Abstract

Background

The role of diet in breast cancer prevention is controversial and limited in low-middle-income countries (LMICs). This study aimed to investigate the association between different dietary factors and breast cancer risk in Vietnamese women.

Methods

Three hundred seventy newly histologically confirmed breast cancer cases and 370 controls matched by 5-year age from September 2019 to March 2020 in Ho Chi Minh City were recorded dietary intake using a validated food frequency questionnaire. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were evaluated using conditional logistic regression and adjusted with potential confounders.

Results

Compared to the lowest quartile of intake, we found that the highest intake of vegetables, fruit, soybean products, coffee, and egg significantly decreased breast cancer risk, including dark green vegetables (OR 0.46, 95% CI 0.27-0.78, ptrend=0.022), legumes (OR 0.19, 95% CI 0.08-0.44, ptrend <0.001), starchy vegetables (OR 0.37, 95% CI 0.21-0.66, ptrend=0.003), other vegetables (OR 0.46, 95% CI 0.28-0.77, ptrend=0.106), fruits (OR 0.44, 95% CI 0.26-0.74, ptrend <0.001), soybean product (OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.24-0.86, ptrend=0.311), coffee (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.23-0.95, ptrend 0.004), and egg (OR 0.4, 95% CI 0.23-0.71, ptrend=0.002).

Conclusion

Greater consumption of vegetables, fruit, soybean products, coffee, and eggs is associated with a lower risk of breast cancer. This study provides evidence of breast cancer prevention by increasing the intake of these dietary groups, especially in LMICs.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12885-024-12918-y.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Diet, Risk factor, Vietnam

Background

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in females worldwide, contributing to 2,3 million new cases and 684,996 cancer-related deaths [1]. In Vietnam, breast cancer has also been a profound burden to the healthcare system, accounting for the highest age-standardized incidence rates (34.2 per 100,000 populations) and among the top three age-standardized mortality rates (13.8 per 100,000 populations) [2]. Moreover, breast cancer incidence rates have continuously increased over the past 20 years, which presents a significant public health challenge for Vietnam [3]. Identifying modifiable risk factors specific to the Vietnamese context is crucial for developing effective preventive strategies to combat this growing health concern.

Among modifiable risk factors of breast cancer, diet stands out as a potential factor for breast cancer prevention to reduce the burden. In vitro, many nutritional constituents from the diet have shown their influence on breast cancer onset and development through different mechanisms: gene mutation and repair, cell proliferation and apoptosis, antioxidant activities, inflammation, and levels of sex hormones [4].

A number of epidemiology studies have been conducted to assess the dietary factors concerning breast cancer risk and arrived at various conclusions. Some studies found that higher intakes of vegetables, fruit, milk, egg, soy food, and lower intakes of high-cholesterol food, grilled and processed meat were inversely associated with breast cancer [5–9]. Nevertheless, except for alcohol, no dietary factors have shown a consistent and statistically robust association with breast cancer risk [10].

Regional differences might play a role in varying associations between breast cancer risk and diet, and few studies are available from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [11–13] where variability in food intake is wide [14]. In Vietnam, limited research has explored the association between dietary factors and breast cancer risk, with only one study conducted in the Northern region[12]. To address this gap, we conducted a case-control study in Ho Chi Minh City, Southern Vietnam, to investigate the relationship between specific food groups and breast cancer risk among women.

This knowledge can contribute significantly to developing targeted dietary recommendations and public health initiatives aimed at reducing breast cancer risk in this population.

Methods

Study population and design

Case subjects were recruited from September 2019 to March 2020 from patients admitted to the Ho Chi Minh City Oncology Hospital, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. 419 potential cases, who were Vietnamese females aged 25 years and older with newly histologically confirmed primary breast cancer diagnosed at Ho Chi Minh City Oncology Hospital, were identified. Women were excluded if they had a prior history of any cancers. Controls for the present study were randomly selected from the cohort of participants in the Vietnam Osteoporosis Study (VOS), whose rationale and protocol have been described elsewhere [15]. This project is a prospective cohort study that has been collecting roughly 4200 random citizens aged 18 years and above in Ho Chi Minh City and surrounding rural areas. The cancer-free status of the selected controls was assessed by continuous medical records in six years of follow-up in the cohort. The controls were frequently matched by a 5-year age group to the cases on a 1:1 ratio. For each age bracket, a sample of control candidates of the required size was generated randomly using the base R sample function. A final sample of 370 cases and 370 controls were selected for statistical analyses.

Ho Chi Minh City contributes significantly to Vietnam’s economy, making up about 27% of the country's overall budget and 23% of the gross domestic product in 2020 [16]. With those great employment opportunities, Ho Chi Minh City has become the most attractive destination for the migrant labor force in Vietnam. It is estimated that there were 200 immigrants per 1,000 people in Ho Chi Minh City, coming from the Mekong River Delta, the North Central, and Central Coastal areas [17].

All women who participated in this study provided written informed consent. The study was approved by the National Ethics Committee of the Vietnam Ministry of Health (Approval: 94/CN-HDDD issued on August 7th, 2020).

Data collection

Detailed information on dietary habits and other factors (sociodemographic characteristics, weight, height, menstrual and reproductive history, physical activity, and family history of breast cancer) among the participants was elicited by face-to-face interviews using a structured questionnaire conducted by trained interviewers. The feasibility and reliability of the questionnaire were evaluated through two separate tests. Initially, the questionnaire was administered to 20 randomly selected individuals from the community, with a two-week interval between tests. The resulting coefficient of reliability ranged from 0.60 to 0.79, indicating moderate to good reliability. Subsequently, adjustments were made to questions exhibiting high variability. Next, the questionnaire was tested on 20 patients at the Ho Chi Minh City Oncology Hospital, with an interval of approximately four weeks between tests corresponding to the interval between two follow-up examinations. During this test, the reliability coefficient improved significantly, ranging from 0.75 to 0.90, indicating good to excellent reliability. Unfortunately, due to the limited sample size, reliability analysis by age group was not feasible.

The sociodemographic characteristics were age and education level, which resulted from the question, ‘What is your highest education attainment?’ with four possible answers, ‘Primary school or lower,’ ‘Secondary school,’ ‘High school,’ ‘College or higher.’ The menstrual and reproductive history included information about the age at menarche, age at first birth, parity, menopausal status, benign breast disease, and oral contraceptive use. Physical activity was assessed using the Global physical activity questionnaire [18]. Participants’ height and weight were measured using an electronic portable, wall-mounted stadiometer (Seca Model 769; Seca Corp, CA, USA) while not wearing shoes, ornaments, hats, or heavy layer clothing. For the case group, we retrieved information on the participant’s weight before the surgical operation from the medical record. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by height in meters squared (kg/m2). BMI was classified into four categories (<18.5, 18.5-23, 23-27.5, >27.5 kg/m2) based on the cut-off for Asians by the World Health Organization [19].

Dietary intakes were assessed using a validated 76-item food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) with good reproducibility (Spearman correlation coefficients ranged from 0.47 to 0.72) [20]. A commonly used portion size was specified for each food (e.g., slice, glass, bowl, or unit, such as one apple or banana). Food picture booklets with usual intake portions [20] were utilized to help participants estimate and record amounts of food consumed (Supplementary Table S1, Supplementary material 2). The development and validation of the FFQ among Vietnamese in Ho Chi Minh City were described elsewhere [20]. Food items were categorized into food groups based on their similar nutrient contents, including: dark green vegetables (i.e., amaranth, swamp cabbage, mustard green, water morning glory, Malabar spinach, crown daisy, Chinese leek, broccoli), red/orange vegetables (i.e., tomato, carrot, pumpkin squash, red pepper, bell pepper), legumes (French bean, ), starchy vegetables (i.e., white potato, sweet potato, Chinese yam), other vegetables (i.e., cabbage, wax gourd, cucumber, gourd, bitter gourd, mushroom), fruits (i.e., dragon fruit, banana, papaya, pomelo, mango, durian, jackfruit, longan, orange, water melon, pear, grape, guava, apple), red meat (i.e., pork lean, pork upper leg, pork medium fat, pork rib, pork lower leg, beef), white meat (i.e., chicken, duck, hen), innards, seafood (i.e., fish, shrimp, squid), egg (i.e., hen egg, duck egg), soybean products (i.e., fried tofu, raw tofu, tofu pudding), tea, dairy beverages (i.e., fresh milk, milk powder, yogurt, condensed milk, soybean milk), soft drink, fruit juice (i.e., fruit shake juice, lemon juice, orange juice, coconut juice with kernel), and coffee (i.e., coffee, instant coffee, instant coffee with milk and sugar). The reference period in assessing diet factors was one year before diagnosis for cases and one year before being interviewed for controls. Information on consumption frequency (four levels: daily, weekly, monthly, yearly) and the number of servings for each food consumed during the previous three-year period were obtained.

Statistical analysis

Characteristics between cases and controls were compared using the t-test or Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables. Quartiles of food group intakes were defined based on the distribution among the control group. Conditional logistic regression models were used to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of each quartile, using the lowest quartile group as the reference. The relationships between different food groups and the risk of breast cancer were further examined after adjusting for various potential confounding variables using multivariate logistic regression models. The following potential confounding factors were included in the models: age (continuous), education level (secondary school and lower, high school and higher), body mass index (BMI, <18.5, 18.5-23, 23-27.5, >27.5 kg/m2), age at menarche (continuous), age at first birth (continuous), parity (nulliparous, 1, 2, ≥3 births), menopausal status (yes: has been postmenopausal, no: not yet), history of benign breast disease (yes/no), oral contraceptive use (ever, yes/no), physical activity (≥3 times/week, yes/no), family history of breast cancer (yes/no). Age (continuous) was also included in the final conditional logistic regression model following the theory of doubly robust estimation [21].

All P values are two-sided, and the statistical significance level was determined at p <0.05. All data analyses were performed by using R 4.1.2 [13].

Results

The selected characteristics of 370 cases and 370 controls participating in the study are presented in Table 1. The mean age of the case and control groups were both 51.7 years. Compared to controls, cases were more likely to have lower education level, lower BMI, older age at menarche, younger age at first birth, higher parity, and were more physically active. Controls were more likely to reside in urban areas. There were no significant differences between the cases and controls in terms of menopausal status, history of benign breast disease, ever oral contraceptive use, and family history of breast cancer.

Table 1.

Selected characteristics of breast cancer cases and controls, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

| Characteristics | Cases (n=370) | Controls (n=370) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Mean ± SD) | 51.7 ± 10.8 | 51.7 ± 10.9 | 0.93 |

| Residence (n, %) | |||

| Urban | 124 (33.3%) | 326 (88.1%) | <0.01 |

| Rural | 246 (66.7%) | 44 (11.9%) | |

| Education level (n, %) | |||

| Secondary school and lower | 273 (73.8%) | 190 (51.4%) | <0.01 |

| High school and higher | 97 (26.2%) | 180 (48.6%) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||

| <18.5 | 27 (7.3%) | 15 (4.1%) | <0.01 |

| 18.5-23 | 183 (49.5%) | 143 (38.6%) | |

| 23-27.5 | 127 (34.3%) | 161 (43.5%) | |

| >27.5 | 33 (8.9%) | 51 (13.8%) | |

| Age of menarche (Mean ± SD) | 15.3 ± 1.81 | 14.6 ± 1.93 | <0.01 |

| Age at first birth (Mean ± SD) | 24.6 ± 4.83 | 26.0 ± 5.07 | <0.01 |

| Number of parity (n, %) | |||

| Nulliparious | 46 (12.4%) | 76 (20.5%) | <0.01 |

| 1 | 48 (13.0%) | 63 (17.0%) | |

| 2 | 161 (43.5%) | 145 (39.2%) | |

| ≥3 | 115 (31.1%) | 86 (23.2%) | |

| Gravidity (Mean ± SD) | 2.54 (1.59) | 2.26 (1.74) | 0.03 |

| Menopause status (Yes, %) | 196 (53.0%) | 187 (50.5%) | 0.56 |

| History of benign breast disease | 20 (5.4%) | 9 (2.4%) | 0.06 |

| Oral contraceptive use, ever | 18 (4.9%) | 13 (3.5%) | 0.46 |

| Physical activity: ≥3 times/week | 203 (54.9%) | 157 (42.4%) | <0.01 |

| Family history of breast cancer (Yes, %) | 17 (4.6%) | 18 (4.9%) | 1 |

Table 2 shows the intake of food groups for each quartile with the participant distribution and their crude ORs. Compared to controls, the case group had lower participants in both quartiles 3 and 4 of food intake regarding dark green vegetables, red/orange vegetables, legumes, starchy vegetables, other vegetables, egg, soybean products, tea, dairy beverages, and coffee. Otherwise, only white meat and innards witnessed more participants in the case than the control in both quartiles 3 and 4 of food intake.

Table 2.

The participant distribution and crude odds ratios for the association of breast cancer across the quartiles of food group intakes

| Food intakes | Cases (n =370) | Controls (n =370) | Crude OR (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dark green vegetables | ||||

| Quartile 1: <3.75 servings/week | 103 (27.84) | 66 (17.84) | 1.00 | |

| Quartile 2: 3.75 - <6.02 servings/week | 94 (25.41) | 80 (21.62) | 0.75 (0.49-1.16) | 0.19 |

| Quartile 3: 6.02 - <9.69 servings/week | 84 (22.70) | 102 (27.57) | 0.53 (0.35-0.81) | <0.01 |

| Quartile 4: ≥9.69 servings/week | 89 (24.05) | 122 (32.97) | 0.47 (0.31-0.71) | <0.01 |

| Red/Orange vegetables | ||||

| Quartile 1: <1.75 servings/week | 82 (22.16) | 95 (25.68) | 1.00 | |

| Quartile 2: 1.75 - <3.09 servings/week | 112 (30.27) | 74 (20.00) | 1.75 (1.16-2.66) | <0.01 |

| Quartile 3: 3.09 - <5.33 servings/week | 108 (29.19) | 110 (29.73) | 1.14 (0.76-1.69) | 0.52 |

| Quartile 4: ≥5.33 servings/week | 68 (18.38) | 91 (24.59) | 0.87 (0.56-1.33) | 0.51 |

| Legumes | ||||

| Quartile 1: <0.06 servings/week | 106 (28.65) | 61 (16.49) | 1.00 | |

| Quartile 2: 0.06 - <0.32 servings/week | 140 (37.84) | 123 (33.24) | 0.65 (0.44-0.97) | 0.04 |

| Quartile 3: 0.32 - <1.21 servings/week | 109 (29.46) | 144 (38.92) | 0.44 (0.29-0.65) | <0.01 |

| Quartile 4: ≥1.21 servings/week | 15 (4.05) | 42 (11.35) | 0.21 (0.11-0.40) | <0.01 |

| Starchy vegetables | ||||

| Quartile 1: <0.75 servings/week | 160 (43.24) | 85 (22.97) | 1.00 | |

| Quartile 2: 0.75 - <1.96 servings/week | 78 (21.08) | 112 (30.27) | 0.37 (0.25-0.55) | <0.01 |

| Quartile 3: 1.96 - <3.62 servings/week | 82 (22.16) | 111 (30.00) | 0.39 (0.27-0.58) | <0.01 |

| Quartile 4: ≥3.62 servings/week | 50 (13.51) | 62 (16.76) | 0.43 (0.27-0.68) | <0.01 |

| Other vegetables | ||||

| Quartile 1: <3.33 servings/week | 107 (28.92) | 67 (18.11) | 1.00 | |

| Quartile 2: 3.33 - <5.38 servings/week | 90 (24.32) | 91 (24.59) | 0.62 (0.41-0.94) | 0.03 |

| Quartile 3: 5.38 - <8.23 servings/week | 92 (24.86) | 95 (25.68) | 0.61 (0.40-0.92) | 0.02 |

| Quartile 4: ≥8.23 servings/week | 81 (21.89) | 117 (31.62) | 0.43 (0.29-0.66) | <0.01 |

| Fruits | ||||

| Quartile 1: <4.84 servings/week | 113 (30.54) | 77 (20.81) | 1.00 | |

| Quartile 2: 4.84 - <8.88 servings/week | 100 (27.03) | 84 (22.70) | 0.81 (0.54-1.22) | 0.32 |

| Quartile 3: 8.88 - <15.28 servings/week | 95 (25.68) | 88 (23.78) | 0.74 (0.49-1.11) | 0.14 |

| Quartile 4: ≥15.28 servings/week | 62 (16.76) | 121 (32.70) | 0.35 (0.23-0.53) | <0.01 |

| Red meat | ||||

| Quartile 1: <4.66 servings/week | 109 (29.46) | 94 (25.41) | 1.00 | |

| Quartile 2: 4.66 - <8.65 servings/week | 71 (19.19) | 93 (25.14) | 0.66 (0.43-0.99) | 0.04 |

| Quartile 3: 8.65 - <15.83 servings/week | 106 (28.65) | 98 (26.49) | 0.93 (0.63-1.38) | 0.73 |

| Quartile 4: ≥15.83 servings/week | 84 (22.70) | 85 (22.97) | 0.85 (0.57-1.28) | 0.44 |

| White meat | ||||

| Quartile 1: <0.89 servings/week | 111 (30.00) | 108 (29.19) | 1.00 | |

| Quartile 2: 0.89 - <2.21 servings/week | 92 (24.86) | 133 (35.95) | 0.67 (0.46-0.98) | 0.04 |

| Quartile 3: 2.21 - <5.42 servings/week | 100 (27.03) | 83 (22.43) | 1.17 (0.79-1.74) | 0.43 |

| Quartile 4: ≥5.42 servings/week | 67 (18.11) | 46 (12.43) | 1.42 (0.89-2.24) | 0.14 |

| Innard | ||||

| Quartile 1: <5.75 servings/week | 214 (57.84) | 248 (67.03) | 1.00 | |

| Quartile 2: 5.75 - <23.01 servings/week | 49 (13.24) | 40 (10.81) | 1.42 (0.90-2.24) | 0.13 |

| Quartile 3: 23.01 - <57.54 servings/week | 59 (15.95) | 43 (11.62) | 1.59 (1.03-2.45) | 0.04 |

| Quartile 4: ≥57.54 servings/week | 48 (12.97) | 39 (10.54) | 1.43 (0.90-2.26) | 0.13 |

| Seafood | ||||

| Quartile 1: <3.74 servings/week | 94 (25.41) | 104 (28.11) | 1.00 | |

| Quartile 2: 3.74 - <6.01 servings/week | 96 (25.95) | 83 (22.43) | 1.28 (0.85-1.92) | 0.23 |

| Quartile 3: 6.01 - <9.65 servings/week | 91 (24.59) | 98 (26.49) | 1.03 (0.69-1.53) | 0.89 |

| Quartile 4: ≥9.65 servings/week | 89 (24.05) | 85 (22.97) | 1.16 (0.77-1.74) | 0.48 |

| Egg | ||||

| Quartile 1: <1.01 servings/week | 139 (37.57) | 79 (21.35) | 1.00 | |

| Quartile 2: 1.01 - <2.62 servings/week | 102 (27.57) | 116 (31.35) | 0.50 (0.34-0.73) | <0.01 |

| Quartile 3: 2.62 - <4.62 servings/week | 84 (22.70) | 102 (27.57) | 0.47 (0.31-0.70) | <0.01 |

| Quartile 4: ≥4.62 servings/week | 45 (12.16) | 71 (19.19) | 0.36 (0.23-0.57) | <0.01 |

| Soybean product | ||||

| Quartile 1: <0.46 servings/week | 119 (32.16) | 62 (16.76) | 1.00 | |

| Quartile 2: 0.46 - <1.55 servings/week | 155 (41.89) | 151 (40.81) | 0.53 (0.37-0.78) | <0.01 |

| Quartile 3: 1.55 - <3.68 servings/week | 58 (15.68) | 99 (26.76) | 0.31 (0.20-0.48) | <0.01 |

| Quartile 4: ≥3.68 servings/week | 38 (10.27) | 58 (15.68) | 0.34 (0.20-0.57) | <0.01 |

| Tea | ||||

| Quartile 1: <0.17 servings / day | 244 (65.95) | 195 (52.70) | 1.00 | |

| Quartile 2: 0.17 - <0.57 servings / day | 24 (6.49) | 38 (10.27) | 0.50 (0.29-0.87) | 0.01 |

| Quartile 3: 0.57 - <3 servings / day | 61 (16.49) | 90 (24.32) | 0.54 (0.37-0.79) | <0.01 |

| Quartile 4: ≥3 servings / day | 41 (11.08) | 47 (12.70) | 0.70 (0.44-1.10) | 0.12 |

| Dairy beverages | ||||

| Quartile 1: <2.82 servings/week | 224 (60.54) | 161 (43.51) | 1.00 | |

| Quartile 2: 2.82 - <8.89 servings/week | 54 (14.59) | 91 (24.59) | 0.43 (0.29-0.63) | <0.01 |

| Quartile 3: 8.89 - <22.09 servings/week | 52 (14.05) | 77 (20.81) | 0.49 (0.32-0.73) | <0.01 |

| Quartile 4: ≥22.09 servings/week | 40 (10.81) | 41 (11.08) | 0.70 (0.43-1.13) | 0.15 |

| Soft drink | ||||

| Quartile 1: <0.12 servings/week | 253 (68.38) | 244 (65.95) | 1.00 | |

| Quartile 2: 0.12 - <0.58 servings/week | 72 (19.46) | 75 (20.27) | 0.93 (0.64-1.34) | 0.68 |

| Quartile 3: 0.58 - <2.12 servings/week | 27 (7.30) | 33 (8.92) | 0.79 (0.46-1.35) | 0.39 |

| Quartile 4: ≥2.12 servings/week | 18 (4.86) | 18 (4.86) | 0.96 (0.49-1.90) | 0.92 |

| Fruit juice | ||||

| Quartile 1: <1.03 servings/week | 150 (40.54) | 120 (32.43) | 1.00 | |

| Quartile 2: 1.03 - <2.53 servings/week | 90 (24.32) | 95 (25.68) | 0.76 (0.52-1.10) | 0.15 |

| Quartile 3: 2.53 - <5.53 servings/week | 79 (21.35) | 78 (21.08) | 0.81 (0.55-1.20) | 0.29 |

| Quartile 4: ≥5.53 servings/week | 51 (13.78) | 77 (20.81) | 0.53 (0.35-0.81) | <0.01 |

| Coffee | ||||

| Quartile 1: <0.24 servings/week | 210 (56.76) | 181 (48.92) | 1.00 | |

| Quartile 2: 0.24 - <1.38 servings/week | 33 (8.92) | 29 (7.84) | 0.98 (0.57-1.68) | 0.94 |

| Quartile 3: 1.38 - <7.24 servings/week | 101 (27.30) | 126 (34.05) | 0.69 (0.50-0.96) | 0.03 |

| Quartile 4: ≥7.24 servings/week | 25 (6.76) | 34 (9.19) | 0.63 (0.36-1.10) | 0.11 |

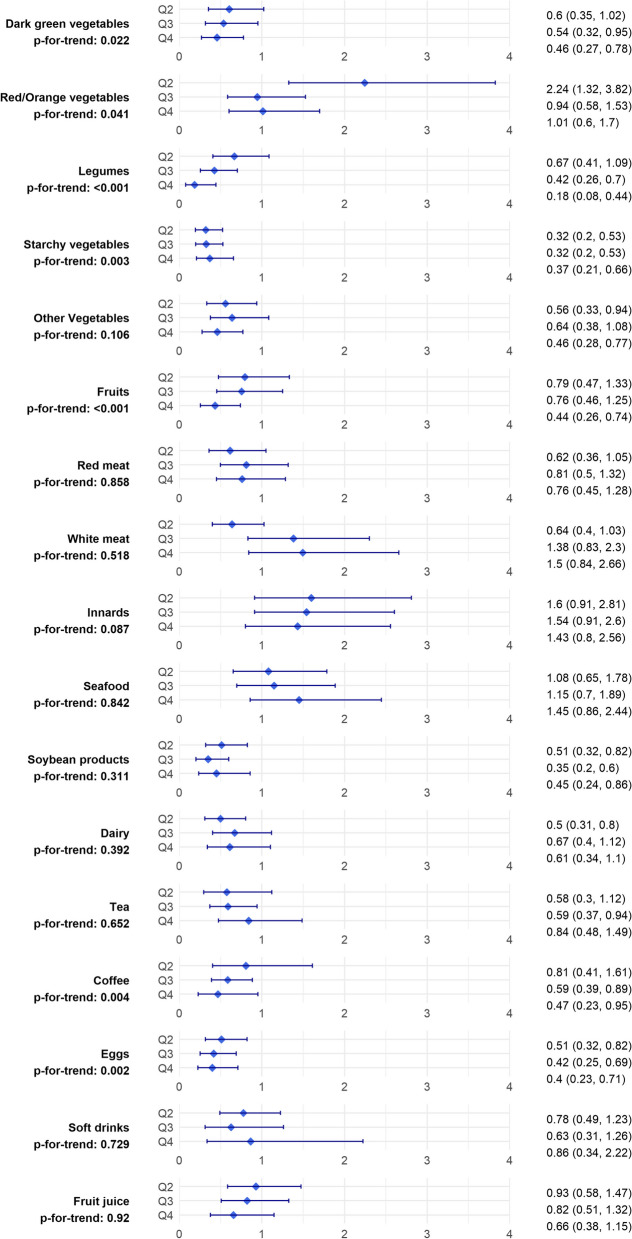

Figure 1 illustrates the adjusted ORs of breast cancer for intake of food groups across quartiles. Comparing the highest with the lowest quartile, the breast cancer risk decreased significantly with respect to dark green vegetables (OR 0.46, 95% CI 0.27-0.78, ptrend=0.022), legumes (OR 0.19, 95% CI 0.08-0.44, ptrend <0.001), starchy vegetables (OR 0.37, 95% CI 0.21-0.66, ptrend=0.003), other vegetables (OR 0.46, 95% CI 0.28-0.77, ptrend=0.106), fruits (OR 0.44, 95% CI 0.26-0.74, ptrend <0.001), soybean product (OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.24-0.86, ptrend=0.311), coffee (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.23-0.95, ptrend 0.004), and egg (OR 0.4, 95% CI 0.23-0.71, ptrend=0.002). Red/orange vegetables, red meat, white meat, innards, seafood, dairy, tea, soft drinks, and fruit juice showed no significant association with breast cancer risk in comparison between the highest and lowest intake categories.

Fig. 1.

Adjusted* odds ratios and their 95% confidence intervals for the association of breast cancer across the quartiles of food group intakes. *The ORs are adjusted for: age, education level, body mass index, age at menarche, age at first birth, parity, menopausal status, history of benign breast disease, oral contraceptive use, physical activity, and family history of breast cancer. Q: quartile

Discussion

The present study investigated the association between various dietary factors and breast cancer risk among Vietnamese women in Ho Chi Minh City. Our findings, after adjusting for potential confounding factors, revealed that high intakes of dark green vegetables, legumes, starchy vegetables, other vegetables, fruits, soybean products, coffee, and eggs significantly reduced breast cancer risk. Conversely, no statistically significant associations were observed between high consumption of red/orange vegetables, red meat, white meat, innards, seafood, dairy, tea, soft drinks, and fruit juice and breast cancer risk.

The hypothesis linking vegetable and fruit consumption to a reduced risk of breast cancer aligns with numerous previous studies [22–25]. The potential protective effect of these dietary components is biologically plausible due to their high fiber content and anti-carcinogenic compounds [26–28]. However, the heterogeneity in nutrient content among vegetables and fruits may contribute to variations in the observed associations. While some studies demonstrated inverse associations with both vegetables and fruits [22, 25], others found this association to be weaker for fruits alone or absent altogether [23, 24]. Interestingly, a recent study in Northern Vietnam found that a high intake of fruits, but not vegetables, was inversely associated with breast cancer risk [12]. In line with existing studies, our findings underscored the protective role of nearly all types of vegetables, except for red and orange varieties, while for fruits, the protective effect was only evident in the highest quartile of consumption. Carotenoids are theorized to lower cancer risk due to their antioxidant and anti-proliferative properties [29], which has been supported by some studies [25, 30]. However, our study found no significant link between red/orange vegetable consumption and breast cancer risk. This could be partly explained by the Vietnamese preference for dark vegetables over red/orange ones and the practice of deep cooking, which can alter carotenoid bioavailability compared to raw consumption.

Moreover, our study highlighted the protective role of soy foods, which is consistent with previous research in Asian populations [31–33] but not in Caucasian populations [34–36]. A recent meta-analysis suggested that consumption of only high levels of soybean is associated with a reduced risk of breast cancer in the Asian population [37]. Consequently, the low soy intake in Western countries compared to Asian countries may limit the ability to detect an inverse association between soy food and breast cancer risk [38]. Additionally, soy consumption during adolescence and adulthood has been linked to a notable reduction in breast cancer risk later in life [32]. Thus, the impact of soy foods on breast cancer risk may depend on genetics, prior soy intake, timing of exposure, and level of soy intake.

Interestingly, our research indicated a protective effect of coffee on breast cancer risk, a finding supported by emerging evidence [39, 40]. Conversely, conflicting results exist, such as a recent Vietnamese study that reported an increased risk among post-menopausal women with higher coffee intake [41]. Moreover, an extensive pooled analysis of 21 prospective studies showed that women who consumed at least two cups of coffee per day showed a lower risk of breast cancer than non-consumers [42]. Proposed mechanisms for the protective effects of coffee include its potential to inhibit inflammation and oxidative stress, thereby potentially preventing tumor formation [43]. This discrepancy emphasizes the need for further investigation, especially given the widespread global consumption of coffee.

Additionally, the inverse association with breast cancer risk was also found with eggs in this study, consistent with certain case-control studies in China [6, 44]. Conversely, a meta-analysis of prospective studies failed to detect a significant association between egg intake and breast cancer risk [45]. However, these analyses revealed that consuming a higher intake of eggs (five eggs/week) significantly increased the breast cancer risk. Similarly, another pooled analysis [46] suggested a J-shape association influenced by the level of egg intake, with the risk decreasing for consumption of under two eggs /week but increasing for consumption of over seven eggs /week compared to no egg consumption. Taken together, the discrepancy might be explained by the fact that the mean intake of eggs in our study was moderate, approximately three eggs/week, similar to the intake reported in Chinese studies.

Likewise, the relationship between fish consumption and breast cancer risk remains contentious, with studies in Asian populations suggesting a protective role [44, 47], whereas Western studies show null associations [48, 49] or even positive associations [50]. A recent study suggested that high consumption of fish is associated with lower breast cancer risk [51], and fish intake is higher in Asian populations compared to Western populations [52]. Consequently, there may be a reduced ability to detect the expected protective effect of fish intake on breast cancer risk in Western populations. Moreover, this protective effect might be attenuated or even reversed by other constituents in fish, such as organometallics and pesticides [51]. Considering the significant increase in pesticide consumption in Vietnam due to the intensification of the agricultural sector, which has also harmed fish populations [53], this may partially explain the lack of association between seafood consumption (among it, 90% was fish) and breast cancer risk in our study, despite being conducted in an Asian country. Conversely, the study in Northern Vietnam showed that freshwater fish, not saltwater fish, had an inverse association with breast cancer [12].

Furthermore, our findings did not support an association between breast cancer risk and dairy products, which is consistent with the results from a pooled analysis [46], but in contrast to some recent meta-analyses where the risk of breast cancer was inversely associated with total dairy food intake [54]. These findings also suggested that the protective effect of dairy products may depend on the dose, type of dairy, and timing of consumption [54]. The protective effect of dairy products can be attributed to the anti-carcinogenic properties of several compounds present in them, such as butyrate, lactoferrin, conjugated linoleic acid, calcium, and vitamin D. However, dairy products also contain various compounds, including saturated fatty acids, endogenous insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), and other contaminants such as pesticides, which are considered potentially carcinogenic. Taken together, these discrepancies may arise from differences in genetic factors, dietary patterns, and dose of dairy consumption among populations.

Similarly, despite previous hypotheses linking high-cholesterol diets like innards and red meat to increased breast cancer risk [22, 55], our data did not support these associations. Three large prospective cohort studies - the Swedish Mammography Cohort [56], the Black Women’s Health Study [57], and the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) cohort study [58] also reported the null association between meat intake and breast cancer risk. Additionally, a recent meta-analysis showed that the possible absolute effects of red and processed meat consumption on cancer incidence were very small, with low to very low certainty of evidence [59]. Differences in cooking methods and the degree of doneness may contribute to the disparity in findings. Certain cooking temperatures, durations, and styles can lead to the formation of carcinogenic mutagens, such as heterocyclic amines and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons [60, 61]. Furthermore, the association of meat with breast cancer risk may be immunohistochemical subtype-specific, with evidence of a higher risk of ER+/PR+ breast cancers but not ER−/PR− breast cancers [62].

Finally, our study found no significant association between soft drink consumption and breast cancer risk, contrary to findings from a meta-analysis of European and American populations, which indicated a statistically significant positive association between higher consumption of sugary drinks and breast cancer [63]. However, in the subgroup analysis, this meta-analysis showed non-statistically significant results for pre- and post-menopausal breast cancer. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that sugary beverage intake among Western populations is typically higher than among Asian populations [64], potentially limiting the ability to detect a positive association between soft drink consumption and breast cancer risk in Asian populations.

Although numerous epidemiological studies have explored the correlation between diet and breast cancer risk, there have been extremely limited data on this association in LMICs. Moreover, breast cancer risk varies considerably across ethnicities, with traditional Asian diets typically rich in plant-based foods, in contrast to the animal-based focus of Western diets. The evolving landscape of international trade, socioeconomic factors, and cultural exchanges further alters dietary habits and breast cancer risk profiles. Therefore, investigating the relationship between diet and breast cancer risk with a focus on LMICs is imperative for establishing effective prevention strategies. This pioneering study in Vietnam to investigate the association between detailed dietary factors - including 76 local food items - and breast cancer addresses a critical research gap within LMICs and significantly contributes to our understanding of dietary influences on breast cancer risk. The observed protective effects of certain dietary components, such as dark green vegetables and soybean products, were consistent with the recommendations of the third expert report from the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research (WCRF/AICR) 2018 [65], offering potential avenues for breast cancer prevention in LMIC settings. However, further investigation is warranted, particularly regarding the lack of association with red meat, white meat, innards, seafood, dairy products, soft drinks, and fruit juices, considering potential variations in processing, preparation, and consumption patterns within the Vietnamese context. The disparities between our findings and those of other studies underscore the importance of accounting for diverse populations and contextual factors when investigating dietary influences on breast cancer risk, especially in LMICs.

This study provides valuable insights into breast cancer risk factors specific to the Vietnamese population, serving as a representative model for LMICs. A major strength of the study lies in its robust study design, with a comprehensive examination of several group foods, rigorous selection of cases and controls, histological confirmation of breast cancer diagnoses, and thorough control of a wide range of confounding variables. Nonetheless, limitations exist, including the inability to establish causality due to the study's case-control design and potential bias introduced by self-reported lifestyle data, although minimized through strict selection criteria, reliability testing of questionnaires, and administration by trained interviewers. Residual confounding effects due to unmeasured factors could hinder the validity of our results despite the efforts of controlling for a set of covariates. Furthermore, the focus on individual food categories overlooks the complexity of dietary interactions, emphasizing the need for larger prospective studies examining holistic diets in relation to breast cancer risk among the Vietnamese population. Additionally, the absence of subgroup analyses based on different breast cancer molecular types is a notable limitation, as these subtypes may exhibit varying susceptibilities to dietary influences. Finally, the study was conducted among women residing in the southern provinces of Vietnam; therefore, the generalizability to other regions (for example, mountainous regions) in Vietnam could be limited.

Conclusions

Our study underscores the association between high intakes of vegetables, fruits, soybean products, eggs, and coffee with a significant decrease in breast cancer risk. These findings substantially contribute to our understanding of dietary factors and breast cancer risk in LMICs, laying the groundwork for culturally tailored and sustainable preventive strategies against breast cancer in these settings.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of the Department of Science and Technology of Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, and the Ho Chi Minh City Oncology Hospital.

Abbreviations

- LMICs

Low- and middle-income countries

- VOS

Vietnam Osteoporosis Study

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- FFQ

Food Frequency Questionnaire

Authors’ contributions

T.S.T., T.V.N., and L.T.H.P. conceived the research idea; T.M.D., H.D.N., A.H.T.P., and N.H.D.L. conducted the survey; H.D.N., Q.H.N.N., and L.T.H.P. provided databases for the research; T.M.D., Q.H.N.N., and T.S.T. performed statistical analysis; T.M.D., H.D.N., A.H.T.P., and N.H.D.L. drafted the manuscript; T.V.N. and L.T.H.P. had primary responsibility for the final content. All authors reviewed the paper and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by the Department of Science and Technology of Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, grant number 1218/QĐ-SKHCN.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to information that could compromise patient privacy but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the National Ethics Committee of the Vietnam Ministry of Health (Approval: 94/CN-HDDD issued on August 7th, 2020). All women who participated in this study provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Global Cancer Observatory—Vietnam Population fact sheets 2020. 2020. https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/populations/704-viet-nam-fact-sheets.pdf.

- 3.Pham DX, Ho TH, Bui TD, Ho-Pham LT, Nguyen TV. Trends in breast cancer incidence in Ho Chi Minh City 1996–2015: a registry-based study. PLoS One. 2021;16(2):e0246800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cuenca-Mico O, Aceves C. Micronutrients and breast cancer progression: a systematic review. Nutrients. 2020;12(12):3613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrari P, Rinaldi S, Jenab M, Lukanova A, Olsen A, Tjonneland A, et al. Dietary fiber intake and risk of hormonal receptor-defined breast cancer in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97(2):344–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bao PP, Shu XO, Zheng Y, Cai H, Ruan ZX, Gu K, et al. Fruit, vegetable, and animal food intake and breast cancer risk by hormone receptor status. Nutr Cancer. 2012;64(6):806–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim JH, Lee J, Jung SY, Kim J. Dietary factors and female breast cancer risk: a prospective cohort study. Nutrients. 2017;9(12):1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson JJ, Darwis NDM, Mackay DF, Celis-Morales CA, Lyall DM, Sattar N, et al. Red and processed meat consumption and breast cancer: UK Biobank cohort study and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2018;90:73–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagata C, Mizoue T, Tanaka K, Tsuji I, Tamakoshi A, Matsuo K, et al. Soy intake and breast cancer risk: an evaluation based on a systematic review of epidemiologic evidence among the Japanese population. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2014;44(3):282–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mourouti N, Kontogianni MD, Papavagelis C, Panagiotakos DB. Diet and breast cancer: a systematic review. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2015;66(1):1–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Romieu II, Amadou A, Chajes V. The role of diet, physical activity, body fatness, and breastfeeding in breast cancer in young women: epidemiological evidence. Rev Invest Clin. 2017;69(4):193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nguyen SM, Tran HTT, Nguyen LM, Bui OT, Hoang DV, Shrubsole MJ, et al. Association of fruit, vegetable, and animal food intakes with breast cancer risk overall and by molecular subtype among Vietnamese women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2022;31(5):1026–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fentie H, Ntenda PAM, Tiruneh FN. Dietary pattern and other factors of breast cancer among women: a case control study in Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Cancer. 2023;23(1):1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chajes V, Romieu I. Nutrition and breast cancer. Maturitas. 2014;77(1):7–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ho-Pham LT, Nguyen TV. The Vietnam osteoporosis study: rationale and design. Osteoporos Sarcopenia. 2017;3(2):90–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.General Statistics Office. Statistical summary book of Viet Nam 2020. Statistical Publishing House; 2021. p. 401–421.

- 17.General Statistics Office. The population and housing census 2019. Migration and urbanization: situation, trends and diffirences. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riley L, Guthold R, Cowan M, Savin S, Bhatti L, Armstrong T, Bonita R. The world health organization STEPwise approach to noncommunicable disease risk-factor surveillance: methods, challenges, and opportunities. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(1):74–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet Lond Engl. 2004;363:157–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kusama K, Le DS, Hanh TT, Takahashi K, Hung NT, Yoshiike N, et al. Reproducibility and validity of a food frequency questionnaire among Vietnamese in Ho Chi Minh City. J Am Coll Nutr. 2005;24(6):466–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rubin DB. Matched sampling for causal effects. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006. p. ix, 489. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kazemi A, Barati-Boldaji R, Soltani S, Mohammadipoor N, Esmaeilinezhad Z, Clark CCT, et al. Intake of various food groups and risk of breast cancer: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Adv Nutr. 2021;12(3):809–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aune D, Chan DS, Vieira AR, Rosenblatt DA, Vieira R, Greenwood DC, et al. Fruits, vegetables and breast cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;134(2):479–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Masala G, Assedi M, Bendinelli B, Ermini I, Sieri S, Grioni S, et al. Fruit and vegetables consumption and breast cancer risk: the EPIC Italy study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;132(3):1127–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farvid MS, Chen WY, Rosner BA, Tamimi RM, Willett WC, Eliassen AH. Fruit and vegetable consumption and breast cancer incidence: repeated measures over 30 years of follow-up. Int J Cancer. 2019;144(7):1496–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kapinova A, Kubatka P, Golubnitschaja O, Kello M, Zubor P, Solar P, et al. Dietary phytochemicals in breast cancer research: anticancer effects and potential utility for effective chemoprevention. Environ Health Prev Med. 2018;23(1):36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mokbel K, Mokbel K. Chemoprevention of breast cancer with vitamins and micronutrients: a concise review. In Vivo. 2019;33(4):983–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Talib WH, Daoud S, Mahmod AI, Hamed RA, Awajan D, Abuarab SF, et al. Plants as a source of anticancer agents: from bench to bedside. Molecules. 2022;27(15):4818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bertram JS. Dietary carotenoids, connexins and cancer: what is the connection? Biochem Soc Trans. 2004;32(Pt 6):985–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao LG, Zhang QL, Zheng JL, Li HL, Zhang W, Tang WG, et al. Dietary, circulating beta-carotene and risk of all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis from prospective studies. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen M, Rao Y, Zheng Y, Wei S, Li Y, Guo T, et al. Association between soy isoflavone intake and breast cancer risk for pre- and post-menopausal women: a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e89288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee SA, Shu XO, Li H, Yang G, Cai H, Wen W, et al. Adolescent and adult soy food intake and breast cancer risk: results from the Shanghai Women’s Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(6):1920–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wei Y, Lv J, Guo Y, Bian Z, Gao M, Du H, et al. Soy intake and breast cancer risk: a prospective study of 300,000 Chinese women and a dose-response meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020;35(6):567–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brasky TM, Lampe JW, Potter JD, Patterson RE, White E. Specialty supplements and breast cancer risk in the VITamins And Lifestyle (VITAL) cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(7):1696–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Touillaud M, Gelot A, Mesrine S, Bennetau-Pelissero C, Clavel-Chapelon F, Arveux P, et al. Use of dietary supplements containing soy isoflavones and breast cancer risk among women aged >50 y: a prospective study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;109(3):597–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Horn-Ross PL, Hoggatt KJ, West DW, Krone MR, Stewart SL, Anton H, et al. Recent diet and breast cancer risk: the California Teachers Study (USA). Cancer Causes Control. 2002;13(5):407–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao TT, Jin F, Li JG, Xu YY, Dong HT, Liu Q, et al. Dietary isoflavones or isoflavone-rich food intake and breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Clin Nutr. 2019;38(1):136–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mourouti N, Panagiotakos DB. Soy food consumption and breast cancer. Maturitas. 2013;76(2):118–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bhoo-Pathy N, Peeters PH, Uiterwaal CS, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Bulgiba AM, Bech BH, et al. Coffee and tea consumption and risk of pre- and postmenopausal breast cancer in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) cohort study. Breast Cancer Res. 2015;17(1):15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanchez-Quesada C, Romanos-Nanclares A, Navarro AM, Gea A, Cervantes S, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, et al. Coffee consumption and breast cancer risk in the SUN project. Eur J Nutr. 2020;59(8):3461–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trieu PD, Mello-Thoms C, Peat JK, Do TD, Brennan PC. Inconsistencies of breast cancer risk factors between the Northern and Southern regions of Vietnam. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2017;18(10):2747–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lafranconi A, Micek A, De Paoli P, Bimonte S, Rossi P, Quagliariello V, et al. Coffee intake decreases risk of postmenopausal breast cancer: a dose-response meta-analysis on prospective cohort studies. Nutrients. 2018;10(2):112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bohn SK, Blomhoff R, Paur I. Coffee and cancer risk, epidemiological evidence, and molecular mechanisms. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2014;58(5):915–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shannon J, Ray R, Wu C, Nelson Z, Gao DL, Li W, et al. Food and botanical groupings and risk of breast cancer: a case-control study in Shanghai, China. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(1):81–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Keum N, Lee DH, Marchand N, Oh H, Liu H, Aune D, et al. Egg intake and cancers of the breast, ovary and prostate: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Br J Nutr. 2015;114(7):1099–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Missmer SA, Smith-Warner SA, Spiegelman D, Yaun SS, Adami HO, Beeson WL, et al. Meat and dairy food consumption and breast cancer: a pooled analysis of cohort studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31(1):78–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim J, Lim SY, Shin A, Sung MK, Ro J, Kang HS, et al. Fatty fish and fish omega-3 fatty acid intakes decrease the breast cancer risk: a case-control study. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Folsom AR, Demissie Z. Fish intake, marine omega-3 fatty acids, and mortality in a cohort of postmenopausal women. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(10):1005–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Engeset D, Alsaker E, Lund E, Welch A, Khaw KT, Clavel-Chapelon F, et al. Fish consumption and breast cancer risk. The European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). Int J Cancer. 2006;119(1):175–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stripp C, Overvad K, Christensen J, Thomsen BL, Olsen A, Moller S, et al. Fish intake is positively associated with breast cancer incidence rate. J Nutr. 2003;133(11):3664–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zheng JS, Hu XJ, Zhao YM, Yang J, Li D. Intake of fish and marine n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and risk of breast cancer: meta-analysis of data from 21 independent prospective cohort studies. BMJ. 2013;346:f3706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Terry PD, Rohan TE, Wolk A. Intakes of fish and marine fatty acids and the risks of cancers of the breast and prostate and of other hormone-related cancers: a review of the epidemiologic evidence. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77(3):532–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Klemick H, Lichtenberg E. Pesticide use and fish harvests in vietnamese rice agroecosystems. Am J Agric Econ. 2008;90(1):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zang J, Shen M, Du S, Chen T, Zou S. The association between dairy intake and breast cancer in Western and Asian populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Breast Cancer. 2015;18(4):313–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Inoue-Choi M, Sinha R, Gierach GL, Ward MH. Red and processed meat, nitrite, and heme iron intakes and postmenopausal breast cancer risk in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. Int J Cancer. 2016;138(7):1609–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Larsson SC, Bergkvist L, Wolk A. Long-term meat intake and risk of breast cancer by oestrogen and progesterone receptor status in a cohort of Swedish women. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(17):3042–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Genkinger JM, Makambi KH, Palmer JR, Rosenberg L, Adams-Campbell LL. Consumption of dairy and meat in relation to breast cancer risk in the Black Women’s Health Study. Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24(4):675–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pala V, Krogh V, Berrino F, Sieri S, Grioni S, Tjonneland A, et al. Meat, eggs, dairy products, and risk of breast cancer in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) cohort. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90(3):602–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Han MA, Zeraatkar D, Guyatt GH, Vernooij RWM, El Dib R, Zhang Y, et al. Reduction of red and processed meat intake and cancer mortality and incidence: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(10):711–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Knize MG, Felton JS. Formation and human risk of carcinogenic heterocyclic amines formed from natural precursors in meat. Nutr Rev. 2005;63(5):158–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Felton JS, Knize MG, Wu RW, Colvin ME, Hatch FT, Malfatti MA. Mutagenic potency of food-derived heterocyclic amines. Mutat Res. 2007;616(1–2):90–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cho E, Chen WY, Hunter DJ, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Hankinson SE, et al. Red meat intake and risk of breast cancer among premenopausal women. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(20):2253–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Llaha F, Gil-Lespinard M, Unal P, de Villasante I, Castaneda J, Zamora-Ros R. Consumption of sweet beverages and cancer risk. A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutrients. 2021;13(2):516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lara-Castor L, Micha R, Cudhea F, Miller V, Shi P, Zhang J, et al. Sugar-sweetened beverage intakes among adults between 1990 and 2018 in 185 countries. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):5957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Clinton SK, Giovannucci EL, Hursting SD. The world cancer research fund/American institute for cancer research third expert report on diet, nutrition, physical activity, and cancer: impact and future directions. J Nutr. 2020;150(4):663–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to information that could compromise patient privacy but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.