Abstract

Tau is a microtubule-associated protein with an intrinsically unstructured conformation. Tau is subjected to several pathological post-translational modifications (PTMs), leading to its loss of interaction with microtubules and accumulation as neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) in neurons. Tau aggregates impede functions of endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria leading to the generation of oxidative stress and in turn amplifying the Tau aggregation. Tau is channelled to chaperones for folding into their native form, which otherwise causes its degradation and clearance. Cellular response triggers the activation of ubiquitin–proteasome system or autophagy to facilitate Tau degradation, based on the PTMs or mutations associated with Tau. Further, autophagy can be selective where Hsc70 interacts with Tau in monomeric, oligomeric and aggregated form and drives its clearance by chaperone-mediated autophagy pathway (CMA). Lysosome-associated membrane proteins-2A (LAMP-2A) is the key player of CMA that recognises Hsc70-Tau complex and triggers the downstream cascade. Thus, it becomes challenging for mutant Tau to be cleared by CMA as it loses its affinity for Hsc70 and LAMP-2A. In such a scenario, Tau might be degraded by macroautophagy otherwise sequestered by aggresomes. Henceforth, the degradation of Tau and its blockage that is associated with various PTMs of Tau would explain the dynamics of Tau degradation or accumulation in AD. Further, unveiling the role of accessory proteins involved in these degradation pathways would help in understanding their loss of function and preventing Tau clearance.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Tau, Neurofibrillary tangles, Tau degradation, Ubiquitin–proteasome system, Macroautophagy, Chaperone-mediated autophagy, Lysosome-associated membrane proteins-2A

Tau Degradation

Tau is an intrinsically disordered protein (IDP) that is involved in stabilising the axonal microtubules. Human Tau protein has six isoforms with two inserts and four repeats that are variably expressed in an age-specific manner. Tau isoforms are generated as a result of alternative splicing with three repeats Tau being expressed abundantly in the fetal CNS (Andreadis 2005). This is governed by exon 10 in the mRNA; mutations would cause aberrant splicing leading to the altered balance of three repeat and four repeat Tau which is one of the causes of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Ingram and Spillantini 2002; Lacovich et al. 2017). AD pathology is characterised by the accumulation of Tau as neurofibrillary tangles in somatodendritic compartments of neurons. Tau accumulation interrupts nuclear membrane, thereby hampering nuclear transport (Paonessa et al. 2019) and Tau oligomers increase membrane permeabilization by disrupting their integrity (Flach et al. 2012). Hyperphosphorylated Tau induces ER stress and activates unfolded protein response (Ho et al. 2012), whereas the overexpression of Tau in transgenic mice model impaired the Endoplasmic Reticulum-Associated Degradation (ERAD) pathway (Abisambra et al. 2013). The mitochondrial distribution in neurons plays a key role in fulfilling energy demands, and the distribution and localization of mitochondria are governed by microtubules network maintained by Tau protein (Course and Wang 2016; Cheng and Bai 2018; Pérez et al. 2018). Overexpression of Tau and its hyperphosphorylation were known to affect mitochondrial distribution in the cell (Shahpasand et al. 2012). Besides, the interaction of hyperphosphorylated Tau with Dynamin-like protein 1 (Drp1), a mitochondrial fission protein, increases mitochondrial fission and thus leads to mitochondrial degeneration (Manczak and Reddy 2012). On the other hand, the ER and mitochondria dysfunction is also known to induce Tau pathology. The ER stress increases the levels of Binding immunoglobulin protein (Bip) that induces the interaction of Tau with Glycogen synthase kinase-3 β (GSK-3β) (Liu et al. 2012). The oxidative stress caused due to the mitochondrial ROS increased phosphorylation of Tau by GSK-3β (Lovell et al. 2004). This suggests the interplay of ER and mitochondrial stress with Tau pathology which forms a chain reaction in amplifying Tau accumulation. Tauopathy also affects the protein degradation machinery which includes the ubiquitin–proteasome system by facilitating the interaction of PHF-Tau with the proteasome and its inhibition (Keck et al. 2003). In order to overcome the pathology associated with Tau accumulation, chaperones such as Hsp70 and Hsp90 impact Tau folding to its native form. In consequential conditions, these chaperones direct Tau degradation by autophagy, majorly by macroautophagy and chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA). This, in turn, is regulated by the diversity of mutations and post-translational modifications (PTMs) associated with Tau (Caballero et al. 2018). For instance, Hsp70 and Hsp90 along with their co-chaperone, CHIP ubiquitinate Tau; however, interaction with CHIP increases Tau aggregation. Since ubiquitinated Tau is accumulated with CHIP and other ubiquitinated proteins into NFTs, it is assumed that turnover of Tau is not enhanced by UPS (Petrucelli et al. 2004). Thus, ubiquitinated Tau are rather cleared by CMA (Ciechanover and Kwon 2015). This condition can be attenuated by inducing heat shock factor 1 (HSF1) and by increasing the levels of Hsp70 (Petrucelli et al. 2004). Macroautophagy is initiated by the ubiquitinated Tau that was accumulated as a result in the loss of ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS). Thus, ubiquitinated Tau interacts with p62 and relays towards the formation of phagophore and autophagosomes that later fuse with lysosome for protein degradation (Jing and Lim 2012). Macroautophagy was initially identified as bulk autophagy that engulfs cell organelles, pathogens, protein aggregates etc., whereas CMA is a selective autophagy process that involves the selective degradation of Tau protein. However, recent studies demonstrate that macroautophagy is a selective process involving several autophagy-related proteins (Atg). CMA primarily involves Hsc70 that delivers protein for selective degradation in the lysosomal compartment mediated by LAMP-2A. The levels of other accessory proteins such as p62, BAG and LC3 play a critical role in diverting Tau clearance through a specified pathway. The ubiquitin moieties in Tau tagged with ubiquitin interacts with p62, an adaptor protein, and channels Tau to either macroautophagy or UPS. This is resolved by the levels of BAG proteins where abundance of BAG1 would direct the client degradation by UPS and BAG3 degrades protein by autophagy (Gamerdinger et al. 2009; Stürner and Behl 2017). Studies in mature cortical neurons have showed that the Tau phosphorylated at Ser262 is directed to degradation by autophagy by BAG3 (Ji et al. 2019). A decline in macroautophagy is observed upon ageing and onset of AD that exhibits accumulation of p62 in autophagosomes, leading to the inhibition of both macroautophagy. This impedes proteasomal degradation as p62 plays key role in UPS by delivering the ubiquitinated Tau to proteasomes. Similarly, the ageing decreases CMA, as observed by the downregulation of Hsc70 and LAMP-2A (Loeffler et al. 2018).

Role of LAMP-2A in Tau Degradation

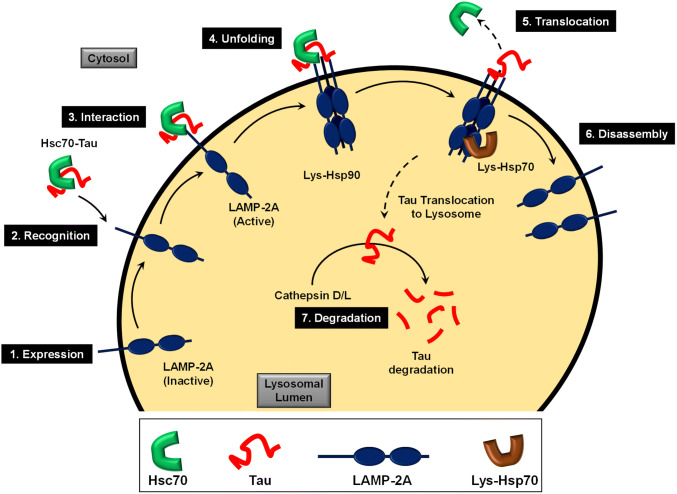

LAMP-2A is a glycoprotein, belongs to a single-pass type-1 membrane protein, found abundantly in the lysosomal membrane. LAMP-2A has two conserved N-glycosylated luminal domains towards N-terminal, a transmembrane domain and a C-terminal cytosolic domain. The lysosomal chaperones interact with the N-terminal domain and are known to maintain its stability during CMA. The transmembrane domain plays a key role in substrate binding where the information of substrate binding on the cytosolic side is transferred to the luminal side via the transmembrane domain. The C-terminal tails have an equal affinity for Hsc70 and Tau, which prevent Tau aggregation and cause its unfolding and translocation to lysosomal lumen. The C-terminal cytosolic tail is dynamic and interacts with the Hsc70-CMA substrate complex (Fig. 1). This triggers the activation of LAMP-2A by forming a homotrimer complex (Bandyopadhyay et al. 2008). LAMP-2A is present as inactive monomers on the lysosomal membrane and their number and activation increase during CMA. On the lysosomal luminal side, the homotrimer complex of LAMP-2A is stabilised by Hsp90. This complex interacts with lysosomal Hsc70 and further translocates Tau to lysosome where it is degraded by various proteases such as cathepsin D and cathepsin L (Khurana et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2009). Apart from participating in CMA, LAMP-2A is involved in lysosomal motility along microtubules, intracellular cholesterol transport and lysosomal biogenesis and that plays an important role in autophagy (Eskelinen et al. 2004; Huynh et al. 2007). Hence studying CMA and its modulation in Alzheimer’s disease would add an insight to understand the degradation of aberrant Tau.

Fig. 1.

Cascade of events in Tau degradation by CMA. LAMP-2A is expressed as inactive monomer on lysosomal membrane (1). Hsc70-Tau complex interacts with the C-terminal cytosolic tail of LAMP-2A (2) and leads to its activation (3). Thus, activated LAMP-2A trimerizes to form a translocon for transporting the cytosolic protein to be degraded into lysosome (4). The interaction of Lys-Hs90 with the LAMP-2A trimer governs its stability. The Tau is then translocated inside the lysosome by Lys-Hsc70 by a ratchet pulling mechanism (5); subsequently, the cytosolic Hsc70 is released and the LAMP-2A complex is disassembled (6). Thus, translocated Tau is degraded by lysosomal proteases (7)

CMA is a selective autophagy process where the cytosolic Hsc70 interacts with the client protein with a pentapeptide motif “KFERQ”, also known as CMA-targeting motifs (Terlecky et al. 1992; Dice 1990). Tau has two such motifs residing in three repeat towards the C-terminal region: 336QVEVK340 and 347KDRVQ351 (Wang et al. 2009). CMA is critically regulated by two steps, binding and translocation, which is variably affected by various Tau modifications that include phosphorylation, glycosylation and acetylation etc. The pentapeptide recognition motif KFERQ is composed of positive, negative, hydrophobic and a neutral amino acid with a net positive charge. Modifications such as phosphorylation and acetylation alter the charge of Tau that would lead to the loss of affinity for Hsc70, causing impaired CMA. Age and pathogenic mutations of Tau are the major factors for the downregulation of CMA; however, Tau mutants have distinct effects on CMA (Cuervo and Wong 2014). For example, the P301L mutant reduces the Tau degradation by CMA and the mutant A152T reduced the rate of Tau degradation by CMA (Caballero et al. 2018). Although cells respond to degrade these mutants by upregulating CMA, over the time, CMA dose not sustain the accumulation of Tau mutants.

Role of Chaperones in the Activation of LAMP-2A

The lysosomal and cytosolic chaperones along with LAMP-2A orchestrate the CMA. These chaperones regulate the activation, stability and disassembly of multimeric LAMP-2A. Hsc70 acts both in cytosolic and lysosomal lumen where, in the cytosol, it delivers the client protein to the LAMP-2A; the luminal Hsc70 associates with LAMP-2A and pulls the Tau protein into the lysosomal lumen (Chiang et al. 1989; Agarraberes and Dice 2001). Although Hsp90 unfolds the client protein in the cytosolic side, its main function is to stabilise the multimeric LAMP-2A during protein translocation (Bandyopadhyay et al. 2008; Agarraberes and Dice 2001; Gong et al. 2018). Cellular conditions such as protein aggregation, starvation and oxidative stress increase lysosomal chaperones (Kaushik et al. 2008). This increase in lysosomal chaperone is mediated by the fusion of late endosomes with lysosomes, since blocking CMA or macroautophagy did not affect the chaperone levels (Massey et al. 2006). This suggests that chaperones are transported into lysosomes by endosomal fusion, but not by CMA or macroautophagy.

CMA and Macroautophagy in Tau Degradation

Macroautophagy is a bulk endocytosis process where the cellular contents are carried to the lysosome via formation of phagophore and endosome; on the other hand, CMA is a selective autophagy process (Yang and Klionsky 2010; Wang and Mao 2014; Koga and Cuervo 2011). Beclin 1, LC3B and p62 are the key players of macroautophagy that are involved in initial phagophore formation, phagophore extension and interaction with the ubiquitinated cargo proteins, respectively (Harris and Rubinsztein 2012). Apart from these, several other ubiquitin-like proteins and ubiquitinating enzymes are involved in macroautophagy. Atg12 is an ubiquitin-like molecule linked to Atg5 by Atg7, ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1), and Atg10, ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2) (Johansen and Lamark 2011). Atg7 is also involved in conjugating LC3 to phosphotidylethanolamine, thus forming activated LC3-II that interacts with LC3-interacting regions in other proteins that are involved in phagophore extension and formation of autophagosomes (Bento et al. 2016). Studies in Atg7 knockout mice resulted in the accumulation of Tau, ubiquitin and p62 in inclusions, thus suggesting its importance in initiating autophagy (Inoue et al. 2012). Moreover, the upregulation of BAG3 would clear Tau aggregates by following macroautophagy (Stürner and Behl 2017). Hsc70 associates with its co-chaperone CHIP and ubiquitinates Tau, whereas other co-chaperones of Hsc70 i.e. Hsp40, BAG1, Hip and Hop interacts with the client protein for its degradation by CMA (Agarraberes and Dice 2001). These indicate the role of different groups of protein in fine-tuning the Tau degradation pathways. Hsc70 could also divert ubiquinated Tau degradation by macroautophagy instead of proteasomal degradation or CMA depending on the levels of essential proteins such as p62, BAG3 or BAG1 etc., (Fernández‐Fernández et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2015). The cell adopts macroautophagy or CMA based on the stress condition, for example, in order to rescue the cell, initially, macroautophagy is triggered which is switched to CMA during prolonged stress (Cuervo et al. 1995). This results from the cross-talk of macroautophagy and CMA, a well-proven phenomenon where cell switches from macroautophagy to CMA during impaired macroautophagy (Kaushik et al. 2008). The soluble and aggregates form of mutant Tau are cleared by macroautophagy, whereas the mutant form of Tau prevents degradation by CMA. This is due to the loss of interaction of mutant Tau with Hsc70 or LAMP-2A (Cuervo and Wong 2014). Further, elucidating the role of post-translational modifications and various mutations associated with Tau would help in understanding the adaptability of macroautophagy or CMA during stress conditions.

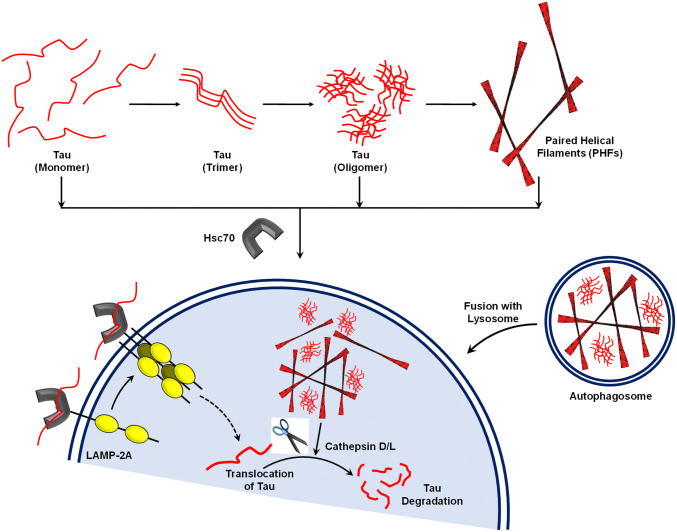

LAMP-2A and LC3B in Governing CMA

In normal conditions, CMA and macroautophagy occur at basal levels. During proteotoxicity, CMA and macroautophagy are functionally co-ordinated to remove altered protein accumulations (Li et al. 2011). However, the molecular switch involved in the transition between CMA and macroautophagy is yet to be studied (Wu et al. 2015). Studies were conducted where by blocking either of the pathways the flux of substrates for degradation was attempted to understand (Massey et al. 2008). In this scenario, identifying the modifications of Tau protein associated with their affinity for LAMP-2A and LC3B would be of great scope. The varied PTMs of Tau protein directs its solubility, aggregation and degradation. For example, the sumoylation of Tau prevents its hyperphosphorylation and aggregation (Luo et al. 2014; Caballero et al. 2018). Other PTMs such as glycation, acetylation, glycosylation, truncation and ubiquitination, etc. renders Tau aggregation (Cohen et al. 2011; Avila et al. 2004). Although Tau is subjected to such discrete modifications, the cellular system channelling Tau degradation via macroautophagy or CMA is highly intrigued. The aberrant Tau protein dissociates from microtubules during AD and self-assembles to form initial nucleating species followed by the toxic oligomers and paired helical filaments that act as a sink for pathological Tau monomers (Wang and Mandelkow 2016; Gao et al. 2018). Studies have shown that CMA can prevent proteotoxicity caused by Tau accumulation (Caballero et al. 2018). Apart from LAMP-2A, Hsc70 is the key player of CMA in the cytosol. Hsc70 is known to interact with Tau and direct its degradation during normal conditions (Taylor et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2009). The AD triggers progressive Tau accumulation into toxic oligomer that later forms NFTs (Fig. 2). Recent studies suggest that Hsc70 can interact with both Tau oligomers as well as PHFs (Baughman et al. 2018; Ferrari et al. 2018). Hence it could be speculated that Hsc70 might prevent toxicity resulting from the accumulation of Tau monomers into PHFs.

Fig. 2.

Different forms of Tau cleared by CMA viz. Hsc70. Tau protein assembles into PHFs by forming initial nucleus, followed by oligomers. Although PHFs sequester the Tau monomers to aggregates, oligomers are the toxic intermediates. Hsc70 is the constitutively expressed chaperone, which interacts with the Tau present as monomer, oligomer and PHFs. This facilitates the interaction of Hsc70-Tau complex with LAMP-2A, followed by degradation of Tau by CMA. On the other hand, the Tau accumulated in the neuron might be engulfed to form autophagosomes, which would fuse with lysosome and deliver Tau for lysosomal degradation

Conclusion

The aggregation of Tau protein as NFTs is one of the complex and characteristic phenomenon that marks the AD pathology. The accumulated Tau disrupts functions of ER, mitochondria, nuclear and cell membrane integrity etc., thus predisposing neurons to degenerate. Such aggregated Tau is been channelled by chaperones for native folding or degradation. This process becomes challenging during AD progression that is associated with the Tau PTMs and mutations. The association of Hsp70 or Hsc70 with CHIP ubiquitinates Tau for proteasomal degradation. Since, ubiquitinated Tau is a poor substrate for degradation by proteasome, it is directed to macroautophagy. At this point, other PTMs such as phosphorylation would modulate the interaction of Tau with other key proteins such as BAG1, BAG3, LC3B, and p62 etc. This would in turn fine tune Tau degradation to specific pathways. On the other hand, Tau mutants fail to conjugate with these proteins and thereby try to adopt a pathway for their clearance mechanism. For example, the loss of interaction of mutant Tau with Hsc70 and LAMP-2A will prevent CMA, where macroautophagy comes into role. These suggest the need for more insights to understand the molecular switch involved in sensing the cellular burden of Tau accumulation that chooses CMA over macroautophagy or vice versa.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- Atg

Autophagy-related proteins

- BAG

BCL2-associated athanogene

- Bip

Binding immunoglobulin protein

- CHIP

Carboxyl terminus of the Hsc70-interacting protein

- CMA

Chaperone-mediated autophagy

- Drp1

Dynamin-like protein 1

- ER

Endoplasmic reticulum

- ERAD

Endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation

- GSK-3β

Glycogen synthase kinase-3 β

- IDP

Intrinsically disordered protein

- HSF1

Heat shock factor 1

- LAMP-2A

Lysosome-associated membrane proteins-2A

- LC3B

Microtubule-associated proteins 1A/1B light chain 3B

- NFTs

Neurofibrillary tangles

- PTMs

Post-translational modifications

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- UPS

Ubiquitin–proteasome system

Author Contributions

NV and SC prepared the initial draft of the paper. SC conceived the idea of the work, supervised, provided resources and wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final paper.

Funding

This project is supported in part by grant from in-house CSIR-National Chemical Laboratory Grant MLP029526.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Research Involving Human Participants and /or Animals

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abisambra JF, Jinwal UK, Blair LJ, O'Leary JC, Li Q, Brady S, Wang L, Guidi CE, Zhang B, Nordhues BA (2013) Tau accumulation activates the unfolded protein response by impairing endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. J Neurosci 33(22):9498–9507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarraberes FA, Dice JF (2001) A molecular chaperone complex at the lysosomal membrane is required for protein translocation. J Cell Sci 114(13):2491–2499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreadis A (2005) Tau gene alternative splicing: expression patterns, regulation and modulation of function in normal brain and neurodegenerative diseases. Biochim Et Biophys Acta (BBA) Mol Basis Dis 173(2):91–103 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Avila J, Lucas JJ, Perez M, Hernandez F (2004) Role of tau protein in both physiological and pathological conditions. Physiol Rev 84(2):361–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay U, Kaushik S, Varticovski L, Cuervo AM (2008) The chaperone-mediated autophagy receptor organizes in dynamic protein complexes at the lysosomal membrane. Mol Cell Biol 28(18):5747–5763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baughman HE, Clouser AF, Klevit RE, Nath A (2018) HspB1 and Hsc70 chaperones engage distinct tau species and have different inhibitory effects on amyloid formation. J Biol Chem 293(8):2687–2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bento CF, Renna M, Ghislat G, Puri C, Ashkenazi A, Vicinanza M, Menzies FM, Rubinsztein DC (2016) Mammalian autophagy: how does it work? Annu Rev Biochem 85:685–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caballero B, Wang Y, Diaz A, Tasset I, Juste YR, Stiller B, Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E, Cuervo AM (2018) Interplay of pathogenic forms of human tau with different autophagic pathways. Aging Cell 17(1):e12692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Bai F (2018) The association of tau with mitochondrial dysfunction in alzheimer's disease. Front Neurosci 12:163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang H-L, Plant C, Dice J (1989) A role for a 70-kilodalton heat shock protein in lysosomal degradation of intracellular proteins. Science 246(4928):382–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciechanover A, Kwon YT (2015) Degradation of misfolded proteins in neurodegenerative diseases: therapeutic targets and strategies. Exp Mol Med 47(3):e147–e147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen TJ, Guo JL, Hurtado DE, Kwong LK, Mills IP, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM (2011) The acetylation of tau inhibits its function and promotes pathological tau aggregation. Nat Commun 2(1):1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Course MM, Wang X (2016) Transporting mitochondria in neurons. F1000Research. 10.12688/f1000research.7864.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuervo AM, Wong E (2014) Chaperone-mediated autophagy: roles in disease and aging. Cell Res 24(1):92–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuervo AM, Knecht E, Terlecky SR, Dice JF (1995) Activation of a selective pathway of lysosomal proteolysis in rat liver by prolonged starvation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 269(5):C1200–C1208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dice JF (1990) Peptide sequences that target cytosolic proteins for lysosomal proteolysis. Trends Biochem Sci 15(8):305–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskelinen E-L, Schmidt CK, Neu S, Willenborg M, Fuertes G, Salvador N, Tanaka Y, Lullmann-Rauch R, Hartmann D, Heeren J (2004) Disturbed cholesterol traffic but normal proteolytic function in LAMP-1/LAMP-2 double-deficient fibroblasts. Mol Biol Cell 15(7):3132–3145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Fernández MR, Gragera M, Ochoa-Ibarrola L, Quintana-Gallardo L, Valpuesta JM (2017) Hsp70–a master regulator in protein degradation. FEBS Lett 591(17):2648–2660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari L, Geerts WJ, van Wezel M, Kos R, Konstantoulea A, van Bezouwen LS, Forster FG, Rudiger SG (2018) Human chaperones untangle fibrils of the Alzheimer protein Tau. Biorxiv. 10.1101/426650 [Google Scholar]

- Flach K, Hilbrich I, Schiffmann A, Gärtner U, Krüger M, Leonhardt M, Waschipky H, Wick L, Arendt T, Holzer M (2012) Tau oligomers impair artificial membrane integrity and cellular viability. J Biol Chem 287(52):43223–43233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamerdinger M, Hajieva P, Kaya AM, Wolfrum U, Hartl FU, Behl C (2009) Protein quality control during aging involves recruitment of the macroautophagy pathway by BAG3. EMBO J 28(7):889–901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Tan L, Yu J-T, Tan L (2018) Tau in Alzheimer's disease: mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Curr Alzheimer Res 15(3):283–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Z, Tasset I, Diaz A, Anguiano J, Tas E, Cui L, Kuliawat R, Liu H, Kühn B, Cuervo AM (2018) Humanin is an endogenous activator of chaperone-mediated autophagy. J Cell Biol 217(2):635–647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris H, Rubinsztein DC (2012) Control of autophagy as a therapy for neurodegenerative disease. Nat Rev Neurol 8(2):108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho Y-S, Yang X, Lau JC-F, Hung CH-L, Wuwongse S, Zhang Q, Wang J, Baum L, So K-F, Chang RC-C (2012) Endoplasmic reticulum stress induces tau pathology and forms a vicious cycle: implication in Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis. J Alzheimer's Dis 28(4):839–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh KK, Eskelinen EL, Scott CC, Malevanets A, Saftig P, Grinstein S (2007) LAMP proteins are required for fusion of lysosomes with phagosomes. EMBO J 26(2):313–324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram EM, Spillantini MG (2002) Tau gene mutations: dissecting the pathogenesis of FTDP-17. Trends Mol Med 8(12):555–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue K, Rispoli J, Kaphzan H, Klann E, Chen EI, Kim J, Komatsu M, Abeliovich A (2012) Macroautophagy deficiency mediates age-dependent neurodegeneration through a phospho-tau pathway. Mol Neurodegener 7(1):48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji C, Tang M, Zeidler C, Höhfeld J, Johnson GV (2019) BAG3 and SYNPO (synaptopodin) facilitate phospho-MAPT/Tau degradation via autophagy in neuronal processes. Autophagy 15(7):1199–1213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing K, Lim K (2012) Why is autophagy important in human diseases? Exp Mol Med 44(2):69–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen T, Lamark T (2011) Selective autophagy mediated by autophagic adapter proteins. Autophagy 7(3):279–296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushik S, Massey AC, Mizushima N, Cuervo AM (2008) Constitutive activation of chaperone-mediated autophagy in cells with impaired macroautophagy. Mol Biol Cell 19(5):2179–2192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keck S, Nitsch R, Grune T, Ullrich O (2003) Proteasome inhibition by paired helical filament-tau in brains of patients with Alzheimer's disease. J Neurochem 85(1):115–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khurana V, Elson-Schwab I, Fulga TA, Sharp KA, Loewen CA, Mulkearns E, Tyynelä J, Scherzer CR, Feany MB (2010) Lysosomal dysfunction promotes cleavage and neurotoxicity of tau in vivo. PLoS Genet 6(7):e1001026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga H, Cuervo AM (2011) Chaperone-mediated autophagy dysfunction in the pathogenesis of neurodegeneration. Neurobiol Dis 43(1):29–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacovich V, Espindola SL, Alloatti M, Devoto VP, Cromberg LE, Čarná ME, Forte G, Gallo J-M, Bruno L, Stokin GB (2017) Tau isoforms imbalance impairs the axonal transport of the amyloid precursor protein in human neurons. J Neurosci 37(1):58–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Yang Q, Mao Z (2011) Chaperone-mediated autophagy: machinery, regulation and biological consequences. Cell Mol Life Sci 68(5):749–763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z-C, Fu Z-Q, Song J, Zhang J-Y, Wei Y-P, Chu J, Han L, Qu N, Wang J-Z, Tian Q (2012) Bip enhanced the association of GSK-3β with tau during ER stress both in vivo and in vitro. J Alzheimer's Dis 29(4):727–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeffler DA, Klaver AC, Coffey MP, Aasly JO (2018) Cerebrospinal fluid concentration of key autophagy protein Lamp2 changes little during Normal aging. Front Aging Neurosci 10:130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell MA, Xiong S, Xie C, Davies P, Markesbery WR (2004) Induction of hyperphosphorylated tau in primary rat cortical neuron cultures mediated by oxidative stress and glycogen synthase kinase-3. J Alzheimer's Dis 6(6):659–671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo H-B, Xia Y-Y, Shu X-J, Liu Z-C, Feng Y, Liu X-H, Yu G, Yin G, Xiong Y-S, Zeng K (2014) SUMOylation at K340 inhibits tau degradation through deregulating its phosphorylation and ubiquitination. Proc Natl Acad Sci 111(46):16586–16591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manczak M, Reddy PH (2012) Abnormal interaction between the mitochondrial fission protein Drp1 and hyperphosphorylated tau in Alzheimer's disease neurons: implications for mitochondrial dysfunction and neuronal damage. Hum Mol Genet 21(11):2538–2547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey AC, Kaushik S, Sovak G, Kiffin R, Cuervo AM (2006) Consequences of the selective blockage of chaperone-mediated autophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci 103(15):5805–5810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey AC, Follenzi A, Kiffin R, Zhang C, Cuervo AM (2008) Early cellular changes after blockage of chaperone-mediated autophagy. Autophagy 4(4):442–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paonessa F, Evans LD, Solanki R, Larrieu D, Wray S, Hardy J, Jackson SP, Livesey FJ (2019) Microtubules deform the nuclear membrane and disrupt nucleocytoplasmic transport in tau-mediated frontotemporal dementia. Cell Rep 26(3):582–593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez MJ, Jara C, Quintanilla RA (2018) Contribution of tau pathology to mitochondrial impairment in neurodegeneration. Front Neurosci 12:441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrucelli L, Dickson D, Kehoe K, Taylor J, Snyder H, Grover A, De Lucia M, McGowan E, Lewis J, Prihar G (2004) CHIP and Hsp70 regulate tau ubiquitination, degradation and aggregation. Hum Mol Genet 13(7):703–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahpasand K, Uemura I, Saito T, Asano T, Hata K, Shibata K, Toyoshima Y, Hasegawa M, Hisanaga S-i (2012) Regulation of mitochondrial transport and inter-microtubule spacing by tau phosphorylation at the sites hyperphosphorylated in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci 32(7):2430–2441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stürner E, Behl C (2017) The role of the multifunctional BAG3 protein in cellular protein quality control and in disease. Front Mol Neurosci 10:177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor IR, Ahmad A, Wu T, Nordhues BA, Bhullar A, Gestwicki JE, Zuiderweg ER (2018) The disorderly conduct of Hsc70 and its interaction with the Alzheimer's-related Tau protein. J Biol Chem 293(27):10796–10809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terlecky SR, Chiang H, Olson TS, Dice JF (1992) Protein and peptide binding and stimulation of in vitro lysosomal proteolysis by the 73-kDa heat shock cognate protein. J Biol Chem 267(13):9202–9209 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Mao Z (2014) Chaperone-mediated autophagy: roles in neurodegeneration. Transl Neurodegeners 3(1):20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Mandelkow E (2016) Tau in physiology and pathology. Nat Rev Neurosci 17(1):22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D-W, Peng Z-J, Ren G-F, Wang G-X (2015) The different roles of selective autophagic protein degradation in mammalian cells. Oncotarget 6(35):37098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Martinez-Vicente M, Krüger U, Kaushik S, Wong E, Mandelkow E-M, Cuervo AM, Mandelkow E (2009) Tau fragmentation, aggregation and clearance: the dual role of lysosomal processing. Hum Mol Genet 18(21):4153–4170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Chen S, Ammar A-B, Xu J, Wu Q, Pan K, Zhang J, Hong Y (2015) Crosstalk between macroautophagy and chaperone-mediated autophagy: implications for the treatment of neurological diseases. Mol Neurobiol 52(3):1284–1296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Klionsky DJ (2010) Eaten alive: a history of macroautophagy. Nat Cell Biol 12(9):814–822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]