postnatal ward | ||

| <=30 min | 137 | 52.1 |

| 31 to 60 min | 63 | 23.9 |

| 1 to 2 h | 31 | 11.8 |

| >2 h | 32 | 12.2 |

| Escorted by Health worker to postnatal ward | ||

| Yes | 173 | 65.8 |

| No | 90 | 34.2 |

| Mother outcome | ||

| Discharged alive | 262 | 99.6 |

| Referred | 1 | 0.4 |

| Status of mother at 24 h | ||

| Discharged | 231 | 87.8 |

| Still admitted | 32 | 12.2 |

| Length of facility stay (n = 263)* | ||

| Less than 24 h | 209 | 79.5 |

| >1 < 2 days | 50 | 19.0 |

| ≥ 2 days | 4 | 1.5 |

*54 women stayed at the facility for more than 24 h after delivery. Of these, only four women stayed beyond 48 h. However, from the records only 32 women were still admitted on the wards beyond 24 h though another 22 were still on the units despite having been discharged because they were either waiting for transport or trying to clear health facility bills during this time

At birth, the majority of the newborns had APGAR scores between 7 and 10 at one minute, 228 (86.7%) and 246(93.5%) at five minutes, while 5 (1.9%) were stillborn. The mean birth weight was 3.1 kg SD ± 0.44, and 251(95.4%) of the babies were examined fully before discharge. The details of the newborn characteristics are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Baby’s characteristics

| Baby’s characteristics (N = 263) |

Overall | General Hospital | Health Center IV | Private Hospital |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apgar score at 1 min | ||||

| 7 to 10 | 251 | 115 | 83 | 53 |

| 6 to 1 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| 0 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 0 |

| Not recorded but baby alive | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Apgar score at 5 min | ||||

| 7 to 10 | 252 | 116 | 83 | 53 |

| 6 to 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 0 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Not recorded but baby alive | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Baby’s status at birth | ||||

| Alive | 258 | 118 | 86 | 54 |

| Dead | 5 | 2 | 3 | 0 |

| Baby weight | ||||

| 2.0 to ≤ 2.4 kg | 18 | 7 | 6 | 5 |

| 2.6 to 3.5 kg | 201 | 91 | 67 | 43 |

| ≥ 3.6 kg | 41 | 20 | 15 | 6 |

| Not recorded | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Newborn assessment done | ||||

| Yes | 251 | 112 | 89 | 50 |

| No | 12 | 8 | 0 | 4 |

| Baby’s outcome | ||||

| Discharged alive | 248 | 115 | 85 | 48 |

| Died | 6 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Admitted to NICU | 8 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Referred | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

Note: All health facilities in the study were providing Comprehensive emergency obstetric and newborn care to all women and babies in need of emergency care. All babies who had APGAR scores that were < 7 were resuscitated by the attending midwives

Maternal assessments in the postpartum period

The overall rate of assessments done according to the guidelines [10, 11] was very low, 9/263(3.4%) within the first 2 h after delivery; by the third hour, the rate had risen to 29/263(11%), then it dropped slightly 10/263(3.8%) at the fourth hour. It fell back to the initial rate of 3/263(1.1%) when assessments were considered between the 6th hour and discharge (Table 4).

Table 4.

Maternal postpartum assessments

| Time | Overall | General Hospital | Health Centre IV | Private Hospital |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother checked every 15 min during the first 2 h (N = 263) | ||||

| Yes | 9 (3.4) | 6 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (5.6) |

| No | 254 (96.6) | 114 (95.0) | 89 (100.0) | 51 (94.4) |

| Mother checked at 3 h (N = 263) | ||||

| Yes | 30 (11.4) | 3 (2.5) | 4 (4.5) | 23 (42.6) |

| No | 233 (88.6) | 117 (97.5) | 85 (95.5) | 31 (57.4) |

| Mother checked at 4 h (N = 263) | ||||

| Yes | 11 (4.2) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (1.1) | 9 (16.7) |

| No | 252 (95.8) | 119 (99.2) | 88 (98.9) | 45 (83.3) |

| Mother checked every four hours till discharge (N = 263) | ||||

| Yes | 38 (14.4) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (2.3) | 35 (64.8) |

| No | 225 (85.6) | 119 (99.2) | 86 (97.7) | 19 (35.2) |

| Documentation done * | ||||

| Yes | 116(44.1) | 42(35.0) | 33(37.1) | 41(75.9) |

| No | 147(55.9) | 78(65.0) | 56(62.9) | 13(24.1) |

| Breastfeeding encouraged | ||||

| Yes | 121(46.0) | 96(80.0) | 11(12.4) | 14(25.9) |

| No | 142(54.0) | 24(20.0) | 78(87.6) | 40(74.1) |

| Snack availed for mother | ||||

| Yes | 128(48.7) | 14(11.7) | 72(80.9) | 42(77.8) |

| No | 135(51.3) | 106(88.3) | 17(19.1) | 12(22.2) |

* Documentation in this study referred to documentation of the assessments and other care provided to the women postdelivery

At three hours, the overall care was still very low, with only 10/263 (3.8%) of the participants having a blood pressure check, 9/263 (3.4%) had their pulse checked, 29/263(11%) not checked for vaginal bleeding, 22/263(8.4%) were not encouraged to empty their bladders and 6/263(2,0.3%) were not assessed for uterine tone and position (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Specific assessments done for the postpartum women at different times post-delivery

| Variable | 0 to 2 h | 3 h | 4 h |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood pressure taken | |||

| Yes | 52 (19.8) | 10(3.8) | 4(1.5) |

| No | 211(80.2) | 253(96.2) | 259(98.5) |

| Pulse checked | |||

| Yes | 0(0) | 9(3.4) | 4(1.5) |

| No | 0(0) | 254(96.6) | 259(98.5) |

| PV bleeding assessed | |||

| Yes | 218(82.9) | 234(89.0) | 252(95.8) |

| No | 45(17.1) | 29(11.0) | 11(4.2) |

| Uterine tone checked | |||

| Yes | 151(57.4) | 257(97.7) | 261(99.2) |

| No | 112(42.6) | 6(2.3) | 2(0.8) |

| Uterus position assessed | |||

| Yes | 159(60.5) | 157(97.7) | 161(99.2) |

| No | 104(39.5) | 6(2.3) | 2(0.8) |

| Bladder emptying encouraged | |||

| Yes | 133(50.6) | 241(91.6) | 254(96.6) |

| No | 130(49.4) | 22(8.4) | 9(3.4) |

| Breathing assessed | |||

| Yes | 221(84.0) | ||

| No | 42(16) | ||

| Presence of Headache assessed | |||

| Yes | 220(83.6) | ||

| No | 43(16.3) | ||

| Vaginal check done | |||

| Yes | 9(3.4) | ||

| No | 254(96.6) |

After 4 h, 4/263(1.5%) of the women had their blood pressure and pulse assessed, 11/263 (4.2%) were not assessed for vaginal bleeding, 9/263(3.4%) were not encouraged to empty their bladders, and 2/263(0.8%) were not assessed for uterine tone and position (see Table 5 above)

The overall provision of care as per the guidelines was low, with over 80% of the women 211(80.1%) having no blood pressure assessment in the first 2 h following birth; however, the examination for vaginal bleeding, perineal tears, uterine tone, and position were done at least once within the first two hours after delivery for over 80% of the participants. Notably, at Gombe General Hospital (severe headache 91/120(75.8%)) and difficulty in breathing 106/120(88.3%) were more regularly assessed compared with the other two facilities. Mpigi health center IV had the highest scores for initiation of breastfeeding 78(87.6%) and for patients being given a snack within the first 2 h after birth 72(80.9%) (see Table 5).

Regarding the general care provided, only one mother (0.4%) was examined thoroughly at discharge. 20% (53/263) of the women got pain relief while still admitted, and nearly half of them 126(479%) received pain medication at the time of discharge. Over half of the mothers (146/263(55.5%)) were kept warm and comfortable (observed to be at rest in bed) during their hospitalization. The average length of hospital stay after delivery was 14 h and 51 min, with a maximum length of 3 days, 7 h and 14 min and a minimum length of hospital stay of 2 h and 27 min.

Prevalence of postpartum complications among women delivered at health facilities within the greater Mpigi region

The prevalence of postpartum complications was calculated using the formula below:

|

|

|

The prevalence of postpartum complications was 14.1% (37/263) (95% CI: 10.3–18.9%). Among these 37 women who presented with a complication, the majority had postpartum hemorrhage, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Blood loss among the women who delivered within the greater Mpigi region ranged from 60 to 900 milliliters with a median blood loss amount of 120 milliliters (IQR: 100, 300). The Blood loss was reported based on the visual estimation by the midwife. PPH was reported as a woman having blood loss of 500mls or greater as per the guidelines.

Fig. 1.

Types of postpartum complications among women in the greater Mpigi region (N = 37)

Factors associated with having a postpartum complication

A multivariable Poisson regression analysis was done to determine the factors associated with developing a postpartum complication. The multivariable Poisson regression analysis included all variables with p-values less than 0.2 at bivariate analysis. The maternal social demographic characteristics, presence of pregnancy complications, time of transfer to the postnatal ward, whether documentation was complete, status of the mother at 24 h after delivery, and length of hospital stay were selected for further analysis (Table 6 and Table 7). The assessment pattern at 0 to 2 h, 3 h, and every four hours until discharge was also considered for further analysis because we wanted to ascertain if the assessment at different time points affected the prevalence of complications among the postpartum women. None of the baby’s characteristics were selected for further analysis (Table 7).

Table 6.

Bivariate association of mother characteristics with postpartum complications

| Variable | Postpartum complication |

cOR | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO n(%) | YES n(%) | ||||

| Age (years) | |||||

| 16 to 24 | 123(86) | 20(14) | 1 | ||

| 25 to 34 | 78(84.8) | 14(15.2) | 1.1 | 0.53–2.32 | 0.794 |

| 35 to 43 | 25(89.3) | 3(10.7) | 0.74 | 0.20–2.68 | 0.644 |

| Woman’s education Level | |||||

| Primary /no formal education | 85(89.5) | 10(10.5) | 1 | ||

| Secondary/ Tertiary education | 141(83.9) | 27(16.1) | 1.63 | 0.75–3.53 | 0.218 |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 209(86) | 34(14) | 1 | ||

| Single | 17(85) | 3(15) | 1.08 | 0.30–3.91 | 0.901 |

| Mother had pregnancy complications | |||||

| Yes | 76(80.9) | 18(19.1) | 1.87 | 0.93–3.78 | 0.081 |

| No | 150(88.8) | 19(11.2) | 1 | ||

| Mother escorted by Health worker to postpartum ward | |||||

| Yes | 151(87.3) | 22(12.7) | 1 | ||

| No | 74(83.1) | 15(16.9) | 1.39 | 0.68–2.84 | 0.365 |

| Time to transfer to postnatal ward after delivery | |||||

| <=30 min | 130(94.9) | 7(5.1) | 1 | ||

| 31 to 60 min | 59(93.7) | 4(6.3) | 1.26 | 0.35–4.48 | 0.722 |

| 1 to 2 h | 21(67.7) | 10(32.3) | 8.84 | 3.03–25.84 | < 0.001 |

| >2 h | 16(50) | 16(50) | 18.57 | 6.62–52.06 | < 0.001 |

| Mother checked every 15 min for first 2 h | |||||

| Yes | 7(77.8) | 2(22.2) | 1.79 | 0.36–8.98 | 0.481 |

| No | 219(86.2) | 35(13.8) | 1 | ||

| Mother Checked at 3 h after delivery | |||||

| Yes | 13(44.8) | 16(55.2) | 12.48 | 5.28–29.50 | < 0.001 |

| No | 213(91.0) | 21(9.0) | 1 | ||

| Mother Checked at 4 h after delivery | |||||

| Yes | 5(45.5) | 6(54.6) | 8.55 | 2.46–29.78 | 0.001 |

| No | 221(87.7) | 31(12.3) | 1 | ||

| Outcome of mother at 24 h | |||||

| Discharged | 212(91.8) | 19(8.2) | 1 | ||

| Still admitted | 14(43.8) | 18(56.3) | 14.35 | 6.17–33.33 | < 0.001 |

Table 6 showing the association between the maternal sociodemographic characteristics and having postpartum complications at Bivariate analysis

Table 7.

Bivariate analysis of babies’ characteristics and mothers’ outcome characteristics with postpartum complications

| Variable | Postpartum complication | cOR | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO n (%) | YES n (%) | ||||

| Apgar score at 1 min | |||||

| Above 7 | 195(85.5) | 33(14.5) | 1 | ||

| 7 and below | 28(87.5) | 4(12.5) | 0.84 | 0.28–2.57 | 0.765 |

| Apgar score at 5 min | |||||

| Above 7 | 212(86.2) | 34(13.8) | 1 | ||

| 7 and below | 11(78.6) | 3(21.4) | 1.7 | 0.45–6.43 | 0.434 |

| Status of baby at birth | |||||

| Alive | 222(86) | 36(14) | 1 | ||

| Dead | 4(80) | 1(20) | 1.54 | 0.17–14.25 | 0.703 |

| Birth weight | |||||

| Normal birth weight | 171(85.1) | 30(14.9) | 1 | ||

| Low/high birth weight | 53(89.8) | 6(10.2) | 0.65 | 0.25–1.64 | 0.356 |

| New born assessment | |||||

| Yes | 215(85.7) | 36(14.3) | 1 | ||

| No | 11(91.7) | 1(8.3) | 0.54 | 0.07–4.35 | 0.565 |

| Outcome of baby at discharge | |||||

| Discharged alive | 215(86.3) | 34(13.7) | 1 | ||

|

Adverse outcome (Admitted to NICU/Referred/Died) |

11(78.6) | 3(21.4) | 1.57 | 0.42–5.88 | 0.5 |

| Documentation done | |||||

| Yes | 89(76.7) | 27(23.3) | 4.16 | 1.92–9.02 | < 0.001 |

| No | 137(93.2) | 10(6.8) | 1 | ||

| Length of hospital stay | |||||

| Less than 24 h | 192(90.9) | 17(9.1) | 1 | ||

| 1 day | 32(64.0) | 18(36) | 2.12 | 0.92–4.91 | 0.079 |

| >2 days | 2(50.0) | 2(50.0) | 5.02 | 1.92–13.12 | 0.001 |

Table 7 shows the association between the babies’ characteristics and the mothers’ outcomes with postpartum complications at Bivariate analysis.

The presence of interaction and confounding variables was investigated and determined to be absent. The factors that were found to be significantly associated with postpartum complications include assessment done 3 h after delivery, the outcome of the mother at 24 h, documentation being complete, and the time to transfer to the postnatal ward (Table 8).

Table 8.

Multivariate analysis of the pattern of postpartum assessments and postpartum complications among women delivering in health facilities within greater Mpigi region

| Variable | cOR (95% CI) | p-value | aOR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome of mother at 24 h | ||||

| Discharged | 1 | 1 | ||

| Still admitted | 14.35(6.17–33.33) | < 0.001 | 5.02(1.090–23.11) | < 0.038 |

| Documentation done | ||||

| Yes | 4.16(1.92–9.02) | < 0.001 | 2.56 (0.980–6.71) | 0.055 |

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Length of hospital stay | ||||

| < 1 day | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1 day | 2.12 (0.92–4.91) | 0.079 | 3.96(1.47–10.64) | 0.006 |

| > 2 days | 5.02(1.92–13.12) | 0.001 | 3.88(0.29-52.0) | 0.031 |

| Mother checked at 3 h after delivery | ||||

| Yes | 12.48(5.28–29.50) | < 0.000 | 0.353 (0.214-0 0.580) | 0.000 |

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Time to transfer from labour ward to postnatal ward | ||||

| ≤30 min | 1 | 1 | ||

| 31 to 60 min | 1.26(0.35–4.48) | 0.722 | 0.99 (0.24–3.94) | 0.985 |

| 1 to 2 h | 8.84(3.03–25.84) | < 0.001 | 3.82(1.11–13.11) | 0.033 |

| >2 h | 18.57(6.62–52.06) | < 0.001 | 8.41(2.53–27.98) | 0.001 |

Women who were assessed three hours after delivery were less likely to have had a postpartum complication compared to those who had not been assessed (aOR = 0.353; 95% CI: 0.214–0.580; p = 0.000). Mothers whose stay within the hospital had been well documented were almost three times more likely to have had a postpartum complication than those whose documentation of care had not been completed well but this was not found to be statistically significant (aOR = 2.56; 95% CI: 0.980–6.707; p = 0.055).

Mothers who had been transferred to the postpartum ward after two hours from the time of delivery were eight times more likely to have had a postpartum complication compared to those who had been transferred within 30 min after delivery (aOR = 8.41; 95% CI: 2.53–27.98; p = 0.001). Similarly, mothers who had been transferred between 1 and 2 h were nearly four times (aOR = 3.82; 95% CI; 1.11–13.11; p = 0.003) more likely to have had complications compared to those who had been transferred within 30 min. Also, women who were still admitted 24 h after delivery were nearly four times more likely to have a postpartum complication compared to those who were discharged in less than 24 h after delivery (aOR = 3.96; 95% CI: 1.47–10.64; p = < 0.006).

Discussion

The study was conducted at three health facilities in Mpigi and Butambala districts, revealing that general postnatal assessments and postnatal care were suboptimal. Postpartum women did not receive timely or adequate assessments, potentially leading to a missed opportunity for the prompt identification or management of complications. Consequently, this shortfall could disappoint both mothers and caretakers, as their investment in facility delivery might not guarantee the desired experience and care. A commission on the quality of care in low and middle-income countries, Uganda included, reported that health workers, on average, followed only 47% of the recommended guidelines [31]. A study done in the Bunyoro region in Uganda, also found that less than 20% of the postpartum women had abdominal examinations or checks on vaginal bleeding before discharge as per the guidelines [14].

Another study done in sub-Saharan Africa found that only 66% of women delivering at a health facility received at least one check after delivery before discharge [12]. These scores were higher than the overall frequency of monitoring women and their babies based on the guidelines in our study. The variation in scores may be attributed to individual health worker factors and environmental factors that could impede midwives from providing care optimally [12, 13, 32]. Overall, these findings underscore the need for improved training, increased resources, and better working conditions to ensure that women and their babies receive the recommended postpartum care.

In relation to the occurrence of postpartum complications, it was observed that women who remained admitted after 24 h and those with comprehensive medical records were more likely to have developed complications compared to their counterparts. This discovery suggests that women experiencing complications are more likely to be retained at health facilities for 24 h or longer, resulting in more thorough documentation of their care compared to those who do not encounter complications during this timeframe. This could also be attributed to a fear of complications. In our previous qualitative studies, midwives reported documenting care for those needing referral, and as evidence of the care provided in cases of litigation [18]. This could imply that individuals deemed ‘without complications’ might not receive optimal care per the MOH guidelines. They may be discharged with minimal assessments, leaving maternal and newborn complications undiagnosed [18, 33]. This could result in readmissions or deaths in the community, as reported in our study on the healthcare needs of teenage first-time mothers [33]. Our study highlighted the importance of ensuring that all individuals, regardless of their perceived ‘lack of complications’, receive the same level of care in accordance with the MOH guidelines. Failure to do so could lead to serious consequences, such as undiagnosed maternal and newborn complications. This not only puts the health of the mother and child at risk but also increases the likelihood of readmissions or even deaths within the community [33]. It is crucial to address these issues and improve the healthcare system to prevent such outcomes.

The women who were transferred to the postnatal ward after one hour were also more likely to have developed complications during the postpartum period. This finding indicates that the midwives in the study were keen to identify women needing extra attention before transfer to the postnatal ward, which resulted in the women being transferred to the ward later than their counterparts. We found that midwives paid close attention to the women with complications and kept them near where they worked for closer monitoring. The organization of the wards may drive this finding at the facilities in this study, where the place for admission for postpartum women is far from the labor wards. This finding points to a possible contextual coping method for midwives working in constrained circumstances who seek to provide care based on the individual woman’s needs within their available resources where no high dependence unit and limited human resources exist [18]. This also shows an attempt to prioritize and continue providing care based on the recommended guidelines for the critical clients while working in a resource limited setting. However, the same may lead to the delayed diagnosis of those women who develop complications later, in the immediate postpartum period, and are not monitored as required, especially if their caregivers are not keen [33]. This, coupled with the fact that the same midwives in the labor ward were responsible for the care of the women in the postnatal ward as well, could have resulted in their making decisions to retain some women with suspected or possible complications in the labor ward for further monitoring. This practice may have been implemented to ensure that any potential complications during the postpartum period were immediately addressed and treated. Additionally, the proximity of the labor ward to the postnatal ward facilitated quicker response times in emergencies. However, further research is needed to determine the effectiveness and impact of this organizational setup on patient outcomes and overall quality of care.

A study on documentation of care by health workers in Angola showed a lot of missing information in the hospital records of women delivering at the health facility, including records of care after birth [34]. The level of document completion in our study was 44.1%, which was higher than the level of documentation in the Indian study, where postpartum blood pressure and advice at discharge were documented for only 13.8% and 1.9% of the postpartum women [35]. The low documentation of postpartum care may be related to the care being provided, which was suboptimal; hence, midwives found that they had little or nothing to document. Furthermore, the lack of documentation may also be attributed to the lack of prioritization and training on postpartum care. Midwives may have been more focused on immediate concerns during childbirth, neglecting to document and provide comprehensive postpartum care. Additionally, the absence of standardized protocols and guidelines for postpartum care could have contributed to the low documentation rates. Addressing these issues and emphasizing the importance of postpartum care in training programmes may improve documentation rates and ensure a better quality of care for women after childbirth.

Notably, in our analysis, only one client was examined before discharge. Although we were not able to observe the care at discharge for 32/263 (12.2%) of the participants who were discharged after 24 h, the proportion of those not examined among those observed was notable 230/231(99.5%). According to the WHO and MOH guidelines, pre-discharge assessment and examination should be done for all women and their newborns as a precaution against discharging women with unidentified complications [1, 10]. Our finding shows that the midwives either do not know about this or cannot do so due to other competing roles that they assume while on duty. Using the WHO pre-discharge checklist to assess women and babies could improve the midwives’ practice at this time [36]. This checklist provides a structured and standardized assessment approach, ensuring no critical steps are missed. By using this checklist, midwives can confidently identify any complications or issues that need further attention before discharge. Additionally, training and education on the importance of pre-discharge assessment should be provided to midwives to ensure they know the guidelines and can effectively implement them in their practice.

Postpartum hemorrhage was the main postpartum complication identified in our study. However, factors identified as associated with PPH in other studies were not found to be significant in our study. For example, a study conducted on the factors associated with Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) in Uganda found that women with multifetal pregnancies, large newborns and a positive HIV serostatus were more likely to develop PPH [37]. No women observed in our study had delivered twins, and the baby’s weight was not significantly associated with developing postpartum complications. However, it should be noted that the absence of twin pregnancies and the lack of significant association between the baby’s weight and postpartum complications does not dismiss the impact of these factors on PPH. Further research should be conducted to examine the relationship between HIV and postpartum complications, as it may provide valuable insights for preventing and managing PPH in Uganda.

Strengths and limitations

We observed three healthcare facilities’ caregiving procedures in the early postpartum phase. This illustrates the kind of care provided to postpartum women in the facilities, as opposed to what is necessary during this time. This enabled us to assess the content of the postpartum care and the presence of postpartum complications. This study offers data from real-time observations that will help explain care gaps identified by postpartum care studies using DHS data or exit interviews [3, 14].

However, we used data abstracted from the patient files that could have been better documented. This could have affected our findings. Additionally, this was a cross-sectional study done in one region of the country. Hence, the results are more generalizable to the target population. Furthermore, the limited documentation in the patient files may have resulted in missing important variables or inaccurate information, which could have influenced our analysis and conclusions. Our observation of care ended at 24 h for each participant and it is possible that some of the care provided by the midwives beyond this time point was not observed. This could have led to inaccurate results being reported about the postpartum care provided in these health facilities. The presence of MN and the research assistants in the health facilities could also have altered the way that health workers practiced during the study period. This was mitigated for by allowing the teams to work on the units for two to seven days before the recruitment of participants started to reduce the Hawthorne effect. Lastly, there were several variables known to be associated with postpartum complications that were not assessed for in this study [37, 38]. These could have altered the findings if they had been included in the model. Therefore, caution should be exercised when applying our results to the broader population, and further research in different regions is warranted to validate our findings.

Conclusion

The length of hospital stay for most of the postpartum women without complications is less than 24 h, and the maternal assessments before discharge are suboptimal. There is a need to institutionalize the provision of immediate postpartum care so that it is uniformly provided to all women and not dependent on the woman’s condition or the midwives’ perceptions. The lack of quality care along the childbirth continuum, especially in the postpartum period, has been cited to be a hindrance to facility births and needs to be addressed.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the research assistants who assisted us in data collection, the midwives and the postpartum women from all the facilities who consented to be observed.

Author contributions

MN, DKK, SK, and GKN were involved in the study’s conceptualization. MN collected the data. MN, GKN and DKK analyzed the data, MN, GKN, PAM and DKK were involved in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the DAAD in-country scholarships for PhD students (2017) together with further funds from the NURTURE fellowship, a Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes Grant Number D43TW010132 (PI: Nelson K Sewankambo for mentoring faculty in research).

Data availability

The data base used in this study is still being used by MN for some analysis. MN is a PhD student and still has some work to do with the data but the data base is available on request from her.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Makerere University School of Health Sciences Higher Degrees’ Research and Ethics Committee (MAKSHSREC REF:2016-044) and the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology (HS773ES). All district health officers provided administrative clearance to conduct the study in their districts. Written informed consent was sought from all the participants before their enrolment in the study. Participants were free to withdraw from the study at any time without being coerced or explaining their reasons for withdrawal from the study. All postpartum women in this study who were below 18 years were regarded as emancipated minors and thus were asked to consent to participate in this study before enrolment in the study.

Consent for publication

“Not applicable”.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on maternal and newborn care for a positive postnatal experience: web annexes. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MoH: Essential Maternal and Newborn Clinical Care Guidelines for Uganda. In. Edited by department Rach. Kampala. 2022: 60.

- 3.Dey T, Ononge S, Weeks A, Benova L. Immediate postnatal care following childbirth in Ugandan health facilities: an analysis of demographic and health surveys between 2001 and 2016. BMJ Global Health. 2021;6(4):e004230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO. levels and trends in child mortality report. In: newborn mortality. Geneva; 2021.

- 5.WHO. Maternal mortality. In. Geneva; 2023.

- 6.WHO. Maternal mortality: the urgency of a systemic and multisectoral approach in mitigating maternal deaths in Africa. Geneva, WHO; 2023. Available from https://files.aho.afro.who.int/afahobckpcontainer/production/files/iAHO_Maternal_Mortality_Regional_Factsheet.pdf

- 7.Akhter S. Maternal morbidity: the lifelong experience of survivors. Lancet Global Health. 2024;12(2):e188–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alkema L, Chou D, Hogan D, Zhang S, Moller A-B, Gemmill A, Fat DM, Boerma T, Temmerman M, Mathers C, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and trends in maternal mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis by the UN Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-agency Group. Lancet. 2016;387(10017):462–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.UNFPA. Transformative result: cost of ending preventable maternal deaths. Chapter 1. Newyork, USA, UNFPA; 2020. Available from https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource-pdf/Costing_of_Transformative_Results_Chapter_1_-_Cost_of_Ending_Preventable_Maternal_Deaths1.pdf

- 10.Ministry of health: Essential Maternal and Newborn Clinical Care Guidelines for Uganda. In. Edited by department Rach. Kampala. 2022: 60.

- 11.Ministry of health. Uganda clinical guidelines; National guidelines for the management of common conditions. In. Kampala: Ministry of health; 2016.

- 12.Benova L, Owolabi O, Radovich E, Wong KLM, Macleod D, Langlois EV, Campbell OMR. Provision of postpartum care to women giving birth in health facilities in sub-saharan Africa: a cross-sectional study using demographic and Health Survey data from 33 countries. PLoS Med. 2019;16(10):e1002943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Munabi-Babigumira S, Glenton C, Willcox M, Nabudere H. Ugandan health workers’ and mothers’ views and experiences of the quality of maternity care and the use of informal solutions: a qualitative study. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(3):e0213511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muwema M, Kaye DK, Edwards G, Nalwadda G, Nangendo J, Okiring J, Mwanja W, Ekong EN, Kalyango JN, Nankabirwa JI. Perinatal care in Western Uganda: prevalence and factors associated with appropriate care among women attending three district hospitals. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(5):e0267015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Graft-Johnson J, Vesel L, Rosen HE, Rawlins B, Abwao S, Mazia G, Bozsa R, Mwebesa W, Khadka N, Kamunya R. Cross-sectional observational assessment of quality of newborn care immediately after birth in health facilities across six sub-saharan African countries. BMJ open. 2017;7(3):e014680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pindani M, Phiri C, Chikazinga W, Chilinda I, Botha J, Chorwe-Sungani G. Assessing the quality of postnatal care offered to mothers and babies by midwives in Lilongwe District. S Afr Fam Pract (2004). 2020;62(1):e1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanyunyuzi AE, Ekong EN, Namukwaya RE, Namala AL, Mudondo L, Mwebaza E, Smyth R. A criteria-based audit to improve early postnatal care in Jinja, Uganda. Afr J Midwifery Women’s Health. 2017;11(2):78–83. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Namutebi M, Nalwadda GK, Kasasa S, Muwanguzi PA, Kaye DK. Midwives’ perceptions towards the ministry of health guidelines for the provision of immediate postpartum care in rural health facilities in Uganda. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2023;23(1):1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Namutebi M, Nalwadda GK, Kasasa S, Muwanguzi PA, Ndikuno CK, Kaye DK. Readiness of rural health facilities to provide immediate postpartum care in Uganda. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23(1):22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MoH: National district staff records. In. 2019 edn. Kampala: Ministry of health; 2019.

- 21.Medard T, Yawe BL, Bosco OJ. Health Care Delivery System in Uganda: a review. Tanzan J Health Res 2023, 24(2).

- 22.MoH. Health facilities inventory. In. Edited by division hi. Kampala: Ministry of health; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hospitals. https://www.health.go.ug/hospitals/

- 24.Turyamureba M, Yawe B, Oryema JB. Health Care Delivery System in Uganda: a review. Tanzan J Health Res. 2023;24(2):57–64. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krejcie RV, Morgan DW. Determining sample size for research activities. Educ Psychol Meas. 1970;30(3):607–10. [Google Scholar]

- 26.MoH. Annual health sector perfomance report. In. Kampala: Ministry of health; 2018.

- 27.WHO. WHO recommendations on postnatal care of the mother and newborn. In. Geneva; 2013. [PubMed]

- 28.(Ed.) CTaLJ: EpiData - Comprehensive Data Management and Basic Statistical Analysis System. In., 3.10 edn. Odense Denmark: EpiData Association; 2020.

- 29.StataCorp L. Stata statistical software (version release 16). In: College Station, TX:. vol. 464. USA; 2019: 465.

- 30.Uganda Go: THE NATIONAL STRATEGY TO END CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY. In: Kampala, editor. 2022/2023–2026/2027. Uganda: Ministry of Gender, labour and social development; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kruk ME, Gage AD, Arsenault C, Jordan K, Leslie HH, Roder-DeWan S, Adeyi O, Barker P, Daelmans B, Doubova SV. High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development goals era: time for a revolution. Lancet Global Health. 2018;6(11):e1196–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Munabi-Babigumira S, Lewin S, Glenton C, Velez M, Gonçalves-Bradley DC, Bohren MA. Factors that influence the provision of postnatal care by health workers: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2021;2021(7):CD014790. 10.1002/14651858.CD014790

- 33.Namutebi M, Kabahinda D, Mbalinda SN, Nabunya R, Nanfuka DG, Kabiri L, Ngabirano TD, Muwanguzi PA. Teenage first-time mothers’ perceptions about their health care needs in the immediate and early postpartum period in Uganda. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanjuluca TH, Almeida A, Correia R, Costas T. Quality of records in clinical forms of childbirth in the Maternity Hospital of Lubango, Angola. Gac Sanit. 2023;37:102246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chaturvedi S, Randive B, Raven J, Diwan V, De Costa A. Assessment of the quality of clinical documentation in India’s JSY cash transfer program for facility births in Madhya Pradesh. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2016;132(2):179–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.PNC Pre-Discharge Checklist Poster. Africa https://www.healthynewbornnetwork.org/resource/pnc-pre-discharge-checklist-poster-africa/

- 37.Ononge S, Mirembe F, Wandabwa J, Campbell OM. Incidence and risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage in Uganda. Reproductive Health. 2016;13(1):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Negesa Beyene B, Jara Boneya D, Gelchu Adola S, Abebe Sori S, Dinku Jiru H, Sirage N, Awol A, Melesse GT, Wayessa ZJ, Jemalo A, et al. Factors associated with postpartum hemorrhage in selected Southern Oromia hospitals, Ethiopia, 2021: an unmatched case-control study. Front Glob Womens Health. 2024;5:1332719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data base used in this study is still being used by MN for some analysis. MN is a PhD student and still has some work to do with the data but the data base is available on request from her.