Abstract

The vacuolar protein sorting 35 (VPS35) gene located on chromosome 16 has recently emerged as a cause of late-onset familial Parkinson’s disease (PD) (PARK17). The gene encodes a 796-residue protein nearly ubiquitously expressed in human tissues. The protein localizes on endosomes where it assembles with other peripheral membrane proteins to form the retromer complex. How VPS35 mutations induce dopaminergic neuron degeneration in humans is still unclear. Because the retromer complex recycles the receptors that mediate the transport of hydrolase to lysosome, it has been suggested that VPS35 mutations lead to impaired lysosomal and autophagy function. Recent studies also demonstrated that VPS35 and the retromer complex influence mitochondrial homeostasis, suggesting that VPS35 mutations elicit mitochondrial dysfunction. More recent studies have identified a key role of VPS35 in neurotransmission, whilst others reported a functional interaction between VPS35 and other genes associated with familial PD, including α-SYNUCLEIN-PARKIN–LRRK2. Here, we review the biological role of VPS35 protein, the VPS35 mutations identified in human PD patients, and the potential molecular mechanism by which VPS35 mutations can induce progressive neurodegeneration in PD.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, PARK17, VPS35, Retromer complex

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by cardinal motor features: bradykinesia, rest tremor, rigidity, and gait disorder (Obeso et al. 2017). These motor symptoms stem from the progressive dysfunction and degeneration of dopaminergic (DA) neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) and the downstream loss of DA inputs to the striatum. Post-mortem studies have also shown that other peripheral and central nervous pathways and transmitter systems (serotonin, noradrenaline, and acetylcholine) are affected in PD, albeit at varying degrees (Dickson et al. 2009; Schapira et al. 2017). This explains the variety of non-motor PD symptoms, including neuropsychiatric symptoms, autonomic dysfunction, and disorders of sleep and wakefulness (Pont-Sunyer et al. 2015).

Most cases of PD have a multifactorial aetiology, likely the result of harmful environmental and genetic factors (Borrageiro et al. 2018; Marras et al. 2019; Pang et al. 2019), but in a minority of cases (~ 5 to 10%) the disease arises from well-defined mutations in genes causative for the autosomal dominant or the recessive form of PD (Deng et al. 2018; Lunati et al. 2018). The vacuolar protein sorting 35 (VPS35) gene has recently emerged as a cause of late-onset familial PD (Vilariño-Güell et al. 2011; Zimprich et al. 2011; Chen et al. 2017). Albeit rare, mutations in the VPS35 gene are certainly associated with the development of PD (Klein et al. 2018) (see Sect. 3). Studies on the gene’s protein products have revealed pathogenic pathways relevant for development of the disease (see Sect. 5). These findings increase our knowledge of the pathogenic mechanisms underlying this rare form of PD and further our understanding of the mechanisms of DA neuronal dysfunction/degeneration/survival in other more frequent forms of PD.

VPS35 Structure and Localization

The VPS35 gene was first identified in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by a study that investigated the genes responsible for the assembly of lysosome-like vacuoles and the sorting of vacuolar proteins (Paravicini et al. 1992). The newly identified yeast gene encoding a protein of 936 aminoacids was named Vps35p. The study showed that Vps35p mutant yeast cells contained morphologically normal vacuoles but exhibited severe defects in the localization of carboxypeptidase Y, a soluble vacuolar hydrolase. These data indicated that VPS35 mutant cells were competent for vacuole assembly and that the protein encoded by the VPS35 gene was needed for sorting a subset of vacuolar proteins. Experiments on subcellular fractionation disclosed that the Vps35p assembles with four other peripheral membrane proteins (Vps29p, Vps26p, Vps5p, and Vps17p) to form a multimeric complex that localizes to the cytosolic face of the prevacuolar compartment and vesicles. Experimental data suggested that this complex has a key role in retrograde transport from the endosome to the Golgi; accordingly, it was named the retromer complex (Seaman et al. 1998).

BLAST searches comparing sequences of Vps35 to the GenBank database and a database of human expressed sequence tags (ESTs) revealed that yeast Vps35p is highly homologous to a protein found in the human genome (Seaman et al. 1997). The human homologue of yeast Vps35p (hVPS35) is a 796-residue protein encoded by a gene located on chromosome 16. Expression studies in human tissues showed that hVPS35 is almost ubiquitously expressed. Expression levels vary amongst tissues: higher in the brain, heart, testis, ovary, small intestine, spleen, skeletal muscle, and placenta, moderate in the pancreas, thymus, prostate, and colon, and lower in the lung, liver, kidney, and peripheral blood leukocytes (Haft et al. 2000; Zhang et al. 2000).

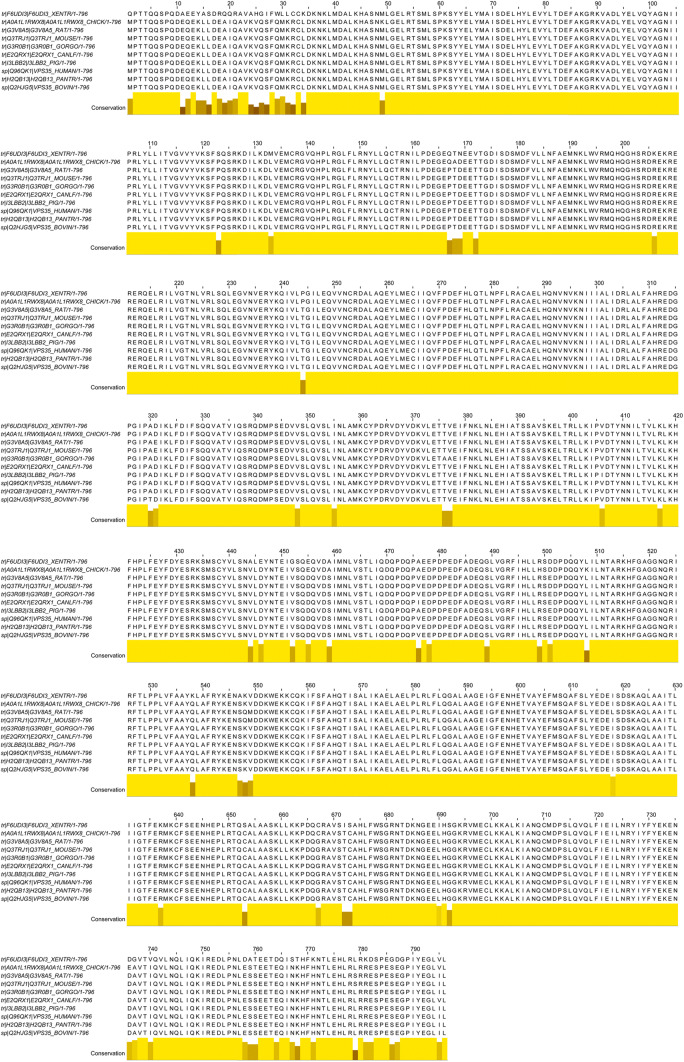

Protein sequence alignment of the S. cerevisiae Vps35p with the hVPS35 showed that it has 29% identity and 61% similarity (Edgar and Polak 2000). hVPS35 showed 99.4% identity to mouse and rat protein VPS35 (Zhang et al. 2000), 92.7% to Xenopus VPS35, and 99.5–100% to VPS35 protein of non-human primates. Figure 1a presents a multiple sequence alignment. This high rate of conservation suggests an important biological function of this protein.

Fig. 1.

Orthologous sequence alignment of the VPS35 protein. Orthologous sequences were obtained from Ensembl, and aligned using ClustalOmega. XENTR is sequence from Xenopus tropicalis, CHICK from Gallus gallus, RAT from Rattus norvegicus, MOUSE from Mus musculus, GORGO from Gorilla gorilla, CANLF from Canis lupus familiaris, PIG from Sus scrofa, HUMAN from Homo sapiens, PANTR from Pan troglodytes

Secondary structure predictions and sequence analyses have strongly suggested that the VPS35 protein adopts an α-helical solenoid structure containing 17 HEAT-like helical repeats (34 α-helices in total) (Hierro et al. 2007). Just as happens in yeast, so, too, in mammalian cells hVPS35 assembles in a 150-kDa 1:1:1 heterotrimer with two other peripheral membrane proteins (VPS26 and VPS29) to form the core of the mammalian retromer complex (Hierro et al. 2007). Vps35 forms the central platform for binding Vps26 at its N-terminus and Vps29 at its C-terminus (Lucas et al. 2016). X-ray crystallography, small-angle X-ray scattering, biochemistry, and cellular analyses showed that the core of the mammalian retromer complex interacts with an array of membrane-associated and cytosolic proteins. Key retromer partners are sorting nexin-1 (SNX1), sorting nexin-2 (SNX2), sorting nexin-5 (SNX5), and sorting nexin-6 (SNX6). SNX1/SNX2 and SNX5/SNX6 are the human homologues of Vps5p and Vps17p, respectively. These proteins are characterized by having phospholipid-binding domains (PX domain phox homology (PX) and bin/amphiphysin/rvs (BAR) domains) (Teasdale and Collins 2012). Retromer also interacts with many other accessory proteins; its role is to regulate membrane recruitment, cargo selectivity, and retromer trafficking. The retromer complex is localized mainly in the endosomal compartments. Its recruitment to endosomes is mediated by small GTPase Rab5 and Rab7, which act in concert to regulate the association with endosomes (Rojas et al. 2008; Seaman et al. 2009). Rab7 interacts directly with N-terminal conserved regions in Vps35, and the Rab7 association with Vps35 is obligatory for endosomal recruitment of the core retromer complex (Priya et al. 2015). Together with accessory proteins, the retromer complex core forms a coat on membrane tubules and regulates cellular localization (retrograde transport to the trans-Golgi network [TGN] and recycling to the plasma membrane) of hundreds of transmembrane proteins in many tissues. For example, cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor (CI-MPR) and β-2 adrenergic receptor (B2AR) are classical retromer cargoes that are trafficked to different cellular locations. CI-MPR is trafficked from endosome-to-Golgi (see Sect. 5.1), whereas β2AR is recycled from intracellular membranes to the plasma membrane (Temkin et al. 2011; Varandas et al. 2016). Many other retromer cargoes have been identified, such as the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2), an immunomodulatory receptor preferentially expressed in the microglia of the central nervous system (CNS) (Yin et al. 2016), the parathyroid hormone receptor PTH1R, a G protein-coupled receptor expressed in osteoblasts (Sims 2016), and many others (Seaman 2012; Li et al. 2016).

Whilst many retromer cargoes in many cellular types have been identified, how the retromer functions exactly in tissues is only partially known. Given its ubiquitous expression, it probably plays a key role in the development and maintenance of various cell types in the CNS and peripheral tissues. For example, the role of retromer in adipogenesis and modulating pathogen growth in tissues has been discovered recently (Yang et al. 2016; Elwell and Engel 2018). The homozygous deletion of VPS35 causes early lethality during early embryonic development in mice (Wen et al. 2011), further underscoring the importance of VPS35 and the retromer complex in the development and homeostasis of many tissues.

VPS35 Mutations in PD Patients

Two independent studies published in 2011 reported a missense mutation in the VPS35 gene as a cause of late-onset PD (Vilariño-Güell et al. 2011; Zimprich et al. 2011). By means of whole exome sequencing (WES) technology, the authors found the heterozygous mutation c.18589G > A (p.Asp620Asn) in all affected family members and in a few unaffected members, which suggested autosomal dominant heritability of the disease with incomplete penetrance. The subsequent screening of all 17 exons of the VPS35 gene in other PD families revealed six further missense variants whose pathogenicity has not yet been confirmed (Vilariño-Güell et al. 2011; Zimprich et al. 2011; Chen et al. 2017). To date, five studies have identified the p.Asp620Asn mutation in patients with sporadic or familial PD (Ando et al. 2012; Kumar et al. 2012; Sharma et al. 2012; Sheerin et al. 2012; Chen et al. 2017); however, since other genetic studies involving PD patient cohorts from diverse countries did not find the p.Asp620Asn variant, VPS35 mutations may not be a common cause of familial PD (Verstraeten et al. 2012; Zhang et al. 2012; Deng et al. 2012; Guella et al. 2012; Guo et al. 2012; Nuytemans et al. 2013; Sudhaman et al. 2013; Blanckenberg et al. 2014; Gagliardi et al. 2014; Kalinderi et al. 2015; Török et al. 2016; Chen et al. 2017). The frequency of the p.Asp620Asn variant in the general population has not yet been determined exactly (Deutschländer et al. 2019). In addition to the p.Asp620Asn mutation, 13 other missense variants in the VPS35 gene have been described in at least one patient with PD (Vilariño-Güell et al. 2011; Zimprich et al. 2011; Ando et al. 2012; Sharma et al. 2012; Verstraeten et al. 2012; Nuytemans et al. 2013), but their pathological role remains uncertain. Table 1 presents the data for the missense variants identified to date.

Table 1.

VPS35 mutations identified in PD patients

| DNA change | Aminoacid change | Exon | PD patients (familial or sporadic) | Geographical origin | Reference | Pathogenetic role |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | 15 | 1 family (11 affected and 4 not affected) and none in control cases | Austria | Vilariño-Güell et al. (2011) | Yes |

| c.946C > T | p.Pro316Ser | 9 | 1 family (2 affected/1 not affected) and 1 control case | U.S.A | Vilariño-Güell et al. (2011) | Uncertain significance |

| c.2210C > T | p.Ala737Val | 16 | 1 proband and 1 control cases | Tunisia | Vilariño-Güell et al. (2011) | Uncertain significance |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | 15 | 3 Families (15 affected and 3 not affected) and none in control cases | Austria | Zimprich et al. (2011) | Yes |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | 15 | 6 probands | Austria and Germany | Zimprich et al. (2011) | Yes |

| c.1570C > T | p.Arg524Trp | 13 | 1 proband | Austria and Germany | Zimprich et al. (2011) | Uncertain significance |

| c.723T > G | p.Ile241Met | 7 | 1 proband | Austria and Germany | Zimprich et al. (2011) | Uncertain significance |

| c.2320C > A | p.Leu774Met | 17 | 2 probands | Austria and Germany | Zimprich et al. (2011) | Uncertain significance |

| c.171G > A | p.Met57Ile | 3 | 1 proband | Austria and Germany | Zimprich et al. (2011) | Uncertain significance |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | 15 | 1 family (3 affected) | / | Sheerin et al. (2012) | Yes |

| c.1679 T > C | p.Ile560Thr | 14 | 1 proband | Flanders (Belgium) | Verstraeten et al. (2012) | Uncertain significance |

| c.1796A > G | p.His599Arg | 14 | 1 proband | Flanders (Belgium) | Verstraeten et al. (2012) | Uncertain significance |

| c.1819A > G | p.Met607Val | 14 | 1 proband | Flanders (Belgium) | Verstraeten et al. (2012) | Uncertain significance |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | 15 | 1 family (2 affected/3 not affected) | Germany | Kumar et al. (2012) | Yes |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | 15 | 4 probands and none in control cases | Japan | Ando et al. (2012) | Yes |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | 15 | 7 probands and none in control cases | Multicentric study | Sharma et al. (2012) | Yes |

| c.2320C > A | p.Leu774Met | 17 | 6 probands and 1 control case | Multicentric study | Sharma et al. (2012) | Uncertain significance |

| c.151G > A | p.Gly51Ser | 3 | 3 probands and 2 control cases | Multicentric study | Sharma et al. (2012) | Uncertain significance |

| c.946C > T | p.Pro316Ser | 9 | 1 proband and none in control cases | U.S.A. (white non-Hispanic/Latino) | Nuytemans et al. (2013) | Uncertain significance |

| c.1520A > T | p.Tyr507Phe | 12 | 1 proband and none in control cases | U.S.A. (white non-Hispanic/Latino) | Nuytemans et al. (2013) | Uncertain significance |

| c.2359G > A | p.Glu787Lys | 17 | 1 proband and none in control cases | U.S.A. (white non-Hispanic/Latino) | Nuytemans et al. (2013) | Uncertain significance |

| c.1145A > G | p.Lys382Arg | 10 | 1 proband | Spain | Gorostidi et al. (2016) | Uncertain significance |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | 15 | 1 proband | Taiwan | Chen et al. (2017) | Yes |

The table shows the VPS35 mutations identified in the papers cited

Regarding clinical characteristics, the motor and non-motor features in patients with mutated VPS35 are indistinguishable from idiopathic PD. Age at onset is variable and earlier than in idiopathic PD in some cases. Table 2 presents the clinical characteristics of patients carrying the VPS35 missense variants identified so far (Wider et al. 2008; Zimprich et al. 2011; Vilariño-Güell et al. 2011; Ando et al. 2012; Kumar et al. 2012; Sharma et al. 2012; Sheerin et al. 2012; Verstraeten et al. 2012; Nuytemans et al. 2013; Gorostidi et al. 2016; Chen et al. 2017). In brief, mutations in the VPS35 gene seem to be a rare cause of PD, and the pathogenicity of the p.Asp620Asn mutation is certain. Functional studies are needed to establish the pathogenicity of other variants and their potential role in neurodegeneration.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of PD patients carrying VPS35 variants

| DNA change | Aminoacid change | dbSNP | Exon | PD patients (familial or sporadic) | Geographical origin | AAO | Duration | Clinical features | References | Pathogenetic role | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c.2210C > T | p.Ala737Val | rs749516404 | 16 | 1 Proband | Tunisia | 60 | NA | NA | Vilariño-Güell et al. (2011) | Uncertain significance | 1 Tunisian proband and 1 Tunisian control |

| c.946C > T | p.Pro316Ser | rs770029606 | 9 | Yes family history | US-2 | 54 | NA | Cognitive deficits were observed in two family members with parkinsonism and VPS35 p.Pro316Ser mutations | Vilariño-Güell et al. (2011) | Uncertain significance | 1 family (2 affected / 1 not affected) and 1 control case |

| c.946C > T | p.Pro316Ser | rs770029606 | 9 | Yes family history | US-2 | 52 | NA | Hand tremor and micrographia, not yet fulfilling clinical criteria for PD | Vilariño-Güell et al. (2011) | Uncertain significance | 1 family (2 affected / 1 not affected) and 1 control case |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | IV-4, yes family History | CH (Switzerland) | 54 | 8 | Cramps; Left-leg resting tremor; Bradykinesia; Good response to levodopa, no motor fluctuations | Wider et al. (2008) and Vilariño-Güell et al. (2011) | Pathogenic | 1 family (11 affected and 4 non affected) and none in control cases |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | IV-10, yes family history | CH (Switzerland) | 47 | 31 | Resting tremor and cramps (first symptom); Bradykinesia; Rigidity; Axial signs; Good response to levodopa with motor fluctuations after 10 years | Wider et al. (2008) and Vilariño-Güell et al. (2011) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | IV-17,yes family history | CH (Switzerland) | 54 | 6 | Resting tremor; Axial signs; Rigidity; Good response to DA | Wider et al. (2008) and Vilariño-Güell et al. (2011) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | IV-15-yes family history | CH (Switzerland) | 49 | 13 | Left-hand tremor at age 49; Bradykinesia; Rigidity; Axial signs; Good response to levodopa with motor fluctuations after 5 years. After 10 years, severe dyskinesia and painful off dystonia | Wider et al. (2008) and Vilariño-Güell et al. (2011) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | IV-12, yes family history | CH (Switzerland) | 46 | 8 | Resting tremor of the left side, more pronounced in the leg; Bradykinesia; Rigidity; Good response to levodopa with motor fluctuations and peak-dose dystonia after 3 years | Wider et al. (2008) and Vilariño-Güell et al. (2011) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | III-4, yes family history | CH (Switzerland) | 64 | 13 | Resting tremor (first symptom); Bradykinesia; Rigidity; Axial signs; Good response to levodopa with motor fluctuations | Wider et al. (2008) and Vilariño-Güell et al. (2011) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | III-7, yes family history | CH (Switzerland) | 48 | 20 | Resting Tremor; Bradykinesia; Rigidity; Axial signs; Levodopa not tolerated because of dizziness and nausea | Wider et al. (2008) and Vilariño-Güell et al. (2011) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | III-9, yes family history | CH (Switzerland) | 58 | 29 | Asymmetric resting tremor (Tremor→ First symptom); Rigidity; Bradykinesia; Axial signs; Good response to levodopa with motor fluctuations | Wider et al. (2008) and Vilariño-Güell et al. (2011) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | III-11, yes family history | CH (Switzerland) | 60 | 17 | Resting tremor (first symptom); Bradykinesia; Rigidity; Axial signs; Good response to levodopa with motor fluctuations | Wider et al. (2008) and Vilariño-Güell et al. (2011) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | III-13, yes family history | CH (Switzerland) | 42 | 27 | Upper limb resting tremor and bradykinesia (first symptom); Rigidity; Axial signs; Good response to levodopa with motor fluctuations after 5 years | Wider et al. (2008) and Vilariño-Güell et al. (2011) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | II-4, yes family history | CH (Switzerland) | 50 | 20 | Progressive asymmetric tremor-predominant parkinsonism (Tremor– > First Symptom); Response to levodopa: patient died before levodopa became available | Wider et al. (2008) and Vilariño-Güell et al. (2011) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | Yes family history | US | 55 | NA | Tremor dominant PD; good response to levodopa | Vilariño-Güell et al. (2011) and Chen et al. (2017) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | Yes family history | US | 64 | NA | Tremor dominant PD; good response to levodopa | Vilariño-Güell et al. (2011) and Chen et al. (2017) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | No family history | Yemenite-2 | 54 | NA | Tremor dominant PD; good response to levodopa | Vilariño-Güell et al. (2011) and Chen et al. (2017) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | Yes family history | Tunisia | NA | NA | Tremor dominant PD; good response to levodopa | Vilariño-Güell et al. (2011) and Chen et al. (2017) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | Yes family history | Tunisia | 42 | NA | Tremor dominant PD; good response to levodopa | Vilariño-Güell et al. (2011) and Chen et al. (2017) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | Yes family history | Tunisia | 41 | NA | Tremor dominant PD; good response to levodopa | Vilariño-Güell et al. (2011) and Chen et al. (2017) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | Yes family history | Yemenite-1 | 40 | NA | Tremor dominant PD; Good response to levodopa | Vilariño-Güell et al. (2011) and Chen et al. (2017) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | Yes family history | Yemenite-1 | 43 | NA | Tremor dominant PD; Good response to levodopa | Vilariño-Güell et al. (2011) and Chen et al. (2017) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | Yes family history | Yemenite-1 | 47 | NA | Tremor dominant PD; Good response to levodopa | Vilariño-Güell et al. (2011) and Chen et al. (2017) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | Yes family history (family A) | Austria | 48 | 7 | Bradykinesia (first symptom); Rigidity; Postural instability; Axial signs; Good response to levodopa/DA | Zimprich et al. (2011) | Pathogenic | 3 families A,B,C (15 affected and 3 non affected) and none in control cases |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | Yes family history (family A) | Austria | 40 | 5 | Bradykinesia (first symptom); Rigidity; Resting tremor; Postural instability; Good response to levodopa/DA | Zimprich et al. (2011) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | Yes family history (family A) | Austria | 46 | 7 | Bradykinesia; Rigidity; Postural instability (first symptom); Good response to levodopa/DA | Zimprich et al. (2011) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | Yes family history (family A) | Austria | 68 | 16 | Bradykinesia; Rigidity; Resting tremor; Postural instability (first symptom); Good response to levodopa/DA | Zimprich et al. (2011) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | Yes family history (family A) | Austria | 49 | 4 | Bradykinesia; Rigidity; Resting tremor (first symptom); Good response to levodopa/DA | Zimprich et al. (2011) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | Yes family history (family A) | Austria | 64 | 3 | Bradykinesia; Rigidity; Resting tremor; Postural instability (first symptom); Good response to levodopa/DA | Zimprich et al. (2011) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | Yes family history (family A) | Austria | 63 | 1 | Bradykinesia; Resting tremor (first symptom); Action tremor since childhood; Good response to levodopa/DA | Zimprich et al. (2011) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | Yes family history (family B) | Austria | 61 | 15 | Bradykinesia; Rigidity; Resting tremor (first symptom); Postural instability; Good response to levodopa/DA; Motor fluctuations; dyskinesia | Zimprich et al. (2011) | Pathogenic | 3 families A,B,C (15 affected and 3 non affected) and none in control cases |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | Yes family history (family B) | Austria | 56 | 8 | Bradykinesia; Rigidity; Resting tremor (first symptom); Postural instability; Good response to L-Dopa/DA with motor fluctuations and dyskinesia | Zimprich et al. (2011) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | Yes family history (family B) | Austria | 46 | 0.5 | Resting tremor (first symptom); L-Dopa/DA: untreated; Depression; Action tremor | Zimprich et al. (2011) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | Yes family history (family B) | Austria | 51 | 5 | Bradykinesia (first symptom); Rigidity; Resting tremor; Good response to levodopa/DA; Fluctuations | Zimprich et al. (2011) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | Yes family history (family C) | Austria | 61 | 5 | Bradykinesia; Rigidity; Resting tremor (first symptom); Good response to levodopa/DA; Dyskinesia | Zimprich et al. (2011) | Pathogenic | 3 families A,B,C (15 affected and 3 non affected) and none in control cases |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | Yes family history (family C) | Austria | 46 | 12 | Bradykinesia; Rigidity; Resting tremor (first symptom); Good response to levodopa/DA | Zimprich et al. (2011) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | Yes family history (family C) | Austria | 53 | 9 | Bradykinesia (first symptom); Rigidity; Good response to levodopa/DA; Dyskinesia | Zimprich et al. (2011) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | Yes family history (family C) | Austria | 43 | 10 | Bradykinesia (first symptom); Rigidity; Resting tremor; Postural instability; Good response to levodopa/DA; dyskinesia | Zimprich et al. (2011) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1570C > T | p.Arg524Trp | rs184277092 | 13 | Patient 211; no family history | Austria and Germany | 37 | 9 | Micrographia (first symptom), Bradykinesia; Rigidity; Resting tremor; Mild action tremor since youth; Good response to levodopa; DBS for fluctuations and dyskinesia | Zimprich et al. (2011) | Uncertain significance | |

| c.723T > G | p.Ile241Met | rs192783364 | 7 | Patients 524; no family history | Austria and Germany | 51 | 7 | Resting tremor (first symptom); Bradykinesia; Rigidity; Marked postural tremor; Good response to levodopa/DA | Zimprich et al. (2011) | Uncertain significance | |

| c.723T > G | p.Ile241Met | rs192783364 | 7 | Patients 243; no family history | Austria and Germany | 73 | 9 | Resting tremor (first symptom); Bradykinesia; Rigidity; Postural instability; Good response to levodopa/DA; Dyskinesia | Zimprich et al. (2011) | Uncertain significance | |

| c.2320C > A | p.Leu774Met | rs192419029 | 17 | Patient 806; no family history | Austria and Germany | 72 | 2 | Postural tremor (first symptom); Bradykinesia; Resting tremor; Postural instability; Good response to levodopa/DA; Hyposmia; Pathological crying | Zimprich et al. (2011) | Uncertain significance | |

| c.171G > A | p.Met57Ile | rs183554824 | 3 | Patient 90/05; no family history | Austria and Germany | 62 | 13 | Resting tremor (first symptom); Bradykinesia; Rigidity; Postural instability; Good response to levodopa/DA; Dementia; Hyposmia; Depression | Zimprich et al. (2011) | Uncertain significance | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | Yes family history | UK | 40 | NA | Rigidity in the left arm (first symptom); Asymmetric bradykinesia; Mild resting tremor; Postural instability; Good response to levodopa with dyskinesia after 9 years | Sheerin et al. (2012) | Pathogenic | 1 family (3 affected) |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | Yes family history | UK | 47 | NA | Left-leg rigidity; Bradykinesia; Postural instability; Micrographia (first symptom); No resting tremor; Good response to levodopa/DA; Dyskinesia after 10 years; Successfully treated with DBS | Sheerin et al. (2012) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | Yes family history | UK | 52 | NA | Cramps in the left foot and tripping when walking (first symptoms); Asymmetric leg tremor; Micrographia; Freezing; Good response to levodopa | Sheerin et al. (2012) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1679 T > C | p.Ile560Thr | rs760128592 | 14 | Patient d2542; no family history | Flanders-Belgian | 68 | 7 | Bradykinesia; Rigidity; Postural Instability | Verstraeten et al. (2012) | Uncertain significance | |

| c.1796A > G | p.His599Arg | rs1434487321 | 14 | Patient d2700; no family history | Flanders-Belgian | 54 | 18 | Resting Tremor; Bradykinesia; Rigidity | Verstraeten et al. (2012) | Uncertain significance | |

| c.1819A > G | p.Met607Val | rs1555523076 | 14 | Patient d12436; yes family history | Flanders-Belgian | 76 | 4 | Bradykinesia; Rigidity; Postural Instability | Verstraeten et al. (2012) | Uncertain significance | |

| c.1145A > G | p.Lys382Arg | rs116254156 | 10 | 1 proband | Spain | NA | NA | NA | Gorostidi et al. (2016) | Likely Benign (Jun 14,2016) | |

| c.946C > T | p.Pro316Ser | rs770029606 | 9 | Sporadic patient | US (white, non-Hispanic/Latino) | 26 | NA | NA | Nuytemans et al. (2013) | Uncertain significance | 1 proband and none in control cases |

| c.1520A > T | p.Tyr507Phe | rs1555465749 | 12 | 1 proband | US (white, non-Hispanic/Latino) | 29 | NA | NA | Nuytemans et al. (2013) | Uncertain significance | 1 proband and none in control cases |

| c.2359G > A | p.Glu787Lys | rs777050595 | 17 | 1 proband | US (white, non-Hispanic/Latino) | 60 | NA | NA | Nuytemans et al. (2013) | Uncertain significance | 1 proband and none in control cases |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | Yes family history | German | 45 | NA | Rigidity; Resting tremor; Bradykinesia; Postural instability; Good response to levodopa; Restless legs syndrome; Hypersexuality and pathological gambling; Motor fluctuations; Hyperhidrosis; Peak-dose dyskinesia; Freezing; Memory impairment; Hyposmia | Kumar et al. (2012) | Pathogenic | 1 family (2 affected / 3 non affected) |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | Yes family history | German | 60 s | NA | Onset with lower limb tremor; Progressive parkinsonism treated with deep brain stimulation, which was complicated by dysarthria | Kumar et al. (2012) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | Patient AII-11; yes family history | Japan | 62 | 15 | Resting tremor; Bradykinesia; Rigidity; Asymmetric onset; Gait Disturbance; Postural instability; Good response to levodopa; Motor fluctuations; Dyskinesia; Orthostatic hypotension; Urinary incontinence; Dementia | Ando et al. (2012) | Pathogenic | 1 proband and none in control cases |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | Patient BIII-8; yes family history | Japan | 55 | 2 | Resting tremor; Bradykinesia; Rigidity; Asymmetric onset; Good response to levodopa | Ando et al. (2012) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | Patient CII-3; yes family history | Japan | 34 | 7 | Resting tremor; Bradykinesia; Rigidity; Asymmetric onset; Good response to levodopa/DA; Motor fluctuations; Levodopa induced dyskinesia | Ando et al. (2012) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | Patient D; no family history | Japan | 42 | 21 | Resting tremor; Bradykinesia; Rigidity; Gait Disturbance; Postural instability; Asymmetry at onset: + ; Good response to levodopa; Motor fluctuations; Dyskinesia | Ando et al. (2012) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | P1; no family history | Caucasian | 59 | NA | Bradykinesia in the left arm (first symptom); Rigidity; Resting tremor; Postura instability; Good response to levodopa. Non-motor symptoms: negative | Sharma et al. (2012) | Pathogenic | 7 probands and none in control cases |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | P6; yes family history | Caucasian | 37 | NA | Bradykinesia; Rigidity; Postural instability; Gait dysfunction in absence of tremor: typical postural instability gait disorder phenotype. Good response to levodopa. Non-motor symptoms: negative | Sharma et al. (2012) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | P7; yes family history | Caucasian | 59 | NA | Bradykinesia; Rigidity; Tremor; Postural instability; Good response to levodopa. Non-motor symptoms: negative | Sharma et al. (2012) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | P8; yes family history | Caucasian | 55 | NA | Left-hand kinetic tremor; Bilateral lower limb resting tremor (first symptom); Bradykinesia; Rigidity; Postural instability; Good response to levodopa; Non-motor symptoms: not present | Sharma et al. (2012) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | P9; yes family history | Caucasian | 66 | NA | Left lower limb rest (first symptom); Bradykinesia; Rigidity; Tremor; Postural instability; Good response to levodopa. Non-motor symptoms: not present | Sharma et al. (2012) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | P15 (p.Asp620Asn, p.Leu774Met); no family history | Asian | 52 | NA | Asymmetric bradykinesia and rigidity; Mild resting tremor of the left leg; Good response to levodopa; Non-motor symptoms: not present | Sharma et al. (2012) | Pathogenic | |

| c.1858G > A | p.Asp620Asn | rs188286943 | 15 | P18; yes family history | Asian | 43 | NA | Bradykinesia; Rigidity; Tremor; Postural instability; Good response to levodopa; Mild cognitive impairment | Sharma et al. (2012) | Pathogenic | |

| c.2320C > A | p.Leu774Met | rs192419029 | 17 | P10; yes family history | Caucasian | 41 | NA | Asymmetric lower limb resting tremor (first symptom); Bradykinesia; Rigidity; Postural instability; Good response to levodopa with early motor fluctuations and dyskinesia | Sharma et al. (2012) | Uncertain significance | 6 probands and 1 control case |

| c.2320C > A | p.Leu774Met | rs192419029 | 17 | P11; yes family history | Caucasian | 65 | NA | Left upper limb bradykinesia; Rigidity; Tremor; Postural instability; Good response to levodopa; Motor fluctuations and dyskinesia; Dream enactment behaviour; Mild cognitive impairment after 15 years | Sharma et al. (2012) | Uncertain significance | |

| c.2320C > A | p.Leu774Met | rs192419029 | 17 | P12; yes family history | Caucasian | 65 | NA | Bradykinesia; Rigidity; Tremor; Postural instability; Axial signs; Good response to levodopa | Sharma et al. (2012) | Uncertain significance | |

| c.2320C > A | p.Leu774Met | rs192419029 | 17 | P14; yes family history | Caucasian | 44 | NA | Right-hand tremor; Asymmetrical bradykinesia and rigidity; Postural instability; Good response to levodopa; Motor fluctuations and dyskinesia after 15 years; Autonomic dysfunction | Sharma et al. (2012) | Uncertain significance | |

| c.2320C > A | p.Leu774Met | rs192419029 | 17 | P15 (p.Asp620Asn, p.Leu774Met); no family history | Asian | 52 | NA | Generalized bradykinesia; Mild asymmetric rigidity and resting tremor; Good response to levodopa. Non-motor symptoms: not present | Sharma et al. (2012) | Uncertain significance | |

| c.2320C > A | p.Leu774Met | rs192419029 | 17 | P17; No family history | Asian | 75 | NA | Dysarthria; Bradykinesia; Asymmetric rigidity; Asymmetric upper limb postural tremor; Good response to levodopa; Autonomic dysfunction | Sharma et al. (2012) | Uncertain significance | |

| c.151G > A | p.Gly51Ser | rs193077277 | 3 | P3; no family history | Caucasian | NA | NA | Bradykinesia; Rigidity; Tremor; Postural instability; Good response to levodopa; Dementia; Mild visual hallucinations | Sharma et al. (2012) | Uncertain significance | 3 probands and 2 control cases |

| c.151G > A | p.Gly51Ser | rs193077277 | 3 | P4; no family history | Caucasian | 55 | NA | Right-sided bradykinesia and tremor (first symptoms); Rigidity; Postural instability; Good response to levodopa; Progressive cognitive decline and severe psychiatric symptoms | Sharma et al. (2012) | Uncertain significance | |

| c.151G > A | p.Gly51Ser | rs193077277 | 3 | P5; no family history | Caucasian | 49 | NA | Bradykinesia and left-sided resting tremor; Rigidity; Postural instability; Good response to levodopa; Motor fluctuations; Severe psychiatric symptoms | Sharma et al. (2012) | Uncertain significance |

The table presents the clinical features of the PD patients carrying VPS35 variants

VPS35 and Dopaminergic Neuron Degeneration in Murine and Human Models

Because mice knockout for VPS35 die early during embryonic development (Wen et al. 2011), this model cannot be used to investigate the neurodegeneration associated with a loss of VPS35 function. Tsika et al. explored the pathogenic effects of VPS35 mutations in vivo by developing a viral model of VPS35-associated PD. Adeno-associated viral vectors expressing hVPS35, WT or D620N were delivered to the substantia nigra of adult rats by stereotactic injection. The expression of D620N VPS35 produced a 32% loss of SNc DA neurons; however, the expression of WT VPS35 also induced a 25% loss of DA neurons. The authors suggested that this result supports a gain-of-function mechanism for the D620N mutation (Tsika et al. 2014).

Tang et al. created two different mouse models: one was VPS35 heterozygote (VPS35+/-) and the other had a specific deletion of the VPS35 gene in DA neurons (VPS35DAT-Cre) (Tang et al. 2015b). The VPS35+/- mice survived to adult age; at age 12 months they were noted to have a 20% loss of DA neurons in the SNc and an accumulation of α-synuclein (αSYN). At 2 months of age, the VPS35DAT-Cre mice showed a marked reduction in DA neurons at the SNc, a decrease in DA fibres in the striatum, and increased αSYN levels in the SNc. The authors suggested that VPS35-haploinsufficiency in DA neurons promotes PD pathogenesis (Tang et al. 2015b).

Three studies generated and characterized VPS35 knock-in (KI) mouse models bearing the D620N mutation (Ishizu et al. 2016; Cataldi et al. 2018; Chen et al. 2019). Ishizu et al. found a decrease in evoked striatal DA release in homozygous VPS35-D620N KI mice but did not disclose clear neurodegeneration in homozygous and heterozygous VPS35-D620N KI mice, even in those 70 weeks of age (Ishizu et al. 2016). Cataldi et al. analysed an independent VPS35-D620N KI model but found no neurodegeneration in mice at 3 months of age (21 weeks), as assessed by DA neuron count in the SNc and analyses of TH expression in the striatum (Cataldi et al. 2018); however, they did find changes in the levels of synaptic markers such as dopamine transporter (DAT) and vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2). This finding suggested early synaptic dysfunction in the dopaminergic system of VPS35 D620N KI mice (Cataldi et al. 2018). Another study further characterized the VPS35-D620N KI model (Chen et al. 2019). The authors found that the expression of D620N VPS35 had a modest impact on motor function even at advanced age; at 13 months of age, however, both the homozygous and the heterozygous VPS35-D620N mice exhibited a significant loss of DA neurons compared to the WT mice (Chen et al. 2019). This difference demonstrates that a heterozygous or homozygous D620N mutation is sufficient to reproduce progressive degeneration of the nigrostriatal pathway in a mouse model. Furthermore, the model confirmed the role of VPS35 in regulating DA neuron survival. The reasons for the discrepancy compared to the mouse model developed by Ishizu et al. (Ishizu et al. 2016) remain unclear.

Human models were developed by creating induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) from fibroblasts of VPS35 PD patients carrying the p.D620N mutation. The DA neurons were obtained after differentiation and compared to the DA neurons obtained from control subjects (Munsie et al. 2015). The study reported that the D620N neurons had increased levels of AMPAR subunit-GluA1, which suggested defective AMPAR trafficking (Munsie et al. 2015); however, no data were reported about the viability of these DA neurons. Future studies on iPSC-derived human DA neurons are warranted to understand whether this in vitro model recapitulates in vivo degeneration.

VPS35 Modulates the Function of Cellular Organelles

The Role of VPS35 in the Retromer Complex as a Regulator of Lysosome Function

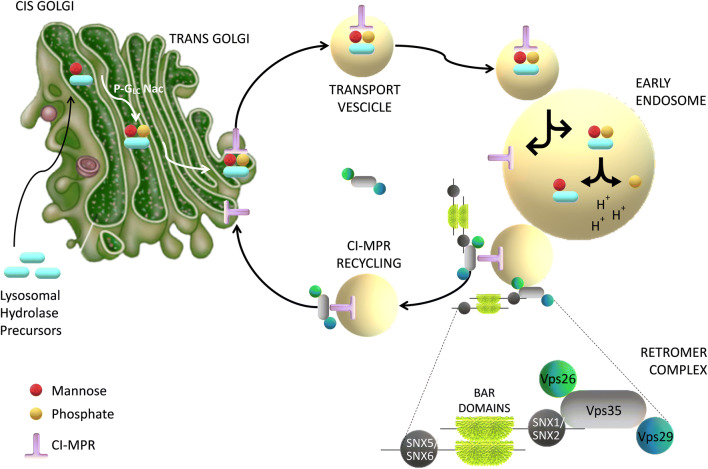

Lysosomes (and their equivalent structures known as vacuoles in yeast) are the degradative end points for both intracellular and exogenous cargo. Their catabolic function is accomplished by many proteases, lipases, nucleases, and other hydrolytic enzymes that break complex macromolecules down into their constituent building blocks (Lawrence and Zoncu 2019). In mammals, the sorting of lysosomal hydrolase precursors from the trans-Golgi network (TGN) to the pre-lysosomal compartment network endosomes is mediated by the CI-MPR. CI-MPR carries newly synthesized acid hydrolase precursors from the TGN to endosomes for eventual delivery to the lysosomes. After releasing the hydrolase precursors into the endosomal lumen, the unoccupied receptors have to return to the TGN for further rounds of sorting. The mammalian retromer complex participates in this retrieval pathway (Bonifacino and Hurley 2008). In detail, the hVPS35 subunit of retromer probably interacts with the cytosolic domain of the CI-MPR in an endosomal compartment (Arighi et al. 2004; Seaman 2005) and sequestrates the CI-MPR into recycling tubules, thus preventing their delivery to the vacuoles or lysosomes (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Diagram showing the role of VPS35 in retrieval of the mannose-6-phosphate receptor (CI-MPR) to the trans-Golgi network. VPS35, along with VPS26 and VPS29, are located on the endosomal membrane and recognize the cargo (transmembrane proteins) to be sorted. Retromer-associated proteins assist in membrane binding

Depletion of retromer by RNA interference in human cells prevents the retrieval of acid hydrolase receptors to the TGN and causes their missorting to the vacuole or lysosomes, where they are degraded. This mechanism increases lysosomal turnover of the CI-MPR, decreases cellular levels of lysosomal hydrolases, and causes lysosomes to swell (Arighi et al. 2004; Seaman 2005). Further studies showed that VPS35-deficient DA neurons or DA neurons expressing PD-linked VPS35 mutant D620N had impaired endosome-to-Golgi retrieval of lysosome-associated membrane glycoprotein 2a (Lamp2a) and accelerated degradation of Lamp2a (Tang et al. 2015a). Lamp2a is a receptor of chaperone-mediated autophagy crucial for αSYN degradation (Mak et al. 2010; Xilouri et al. 2013). The authors found a significant reduction of Lamp2a in the ventral midbrain of VPS35± and VPS35-D620N mice, but not in the striatum or the hippocampus, and a temporal and brain-regional association between the reduction in Lamp2a and the increase in αSYN. They also observed that expression of Lamp2a in VPS35-deficient DA neurons reduced αSYN levels, supporting the view that Lamp2a is a receptor of chaperone-mediated autophagy critical for αSYN degradation. Hence, these results suggest that, in addition to CI-MPR, Lamp2a is another cargo of VPS35/retromer in DA neurons and reveals a crucial pathway,VPS35-Lamp2a-αSYN, to prevent PD pathogenesis (Tang et al. 2015a).

A recent study reported that VPS35 also modulates the Golgi-network trafficking of iron by modifying the subcellular distribution of labile Fe(ii), which is defined as a protein-free or weakly protein-bound form of Fe(ii) ions that are able to induce oxidative damage through Fenton chemistry (Enami et al. 2014). In SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells, knockdown of hVPS35 decreased the basal level of labile Fe(ii) in the Golgi and induced lysosomal accumulation of labile Fe(ii). Coherently, hVPS35 knockdown also induced lysosomal accumulation of divalent metal transporter 1, a protein that acts as a primary transporter of Fe(ii) ions (Hirayama et al. 2019). Accumulation of divalent metal transporter 1 was also found in the SH-SY5Y expressing the mutant form VPS35-D620N (Kumar et al. 2012; Mohan and Mellick 2017).

PD-causing mutations in VPS35 probably also lead to a defect in autophagy, a degradative pathway by which the breakdown of cellular proteins releases the amino acids necessary for survival, particularly under starvation or stress conditions (Kroemer et al. 2010). Autophagy removes damaged mitochondria and intracellular pathogens (Birmingham et al. 2006) and mediates the clearance of intracytoplasmic aggregate-prone proteins (Ravikumar 2002; Webb et al. 2003; Ravikumar et al. 2004). Zavodszky et al. showed that the PD-associated mutation VPS35-D620N decreased the endosomal recruitment of the protein complex named Wiskott–Aldrich Syndrome Protein and SCAR Homolog (WASH). This is an actin-regulating complex that includes five proteins (FAM21, WASH1, strumpellin, CCDC53, and KIAA1033); it is recruited to endosomes by interacting with the retromer complex and it plays a role in endosomal sorting. VPS35 D620N exhibits a reduced association with WASH complex proteins, thus destabilizing the retromer–WASH complex interaction (McGough et al. 2014) and resulting in reduced endosomal localization of the WASH complex. Because WASH complex binding to retromer is necessary for autophagy, perturbation of WASH complex binding disrupts autophagy (Zavodszky et al. 2014).

Summarizing, loss of VPS35 function or expression of mutant VPS35 D620N has a profound impact on lysosome function and impairs autophagy. These mechanisms are a highly plausible contributor to neuronal death.

The Role of VPS35 in Mitochondria Function

Endogenous VPS35 was detected on mitochondria-derived vesicles (MDVs), organelles that transport cargo from the mitochondria to the peroxisomes (Neuspiel et al. 2008). In detail, VPS35 was found in the complex with the protein mitochondrial-anchored protein ligase (MAPL), a small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) E3 ligase that localizes on MDVs. The study also showed that the silencing of VPS35 leads to a significant reduction in the delivery of MAPL to peroxisomes, placing VPS35 and the retromer within a novel intracellular trafficking route that results in the formation of MDVs (Braschi et al. 2010). Another pathway by which VPS35 may modulate mitochondria function is by regulating mitochondria fusion and fission. Tang et al. found that VPS35 deficiency in neuronal cell lines, in DA neurons, and in brain tissues reduces the levels of mitochondrial MFN2, a GTPase embedded in the outer mitochondrial membrane that is essential for mitochondrial fusion. Coherently, the mitochondria of VPS35-depleted DA neurons were shorter and rounder than those in the control neurons, suggesting that VPS35 depletion induces mitochondrial fragmentation. The mitochondrial fragmentation in VPS35-depleted neurons was mitigated by the expression of the VPS35 wild type, but not by the PD-linked mutant VPS35-D620N (Tang et al. 2015b). The authors went on to investigate the mechanism by which VPS35 may regulate MFN2 protein levels and mitochondrial fusion dynamics. They found that VPS35 regulates the trafficking and degradation of the E3 ubiquitin ligase MUL1, thus suppressing MUL1-mediated MFN2 degradation (Tang et al. 2015b). These data are consistent with observations that VPS35 interacts with MUL1/ MAPL and is required for the formation of MUL1/MAPL-associated MDVs (Braschi et al. 2010). Another study investigating mitochondria morphology in in vitro and in vivo models reported that PD-associated VPS35 mutations cause mitochondrial fragmentation. Cultured neurons in vitro were transfected with VPS35 and mitoDsRed2 to label the mitochondria: the overexpression of wild-type VPS35 decreased mitochondrial length and increased the percentage of neurons with fragmented mitochondria. Of note, however, mitochondrial fragmentation was more profound upon expression of VPS35-D620N (Wang et al. 2016). The study also analysed mitochondrial morphology in fibroblasts derived from PD patients bearing the VPS35 D620N mutation and normal human fibroblasts from age-matched healthy controls. Confocal analysis revealed an interconnected mitochondrial network in the control fibroblasts, which became significantly fragmented in D620N fibroblasts. This finding was also confirmed by electron microscopy. To determine the effect of VPS35 mutants in vivo, the authors stereotactically injected lentivirus co-expressing VPS35 (WT or mutants) and mitoDsRed2 into mouse substantia nigra and imaged the tissues 3 weeks later. Neurons expressing WT VPS35 exhibited mitochondrial fragmentation that became more profound in the neurons expressing the D620N mutant. In cells and tissues expressing VPS35-D620N, mitochondrial fragmentation was associated with mitochondrial dysfunction, as assessed by ATP dosage, mitochondrial membrane potential analyses, and oxygen consumption rates. The authors explored the potential connection between VPS35 and dynamin-like protein 1 (DLP1), a GTPase recruited to the mitochondrial outer-membrane that forms a ring-like complex to exert fission activity, and found that VPS35 interacts with DLP1. They suggested that retromer, through VPS35–DLP1 interaction, mediates the removal of DLP1 complexes from the mitochondria and transports them to lysosomes for degradation. PD-associated VPS35 mutation increased the VPS35–DLP1 interaction, enhanced retromer-dependent turnover of the mitochondrial DLP1 complex through MDV-mediated trafficking, and tipped the mitochondrial dynamics towards excessive fission, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction and neuronal loss (Wang et al. 2016). In brief, accruing evidence suggests that VPS35 regulates mitochondrial function; future studies will disclose whether mitochondrial dysfunction is a key step in the neurodegenerative process in VPS35-mutated PD patients.

The Role of VPS35 in Neurotransmission

The VPS35 functions described so far (e.g., regulation of lysosomal function and mitochondrial homeostasis) are functions that the protein potentially exerts in the tissues in which it is expressed. But because VPS35 mutations are associated with the degeneration of DA neurons, there may exist a specific neuronal mechanism that is damaged by mutations in the gene. Supporting this hypothesis is evidence from numerous studies on the role of VPS35 in modulating synaptic transmission.

The normal distribution of endogenous VPS35 in the mammalian brain was investigated by subcellular fractionation. VPS35 was found enriched in multiple vesicular compartments, including microsomal vesicles, crude synaptosomes, and synaptic vesicle membranes (Tsika et al. 2014). A further characterization of the distribution of retromer in neurites of mouse hippocampal neurons showed that approximately 22% of VPS35 immunoreactivity also showed VAMP2/synaptobrevin immunoreactivity (Vazquez-Sanchez et al. 2018). This finding demonstrated that retromer can be found at synaptic locations and suggested a potential role of VPS35 in regulating synapse function.

Functional studies have shown that retromer regulates the trafficking of adrenergic and glutamatergic receptors to the plasma membrane (Choy et al. 2014), which suggested a role of VPS35 at the postsynapse terminal. Tian and co-authors investigated VPS35 function in neuronal spine formation and maturation and found that VPS35-deficiency impairs dendritic spine maturation and decreases glutamatergic transmission. They also found that VPS35 interacts with AMPA receptors and regulates AMPA receptor trafficking and that this molecular mechanism may underlie its function in promoting spine maturation and glutamatergic neurotransmission (Tian et al. 2015). Another study investigated the neuron-specific consequences of VPS35-D620N mutation and found that VPS35 localizes to dendritic spines and is involved in the trafficking of excitatory AMPA-type glutamate receptors. In addition, VPS35-D620N acts as a loss-of-function mutation in VPS35 activity (Munsie et al. 2015).

A recent study in Drosophila suggested that Vps35 also localizes at presynaptic terminals at the edge of the active zone, where it regulates synaptic vesicle (SV) recycling. The capacity for SV release was analysed using VMAT-pHluorin in DA neurons in adult brains. Neurons knocked down for Vps35 or bearing the mutation Vps35-D620N exhibited defects in SV release. These results suggest that Vps35 regulates SV dynamics and that the loss of Vps35 in Drosophila affects dopamine release (Inoshita et al. 2017). Another study reported that retromer is localized at the presynaptic terminal in mammalian cells. Using electron microscopy, Vazquez-Sanchez et al. observed immunoreactivity in a subset of hippocampal presynaptic terminals. VPS35 immunoreactivity was more frequently found in the presynaptic (82.4%) than in the postsynaptic side (17.6%). However, VPS35 depletion in hippocampal neurons did not alter presynaptic ultrastructure, SV release or retrieval. These data partially contrast with results obtained in Drosophila neurons (Inoshita et al. 2017). Hence, the retromer and VPS35 proteins are present in the presynaptic and postsynaptic terminals, but further studies are needed to clarify its functional role.

Potential Interaction Between VPS35 and Other PD-Related Genes

Various studies have highlighted a functional interaction between VPS35 and other genes associated with familial PD. Parkin, encoded by the PARK2 gene, is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that is commonly mutated in autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism (ARJP). Parkin-null Drosophila has reduced longevity, defective climbing, and increased sensitivity to paraquat (Cha et al. 2005; Malik et al. 2015). Malik et al. showed that VPS35 overexpression is able to rescue parkin-mutant phenotypes in Drosophila (Malik et al. 2015). This evidence suggests that VPS35 genetically interacts with parkin. Moreover, a study isolating ubiquitinated proteins in flies identified VPS35 as a parkin substrate (Martinez et al. 2017). A more recent study demonstrated a functional interaction between parkin and VPS35 by showing that parkin interacts with and ubiquitinates VPS35 (Williams et al. 2018). The interaction between parkin and the retromer subunit VPS35 was shown by immunoprecipitation in SH-SY5Y cells co-transfected with VPS35 and parkin. PD-associated mutations in VPS35 (D620N) or parkin (T240R, R256C, P437L, G328E, and C431F) did not decrease the interaction. Parkin increased the ubiquitination of VPS35 in SH-SY5Y cells co-expressing HA-tagged ubiquitin, and familial parkin mutations were impaired in their ability to ubiquitinate VPS35. The authors explored the nature of ubiquitin attachment to VPS35 mediated by parkin and found that this poly-ubiquitin chain attachment is not K48-linked, a chain linkage that normally targets substrates for proteasomal degradation. The authors suggested that parkin-mediated ubiquitination of VPS35 is not a signal for its proteasomal degradation and that VPS35 ubiquitination may serve to regulate retromer function (Williams et al. 2018). To determine whether parkin plays a role in the neurodegeneration induced by D620N VPS35 in vivo, Williams et al. used adenoviral vectors to express human VPS35-D620N in the substantia nigra of parkin KO mice or WT littermates. VPS35-D620N expression induced a robust loss of DA neurons in both the WT and the parkin KO mice. These results suggest that parkin is not required for dopaminergic neurodegeneration induced by PD-linked D620N and that VPS35 can be downstream of parkin in a molecular pathway that controls the function of the retromer complex (Williams et al. 2018).

Leucine-rich repeat protein kinase-2 (LRRK2) is a kinase that modulates vesicular trafficking by phosphorylating a subgroup of Rab proteins (Rui et al. 2018). Mutations of LRRK2 are linked to autosomal dominant forms of PD (Paisán-Ruíz et al. 2004). Drosophila models expressing mutant forms of LRRK2 develop locomotor deficits and eye lesions indicative of neuronal photoreceptor death (Venderova et al. 2009). Linhart et al. showed that LRRK2 phenotypes can be fully rescued by overexpressing VPS35. The authors suggested that VPS35 and LRRK2 are part of the same molecular pathway (Linhart et al. 2014). To further investigate the interplay between VPS35 and LRRK2, Mir and co-authors explored whether genetic manipulations of VPS35 affected LRRK2-mediated Rab protein phosphorylation. They found that knockdown of VPS35 or the expression of the VPS35 D620N mutant stimulated LRRK2 activity by enhancing the autophosphorylation of LRRK2. Consistent with LRRK2 activation, knockdown of VPS35 resulted in a marked elevation in the LRRK2-mediated phosphorylation of many other Rab proteins (Mir et al. 2018). These data indicate that VPS35 lies upstream of LRRK2 and that it plays a role in regulating LRRK2 kinase catalytic activity.

LRRK2 has a genetic interaction with PARK16, a non-familial PD risk-associated locus. One of the five genes within the PARK16 locus is RAB7L1. MacLeod et al. provided evidence supporting retromer dysfunction in the context of LRRK2–RAB7L1 pathway defects (MacLeod et al. 2013). In mouse N2A neuroblastoma cells, expression of the PD-variant LRRK2 G2019S or knockdown of RAB7L1 led to a significant reduction in the levels of VPS35, as well as VPS29. Expression of the R1441C mutant form of LRRK2 in mouse brain also led to a significant reduction in the level of VPS35, VPS29, and VPS26. Results from co-immunoprecipitation studies of LRRK2 with VPS35 supported a direct interaction between these proteins. Overexpression of VPS35 in Drosophila DA neurons rescued the DA neuronal loss caused by the PD-mutant LRRK2-G2019S, and similarly extended the lifespan of the LRRK2-G2019S mutant-expressing flies. The authors analysed VPS35 levels in the brain tissue from sporadic PD patients and unaffected individuals and observed a significant decrease in VPS35 mRNA levels in the tissues from the PD patients (MacLeod et al. 2013). Taken together, these results support a role for retromer deficiency in the effect of PD-associated genetic risk variants on brain neurons.

αSYN is a protein that accumulates in Lewy bodies in PD and other synucleinopathies (Goedert et al. 2017). Mutations in the αSYN gene (SNCA) are linked to familial PD (Nussbaum 2018). Cathepsin D (CTSD) is a lysosome protease involved in αSYN degradation (Aufschnaiter et al. 2017). Miura et al. found that VPS35 knockdown perturbed the maturation step of CTSD in parallel with accumulation of αSYN in the lysosomes. Moreover, they showed that knockdown of Vps35 in Drosophila induced accumulation of insoluble αSYN in the brain (Miura et al. 2014). These findings suggest that the retromer may play a crucial role in αSYN degradation.

Another study demonstrated the connection between VPS35 and αSYN (Dhungel et al. 2015). The study found a genetic interaction between αSYN and VPS35 in a yeast model and Caenorhabditis elegans and reported that lentiviral-mediated expression of wild-type VPS35 almost completely rescued αSYN-induced neurodegeneration in a mouse model. Conversely, upregulation of the PD-linked mutant VPS35-D620N resulted in more marked neuronal loss. The suggested mechanism by which wild-type VPS35 protected against neurodegeneration in αSYN mice was the ability of VPS35 to reduce the intra-neuronal accumulation of αSYN (Dhungel et al. 2015). These findings suggest that wild-type VPS35 suppresses αSYN accumulation, whilst expression of VPS35 mutant induces defective αSYN clearance, resulting in widespread αSYN accumulation. Surprisingly, a more recent study presented contrasting results: Chen and co-authors found no evidence for αSYN-positive neuropathology in VPS35-D620N KI mice (Chen et al. 2019). In detail, they found that heterozygous or homozygous D620N mutation is sufficient to reproduce the key neuropathological hallmarks of PD as a progressive degeneration of the nigrostriatal pathway and widespread axonal pathology. They also found robust tau-positive somatodendritic pathology but no evidence for αSYN positive neuropathology, even in aged VPS35 KI mice (Chen et al. 2019). The reason for the discrepancies amongst these studies is unclear. Further analyses of αSYN neuropathology in brain specimens from autopsy of VPS35-mutated patients are needed to clarify the matter. Only a single D620N mutation carrier has been identified at autopsy so far. Moreover, since necropsy had not been performed for neuropathological examination, only a limited amount of brain tissue was available from the cortex and basal ganglia, with the notable absence of the substantia nigra. Immunostaining for αSYN in this study was negative; nevertheless, the limited amount of tissue examined does not allow for definitive conclusions (Wider et al. 2008).

Hence, the interactions between VPS35 and other PD-associated genes, including α-SYNUCLEIN-PARKIN and LRRK2, can exist and suggest an interplay of various genes that leads to synaptic, mitochondrial, and lysosomal dysfunction in the pathogenesis of PD.

Conclusions

Accruing evidence shows that VPS35 protein modulates DA neuron survival and that the mutation D620N is associated with a form of PD that resembles idiopathic PD. The frequency of this mutation remains to be determined, as does the potential pathological role of other identified VPS35 variants. Carriers of other rare VPS35 variants may be at risk of developing PD, but the degree of risk is yet to be clarified (Deng et al. 2013; Williams et al. 2017). Considering the functional and genetic connections between VPS35 and other PD-associated genes, rare VPS35 variants may be an important additional factor in the development of the PD phenotype in patients carrying other mutations with incomplete penetrance. Genetic association analyses may soon be able to clarify this issue.

Another important point is the neuropathology of VPS35-associated PD. Limited data are currently available about the neuropathological spectrum of PD patients harbouring VPS35 mutations, since only one D620N mutation carrier has been investigated at autopsy until now (Wider et al. 2008). What remains to be defined is whether the neuronal loss in VPS35-associated PD occurs only in the SNc or also involves other brain areas such as the locus coeruleus, the cortex, the hippocampus, and other structures. Neuropathological examination of VPS35-D620N KI mouse models showed widespread tau pathology and axonal damage but no sign of αSYN inclusions (Chen et al. 2019). Whether the same features are present in PD patients harbouring VPS35 mutations is unknown.

In addition, further characterization of the role of VPS35 in promoting DA neuron survival is needed to understand the cellular pathways that are perturbed by VPS35 mutations and to identify therapeutic targets. Importantly, the D620N VPS35 KI model, together with the parkinQ311X mouse model (Lu et al. 2009), is one of the first models of monogenic PD to recapitulate the key PD feature: DA neuronal degeneration in the SNc. Therapeutic drug targets can be identified and validated using these murine models. Given the large overlap between the molecular mechanisms of neurodegeneration in the various forms of PD, drugs that can provide neuroprotection in VPS35 models may be tested in other more frequent parkinsonisms.

Author Contributions

JS had the idea for the article and drafted it. JS, CR, GD, and MR performed the literature search and data analysis. MTP and BG critically revised the work. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript for publication.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research Involving Human Participants and Animals

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Maria Teresa Pellecchia and Barbara Garavaglia are co-last authors.

References

- Ando M, Funayama M, Li Y et al (2012) VPS35 mutation in Japanese patients with typical Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 27:1413–1417. 10.1002/mds.25145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arighi CN, Harmell LM, Aguilar RC et al (2004) Role of the mammalian retromer in sorting of the cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor. J Cell Biol. 10.1083/jcb.200312055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aufschnaiter A, Kohler V, Büttner S (2017) Taking out the garbage: Cathepsin D and calcineurin in neurodegeneration. Neural Regen Res. 10.4103/1673-5374.219031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmingham CL, Smith AC, Bakowski MA et al (2006) Autophagy controls Salmonella infection in response to damage to the Salmonella-containing vacuole. J Biol Chem. 10.1074/jbc.M509157200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanckenberg J, Ntsapi C, Carr JA, Bardien S (2014) EIF4G1 R1205H and VPS35 D620N mutations are rare in Parkinson’s disease from South Africa. Neurobiol Aging. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.08.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifacino JS, Hurley JH (2008) Retromer. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol 20:427436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrageiro G, Haylett W, Seedat S et al (2018) A review of genome-wide transcriptomics studies in Parkinson’s disease. Eur J Neurosci 47:1–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braschi E, Goyon V, Zunino R et al (2010) Vps35 mediates vesicle transport between the mitochondria and peroxisomes. Curr Biol. 10.1016/j.cub.2010.05.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cataldi S, Follett J, Fox JD et al (2018) Altered dopamine release and monoamine transporters in Vps35 p.D620N knock-in mice. NPJ Park Dis. 10.1038/s41531-018-0063-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha G-H, Kim S, Park J et al (2005) Parkin negatively regulates JNK pathway in the dopaminergic neurons of Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 10.1073/pnas.0500346102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Kordich JK, Williams ET et al (2019) Parkinson’s disease-linked D620N VPS35 knockin mice manifest tau neuropathology and dopaminergic neurodegeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 10.1073/pnas.1814909116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YF, Chang YY, Lan MY et al (2017) Identification of VPS35 p.D620N mutation-related Parkinson’s disease in a Taiwanese family with successful bilateral subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation: a case report and literature review. BMC Neurol. 10.1186/s12883-017-0972-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choy RWY, Park M, Temkin P et al (2014) Retromer mediates a discrete route of local membrane delivery to dendrites. Neuron. 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.02.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng H, Gao K, Jankovic J (2013) The VPS35 gene and Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 28:569–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng H, Wang P, Jankovic J (2018) The genetics of Parkinson disease. Ageing Res Rev 42:72–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng H, Xu H, Deng X et al (2012) VPS35 mutation in Chinese Han patients with late-onset Parkinson’s disease. Eur J Neurol 19(9):e96–e97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutschländer A, Ross OA, Wszolek ZK (2019) VPS35-related Parkinson disease summary genetic counseling. University of Washington, Seattle, pp 1–17 [Google Scholar]

- Dhungel N, Eleuteri S, Li LB et al (2015) Parkinson’s disease genes VPS35 and EIF4G1 interact genetically and converge on α-synuclein. Neuron. 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.11.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson DW, Fujishiro H, Orr C et al (2009) Neuropathology of non-motor features of Parkinson disease. Park Relat Disord. 10.1016/S1353-8020(09)70769-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar AJ, Polak JM (2000) Human homologues of yeast vacuolar protein sorting 29 and 35. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwell C, Engel J (2018) Emerging role of retromer in modulating pathogen growth. Trends Microbiol 26(9):769–780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enami S, Sakamoto Y, Colussi AJ (2014) Fenton chemistry at aqueous interfaces. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 10.1073/pnas.1314885111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagliardi M, Annesi G, Tarantino P et al (2014) Frequency of the ASP620ASN mutation in VPS35 and Arg1205His mutation in EIF4G1 in familial Parkinson’s disease from South Italy. Neurobiol Aging. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedert M, Jakes R, Spillantini MG (2017) The synucleinopathies: twenty years on. J Parkinsons Dis 7:s51–s69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorostidi A, Martí-Massó JF, Bergareche A et al (2016) Genetic mutation analysis of Parkinson’s disease patients using multigene next-generation sequencing panels. Mol Diagnosis Ther. 10.1007/s40291-016-0216-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guella I, Soldà G, Cilia R et al (2012) The Asp620asn mutation in VPS35 is not a common cause of familial Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 27:800–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo JF, Sun QY, Lv ZY et al (2012) VPS35 gene variants are not associated with Parkinson’s disease in the mainland Chinese population. Park Relat Disord. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2012.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haft CR, de la Sierra ML, Bafford R et al (2000) Human orthologs of yeast vacuolar protein sorting proteins Vps 26, 29, and 35: assembly into multimeric complexes. Mol Biol Cell. 10.1091/mbc.11.12.4105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hierro A, Rojas AL, Rojas R et al (2007) Functional architecture of the retromer cargo-recognition complex. Nature. 10.1038/nature06216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirayama T, Inden M, Tsuboi H et al (2019) A Golgi-targeting fluorescent probe for labile Fe(ii) to reveal an abnormal cellular iron distribution induced by dysfunction of VPS35. Chem Sci. 10.1039/c8sc04386h [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoshita T, Arano T, Hosaka Y et al (2017) Vps35 in cooperation with LRRK2 regulates synaptic vesicle endocytosis through the endosomal pathway in Drosophila. Hum Mol Genet. 10.1093/hmg/ddx179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizu N, Yui D, Hebisawa A et al (2016) Impaired striatal dopamine release in homozygous Vps35 D620N knock-in mice. Hum Mol Genet. 10.1093/hmg/ddw279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalinderi K, Bostantjopoulou S, Katsarou Z et al (2015) D620N mutation in the VPS35 gene and R1205H mutation in the EIF4G1 gene are uncommon in the Greek population. Neurosci Lett. 10.1016/j.neulet.2015.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein C, Hattori N, Marras C (2018) MDSGene: Closing data gaps in genotype-phenotype correlations of monogenic Parkinson’s disease. J Parkinsons Dis 8:s25–s30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroemer G, Mariño G, Levine B (2010) Autophagy and the integrated stress response. Mol Cell 40(2):280–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar KR, Weissbach A, Heldmann M et al (2012) Frequency of the D620N mutation in VPS35 in Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 10.1001/archneurol.2011.3367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence RE, Zoncu R (2019) The lysosome as a cellular centre for signalling, metabolism and quality control. Nat Cell Biol 21(2):133–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Shah SZA, Zhao D, Yang L (2016) Role of the retromer complex in neurodegenerative diseases. Front Aging Neurosci 8:42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linhart R, Wong SA, Cao J et al (2014) Vacuolar protein sorting 35 (Vps35) rescues locomotor deficits and shortened lifespan in Drosophila expressing a Parkinson’s disease mutant of Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2). Mol Neurodegener. 10.1186/1750-1326-9-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X-H, Fleming SM, Meurers B et al (2009) Bacterial artificial chromosome transgenic mice expressing a truncated mutant parkin exhibit age-dependent hypokinetic motor deficits, dopaminergic neuron degeneration, and accumulation of proteinase K-resistant alpha-synuclein. J Neurosci 29:1962–1976. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5351-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas M, Gershlick DC, Vidaurrazaga A et al (2016) Structural mechanism for cargo recognition by the retromer complex. Cell. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunati A, Lesage S, Brice A (2018) The genetic landscape of Parkinson’s disease. Rev Neurol 174(9):628–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod DA, Rhinn H, Kuwahara T et al (2013) RAB7L1 Interacts with LRRK2 to modify intraneuronal protein sorting and Parkinson’s disease risk. Neuron. 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.11.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak SK, McCormack AL, Manning-Bog AB et al (2010) Lysosomal degradation of α-synuclein in vivo. J Biol Chem. 10.1074/jbc.M109.074617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik BR, Godena VK, Whitworth AJ (2015) VPS35 pathogenic mutations confer no dominant toxicity but partial loss of function in Drosophila and genetically interact with parkin. Hum Mol Genet 24:6106–6117. 10.1093/hmg/ddv322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marras C, Canning CG, Goldman SM (2019) Environment, lifestyle, and Parkinson’s disease: Implications for prevention in the next decade. Mov Disord 34(6):806–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez A, Lectez B, Ramirez J et al (2017) Quantitative proteomic analysis of Parkin substrates in Drosophila neurons. Mol Neurodegener. 10.1186/s13024-017-0170-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGough IJ, Steinberg F, Jia D et al (2014) Retromer binding to FAM21 and the WASH complex is perturbed by the Parkinson disease-linked VPS35(D620N) mutation. Curr Biol. 10.1016/j.cub.2014.06.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mir R, Tonelli F, Lis P et al (2018) The Parkinson’s disease VPS35[D620N] mutation enhances LRRK2-mediated Rab protein phosphorylation in mouse and human. Biochem J. 10.1042/bcj20180248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura E, Hasegawa T, Konno M et al (2014) VPS35 dysfunction impairs lysosomal degradation of α-synuclein and exacerbates neurotoxicity in a Drosophila model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan M, Mellick GD (2017) Role of the VPS35 D620N mutation in Parkinson’s disease. Park Relat Disord 36:10–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munsie LN, Milnerwood AJ, Seibler P et al (2015) Retromer-dependent neurotransmitter receptor trafficking to synapses is altered by the Parkinson’s disease VPS35 mutation pD620N. Hum Mol Genet. 10.1093/hmg/ddu582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuspiel M, Schauss AC, Braschi E et al (2008) Cargo-selected transport from the mitochondria to peroxisomes is mediated by vesicular carriers. Curr Biol. 10.1016/j.cub.2007.12.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum RL (2018) Genetics of synucleinopathies. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 10.1101/cshperspect.a024109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuytemans K, Bademci G, Inchausti V et al (2013) Whole exome sequencing of rare variants in EIF4G1 and VPS35 in Parkinson disease. Neurology 80:982–989. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828727d4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obeso JA, Stamelou M, Goetz CG (2017) Past, present, and future of Parkinson’s disease: A special essay on the 200th Anniversary of the Shaking Palsy. Mov. Disord 32(9):1264–1310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paisán-Ruíz C, Jain S, Evans EW et al (2004) Cloning of the gene containing mutations that cause PARK8-linked Parkinson’s disease. Neuron. 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang SYY, Ho PWL, Liu HF et al (2019) The interplay of aging, genetics and environmental factors in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Transl Neurodegener 8(1):23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paravicini G, Horazdovsky BF, Emr SD (1992) Alternative pathways for the sorting of soluble vacuolar proteins in yeast: a vps35 null mutant missorts and secretes only a subset of vacuolar hydrolases. Mol Biol Cell. 10.1091/mbc.3.4.415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pont-Sunyer C, Hotter A, Gaig C et al (2015) The onset of nonmotor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease (the onset PD study). Mov Disord. 10.1002/mds.26077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priya A, Kalaidzidis IV, Kalaidzidis Y et al (2015) Molecular Insights into Rab7-mediated endosomal recruitment of core retromer: deciphering the role of Vps26 and Vps35. Traffic. 10.1111/tra.12237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar B (2002) Aggregate-prone proteins with polyglutamine and polyalanine expansions are degraded by autophagy. Hum Mol Genet. 10.1093/hmg/11.9.1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar B, Vacher C, Berger Z et al (2004) Inhibition of mTOR induces autophagy and reduces toxicity of polyglutamine expansions in fly and mouse models of Huntington disease. Nat Genet. 10.1038/ng1362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas R, Van Vlijmen T, Mardones GA et al (2008) Regulation of retromer recruitment to endosomes by sequential action of Rab5 and Rab7. J Cell Biol. 10.1083/jcb.200804048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rui Q, Ni H, Li D et al (2018) The Role of LRRK2 in Neurodegeneration of Parkinson Disease. Curr Neuropharmacol. 10.2174/1570159x16666180222165418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schapira AHV, Chaudhuri KR, Jenner P (2017) Non-motor features of Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 18(7):435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaman MNJ (2012) The retromer complex-endosomal protein recycling and beyond. J. Cell Sci. 125(20):4693–4702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaman MNJ (2005) Recycle your receptors with retromer. Trends Cell Biol 15(2):68–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaman MNJ, Harbour ME, Tattersall D et al (2009) Membrane recruitment of the cargo-selective retromer subcomplex is catalysed by the small GTPase Rab7 and inhibited by the Rab-GAP TBC1D5. J Cell Sci. 10.1242/jcs.048686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaman MNJ, Marcusson EG, Cereghino JL, Emr SD (1997) Endosome to Golgi retrieval of the vacuolar protein sorting receptor, Vps10p, requires the function of the VPS29, VPS30, and VPS35 gene products. J Cell Biol. 10.1083/jcb.137.1.79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]