Abstract

PROTON GRADIENT REGULATION5 (PGR5) is thought to promote cyclic electron flow, and its deficiency impairs photosynthetic control and increases photosensitivity of photosystem (PS) I, leading to seedling lethality under fluctuating light (FL). By screening for Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) suppressor mutations that rescue the seedling lethality of pgr5 plants under FL, we identified a portfolio of mutations in 12 different genes. These mutations affect either PSII function, cytochrome b6f (cyt b6f) assembly, plastocyanin (PC) accumulation, the CHLOROPLAST FRUCTOSE-1,6-BISPHOSPHATASE1 (cFBP1), or its negative regulator ATYPICAL CYS HIS-RICH THIOREDOXIN2 (ACHT2). The characterization of the mutants indicates that the recovery of viability can in most cases be explained by the restoration of PSI donor side limitation, which is caused by reduced electron flow to PSI due to defects in PSII, cyt b6f, or PC. Inactivation of cFBP1 or its negative regulator ACHT2 results in increased levels of the NADH dehydrogenase-like complex. This increased activity may be responsible for suppressing the pgr5 phenotype under FL conditions. Plants that lack both PGR5 and DE-ETIOLATION-INDUCED PROTEIN1 (DEIP1)/NEW TINY ALBINO1 (NTA1), previously thought to be essential for cyt b6f assembly, are viable and accumulate cyt b6f. We suggest that PGR5 can have a negative effect on the cyt b6f complex and that DEIP1/NTA1 can ameliorate this negative effect.

By screening for pgr5 suppressors, we identified mutations affecting 12 photosynthesis-related proteins, including a cyt b6f assembly factor and a factor linking PGR5 to cyt b6f stability.

Introduction

Under natural conditions, plants experience continuous changes in light intensity each day, for example, due to cloud cover and canopy shading. Under low light (LL) conditions, maximum light absorption and energy utilization are required to meet metabolic needs through photosynthesis. However, excess light can lead to the production of harmful reactive oxygen species (ROS) and cause irreversible damage to the photosynthetic apparatus or photoinhibition. Therefore, acclimation to light fluctuations is a crucial and adaptive response for photosynthetic organisms to maximize their efficiency in capturing light energy while minimizing the potential damage caused by excessive light exposure (reviewed by Long et al. (2022) and Leister (2023)).

During photosynthesis, electrons are mainly transported from water to the final acceptor NADP+ in the thylakoid membranes of chloroplasts via photosystem (PS) II (PSII), cytochrome b6f (cyt b6f), and PS I (PSI). In the process, a trans-thylakoid proton gradient is generated. The end products are ATP and NADPH, which are required for subsequent reactions. This electron transport is known as linear electron flow (LEF). In addition, other electron transport pathways exist, such as cyclic electron flow (CEF), in which electrons from PSI are transferred via ferredoxin (Fd) back to the plastoquinone (PQ) pool and cyt b6f, maintaining the formation of the proton gradient and thus the synthesis of ATP but without net production of NADPH (reviewed in Shikanai and Yamamoto (2017) and Leister (2020)). Hence, the balance between the rates of LEF and CEF is crucial for plant acclimation by adjusting the ATP/NADPH ratio. Furthermore, the proton gradient formed across the thylakoid membrane during both LEF and CEF is required for the activation of a series of protective mechanisms, such as “nonphotochemical quenching” (NPQ), which allows the thermal dissipation of the excess absorbed light energy and the downregulation of the cyt b6f complex or “photosynthetic control” (reviewed in Shikanai and Yamamoto (2017)). Consequently, the luminal pH acts as a sensor of excess light, leading to a balance between energy utilization and energy dissipation.

The mechanism and components of CEF in flowering plants are still largely unclear. One CEF pathway involves the NADH dehydrogenase-like complex (NDH) (reviewed in Yamori and Shikanai (2016)). A second CEF pathway is thought to be sensitive to the antibiotic antimycin A (Tagawa et al. 1963), and the thylakoid PROTON GRADIENT REGULATION5 (PGR5) protein has been proposed to be involved in this pathway based on the characterization of its mutant phenotype (Munekage et al. 2002). Comparative analyses of mutant phenotypes specific to the two pathways suggest that the PGR5-dependent pathway dominates in C3 plants (Munekage et al. 2004), whereas the NDH-dependent pathway is more important in C4 plants (Ogawa et al. 2023). PGR5 is a peripheral thylakoid protein associated with PSI that interacts with and is regulated by the two integral thylakoid proteins PGR5-like 1 (PGRL1) (DalCorso et al. 2008) and PGR5-like 2 (PGRL2) (Rühle et al. 2021). Since PGR5 lacks motifs or cofactors that qualify it as an electron transporter, alternative functions of PGR5 and other possible pathways of CEF have been hypothesized. Thus, it was suggested that PGR5 regulates CEF rather than directly participating in the process (e.g. Nandha et al. 2007). Alternatively, PGR5 was proposed to regulate proton efflux from the thylakoid membrane in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) (Avenson et al. 2005). However, the experimental basis of this hypothesis has been questioned (Yamamoto and Shikanai 2020). Additionally, a CEF pathway involving electron transfer from Fd to a unique c-type heme (Kurisu et al. 2003) in cyt b6f was proposed, either bypassing PGR5 and NDH (Ohnishi et al. 2023) or involving an alternative mode of the Q cycle in Chlamydomonas (Buchert et al. 2020). Again, this concept is in contrast to other experiments (Okegawa et al. 2005, Shikanai 2023). In conclusion, the molecular function of PGR5 in CEF remains unclear (Shikanai 2023). Additionally, the lack of a universally accepted method to directly measure CEF makes it difficult to unambiguously prove or disprove hypothetical CEF pathways. Nevertheless, it is undisputed that in the absence of PGR5, specifically in pgr5 and pgrl1ab mutants, PSI can be inhibited depending on light intensity and CO2 supply (Munekage et al. 2002; DalCorso et al. 2008; Munekage et al. 2008).

Defective PGR5-dependent CEF leads to reduced acidification of the lumen, which decreases ATP production that in turn causes overreduction of the stroma due to the reduced ATP/NADPH ratio. It also prevents the induction of NPQ and the downregulation of the cyt b6f complex, leading to an overreduction of PSI. Indeed, plants lacking PGR5 exhibit a pleiotropic phenotype, where the effect on CEF is not easily disentangled from other processes such as stromal overreduction with high PSI acceptor side limitation and reduced proton motive force (pmf) due to high ATPase conductance caused by stromal ATP depletion (Avenson et al. 2005; Munekage et al. 2008). Under FL, this complex defect due to PGR5 deficiency is lethal (Tikkanen et al. 2010; Suorsa et al. 2012), highlighting the importance of this protein for plant survival, as changes in light intensity can occur very rapidly in field canopies. Accordingly, increasing the electron sink capacity of PSI, i.e. decreasing the PSI acceptor side limitation, by adding methyl viologen (Munekage et al. 2002) or overexpressing flavodiiron proteins from Physcomitrium patens in Arabidopsis pgr5 (Yamamoto and Shikanai 2019), partially rescues the pgr5 photosynthetic phenotype. In addition, decreased electron transport rates from PSII to PSI, i.e. increased PSI acceptor side limitation, induced either by the addition of DCMU (Suorsa et al. 2012) or the pgr1 mutation, which affects the cyt b6f complex, also rescues the pgr5 photosynthetic phenotype (Yamamoto and Shikanai 2019). Furthermore, combined knock-out of multiple proteins of the oxygen-evolving complex of PSII rescues not only the photosynthetic defect of the pgr5 mutation but also viability under FL conditions (Suorsa et al. 2016). A third possibility for restoring CEF in the absence of PGR5 is to increase the activity of NDH-dependent CEF. Thus, it has been previously described that plants with an inactive CHLOROPLAST FRUCTOSE-1,6-BISPHOSPHATASE1 (cFBP1) gene have an overaccumulation of the NDH complex, resulting in hyperactivity of NDH-dependent CEF (Livingston et al. 2010). Furthermore, the pgr5 cfbp1 mutation was described to have less light-saturated LEF compared with cfbp1, while the cfbp1 crr2 double mutant with a defective NDH complex was severely impaired in photosynthesis and growth, leading to the conclusion that the cfbp1 mutation imposes a demand for more ATP production, which was met by increased NDH-dependent CEF that could not be replaced by PGR5-dependent CEF (Livingston et al. 2010). Taken together, these examples demonstrate that there are multiple interactions between PGR5-dependent CEF, NDH-dependent CEF, and other thylakoid electron transport pathways and that the effects of PGR5 depletion can be rescued by restoring PSI donor side limitation.

In this context, the cyt b6f complex occupies a key position between the two PSs (PSII and PSI), taking part in both LEF and CEF. The structure of the dimeric complex has been determined at high resolution from several species (Zhang et al. 2023). However, relatively little is known about its assembly, degradation, and interaction with stromal and thylakoid components involved in CEF. Indeed, a component involved in the assembly of the cyt b6f was recently identified, DE-ETIOLATION-INDUCED PROTEIN1 (DEIP1)/NEW TINY ALBINO1 (NTA1) (Sandoval-Ibanez et al. 2022; Li et al. 2023). The DEIP1/NTA1 protein has been shown to interact with cyt b6f, but with some discrepancies: in one study, it was found to interact with PetA and PetB (Sandoval-Ibanez et al. 2022) and in the other with PetB, PetD, PetG, and PetN (Li et al. 2023). DEIP1/NTA1 is essential for cyt b6f biogenesis, as plants lacking this protein are unable to accumulate the complex and subsequently die (Sandoval-Ibanez et al. 2022; Li et al. 2023). The cyt b6f complex is a site of proton translocation across the thylakoid membrane, contributing to establishing the proton gradient required for ATP synthesis and photoprotection, and is an important component of the aforementioned photosynthetic control. Additionally, cyt b6f is involved in the activation of the so-called state transitions, which balance the excitation energy between PSII and PSI through phosphorylation and relocation of the antenna complex LHCII (reviewed in Malone et al. (2021)). Therefore, it is not surprising that cyt b6f has emerged as a regulatory hub for the coordination of different electron transport pathways and mechanisms for short- and long-term light acclimation (Yamamoto and Shikanai 2019). In fact, the pgr1 mutation, which confers hypersensitivity of the cyt b6f complex to luminal acidification and allows photosynthetic control to operate from neutral pH, partially rescues the pgr5 photosynthetic phenotype (Yamamoto and Shikanai 2019).

With the aim of identifying components involved in FL acclimation, as well as deepening our knowledge of the mechanisms and the interplay between the different photosynthetic electron transport pathways, we performed a pgr5 suppressor screen based on the seedling-lethal phenotype of the Arabidopsis pgr5 mutant under FL. We selected 449 pgr5 suppressor mutants, of which we sequenced 37 and identified 25 mutations affecting 12 different photosynthesis-related proteins, including PFSC1, which controls cyt b6f accumulation at early developmental stages, and 2 mutations affecting the functionality or regulation of cFBP1. We demonstrated that changes in PSI donor and acceptor side limitations at early developmental stages are responsible for the recovery of viability of young pgr5 plants under FL light. Moreover, we found an unexpected interplay between PGR5 and DEIP1/NTA1, revising the concept that DEIP1/NTA1 acts as a canonical assembly factor for the cyt b6f complex, since the complex can assemble when both PGR5 and DEIP1/NTA1 are inactivated.

Results

A pgr5 suppressor screen based on recovery of viability under FL

To identify components involved in light acclimation, we performed a pgr5 suppressor screen under FL conditions. After mutagenizing pgr5 Arabidopsis seeds using EMS, we screened 273,000 plants in the second generation (M2) to saturate the screen and selected 449 survivors under FL in contrast to pgr5, which was seedling lethal after the cotyledon stage in this condition. When we obtained the genome sequences of the first 4 suppressor lines, designated as p5s1, 2, 3, and 4, we found mutations affecting PSII function in all of them, in agreement with the results of Suorsa et al. (2016). Therefore, in order to eliminate most mutations in PSII components, we performed an additional selection step and considered for further analysis only those lines with maximum PSII quantum yield (Fv/Fm) values similar to wild type (WT) (117 lines). Finally, 37 pgr5 suppressor mutants were sequenced and analyzed for causative mutations. In 25 cases, we identified single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) affecting 12 different genes as potential causative mutations of the pgr5 suppressor phenotype (Table 1). Five genes were hit by independent mutations, providing evidence that those mutations were indeed responsible for the suppressor phenotype. We confirmed 6 mutations by identifying or generating additional mutant alleles (T-DNA knockouts or CRISPR/Cas-induced mutations) and introducing them into the pgr5 background to verify the nonlethal phenotype under FL (pgr5 low psii accumulation66 [lpa66] for p5s1 and p5s2, pgr5 mitochondrial transcription termination factor5 [mterf5] for p5s3, pgr5 cfbp1 for p5s18, and p5s19 and pgr5 at2g04360 for p5s22, p5s23, p5s24, and p5s25) or CRISPR/Cas9 (pgr5 acht2 for p5s20 and pgr5 deip1 for p5s21) (Table 1; see Fig. 1A for FL phenotype of representative lines).

Table 1.

Overview of the pgr5 suppressors identified in the screen. The maximum quantum yield of PSII (Fv/Fm), SNPs (nt), corresponding amino acid exchanges (AA), ATG accession number, protein name, and its tentative function together with relevant literature are listed. Genes for which more than 1 independent suppressor mutation was found or whose suppressor phenotype was confirmed by T-DNA or CRISPR/Cas mutant alleles are highlighted in bold

| Suppressor | Fv/Fm | nt | AA | Gene | Protein | (Tentative) function/reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSII | ||||||

| p5s1 | 0.62 | C/T | W/* | AT5G48910 | LPA66 | Editing of psbF (Cai et al. 2009) |

| p5s2 | 0.63 | G/A | A/V | |||

| p5s3 | 0.44 | G/A | G/E | AT4G14605 | mTERF5 | Transcription of psbEFLJ (Ding et al. 2019) |

| p5s4 | 0.62 | G/A | G/D | AT1G06680 | PsbP | Oxygen-evolving enhancer (Yi et al. 2007) |

| p5s5 | 0.71 | G/A | C/Y | |||

| p5s6/7 | 0.74 | C/T | A/V | AT5G01530 | Lhcb4.1 | Chlorophyll a to b binding protein (CP29) (de Bianchi et al. 2011) |

| p5s8/9 | 0.79 | G/A | Q/* | AT3G55330 | PPL1 | PsbP-like protein 1, repair of photodamaged PSII (Ishihara et al. 2007) |

| p5s10 | 0.79 | C/T | W/* | |||

| p5s11 | 0.81 | G/A | P/S | |||

| p5s12 | 0.80 | G/A | Q/* | |||

| p5s13 | 0.79 | G/A | G/E | AT1G71500 | Psb33 | PSII stabilization (Fristedt et al. 2015) |

| Cyt b6f | ||||||

| p5s14 | 0.73 | G/A | M/I | AT5G54290 | CcdA | Cyt b6f biogenesis/transfer of reducing equivalents from stroma to thylakoid lumen (Page et al. 2004) |

| PC | ||||||

| p5s15/16 | 0.77 | G/A | G/R | AT4G33520 | PAA1 | Copper-transporting ATPase (Shikanai et al. 2003) |

| p5s17 | 0.80 | G/A | C/Y | |||

| Chloroplast FBPase | ||||||

| p5s18/19 | 0.79 | C/T | S/L | AT3G54050 | cFBP1 | Chloroplast Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (Rojas-Gonzalez et al. 2015) |

| p5s20 | 0.80 | G/A | R/* | AT4G29670 | ACHT2 | Atypical Cys His-rich Trx, oxidative regulation (Yokochi et al. 2021) |

| Functions assigned in this study | ||||||

| p5s21 | 0.78 | C/T | G/D | AT2G27290 | DEIP1/NTA1 | Cyt b6f assembly (Sandoval-Ibanez et al. 2022; Li et al. 2023). Protection of cyt b6f against PGR5 effects (this study) |

| p5s22 | 0.69 | G/A | W/* | AT2G04360 | PFSC1 | Cyt b6f accumulation (this study) |

| p5s23/24 | 0.79 | C/T | Q/* | |||

| p5s25 | 0.83 | C/T | R/* | |||

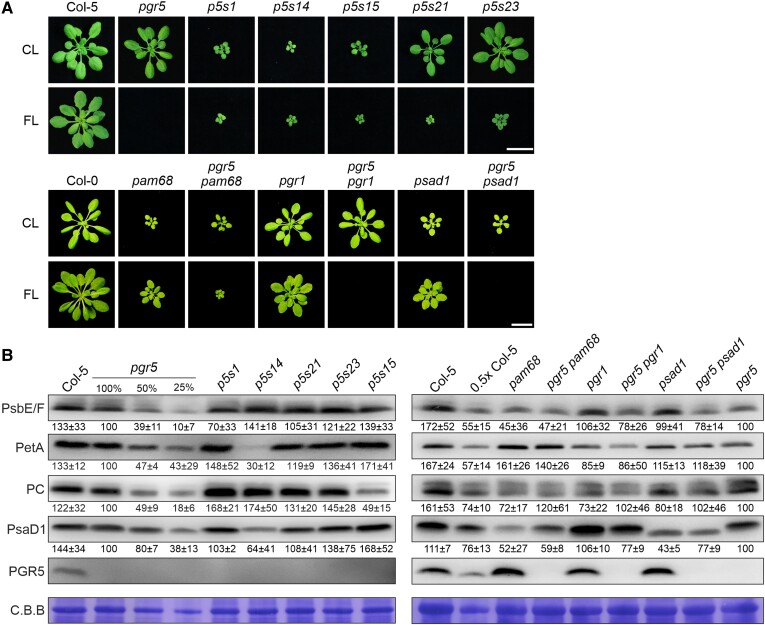

Figure 1.

Impact of perturbed LEF on the suppression of pgr5 phenotypes. A) Growth phenotype of suppressor lines (p5s1, p5s14, p5s15, p5s21, and p5s23) and representative mutations affecting PSII (pam68), cyt b6f (pgr1), and PSI (psad1) in either WT or pgr5 background, compared with pgr5 and WT (Col-0 and Col-5) under CL (after 3 wks) and FL (after 5 wks). Scale bars indicate 1 cm. B) Immunoblot analysis of representative photosynthetic proteins. Aliquots of total leaf protein from the CL-grown plants shown in A) were fractionated by SDS–PAGE under reducing conditions, transferred onto PVDF membranes, and immunodecorated with specific antibodies. Staining of the membranes with C.B.B. served as loading control. Representative blots from 3 experiments are presented, as well as the average of the band quantifications (n = 3) relative to pgr5 (100%) ± Sd.

Perturbation of LEF at PSII and the cyt b6f complex, but not PSI, can rescue pgr5 lethality

Interestingly, all the SNPs identified in the screen affected genes encoding proteins involved in photosynthesis (Table 1). Six genes are required for proper PSII function, such as LPA66 (mutated in p5s1 and p5s2), which codes for a psbF editing factor and is therefore required for PSII assembly (Cai et al. 2009). Another gene, CYTOCHROME C DEFECTIVEA (CCDA, mutated in p5s14, is necessary for the biogenesis of cyt b6f (Page et al. 2004). The two suppressor lines p5s15 and p5s17 carry mutations in the gene for the copper transporter P-type ATPase of Arabidopsis1 (PAA1), which is required for the accumulation of functional PC (Shikanai et al. 2003). Under control light (CL; 12 h light with 100 µmol photons m−2 s−1/12 h darkness; see Materials and methods), p5s1, 14, and 15 showed markedly reduced growth compared with pgr5 and WT, and they survived under FL in contrast to pgr5 (Fig. 1A).

In order to clarify the effects of these representative mutations on the levels of the corresponding photosynthetic multiprotein complexes (p5s1 and p5s14) and PC (p5s15), immunoblot analyses were performed. Indeed, compared with pgr5 plants, p5s1, p5s14, and p5s15 showed only 70% of PsbE/F, 30% of PetA, and 49% of PC levels, respectively (Fig. 1B). This result supports the previous finding of Suorsa et al. (2016) that defects in PSII can suppress pgr5 lethality under FL conditions. Therefore, pgr5 lethality suppressors include defects in the cyt b6f complex and PC accumulation, prompting the idea that an increase in PSI donor side limitation may be the common mechanism behind this.

In addition, we identified an SNP in a gene encoding a protein recently described to be involved in the assembly of the cyt b6f complex and essential for photoautotrophic growth, DEIP1/NTA1 (Sandoval-Ibanez et al. 2022; Li et al. 2023). Interestingly, the corresponding suppressor line p5s21 carrying a mutation in DEIP1/NTA1 was able to grow similarly to the WT under CL conditions (Fig. 1A) and had WT-like PetA levels (Fig. 1B). This finding is surprising and deserves special attention because the deipt1/nta1 mutation alone causes lethality at the seedling stage (Sandoval-Ibanez et al. 2022; Li et al. 2023).

Furthermore, three independent suppressor lines were found (p5s22, p5s23/24, and p5s25) which carry mutations in the AT2G04360 gene encoding an unknown protein. Analysis of p5s23 showed that under CL conditions, the mutant grew like the WT and had similar or even higher levels of all thylakoid proteins tested (Fig. 1, A and B). We provide a detailed characterization of the p5s21 and p5s23 lines and their effects on the DEIP1/NTA1 and At2g04360 proteins later in the manuscript.

Our suppressor screen failed to identify mutations in PSI-related genes or in PETC/PGR1, which may be due to our Fv/Fm preselection, an insufficient number of sequenced lines, or the possibility that defects in PSI and PGR1 cannot suppress pgr5 lethality. To clarify this, we generated a series of double mutants in the pgr5 background. As expected from the results of the screen and previous findings (Suorsa et al. 2016), mutation of the PSII assembly factor PAM68 (Armbruster et al. 2010) suppressed the pgr5 phenotype under FL (Fig. 1A). However, mutation of PSAD1, which affects accumulation of the d subunit of PSI (Ihnatowicz et al. 2004), failed to suppress pgr5. This finding is consistent with our negative results for PSI-related genes from the suppressor screen. However, it is possible that PSI-related mutations were not detected, because the screen was not saturated, or because of the Fv/Fm preselection, or because additional PSI mutations could amplify the PSI damage under FL conditions in the pgr5 background. Interestingly, pgr5 pgr1, which lacks PGR5 and contains a mutant Rieske protein in cyt b6f that does not alter protein composition but reduces cyt b6f activity under high light (HL) (Munekage et al. 2001) (Fig. 1B), did not suppress pgr5 lethality under FL (Fig. 1A). This implies that under our FL conditions and in young soil-grown plants, the increased photosynthetic control associated with increased PSI donor side limitation due to the pgr1 mutation observed in leaf disc assays (Yamamoto and Shikanai 2019) is not sufficient to rescue photoautotrophic growth.

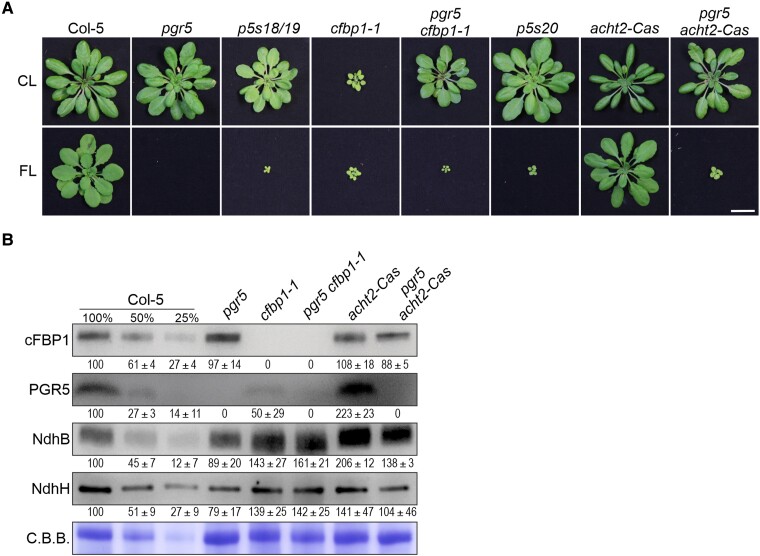

Mutual compensation of defects caused by pgr5 and mutations affecting cFBP1 activity

The two suppressor lines p5s18/19 and p5s20 carry mutations in the CFBP1 gene, which encodes cFBP1, and the ACHT2 gene, respectively. The ACHT2 protein is involved in cFBP1 oxidation; simultaneous inactivation of ACHT1 and ACHT2 can suppress ntrc phenotypes; and ACHT2 overexpression results in higher NPQ, stunted growth, lower chlorophyll, and lower Fv/Fm (Yokochi et al. 2021). Under CL conditions, the two suppressor lines grew like WT, and they survived under FL in contrast to pgr5 (Fig. 2A). To confirm that the suppression of the pgr5 mutation was indeed caused by these mutations, we identified loss-of-function alleles of CFPB1 and ACHT2 and introduced them into the pgr5 background. We generated a double mutant line (pgr5 cfbp1-1) by crossing pgr5 with a T-DNA insertion line lacking detectable expression of cFBP1 (cfbp1-1) (Fig. 2B). The growth of cfbp1-1 under CL conditions was severely impaired, as previously reported (Livingston et al. 2010; Rojas-Gonzalez et al. 2015). However, growth was restored to WT levels in the pgr5 cfbp1-1 and p5s18/19 lines, an observation that went unnoticed by Livingston et al. (2010), who also generated such double mutants. Since cfbp1-1 plants were named HCEF1 for “high CEF1” due to their substantially and constitutively increased NDH-dependent CEF (Livingston et al. 2010), we confirmed the increase in NDH subunits in cfbp1-1 and pgr5 cfbp1-1 plants, albeit to a much lower extent (between around 140% and 160% of WT levels of NdhB and NdhH; Fig. 2B) than the 15-times increase reported by Livingston et al. (2010). The discrepancy in NDH accumulation results and the restored growth of pgr5 cfbp1-1 plants, which was undetected in the study by Livingston et al. (2010), is unlikely to be due to different growth conditions. Indeed, the growth conditions used in Livingston et al. (2010) and our study were very similar. Genetic differences between the mutant lines used could be a possible explanation. For example, second-site mutations in hcef1 due to its origin by EMS mutagenesis could have altered the phenotype of the mutant.

Figure 2.

Effect of loss or altered regulation of cFBP1 on the suppression of pgr5 phenotypes. A) Growth phenotype of WT (Col-5), single (pgr5, cfbp1-1, and acht2-Cas), and double mutant (pgr5 cfbp1-1 and pgr5 acht2-Cas) plants under CL (5 wks) and FL (5 wks) conditions. Scale bar indicates 1 cm. B) Aliquots of total leaf proteins were isolated from the CL-grown plants in A), fractionated by SDS–PAGE under reducing conditions, transferred onto PVDF membranes, and immunodecorated with antibodies specific for cFBP1, PGR5, NdhB, and NdhH. Staining of the membranes with C.B.B. served as loading control. Representative blots from 3 experiments are presented, as well as the average of the band quantifications (n = 3) relative to WT (100%) ± Sd.

Our finding that depletion of PGR5 in this background of constitutive and enhanced NDH accumulation restores normal growth provides insight into the original findings of Livingston et al. (2010). In both Livingston et al. (2010) and in this study (Fig. 2B), a reduction of PGR5 levels by about 50% was observed in the cfbp1-1/hcef1 line. This suggests that PGR5 activity may be harmful in the absence of cFBP1, leading to a decrease in PGR5 expression. The total absence of PGR5 restores normal growth (Fig. 2A), reinforcing the idea that PGR5 activity is unproductive in the absence of cFBP1. One possible explanation for this is that if PGR5 can negatively regulate ATP synthase activity, as previously suggested (Avenson et al. 2005), its absence combined with the proposed increase in NDH-dependent CEF activity (Livingston et al. 2010) could have a complementary effect on ATP synthesis. However, our study only demonstrated a moderate increase in NDH levels (Fig. 2B). Moreover, the experimental basis of the hypothesis that PGR5 regulates ATP synthase activity has been questioned (Yamamoto and Shikanai 2020), and there is no biochemical evidence that PGR5 interacts with the ATP synthase. Therefore, in the Discussion section, we will revisit the potential causes for the increase in NDH levels and the decrease in PGR5 levels in the absence of cFBP1/HCEF1.

Moreover, using the CRISPR/CAS system, we generated two knock-out lines for ACHT2: one in the Col-0 background (acht2-Cas) and the other in pgr5 (pgr5 acht2-Cas) (Supplementary Fig. S1A). Notably, and similar to the case of the cFBP1 mutant described above, pgr5 acht2-Cas displayed the same FL phenotype as p5s20 (Fig. 2A).

In conclusion, inactivation of cFBP1 or of its negative regulator can restore the viability of pgr5 plants under FL conditions. In the case of pgr5 cfbp1-1, the pgr5 mutation suppresses the growth defect of the cfbp1 lines, suggesting that the balance of PGR5 and NDH activity may be critical for plant development.

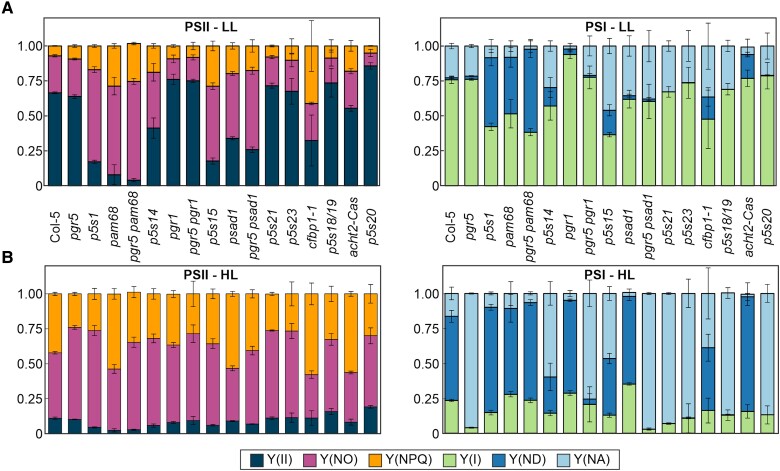

Relationship between pgr5 suppression and changes in PSI donor or acceptor side limitation

To analyze photosynthetic performance, we measured chlorophyll fluorescence of adult plants under conditions mimicking the FL of the screen (for a time-resolved example of values obtained for WT and pgr5, see Supplementary Fig. S2). This analysis showed that during the LL phase, the three double mutants p5s1, 14, and 15 had lower photosynthetic electron transport rates from PSII (Y(II)) and PSI (Y(I)) and an increased deficit of electron donors to PSI (Y(ND)), together with an increase in NPQ, compared with pgr5 plants (Fig. 3A). In contrast, during the HL phase, p5s1, 14, and 15 showed slightly lower Y(II) but slightly higher Y(I) values, while Y (ND) was massively increased at the expense of a much less limited PSI acceptor side (Y(NA)) compared with pgr5 (Fig. 3B). This suggests that the impaired electron flow due to impaired PSII (p5s1), cyt b6f (p5s14), or PC (p5s15) is indeed responsible for suppressing the lethality of the pgr5 mutation. Indeed, the pam68 mutation in the pgr5 background mimics the behavior observed in p5s1, whereas neither the psad1 nor the pgr1 mutation can markedly reduce the PSI acceptor side limitation of pgr5 during the HL phase, providing an explanation for their inability to suppress the FL lethality of pgr5.

Figure 3.

Relationship between pgr5 suppression and changes in photosynthetic electron flow. A) and B) The same genotypes as in Fig. 1 were grown under CL for 5 wks and then subjected to a FL program using the DUAL-PAM chlorophyll fluorometer, applying cycles of 5 min low (50 µmol photons m−2 s−1) and 1 min high (500 µmol photons m−2 s−1) actinic light. The values corresponding to PSII (left) and PSI (right) parameters during an LL (A) and HL phase (B) are average values of at least 3 replicates ± Sd. Y(II), PSII quantum yield; Y(NO), nonregulated energy dissipation, Y(NPQ), nonphotochemical quenching; Y(I), PSI quantum yield; Y(ND), PSI donor side limitation; Y(NA), PSI acceptor side limitation.

Indeed, the ability of mutations to decrease under HL the PSI acceptor side limitation while increasing the donor side limitation is a feature of the pgr5 suppressor lines that are affected in LEF between PSII and PSI. However, neither the two suppressor lines with mutations associated with cFBP1 (p5s18/19 and p5s20) nor the two lines with mutations in DEIP1/NTA1 (p5s21) or At2g04360 (p5s23) differ substantially from pgr5 with respect to their Y(ND) and Y(NA) values. As the photosynthesis measurements could only be performed on adult plants for technical reasons, since only mature leaves can be measured for this set of parameters, a plausible explanation is that these parameters are indeed altered in younger plants, where they are crucial for survival under FL. In fact, the in-depth analysis of two suppressor lines with mutations in DEIP1/NTA1 (p5s21) or At2g04360 (p5s23) described below confirms this hypothesis.

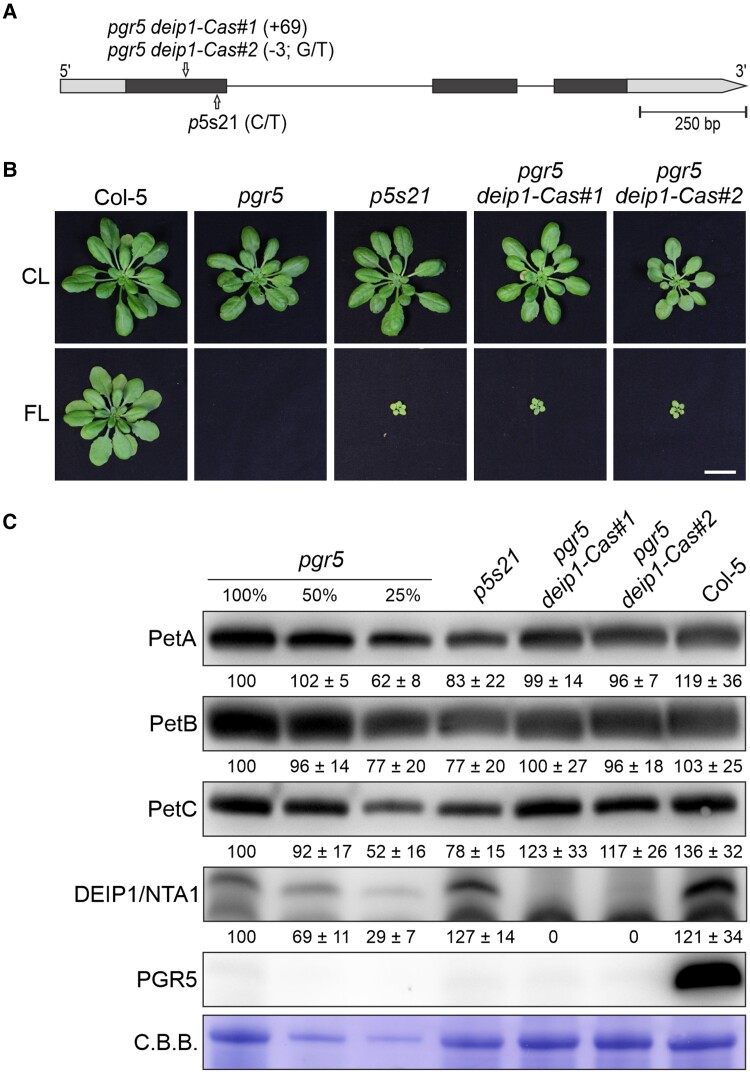

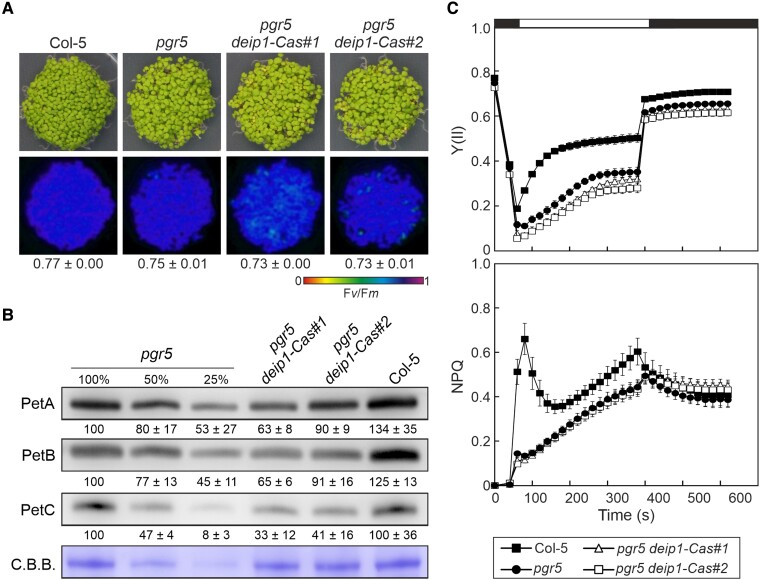

Control of cyt b6f accumulation by DEIP1/NTA1 depends on PGR5 and is developmentally regulated

The pgr5 suppressor line p5s21 contained a C/T mutation that resulted in an amino acid exchange (G72D) in the soluble N-terminus of the DEIP1/NTA1 protein (Fig. 4A and Supplementary Fig. S1B). To prove that this mutation was responsible for the recovery of pgr5 viability under FL (Fig. 1A), we generated two independent pgr5 deip1/nta1 mutants using CRISPR/Cas technology: pgr5 deip1-Cas#1 and #2 (Fig. 4A and Supplementary Fig. S1B). It is worth noting that the same mutations could not be obtained in the WT background, which is consistent with previous findings reporting that the single mutant deip1/nta1 is seedling lethal, because the plant does not accumulate cyt b6f (Sandoval-Ibanez et al. 2022; Li et al. 2023). Importantly, the two generated pgr5 deip1-Cas lines behaved similar to p5s21 and were able to grow under FL (Fig. 4, B and C). In both CRISPR/Cas lines, the DEIP1/NTA1 protein and PGR5 were missing (Fig. 4C), whereas in p5s21, amounts of DEIP1/NTA1 similar to WT were detectable. This suggests that the amino acid exchange G72D may (partially) inactivate or destabilize DEIP1/NTA1 without abolishing the accumulation of the protein. Interestingly, in the two pgr5 deip1-Cas double mutants, the levels of cyt b6f proteins (PetA, PetB, PetC) were similar to those in pgr5 and WT plants (Fig. 4C), in contrast to single deip1/nta1 mutants that lack cyt b6f (Sandoval-Ibanez et al. 2022; Li et al. 2023). These results suggest that PGR5 plays a relevant role in the mode of action of DEIP1/NTA1 and in the stability of cyt b6f. However, they do not explain the survival of the pgr5 deip1/nta1 plants under FL.

Figure 4.

Growth and cyt b6f protein accumulation in adult plants lacking both DEIP1/NTA1 and PGR5. A) Schematic representation of the Arabidopsis DEIP1/NTA1 coding sequence. The positions of the nucleotide insertions in the pgr5 deip1-Cas#1 and #2 mutants are shown, as well as the nucleotide substitution C/T in p5s21. The 5'- and 3'-UTR regions are shown as gray boxes, the exons in black, and the intron as a line. B) Growth phenotype of WT (Col-5), pgr5, and pgr5 deip1/nta1 (p5s21, pgr5 deip1-Cas#1, and pgr5 deip1-Cas#2) plants under CL (5 wks) and FL (5 wks). Note that the deip1/nta1 single mutant could not be obtained due to its lethality. Scale bar indicates 1 cm. C) Aliquots of total leaf proteins were isolated from the CL-grown plants in B), fractionated by SDS–PAGE under reducing conditions, transferred onto PVDF membranes, and immunodecorated with cyt b6f- (PetA, PetB, PetC), NTA1-, or PGR5-specific antibodies. C.B.B. staining of the membranes served as a loading control. Representative blots from 3 experiments are presented, as well as the average of the band quantifications (n = 3) relative to pgr5 (100%) ± Sd.

Interestingly, we observed that at the seedling stage (4-d-old plants; Fig. 5A), the levels of cyt b6f in pgr5 deip1-Cas#1 and #2 were not recovered to the WT as in adult plants and remained lower than in pgr5, especially PetC, which was between 33% and 41% of pgr5 (Fig. 5B). Thus, the differences observed at the protein level resulted in slightly lower PSII activity in the double mutants compared with pgr5, without changes in NPQ (Fig. 5C), which would explain the suppressor effect under FL due to increased PSI donor side limitation.

Figure 5.

Cyt b6f protein accumulation and photosynthesis in seedlings lacking both DEIP1/NTA1 and PGR5. A) Four-day-old WT (Col-5), single (pgr5), and double (pgr5 deip1-Cas#1 and pgr5 deip1-Cas#2) mutant plants were grown on MS plates under LD conditions. Below, false-color images show the Fv/Fm values for each plantlet line, according to the color scale at the bottom of the panel. For each line, the average of the values (n = 3) ± Sd is shown. B) Aliquots of total leaf proteins (adjusted to equal fresh weight) were isolated from the seedlings in A), fractionated by SDS–PAGE under reducing conditions, transferred onto PVDF membranes, and immunodecorated with PetA-, PetB- or PetC-specific antibodies. Staining of the membranes with C.B.B. served as loading control. Representative blots from 3 experiments are presented, as well as the average of the band quantifications (n = 3) relative to pgr5 (100%) ± Sd. C) PSII quantum yield (Y(II)) and NPQ of dark-adapted seedlings in A) during an induction–recovery curve (indicated by the white and black bars above) using the HEXAGON-IMAGING-PAM fluorimeter and applying 100 μmol photons m−2 s−1 of actinic light. Averages of at least 3 replicates ± Sd are shown.

Taken together, it appears that DEIP1/NTA1 does not function as a simple assembly factor of the cyt b6f complex, since its absence can be fully compensated, at least in adult plants, and partially in very young plants, in the absence of PGR5. This suggests that one or more of the pleiotropic effects of the pgr5 mutation on photosynthesis and thylakoid redox state render the function of DEIP1/NTA1 obsolete.

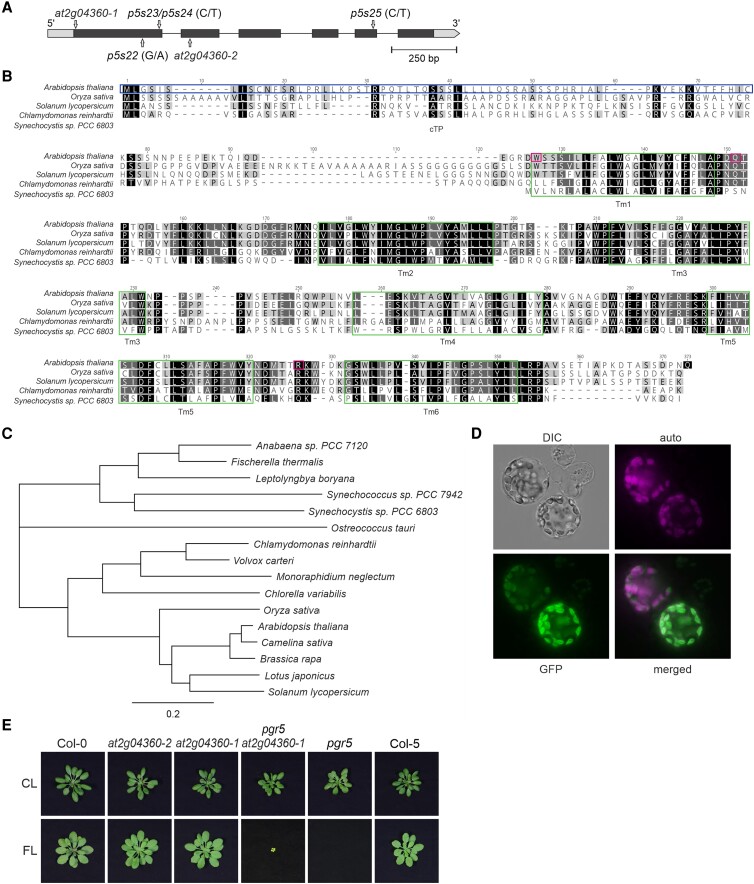

At2g04360 encodes a chloroplast protein conserved in photosynthetic organisms

We found three suppressor lines, p5s22, p5s23/24, and p5s25, with mutations in the AT2G04360 gene (Table 1, Figs. 1 and 6A). In silico analysis showed that the protein encoded by At2g04360 contains 6 transmembrane domains (Fig. 6B) and is highly conserved in all photosynthetic organisms, including algae and cyanobacteria (Fig. 6, B and C). However, the function of this protein in these organisms is unclear. Moreover, the encoded protein has a predicted chloroplast transit peptide (cTP), with the mature protein most likely starting at amino acid 66 according to TargetP 2.0 (Fig. 6B). Indeed, the protein encoded by At2g04360 was identified in the stromal lamellae of thylakoids in a previous proteomic analysis (Tomizioli et al. 2014). We experimentally confirmed the chloroplast location of the protein encoded by At2g04360 by transient expression of an At2g04360-GFP fusion in isolated Arabidopsis protoplasts (Fig. 6D).

Figure 6.

At2g04360 is a conserved chloroplast protein. A) The AT2G04360 gene: structure and T-DNA insertions in mutant lines. The position of the T-DNA in the at2g04360-1 (from the GK collection) and at2g04360-2 (from the Salk collection) is shown, as well as the nucleotide substitutions in p5s22, p5s23/24, and p5s25. The 5'- and 3'-UTR regions are shown as gray boxes, the exons are shown in black, and the intron is shown as a line. B) Multiple sequence alignment of At2g04360 proteins from different photosynthetic organisms. Instances of sequence identity/similarity in at least 40% of the sequences are highlighted by black/gray shading. The six (green) rectangles indicate the transmembrane domains (Tm) of Arabidopsis At2g04360 (Q29Q44). In the Arabidopsis sequence, the first (blue) rectangle indicates the predicted cTP. The lines p5s22, 23/24, and 25 contain mutations leading to stop codons at the positions 88, 112, and 274 of Arabidopsis At2g04360, respectively. C) Phylogenetic tree using mature At2g04360 protein sequences (without cTPs) from different organisms, including plants, algae, and cyanobacteria. D) Subcellular location of At2g04360 determined by transient expression of At2g04360-GFP in Arabidopsis protoplasts. E) Growth phenotype of WT (Col-0 and Col-5) and mutant (at2g04360-2, at2g04360-1, pgr5, and pgr5 at2g04360-1) plants under CL (5 wks) and FL (5 wks) conditions. Scale bar indicates 1 cm.

To study the function of At2g04360, we identified two independent Arabidopsis T-DNA mutants with insertions at the beginning of the gene (at2g04360-1) and in the second exon (at2g04360-2) (Fig. 6A). Determination of mRNA expression by RT-qPCR using primers that amplify a part of the first and second exon regions of the AT2G04360 gene resulted in very low (at2g0360-1) or no (at2g04360-2) signals for the mutants (Supplementary Fig. S3). The two mutant lines grew similarly to WT under control and FL conditions (Fig. 6E). However, it is worth noting that in both conditions and for both genotypes, we also found plants that were much smaller than WT. In addition, to prove that the mutation of AT2G04360 really suppresses the lethal pgr5 phenotype under FL, we generated the double mutant pgr5 at2g04360-1 by crossing the 2 single mutants. Indeed, the double mutant was able to survive under FL conditions (Fig. 6E), even up the flowering stage.

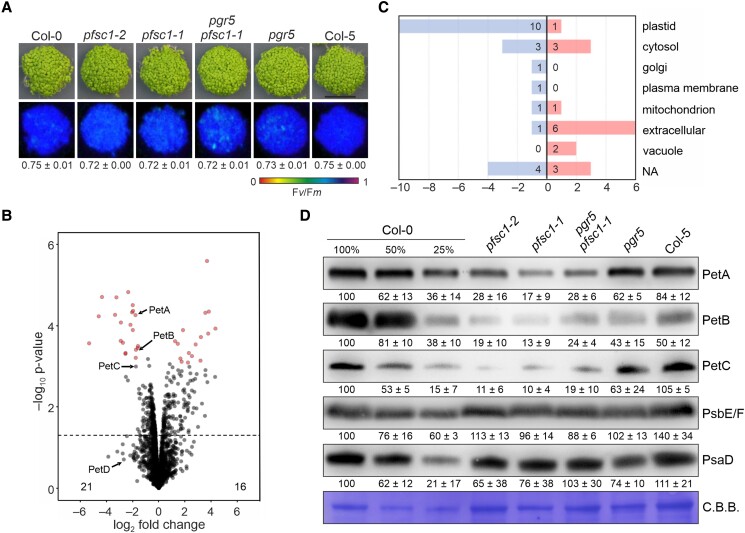

At2g04360/PFSC1 is required at early developmental stages for cyt b6f accumulation and HL tolerance

To investigate the function of At2g04360, we switched our attention to seedlings to avoid the aforementioned heterogeneity observed in the growth of adult plants lacking At2g04360. At this development stage, no differences in growth or Fv/Fm were observed between the different lines (Fig. 7A). We then performed a proteomic analysis using pools of 4-d-old seedlings grown on MS plates (Fig. 7B). Thirty-seven differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) were found in at2g04360-1 compared with Col-0, considering those with at least 2-fold change (FC) and <0.05 adjusted P-value (Fig. 7B, Supplementary Table S1 and Data Set 1). Of these, 16 were upregulated and 21 were downregulated, most of which were located in plastids (Fig. 7C). Interestingly, the levels of two cyt b6f subunits, PetA and PetB, were significantly altered in at2g04360-1, being about 30% of the WT level. The same level was observed for PetC, although the change was not statistically significant. The changes in cyt b6f accumulation were specific regarding photosynthesis, as no changes in other photosynthetic proteins were found (Supplementary Table S1). The results of the proteomics analysis were corroborated by immunoblot analysis, which also included the at2g04360-2 and pgr5 at2g04360-1 lines (Fig. 7D). All three pfsc1 lines showed reduced levels of PetA, PetB, and PetC, while PsbE/F and PsaD1 levels remained similar to those in the WT (Fig. 7D). These results suggest that At2g04360 is required for the accumulation of cyt b6f, particularly in early developmental stages, but unlike DEIP1/NTA1, independent of PGR5, since lower levels of this complex were also found in pgr5 at2g04360-1. Because of the altered cyt b6f levels, we named the mutation “pgr5 suppressor with altered cyt b6f 1” or pfsc1, whereby the “f” stands for “5”, and the AT2G04360 gene PFSC1.

Figure 7.

Maximum PSII quantum yield and cyt b6f accumulation in seedlings lacking At2g04360/PFSC1. A) Four-day-old WT (Col-0 and Col-5), single (pgr5, at2g04360-1/pfsc1-1, and -2), and double (pgr5 at2g04360-1/pfsc1-1) mutant plants were grown on MS plates under LD conditions. Below, false-color images show the Fv/Fm values for each plantlet line, according to the color scale at the bottom of the panel. For each line, the average of the values (n = 3) ± Sd is shown. B) Volcano plot of DEPs (at2g04360-1/pfsc1-1 vs. Col-0) as in A). Each point indicates a different protein, ranked according to P-value (y axis, −log10 of P-values) and relative abundance ratio (x axis, log2 FC pfsc1-1 Col-0). DEPs (log2 FC > |1|, FDR < 0.05) are labeled in red. The dashed line indicates a negative log10P-value of 1.3. C) Subcellular distribution of the DEPs shown in B). Subcellular location was determined using the SUBA4 database. NA, not assigned. D) Aliquots of total leaf proteins (adjusted to equal fresh weight) were isolated from seedlings as shown in A), fractionated by SDS–PAGE under reducing conditions, transferred onto PVDF membranes, and immunodecorated with PetA-, PetB-, PetC-, PsbE/F-, and PsaD-specific antibodies. Staining of the membranes with C.B.B. served as loading control. Representative blots from 3 experiments are presented, as well as the average of the band quantifications (n = 3) relative to Col-0 (100%) ± Sd.

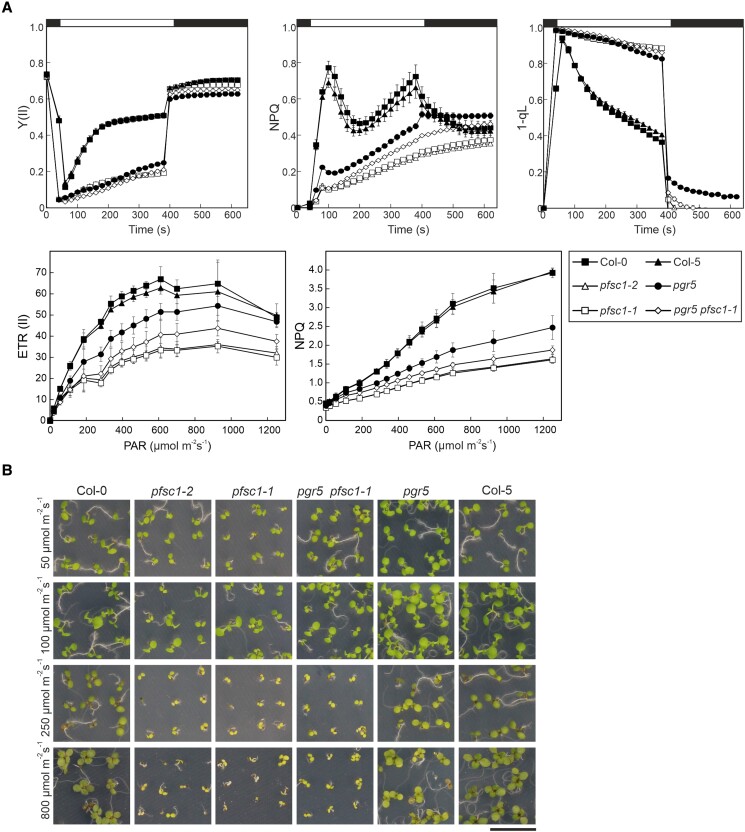

The analysis of the photosynthetic performance (Fig. 8A) showed that seedlings lacking PFSC1 had very low electron transport rates from PSII (ETR(II)), despite Fv/Fm values higher than 0.7 (Fig. 7A). Furthermore, they were unable to induce transient NPQ, which was even lower than in pgr5 and showed a strongly reduced PQ pool during illumination (1 qL close to 1). These results are consistent with the defective cyt b6f accumulation observed in the absence of PFSC1, as these plants will have a bottleneck of electrons on PQs, as well as impaired acidification of the lumen. Additionally, the lower electron transport in pgr5 pfsc1-1 compared with pgr5 at the seedling stage (Fig. 8A) may explain the survival phenotype of these plants under FL conditions.

Figure 8.

PFSC1 is required for proper photosynthesis and HL tolerance in seedlings. A) Measurement of photosynthetic parameters. PSII quantum yield (Y(II)), NPQ, and the redox state of the PQ pool (1 qL) (upper 3 panels) were determined in 4-d-old WT (Col-0 and Col-5), single (pgr5, pfsc1-1, and −2), and double (pgr5 pfsc1-1) mutant plants grown on MS plates under LD conditions, during an induction–recovery curve (indicated by the white and black bars above) using the HEXAGON-IMAGING-PAM fluorimeter and applying 100 μmol photons m−2 s−1 of actinic light. Plants were previously dark-adapted for 30 min. Electron transport rates from PSII (ETR(II)) and NPQ (lower 2 panels) were measured at increasing photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) using the IMAGING-PAM fluorimeter. Averages of at least 3 replicates ± Sd are shown. B) Growth phenotype of the same genotypes as in A) grown on MS plates under LD conditions and different light intensities for 7 d. Scale bar indicates 1 cm.

Correspondingly, young plants lacking PFSC1 were very sensitive to HL (Fig. 8B). The mutants died after the cotyledon stage at 800 and even at 250 µmol photons m−2 s−1. In contrast, at lower light intensities (50 to 100 µmol photons m−2 s−1), these plants were able to grow like the WT (Fig. 8B). Autoshading and its absence is therefore the most likely explanation for the aforementioned observation that among pfsc1 plants, a certain proportion of plants were found that were much smaller than WT.

Discussion

In our screen, we selected 449 survivors under FL conditions from a pool of 273,000 screened plants. We then preselected 117 lines based on their WT-like Fv/Fm values. Among the 37 suppressors that we sequenced, we identified SNPs in 25 of them, leading to the identification of 12 genes whose mutated form could suppress the lethality of the pgr5 mutation under FL conditions. This set of 12 genes represents only a fraction of the genes that can suppress pgr5 and is highly enriched for mutations with little negative impact on PSII. This portfolio of mutations allows us to confirm previous models, based on photosynthesis measurements, of how the harmful effects of the pgr5 mutation on PSI can be compensated (Yamamoto and Shikanai 2019). The screen uncovers facets of the interplay between PGR5- and NDH-dependent CEF pathway. Finally, the screen also identifies proteins with functions in the accumulation or protection of cyt b6f.

Suppressors of pgr5 are affected in photosynthesis-related proteins

As the first 4 mutations identified in the suppressor screen all affected PSII and caused markedly decreased Fv/Fm, we subsequently selected suppressor mutants with little or no effect on Fv/Fm to uncover the effect of other chloroplast functions beyond PSII on PGR5-dependent CEF. Nevertheless, we found mutations in proteins associated with PSII (PPL1 and Psb33; see Table 1) that do not affect Fv/Fm, and it is likely that these mutations cause perturbations in the LEF at early developmental stages. Other pgr5 suppressor mutations were found to affect proteins already known to be involved in cyt b6f assembly (CcdA) (Page et al. 2004), copper transport relevant to PC accumulation (PAA1) (Shikanai et al. 2003), and cFBP1 (Rojas-Gonzalez et al. 2015) and one of its regulators (ACHT2) (Yokochi et al. 2021). The remaining two proteins targeted by suppressor mutations have functions associated with cyt b6f. PFSC1, with previously unclear functions, controls cyt b6f accumulation at early developmental stages. DEIP1/NTA1, previously identified as a cyt b6f assembly factor (Sandoval-Ibanez et al. 2022; Li et al. 2023), functionally interacts with PGR5 in a completely unexpected manner, suggesting a link between PGR5 function and cyt b6f accumulation. As a consequence, the screen uncovered mutations exclusively in photosynthetic components, suggesting that there are probably no additional mechanisms other than photosynthetic regulation that can compensate for the absence of PGR5.

Equally interesting is the question of why some mutations were not found in the screen, such as PSI subunits, the pgr1 mutation already described to antagonize the effects of pgr5 (Yamamoto and Shikanai 2019), and mutations that cause high NPQ to compensate for the defect in transient NPQ induction of the pgr5 mutant. We addressed this question by introducing a mutation of PSAD1, which affects the accumulation of the d subunit of PSI (Ihnatowicz et al. 2004), and the pgr1 mutation into the pgr5 background. Both mutations could not restore viability under FL in the pgr5 psad1 and pgr5 pgr1 double mutants, although both mutations also caused a strong increase in PSI donor side limitation under HL in adult plants, as did the pam68 mutation, which could rescue FL lethality. However, the corresponding double mutants did not display the same increased PSI donor side limitations as psad1 and pgr1 did, although pgr5 pgr1 showed a moderate increase in PSII donor side limitation, but not to the same extent as, for example, p5s1, 14, and 15 and pgr5 pam68 (see Fig. 3). Therefore, there may be a threshold level of PSII donor side limitation that needs to be reached to achieve viability under FL. Furthermore, even though we did not identify any PSI mutation in our suppressor screen and the PSAD1 mutation failed to suppress pgr5, we cannot exclude that mutation of other PSI components could suppress pgr5.

As transient NPQ induction is reduced in pgr5, one might also expect to identify mutations that restore NPQ in the screen, given the protective role of NPQ in preventing ROS formation and photoinhibition. However, we have previously shown that this is not the case by introducing two high NPQ mutations into the pgr5 background (Naranjo et al. 2021). Neither the cgl160 mutation, which is defective in the thylakoid ATP synthase and therefore has a lower rate of proton consumption, nor the inactivation of NTRC could rescue the lethal phenotype of pgr5, although the cgl160 mutation could at least partially restore the transient NPQ induction (Naranjo et al. 2021).

Mechanisms of pgr5 suppression

Previous studies have described that the addition of DCMU, which inhibits PSII (Suorsa et al. 2012), or the mutants Δ5 pgr5 (Suorsa et al. 2016) and pgr1 pgr5 (Yamamoto and Shikanai 2019) protects PSI and restores photosynthetic parameters in the pgr5 background. Furthermore, the lack of PGR5 can also be compensated by increasing the electron sink capacity from PSI, for example, by adding methyl viologen, which directly accepts electrons from PSI (Munekage et al. 2002), or by overexpressing P. patens flavodiiron protein genes in pgr5 (Yamamoto and Shikanai 2019). Our analysis of the photosynthetic electron flow of the suppressor lines indicated that this concept easily explains the recovery of suppressor lines under FL, namely a decrease in electron flow to PSI and/or an increase from PSI to its acceptors. Since our screen was based on the recovery of lethality of pgr5 seedlings, the effect of the second-site mutations on PSI donor and acceptor side limitation must occur at early stages of plant development. Nevertheless, we were able to observe these effects on the PSI donor and acceptor sides in adult plants with impaired PSII (p5s1 and pgr5 pam68), cyt b6f (p5s14), or PC (p5s15) (see Fig. 3). In the 4 lines with mutations associated with cFBP1 (p5s18/19 and p5s20), DEIP1/NTA1 (p5s21), or At2g04360 (p5s23), however, the effects were no longer detectable in adult plants. However, when we examined early developmental stages of suppressor lines carrying mutations in DEIP1/NTA1 (p5s21) (see Fig. 5) or PFSC1 (p5s23) (see Fig. 8), we could confirm that they were indeed altered in their photosynthetic electron flow to PSI.

Two suppressor lines were found with mutations that would be expected to affect cFBP1 in opposite directions: line p5s18/19 with a mutated CFBP1 gene and line p5s20 defective in ACHT2, a thioredoxin-like protein that downregulates the Calvin–Benson cycle by oxidative inactivation of the cFBP1 (Yokochi et al. 2021). Livingston et al. (2010) previously reported that plants with an inactive CFBP1 gene exhibit an overaccumulation of the NDH complex, leading to hyperactivity of NDH-dependent CEF. Furthermore, the cfbp1 crr2 double mutant, with a defective NDH complex, was severely impaired in photosynthesis and growth, leading to the conclusion that the cfbp1 mutation imposes a demand for increased ATP production that is met by increased NDH-dependent CEF and cannot be replaced by PGR5-CEF (Livingston et al. 2010). Our study has now shown that cfbp1 not only suppresses the pgr5 lethality under FL conditions but conversely that the absence of PGR5 rescues the severe growth retardation of plants that lack cFBP1 (see Fig. 2). This is possibly due to a complementary action of increasing CEF by producing more NDH complex (Livingston et al. 2010) and increasing ATP synthase activity, assuming that PGR5 is an inhibitor of ATP synthase activity (Avenson et al. 2005); however, the experimental basis of this idea has been questioned (Yamamoto and Shikanai 2020), and there is a lack of biochemical support regarding PGR5–ATP synthase interactions. Furthermore, this interpretation contradicts the concept that PGR5-dependent CEF is more active than NDH-dependent CEF in C3 plants (Yamori and Shikanai 2016). In fact, the impact of NDH on plant CEF is still uncertain in several aspects. Despite being a highly efficient proton pump (Strand et al. 2017), plants that lack a functional NDH complex show only minor phenotypic effects (Peltier et al. 2016). It is unclear whether the observed moderate increase in NDH levels observed in our study is sufficient to markedly increase CEF. Furthermore, it is unclear why such an increase in CEF could not be achieved by increasing PGR5-dependent CEF. In fact, it is possible to increase CEF by increasing PGR5 levels, along with the accumulation of PGRL1, Fd, and FNR, as reported for PSI mutants (DalCorso et al. 2008). Basso et al. (2020) and Shikanai (2023) provided an alternative explanation for the effects seen in cfbp1, suggesting that the NDH complex may facilitate the reverse flow of electrons from PQ to Fd to alleviate the elevated pmf level in cfbp1. The uphill reaction of complex I (PQ-dependent Fd reduction) has been reported in several bacteria and suggested for cyanobacteria (Herter et al. 1998; Elbehti et al. 2000; Nikkanen et al. 2020), but direct evidence for this mechanism in plants is currently lacking. However, the observation that uncouplers enhanced the NDH-dependent PQ reduction (Strand et al. 2017) suggests that the back pressure of pmf controls NDH activity and may induce a reverse reaction. In this scenario of reverse electron flow, the decrease in PGR5 levels would serve the same purpose as the increase in NDH accumulation, since it also reduces pmf. The higher pmf in cfbp1 may also explain why the cfbp1 mutation can alleviate FL lethality of pgr5. This is because it should at least partially restore photosynthetic control.

Regarding p5s20, which is defective in ACHT2, a deficiency of ACHT2 could theoretically lead to a more active CO2 fixation, resulting in an increased sink capacity for PSI-derived electrons. However, the decreased growth of acht2 under CL conditions (see Fig. 2) and our measurements of photosynthetic electron flow (see Fig. 3) do not support this notion. Similar to cfbp1 and pgr5 cfbp1, acht2 and pgr5 acht2 also show upregulated NDH levels (see Fig. 2). This may explain why acht2 can suppress pgr5. However, unlike cfbp1, which shows decreased PGR5 levels, acht2 exhibits increased levels of PGR5. Therefore, further analyses are required to clarify why only mutations affecting cFBP1, and not other enzymes of the Calvin–Benson cycle, appear to suppress the pgr5 mutation. It is also important to determine which responses are triggered by the absence of cFBP1 and ACHT2 and whether they overlap.

Cyt b6f-related functions for DEIP1/NTA1 and PFSC1

Our pgr5 suppressor screen also found mutants with altered LEF due to impaired cyt b6f accumulation in early developmental stages. These include a mutation in CcdA in the suppressor line p5s14, which is involved in cyt b6f assembly (Page et al. 2004) (see Table 1 and Fig. 1). The effects of the pgr1 mutation in the PETC gene on LEF were not sufficient to suppress the lethality of the pgr5 mutation (see above). We have also identified mutations in DEIP1/NTA1, another bona fide cyt b6f biogenesis factor, in the absence of which plants are unable to accumulate the complex and are therefore seedling lethal (Sandoval-Ibanez et al. 2022; Li et al. 2023). However, the finding that plants lacking DEIP1/NTA1 and PGR5 are viable and only show moderate decreases in the levels of representative cyt b6f subunits at early development stages contradicts the idea that DEIP1/NTA1 is essential for cyt b6f biogenesis. It appears that DEIP1/NTA1 is critical for cyt b6f accumulation only when PGR5 is present. We conclude that PGR5 can have a negative effect on the cyt b6f complex and that DEIP1/NTA1 can ameliorate this negative effect. The mechanism by which PGR5 exerts this negative effect remains elusive. However, it is known that PGR5 can have deleterious effects. Overexpression of PGR5 or removal of its regulators PGRL1 and PGRL2 has been shown to be associated with deleterious effects on photosynthesis and growth (Okegawa et al. 2007; Long et al. 2008; Rühle et al. 2021). Furthermore, as outlined above for cfbp1, downregulation of PGR5 may be important to reduce the pmf under certain conditions, suggesting that indirect effects of PGR5 may also contribute to the suppression of the seedling-lethal deip1/nta1 phenotype by the pgr5 mutation. A direct role of PGR5 in this interaction with cyt b6f cannot be excluded either, since PGR5 does indeed interact with the Cyt b6 protein in split-ubiquitin assays (DalCorso et al. 2008) and with PetC in 2-hybrid assays (Wu et al. 2021).

Three independent suppressor lines (p5s22, 23/24, and 25) were mutated in the PFSC1 gene. The PFSC1 protein is required for the accumulation of cyt b6f in seedlings (see Fig. 7), and both the sensitivity of pfsc1 seedlings to HL (see Fig. 8) and the suppression of the pgr5 lethality under FL conditions can be attributed to the significant reduction in cyt b6f accumulation at this stage of development. Interestingly, pfsc1 seedlings are able to grow similarly to WT plants and have WT-like Fv/Fm values under LL conditions, although they express only 10% to 28% of the cyt b6f subunits tested (see Fig. 7). However, the suppression of pgr5 lethality by pfsc1 appears to occur in a different manner than by DEIP1/NTA1 deficiency, because unlike DEIP1/NTA1, PFSC1 functions independently of PGR5, as shown by the similar phenotypes observed in the pgr5 pfsc and pfsc plants with respect to cyt b6f protein accumulation (see Fig. 7). Furthermore, PFSC1 is present in all photosynthetic organisms, including cyanobacteria (see Fig. 6), whereas DEIP1/NTA1 is exclusive to plants and green algae (Sandoval-Ibanez et al. 2022; Li et al. 2023). We therefore speculate that PFSC1 has a general and conserved function in supporting the biogenesis of the cyt b6f complex, whereas DEIP1/NTA1 specifically stabilizes the cyt b6f complex in the presence of PGR5. DEIP1/NTA1 may be the third protein evolved to regulate PGR5 functions in photosynthetic eukaryotes, in addition to PGRL1 and PGRL2. Like DEIP1/NTA1, these proteins are specific to photosynthetic eukaryotes and are not present in cyanobacteria (or only as functional analogs in the case of PGRL1, see Dann and Leister (2019)).

Outlook

The pgr5 screen was able to identify those steps in photosynthesis that are affected by PGR5 deficiency and that need to be mutated to compensate for the lack of PGR5. Thus, in addition to supporting the concept of Yamamoto and Shikanai (2019) that PGR5-dependent CEF protects PSI under FL on the donor and acceptor side and the possibility of identifying factors required for the biogenesis of photosynthetic proteins involved in LEF (such as PFSC1), the screen has uncovered that PGR5 can have a deleterious effect on photosynthesis. This detrimental effect becomes apparent when cFBP1 is inactivated, resulting in a downregulation of PGR5 accumulation as described before (Livingston et al. 2010) and in our study (see Fig. 2B). Only complete inactivation of PGR5-dependent CEF by introducing the pgr5 mutation in the cfpb1 background restores WT-like growth. This behavior is similar to that observed in the pgr5 ntrc mutant, where complete removal of PGR5 results in recovery of growth, whereas the ntrc mutant exhibits severe growth retardation and a decrease in PGR5 levels (Naranjo et al. 2021). This suggests that some mutations create a situation where PGR5 expression must be downregulated to prevent its deleterious effects. Moreover, the deleterious effect of PGR5 on the accumulation of the cyt b6f complex appears to have necessitated the evolution of the DEIP1/NTA1 protein for protection, possibly indicating that this deleterious effect of PGR5 is specific to eukaryotes, since DEIP1/NTA1 is not present in cyanobacteria.

The pgr5 suppressor screen was not designed to identify direct regulators of PGR5. To identify regulators of PGR5 and elucidate its molecular function in CEF, the concept of screening for lethality suppression under FL needs to be extended. One possibility is to screen for second-site mutations that suppress lethality due to the absence of PGRL1. This approach might reveal additional factors in the PGR5-PGRL1-PGRL2 network.

Materials and methods

Plant material

In this study, Arabidopsis (A. thaliana) Col-0 and Col-5 were used as WT controls. The point mutation lines pgr5 (Munekage et al. 2002), pgr1 (Munekage et al. 2001), and pgr5 pgr1 (Yamamoto and Shikanai 2019), as well as the T-DNA lines cfbp1-1 (Rojas-Gonzalez et al. 2015), pam68 (Armbruster et al. 2010), psad1 (Ihnatowicz et al. 2004), and pgrl1ab (DalCorso et al. 2008), have been described previously. The double mutants pgr5 pam68, pgr5 psad1, and pgr5 pgr1 were generated by manual crossing of the corresponding single mutants and genotyped using the primers listed in Supplementary Table S2. The single mutant acht2-Cas and the double mutants pgr5 acht2-Cas, pgr5 deip1-Cas#1, and pgr5 deip1-Cas#2 were obtained by the introduction of a CRISPR/Cas9 construct specific to the respective target genes AT4G29670 and AT2G27290 into the Col-0 or pgr5 background as described (Penzler et al. 2022). A vector with an oocyte-specific promoter, pHEE401-E (Wang et al. 2015), was combined with the specific guide RNA (gRNA) for AT4G29670 and AT2G27290 (Supplementary Table S2). Transformation of Col-0 or pgr5 was accomplished via Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 using the floral dip method (Clough and Bent 1998). The selection of transgenic lines was carried out on plates containing MS salt medium (1×), 25 μg mL−1 hygromycin, 1% (w/v) plant agar, and 1% (w/v) sucrose, in the first generation after transformation, T1. The genes were then sequenced using the primers in Supplementary Table S2 to identify possible mutations. Lines in which the targets (ACHT2 or DEIP1/NTA1) were affected by a mutation were propagated and selected in the T2 generation to obtain stable homozygous mutant lines. The T-DNA mutants at2g04360-1/pfsc1-1 (GK-108A10) and at2g04360-1/pfsc1-2 (SALK_206798) were obtained from the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre (NASC) and selected by genotyping using the primers in Supplementary Table S2. The double mutant pgr5 pfsc1-1 was generated by manual crossing of the respective single parental lines.

Plant growth conditions

Seeds from mutant and WT plants were sown in potting soil and stratified at 4 °C for 3 d. They were then cultivated in climate chambers under various light conditions and day lengths: long day (LD), 16 h light (100 µmol photons m−2 s−1)/8 h darkness; mild HL (mHL), 16 h light (250 µmol photons m−2 s−1)/8 h darkness; HL, 16 h light (800 µmol photons m−2 s−1)/8 h darkness; CL, 12 h light (100 µmol photons m−2 s−1)/12 h darkness; and FL, 12 h light/12 h darkness, with cycles of 5 min at 50 μmol photons m−2 s−1 and 1 min at 500 μmol photons m−2 s−1 during the light period. The temperature was maintained at 22 °C during the day and 20 °C during the night, with a constant relative humidity of 60% under all conditions. Fertilizer was applied following the manufacturer’s recommendations (Osmocote Plus; Scotts, Nordhorn, Germany). For seedling experiments, seed sterilization was conducted as follows. Seeds were immersed in a solution containing 70% (v/v) EtOH and 0.01% (v/v) Tween-20 for 20 min, followed by immersion in 90% (v/v) EtOH for 10 min, all with continuous shaking. The sterilized seeds were then air-dried on sterile Whatman filter paper under aseptic conditions. The growth medium for the experiments consisted of 1% (w/v) MS medium (PhytoTechnology Laboratories, LLC, USA) and 0.8% (w/v) agar. The sterilized seeds were then transferred to the prepared growth medium in Petri dishes and stored in the dark at 4 °C for 48 h to undergo stratification. Subsequently, the MS plates were transferred to the specified growth conditions as detailed above.

EMS mutagenesis and screening

Approximately 500–600 mg of freshly harvested seeds, corresponding to ∼20,000 M0 seeds of the pgr5 mutant, were subjected to mutagenesis as follows. The seeds were placed in a 50 mL tube containing 35 mL of H2O and 30 mm EMS (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA). The EMS was dissolved by shaking for 5 min. Subsequently, the seeds were incubated in the EMS solution for 15 h with continuous shaking. After the incubation period, the seeds were rigorously washed 30 times with 50 mL of H2O to remove any residual EMS. The EMS solution was then neutralized by treatment with 0.1 m NaOH. The mutagenized seeds (M1) were air-dried on Whatman filter paper overnight and then sown on 40 trays containing soil in the greenhouse. Each tray represents 1 batch and contains ∼500 M1 seeds. The seeds harvested from each batch (M2) were later used for selection under FL growth conditions. To saturate the screen, 273,000 M2 plants were screened from 20,000 M1 individuals (Maple and Moller 2007). From the survivors, those with Fv/Fm values higher than 0.7 were selected. The pgr5 suppressor candidates of interest were backcrossed with the parental line pgr5 to remove additional mutations and selected again under FL in the second generation after crossing (F2).

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from ∼100 mg of young leaves of 5-wk-old plants within the first 30 min after light onset following the night-dark phase. The harvested material was immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and subsequently homogenized using a TissueLyser II homogenizer (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands). RNA extraction was carried out using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA), following the provided instructions. To eliminate genomic DNA contamination, the RNA was treated with DNase I (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, USA). The cDNA synthesis was carried out using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, utilizing a total of 0.5 µg of RNA. The RT-qPCR was conducted on the CFX Connect Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, USA) using SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green (Bio-Rad, Hercules, USA) and performed. For the analysis of expression levels, the CFX software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, USA) was employed.

Whole-genome resequencing and data analysis

DNA for whole-genome resequencing was obtained from the pgr5 suppressor candidates of interest in the F2 generation and after 5 wks of selection under FL. As previously described (Penzler et al. 2022), leaves from a pool of 50 to 60 plants were ground in liquid nitrogen and incubated in lysis buffer (0.4 m sucrose, 10 mm Tris-HCl pH 7.0, 1% [v/v] β-ME, 1% [v/v] Triton) on ice for 15 min. The lysate was then filtered and centrifuged for 15 min at 1,200 × g and 4 °C, and the pellet was resuspended in 1 mL of lysis buffer and centrifuged again for 15 min (600 × g, 4 °C). DNA was isolated from the supernatant using the DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Two µg of DNA were used to prepare 350 bp insert libraries for 150 bp paired-end sequencing (Novogene Biotech, Beijing, China) on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 system (Illumina, San Diego, USA) using standard Illumina protocols. The sequencing depth was at least 7 G of raw data per sample, which corresponds to higher than 50-times coverage of the Arabidopsis genome. After cleaning the FASTQ files, adapters were removed using Trimmomatic (Bolger et al. 2014), reads were mapped to the TAIR10 annotation using BWA (Li and Durbin 2009) with the parameters “mem -t 4 -k 32 -M,” and duplicates were removed using SAMtools (Li et al. 2009) with the rmdup tool. SNPs were identified using SAMtools (Li et al. 2009) with the following parameters: “mpileup -m 2 -F 0.002 -d 1000.” Only SNPs that were supported by more than 8 reads and with mapping quality > 20 were retained. To identify the SNPs specific for the candidate pgr5 suppressors (p5sX), the SNPs between p5sX and pgr5 were compared. The resulting p5sX-specific SNP list was submitted to the web application CandiSNP (Etherington et al. 2014), which generates SNP density plots. The output list of CandiSNP was screened for nonsynonymous amino acid changes and the G/C to A/T transitions that were likely to be caused by EMS, with a particular focus on the chromosome with the highest density of SNPs with an allele frequency of >0.75.

Chlorophyll fluorescence and P700 measurements in adult plants

To assess the photosynthetic performance in vivo, chlorophyll a fluorescence and P700 absorbance changes were simultaneously measured using a Dual-PAM-100 spectrophotometer (Walz, Effeltrich, Germany). The measurements were conducted on single attached leaves, dark-adapted for 30 min, using a specific program that mimics the FL growth conditions used in the screen (Supplementary Fig. S2). The maximum fluorescence (Fm) and minimum fluorescence (F0), as well as the maximum absorption of PSI (Pm), were determined by applying a saturation pulse (SP) with an intensity of 8,000 µmol photons m−2 s−1 for 0.3 s. After 40 s of darkness, the leaves were illuminated with 50 µmol photons m−2 s−1 of actinic light (LL) for 5 min. Subsequently, the actinic light was switched to 500 µmol photons m−2 s−1 for 1 min (HL). The LL/HL periods were repeated 5 and 4 times, respectively, for a total of 29 min, followed by a recovery phase of 8 min in darkness, while photosynthetic activity was continuously monitored. SPs were applied every 20 s during the LL phase, every 15 s during the HL phase, and every 20 s during the recovery phase to determine the different parameters, which were then calculated by the DUAL-PAM software using the previously described equations (Klughammer and Schreiber 2008a, 2008b). The data were presented as the mean of 3 replicates.

Chlorophyll fluorescence measurements in seedlings

The photosynthetic activity of PSII was determined in seedlings growing in MS plates by measuring the chlorophyll a fluorescence using the HEXAGON-IMAGING-PAM system (Walz, Effeltrich, Germany). The seedlings were dark-adapted for 30 min before the measurements. Fm and F0 were determined applying a SP with an intensity of 8,000 µmol photons m−2 s−1 for 0.3 s. After 40 s of darkness, a photosynthetic induction period of 360 s with 100 µmol photons m−2 s−1 of actinic light took place, followed by a recovery phase of 180 s of darkness. Yield measurements were recorded by applying SPs every 20 s, and the different parameters were then calculated by the IMAGING-PAM software using the equations described previously (Klughammer and Schreiber 2008a, 2008b). Light curves (LC) were obtained using an IMAGING-PAM spectrophotometer (Walz, Effeltrich, Germany) by applying stepwise increasing actinic light intensities every 3 min, and SPs were applied at the end of each step to calculate photosynthetic parameters as described above.

Protein extraction and immunoblot analysis

Rosette leaves or seedlings were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen after collection and ground using a TissueLyser II homogenizer (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands). The obtained powder was resuspended in 1 mL of 2× Tricine buffer per each 100 mg fresh weight of plant material. This buffer consisted of 8% (w/v) SDS, 24% (w/v) glycerol, 15 mm DTT, and 100 mm Tris-HCl pH 6.8. After homogenization, the samples were heated at 70 °C for 5 min and centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 10 min, retaining the supernatant. The volume of solubilized proteins equivalent to 1 mg of fresh weight was loaded onto 10% (w/v) tricine–SDS polyacrylamide gels. An exception was the detection of PGR5 and NTA1 proteins, for which 3 and 30 mg fresh weight, respectively, were used. The separated protein samples were transferred to PVDF membranes (Immobilon-P; Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA) using the Trans-Blot Turbo system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The PVDF membranes were blocked for 1 h with 5% (w/v) milk in Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBS-T; 10 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20). After blocking, the membranes were decorated with specific antibodies diluted in TBS-T as follows: PGR5 (1/2,500 dilution; Munekage et al. 2002), PGRL1 (1/10,000; DalCorso et al. 2008), NdhB (1/1,000; AS16 4064), NdhH (1:5,000; AS16 4065), NTA1 (1/500; Li et al. 2023), PsaA (1/5,000; AS06 172), PsbE/F (1/10,000; AS06 112), PetA (1/1,000; AS20 4377), PetC (1/5,000; AS08 330), PC (1/10,000; AS06 141), PsaD1 (1/5,000; AS09 461), and cpFBPase1 (1/50,000; AS19 4319). Antibodies against PsaA, PsbE/F, PetA, PetC, PC, PsaD1, NdhB, NdhH, and cpFBPase1 were obtained from Agrisera (Vännäs, Sweden). Proteins transferred onto the PVDF membrane were visualized by staining with Coomassie Brilliant Blue (C.B.B.) R-250 dye, ensuring equal loading of proteins. Signals were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence using the SuperSignal West Pico PLUS Chemiluminescent Substrate (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and a Fusion FX ECL reader system (Vilber Lourmat, Collégien, France). Signal intensities were quantified using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health).

Subcellular protein localization

The At2g04360 coding sequence without its stop codon was cloned into the pGWB5 vector (Nakagawa et al. 2007), and the vector was used to infiltrate extracted protoplasts from 2-wk-old Arabidopsis seedlings as described previously (Dovzhenko et al. 2003).

Alignment and phylogenetic analysis

Multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree construction were performed using the Geneious version 2023.0 created by Biomatters (https://www.geneious.com). Multiple sequence alignments were built using MUSCLE, and homologous sequences to Arabidopsis PFSC1 (Q29Q44/NP_178517.2) were identified using protein BLAST-NCBI (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi), in different organisms: camelina (Camelina sativa) (XP_019092803.1), wild turnip (Brassica rapa) (XP_009142758.1), tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) (XP_004243587.1), rice (Oryza sativa) (NP_001411979.1), Lotus japonicus (XP_057433373.1), Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 (WP_010998185.1), Synechococcus sp. PCC 7942 (WP_011243288.1), Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (WP_010872027.1), Leptolyngbya boryana (WP_017286636.1), Fischerella thermalis (WP_102178976.1), Chlorella variabilis (XP_005851345.1), Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (XP_001700636.1), Volvox carteri (XP_002950523.1), Monoraphidium neglectum (XP_013906622.1), and Ostreococcus tauri (XP_003078581.2). The mid-point rooted phylogenetic tree was constructed by maximum likelihood method, inferred using a neighbor-joining algorithm and Jukes–Cantor as the genetic distance model, using the bootstrap (n = 100) method (Felsenstein 1985). The alignment and machine-readable tree are provided as Supplementary Files 1 and 2.

Proteomics analysis

Total proteins were extracted from 4-d-old WT and pfsc1-1 seedlings (4 biological replicates for each genotype, of which 1 WT and 2 pfsc-1-1 were later excluded as outliers from further analysis). Proteome preparation, trypsin digestion, and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) were performed as previously described (Marino et al. 2019).

Raw data were processed using the MaxQuant software 1.6.17.0 (Cox and Mann 2008), using the built-in Andromeda search engine (Cox et al. 2011) with default settings. Database searches were performed against the Arabidopsis reference proteome (UniProt, www.uniprot.org, version April 2021). Proteins were quantified across samples using the label-free quantification (LFQ) algorithm (Cox et al. 2014) with the match-between-runs option enabled. For downstream statistical analysis, Perseus version 1.6.15.0 (Tyanova et al. 2016) and RStudio version 1.2.5019 (RStudio Team, 2020) were used. Significantly differentially abundant protein groups were calculated employing the R/Bioconductor package limma (Andrews 2010), with P-values adjusted for multiple comparisons according to the Benjamini–Hochberg approach (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995). Proteins were considered to show a significant change with an FC relative to the WT larger than 1.5 (upregulated) or lower than 0.66 (downregulated) and with an false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05.

The MS proteomics data were deposited at the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE (Perez-Riverol et al. 2019) partner repository with the data set identifier PXD047221.

Statistical analyses

Statistical significance of differences, except for the proteomics analysis, was assessed using 1-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey HSD test (https://astatsa.com/, version October 2023).

Accession numbers

ATG accession numbers: AT2G05620 (PGR5), AT4G19100 (PAM68), AT4G03280 (PGR1), and AT4G02770 (PSAD1). Additional accession numbers are listed in Table 1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Shikanai for providing the pgr5, pgr1, and pgr5 pgr1 seeds and the PGR5-specific antibody and Prof. He for the NTA1-specific antibody. We also thank Hannah Kallus for her excellent technical assistance. The text is entirely our own, although it has been improved with the help of deepL (https://www.deepl.com/write).

Contributor Information

Jan-Ferdinand Penzler, Plant Molecular Biology, Faculty of Biology, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Planegg-Martinsried D-82152, Germany.

Belén Naranjo, Plant Molecular Biology, Faculty of Biology, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Planegg-Martinsried D-82152, Germany.

Sabrina Walz, Plant Molecular Biology, Faculty of Biology, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Planegg-Martinsried D-82152, Germany.

Giada Marino, Plant Molecular Biology, Faculty of Biology, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Planegg-Martinsried D-82152, Germany.

Tatjana Kleine, Plant Molecular Biology, Faculty of Biology, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Planegg-Martinsried D-82152, Germany.

Dario Leister, Plant Molecular Biology, Faculty of Biology, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Planegg-Martinsried D-82152, Germany.

Author contributions

The research was designed by D.L. and B.N.; J.-F.P., B.N., and S.W. performed the experiments; G.M. performed the proteomics analysis; T.K. analyzed the resequencing data; D.L., B.N., and J.-F.P. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplementary Figure S1. Mutations in proteins identified in the course of the pgr5 suppressor screen and additional alleles generated by CRISPR/Cas.

Supplementary Figure S2. Example of FL measurements.

Supplementary Figure S3. RT-qPCR analysis of AT2G04360 mRNA accumulation in WT (Col-5) and mutant (pgr5, pgr5 at2g04360-1, at2g04360-1, and at2g04360-2) adult plants.

Supplementary Table S1. Proteins expressed differentially in pfsc1-1 compared with Col-0.

Supplementary Table S2. Oligonucleotide sequences used for genotyping, gRNA, sequencing, and cloning.

Supplementary Data Set 1. List of all proteins identified by shotgun proteomics.

Supplementary File 1. Figure 6B Alignment.fasta

Supplementary File 2. Figure 6C Tree.newick

Funding

The authors acknowledge the financial support provided by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant TRR175 B07 and C01 to B.N., D.L., and T.K.) and the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación/Agencia Estatal de Investigacion (grant IJC2019-040972-I funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 to B.N.)

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material.

Dive Curated Terms

The following phenotypic, genotypic, and functional terms are of significance to the work described in this paper:

Literature Cited

- Andrews S. FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. Available online at: http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc. 2010