Abstract

We compared the immune responses to the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) envelope glycoproteins in humans and macaques with the use of clade A and clade B isogenic V3 loop glycan-possessing and -deficient viruses. We found that the presence or absence of the V3 loop glycan affects to similar extents immune recognition by a panel of anti-HIV human and anti-simian/human immunodeficiency virus (anti-SHIV) macaque sera. All sera tested neutralized the glycan-deficient viruses, in which the conserved CD4BS and CD4i epitopes are more exposed, better than the glycan-containing viruses. The titer of broadly neutralizing antibodies appears to be higher in the sera of macaques infected with glycan-deficient viruses. Collectively, our data add legitimacy to the use of SHIV-macaque models for testing the efficacy of HIV-1 Env-based immunogens. Furthermore, they suggest that antibodies to the CD4BS and CD4i sites of gp120 are prevalent in human and macaque sera and that the use of immunogens in which these conserved neutralizing epitopes are more exposed is likely to increase their immunogenicity.

The development of an effective and safe AIDS vaccine would greatly benefit from the use of nonhuman primate models to assess and compare candidate immunogens for their protective potential. In this regard, the simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-macaque system has served as a valuable model for the evaluation of various vaccine strategies and antiviral therapies against AIDS (59). Nevertheless, due to the genetic, antigenic, and immunogenic differences between the SIV and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) envelopes, the SIV system cannot be used to address directly the efficacy of HIV type 1 (HIV-1) Env-based immunogens. Towards this end, chimeric simian/human immunodeficiency viruses (SHIVs) that carry the tat, rev, and env genes of HIV-1 on the genomic backbone of the pathogenic SIVmac239 strain have been constructed (28, 31, 46). Through serial passage or in vivo adaptation, several pathogenic SHIVs have been obtained and characterized (17, 18, 20, 22, 29, 30, 46, 53). These viruses cause disease in macaques when inoculated by intravenous and mucosal routes, thus providing a system whereby the ability of HIV-1-based immunogens to protect against infection, reduce viral load, or delay progression to disease can be assessed. The relative efficacies of different vaccine designs and concepts can also be tested. Indeed, there is an increasing use of the SHIV-macaque model to evaluate different HIV-1 Env-based experimental vaccines such as envelope subunits, DNA vaccines, and various antibodies for passive immunization (3, 4, 33, 34, 51, 52, 59). However, the central question of the extent to which information obtained in the SHIV-macaque model, particularly with regard to humoral immune protection, can be extrapolated or applied to the human setting remains unclear. Limited data are available that directly compare the antigenicity (that is, ability to bind antibodies) and immunogenicity (that is, ability to elicit antibodies) of the HIV-1 envelope in humans versus nonhuman primates.

There is mounting evidence to suggest that both antibody and cellular immune responses will be required to effectively control HIV infection and spread. Antibody responses to the HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins during natural infection have been widely investigated (6, 44). These studies revealed several neutralization targets on envelope gp120, among which are the CD4 binding site (CD4BS) (7, 23, 45); the variable V1, V2, and V3 loops; a gp120 structure that is near the chemokine receptor binding site and which is better exposed following CD4 binding (CD4i epitopes) (27, 49, 50, 55, 61); and the unique 2G12 epitope (56). Antibodies to the V2 and V3 regions are mainly isolate or type specific, whereas those reacting with the discontinuous CD4BS and CD4i epitopes are broadly neutralizing (44). Longitudinal studies showed that strain-specific antibodies arise relatively early in infection (2, 24, 38, 57), while the broadly neutralizing antibodies develop later in infection (1, 8, 35, 36, 60). Although neutralization of viruses adapted to growth in T-cell lines (TCLA viruses) can be easily achieved with sera obtained from infected individuals, primary isolates are much more resistant (10, 40). The low frequency and titers with which broadly neutralizing antibodies are detected in HIV-1-infected individuals has led to the suggestion that the conserved neutralization epitopes of gp120, such as the CD4BS and CD4i sites, are poorly immunogenic.

The generation and specificity of neutralizing antibody responses to HIV-1 envelopes in monkeys infected with TCLA HIV-1-derived (SHIVHXB2 and SHIVKU) or dual-tropic primary-isolate-derived (SHIV89.6 and SHIV89.6PD) (nonpathogenic and pathogenic, respectively) SHIVs have also been evaluated. Strong neutralizing antibody responses against homologous viruses that are directed against the V1-V2 and V3 epitopes (15, 37) can be readily detected early in infection. Similar to the case for infections in humans, however, titers of neutralizing antibodies to heterologous SHIVs or primary HIV-1 isolates are generally low or undetectable and require a longer infection time to develop. In accordance, protective immunity has been demonstrated in homologous SHIVIIIB challenge experiments, while heterologous challenge with viruses expressing divergent envelope glycoproteins (SHIV89.6) still resulted in infection (51). Thus, the conserved neutralization domains of gp120 also appear to be poorly immunogenic in macaques.

With the hope of inducing protective immune responses, focus has now been directed towards designing Env-based vaccine immunogens in which the conserved functional domains of gp120 are better exposed. We recently showed that the presence of a highly conserved N-linked glycosylation site located at the N terminus of the V3 loop modifies the structure of the V3 loop and obstructs access to the highly conserved CD4 binding and CD4i sites of gp120 from diverse HIV-1 isolates (32). The use of V3 loop deglycosylated Envs as vaccine components may therefore elicit broadly cross-reactive neutralizing activity. Moreover, by assessing the degree to which the V3 loop glycan affects susceptibility of the virus to neutralization by sera from infected humans and macaques, one may gain insights into the similarities or differences in antigenic recognition of the HIV-1 envelopes by humans and macaques. Furthermore, the extent to which the conserved neutralization epitopes of gp120 are immunogenic in the two hosts could be evaluated. In the present study, the antibody responses to the HIV-1 envelope in human and nonhuman primates were compared using V3 loop glycan variants and a panel of sera collected from HIV-1-infected individuals and SHIV-infected rhesus macaques. The SHIVs carry the envelope gene of the T-cell-line-tropic, CXCR4-using (X4), and V3 loop glycan-deficient strain HIV-1SF33 or the macrophage-tropic, CCR5-using (R5), and V3 glycan-possessing isolate HIV-1SF162 (SHIVSF33 and SHIVSF162, respectively) (31). Thus, an opportunity is also provided to examine whether immunization with glycan-deficient envelopes that better expose highly conserved epitopes will elicit more potent broadly cross-neutralization antibodies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

Human osteosarcoma (HOS) cells engineered to express CD4 (T4) and the chemokine receptors CXCR4 and CCR5 (HOS T4 pBabe, HOS T4 X4, and HOS T4 R5 cells, respectively) were obtained from N. Landau (Salk Institute, La Jolla, Calif.). The cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 1 μg of puromycin per ml, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and antibiotics. 293-T cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium without puromycin.

Viruses and sera.

The construction of envelope (Env) expression vectors and the generation of single-round replication-competent luciferase reporter viruses have been previously described (11, 32). Briefly, the coding fragments of wild-type (WT) and V3 glycosylation mutant Envs were subcloned into the mammalian expression vector pCAGGS (11). The Env expression plasmids together with the HIV-1 NL-Luc-E−R− vector (14) were then cotransfected by lipofection (DMRIE-C Reagent; Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.) into 293-T cells. Cell culture supernatants were harvested at 72 h posttransfection, filtered through 0.45-μm-pore-size filters, and stored at −70°C. Viruses were quantitated by a p24gag enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, Ill.). The biologic characteristics of the viruses are listed in Table 1. The sources and gp120 ELISA titers of SHIV and HIV polyclonal sera used are listed in Table 2. The clade B human polyclonal antisera were collected from HIV-1-infected long-term nonprogressors residing in the United States. The 2743 M clade A serum is from an HIV-1-positive patient in Rwanda and was a kind gift of Linqi Zhang (Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Center, New York, N.Y.).

TABLE 1.

Viral envelope gp120 glycoproteins used

| gp120 | V3 glycana | Coreceptor useb | Clade |

|---|---|---|---|

| SF33 WT | − | X4 | B |

| SF33 V3T | + | X4 | B |

| SF162 WT | + | R5 | B |

| SF162 V3A | − | R5 | B |

| SF170 WT | + | R5 | A |

| SF170 V3A | − | R5 | A |

+ and −, presence and absence, respectively, of the N-linked glycan at amino acid 301 of envelope gp120 (numbered according to the prototype HXBc2 sequence [25]).

X4, CXCR4 using; R5, CCR5 using.

TABLE 2.

Sera used

| Serum | Sourcea | Time of collection (wpi) | Anti-gp120 ELISA end point titer |

|---|---|---|---|

| M25814 | SHIVSF33 | 4 | 1:700 |

| 8 | 1:4,000 | ||

| 24 | 1:5,500 | ||

| 32 | 1:20,000 | ||

| 53 | 1:1,000 | ||

| 96 | 1:20,000 | ||

| M26131 | SHIVSF33 | 53 | 1:320 |

| M26240 | SHIVSF33 | 53 | 1:780 |

| E239 | SHIVSF33A.2 | 53 | 1:1,050 |

| M565 | SHIVSF33A.5 | 53 | 1:1,050 |

| T528 | SHIVSF162 | 57 | 1:1,100 |

| T373 | SHIVSF162 | 79 | 1:560 |

| M26419 | SHIVSF162 | 52 | 1:560 |

| GJ | Polyclonal human clade B serum | 1:110,000 | |

| GS0 | Polyclonal human clade B serum | 1:70,000 | |

| GS21 | Polyclonal human clade B serum | 1:70,000 | |

| 2743 M | Polyclonal human clade A serum | 1:35,000 |

For SHIV sera, the virus strain is indicated; infection was by the intravenous route.

gp120 ELISA.

To measure viral envelope glycoprotein-specific antibody endpoint titers of serum samples from SHIV-infected macaques or HIV-infected individuals, 96-well Immulon plates were coated with recombinant HIV-1SF2 gp120 (kindly provided by Chiron Corp., Emeryville, Calif.). After blocking of the coated wells with 4% (wt/vol) nonfat dry milk and 10% FBS diluted in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) (25 mM Tris base, 144 mM NaCl, pH 7.5), serially diluted human or monkey serum (in TBS–FBS–milk–1% NP-40) was added to each well and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. The wells were then extensively washed with TBS and incubated with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-human immunoglobulin G (IgG) for 2 h at room temperature. The conjugate was then removed by extensive washing, the well was incubated with Dako AMPAK substrate-amplifier (Zymed Laboratories Inc., South San Francisco, Calif.) to achieve color development, and the reaction was stopped by the addition of 0.4 N sulfuric acid. Antibody reactivity to gp120 was then determined by measuring the optical density (OD) at 485 nm, using an automated plate reader. Endpoint titers are reported as the last serial dilution whose OD was three times that of normal monkey or normal human serum or as an OD of 0.1, whichever value was greater. All endpoint titers represent at least two independent experiments.

Neutralization assay.

Neutralization was performed using HOS T4 pBabe, HOS T4 X4, and HOS T4 R5 cells in 96-well plates. Briefly, cells were plated and pretreated with Polybrene (2 μg/ml; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). A 0.5- to 1.0-ng p24gag equivalent amount of each pseudotyped reporter virus was preincubated, in duplicate, with serial dilutions of sera for 1 h at 37°C and then added to cells. The infected cells were cultured for 72 h at 37°C before being lysed and tested for luciferase activity according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Promega, Madison, Wis.). Luciferase activity associated with the cell lysate was detected with an MLX microtiter plate luminometer (Dynex Technologies, Inc., Chantilly, Va.). Infection of coreceptor-bearing cells with NL4-3 virus generated in the absence of Env or infection of HOS T4 pBabe cells lacking coreceptor served as negative controls.

RESULTS

V3 loop glycan modulates the antigenicity of X4 and R5 gp120 envelope.

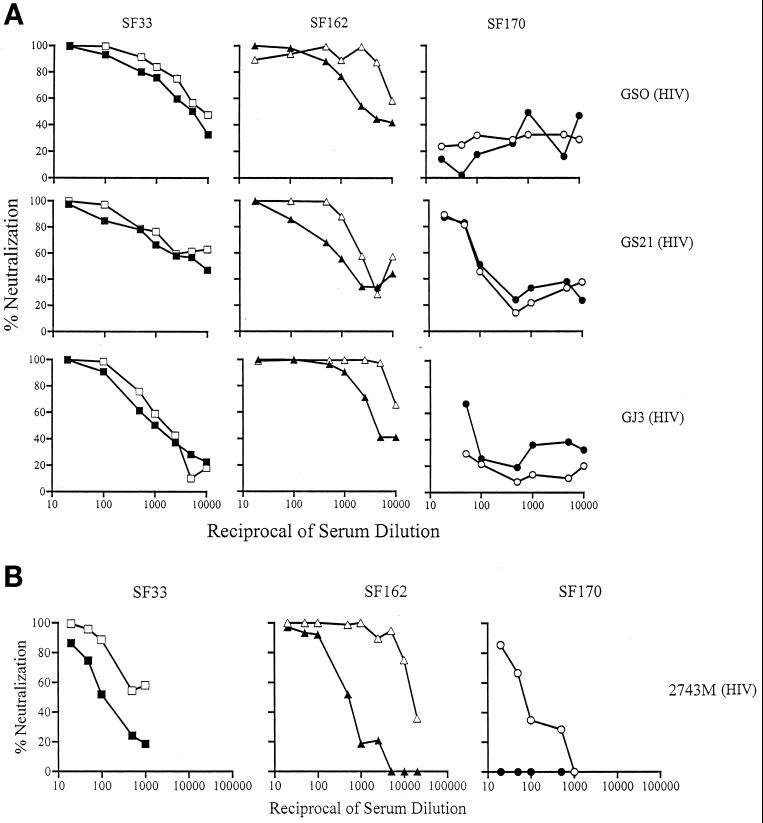

We previously reported that the lack of an N-linked glycosylation site at the N terminus of the V3 loop of SHIVSF33 (amino acid 301, numbered according to the prototype HXBc2 sequence) (25) was partially responsible for sensitivity of the virus to neutralization with a mixture of anti-HIV-1 sera (9). The presence of serum antibodies directed at the site that is exposed or modulated by the absence of the V3 loop glycan from one infected individual within the mixture, however, would have resulted in the pattern of neutralization observed. To determine the prevalence of antibodies that are directed against this cryptic epitope in infected individuals and to assess the degree to which the V3 loop glycan affects antibody recognition, the susceptibilities of reporter viruses pseudotyped with WT HIV-1SF33 and V3 mutant Env to a panel of HIV-1-positive sera were determined. The WT virus lacks the V3 loop glycan, whereas the V3 mutant virus contains the glycan moiety. To examine whether this V3 loop glycan also modulates immune recognition of primary HIV-1 viruses by sera from infected individuals, isogenic V3 loop glycan-possessing (WT) and -deficient (mutant) reporter viruses of clade B HIV-1SF162 and clade A HIV-1SF170 (Table 1) were also analyzed. The results are shown in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Neutralization of glycan-possessing and -deficient viruses by human polyclonal anti-HIV-1 sera. (A) Sera from three clade B-infected individuals. (B) Sera from a clade A-infected individual. Open and closed symbols indicate the absence and presence, respectively, of the V3 loop glycan of SF33 (squares), SF162 (triangles), and SF170 (circles) viruses. The data shown are representative of those from at least three independent experiments.

We found that the absence or presence of the V3 loop glycan on the TCLA, X4 virus HIV-1SF33 or the macrophage-tropic, R5 strain HIV-1SF162 altered their sensitivity to neutralization with the three HIV-1 clade B antisera tested (Fig. 1A). Consistently, the V3 glycan-deficient HIV-1SF33 WT and HIV-1SF162 V3A viruses were more sensitive to neutralization than their glycan-possessing counterparts. Whereas a two- to threefold difference in 90% inhibitory concentration (IC90) was observed for the HIV-1SF33 WT and the glycan-containing V3T mutant viruses, a 10- to 20-fold increase in neutralization sensitivity was seen for the glycan-deficient HIV-1SF162 V3A virus compared to the parental virus. In contrast, the HIV-1SF170 WT and V3 glycan-lacking viruses were relatively resistant to neutralization with the sera tested. Only serum GS21 achieved 90% neutralization at a 1:20 dilution, with no difference in titer for the glycan-possessing or -deficient viruses. Interestingly, the glycan-possessing R5 primary clade B HIV-1SF162 appeared to be more sensitive to neutralization than the glycan-possessing TCLA, X4 variant HIV-1SF33 V3T. Perhaps this reflects a similarity in the gp120 antigenic structures of primary viruses that establish infection in vivo.

To examine whether genotypic variation underscores the inability of clade B sera to neutralize the HIV-1SF170 viruses, neutralization with a clade A anti-HIV-1 antiserum (2743 M) was performed (Fig. 1B). A pattern similar to that of neutralization with clade B anti-HIV antisera was observed, with the V3 glycan-deficient HIV-1SF33 WT and HIV-1SF162 V3A mutant viruses being more susceptible to neutralization with the 2743 M serum than their corresponding V3 glycan-containing viruses. Again, a greater difference between the neutralization susceptibilities of the clade B primary HIV-1SF162 WT and V3A mutant viruses compared to the HIV-1SF33 glycan-possessing and -lacking viruses was observed, with the V3 loop glycan-deficient HIV-1SF162 V3A virus being significantly more sensitive (IC90, ≈1:10,000). Weak neutralization of the clade A V3 glycan-deficient HIV-1SF170 V3A virus (IC50, 1:80) was achieved, but the glycan-possessing WT virus was resistant. Thus, the antienvelope response in this particular clade A serum appears to be similar to that of the clade B sera.

Immune responses to HIV-1 gp120 are comparable in humans and macaques.

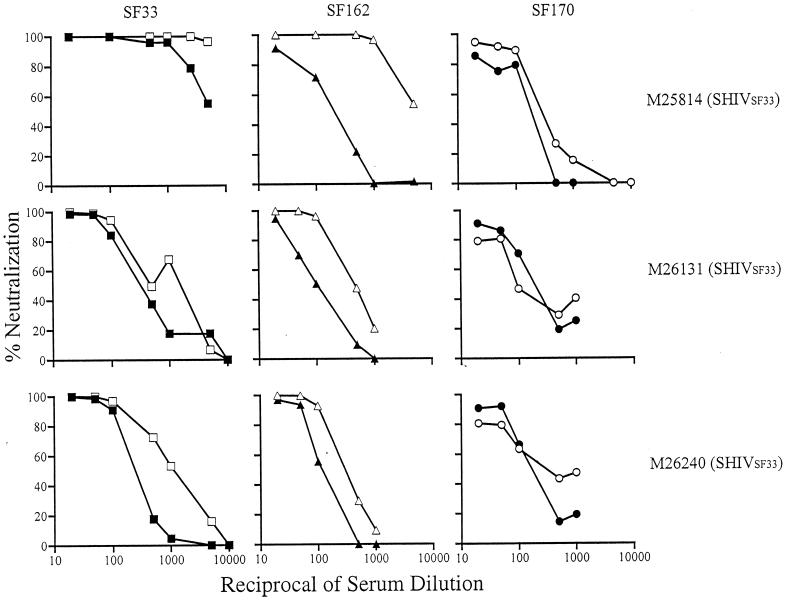

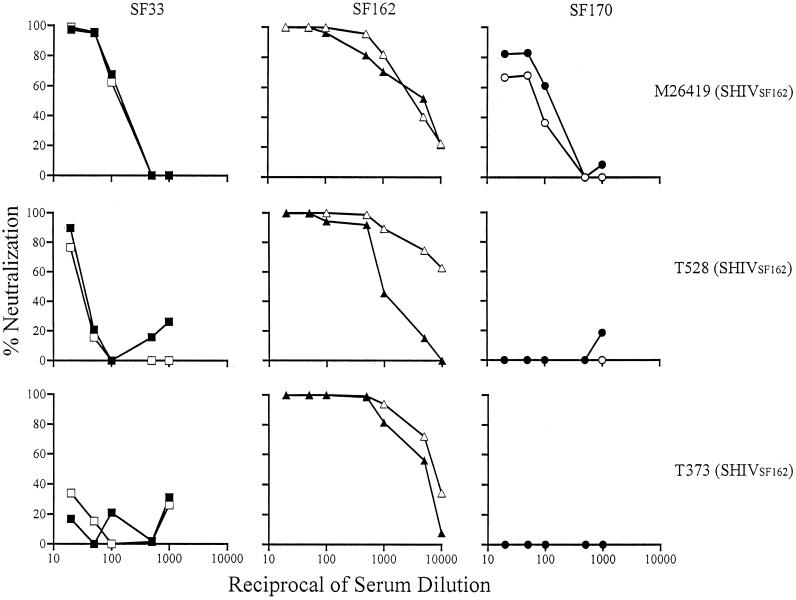

The findings with the human antisera indicated that the presence or absence of V3 loop glycan influenced the antigenicity of envelope gp120. To assess whether macaques recognize the HIV-1 gp120 Env to the same extent as humans, the ability of sera from SHIVSF33- and SHIVSF162-infected animals to neutralize the corresponding WT and V3 glycan mutant viruses was examined. The results are presented in Fig. 2 and 3. High titers of homologous neutralization antibodies were observed, again with the presence or absence of the V3 loop glycan modulating the degree of neutralization sensitivity of the viruses. For HIVSF33, the V3 glycan-lacking WT virus is two- to threefold more susceptible to neutralization than the V3 glycan-possessing V3T virus (Fig. 2). Sera from macaque M25814 exhibited the highest anti-gp120 ELISA titer (Table 2) and the greatest neutralization titer. Since the WT virus is the autologous virus for SHIVSF33 sera and the V3 loop glycan has been shown to modulate the structure of the V3 loop of HIV-1SF33 (32), the modest difference in neutralization susceptibility between the WT and V3T viruses could be attributed to the presence of neutralizing antibodies directed against the V3 loop. However, the data generated with the SHIVSF162 sera suggest otherwise. For these sera, the autologous glycan-containing WT virus was found to be two- to threefold more resistant to neutralization than the V3 glycan-deficient V3A mutant virus (Fig. 3). Thus, antibodies other than those directed against the V3 loop are involved in mediating virus neutralization. Collectively, these findings indicate that the immune responses to Env gp120 in macaques are similar to those in humans regardless of whether the immunizing virus is glycan containing or glycan deficient.

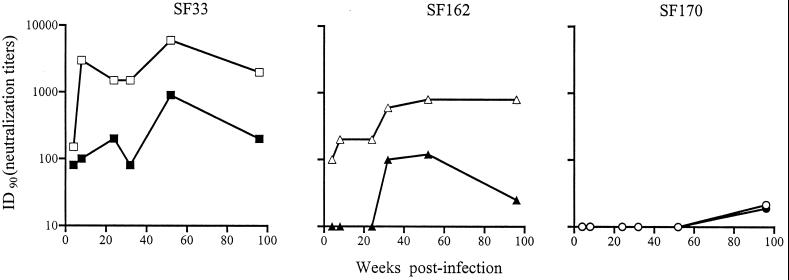

FIG. 2.

Sera from macaques infected with SHIVSF33 show broadly neutralizing activity. Neutralization of autologous and heterologous viruses by serial dilutions of sera from SHIVSF33-infected animals M25814 (week 96), M26131 (week 53), and M26240 (week 53) is presented. Open and closed symbols indicate the absence and presence, respectively, of the V3 loop glycan of autologous SF33 (squares) and heterologous SF162 (triangles) and SF170 (circles) viruses. The neutralization profiles shown are representative of those from at least three independent experiments.

FIG. 3.

High autologous but limited heterologous neutralizing antibody titers in sera from macaques infected with SHIVSF162. Sera from M26419 (week 52), T528 (week 57), and M373 (week 79) were tested for their neutralizing activity in single-round infection assays as described in the text. Open and closed symbols indicate the absence and presence, respectively, of the V3 loop glycan of autologous SF162 (triangles) and heterologous SF33 (squares) and SF170 (circles) viruses. Results are representative of those from at least three independent experiments.

Conserved neutralization epitopes of HIV-1 gp120 are immunogenic in humans and macaques.

We recently showed that the V3 loop glycan served to block access to major conserved neutralizing epitopes, namely, the CD4BS and CD4i sites, of gp120 of both HIV-1SF33 and HIV-1SF162, as well as to CD4BS of HIV-1SF170 (32). Viruses that lack the V3 loop glycan are more susceptible to neutralization by anti-CD4BS and anti-CD4i monoclonal antibodies (summarized in Table 3). Antibodies, in particular those directed against CD4BS, are broadly cross-neutralizing. The similar increase in susceptibilities to neutralization of the V3 glycan-deficient HIV-1SF33 WT and HIV-1SF162 V3A mutant viruses, compared to their V3 glycan-possessing counterparts, by the four heterologous human anti-HIV sera (GJ, GSO, GS21, and 2743 M) (Table 2) raises the possibility that the conserved CD4BS and CD4i epitopes are immunogenic in infected humans. To determine whether these conserved epitopes are also immunogenic in macaques, the ability of SHIVSF33 and SHIVSF162 sera to neutralize heterologous viruses that contain or lack the V3 loop glycan was determined (Fig. 2 and 3). Since broadly cross-reactive antibodies typically arise later in the course of natural infection (5, 38, 43), sera from macaques that have been infected for over 1 year were used. We found that the SHIVSF33 sera exhibited the broadest cross-neutralization (Fig. 2). All three SHIVSF33 sera tested achieved 90% neutralization of heterologous isolates, with the degree of cross-neutralization of each SHIVSF33 serum correlating with its anti-gp120 ELISA titer. Serum from macaque M25814 had the highest anti-gp120 ELISA titer (1:20,000) (Table 2) and the strongest cross-neutralization potential. An IC90 of 1:2,000 against the V3 glycan-deficient HIVSF162 V3A and an IC90 of 1:40 against the HIV-1SF162 WT was observed (Fig. 2). More importantly, this serum also neutralized the clade A HIV-1SF170 WT and its corresponding V3A virus at an IC90 of 1:50. Sera M26131 and M26240, which exhibited anti-gp120 ELISA titers of 1:320 and 1:780, respectively, cross-neutralized HIV-1SF162 V3A at 1:200 and the WT virus at 1:40. These sera also weakly neutralized the clade A HIV-1SF170 Env-based viruses (IC90 of 1:20 to 1:50). In contrast, the SHIVSF162 sera tested did not display significant cross-neutralizing titers even though their anti-gp120 ELISA titers are comparable to or even slightly higher than those of the SHIVSF33 M26131 and M26420 sera (Fig. 3 and Table 2). Only weak neutralizing activity was exhibited against both the HIV-1SF33 WT and V3T viruses by SHIVSF162 sera M26419 and T528 (IC90 of 1:20 to 1:50), but the HIV-1SF170 viruses were resistant.

TABLE 3.

Relative susceptibilities of WT and V3 glycan mutant viruses to neutralization with IgG CD4, anti-CD4BS, and anti-CD4i monoclonal antibodies

| Virus | Neutralizationa by:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgG CD4 | CD4BS monoclonal antibody:

|

CD4i monoclonal antibody:

|

|||

| IgG1 b12 | F105 | 17b | 48d | ||

| SF33 WT | ++ | ++ | − | ++ | + |

| SF33 V3T | ++ | + | − | + | ± |

| SF162 WT | ++ | + | − | − | − |

| SF162 V3A | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| SF170 WT | − | − | − | − | − |

| SF170 V3A | ± | ± | − | − | − |

The extent of neutralization of V3 glycan-possessing and -deficient viruses by 5 μg of each monoclonal antibody per ml was determined as reported previously (32). ++, >90% neutralization; +, 50 to 90% neutralization; ±, 20 to 50% neutralization; −, <20% neutralization.

Increased exposure of conserved neutralization epitopes enhances their immunogenicity.

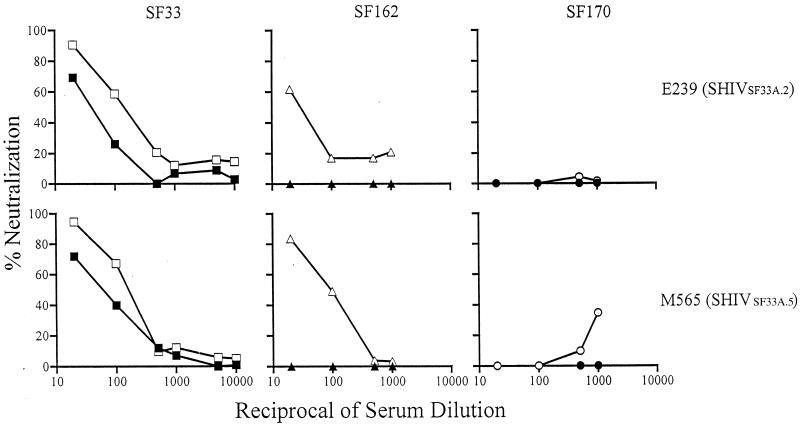

Masking of the conserved neutralization epitopes by gp120 variable loops and carbohydrate moieties has been suggested to be partly responsible for their poor immunogenicity (62). The finding that sera from animals infected with viruses in which the conserved neutralization epitopes are more accessible (i.e., SHIVSF33) exhibit substantial titers of cross-neutralizing antibodies suggests that increased exposure of these epitopes improves their immunogenicity. To build on this observation, the ability of SHIVSF33 sera to neutralize a panel of HIV-1 Env pseudotyped viruses was examined. Furthermore, sera from animals infected with molecular clones of the neutralization-resistant pathogenic variant SHIVSF33A, designated SHIVSF33A.2 and SHIVSF33A.5, were examined for their cross-neutralizing potential. The Env gp120s of SHIVSF33 and pathogenic clones differed by over 25 amino acids, among which are glycosylation modifications in the V1, V2, and V3 domains (19).

We found that the M25814 SHIVSF33 sera achieved 90% neutralization against viruses pseudotyped with TCLA, X4, or X4 R5 HIV-1 (HXB2, HIV-1SF2, HIV-1SF13, and HIV-1SF665) as well as primary R5 HIV-1 (JRFL and ADA) Envs at serum dilutions of 1:20 to 1:50 (data not shown). No significant difference in neutralizing titers was observed for the X4 and R5 viruses, consistent with targeting of conserved functional epitopes of envelope glycoproteins. In contrast, sera from SHIVSF33A.2- and SHIVSF33A.5-infected animals displayed weak neutralizing titers, even against viruses that lack the V3 loop glycan (Fig. 4). Ninety percent neutralization was achieved only for the HIV-1SF33 Env-based viruses, with the V3 glycan-deficient WT virus being more sensitive (IC90 of 1:20 to 1:50). The lack of potent neutralization of the V3 glycan-deficient virus HIV-1SF162 V3T by SHIVSF33A.2 and SHIVSF33A.5 sera contrasts with the profile seen for neutralization by anti-HIV-1 human sera (Fig. 1). Determination of whether this reflects a difference in the antigenic structure of the X4, neutralization-resistant SF33A envelope and primary R5 envelopes that include HIV-1SF162 or the impact of a pathogenic infection on the host immune response requires further investigation.

FIG. 4.

Restricted neutralization of viruses by sera from two macaques infected with molecular clones derived from the pathogenic variant SHIVSF33A. Open and closed symbols indicate the absence and presence, respectively, of the V3 loop glycan of SF33 (squares), SF162 (triangles), and SF170 (circles) viruses. The patterns shown are representative of those from at least three independent experiments.

Broadly cross-reactive neutralization antibodies are detected early in a SHIVSF33- infected macaque.

It has been reported that compared to type-specific antibodies, a longer period of time is required for cross-neutralization antibodies to develop in infected humans and macaques (5, 38, 43). To investigate whether infection with a virus in which the conserved neutralization epitopes are more exposed shortens the time for antibodies directed against these sites to be developed, the cross-neutralization titers of sera collected from SHIVSF33-infected macaque M25814 at 4, 8, 24, 32, 53, and 96 weeks postinfection (wpi) were determined. The results are summarized in Fig. 5. An overall increase in both homologous and heterologous neutralizing antibody titers over time in M25814 was observed, with serum collected at 96 wpi displaying the most potent cross-reactive neutralization titers (achieving 90% neutralization of the HIV-1SF170 Env-based viruses at serum dilutions of 1:20 to 1:50). For the clade B viruses, neutralization antibodies against both homologous HIV-1SF33 WT and V3A viruses could be detected in serum collected as early as 4 wpi, with titers against the glycan-deficient WT virus being higher than those against the glycan-possessing mutant virus. Neutralization against the heterologous glycan-lacking HIV-1SF162 V3T virus could also be detected with week 4 M25814 serum, but the glycan-containing HIV-1SF162 WT virus was resistant. The latter virus was neutralized by sera collected from M25814 only after 32 wpi, with no significant increase in cross-neutralizing titers developing in this animal thereafter. These data suggest that antibodies directed against CD4BS and CD4i are present as early as 4 wpi in this SHIVSF33-infected animal but that neutralization against glycan-possessing heterologous viruses requires a longer time to develop, perhaps reflecting the time required for such antibodies to mature and gain significant avidity (12, 13, 38, 48).

FIG. 5.

Autologous and heterologous neutralizing titers of sera from SHIVSF33-infected macaque M25814 collected over the time course of infection. Sera collected at 0, 4, 24, 32, 53, and 96 wpi were used. The serum dilution giving 90% neutralization (ID90) of infection by autologous SF33 (squares) and heterologous SF162 (triangles) and SF170 (circles) viruses is shown. Open and closed symbols indicate the absence and presence, respectively, of the V3 loop glycan. The data are representative of those from at least three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we aimed to compare the immune responses to the HIV-1 envelope in humans and macaques by assessing the ability of HIV-1 and SHIV antisera to neutralize isogenic V3 loop glycan-possessing and -deficient viruses. This approach stems from our recent observation that the highly conserved N-linked glycan located at the N terminus of the V3 loop modulates the structure of the V3 loop, as well as blocking access to the conserved functional CD4BS and CD4i sites of gp120 (32). We reason that a similarity in the degree to which human and macaque antibodies recognize the V3 loop envelope variants would be indicative of a similarity in antigenic recognition of the HIV-1 envelope by the two hosts. Furthermore, an increase in the ability of heterologous HIV-1 and SHIV sera to neutralize viruses that lack the V3 loop glycan would be interpreted as neutralization mediated by antibodies directed at the CD4BS and CD4i sites present in these sera. Our findings that the presence or absence of the V3 loop glycan affects, to similar extents, recognition of the virus by polyclonal HIV and SHIV antisera illustrate that the ability of the macaque immune system to recognize HIV-1 gp120 is comparable to that of humans. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that data on the relative efficacies of HIV-1 Env-based vaccines generated in the SHIV-macaque model will be applicable to the human setting. Furthermore, the observations that the V3 loop glycan-deficient viruses are consistently more sensitive to neutralization by polyclonal human anti-HIV sera and sera from animals infected with viruses that have the glycan (i.e., SHIVSF162 and SHIVSF33A) indicate that the CD4BS and CD4i epitopes shielded by the V3 glycan are immunogenic in humans and in macaques.

An increase, compared to their glycan-containing counterparts, in susceptibility to neutralization of the clade B V3 loop glycan-deficient viruses, independent of coreceptor usage, by HIV sera is observed. A modest (two- to threefold) degree of difference in neutralization susceptibility is observed for the clade B TCLA, X4 HIV-1SF33 WT versus the V3T viruses, but a more dramatic difference (10- to 20-fold) is noted for the primary clade B, R5 HIV-1SF162 WT versus the V3A viruses (Fig. 1). This is true for neutralization with both clade B and clade A sera. Although broadly neutralizing anti-V3 antibodies have been described (16, 42), they are few in number. Cross-neutralization by sera from infected individuals, therefore, is attributed principally to antibodies against conserved conformational CD4BS and CD4i epitopes (41, 58, 63). We previously observed (32), and have summarized in Table 3, that the absence of the V3 loop glycan on HIV-1SF162 Env conferred greater susceptibility to neutralization with monoclonal antibodies directed against these sites than for HIV-1SF33 Env when compared to their glycan-possessing counterparts. In other words, the conserved neutralizing epitopes are better exposed in the absence of the V3 loop glycan on HIV-1SF162 than on HIV-1SF33. The difference in the degree of neutralization susceptibility of HIV-1SF33 and HIV-1SF33 V3T compared to the HIV-1SF162 and HIV-1SF162 V3A viruses with HIV sera noted here correlates with the extent to which the V3 loop glycan affects the exposure of the CD4BS and CD4i sites on HIV-1SF33 and HIV-1SF162. The finding that both the clade A glycan-possessing HIV-1SF170 and its V3 glycan-deficient variant are relatively resistant to neutralization with HIV-1 sera is also consistent with the rank order of the extent of CD4BS and CD4i epitope exposure. Neither of these viruses is very susceptible to neutralization with CD4BS and CD4i site antibodies (Table 3) (32). Collectively, our data are in agreement with previous findings (21, 54) and indicate that the conserved neutralizing epitopes are seen by the immune system in spite of their cryptic nature and that antibodies directed against these sites are prevalent in HIV-1-infected individuals.

The conserved gp120 neutralizing epitopes are also immunogenic in macaques. Similar to infection with HIV-1 in humans, infection with SHIV can be envisioned as immunization with different forms of HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins. We found that the presence or absence of the V3 loop glycan affected recognition of the virus by heterologous SHIV sera to the same extent as by human sera. That is, there is little difference in neutralization susceptibility of HIV-1SF33 compared to its glycan-containing variant V3T, as opposed to the more dramatic 10- to 20-fold difference in neutralization susceptibilities of HIV-1SF162 WT and V3A viruses. Thus, although it is generally believed that conserved neutralization epitopes of gp120 are poorly immunogenic, our findings suggest otherwise. High titers of neutralizing antibodies directed against the CD4BS and CD4i epitopes can be induced during natural infection of humans and macaques. The lack of neutralization or poor neutralization of primary isolates by HIV and SHIV sera therefore is a consequence of the many ways, including masking by glycosylation, by which the virus can escape immune recognition rather than of the lack of neutralizing antibodies. In this regard, it is interesting that all SHIVSF33 sera, regardless of their gp120 ELISA titers, neutralized the heterologous HIV-1SF162 WT at 1:40 but displayed different neutralization titers against the glycan-deficient HIV-1SF162 V3A virus (IC90 of 1:2,000 for M25814 serum versus 1:200 for the 26240 and 26131 sera) (Fig. 2). This implies that a 10-fold increase in neutralization titers against the conserved epitopes is still insufficient to overcome the block to access to these sites on the glycan-containing virus.

Of the macaque sera tested, only sera from SHIVSF33-infected animals exhibited broad neutralizing activity. The inability of the SHIVSF162 sera to potently inhibit replication of the TCLA X4 SHIVSF33 WT and V3T viruses (Fig. 3) contrasts with the ability seen for polyclonal HIV-1 sera (Fig. 1), raising the possibility that broadly cross-neutralizing antibodies may not be as prevalent in infected macaques as in humans. Nevertheless, it is important to recognize that the anti-gp120 ELISA titers of SHIVSF162 sera are significantly lower than those of the HIV-1 sera tested (Table 2) and that the human sera were collected from individuals who have been infected for much longer periods of time (over 6 years). A comparison of the neutralizing ability of sera from recently seroconverted individuals to that of the SHIVSF162 sera will be required to more fully compare the prevalences of antibodies directed against the conserved neutralizing sites in humans and macaques.

Despite the fact that sera from only a small number of infected animals were examined, a picture emerges in which chimeric virus containing the envelope of the TCLA, X4 HIV-1SF33 strain is able to elicit more potent cross-neutralizing antibodies than that containing envelopes of primary-like viruses (i.e., SHIVSF162 and molecular clones of SHIVSF33A). This finding is unlikely to be due to differences in the amounts of SHIVSF33, SHIVSF162, and SHIVSF33A antigens produced during infection, since pathogenic SHIVSF33A replicated to higher levels than SHIVSF33 and SHIVSF162 (data not shown) and yet was unable to elicit broadly cross-reactive antibodies. Montefiori et al. have also reported that monkeys infected with TCLA SHIVHXB2, but not those infected with the primary isolate-derived dual-tropic SHIV89.6 and SHIV89.6PD, developed heterologous neutralizing antibody (37). It has been suggested that the gp120 conformation of TCLA viruses is biased towards an “open” state in which there is less masking of epitopes, including CD4BS and CD4i, for neutralizing antibodies (26, 32, 39, 62). This could account for the presence of higher titers of cross-neutralizing antibodies in monkeys infected with TCLA SHIVs. Nevertheless, we argue that increased exposure of conserved neutralizing epitopes on SHIVSF33 Env gp120 as a result of the absence of the V3 loop glycan and/or other envelope modifications further contributes to its enhanced immunogenicity. Our finding that the broadly cross-reactive neutralization antibodies in SHIVSF33-infected macaques can be detected much earlier (Fig. 5) and are of greater potency than has been previously reported for HIV-1-infected patients and for SHIVHXB2-infected animals supports this argument. Indeed, macaques infected with variants of SIVmac239 mutated to lack N-linked carbohydrates in and around the V1 and V2 loops have been reported to generate antibodies that neutralize the fully glycosylated parent virus better than homologous sera (47). To directly address the effect of carbohydrate on the immunogenicity of HIV-1 envelope gp120 in infected macaques independent of other factors such as replication rates and cytopathicity, however, studies with site-directed glycan-deficient nonreplicating immunogens (e.g., SF33 V3T envelopes) will be required.

In summary, our findings suggest that the targets for neutralizing antibodies to HIV-1 envelopes raised in humans and macaques are similar and that conserved neutralization epitopes of HIV-1 Env gp120 are immunogenic in both hosts. Furthermore, our data support the use of modified envelope glycoproteins, such as the V3 deglycosylated form represented by SHIVSF33 Env gp120, in which conserved epitopes are more exposed, as immunogens in various vaccine designs and strategies. The challenge, however, will lie in generating antibodies with sufficient titers and potency that are able to access the cryptic neutralization epitopes on primary isolates.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grants CA72822 and AI41945.

We thank Lisa Chakrabarti, Allen Mayer, and Janet M. Harouse for their comments and Wendy Chen for help with the graphics.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arendrup M, Sonnerborg A, Svennerholm B, Akerblom L, Nielsen C, Clausen H, Olofsson S, Nielsen J O, Hansen J E. Neutralizing antibody response during human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection: type and group specificity and viral escape. J Gen Virol. 1993;74:855–863. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-5-855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ariyoshi K, Harwood E, Chiengsong-Popov R, Weber J. Is clearance of HIV-1 viraemia at seroconversion mediated by neutralising antibodies? Lancet. 1992;340:1257–1258. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92953-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baba T W, Liska V, Hofmann-Lehmann R, Vlasak J, Xu W, Ayehunie S, Cavacini L A, Posner M R, Katinger H, Stiegler G, Bernacky B J, Rizvi T A, Schmidt R, Hill L R, Keeling M E, Lu Y, Wright J E, Chou T C, Ruprecht R M. Human neutralizing monoclonal antibodies of the IgG1 subtype protect against mucosal simian-human immunodeficiency virus infection. Nat Med. 2000;6:200–206. doi: 10.1038/72309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barouch D H, Santra S, Schmitz J E, Kuroda M J, Fu T M, Wagner W, Bilska M, Craiu A, Zheng X X, Krivulka G R, Beaudry K, Lifton M A, Nickerson C E, Trigona W L, Punt K, Freed D C, Guan L, Dubey S, Casimiro D, Simon A, Davies M E, Chastain M, Strom T B, Gelman R S, Montefiori D C, Lewis M G. Control of viremia and prevention of clinical AIDS in rhesus monkeys by cytokine-augmented DNA vaccination. Science. 2000;290:486–492. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5491.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berkower I, Smith G E, Giri C, Murphy D. Human immunodeficiency virus 1. Predominance of a group-specific neutralizing epitope that persists despite genetic variation. J Exp Med. 1989;170:1681–1695. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.5.1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burton D R, Montefiori D C. The antibody response in HIV-1 infection. AIDS. 1997;11:S87–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burton D R, Pyati J, Koduri R, Sharp S J, Thornton G B, Parren P W, Sawyer L S, Hendry R M, Dunlop N, Nara P L, et al. Efficient neutralization of primary isolates of HIV-1 by a recombinant human monoclonal antibody. Science. 1994;266:1024–1027. doi: 10.1126/science.7973652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cao Y, Qin L, Zhang L, Safrit J, Ho D D. Virologic and immunologic characterization of long-term survivors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:201–208. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199501263320401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng-Mayer C, Brown A, Harouse J, Luciw P A, Mayer A J. Selection for neutralization resistance of the simian/human immunodeficiency virus SHIVSF33A variant in vivo by virtue of sequence changes in the extracellular envelope glycoprotein that modify N-linked glycosylation. J Virol. 1999;73:5294–5300. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5294-5300.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng-Mayer C, Homsy J, Evans L A, Levy J A. Identification of human immunodeficiency virus subtypes with distinct patterns of sensitivity to serum neutralization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2815–2819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng-Mayer C, Liu R, Landau N R, Stamatatos L. Macrophage tropism of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and utilization of the CC-CKR5 coreceptor. J Virol. 1997;71:1657–1661. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.1657-1661.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cole K S, Murphey-Corb M, Narayan O, Joag S V, Shaw G M, Montelaro R C. Common themes of antibody maturation to simian immunodeficiency virus, simian-human immunodeficiency virus, and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infections. J Virol. 1998;72:7852–7859. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.7852-7859.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cole K S, Rowles J L, Jagerski B A, Murphey-Corb M, Unangst T, Clements J E, Robinson J, Wyand M S, Desrosiers R C, Montelaro R C. Evolution of envelope-specific antibody responses in monkeys experimentally infected or immunized with simian immunodeficiency virus and its association with the development of protective immunity. J Virol. 1997;71:5069–5079. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5069-5079.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Connor R I, Chen B K, Choe S, Landau N R. Vpr is required for efficient replication of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 in mononuclear phagocytes. Virology. 1995;206:935–944. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Etemad-Moghadam B, Karlsson G B, Halloran M, Sun Y, Schenten D, Fernandes M, Letvin N L, Sodroski J. Characterization of simian-human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein epitopes recognized by neutralizing antibodies from infected monkeys. J Virol. 1998;72:8437–8445. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.8437-8445.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gorny M K, Conley A J, Karwowska S, Buchbinder A, Xu J Y, Emini E A, Koenig S, Zolla-Pazner S. Neutralization of diverse human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants by an anti-V3 human monoclonal antibody. J Virol. 1992;66:7538–7542. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.12.7538-7542.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harouse J M, Gettie A, Eshetu T, Tan R C H, Bohm R, Blanchard J, Baskin G, Cheng-Mayer C. Mucosal transmission and induction of simian AIDS by CCR5-specific simian/human immunodeficiency virus (SF163P3) J Virol. 2001;75:1990–1995. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.4.1990-1995.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harouse J M, Gettie A, Tan R C, Blanchard J, Cheng-Mayer C. Distinct pathogenic sequela in rhesus macaques infected with CCR5 or CXCR4 utilizing SHIVs. Science. 1999;284:816–819. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harouse J M, Gettie A, Tan R C H, Eshetu T, Ratterree M, Blanchard J, Cheng-Mayer C. Pathogenic determinants of the mucosally transmissible CXCR4-specific SHIVSF33A2 map to ENV region. J AIDS. 2001;27:222–228. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200107010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harouse J M, Tan R C, Gettie A, Dailey P, Marx P A, Luciw P A, Cheng-Mayer C. Mucosal transmission of pathogenic CXCR4-utilizing SHIVSF33A variants in rhesus macaques. Virology. 1998;248:95–107. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoffman T L, LaBranche C C, Zhang W, Canziani G, Robinson J, Chaiken I, Hoxie J A, Doms R W. Stable exposure of the coreceptor-binding site in a CD4-independent HIV-1 envelope protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6359–6364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joag S V, Li Z, Foresman L, Stephens E B, Zhao L J, Adany I, Pinson D M, McClure H M, Narayan O. Chimeric simian/human immunodeficiency virus that causes progressive loss of CD4+ T cells and AIDS in pig-tailed macaques. J Virol. 1996;70:3189–3197. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.3189-3197.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kang C Y, Hariharan K, Posner M R, Nara P. Identification of a new neutralizing epitope conformationally affected by the attachment of CD4 to gp120. J Immunol. 1993;151:449–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kenealy W R, Matthews T J, Ganfield M C, Langlois A J, Waselefsky D M, Petteway S R., Jr Antibodies from human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals bind to a short amino acid sequence that elicits neutralizing antibodies in animals. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1989;5:173–182. doi: 10.1089/aid.1989.5.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Korber B, Foley B, Kuiken C, Pillai S, Sodroski J. Numbering positions in HIV relative to HXB2, p. IV-27–IV-35. In: Korber B, Brander C, Haynes B, Koup R, Moore J, Walker B, editors. Human retroviruses and AIDS 1998. Los Alamos, N.Mex: Los Alamos National Laboratory; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kozak S L, Platt E J, Madani N, Ferro F E, Jr, Peden K, Kabat D. CD4, CXCR-4, and CCR-5 dependencies for infections by primary patient and laboratory-adapted isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1997;71:873–882. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.873-882.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwong P D, Wyatt R, Robinson J, Sweet R W, Sodroski J, Hendrickson W A. Structure of an HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein in complex with the CD4 receptor and a neutralizing human antibody. Nature. 1998;393:648–659. doi: 10.1038/31405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li J, Lord C I, Haseltine W, Letvin N L, Sodroski J. Infection of cynomolgus monkeys with a chimeric HIV-1/SIVmac virus that expresses the HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1992;5:639–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu Y, Pauza C D, Lu X, Montefiori D C, Miller C J. Rhesus macaques that become systemically infected with pathogenic SHIV 89.6-PD after intravenous, rectal, or vaginal inoculation and fail to make an antiviral antibody response rapidly develop AIDS. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1998;19:6–18. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199809010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luciw P A, Mandell C P, Himathongkham S, Li J, Low T A, Schmidt K A, Shaw K E, Cheng-Mayer C. Fatal immunopathogenesis by SIV/HIV-1 (SHIV) containing a variant form of the HIV-1SF33 env gene in juvenile and newborn rhesus macaques. Virology. 1999;263:112–127. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luciw P A, Pratt-Lowe E, Shaw K E, Levy J A, Cheng-Mayer C. Persistent infection of rhesus macaques with T-cell-line-tropic and macrophage-tropic clones of simian/human immunodeficiency viruses (SHIV) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7490–7494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malenbaum S E, Yang D, Cavacini L, Posner M, Robinson J, Cheng-Mayer C. The N-terminal V3 loop glycan modulates the interaction of clade A and B human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelopes with CD4 and chemokine receptors. J Virol. 2000;74:11008–11016. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.23.11008-11016.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mascola J R, Lewis M G, Stiegler G, Harris D, VanCott T C, Hayes D, Louder M K, Brown C R, Sapan C V, Frankel S S, Lu Y, Robb M L, Katinger H, Birx D L. Protection of macaques against pathogenic simian/human immunodeficiency virus 89.6PD by passive transfer of neutralizing antibodies. J Virol. 1999;73:4009–4018. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.4009-4018.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mascola J R, Stiegler G, VanCott T C, Katinger H, Carpenter C B, Hanson C E, Beary H, Hayes D, Frankel S S, Birx D L, Lewis M G. Protection of macaques against vaginal transmission of a pathogenic HIV-1/SIV chimeric virus by passive infusion of neutralizing antibodies. Nat Med. 2000;6:207–210. doi: 10.1038/72318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McKnight A, Clapham P R, Goudsmit J, Cheingsong-Popov R, Weber J N, Weiss R A. Development of HIV-1 group-specific neutralizing antibodies after seroconversion. AIDS. 1992;6:799–802. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199208000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Montefiori D C, Pantaleo G, Fink L M, Zhou J T, Zhou J Y, Bilska M, Miralles G D, Fauci A S. Neutralizing and infection-enhancing antibody responses to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in long-term nonprogressors. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:60–67. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Montefiori D C, Reimann K A, Wyand M S, Manson K, Lewis M G, Collman R G, Sodroski J G, Bolognesi D P, Letvin N L. Neutralizing antibodies in sera from macaques infected with chimeric simian-human immunodeficiency virus containing the envelope glycoproteins of either a laboratory-adapted variant or a primary isolate of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1998;72:3427–3431. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.3427-3431.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moog C, Fleury H J, Pellegrin I, Kirn A, Aubertin A M. Autologous and heterologous neutralizing antibody responses following initial seroconversion in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected individuals. J Virol. 1997;71:3734–3741. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.3734-3741.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moore J P. HIV vaccines. Back to primary school. Nature. 1995;376:115. doi: 10.1038/376115a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moore J P, Cao Y, Qing L, Sattentau Q J, Pyati J, Koduri R, Robinson J, Barbas C F, 3rd, Burton D R, Ho D D. Primary isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 are relatively resistant to neutralization by monoclonal antibodies to gp120, and their neutralization is not predicted by studies with monomeric gp120. J Virol. 1995;69:101–109. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.1.101-109.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moore J P, Ho D D. Antibodies to discontinuous or conformationally sensitive epitopes on the gp120 glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 are highly prevalent in sera of infected humans. J Virol. 1993;67:863–875. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.2.863-875.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moore J P, Trkola A, Korber B, Boots L J, Kessler J A, 2nd, McCutchan F E, Mascola J, Ho D D, Robinson J, Conley A J. A human monoclonal antibody to a complex epitope in the V3 region of gp120 of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 has broad reactivity within and outside clade B. J Virol. 1995;69:122–130. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.1.122-130.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nara P L, Robey W G, Pyle S W, Hatch W C, Dunlop N M, Bess J W, Jr, Kelliher J C, Arthur L O, Fischinger P J. Purified envelope glycoproteins from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants induce individual, type-specific neutralizing antibodies. J Virol. 1988;62:2622–2628. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.8.2622-2628.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parren P W, Moore J P, Burton D R, Sattentau Q J. The neutralizing antibody response to HIV-1: viral evasion and escape from humoral immunity. AIDS. 1999;13:S137–S162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Posner M R, Hideshima T, Cannon T, Mukherjee M, Mayer K H, Byrn R A. An IgG human monoclonal antibody that reacts with HIV-1/GP120, inhibits virus binding to cells, and neutralizes infection. J Immunol. 1991;146:4325–4332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reimann K A, Li J T, Veazey R, Halloran M, Park I W, Karlsson G B, Sodroski J, Letvin N L. A chimeric simian/human immunodeficiency virus expressing a primary patient human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate env causes an AIDS-like disease after in vivo passage in rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 1996;70:6922–6928. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.6922-6928.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reitter J N, Means R E, Desrosiers R C. A role for carbohydrates in immune evasion in AIDS. Nat Med. 1998;4:679–684. doi: 10.1038/nm0698-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Richmond J F, Lu S, Santoro J C, Weng J, Hu S L, Montefiori D C, Robinson H L. Studies of the neutralizing activity and avidity of anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Env antibody elicited by DNA priming and protein boosting. J Virol. 1998;72:9092–9100. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.9092-9100.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rizzuto C, Sodroski J. Fine definition of a conserved CCR5-binding region on the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 glycoprotein 120. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2000;16:741–749. doi: 10.1089/088922200308747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rizzuto C D, Wyatt R, Hernandez-Ramos N, Sun Y, Kwong P D, Hendrickson W A, Sodroski J. A conserved HIV gp120 glycoprotein structure involved in chemokine receptor binding. Science. 1998;280:1949–1953. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Robinson H L, Montefiori D C, Johnson R P, Manson K H, Kalish M L, Lifson J D, Rizvi T A, Lu S, Hu S L, Mazzara G P, Panicali D L, Herndon J G, Glickman R, Candido M A, Lydy S L, Wyand M S, McClure H M. Neutralizing antibody-independent containment of immunodeficiency virus challenges by DNA priming and recombinant pox virus booster immunizations. Nat Med. 1999;5:526–534. doi: 10.1038/8406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shibata R, Igarashi T, Haigwood N, Buckler-White A, Ogert R, Ross W, Willey R, Cho M W, Martin M A. Neutralizing antibody directed against the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein can completely block HIV-1/SIV chimeric virus infections of macaque monkeys. Nat Med. 1999;5:204–210. doi: 10.1038/5568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shibata R, Maldarelli F, Siemon C, Matano T, Parta M, Miller G, Fredrickson T, Martin M A. Infection and pathogenicity of chimeric simian-human immunodeficiency viruses in macaques: determinants of high virus loads and CD4 cell killing. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:362–373. doi: 10.1086/514053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stamatatos L, Cheng-Mayer C. An envelope modification that renders a primary, neutralization-resistant clade B human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate highly susceptible to neutralization by sera from other clades. J Virol. 1998;72:7840–7845. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.7840-7845.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thali M, Moore J P, Furman C, Charles M, Ho D D, Robinson J, Sodroski J. Characterization of conserved human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 neutralization epitopes exposed upon gp120-CD4 binding. J Virol. 1993;67:3978–3988. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.3978-3988.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Trkola A, Purtscher M, Muster T, Ballaun C, Buchacher A, Sullivan N, Srinivasan K, Sodroski J, Moore J P, Katinger H. Human monoclonal antibody 2G12 defines a distinctive neutralization epitope on the gp120 glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1996;70:1100–1108. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1100-1108.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tsang M L, Evans L A, McQueen P, Hurren L, Byrne C, Penny R, Tindall B, Cooper D A. Neutralizing antibodies against sequential autologous human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates after seroconversion. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:1141–1147. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.5.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.VanCott T C, Bethke F R, Burke D S, Redfield R R, Birx D L. Lack of induction of antibodies specific for conserved, discontinuous epitopes of HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein by candidate AIDS vaccines. J Immunol. 1995;155:4100–4110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Warren J T, Levinson M A. AIDS preclinical vaccine development: biennial survey of HIV, SIV, and SHIV challenge studies in vaccinated nonhuman primates. J Med Primatol. 1999;28:249–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.1999.tb00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wrin T, Crawford L, Sawyer L, Weber P, Sheppard H W, Hanson C V. Neutralizing antibody responses to autologous and heterologous isolates of human immunodeficiency virus. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1994;7:211–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wyatt R, Kwong P D, Desjardins E, Sweet R W, Robinson J, Hendrickson W A, Sodroski J G. The antigenic structure of the HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein. Nature. 1998;393:705–711. doi: 10.1038/31514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wyatt R, Sodroski J. The HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins: fusogens, antigens, and immunogens. Science. 1998;280:1884–1888. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang P F, Chen X, Fu D W, Margolick J B, Quinnan G V., Jr Primary virus envelope cross-reactivity of the broadening neutralizing antibody response during early chronic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol. 1999;73:5225–5230. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.6.5225-5230.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]