Abstract

Neurodegenerative diseases (NDs) are age-dependent; among them, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD) are the most frequent. Similarly, cerebrovascular damage can induce the development of vascular-related disorders that share common features with AD and PD, respectively, named vascular dementia (VD) and vascular parkinsonism (VP). To date, ND diagnosis is mainly clinical; therefore, since these disorders show similar symptoms, their correct discrimination may be difficult. We detected 23 ND-associated microRNAs (miRNAs) by literature mining and investigated their serum expression in a cohort of 139 patients including AD, PD, VD, and VP patients and healthy controls. TaqMan RT-PCR data showed that miR-23a upregulation was associated with an ongoing neurodegenerative process, similar to miR-22* and miR-29a, while let-7d, miR-15b, miR-24, miR-142-3p, miR-181c, and miR-222 showed an altered expression in Parkinson-like phenotypes, as well as miR-34b, miR-125b, and miR-130b in Alzheimer-like disorders. By computing logistic regression models and ROC curves, we identified signatures of neuro-miRNAs specific for each disease, showing good diagnostic performance. Interestingly, we found that miR-23a, miR-29a, miR-34b, and miR-125b exhibited a different distribution between exosomes and vesicle-free serum, suggesting a heterogeneity of secretion for these miRNAs. Our results suggest that miRNA signatures could discriminate in a non-invasive manner neurodegenerative disorders, thus improving clinical diagnoses.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10571-019-00751-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: microRNAs, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, Vascular dementia, Vascular parkinsonism, Exosomes

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD) are the most frequent age-dependent progressive neurodegenerative disorders (NDs) of the central nervous system (CNS). The pathological mechanism inducing neuron loss in AD and PD is represented by the aggregation and accumulation of misfolded proteins, either in the intracellular or in the extracellular compartment (Bayer 2015). It has been demonstrated that the accumulation of misfolded proteins begins several years before the clinical onset of the disease, which usually appears in middle-late life, when the neurodegenerative process is already irreversible (Skovronsky et al. 2006). AD represents the most common form of dementia in individuals aged 65 years or over, with an incidence rate rising with increasing age (Jorm and Jolley 1998; Qiu et al. 2009). It is clinically characterized by the slow progressive loss of cognitive abilities, such as memory, language, executive function, and praxis abilities, leading to huge behavioral consequences and loss of self-sufficiency (Burns and Iliffe 2009; Lopez and Dekosky 2008). From a pathological point of view, AD is characterized by the extracellular deposition of amyloid-β protein (amyloid plaques) and by the intraneuronal aggregation of hyperphosphorylated tau protein (neurofibrillary tangles) (Serrano-Pozo et al. 2011). PD is the second most common neurodegenerative disease, usually affecting individuals aged 50 years or over. It is characterized by cardinal motor symptoms such as tremor at rest, rigidity, bradykinesia, and postural instability, associated with a variety of non-motor symptoms, including REM behavior sleep disorder, hyposmia, depression, constipation, cognitive impairment, and personality changes (Massano and Bhatia 2012; Jankovic 2008). It is a proteinopathy characterized by the intraneuronal accumulation of α-synuclein protein in aggregates named Lewy bodies (Olanow and Brundin 2013).

Cerebrovascular damage, characterized by the loss of the physiologic function of brain blood vessels (nutrient delivery, gas exchange, molecular crosstalk) (Iadecola 2013), can induce the development of vascular-related disorders that share common features with AD and PD, respectively, named vascular dementia (VD) and vascular parkinsonism (VP). VD can arise from several different vascular lesions (such as lacunar infarcts or strokes, microinfarcts, hemorrhages, small vessel disease), occurring in distinct areas of the brain (Series and Esiri 2012) and leading to a variety of symptoms similar to those observed in AD patients, such as psychomotor retardation, executive dysfunction, personality and mood changes, forgetfulness, and confusion (Roman et al. 1993; Smith 2017). Similarly, VP patients display symptoms similar to those observed in PD patients, including bradykinesia, gait disturbances, and postural instability, without, however, evidence of Lewy bodies (Jellinger 2008).

To date, molecular diagnosis of NDs is still under investigation. Indeed, according to currently accepted criteria, the diagnosis of AD, PD, VD, and VP is mainly clinical, supported by neuroimaging evidence and, for AD only, by cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) Aβ42, t-tau, and p-tau measurement (Blennow et al. 2001; Contrafatto et al. 2012; Mostile et al. 2016; Jack et al. 2018). However, due to the lack of reliable, specific, and non-invasive molecular markers that can definitively confirm the diagnosis in vivo and discriminate AD from VD and PD from VP, performing the correct diagnosis can be challenging (Reitz 2015; Massano and Bhatia 2012; O’Brien and Thomas 2015; Korczyn 2015). Hence, except for AD, the confirmation of the diagnosis can be provided only by post-mortem analysis of brain tissues (Venneti et al. 2011; Marsili et al. 2018; Sachdev et al. 2014). Accordingly, the need for specific non-invasive biomarkers able to diagnose neurodegenerative diseases and specifically discriminate among them is undeniable. In recent years, several studies have shown the possible application of circulating microRNAs (miRNAs) as diagnostic biomarkers in almost all diseases (Mitchell et al. 2008; De Guire et al. 2013; Tijsen et al. 2012; Mandourah et al. 2018), including neurodegenerative disorders (Mushtaq et al. 2016; Ragusa et al. 2016; Vallelunga et al. 2014). Indeed, miRNAs are stable in plasma, serum, and other body fluids, where they are shuttled into ribonucleoprotein complexes or microvesicles, which protect them from degradation (Turchinovich et al. 2011; Zhang et al. 2015). Among microvesicles, exosomes are nanometric vesicles with endocytic origin and a diameter of 40–100 nm, characteristically cup-shaped, playing a crucial role in shuttling RNA molecules to mediate cell-to-cell communication (Thery 2011). Several studies suggested the possible application of serum or plasma circulating miRNAs as diagnostic biomarkers for AD, PD, VD, and VP (Margis et al. 2011; Geekiyanage et al. 2012; Kumar et al. 2013; Khoo et al. 2012; Tan et al. 2014; Botta-Orfila et al. 2014; Vallelunga et al. 2014; Galimberti et al. 2014; Ragusa et al. 2016). Sometimes, the same miRNA has been reported as a possible biomarker for different neurodegenerative diseases. In the present study, we evaluated the expression of AD- and PD-related miRNAs in the serum of AD, PD, VD, and VP patients and healthy controls aiming to obtain a comprehensive vision of circulating neuro-miRNA expression in neurodegenerative diseases. Our final goal was to identify specific signatures of neuro-miRNAs able to diagnose neurodegenerative diseases and discriminate AD from VD and PD from VP.

Materials and Methods

Patient Recruitment and Serum Sample Processing

This study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of University of Catania; written informed consent was obtained from each study participant. A total of 139 patients were recruited at the Centro Parkinson e disordini del movimento and Centro Unità di Valutazione Alzheimer at Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria Policlinico Vittorio Emanuele (Catania, Italy). More specifically, 30 AD, 30 PD, 24 VD, and 25 VP patients were recruited. AD, PD, VD, and VP enrolled patients were diagnosed according to the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS/ADRDA) criteria, the Gelb criteria, the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association criteria, and the Zijlman criteria, respectively. Among patients with neurodegenerative diseases who received specific treatments for their clinical conditions, 12 (40%) out of the 30 AD patients were treated with disease-specific drugs (cholinesterase inhibitors, antiglutamatergic agents), while all PD patients assumed dopaminergic medications. Moreover, 30 healthy individuals, not affected by neurodegenerative diseases, were recruited as unaffected controls (CTRL). Baseline and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. Peripheral blood samples were collected in the morning in collection tubes with Serum Clot Activator and Gel Separator (BD Biosciences), as previously reported (Rizzo et al. 2015). Serum separation was performed by centrifugation at 2000×g in a Beckman J2-21 centrifuge, at 4 °C for 15’; serum supernatants were collected and centrifuged again under the same conditions to remove circulating cells or debris. Finally, serum was collected in RNase-free tubes and stored at − 80 °C until analysis.

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of study participants

| AD (n = 30) | PD (n = 30) | VD (n = 24) | VP (n = 25) | CTRL (n = 30) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men (n (%)) | 14 (46.6) | 24 (79.9) | 15 (62.5) | 16 (64.0) | 10 (33.3) |

| Age (year) | 72.6 ± 8.1 | 69.6 ± 8.0 | 76.3 ± 6.1 | 74.9 ± 6.6 | 67.9 ± 8.2 |

| Disease duration (year) | 4.8 ± 2.4 | 6.9 ± 3.6 | 5.2 ± 3.4 | 4.7 ± 3.0 | / |

| Education (year) | 6.6 ± 4.0 | 8.7 ± 4.6 | 4.5 ± 2.3 | 8.0 ± 3.7 | / |

| MMSE | 13.1 ± 5.7 | 25.9 ± 3.5 | 15.9 ± 5.3 | 24.9 ± 3.8 | / |

| UPDRS-ME score | / | 36.9 ± 14.4 | / | 35.5 ± 13.3 | / |

| HY stage | / | 2.6 ± 0.9 | / | 2.6 ± 0.7 | / |

| Hypertension (n (%)) | 17 (56.7) | 15 (50.0) | 19 (79.2) | 19 (76.0) | 10 (33.3) |

| Diabetes (n (%)) | 6 (20) | 6 (20.0) | 9 (37.5) | 7 (28) | 2 (6.7) |

| Hypercholesterolemia (n (%)) | 5 (16.7) | 6 (20.0) | 3 (12.5) | 11 (44.0) | 3 (10) |

Quantitative variables were described using mean and standard deviation

MMSE Mini-mental state examination, UPDRS Unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale; HY Hoeh–Yahr

Isolation of Exosomes from Serum Patients

To isolate serum exosomes, 400 μl of serum was mixed with 100 μl of ExoQuick (System Biosciences), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The exosome pellet was directly lysed with Qiazol Lysis Reagent (Qiagen) for total RNA isolation. The supernatant serum deprived of exosomes was collected and used for RNA isolation.

RNA Isolation

Total RNA was isolated from serum samples and serum exosomes using the miRNeasy Mini-Kit (Qiagen), according to the Qiagen supplementary protocol for total RNA isolation from serum and plasma. RNA was quantified by GenQuant pro spectrophotometer (Biochrom).

MiRNA Expression Analysis by Real-Time PCR

Through a search of the literature, 23 neuro-miRNAs, previously identified as deregulated in serum or plasma of AD, PD, VD, and VP patients, were selected for our study (Table 2); moreover, 3 miRNAs (miR-17-5p, miR-22-3p, and miR-106a-5p) were selected as endogenous controls (Vallelunga et al. 2014; Geekiyanage et al. 2012; Kumar et al. 2013). About 10 ng of total RNA isolated from serum was used to synthesize miRNA-specific cDNA by using the TaqMan microRNA Reverse Transcription Kit and TaqMan microRNA Assays (Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-Time PCRs were performed in a 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) with TaqMan Universal Master Mix II, no UNG and specific TaqMan probes (Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Differentially expressed (DE) miRNAs were identified through SDS RQ Manager 1.2 software (Applied Biosystems) by applying the method.

Table 2.

ND-related miRNAs selected from literature

| Neuro-miRNA | miRBase ID | AD | PD | VD | VP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| let-7d | hsa-let-7d-5p | Kumar et al. (2013) | |||

| miR-1 | hsa-miR-1-3p | Margis et al. (2011) | |||

| miR-9 | hsa-miR-9-5p | Geekiyanage et al. (2012), Tan et al. (2014) | |||

| miR-10b* | hsa-miR-10b-3p | Ragusa et al. (2016) | |||

| miR-15b | hsa-miR-15b-5p | Kumar et al. (2013) | |||

| miR-19b | hsa-miR-19b-3p | Botta-Orfila et al. (2014) | |||

| miR-22* | hsa-miR-22-5p | Margis et al. (2011) | |||

| miR-23a | hsa-miR-23a-3p | Galimberti et al. (2014) | |||

| miR-24 | hsa-miR-24-3p | Vallelunga et al. (2014) | Vallelunga et al. (2014) | ||

| miR-29a | hsa-miR-29a-3p | Geekiyanage et al. (2012) | Botta-Orfila et al. (2014), Margis et al. (2011) | Ragusa et al. (2016) | |

| miR-29b | hsa-miR-29b-3p | Galimberti et al. (2014), Geekiyanage et al. (2012) | |||

| miR-29c | hsa-miR-29c-3p | Botta-Orfila et al. (2014) | |||

| miR-34b | hsa-miR-34b-3p | Vallelunga et al. (2014) | |||

| miR-125b | hsa-miR-125b-5p | Galimberti et al. (2014), Tan et al. (2014) | |||

| miR-130b | hsa-miR-130b-3p | Ragusa et al. (2016) | |||

| miR-137 | hsa-miR-137-3p | Geekiyanage et al. (2012) | |||

| miR-142-3p | hsa-miR-142-3p | Kumar et al. (2013) | |||

| miR-148b | hsa-miR-148b-3p | Vallelunga et al. (2014) | Vallelunga et al. (2014) | ||

| miR-181c | hsa-miR-181c-5p | Geekiyanage et al. (2012), Tan et al. (2014) | |||

| miR-191 | hsa-miR-191-5p | Kumar et al. (2013) | |||

| miR-222 | hsa-miR-222-3p | Khoo et al. (2012) | |||

| miR-324 | hsa-miR-324-3p | Vallelunga et al. (2014) | Vallelunga et al. (2014) | ||

| miR-505 | hsa-miR-505-3p | Khoo et al. (2012) |

miRBase ID (http://www.mirbase.org/) is shown for each miRNA together with the references reporting its association with each disease

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by evaluating normality and homogeneity of variance by applying D’Agostino & Pearson omnibus normality test, Shapiro–Wilk normality test and F test with GraphPad Prism 6.1 software. According to the results, expression data analysis was performed by unpaired T test (homoscedastic or Welch corrected) or Mann–Whitney test among ΔCts calculated with respect to the endogenous controls. Similarly, correlation analysis between miRNA expression (−ΔCt values) and clinicopathological parameters was performed by computing Pearson correlation coefficient or Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. Holm–Sidak correction for multiple comparisons was applied; statistical significance was established at a p value ≤ 0.05. Univariate analysis was performed to evaluate possible associations between miRNA levels (−ΔCt values) and a specific subgroup of analysis versus a reference subgroup. Odds ratio (OR), 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and p value (two-tailed test, α = 0.05) were computed. Variables significantly associated with the outcome in the univariate analysis were then selected for the multivariate logistic regression analysis. A stepwise backward selection method of estimation for the independent variables was used, setting the significance level to 0.1. Independent variables inserted into the model were preliminary tested for collinearity. Age was included to the model as a priori confounder.

ROC Curves

To assess the diagnostic accuracy of miRNAs in differentiating patients with different pathological conditions, as well as neurodegenerative from healthy subjects, univariate ROC curves were computed through SPSS 23 and STATA 15.0 software, calculating the area under the curve (AUC) and the 95% confidence intervals. Based on these parameters, the diagnostic accuracy of each miRNA was evaluated at a specific ΔCt cut-off value detected using Youden’s method for the optimal cut-off, by calculating sensitivity and specificity, accuracy, and positive and negative predictive values. Statistical significance of ROC curves was also evaluated by the software (p value ≤ 0.05). Aiming to identify specific combinations of miRNAs discriminating different neurodegenerative phenotypes, we also performed a post-estimation analysis on obtained logistic regression models by computing ROC curve analysis, as well as calculating sensitivity and specificity and positive and negative predictive values of each predictive model.

Results

Differential Expression of miRNAs in Neurodegenerative Diseases

The expression of the 23 miRNAs was investigated in a cohort of 75 patients, consisting of 15 AD, 15 PD, 15 VD, 15 VP, and 15 CTRL. Expression fold changes and corrected p values were calculated with respect to miR-17, miR-22, and miR-106a. We considered as differentially expressed those miRNAs that showed significant corrected p values by using at least two out of three endogenous controls.

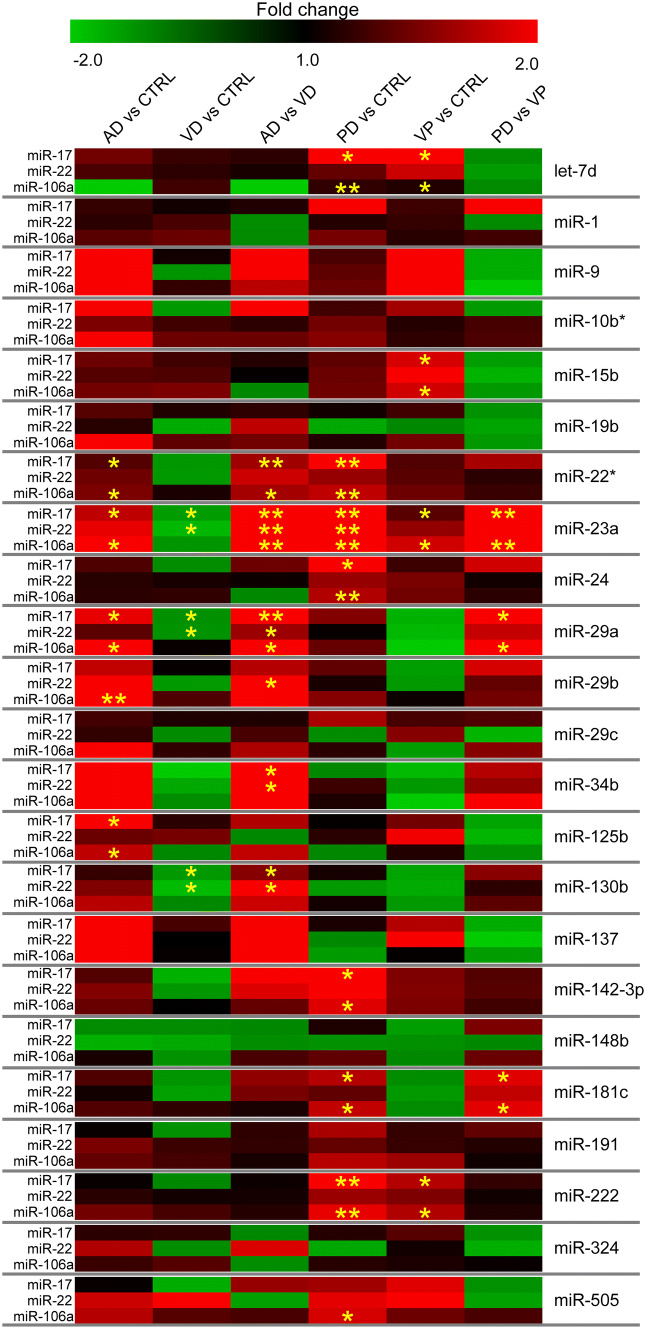

AD and VD Patients: Six (miR-22*, miR-23a, miR-29a, miR-34b, miR-125b, and miR-130b) out of the 23 miRNAs analyzed showed differential expression in the different comparisons between AD and VD patients and CTRL individuals: AD versus CTRL:miR-22*, miR-23a, miR-29a, and miR-125b; VD versus CTRL: miR-23a, miR-29a, and miR-130b; and AD versus VD: miR-22*,miR-23a, miR-29a, miR-34b, and miR-130b (Table 3, Fig. 1).

PD and VP Patients: Ten (let-7d, miR-15b, miR-22*, miR-23a, miR-24, miR-29a, miR-142-3p, miR-181c, miR-191, and miR-222) out of the 23 miRNAs analyzed showed differential expression in the different comparisons between PD and VP patients and CTRL individuals: PD versus CTRL: let-7d, miR-22*, miR-23a, miR-24, miR-142-3p, miR-181c, miR-191, and miR-222; VP versus CTRL: let-7d, miR-15b, miR-23a, and miR-222; and PD versus VP: miR-23a, miR-29a, and miR-181c (Table 4, Fig. 1).

Neurodegeneration-Associated miRNAs: We identified neurodegeneration-associated miRNAs by evaluating their expression in a single group of neurodegenerative patients (ND), obtained by grouping together AD and PD patients. This new analysis revealed that 13 out of the 23 investigated miRNAs (let-7d, miR-1, miR-9, miR-10b*, miR-15b, miR-19b, miR-22*, miR-23a, miR-24, miR-29a, miR-29b, miR-29c, miR-34b, miR-125b, miR-130b, miR-137, miR-142, miR-148b, miR-181c, miR-191, miR-222, miR-324, and miR-505) showed increased expression in the serum of neurodegenerative patients compared to unaffected individuals (Table 5).

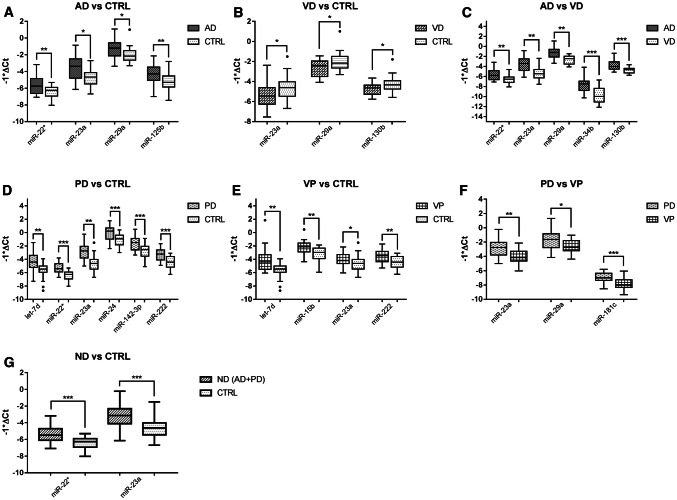

Validation of DE miRNAs: For the most significant miRNAs, we performed the expression analysis again on an enlarged cohort, consisting of 30 AD, 30 PD, 24 VD, and 25 VP patients and 30 CTRL individuals; miR-17 was used as endogenous control. Results confirmed the differential expression of all the 12 miRNAs in the analyzed comparisons (Table 6, Fig. 2). We performed an association analysis to determine which miRNAs are associated with neurodegenerative diseases, considering all the analyzed comparisons. At the univariate level, all the DE miRNAs showed significant ORs (odd ratios); in some comparisons, age was also an associated factor (AD vs. CTRL, VD vs. CTRL, VP vs. CTRL, PD vs. VP) (Table 7). All the associated factors were inserted into the stepwise multivariate logistic regression analysis (backward selection estimation, significance level for removal from the model equal to 0.1) after testing for independent variable collinearity, including age as an a priori confounder. This analysis identified miRNA signatures associated with neurodegenerative diseases in each comparison (Table 8).

Table 3.

Differential expression of miRNAs in AD, VD, and CTRL

| miRNA | AD versus CTRL | VD versus CTRL | AD versus VD | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-17 | miR-22 | miR-106a | miR-17 | miR-22 | miR-106a | miR-17 | miR-22 | miR-106a | |

| let-7d | 1.46 (0.36) | 1.3 (0.85) | − 2.33 (0.53) | 1.23 (0.65) | 1.19 (0.88) | 1.26 (0.71) | 1.18 (0.86) | 1.1 (0.88) | − 2.94 (0.92) |

| miR-1 | 1.22 (0.99) | 1.18 (0.99) | 1.35 (0.99) | 1.08 (0.99) | 1.29 (0.99) | 1.42 (0.99) | 1.13 (0.9) | − 1.09 (0.99) | − 1.05 (0.99) |

| miR-9 | 2.45 (0.53) | 2.42 (0.33) | 2.12 (0.22) | 1.07 (0.64) | − 1.2 (0.99) | 1.21 (0.76) | 2.28 (0.6) | 2.9 (0.36) | 1.75 (0.76) |

| miR-10b* | 1.99 (0.081) | 1.5 (0.41) | 2.05 (0.051) | − 1.28 (0.92) | 1.27 (0.96) | 1.43 (0.89) | 2.55 (0.11) | 1.19 (0.14) | 1.43 (0.19) |

| miR-15b | 1.44 (0.44) | 1.33 (0.94) | 1.46 (0.23) | 1.26 (0.51) | 1.31 (0.94) | 1.5 (0.23) | 1.15 (0.57) | 1.02 (0.94) | − 1.03 (0.89) |

| miR-19b | 1.35 (0.34) | 1.16 (0.89) | 2.01 (0.3) | 1.13 (0.49) | − 1.53 (0.91) | 1.38 (0.72) | 1.19 (0.49) | 1.77 (0.89) | 1.46 (0.88) |

| miR-22* | 1.33 (0.047) | 1.45 (0.43) | 1.5 (0.045) | − 1.23 (0.13) | − 1.26 (0.43) | 1.11 (0.95) | 1.65 (0.004) | 1.82 (0.081) | 1.66 (0.045) |

| miR-23a | 1.77 (0.017) | 1.93 (0.081) | 2.42 (0.009) | − 1.33 (0.048) | − 1.71 (0.046) | − 1.22 (0.13) | 2.35 (0.0006) | 2.91 (0.001) | 2.95 (0.002) |

| miR-24 | 1.31 (0.86) | 1.16 (0.95) | 1.18 (0.69) | − 1.1 (0.96) | 1.1 (0.95) | 1.2 (0.82) | 1.44 (0.86) | 1.06 (0.91) | − 1.01 (0.82) |

| miR-29a | 1.93 (0.048) | 1.37 (0.29) | 2.69 (0.038) | − 1.13 (0.049) | − 1.19 (0.048) | 1.04 (0.31) | 2.18 (0.0072) | 1.63 (0.031) | 2.6 (0.028) |

| miR-29b | 1.78 (0.065) | 2.14 (0.094) | 2.97 (0.004) | 1.03 (0.94) | − 1.28 (0.97) | 1.31 (0.92) | 1.73 (0.079) | 2.75 (0.041) | 2.26 (0.073) |

| miR-29c | 1.27 (0.095) | 1.2 (0.69) | 2.04 (0.34) | 1.13 (0.87) | − 1.07 (0.94) | 1.2 (0.86) | 1.13 (0.24) | 1.29 (0.69) | 1.7 (0.86) |

| miR-34b | 2.15 (0.12) | 2.72 (0.16) | 2 (0.07) | − 2.41 (0.45) | − 1.49 (0.71) | − 1.1 (0.66) | 5.18 (0.035) | 4.04 (0.045) | 2.2 (0.07) |

| miR-125b | 2.03 (0.049) | 1.43 (0.58) | 1.77 (0.047) | 1.18 (0.94) | 1.48 (0.99) | − 1.01 (0.95) | 1.71 (0.41) | − 1.04 (0.87) | 1.78 (0.71) |

| miR-130b | 1.22 (0.17) | 1.52 (0.61) | 1.75 (0.26) | − 1.26 (0.046) | − 1.76 (0.049) | − 1.04 (0.71) | 1.54 (0.036) | 2.67 (0.048) | 1.81 (0.11) |

| miR-137 | 2.56 (0.78) | 2.05 (0.74) | 2.2 (0.67) | 1.28 (0.95) | 1 (0.92) | 1.03 (0.97) | 2 (0.95) | 2.05 (0.92) | 2.14 (0.97) |

| miR-142-3p | 1.33 (0.17) | 1.53 (0.57) | 1.42 (0.094) | − 1.63 (0.58) | − 1.23 (0.75) | 1.01 (0.84) | 2.18 (0.12) | 1.89 (0.33) | 1.4 (0.14) |

| miR-148b | − 1.08 (0.98) | − 1.64 (0.99) | 1.1 (0.97) | − 1.07 (0.89) | − 1.5 (0.89) | − 1.18 (0.97) | − 1.01 (0.89) | − 1.08 (0.91) | 1.29 (0.97) |

| miR-181c | 1.31 (0.58) | 1.08 (0.75) | 1.32 (0.53) | − 1.2 (0.58) | − 1.37 (0.71) | 1.2 (0.92) | 1.58 (0.22) | 1.48 (0.48) | 1.1 (0.53) |

| miR-191 | 1.04 (0.42 | 1.49 (0.81) | 1.4 (0.33) | − 1.15 (0.59) | 1.24 (0.98) | 1.27 (0.64) | 1.19 (0.25) | 1.2 (0.66) | 1.1 (0.64) |

| miR-222 | 1.04 (0.36) | 1.17 (0.61) | 1.47 (0.25) | − 1.02 (0.64) | 1.08 (0.61) | 1.28 (0.61) | 1.06 (0.16) | 1.09 (0.29) | 1.15 (0.57) |

| miR-324 | 1.18 (0.9) | 1.7 (0.99) | 1.23 (0.86) | 1.19 (0.93) | − 1.1 (0.99) | 1.35 (0.86) | − 1.01 (0.94) | 1.89 (0.99) | − 1.09 (0.99) |

| miR-505 | 1.03 (0.57) | 1.81 (0.85) | 1.73 (0.36) | − 1.56 (0.88) | 2.52 (0.91) | 1.35 (0.65) | 1.61 (0.88) | − 1.39 (0.87) | 1.29 (0.89) |

For each miRNA, fold change and corrected p value (between parentheses) are shown for each endogenous control. Significant values are highlighted in bold

Fig. 1.

Expression of miRNAs in AD, VD, PD, and VP patients and unaffected participants. Expression is presented as fold change, with a color-coded scale representing downregulation in green and upregulation in red. Statistical significance is shown by yellow asterisks: *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.005, ***p ≤ 0.0005

Table 4.

Differential expression of miRNAs in PD, VP, and CTRL

| miRNA | PD versus CTRL | VP versus CTRL | PD versus VP | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-17 | miR-22 | miR-106a | miR-17 | miR-22 | miR-106a | miR-17 | miR-22 | miR-106a | |

| let-7d | 2.01 (0.019) | 1.4 (0.53) | 1.2 (0.003) | 2.21 (0.048) | 1.82 (0.18) | 1.13 (0.01) | − 1.1 (0.98) | − 1.3 (0.88) | − 1.05 (0.92) |

| miR-1 | 2.53 (0.91) | 1.15 (0.99) | 1.48 (0.85) | 1.25 (0.99) | 1.21 (0.99) | 1.17 (0.99) | 2.02 (0.8) | − 1.06 (0.99) | 1.27 (0.74) |

| miR-9 | 1.3 (0.6) | 1.38 (0.99) | 1.43 (0.76) | 2.02 (0.14) | 2.17 (0.36) | 3.08 (0.22) | − 1.56 (0.31) | − 1.57 (0.33) | − 2.16 (0.31) |

| miR-10b* | 1.27 (0.52) | 1.47 (0.98) | 1.55 (0.49) | 1.65 (0.92) | 1.15 (0.98) | 1.19 (0.89) | − 1.3 (0.92) | 1.27 (0.98) | 1.3 (0.89) |

| miR-15b | 1.38 (0.1) | 1.42 (0.94) | 1.45 (0.051) | 1.86 (0.016) | 2.36 (0.41) | 1.84 (0.013) | − 1.35 (0.57) | − 1.65 (0.59) | − 1.27 (0.65) |

| miR-19b | 1.08 (0.89) | − 1.5 (0.89) | 1.14 (0.93) | 1.26 (0.34) | − 1.04 (0.91) | 1.46 (0.88) | − 1.17 (0.34) | − 1.44 (0.54) | − 1.28 (0.88) |

| miR-22* | 2.22 (0.0006) | 1.61 (0.3) | 1.77 (0.0006) | 1.32 (0.061) | 1.36 (0.43) | 1.44 (0.14) | 1.66 (0.16) | 1.18 (0.73) | 1.23 (0.25) |

| miR-23a | 3.87 (0.0006) | 3.2 (0.0006) | 4.22 (0.0006) | 1.35 (0.048) | 1.59 (0.096) | 1.83 (0.047) | 2.86 (0.003) | 2.08 (0.05) | 2.3 (0.002) |

| miR-24 | 2.3 (0.037) | 1.61 (0.34) | 1.71 (0.0006) | 1.25 (0.14) | 1.49 (0.34) | 1.45 (0.22) | 1.84 (0.86) | 1.08 (0.95) | 1.18 (0.69) |

| miR-29a | 1.53 (0.17) | 1.03 (0.99) | 1.41 (0.29) | − 1.64 (0.11) | − 1.74 (0.29) | − 2.06 (0.13) | 2.51 (0.027) | 1.8 (0.23) | 2.9 (0.028) |

| miR-29b | 1.38 (0.49) | 1.1 (0.98) | 1.54 (0.38) | − 1.34 (0.94) | − 1.26 (0.97) | 1.05 (0.92) | 1.86 (0.49) | 1.4 (0.97) | 1.47 (0.43) |

| miR-29c | 1.69 (0.24) | − 1.08 (0.92) | 1.18 (0.86) | 1.28 (0.095) | 1.54 (0.69) | − 1.31 (0.86) | 1.32 (0.87) | − 1.67 (0.69) | 1.55 (0.86) |

| miR-34b | − 1.01 (0.85) | 1.24 (0.95) | 1.12 (0.96) | − 1.75 (0.45) | − 1.28 (0.71) | − 2.42 (0.42) | 1.72 (0.43) | 1.59 (0.71) | 2.71 (0.42) |

| miR-125b | 1.02 (0.89) | 1.17 (0.99) | 1 (0.95) | 1.47 (0.89) | 1.97 (0.99) | 1.14 (0.95) | − 1.44 (0.94) | − 1.68 (0.99) | − 1.14 (0.95) |

| miR-130b | 1.09 (0.87) | − 1.29 (0.61) | 1.08 (0.86) | − 1.43 (0.16) | − 1.53 (0.59) | − 1.27 (0.33) | 1.56 (0.16) | 1.19 (0.61) | 1.37 (0.28) |

| miR-137 | 1.11 (0.95) | − 1.04 (0.92) | − 1.29 (0.97) | 1.72 (0.95) | 2.84 (0.92) | 1.02 (0.97) | − 1.55 (0.89) | − 2.95 (0.55) | − 1.32 (0.85) |

| miR-142-3p | 2.01 (0.011) | 2.06 (0.083) | 1.9 (0.002) | 1.51 (0.17) | 1.53 (0.33) | 1.5 (0.11) | 1.32 (0.51) | 1.35 (0.75) | 1.27 (0.38) |

| miR-148b | 1.12 (0.92) | − 1.16 (0.98) | 1.39 (0.97) | − 1.34 (0.93) | − 1.13 (0.98) | − 1.03 (0.97) | 1.5 (0.98) | − 1.03 (0.95) | 1.43 (0.97) |

| miR-181c | 1.73 (0.018) | 1.39 (0.71) | 1.78 (0.036) | − 1.1 (0.72) | − 1.28 (0.75) | − 1.07 (0.89) | 1.9 (0.025) | 1.78 (0.44) | 1.91 (0.009) |

| miR-191 | 1.68 (0.019) | 1.4 (0.55) | 1.74 (0.004) | 1.21 (0.14) | 1.23 (0.55) | 1.63 (0.23) | 1.39 (0.59) | 1.14 (0.98) | 1.07 (0.63) |

| miR-222 | 2.09 (0.004) | 1.62 (0.26) | 1.93 (0.0006) | 1.72 (0.044) | 1.54 (0.24) | 1.71 (0.048) | 1.21 (0.64) | 1.07 (0.24) | 1.13 (0.61) |

| miR-324 | 1.15 (0.94) | − 1.48 (0.64) | 1.16 (0.99) | 1.35 (0.94) | 1.07 (0.99) | 1.11 (0.99) | − 1.17 (0.92) | − 1.59 (0.81) | 1.04 (0.99) |

| miR-505 | 1.65 (0.065) | 1.92 (0.78) | 1.86 (0.035) | 1.9 (0.27) | 2.67 (0.72) | 1.44 (0.27) | − 1.15 (0.88) | − 1.38 (0.91) | 1.29 (0.89) |

For each miRNA, fold change and corrected p value (between parentheses) are shown for each endogenous control. Significant values are highlighted in bold

Table 5.

Differential expression of miRNAs in ND (including both AD and PD) and CTRL

| miRNA | ND versus CTRL | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-17 | miR-22 | miR-106a | |

| let-7d | 1.69 (0.007) | 1.48 (0.18) | 1.78 (0.005) |

| miR-1 | 1.23 (0.48) | 1.07 (0.85) | 1.3 (0.52) |

| miR-9 | 1.69 (0.2) | 1.55 (0.25) | 1.87 (0.14) |

| miR-10b* | 1.53 (0.029) | 1.33 (0.26) | 1.61 (0.02) |

| miR-15b | 1.41 (0.041) | 1.23 (0.45) | 1.49 (0.014) |

| miR-19b | 1.13 (0.25) | 1 (0.97) | 1.19 (0.31) |

| miR-22* | 1.72 (0.0006) | 1.51 (0.08) | 1.82 (0.0005) |

| miR-23a | 2.78 (< 0.0001) | 2.42 (0.0009) | 2.93 (< 0.0001) |

| miR-24 | 1.54 (0.029) | 1.34 (0.24) | 1.62 (0.015) |

| miR-29a | 1.45 (0.018) | 1.27 (0.33) | 1.53 (0.034) |

| miR-29b | 1.71 (0.021) | 1.49 (0.08) | 1.8 (0.001) |

| miR-29c | 1.41 (0.008) | 1.22 (0.39) | 1.48 (0.06) |

| miR-34b | 1.46 (0.16) | 1.28 (0.24) | 1.54 (0.12) |

| miR-125b | 1.37 (0.08) | 1.2 (0.28) | 1.44 (0.12) |

| miR-130b | 1.19 (0.42) | 1.04 (0.84) | 1.26 (0.2) |

| miR-137 | 1.39 (0.62) | 1.21 (0.87) | 1.47 (0.59) |

| miR-142 | 1.76 (0.006) | 1.53 (0.036) | 1.85 (0.001) |

| miR-148b | 1.08 (0.66) | 1.06 (0.86) | 1.14 (0.54) |

| miR-181c | 1.51 (0.034) | 1.32 (0.31) | 1.59 (0.039) |

| miR-191 | 1.46 (0.026) | 1.28 (0.17) | 1.54 (0.007) |

| miR-222 | 1.65 (0.006) | 1.44 (0.14) | 1.74 (0.001) |

| miR-324 | 1.06 (0.66) | 1.08 (0.76) | 1.11 (0.57) |

| miR-505 | 1.58 (0.035) | 1.38 (0.23) | 1.67 (0.019) |

For each miRNA, fold change and p value (between parentheses) are shown for each endogenous control. Significant values are highlighted in bold

Table 6.

Validation of DE miRNAs in AD, PD, VD, VP, and CTRL

| miRNA | AD versus CTRL | VD versus CTRL | AD versus VD | PD versus CTRL | VP versus CTRL | PD versus VP | ND versus CTRL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| let-7d | 2.06 (0.002) | 2.11 (0.002) | 1.92 (0.002) | ||||

| miR-15b | 1.79 (0.001) | 1.42 (0.027) | |||||

| miR-22* | 1.43 (0.001) | 1.75 (0.001) | 1.8 (0.0004) | 1.86 (0.0004) | |||

| miR-23a | 2.37 (0.009) | − 1.78 (0.037) | 4.21 (0.0007) | 3.64 (0.0007) | 1.35 (0.037) | 2.69 (0.003) | 2.65 (0.0007) |

| miR-24 | 2.22 (0.0002) | 1.81 (0.0005) | |||||

| miR-29a | 1.94 (0.033) | − 1.21 (0.047) | 2.35 (0.002) | 2.19 (0.035) | 1.45 (0.047) | ||

| miR-34b | 5.59 (< 0.0001) | ||||||

| miR-125b | 2 (0.004) | ||||||

| miR-130b | − 1.23 (0.024) | 1.58 (0.0002) | |||||

| miR-142-3p | 2.09 (0.0002) | 1.97 (0.0002) | |||||

| miR-181c | 1.93 (0.0002) | 1.64 (0.007) | |||||

| miR-222 | 2.29 (0.0003) | 1.94 (0.0006) | 1.89 (0.0003) |

For each miRNA, fold change and corrected p value (between parentheses) are shown. MiR-17 was used as endogenous control. Significant values are highlighted in bold

Fig. 2.

Validation of differentially expressed miRNAs. Boxplots showing differential expression of miRNAs in the enlarged cohort in all the analyzed comparisons: a AD versus CTRL, b VD versus CTRL, c AD versus VD, d PD versus CTRL, e VP versus CTRL, f PD versus VP, and g ND versus CTRL. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.005, ***p ≤ 0.0005

Table 7.

Univariate association analysis of DE miRNAs for each analyzed comparison

| Comparison | miRNA | OR | 95% CIs | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADa (N = 30) versus CTRL (N = 30) | Age | 1.07 | [1–1.15] | 0.039 |

| miR-22 | 2.74 | [1.35–5.55] | 0.005 | |

| miR-23a | 1.87 | [1.19–2.92] | 0.006 | |

| miR-29a | 2.11 | [1.19–3.74] | 0.011 | |

| miR-125b | 1.88 | [1.17–3.02] | 0.009 | |

| VDa (N = 24) versus CTRL (N = 30) | Age | 1.18 | [1.06–1.31] | 0.002 |

| miR-23a | 0.57 | [0.34–0.97] | 0.037 | |

| miR-29a | 0.4 | [0.18–0.86] | 0.018 | |

| miR-130b | 0.33 | [0.12–0.91] | 0.033 | |

| ADa (N = 30) versus VD (N = 24) | Age | 0.93 | [0.86–1.01] | 0.082 |

| miR-22 | 3.1 | [1.48–6.49] | 0.003 | |

| miR-23a | 2.65 | [1.53–4.62] | 0.001 | |

| miR-29a | 4.16 | [1.83–9.46] | 0.001 | |

| miR-34b | 2.22 | [1.43–3.44] | < 0.001 | |

| miR-130b | 6.44 | [1.99–20.87] | 0.002 | |

| PDa (N = 30) versus CTRL (N = 30) | Age | 1.03 | [0.96–1.1] | 0.425 |

| let-7d | 2.16 | [1.28–3.65] | 0.004 | |

| miR-22 | 9.26 | [2.84–30.12] | < 0.001 | |

| miR-23a | 3.88 | [1.96–7.69] | < 0.001 | |

| miR-24 | 3.3 | [1.67–6.53] | 0.001 | |

| miR-1423 | 3.05 | [1.6–5.83] | 0.001 | |

| miR-222 | 4.16 | [1.94–8.9] | < 0.001 | |

| VPa (N = 25) versus CTRL (N = 30) | Age | 1.14 | [1.04–1.24] | 0.005 |

| let-7d | 2.88 | [1.45–5.72] | 0.003 | |

| miR-15b | 3.09 | [1.44–6.61] | 0.004 | |

| miR-23a | 1.8 | [1.03–3.14] | 0.04 | |

| miR-222 | 3.02 | [1.48–6.19] | 0.002 | |

| PDa (N = 30) versus VP (N = 25) | Age | 0.9 | [0.83–0.98] | 0.018 |

| miR-23a | 2.95 | [1.52–5.73] | 0.001 | |

| miR-29a | 2.22 | [1.24–3.96] | 0.007 | |

| miR-181c | 4.99 | [1.98–12.62] | 0.001 | |

| NDa (N = 60) versus CTRL (N = 30) | Age | 1.04 | [0.99–1.11] | 0.097 |

| miR-22 | 3.92 | [1.94–7.88] | < 0.001 | |

| miR-23a | 2.41 | [1.55–3.72] | < 0.001 |

MiRNA levels are expressed as −ΔCt values

The letter a identifies the group set as a case. Significant values are highlighted in bold

Abbreviations: OR: odd ratio, CIs: confidence intervals

Table 8.

Multivariate analysis by stepwise logistic regression

| Model | miRNA | adjOR | 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADa versus CTRL | Age | 1.17 | [1.05–1.32] | 0.006 |

| miR-29a | 4.09 | [1.42–11.82] | 0.009 | |

| miR-125b | 1.9 | [0.91–3.97] | 0.085 | |

| VDa versus CTRL | Age | 1.27 | [1.09–1.48] | 0.002 |

| miR-130b | 0.13 | [0.03–0.63] | 0.011 | |

| ADa versus VD | miR-23a | 3.23 | [1.67–6.21] | < 0.001 |

| PDa versus CTRL | miR-23a | 94.65 | [6.76–1325.46] | 0.001 |

| miR-24 | 0.04 | [0.003–0.52] | 0.014 | |

| VPa versus CTRL | let-7d | 2.65 | [1.08–6.53] | 0.034 |

| miR-15b | 3.27 | [1.07–10] | 0.038 | |

| PDa versus VP | Age | 0.79 | [0.68–0.93] | 0.004 |

| miR-23a | 3.58 | [0.98–13.04] | 0.053 | |

| miR-181c | 4.47 | [1.22–16.36] | 0.024 | |

| NDa versus CTRL | miR-23a | 2.7 | [1.64–4.44] | < 0.001 |

MiRNA levels are expressed as −ΔCt values. The letter a identifies the group set as a case. Significant values are highlighted in bold

adjOR adjusted odds ratio

Serum Exosomes May Contribute to miRNA Altered Expression in Neurodegenerative Diseases

To investigate if the differential expression of miRNAs in patient serum may be supported by circulating exosomes, we selected the miRNAs showing the strongest deregulation in whole serum and reanalyzed their expression in serum exosomes of a small subcohort of patients (5 patients per group). In this analysis, exosomal expression levels were compared with the expression of the same miRNAs in the serum deprived of exosomes (serum w/o exosomes); miR-17 and miR-106a were used as an endogenous control for serum w/o exosomes and serum exosomes, respectively. Results showed that deregulation of miR-23a and miR-125b was maintained only in serum w/o exosomes, while upregulation of miR-34b was observed only in serum exosomes. On the contrary, the upregulation of miR-29a was confirmed in both serum exosomes and serum w/o exosomes, but serum exosomes showed a stronger fold change and p value (Table 9).

Table 9.

Expression of DE miRNAs in exosomes isolated from serum and in serum deprived of exosomes

| Comparison | miRNA | Serum w/o exosomes | Serum exosomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| AD versus CTRL | miR-125b | 25 (0.02) | 1 (0.46) |

| AD versus VD | miR-34b | 19.7 (0.06) | 111.1 (0.009) |

| PD versus CTRL | miR-23a | 27.3 (0.01) | − 3.9 (0.07) |

| PD versus VP | miR-29a | 8.5 (0.03) | 12.5 (0.004) |

For each miRNA, fold change, p value (between parentheses), and the analyzed comparison are shown. Significant values are highlighted in bold

Evaluation of Diagnostic Performance of DE miRNAs Through ROC Curve Computation

To investigate the diagnostic accuracy of DE miRNAs as biomarkers, univariate ROC curves were computed for the 12 significant miRNAs analyzed in the enlarged cohort. Results showed statistically significant ROC curves for all 12 miRNAs in all investigated comparisons (AD vs. CTRL: miR-22*, miR-23a, miR-29a, and miR-125b; VD vs. CTRL: miR-23a, miR-29a, and miR-130b; AD vs. VD: miR-22*,miR-23a, miR-29a, miR-34b, and miR-130b; PD vs. CTRL: let-7d, miR-22*, miR-23a, miR-24, miR-142-3p, and miR-222; VP vs. CTRL: let-7d, miR-15b, miR-23a, and miR-222; and PD vs. VP: miR-23a, miR-29a, and miR-181c). For each miRNA in each specific comparison, AUC and 95% CIs were calculated; Youden’s J statistic allowed us to determine the optimal ΔCt cut-off value, whose sensitivity and specificity, accuracy, and positive and negative predictive values were calculated to assess the diagnostic performance of miRNAs as biomarkers of pathological phenotypes (Table 10).

Table 10.

Univariate ROC curve analysis

| Comparison | miRNA | AUC | Significance | 95% CIs | Cut-off | Youden index | Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy | Positive predictive value | Negative predictive value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD versus CTRL | miR-22* | 0.71 | 0.006 | 0.578–0.843 | 5.2326 | 0.367 | 0.37 | 1 | 0.68 | 1 | 0.6 |

| miR-23a | 0.71 | 0.006 | 0.576–0.845 | 3.8039 | 0.395 | 0.57 | 0.83 | 0.69 | 0.77 | 0.65 | |

| miR-29a | 0.71 | 0.005 | 0.577–0.843 | 0.8946 | 0.4 | 0.43 | 0.97 | 0.7 | 0.93 | 0.63 | |

| miR-125b | 0.71 | 0.006 | 0.577–0.844 | 4.689 | 0.392 | 0.63 | 0.76 | 0.69 | 0.73 | 0.67 | |

| VD versus CTRL | miR-23a | 0.673 | 0.033 | 0.524–0.822 | 5.7389 | 0.332 | 0.44 | 0.9 | 0.69 | 0.77 | 0.67 |

| miR-29a | 0.671 | 0.036 | 0.522–0.821 | 3.3796 | 0.318 | 0.32 | 1 | 0.71 | 1 | 0.67 | |

| miR-130b | 0.683 | 0.025 | 0.536–0.83 | 4.4214 | 0.373 | 0.77 | 0.6 | 0.67 | 0.59 | 0.78 | |

| AD versus VD | miR-22* | 0.755 | 0.002 | 0.626–0.884 | 5.8456 | 0.437 | 0.57 | 0.87 | 0.7 | 0.85 | 0.61 |

| miR-23a | 0.822 | 0.00006 | 0.709–0.935 | 4.124 | 0.58 | 0.67 | 0.91 | 0.77 | 0.91 | 0.68 | |

| miR-29a | 0.832 | 0.00005 | 0.724–0.939 | 1.6431 | 0.588 | 0.63 | 0.96 | 0.77 | 0.95 | 0.66 | |

| miR-34b | 0.812 | 0.0001 | 0.691–0.932 | 9.013 | 0.572 | 0.83 | 0.74 | 0.79 | 0.81 | 0.77 | |

| miR-130b | 0.802 | 0.0002 | 0.685–0.918 | 3.9687 | 0.455 | 0.5 | 0.96 | 0.69 | 0.94 | 0.58 | |

| PD versus CTRL | let-7d | 0.753 | 0.001 | 0.623–0.882 | 4.7301 | 0.488 | 0.62 | 0.87 | 0.75 | 0.82 | 0.7 |

| miR-22* | 0.845 | 5E−06 | 0.749–0.941 | 5.8567 | 0.56 | 0.77 | 0.79 | 0.78 | 0.79 | 0.77 | |

| miR-23a | 0.869 | 1E−06 | 0.777–0.961 | 4.0255 | 0.626 | 0.87 | 0.76 | 0.81 | 0.79 | 0.85 | |

| miR-24 | 0.779 | 0.0002 | 0.662–0.896 | − 0.1611 | 0.464 | 0.53 | 0.93 | 0.73 | 0.89 | 0.66 | |

| miR-142-3p | 0.783 | 0.0001 | 0.667–0.898 | 2.034 | 0.493 | 0.7 | 0.79 | 0.75 | 0.78 | 0.72 | |

| miR-222 | 0.816 | 0.00003 | 0.711–0.921 | 3.3333 | 0.497 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.75 | 0.86 | 0.68 | |

| VP versus CTRL | let-7d | 0.765 | 0.001 | 0.63–0.9 | 3.8282 | 0.478 | 0.48 | 1 | 0.77 | 1 | 0.71 |

| miR-15b | 0.767 | 0.001 | 0.637–0.896 | 1.8584 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 1 | 0.76 | 1 | 0.7 | |

| miR-23a | 0.677 | 0.026 | 0.533–0.822 | 4.2789 | 0.37 | 0.68 | 0.69 | 0.69 | 0.65 | 0.71 | |

| miR-222 | 0.757 | 0.001 | 0.629–0.885 | 3.2229 | 0.406 | 0.44 | 0.97 | 0.72 | 0.92 | 0.67 | |

| PD versus VP | miR-23a | 0.779 | 0.0004 | 0.658–0.9 | 3.947 | 0.467 | 0.87 | 0.6 | 0.75 | 0.72 | 0.79 |

| miR-29a | 0.723 | 0.005 | 0.59–0.856 | 1.431 | 0.36 | 0.4 | 0.96 | 0.65 | 0.92 | 0.57 | |

| miR-181c | 0.815 | 0.00007 | 0.7–0.931 | 7.1732 | 0.564 | 0.72 | 0.84 | 0.78 | 0.84 | 0.72 | |

| ND versus CTRL | miR-22* | 0.778 | 0.00002 | 0.682–0.873 | 5.8567 | 0.46 | 0.66 | 0.79 | 0.71 | 0.87 | 0.53 |

| miR-23a | 0.79 | 0.00001 | 0.691–0.888 | 3.9122 | 0.51 | 0.71 | 0.79 | 0.74 | 0.87 | 0.57 |

For each comparison and each miRNA, the AUC (area under the curve), the 95% CIs (confidence intervals), and the p value of the ROC curve are shown. The table also reports the Youden index calculated for each curve, the associated cut-off with sensitivity and specificity, and positive and negative predictive values

We also evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of biomarker signatures by computing a single ROC curve for each comparison on the previously obtained logistic regression models (Table 11). Results obtained from univariate and multivariable ROC curve analyses were compared, showing that all the multivariable ROC curves have a higher AUC value compared with the univariate ROC curves of each biomarker in the same comparison.

Table 11.

Multivariate ROC curves by logistic regression models

| Comparison | AUC | Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive predictive value | Negative predictive value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD versus CTRL | 0.836 | 0.76 | 0.8 | 0.72 | 0.77 | 0.75 |

| VD versus CTRL | 0.888 | 0.79 | 0.76 | 0.81 | 0.76 | 0.81 |

| AD versus VD | 0.854 | 0.72 | 0.8 | 0.62 | 0.75 | 0.68 |

| PD versus CTRL | 0.944 | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.87 |

| VP versus CTRL | 0.859 | 0.77 | 0.69 | 0.84 | 0.8 | 0.75 |

| PD versus VP | 0.92 | 0.83 | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.81 |

| ND versus CTRL | 0.807 | 0.74 | 0.88 | 0.4 | 0.78 | 0.59 |

For each comparison, ROC curve parameters are shown

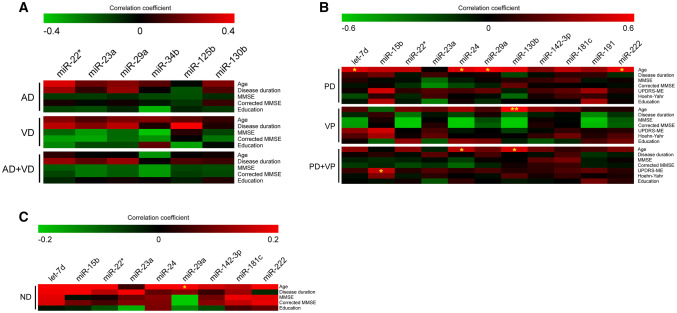

Correlation Between DE miRNAs and Clinicopathological Parameters

Correlation analysis was performed between miRNA expression (−ΔCts) and clinicopathological parameters of patients affected by neurodegenerative diseases. No significant correlation was observed in AD and VD patients (considered as different groups or a single macro-group) between miRNA expression and disease duration, mini-mental state examination (MMSE) score, MMSE score corrected for age and education, or education (Fig. 3a, Online Resource Table 1). Similarly, no significant correlation was observed in PD and VP patients (considered as different groups) between miRNA expression and disease duration, MMSE score, MMSE score corrected for age and education, Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale Motor Examination (UPDRS-ME), Hoehn-Yahr, or education. Considering PD and VP patients as a single macro-group, we observed a significant positive correlation between miR-15b and UPDRS-ME score (Fig. 3b, Online Resource Table 2). Moreover, no significant correlation was observed in ND patients for disease duration, MMSE score, MMSE score corrected for age and education, or education (Fig. 3c, Online Resource Table 3). Since subgroups of patients were administered with therapy, the potential effect of drugs in serum miRNA expression was evaluated. We stratified patients for the specific drug administered with and compared the different therapy subgroups with each other and with the untreated group; all the treated patients were also grouped together and compared with untreated ones. No statistical difference was observed in any of the comparisons. Given that neurodegenerative disorders are age-related, we investigated the correlation between miRNA expression and age in the entire cohort of AD, PD, VD, and VP patients and CTRL individuals. We observed a significant positive correlation between age and let-7d, miR-24, and miR-222 (Online Resource Table 3). The same correlation analysis was performed by stratifying patients in pathological groups (AD, VD, AD + VD, PD, VP, PD + VP, and CTRL): we observed no significant correlations with age for AD, VD, AD + VD, and CTRL groups, while significant positive correlations with age were identified for let-7d, miR-24, miR-29a, and miR-222 in PD group; miR-130b in VP group; and miR-24 and miR-130b in PD + VP group (Figs. 3a and 4b, Online Resource Table 4). Finally, we also tested the association between miRNA expression and patient sex in all the pathological subgroups analyzed and in the entire cohort. No statistical association was observed between serum circulating miRNAs and sex.

Fig. 3.

Correlation between DE miRNAs and clinical parameters. Heatmap showing correlation between: a AD and VD patients, considered separately and as a unique macro-group, b PD and VP patients, considered separately and as a unique macro-group, and c ND patients, including both AD and PD patients. A color-coded scale depicts the Pearson or Spearman coefficient, showing negative correlation in green and positive correlation in red. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.005

Discussion

To date, there is no diagnostic test able to specifically discriminate different neurodegenerative diseases. Accordingly, diagnosis is based on the observation of clinical symptoms and brain lesions, phenotypes that often do not discriminate between similar pathologies. Moreover, given that the affected organ is the brain, it is impossible to take a tissue biopsy to confirm the diagnosis, until a post-mortem analysis can be performed after patient death (Reitz 2015; Massano and Bhatia 2012; O’Brien and Thomas 2015; Korczyn 2015; Venneti et al. 2011). To date, molecular diagnosis of NDs has not been fully explored. Indeed, molecular diagnostic biomarkers are only available for AD: Aβ42, t-tau, and p-tau can be measured in CSF (Jack et al. 2018), which sampling may be invasive and painful for the patient (Doherty and Forbes 2014). Accordingly, there is a great interest in the field of diagnostic research in the identification of specific non-invasive biomarkers that can discriminate between different neurodegenerative diseases. Looking for biomarkers, it is important to choose molecules that are stable and easy to collect and quantify (Byrnes and Weigl 2018). One of the most frequently used sources of biomarkers is blood, in the form of serum or plasma, which gathers molecules originating from all the districts of human body, and can be easily collected with a minimally invasive blood sampling. Within circulating molecules, miRNAs have been intensively studied as biomarkers in several different pathologies; indeed, serum or plasma circulating miRNAs showed a great stability and can be easily detected and quantified with modern molecular biology techniques. Among them, real-time PCR with TaqMan probes represents a technique characterized by high sensitivity and specificity, low-cost, and being easy to perform (Cortez et al. 2011). Accordingly, a large number of studies reporting serum or plasma circulating miRNAs as biomarkers of neurodegenerative diseases are available in the literature (Mushtaq et al. 2016; Ragusa et al. 2016; Vallelunga et al. 2014; Sheinerman et al. 2017). Studies with a similar rationale but performed using different technologies often obtained distinct, even opposing, results (Wang et al. 2016). This inconsistency of results may depend on the different procedures performed for RNA isolation or miRNA expression analysis; moreover, the different ethnic origin of patients enrolled in the study may contribute to explain the variability of the results. To overcome these potential issues, we analyzed the expression of a set of neuro-miRNAs, selected from the literature as proposed biomarkers for AD, PD, VD, and VP, in a unique cohort of patients. First, we analyzed the expression of all 23 selected miRNAs in a cohort of 75 patients (15 AD, 15 PD, 15 VD, 15 VP, and 15 CTRL), showing the differential expression of 13 miRNAs in different comparisons. We successively evaluated the expression of the most significant DE miRNAs in an enlarged cohort, consisting of 30 AD, 30 PD, 24 VD, and 25 VP patients and 30 CTRL. These validation experiments confirmed the dysregulations of all the DE miRNAs in the analyzed comparisons (AD vs. CTRL: miR-22*, miR-23a, miR-29a, and miR-125b; VD vs. CTRL: miR-23a, miR-29a, and miR-130b; AD vs. VD: miR-22*,miR-23a, miR-29a, miR-34b, and miR-130b; PD vs. CTRL: let-7d, miR-22*, miR-23a, miR-24, miR-142-3p, and miR-222; VP vs. CTRL: let-7d, miR-15b, miR-23a, and miR-222; and PD vs. VP: miR-23a, miR-29a, and miR-181c). Interestingly, miR-23a showed an altered expression in all comparisons, suggesting its possible application as a biomarker for neurodegeneration; similarly, miR-22* and miR-29a were dysregulated in both Alzheimer- and Parkinson-like diseases. On the contrary, let-7d, miR-15b, miR-24, miR-142-3p, miR-181c, and miR-222 seem to be associated with Parkinson-like phenotypes, while miR-34b, miR-125b, and miR-130b showed an altered expression only in Alzheimer-like disorders, suggesting the involvement of these neuro-miRNAs in a specific class of disease.

In the perspective of a diagnostic application for these miRNAs, we computed ROC curves to evaluate their diagnostic accuracy. Specifically, we computed univariate ROC curves, which were all statistically significant. In most cases, ROC curves showed a fair diagnostic performance (AUC > 0.7): AD versus CTRL: miR-125b, miR-22*, miR-23a, and miR-29a; AD versus VD: miR-22*; PD versus CTRL: let-7d, miR-24, and miR-142-3p; VP versus CTRL: let-7d, miR-15b, and miR-222; and PD versus VP: miR-23a and miR-29a. However, some univariate ROC curves showed a good diagnostic performance (AUC > 0.8) for some miRNAs: AD versus VD: miR-23a, miR-29a, miR-34b, and miR-130b; PD versus CTRL: miR-22*, miR-23a, and miR-222; and PD versus VP: miR-181c. Many published data, including those reported here, show that a single miRNA has often been proposed as a diagnostic biomarker for many diseases, including pathologies with different etiology and molecular pathogenesis. Accordingly, the application of a single miRNA as a diagnostic biomarker could not reach high levels of sensitivity and specificity. Instead, using a signature composed of multiple biomarkers would increase sensitivity and specificity and, consequently, diagnostic accuracy (Diaz-Arrastia et al. 2014). Therefore, we computed multivariable ROC curves, investigating for each comparison the accuracy of a signature including all the DE miRNAs associated with the disease in a logistic regression model. For some of the analyzed comparisons, the regression models included age as an a priori confounder, in order to assess clinically relevant differences in miRNA expression between phenotypes regardless of any possible difference in age among patient subgroups. Following this approach, we observed that multivariable ROC curves showed an increased AUC compared to univariate ROC curves in all the comparisons. This observation suggests that considering the DE miRNAs in combination would discriminate neurodegenerative patients from unaffected controls with higher accuracy. Moreover, we also identified that a signature of miRNAs able to discriminate diseases with similar phenotypes, such as PD versus VP, with a good diagnostic performance: miR-23a and miR-181c, together with age, showed an excellent AUC value (AUC = 0.92).

As previously discussed, one of the characteristics that make circulating miRNAs suitable for application as diagnostic biomarkers is their stability. The reason for this resistance to degradation is that circulating miRNAs do not flow in the blood as “naked” molecules; instead, they can be associated with protein, such as Argonaute proteins, thus forming ribonucleoprotein complexes (ElSharawy et al. 2016; Arroyo et al. 2011), or included in membrane microvesicles, such as exosomes (Valadi et al. 2007; Gallo et al. 2012). In recent years, several studies have investigated the expression of compounds included within exosomes, proposing these exosomal molecules as diagnostic biomarkers (Cheng et al. 2014; Fries and Quevedo 2018; Chen et al. 2017). Accordingly, the deregulation of miRNAs here observed in serum in toto could be derived from an altered shuttling driven by both exosomes and ribonucleoprotein complexes. To investigate the origin of altered miRNA levels, we re-evaluated the expression of the most dysregulated miRNAs in a small cohort of patients, analyzing two distinct serum fractions, represented by the exosomes isolated from serum, and the leftover serum, deprived of exosomes. Not surprisingly, we observed that different miRNAs presented a different distribution between nanovesicles and exosome-deprived serum (Ragusa et al. 2017). Indeed, miR-23a and miR-125b confirmed their upregulation in the serum deprived of exosomes, showing a preferential localization outside exosomes (e.g., microvesicles, Ago complex, apoptotic bodies). Conversely, miR-34b upregulation was only observed in the exosomal compartment, suggesting that this miRNA could be preferentially located within exosomes. Interestingly, miR-29a upregulation was observed in both compartments, suggesting that this miRNA could not have a preferential mechanism of extracellular transport.

Although our findings support the role of miRNAs as valid, stable, and easily detectable biomarkers of neurodegeneration, some limits of our study need to be mentioned. In particular, even if the diagnosis of AD and VD was made according to currently accepted criteria, a possible misclassification cannot be entirely ruled out due to the lack of post-mortem confirmation. Furthermore, growing evidence has demonstrated that AD and VD share several risk factors, including hypertension, type 2 diabetes, obesity, tobacco use, and sedentary lifestyle, which can impact on dementia incidence (Norton et al. 2014). The close interaction between AD and VD could make it sometimes difficult to definitively establish whether dementia is due to neurodegeneration, vascular damage, or both (mixed dementia) (O’Brien and Thomas 2015). Similarly, several studies have supported the role of cardiovascular risk factors not only in VP but also in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease development (Vikdahl et al. 2015), whose reliable differential diagnosis is still post-mortem (Mostile et al. 2018).

As study limit, biomarkers of neurodegeneration have not been dosed in study patients’ samples to be correlated with miRNA serum levels, at least for the cases of AD and VD. However, it should be noted that high levels of diagnostic accuracy have been obtained only for CSF biomarkers in AD, as they were included in the A/T/N system of the NIA-AA framework for the diagnosis in vivo of AD (Jack et al. 2018), while for VD there is a lack of potential serum biomarkers with high diagnostic specificity to be used as references for correlation analysis with miRNA serum levels.

Conclusions

To date, the diagnosis of NDs is mainly based on the observation of clinical symptoms; since different diseases, such as AD and VD, or PD and VP, share common symptoms, discriminating clinically similar diseases may be difficult. This study showed that the application of specific signatures of serum circulating miRNAs may be useful to improve diagnosis. Further multicentric studies on larger cohorts will be necessary to validate these neuro-miRNAs for their use in diagnostic approaches.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Scientific Bureau of the University of Catania for language support.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- AUC

Area under the curve

- CI

Confidence interval

- CNS

Central nervous system

- CSF

Cerebrospinal fluid

- CTRL

Unaffected controls

- DE

Differentially expressed

- HY

Hoeh–Yahr

- miRNA

microRNA

- MMSE

Mini-mental state examination

- NINCDS/ADRDA

National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association

- ND

Neurodegenerative disease

- OR

Odds ratio

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- UPDRS-ME

Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale Motor Examination

- VD

Vascular dementia

- VP

Vascular parkinsonism

Authors Contributions

MR, AN, MP, and MZ designed and conceived the experiments. AN, GM, AL, and LR obtained and characterized biological samples from patients. CB, GB, and FG performed the experiments. CB, GM, and MR contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data. CB, MR, GM, and AN wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the University of Catania through Finanziamento della Ricerca 2014 and 2016/2018 Department Research Plan of University of Catania (second line of intervention).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the ethical committee of the Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria Policlinico-Vittorio Emanuele, Catania, and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Arroyo JD, Chevillet JR, Kroh EM, Ruf IK, Pritchard CC, Gibson DF, Mitchell PS, Bennett CF, Pogosova-Agadjanyan EL, Stirewalt DL, Tait JF, Tewari M (2011) Argonaute2 complexes carry a population of circulating microRNAs independent of vesicles in human plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108(12):5003–5008. 10.1073/pnas.1019055108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer TA (2015) Proteinopathies, a core concept for understanding and ultimately treating degenerative disorders? Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 25(5):713–724. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blennow K, Vanmechelen E, Hampel H (2001) CSF total tau, Abeta42 and phosphorylated tau protein as biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurobiol 24(1–3):87–97. 10.1385/MN:24:1-3:087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botta-Orfila T, Morato X, Compta Y, Lozano JJ, Falgas N, Valldeoriola F, Pont-Sunyer C, Vilas D, Mengual L, Fernandez M, Molinuevo JL, Antonell A, Marti MJ, Fernandez-Santiago R, Ezquerra M (2014) Identification of blood serum micro-RNAs associated with idiopathic and LRRK2 Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci Res 92(8):1071–1077. 10.1002/jnr.23377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns A, Iliffe S (2009) Alzheimer’s disease. BMJ 338:b158. 10.1136/bmj.b158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrnes SA, Weigl BH (2018) Selecting analytical biomarkers for diagnostic applications: a first principles approach. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 18(1):19–26. 10.1080/14737159.2018.1412258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JJ, Zhao B, Zhao J, Li S (2017) Potential roles of exosomal microRNAs as diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic application in Alzheimer’s disease. Neural Plast 2017:7027380. 10.1155/2017/7027380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L, Sharples RA, Scicluna BJ, Hill AF (2014) Exosomes provide a protective and enriched source of miRNA for biomarker profiling compared to intracellular and cell-free blood. J Extracell Vesicles. 10.3402/jev.v3.23743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contrafatto D, Mostile G, Nicoletti A, Dibilio V, Raciti L, Lanzafame S, Luca A, Distefano A, Zappia M (2012) [(123) I]FP-CIT-SPECT asymmetry index to differentiate Parkinson’s disease from vascular Parkinsonism. Acta Neurol Scand 126(1):12–16. 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2011.01583.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortez MA, Bueso-Ramos C, Ferdin J, Lopez-Berestein G, Sood AK, Calin GA (2011) MicroRNAs in body fluids–the mix of hormones and biomarkers. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 8(8):467–477. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Guire V, Robitaille R, Tetreault N, Guerin R, Menard C, Bambace N, Sapieha P (2013) Circulating miRNAs as sensitive and specific biomarkers for the diagnosis and monitoring of human diseases: promises and challenges. Clin Biochem 46(10–11):846–860. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2013.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Arrastia R, Wang KK, Papa L, Sorani MD, Yue JK, Puccio AM, McMahon PJ, Inoue T, Yuh EL, Lingsma HF, Maas AI, Valadka AB, Okonkwo DO, Manley GT, Investigators T-T (2014) Acute biomarkers of traumatic brain injury: relationship between plasma levels of ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase-L1 and glial fibrillary acidic protein. J Neurotrauma 31(1):19–25. 10.1089/neu.2013.3040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty CM, Forbes RB (2014) Diagnostic lumbar puncture. Ulster Med J 83(2):93–102 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ElSharawy A, Roder C, Becker T, Habermann JK, Schreiber S, Rosenstiel P, Kalthoff H (2016) Concentration of circulating miRNA-containing particles in serum enhances miRNA detection and reflects CRC tissue-related deregulations. Oncotarget 7(46):75353–75365. 10.18632/oncotarget.12205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fries GR, Quevedo J (2018) Exosomal microRNAs as potential biomarkers in neuropsychiatric disorders. Methods Mol Biol 1733:79–85. 10.1007/978-1-4939-7601-0_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galimberti D, Villa C, Fenoglio C, Serpente M, Ghezzi L, Cioffi SM, Arighi A, Fumagalli G, Scarpini E (2014) Circulating miRNAs as potential biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 42(4):1261–1267. 10.3233/JAD-140756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo A, Tandon M, Alevizos I, Illei GG (2012) The majority of microRNAs detectable in serum and saliva is concentrated in exosomes. PLoS ONE 7(3):e30679. 10.1371/journal.pone.0030679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geekiyanage H, Jicha GA, Nelson PT, Chan C (2012) Blood serum miRNA: non-invasive biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Exp Neurol 235(2):491–496. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.11.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iadecola C (2013) The pathobiology of vascular dementia. Neuron 80(4):844–866. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR Jr, Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Dunn B, Haeberlein SB, Holtzman DM, Jagust W, Jessen F, Karlawish J, Liu E, Molinuevo JL, Montine T, Phelps C, Rankin KP, Rowe CC, Scheltens P, Siemers E, Snyder HM, Sperling R, Contributors (2018) NIA-AA research framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 14(4):535–562. 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankovic J (2008) Parkinson’s disease: clinical features and diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr 79(4):368–376. 10.1136/jnnp.2007.131045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jellinger KA (2008) Vascular Parkinsonism. Therapy 5(2):237–255. 10.2217/14750708.5.2.237 [Google Scholar]

- Jorm AF, Jolley D (1998) The incidence of dementia: a meta-analysis. Neurology 51(3):728–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoo SK, Petillo D, Kang UJ, Resau JH, Berryhill B, Linder J, Forsgren L, Neuman LA, Tan AC (2012) Plasma-based circulating MicroRNA biomarkers for Parkinson’s disease. J Parkinsons Dis 2(4):321–331. 10.3233/JPD-012144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korczyn AD (2015) Vascular Parkinsonism–characteristics, pathogenesis and treatment. Nat Rev Neurol 11(6):319–326. 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P, Dezso Z, MacKenzie C, Oestreicher J, Agoulnik S, Byrne M, Bernier F, Yanagimachi M, Aoshima K, Oda Y (2013) Circulating miRNA biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS ONE 8(7):e69807. 10.1371/journal.pone.0069807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez OL, Dekosky ST (2008) Clinical symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. Handb Clin Neurol 89:207–216. 10.1016/S0072-9752(07)01219-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandourah AY, Ranganath L, Barraclough R, Vinjamuri S, Hof RV, Hamill S, Czanner G, Dera AA, Wang D, Barraclough DL (2018) Circulating microRNAs as potential diagnostic biomarkers for osteoporosis. Sci Rep 8(1):8421. 10.1038/s41598-018-26525-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margis R, Margis R, Rieder CR (2011) Identification of blood microRNAs associated to Parkinsonis disease. J Biotechnol 152(3):96–101. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2011.01.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsili L, Rizzo G, Colosimo C (2018) Diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease: from James Parkinson to the concept of prodromal disease. Front Neurol 9:156. 10.3389/fneur.2018.00156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massano J, Bhatia KP (2012) Clinical approach to Parkinson’s disease: features, diagnosis, and principles of management. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2(6):a008870. 10.1101/cshperspect.a008870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell PS, Parkin RK, Kroh EM, Fritz BR, Wyman SK, Pogosova-Agadjanyan EL, Peterson A, Noteboom J, O’Briant KC, Allen A, Lin DW, Urban N, Drescher CW, Knudsen BS, Stirewalt DL, Gentleman R, Vessella RL, Nelson PS, Martin DB, Tewari M (2008) Circulating microRNAs as stable blood-based markers for cancer detection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105(30):10513–10518. 10.1073/pnas.0804549105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostile G, Nicoletti A, Cicero CE, Cavallaro T, Bruno E, Dibilio V, Luca A, Sciacca G, Raciti L, Contrafatto D, Chiaramonte I, Zappia M (2016) Magnetic resonance Parkinsonism index in progressive supranuclear palsy and vascular Parkinsonism. Neurol Sci 37(4):591–595. 10.1007/s10072-016-2489-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostile G, Nicoletti A, Zappia M (2018) Vascular Parkinsonism: still looking for a diagnosis. Front Neurol 9:411. 10.3389/fneur.2018.00411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mushtaq G, Greig NH, Anwar F, Zamzami MA, Choudhry H, Shaik MM, Tamargo IA, Kamal MA (2016) miRNAs as circulating biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. Med Chem 12(3):217–225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton S, Matthews FE, Barnes DE, Yaffe K, Brayne C (2014) Potential for primary prevention of Alzheimer’s disease: an analysis of population-based data. Lancet Neurol 13(8):788–794. 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70136-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien JT, Thomas A (2015) Vascular dementia. Lancet 386(10004):1698–1706. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00463-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olanow CW, Brundin P (2013) Parkinson’s disease and alpha synuclein: is Parkinson’s disease a prion-like disorder? Mov Disord 28(1):31–40. 10.1002/mds.25373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu C, Kivipelto M, von Strauss E (2009) Epidemiology of Alzheimer’s disease: occurrence, determinants, and strategies toward intervention. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 11(2):111–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragusa M, Bosco P, Tamburello L, Barbagallo C, Condorelli AG, Tornitore M, Spada RS, Barbagallo D, Scalia M, Elia M, Di Pietro C, Purrello M (2016) miRNAs plasma profiles in vascular dementia: biomolecular data and biomedical implications. Front Cell Neurosci 10:51. 10.3389/fncel.2016.00051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragusa M, Barbagallo C, Cirnigliaro M, Battaglia R, Brex D, Caponnetto A, Barbagallo D, Di Pietro C, Purrello M (2017) Asymmetric RNA distribution among cells and their secreted exosomes: biomedical meaning and considerations on diagnostic applications. Front Mol Biosci 4:66. 10.3389/fmolb.2017.00066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitz C (2015) Genetic diagnosis and prognosis of Alzheimer’s disease: challenges and opportunities. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 15(3):339–348. 10.1586/14737159.2015.1002469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo R, Ragusa M, Barbagallo C, Sammito M, Gulisano M, Cali PV, Pappalardo C, Barchitta M, Granata M, Condorelli AG, Barbagallo D, Scalia M, Agodi A, Di Pietro C, Purrello M (2015) Circulating miRNAs profiles in tourette syndrome: molecular data and clinical implications. Mol Brain 8:44. 10.1186/s13041-015-0133-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman GC, Tatemichi TK, Erkinjuntti T, Cummings JL, Masdeu JC, Garcia JH, Amaducci L, Orgogozo JM, Brun A, Hofman A et al (1993) Vascular dementia: diagnostic criteria for research studies. Report of the NINDS-AIREN International Workshop. Neurology 43(2):250–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachdev P, Kalaria R, O’Brien J, Skoog I, Alladi S, Black SE, Blacker D, Blazer DG, Chen C, Chui H, Ganguli M, Jellinger K, Jeste DV, Pasquier F, Paulsen J, Prins N, Rockwood K, Roman G, Scheltens P, Internationlal Society for Vascular B, Cognitive D (2014) Diagnostic criteria for vascular cognitive disorders: a VASCOG statement. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 28(3):206–218. 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Series H, Esiri M (2012) Vascular dementia: a pragmatic review. Adv Psychiatr Treat 18(5):372–380. 10.1192/apt.bp.110.008888 [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-Pozo A, Frosch MP, Masliah E, Hyman BT (2011) Neuropathological alterations in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 1(1):a006189. 10.1101/cshperspect.a006189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheinerman KS, Toledo JB, Tsivinsky VG, Irwin D, Grossman M, Weintraub D, Hurtig HI, Chen-Plotkin A, Wolk DA, McCluskey LF, Elman LB, Trojanowski JQ, Umansky SR (2017) Circulating brain-enriched microRNAs as novel biomarkers for detection and differentiation of neurodegenerative diseases. Alzheimers Res Ther 9(1):89. 10.1186/s13195-017-0316-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skovronsky DM, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ (2006) Neurodegenerative diseases: new concepts of pathogenesis and their therapeutic implications. Annu Rev Pathol 1:151–170. 10.1146/annurev.pathol.1.110304.100113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EE (2017) Clinical presentations and epidemiology of vascular dementia. Clin Sci (Lond) 131(11):1059–1068. 10.1042/CS20160607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan L, Yu JT, Liu QY, Tan MS, Zhang W, Hu N, Wang YL, Sun L, Jiang T, Tan L (2014) Circulating miR-125b as a biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Sci 336(1–2):52–56. 10.1016/j.jns.2013.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thery C (2011) Exosomes: secreted vesicles and intercellular communications. Biol Rep 3:15. 10.3410/b3-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tijsen AJ, Pinto YM, Creemers EE (2012) Circulating microRNAs as diagnostic biomarkers for cardiovascular diseases. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 303(9):H1085–H1095. 10.1152/ajpheart.00191.2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turchinovich A, Weiz L, Langheinz A, Burwinkel B (2011) Characterization of extracellular circulating microRNA. Nucleic Acids Res 39(16):7223–7233. 10.1093/nar/gkr254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valadi H, Ekstrom K, Bossios A, Sjostrand M, Lee JJ, Lotvall JO (2007) Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat Cell Biol 9(6):654–659. 10.1038/ncb1596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallelunga A, Ragusa M, Di Mauro S, Iannitti T, Pilleri M, Biundo R, Weis L, Di Pietro C, De Iuliis A, Nicoletti A, Zappia M, Purrello M, Antonini A (2014) Identification of circulating microRNAs for the differential diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease and Multiple System Atrophy. Front Cell Neurosci 8:156. 10.3389/fncel.2014.00156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venneti S, Robinson JL, Roy S, White MT, Baccon J, Xie SX, Trojanowski JQ (2011) Simulated brain biopsy for diagnosing neurodegeneration using autopsy-confirmed cases. Acta Neuropathol 122(6):737–745. 10.1007/s00401-011-0880-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vikdahl M, Backman L, Johansson I, Forsgren L, Haglin L (2015) Cardiovascular risk factors and the risk of Parkinson’s disease. Eur J Clin Nutr 69(6):729–733. 10.1038/ejcn.2014.259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Chen J, Sen S (2016) MicroRNA as biomarkers and diagnostics. J Cell Physiol 231(1):25–30. 10.1002/jcp.25056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Li S, Li L, Li M, Guo C, Yao J, Mi S (2015) Exosome and exosomal microRNA: trafficking, sorting, and function. Genomics Proteomics Bioinform 13(1):17–24. 10.1016/j.gpb.2015.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.