Abstract

Background

Globally, maternal mortality remains a critical issue, with male involvement during antenatal care (ANC) recognized as pivotal in reducing maternal deaths. Limited evidence on male involvement exists in low and middle-income countries, including Ethiopia. This study aimed to assess male involvement during antenatal care and associated factors among married men whose wives gave birth within the last 6 months in Debretabor town, North West Ethiopia in 2023.

Objective

Evaluate the level of male involvement during antenatal care and identify associated factors in the specified study area.

Methods

A community-based cross-sectional study involved 404 married men, whose wives had given birth within the past 6 months in Debretabor town. Data were collected using face-to-face interviews, entered into EpiData version 4.6, and analyzed using SPSS version 25. Logistic regression analyses determined associations.

Results

Male involvement during antenatal care in the study area was 46.8% (CI: 41.6, 51.5). Factors influencing involvement included men's attitude (AOR = 2.365), lack of male invitation to the examination room (AOR = 0.370), couples' living status (AOR = 4.461), men with secondary education (AOR = 4.052), men with diploma and above (AOR = 4.276), and complications during pregnancy (AOR = 6.976).

Conclusion and recommendation

The observed low level of male involvement underscores the need for targeted interventions. Stakeholders should promote male participation through counseling, community mobilization, and awareness campaigns.

Keywords: Antenatal care, Male involvement, Attitude, Knowledge, Debretabor town

Introduction

Antenatal care (ANC) is a crucial component of maternal and child health, encompassing a spectrum of services provided to pregnant mothers from conception confirmation to the onset of labor [1]. The significance of ANC lies in ensuring optimal health conditions for both the mother and the baby throughout pregnancy, childbirth, and the postnatal period [1]. Recognizing the importance of male involvement (MI) during ANC, international initiatives like the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) and the World Health Organization (WHO) have emphasized the need for male participation in promoting maternal health [2, 3]. However, a global consensus on the definition and assessment criteria for MI during ANC is yet to be established.

Diverse interpretations of MI during ANC exist, with some focusing solely on the husband's presence at ANC clinics [4]. In this study, we define MI as the active participation of husbands in both household and facility-level ANC activities. This includes jointly seeking ANC at the facility, collaborative decision-making, and providing financial and physical support during pregnancy [5]. Recognizing the potential of MI to reduce preventable maternal and child health issues, it was positioned as a pivotal strategy to address delays in seeking care during pregnancy and childbirth [6].

Male involvement in ANC refers to seeking ANC together at the facility, obtaining information from the health provider, making joint decisions about actions and destinations, and providing financial and physical support during pregnancy [8].

In many parts of the world, societal norms often designate men, older women, and families as key decision-makers regarding women's health, child health, and primary providers of emotional and financial support [7, 8]. African countries, in particular, have observed increased maternal health service utilization with greater male participation in ANC, leading to positive outcomes such as improved knowledge of danger signs, enhanced utilization of skilled birth attendants, and reduced stress and anxiety during labor [9, 10].

In the Ethiopian context, where a predominantly male-dominated society perceives pregnancy and childbirth as solely female responsibilities, male involvement in ANC has been shown to mitigate delays in seeking care during pregnancy and childbirth [11]. Despite the high maternal mortality rates in the country, male involvement during ANC has not received adequate attention, making it imperative to assess its levels and associated factors in the study area [12].

The statement of the problem highlights the persistent challenges in maternal health, emphasizing the high rates of maternal mortality and morbidity worldwide, particularly in low and middle-income countries [13]. Despite global efforts to reduce maternal deaths, underutilization of maternal health services remains a significant obstacle [14]. Male involvement during ANC emerges as a key driver for improving maternal and child health outcomes, yet it faces challenges due to deeply ingrained perceptions that matters related to pregnancy and childbirth are exclusively women's responsibilities [15].

The urgency of addressing this problem is underscored by alarming statistics, with 94% of maternal deaths occurring in low and middle-income countries, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa [16]. In Ethiopia, where approximately four women die during pregnancy, childbirth, or within two months after childbirth, male involvement during ANC has the potential to contribute significantly to reducing maternal mortality [17]. However, current evidence suggests a lack of active male participation in ANC services, further emphasizing the need for a comprehensive assessment in the study area.

Existing literature, such as that by Mengistu et al. [18], has explored the level and factors associated with male involvement in ANC, highlighting the significant gaps and variations in male participation. Their study found that socio-cultural factors, lack of awareness, and health system barriers significantly hinder male involvement. Similar findings were reported by Yargawa and Leonardi-Bee [19], who conducted a systematic review of male involvement in maternal health across different countries, emphasizing the need for targeted interventions to address these barriers. Studies from Ethiopia and other low-income settings have also highlighted the critical role of male involvement in improving maternal health outcomes and the need for tailored strategies to increase participation [20, 21]. These findings underscore the need for localized research to identify specific barriers and facilitators of male involvement in different contexts.

This study aimed to fill the existing research gap by evaluating the level of male involvement during ANC and its associated factors in the specified study area, incorporating additional parameters such as attitude. As we delved into the intricacies of male involvement during ANC, this research sought to provide valuable insights that could inform targeted interventions and contribute to the global effort to end preventable maternal mortality and morbidity [22].

Methods

Study Area

The study was conducted in Debre Tabor, a town located in the South Gondar Zone of the Amhara region in northwest Ethiopia. It is situated approximately 100 km from South East Gondar, 667 km from Addis Ababa (the capital of Ethiopia), and 97 km from Bahir Dar (the capital of the Amhara region). Debre Tabor has one comprehensive specialized hospital, three health centers, and six health posts serving the community. The town consists of six kebeles (local administrative units) and 36,285 households. According to the 2017 report by the Central Statistical Agency (CSA) of Ethiopia, the town has a population of 96,973, of which 49,753 are men and 47,220 are women [23]. A report from the Debre Tabor Health Administration indicated that 19,898 women of reproductive age reside in the town, and 2,194 women had a history of antenatal care (ANC) follow-up and delivery within the last six months.

Study Design and Period

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted from August to September 2022.

Population

Source Population

The source population consisted of all married men residing in Debre Tabor town whose wives had given birth within the last six months.

Study Population

The study population comprised all married men residing in randomly selected kebeles whose wives had given birth within the last six months.

Study Unit

The study unit included all randomly selected married men whose wives had given birth within the last six months.

Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion Criteria

All married men who live in the randomly selected kebeles whose wife gave birth within 6 months and had history of ANC utilization were included in the study.

Exclusion Criteria

Men, who can’t communicate due to serious illness, had mental disorder at the time of data collection and men who live less than 6 months in the town were excluded from the study.

Sample Size Determination

The sample size was calculated using single population proportion formula using the assumption of proportion from the study conducted in Bale on prevalence of male attendance and associated factors at ANC was 41.1% [6].

Then add 10% of non-response rate which gave a sample size of 410

n = sample size

w = marginal error (0.5)

z = confidence interval (CI) (95%)

p = proportion of male involvement during ANC (0.411).

Sampling Method and Procedure

To select the intended sample size 4 kebeles out of 6 were selected randomly and the eligible households in each kebele were obtained from health extension workers. The sample size of each kebele was proportionally allocated. The sampling interval of each kebele was calculated by dividing the number of eligible households for allocated sample size of that kebele.

Finally, participants were selected using systematic random sampling technique every Kth (4) interval for all kebeles by starting selection of the first participant by lottery method from 1–4 and subsequent participants were included randomly based on Kth interval. When the houses were closed at the time of data collection and men went out of home, the houses were coded and go back again to take information. When it was impossible again; it was replaced by the next eligible house. In houses, when there is more than one household or more than one married male, a single time balloting method was used to select one household as well as the study participant.

Operational Definitions

Male involvement in ANC

Refers to seeking ANC together at the facility, getting information from the health provider, decide together about what they do and where to go, provide financial and physical support during pregnancy [8]. It was measured as a composite measure using 6 items, which were equally weighted with dichotomized (yes/ no) components. To obtain the level of male involvement, each variable score “1” if performed and “0” if not and a total score was computed for each participant and the level of male involvement was classified as low level of involvement for those who score < = 2 and high level of involvement for those who score > = 3 [14].

Attitude of male involvement in ANC

The Attitude level of the study participants was determined by using attitude assessment questions with 5- point likert scale including “agree, strongly agree, disagree, strongly disagree, and neutral. Finally the attitude of participants was labeled based on mean score. Participants who scored greater than or equal to the mean score were considered as having a “positive” attitude whereas those who score less than the mean score were labeled as having a “ negative attitude [24].

Knowledge of ANC service

The knowledge level of the study participants was determined using knowledge assessment questions. A value of “1” and “0” was given for each correct and incorrect answer respectively and labeled as good knowledge and poor knowledge based on the mean score. Those participants who scored greater than or equal to the mean were considered as having “good knowledge” whereas those who score less than the mean were labeled as having a “poor knowledge [25].

Data Collection Tools

Development

Structured face-to-face interviewer-administered questionnaires were developed after a thorough review of relevant literature on male involvement in ANC. These questionnaires encompassed socio-demographic characteristics, male involvement in ANC, knowledge about ANC services, attitude and socio-cultural factors, and health facility-related factors.

Implementation

Trained personnel, including four male BSc midwives and two health extension workers, were tasked by the principal investigator (PI) with data collection and supervision. The selection of participants was conducted through systematic random sampling following an initial selection by lottery method.

Data Quality Management

Translation and Validation

Questionnaires underwent translation into the local language (Amharic) and subsequent back-translation into English to ensure consistency. Validation by experts in maternal health nursing was conducted, and the reliability of the instruments was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha (α > 0.7).

Training and Pretesting

Data collectors and supervisors underwent comprehensive training sessions conducted by the PI. A pretest was performed on a similar population, and questionnaires were scrutinized for completeness based on pretest outcomes.

Daily Monitoring and Correction

Regular meetings were convened to address challenges encountered during data collection and to monitor progress. Probing techniques were employed to mitigate recall and social desirability biases.

Data Processing and Analysis

Data were entered, categorized, and coded using Epi-data version 4.6 and analyzed in SPSS version 25. Descriptive analysis, including frequency and percentage calculations, was performed. Bi-variable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were carried out to ascertain associations. Multicollinearity was assessed using the variance inflation factor (VIF), ensuring values were < 1.5 to indicate no correlation between independent variables. Model fit was evaluated using Hosmer–Lemeshow statistics.

Ethical Consideration

Prior to the study, approval was sought and obtained from the institutional review board, adhering to the principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration. Support letters and permissions were secured from relevant authorities, and verbal consent was obtained from participants. Measures were implemented to maintain confidentiality and protect participants' rights throughout the study duration.

Results

Response Coverage

In the study conducted in Debre Tabor town, North West Ethiopia, a total of 404 study participants were included, yielding a response rate of 98.5%. Six participants were excluded from the analysis. Among the respondents, approximately 46.8% of men showed a high level of involvement in their wives' antenatal care, with a confidence interval (CI) ranging from 41.6% to 51.5%.

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

The mean age of the respondents was 35.8 years (SD ± 6.7), with the majority falling within the 26–35 years age group. Regarding religious affiliation, the majority identified as Orthodox Christians. Similarly, most respondents reported being in a monogamous marital status.

In terms of educational attainment, a notable proportion had received no formal education, while a significant portion were employed in government positions. The educational and employment status of spouses showed a similar trend, with a substantial number of wives being housewives. Additionally, a large percentage reported an average monthly family income exceeding 2000 Ethiopian birr (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants and their wives among married men whose wife gave birth within 6 months in Debre Tabor town, North West Ethiopia, 2023

| Variables (n = 404) | Category | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age category of husband | < = 25 | 15 | 3.7 |

| 26–35 | 196 | 48.5 | |

| 36–45 | 160 | 39.6 | |

| > = 46 | 33 | 8.2 | |

| Age category of wife | 18–25 | 87 | 21.5 |

| 26–35 | 262 | 64.9 | |

| > = 36 | 55 | 13.6 | |

| Age difference between husband and wife | Male younger or no age difference | 27 | 6.7 |

| Male older by 1–5 years | 167 | 41.3 | |

| Male older by 6–10 years | 178 | 44.1 | |

| Male older by > 10 years | 32 | 7.9 | |

| Religion of husband | Orthodox | 356 | 88.1 |

| Muslim | 32 | 7.9 | |

| Protestant | 16 | 4 | |

| Educational level of husband | Unable to read and write | 54 | 13.4 |

| Primary education | 96 | 23.8 | |

| Secondary education | 91 | 22.5 | |

| Diploma and above | 163 | 40.3 | |

| Educational level of wife | Unable to read and write | 39 | 9.7 |

| Primary education | 81 | 20 | |

| Secondary education | 79 | 19.6 | |

| Diploma and above | 205 | 50.7 | |

| Occupational status of husband | Government employee | 164 | 40.6 |

| Self-employee | 115 | 28.5 | |

| Trader | 125 | 30.9 | |

| Occupational status of wife | Housewife | 167 | 41.3 |

| Government employee | 117 | 29 | |

| Self-employee | 58 | 14.4 | |

| Trader | 62 | 15.3 | |

| Type of marriage | Religious marriage | 79 | 19.6 |

| Civil marriage | 116 | 28.7 | |

| Traditional marriage | 209 | 51.7 | |

| Number of marriage | Monogamous | 379 | 93.8 |

| Polygamous | 25 | 6.2 | |

| Income | < = 1000(low income) | 14 | 3.5 |

| 1001–2000(middle income) | 19 | 4.7 | |

| > 2000(high income) | 371 | 91.8 |

Men’s Involvement in ANC Service on Previous Pregnancy

Among respondents whose wives had previous pregnancies, 64.8% reported ANC attendance. Accompanying status showed that 46.6% of men accompanied their wives to previous ANC visits. Additionally, 90.1% of husbands lived with their spouses during pregnancy, and 91.1% of pregnancies were planned (Table 2).

Table 2.

Obstetric characteristics of respondents’ wives and their involvement in ANC service on previous pregnancy among males whose wife gave birth within 6 months in Debre Tabor town, North West Ethiopia, 2023

| Variables | Category | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Did your wife have another pregnancy before | Yes | 262 | 64.8 |

| No | 142 | 35.2 | |

| Did she attend ANC in her previous pregnancy(n = 262) | Yes | 247 | 94.3 |

| No | 15 | 5. 7 | |

| Did you accompany her previously for ANC visit(n = 262) | Yes | 122 | 46.6 |

| No | 140 | 53.4 | |

| How many times did you accompany your wife in the previous ANC visit(n = 122) | Once | 16 | 13.1 |

| Twice | 40 | 32.8 | |

| Three times | 41 | 33.6 | |

| More than three | 25 | 20.5 | |

| Total number of pregnancies of your wife(n = 404) | < = 2 | 270 | 66.8 |

| > 2 | 134 | 33.2 | |

| Total number of living children(n = 404) | One | 146 | 36.1 |

| 2–3 | 211 | 52.2 | |

| > = 4 | 47 | 11.7 | |

| Men lived with partner during pregnancy(n = 404) | Yes | 364 | 90.1 |

| No | 40 | 9.9 | |

| Lived together with other family member(n = 404) | Yes | 138 | 34.2 |

| No | 266 | 65.8 | |

| Was the recent pregnancy planned(n = 404) | Yes | 368 | 91.1 |

| No | 36 | 8.9 | |

| Did your wife have any complication during pregnancy(n = 404) | Yes | 77 | 19.1 |

| No | 327 | 80.9 |

Level of Male Involvement during ANC Care

While 46% of respondents accompanied their wives to ANC clinics, 54% did not, citing reasons such as job constraints and lack of information. Among those who accompanied their wives, the majority engaged in discussions with health providers about pregnancy-related matters and made joint emergency plans with their spouses. Financial and household support during pregnancy was also reported (Table 3).

Table 3.

Level of male involvement during ANC among married men whose wives gave birth within 6 months in Debre Tabor town, North West Ethiopia, 2023

| Variables | Category | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Did you accompany your wife to ANC clinic(n = 404 | Yes | 186(46) |

| No | 218(54) | |

| If no, why you didn’t you accompany her(n = 218) | Due to job | 134(61.5) |

| Not live together | 13(6) | |

| Lack of information | 45(20.6) | |

| Fear of HIV test | 16(7.3) | |

| Other | 10(4.6) | |

| If yes, how many ANC visits did you have with your wife?(n = 186) | Once | 33(17.7) |

| Two to three times | 137(73.7) | |

| Four or more times | 16(8.6) | |

| Did you enter the ANC counseling room(n = 186) | Yes | 150(80.6) |

| No | 36(19.4) | |

| Did you discuss with health provider on partner’s pregnancy(n = 150) | Yes | 123(82.1) |

| No | 27(17.9) | |

| Did you talk with your wife about pregnancy (n = 404) | Yes | 309(76.5) |

| No | 95(23.5) | |

| Did you make joint plan with your wife for emergency situation(n = 404) | Yes | 276(68.3) |

| No | 128(31.7) | |

| If “yes” what emergency preparation was made(n = 276) | 1. Put money aside pregnancy | 83(30.1) |

| 2. Made transport arrangements | 12(4.3) | |

| 3. Decide together where to go in cause of emergency | 13(4.7) | |

| 4. Remind her of ANC visits appointments | 11(4) | |

| 1and 2 | 33(12) | |

| 1and 3 | 22(8) | |

| 1,2 and 3 | 36(13) | |

| Perform all of the above listed preparations | 66(23.9) | |

| Did you provide financial support for ANC activities (n = 404) | Yes | 333(82.4) |

| No | 71(17.6) | |

| Did you help your wife by performing household chore(n = 404) | Yes | 241(59.7) |

| No | 163(40.3) | |

| Score for male involvement | Min | zero point |

| Max | 6 point | |

| Level of male involvement | High | 189(46.8) |

| Low | 215(53.2) |

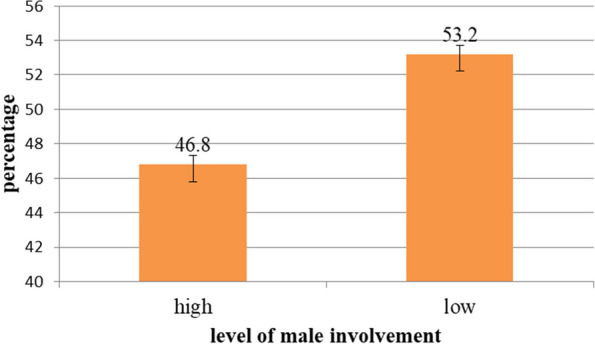

Overall Level of Male Involvement during ANC

Overall, only 46.8% of men were highly involved in their wives' ANC services (Figure 1).

Fig. 1.

The overall percentage distributions on the level of male involvement during ANC and associated factors among married men whose wives gave birth within 6 months in Debre Tabor town, North West Ethiopia, 2023(n = 404)

Men’s Knowledge about ANC Service

Approximately 36.3% of men demonstrated good knowledge about ANC services. Most had heard about ANC and recognized the need for multiple ANC visits during pregnancy. Knowledge about ANC components and their importance was also prevalent among respondents (Table 4).

Table 4.

Distribution of men’s Knowledge about ANC among men’s whose wife gave birth within 6 months in Debre Tabor town, North West Ethiopia, 2023

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Have you heard about ANC | ||

| Yes | 393 | 97.3 |

| No | 11 | 2.7 |

| If “Yes” what was your source of information | ||

| Media | 149 | 37.9 |

| Health professionals | 128 | 32.6 |

| Both | 104 | 26.5 |

| Other (friends, wife, books and magazine) | 12 | 3.1 |

| When should pregnant mother start ANC follow up | ||

| In the early trimester | 334 | 82.7 |

| Only when she is sick | 18 | 4.5 |

| After 3 month | 37 | 9.2 |

| Do not know | 15 | 3.7 |

| Number of ANC visit for Pregnant women | ||

| Once | 34 | 8.4 |

| Twice | 54 | 13.4 |

| Three and more | 316 | 78.2 |

| Do you know any ANC service? | ||

| Yes | 339 | 83.9 |

| No | 65 | 16.1 |

| Knowledge about ANC services | ||

|

Yes Frequency (%) |

No Frequency (%) |

|

| Pregnancy confirmation | 277(81.7) | 62(18.3) |

| FP counseling | 121(35.7 | 218(64.3) |

| TT immunization | 274(80.8) | 65(19.2) |

| Medical and nutritional counseling | 297(87.6) | 42(12.4) |

| Laboratory investigation (sugar, blood, urine, hepatitis etc.) | 269(79.4) | 70(20.5) |

| HIV test and counseling | 284(83.8) | 55(16.2) |

| STI screening and treatment | 263(77.6) | 76(22.4) |

| Birth preparedness and complication readiness | 269(79.4) | 70(20.6) |

| Monitor maternal blood pressure | 280(82.6) | 59(17.4) |

| Early detection of maternal and neonatal problem and treatment | 270(79.6) | 69(20.4) |

| Reduce complication during pregnancy and delivery | 292(86.1) | 47(13.9) |

| Prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV | 311(91.7) | 28(8.3) |

| Iron and folate supplementation | 32(97.3) | 11(2.7) |

| Monitoring maternal weight | 272(80.2) | 67(19.8) |

| Counseling on danger sign of pregnancy | 287(84.7) | 52(15.3) |

| Fetal growth monitoring | 292(86.1) | 47(13.9) |

| Knowledge on ANC service | Mean score | 16.9587 |

| Good knowledge | 123(36.3%) | |

| Poor knowledge | 216(63.7%) | |

Attitude of Male Involvement during ANC Service

A significant proportion of respondents expressed negative attitudes toward male involvement in ANC services, citing reasons such as considering pregnancy solely as a women's affair and societal taboos. However, some acknowledged the acceptability of male involvement in ANC (Table 5).

Table 5.

The level of attitude towards male involvement in ANC service among men whose wives gave birth within 6 months in Debre Tabor town, North West Ethiopia, 2023

| Statement | Responses | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agree | Strongly agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly disagree | |

| Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | |

| Pregnancy and child birth is natural phenomena | 187(46.2) | 176(43.6) | 2(0.5) | 270(6.7) | 12(3) |

| Pregnant women need regular medical checkup during pregnancy | 154(38.1) | 156(38.6) | 0(0) | 75(18.6) | 19(4.7) |

| Pregnancy is a woman’s affair,so there is no need for men involvement | 42(10.4) | 19(4.9) | 0(0) | 227(56) | 116(28.7) |

| Husband involvement in ANC visit considered as wastage of time | 82(20.3) | 28(6.9) | 2(0.5) | 203(50.2) | 89(22.1) |

| Husband is only responsible in taking decision about where and when to seek ante natal care | 69(17) | 10(2.6) | 5(1.2) | 242(59.9) | 78(19.3) |

| Dominance of antenatal clinic by female staff is the reason for male not getting involved | 34(8.4) | 25(6.2) | 2(0.5) | 252(62.4) | 91(22.5) |

| Men only go to ANC if they are requested by the health care provider | 72(17.8) | 30(7.4) | 1(0.2) | 236(58.4) | 65(16.2) |

| Male involvement in ANC hindered by socio-cultural beliefs | 52(12.9) | 22(5.4) | 11(2.7) | 139(34.4) | 180(44.6) |

| It is taboo /shame to accompany wife to the ANC clinic | 26(6.4) | 15(3.7) | 3(0.8) | 187(46.3) | 173(42.8) |

| A man who accompanies his wife to ANC is considered as weak in the community | 27(6.7) | 12(3) | 8(2) | 246(60.8) | 111(27.5) |

| A man who accompanies his wife/ partner to ANC acceptable in community | 154(38.1) | 84(20.8) | 190(4.7) | 77(19.1) | 70(17.3) |

| Male involvement in ANC is against faith/religion/tradition | 29(7.2) | 13(3.2) | 20(5) | 150(37.1) | 192(47.5) |

| Level of attitude | Positive | 185(45.8%) | |||

| negative | 219(54.2%) | ||||

Health Facility Related Factors

The majority of respondents reported positive experiences with health facility staff, minimal waiting times, and invitations to ANC examination rooms. Factors such as friendly staff attitudes and short waiting times contributed to favorable perceptions of health facilities (Table 6).

Table 6.

Distribution of health facility related factors among men who accompany their wife to ANC visit and whose wife gave birth within 6 months in Debre Tabor town, North West Ethiopia, 2023

| Variables | Responses | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude of the staff at the facility(n = 232) | Friendly | 199 | 85.8 |

| Unfriendly | 26 | 11.2 | |

| not sure | 7 | 3 | |

| Amount of time spent at the ANC clinic with partner(n = 232) | < 1 h | 185 | 79.7 |

| > 1 h | 47 | 20.3 | |

| Distance from your home to the ANC clinic on foot(n = 404) | < 30 min | 335 | 82.9 |

| > 30 min | 69 | 17.1 | |

| Lack of transportation(n = 404) | Yes | 89 | 22 |

| No | 315 | 78 | |

| Cost of transport(n = 404) | Expensive | 62 | 15.3 |

| Not expensive | 342 | 84.7 | |

| Invite into ANC examination room(n = 232) | Yes | 184 | 79.3 |

| No | 48 | 20.7 | |

| ANC clinic opened late and closed early(n = 232) | Yes | 37 | 15.9 |

| No | 195 | 84.1 |

Factors Associated with Level of Male Involvement during ANC Service

After controlling for potential confounding variables, several factors were found to be significantly associated with male involvement during ANC care. Adjusted Odds Ratios (AORs) were calculated to quantify the strength of association. The following factors emerged as significant predictors:

Respondents with secondary education were 1.5 times more likely to accompany their wives to ANC visits compared to those with no formal education (AOR = 1.5, 95% CI: 1.02–2.22).Similarly, respondents with higher education had 2.3 times higher odds of involvement compared to those with no formal education (AOR = 2.3, 95% CI: 1.24–4.31).Government employees were 1.8 times more likely to accompany their wives to ANC visits compared to those engaged in other occupations (AOR = 1.8, 95% CI: 1.04–3.12).

Respondents with good knowledge about ANC services had 2.5 times higher odds of involvement compared to those with poor knowledge (AOR = 2.5, 95% CI: 1.60–3.92).Men with a positive attitude towards male involvement in ANC services were 2.7 times more likely to accompany their wives compared to those with a negative attitude (AOR = 2.7, 95% CI: 1.73–4.19). Respondents who reported a friendly approach from health facility staff had 1.9 times higher odds of involvement compared to those who did not (AOR = 1.9, 95% CI: 1.09–3.31).Similarly, respondents who reported a waiting time of less than one hour had 1.6 times higher odds of involvement (AOR = 1.6, 95% CI: 1.02–2.48).

Age, religion, marital status, and income were not significantly associated with male involvement during ANC care after adjusting for other variables. (Table 7).

Table 7.

Bivariable and multivariable logistic regression of determinants on level of male involvement among married men’s whose wives gave birth within 6 months in Debre Tabor town, North West Ethiopia, 2023

| Variables | Level of male involvement N (%) | COR(95%CI) | AOR(95%CI) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||||

| Age of wife | ||||||

| 18–25 | 49(56.3) | 38(43.7) | 1.547(0.785,3.052) | 1.369(0.374, 5.015) | 0.636 | |

| 26–35 | 115(43.9) | 147(56.1) | 0.939(0.523,1.684) | 0.532(0.184,0. 1.540 | 0. 245 | |

| > = 36 | 25(45.5) | 30(54.5) | 1 | |||

| Number of marriage | ||||||

| Polygamous | 8(32) | 17(68) | 0.515(0.217,1.222) | 1.943(0.819,4.610) | 0.132 | |

| Monogamous | 181(47.8) | 198(52.2) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Educational level of husband | ||||||

| Primary education | 30(31.3) | 66(68.8) | 1.299(0.616,2.739) | 2.453(0.656,9.165) | 0.182 | |

| Secondary education | 35(38.5) | 56(61.5) | 1.786(0.851,3.746) | 4.052(1.043,15.736)* | 0.043 | |

| Diploma and above | 110(67.5) | 53(32.5) | 5.930(2.971,11.837) | 4.276(1.192,15.341)* | 0.026 | |

| Unable to read and write | 14(25.9) | 40(74.1) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Educational level of spouse | ||||||

| Primary education | 26(32.1) | 55(67.9) | 0.945(0.419,2.132) | 0.406(0.083,1.981) | 0.265 | |

| Secondary education | 32(40.5) | 47(59.5) | 1.362(0.610,3.040) | 0.632(0.132,3.021) | 0.565 | |

| Diploma and above | 118(57.6) | 87(42.) | 2.713(1.319,5.579) | 1.958(0.433,8.862) | 0.383 | |

| Unable to read and write | 13(33.3) | 26(66.7) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Occupational status of husband | ||||||

| Government Employee | 99(60.4) | 65(39.3) | 2.616(1.619,4.226) | 1.031(0.346,3.077) | 0.956 | |

| Self- employee | 44(38.3) | 71(61.7) | 1.064(0.631,1.796) | 0.399(0.150,1.060) | 0.065 | |

| Trader | 46(36.8) | 79(63.2) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Employment status of spouse | ||||||

| Housewife | 66(39.5) | 101(60.5) | 0.744(0.413,1.338) | 1.021(0.376,2.773) | 0.968 | |

| Government employee | 72(61.5) | 45(38.5) | 1.821(0.977,3.393) | 0.485(0.426,2.904) | 0.790 | |

| Self_employee | 22(37.9) | 36(62.1) | 0.695(0.336,1.440) | 1.007(0.260,3.897) | 0.992 | |

| Trader | 29(46.8) | 33(53.2) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Complication during pregnancy | ||||||

| Yes | 54(70.1) | 23(29.9) | 3.339(1.955,5.704) | 6.976(2.463,19.760)* | 0.000 | |

| No | 135(41.3) | 192(58.7) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Pregnancy status | ||||||

| Planned | 182(49.5) | 186(50.5) | 4.054(1.732,9.487) | 3.677 (0.818,16.539) | 0.09 | |

| Unplanned | 7(19.4) | 29(80.6) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Attitude | ||||||

| Positive | 97(52.4) | 88(47.6) | 1.522(1.026,2.256) | 2.365(1.108,5.046)* | 0.026 | |

| Negative | 92(42) | 127(58) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Couple live with other family member during pregnancy | ||||||

| No | 152(57.1) | 114(42.9) | 3.640(2.325, 5.697) | 4.461(2.022,9.845)* | 0.000 | |

| Yes | 37(26.8) | 101(73.2) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Time spent at ANC | ||||||

| < 1 h | 127(68.6) | 58(31.4) | 1.622(0.841,3.127) | 1.164(0.490,2.768) | 0.731 | |

| > 1 h | 27(57.4) | 20(42.6) | ||||

| Invite to ANC examination room | ||||||

| No | 22(45.8) | 26(54.2) | 0.316(0.164,0.607) | 0.370(0.155,0.882)* | 0.025 | |

| Yes | 134(72.8) | 50(27.2 | 1 | 1 | ||

P value is significant at < 0.05, 1 is the reference

Note: Variables marked with an asterisk (*) indicate significant associations at p < 0.05

Discussion

In this study, approximately 46.8% (CI: 41.6–51.5) of male partners exhibited high involvement in their wives' antenatal care (ANC). Factors such as the husband's educational status, complications during pregnancy, the couple's living situation during pregnancy, the husband's attitude toward male involvement in ANC, and invitation into the ANC room by healthcare professionals significantly influenced male involvement.

The observed rate of male involvement (46.8%) aligns closely with findings from a study in Buyende District, Uganda (51.1%) [26] and this also strengthen with the studies from Nigeria and Kenya have also demonstrated that male involvement can lead to better maternal and neonatal outcomes, with increased ANC attendance and higher rates of skilled birth attendance [25, 26]. This similarity suggests common socio-demographic characteristics and comparable assessment parameters, particularly regarding the educational level of husbands, which may play a pivotal role in influencing male involvement.

In contrast, our study's result surpasses findings from Wakiso District, Uganda (6%), Harari (19.7%), and North West Ethiopia (31.8%) [5, 7, 27]. The higher rate of involvement observed in our study may be attributed to recent advancements in Ethiopia's healthcare system, particularly initiatives emphasizing maternal, newborn, and child health. Additionally, differences in study settings, timeframes, and populations could contribute to the variations in male involvement rates reported across different studies.

Conversely, our study reports lower male involvement compared to studies in Bangladesh (60%), Indonesia (81.4%), western Butula of Kenya (55.5%), Kyela District of Tanzania (56.9%), Addis Ababa (65.5%), and Debre Berhan (62.5%) [28–33]. These discrepancies may be explained by socio-demographic differences, varying levels of infrastructure availability, and accessibility of healthcare services. In some regions, strategies such as mandatory husband accompaniment during ANC visits may also contribute to higher involvement rates.

Regarding independent variables, attending secondary education or holding a diploma and above increased the odds of male involvement by approximately 4 and 4.2 times, respectively. This finding aligns with similar studies in Nigeria, Bale, and North West Ethiopia, suggesting that education enhances knowledge and coping abilities, potentially enabling husbands to better understand their role in pregnancy [6, 7, 34]. This may indicate that the commonality of the problem especially in African regions as low education among husbands affects male involvement in contrast the higher education enhance the male involvements.

Men whose wives experienced pregnancy complications showed a significantly higher likelihood of involvement, with odds nearly 7 times greater than those whose wives did not face complications [32]. This may be attributed to increased awareness and counseling on pregnancy danger signs, prompting proactive involvement in ANC and development of pre exposed perceptions towards ANC service among couples.

Couples not living with other family members during pregnancy were about 4.5 times more likely to engage in ANC. This could be due to cultural norms assigning responsibility for pregnancy and delivery care to other family members, potentially deterring male involvement.

The absence of an invitation for the male partner to enter the ANC examination room reduced the odds of involvement by 63% [35]. Supportive healthcare workers have been shown to encourage male involvement during ANC, suggesting the importance of healthcare provider attitudes in facilitating participation.

Finally, respondents with a positive attitude toward male involvement were over 2.4 times more likely to engage compared to those with a negative attitude [23, 36]. Positive attitudes may encourage consistent support for ANC utilization and enhance maternal healthcare outcomes.

Conclusions

In conclusion, in this study male involvement is less half and this study underscores the importance of promoting male involvement in antenatal care (ANC). Factors such as education, pregnancy complications, living arrangements, attitude, and healthcare provider interaction significantly influence male participation. To enhance involvement, targeted educational campaigns, active engagement by healthcare providers, and community-based initiatives promoting positive attitudes toward male involvement are recommended. These efforts can lead to improved maternal and child health outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Debra Berhan University Asrat Woldeyes Health Science Campus (AWHSC) Ethical Review Board for providing the approval for this study (Ref.No/NURS/157/2014). Special thanks to the Department of Nursing at Debra Berhan University AWHSC for their support. The authors also extend their appreciation to the Debretabor Health Administration for granting permission to collect data. Additionally, the authors acknowledge the study participants for their cooperation and consent during the data collection process.

Authors’ contributions

S.H. and T.M. conceived and designed the study. S.H., T.M., and A.L. conducted the data collection. S.H. and T.M. performed the data analysis and interpretation. S.H., T.M., and A.L. contributed to the writing and revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received by any of the authors for this specific study.

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Before conducting the study, approval was obtained from the Debra Berhan University Asrat Woldeyes Health Science Campus (AWHSC) Ethical Review Board with the approval number Ref.No/NURS/157/2014. Additionally, support letters were obtained from the Debra Berhan University AWHSC Department of Nursing, and permission letters were secured from the Debretabor Health Administration to collect data. Verbal consent was obtained from all study participants prior to data collection, and their confidentiality was strictly maintained throughout the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Organization WH. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. World Health Organization; 2016. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549912. Accessed 2023 Mar 13. [PubMed]

- 2.Ghabbour SI. United Nations International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD), held in the International Conference Centre, Cairo, Egypt, during 5–13 September 1994. Environ Conserv. 1994;21(3):283–4. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spivak GC. ‘Woman’ as theatre-United Nations Conference on Women, Beijing 1995-Commentary. Radical Philos. 1996;75:3–5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Organization WH. WHO recommendations on health promotion interventions for maternal and newborn health. World Health Organization; 2015. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241508742. Accessed 2023 Mar 15. [PubMed]

- 5.Asefa F, Geleto A, Dessie Y. Male partners involvement in maternal ANC care: the view of women attending ANC in Harari public health institutions, eastern Ethiopia. Sci J Public Health. 2014;2(3):182–8. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fetene K, et al. Prevalence of male attendance and associated factors at their partners’ antenatal visits among antenatal care attendees in Bale Zone, South East Ethiopia. Int J Nurs Midwifery. 2018;10(9):109–20. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adane HA, et al. Prevalence of husband antenatal care attendance and associated factors among husbands whose wives gave birth in the last twelve months in Enebsiesarmider District, Northwest Ethiopia. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Atiibugri JS. Determinants of male involvement in antenatal care in the Bawku municipality. Upper East region Ghana: University of Ghana; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masaba BB, Mmusi-Phetoe RM. Barriers to and Opportunities for Male Partner Involvement in Antenatal Care in Efforts to Eliminate Mother-to-child Transmission of Human Immunodeficiency Virus in Kenya: Systematic Review. Open Nurs J. 2020;14:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doyle K, Kato-Wallace J. Male engagement in maternal, newborn, and child Health. Sexual Reproductive Health and Rights. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peneza AK, Maluka SO. ‘Unless you come with your partner you will be sent back home’: strategies used to promote male involvement in antenatal care in Southern Tanzania. Glob Health Action. 2018;11(1):1449724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tesfaye G, Chojenta C, Smith R, Loxton D. Delaying factors for maternal health service utilization in eastern Ethiopia: A qualitative exploratory study. Women Birth. 2020;33(3):e216–26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.WHO. Maternal mortality. 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/maternal-mortality. Accessed 2023 Mar 18.

- 14.Kumbeni MT, et al. Factors influencing male involvement in antenatal care in the Kassena Nankana Municipal in the Upper East Region. Ghana Eur Sci J. 2019;15(21):21–31. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kabanga E, et al. Prevalence of male partners involvement in antenatal care visits – in Kyela district, Mbeya. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.WHO, UN. Maternal mortality: Levels and trends 2000 to 2017. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/maternal-mortality-2000-2017/en/. Accessed 2023 Mar 20.

- 17.Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey. World Health Organization; 2017 Jul. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR328/FR328.pdf. Accessed 2022 Mar 13.

- 18.Mengistu T, Worku A, Addis H. The role of male involvement in antenatal care services and its impact on maternal health outcomes in Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2022;32(3):375–88. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yargawa J, Leonardi-Bee J. Male involvement in antenatal care and birth outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28(8):823–8.24920284 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tadesse T, Gebremariam A, Ayele S. Factors influencing male involvement in maternal health care in rural Ethiopia. J Public Health Res. 2020;9(2):215–25. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Biruk B, Assefa N, Dejene G. Barriers to male involvement in antenatal care in Ethiopia: A qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):326–37.33902483 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ayalew M, et al. Determinants of male partner involvement towards prevention of mother to child transmission service utilization among pregnant women who attended focused antenatal care in Southern Ethiopia. HIV AIDS (Auckl). 2020;12:87–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Central Statistical Agency. Population Projection of Ethiopia for All Regions At Wereda Level from 2014–2017. Available from: http://www.csa.gov.et. Accessed 15 Jan 2022.

- 24.Adamolekun MM, Adewoyin FR, Ojo IC, Yunusa OZ. Men’s Knowledge and Attitude Towards Male Involvement in Antenatal Care in Akure South, Ondo State. Afr J Health Nurs Midwifery. 2020;3(3):56–65. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gibore NS, Gesase AP. Men in maternal health: an analysis of men’s views and knowledge on, and challenges to, involvement in antenatal care services in a Tanzanian community in Dodoma Region. J Biosoc Sci. 2021;53(6):805–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alupo P, et al. Male Partner Involvement In The Utilization Of Antenatal Care Services In Kidera, Buyende District. Uganda: Cross Sectional Mixed Methods Study; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kariuki KF, Seruwagi GK. Determinants of male partner involvement in antenatal care in Wakiso District. Uganda Br J Med Med Res. 2016;18(7):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bishwajit G, et al. Factors associated with male involvement in reproductive care in Bangladesh. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):3–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ibnu IN, Asyary A. Associated Factors of Male Participation in Antenatal Care in Muaro Jambi District. Indonesia J Pregnancy. 2022;2022:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ongolly FK, Bukachi SA. Barriers to men’s involvement in antenatal and postnatal care in Butula, western Kenya. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2019;11(1):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shine S, et al. Magnitude and associated factors of husband involvement on antenatal care follow up in Debre Berhan town. Ethiopia BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Umer ZM, Sendo EG. Attitude and Involvement of Male Partner in Maternal Health Care in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a Cross-sectional Study. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mamo ZB, et al. Determinants of male partner involvement during antenatal care among pregnant women in Gedeo Zone, South Ethiopia: a case-control study. Ann Glob Health. 2021;87(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nwakwuo GC, Oshonwoh FE. Assessment of the level of male involvement in safe motherhood in southern Nigeria. J Community Health. 2013;38(2):349–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davis J, et al. Expectant fathers’ participation in antenatal care services in Papua New Guinea: a qualitative inquiry. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dahake S, Shinde R. Exploring husband’s attitude towards involvement in his wife’s antenatal care in urban slum community of Mumbai. Indian J Community Med. 2020;45(3):320–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.