Abstract

Neural crest cells (NCCs) comprise a population of multipotent progenitors and stem cells at the origin of the peripheral nervous system (PNS) and melanocytes of skin, which are profoundly influenced by microenvironmental factors, among which is basic fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2). In this work, we further investigated the role of this growth factor in quail trunk NC morphogenesis and demonstrated its huge effect in NCC growth mainly by stimulating cell proliferation but also reducing cell death, despite that NCC migration from the neural tube explant was not affected. Moreover, following FGF2 treatment, reduced expression of the early NC markers Sox10 and FoxD3 and improved proliferation of HNK1-positive NCC were observed. Since these markers are involved in the regulation of glial and melanocytic fate of NC, the effect of FGF2 on NCC differentiation was investigated. Therefore, in the presence of FGF2, increased proportions of NCCs positives to the melanoblast marker Mitf as well as NCCs double stained to Mitf and BrdU were recorded. In addition, treatment with FGF2, followed by differentiation medium, resulted in increased expression of melanin and improved proportion of melanin-pigmented melanocytes without alteration in the glial marker Schwann myelin protein (SMP). Taken together, these data further reveal the important role of FGF2 in NCC proliferation, survival, and differentiation, particularly in melanocyte development. This is the first demonstration of FGF2 effects in melanocyte commitment of NC and in the proliferation of Mitf-positive melanoblasts. Elucidating the differentiation process of embryonic NCCs brings us a step closer to understanding the development of the PNS and then undertaking the search for advanced technologies to prevent, or treat, injuries caused by NC-related disorders, also known as neurocristopathies.

Keywords: Stem cell, Survival, Peripheral nervous system, Melanocyte, Glial cell, Neural crest culture

Introduction

The neural crest (NC) is a transient structure of vertebrate embryos that arises at the closing borders of neural tube during neurulation. It consists of a collection of cells, most of which are highly multipotent and endowed with both neural and mesenchymal potentials. Upon induction, NC cells (NCCs) undergo epithelial-mesenchymal transition and migrate across the embryonic body until their final destination where they give rise to many derivatives, including most neurons and glial cells of the peripheral nervous system (PNS), melanocytes of the skin, and most mesenchymal structures of the head. By using the clonal cell culture approach, we and others have demonstrated that NCCs from the trunk region of quail embryos comprise various subsets of multipotent progenitors able to give rise to glial cells, neurons, melanocytes, myofibroblasts, adipocytes, chondrocytes, and osteocytes (Trentin et al. 2004; Calloni et al. 2009; Coelho-Aguiar et al. 2013). In addition, the self-renewal capacity of various subsets of NC progenitors was demonstrated in culture that therefore displays the characteristics of true stem cells (Trentin et al. 2004; Bittencourt et al. 2013).

Of particular interest is lineage separation between neural and non-neural phenotypes, such as melanocytes, since some diseases of the NC-derived nervous system are frequently associated with abnormal pigmentation (Adameyko and Lallemend 2010; Dupin and Sommer 2012; Sommer 2018). NC progenitors endowed with both glial and melanocyte potentials and able to self-renewal were previously identified by in vitro clonal and sub-clonal analyses (Trentin et al. 2004; Dupin and Sommer 2012; Bittencourt et al. 2013). More recently, in vivo assays using genetically marked mouse lines showed that Schwann cell precursors associated with the axons of spinal nerves could detach, change their fate to that of melanocyte lineage, and subsequently migrate toward the epidermis (Adameyko et al. 2009; Adameyko and Lallemend 2010).

Migration and differentiation of NCCs are controlled by a complex gene regulatory network that includes transcriptional factors, such as Forkhead Box D3 (FoxD3) and SRY-Box 10 (Sox10), associated with the NC stem cell-like properties of multipotentiality and self-renewal, as well as NC identity, survival, and migration (Aquino 2017). Furthermore, FoxD3 controls lineage choice between neural/glial and pigmented cells by repressing the melanocytic gene microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (Mitf) during the early phase of NC migration (Thomas and Erickson 2009). Mitf is an earlier marker of melanoblast lineage and essential for melanogenesis (Levy et al. 2006). Sox10, on the other hand, activates Mitf expression and controls the survival and expansion of melanocytic lineage. In this sense, depletion of Sox10 gene expression affects the generation of PNS structures and melanocytes and causes Waardenburg–Hirschsprung disease associated with defects in the enteric nervous system and pigmentation (Sommer 2018). In glial cells, however, Sox10 expression continues in embryos and in adults (Hall 2009).

Microenvironmental factors, such as fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF2), which are found by NCCs during their migration through the embryonic tissue, significantly influence their development (Le Douarin and Kalcheim 1999). FGF2 is related to multiple functions in NC development including NC migration (Kubota and Ito 2000), proliferation, and survival (Kalcheim 1989; Murphy et al. 1994; Zhang et al. 1997) in addition to the skeletogenic (Sarkar et al. 2001) and chondrogenic specification of mesencephalic NCCs (Nakanishi et al. 2007). Moreover, in a previous study, we demonstrated that FGF2 maintains NCCs in an undifferentiated state and enhances the proportion of the multipotent NC progenitors able to give rise to glial cells, neurons, melanocytes, and myofibroblasts (Bittencourt et al. 2013). In addition, FGF2 promotes the propagation of the bipotent glial-smooth muscle precursors along many generations, which, therefore, behave as stem cells (Bittencourt et al. 2013). FGF2 also stimulates the glial phenotype in NCC cultures (Ota and Ito 2006; Garcez et al. 2009) and is related to the proliferation of adult and neonatal human melanocytes in culture synergically with dibutyryl cyclic AMP, endothelin-1, and/or α-melanocyte stimulating hormone (Halaban et al. 1987; Swope et al. 1995; Hirobe et al. 2010). FGF2 was also shown to enhance the pigmentation of cultured quail embryonic dorsal root ganglion and peripheral nerve cells (Stocker et al. 1991), and to influence melanoma development and progression (Nesbit et al. 1999; Meier et al. 2003). Despite the broad information in the literature about the involvement of FGF2 in NC morphogenesis, the approach of the studies is ample and sometimes controversial. Besides, its involvement in the melanocytic differentiation of NCCs has never been properly demonstrated.

Considering the great importance of FGF2 in NC morphogenesis and development and its possible involvement in neurocristopathies, in this work, we further investigated the cellular and molecular role of FGF2 in quail NCC growth and differentiation especially to glial cells and melanocytes. Our results demonstrate that FGF2 promotes the growth of NCCs mostly by stimulating cell proliferation but also by decreasing cell death. In addition, our findings showed for the first time the involvement of FGF2 in the melanocytic commitment of NCCs and in the proliferation of Mitf-positive melanoblasts, and point to its important role in PNS development and associated disorders.

Experimental Procedures

Quail NCC Cultures

Quail NCC cultures were performed as previously described (Bittencourt et al. 2013; Trentin et al. 2016). Briefly, neural tubes from quail embryos (23 to 25 somite stage) were dissected at the trunk level and plated in uncoated culture dishes (35 mm, Corning) in basal medium consisting of α-minimum essential medium (α -MEM, Invitrogen), enriched with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Vitrocell, lot 015/16), 2% chicken embryonic extract, penicillin (200 U/mL, Invitrogen), and streptomycin (10 µg/mL, Invitrogen) with or without FGF2 (10 ng/mL, Sigma). Cultures were maintained in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 10% O2. After 18 h, NCCs that migrated from the neural tubes were harvested from culture dishes (0.2% trypsin, Sigma) and plated in secondary cultures (2600 cells/cm2) on rat-tail collagen-coated surfaces (5 µg/cm2, BD). Cells were cultured for an additional 24, 48, or 72 h in basal medium with or without FGF2 (10 ng/mL). Cell differentiation after FGF2 treatment was induced in some experiments by maintaining cultures for an additional 2 days in complex inductive medium. This consisted of basal medium supplemented with hydrocortisone (0.1 µg/mL), transferrin (10 µg/mL), insulin (1 ng/mL), 3-3′-5 triiodothyronine (0.4 ng/mL), glucagon (0.01 ng/mL), EGF (0.1 ng/mL), and FGF2 (0.2 ng/mL) (all from Sigma) (Bittencourt et al. 2013).

Analysis of NCC Migration in Primary Cultures

Migration of NCCs from neural tubes to the culture plates was analyzed after 18 h of primary culture. The outgrowth area was measured, and migration values were calculated by subtracting the neural tube explant area from the total migration area by using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health), as previously described (Costa-Silva et al. 2009).

Immunocytochemistry

Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (30 min), permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma, 30 min), and blocked with 5% FBS (1 h) at room temperature. Samples were then incubated (1 h) with the following primary antibodies: mouse monoclonal anti-HNK1 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank) (Abo and Balch 1981), rabbit polyclonal anti-Sox10 (Abcam), mouse monoclonal anti-SMP (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank) (Dulac et al. 1988), or mouse monoclonal [C5] anti-Mitf (Abcam). This was followed by incubation (1 h) with the secondary antibodies Alexa 594-conjugated anti-mouse IgM, Alexa 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG, or Alexa 488-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibodies (all 1:1000 and all from Invitrogen). Cell nuclei were stained with 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI, Sigma) for 5 min at room temperature. Fluorescence labeling and melanin expression were observed using an epifluorescent/bright-field inverted Olympus IX71 microscope, and images were captured with an Olympus DP71 camera. Analysis was performed on immunolabeled cells, fluorescence intensity, or melanin intensity in at least 20 random fields (× 400 magnification) with ImageJ software. Total number of DAPI-labeled nuclei was considered the total cell number (100%).

Cell proliferation and Cell Death Assays

Cell proliferation was analyzed by 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU, Invitrogen) incorporation, as previously described (Costa-Silva et al. 2009) with some modifications. Briefly, cells were incubated with 10 mM BrdU (1 h, 37 °C), fixed, and permeabilized, as described above. This was followed by incubation with 2 N HCl (2 times, 15 min, 37 °C). After washing in borate buffered saline (10 min), cells were immunostained with a rat monoclonal [BU1/75 (ICR1)] anti-BrdU antibody (1:100, Abcam), followed by Alexa 488-conjugated anti-rat IgG antibody (1:1000, Invitrogen). Cell death was assessed by immunostaining with a rabbit polyclonal anti-Caspase-3 antibody (1:500, Abcam), followed by Alexa 488-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1:1000, Invitrogen). Alternatively, chromatin condensation and nuclear fragmentation (pyknotic nuclei) after DAPI staining were assessed. Labeling was visualized and quantified, as described for immunofluorescence staining. Alternatively, after detachment with trypsin in a Neubauer chamber, we used direct counting to assess the total cell number.

Real-time qPCR

RNA samples were prepared using the RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen), and cDNA was generated with the SuperScript® III Kit (Invitrogen), following the manufacturers’ instructions. Real-time qPCR was performed using the StepOne™ Real-Time SYBR green PCR System (Applied Biosystems) with gene-specific primers. Briefly, 50 ng cDNA was incubated with SYBR Green/ROX qPCR Master Mix (2 times) (Thermo Scientific) and specific oligonucleotide primers as follows: 95 °C for 10 min, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s. Data were analyzed according to Pfaffl’s method. Mitochondrial ribosomal protein S27 (Mrps27) was used as the normalizer gene. The following primer sets were used: FoxD3 sense 5′-CCACAACCTCTCGCTCAAC-3′; FoxD3 anti-sense 5′-TTGTCGAACATGTCCTCAGAC -3′; Sox10 sense 5′-AACGCCTTCATGGTCTGG-3′; Sox10 anti-sense 5′-GGGACGCTTATCACTTTCATTC-3′; Mitf sense 5′-CAAGCTCAGCGGCAGCAGGT-3′; Mitf anti-sense 5′- CCATCGGACTGTTGGGCGCA-3′; Mrps27 sense 5′-GCTTGTTCTTGCTCCCACTC-3′; Mrps27 anti-sense 5′-TAACCCTGACCACCCAACTC-3′.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical differences between samples were evaluated by unpaired Student’s t test using GraphPad Prism 6.0 software (GraphPad Software, Inc.). The level of significance was set at p < 0.05 in all cases. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and results represent the mean of at least three independent experiments.

Results

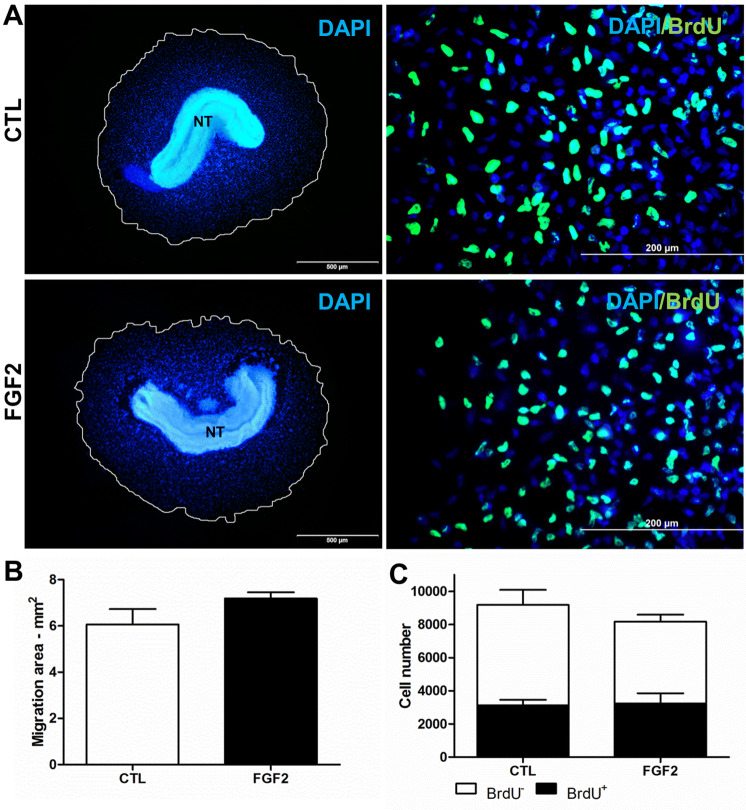

FGF2 Treatment During NCC Emigration from Neural Tube

We previously demonstrated the effect of early FGF2 treatment on NCC differentiation during the primary culture when cells are undifferentiated and migrating from the neural tube (Garcez et al. 2009). Here, we evaluated if FGF2 also affects the migration of NCCs from neural tube and their proliferation at this very early stage of NCC culture. Figure 1 shows representative pictures (Fig. 1a) and quantification (Fig. 1b) of NCC migration and BrdU incorporation (Fig. 1c). The outgrowth of NCCs was similar to that of control (6.05 mm2) and FGF2-treated cultures (7.18 mm2). The total number of cells stained with DAPI (about 8000–9000 cells) and the number of BrdU-positive NCCs (about 3000 cells) were also similar between treatments. These findings suggest that FGF2 does not significantly affect the migration of NCCs from the neural tube or their proliferation during the 18 h of primary culture.

Fig. 1.

FGF2 does not alter NCC migration and proliferation at 18 h of primary culture during emigration from the neural tube. a Immunofluorescence of NCC nuclei stained with DAPI (blue) and after BrdU labeling (green). Lines (left panels) show the outgrowth of NCCs measured, as described in Materials and Methods, to calculate the (b) migrating area. c Quantification of BrdU-positive and BrdU-negative NCCs. Values are expressed as an absolute number (mean ± SEM) of 20 random fields in three independent experiments. Statistically significant differences were tested by Student’s t test. CTL untreated control cultures, NT explant of the neural tube. Scale bar = 500 µm (left) and 200 µm (right)

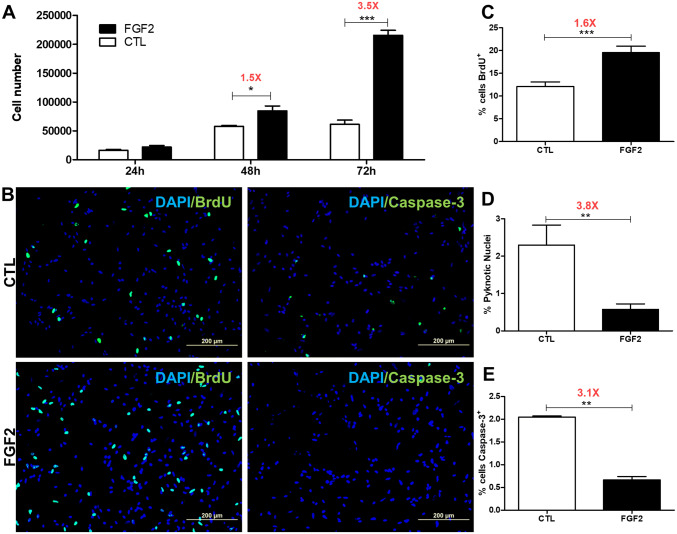

FGF2 Treatment Stimulates NCC Proliferation and Survival in the Secondary Culture

As FGF2 treatment maintains NCCs in the undifferentiated progenitor state (Bittencourt et al. 2013), we investigated if the growth factor would affect NCC proliferation and survival during the first 72 h of secondary culture after migration from the neural tube (Fig. 2). In the absence of FGF2, about 16,000 cells at 24 h of secondary culture were recorded that increased to 58,000 cells at 48 h and to 61,000 at 72 h (Fig. 2a). Huge increase in the number of NCCs, however, was observed after FGF2 treatment that enhanced from about 22,000 cells at 24 h, to 85,000 cells at 48 h and to 215,000 cells at 72 h of secondary culture, values significantly different at 48 and 72 h in comparison to the untreated control cultures (1.5-fold and 3.5-fold, respectively) (Fig. 2a). Cell proliferation was then evaluated at this later time of culture (Fig. 2b–c). Results revealed BrdU incorporation 1.6-fold higher in FGF2-treated cultures compared to control ones (12% and 19.5% of cells, respectively), demonstrating significant increase in the proliferation rate (Fig. 2b left panel, c). Next, cell death was investigated (Fig. 2d, e). Even though the proportion of pyknotic nuclei (Fig. 2d) and caspase-3 positive cells (Fig. 2b right panel, e) was low in both culture conditions (less than 3%), FGF2-treatment significant reduced these values (3.8-fold and 3.1-fold, respectively), revealing an effect also in NCC survival. Taken together these findings further demonstrate the important effect of FGF2 in the expansion of NCC population and suggest that it is mainly due to its action in stimulating cell proliferation but also in the reduction of NCC death.

Fig. 2.

FGF2 stimulates NCC proliferation and survival in secondary cultures. a Total number of cells was assessed by direct counting at 24, 48, or 72 h after FGF2 treatment. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments performed in triplicate. b Immunofluorescence for BrdU (green in left panels) and caspase-3 (green in right panels) at 72 h following FGF2 treatment. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Quantification of c BrdU-positive, d pyknotic nuclei, or e caspase-3-positive NCCs in relation to the total number of cells (DAPI-positive). Values are expressed as a percentage (mean ± SEM) of 20 random fields in three independent experiments. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 by Student’s t test. CTL untreated control cultures. Scale bar = 200 µm

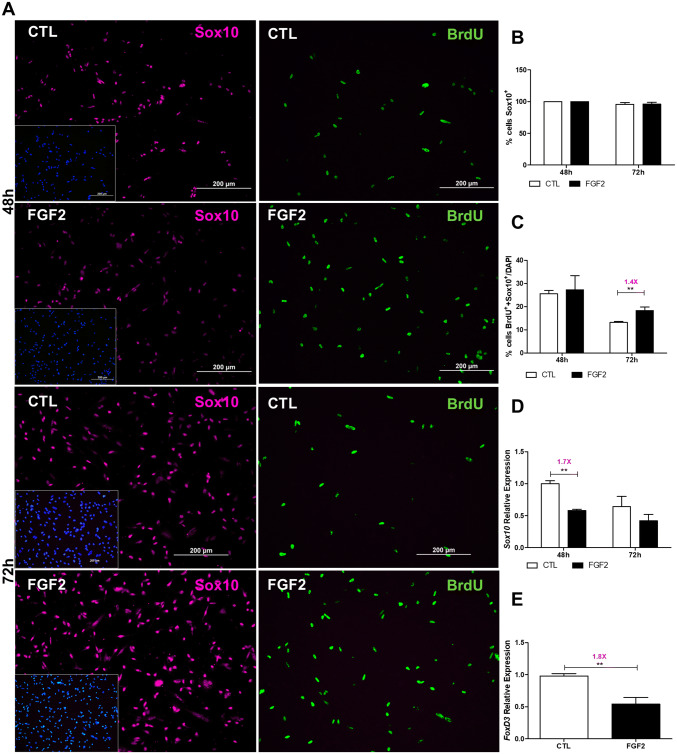

FGF2 Affects NCC Early Markers

Next, we evaluated if FGF2 treatment would affect HNK1, Sox10, and FoxD3, three early markers involved in NCC multipotentiality and differentiation (Bronner-Fraser Bronner-Fraser 1986; Kim et al. 2003; Nitzan et al. 2013a; Hochgreb-Hägele and Bronner 2013) (Figs. 3 and 4). In both culture conditions, all NCCs were positive for Sox10 at 48 h of the secondary culture and more than 95% at 72 h (Fig. 3a, b) attesting to their NC identity (Kim et al. 2003; Sauka-Spengler and Bronner-Fraser 2008). Importantly, 13.2% and 18.3% of the Sox10-positive cells, control and FGF2-treated culture conditions, respectively, were positives for BrdU (Fig. 3a, c) at 72 h demonstrating an increase of 1.4-fold in the later and confirming the proliferative effects of FGF2 in NCC proliferation shown in Fig. 2c. Results also revealed a progressive reduction in the mRNA levels of Sox10 in control NCC cultures from 48 h to 72 h, coherent with Sox10 developmental pattern previously described (Kuhlbrodt et al. 1998), whereas in FGF2-treated cultures reduction in its levels (1.7-fold) could already be detected at 48 h (Fig. 3d). Considering that almost all NCCs express Sox10 protein at these time points in both conditions (Fig. 3b) and that reduction in the mRNA levels precedes the reduction of the protein levels, it could be suggested that FGF2 influence the NC differentiation at early phases of development. In this sense, significant reduction in the relative levels of FoxD3 (1.8-fold) mRNA was also observed (Fig. 3e) in cultures treated by FGF2.

Fig. 3.

FGF2 affects Sox10 and FoxD3 expression. a Immunoreaction of NCCs double labeled for Sox10 (magenta) and BrdU (green) at 48 h and 72 h of FGF2 treatment. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue, inset). Proportion of b Sox10-positive NCCs in relation to the total number of cells (DAPI-positive), c Sox10 and BrdU double-labeled NCCs in relation to DAPI, d Sox10 mRNA expression, and e FoxD3 mRNA expression. Values are expressed as a percentage (mean ± SEM) of 20 random fields in three independent experiments. Relative quantification by quantitative RT-PCR analysis of d Sox10 or e FoxD3 mRNA expression levels compared with control cells (white columns). Mrps27 was used as the normalizer gene. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM of five independent experiments in triplicate. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01 by Students t test. CTL untreated control cultures. Scale bar = 200 µm

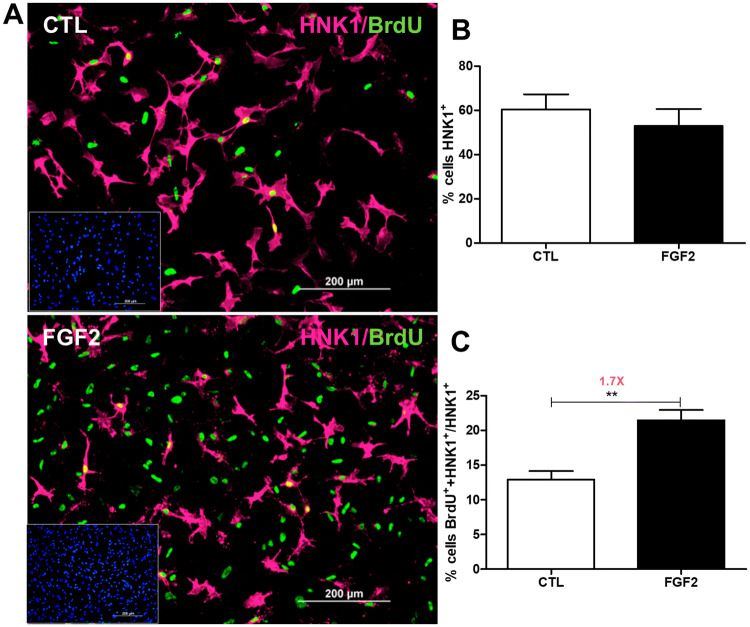

Fig. 4.

FGF2 stimulates the proliferation of HNK1-positive NCCs. Secondary cultures of NCCs were treated with FGF2 during 72 h. a Immunofluorescence for BrdU (green), HNK1 (magenta), and DAPI (blue, inset). Quantification of b HNK-1-positive NCCs in relation to the total number of cells (DAPI-positive) and of c HNK-1 and BrdU double-labeled NCCs in relation to HNK-1-positive NCCs. Values are expressed as a percentage (mean ± SEM) of 20 random fields in three independent experiments. **p < 0.01 by Student’s t test. CTL untreated control cultures. Scale bar = 200 µm

Moreover, the proportion of HNK1-positive NCCs corresponded to about 60% of cells in both culture conditions at 72 h of secondary culture (Fig. 4a, b). Further analysis revealed that 12.9% and 21.4% of these cells were also positive for BrdU in control and FGF2-treated conditions, respectively, representing an increase of 1.7-fold after treatment (Fig. 4c). Although FGF2 did not alter the proportion of HNK1-positive cells, this result suggested that it did stimulate their proliferation, which might be related to the increased cell proliferation at this time point, as indicated in Fig. 2c.

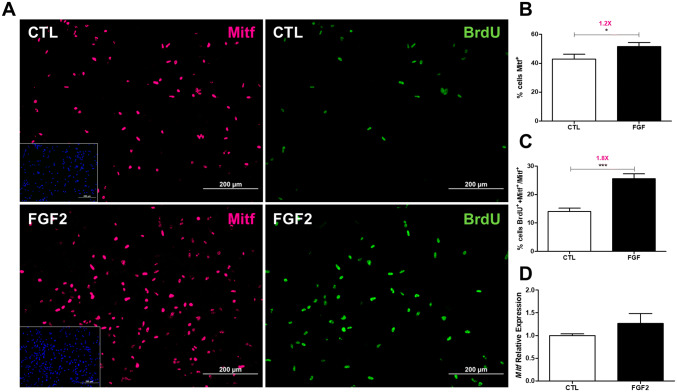

FGF2 Improves Melanocytic Differentiation after Inductive Stimulus

Since Sox10, HNK1, and FoxD3 are involved in glial and melanocytic differentiation (Calloni et al. 2009; Thomas and Erickson 2009; Harris et al. 2013; Nitzan et al. 2013b; Aquino and Sierra 2018), we next evaluated if FGF2 treatment could affect the expression of these types of cells. Therefore, the proportion and proliferation of Mitf-positive melanoblasts in NCC cultures of 72 h was investigated (Fig. 5), since Mitf is an earlier marker of melanoblast lineage and essential for melanogenesis (Levy et al. 2006). In control cultures, 42.9% of cells were positives to Mitf, value increased 1.2-fold after FGF2 treatment to 51.5% (Fig. 5a left panel, b). Moreover, 25.5% of the Mitf-positive cells were double stained with BrdU in FGF2-treated condition, 1.8-fold increase compared to untreated cultures (Fig. 5a right panel, c), suggesting the growth factor action in melanoblast proliferation, although the relative levels of Mitf mRNA was not significant altered in these cultures (Fig. 5d).

Fig. 5.

FGF2 affects Mitf-positive NCCs. a Immunostaining of NCCs double labeled for Mitf (magenta) and BrdU (green) at 72 h of FGF2 treatment. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue, inset). Proportion of b Mitf-positive NCCs in relation to DAPI and c Mitf and BrdU double-labeled NCCs in relation to Mitf-positive NCCs. Values were obtained from analysis of 20 random fields from two independent experiments and expressed as ratio of mean ± SEM. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis for d Mitf mRNA expression in the same time of FGF2-treatment. Values were obtained from five independent experiments performed in triplicate and expressed as ratio of mean ± SEM. ***p < 0.001, *p < 0.05 versus control cultures at each time interval by t test. CTL untreated control cultures. Scale bar = 200 µm

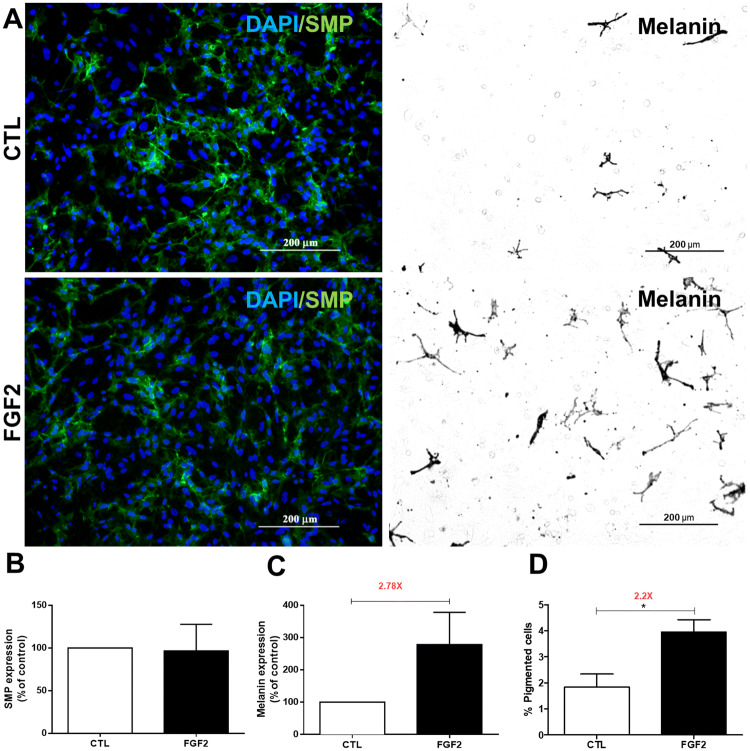

Bittencourt et al. (2013) reported that NCCs remain in an undifferentiated and progenitor state in the presence of FGF2 and that growth factor substitution by an inductive medium is required for cell differentiation. Therefore, following the first FGF2 treatment of 72 h, an additional 48 h was performed in complex medium (Fig. 6). Glial cells were identified by the expression of Schwann myelin protein (SMP) (Fig. 6a left panels) and mature melanocytes by the presence of melanin (Fig. 6a right panel). Quantifying the intensity of SMP immunofluorescence revealed no difference between FGF2-treated cultures and those of control (Fig. 6b). In contrast, quantifying the intensity of the melanin signal and the number of melanin-positive melanocytes demonstrated an increase of 2.7-fold and 2.2-fold, respectively, in FGF2-treated cultures compared to the respective control (Fig. 6c, d), revealing improved melanocytic differentiation after inductive stimulation.

Fig. 6.

FGF2 treatment affects NCC differentiation. Secondary cultures of NCCs were performed in the presence or absence of FGF2 for 72 h and then maintained in complex inductive medium for an additional 48 h, as described in Materials and Methods. a (left panels) Immunofluorescence for SMP (green) and DAPI (blue) staining and a (right panels) bright-field microscopy of melanin-pigmented cells. Quantitative analysis of b SMP fluorescence or c melanin intensity as arbitrary units expressed as a percentage of the control (considered 100%, white columns) normalized by the total number of cells (DAPI-positive). d Quantitative analysis of melanin-pigmented cells expressed as a percentage of the total number of cells. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM of 20 random fields in three independent experiments. *p < 0.05 by Student t test. CTL untreated control cultures. Scale bar = 200 µm

Discussion

In the present paper, we further investigated the role of FGF2 in the morphogenesis of trunk NCCs from quail embryos. The growth factor promoted a great expansion in NCC population in the secondary culture mainly by stimulating cell proliferation but also by reducing cell death. Accordingly, FGF2 was already reported as involved in the proliferation of epidermal NC stem cells (EPI-NCSCs) of mouse whisker follicles when added together with epidermal growth factor (Bressan et al. 2014). On the other hand, Murphy et al. (1994) showed that FGF2 induced cell proliferation and neuronal differentiation in NCCs from 10 day-mouse embryos with acquisition of a sensory neuronal morphology when the treatment was followed by addition of leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF); they, however, did not observe effects in NC survival. Our study also contrast with that of Abzhanov et al. (2003) that suggested the FGF2 action in the proliferation and survival of the cranial, but not trunk, NC (Abzhanov et al. 2003). Moreover, in our study FGF2 did not alter the proliferation or migration of NCCs from the neural tube explants during the primary culture (migration phase) in contrast to its previously reported chemoattractant effect on the migration of mesencephalic mouse NCC in organ culture (Kubota and Ito 2000). Differences in animal, culture models, FGF2 treatment, and phase of NC development among studies might explain dissimilar findings that also suggest the growth factor action in specific time windows of the NC differentiation.

Subsequently, the expressions of HNK1, Sox10, and FoxD3, three early markers involved in the multipotentiality and differentiation of NCC, were then evaluated. In our experiments, almost all cell were positives to Sox10 at both 48 and 72 h of the secondary culture and all BrdU-positive cells at these time periods were double stained for Sox10, attesting to their undifferentiated and proliferative NC identity (Kim et al. 2003; Sauka-Spengler and Bronner-Fraser 2008). Moreover, reduction in the mRNA levels of Sox10 and FoxD3 was detected consistent with the initiation of the differentiation processes at this time of NCC culture. In addition, FGF2 treatment stimulated the proliferation of Sox10-positive cells accompanied by reduction in the mRNA levels of Sox10 and FoxD3 corroborating its effects in NCC proliferation and differentiation.

In the avian embryo, HNK1 were reported to label the most undifferentiated migratory NCCs, followed by retention in the PNS, but not in melanocytes or mesenchymal NC derivatives (Vincent et al. 1983; Tucker et al. 1984). By using clonal cultures of quail cephalic NCCs, however, Dupin et al. (2018) recently showed that HNK1-expressing NCCs are in fact multipotent cells able to originate neurons, Schwann cells, melanocytes, myofibroblasts, and chondrocytes (Dupin et al. 2018). Furthermore, we herein showed that FGF2 stimulated the proliferation of NCCs positives to HNK1 consistent with its effects in multipotent NC progenitors (Bittencourt et al. 2013). In contrast, however, Kalcheim (1989) reported the effects of the growth factor in the survival, but not proliferation of HNK1-positive quail NCCs that displayed a flat and polygonal morphology (Kalcheim 1989), very different from the classical NC fibroblast-like morphology of the HNK1-positive cells found in our cultures. Differences in the concentration of FGF2 (10 ng/mL present study versus 10 pg/mL to 1 ng/mL in the previous study) could explain the divergent results.

The above data are in agreement with the study of Bittencourt et al. (2013), who suggested that FGF2 maintains NCCs in an undifferentiated and proliferative state and that the replacement of the growth factor by an inductive condition is required for their differentiation (Bittencourt et al. 2013). Similarly, Garcez et al. (2009) showed that FGF2 treatment of NCCs at primary culture during migration from neural tube, followed by secondary culture in inductive differentiating medium, resulted in increased number of SMP-positive Schwan cells without affect melanin-positive melanocytes (Garcez et al. 2009). Hereupon, and considering that Sox10, HNK1, and FoxD3 are involved in glial and melanocytic differentiation of NC (Calloni et al. 2009; Thomas and Erickson 2009; Harris et al. 2013; Nitzan et al. 2013b; Aquino and Sierra 2018), we evaluated if FGF2 treatment could affect the expression of these types of cells. In fact, in the presence of the growth factor, increased proportion of NCCs positives to Mitf, an earlier marker of melanoblast lineage and essential for melanogenesis (Levy et al. 2006), was recorded. Moreover, increased proportion of Mitf and BrdU double positive cells was also observed, indicating the FGF2 action in the commitment of NC to melanocytic fate and proliferation of melanoblasts. Next, experiments in which the 72 h of FGF2 treatment at secondary cultures was followed by a 48-h period in differentiating inductive medium to promote NCC differentiation (Garcez et al. 2009; Bittencourt et al. 2013) were performed. Therefore, enhanced amount of melanin pigment and increased proportion of melanin-positive melanocytes were obtained corroborating the previous finding and further suggesting the FGF2 effects in the melanocytic commitment of NCCs. No alteration, however, in the expression of SMP immunofluorescence was detected. Since melanocytes and Schwann cells are originated by the same progenitors in NC hierarchy (Lahav et al. 1998; Trentin et al. 2004), our results show the importance of the time window and the stage of development for the growth factor action in NCC differentiation.

In conclusion, our study brings new insight to the effects of FGF2 signaling on the control of NCC proliferation, survival, and differentiation, particularly in the melanocytic commitment of NCC and melanoblast proliferation. Peripheral Schwann cells from sciatic nerve were reported to adopt a melanocytic cell fate upon injury, resulting in ectopic pigmentation of the transected nerve (Rizvi et al. 2002; Adameyko et al. 2009) and after treatment with endothelin-3 (Dupin et al. 2000). In addition, Schwann cells exposed to appropriate culture conditions can be reprogrammed to multipotency and generate pigmented cells in vitro (Dupin et al. 2003; Widera et al. 2011). In this sense, FGF2 signaling could modulate, or even switch, cell specification with potential clinical applications for neurocutaneous diseases characterized by pigmentation disorders associated with abnormalities in the PNS (Adameyko and Lallemend 2010), as well as melanoma cancer research. Understanding the role and mechanism associated with the effects of FGF2 on the initial differentiation of the NC progenitors including the melanocytic commitment is crucial for a future clinical application of this knowledge in pathologies associated with melanocytes and pigmentation disorders.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Inovação/Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (MCTI/CNPq/Brazil), Grants 465656/2014-5 and 309128/2013-7 from CNPq, Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001. Bianca L. Teixeira and Diego Amarante-Silva received a fellowship from the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES, Brazil). Diego Amarante-Silva also received a fellowship from the Programa de Doutorado Sanduíche no Exterior (PDSE/CAPES) processo BEX 6793-15-0 to develop part of his PhD in the Institut de la Vision—Paris-France. We would like to thank all the staff from the Multiuser Laboratory of Biology Studies (LAMEB/UFSC) for the technical support.

Author Contributions

BLT and DAS are both first authors. BLT, DAS, RCG, and AGT: Conceived and designed the experiments. DAS, BLT, and SBV: Performed experiments. BLT, DAS, and AGT: Analyzed data. BLT, DAS, and AGT: Wrote the manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving animals were in accordance with the Animal Ethics Committee of Santa Catarina Federal University, Brazil (protocol number 6016021017).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abo T, Balch CM (1981) A differentiation antigen of human NK and K cells identified by a monoclonal antibody (HNK-1). J Immunol 127:1024–1029 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abzhanov A, Tzahor E, Lassar AB, Tabin CJ (2003) Dissimilar regulation of cell differentiation in mesencephalic (cranial) and sacral (trunk) neural crest cells in vitro. Development 130:4567–4579. 10.1242/dev.00673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adameyko I, Lallemend F (2010) Glial versus melanocyte cell fate choice: Schwann cell precursors as a cellular origin of melanocytes. Cell Mol Life Sci 67:3037–3055. 10.1007/s00018-010-0390-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adameyko I, Lallemend F, Aquino JB et al (2009) Schwann cell precursors from nerve innervation are a cellular origin of melanocytes in skin. Cell 139:366–379. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aquino JB (2017) Uncovering the in vivo source of adult neural crest stem cells. Stem Cells Dev 26:303–313. 10.1089/scd.2016.0297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aquino JB, Sierra R (2018) Schwann cell precursors in health and disease. Glia 66:465–476. 10.1002/glia.23262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittencourt DA, da Costa MC, Calloni GW et al (2013) Fibroblast growth factor 2 promotes the self-renewal of bipotent glial smooth muscle neural crest progenitors. Stem Cells Dev 22:1241–1251. 10.1089/scd.2012.0585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bressan RB, Melo FR, Almeida PA et al (2014) EGF-FGF2 stimulates the proliferation and improves the neuronal commitment of mouse epidermal neural crest stem cells (EPI-NCSCs). Exp Cell Res 327:37–47. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.05.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronner-Fraser M (1986) Analysis of the early stages of trunk neural crest migration in avian embryos using monoclonal antibody HNK-1. Dev Biol 115:44–55. 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90226-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calloni GW, Le Douarin NM, Dupin E (2009) High frequency of cephalic neural crest cells shows coexistence of neurogenic, melanogenic, and osteogenic differentiation capacities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:8947–8952. 10.1073/pnas.0903780106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coelho-Aguiar JM, Le Douarin NM, Dupin E (2013) Environmental factors unveil dormant developmental capacities in multipotent progenitors of the trunk neural crest. Dev Biol 384:13–25. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.09.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Silva B, da Costa MC, Melo FR et al (2009) Fibronectin promotes differentiation of neural crest progenitors endowed with smooth muscle cell potential. Exp Cell Res 315:955–967. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulac C, Cameron-Curry P, Ziller C, Le Douarin NM (1988) A surface protein expressed by avian myelinating and nonmyelinating Schwann cells but not by satellite or enteric glial cells. Neuron 1:211–220. 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90141-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupin E, Sommer L (2012) Neural crest progenitors and stem cells: from early development to adulthood. Dev Biol 366:83–95. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.02.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupin E, Glavieux C, Vaigot P, Le Douarin NM (2000) Endothelin 3 induces the reversion of melanocytes to glia through a neural crest-derived glial-melanocytic progenitor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:7882–7887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupin E, Real C, Glavieux-Pardanaud C et al (2003) Reversal of developmental restrictions in neural crest lineages: transition from schwann cells to glial-melanocytic precursors in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:5229–5233. 10.1073/pnas.0831229100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupin E, Calloni GW, Coelho-Aguiar JM, Le Douarin NM (2018) The issue of the multipotency of the neural crest cells. Dev Biol. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2018.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcez RC, Teixeira BL, Schmitt SDS et al (2009) Epidermal growth factor (EGF) promotes the in vitro differentiation of neural crest cells to neurons and melanocytes. Cell Mol Neurobiol 29:1087–1091. 10.1007/s10571-009-9406-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halaban R, Ghosh S, Baird A (1987) bFGF is the putative natural growth factor for human melanocytes. Vitro Cell Dev Biol 23:47–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall BK (2009) The neural crest and neural crest cells in vertebrate development and evolution. Springer, US, Boston, MA [Google Scholar]

- Harris ML, Buac K, Shakhova O et al (2013) A dual role for SOX10 in the maintenance of the postnatal melanocyte lineage and the differentiation of melanocyte stem cell progenitors. PLoS Genet 9:e1003644. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirobe T, Shinpo T, Higuchi K, Sano T (2010) Life cycle of human melanocytes is regulated by endothelin-1 and stem cell factor in synergy with cyclic AMP and basic fibroblast growth factor. J Dermatol Sci 57:123–131. 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2009.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochgreb-Hägele T, Bronner ME (2013) A novel FoxD3 gene trap line reveals neural crest precursor movement and a role for FoxD3 in their specification. Dev Biol 374:1–11. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.11.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalcheim C (1989) Basic fibroblast growth factor stimulates survival of nonneuronal cells developing from trunk neural crest. Dev Biol 134:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Lo L, Dormand E, Anderson DJ (2003) SOX10 maintains multipotency and inhibits neuronal differentiation of neural crest stem cells. Neuron 38:17–31. 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00163-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota Y, Ito K (2000) Chemotactic migration of mesencephalic neural crest cells in the mouse. Dev Dyn 217:170–179. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(200002)217:2%3c170:AID-DVDY4%3e3.0.CO;2-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlbrodt K, Herbarth B, Sock E et al (1998) Sox10, a novel transcriptional modulator in glial cells. J Neurosci 18:237–250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahav R, Dupin E, Lecoin L et al (1998) Endothelin 3 selectively promotes survival and proliferation of neural crest-derived glial and melanocytic precursors in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:14214–14219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Douarin N, Kalcheim C (1999) The neural crest. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge [Google Scholar]

- Levy C, Khaled M, Fisher DE (2006) MITF: master regulator of melanocyte development and melanoma oncogene. Trends Mol Med 12:406–414. 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier F, Caroli U, Satyamoorthy K et al (2003) Fibroblast growth factor-2 but not Mel-CAM and/or beta3 integrin promotes progression of melanocytes to melanoma. Exp Dermatol 12:296–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy M, Reid K, Ford M et al (1994) FGF2 regulates proliferation of neural crest cells, with subsequent neuronal differentiation regulated by LIF or related factors. Development 120:3519–3528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi K, Chan YS, Ito K (2007) Notch signaling is required for the chondrogenic specification of mouse mesencephalic neural crest cells. Mech Dev 124:190–203. 10.1016/j.mod.2006.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesbit M, Nesbit HK, Bennett J et al (1999) Basic fibroblast growth factor induces a transformed phenotype in normal human melanocytes. Oncogene 18:6469–6476. 10.1038/sj.onc.1203066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitzan E, Krispin S, Pfaltzgraff ER et al (2013a) A dynamic code of dorsal neural tube genes regulates the segregation between neurogenic and melanogenic neural crest cells. Development 140:2269–2279. 10.1242/dev.093294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitzan E, Pfaltzgraff ER, Labosky PA, Kalcheim C (2013b) Neural crest and Schwann cell progenitor-derived melanocytes are two spatially segregated populations similarly regulated by Foxd3. Proc Natl Acad Sci 110:12709–12714. 10.1073/pnas.1306287110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ota M, Ito K (2006) BMP and FGF-2 regulate neurogenin-2 expression and the differentiation of sensory neurons and glia. Dev Dyn 235:646–655. 10.1002/dvdy.20673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizvi TA, Huang Y, Sidani A et al (2002) A novel cytokine pathway suppresses glial cell melanogenesis after injury to adult nerve. J Neurosci 22:9831–9840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar S, Petiot A, Copp A et al (2001) FGF2 promotes skeletogenic differentiation of cranial neural crest cells. Development 128:2143–2152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauka-Spengler T, Bronner-Fraser M (2008) A gene regulatory network orchestrates neural crest formation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 9:557–568. 10.1038/nrm2428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer L (2018) Developmental Biology of Melanocytes. In: Fisher DE, Bastian BC (eds) Melanoma. Springer, New York, pp 1–17 [Google Scholar]

- Stocker KM, Sherman L, Rees S, Ciment G (1991) Basic FGF and TGF-beta 1 influence commitment to melanogenesis in neural crest-derived cells of avian embryos. Development 111:635–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swope VB, Medrano EE, Smalara D, Abdel-Malek ZA (1995) Long-term proliferation of human melanocytes is supported by the physiologic mitogens alpha-melanotropin, endothelin-1, and basic fibroblast growth factor. Exp Cell Res 217:453–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AJ, Erickson CA (2009) FOXD3 regulates the lineage switch between neural crest-derived glial cells and pigment cells by repressing MITF through a non-canonical mechanism. Development 136:1849–1858. 10.1242/dev.031989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trentin A, Glavieux-Pardanaud C, Le Douarin NM, Dupin E (2004) Self-renewal capacity is a widespread property of various types of neural crest precursor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:4495–4500. 10.1073/pnas.0400629101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trentin AG, Garcez RC, Bressan RB (2016) Neural crest stem cell cultures: establishment, characterization and potential use. Working with stem cells. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 111–125 [Google Scholar]

- Tucker GC, Aoyama H, Lipinski M et al (1984) Identical reactivity of monoclonal antibodies HNK-1 and NC-1: conservation in vertebrates on cells derived from the neural primordium and on some leukocytes. Cell Differ 14:223–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent M, Duband JL, Thiery JP (1983) A cell surface determinant expressed early on migrating avian neural crest cells. Brain Res 285:235–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widera D, Heimann P, Zander C et al (2011) Schwann cells can be reprogrammed to multipotency by culture. Stem Cells Dev 20:2053–2064. 10.1089/scd.2010.0525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J-M, Hoffmann R, Sieber-Blum M (1997) Mitogenic and anti-proliferative signals for neural crest cells and the neurogenic action of TGF-β1. Dev Dyn 208:375–386. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199703)208:3%3c375:AID-AJA8%3e3.0.CO;2-F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]