Abstract

Macrophages are thought to represent one of the first cell types in the body to be infected during the early stage of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) transmission and represent a potential viral reservoir in vivo. Thus, an understanding of HIV-1 attachment to these cells is fundamental to the development of novel anti-HIV-1 therapies. Although one of the major targets of HIV-1 in vivo—CD4+ T lymphocytes—express high CD4 levels, other major targets such as macrophages do not. We asked in this study whether this low CD4 level on macrophages is sufficient to support HIV-1 attachment to these cells or whether cell surface proteins other than CD4 are required for this process. We show that CD4 alone is not sufficient to support the initial adsorption of HIV-1 to macrophages. Importantly, we find that heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) serve as the main class of attachment receptors for HIV-1 on macrophages. Most importantly, we demonstrate that a single family of HSPGs, the syndecans, efficiently mediates HIV-1 attachment and represents an abundant class of attachment receptors on macrophages.

To date, the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) receptor complex known to be essential for virus entry consists of CD4 molecules expressed on T cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, and microglia and a member of the seven-transmembrane chemokine receptor family. It is thought that HIV-1 initiates its attachment to host cells via an interaction between the virus-encoded surface gp120 glycoprotein and cell surface CD4 molecules. Binding of gp120 to CD4 induces conformational changes in gp120 that result in the exposure of a chemokine receptor binding site on gp120. The subsequent interaction between gp120 and a chemokine receptor triggers the fusion of virus and cell membranes, allowing the delivery of the viral genome into the cytosol of the host cell. Based on this model, gp120 is responsible both for the initial attachment of the virus to target cells and the subsequent fusion with the host cell.

For the last decade, CD4 has been thought to be the exclusive attachment receptor for HIV-1. Indeed, several observations support the notion that gp120-CD4 interactions are sufficient to mediate the initial attachment of HIV-1 to target cells (13). Specifically, it has been found that HIV-1 attaches to CD4-positive T cells but fails to attach to parental CD4-negative T-cell lines (33). Furthermore, anti-CD4 antibodies directed against the gp120 binding site of CD4 prevent HIV-1 attachment to CD4+ T cell lines (33). Finally, the apparent affinity between recombinant monomeric gp120 and soluble CD4 was found to be high, on the order of 1 to 10 nM (19). Altogether, these data led researchers to postulate that CD4 is the exclusive attachment receptor for HIV-1.

However, recent data have emerged suggesting that interactions other than gp120-CD4 interactions are required for HIV-1 attachment to specific target cells. First, it has been found that the affinity of oligomeric gp120 for CD4 is much lower than the affinity for monomeric gp120 for CD4 (10, 20, 29). Specifically, oligomerization of patient virus gp120 into a trimer of gp120-gp41 heterodimers drastically reduces its affinity for CD4 by 3 logs (10). This apparent low affinity of oligomeric gp120 for CD4 suggested to us that the gp120-CD4 interaction alone would be not sufficient for tight attachment to cells which express little CD4, such as macrophages, microglia, and dendritic cells (9, 31). On such cell types, the attachment of patient virus with low intrinsinc affinity for CD4 suggests the requirement for supplementary interactions, via receptors others than CD4. Corroborating this hypothesis, Mondor et al. showed that HIV-1 attaches to CD4-negative adherent HeLa cells as well as CD4-positive HeLa cells (18). Furthermore, they found that anti-CD4 antibodies, which were previously shown to block HIV-1 attachment to suspension T cells, did not prevent HIV-1 attachment to CD4-positive HeLa cells (18). These data suggest that the dependence of HIV-1 attachment to target cells on the gp120-CD4 interaction is highly cell type specific and may be replaced by other virus-receptor interactions.

Several lines of evidence suggest that cell surface heparan sulfate (HS) proteoglycans (HSPGs) act as necessary HIV-1 attachment receptors on specific target cells. Specifically, it has been shown that soluble polyanions such as dextran sulfate, heparin, or heparan sulfate inhibit HIV-1 infection (18, 4, 24, 27). The fact that polyanionic compounds bind to basic residues suggests that HSPGs participate in the initial HIV-1 attachment to target cells. Given that these compounds possess the capacity to bind to basic residues located in the V3 loop of gp120 (27), which is also responsible for fusion, the use of soluble polyanionic compounds does not permit the distinction between inhibition of attachment and/or fusion. However, more direct evidence suggests that HSPGs participate exclusively in HIV-1 attachment to target cells. Specifically, the removal of cell surface polyanionic chains of proteoglycans using heparitinase totally abrogates both HIV-1 attachment to and infectivity of CD4-positive HeLa cells (18). Given that heparitinase does not affect cell surface CD4, these findings suggest that HSPGs may act as alternative attachment receptors for HIV-1 on specific target cells such as HeLa cells.

Using a methodology which allows us to quantitatively distinguish the initial attachment from subsequent fusion, we analyzed HIV-1 attachment to primary cells. Specifically, we investigated the respective uses of the two candidate attachment receptors, CD4 and HSPGs, in HIV-1 attachment to CD4+ T lymphocytes and macrophages.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

CD4-positive HeLa cells were a generous gift from P. Charneau and F. Clavel, whereas A3.01 cells were obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Program. Peripheral blood monocytic cells from healthy donors were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque gradient centrifugation. Fresh monocytes were obtained by plastic adherence for 1 h in RPMI containing 10% autologous human serum, whereas monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM) were obtained by plastic adherence for 10 days. Adherent monocytes and MDM (95 to 99% CD14+ cells) as well as CD4-positive HeLa cells were detached by phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-EDTA treatment prior to fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis. Phytohemagglutinin (PHA)–interleukin 2 (IL-2)-stimulated CD4+ T lymphocytes were purified by an immunobead depletion strategy as described previously (21). Parental K562, syndecan-1-transfected K562, and glypican-1-transfected K562 cells were obtained as described previously (32). The pBABE-CXCR4-puromycin plasmid (obtained from the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program) was used to transfer CXCR4. Transfectants were selected in medium containing puromycin. Puromycin-resistant cells were sorted by FACS using an anti-CXCR4 monoclonal antibody. To introduce CD4, cells were then transfected with the vector pMX-CD4 (a generous gift from N. Landau), which contains human CD4 but no selectable marker. CD4-positive cells were sorted by FACS using an anti-CD4 antibody and plated at limiting dilution for selection. Populations were selected for low or high CD4 expression by FACS analysis. CD4 and CXCR4 expression was carefully examined at the time of attachment or infection assays by FACS analysis.

FACS analyses.

One million cells were incubated with antibodies (1 μg) in 500 μl of PBS containing 0.25% human serum. Anti HS (10E4 from Seikagaku), anti-CD4 (RPA-T4), anti-CD14 (M5E2), and anti-CXCR4 (12G5) antibodies were obtained from Pharmingen. Anti-betaglycan polyclonal antibodies were obtained from Upstate Biotechnology, and antibodies directed against syndecan−1, −2, −3, and −4 and glypican-1 were provided by G. David (32). Cell surface removal of HS by using heparitinase (heparatinases I and III [30 and 6 mIU/ml], obtained from Seikagaku) was performed as described previously (28), whereas glycosylphosphatidyl inositol (GPI)-linked protein removal by phospholipase C (Sigma) was performed as described previously (16). Note that the 10E4 immunoglobulin M monoclonal anti-HS antibody was generated by immunization against liposome-incorporated membrane HSPGs from human fetal lung fibroblasts. The antibody reacts with an epitope present in many types of HS. The epitope includes N-sulfated glucosamine residues that are critical for the reactivity of the antibody. The reactivity of the antibody with most cell surface HS is abolished after treatment of the HSPG with heparitinase.

Infections.

All viruses used in this study were transiently expressed by calcium phosphate transfection with 40 μg of each proviral DNA construct as described previously (28). Laboratory-adapted provirus R9 (NL4.3 derivative, X4 gp120) (11) and R9BaL (R9 pseudotyped with R5 gp120) (35) were provided by D. Trono, whereas R9Δgp120 was provided by C. Aiken. The patient provirus JR-CSF was a generous gift from M. Moulard. It is important to emphasize that only viruses derived from the same transfection were compared for attachment and infectivity assays as described previously (28). Viral supernatants, harvested 72 h posttransfection, were filtered through a 0.2-μm-pore-size filter to remove cellular debris. The filtrate was concentrated with a 100-kDa-cutoff Centricon concentrator (Amicon) to eliminate free viral proteins such as CA as well as free cellular proteins such as soluble proteoglycans that would interfere in our assays. Virus was further purified on a 20 to 70% sucrose gradient. Viral load was standardized by p24 antigen by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (NEN-Dupont). Target cells (2 × 106 cells) were exposed to 2 ng of p24 for 2 h and washed to remove unbound virus. Viral replication was monitored by measuring capsid release in the supernatant by p24 ELISA every three days. Note that patient JR-CSF virus originally produced from 293T cells was further amplified in PHA–IL-2-stimulated peripheral blood monolytic cells and purified and used as above.

Attachment assay.

Our classical attachment assay was performed as described previously (28). Target cells (3 × 106 cells in a six-well plate) were incubated for 1 h at 4°C before viral exposure. Purified viruses from 293T cells (R9, R9BaL, or R9Δgp120) or from PHA–IL-2-stimulated PBMCs (JR-CSF) (10 ng of p24) were added to target cells for 30 min at 4°C in a final volume of 2 ml of cold complete Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium. Cells were washed five times with 5 ml of cold PBS to remove unbound material and lysed in PBS containing 0.5% NP-40. Under these conditions no internalization occurs, since no cytosolic p24 can be detected upon protease treatment of the target cells. Attachment assay was monitored by measuring the amount of p24 in the supernatant of cell lysates by ELISA. To determine the role of HS and CD4 in HIV-1 attachment, target cells were incubated for 2 h at 37°C with heparitinase (10 U/ml) or with anti-CD4 antibodies (10 μg/ml) as described previously (28).

RESULTS

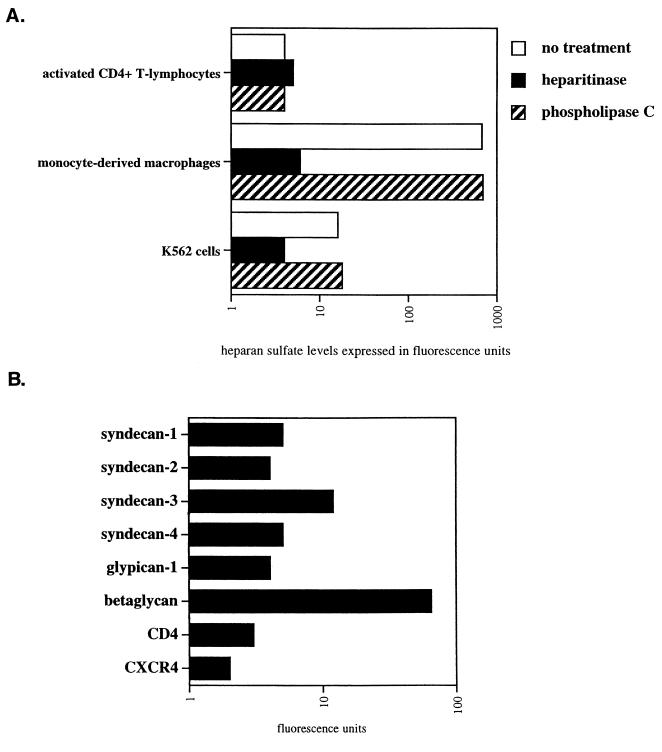

Cell surface expression of CD4 and HSPGs on primary HIV-1 target cells.

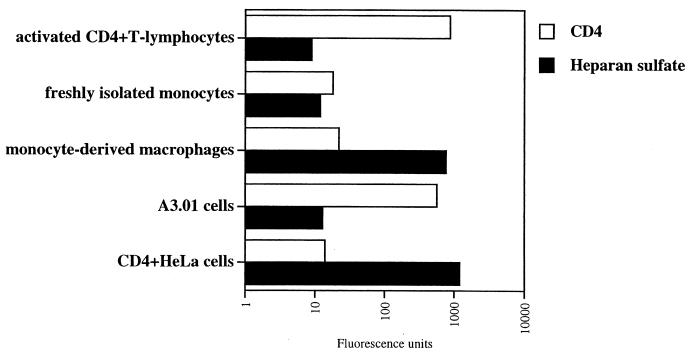

Despite the major role of macrophages in HIV-1 pathology, surprisingly, few studies have carefully analyzed their surface expression of HSPGs and CD4 on these cells. Indeed, the only two studies which have specifically addressed this issue obtained contradictory results (7, 34). Therefore, in the present study, we compared the cell surface expression of CD4 and HSPGs on primary cells. Specifically, activated CD4+ T lymphocytes, as well as freshly isolated monocytes and MDM, were isolated and analyzed for CD4 and HSPG surface expression by FACS analysis using anti-CD4 and anti-HS antibodies. CD4-positive HeLa cells and A3.01 T cells were used as controls. We found that activated CD4+ T lymphocytes, as well as A3.01 T cells, expressed very high CD4 levels but very low HSPG levels (Fig. 1). Furthermore, we found that freshly isolated monocytes expressed low levels of both CD4 and HSPGs. Importantly, we found that MDM expressed high HSPG levels but low CD4 levels. This finding suggests that the cellular differentiation from monocyte into macrophage upregulates the cell surface levels of HSPGs but does not influence CD4 expression. Interestingly, both MDM and CD4-positive HeLa cells express comparably low CD4 and high HSPGs levels. Note that we obtained similarly low levels of chemokine receptors CXCR4 and CCR5 on macrophages (data not shown). Thus, we show that the two major in vivo HIV-1 target cells display opposite patterns of expression of attachment receptors. Specifically, activated CD4+ T lymphocytes express high CD4 but low HSPGs levels, whereas MDM express low CD4 but high HSPG levels.

FIG. 1.

CD4+ T lymphocytes and MDM express opposite patterns of HIV-1 attachment receptors. Levels of cell surface CD4 and HS were determined by FACS analysis using anti-CD4 or anti-HS antibodies. Values are the geometric means expressed in fluorescence units (log scale). Results are representative of three independent experiments using four different donors.

HSPGs are absolutely required for HIV-1 attachment to MDM.

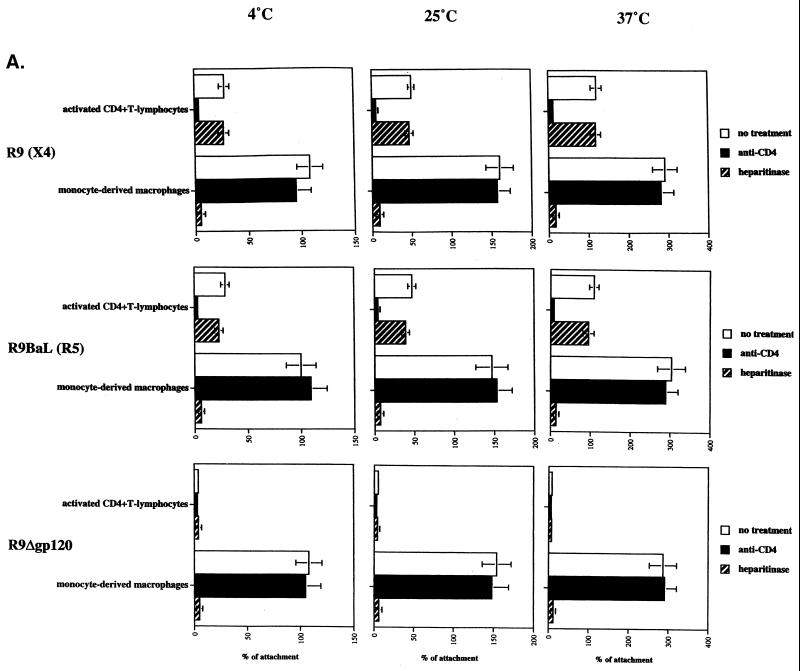

After demonstrating that activated CD4+ T lymphocytes and MDM exhibit opposite patterns of CD4 and HSPGs expression, we examined the role of these candidate attachment receptors in HIV-1 adsorption. It is important to emphasize that to date few studies focusing exclusively on HIV-1 attachment to macrophages have been performed. To determine the role of CD4 in HIV-1 attachment, activated T lymphocytes or MDM were tested for their ability to attach to HIV-1 in the presence or absence of anti-CD4 antibodies directed against the gp120-binding site of CD4 as described previously (18, 28). To determine the role of HSPGs in HIV-1 attachment, activated CD4+ T lymphocytes or MDM were pretreated or not with heparitinase, which removes cell surface HS moieties (18, 28). Removal of cell surface HS from MDM was verified by FACS analysis using an anti-HS antibody (data not shown). Activated CD4+ T lymphocytes and MDM were tested for their ability to adsorb HIV-1. Using a previously described assay (28), we tested the capacity of R9 (NL4.3, X4 virus), R9BaL (NL4.3 pseudotyped with BaL gp120, R5 virus), and R9Δgp120 (NL4.3 with deletion of gp120) to adsorb onto activated CD4+ T lymphocytes and onto MDM. Attachment studies were performed at 4, 25, and 37°C. We found that the capacity of target cells to attach to HIV-1 correlates with the temperature. Specifically, we observed a 1.5-fold attachment increase at 25°C compared to 4°C and a twofold increase at 37°C compared to 25°C. Furthermore, we found that anti-CD4 antibodies strongly decreased HIV-1 attachment to activated T-lymphocytes but did not diminish the adsorption of HIV-1 onto MDM (Fig. 2A). Note that we obtained similar results using soluble CD4 (data not shown). This suggests that gp120-CD4 interactions do not play a major role in HIV-1 attachment to MDM. In sharp contrast, we found that removal of cell surface HS totally inhibited the attachment of HIV-1 to MDM at all temperatures but did not influence HIV-1 attachment to activated CD4+ T-lymphocytes. Note that A3.01 T cells behaved like activated CD4+ T lymphocytes, whereas CD4-positive HeLa cells behaved like MDM (data not shown). Specifically, HIV-1 attaches to A3.01 T cells in a CD4-dependent manner, whereas it attaches to CD4-positive HeLa cells in an HSPG-dependent manner. Furthermore, we found that the capacity of MDM or CD4-positive HeLa cells to attach HIV-1 was three- to fivefold higher than that of activated CD4+ T lymphocytes or A3.01 T cells. Given that both MDM and CD4-positive HeLa cells express elevated HS levels (Fig. 1), it is likely that these high HS levels are a hallmark of adherent cells and are responsible for their high capacity to adsorb to HIV-1. Together these results suggest that HIV-1 does not require cell surface HSPGs to attach to target cells that express high CD4 levels, such as activated CD4+ T-lymphocytes, but requires cell surface HSPGs to attach to target cells which express low CD4 levels, such as MDM. Note that the requirement for HSPGs to attach to MDM was also observed for the primary JR-CSF virus (5) (data not shown). Importantly, the correlation between temperature and levels of attachment to MDM is observed regardless of the kind of gp120 employed, including R9, R9BaL, and R9 Δgp120. Most importantly, the observation that a virus which lacks gp120 still attaches to MDM at levels similar to those of wild-type virus strongly suggests that gp120 does not play a major role in the initial attachment of HIV-1 to MDM. Note that we obtained similar results using CD4+ HeLa (called P4) or CD4+ CCR5 HeLa (P4 CCR5) cells as targets, instead of MDM. If gp120 is not necessary for attachment to macrophages, it suggests that virus-associated proteins other than gp120 mediate HIV-1 attachment to macrophages via cell surface HSPGs. To test this premise, the virus gp120 with deleted (R9Δgp120) was analyzed for its capacity to attach to MDM in the presence of increasing concentrations of soluble heparin (HSPG analog). We found that heparin totally blocks gp120-deleted virus attachment to MDM, confirming that virus surface proteins, other than gp120, are responsible for HIV-1 adsorption to macrophages via HSPGs (Fig. 2B). Altogether these results suggest that cell surface HS is necessary for the initial HIV-1 attachment to MDM. This also suggests that the low CD4 levels on MDM are not sufficient to mediate HIV-1 attachment in the absence of HSPGs.

FIG. 2.

HIV-1 requires HSPGs to attach to and to infect MDM. (A) Target cells were tested for their capacity to attach HIV-1. Briefly, cells were exposed to 10 ng of p24 of purified R9, R9BaL, and R9Δgp120 viruses produced from 293T transfected cells for 30 min at 4, 25, or 37°C; extensively washed to remove unattached virus; and lysed. Attachment levels were quantified by p24 ELISA. Results are expressed as a percentage of attachment by fixing the percentage of R9BaL attachment to MDM at 4°C at 100. Results represent the average of two independent experiments (donors). To determine the role of HS or CD4 in HIV-1 attachment, cells were pretreated with heparitinase or preincubated with anti-CD4 antibodies directed against the gp120-binding site of CD4. (B) R9Δgp120 was tested for its ability to attach to MDM in the presence of heparin. MDM were exposed to 10 ng of p24 of purified R9Δgp120 viruses produced from 293T cells for 30 min at 4°C in the presence of increasing concentrations of soluble heparin. Results are expressed as a percentage of attachment by fixing the percentage of R9Δgp120 attachment to MDM in the absence of heparin at 100. Results represent the average of three independent experiments (donors). (C) MDM or activated CD4+ T lymphocytes pretreated or not with heparitinase or anti-CD4 antibodies were tested for their ability to support HIV-1 replication. R9BaL and R9 viruses produced from 293T cells were used to infect MDM and activated CD4+ T lymphocytes, respectively. Replication was monitored by p24 ELISA. Results are representative of three independent experiments using different donors. In all panels, error bars represent standard deviations.

Given the vast discrepancy between the levels of HSPG-mediated attachment to MDM and the levels of CD4-mediated attachment, we asked if the HSPGs interactions represent a necessary precursor for HIV-1 infection or represent merely a dead-end attachment. Specifically, we investigated whether the removal of surface HSPGs from MDM would not only abrogate viral attachment but also prevent subsequent infectivity. To explore this issue, MDM or activated CD4+ T lymphocytes pretreated or not with heparitinase were exposed to R9BaL or R9, respectively. We found that HS removal did not affect HIV-1 replication in activated CD4+ T lymphocytes, confirming the central role of CD4 in both attachment and infection in CD4+ T lymphocytes (Fig. 2C). By contrast, this treatment strongly decreased HIV-1 replication in MDM (Fig. 2C). This result indicates that the HSPG-mediated attachment is an essential step in HIV-1 infection in MDM. This result also corroborates our attachment data obtained above suggesting that HSPGs are absolutely required for HIV-1 attachment to MDM, but not to activated CD4+ T lymphocytes. Note that this requirement for HSPGs in HIV-1 replication in MDM was also observed for the primary virus JR-CSF (data not shown). Altogether these data demonstrate that HSPGs are essential attachment receptors for HIV-1 replication in its major target in vivo, the macrophage.

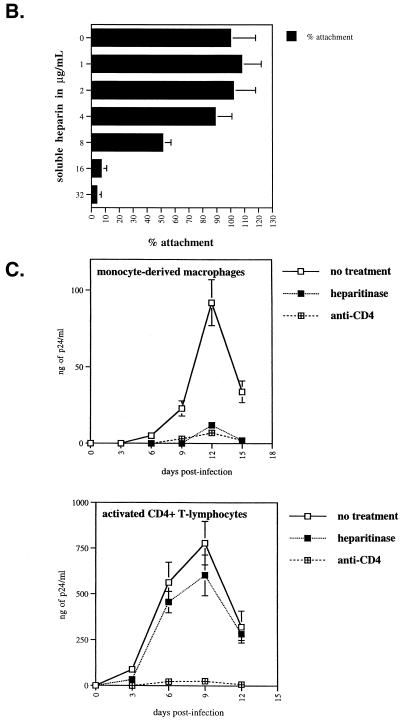

Human MDM express syndecans, betaglycan, but not glypicans.

After demonstrating for the requirement of cell surface HS for HIV-1 attachment to MDM, we examined the representation of specific HSPGs on the surface of MDM. The best-characterized cell surface HSPGs fall into three groups, the syndecan, glypican, and betaglycan family proteins. To date, there are four syndecans (syndecan-1 to -4) and six glypicans (glypican-1 to -6), the latter being linked to the cell membrane by a GPI anchor (2). Most cells and tissues express at least one syndecan family member, while many express multiple syndecans in expression patterns specific to individual cell types and tissues. For example, syndecan-1 is expressed on epithelial cells and malignant plasma cells, syndecan-2 is found on fibroblasts, and syndecan-3 is found predominantly in the central nervous system, whereas syndecan-4 is more ubiquitous (2). Glypicans are also widely expressed HSPGs and commonly occur on the cell surface with one or more of the syndecans. Perhaps the most widely expressed cell surface HSPG is betaglycan. Thus, we examined the cell surface expression of MDM for syndecans, glypicans and betaglycan.

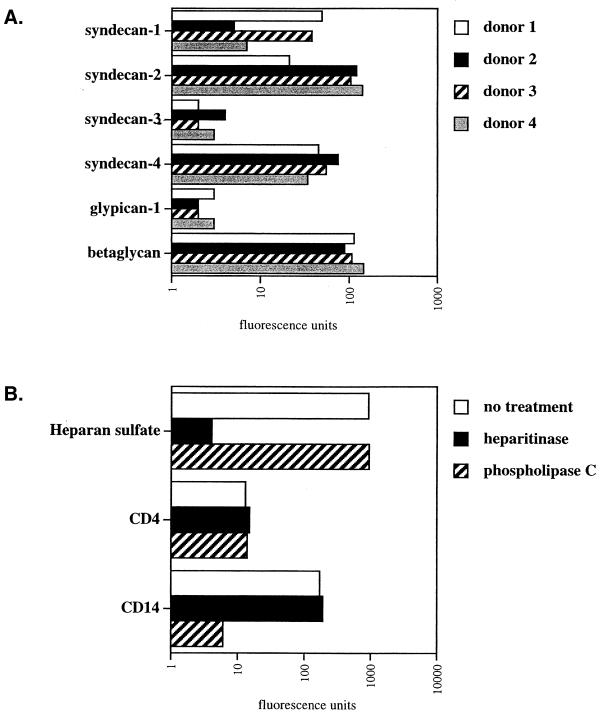

First, we found that betaglycan is abundantly expressed on MDM (Fig. 3A). Second, we found that MDM express high levels of syndecan-1, syndecan-2, and syndecan-4 but low levels of syndecan-3. It is important to note that we observed a similar pattern among several donors. However, levels of expression between different syndecans displayed some variations. For example, MDM from one donor (donor 1) expressed very high levels of syndecan-1 and syndecan-4 but low levels of syndecan-2, whereas MDM from another donor (donor 2) expressed high levels of syndecan-2 and syndecan-4 but low levels of syndecan-1. Furthermore, we found that glypican-1 is weakly expressed on MDM. It is important to note that unfortunately antibodies directed against glypican-2 to -6 are not yet available. Nevertheless, we employed another approach to determine whether these members of the glypican family are expressed on MDM. We took advantage of the fact that phospholipase C possesses the capacity to remove all proteins attached to the cell surface via a GPI anchor including glypicans. Thus, MDM were pretreated with phospholipase C and subsequently examined for their total HS cell surface expression using anti-HS antibodies. If heparan sulfated glypicans are removed from the plasma membrane upon enzymatic treatment, one would expect to observe a decrease in HS levels by FACS analysis. Importantly, we found that the enzymatic treatment did not decrease the cell surface HS levels on MDM (Fig. 3B). This strongly suggests that glypicans are absent or weakly expressed on MDM. Note that CD4 remains intact after phospholipase C treatment consistent with the fact that CD4 is a transmembrane protein, but not a GPI-linked protein. To verify the efficacy of the enzymatic treatment, we examined the levels of CD14 which, like glypicans, is attached to the cell surface via a GPI anchor. Given that CD14 is not detected by FACS using an anti-CD14 antibody after phospholipase C treatment, this indicates that GPI-linked cell surface proteins have been removed from the cell surface. It is important to note that we and others found that phospholipase C treatment of MDM or CD4-positive HeLa cells does not decrease HIV-1 infection (18; data not shown). This further suggests that glypicans do not play a major in HIV-1 attachment or infection of MDM. Altogether, these results suggest that at least two classes of HSPGs, syndecan and betaglycan, may contribute to the initial attachment of HIV-1 to MDM.

FIG. 3.

HSPG cell surface composition of human MDM. (A) Syndecan, glypican, and betaglycan expression of MDM was examined by FACS analysis using antibodies directed against syndecan-1, -2, -3, -4; glypican-1; and betaglycan. Results represent the geometric means expressed in fluorescence units (log scale). (B) MDM pretreated or not with heparitinase or phospholipase C were examined for their cell surface expression of HS, CD4, and CD14 by FACS analysis using specific antibodies. Values are the geometric means expressed in fluorescence units (log scale). Results are representative of two independent experiments using different donors.

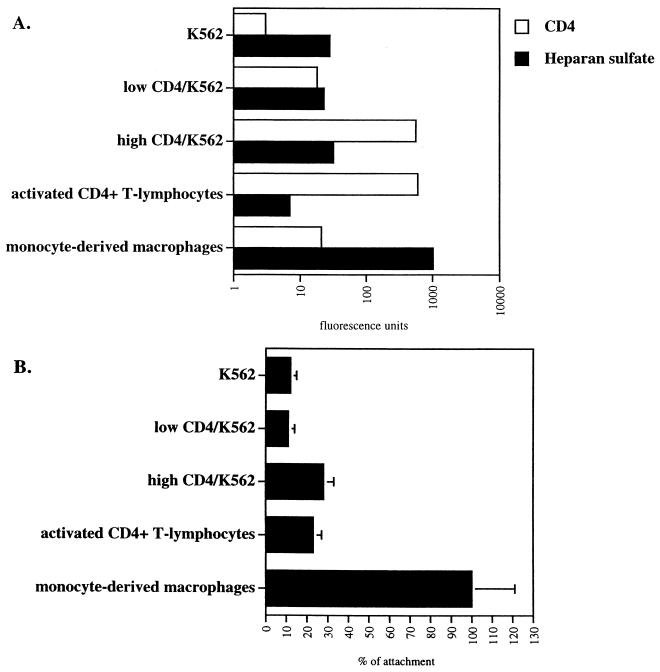

HSPGs can compensate for low CD4 levels in HIV-1 attachment.

We showed that activated CD4+ T lymphocytes express high levels of CD4 but no detectable HSPG levels (Fig. 1). Furthermore, we demonstrated that HIV-1 attaches to activated CD4+ T lymphocytes via CD4 but not via HSPGs (Fig. 2A). In sharp contrast, we showed that MDM express high levels of HSPG but low CD4 levels (Fig. 1). We also found that HIV-1 requires HSPGs, but not CD4, to attach to MDM (Fig. 2A). Based on these observations, we postulated that the high CD4 levels on activated CD4+ T lymphocytes are sufficient to attach HIV-1, whereas the high levels of HSPGs on MDM compensate for the low CD4 levels in viral adsorption.

To explore this hypothesis, we took advantage of the human K562 cell line, which expresses low levels of HS and no CD4. The K562 cell line is an erythroleukemia cell line established from the pleural effusion of a 53-year-old female with a chronic myelogenous leukemia (17). Firstly, we analyzed the HS surface levels of K562 cells. Cells pretreated with heparitinase were used as negative controls. MDM and activated CD4+ T lymphocytes were also used as controls. We found that K562 cells express very low HS levels (Fig. 4A). Second, we examined the HSPG surface expression of K562 cells. We found that betaglycan is highly expressed on K562 cells (Fig. 4B). In contrast, we found that syndecan-1, -2, and -4 were not expressed on these cells, whereas syndecan-3 was slightly expressed. Furthermore, we found that glypican-1 is not expressed on K562 cells. Given that phospholipase C treatment, which removes all GPI-linked proteins from the cell surface, did not decrease HS levels on K562 cells (Fig. 4A), this suggests that no members of the glypican family are expressed on these cells. It is likely that the presence of betaglycan contributes to the low, but significant cell surface HS levels. These results confirmed a previous study which showed that K562 cells do not express any members of the syndecan or glypican HSPG families (32). Thirdly, we examined the expression of CD4 on K562 cells and found as expected that these cells did not express CD4 molecules. Furthermore, we found that K562 cells express little of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 which is necessary for HIV-1 internalization.

FIG. 4.

Human K562 cells express betaglycan but not syndecans or glypicans. (A) K562 cells, activated CD4+ T lymphocytes, and MDM pretreated or not with heparitinase or phospholipase C were examined for their HS cell surface expression by FACS analysis using anti-HS antibodies. Values are the geometric means expressed in fluorescence units (log scale). Results are representative of two independent experiments. (B) K562 cells were examined for their HSPG, CD4, and CXCR4 cell surface composition by FACS analysis using specific antibodies. Values are the geometric means expressed in fluorescence units (log scale). Results are representative of two independent experiments.

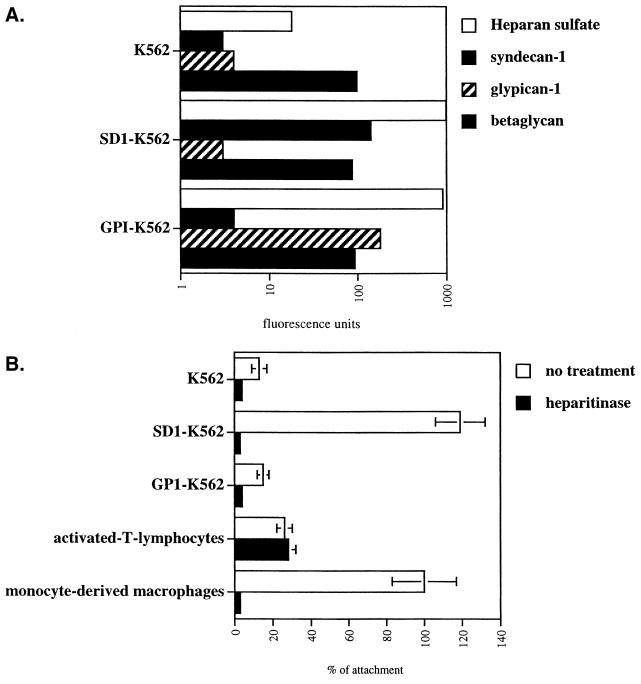

To investigate the respective roles of CD4 and HSPGs in HIV-1 attachment, K562 cells were stably transfected either with human syndecan-1 or with glypican-1 as described previously (32). Both syndecan-1 and glypican-1 were chosen as representatives of their respective families, because both are widely expressed on human cells, and are the best-characterized HSPGs (2). Parental K562, syndecan-1-transfected (SD1-K562), and glypican-1-transfected (GP1-K562) cells were examined for the cell surface expression of betaglycan, syndecan-1, glypican-1, as well as for total HS expression by FACS analysis. As expected, we found that syndecan-1 and glypican-1 are highly expressed on SD1-K562 and GP1-K562 cells compared to parental K562 cells (Fig. 5A). Note that betaglycan levels were found to be similar between the three K562 cell lines. Furthermore, we found that the introduction of both syndecan-1 and glypican-1 into the K562 cells (SD1- and GP1-K562 cells) greatly elevated levels of cell surface HS compared to K562 parental cells. It is important to note that SD1-K562 and GP1-K562 cell lines express similar levels of total HS as described previously (32).

FIG. 5.

Syndecan promotes HIV-1 attachment to K562 cells. (A) Parental, syndecan-1-, and glypican-1-transfected K562 cells were examined for their cell surface composition in HS, syndecan-1, glypican-1, and betaglycan by FACS analysis using specific antibodies. Values are the geometric means expressed in fluorescence units (log scale). (B) Parental, syndecan-1-, and glypican-1-transfected K562 cells were tested for their ability to attach R9. Activated CD4+ T lymphocytes and MDM were used as controls. Target cells were pretreated or not with heparitinase to remove cell surface HS. Results are expressed as a percentage of attachment by fixing the percentage of viral attachment to MDM at 100. Results represent the average of two independent experiments.

Parental K562, SD1-K562, and GP1-K562 cells were then tested for their ability to attach HIV-1 as described previously (28). Parental, SD1-, and GP1-K562 cells pretreated with heparitinase were used a negative controls, whereas MDM and activated CD4+ T lymphocytes were used as positive controls. Given that R9 (X4 virus) and R9BaL (R5 virus) attach similarly to MDM (Fig. 2A), we selected R9 to test the capacity of the K562 cells to attach HIV-1. We found that the capacity of parental K562 to attach HIV-1 is low, close to that of heparitinase-treated cells (Fig. 5B). This low capacity of parental K562 cells to attach HIV-1 correlates with their low HS surface levels. Interestingly, we found that HIV-1 attachment onto GP1-K562 cells, which express very high HS levels (Fig. 5A), is comparable to that of of the parental K562 cells. This result indicates that glypican-1, although highly decorated with heparan sulfated chains, does not possess the capacity to mediate HIV-1 attachment. In sharp contrast to parental or GP1-K562 cells, we found that SD1-K562 cells strongly attached HIV-1. Given that both GP1- and SD1-K562 cells express similar levels of cell surface HS (Fig. 5A), this result strongly suggests that HIV-1 attachment does not depend merely on high HS expression but depends on the presence of specific members of the HSPG family. This specificity implicates syndecan-1 as a candidate attachment receptor for HIV-1. To verify that syndecan-1 mediates HIV-1 attachment via its HS chains, SD1-K562 cells were pretreated with heparitinase and tested for their capacity to adsorb HIV-1. As expected, we found that heparitinase treatment totally blocked HIV-1 attachment to SD1-K562 cells (Fig. 5B), demonstrating that syndecan-1 mediates the initial HIV-1 adsorption via its polyanionic HS chains. It is important to note that the high capacity of SD1-K562 cells to attach HIV-1 is similar to that of MDM. These comparable capacities for virus attachment between SD1-K562 and MDM may arise from the fact that the major HSPG molecules expressed on MDM are syndecans.

We next investigated the role of CD4 in HIV-1 attachment. Specifically, we asked whether high CD4 levels on parental K562 cells would promote HIV-1 attachment, similarly to syndecan-1 (Fig. 5B). To explore this issue, parental K562 cells were transfected with human CD4. CD4-positive transfected K562 cells were sorted by FACS using an anti-CD4 antibody. Two distinct populations were chosen: one population of K562 cells expressing high CD4 levels (called high CD4/K562), similar to activated CD4+ T lymphocytes, and the other expressing low but significant CD4 levels, similar to MDM (called low CD4/K562) (Fig. 6A). High and low CD4/K562 cells were then tested for their ability to attach to HIV-1 as described above. It is crucial to note that both CD4 and HS levels were carefully analyzed by FACS concomitantly with the attachment assay. We found that the capacity of low CD4/K562 cells to attach to HIV-1 is similar to that of CD4-negative parental K562 cells (Fig. 6B). In contrast, we found that the capacity of high CD4/K562 cells to attach to HIV-1 is higher than that of parental K562 cells. Importantly, the attachment levels of high CD4/K562 cells are similar to those of activated CD4+T lymphocytes (Fig. 6B). This suggests that high, but not low levels of CD4 partially promote HIV-1 attachment.

FIG. 6.

High CD4 levels partially restore HIV-1 attachment to K562 cells. (A) Parental and CD4-transfected K562 cells were analyzed for CD4 and HS cell surface expression by FACS analysis. Activated CD4+ T lymphocytes and MDM were used as controls. Values are the geometric means expressed in fluorescence units (log scale). Results represent the average of three independent experiments. (B) Parental and CD4-transfected K562 cells were tested for their capacities to attach R9. Results are expressed as a percentage of attachment by fixing the percentage of viral attachment to MDM at 100. Results represent the average of two independent experiments.

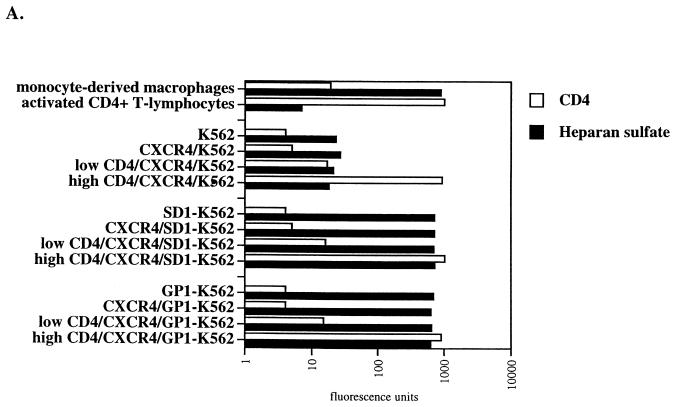

After demonstrating that one member of the HSPG family can compensate for low CD4 levels in HIV-1 attachment, we investigated their participation in HIV-1 replication. Given that K562 cells do not constitutively express the chemokine receptors or CD4, both CXCR4 and CD4 were successively introduced into parental K562, SD1- and GP1-K562 cell lines. The pBABE-CXCR4-puromycin plasmid was used to introduce CXCR4 into K562 cells. Puromycin-resistant cells were sorted by FACS using an anti-CXCR4 monoclonal antibody. Parental cells were used as negative controls. We selected cell populations which express CXCR4 levels comparable to those of activated CD4+ T lymphocytes or MDM (Fig. 7A). CXCR4/K562, CXCR4/SD1-K562 and CXCR4/GP1-K562 cell lines were then transfected with CD4, sorted by FACS using an anti-CD4 antibody. Given that activated CD4+ T lymphocytes and MDM express high and low CD4 levels respectively, we selected two idstinct cell populations expressing high or low CD4 levels (Fig. 7A).

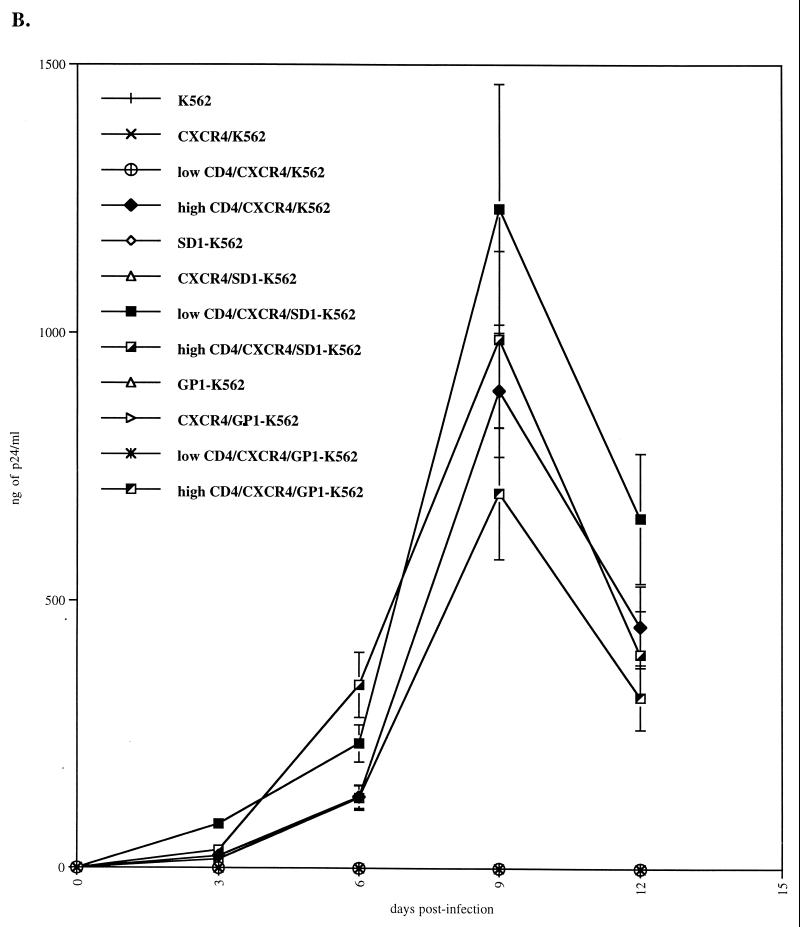

FIG. 7.

Syndecan restores HIV-1 replication in K562 cells which express low CD4 levels. (A) Parental, syndecan-1-, and glypican-1-transfected K562 cells were transfected with CXCR4 and CD4. CD4 and HS surface expression was analyzed by FACS using specific antibodies. (B) CXCR4/CD4-positive K562 cells were tested for their ability to support R9 replication. Replication was monitored by p24 ELISA. Results are representative of three independent experiments.

CXCR4-positive cells expressing low or high CD4 levels were then tested for their permissivity to HIV-1. Parental cells were used as negative controls. As expected, HIV-1 did not replicate in K562 cells which lack either CD4 or CXCR4 or both (Fig. 7B). Importantly, we found that HIV-1 did not replicate in CXCR4/K562 cells or in CXCR4/GP1-K562 cells that express low CD4 levels (Fig. 7A). This correlates with our data above (Fig. 5B) which showed that both parental and GP1-K562 cells as well as cells which express low CD4 levels do not possess the capacity to attach HIV-1. In sharp contrast, we found that CXCR4/K562 cells or CXCR4/GP1-K562 cells that express high CD4 levels support HIV-1 replication (Fig. 7B). This corroborates our previous results, which showed that high CD4 levels may partially substitute for HSPGs in HIV-1 attachment (Fig. 6B). This also correlates with our data which showed that activated CD4+ T lymphocytes which do not express HS on their surface efficiently support HIV-1 replication (Fig. 2B). Most importantly, we found that HIV-1 replicates in CXCR4/SD1-K562 cells which express low CD4 levels (Fig. 7B). This strongly suggests that the presence of syndecan-1 can compensate for low CD4 levels for HIV-1 attachment and thus replication.

Altogether, these results suggest that the low CD4 levels on macrophages are not sufficient to support HIV-1 attachment. Furthermore, these data demonstrate that cell surface HSPGs are absolutely required for HIV-1 replication in macrophages. Most importantly, we demonstrate that a single family of HSPGs—the syndecans—efficiently mediates HIV-1 attachment and represents an abundant class of attachment receptors on macrophages.

DISCUSSION

Macrophages have long been known as targets of HIV-1 in infected individuals (1, 8, 14, 15, 26, 30, 36). Specifically, macrophages are thought to represent one of the first cell types in the body to be infected during the early stage of HIV-1 transmission (1, 6, 26). Furthermore, macrophages and microglia were identified as one of the major target cells in the central nervous system of patients with AIDS dementia complex (15, 36). Most importantly, macrophages, together with naïve and memory T cells (3, 6, 25), are thought to represent a major viral reservoir in vivo. Specifically, Igarashi et al. recently showed that tissue macrophages in the lymph nodes, spleen, gastrointestinal tract, liver, and kidney of rhesus macaques sustain high plasma virus loads even in the absence of CD4+ T cells (14). Together, these studies point to macrophages as key players in HIV-1 pathogenesis.

In the present study, we examined the specific requirements for HIV-1 entry into one of its major in vivo target cells, the macrophages. HIV-1 entry is a multistep process, including initial attachment of the virus to the target cell surface, followed by fusion between the viral and cellular membranes, and culminating in the internalization of the viral genome into the cytosol of the target cells. In this report, we principally focused on the initial viral attachment to macrophages. Given that CD4 was thought to be the main attachment receptor for HIV-1, we first examined the cell surface expression of CD4 on macrophages. We found that in contrast to CD4+ T lymphocytes, macrophages express very low CD4 levels. Therefore, we asked whether this low CD4 level on macrophages is sufficient to support HIV-1 attachment to these cells or whether cell surface proteins other than CD4 are required for this process. First, we found that macrophages possess a very high capacity to attach to HIV-1 compared to CD4+ T lymphocytes. However, this high capacity to attach to HIV-1 is not mediated by CD4. Specifically, we found that the addition of antibodies which prevent the interaction between CD4 and gp120 does not diminish HIV-1 attachment to macrophages. This suggests that cell surface proteins other than CD4 mediate HIV-1 attachment to macrophages.

In a search for candidate attachment receptors other than CD4, we found that macrophages express high levels of HSPGs. This finding seems to contradict a previous study suggesting that macrophages express only a few HSPGs molecules (34). This apparent discrepancy probably results from different stages of differentiation of MDM utilized in these two studies. Corroborating this hypothesis, we (in this study) and recently others (7) showed that freshly isolated monocytes express very low HSPG levels, whereas MDM express high HSPG levels. This finding strongly suggests that the cellular differentiation from monocyte into macrophage upregulates the cell surface levels of HSPGs. Note that freshly isolated monocytes were found to be relatively refractory to HIV-1 infection (26). Interestingly, the block in infectivity was mapped to the early steps of infection. We can speculate that the scarcity of the two candidate attachment receptors on monocytes—CD4 and HSPGs—may represent a critical obstacle for HIV-1 entry into these cells.

After demonstrating that HSPGs are abundantly expressed on MDM, we asked whether they represent the main source of attachment receptors responsible for the high capacity of MDM to adsorb viral particles. To explore this issue, MDM were treated with heparitinase, which removes all cell surface HS chains but does not alter CD4. Under these conditions, we found that MDM lost their capacity to attach HIV-1. This demonstrates that HSPGs, but not CD4, represent the major class of HIV-1 attachment receptors on MDM.

Our observation that R9, R9BaL, and R9Δgp120 attach similarly to macrophages strongly suggests that gp120 is not necessary for the initial attachment of HIV-1 to macrophages. Furthermore, our findings that soluble heparin prevents the attachment of the gp120-deleted virus (R9Δgp120) to macrophages further suggests that virus-associated proteins other than gp120 participate in HIV-1 adsorption to macrophages. Previous studies suggest that R5 gp120 (such as BaL) has a lower affinity for CD4, as well as for HSPGs, than does X4 gp120 (such as NL4.3). Specifically, Moulard et al. showed that X4 gp120, via basic residues in the V3 loop, binds heparin with a higher affinity than R5 gp120 (22). How does one reconcile the previous observation that gp120 possesses the intrinsic capacity to bind to HSPGs, with our observation that HIV-1 lacking gp120 efficiently attaches to macrophages? A simple explanation for this apparent discrepancy is that the level of contribution of gp120 HSPGs interactions to attachment is negligible, compared to that of other virus-associated protein-HSPGs interactions (those abolished by the addition soluble heparin). Furthermore, it is crucial to note that the notion that gp120 binds HSPGs arises exclusively from studies using recombinant gp120 instead of whole virus. Thus, the use of recombinant gp120 may not be appropriate for determining the role of these basic residues in HIV-1 attachment to target cells within the context of whole virus. Indeed, we cannot exclude the possibility that any recombinant protein containing a basic rich region (such as gp120) possesses the capacity to bind to heparin or HSPGs.

It is well known that HIV-1 can attach to a large variety of nonpermissive cells which do not express either CD4 or appropriate chemokine receptors. However, these attached viruses are unable to successfully establish infection. This indicates that virus attachment does not necessarily correlate with infection. Thus, we investigated whether virus-HSPGs interactions represent a necessary precursor for HIV-1 infection of MDM or represent merely a dead-end attachment. Importantly, we found that removal of HS chains totally blocks HIV-1 replication in MDM, despite the presence of CD4. This result indicates that HSPGs are not only accessory attachment receptors, but are absolutely required for viral replication in a major in vivo target of HIV-1, the macrophage. By analogy with cytokines and growth factors, HSPGs likely concentrate viruses at the surface of MDM, increasing the probability of HIV-1 particles to interact with scarce CD4 molecules. Given that MDM possess a very high capacity to attach to HIV-1, a presumably large majority of viral particles initially attached to MDM via HSPGs unable to interact with CD4 will lead to a dead-end infection. Nevertheless, our study clearly demonstrates that HSPG interactions are necessary events which ensure MDM infection by HIV-1. It is important to emphasize that although our results suggest that CD4 plays a minor role in the initial attachment of HIV-1 to MDM, CD4 is absolutely required for the postattachment steps of entry—fusion and internalization.

Why has HIV-1 evolved to bind to HSPGs? One simple explanation is that HIV-1 needs HSPGs to infect one of its major targets in vivo—the macrophage. Indeed, we showed that CD4 levels on macrophages are too low to mediate the initial viral attachment. Therefore, HIV-1 requires HSPGs as supplementary, but necessary, attachment receptors for macrophage infection. Another possibility to explain why HIV-1 has evolved to bind to HSPGs is that viruses attached via HSPGs on the surface of refractory cells represent an in trans source of infection for permissive cells. Specifically, since most HSPG-decorated cells are not permissive to HIV-1 (CD4 negative), it may seem like an inefficient and abortive strategy for replication. However, it has been shown that dendritic cells (DC), which are not permissive to HIV-1, nevertheless serve as a reservoir for trans infection of permissive cells (12). Specifically, it has been shown that the glycoprotein DC-SIGN mediates HIV-1 adsorption to DC and potentiates HIV-1 infection in trans of permissive cells, even after an extended period far beyond the known half-life of free virus (12). By analogy, HIV-1 attached to nonpermissive cells via HSPGs may serve as an additional source of in trans infection for permissive cells. Corroborating this hypothesis, a recent study showed that CD4-negative cells bind HIV-1 and efficiently transfer the virus to T cells (23). However, the endurance of HIV-1 attached to host cells via HSPGs remains to be determined.

After demonstrating that HSPGs are absolutely required for HIV-1 replication in macrophages, we analyzed the surface HSPG composition of MDM. Importantly, we found that syndecans but not glypicans are abundantly expressed on MDM. Specifically, we showed that syndecan-1, -2, and -4 are all well represented on macrophages. Furthermore, we found that phospholipase C, which removes glypicans, did not decrease the total HS levels of macrophages and did not influence HIV-1 attachment, suggesting that glypicans are not expressed on macrophages. These results strongly suggest that syndecans represent the major source of HSPGs on MDM. To determine whether syndecans are responsible for HIV-1 attachment to MDM, we introduced syndecan into K562 cells, which express low HS levels, and tested the capacity of these cells to attach to HIV-1. Importantly, we found that the introduction of syndecan-1 or glypican-1 into K562 cells promotes the levels of HS on the surface of these cells (SD1-K562 and GP1-K562 cells) and that the total HS levels between these two cell lines were comparable. Interestingly, we found that HIV-1 attaches three- to fivefold better to cells which express syndecan-1 than cells which express glypican-1. This suggests that the capacity of syndecan-1 at least on K562 cells to attach to HIV-1 is higher than that of glypican-1. While we used syndecan-1 as a representative member of the syndecan family, we found that both syndecan-2 and syndecan-4 in K562 cells also possess the high capacity to attach HIV-1 (data not shown). Furthermore, we found in the present study that the population of K562 cells which express low CD4 levels is not permissive to HIV-1. However, we showed that the introduction of syndecan-1 into these nonpermissive cells renders them infectible by promoting HIV-1 attachment. Importantly, a close parallel can be found in vivo: the macrophage which expresses low CD4 but high syndecan levels. Given that syndecans are abundantly expressed on MDM, altogether these observations strongly point to syndecans as a major class of attachment receptor for HIV-1. However, a definitive proof for a direct role of syndecans in HIV-1 replication would depend on the existence of antibodies directed against the critical motifs within HS chains which unfortunately are not currently available.

A number of different criteria may account for the enhanced capacity of syndecan-1 to attach to HIV-1 compared to glypican-1. First, while the gross compositions in HS levels are similar between syndecan-1 and glypican-1, subtle differences in the fine structure of the HS chains may be important for virus interactions. Secondly, the structure of the core proteins may influence the spatial distribution of the HS chains on the surface of target cells. For example, the predicted structure of glypican-1 is globular, whereas that of syndecan-1 is extended (2). Based on these structure predictions, it has been proposed that the HS chains of glypican-1 lie close to the plasma membrane, whereas those of syndecan-1 are thought to be more distal. Which of these criteria is significant for HIV-1 attachment remains to be elucidated. Although we showed that glypican-1 fails to support efficient HIV-1 attachment to K562 cells, we cannot exclude the possibility that other members of the glypican family can support HIV-1 adsorption. However, it is unlikely that glypicans play a major role in HIV-1 attachment to macrophages. Indeed, we showed that phospholipase C treatment, which removes cell surface glypicans, does not affect HIV-1 attachment to MDM. Nevertheless, our present study does not preclude a role for glypicans in HIV-1 attachment to other in vivo target cells such as microglia and DC.

In conlusion, this study reports that HSPGs are absolutely required for HIV-1 replication in macrophages. Specifically, we showed that the low levels of CD4 on macrophages are insufficient to mediate the initial attachment of HIV-1. We found that cell surface HSPGs serve as necessary receptors for attachment to macrophages, perhaps to compensate for the low CD4 levels. Furthermore, several lines of evidence point to the participation of a single family of HSPGs in HIV-1 adsorption to macrophages—the syndecans. Given that macrophages are a major target for HIV-1 in vivo, reagents which disrupt the interaction between HIV-1 and syndecans (or HSPGs) represent an attractive class of novel antiviral agents.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. Kuhns for secretarial assistance, Rebecca Sabbe for technical assistance, and D. Mosier for critically reading the manuscript.

This work was supported by funds from the Department of Immunology at The Scripps Research Institute.

Footnotes

This is publication no. 13562-IMM from the Department of Immunology, The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, Calif.

REFERENCES

- 1.Appleman M E, Marshall D W, Brey R L, Houk R W, Beatty D C, Winn R E, Melcher G P, Wise M G, Sumaya C V, Boswell R N. Cerebrospinal fluid abnormalities in patients without AIDS who are seropositive for the human immunod eficiency virus. J Infect Dis. 1988;158:193–199. doi: 10.1093/infdis/158.1.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernfield M, Gotte M, Park P W, Reizes O, Fitzgerald M L, Lincecum J, Zako M. Functions of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:729–777. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brooks D G, Kitchen S G, Kitchen C M, Scripture-Adams D D, Zack J A. Generation of HIV latency during thymopoiesis. Nat Med. 2001;7:459–464. doi: 10.1038/86531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Callahan L N, Phelan M, Mallinson M, Norcross M A. Dextran sulfate blocks antibody binding to the principal neutralizing domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 without interfering with gp120-CD4 interactions. J Virol. 1991;65:1543–1550. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.3.1543-1550.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cann A J, Churcher M J, Boyd M, O'Brien W, Zhao J Q, Zack J, Chen I S. The region of the envelope gene of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 responsible for determination of cell tropism. J Virol. 1992;66:305–309. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.1.305-309.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chun T W, Carruth L, Finzi D, Shen X, DiGiuseppe J A, Taylor H, Hermankova M, Chadwick K, Margolick J, Quinn T C, Kuo Y H, Brookmeyer R, Zeiger M A, Barditch-Crovo P, Siliciano R F. Quantification of latent tissue reservoirs and total body viral load in HIV-1 infection. Nature. 1997;387:123–124. doi: 10.1038/387183a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clasper S, Vekemans S, Fiore M, Plebanski M, Wordsworth P, David G, Jackson D G. Inducible expression of the cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycan syndecan-2 (fibroglycan) on human activated macrophages can regulate fibroblast growth factor action. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:24113–24123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.34.24113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis L E, Hjelle B L, Miller V E, Palmer D L, Llewellyn A L, Merlin T L, Young S A, Mills R G, Wachsman W, Wiley C A. Early viral brain invasion in iatrogenic human immunodeficiency virus infection. Neurology. 1992;42:1736–1739. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.9.1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dick A D, Pell M, Brew B J, Foulcher E, Sedgwick J D. Direct ex vivo flow cytometric analysis of human microglial cell CD4 expression: examination of central nervous system biopsy specimens from HIV-seropositive patients and patients with other neurological disease. AIDS. 1997;11:1699–1708. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199714000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fouts T R, Binley J M, Trkola A, Robinson J E, Moore J P. Neutralization of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 primary isolate JR-FL by human monoclonal antibodies correlates with antibody binding to the oligomeric form of the envelope glycoprotein complex. J Virol. 1997;71:2779–2785. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.2779-2785.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gallay P, Hope T, Chin D, Trono D. HIV-1 infection of nondividing cells through the recognition of integrase by the importin/karyopherin pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9825–9830. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geijtenbeek T B, Kwon D S, Torensma R, van Vliet S J, van Duijnhoven G C, Middel J, Cornelissen I L, Nottet H S, KewalRamani V N, Littman D R, Figdor C G, van Kooyk Y. DC-SIGN, a dendritic cell-specific HIV-1-binding protein that enhances trans-infection of T cells. Cell. 2000;100:587–597. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80694-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haywood A M. Virus receptors: binding, adhesion strengthening, and changes in viral structure. J Virol. 1994;68:1–5. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.1.1-5.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Igarashi T, Brown C R, Endo Y, Buckler-White A, Plishka R, Bischofberger N, Hirsch V, Martin M A. Macrophage are the principal reservoir and sustain high virus loads in rhesusmacaques after the depletion of CD4+ T cells by a highly pathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus/HIV type 1 chimera (SHIV): implications for HIV-1 infections of humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:658–663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.021551798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koenig S, Gendelman H E, Orenstein J M, Dal Canto M C, Pezeshkpour G H, Yungbluth M, Janotta F, Aksamit A, Martin M A, Fauci A S. Detection of AIDS virus in macrophages in brain tissue from AIDS patients with encephalopathy. Science. 1986;233:1089–1093. doi: 10.1126/science.3016903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kost T A, Kessler J A, Patel I R, Gray J G, Overton L K, Carter S G. Human immunodeficiency virus infection and syncytium formation in HeLa cells expressing glycophospholipid-anchored CD4. J Virol. 1999;65:3276–3283. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.6.3276-3283.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lozzio B B, Lozzio C B. Properties of the K562 cell line derived from a patient with chronic myeloid leukemia. Int J Cancer. 1997;19:136. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910190119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mondor I, Ugolini S, Sattentau Q J. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 attachment to HeLa CD4 cells is CD4 independent and gp120 dependent and requires cell surface heparans. J Virol. 1998;72:3623–3634. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3623-3634.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore J P, Binley J. HIV. Envelope's letters boxed into shape. Nature. 1998;393:630–631. doi: 10.1038/31359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moore J P, McKeating J A, Huang Y X, Ashkenazi A, Ho D D. Virions of primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates resistant to soluble CD4 (sCD4) neutralization differ in sCD4 binding and glycoprotein gp120 retention from sCD4-sensitive isolates. J Virol. 1992;66:235–243. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.1.235-243.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mosier D E, Picchio G R, Gulizia R J, Sabbe R, Poignard P, Picard L, Offord R E, Thompson D A, Wilken J. Highly potent RANTES analogues either prevent CCR5-using human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in vivo or rapidly select for CXCR4-using variants. J Virol. 1999;73:3544–3550. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.3544-3550.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moulard M, Lortat-Jacob H, Mondor I, Roca G, Wyatt R, Sodroski J, Zhao L, Olson W, Kwong P D, Sattentau Q J. Selective interactions of polyanions with basic surfaces on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120. J Virol. 2000;74:1948–1960. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.4.1948-1960.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olinger G G, Saifuddin M, Spear G T. CD4-negative cells bind human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and efficiently transfer virus to T cells. J Virol. 2000;74:8550–8557. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.18.8550-8557.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oravecz T, Pall M, Wang J, Roderiquez G, Ditto M, Norcross M A. Regulation of anti-HIV-1 activity of RANTES by heparan sulfate proteoglycans. J Immunol. 1997;159:4587–4592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pierson T, Hoffman T L, Blankson J, Finzi D, Chadwick K, Margolick J B, Buck C, Siliciano J D, Doms R W, Siliciano R F. Characterization of chemokine receptor utilization of viruses in the latent reservoir for human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2000;74:7824–7833. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.17.7824-7833.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rich E A, Chen I S, Zack J A, Leonard M L, O'Brien W A. Increased susceptibility of differentiated mononuclear phagocytes to productive infection with human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) J Clin Investig. 1992;89:176–183. doi: 10.1172/JCI115559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roderiquez G, Oravecz T, Yanagishita M, Bou-Habib D C, Mostowski H, Norcross M A. Mediation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 binding by interaction of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans with the V3 region of envelope gp120-gp41. J Virol. 1995;69:2233–2239. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saphire A C, Bobardt M D, Gallay P A. Host cyclophilin A mediates HIV-1 attachment to target cells via heparans. EMBO J. 1999;18:6771–6785. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.23.6771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sattentau Q J, Moore J P. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 neutralization is determined by epitope exposure on the gp120 oligomer. J Exp Med. 1995;182:185–96. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.1.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sidtis J J, Price R W. Early HIV-1 infection and the AIDS dementia complex. Neurology. 1990;40:323–326. doi: 10.1212/wnl.40.2.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sonza S, Maerz A, Uren S, Violo A, Hunter S, Boyle W, Crowe S. Susceptibility of human monocytes to HIV type 1 infection in vitro is not dependent on their level of CD4 expression. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1995;7:769–776. doi: 10.1089/aid.1995.11.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steinfeld R, Van Den Berghe H, David G. Stimulation of fibroblast growth factor receptor-1 occupancy and signaling by cell surface-associated syndecans and glypican. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:405–416. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.2.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ugolini S, Mondor I, Parren P W, Burton D R, Tilley S A, Klasse P J, Sattentau Q J. Inhibition of virus attachment to CD4+ target cells is a major mechanism of T cell line-adapted HIV-1 neutralization. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1287–1298. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.8.1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uhlin-Hansen L, Kolset S O. Cell density-dependent expression of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan incultured human monocytes. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:2526–2531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.von Schwedler U, Kornbluth R S, Trono D. The nuclear localization signal of the matrix protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 allows the establishment of infection in macrophages and quiescent T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6992–6996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.6992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wiley C A, Schrier R D, Nelson J A, Lampert P W, Oldstone M B. Cellular localization of human immunodeficiency virus infection within the brains of acquired immune deficiency syndrome patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:7089–7093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.18.7089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]