Abstract

Equine rhinitis A virus (ERAV) is a respiratory pathogen of horses and is classified as an Aphthovirus, the only non-Foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) member of this genus. In FMDV, virion protein 1 (VP1) is a major target of protective antibodies and is responsible for viral attachment to permissive cells via an RGD motif located in a distal surface loop. Although both viruses share considerable sequence identity, ERAV VP1 does not contain an RGD motif. To investigate antibody and receptor-binding properties of ERAV VP1, we have expressed full-length ERAV VP1 in Escherichia coli as a glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein (GST-VP1). GST-VP1 reacted specifically with antibodies present in serum from a rabbit immunized with purified ERAV virions and also in convalescent-phase sera from horses experimentally infected with ERAV. An antiserum raised in rabbits to GST-VP1 reacted strongly with viral VP1 and effectively neutralized ERAV infection in vitro. Using a flow cytometry-based binding assay, we found that GST-VP1, but not other GST fusion proteins, bound to cell surface receptors. This binding was reduced in a dose-dependent manner by the addition of purified ERAV virions, demonstrating the specificity of this interaction. A separate cell-binding assay also implicated GST-VP1 in receptor binding. Importantly, anti-GST-VP1 antibodies inhibited the binding of ERAV virions to Vero cells, suggesting that these antibodies exert their neutralizing effect by blocking viral attachment. Thus ERAV VP1, like its counterpart in FMDV, appears to be both a target of protective antibodies and involved directly in receptor binding. This study reveals the potential of recombinant VP1 molecules to serve as vaccines and diagnostic reagents for the control of ERAV infections.

Equine rhinitis A virus (ERAV), formerly known as equine rhinovirus 1, is a member of the Aphthovirus genus in the family Picornaviridae (26). This genus is otherwise comprised of the different serotypes of Foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV). In addition to considerable sequence identity (17, 34), ERAV and FMDV share a range of physicochemical and biological properties (14, 23, 24). ERAV infection of horses results in an acute febrile respiratory disease that is accompanied by viremia and persistent virus shedding in urine and feces (for a review, see reference 30). It has been shown to be responsible for relatively large outbreaks of acute respiratory illness in adult horse populations, although much remains to be learned about the epidemiology and pathogenesis of this pathogen (18). Such studies are complicated by the likelihood that many isolates are not cytopathic for in vitro-cultured cells (18). Despite being primarily an infectious agent of horses, ERAV is also pathogenic for a broad range of other animal species, including humans (24, 25). There is currently no vaccine to control ERAV infection, and only limited diagnostic tools are available.

The genome of all picornaviruses is single-stranded, positive-sense RNA containing a single, long open reading frame that encodes the viral polyprotein (27). Processing of the polyprotein produces several nonstructural proteins as well as four structural polypeptides, termed VP1, VP2, VP3, and VP4, which together form the virus capsid. Of the four capsid proteins, VP1 exhibits the most variability, particularly in the loops that project from the virion surface (27). Several sites of importance for the induction of neutralizing antibodies have been found concentrated in these unstructured, hypervariable loops, including the BC loop for poliovirus and human rhinovirus and the GH loop of FMDV (29). Interestingly, the predicted loops of ERAV VP1 are longer than those of FMDV, with the exception of the GH loop (34).

The great majority of natural FMDV strains contain the highly conserved RGD tripeptide located at the apex of the GH loop. This motif is invariant even when FMDV isolates are subjected to strong selective pressure by antibodies (1). Structural studies have shown that the RGD motif participates directly in the interaction with neutralizing antibodies (13, 32). The GH loop has been reported to contain at least 10 distinguishable, overlapping epitopes within residues 138 to 150 of FMDV type C (20). There are seven serotypes of FMDV in addition to multiple subtypes. These are highly variable in their GH loop composition, with the exception of the RGD motif; consequently, there is little cross-protection between serotypes (3). In contrast, ERAV isolates from around the world appear to belong to a single serotype, and little sequence diversity has been observed in the capsid proteins (17, 18, 30, 34; A. Varrasso et al., unpublished observations).

The FMDV RGD motif is directly involved in integrin receptor recognition (2, 16, 22); however, ERAV does not encode an RGD motif in the GH loop or in any other region of the capsid proteins (17, 34). Culture-adapted strains of FMDV have been reported to acquire a high affinity for the heparan sulfate (HS)-binding motif and can apparently use HS proteoglycans as receptors for both attachment and internalization (15). It has been noted that the C terminus of FMDV VP1 includes a stretch of basic amino acids, 200-RHKQKI-205, which is similar to the heparan binding site of vitronectin (KKQRF) (15) and that ERAV possesses a similar stretch of amino acids (KTRHK) at the same location within the VP1 protein (17). A recent structural study, however, has shown that the HS-binding site of FMDV (strain 01BFS) is a shallow depression on the virion surface, located at the junction of the three major capsid proteins (10). Although residues at the C terminus of VP1 were involved in this interaction, especially His195, 200- RHKQKI-205 did not appear to be involved.

In this report, we describe the expression in Escherichia coli of full-length ERAV VP1 as a glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein. The expressed protein bound antibodies present in convalescent-phase sera from infected horses and elicited a strong neutralizing antibody response in an immunized rabbit. We also show that the E. coli-expressed ERAV VP1 binds to cells in a manner that appears to mimic viral attachment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and virus.

Vero cells were grown in minimal essential medium (MEM) containing 2 mM glutamine (Gibco), 2 mM pyruvate, 30 μg of gentamicin (Roussel)/ml, 100 IU of penicillin/ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin/ml and were supplemented with 5% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS; CSL Pty. Ltd., Parkville, Australia). The ERAV isolate used in this study, 393/76, has been described previously (17, 31). Infected cell culture supernatant was prepared by adding virus to cells and allowing adsorption before the addition of MEM containing 1% (vol/vol) FCS. The supernatant was collected at 24 h postinfection, clarified at 2,500 × g for 10 min, filtered, and stored at −70°C for further use. Purified virus for binding inhibition assays was concentrated from clarified (10,000 × g; 15 min at 4°C) cell culture supernatant of ERAV-infected Vero cells by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 2 h at 4°C. The pellet was resuspended in TNE (0.01 M Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 0.1 M NaCl, and 1mM EDTA) containing 1% sarcosyl–1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and was pelleted through a 10% sucrose cushion at 100,000 × g for 2 h at 4°C. The resuspended virus was then purified through a 15 to 45% (wt/vol) sucrose gradient at 80,000 × g for 4 h at 4°C, and the gradient was collected in 1-ml fractions. Virus-containing fractions (determined by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis [PAGE]) were pooled before pelleting at 100,000 × g for 2 h at 4°C and were resuspended in TNE.

Cloning and expression of ERAV VP1.

The full-length VP1 was amplified from the purified RNA of ERAV.393/76 by reverse transcriptase PCR using synthetic oligonucleotide primers. The positive-sense primer 5′-GGCGTCGACGTTACCAATGTGGGCGAGGAT-3′ contains a SalI cleavage site followed by nucleotides 3088 to 3108 of ERAV, and the negative-sense primer 5′-TCACTGTTTGTTGATGTTAG-3′ bears a stop codon followed by nucleotides 3831 to 3809 of ERAV (17). A single PCR product corresponding to the expected size of the full-length VP1 coding sequence was obtained. The PCR DNA was purified and ligated into pGEM T-Easy (Promega, Madison, Wis.). DNA from a positive clone was then subcloned by digestion with SalI and NotI and was ligated into the SalI- and NotI-digested pGEX-4T3 expression vector (Amersham Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden). Ligated products were transformed into E. coli XL10 Gold (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) by electroporation (Gene Pulser II; Bio-Rad). DNA from a positive clone was then electroporated into E. coli BL21(DE3) (Amersham Pharmacia) for protein expression. Large-scale fusion protein preparations were prepared as recommended by the supplier. Briefly, overnight cultures were used to seed 1.6-liter Luria broth cultures at 1:100 and were incubated at 37°C for 2.5 h. Cultures were then induced with 0.02 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG; Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) and were incubated at 30°C for 1.5 h. The cells were then lysed using lysozyme (Boehringer Mannheim) and were sonicated prior to the addition of Triton X-100 (U.S. Biochemical, Cleveland, Ohio) to a final concentration of 1%. The soluble fusion protein was affinity purified using glutathione-Sepharose (Amersham Pharmacia) and was eluted using 20 mM reduced glutathione (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.).

Immunoblotting.

Purified fusion protein was subjected to electrophoresis in 12% polyacrylamide gels, electrotransferred to an Immobilon polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.), and blocked overnight at 4°C with either 5% skim milk or 10% goat serum in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The membranes were incubated for 2 h at room temperature with either rabbit anti-ERAV diluted 1/10,000 in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBST) and 2.5% skim milk or the convalescent-phase horse sera diluted 1/250 in PBST containing 5% goat serum. After extensive washing in PBST, the antibodies were detected with either a 1/4,000 dilution of sheep anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Silenus, Melbourne, Australia) or a 1/4,000 dilution of goat anti-horse IgG (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, Ala.), both conjugated with horseradish peroxidase. Reactions were detected using Enhanced Chemiluminescence Reagent Plus (NEN Life Sciences Products Inc., Boston, Mass.). For detection of GST fusion proteins, the primary antibody diluent contained 5 μg of GST/ml to adsorb GST-reactive antibodies.

Sera.

The experimental infection of horses with ERAV has been described previously (11). Acute- and convalescent-phase sera from horses C and G (11), here termed horses 1 and 2, respectively, were used. Rabbit hyperimmune sera were prepared against whole UV-inactivated ERAV.393/76 as described previously (11). Rabbit immune sera to full-length recombinant GST-VP1 were prepared by the subcutaneous immunization of an outbred New Zealand White rabbit with 70 μg of GST-VP1 emulsified in Freund's complete adjuvant (Sigma-Aldrich, Castle Hill, Australia). This rabbit was boosted twice at 4-week intervals with 25 μg of GST-VP1 in Freund's incomplete adjuvant (Sigma). Mouse immune sera to full-length recombinant GST-VP1 were prepared by the intraperitoneal immunization of two BALB/c mice with 10 μg of GST-VP1 emulsified in Freund's complete adjuvant. The mice were subsequently boosted three times at 3-week intervals with 8 to 10 μg of GST-VP1 in Freund's incomplete adjuvant.

SN assays.

Dilutions of test sera were made in sterile, flat-bottomed Linbro microtiter plates (ICN Biomedicals) and were incubated with an equal volume of pretitrated virus (100 50% tissue culture infection doses) at 37°C for 1 h. A suspension of Vero cells (50 μl; 104 cells/ml) in MEM containing 2% FCS was then added to each well, and the plate contents were incubated for a further 72 to 96 h at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. Serum neutralization (SN) titers are expressed as the reciprocal of the highest dilution of serum that neutralized 100 50% tissure culture infective doses of virus.

Cell-binding assay using flow cytometry.

The binding of GST-VP1 to cells was detected by flow cytometry analysis based on a modification of the technique used by Londrigan et al. (19). Briefly, an approximately equimolar amount of purified GST-VP1 (∼12 μg of the 54-kDa species) or a GST control (5 μg) was added to 5 × 105 Vero (African green monkey kidney), COS-7 (African green monkey kidney), BHK-21 (Syrian golden hamster kidney), L929 (mouse connective tissue), MDCK (canine kidney), or CHO (Chinese hamster ovary) cells in suspension in round-bottomed tubes. To derive the suspension culture, confluent cell monolayers were washed twice with PBS. Cells were detached by incubation for 3 min with a solution containing 0.01% (wt/vol) trypsin (Difco) and 0.02% (wt/vol) EDTA and were resuspended in approximately 10 ml of MEM containing 1% (vol/vol) FCS. The cell suspension was then incubated for 30 min at 37°C to allow trypsin-sensitive molecules to regenerate, and the cells were counted. All further volumes were 50 μl, and all incubations were on ice for 45 min. Cells were washed with fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) wash buffer (PBS containing 1% [vol/vol] FCS and 0.1% [wt/vol] sodium azide) before incubation with rabbit anti-GST serum at 1/500 and washing with FACS wash buffer, followed by incubation with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated swine anti-rabbit immunoglobulins diluted 1/50. Cells were fixed with 500 μl of 1% ultrapure formaldehyde (Polysciences) in PBS and were analyzed using a FACSort flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) set for detection of FITC. Populations of viable cells were selected by gating dot plots, and fluorescence intensity histograms of the gated populations were constructed. Binding to cells was considered positive when the relative linear median fluorescence intensity (RLMFI) value was greater than 1.2 (median fluorescence intensity with GST-VP1-bound cells/median fluorescence intensity with GST-bound cells [33]). For virus inhibition, 1 to 20 μg of purified ERAV virions (which was considered approximately equimolar to the amount of the 54-kDa GST-VP1 fusion protein) was added to cells before the addition of fusion protein. Cells were incubated for 15 min on ice before we proceeded with the assay as described above.

Depletion of GST-VP1 using Vero cells.

Approximately 0.5 μg of GST-VP1 and 0.6 μg of GST were combined in PBS to a total volume of 100 μl. An aliquot of 20 μl was removed from the mix and adsorbed with excess glutathione-Sepharose beads. Another aliquot of 20 μl was removed from the mix and was stored on ice as a prebinding control sample. The remaining solution was used to resuspend a pellet of 4 × 105 Vero cells and was incubated at 4°C for 45 min. After incubation, the cell-fusion protein mix was centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 5 min and a 20-μl aliquot of the supernatant was removed for analysis. The procedure was repeated for a total of three adsorption steps. The collected supernatants were subjected to SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes, and probed with a mouse anti-GST monoclonal antibody diluted 1/750 and a rabbit anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase conjugate diluted 1/4,000. Densitometry was performed using Kodak 1D analysis software (Eastman Kodak, New Haven, Conn.).

Binding assay using biotin-labeled virions.

Purified ERAV.393/76 (50 μg) in 400 μl of 50 mM bicarbonate buffer (pH 8.5) was incubated with 2.7 mg of EZLink sulfo-NHS biotin (Pierce) for 60 min at room temperature. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 40 μl of 10× TNE, and the suspension was dialyzed overnight against at least 50 times the volume of PBS, with one change of dialysis buffer. Successful biotinylation of virus proteins was confirmed by Western blot analysis. To detect direct binding, 5 × 105 Vero cells were incubated with 0.5 μg of biotinylated ERAV.393/76 on ice for 45 min and bound virus was detected by flow cytometry following incubation with FITC-conjugated streptavidin (DAKO) diluted 1/50. For binding inhibition assays, 10 or 100 μg of IgG was preincubated with the biotinylated ERAV.393/76 for 60 min at 37°C before being added to the cells.

RESULTS

Expression and antibody reactivity of ERAV GST-VP1 fusion protein.

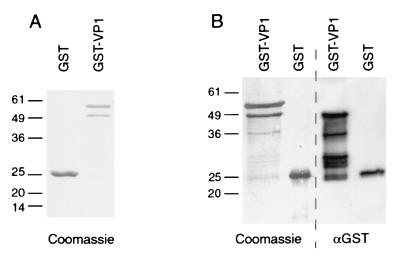

Full-length ERAV VP1 was expressed as a GST fusion protein in E. coli. For this, a PCR product encoding ERAV VP1 was ligated into the pGEX4T-3 expression vector to derive the plasmid pGST-VP1 (Fig. 1). The N terminus of the expressed VP1 was chosen as that predicted previously (17, 34) and which has now been confirmed by N-terminal protein sequencing (11). The C terminus of the expressed VP1 was chosen as 2 amino acids upstream of that originally predicted (17, 34) following the work of Donnelly and coworkers (8). The expressed fusion protein, termed GST-VP1, was only partially soluble, with most of the expressed protein (∼80%) forming inclusion bodies. GST-VP1 purified on glutathione-Sepharose beads consistently migrated as a doublet, most commonly with Mr of 54,000 and 59,000 (Fig. 2A), although in some gels the doublet migrated slightly more rapidly (Fig. 2B). The predicted size of the full-length fusion protein is 56 kDa (comprised of 26-kDa GST plus 30-kDa VP1). Only the more rapidly migrating species reacted with an anti-GST monoclonal antibody (Fig. 2B).

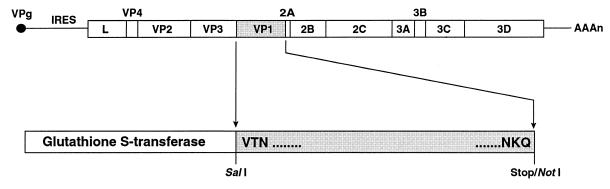

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagram of the ERAV genome and design of recombinant ERAV GST-VP1 fusion protein. The locations of the encoded polypeptides and the internal ribosomal entry site (IRES) are indicated. For the amplification of ERAV VP1, a SalI restriction site was included in the sense primer and a stop codon followed by a NotI site was included in the antisense primer. The VP1 PCR product was ligated into the pGEX4T-3 vector downstream of the GST gene, and the N-terminal and C-terminal amino acids of VP1 included in the clone are shown.

FIG. 2.

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis of GST and GST-VP1 recombinant proteins. (A) Purified proteins separated on an SDS–12% PAGE gel under reducing conditions and stained with Coomassie blue. (B) Duplicate samples separated on the same SDS-PAGE gel were transferred to a PVDF membrane and were either stained with Coomassie blue or probed with anti-GST monoclonal antibody (αGST) diluted 1/750. Positions of Mr standards (in thousands) are given to the left of each panel.

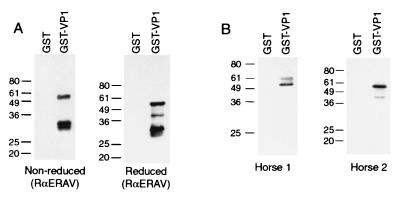

GST-VP1 was examined by immunoblotting for reactivity to various anti-ERAV sera. Serum from a rabbit hyperimmunized with purified ERAV virions reacted strongly to the 54-kDa species under both reducing and nonreducing conditions (Fig. 3A). Smaller reactive species (30 to 42 kDa), which presumably represent minor breakdown products, were also seen in the GST-VP1 lanes. Convalescent-phase sera from two different horses that had been experimentally infected with ERAV also reacted specifically with the 54-kDa species (Fig. 3B). Preimmune horse sera showed no reactivity (data not shown). These results highlight the presence of authentic VP1 B-cell epitopes in the recombinant protein. The larger 59-kDa species showed no reactivity with either the rabbit anti-ERAV serum or the horse 2 serum and relatively weak reactivity with antibodies from horse 1 (Fig. 3). The lack of reactivity of the 59-kDa species was confirmed by Coomassie blue staining of parallel Western blot strips (data not shown). Given that the 59-kDa species also does not react with anti-GST antibody, it is likely that this band represents a nonspecific E. coli protein that copurifies with the 54-kDa GST-VP1 fusion protein.

FIG. 3.

Reactivity of polyclonal rabbit and horse sera with GST-VP1. (A) Western blot showing reactivity of a rabbit anti-ERAV (whole virion) serum (RαERAV) diluted 1/10,000. Prior to Western blotting, samples were separated by SDS-PAGE run under either nonreducing or reducing conditions as indicated under each panel. (B) Western blot showing reactivity of sera from two horses (horse 1 and horse 2) following experimental infection with ERAV (11). SDS-PAGE was performed under reducing conditions. Sera were tested at a 1/250 dilution. The positions of the Mr standards (in thousands) are shown to the left of each gel.

ERAV GST-VP1 elicits a strong neutralizing antibody response.

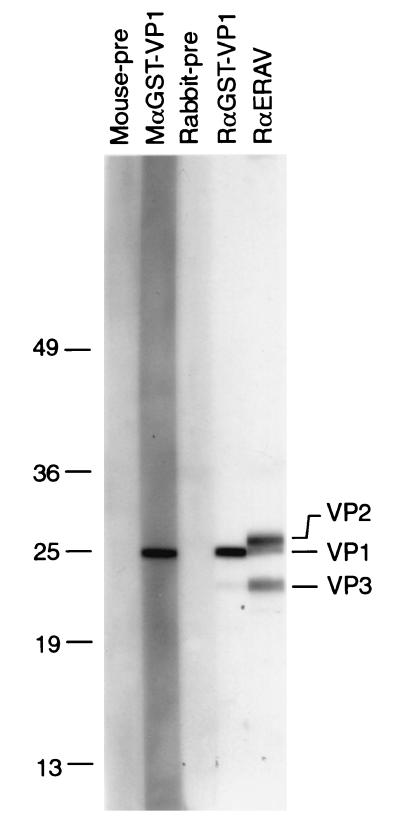

To test if GST-VP1 is capable of eliciting a VP1-specific neutralizing antibody response, two BALB/c mice and one outbred New Zealand White rabbit were immunized with the fusion protein. Sera from both the hyperimmunized mice and rabbit reacted strongly with a 25-kDa protein present in purified virions (Fig. 4). This species is the lower band of a doublet present at this molecular weight detected by the rabbit anti-ERAV serum. The result is consistent with N-terminal sequence analysis of purified virion proteins, which had previously suggested that the upper band in the 25-kDa doublet represented VP2, while the lower band represented VP1, and the 21-kDa species represented VP3 (11). Rabbit anti-GST-VP1 antibodies also showed weak cross-reactivity with a smaller species that comigrated with VP3. This species most likely represents a VP1 breakdown product, and indeed in a repeat Western blot with the same sera, this smaller species migrated slightly faster than VP3 (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Reactivity of polyclonal antisera with ERAV viral proteins. Viral proteins prepared from purified virions were separated on a 10 to 15% gradient polyacrylamide gel and were transferred to a PVDF membrane. Membrane strips were probed with preimmune serum (Rabbit-pre or Mouse-pre), rabbit and mouse anti-GST-VP1 (RαGST-VP1 and MαGST-VP1), and rabbit anti-ERAV hyperimmune serum (RαERAV). Note that Mouse-pre and MαGST-VP1 represent a pool of sera from two mice. The positions of Mr standards (in thousands) are shown on the left.

Sera from the GST-VP1-immunized mice (and sera from control BALB/c mice) were found to be cytotoxic for Vero cells over a broad dilution range so that an SN antibody titer could not be determined (data not shown). This was not the case for sera from the GST-VP1-immunized rabbit. An SN titer of 320 to 400 was obtained following two immunizations in this rabbit, which rose to 400 to 526 after a further boost (Table 1). An SN titer of 200 to 320 was determined for the rabbit anti-ERAV serum. Hence, neutralizing antibodies may be elicited in rabbits by the GST-VP1 fusion protein to a titer comparable to that produced by immunization with inactivated whole virus.

TABLE 1.

Immunization with GST-VP1 generates neutralizing antibodies

| Immunogenb | SN titersa

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preimmune | Post-2nd immunization | Post-3rd immunization | |

| GST-VP1 | <10/<10 | 320/400 | 400/562 |

| ERAV virions | ND | ND | 200/320 |

SN titers were determined from two independent assays. The values shown are the titers obtained in assay 1 and assay 2, respectively. ND, not determined.

Represents the proteins used to immunize rabbits.

Evidence for receptor-binding site in VP1.

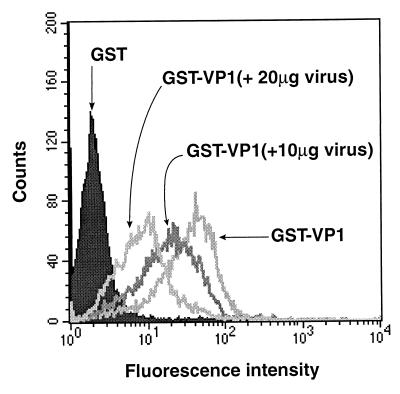

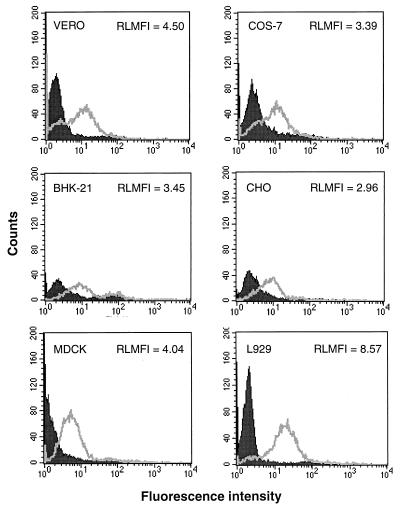

To investigate if ERAV VP1 possesses a receptor-binding site, GST-VP1 was tested for its ability to bind to Vero cells, a line permissive for infection by ERAV. Binding was detected by flow cytometry after incubations with rabbit anti-GST and FITC-labeled anti-rabbit immunoglobulin. Cells incubated with GST-VP1 showed strong fluorescence relative to those incubated with GST alone (Fig. 5). This was a consistent result that was observed in numerous repeat experiments and also when a mouse anti-GST monoclonal antibody was used to detect binding (data not shown). Furthermore, three other GST fusion proteins were tested, and each showed a complete absence of binding in this assay (data not shown). To further test the specificity of the GST-VP1 binding, different amounts of purified ERAV virions (1, 10, and 20 μg) were added to the Vero cell suspensions and were allowed to bind prior to the addition of GST-VP1. This treatment inhibited GST-VP1 binding in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5; note that 1 μg of virus had no effect on GST-VP1 binding and hence is not shown on this figure). A repeat experiment gave an identical result (data not shown). This data is consistent with the binding of GST-VP1 to the same cell surface receptor as ERAV virions. Since ERAV has a broad host range, we tested if GST-VP1 could bind to different cell types. In addition to Vero cells, GST-VP1 binding, as measured by increased cellular fluorescence over the GST control, was detected in COS-7, CHO, BHK-21, MDCK, and L929 cells, although the specificity of these interactions was not confirmed by competition with purified virions (Fig. 6). Taken together, these data are consistent with the presence of a receptor-binding site on ERAV VP1.

FIG. 5.

Binding and inhibition of binding of GST-VP1 to Vero cells. The binding of GST fusion proteins to cells was detected by FACS analysis following staining with a rabbit anti-GST antibody. The fusion protein and amount of purified ERAV virions are shown. The RLMFI values (comparing fluorescence intensity of GST-VP1-labeled cells to that of GST-labeled cells) are not shown on this figure but were as follows: GST-VP1, 14.07, GST-VP1 (+ 10 μg of virus), 9.38; and GST-VP1(+ 20 μg of virus), 4.13.

FIG. 6.

Binding of GST-VP1 to different cell lines. Full-length GST-VP1 fusion protein (unfilled) and GST control (filled) were incubated with 5 × 105 Vero, COS-7, BHK-21, CHO, MDCK, and L929 cells. The cells were then stained with rabbit polyclonal anti-GST antibodies and were analyzed by FACS as described in Materials and Methods. RLMFI values (comparing fluorescence intensity of GST-VP1-labeled cells to that of GST-labeled cells) are shown.

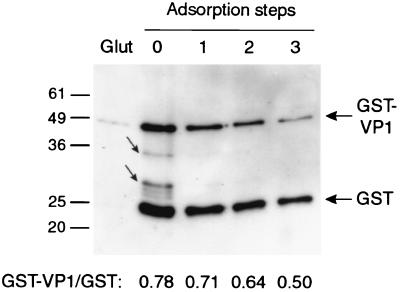

An alternate assay was also performed to independently test the ability of GST-VP1 to bind Vero cells. In this assay, a mixture of GST-VP1 and GST proteins was adsorbed with Vero cells. The binding of GST-VP1 was monitored by immunoblot analysis of aliquots of the GST-VP1–GST mixture, sampled before and after each adsorption step, with an anti-GST monoclonal antibody. The ratio of GST-VP1 to GST decreased incrementally from 0.78 prior to incubation with Vero cells to 0.50 after three adsorption steps, indicating a specific depletion of GST-VP1 (Fig. 7, bottom). Note that the sequential decrease in the intensity of the GST band is attributed to the small increase in volume, and hence dilution of sample, during each adsorption step. Interestingly, smaller breakdown products of GST-VP1 were rapidly removed by Vero cell adsorption (indicated by the small arrows in Fig. 7). These proteins were also removed by incubation with glutathione-Sepharose beads, confirming the presence of an active, presumably full-length GST fusion partner in these species (Fig. 7). This data suggests that the receptor-binding site in GST-VP1 may be located in the N-terminal region of VP1.

FIG. 7.

Specific adsorption of GST-VP1 by Vero cells. GST-VP1 and GST fusion proteins were combined and sequentially adsorbed with Vero cells. Aliquots of the mixture were removed prior to adsorption (absorption step 0) and following each adsorption (adsorption steps 1, 2, and 3) and were analyzed by reducing SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with an anti-GST monoclonal antibody. Prior to adsorption, an equal aliquot of the GST-VP1–GST starting mixture was adsorbed with glutathione-Sepharose beads (Glut) prior to loading. The intensities of the GST-VP1 and GST bands were determined by densitometric analysis and are expressed as ratios below the figure. GST-VP1 breakdown products are highlighted by the small arrows. The positions of Mr standards (in thousands) are shown to the left.

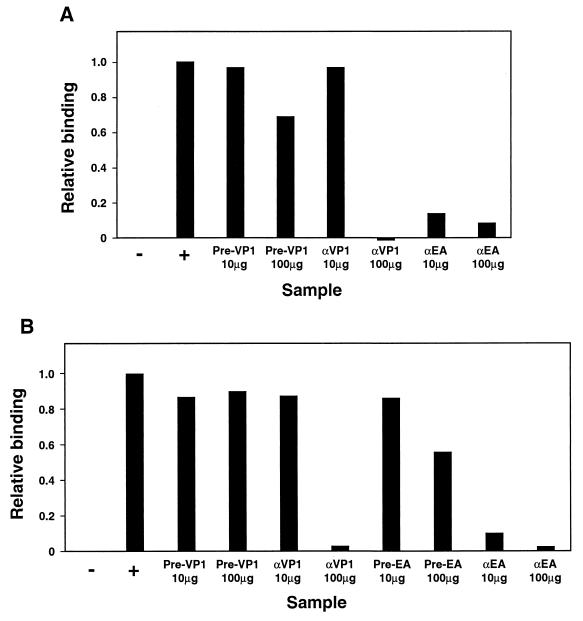

In order to examine if neutralizing antibodies raised to recombinant VP1 prevented viral attachment, rabbit anti-GST-VP1 IgG was tested for its ability to inhibit the binding of biotinylated ERAV virions to Vero cells. In two separate assays it was evident that 100 μg, but not 10 μg, of anti-GST-VP1 IgG effectively inhibited the attachment of ERAV to cells (Fig. 8). IgG prepared from prebleed sera from this same rabbit did not inhibit virus binding in this assay. Antibodies from a rabbit immunized with whole virions (anti-ERAV IgG) were more effective at inhibiting the binding of biotinylated ERAV virions, demonstrating inhibition at both 10 and 100 μg of IgG (Fig. 8). These results are consistent with the notion that at least one way that anti-GST-VP1 antibodies neutralize viral infectivity is by inhibiting viral attachment to the cellular receptor.

FIG. 8.

Anti-GST-VP1 IgG inhibits the binding of ERAV virions to Vero cells. Biotinylated ERAV virions were incubated with IgG prepared from rabbits immunized with either recombinant GST-VP1 (αVP1) or whole ERAV virions (αEA) or with prebleed sera from these rabbits (Pre-VP1 or Pre-EA, respectively) before incubation with Vero cells. Virus binding was detected by flow cytometry. Panels A and B represent the results from two independent experiments. For each sample, the mean RLMFI was obtained from duplicate samples and corrected for background binding by subtraction of the mean value obtained for the negative control sample, which has no virus or IgG added (−). Final results (relative binding) are expressed as a proportion of the RLFMI obtained for the positive control virus-only sample (+).

DISCUSSION

The emerging significance of ERAV as a pathogen for horses (5, 18), as well as its close relationship to FMDV (17, 34), a virus of major worldwide importance, highlights a need to better understand the pathogenic processes adopted by ERAV. In this study, we show that ERAV VP1 is a target of protective antibodies and provide evidence that this molecule is involved directly in viral attachment to host cells.

It has long been known that FMDV VP1 is the immunodominant capsid protein of this virus (3, 4, 12) and that there are multiple regions within the FMDV VP1 protein that induce neutralizing antibodies (4, 9). To investigate B-cell responses to ERAV VP1, recombinant, full-length ERAV VP1 protein fused to the C terminus of GST was produced. In SDS-PAGE, GST-VP1 consistently migrated as a doublet at 54 and 59 kDa. Both species are close to the theoretical Mr of GST-VP1, but by several analyses it appeared that the faster-migrating 54-kDa species represented GST-VP1. We show that antibodies raised against ERAV virions, both in an immunized rabbit and in experimentally infected horses, react specifically against this species. This indicates that ERAV VP1 is immunogenic in the context of the wild-type virus and also that the GST-VP1 fusion contains B-cell epitopes that resemble those present in native VP1. Furthermore, immunization of laboratory animals with GST-VP1 resulted in the production of antibodies that reacted specifically with viral VP1, confirming the presence of authentic VP1 epitopes in the fusion protein. Importantly, sera from a rabbit immunized with GST-VP1 strongly neutralized ERAV infection in in vitro assays. Although the relatively poor yields of fusion protein limited the number of animals that were immunized in this study, this finding establishes the potential of mounting a protective response with recombinant ERAV VP1 protein.

The identification of ERAV VP1 as a target of protective antibodies raised the possibility that this protein may be responsible for attachment to host receptors. To address this we developed an assay that employed anti-GST antibodies to detect GST-VP1 binding to cells by flow cytometry. By this approach, we demonstrated that GST-VP1 binds to Vero cells and that this binding is reversible with the addition of purified ERAV virions. The data imply that native ERAV VP1 participates directly in binding to a cellular receptor and that this interaction is mimicked by the GST-VP1 fusion protein. This finding is consistent with the ability of GST-VP1 to elicit neutralizing antibodies.

Furthermore, using a receptor-binding assay that employs biotinylated ERAV virions, we provide evidence that anti-GST-VP1 antibodies interfere with attachment of ERAV to the VP1 receptor in question. We note, however, that antibodies raised to whole virions are more effective than anti-GST-VP1 antibodies at inhibiting receptor binding in this assay, despite exhibiting similar or slightly lower neutralizing antibody titers. This suggests that anti-GST-VP1 antibodies may neutralize infectivity by a mechanism(s) in addition to the blocking of viral attachment. Nevertheless, this result is consistent with the assertion that recombinant VP1-GST protein and ERAV virions bind to the same cell surface receptor. We note, however, that recombinant GST-VP1 protein was not in itself able to neutralize viral infectivity (data not shown). This result is not surprising, given the multivalency of ERAV virions, the likelihood that they bind receptors at substantially higher affinity than does GST-VP1, and the possibility that virions possess other receptor-binding sites that are not represented in recombinant VP1.

In another approach to examine receptor-binding properties of recombinant VP1, we showed that incubation of Vero cells with a mixture of GST-VP1 and GST proteins resulted in the specific depletion of GST-VP1, including that of smaller breakdown products that contain only the N-terminal residues of VP1. This region of VP1 contains a DGE tripeptide (located 7 to 9 residues from the N terminus) that is known to function as a recognition motif for the α2β1 integrin (28) and is potentially used for receptor binding in some viruses (6). We speculate that this motif may be involved in cell attachment. Indeed, as part of a study to investigate this in some detail, we have shown that a GST fusion protein that encompasses just the N-terminal region of VP1 binds to cells in the FACS-binding assay (S. Warner and B. S. Crabb, unpublished data). This fusion protein also reacts strongly to antibodies present in convalescent-phase horse sera. Together, these data suggest that this region of VP1 is exposed and accessible by antibodies in the context of the complete virus particle and is supportive of a role for sequence surrounding the DGE motif in viral attachment.

Previous work has shown that ERAV is rarely isolated from clinical samples and that this has probably led to a significant underdiagnosis of ERAV infections (18). Despite this difficulty, ERAV has been isolated from throughbred horses with acute respiratory disease in Australia, Canada, the United States, Japan, and Europe and is emerging as an important problem in these regions (5, 7, 18, 21, 25, 30, 31). This work firmly establishes the potential of recombinant ERAV VP1 polypeptides to serve as diagnostic reagents and vaccines to control infections with this virus.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Kathy Davern and Michael Reed for provision of the mouse and rabbit anti-GST antibodies used in this study.

S.W. is the recipient of a Melbourne Research Scholarship and receives scholarship support from the CRC for Vaccine Technology. This work is supported in part by Racing Victoria. B.S.C. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute International Research Scholar.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baranowski E, Ruiz-Jarabo C M, Sevilla N, Andreu D, Beck E, Domingo E. Cell recognition by foot-and-mouth disease virus that lacks the RGD integrin-binding motif: flexibility in aphthovirus receptor usage. J Virol. 2000;74:1641–1647. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.4.1641-1647.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berinstein A, Roivainen M, Hovi T, Mason P W, Baxt B. Antibodies to the vitronectin receptor (integrin αvβ3) inhibit binding and infection of foot-and-mouth disease virus to cultured cells. J Virol. 1995;69:2664–2666. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2664-2666.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown F. Antibody recognition and neutralisation of foot-and-mouth disease virus. Semin Virol. 1995;6:243–248. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown F. New approaches to vaccination against foot-and-mouth disease. Vaccine. 1992;10:1022–1026. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(92)90111-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carman S, Rosendal S, Huber L, Gyles C, McKee S, Willoughby R A, Dubovi E, Thorsen J, Lein D. Infectious agents in acute respiratory disease in horses in Ontario. J Vet Diagn Investig. 1997;9:17–23. doi: 10.1177/104063879700900104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coulson B S, Londrigan S L, Lee D J. Rotavirus contains integrin ligand sequences and a disintegrin-like domain that are implicated in virus entry into cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5389–5394. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ditchfield J, Macpherson L W. The properties and classification of two new rhinoviruses recovered from horses in Toronto, Canada. Cornell Vet. 1965;55:181–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donnelly M L L, Gani D, Flint M, Monaghan S, Ryan M D. The cleavage activities of aphthovirus and cardiovirus 2A proteins. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:13–21. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fox G, Parry N R, Barnett P V, McGinn B, Rowlands D J, Brown F. The cell attachment site on foot-and-mouth disease virus includes the amino acid sequence RGD (arginine-glycine-aspartic acid) J Gen Virol. 1989;70:625–637. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-70-3-625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fry E E, Lea S M, Jackson T, Newman J W I, Ellard F M, Blakemore W E, Abu-Ghazaleh R, Samual A, King A M Q, Stuart D I. The structure and function of a foot-and-mouth disease virus–oligosaccharide receptor complex. EMBO J. 1999;18:543–554. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.3.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hartley C A, Ficorilli N, Dynon K, Drummer H E, Huang J, Studdert M J. Equine rhinitis A virus: structural proteins and immune response. J Gen Virol. 2001;82:1725–1728. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-7-1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hernandez J, Valero M L, Andreu D, Domingo E, Mateu M G. Antibody and host cell recognition of foot-and-mouth disease virus (serotype C) cleaved at the Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) motif: a structural interpretation. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:257–264. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-2-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hewat E A, Verdaguer N, Fita I, Blakemore W, Brookes S, King A, Newman J, E. D, Mateu M G, Stuart D I. Structure of the complex of an Fab fragment of a neutralizing antibody with foot-and-mouth disease virus: positioning of a highly mobile antigenic loop. EMBO J. 1997;16:1492–1500. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.7.1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hinton T M, Li F, Crabb B S. Internal ribosomal entry site-mediated translation initiation in equine rhinitis A virus: similarities to and differences from that of foot-and-mouth disease virus. J Virol. 2000;74:11708–11716. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.24.11708-11716.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackson T, Ellard F M, Ghazaleh R A, Brookes S M, Blakemore W E, Corteyn A H, Stuart D I, Newman J W, King A M. Efficient infection of cells in culture by type O foot-and-mouth disease virus requires binding to cell surface heparan sulfate. J Virol. 1996;70:5282–5287. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5282-5287.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson T J, Sheppard D, Denyer M, Blakemore W, King A M Q. The epithelial integrin αvβ6 is a receptor for foot-and-mouth disease virus. J Virol. 2000;74:4949–4956. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.11.4949-4956.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li F, Browning G F, Studdert M J, Crabb B S. Equine rhinovirus 1 is more closely related to foot-and-mouth disease virus than to other picornaviruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:990–995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.3.990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li F, Drummer H E, Ficorilli N, Studdert M J, Crabb B S. Identification of noncytopathic equine rhinovirus 1 as a cause of acute febrile respiratory disease in horses. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:937–943. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.4.937-943.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Londrigan S L, Hewish M J, Thomson M J, Sanders G M, Mustafa H, Coulson B S. Growth of rotaviruses in continuous human and monkey cell lines that vary in their expression of integrins. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:2203–2213. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-9-2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mateu M G, Martinez M A, Capucci L, Andreu D, Giralt E, Sobrino F, Brocchi E, Domingo E. A single amino acid substitution affects multiple overlapping epitopes in the major antigenic site of foot-and-mouth disease virus of serotype C. J Gen Virol. 1990;71:629–637. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-3-629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCollum W H, Timoney P J. Studies of the seroprevalence and frequency of equine rhinovirus-I and -II infection in normal horses. In: Plowright W, Rossdale P D, Wade J F, editors. Equine infectious diseases VI: Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference, 7–11 July 1991. Newmarket, United Kingdom: R & W Publications; 1992. pp. 83–87. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neff S, Sa-Carvalho D, Reider E, Mason P W, Blystone S D, Brown E J, Baxt B. Foot-and-mouth disease virus virulent for cattle utilizes the integrin αvβ3 as its receptor. J Virol. 1998;72:3587–3594. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3587-3594.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newman J, Rowlands D J, Brown F. A physico-chemical sub-grouping of the mammalian picornaviruses. J Gen Virol. 1973;18:171–180. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-18-2-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Plummer G. An equine respiratory enterovirus: some biological and physical properties. Arch Gesamt Virusforsch. 1963;12:694–700. doi: 10.1007/BF01246390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Plummer G. An equine respiratory virus with enterovirus properties. Nature. 1962;195:519–520. doi: 10.1038/195519a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pringle C R. Virus taxonomy 1997. Arch Virol. 1997;142:1727–1733. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rueckert R R. Picornaviridae: the viruses and their replication. In: Field B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 609–654. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Staatz W D, Fok K F, Zutter M M, Adams S P, Rodriguez B A, Santoro S A. Identification of a tetrapeptide recognition sequence for the α2β1 integrin in collagen. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:7363–7367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stanway G. Structure, function and evolution of picornaviruses. J Gen Virol. 1990;71:2483–2510. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-11-2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Studdert M J. Equine rhinovirus infections. In: Studdert M J, editor. Virus infections of equines. Vol. 6. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1996. pp. 213–217. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Studdert M J, Gleeson L J. Isolation and characterisation of an equine rhinovirus. Zentbl Vet Med. 1978;25:225–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.1978.tb01180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verdaguer N, Mateu M G, Andreu D, Giralt E, Domingo E, Fita I. Structure of the major antigenic loop of foot-and-mouth disease virus complexed with a neutralizing antibody: direct involvement of the Arg-Gly-Asp motif in the interaction. EMBO J. 1995;14:1690–1696. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07158.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wasserman K, Subklewe M, Pothoff G, Banik N, Schell-Frederick E. Expression of surface markers on alveolar macrophages from symptomatic patients with HIV infection as detected by flow cytometry. Chest. 1994;105:1324–1334. doi: 10.1378/chest.105.5.1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wutz G, Auer H, Nowotny N, Grosse B, Skern T, Kuechler E. Equine rhinovirus serotypes 1 and 2: relationship to each other and to aphthoviruses and cardioviruses. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:1719–1730. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-8-1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]