Abstract

Transcription from human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV16) P670, a promoter in the E7 open reading frame, is repressed in undifferentiated keratinocytes but becomes activated upon differentiation. We showed that the transient luciferase expression driven by P670 was markedly enhanced in HeLa cells cotransfected with an expression plasmid for human Skn-1a (hSkn-1a), a transcription factor specific to differentiating keratinocytes. The hSkn-1a POU domain alone, which mediates sequence-specific DNA binding, was sufficient to activate the expression of luciferase. Electrophoretic mobility shift assay revealed the presence of two binding sites, sites 1 and 2, upstream of P670, which were shared by hSkn-1a and YY1. Site 1 bound more strongly to hSkn-1a than site 2 did. YY1 complexing with a short DNA fragment having site 1 was displaced by hSkn-1a, indicating that hSkn-1a's affinity with site 1 was stronger than YY1's. Disrupting the binding sites by nucleotide substitutions raised the basal expression level of luciferase and decreased the enhancing effect of hSkn-1a. In HeLa cells transfected with circular HPV16 DNA along with the expression plasmid for hSkn-1a, the transcript from P670 was detectable, which indicates that the results obtained with the reporter plasmids are likely to have mimicked the regulation of P670 in authentic HPV16 DNA. The data strongly suggest that the transcription from P670 is repressed primarily by YY1 binding to the two sites, and the displacement of YY1 by hSkn-1a releases P670 from the repression.

Human papillomaviruses (HPVs), a group of small icosahedral viruses with circular 8-kb DNA, have a strong epithelial tropism (57). To date more than 80 HPV genotypes have been identified and classified on the basis of their pathogenicity and target tissues. HPVs that infect the cutaneous epithelium, such as types 1, 2, 4, and 8, mainly cause skin warts. HPVs that infect the mucosal epithelium, such as types 6 and 11, cause benign condyloma, but types 16, 18, 31, and 33 cause cervical cancer (35, 58). All HPVs have overall similarity in genomic organization; the early region encoding the nonstructural viral proteins (E1 through E7 proteins), the late region encoding the two capsid proteins (L1 and L2 proteins), and the noncoding regulatory region (long control region [LCR]) between the L1 and E6 genes (57).

HPVs that infect basal cells of the epithelium through microlesions are known to express their genes in such a way as to be tightly linked to the differentiation state of the host cells (34). The differentiation-dependent viral transcription has been studied mainly in immortalized human keratinocytes harboring HPV16 (15, 18, 29) or HPV31 (7, 25, 37). In undifferentiated cells the promoter in the LCR, such as HPV16 P97 or HPV31 P97, is active and directs transcription of E6, E7, and some other early genes, but the promoter in the E7 open reading frame (ORF), such as HPV16 P670 or HPV31 P742, is suppressed (18, 25, 38). Differentiation of the host cells induces a dramatic increase of transcriptional activities of P670 and P742, resulting in expression of E1 and its downstream late genes (18, 21, 25, 31, 38, 45). Recently, the promoter in the HPV6 E7 ORF has been shown to be negatively regulated by CCAAT displacement protein (CDP) (2) and YY1, a multifunctional protein acting as a transcriptional activator or repressor (1). CDP and YY1 bind directly to the upstream region of the promoter in undifferentiated cells (1, 2). However, the detailed regulatory mechanism for the promoters in the HPV E7 ORF has yet to be fully elucidated.

A number of transcription factors that regulate cell differentiation have been found and grouped as the POU domain family (46). The POU domain is a DNA-binding domain originally identified in mammalian proteins Pit-1 (8, 27), Oct-1 (50), and Oct-2 (10) and in Caenorhabditis elegans protein unc-86 (13). Pit-1, Oct-2, and unc-86 induce terminal differentiation of pituitary cells, B lymphocytes, and neuronal cells, respectively. Skn-1a (4) (also referred to as Epoc-1 [56] or Oct-11 [17]), a member of the POU domain family, is primarily expressed in differentiating suprabasal keratinocytes but not in proliferating basal cells and plays important regulatory roles in both epidermal development and keratinocyte differentiation (5). Also, Skn-1a activates keratin 10 (4) and small proline-rich protein (14) genes and downregulates involucrin (52) and profilaggrin (28) genes through direct binding to their promoter regions, considered a trigger for epithelial differentiation (5). Murine Skn-1 and the recently isolated human Skn-1a (hSkn-1a) (22) have been shown to enhance transcription from promoters in the LCR of HPV types 1a, 16, and 18 (3, 22, 55).

In this study we have focused on the possible involvement of hSkn-1a in regulation of HPV16 P670 and found that hSkn-1a activated expression of the luciferase gene driven by P670, probably through direct binding to the promoter region in a sequence-specific manner. The binding sites were shared with YY1, and disruption of the sites raised the basal level of luciferase. YY1 in the YY1-DNA complex was displaced by hSkn-1a, strongly suggesting that the primary repression of P670 by YY1 is abrogated by replacement of YY1 with hSkn-1a, which is expressed only in the differentiating keratinocytes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of expression plasmids for hSkn-1a.

The hSkn-1a cDNA in a human placenta cDNA library (Takara, Osaka, Japan) was amplified by PCR (advantage2 PCR kit; Clontech) using the sense primer (5′-AGG ATG GTG AAT CTG GAG TCC ATG CAC) and the antisense primer (5′-GTC TAC GTG GAG GTA GGT GGA ATG ATT). The DNA fragment was cloned into pGEM-T easy vector (Promega) to generate pGEM-T/hSkn–1a. The nucleotide sequence of the obtained cDNA was identical to that of the previously reported hSkn-1a cDNA (22). The DNA fragment encoding hSkn-1a was excised from pGEM-T/hSkn–1a by digestion with EcoRI, end blunted, and inserted into the pCMV4 expression plasmid (6) at the SmaI site, generating pCMV/hSkn–1a. The EcoRI fragment was also inserted in frame into pHM6 (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) at the EcoRI site to generate pHM/hSkn–1a, which expresses the N-terminal hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged hSkn-1a protein. The expression plasmid for Skn-1a with an N-terminal 187-amino-acid deletion (dN) was constructed by digestion of pHM/hSkn–1a with XhoI and self ligation. The DNA fragments encoding hSkn-1a with a C-terminal 92-amino-acid deletion (dC), both N- and C-terminal deletions (dN/dC), or POU domain deletion (dPOU) were synthesized by PCR (advantage-HF PCR kit; Clontech) using pGEM-T/hSkn–1a as a template. The sense primers were 5′-CGG AAT TCG ATG GTG AAT CTG GAG TCC for dC, 5′-CGG AAT TCC CTC GAG GAG CTG GAG AAG for dN/dC, and 5′-CGG AAT TCG ATG GTG AAT CTG GAG TCC for dPOU. The antisense primers were 5′-CGG AAT TCA GGC CAC AGG GCA GTT GAT for dC and dN/dC and 5′-CGG AAT TCA GTC ACT GGG CTC ATC GGC for dPOU. The primers were designed to have EcoRI sites at their 5′ ends. The DNA fragments obtained by PCR were digested with EcoRI and inserted into pHM6 at the EcoRI site.

Construction of luciferase reporter plasmids.

Construction of pLCR-Luc, which expresses the firefly luciferase gene under control of the HPV16 LCR, was described previously (33). To monitor transcription from P670, p670-Luc was constructed by insertion of the DNA fragment carrying the luciferase gene in the place of the E1 gene. Luciferase DNA, which was synthesized by PCR using primers having NcoI sites at their 5′ ends and digested with NcoI, was inserted at the NcoI site of the HPV16 PstI-B fragment in the pUC/LCR (33), pUC19 containing the 1776-bp PstI-B fragment. In the resultant plasmid, p670-Luc, an HPV16 DNA fragment from nucleotides (nt) 7010 through 7906 and from nt 1 to 864 was fused with the luciferase DNA at the first ATG codon of the E1 gene. Nucleotide substitutions were introduced into the TATA motif in the LCR or into the binding sites for hSkn-1a in pLCR-Luc or p670-Luc by using a Mutan-Super Express Km site-directed mutagenesis kit (Takara). The synthetic oligonucleotide used to abolish the TATA motif was 5′-AAA TGT CTG CTT TGA TGC TAA CCG GTT TC, and those to abrogate binding with hSkn-1a were 5′-CAG CTG TAA TCA AGG ACG GAG ATA CAC CTA (for binding site 1) and 5′-GAT ACA CCT ACA TAG GAC GAA TAT ATG TTA (for binding site 2). Nucleotides different from those of authentic sequences are underlined.

Cell culture and luciferase assays.

HeLa S3 cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. In standard cotransfection assays, a mixture containing 200 ng of luciferase reporter plasmids, 200 ng of expression plasmids for hSkn-1a (or the backbone plasmid pCMV4), and 0.5 ng of a control plasmid containing the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter-driven Renilla luciferase was transfected into 40% confluent cells per well of a 24-well plate using the Effectene transfection reagent (Qiagen). At 48 h after transfection, luciferase activities of cellular extracts were measured by using the PicaGene Dual SeaPansy Luminescence Kit (Toyo Ink Co., Tokyo, Japan) and a microplate luminometer LB96V (Perkin Elmer Applied Biosystems). Efficiency of transfection was normalized using Renilla luciferase activity.

Immunoblotting.

HeLa cells in a 10-cm-diameter dish were transfected with 2 μg of expression plasmids for hSkn-1a. Forty-eight hours later cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), resuspended in a sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) sample buffer, boiled for 5 min, and then subjected to SDS–12.5% PAGE. The resolved proteins were transferred electrophoretically onto Hybond-P membranes (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden). The membranes were incubated with anti-Skn-1a antibody (Santa Cruz) (1:1,000) or anti-HA antibody (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) (1:10,000) in TBST (20 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20) containing 5% (wt/vol) skim milk for 1 h at room temperature, washed four times with TBST, incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse antibody in TBST containing 5% skim milk for 1 h at room temperature, and then washed with TBST four times. Immunoreactive proteins were visualized by the ECL plus chemiluminescence detection system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Preparation of recombinant proteins.

The hSkn-1a protein fused with glutathione S-transferase (GST–hSkn-1a) and the DNA-binding domain of human YY1 protein (amino acids 293 to 414) fused with GST (GST-ΔYY1) (24) were bacterially produced. The EcoRI fragment isolated from pGEM–T/hSkn–1a was inserted in frame into the EcoRI site of pGEX-4T-3 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) to produce pGEX–4T–3/hSkn–1a. The DNA fragment encoding the YY1 DNA-binding domain was synthesized by PCR with a sense primer (5′-CGG AAT TCC AAG AAC AAT AGC TTG CCC), an antisense primer (5′-CGG AAT TCA CTG GTT GTT TTT GGC CTT), and a HeLa cell cDNA library. The PCR product was digested with EcoRI and cloned in frame into pGEX-2TK at the EcoRI site to produce pGEX–2TK/ΔYY1. pGEX–4T–3/hSkn–1a and pGEX–2TK/ΔYY1 were introduced into Escherichia coli strains BL21(DE3) plysS and JM109, respectively. The fusion proteins were purified by GSTrap affinity-column chromatography (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) with AKTAprime (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA).

A mixture containing double-stranded 32P-labeled oligonucleotides (0.4 pmol), either 1 μg of purified fusion proteins or 10 μg of total extracts from HeLa cells, 1 μg of poly(dI-dC) in a final volume of 10 μl of a buffer consisting of 20 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and 2 μg of aprotinin/ml was incubated at room temperature for 30 min. For supershift, anti-YY1 mouse monoclonal antibody (SC-7341; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, Calif.) (4 μg) was added to the reaction mixture. The sample was then loaded on a 5% polyacrylamide gel and electrophoresed in 0.5× Tris-borate–EDTA buffer at 4°C. Gels were dried and visualized by autoradiography on X-ray films.

The sequences of double-stranded oligonucleotides are as follows: A (nt 501 to 530), 5′-CCGGTCGATGTATGTCTTGTTGCAGATCAT; B (nt 531 to 560), 5′-CAAGAACACGTAGAGAAACCCAGCTGTAAT; C (nt 551 to 580), 5′-CAGCTGTAATCATGCATGGAGATACACCTA; D (nt 561 to 590), 5′-CAT GCATGGAGATACACCTACATTGCATGA; E (nt 571 to 600), 5′-GATA CACCTACATTGCATGAATATATGTTA; F (nt 581 to 610), 5′-CATTGCAT GAATATATGTTAGATTTGCAAC; G (nt 591 to 620), 5′-ATATATGTTA GATTTGCAACCAGAGACAAC; H (nt 611 to 640), 5′-CAGAGACAACT GATCTCTACTGTTATGAGC; I (nt 641 to 670), 5′-AATTAAATGACAGCTCAGAGGAGGAGGATG; mC, 5′-CAGCTGTAATCAAGGACGGAGATACACCTA; mE, 5′-GATACACCTACATAGGACGAATATATGTTA; mG, 5′-ATATATGTTAGATTAGGACCCAGAGACAAC; 7721-7750, 5′-TAACTAACCTAATTGCATATTTGGCATAAG; m7721-7750, 5′-TAACTAACCTAATAGGACATTTGGCATAAG; YY1-wt, 5′-CGCTCCGCGGCCATCTTGGCGGCTGGT; YY1-mut, 5′-CGCTCCGCGATTATCTTGGCGGCTGGT. Numbers in parentheses indicate nucleotide numbers of the HPV16 genome (from the HPV Sequence Database of Los Alamos National Laboratory), and nucleotides used for substitution mutations are underlined.

Cellular extracts for EMSAs detecting complexes of hSkn-1a and the probes were prepared using HeLa cells (2 × 106) transfected with 2 μg of expression plasmids for hSkn-1a. At 48 h after transfection the cells were washed with PBS twice and resuspended in an extraction buffer consisting of 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 420 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 5 mM MgCl2, 2% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 0.5 mM PMSF, and 2 μg of aprotinin/ml, followed by freeze-thaw five times. The supernatant obtained by a centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C was used for EMSAs.

HeLa cell extracts used for EMSAs detecting complexes of cellular YY1 and the probes were prepared as follows. The extracts from HeLa cells were obtained by freeze-thaw in the extraction buffer and centrifugation as described above. Then the supernatant was dialyzed against the extraction buffer lacking KCl for 4 h at 4°C and again centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C to remove precipitates formed during dialysis.

Detection of HPV transcripts by 5′ RACE and Southern blotting.

The HPV16 genome, excised from pHPV16K (30) by digestion with BamHI and purified by extraction from an agarose gel after electrophoresis, was self ligated at concentrations of 50 ng/μl to avoid the formation of multimers. Using the Effectene transfection reagent, HeLa cells (106 cells) were transfected with the circular HPV16 DNA (2 μg) with pCMV4 (2 μg) or pCMV/hSkn–1a (2 μg). At 48 h after transfection, mRNAs were extracted by using the QuickPrep mRNA Purification Kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), followed by cDNA synthesis with the Marathon cDNA library kit (Clontech). cDNAs specific to HPV16 in the libraries were amplified by 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) (advantage2 PCR kit; Clontech) using 5′ RACE adapter sense primer and antisense primer I (5′-ATC ATG TAT AGT TGT TTG CAG CTC TGT G, nt 178 to 151 of HPV16) or antisense primer II (5′-CAC TAC AGC CTC TAC ATA AAA CC, nt 939 to 917). PCR consisted of 5 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 5 s and annealing/extension at 72°C for 2 min, 5 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 5 s and annealing/extension at 70°C for 2 min, and 25 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 5 s and annealing/extension at 68°C for 2 min. The PCR products were electrophoresed in a 0.7% agarose gel, transferred to Hybond-XL membranes (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), and probed with 32P-labeled oligonucleotides derived from HPV16 DNA, nt 7005 to 868 (the PstI fragment) or nt 628 to 868 (synthesized by PCR). Prehybridization and hybridization were done at 60°C for 1 h in ExpressHyb hybridization solution (Clontech) followed by washes in 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)–0.05% SDS at room temperature and in 0.1× SSC–0.1% SDS at 50°C. The 5′ RACE products were directly cloned into pGEM-T easy, and the clones containing HPV16 sequences were selected by standard colony hybridization with the probe of 32P-labeled oligonucleotide derived from HPV16 nt 628 to 868. The cDNAs were sequenced with an ABI310 sequencer (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems).

RESULTS

Activation of P670 promoter by hSkn-1a.

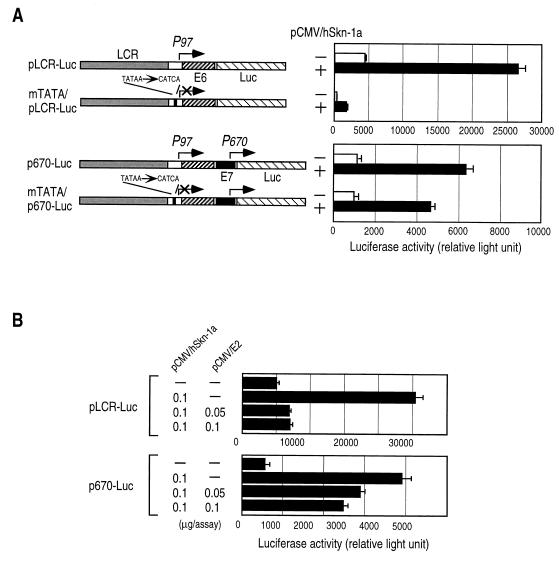

To examine expression from P670, which drives E1 and late genes in HPV16 (18, 31), we constructed expression plasmids p670-Luc and, for comparison, pLCR-Luc (Fig. 1A). Plasmids pLCR-Luc and p670-Luc had a luciferase gene as a reporter in place of the E7 gene driven by P97 and the E1 gene, respectively. For measurement of enhancing effects of hSkn-1a, HeLa cells were transfected with pLCR-Luc or p670-Luc together with the expression plasmid for hSkn-1a (pCMV/hSkn–1a) or its backbone plasmid, pCMV4. hSkn-1a expressed in HeLa cells transfected with pCMV/hSkn–1a or pHM/hSkn–1a was detected by immunoblotting using anti-hSkn-1a antibody, but endogenous hSkn-1a was undetectable in mock-transfected HeLa cells (data not shown). Forty-eight hours later, the luciferase activity was measured with the cellular lysates (Fig. 1A). As reported previously with murine Skn-1a (3, 55), hSkn-1a markedly enhanced luciferase expression from P97 in pLCR-Luc. The luciferase expression with p670-Luc, although less efficiently than with pLCR-Luc, was also enhanced by hSkn-1a. It seems likely, from the following observations, that the expression of luciferase with p670-Luc, which contained the promoters P97 and P670 (Fig. 1A), was mainly directed by P670.

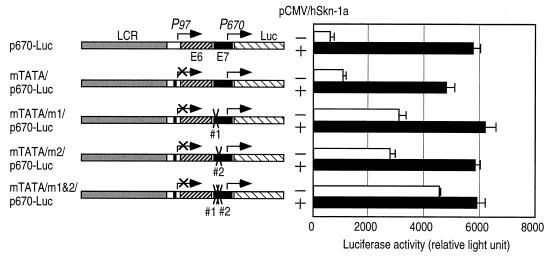

FIG. 1.

Activation of HPV16 P670 by hSkn-1a. (A) Structures of the reporter plasmids are schematically illustrated on the left. HeLa cells were cotransfected with 0.2 μg of the luciferase reporter plasmids and 0.2 μg of pCMV4 or pCMV/hSkn–1a. Luciferase activities of cell extracts were measured at 48 h after transfection. Results are presented as means ± standard deviations of three independent experiments. (B) Effects of HPV16 E2 expression on the hSkn-1a-mediated activation of P670. HeLa cells were cotransfected with pCMV/hSkn–1a (1 μg), pLCR-Luc (0.2 μg) or p670-Luc (0.2 μg), and increasing amounts of pCMV/E2 (a gift from Peter M. Howley). Luciferase activities of cell extracts were measured at 48 h after transfection. Results are presented as means ± standard deviations of three independent experiments.

Disruption of the TATA motif for P97 almost abolished the luciferase expression with plasmid mTATA/pLCR–Luc but did not greatly affect the expression with mTATA/p670–Luc, which lacked the TATA motif for P97 but retained P670 intact (Fig. 1A). With or without P97, the enhancing effects of hSkn-1a were comparable on the expression of luciferase in the position of the E1 gene in the construct of p670-Luc (Fig. 1A). It is expected from the HPV transcription studies (9, 25, 39, 40, 43, 49) that luciferase is not efficiently translated from mRNA transcribed from P97 in p670-Luc, because E6 and/or E7 ORFs are polycistronically present upstream of the luciferase ORF. Furthermore, although the hSkn-1a-mediated enhancement of the luciferase expression with pLCR-Luc was interfered with by HPV16 E2 protein, which negatively regulates P97 (11, 23, 32, 41), the luciferase expression from p670-Luc was enhanced by hSkn-1a in the presence of E2 (Fig. 1B).

Similar results were obtained in experiments using pHM/hSkn–1a expressing N-terminal HA-tagged hSkn-1a or in experiments using HaCat cells, a human cell line of spontaneously immortalized keratinocytes negative for HPVs (data not shown).

The POU domain of hSkn-1a capable of activating P670.

The POU domain, which acts as a DNA-binding motif and determines its binding specificity to target sequences (20), was sufficient to activate P670. Plasmids were constructed for expression of N-terminal HA-tagged hSkn-1a (pHM/hSkn–1a) and its family of truncated proteins; the one with deletion of the N-terminal domain (pHM/dN), the one with deletion of the C-terminal domain (pHM/dC), the one with deletion of both domains (pHM/dNdC), and the one with deletion of the POU domain (pHM/dPOU) (Fig. 2A). Expression of the truncated proteins in HeLa cells transfected with these plasmids was shown by immunoblotting with anti-HA antibody (Fig. 2B). Capabilities of truncated hSkn-1a to activate transcription from P670 were examined by measuring luciferase activities of lysate obtained from HeLa cells transfected with p670-Luc together with each of the pHM plasmids (Fig. 2C). The results showed that, like a full-size hSkn-1a, the POU domain alone (dN/dC) seems to be capable of transactivating P670. The hSkn-1a lacking the POU domain did not transactivate P670. Apparently, it remains to be investigated how the other domains, the C-terminal primary transactivation domain (22) and the N-terminal domain, which has been reported to exhibit either inhibitory or stimulatory effects on the transactivation by hSkn-1a (22), affect the activation of P670.

FIG. 2.

hSkn-1a domains capable of transactivating P670. (A) Schematic representation of N-terminal HA-tagged truncated hSkn-1a expressed by pHM6 vector. (B) Immunoblotting detection of the truncated hSkn-1a in total extracts from HeLa cells transfected with pHM6 (a backbone plasmid) or expression plasmids for HA-tagged hSkn-1a with or without deletion. (C) Activation of P670 by the truncated hSkn-1a. HeLa cells were cotransfected with p670-Luc (0.2 μg) and 0.2 μg of the expression plasmids for HA-tagged hSkn-1a with or without deletion. Luciferase activities of cell extracts were measured at 48 h after transfection. Results are presented as means ± standard deviations of three independent experiments.

Binding of hSkn-1a to the upstream region of P670.

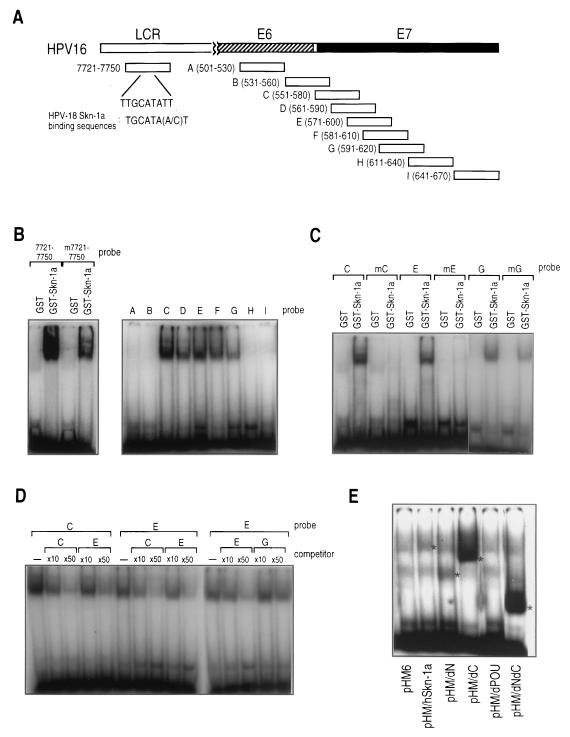

EMSAs showed that bacterially expressed and purified hSkn-1a fused with glutathione S-transferase (GST–hSkn-1a) bound to the synthetic double-stranded oligonucleotide probe having the sequence of HPV16 nt 7721 to 7750 (Fig. 3A and B). The nucleotide sequence from nt 7733 to 7738, TTGCAT, is similar to the previously described core sequence of mouse Skn-1a-binding sites in HPV18 LCR, TGCAT(A/C)T (55). Substitutions of A for T (nt 7733), G for C (nt 7735), and C for T (nt 7737) reduced binding of hSkn-1a with the probe. The results strongly suggest that hSkn-1a specifically binds to the HPV16 LCR sequence, which is similar to the mouse Skn-1a-binding site in HPV18 LCR (55).

FIG. 3.

Binding of hSkn-1a with synthetic oligonucleotides having partial sequences of the HPV16 E7 ORF. (A) Probes A through I used for EMSAs have nucleotide sequences of the regions schematically presented as rectangles. Numbers in parentheses indicate nucleotide numbers in HPV16 DNA (from the HPV Sequence Database of the Los Alamos National Laboratory). (B) EMSA detecting the complex of GST–Skn-1a with the 32P-labeled HPV16 probe. The DNA-protein complex was electrophoresed on a 5% polyacrylamide gel and visualized by autoradiography. (C) EMSA detecting the complex of GST–Skn-1a with the 32P-labeled probes having mutations in the putative hSkn-1a binding sites. TGCA(A/T) in probes C, E, and G were replaced with AGGAC to generate probes mC, mE, and mG, respectively. (D) Cross-competition in an EMSA. Complex formed GST–hSkn-1a, and a mixture of 32P-labeled probes (0.4 pmol) and 4 pmol (×10) or 20 pmol (×50) of unlabeled competitors was electrophoresed on a 5% polyacrylamide gel and visualized by autoradiography. (E) EMSA detecting the complex of Skn-1a expressed in HeLa cells and probe E. Total extracts from HeLa cells transfected with the expression plasmids for HA-tagged hSkn-1a with or without deletion was allowed to form a complex with 32P-labeled probe E.

Direct binding of hSkn-1a to the upstream region of P670 was strongly suggested by EMSAs. GST–hSkn-1a was mixed with the radiolabeled probes having nucleotide sequences of the regions designated A to I (Fig. 3A), and complex formation of GST–hSkn-1a with each probe was detected by mobility shift (Fig. 3B). GST–hSkn-1a bound with probes C to G, suggesting that at least two hSkn-1a-binding sites were located within the region from nt 551 to 620. Since hSkn-1a did not form complex with probes A, B, H, and I, the binding of hSkn-1a with the probes was shown to be sequence specific. Boiling GST–hSkn-1a for 5 min completely abolished the binding to the probes (data not shown), suggesting that conformational integrity of hSkn-1a is required for its DNA binding. Moreover, GST–hSkn-1a did not bind any synthetic single-stranded oligonucleotides used to generate the probes by annealing (data not shown).

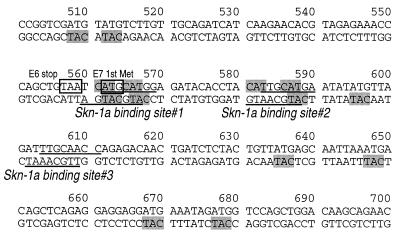

Consistent with the mobility shift data (Fig. 3B), the sequences of probes C to G were found to contain motifs similar to those found in the HPV18 or HPV16 LCR (TTGCAT). Three imperfect palindromes composed of two octamer-like sequences, (A/T)TGCA(A/T)XX, were located at nt 560 to 569 (site 1), at nt 581 to 590 (site 2), and at nt 602 to 611 (site 3) (Fig. 4). To test whether these motifs in the probes are actually involved in binding with hSkn-1a, they were subjected to substitution mutation.

FIG. 4.

Nucleotide sequence upstream of P670. The putative hSkn-1a binding sites 1, 2, and 3 are underlined. Boxed in gray is CAT, which may serve as a core of YY1-binding sites. The sequence is from the Los Alamos National Laboratory database.

Nucleotide substitutions of AGGAC for TGCA(A/T) were introduced into the putative hSkn-1a binding sites in the probes of C, E, and G to produce mutated probes mC, mE, and mG, respectively, which were tested for binding with GST–hSkn-1a and then examined by EMSA (Fig. 3C). Probes mC and mE totally lost their capability of complexing with hSkn-1a, indicating that the sequences of sites 1 and 2 were essential for probes C and E, respectively, to bind with hSkn-1a. However, mG bound to hSkn-1a with a reduced level, indicating that the binding of hSkn-1a to probe G was not specific to the nucleotide sequence of site 3. Thus, it was concluded that hSkn-1a appears to bind to the upstream region of P670 at sites 1 and 2 in a sequence-specific manner.

The relative binding affinity of hSkn-1a with the three sites was examined by cross competition using probes C, E, and G in EMSA (Fig. 3D). The binding of GST–hSkn-1a with the radiolabeled C and E probes was clearly competed by excess homologous cold competitors added to the reaction mixtures. Formation of the hSkn–1a/C complex was partly disrupted by addition of the excess E probe. Formation of hSkn–1a/E complex was disrupted by the addition of the excess C probe but not by the excess G probe. Thus, site 1 in probe C had the strongest hSkn-1a-binding affinity, followed by site 2 in probe E and then site 3 in probe G. Because of its low sequence specificity and weak binding affinity, site 3 was not analyzed further.

Like bacterially expressed GST–hSkn-1a, hSkn-1a expressed in eukaryotic cells was found to bind to probe E. Total lysates of HeLa cells transfected with pHM/hSkn–1a, pHM/dN, pHM/dC, pHM/dPOU, and pHM/dNdC expression plasmids for N-terminal HA-tagged hSkn-1a, HA-tagged hSkn-1a with deletion of N-terminal domain, HA-tagged hSkn-1a with deletion of C-terminal domain, HA-tagged hSkn-1a with deletion of POU domain, and HA-tagged hSkn-1a with deletions of both N- and C-terminal domains, respectively, were mixed with the 32P-labeled E probe, and complex formation was examined (Fig. 3E). All of the proteins having the POU domain showed the capability of binding to the probe and showed that the protein lacking the POU domain lost the capability, indicating that the binding was mediated by the POU domain. Full-length hSkn-1a transiently expressed in HeLa cells was also found to bind to radiolabeled probes C and G (data not shown).

Binding of YY1 to the upstream region of P670.

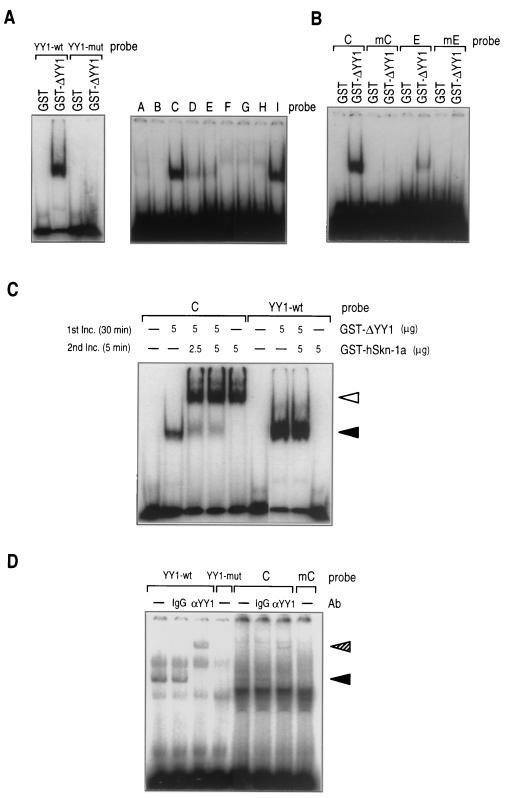

YY1, a potential transcriptional repressor, was examined for its ability to bind to the upstream region of HPV16 P670, because a recent study of HPV6 (1) suggests that it may negatively regulate expression from P670. For binding assays, fusion protein GST-ΔYY1 was used, which is comprised of the DNA-binding domain of human YY1 protein (amino acids 293 to 414) and GST. GST-ΔYY1 was found to form a complex with the 32P-labeled YY1-wt, an oligonucleotide probe containing the consensus YY1-binding motif (19), but not with YY1-mut, the probe having a mutation in the motif in EMSA (Fig. 5A). Because DNA-binding properties of ΔYY1 and full-length YY1 have been shown to be indistinguishable (23), the EMSA data using GST-ΔYY1 is considered to reflect the behavior of native YY1 in complex formation.

FIG. 5.

Binding of YY1 with synthetic oligonucleotides having partial sequences of the HPV16 E7 ORF. (A) EMSA detecting the complex of GST-ΔYY1 with 32P-labeled probe having sequences with which YY1 has been shown to bind (YY1-wt) or not to bind (YY1-mut) (19) (left panel) and the complex of GST-ΔYY1 with the 32P-labeled HPV16 probes (see Fig. 3A) (right panel). The DNA-protein complexes were electrophoresed on a 5% polyacrylamide gel and visualized by autoradiography. (B) EMSA detecting the complex of GST-ΔYY1 with the 32P-labeled probes having mutations in the putative hSkn-1a binding sites (see the legend to Fig. 3C). (C) EMSA showing displacement of YY1 from the complex of YY1/probe C by Skn-1a. The mixture of GST-ΔYY1 and 32P-labeled probe C or 32P-labeled probe YY1-wt was incubated (inc.) for 30 min. Then GST–Skn-1a was added to the mixture, and the mixture was further incubated for 5 min. The DNA-protein complexes were electrophoresed on a 5% polyacrylamide gel and visualized by autoradiography. Closed and open triangles indicate complexes of GST–ΔYY1/probe C and GST-Skn-1a/probe C, respectively. (D) EMSA detecting the complex of HeLa cell YY1 and 32P-labeled probes. The HeLa extract containing endogenous YY1 was mixed with the probe indicated (see the legends to Fig. 3A and 5A), and the mixture was incubated. The DNA-protein complexes were separated by electrophoresis on a 5% polyacrylamide gel and visualized by autoradiography. To detect the presence of YY1 in the complex, anti-YY1 mouse monoclonal antibody (α-YY1) or purified mouse immunoglobulin G was added to the reaction mixture to show the supershift of the migrating bands. Closed and hatched triangles indicate the complexes of YY1/probe and the YY1/anti-YY1 antibody/probe, respectively. Ab, antibody.

Mobility shift assays showed that the hSkn-1a-binding site serves as a binding site for YY1. GST-ΔYY1 was found to bind to probes C (containing site 1), D (site 1), E (site 2), and I among the probes (A to I) tested (Fig. 5A). However, GST-ΔYY1 did not form a complex with probes mC or mE, which had the nucleotide substitutions in hSkn-1a-binding sites 1 and 2, respectively (Fig. 5B). Sites 1 and 2 contain CAT, the core motif of YY1 binding sites (26, 54) (Fig. 4). Thus, YY1 is likely to bind to sites 1 and 2, sharing these binding sites with hSkn-1a. It should be noted that the signal of GST–ΔYY1/E complex was weaker than that of GST–ΔYY1/C complex in the autoradiograms (Figs. 5A and B), suggesting that the affinity of YY1 is weaker with site 2 (in probe E) than with site 1 (probe C).

Addition of hSkn-1a to the preformed YY1/C complex resulted in displacement of YY1 by hSkn-1a in EMSA (Fig. 5C). The preformed complex of GST-ΔYY1 and 32P-labeled probe C (the complex migrating faster in Fig. 5C) was reformed to make the GST–hSkn-1a/C complex (migrating slower) within 5 min after the addition of GST–hSkn-1a. GST-ΔYY1 made a firm complex with probe YY1-wt, which contains the consensus YY1-binding motif, and the resulting complex was not disrupted by hSkn-1a. Thus, it was concluded that the affinity of site 1 is stronger with hSkn-1a than with YY1.

Using HeLa cell extracts, we attempted to show by EMSA that cellular endogenous YY1 binds to the hSkn-1a-binding site (Fig. 5D). The complex formed in the mixture of the extracts and 32P-labeled probe C was supershifted in the presence of anti-YY1 mouse monoclonal antibody, indicating that the complex contained YY1. With probe mC in place of probe C, however, the complex was undetectable. Thus, like bacterially expressed GST-ΔYY1, endogenous YY1 in HeLa cells was found to bind to site 1 in probe C. On the other hand, binding of probe E with the HeLa extract under the same conditions as above was not detected, probably because of the weaker affinity with site 2.

Expression of luciferase with p670-Luc having mutations in hSkn–1a/YY1 binding sites 1 and 2.

When the nucleotide substitutions that abolished bindings of hSkn-1a and YY1 to probes C and E in EMSAs (Fig. 3C and 5B) were introduced into corresponding regions of mTATA/p670–Luc to abolish bindings with YY1 and hSkn-1a, the basal level of the luciferase expression from P670 without hSkn-1a was raised and the effects of mutations in the two sites were synergistic. Luciferase activities of HeLa cells transfected with mTATA/m1/p670–Luc and mTATA/m2/p670–Luc, which had the mutations in hSkn-1a-binding sites 1 and 2, respectively, were elevated to nearly half of the activities obtained by the activation by hSkn-1a (Fig. 6). Luciferase activity of HeLa cells transfected with mTATA/m1&m2/p670–Luc, of which the two sites were mutated, was higher than those obtained with mTATA/m1/p670–Luc or mTATA/m2/p670–Luc, and the activation by hSkn-1a was no longer prominent. The results indicate that transcription from P670 is primarily suppressed by YY1.

FIG. 6.

Activation of P670 by disruption of the hSkn–1a/YY1-binding sites. The nucleotide substitutions (see the legend to Fig. 3C) were introduced in sites 1 and 2 in mTATA/p670–Luc to generate plasmids lacking binding sites for hSkn–1a/YY1. HeLa cells were cotransfected with 0.2 μg of the plasmids with the mutations and 0.2 μg of pCMV4 or pCMV/Skn–1a. Luciferase activities of cell extracts were measured at 48 h after transfection. Results are presented as means ± standard deviations of three independent experiments.

Effect of hSkn-1a on transcription from P670 of HPV16 DNA.

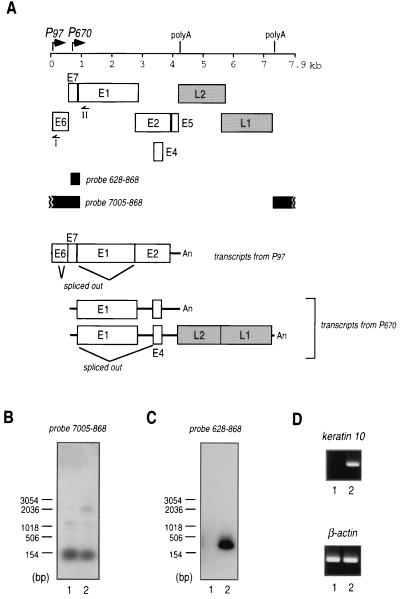

Expression of hSkn-1a resulted in activation of transcription from P670 in HPV16 DNA to produce mRNA encoding the E1 protein (Fig. 7). To analyze the effect of hSkn-1a on authentic transcription from HPV16 DNA, HeLa cells were transfected with a complete circular genome of HPV16 together with pCMV/hSkn–1a or with pCMV4. At 48 h after transfection, mRNA was isolated by oligo(dT) column chromatography, followed by cDNA synthesis. HPV16-specific transcripts were amplified by 5′ RACE using two HPV16-specific primers; primer I anneals the E6 region and primer II anneals the E1 region, which is not present in E1∧E4 mRNA generated by the splicing. The amplified DNA fragments were electrophoresed on an agarose gel, followed by Southern blotting using two radiolabeled probes hybridizing the HPV16 region of nt 7005 to 868 or nt 628 to 868 (Fig. 7A). 5′ RACE with primer I similarly amplified cDNAs derived from transcripts from P97 with or without hSkn-1a (Fig. 7B). The enhancing effect of hSkn-1a on transcription from P97 may be interfered with by E2 protein in a negative-feedback manner. 5′ RACE with primer II amplified cDNA of around 300 bp in the cDNA library constructed from HeLa cells expressing hSkn-1a (Fig. 7C). Without hSkn-1a, the cDNA was not synthesized. The cDNA molecules were cloned into pGEM-T easy plasmid and were sequenced. The 5′ ends of cDNAs were near at nt 670, and the most 5′-upstream nucleotide of cDNAs sequenced was G at nt 694. The function of transiently expressed hSkn-1a was verified by induction of synthesis of keratin 10 mRNA in HeLa cells transfected with pCMV/hSkn–1a (Fig. 7D). Thus, the results obtained in the experiments using expression plasmids for luciferase driven by P670 seem to mimic expression of the E1 gene in HPV16 infection.

FIG. 7.

Transcription from circular HPV16 DNA in HeLa cells expressing hSkn-1a. (A) Schematic representation of the gene organization of HPV16 and transcripts from P97 and P670. I and II are primers used to amplify cDNAs derived from HPV16 transcripts by 5′ RACE. (B) The cDNAs were amplified by 5′ RACE using the primer I and cDNA libraries constructed from HeLa cells transfected with pCMV4 (the backbone plasmid) (lane 1) or pCMV/hSkn–1a (lane 2). The PCR products were electrophoresed in a 0.7% agarose gel, transferred to nylon membranes, and probed with 32P-labeled oligonucleotides derived from the indicated region of HPV16 DNA. cDNAs hybridized with the probes were visualized by autoradiography. (C) Experiments were carried out as described for panel B except that primer II was used for 5′ RACE. (D) PCR-amplified cDNAs of human keratin 10 and human β-actin in cDNA libraries constructed from HeLa cells transfected with pCMV4 (lane 1) or with pCMV/hSkn–1a (lane 2). The cDNA corresponding to the region from exons 2 to 4 of human keratin 10 (44) was amplified using the sense primer 5′-CTAACAACTGAT AATGCCAACATCCTG and the antisense primer 5′-GGGGCA GCATTCATTTCCACATTCACA. Part of the β-actin cDNA was amplified using the primer set of TaqMan β-actin Control Reagent (Perkin Elmer Applied Biosystems). The PCR products were electrophoresed on a 1.2% agarose gel, followed by staining with ethidium bromide. The sequences of the cDNAs agreed with those in the database (GenBank).

DISCUSSION

This study has shown that the POU transcription factor hSkn-1a, which is known to modulate the expression of several genes associated with keratinocyte differentiation (4, 5), activates HPV16 P670 on the expression plasmid and the circular HPV16 DNA in the transient expression assays and that the upstream promoter region contains two specific binding sites for hSkn-la, which are shared by YY1, a transcriptional regulator. The results indicate that hSkn-la is probably capable of activating transcription from P670 by binding to DNA in a sequence-specific manner in natural HPV16 infection. Transcripts from promoters in the E7 ORF, such as P670 and P742 of HPV31, encode helicase (E1) and capsid proteins (L1 and L2) (25, 31, 38). Replication of the HPV genome and accumulation of HPV capsid proteins have been observed in the suprabasal differentiating strata (45), where hSkn-1a is predominantly expressed (4, 5). Thus, hSkn-1a, by activating P670, is likely to initiate HPV16 vegetative replication leading to virion production in differentiating keratinocytes.

Human Skn-1a seems to activate P670 by displacing YY1 bound to the two sites for hSkn-1a. The displacement was shown to occur in vitro in this study (Fig. 5C). Because YY1 is abundant in most cells (47, 51) and is a probable transcriptional repressor in the HPV6 replication (1), it would be reasonable to presume that YY1 in HeLa cells or undifferentiated keratinocytes readily binds to the viral hSkn-1a-binding sites, resulting in repression of P670 on the transfecting expression plasmid or persisting episomal HPV16 DNA (16, 36, 42, 48, 53). In fact, the expression from P670 was enhanced greatly when YY1 was prevented from binding to the promoter region modified by the substitution mutations (Fig. 6). It is probable, therefore, that hSkn-1a emerging in differentiating keratinocytes removes YY1 bound to the hSkn-1a sites in the promoter region on episomal HPV16 DNA and initiate virion production.

The results of substitution analyses (Fig. 6) also suggest that the activation of P670 by hSkn-1a depends mostly on the removal of YY1 but not on the potential activator function of hSkn-1a, because when the binding sites were disrupted by nucleotide substitutions, the basal level of expression from P670 was comparable to that brought about by hSkn-1a-mediated activation. The results are consistent with the fact that the POU domain alone was sufficient to activate the expression as efficiently as the full-length hSkn-1a (Fig. 2).

The putative binding sequence for hSkn-1a, (A/T)TGCA(A/T)XX, found in this study with HPV16 was searched for in the homologous promoter regions of various HPVs (of the HPV Sequence Database of the Los Alamos National Laboratory). The sequence was found in HPV types 6 (11), 18, 31, and 45 but not in types 1, 5, 8, 33, 52, and 58. It remains to be investigated whether hSkn-1a can bind to a different motif or whether a yet unidentified factor(s) other than hSkn-1a can initiate HPV replication in the differentiating cells.

It would be of interest to know whether other keratinocyte-specific transcription factors can activate HPV promoters. Besides Skn-1a, the epidermis contains other POU domain transcription factors, such as Tst-1, Oct-1, and Oct-2 (5). The expression of Tst-1 is also linked to keratinocyte differentiation (12), whereas the ubiquitous factor Oct-1 is expressed independently of the differentiation and Oct-2 is expressed only in undifferentiated keratinocytes. Since Skn-1a and Tst-1 appear to function redundantly in keratinocyte differentiation in mice (5), it is possible that Tst-1 is capable of activating HPV promoters. Understanding the transcriptional regulation of HPVs in differentiating keratinocytes would help develop a cell culture system that allows HPVs to grow efficiently in vitro.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Kunito Yoshiike for critical reading of the manuscript and Peter M. Howley for providing the expression plasmid for the HPV16 E2 protein.

This work was supported by a grant-in-aid from the Ministry of Health and Welfare for the Second-Term Comprehensive 10-year Strategy for Cancer Control and for Research on Human Genome and Gene Therapy and by a research grant from the Princess Takamatsu Cancer Reseach Fund (00-23204).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ai W, Narahari J, Roman A. Yin yang 1 negatively regulates the differentiation-specific E1 promoter of human papillomavirus type 6. J Virol. 2000;74:5198–5205. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.11.5198-5205.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ai W, Toussaint E, Roman A. CCAAT displacement protein binds to and negatively regulates human papillomavirus type 6 E6, E7, and E1 promoters. J Virol. 1999;73:4220–4229. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.4220-4229.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersen B, Hariri A, Pittelkow M R, Rosenfeld M G. Characterization of Skn-1a/i POU domain factors and linkage to papillomavirus gene expression. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15905–15913. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.25.15905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersen B, Schonemann M D, Flynn S E, Pearse R V D, Singh H, Rosenfeld M G. Skn-1a and Skn-1i: two functionally distinct Oct-2-related factors expressed in epidermis. Science. 1993;260:78–82. doi: 10.1126/science.7682011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andersen B, Weinberg W C, Rennekampff O, McEvilly R J, Bermingham J R, Jr, Hooshmand F, Vasilyev V, Hansbrough J F, Pittelkow M R, Yuspa S H, Rosenfeld M G. Functions of the POU domain genes Skn-1a/i and Tst-1/Oct-6/SCIP in epidermal differentiation. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1873–1884. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.14.1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersson S, Davis D L, Dahlback H, Jornvall H, Russell D W. Cloning, structure, and expression of the mitochondrial cytochrome P-450 sterol 26-hydroxylase, a bile acid biosynthetic enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:8222–8229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bedell M A, Hudson J B, Golub T R, Turyk M E, Hosken M, Wilbanks G D, Laimins L A. Amplification of human papillomavirus genomes in vitro is dependent on epithelial differentiation. J Virol. 1991;65:2254–2260. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.5.2254-2260.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bodner M, Castrillo J L, Theill L E, Deerinck T, Ellisman M, Karin M. The pituitary-specific transcription factor GHF-1 is a homeobox-containing protein. Cell. 1988;55:505–518. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chow L T, Nasseri M, Wolinsky S M, Broker T R. Human papillomavirus types 6 and 11 mRNAs from genital condylomata acuminata. J Virol. 1987;61:2581–2588. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.8.2581-2588.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clerc R G, Corcoran L M, LeBowitz J H, Baltimore D, Sharp P A. The B-cell-specific Oct-2 protein contains POU box- and homeobox-type domains. Genes Dev. 1988;2:1570–1581. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.12a.1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong G, Broker T R, Chow L T. Human papillomavirus type 11 E2 proteins repress the homologous E6 promoter by interfering with the binding of host transcription factors to adjacent elements. J Virol. 1994;68:1115–1127. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.2.1115-1127.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faus I, Hsu H J, Fuchs E. Oct-6: a regulator of keratinocyte gene expression in stratified squamous epithelia. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:3263–3275. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.5.3263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finney M, Ruvkun G. The unc-86 gene product couples cell lineage and cell identity in C. elegans. Cell. 1990;63:895–905. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90493-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fischer D F, Gibbs S, van De Putte P, Backendorf C. Interdependent transcription control elements regulate the expression of the SPRR2A gene during keratinocyte terminal differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5365–5374. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flores E R, Allen-Hoffmann B L, Lee D, Sattler C A, Lambert P F. Establishment of the human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV-16) life cycle in an immortalized human foreskin keratinocyte cell line. Virology. 1999;262:344–354. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galvin K M, Shi Y. Multiple mechanisms of transcriptional repression by YY1. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:3723–3732. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.7.3723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldsborough A S, Healy L E, Copeland N G, Gilbert D J, Jenkins N A, Willison K R, Ashworth A. Cloning, chromosomal localization and expression pattern of the POU domain gene Oct-11. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:127–134. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.1.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grassmann K, Rapp B, Maschek H, Petry K U, Iftner T. Identification of a differentiation-inducible promoter in the E7 open reading frame of human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV-16) in raft cultures of a new cell line containing high copy numbers of episomal HPV-16 DNA. J Virol. 1996;70:2339–2349. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2339-2349.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hariharan N, Kelley D E, Perry R P. Delta, a transcription factor that binds to downstream elements in several polymerase II promoters, is a functionally versatile zinc finger protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:9799–9803. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.21.9799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herr W, Cleary M A. The POU domain: versatility in transcriptional regulation by a flexible two-in-one DNA-binding domain. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1679–1693. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.14.1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins G D, Uzelin D M, Phillips G E, McEvoy P, Marin R, Burrell C J. Transcription patterns of human papillomavirus type 16 in genital intraepithelial neoplasia: evidence for promoter usage within the E7 open reading frame during epithelial differentiation. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:2047–2057. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-8-2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hildesheim J, Foster R A, Chamberlin M E, Vogel J C. Characterization of the regulatory domains of the human skn-1a/Epoc-1/Oct-11 POU transcription factor. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26399–26406. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.37.26399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hou S Y, Wu S Y, Zhou T, Thomas M C, Chiang C M. Alleviation of human papillomavirus E2-mediated transcriptional repression via formation of a TATA binding protein (or TFIID)-TFIIB-RNA polymerase II-TFIIF preinitiation complex. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:113–125. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.1.113-125.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Houbaviy H B, Usheva A, Shenk T, Burley S K. Cocrystal structure of YY1 bound to the adeno-associated virus P5 initiator. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13577–13582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hummel M, Hudson J B, Laimins L A. Differentiation-induced and constitutive transcription of human papillomavirus type 31b in cell lines containing viral episomes. J Virol. 1992;66:6070–6080. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.10.6070-6080.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hyde-DeRuyscher R P, Jennings E, Shenk T. DNA binding sites for the transcriptional activator/repressor YY1. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:4457–4465. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.21.4457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ingraham H A, Chen R P, Mangalam H J, Elsholtz H P, Flynn S E, Lin C R, Simmons D M, Swanson L, Rosenfeld M G. A tissue-specific transcription factor containing a homeodomain specifies a pituitary phenotype. Cell. 1988;55:519–529. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jang S I, Karaman-Jurukovska N, Morasso M I, Steinert P M, Markova N G. Complex interactions between epidermal POU domain and activator protein 1 transcription factors regulate the expression of the profilaggrin gene in normal human epidermal keratinocytes. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:15295–15304. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.20.15295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeon S, Allen-Hoffmann B L, Lambert P F. Integration of human papillomavirus type 16 into the human genome correlates with a selective growth advantage of cells. J Virol. 1995;69:2989–2997. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.5.2989-2997.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kanda T, Watanabe S, Yoshiike K. Human papillomavirus type 16 transformation of rat 3Y1 cells. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1987;78:103–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klumpp D J, Laimins L A. Differentiation-induced changes in promoter usage for transcripts encoding the human papillomavirus type 31 replication protein E1. Virology. 1999;257:239–246. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kovelman R, Bilter G K, Glezer E, Tsou A Y, Barbosa M S. Enhanced transcriptional activation by E2 proteins from the oncogenic human papillomaviruses. J Virol. 1996;70:7549–7560. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7549-7560.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kozuka T, Aoki Y, Nakagawa K, Ohtomo K, Yoshikawa H, Matsumoto K, Yoshiike K, Kanda T. Enhancer-promoter activity of human papillomavirus type 16 long control regions isolated from cell lines SiHa and CaSki and cervical cancer biopsies. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2000;91:271–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2000.tb00941.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laimins L A. The biology of human papillomaviruses: from warts to cancer. Infect Agents Dis. 1993;2:74–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lorincz A T, Reid R, Jenson A B, Greenberg M D, Lancaster W, Kurman R J. Human papillomavirus infection of the cervix: relative risk associations of 15 common anogenital types. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;79:328–337. doi: 10.1097/00006250-199203000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.May M, Dong X P, Beyer-Finkler E, Stubenrauch F, Fuchs P G, Pfister H. The E6/E7 promoter of extrachromosomal HPV16 DNA in cervical cancers escapes from cellular repression by mutation of target sequences for YY1. EMBO J. 1994;13:1460–1466. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06400.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meyers C, Frattini M G, Hudson J B, Laimins L A. Biosynthesis of human papillomavirus from a continuous cell line upon epithelial differentiation. Science. 1992;257:971–973. doi: 10.1126/science.1323879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ozbun M A, Meyers C. Characterization of late gene transcripts expressed during vegetative replication of human papillomavirus type 31b. J Virol. 1997;71:5161–5172. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5161-5172.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ozbun M A, Meyers C. Human papillomavirus type 31b E1 and E2 transcript expression correlates with vegetative viral genome amplification. Virology. 1998;248:218–230. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ozbun M A, Meyers C. Temporal usage of multiple promoters during the life cycle of human papillomavirus type 31b. J Virol. 1998;72:2715–2722. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.2715-2722.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rapp B, Pawellek A, Kraetzer F, Schaefer M, May C, Purdie K, Grassmann K, Iftner T. Cell-type-specific separate regulation of the E6 and E7 promoters of human papillomavirus type 6a by the viral transcription factor E2. J Virol. 1997;71:6956–6966. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6956-6966.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raught B, Khursheed B, Kazansky A, Rosen J. YY1 represses beta-casein gene expression by preventing the formation of a lactation-associated complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:1752–1763. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Remm M, Remm A, Ustav M. Human papillomavirus type 18 E1 protein is translated from polycistronic mRNA by a discontinuous scanning mechanism. J Virol. 1999;73:3062–3070. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.3062-3070.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rieger M, Franke W W. Identification of an orthologous mammalian cytokeratin gene. High degree of intron sequence conservation during evolution of human cytokeratin 10. J Mol Biol. 1988;204:841–856. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90045-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ruesch M N, Stubenrauch F, Laimins L A. Activation of papillomavirus late gene transcription and genome amplification upon differentiation in semisolid medium is coincident with expression of involucrin and transglutaminase but not keratin-10. J Virol. 1998;72:5016–5024. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.5016-5024.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ryan A K, Rosenfeld M G. POU domain family values: flexibility, partnerships, and developmental codes. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1207–1225. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.10.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shi Y, Lee J S, Galvin K M. Everything you have ever wanted to know about Yin Yang 1. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1332:F49–F66. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(96)00044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shi Y, Seto E, Chang L S, Shenk T. Transcriptional repression by YY1: a human GLI-Kruppel-related protein, and relief of repression by adenovirus E1A protein. Cell. 1991;67:377–388. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90189-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stoler M H, Wolinsky S M, Whitbeck A, Broker T R, Chow L T. Differentiation-linked human papillomavirus types 6 and 11 transcription in genital condylomata revealed by in situ hybridization with message-specific RNA probes. Virology. 1989;172:331–340. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sturm R A, Das G, Herr W. The ubiquitous octamer-binding protein Oct-1 contains a POU domain with a homeobox subdomain. Genes Dev. 1988;2:1582–1599. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.12a.1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thomas M J, Seto E. Unlocking the mechanisms of transcription factor YY1: are chromatin modifying enzymes the key? Gene. 1999;236:197–208. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00261-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Welter J F, Gali H, Crish J F, Eckert R L. Regulation of human involucrin promoter activity by POU domain proteins. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:14727–14733. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.25.14727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang W M, Inouye C, Zeng Y, Bearss D, Seto E. Transcriptional repression by YY1 is mediated by interaction with a mammalian homolog of the yeast global regulator RPD3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12845–12850. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.12845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yant S R, Zhu W, Millinoff D, Slightom J L, Goodman M, Gumucio D L. High affinity YY1 binding motifs: identification of two core types (ACAT and CCAT) and distribution of potential binding sites within the human beta globin cluster. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:4353–4362. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.21.4353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yukawa K, Butz K, Yasui T, Kikutani H, Hoppe-Seyler F. Regulation of human papillomavirus transcription by the differentiation-dependent epithelial factor Epoc-1/skn-1a. J Virol. 1996;70:10–16. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.10-16.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yukawa K, Yasui T, Yamamoto A, Shiku H, Kishimoto T, Kikutani H. Epoc-1: a POU-domain gene expressed in murine epidermal basal cells and thymic stromal cells. Gene. 1993;133:163–169. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90634-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.zur Hausen H. Papillomavirus infections—a major cause of human cancers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1288:F55–F78. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(96)00020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.zur Hausen H. Papillomaviruses causing cancer: evasion from host-cell control in early events in carcinogenesis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:690–698. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.9.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]