Abstract

In the present study, the functional role of the inwardly rectifying K+ channel, Kir4.1, and large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BK) channel during cell migration in U251 cell line was investigated. We focused on polarised cells which are positive for the active-Cdc42 migration marker. The perforated patch technique was used to avoid intracellular dialysis and to maintain physiological changes in intracellular calcium. Wound healing was employed to assay migration after 24 h. Polarised cells recorded displayed different hallmarks of undifferentiated glial cells: depolarised resting membrane potential and high membrane resistance. Cells recorded outside wounded area did not display either constitutive inward or outward rectification. After migration, U251 cells were characterised by a constitutively smaller Kir4.1 and larger BK currents with a linearly related amplitude. Menthol modulation increased both currents in a linearly dependent manner, indicating a common mechanism triggered by activation of transient receptor potential melastatin 8 (TRPM8), a Ca2+-permeable non-selective cation channel. We hypothesised that both migration and menthol modulation would share an increase of intracellular calcium triggering the increase in Kir4.1 and BK channels. Immunocytochemistry demonstrated the cytoplasmic expression of both Kir4.1 and BK channels and a mislocation in the nucleus under basal conditions. Before and after migration, polarised cells increased the expression of Kir4.1 and BK channels both in the cytoplasm and nucleus. TEM ultrastructural analysis displayed a different nuclear distribution of Kir4.1 and BK channels. In the present study, the physiological role of Kir4.1 and BK currents at membrane potential, their involvement in migration, and the functional role of nuclear channels were discussed.

Keywords: Glioblastoma, Inward rectifier, Outward rectifier, TRPM8, Perforated patch clamp, U251

Introduction

Most primary brain tumours in adult humans arise from glial cells. These neoplasms carry a very poor prognosis largely due to the diffuse invasiveness into normal brain that prevents successful surgical treatment (Ransom 2000; Holland 2001; Maher et al. 2001). The incidence of this type of brain tumour is increasing more and more, but no effective therapeutic strategies are available until now, mainly because the mechanisms underlying invasiveness in glioblastoma (GBM) remain largely unknown.

One of the main functions of glial cells in the brain is to maintain ionic homeostasis during neuronal activity via the potassium spatial buffering process that involves a specific subset of K+ channels known as inwardly rectifying K+ (or Kir) channels (Butt and Kalsi 2006; Olsen and Sontheimer 2008; Chever et al. 2010; Nwaobi et al. 2016; Thuringer et al. 2017). In particular, the barium-sensitive Kir4.1 encoded by the gene KCNJ10 is a prominent feature and key regulator of mature astrocytes. A reduced expression of Kir4.1 channels was detected in human brain tumours including astrocytomas and oligodendrogliomas (Olsen and Sontheimer 2004; Warth et al. 2005; Higashimori and Sontheimer 2007; Zurolo et al. 2012; Thuringer et al. 2017).

GBM cell migration has been shown to heavily depend on ion channel activity (Catacuzzeno et al. 2011). Ion channels may contribute to the invasive behaviour by influencing salt and water movements between intracellular and extracellular compartments during shape and volume changes (Soroceanu et al. 1999). The large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BK) channels and the volume-regulated Cl (IClVol) channels, both largely expressed in GBM cells, have been shown to underlay migration and enhance tumour progression in several experimental tumour models (Ransom and Sontheimer 2001; McFerrin and Sontheimer 2006). The intracellular Ca2+ concentration [Ca2+]i is involved in invasiveness, but the intracellular mechanisms targeted by [Ca2+]i changes are not well understood (Catacuzzeno et al. 2011). Menthol is a TRPM8 agonist that stimulates influx of Ca2+, BK channels membrane currents, and migration in human glioma DBTRG cells (Wondergem et al. 2008; Wondergem and Bartley 2009). Furthermore, the expression levels of TRPM8 are positively correlated with the migration and invasion of human glioblastoma U251 cells (Zeng et al. 2019).Thus, a thorough understanding of the functional role of Kir4.1 and BK channels involvement in cell migration alone or alongside the activation of TRPM8 could help develop new therapeutic strategies, targeting channels in the treatment of GBM. In the present study, the expression and the functional role of ion channel during cell migration was examined in vitro using the U251 cell line and a non-invasive perforated patch clamp technique.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture, Migration Assay, and Immunocytochemistry

Human U251 MG cell line (Sigma-Aldrich, Rome, Italy) was cultured in 25 cm2 flasks in Eagle’s minimal essential medium (EMEM) supplemented with 1% glutamine, 1% non-essential amino acids, 1% sodium pyruvate, 10% foetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere (95% air/5% CO2). All cell culture reagents were purchased from Celbio s.p.a. and Euroclone s.p.a. (Pero, Milan, Italy).

For the cell migration assay, U251 cells were seeded on glass coverslips (22 mm × 22 mm) located in cell culture dishes (35 mm × 10 mm) until 90% of confluence for immunocytochemistry measures at basal. A disposable pipette tip (1-mL volume) was used to scratch wounds on the midline of the coverslip (width 800 μm). At 24 h after the wound healing assay (t1), the width was reduced to about the fifty percent. The effect of the pharmacological inhibition of the Kir4.1 and BK channels alone or after menthol-dependent activation of TRPM8 in wound healing assay in the presence of channels blockers after 24 h of continuous exposure to the respective single and combined treatments was investigated. We used the following concentrations: Ibtx 100 nM; Barium 1 mM; Menthol 100 µM. Each treatment condition was then examined by evaluating the percentage of scratch wound closure compared to the basal control condition.

For immunocytochemistry, a protocol previously described was used (Rangone et al. 2018; Ferrari et al. 2019). Primary and secondary antibodies employed for immunofluorescence reactions are summarised in Table 1. Images were recorded using an Olympus BX51 microscope equipped with Olympus MagniFire camera system and processed with Olympus Cell F software, to analyse mean fluorescence density per cell (mean of immunofluorescence intensity normalised on the cell surface). Three independent experiments were performed for each antibody tested (number of cells tested in each experimental condition: n = 10 flattened cells, n = 10 polarised cells).

Table 1.

Primary and secondary antibodies employed for immunofluorescence microscopy

| Primary antibody | Dilution (in PBS) | Secondary antibody | Dilution (in PBS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Actin | |||

| Alexa 594-Phalloidin (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) | 1:500 | ||

| Active-Cdc42 | |||

| Monoclonal mouse anti-active Cdc42 (BIOMOL GmbH, Hamburg, Germany) | 1:100 | Alexa 488-conjugated anti-mouse antibody (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) | 1:200 |

| PCNA | |||

| Monoclonal mouse (PC10) anti-PCNA (Abcam, Italy) | 1:200 | Alexa 488-conjugated anti-mouse antibody (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) | 1:200 |

| BK channel | |||

| Polyclonal rabbit anti-KCa1.1 (KCNMA1) (Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel) | 1:200 | Alexa 594-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) | 1:200 |

| KIR4.1 channel | |||

| Polyclonal rabbit anti-Kir4.1 (KCNJ10) (Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel) | 1:100 | Alexa 594-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) | 1:200 |

TEM Ultrastructural Analysis

Cells were grown as above described. U251 cells were harvested using mild trypsinisation (0.25% trypsin in PBS containing 0.05% EDTA) and collected by centrifugation (800 rpm for 5 min). The samples were immediately fixed with 2% formaldehyde in PBS (2 h at room temperature), centrifuged (2000 rpm for 10 min) and washed with PBS. The cell pellets were pre-embedded in 2% agar and dehydrated with increasing concentrations of ethanol (30, 50, 70, 90 and 100%). Finally, the pellets were embedded in LR-white resin (Sigma-Aldrich, Italy) and polymerised at 60 °C for 24 h.

Ultrathin sections were obtained using ultramicrotome Rechter and then placed on nickel grids. Antibodies incubation and staining procedure were previously reported (Masiello and Biggiogera, 2017). Briefly, primary antibodies, i.e. anti-BK and anti-Kir4.1 channels (Table 1), were diluted in PBS containing 0.1% BSA and 0.05% Tween 20; secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch) coupled with 6 nm-colloidal gold were diluted 1:20 in PBS.

Lastly, sections were observed under a Zeiss EM 900 transmission electron microscope operating at 80 kV, computerised through Epson Perfection 4990 Photo scanner at a resolution of 800 dpi, and then processed using the Epson Scan software.

Electrophysiological Recording and Analysis Of Inward Rectifier (IR) and Outward Rectifier (OR) Currents

Whole-cell perforated patch clamp was performed as previously described (n = 87) (Horn and Marty 1988; D'Angelo et al. 1990; Bordey et al. 2000; Rossi et al. 2006), by using Axopatch-200B (Axon Instruments) patch clamp amplifier at the output cut-off frequency of 5 kHz.

The extracellular solution contained the following: 140 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM glucose, 3 mM CaCl2 and 1.2 mM MgSO4, pH 7.4. The intrapipette solution contained 100 μg/mL Nystatin (Sigma/Fluka, Milan, Italy) and 140 mM KCl, 4 mM NaCl, 5 mM EGTA, 5 mM HEPES and 0.5 mM CaCl2, pH 7.3. Series resistance (Rs = 16 ± 1.3 MΩ), input resistance (Rm) and membrane capacitance (Cm, Table 2) were measured as previously described (Rossi et al. 1996).

Table 2.

Vm, Rm and Cm in polarised cells recorded, within the wounded area, with constitutive currents and cells after menthol perfusion

| Vm (mV) | Rm (GΩ) | Cm (pF) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constitutive (n = 46) | − 30.9 ± 1.5 | 0.72 ± 0.07 | 29.9 ± 3.2 |

| Menthol (n = 15) | − 36.1 ± 5.4 | 0.76 ± 0.22 | 43.8 ± 5.3** |

**p < 0.01

Whole-cell perforated patch clamp stability was assessed over time every 5 min by monitoring Rs. The junction potential between the pipette and cytoplasm was 8.8 mV (Horn and Marty 1988) and the I–V relationship was shifted to the left by this value.

The depolarising ramp from − 120 to + 140 mV was elicited at a rate corresponding to 0.077 mV/ms (sampling rate: 500 Hz). Other protocols are reported in the Figures. Mean amplitude was measured at − 120 mV for Kir4.1 and + 140 mV for BK.

To analyse inward rectifier (IR) and outward rectifier (OR) currents, a modified Boltzmann’s equation was used (Hille and Schwarz 1978; Rossi et al. 1998, 2006; Ransom et al. 2002; Brandalise et al. 2016) as follows:

| 1a |

| 1b |

Gmax is the maximal conductance, Vrev is the reversal potential, V1/2 is the potential at which the current is half-activated and k is the voltage dependence of activation (V−1). Once Vrev and Gmax were known, and because

it follows that

| 2a |

| 2b |

Activation time constant of Kir4.1 and BK were obtained by fitting traces with a single exponential function. The electrophysiological data were analysed using Clampfit 10.6 (Axon Instruments, Molecular Devices LLC, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and Origin 6.0 (Origin Labs, Northampton, MA, USA).

Drugs were locally perfused for about 15 min using a multi-barrel pipette positioned at 50 μm from the recorded cell.

Statistical Analysis

All data are reported as mean values ± standard error of the mean (SEM). We performed Bartlett’s and Shapiro–Wilk’s tests to establish and confirm the normality of parameters. Statistical significance was determined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Post hoc Bonferroni’s test and Student’s t test with Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

The experimental plan consisted of two experimental time points: (i) a basal condition and (ii) 24 h after wound healing assay (t1). The t1 cells within (IN) and outside (OUT) the wounded area were studied.

Flattened and Polarised Cells: Migration and Proliferation

At basal condition and t1, the actin-immunopositive cells showed two different features: a morphology characterised by polarised cytoplasmic protrusion, and a flattened one, namely polarised and flattened cells, respectively (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Actin immunostaining. The upper schematic drawing describes selected experimental conditions. Micrographs show actin-immunopositive cytoskeleton (red fluorescence), revealing different cell morphologies at basal condition and at t1 (a, c and b, d, respectively); nuclear counterstaining with Hoechst 33,258 (blue fluorescence). White arrowhead indicate polarised cells. Scale bars: 200 µm (a, b), 20 µm (c, d)

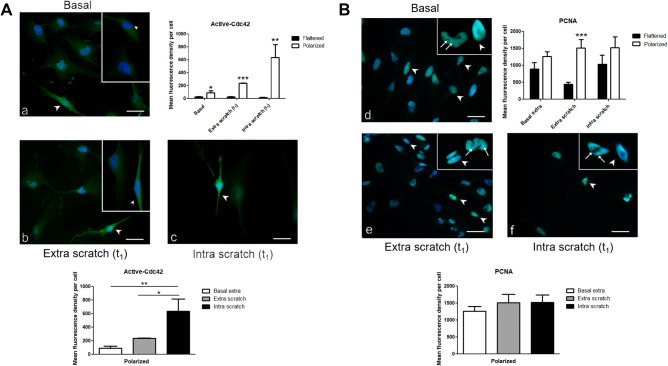

The migration marker active-Cdc42 stained U251 cell cytoplasm. In particular, immunoreactivity was enhanced in polarised cells compared with flattened ones (Fig. 2a). Notably, in polarised cells, the mean fluorescence density per cell progressively increased from basal to OUT to IN (Fig. 2Ac), whereas in flattened cells, the fluorescence was lower remaining constant (Fig. 2Aa–c).

Fig. 2.

Active-Cdc42 and PCNA immunolabelling. Micrographs show active-Cdc42 (A) and PCNA immunostaining (B), both identified by green fluorescence, in flattened and polarised cells, evaluated at basal condition (a, d) and at t1, both outside (extra scratch, b, e) and within (intra scratch, c, f) wounded area. Histograms show the mean fluorescence density per cell. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33,258 (blue fluorescence). White arrowhead indicates polarised cell; thin white arrow indicates nuclear foci with spot-like labelling in flattened cells. Scale bar: 40 μm. p values: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Anti-PCNA antibody [PC10] is specific for PCNA p36 protein, which is expressed at high levels in proliferating cells. In the nucleus, this marker forms nuclear foci that represent sites of ongoing DNA replication. These foci vary in morphology and number during the S phase (Leonhardt et al. 2000; Dellaire et al. 2006; Schönenberger et al. 2015).

We employed the proliferation marker PCNA which stained the U251 cells nuclei. No statistically significant differences were measured between flattened and polarised cells under different experimental conditions except for OUT (Fig. 2Bd–f). In detail, in polarised cells PCNA immunolabelling was homogeneously distributed in the nucleus, while in flattened cells the fluorescence appeared spot-like, indicating that these cells were actively cycling cells (Schönenberger et al. 2015).

Electrophysiological Recordings IN and OUT the Wounded Area

Polarised cells recorded IN (n = 54) and OUT (n = 33) the wounded area at t1 had a depolarised membrane potential (− 31.7 ± 1.4 mV and − 34.7 ± 1.7 mV, respectively).

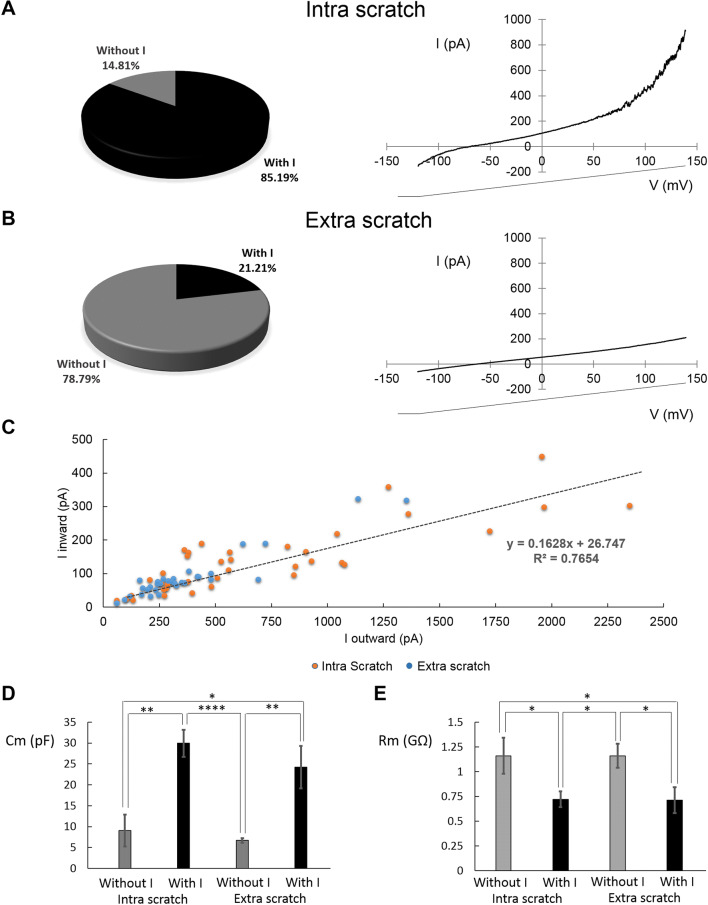

The majority of recorded cells IN the wounded area (85.19%, n = 46/54) showed both constitutive OR and IR currents (Fig. 3a), whereas the other cells did not display any currents. The majority of recorded cells OUT the wounded area (78.79%, n = 26/33) did not display OR and IR currents (Fig. 3b) and the remaining cells displayed smaller IR and OR currents (n = 7, mean amplitude − 28.4 ± 5.1 pA and 441.9 ± 81.8 pA, respectively).

Fig. 3.

Currents recorded within and outside wounded area. a, b left panels, cells percentage with or without IR and OR within (intra scratch, n = 54, a) and outside (extra scratch, n = 33, b) wounded area. a, b Right panels, averaged traces. c Relationship between IR and OR currents within (orange points) and outside (blue points) wounded area. d Membrane capacitance measured in polarised cells recorded within (n = 54) and outside (n = 33) wounded area with or without constitutively currents. p values: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001

The amplitudes of OR and IR currents were interpolated with a straight line, indicating a direct correlation (R2 = 0.7654, Fig. 3c). Cm and Rm values were associated with the presence or absence of the constitutive currents both IN and OUT the wounded area (Fig. 3d, e).

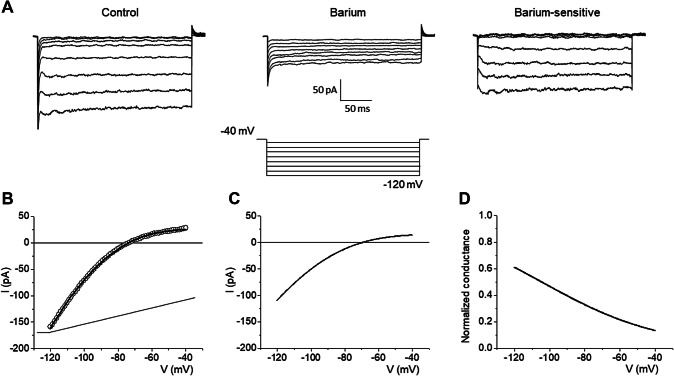

Biophysical and Pharmacological Identification of Kir4.1 and BK Channels

IR was blocked by 1 mM Ba2+ (n = 17, Fig. 4a). The averaged I–V plots and the normalised conductance curve of the barium-sensitive IR was reconstructed by Eqs. 1a and 2a and Boltzmann’s parameters are reported in Table 3 (Fig. 4b–d). IR had a weak voltage-dependent rectification and the activation time constant was about 4.8 ms. All the results identified the Kir4.1 channel (Olsen and Sontheimer 2004; Thuringer et al. 2017).

Fig. 4.

Identification of constitutively Kir4.1 within wounded area. a IR was rapidly blocked by local perfusion of 1 mM Ba2+ (n = 17, sampling rate: 6.67 kHz). The barium-sensitive currents have been obtained by digital subtraction: control-barium. b The experimental trace obtained using a voltage-ramp protocol have been fitted with Eq. 1a. cI–V plots obtained by the averaged values reported in Table 3. d Normalised conductance reconstructed using Eq. 2a

Table 3.

Biophysical properties of Kir4.1 and BK

| Gmax (nS) | Vrev (mV) | V1/2 (mV) | K (mV−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kir4.1 | ||||

| Barium-sensitive (n = 17) | 3.5 ± 0.7 | − 69.2 ± 1.1 | − 104.7 ± 7.1 | 34.4 ± 4.5 |

| Menthol-sensitive (n = 5) | 5.5 ± 0.9* | − 60.5 ± 5.1 | − 104.6 ± 5.2 | 28.7 ± 7.3 |

| BK | ||||

| TEA-sensitive (n = 28) | 5.0 ± 0.6 | − 69.6 ± 0.8 | 114.9 ± 2.9 | 14.0 ± 1.2 |

*p < 0.05

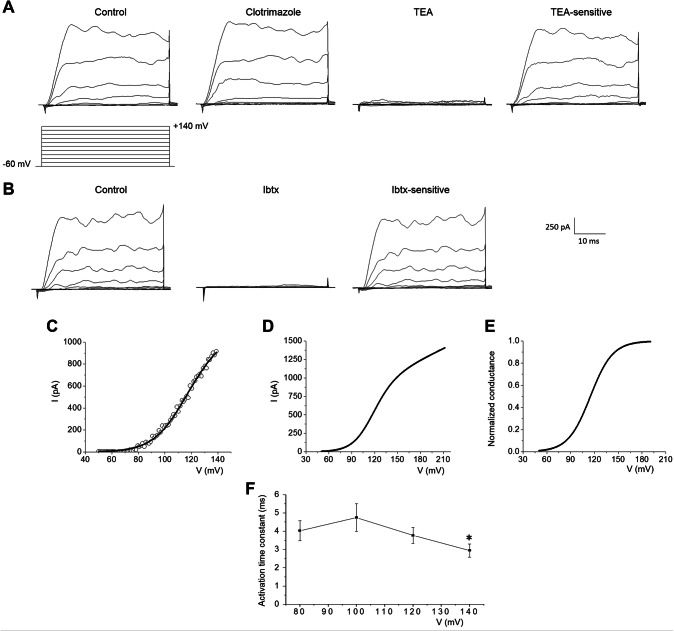

OR was insensitive to 10 µM clotrimazole but was blocked by 3 mM TEA (n = 28, Fig. 5a) and 100 nM Iberiotoxin (Ibtx; n = 3, Fig. 5b). The averaged I–V plots and the normalised conductance curve of the TEA-sensitive BK were reconstructed by Eqs. 1b and 2b and Boltzmann’s parameters are reported in Table 3 (Fig. 5c–e). The activation time constant was faster at + 140 mV (p < 0.05, Fig. 5f). All the results identified the BK channel, whereas intermediate potassium currents were negligible.

Fig. 5.

Identification of constitutively BK within wounded area. a OR rectifier currents were insensitive to local perfusion with 10 μM clotrimazole (n = 28), but was blocked in about 2 min by local perfusion with 3 mM TEA (n = 5, sampling rate: 20 kHz)). The TEA-sensitive currents have been obtained by digital subtraction: control-TEA. b OR rectifier currents were blocked in about 2 min by local perfusion with 100 nM Iberiotoxin (Ibtx) (n = 3). The Ibtx-sensitive currents have been obtained by digital subtraction: control-Ibtx. c The experimental trace obtained using a voltage-ramp protocol have been fitted with Eq. 1b. dI–V plots obtained by the averaged values reported in Table 3. e Normalised conductance reconstructed by using Eq. 2b. f Voltage dependence of the activation time constant. p values: *p < 0.05: activation time constant at + 140 mV compared with 80, 100 and 120 mV

Menthol Modulation of Kir4.1 and BK

We investigated the effect of menthol, a TRPM8 agonist, which increases [Ca2+]i, activation of BK channels, and the migration rate in human glioma cells (Wondergem et al. 2008; Wondergem and Bartley 2009).

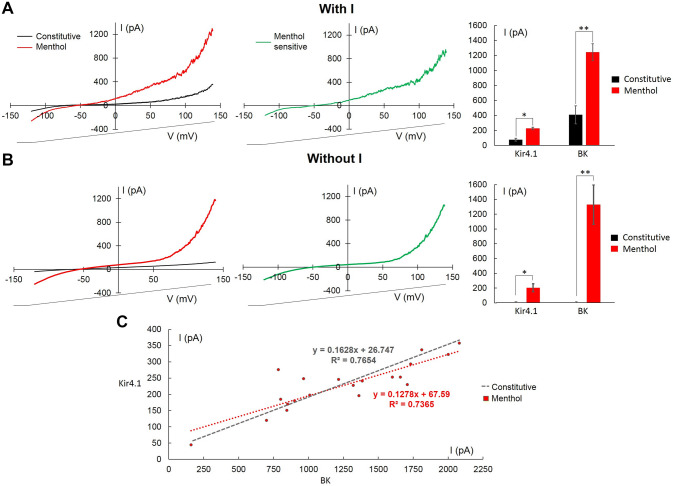

100 μM menthol was perfused at t1 for about 15 min. In all cells tested IN the wounded area, after 9 min menthol increased both Kir4.1 and BK currents. After menthol perfusion, a difference between the amplitude of both Kir4.1 and BK in cells with (n = 15) or without (n = 5) constitutive currents was not observed (Fig. 6a, b).

Fig. 6.

Menthol increased KIR4.1 and BK currents within wounded area. a, b Left: averaged traces elicited before (black), and 9 min after the beginning of local menthol perfusion (100 μM; red) in cells with (n = 15, a) and without (n = 5, b) KIR4.1 and BK. In the centre: experimental traces obtained after digital subtraction (menthol–constitutive, green). Right: summary results evaluated at − 120 mV for KIR4.1 and at + 140 mV for BK currents. c Relationship between KIR4.1 and BK after menthol perfusion (red). The straight line obtained for constitutive currents is shown for comparison (grey). p values: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01

Due to the unexpected result, menthol-sensitive Kir4.1 was further investigated using the same procedure previously described and the Kir4.1 normalised conductance was reconstructed (Table 3). Gmax was the statistically significant different single parameter when comparing menthol-sensitive and constitutive Kir4.1 (p < 0.05).

After menthol activation, data points were interpolated with a straight line, indicating a direct correlation between the Kir4.1 and BK amplitudes (R2 = 0.7365, Fig. 6c).

Menthol-induced Kir4.1 was blocked by barium (81.5% decrease, n = 4, Fig. 7a) and BK was blocked by TEA (72.1% decrease, n = 7, Fig. 7b).

Fig. 7.

Modulation of KIR4.1 and BK menthol-induced currents within wounded area. a, b Left: averaged experimental traces showing constitutive currents (black), 100 μM menthol (red), and menthol plus1 mM barium (a, blue) or menthol plus 3 mM TEA (b, violet). Right: diagram showing the effect of barium at − 120 mV (n = 4, a) and TEA at + 140 mV (n = 7, b). In diagram are reported absolute values for KIR4.1. c Averaged experimental traces showing constitutive currents obtained with [Ca2+]out 0 mM (dark blue), [Ca2+]out 0 mM plus 100 µM menthol (orange), and [Ca2+]out 3 mM plus menthol (dark red). The voltage-ramp protocol is shown at the bottom. p values: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01

The calcium dependence of BK channels is well demonstrated (Ransom et al. 2002; Wondergem and Bartley 2009), whereas the calcium dependence of KIR4.1 channels has not yet established. We carried out experiments at different [Ca2+]out to address if the Kir4.1 effect by menthol activation, through TRPM8 receptor, was due to the increase in [Ca2+]in.

Figure 7c shows that the menthol perfusion in the absence of [Ca2+]out did not have any effect on BK and Kir4.1, whereas 3 mM [Ca2+]out elicited both currents (n = 3; Fig. 7c).

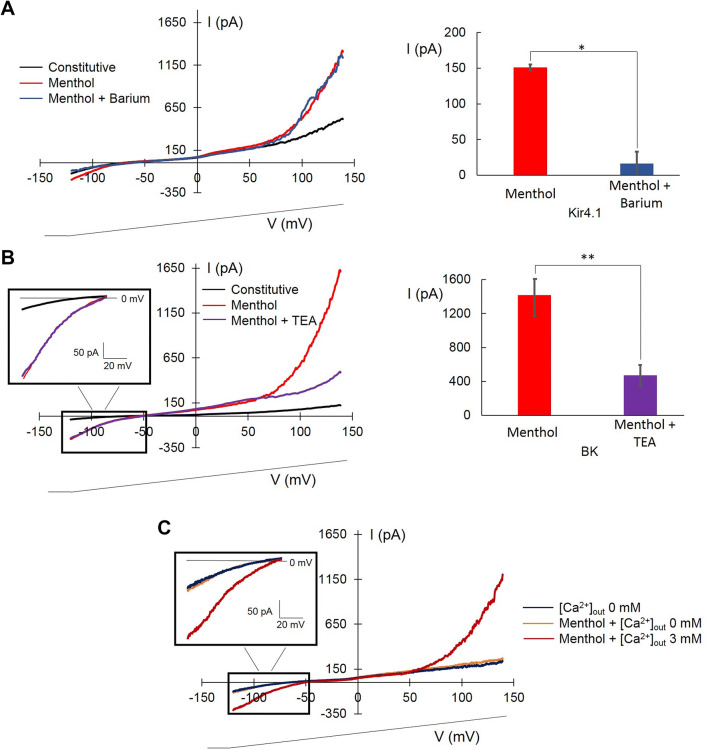

To address whether and how ionic channels influence U251 cell migration, we tested if the pharmacological inhibition of Kir and BK channels, alone or alongside the activation of TRPM8 channels by menthol, changed the percentage of scratch closure in wound healing assay. The effects were evaluated 24 h after the different experimental conditions illustrated in Fig. 8. A progressive inhibition of the migration was measured in cells exposed to Ibtx (100 nm) only and Ibtx combined with Barium (1 mM) alone or alongside the activation of TRPM8 channels by menthol (100 µm), whereas the treatment with menthol promoted migration.

Fig. 8.

Effect of the Kir4.1 and BK pharmacological inhibition on cell migration. Wound healing assay alone or alongside the activation of TRPM8 channels by menthol. Pictures after 24 h of continuous exposure in the different experimental conditions indicated in the figure. Concentrations used: Ibtx 100 nM; barium 1 mM; menthol 100 µM. The bar chart represents the analysis of scratch wound closure (%) at t1. *Statistical significance between control condition (CTR) and the other experimental conditions; #statistical significance between menthol condition and the other pharmacological experimental conditions. p values: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01

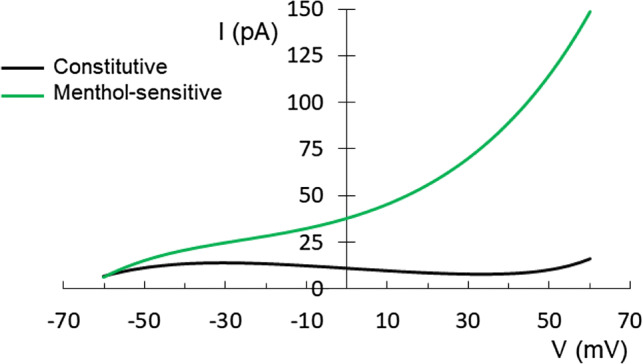

Figure 9 shows the I–V relationship closed to the Vm for constitutive and menthol-sensitive currents. In the menthol-sensitive condition, the shift on the left in the BK activation potential caused an increased leakage of potassium currents at Vm. The Vm and Cm values in cells with constitutive currents and after menthol perfusion are shown in Table 2; notably, after menthol perfusion, Cm values increased.

Fig. 9.

IV relationship at physiological membrane potential before (n = 46) and after menthol application (n = 15)

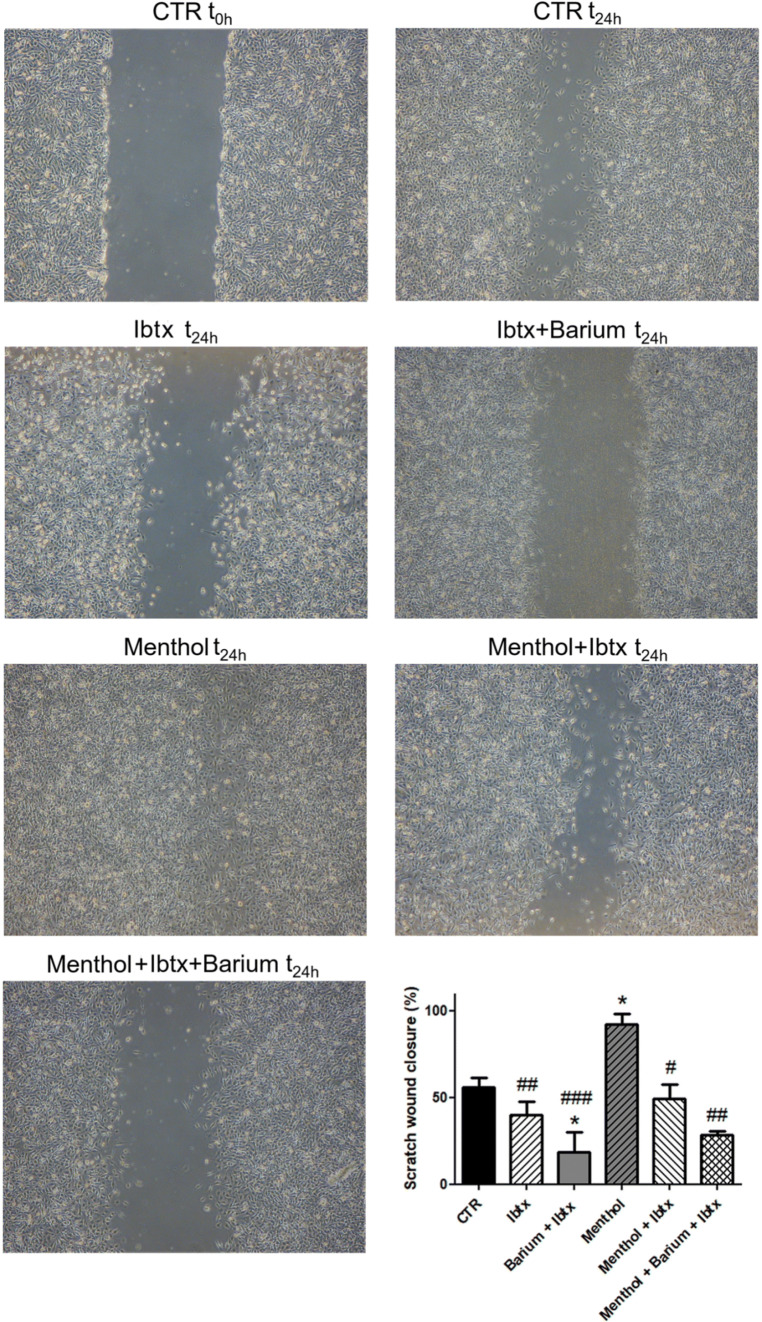

BK and Kir4.1 Immunostaining

In polarised cells, BK immunopositivity was present in both the cytoplasm and nucleus (Fig. 10a). The mean immunofluorescence density per cell was higher in the nucleus of cells OUT and IN the wounded area compared with basal condition (Fig. 10c). In the cytoplasm, a similar non-significant trend was observed.

Fig. 10.

BK and KIR 4.1 Immunofluorescence staining. Micrographs showing the immunocytochemical detection of BK (A, red fluorescence) and Kir4.1 (B, red fluorescence) in the nucleus and cytoplasm of polarised cells at basal condition (a, d) and at t1, both outside (b, e) and within (c, f) the wounded area. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33,258 (blue fluorescence). Inserts: details of BK and Kir4.1 nuclear immunoreactivity. White arrowhead indicate polarised cells. Scale bar: 40 μm. Histograms show the mean fluorescent density per cell of BK (C) and Kir4.1 (D) in nucleus and cytoplasm. *statistical significance between cells at basal condition and at t1; #statistical significance between cells at t1 within and outside wounded area. p values: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Concerning Kir4.1, the immunopositivity was detected both in the cytoplasm and nucleus (Fig. 10b). The mean fluorescence density was higher both in the cytoplasm and nucleus of cells OUT the wounded area compared with basal condition (Fig. 10d). Therefore, scratch wounding triggered the increased expression of BK and Kir4.1 in the nucleus and cytoplasm. Notably, BK and Kir4.1 immunoreactions showed higher mean nuclear fluorescence density compared with that measured for the cytoplasm.

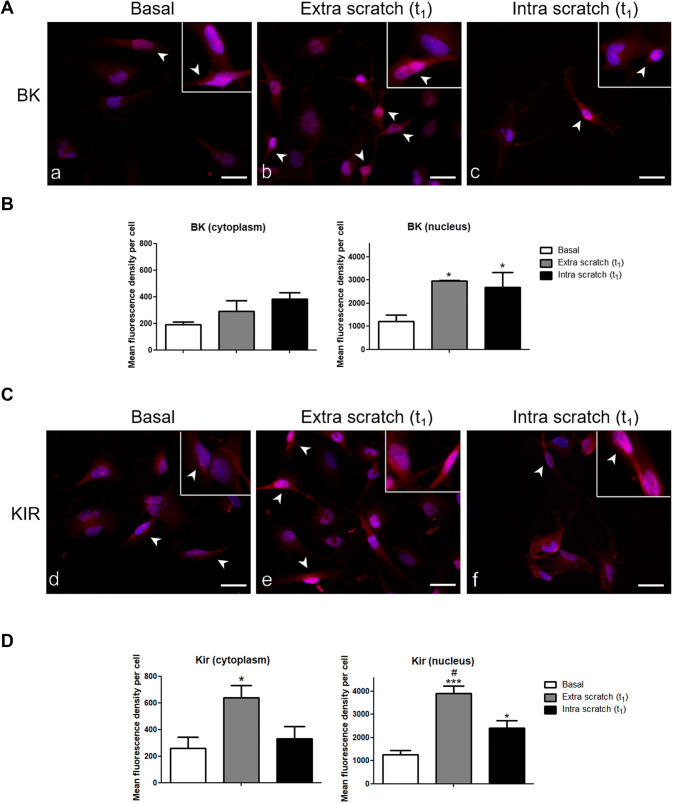

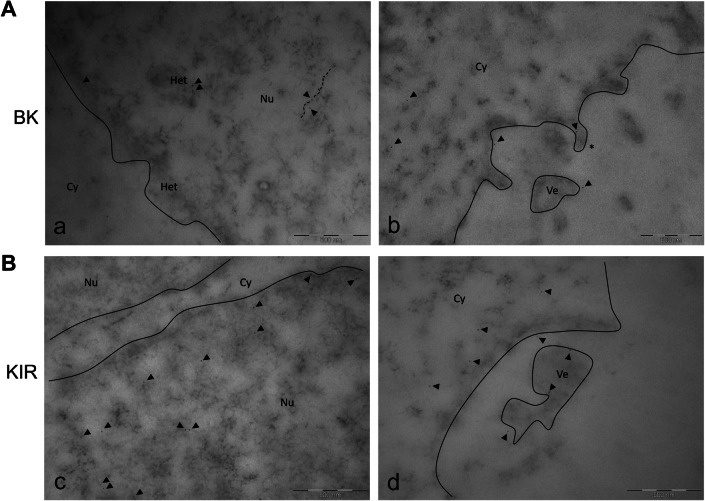

Ultrastructural Analysis of BK and Kir4.1 Localisation

The EDTA-regressive technique revealed the ultrastructural localisation of BK and Kir4.1 channels. In the nucleus, the BK labelling was mainly detected near the heterochromatin rather than euchromatin. In particular, several marked spots were observed on RNA fibrils. The labelling of BK channel was also present in the cytoplasm and near the cell membrane. BK-positive membrane protrusions were also observed (Fig. 11Ab).

Fig. 11.

TEM ultrastructural analysis (EDTA-regressive staining technique): BK and KIR 4.1 channels localization. Transmission electron microscopy images obtained by EDTA-regressive staining technique. A Micrographs showing (a) nuclear BK labelling mainly detected closed to the heterochromatinic space, compared to euchromatin, and (b) cytoplasmic BK immunopositivity present nearby the cytoplasmic membrane, membrane protrusions (asterisk), also detectable in cell vesicles. B Micrographs showing (c) KIR 4.1 immunolabelling heterogeneously localised inside the nucleoplasm, and (d) cytoplasmic KIR 4.1 staining mostly present nearby the membrane and membrane vesicle. Continuous line: nuclear membrane. Black spots: Immuno-gold labelling for BK- and KIR 4.1; gold particles dimension: 6 nm (black arrowhead). Dashed line: RNA fibrils. Cy cytoplasm, Nu nucleus, Het heterochromatin, Ve vesicle. Bars: 500 nm

Ultrastructural analysis of Kir4.1 channels displayed a more heterogeneous localisation inside the nucleoplasm compared with BK. The Kir4.1 labelling was also detected near the cytoplasmic membrane and membrane vesicle (Fig. 11Bc,d).

Discussion

In this study, the physiological roles of Kir4.1 and BK on the migration of U251 cells using perforated patch clamp recordings, immunostaining and TEM were investigated. Perforated patch technique was preferred to avoid rundown of macroscopic currents, such as Kir4.1 currents, and to leave [Ca2+]i free to change physiologically. To the best of our knowledge, this the first time the U251 cell line was studied under these physiological conditions.

Polarised cells resulted positive for active-Cdc42, a migration marker, and the immunopositivity progressively increased from basal to OUT to IN, whereas flattened cells were negative for active-Cdc42 immunostaining. Furthermore, in flattened cells we observed a spotted-like PCNA immunolabelling, whereas in polarised ones we observed a homogeneous staining, corroborating the “go-or-grow” phenotypic switch of GBM cells, a phenomenon described for brain tumours, where migration and proliferation are mutually exclusive behaviours (Hatzikirou et al. 2012). According to this hypothesis polarised cells exit the cell cycle and migrate, while flattened ones are actively cycling cells. Therefore, our focus was on polarised cells using the wound healing assay as a model of migration, and recording cells IN and OUT the wounded area.

Depolarised Vm and high Rm values in cells recorded IN and OUT the wounded area confirmed the undifferentiated state of these cells, indicating a low functional state of IR channels (Turner and Sontheimer 2014). In fact, the majority of U251 polarised cells recorded OUT the wounded area did not display either constitutive IR, confirming previous data (Olsen and Sontheimer 2008; Bordey et al. 2000; Bordey and Sontheimer 1998), or OR. Conversely, the majority of U251 migrated cells showed constitutively small IR and larger OR. Based on the pharmacological profile, biophysical features and immunocytochemistry, these currents were characterised as Kir4.1 and BK (Rosa et al. 2017). The data indicate the migration induced a functional activation of Kir4.1 and BK currents with amplitudes linearly related. A common mechanism triggering BK and Kir4.1 could be the increase in [Ca2+]i that appears to be a conserved feature among migratory cells.

We tested our calcium hypothesis, by perfusing menthol, a TRPM8 agonist. Menthol perfusion IN the wounded area increased Kir4.1 and BK. The amplitude reached the same value in cells with and without constitutive currents, indicating TRPM8 activation and the consequent [Ca2+]i elevation (Catacuzzeno et al. 2015), could reach a similar effect despite the difference in constitutive currents. The pharmacological block of BK and Kir41 channels, alone or alongside the activation of TRPM8 channels by menthol, inhibited the migration of U251 cells in wound healing assay demonstrating a direct role of these channels. In particular, the comparison between the inhibition induced by Ibtx alone and the inhibition caused by Ibtx combined with Barium demonstrated a direct role of both channels in migration process.

The calcium dependence of BK channels is well established and described by an increase in frequency and probability of channels to open (Ransom et al. 2002; Wondergem and Bartley 2009). However, data regarding the calcium dependence of KIR4.1 channels have not been published to date. It is feasible that a calcium-dependent mechanism caused the recruitment from the nucleus to the cell surface of Kir4.1, as suggested by nuclear compared to cytoplasm expression in immunocytochemistry, by the length of time required for the menthol effect in electrophysiological experiments (about 9 min), and by the electrophysiological experiments with different [Ca2+]out.

Due to the weak rectification of Kir4.1, a small K+ leaky current (approximately 15 pA) was present at Vm, whereas after TRPM8 activation, the shift of the BK threshold at a more negative potential, probably caused by the increase of [Ca2+]i (Barrett et al. 1982), elicited a greater increase of the leaky K+ current.

Surprisingly, the amplitude of Kir4.1 and BK in migrated cells and after menthol perfusion displayed a linear relationship, indicating the increase in [Ca2+]i is a common molecular mechanism.

It should be noted that the expression of Kir4.1 channels was significantly reduced in U251 cells in all tested experimental conditions compared to the expression observed in normal astrocytes in physiological condition (Higashimori and Sontheimer 2007), in which Kir4.1 channels determine a more negative resting membrane potential. Therefore, only a small number of Kir4.1 channels were functionally active IN the wounded area, also after TRPM8 menthol activation.

The immunolabelling of BK and Kir4.1 channels was evident both in the cytoplasm and nucleus of GBM cells. The immunofluorescence density in the cytoplasm and nucleus was lower in the basal condition, however, was increased OUT and IN the wounded area. These data indicated that the scratch wounding was necessary and sufficient for triggering the expression of BK and Kir4.1 in the nucleus and cytoplasm. Furthermore, the immunofluorescence density IN and OUT the wounded area was comparable, indicating channels expression both in migrated and non-migrated cells. Therefore, cells OUT the wounded area expressed Kir4.1 and BK; however, both channels were not in a functional state. In particular, Kir4.1 immunolabelling in the cytoplasm was present near the membrane and in membrane vesicles, whereas BK channels were also present in several protrusions.

TEM ultrastructural analysis revealed a heterogeneous labelling of Kir4.1 inside the nucleoplasm as previously described in D54MG (Olsen and Sontheimer 2004). Regarding BK immunostaining in the nucleosome (Li et al. 2014), the labelling was mainly detected close to the heterochromatin compared with euchromatin, suggesting a possible involvement of BK channels in chromatin remodelling.

In addition, data regarding the higher membrane capacitance value recorded in cells without currents (9 pF), with currents (29.9 pF) and after menthol modulation (43.8 pF) were intriguing. Thus, concerning migrated cells, we formulated the hypothesis that either gap junctions or larger lamellipodia, plasmatic actin-rich protrusions that contribute to cell migration and invasion (Abe et al. 2019), became electronically accessible to the patch clamp.

Conclusion

The present study provides new insights on the physiological role and modulation of BK and Kir4.1 in U251 cells. Migrated cells displayed functional BK and a residual Kir4.1. K+ leakage was present at the membrane potential of the cell and was exacerbated after application of menthol which modulated BK and Kir4.1, through a calcium-dependent mechanism. In two experimental conditions, i.e. during migration and after menthol modulation, the expression of Kir4.1 and BK channels was paired. We demonstrated the direct involvement of both BK and Kir4.1 channels in the migration, as evidences by the different wound closures percentages at t24h in the presence or the absence of channels activators or inhibitors.

The presence of nuclear Kir4.1 and BK channels was shown, further confirmed by ultrastructural analyses using TEM.

The functional role of nuclear Kir4.1 and BK channels and the menthol modulation of Kir4.1 are currently under investigation. These novel findings can aid in designing new therapeutic strategies targeting ion channels to stop the invasiveness of GBM cells in surrounding healthy tissues.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Alessandra Occhinegro, Giulia Schilardi, Eleonora Centonze, Silvia Cazzanelli, Angelo Dario Mancuso, and Maria Elena Veggi that collected preliminary results. We thank experts from BioMed Proofreading® LLC for English editing. This work was supported by the Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research (MIUR): Dipartimenti di Eccellenza Program (2018–2022) and Department of Biology and Biotechnology “L. Spallanzani”, University of Pavia, Fondo di Ricerca Giovani (FRG, University of Pavia), and crowdfunding funds.

Author’s Contributions

Study concepts and design: Paola Rossi, Maria Grazia Bottone, Elisa Roda; Data acquisition, analysis and interpretation: Daniela Ratto, Beatrice Ferrari, Stella Siciliani; Quality control of data: Paola Veneroni, Filippo Cobelli, Erica Cecilia Priori; Statistical analysis: Fabrizio De Luca, Carmine Di Iorio; Manuscript preparation: Paola Rossi, Elisa Roda, Daniela Ratto, Beatrice Ferrari; Manuscript editing: Paola Rossi, Federico Brandalise, Daniela Ratto; Manuscript review: Elisa Roda, Maria Grazia Bottone.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Daniela Ratto and Beatrice Ferrari are co-first authors.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abe T, La TM, Miyagaki Y, Oya E, Wei FY, Sumida K, Fujise K, Takeda T, Tomizawa K, Takei K, Yamada H (2019) Phosphorylation of cortactin by cyclin-dependent kinase 5 modulates actin bundling by the dynamin 1-cortactin ring-like complex and formation of filopodia and lamellipodia in NG108-15 glioma-derived cells. Int J Oncol 54:550–558. 10.3892/ijo.2018.4663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett JN, Magleby KL, Pallotta BS (1982) Properties of single calcium-activated potassium channels in cultured rat muscle. J Physiol 331:211–230. 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordey A, Sontheimer H (1998) Electrophysiological properties of human astrocytic tumor cells in situ: enigma of spiking astrocytes. J. Neurophysiol 79:2782–2793. 10.1152/jn.1998.79.5.2782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordey A, Sontheimer H, Trouslard J (2000) Muscarinic activation of BK channels induces membrane oscillations in glioma cells and leads to inhibition of cell migration. J Membr Biol 176:31–40. 10.1007/s002320001073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandalise F, Lujan R, Leone R, Lodola F, Cesaroni V, Romano C, Gerber U, Rossi P (2016) Distinct expression patterns of inwardly rectifying potassium currents in developing cerebellar granule cells of the hemispheres and the vermis. Eur J Neurosci 43:1460–1473. 10.1111/ejn.13219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt AM, Kalsi A (2006) Inwardly rectifying potassium channels (Kir) in central nervous system glia: a special role for Kir4.1 in glial functions. J Cell Mol Med 10:33–44. 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2006.tb00289.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catacuzzeno L, Aiello F, Fioretti B, Sforna L, Castigli E, Ruggieri P, Tata AM, Calogero A, Franciolini F (2011) Serum-activated K and Cl currents underlay U87-MG glioblastoma cell migration. J Cell Physiol 226:1926–1933. 10.1002/jcp.22523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catacuzzeno L, Caramia M, Sforna L, Belia S, Guglielmi L, D'Adamo MC, Pessia M, Franciolini F (2015) Reconciling the discrepancies on the involvement of large-conductance Ca(2+)-activated K channels in glioblastoma cell migration. Front Cell Neurosci 9:152. 10.3389/fncel.2015.00152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chever O, Djukic B, McCarthy KD, Amzica F (2010) Implication of Kir4.1 channel in excess potassium clearance: an in vivo study on anesthetized glial-conditional Kir4.1 knock-out mice. J Neurosci 30:15769–15777. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2078-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Angelo E, Rossi P, Garthwaite J (1990) Dual-component NMDA receptor currents at a single central synapse. Nature 346:467–470. 10.1038/346467a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellaire G, Ching RW, Dehghani H, Ren Y, Bazett-Jones DP (2006) The number of PML nuclear bodies increases in early S phase by a fission mechanism. J Cell Sci 119:1026–1033. 10.1242/jcs.02816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari B, Urselli F, Gilodi M, Camuso S, Priori EC, Rangone B, Ravera M, Veneroni P, Zanellato I, Roda E, Osella D, Bottone MG (2019) New platinum-based prodrug Pt(IV)Ac-POA: antitumour effects in rat C6 glioblastoma cells. Neurotoxicol Res. 10.1007/s12640-019-00076-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzikirou H, Basanta D, Simon M, Schaller K, Deutsch A (2012) ‘Go or Grow’: the key to the emergence of invasion in tumour progression? Math Med Biol 29:49–65. 10.1093/imammb/dqq011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashimori H, Sontheimer H (2007) Role of Kir4.1 channels in growth control of glia. Glia 55:1668–1679. 10.1002/glia.20574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B, Schwarz W (1978) Potassium channels as multi-ion single-file pores. J Gen Physiol 72:409–442. 10.1085/jgp.72.4.409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland EC (2001) Progenitor cells and glioma formation. Curr Opin Neurol 14:683–638. 10.1097/00019052-200112000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn R, Marty A (1988) Muscarinic activation of ionic currents measured by a new whole-cell recording method. J Gen Physiol 92:145–159. 10.1085/jgp.92.2.145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonhardt H, Rahn HP, Weinzierl P, Sporbert A, Cremer T, Zink D, Cardoso MC (2000) Dynamics of DNA replication factories in living cells. J Cell Biol 149:271–280. 10.1083/jcb.149.2.271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Jie W, Huang L, Wei P, Li S, Luo Z, Friedman AK, Meredith AL, Han MH, Zhu XH, Gao TM (2014) Nuclear BK channels regulate gene expression via the control of nuclear calcium signaling. Nat Neurosci 17:1055–1063. 10.1038/nn.3744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher EA, Furnari FB, Bachoo RM, Rowitch DH, Louis DN, Cavenee WK, DePinho RA (2001) Malignant glioma: genetics and biology of a grave matter. Genes Dev 15:1311–1313. 10.1101/gad.891601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masiello I, Biggiogera M (2017) Ultrastructural localization of 5-methylcytosine on DNA and RNA. Cell Mol Life Sci 74:3057–3064. 10.1007/s00018-017-2521-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFerrin MB, Sontheimer H (2006) A role for ion channels in glioma cell invasion. Neuron Glia Biol 2:39–49. 10.1017/S17440925X06000044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nwaobi SE, Cuddapah VA, Patterson KC, Randolph AC, Olsen ML (2016) The role of glial-specific Kir4.1 in normal and pathological states of the CNS. Acta Neuropathol 132:1–21. 10.1007/s00401-016-1553-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen ML, Sontheimer H (2004) Mislocalization of Kir channels in malignant glia. Glia 46:63–73. 10.1002/glia.10346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen ML, Sontheimer H (2008) Functional implications for Kir4.1 channels in glial biology: from K+ buffering to cell differentiation. J Neurochem 107:589–601. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05615.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangone B, Ferrari B, Astesana V, Masiello I, Veneroni P, Zanellato I, Osella D, Bottone MG (2018) A new platinum-based prodrug candidate: Its anticancer effects in B50 neuroblastoma rat cells. Life Sci 210:166–176. 10.1016/j.lfs.2018.08.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransom BR (2000) Glial modulation of neural excitability mediated by extracellular pH: a hypothesis revisited. Prog Brain Res 125:217–228. 10.1016/S0079-6123(00)25012-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransom CB, Sontheimer H (2001) BK channels in human glioma cells. J Neurophysiol 85:790–803. 10.1152/jn.2001.85.2.790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransom CB, Liu X, Sontheimer H (2002) BK channels in human glioma cells have enhanced calcium sensitivity. Glia 38:281–291. 10.1002/glia.10064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa P, Sforna L, Carlomagno S, Mangino G, Miscusi M, Pessia M, Franciolini F, Calogero A, Catacuzzeno L (2017) Overexpression of large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels in human glioblastoma stem-like cells and their role in cell migration. J Cell Physiol 232:2478–2488. 10.1002/jcp.25592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi P, D’Angelo E, Taglietti V (1996) Differential long-lasting potentiation of the NMDA and non-NMDA synaptic currents induced by metabotropic and NMDA receptor coactivation in cerebellar granule cells. Eur J Neurosci 8:1182–1189. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1460–9568.1996.tb01286.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi P, De Filippi G, Armano S, Taglietti V, D'Angelo E (1998) The weaver mutation causes a loss of Inward Rectifier current regulation in premigratory granule cells of the mouse cerebellum. J Neurosci 18:3537–3547. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-10-03537.1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi P, Mapelli L, Roggeri L, Gall D, de Kerchove DA, Schiffmann SN, Taglietti V, D'Angelo E (2006) Inhibition of constitutive inward rectifier currents in cerebellar granule cells by pharmacological and synaptic activation of GABA receptors. Eur J Neurosci 24:419–432. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04914.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schönenberger F, Deutzmann A, Ferrando-May E, Merhof D (2015) Discrimination of cell cycle phases in PCNA-immunolabeled cells. BMC Bioinform 16:180. 10.1186/s12859-015-0618-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soroceanu L, Manning TJ Jr, Sontheimer H (1999) Modulation of glioma cell migration and invasionusing Cl− and K+ ion channel blockers. J Neurosci 19:5942–5954. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-14-05942.1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thuringer D, Chanteloup G, Boucher J, Pernet N, Boudesco C, Jego G, Chatelier A, Bois P, Gobbo J, Cronier L, Solary E, Garrido C (2017) Modulation of the inwardly rectifying potassium channel Kir4.1 by the pro-invasive miR-5096 in glioblastoma cells. Oncotarget 8:37681–37693. 10.18632/oncotarget.16949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner KL, Sontheimer H (2014) Cl and K channels and their role in primary brain tumour biology. Phil Trans R Soc 369:20130095. 10.1098/rstb.2013.0095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warth A, Mittelbronn M, Wolburg H (2005) Redistribution of the water channel protein aquaporin-4 and the K+ channel protein Kir4.1 differs in low- and high-grade human brain tumors. Acta Neuropathol 109:418–426. 10.1007/s00401-005-0984-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wondergem R, Bartley JW (2009) Menthol increases human glioblastoma intracellular Ca2+, BK channel activity and cell migration. J Biomed Sci 16:90. 10.1186/1423-0127-16-90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng J, Wu Y, Zhuang S, Qin L, Hua S, Mungur R, Pan J, Zhu Y, Zhan R (2019) Identification of the role of TRPM8 in glioblastoma and its effect on proliferation, apoptosis and invasion of the U251 human glioblastoma cell line. Oncol Rep 42:1517–1526. 10.3892/or.2019.7260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurolo E, de Groot M, Iyer A, Anink J, van Vliet EA, Heimans JJ, Reijneveld JC, Gorter JA, Aronica E (2012) Regulation of Kir4.1 expression in astrocytes and astrocytic tumors: a role for interleukin-1 beta. J Neuroinflammation 9:280. 10.1186/1742-2094-9-280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]