Abstract

Leptomeningeal metastases (LM) are increasingly becoming recognized as a treatable, yet generally incurable, complication of advanced cancer. As modern cancer therapeutics have prolonged the lives of patients with metastatic cancer, specifically in patients with parenchymal brain metastases, treatment options, and clinical research protocols for patients with LM from solid tumors have similarly evolved to improve survival within specific populations. Recent expansions in clinical investigation, early diagnosis, and drug development have given rise to new unanswered questions. These include leptomeningeal metastasis biology and preferred animal modeling, epidemiology in the modern cancer population, ensuring validation and accessibility of newer leptomeningeal metastasis diagnostics, best clinical practices with multimodality treatment options, clinical trial design and standardization of response assessments, and avenues worthy of further research. An international group of multi-disciplinary experts in the research and management of LM, supported by the Society for Neuro-Oncology and American Society of Clinical Oncology, were assembled to reach a consensus opinion on these pressing topics and provide a roadmap for future directions. Our hope is that these recommendations will accelerate collaboration and progress in the field of LM and serve as a platform for further discussion and patient advocacy.

Keywords: consensus guideline, intrathecal therapy, leptomeningeal metastases, leptomeningeal disease, radiation therapy, systemic therapy

For the podcast associated with this article, please visit ‘https://soc-neuro-onc.libsyn.com/leptomeningeal-disease-a-sno-and-asco-review’

Leptomeningeal metastases (LM), long regarded as an advanced complication of solid malignancies, have strategically evaded durable treatment options for decades.1,2 The ambiguous processes which facilitate cancer cell dissemination to the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and survival in such hypoxic, nutrient-sparse conditions have led to challenges in curbing the growth of metastases within the leptomeninges relative to other intracranial and extracranial sites. Faced with widespread therapeutic nihilism and limited expert consensus on optimal diagnostic and management strategies, this disease state has historically led to significant neurologic morbidity and rapid mortality for those afflicted. However, as modern oncologic care has prolonged the lives of patients with cancer and improved early diagnosis of central nervous system (CNS) progression, this previously described “rare” stage of malignancy is now being observed in as many as 1 in 5 patients with certain high-risk cancer molecular subtypes.3–11 Paralleling this rise in LM diagnosis is a greater scientific understanding of cancer cell biology in the leptomeningeal space and the development of innovative treatment options that challenge the historical survival benchmark of 2–4 months in patients with leptomeningeal tumor dissemination.

To effectively meet the demands of rapidly expanding therapeutic options and diagnostic algorithms in this space, the Society for Neuro-Oncology (SNO) and American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) have facilitated a platform for international expert discussion and consensus on the topics of LM biology, epidemiology, diagnosis, management, clinical research, and future directions (Table 1). The aim of this consensus statement is to consolidate the modern state of LM innovation into cohesive recommendations for best clinical and research practices, with attention to critical unresolved questions and topics worthy of focused collaborative investigation.

Table 1.

Key Points From the International Leptomeningeal Metastasis Collaborative

| Category | Key points |

|---|---|

| Biology |

• Translational research of the mechanisms of LM metastatic spread, survival within the nutrient-spare CSF, local immune interactions, and therapeutic resistance lag behind that of metastases to the brain and extracranial sites, and should be prioritized. • Preclinical models of LM from solid tumor primaries can be created through iterative in vivo selection of cell lines to create a subpopulation of leptomeningeal-homing cells, which when injected into allograft and xenograft models recapitulate human disease. • Standardization of CSF collection and processing guidelines across institutions to preserve cellular and soluble components would aid in research discovery and streamline CSF banking procedures. • Warm autopsy programs should be encouraged as a means of studying pial-adherent leptomeningeal cells, which are not represented in routine CSF collections. |

| Epidemiology |

• The incidence of LM is challenging to quantify due to its relative rarity, limitations associated with disease diagnosis, and exclusion of LM from most modern population-based epidemiologic studies. • The prognosis of LM is poor but heterogeneous, with certain subgroups of patients (eg, EGFR-mutant NSCLC, HER2-positive breast cancer) demonstrating superior survival. The historical survival benchmark of 2–4 months does not apply to all patients, and patient counseling and clinical trial design should be individualized based on cancer- and patient-specific factors. • Creation of a multinational registry of patients with LM, with inclusion of a de-identified biorepository, would provide a means of analyzing LM biology and prognosis on a grander scale and could serve as a sample population for synthetic controls in clinical trial design. |

| Radiology |

• As a disease state encompassing the entire neuroaxis, patients with LM should undergo high quality MRI brain and total spine with and without contrast at the time of diagnosis and for routine disease monitoring. • Standardization of imaging practices in patients with LM is lacking. Technical imaging recommendations to enhance LM monitoring include the use of 1.5 and 3 Tesla MRI scanners only, consistency of MRI scanner at diagnosis and surveillance time points, inclusion of 3D T1 post-contrast images with isotropic 1 mm voxels, and a reformatted slice thickness of 3 mm to enhance detection of small deposits. • CSF sampling should be performed in all patients with suspicious leptomeningeal enhancement to confirm the diagnosis of LM and rule out radiographic mimics. |

| Liquid biopsy |

• CSF cytology remains the gold standard for LM diagnosis and should be collected in all patients, both at diagnosis and to monitor disease progression at the discretion of the treating clinician. • Due to the low sensitivity of CSF cytology, a negative result in a patient with a strong suspicion of LM should prompt a second CSF puncture with optimal collection and processing procedures (ie, minimum cytology volume of 5–10 mL, laboratory processing within 30 minutes, sampling adjacent to regions of abnormal enhancement when feasible). • CSF biomarkers with improved sensitivity and potential to guide therapeutic decisions, including rare cell capture techniques and circulating tumor DNA, are available at a limited number of tertiary cancer centers. These techniques require validation and CLIA certification before they can be routinely incorporated into clinical practice and made more widely available. |

| Radiation therapy |

• LM is a disseminated neuraxial process. Consequently, conventional IFRT (WBRT or focal cranial or spinal RT) are palliative interventions, and have not been proven to improve survival in LM. • Proton CSI has demonstrated reasonable toxicity and superior survival compared to IFRT in adults with LM in phase I/II studies, and so may be a therapeutic option with careful consideration of a patient’s performance status, extracranial disease, and goals of care. Timely access to proton centers is limited and hinders the widespread applicability of this treatment option at present. |

| Systemic therapy |

• Systemic therapies with CNS bioactivity and blood-CSF barrier permeability should be prioritized in all patients with LM, both to treat active disease and prevent leptomeningeal reseeding following local therapies. • Investigations of systemic therapies in LM should include CSF pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic analyses to better understand blood-CSF penetration and local bioactivity, particularly for modern agents with demonstrated CNS efficacy (eg, small molecule inhibitors, immunotherapies, antibody-drug conjugates). |

| Intrathecal therapy |

• Intrathecal chemotherapies are most effective in patients with thin linear LM deposits and unobstructed CSF flow. • Untargeted intrathecal therapies (eg, methotrexate, cytarabine, thiotepa, topotecan) conferred a median survival of 2–4 months in historical clinical trials. More recently investigated intrathecal therapies (eg, trastuzumab, nivolumab, pemetrexed) have reasonable safety profiles and a median survival of 4–9 months in more modern phase I/II trials. • Intrathecal drug development would benefit from consistency and standardization of preclinical testing, drug preparation, and conversion to human dosing as new therapeutics are investigated. |

| Surgical interventions |

• Ventricular access devices (eg, Ommaya reservoir) are preferred over lumbar drug delivery in patients receiving intrathecal chemotherapy, due to ease of administration, enhanced drug circulation, and association with superior survival. Early device placement may also be considered in those requiring frequent CSF sampling or in clinical research settings for improvement in pharmacokinetic monitoring. • Modern investigations of ventricular access devices suggest lower complication rates (2%–10%) than previously reported (10%–15%). • CSF diversion devices (eg, ventriculoperitoneal shunts) relieve symptoms of elevated intracranial pressure in the majority of treated patients, and should be offered as a palliative procedure based on a patient’s goals of care and availability of further tumor-directed therapy. • Clinical trials of intrathecal therapies should refrain from enrollment of patients with CSF diversion devices as these risk interference with pharmacokinetic endpoints. |

| Clinical trial design |

• Clinical trials in LM are both feasible and necessary. • Standardization of consistency in LM diagnostic criteria for enrollment, endpoint selection, and response assessments should be a priority. • Overall survival remains the most objective outcome measurement in LM clinical trials due to the lack of validation of LM response assessments. A revised RANO MRI scorecard has been validated with the moderate interobserver agreement; however, validation of other RANO proposed response criteria (ie, cytologic response, neurologic examination) remains pending. • When using progression-free survival as a clinical endpoint in trials of systemic therapies with CNS bioactivity, data should be collected regarding the site of progression (extracranial versus intracranial) and whether intracranial progression was due to parenchymal or leptomeningeal metastases. • Phase I trials in LM should consider broad eligibility in cancer subtypes when the primary objective is safety. Phase II/III trials in LM would benefit from stricter criteria, including restriction to a single cancer subtype and complete neuraxial surveillance at enrollment and follow-up, to best evaluate efficacy. • Clinical protocols evaluating drug efficacy in the CNS should be designed with dedicated brain and leptomeningeal metastasis cohorts and include CSF pharmacokinetic analyses. • Multicenter participation in clinical trial execution is encouraged to foster collaboration, improve patient access, and prevent early study closure due to slow enrollment. |

| Novel therapeutics |

• Advocacy efforts should continue to encourage LM patient inclusion in industry-sponsored clinical trials of emerging systemic therapies with potential CNS activity. • Active areas of translational research in LM to be considered include: approaches targeting LM metabolism, therapeutics which enhance LM interactions with the local immune microenvironment, intraventricularly delivered radioactive particles, and reformulated or conjugated drugs which enhance blood-CSF barrier penetration. |

Abbreviations: LM, leptomeningeal metastases; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; IFRT, involved field radiation therapy; WBRT, whole-brain radiation therapy; RT, radiation therapy; CSI, craniospinal irradiation; CNS, central nervous system; RANO, Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology.

Biology

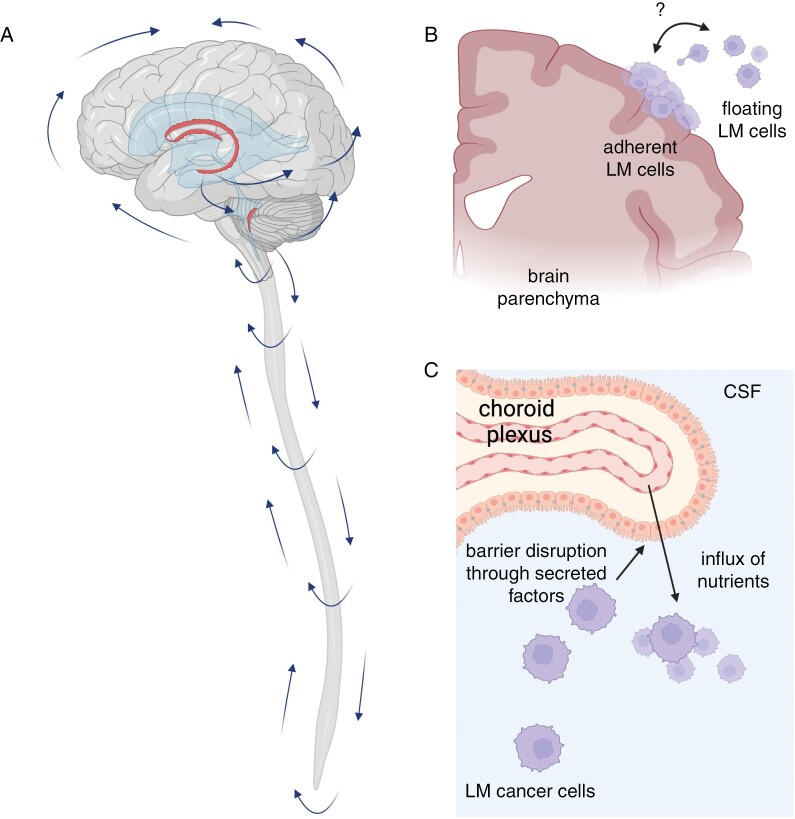

LM occurs when tumor cells disseminate into and grow within the leptomeninges (Figure 1). The leptomeninges, consisting of the pia and inner arachnoid, surround the CNS and contain circulating CSF. Cancer cells may access the leptomeningeal space through various means, including hematogenous dissemination via the choroid plexus, direct seeding from brain and dural metastases, perineural invasion, and retrograde venous extension via Batson’s plexus.12–14 Upon entry, leptomeningeal cancer cells freely circulate throughout the neuraxis driven by pulsatile CSF flow, where they exist either as adherent plaques to the surface of the brain, spinal cord, and exiting cranial and spinal nerves and/or as free-floating cells or cellular clusters.15 LM receives sparse nutrients leaking though the impaired blood-CSF barrier of the choroid plexus and potentially other sources as well.14 The blood-CSF barrier through which cancer cells and certain drugs penetrate the subarachnoid space is both anatomically and functionally distinct from the blood-brain barrier, which has therapeutic consequences when considering differential drug permeability in CNS compartments. LM are also notably distinct from metastases to the pachymeninges, consisting of the dura and outer arachnoid mater (Supplementary Figure 1). As this space is outside of the blood-brain barriers, metastases to the pachymeninges are therefore extra-axial. These pachymeningeal or dural-based metastases most commonly arise from breast and prostate cancers, or as a result of post-operative pachymeningeal seeding following resection of a brain or dural metastasis.16,17 Given the large differences in the biology, prognosis, blood supply, and management between these sites of disease, pachymeningeal metastases will not be reviewed here.

Figure 1.

Biology of leptomeningeal metastases (LM). (A)In a healthy individual, CSF is produced by choroid plexi (red structures) located within the ventricles. CSF circulates from the ventricles through the subarachnoid spaces of the brain and spinal cord, and is reabsorbed into blood circulation via arachnoid granulations in a pressure-dependent manner. (B) LM grows as adherent cells on the surface of the brain and spinal cord, appearing on magnetic resonance imaging as contrast-enhancing plaques, and/or freely floating cells in the CSF, which may be detected by CSF cytopathologic examination. These 2 states are highly plastic and maintained by unknown factors. (C) LM produces a range of factors that perturbs the function of the blood-CSF barrier at the choroid plexus, allowing entry of nutrients and mitogens from plasma into the CSF. Created with BioRender.com.

LM harbors a unique biology conferring the ability to thrive in a microenvironment largely devoid of oxygen, micronutrients, and traditional hematogenous blood supply.18 Focused investigation of mechanisms of metastatic spread to and within the leptomeninges,12,15,19,20 unique drivers of leptomeningeal cancer cell survival and therapeutic resistance,14,21,22 and the intrathecal immune responses to neoplastic dissemination,22–25 have generally lagged behind that of metastases to the brain parenchyma and other extracranial sites. LM from primary CNS tumors may additionally have different and/or overlapping mechanisms when compared to systemic cancers that spread to the leptomeninges.

Historically, a major underlying cause for limited mechanistic work has been a lack of genetically tractable preclinical models of LM. This has been recently overcome, in part, through the use of cancer cell lines created through iterative in vivo selection. Such cells are capable of both surviving within the hypoxic microenvironment and preferentially disseminating to the leptomeninges over other organ systems following intracardiac injection. They recapitulate human disease and allow for reproducible examination of the LM phenotype in preclinical models.14 Intracisternal injection of leptomeningeal-derived cell lines into animal models offers enhanced control and manipulation of compartment-specific metastatic processes.14,15 However, this method does not capture the natural course of metastatic dissemination to the CNS. Furthermore, the selection of allograft versus xenograft mouse modeling has specific advantages and disadvantages.26 Allograft animal models with shared animal-derived cell lines offer reliable biocompatibility of transplanted tissues in immunocompetent hosts, but may require extensive exploration of human samples in order to recognize inter-species differences in cancer biology. Alternatively, patient-derived xenografts, in which human cancer cell lines are transplanted into immunosuppressed or humanized animal models, retain some degree of genomic integrity of human cancer at the expense of intact host immune regulation.27 Embracing these unique challenges in experimental design and replication of each LM study across a range of animal models will help to improve the reliability of preclinical conclusions and pathway selection for further clinical exploration.

Clinical CSF collections offer an opportunity for interrogation of LM at the human scale and validation of observations made in mouse models. These CSF specimens provide access to the cellular milieu of immune and neoplastic cells as well as soluble ligands, nucleic acids, and metabolites. However, great heterogeneity exists between institutional CSF banking policies, and standardization of CSF sample collection, separation, preservation, and shipping procedures are lacking. These steps are critical in preventing sample degradation and preservation of pre-analytical variables, with initial sample handling and processing narrowing the scope of later investigational options. Funding to execute these procedures properly is often also limited, leaving these rich sources of information underexplored. To combat this issue in primary brain tumors, the Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology (RANO) group recently published guidelines for research CSF sampling in patients with glioma.28 The LM research community would benefit from a similar internationally accepted biospecimen handling guideline, a proposal of which we have provided as an appendix (Appendix 1). In the interest of further exploring LM pathophysiology and potential therapeutic targets on a grander scale, our consensus group supports the systematic collection of serial CSF and ideally paired blood samples in patients for whom CSF sampling is otherwise clinically indicated. As feasible, patients should be offered to consent to biomaterial sampling programs when LM are suspected.

While current experimental leptomeningeal studies heavily rely upon malignant cells within CSF biospecimens, this methodology fails to capture potential intrinsic differences between the floating and adherent leptomeningeal cell populations. Leptomeningeal biopsies and autopsy studies are the only means of studying this second population of cells in human specimens, both of which are exceedingly rare with current clinical practices. Warm autopsy programs29,30 represent a valuable and underutilized opportunity to provide high-quality diverse metastatic specimens for further investigation of leptomeningeal progression through advanced genomic, proteomic, and metabolomic approaches. Standardization of autopsy tissue-procurement protocols, as well as timely, thoughtful discussions with patients and their caregivers about end-of-life preferences, would facilitate the growth of rapid autopsy programs for clinical research and drug development.

Epidemiology

The incidence of LM is challenging to quantify. Large-scale population and autopsy-based analyses provide an estimation of brain metastase incidence per cancer subtype.31–34 However, reliable data on the most basic epidemiologic features of LM (eg, incidence, survival, and cause of death) are lacking because such encompassing surveys have not been conducted specifically for LM, and those that exist utilize relatively insensitive diagnostic criteria which have often been inconsistently applied. Smaller institutional reviews and autopsy studies have quoted the incidence of LM in advanced malignancies to approximate 9%–25% for small cell and non-small cell lung cancer, 5%–20% for breast cancer, and 6%–18% for melanoma.2–11,35–37

Even more elusive is the prognosis of LM stratified by factors such as age, tumor histology, molecular features, and clinical characteristics. Among patients with brain metastases and despite improving treatments for CNS dissemination, the presence of LM remains an independent predictor of inferior survival.38–40 Studies addressing the vital questions of treatment and prophylaxis of LM depend on high-quality data not only about incidence and outcome, but also how these endpoints are modified by common and prognostically important variables. A “historical median survival” of 2–4 months has been applied to all patients with newly diagnosed LM, and has served, often inappropriately, as a survival benchmark for many clinical trials in this patient population. However, despite the generally incurable nature of LM, modern therapeutics have introduced more heterogeneity in leptomeningeal progression-free and overall survival, with certain patient populations far exceeding this historical survival estimate.41–43 Consequently, prognostic discussions with patients and the design of clinical trials should not rely on an outdated “one size fits all” survival estimate, and large, contemporary population-based data are needed to provide more granularity to this topic.

Given the relative rarity of LM outside of tertiary cancer centers, multicenter collaboration is needed to address these questions at scale. Creation of a multinational registry of patients with LM, including a wide range of patient- and cancer-specific variables, would generate adequate numbers of representative subjects to better understand survival trends and analyze outcomes by prognostic factors.44 Such a registry, with uniformly collected data, could also serve as a modern “synthetic” control group for median survival benchmarks based on cancer subtypes in clinical trial design.45 The use of registry-based synthetic controls would require ample patient numbers stratified by key demographic data (eg, molecular markers, functional status, newly diagnosed versus recurrent LM, concurrent brain metastases) to maximize reliability, with the caveat that findings of therapeutic significance should be further evaluated in randomized controlled studies. Inclusion of carefully curated biorepositories for blood, CSF, and concurrent parenchymal brain metastasis, when available, would additionally provide valuable specimens for research into the differential biology of brain and LM and potential therapeutic targets of LM, and should be a priority of institutional, governmental, and foundational funding sources. Several logistical challenges, including appropriate informed consent procedures, financial and organizational support, and rigorous registry design and data monitoring procedures will be required, but successful models in other disease states already exist.46–49

Diagnostic Methods

Radiology

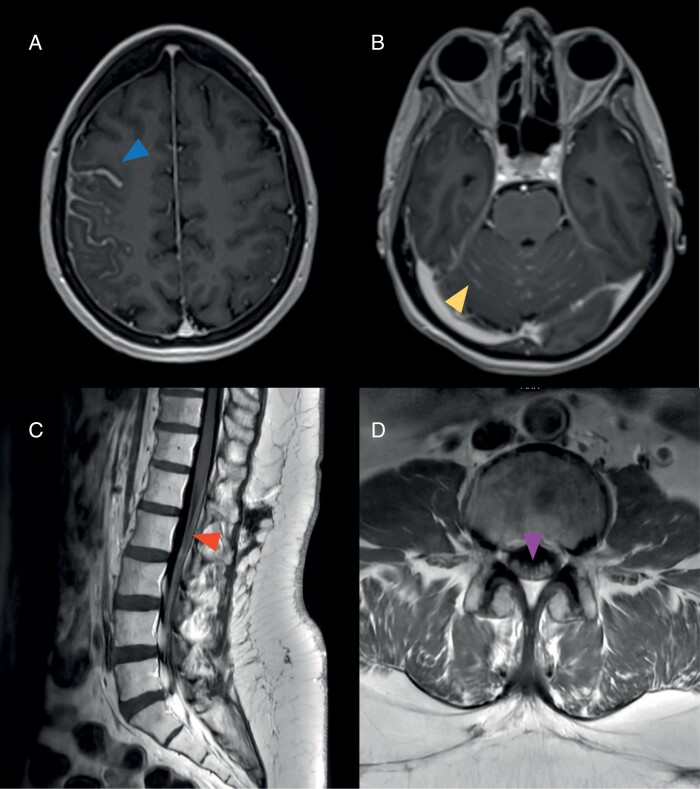

LM are often, but not universally, detected on neuraxial contrast-enhanced imaging, appearing as linear or nodular deposits coating cranial and spinal nerves, cerebral sulci, cerebellar folia, and spinal cord (Figure 2).2 Leptomeningeal deposits may either be diffuse or focal. Brain and total spine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the preferred modality over computed topography scans due to superior resolution.50 Consistent radiographic measurement of LM is fraught with challenges, however, due to (1) ill-defined and often small (< 5 mm) deposits, (2) inter-scan variability due to thick 2D image slices, gaps, and patient positioning, (3) appearance of at times non-enhancing disease visible only on T2-weighted images, and (4) technical differences between MRIs performed across facilities.

Figure 2.

Classic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) features in patients with leptomeningeal metastases. (A) Thick sulcal enhancement involving the right frontoparietal sulci (arrowhead) on MRI brain axial T1-MPRAGE post-contrast images. (B) Linear ill-defined enhancement and nodules studding the cerebellar folia (arrowhead) on MRI brain axial T1-MPRAGE post-contrast images. Smooth leptomeningeal enhancement may also be seen coating the cranial nerves in the posterior fossa. (C) Smooth widespread enhancement of the conus medullaris and cauda equina (arrowhead) on MRI lumbar spine sagittal T1 post-contrast images. (D) Enhancement and clumping of the cauda equina nerve roots (arrowhead) on MRI lumbar spine axial T1 post-contrast images.

The standardization of neurologic imaging of LM represents a much-needed but controversial topic. Unlike parenchymal brain metastases and extracranial metastases that are more easily defined as target and non-target lesions that may be longitudinally measured,51,52 LM represent a more nebulous disease state to quantify. The RANO Leptomeningeal Metastasis committee (LANO), in an effort to standardize LM measurements across research protocols, published a consensus proposal for multimodality LM response assessments in clinical trials, which includes complementary evaluations of the neurologic examination, CSF cytologic changes, and imaging responses.53 This consensus statement proposed a reproducible imaging scorecard as well as a working guideline for neuraxial MRI protocols, including the use of 1.5 and 3T MRI scanners only, consistency in MRI scanners at baseline and follow-up examination, 3D T1 post-contrast images with isotropic 1 mm voxels to allow for 3-dimensional reformatting of both brain and spine series, and a reformatted slice thickness of 3 mm to enhance detection of small deposits. The RANO working group also discussed the potential value of post-contrast T2-weighted images to better capture non-enhancing and superficial leptomeningeal deposits,54 though have refrained at this time from recommending this sequence for routine assessments.

Following the publication of the original LANO proposal for LM therapeutic response criteria, the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) brain tumor group sought to explore feasibility of the LANO MRI scorecard, finding that neither neuro-oncologists nor neuroradiologists reached acceptable interobserver agreement, due in part to scorecard complexity and lack of systematic user training.55 A revised, simplified MRI scorecard was proposed, with improved, yet still moderate, agreement for overall response assessment (Kappa = 0.44) by a joint EORTC-RANO validation study.56 Standardization of MRI protocols, central imaging review, and sufficient training of local MRI assessments, ideally by board-certified neuroradiologists, were proposed as paths towards better interrater reliability and reproducibility.

We agree with the above proposals and the need for further optimization of these response assessment criteria. We also caution against the use of abbreviated MRI scans with limited series, often prioritized in the clinical setting to maximize efficiency, due to the inferior resolution quality that prevents adequate radiologic interpretation, particularly for spine imaging. Imaging advances such as deep learning reconstruction, undersampling, and other acceleration techniques should be leveraged to acquire the high-quality and 3D images necessary in clinically feasible times.

While the findings of leptomeningeal enhancement in a patient with cancer are commonly the result of metastatic disease, CSF sampling may be necessary to differentiate LM from other radiologic mimics such as immune checkpoint-inhibitor-associated Guillain Barré syndrome57 or early cerebral ischemia.58 However, the concept of “radiographic-only” LM is a true clinical entity, with potentially different biology and prognosis compared to CSF-positive disease and discussed further in “Diagnostic Methods: Liquid Biopsy.” Clinicians should also be mindful of the impairment of tumor-associated contrast enhancement with the concurrent use of anti-angiogenic agents, such as bevacizumab, and thus pursue confirmatory CSF sampling in such patients with “negative” imaging but signs or symptoms of LM.59

Liquid Biopsy

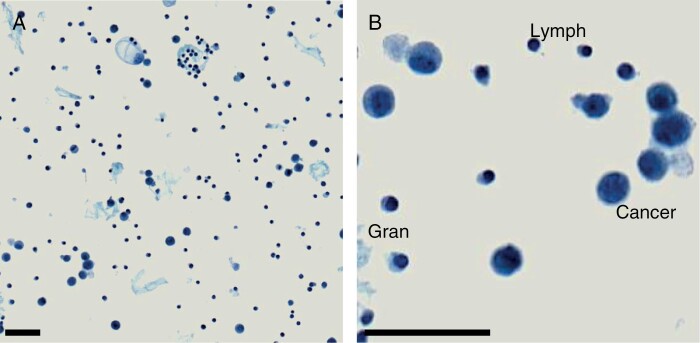

Identification of cancer cells via cytopathologic examination of the CSF is the conventional gold standard for diagnosis of LM, both for clinical practice and research protocol enrollment. This methodology provides a qualitative assessment of the presence or absence of malignant-appearing cells (Figure 3) and is attractive in its accessibility across pathology laboratories. However, existing studies describing the diagnostic utility of MRI sequences compared to CSF cytology, while of mostly poor quality, suggest a poor correlation between these 2 diagnostic techniques. The diagnostic sensitivity of standard cytologic methods ranges from 50% to 90% on the first evaluation, and therefore a second (rarely, a third) CSF analysis of optimal collection is recommended in the setting of an initial negative result to improve diagnostic yield.8,60–62 Common causes of false negative results include low burden of disease, insufficient CSF volume (<5–10 mL), and delay in processing of greater than 30 minutes due to cellular degradation.60,63 Collection of CSF close to regions of abnormal enhancement may also improve diagnostic yield. Ventricular or cisternal CSF collections, when clinically feasible, may be considered in patients with intracranial-only enhancement and negative lumbar sampling. In some cases, the cells are not confirmed as “malignant” cells by the pathologists, but rather as “suspicious” or “atypical” cells, further impeding diagnostic clarity. CSF cytology also fails to provide any quantitative measurement of cancer cell burden, which could be indicative of treatment response.

Figure 3.

Cytospin of CSF from a patient harboring leptomeningeal metastases secondary to breast cancer. (A) Low-power image illustrating abundant cellular material and proteinaceous deposits. (B) High-power image demonstrating major cell types present: Lymph, Lymphocyte; Gran, Granulocyte; Cancer, Cancer Cell. Scale Bar = 50 mm.

The European Association of Neuro-Oncology (EANO) and European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) LM consensus group has proposed differentiating LM as defined by positive CSF cytology (“confirmed” or type I disease) versus clinical and radiographic features-only (“probable/possible” or type II disease),63 and has retrospectively validated type II LM as being associated with superior outcomes.64 The number of lumbar punctures required to define type II LM was not specified; however, EANO-ESMO recommends a second lumbar puncture of optimal conditions if the first result is negative or equivocal.63

To meet the need for enhanced CSF biomarkers, investigational liquid biopsy techniques have evolved considerably with the optimization of cell-free DNA65–69 and rare cell capture technologies.70–74 These techniques serve complementary purposes. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), detectable by an array of testing platforms ranging from single-gene assays to broad next-generation sequencing panels, is relatively more abundant in CSF than in plasma for CNS malignancies and can offer valuable information regarding de novo or acquired genetic alterations of CNS metastases.65–69 Detection of ctDNA may be influenced by variables such as CNS metastasis burden, proximity of sampling site to anatomic enhancing disease, and corresponding DNA quantity. Additionally, parenchymal tumors may also shed ctDNA into the CSF, and so ctDNA provides a “net output” of both parenchymal and LM rather than uniquely identifying leptomeningeal signatures. Rare cell capture technologies, alternatively, isolate and enumerate circulating tumor cells (CTCs) using antibodies specific for markers expressed on cancer cell surfaces. The CellSearch© CTC Test by Menarini Silicon Biosystems, for example, is the only FDA-approved and clinically validated assay for CTC detection from peripheral blood samples in patients with breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer.75 Adaption of this assay to CSF analysis in those with suspected LM has repeatedly shown enhanced diagnostic sensitivity as compared to CSF cytology, correlation with treatment response, and potential prognostic significance.70–74

Before these emerging CSF biomarkers may be integrated into clinical practice, individualized assays must be prospectively analyzed and validated to gain CLIA certification for clinical laboratory testing. At present, the use of these assays is generally only available at highly specialized centers and is further limited by both location and insurance-coverage restrictions. The ideal timing for CSF examination of ultra-sensitive ctDNA and CTCs also warrants further clarification. In clinical practice, the pursuit of these techniques is often only after the radiographic or cytologic diagnosis of CNS metastases. However, CSF examination prior to overt CNS dissemination may allow for sooner detection of early disease states and initiation of CNS-active therapies with potentially higher response potential (NCT05130840). Advanced CSF testing may also open the door to additional therapeutic targets for patients with LM, as well as allow for a more consistent way to follow trends with respect to treatment response.76,77 Analogous to the use of MRI scanning to diagnosis LM, the natural history of this disease as defined by various liquid biopsy techniques is likely to differ substantially from the natural history of CSF cytology-defined or MRI-defined LM. The prognostic implications of detectable CTCs and ctDNA in CSF, and source differentiation of genomic findings between parenchymal and leptomeningeal cancer cells, will therefore need to be determined.

Management

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy has long served as a pillar in the management of LM. In the United States, conventional photon-based involved field radiation therapy (IFRT), such as partial- or whole-brain radiation therapy for cranial disease or focal spine radiation therapy to sites of spinal dissemination, serves to palliate sites of bulky or symptomatic disease.78–81 Dose fractionation typically ranges from 20 to 30 gray in 5–10 fractions. In Europe, partial IFRT is the technique of choice both at the cranial and spinal levels, whereas whole-brain radiation therapy is rarely offered. However, as LM involves the entire neuroaxis, isolated radiation to one region of the leptomeninges does not address the remainder of the compartment and therefore ultimately fails to sufficiently control the disseminated disease. As a result, IFRT has not been demonstrated to reliably improve survival,82,83 and prospective trials comparing radiation strategies in LM are rare (Table 2). Conventional photon-based craniospinal irradiation (CSI) that targets the entire neuroaxis, while employed in several childhood leptomeningeal cancers, can be too toxic in adult patients due to off-target damage to internal organs and myelosuppression of the vertebral bodies.84,85 Proton-beam CSI, conversely, offers more selective treatment of CNS structures due to a tighter range of radiation delivery with limited exit dose, and has emerged as a safer alternative in adults with LM.86–88 In comparison to IFRT, proton CSI offers superior leptomeningeal disease control and improved patient survival due to its ability to cytoreduce all sites of leptomeningeal dissemination, with a comparable toxicity profile in phase I/II studies.87,88 The ideal timing for proton CSI delivery, between patients with newly diagnosed or recurrent/refractory LM, remains to be determined, though patients treated with a lower burden of disease, quantitatively defined by CSF CTC and CSF ctDNA, have generally superior outcomes.88–90 The impact of proton CSI on factors such as blood-brain barrier and blood-CSF-barrier permeability, potential synergism or enhanced toxicity when combined with systemic therapies, and alteration to CSF microenvironment also warrants further investigation. Continued improvement in radiation delivery to optimize disease control while minimizing normal tissue impact should be investigated, such as dose and volume optimization to achieve oncofunctional balance91 and multimodality approaches leveraging tumor and microenvironment biology to improve therapeutic ratios.92–94

Table 2.

Prospective Clinical Trials of Radiation Therapy in LM

| Publication | Protocol | Treatment | N | Cancer type | Median OS | Additional results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| External beam radiation therapy | ||||||

| Yang et al, 2021 | Phase I | Proton CSI (30 Gy) | 24 | Solid tumors | 8.0 months (95% CI: 6.0–NR) | Median CNS PFS = 7.0 months (95% CI: 5–13) |

| Yang et al, 2022 | Phase II | Proton CSI (30 Gy) | 42 | Breast cancer and NSCLC | 9.9 months (95% CI: 7.5–NR) | Median CNS PFS = 7.5 months (95% CI: 6.6–NR) |

| IFRT | 21 | Breast cancer and NSCLC | 6.0 months (95% CI: 3.9–NR) | Median CNS PFS = 2.3 months (95% CI: 1.2–5.8) | ||

| Combination external beam radiation and other therapies | ||||||

| Sause et al, 1988 | Prospective NOS | WBRT (30 Gy) + MTX 7.5 mg/m2 IT | 26 | Solid tumors | 3.1 months (range NA) | Median OS responders = 5.7 months (range NA) Median OS non-responders = 1.8 months (range NA) 3 CR, 5 PR |

| Bokstein et al, 1998 | Prospective NOS | IFRT + MTX 12 mg IT + systemic therapy | 41 | Solid tumors | 4 months (range, 1–37) | RR = 86% Delayed symptomatic leukoencephalopathy = 20% Early IT-related complications = 31% |

| IFRT and/or systemic therapy only | 38 | Solid tumors | 4 months (range, 1–25) | RR = 74% Delayed symptomatic leukoencephalopathy = 0% |

||

| Pan et al, 2016 | Phase II | IFRT (40–50 Gy) + concomitant MTX 12.5–15 mg IT + dexamethasone 5 mg IT | 59 | Solid tumors | 6.5 months (range, 0.4–36.7) | RR = 86.4% 14 CR, 29 OR, 8 PR, 5 SD |

| Pan et al, 2020 | Phase I/II | IFRT (40–50 Gy) + Pemetrexed 10 mg IT + dexamethasone 5 mg IT | 34 | Solid tumors | 5.5 months (range, 0.3–16.6) | RR = 68% Neurologic PFS = 3.5 months (range, 0.3–15.2) |

Abbreviations: LM, leptomeningeal metastases; OS, overall survival; CSI, craniospinal irradiation; Gy, gray; CI, confidence interval, NR, not reached; CNS, central nervous system; PFS, progression-free survival; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; NOS, not otherwise specified; WBRT, whole-brain radiation therapy; MTX, methotrexate; IT, intrathecal; NA, not available; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; IFRT, involved field radiation therapy; RR, response rate; OR, obvious response; SD, stable disease.

A major limiting factor in proton CSI is patient access, as this radiation technique is currently only available at specialized proton centers with sufficient practitioner training. Newer photon-based techniques to minimize off-target toxicity such as volumetric modulated arc therapy, while potentially more accessible to the community than proton centers, require further prospective study for safety before being routinely considered for adults.95,96 Even with the use of protons, common radiation-associated toxicities such as fatigue and cytopenias can still occur and may be significant in a heavily pretreated or elderly patient. In the United States, third-party payers and insurance companies differ in their coverage of proton CSI, though the addition of proton CSI to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) guidelines will help to minimize coverage-associated delays in care. The careful process of proton CSI neuraxial mapping adds additional treatment delay, which can potentially negatively impact the care of patients with limited survival.

Therefore, determination between conventional IFRT and proton CSI in patients with LM must involve careful consideration of the patient’s functional status, extent of active extracranial disease, goals of care, timely access to treatment, and availability of alternative treatments. When the goal of radiation therapy is primarily palliative symptom management, to control a limited number of meningeal nodules, and/or for those with poor risk disease as per National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, IFRT to symptomatic sites of disease is often sufficient. In patients with reasonable performance status, good risk disease, and potentially controllable extracranial disease in whom the goal of treatment is durable disease control within the craniospinal axis, proton CSI should be considered when accessible. When IFRT or CSI are offered, the possible interaction of radiation with systemic or intrathecal pharmacotherapies should also be considered, with necessary washout periods in place to prevent additive toxicities.

Regardless of the use of proton versus photon radiation techniques, assessment of neurocognitive outcomes in patients receiving broad intracranial radiation remains an important and underutilized tool.97,98 Formal neurocognitive assessments and patient-reported outcomes in study endpoint design have been historically limited to radiation trials. These endpoints are also relevant for studies of systemic and intrathecal therapies, particularly as modern therapeutics extend survival in cancer patients.99–102 Neurocognitive assessments are also integral to differentiate the phenotype of therapeutic toxicity from that of leptomeningeal disease progression. While the ideal neurocognitive assessment tools in prospective studies for patients with LM have not been defined as they have been for glioma103,104 and brain metastases,105 important considerations include monitored versus unsupervised assessments, ability to use study staff versus neuropsychology providers for data collection, total duration of testing, and timepoint selection. Similarly, patient-reported outcome questionnaires vary in the constructs they target for measurement (eg, quality of life, symptoms, caregiver assessments, etc.) and user interface (eg, email, app-based, or hand-written format), and ideally would be designed in a manner to maximize patient participation.106

Systemic Therapy

The integration of systemic therapies with appreciable activity in the CNS should be considered in all patients with LM, either in addition to or in lieu of treatment with radiotherapy and intrathecal therapies. Due to limitations posed by the blood-brain and blood-CSF barriers, available systemic therapy options are limited in the face of CNS progression. A number of small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors,107–121 immunotherapies,122–125 and cytotoxic chemotherapies126–130 do have known CNS penetrance and may help to impede hematogenous reseeding in the leptomeninges, but only a handful of CNS-active agents have been prospectively evaluated in LM (Table 3). For many agents, the penetrance of systemic therapies into the CSF may be dose-dependent. Dose escalation protocols with focused CNS response rates and CSF pharmacokinetic analysis, as modeled by osimertinib for epidermal growth factor receptor-mutant lung adenocarcinoma, provide a potential means of optimizing leptomeningeal response rates while balancing toxicities.113,121 The tremendous value of CSF pharmacokinetics also applies to newer antibody-drug conjugates such as trastuzumab deruxtecan, which has demonstrated robust parenchymal brain metastasis responses and suggestion of leptomeningeal activity in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) + breast cancer, despite ambiguity behind mechanisms of penetration of such large conjugated drugs (or rather, cleaved payload) into the CSF.131–133 Smaller single-arm phase II trials of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with LM demonstrated that these agents are safe, with encouraging activity in heavily pretreated patients across multiple cancer types,22,123–125 which needs to be further investigated in larger trials of specific histologies. Genomic sampling of metastatic progression in the brain and leptomeninges should also be explored whenever clinically feasible, as this may uncover targetable mutations unique to the leptomeningeal space and expand systemic treatment options.134,135 Limitations provided in the section “Diagnostic Methods: Liquid Biopsy” should be kept in mind.

Table 3.

Prospective Clinical Trials of Systemic Therapies in LM

| Publication | Protocol | Treatment | N | Cancer type | Median OS | Additional results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecularly targeted therapies | ||||||

| Jackman et al, 2015 | Phase I | High-dose gefitinib 750–1000 mg daily (2 weeks) + maintenance gefitinib 500 mg daily (2 weeks) |

7 | EGFR-mutant NSCLC | 3.5 months (range, 1.6–5.1) | Median neurologic PFS = 2.3 months (range, 1.6–4.0) |

| Tamiya et al, 2017 | Prospective NOS | Afatinib 40 mg daily | 11 | EGFR-mutant NSCLC | 3.8 months (95% CI: 1.1–13.1) | Median PFS = 2.0 months (95% CI: 0.6–5.8) ORR = 27.3% |

| Nanjo et al, 2018 | Prospective NOS | Osimertinib 80 mg daily | 13 | EGFR T790M-positive NSCLC | NR | Median PFS = 7.2 months (95% CI: 4.0–undeterminable) |

| Freedman et al, 2019 | Phase II | Neratinib 240 mg daily + capecitabine 750 mg/m2 twice daily (2 weeks on, 1 week off) |

3 | HER2-positive breast | NA | 1 PR for 7 cycles; 1 SD for 4 cycles; 1 PD in 1 cycle |

| Morikawa et al, 2019 | Phase I | High-dose lapatinib 1000–2000 mg twice daily (day 1–3, day 15–17) + capecitabine 1500 mg twice daily (day 8–14, day 22–28) |

5 | HER2-positive breast | NA | 1 PR, 1 SD Duration of treatment = 0–21.5 + months |

| Nosaki et al, 2020 | Phase II | Erlotinib 150 mg daily | 21 | NSCLC, (EGFR-mutant, N = 17) | 3.4 months (range NA) | CSF cytology clearance rate = 30.0% (95% CI: 11.9–54.3) Median TTP = 2.2 months (range NA) |

| Yang et al, 2020 | Phase I | Osimertinib 160 mg daily | 41 | EGFR-mutant NSCLC | 11 months (95% CI: 8.0–18.0) | LM ORR = 62% (95% CI: 45–78) LM DOR = 15.2 months (95% CI: 7.5–17.5) Median PFS = 8.6 months (95% CI: 5.4–13.7) |

| Park et al, 2020 | Phase II | Osimertinib 160 mg daily | 40 | EGFR T790M-positive NSCLC | 13.3 months (95% CI: 9.1–NR) | Median PFS = 8.0 months (95% CI: 7.2–NR) Intracranial DCR = 92.5% |

| Bauer et al, 2020 | Phase II | Lorlatinib 100 mg daily | 2 | ALK-positive NSCLC | NA | 1 intracranial CR with TTP = 21.9 months 1 intracranial PR with TTP = 11.0 months |

| Tolaney et al, 2020 | Phase II | Abemaciclib 200 mg twice daily +/− endocrine therapy, or abemaciclib 150 mg twice daily with IV trastuzumab | 7 | HR-positive, HER2-negative breast | 8.4 months (95% CI: 3.3–23.5) | Intracranial ORR = 0% Intracranial DCR = 28.6% Median PFS = 5.9 months (95% CI: 0.7–8.6) |

| 3 | HR-positive, HER2-positive breast | NA | Intracranial ORR = 0% Intracranial DCR = 33.3% |

|||

| Lu et al, 2021 | Phase II | Osimertinib 80 mg daily + bevacizumab 7.5 mg/kg q3 weeks | 14 | EGFR-mutant NSCLC | 12.6 months (95% CI: 9.8–21.2) | LM ORR = 50% Median LM PFS = 9.3 months (95% CI: 8.2–10.4) |

| Chow et al, 2022 | Phase II | Ceritinib 750 mg daily | 18 | ALK-positive NSCLC | 7.2 months (95% CI: 1.6–16.9) | ORR = 16.7% (95% CI: 3.6–41.4) DCR = 66.7% (95% CI: 41.0–86.7) Median PFS = 5.2 months (95% CI: 1.6–7.2) |

| Xu et al, 2023 | Prospective NOS | Furmonertinib 160 mg daily +/− anti-angiogenic agents | 16 | EGFR-mutant NSCLC | NA | Median intracranial PFS = 4.3 months (95% CI: 2.1–6.5) |

| Immune checkpoint inhibitors | ||||||

| Long et al, 2018 | Phase II | Nivolumab 3 mg/kg q2 weeks | 4 | Melanoma | NA | No investigator-assessed intracranial response in LM |

| Brastianos et al, 2020 | Phase II | Pembrolizumab 200 mg q3 weeks | 20 | Solid tumors | 3.6 months (90% CI: 2.2–5.2) | Median intracranial PFS = 2.6 months (90% CI: 1.1–5.2) Median OS with PD-L1-positive disease = 3.5 months (95% CI: 0.6–5.2) Median OS with PD-L1-negative disease = 3.1 months (95% CI: 2.1–5.2) |

| Naidoo et al, 2021 | Phase II | Pembrolizumab 200 mg q3 weeks | 13 | Solid tumors | 4.9 months (95% CI: 3.7—NR) | Median CNS PFS = 2.9 months (95% CI: 1.3–NR) CNS response at 12 weeks = 38% (95% CI: 13.9–68.4) 2 CR, 1 PR, 2 SD |

| Brastianos et al, 2021 | Phase II | Ipilimumab + Nivolumab (dosing varied by histology) |

18 | Solid tumors | 2.9 months (90% CI: 1.6–5.0) | Median intracranial PFS = 1.9 months (90% CI: 1.3–2.7) |

| Cytotoxic chemotherapy | ||||||

| Segura et al, 2012 | Phase II | Temozolomide 100 mg/m2 (1 week on, 1 week off) | 19 | Solid tumors | 43 days (95% CI: 28.7–57.3) | CBR = 15.8% Median TTP = 28 days (95% CI: 14–42) |

| Wu et al, 2015 | Pilot | Bevacizumab 15 mg/kg (day 1), etoposide 70 mg/m2/day (days 2–4), cisplatin 70 mg/m2/day (day 2) q3 weeks | 8 | Breast | 4.7 months (95% CI: 0.3–9.0) | CNS RR = 60% Neurologic PFS = 4.7 months (95% CI: 0–10.5) |

| Melisko et al, 2019 | Phase II | Irinotecan 125 mg/m2 (days 1 and 15) + temozolomide 100 mg/m2 (days 1–7, days 15–21) of 28-day cycle | 8 | Breast | 3.0 months (range NA) | TTP = 2.0 months (range NA) No responses in LM cohort |

| Kumthekar et al, 2020 | Phase II | ANG1005 600 mg/m2 q3 weeks | 28 | HER2-positive and HER2-negative breast | 8.0 months (95% CI: 5.4–9.4) | Intracranial ORR = 17% (95% CI: 4.7–37.4) Intracranial CBR = 79% (95% CI: 57.8–92.9) Median intracranial PFS = 14.9 weeks (95% CI: 12.7–23.4) |

Abbreviations: LM, leptomeningeal metastases; OS, overall survival; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; PFS, progression-free survival; NOS, not otherwise specified; CI, confidence interval; ORR, objective response rate; NR, not reached; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; NA, not available; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; TTP, time to progression; DOR, duration of response; DCR, disease control rate; ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; CR, complete response; IV, intravenous; HR, hormone receptor; PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1; CNS, central nervous system; CBR, clinical benefit rate; RR, response rate.

A commonly encountered question in patients with LM is how to best manage neuro-systemic dissociation in treatment response. When faced with both intracranial and extracranial progression, prioritization of systemic therapies with expected CNS activity is recommended whenever possible. However, with these agents, it is often unclear how well the parenchymal responses correlate with leptomeningeal activity given varying permeabilities through the blood-brain and blood-CSF barriers,136 and underscores the importance of exploratory CSF pharmacokinetic endpoints in trial design. In patients with isolated leptomeningeal progression with controlled extracranial disease, the optimal timing for systemic therapy change vis-à-vis local therapies (leptomeningeal irradiation and/or intrathecal therapy) is less clear. Hesitation to adjust systemic agents at the risk of extracranial breakthrough is a valid concern, but this must be balanced against the high likelihood of persistent LM reseeding from metastatic cells presumably homing from the peripheral vasculature. A better understanding of which combinations of intrathecal, radiation, and systemic therapies will achieve maximal synergistic antitumor activity while minimizing toxicities is a critically important question that warrants further investigation. For example, combining stereotactic radiosurgery to parenchymal brain metastases with immunotherapy may be correlated with abscopal and additive responses due to well-described immunomodulatory radiotherapy effects.137–142 The utility of applying this same philosophy to IFRT (NCT03719768) or proton CSI in the setting of LM remains to be explored. Similarly, novel radiosensitizers under investigation in brain metastases merit investigation in the leptomeningeal domain. An improved understanding of leptomeningeal responses and resistance mechanisms to different classes of systemic therapies will guide treatment decisions, and further translational study of leptomeningeal escape pathways from different therapeutic pressures is essential.

Intrathecal Therapy

LM therapies have not only evolved for systemic administration in the last 2 decades, but also for intrathecal administration (Table 4). Intrathecal drug administration is generally most effective against floating and thin linear deposits of LM in patients with unobstructed CSF flow dynamics, whereas bulky and nodular LM (> 2–3 mm in thickness) tend to be less responsive to this approach. Traditionally, intrathecal chemotherapy has been limited to a handful of drugs largely tested between the late 1970s and early 2000s: Methotrexate, thiotepa, cytarabine, and topotecan.143–156 These historical clinical trials all uncovered similar survival outcomes, varying from 2 to 4 months, without clear superiority of one agent over another. However, with newer cancer therapies and a reinvigorated interest in clinical trials for patients with CNS metastases, intrathecal therapies have reentered the experimental marketplace. Intrathecal formulations of trastuzumab,157–159 nivolumab,160 and pemetrexed81,161–163 have all demonstrated reasonable safety profiles and hints of superior survival compared to historical controls in independent prospective phase I/II studies. One fully enrolled randomized phase III showed the superiority of adding intrathecal liposomal cytarabine to systemic pharmacotherapy by prolonging leptomeningeal progression-free survival,164 although this drug has since been discontinued due to manufacturing issues.165,166 Studies of intrathecal pertuzumab (NCT05805631), immune checkpoint inhibitors (NCT03025256, NCT05112549, and NCT05598853), immune effector cells (NCT05809752 and NCT03696030), and deferoxamine (NCT05184816) are ongoing. Applications of intraventricular compartmental radioimmunotherapy have also emerged,167–169 with 131-I-omburtamab showing bioactivity in patients with primary and secondary leptomeningeal brain tumors; however, this therapy failed to meet FDA approval for use in medulloblastoma. A study of rhenium-186 nanoliposomes in patients with solid tumor LM is still accruing patients (NCT05034497) and this treatment was recently granted orphan drug designation by the FDA in the treatment of patients with breast cancer LM.

Table 4.

Prospective Clinical Trials of Intrathecal Therapies in LM

| Publication | Protocol | Treatment | N | Cancer type | Median OS | Additional results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrathecal therapies | ||||||

| Gutin et al, 1977 | Phase II | Thiotepa 10 mg/m2 IT and 10 mg IT | 13 | Solid and hematologic tumors | NA | 8 CR, 2 PR, 3 PD |

| Hitchins et al, 1987 | RCT | MTX 15 mg IT | 22 | Solid and hematologic tumors | 12 weeks, (range, 1–152) | RR = 61% concurrent IFRT, N = 11 |

| MTX 15 mg IT + cytarabine 50 mg/m2 IT | 20 | Solid and hematologic tumors | 7 weeks, (range, 1–105) | RR = 45% concurrent IFRT, N = 11 |

||

| Meyers et al, 1991 | Phase II | Alpha interferon 1 × 106 IU/mg protein IT | 9 | Solid and hematologic tumors | 4 months (range, 1–10) | RR = 44% significant neurotoxicity = 78% |

| Grossman et al, 1993 | RCT | MTX 10 mg IT | 28 | Solid and hematologic tumors | 15.9 weeks (range, 4 days—61.3 weeks) | 0 CR, 9 SD, 19 PD concurrent IFRT allowed |

| Thiotepa 10 mg IT | 24 | Solid and hematologic tumors | 14.1 weeks (range, 4 days—61.3 weeks) | 0 CR, 3 SD, 20 PD concurrent IFRT allowed |

||

| Chamberlain et al, 1996 | Phase II | MTX 2 mg IT (first line), cytarabine 30 mg IT (second line), thiotepa 10 mg IT (third line) | 16 | Melanoma | 4 months (range, 2–8) | IT MTX RR = 25% (total N = 16) IT cytarabine RR = 38% (total N = 13) IT thiotepa RR = 28% (total N = 7) preceding IFRT, N = 14 |

| Chamberlain et al, 1998 | Prospective NOS | MTX 2 mg IT (first line), cytarabine 30 mg IT (second line), thiotepa 10 mg IT (third line) | 32 | NSCLC | 5 months (range, 1-12) | IT MTX RR = 43% (total N = 32) IT cytarabine RR = 50% (total N = 16) IT thiotepa RR = 33% (total N = 6) preceding IFRT, N = 16 |

| Glantz et al, 1999 | Phase III | Liposomal cytarabine 50 mg IT | 31 | Solid tumors | 105 days (range NA) | RR = 26% median TTNP = 58 days median LM-specific survival = 343 days |

| MTX 10 mg IT | 30 | Solid tumors | 78 days (range NA) | RR = 20% Median TTNP = 30 days median LM-specific survival = 98 days |

||

| Esteva et al, 2000 | Phase II | Cytarabine 100 mg IT | 10 | Breast | 30 weeks (range, 5–58 weeks) | RR = 22% (95% CI: 3–60) preceding IFRT, N = 2 |

| Orlando et al, 2002 | Phase II | Thiotepa 10 mg IT, MTX 15 mg IT, hydrocortisone 30 mg IT (day 1) + cytarabine 70 mg IT, MTX 15 mg IT, hydrocortisone 30 mg IT (day 5) | 13 | Breast | NA | No observed response or clinical improvement in symptoms concurrent WBRT, N = 7 |

| Jaeckle et al, 2002 | Phase IV | Liposomal cytarabine 50 mg IT | 110 | Solid tumors | 95 days (range, 7–791+) | RR = 27% (95% CI: 17–39) median TTNP = 55 days (range, 0–584+) median LM-specific survival = 170 days (range, 7–791) concurrent IFRT, N = 24 |

| Chamberlain et al, 2002 | Phase II | Alpha interferon 1 × 106 IU IT | 22 | Solid and hematologic tumors | 18 weeks (range, 5–69) | RR = 45% median DOR = 16 weeks (range, 8–40) chronic fatigue (KPS reduction of 20 points after induction and 30 points during maintenance) = 91% concurrent IFRT, N = 12 |

| Chamberlain et al, 2006 | Phase II | Etoposide 0.5 mg IT | 27 | Solid and hematologic tumors | 10 weeks (range, 4–52) | RR = 27% median TTNP = 20 weeks (range, 8–40) 6-month neurologic PFS = 11% |

| Groves et al, 2008 | Phase II | Topotecan 0.4 mg IT | 62 | Solid and hematologic tumors | 15 weeks (95% CI: 13–24) | RR = 21% median TTP = 7 weeks (95% CI: 6–11) 13-week neurologic PFS = 30% (95% CI: 20–45) |

| Ursu et al, 2015 | Phase I | CpG-28 IT and SQ | 29 | Solid tumors | 15 weeks (range, 3–300) | median PFS = 7 weeks (range, 1–81) |

| Bonneau et al, 2018 | Phase I | Trastuzumab 30–150 mg IT (MTD = 150 mg IT) | 16 | HER2-positive breast | 7.3 months (range, 12 days—27.9 months) | 2 CR, 6 SD, 4 PD |

| Mrugala et al, 2019 | Phase II | Liposomal cytarabine 50 mg IT + HD-MTX 8g/m2 | 3 | Breast | 8.2 months (range, 5.5–11.3) | median PFS = 1.4 months (range, 1.3–8.2) |

| Pan et al, 2019 | Phase I | Pemetrexed 10–15 mg IT (MTD = 10 mg IT) | 13 | NSCLC (EGFR-mutant or ALK-positive, N = 11) | 3.8 months (range, 0.3–14) | RR = 31% DCR = 54% median neurologic PFS = 2.5 months (range, 0.3–12.5) |

| Fan et al, 2021 | Phase I/II | Pemetrexed 50 mg IT + dexamethasone 5 mg IT | 30 | EGFR-mutant NSCLC | 9.0 months (95% CI: 6.6–11.4) | Clinical RR = 84.6% 2 CR, 13 OR, 7 PR, 3 SD, 1 PD |

| Li et al, 2023 | Phase I | Pemetrexed 30–50 mg IT (RD = 30 mg IT) | 23 | EGFR-mutant and ALK-positive NSCLC | 9.5 months (range, 2.9—NR) | ORR = 43.5% (95% CI: 23.2–63.8) DCR = 82.6% (95% CI: 61.2–95.0 median PFS = 6.3 months (range, 0.8—NR) |

| Kumthekar et al, 2023 | Phase I/II | Trastuzumab 10–80 mg IT (RP2D = 80 mg) | 34 | HER2-positive cancers | 8.3 months (95% CI: 5.2–19.6) at RP2D (N = 26) | Median PFS = 2.2 months (95% CI 1.0–7.4) at RP2D (N = 26) In HER2-positive breast cancer patients at RP2D (N = 23), median PFS = 2.8 months (95% CI 1.8–7.8) and median OS = 10.5 months (95% CI 5.2–20.9) |

| Oberkampf et al, 2023 | Phase II | Trastuzumab 150 mg IT |

19 | HER2-positive breast | 7.9 months (range, 0.2–27.8+) | Median LM-PFS = 5.9 months (range, 0.2–25.5) |

| Combination of intrathecal and systemic therapies | ||||||

| Boogerd et al, 2004 | RCT | PBC + MTX 10 mg IT (first line), cytarabine 40 mg IT (second line) | 17 | Breast | 18.3 weeks (standard error 6.7) | Median TTNP = 23 weeks neurologic improvement = 41% and stabilization = 18% neurologic toxicity = 47% |

| PBC without IT chemotherapy | 18 | Breast | 30.3 weeks (standard error 10.9) | Median TTNP = 24 weeks neurologic improvement = 39% and stabilization = 28% neurologic toxicity = 6% |

||

| Le Rhun et al, 2020 | Phase III | PBC + liposomal cytarabine 50 mg IT | 36 | Breast | 7.3 months (95% CI: 3.9–9.6) | Median LM-PFS = 3.8 months (95% CI: 2.3–6.8) |

| PBC without IT chemotherapy | 37 | Breast | 4.0 months (95% CI: 2.2–6.3) | Median LM-PFS = 2.2 months (95% CI: 1.3–3.1) | ||

| Glitza Oliva et al, 2023 | Phase I | Nivolumab 5–50 mg IT (RD = 50 mg IT) + Nivolumab 240 mg IV q2 weeks | 25 | Melanoma | 4.9 months (range NA) | OS at 26 weeks = 44% OS at 52 weeks = 26% |

| Intrathecal radiolabeled isotopes | ||||||

| Coakham et al, 1998 | Phase I | 131 I- monoclonal antibodies | 40 | Solid and hematologic tumors | NA | Mean OS = 39 months in responders, 4 months in non-responders OS at 1 year = 50% |

| Tringale et al, 2023 | Phase I | 131-I-omburtamab | 27 | Primary brain leptomeningeal tumors (20 medulloblastoma, 7 ependymoma) | Medulloblastoma: 1.9 years (95% CI 0.9–10.9) Ependymoma: 6.7 years (95% CI: 0.4–12.9) |

Medulloblastoma median PFS = 0.4 years (95% CI: 0.1–1.7) Ependymoma median PFS = 0.4 years (range, 0.2–1.9) |

Abbreviations: LM, leptomeningeal metastases; OS, overall survival; IT, intrathecal; NA, not available; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; PD, progressive disease; RCT, randomized controlled trial; MTX, methotrexate; RR, response rate; IFRT, involved field radiation therapy; SD, stable disease; NOS, not otherwise specified; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; TTNP, time to neurologic progression; WBRT, whole-brain radiation therapy; DOR, duration of response; KPS, Karnofsky performance status; PFS, progression-free survival; CI, confidence interval; CpG, cytidine phosphate guanosine; SQ, subcutaneous; MTD, maximum tolerated dose; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; HD, high dose; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; DCR, disease control rate; OR, obvious response; RD, recommended dose; ORR, objective response rate; RP2D, recommended phase II dose; PBC, physician’s best choice systemic and, if needed, radiation therapy; IV, intravenous.

The renewed interest in intrathecal drug development of the last decade is accompanied by several unanswered questions in drug selection, dosing, and investigation. Which FDA-approved drugs for systemic applications should be prioritized for intrathecal reformulation: those without robust CSF penetration or those with sufficient scientific rationale in the leptomeninges? Both in the right clinical context are reasonable grounds for further study; however, one must consider whether drug activity might be altered by the unique leptomeningeal immune landscape and hypoxic, low pH CSF microenvironment. How can we streamline preclinical experimentation for dose-finding strategies and conversion to safe human starting doses? Human equivalent dosing is often estimated based on allometric scaling from the no observed adverse effect level in animal models.170 However, the added complexities of intrathecal compartment volumes, drug half-lives, and CSF clearance rates further complicate simple dose conversions between species. What best clinical practices should apply to intrathecal drug volume, suspension, and preparation? Do all patients require dynamic intrathecal radioisotope CSF flow studies prior to investigational drug delivery?171 We agree that routine CSF flow studies are unnecessary in the absence of clinical suspicion for CSF block and pose the risk of adding unnecessary delay without definitive clinical value.172 How does one best manage patients with concurrent parenchymal brain metastases or nodular leptomeningeal disease, given the lack of intrathecal drug penetrance for these 2 scenarios? Applications of drug delivery to the leptomeningeal compartment are expected to grow as we learn more about the nuances of the CSF microenvironment and as systemic therapies evolve.

The consensus group favors the conduct of clinical studies with translational programs to establish pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic metrics for emerging intrathecal therapeutics. Safety and preliminary efficacy results from phase I/II trials should be confirmed in phase III trials in patients with LM, as for all other cancer patients.

Surgical Interventions

The 2 neurosurgical devices used in patients with LM are ventricular access devices (eg, Ommaya reservoir) and extracranial CSF shunts, which include ventriculoperitoneal, ventriculopleural, ventriculoatrial, and lumboperitoneal catheters. While these devices serve different purposes in patients with LM, the optimal timing of device placement and role in best clinical and research practices vary widely by clinician and institutional preferences.

Ommaya reservoirs have several key advantages over serial lumbar punctures, which are inconvenient for frequent CSF sampling and drug delivery. For the patient, Ommaya reservoirs help to reduce anxiety and discomfort related to CSF access, avoid complications inherent to lumbar punctures (eg, post-dural puncture headaches, low back pain, and radiculopathy), and obviate the need for anticoagulation holds. For the clinician, Ommaya reservoirs can allow for more frequent and reliable monitoring of CSF cytology for therapeutic response. Importantly, compared to lumbar puncture drug administration, intraventricular administration improves drug dissemination through the intrathecal space due to principles of pulsatile CSF flow and gravitational influences.161,173,174 Intraventricular drug delivery has been associated with improved survival compared to lumbar drug delivery, in a study largely controlled for potentially confounding functional status differences between these 2 patient cohorts.175 These benefits also extend to clinical research, in the case of therapeutic drug trials which require timely and reliable CSF sampling for pharmacokinetic modeling.

Historically, complications related to Ommaya reservoir placement and use had been estimated in approximately 10% of patients, with up to 15% experiencing peri-operative or delayed bacterial infections.176 More modern publications suggest a substantially lower complication risk related to Ommaya implantation and repetitive access (1.8%–9.8%), necessitating Ommaya revision in < 5% of patients. Contemporary Ommaya-related complications include infection (peri-operative 0.9%–2.7% vs. delayed 2.8%–3.8%), peri-operative hemorrhage (0.9%–6.4%), Ommaya malfunction (peri-operative 1.1%–2.8% vs. delayed 0.9%), wound dehiscence (1.8%), and catheter tract leukoencephalopathy/edema (1.8%).177–179 These risks may be mitigated in the hands of experienced surgeons and sterile access techniques. Another important consideration is the inherent differences in cancer cell enumeration for diagnostic purposes and drug measurements between lumbar and intraventricular sampling, which should be considered in clinical and research practices.174

Given the risk-benefit analysis and differences in institutional practices, consensus is lacking with respect to the indication and timing of Ommaya reservoir placement. In patients undergoing intrathecal chemotherapy administration, anticipating frequent lumbar puncture assessments, and in clinical research settings, early Ommaya reservoir placement should be strongly considered, particularly in high-volume centers with the appropriate clinical expertise.

Extracranial CSF shunts, alternatively, are purely palliative devices, aimed at alleviating symptoms associated with hydrocephalus and elevated intracranial pressure. In those patients with symptomatic intracranial pressure elevations, extracranial shunting provides symptomatic relief in over 80% of patients and allows for the majority to continue with cancer-directed therapy.180–182 The major disadvantages to CSF diversion devices are an approximate 15%–20% risk of complications (eg, infection, subdural hygroma/hematoma, and malfunction) and the challenges associated with subsequent intrathecal chemotherapy. In the event of programmable extracranial shunts with the ability to manually adjust the shunt, intrathecal chemotherapy may be subsequently administered, however with no data to determine the appropriate duration of shunt “idling” before resuming shunt drainage. Therefore, for clinical research protocols of intrathecal therapies, we strongly discourage concurrent placement of an extracranial CSF shunt as this may lead to heterogeneous drug distribution, peritoneal complications, and altered study endpoint measurements.

Timing of CSF flow diversion in clinical practice should be determined by careful examination of symptoms and intracranial pressure measurement, patient preferences, neurosurgical expertise, and goals of care. Temporization of elevated intracranial pressure by CSF removal via Ommaya or lumbar puncture often only serves as a bridge to more permanent CSF diversion. The impact of neuraxial irradiation on intracranial pressure dynamics, and therefore timing for shunt placement in high-risk patients, is more complex. Radiation to intracranial or spinal sites of CSF blockages improves CSF flow in a proportion of patients as assessed by radioisotope flow studies.171,183 Therefore, prophylactic shunting is not necessary in the asymptomatic patient without confirmed or suspicion of elevated intracranial pressure. However, cranial irradiation may also induce headaches, nausea, and vomiting often in a corticosteroid-responsive and at times pressure-dependent manner, and such patients may benefit from lumbar puncture to both confirm and reduce intracranial pressure.184,185

Clinical Trial Design

Clinical trials developed specifically for patients with LM are both feasible and urgently needed. Trial design in this patient population is far from standardized, with high inter-trial variability in patient population, endpoint selection, and response evaluability due to the relative infrequency of this disease state and the aforementioned challenges associated with diagnostic sensitivity.

In terms of the patient population, clinical investigators vary in their “definition” of LM for study inclusion based on positive CSF cytology, neuroimaging studies, or both. CSF cell capture techniques, while more sensitive and quantifiable than CSF cytology,70–73 require validation and widespread availability before this technique can replace CSF cytology in clinical research platforms. Therapeutic protocols for patients with LM should encourage the inclusion of CSF CTCs and CSF ctDNA as an exploratory endpoint to more prospectively validate these assays. Trials can be designed as either a basket study offering enrollment to patients with LM from any solid tumor malignancy or restricted to a specific cancer subtype to study a more uniform patient population. In phase I studies, broad eligibility in both inclusion criteria and cancer of interest is reasonable when the purpose of the study is to assess safety. However, for phase II/III studies evaluating the efficacy, stricter eligibility requirements, including a complete LM diagnostic work-up (ie, baseline clinical, imaging, and CSF assessments) and restriction to solitary cancer types, are preferred as these would introduce less molecular and treatment heterogeneity into outcome measurements. In this setting, multi-site collaboration and randomized controlled studies should be encouraged, whenever possible, both to accelerate study execution and improve the reliability of study conclusions.

Speed of patient registration and drug initiation is also critically important. Given the rapidity of LM progression without treatment, delays surrounding screening studies and treatment initiation that may be acceptable for other neuro-oncologic diseases (ie, 14–21 days) are detrimental for LM and may result in clinical deterioration before the patient even begins the study. This is of particular importance in trials that require preemptive Ommaya reservoir placement or complex radiation treatment planning.

With respect to study objectives in clinical trials of LM, the primary endpoint of overall survival has historically been chosen over leptomeningeal response. This is in contrast to the large majority of studies for parenchymal brain metastases and extracranial malignancies, in which objective response measures provide more granularity with respect to drug response and durability. Due to the lack of validated response measures in LM and the inherent challenges of assessing “response” in LM, the selection of a survival benefit provides the most objective outcome measure and a layer of comparability across other studies. Joint efforts by LANO and the EORTC brain tumor group to standardize leptomeningeal response assessments have already validated an MRI scorecard for clinical trial use, as outlined in the “Diagnostic Methods: Radiology” section.53,55,56 Further validation and likely refinement are yet required for all components of LANO-proposed LM response assessment, including not only radiographic changes but also cytologic response, clinical examination, and corticosteroid use.53

Given that LM are a compartmental disease, therapeutic intervention in clinical trial design also must consider the status of other CNS metastases and extracranial disease. For example, does the therapy under investigation also treat parenchymal brain metastases and systemic disease, or is it a compartment-specific intervention such as the case with intrathecal and certain radiotherapies? In the case of systemic therapies with CNS bioactivity, the selection of progression-free survival as a study endpoint, with care to distinguish the site of progression and whether intracranial progression was from that of parenchymal versus LM, would be reasonable upon proper validation of LM response assessments. In the case of local therapies, alternatively, how does one allow for inclusion of systemic therapy and how would this influence response endpoint evaluability? Should neurologic symptom burden be considered in response endpoints in these scenarios, considering that symptoms from local treatment-related toxicity and leptomeningeal progression often overlap and so attribution may be challenging? Similarly, systemic therapy trials should have prespecified analyses to allow for CNS compartment-specific therapies (radiation and/or intrathecal therapy) for patients with intracranial progression on-study who are otherwise deriving benefits in their systemic disease.

Encouragement of multi-institutional studies to include high-volume centers will help to speed patient enrollment and prevent early termination due to slow accrual and funding withdrawal. While randomized controlled studies should be encouraged whenever robust patient enrollment is anticipated, recent history does not encourage us to expect sufficient enrollment in randomized studies to provide adequate patient numbers to interrogate critical questions about prognostic variables like specific histologies, molecular subtypes, or even age or performance status. The use of well-designed registry trials, employing statistical techniques such as propensity score matching, might offer a useful alternative “synthetic control” to randomized controlled trials. In addition, protocols that include evaluation of patients with brain metastases should include, whenever possible, a dedicated arm for patients with LM plus exploratory pharmacokinetic analyses in the CSF, to better identify drugs with potent blood-CSF barrier penetration and potential for further focused study.

Novel Therapeutics

The number of large phase II/III academic and pharmaceutical industry-sponsored trials for patients with solid tumors dwarfs the number of protocols dedicated to CNS metastases. Therefore, advocacy efforts to include patients with LM in these studies, whether as an individual or exploratory cohort, should continue. However, the durability of leptomeningeal disease control, even in the case of more modern targeted and immune-stimulating therapeutics, remains short-lived, likely due to intrinsic nuances of leptomeningeal cancer cell biology, the sparse and immunosuppressive CSF microenvironment, and barrier limitations to drug delivery. The key to more effectively eradicating LM may therefore lie in manipulating the unique mechanisms that facilitate metastasis tenacity and drug resistance in the leptomeningeal space.

Investigational approaches currently in development that are unique to the leptomeninges (Table 5) can be generally divided into 4 categories: Translational approaches targeting leptomeningeal cancer cell metabolism, therapeutics which enhance LM interactions with the local immune microenvironment, intraventricularly delivered radioactive particles, and reformulated/conjugated drugs to enhance delivery through or bypass the blood-CSF barrier. This is in addition to a generally larger number of studies applying investigational or FDA-approved systemic therapies to CNS metastasis cohorts, either alone or in combination with radiation therapy, to better elucidate brain and leptomeningeal responses.

Table 5.

Prospective Trials of Novel Therapeutics in LM

| NCT | Drug | Patient population |

|---|---|---|

| Leptomeningeal metastasis metabolism | ||

| NCT05184816 | IT deferoxamine | Solid tumors |

| Local immunomodulatory therapies | ||

| NCT03025256 | IT and IV nivolumab | Melanoma |

| NCT05112549 | IT nivolumab | Solid tumors |

| NCT05598853 | IT nivolumab/ipilimumab | NSCLC |

| NCT03696030 | IT HER2-CAR T cells | HER2 + solid tumor |

| NCT05809752 | IT Her2/3-Dendritic Cells | HER2 + or triple-negative breast cancer |

| Conjugated systemic therapies to enhance blood-CSF barrier penetration | ||

| NCT05305365 | QBS72S | Breast cancer |

| NCT03613181 | ANG1005 | Breast cancer |

| Molecular or immune-targeting therapies | ||

| NCT05805631 | IT pemetrexed | EGFR-mutant NSCLC |

| NCT05800275 | Capecitabine, tucatinib, and IT trastuzumab | HER2 + breast cancer |

| NCT04965090 | Amivantamab and lazertinib | EGFR-mutant NSCLC |

| NCT04729348 | Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab | Solid tumor |

| NCT04420598 | Trastuzumab deruxtecan | HER2 + and HER2-low breast cancer |