Abstract

Boron-doped acenes have attracted attention due to their unique structures and intriguing luminescent properties. However, the hitherto known boron-doped acenes have only one or two boron atoms, limiting the chemical space of this unique family of compounds and the capability to tune their optical properties. Herein, we report the synthesis of quadruply boron-doped acenes, including pentacene, heptacene, and nonacene. The importance of the boron doping level on the luminescent properties of acenes is demonstrated. The title compounds manifest enhanced Lewis acidity as compared with dihydrodiboraacenes, leading to Lewis-base-responsive emission in the solid state. Moreover, quadruply boron-doped nonacene displays mechanochromic luminescence in addition to Lewis-base-responsive properties, realizing high-contrast solid-state multicolor emission. This work greatly expands the chemistry of boron-doped acenes and offers opportunities for developing boron-based luminescent materials.

Subject terms: Chemical synthesis, Organic chemistry, Optical materials

Boron-doped acenes have attracted attention due to their unique structures and luminescent properties but the hitherto known boron-doped acenes have only one or two boron atoms, limiting the chemical space of this family of compounds. Here, the authors demonstrate the synthesis of quadruply boron-doped acenes, including pentacene, heptacene, and nonacene.

Introduction

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) consisting of linearly fused benzene rings, namely acenes (Fig. 1a), have attracted tremendous attention due to their great potential in organic optoelectronics1–11. The introduction of heteroatoms into the acene backbones toward heteroacenes has proven as a viable strategy for modulating their properties and functions12–17. Furthermore, controlling the number of heteroatoms plays a vital role in precisely manipulating their electronic structures and establishing reliable structure–property relationships18–24.

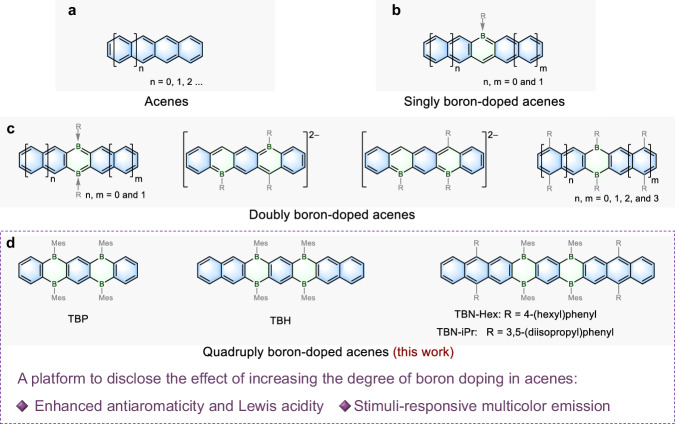

Fig. 1. Molecular design of the quadruply boron-doped acenes.

a General structure of acenes. b, c Previously reported boron-doped acenes containing one or two boron atoms. R represents various substituents. d Chemical structures of quadruply boron-doped acenes reported in this work, including tetrahydrotetraborapentacene (TBP), tetrahydrotetraboraheptacene (TBH), and tetrahydrotetraboranonacenes (TBN-Hex and TBN-iPr). Mes: 2,4,6-trimethylphenyl.

Among various heteroatoms, boron possesses a unique vacant p-orbital, thus endowing the π-conjugated system with electron-deficient character25–36, Lewis acidity37–40, and stimuli-responsive properties41–43. Therefore, boron-doped acenes have attracted considerable attention, particularly due to their value as highly luminescent materials44–47. Up to now, very few types of boron-doped acenes with only one or two boron atoms have been reported (Fig. 1b, c)48–50, whereas those with more than two boron atoms have remained elusive.

Herein, we report the synthesis of quadruply boron-doped acenes (Fig. 1d), including tetrahydrotetraborapentacene (TBP), tetrahydrotetraboraheptacene (TBH), and tetrahydrotetraboranonacenes (TBN-Hex and TBN-iPr). These boron-doped acenes exhibit stronger Lewis acidity than the previously reported dihydrodiboraacenes, allowing for the modulation of their solid state emission properties by the formation/disassociation of Lewis acid–base adducts. Moreover, TBN-Hex, with the longest backbone, shows a loose lamella-type packing, which enables further manipulation of solid state fluorescence by external forces. Variation of the doping level of acenes thus provides a class of tetrahydrotetraboraacenes as multicolor emissive materials.

Results

Synthesis and characterizations of quadruply boron-doped acenes

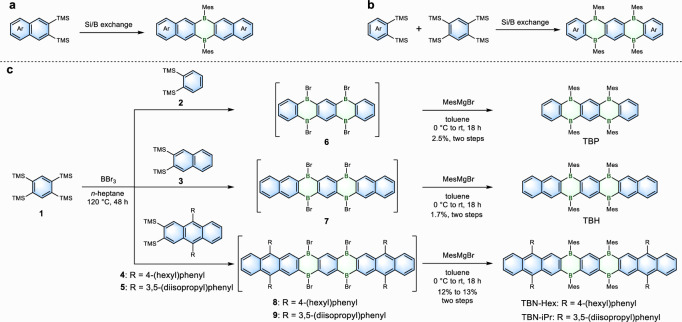

The Si/B exchange reaction has been widely used to synthesize different dihydrodiboraacenes via the AA-type homo-annelation of two bis(trimethylsilyl)-substituted arenes (Fig. 2a)48. In this work, we develop an ABA-type cross-annelation strategy to achieve the synthesis of quadruply boron-doped acenes (Fig. 2b). The synthetic route is depicted in Fig. 2c. The ABA-type cross-annelation of 1,2,4,5-tetrakis(trimethylsilyl)benzene 1 (one equivalent) and the corresponding bis(trimethylsilyl)-functionalized arenes 2–5 (two equivalents) in the presence of boron tribromide (BBr3) was carried out to construct the tetrahydrotetraboraacene backbones (6–9). Then, the bulky mesityl (Mes) moieties were introduced via a nucleophilic substitution, giving TBP, TBH, TBN-Hex, and TBN-iPr in 2.5, 1.7, 13, and 12% yields, respectively. Such relatively low yields were also reported for the synthesis of dihydrodiboraacenes. Improvements became possible by varying the solvent and reaction time51–53. Notably, the AA-type homo-annelation of bis(trimethylsilyl)-functionalized arenes 2–5 was also observed in this reaction (see Methods), but the multi-boron-doped acenes with six or more boron atoms were not isolated, even by further modulating the ratio of the precursors. The obtained quadruply boron-doped acenes show good air stability in solutions (Supplementary Fig. 28), and are characterized by 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopies as well as high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS).

Fig. 2. Synthesis of quadruply boron-doped acenes.

a The previously reported AA-type homo-annelation strategy for the synthesis of dihydrodiboraacenes. b The ABA-type cross-annelation strategy in this work for the synthesis of quadruply boron-doped acenes. c Synthetic route to quadruply boron-doped acenes TBP, TBH, TBN-Hex, and TBN-iPr. MesMgBr: mesitylmagnesium bromide.

Single crystals of TBP and TBH suitable for X-ray structural analysis (Fig. 3a, b) were obtained. The growth of high-quality single crystals of TBN-Hex was difficult, mainly because of the four flexible hexyl chains. Nevertheless, the backbone and the packing structures could be analyzed (Supplementary Fig. 25). In this regard, TBN-iPr with shorter alkyl chains was employed for crystal growth and proved successful (Fig. 3c), while TBN-Hex was mainly used for further spectroscopic characterizations due to its higher solubility in common organic solvents. Both TBP and TBH exhibit a planar π-conjugated framework, whereas TBN-iPr displays a bent geometry. In the C4B2 rings, the C–B bond lengths (1.55–1.56 Å) are slightly shorter than the known C–B single bonds in triphenylborane (1.57–1.59 Å)54, and the C=C bond lengths (1.42–1.45 Å) are longer than the common aromatic C=C bonds (1.41–1.42 Å), demonstrating the 4π antiaromatic character (Fig. 3d–f). Further theoretical calculations, including the nucleus-independent chemical shift (NICS) values, the isotropic chemical shielding surface (ICSS) maps, and the anisotropy of the induced current density (ACID) plots demonstrate the gradually decreased antiaromaticity of the C4B2 rings from quadruply boron-doped pentacene to heptacene and nonacene, which can be attributed to the increased number of aromatic benzene rings reducing the local antiaromaticity by electron delocalization (Fig. 3g–i and Supplementary Figs. 47,48)55.

Fig. 3. Single-crystal X-ray analysis and calculated aromaticity of quadruply boron-doped acenes.

a–c Top and side views of single-crystal structures of TBP, TBH, and TBN-iPr. Thermal ellipsoids are shown at 50% probability. Hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity. d–f Selected bond lengths. g–i Calculated 2D isotropic chemical shielding surface (ICSS) maps at 1 Å above the XY plane.

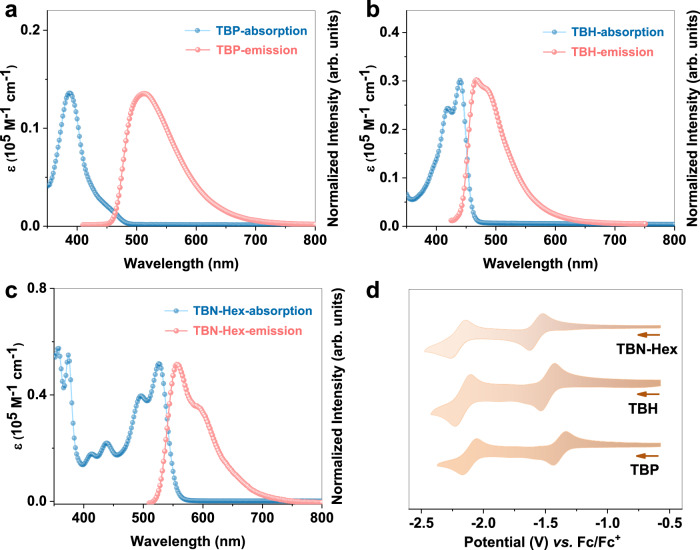

TBP exhibits a broad optical absorption peaking at λabs = 387 nm, whereas TBH and TBN-Hex show typical vibronic absorption bands with λabs at 440 and 526 nm, respectively (Fig. 4a–c). Time-dependent density functional theory (TDDFT) calculations reveal that the S0 → S1 transitions of TBP and TBH are forbidden (oscillator strength f = 0.0000), while the allowed transitions are S0 → S10 (f = 0.2893) for TBP and S0 → S9 (f = 0.3268) for TBH (Supplementary Tables 5–7). By contrast, TBN-Hex shows an allowed S0 → S1 transition with a high oscillator strength of 0.6560, which is in accordance with the large molar extinction coefficient (ε) of 51750 M−1 cm−1 (Supplementary Table 4). The emission maxima (λem) of TBP, TBH, and TBN-Hex are at 512, 466, and 559 nm, and the absolute fluorescence quantum yields (ΦF) of these three compounds are determined as 2, 6, and 90%, respectively. Theoretical calculations of the S1 excited states show that the S1 → S0 transitions of TBP and TBH are forbidden (f = 0.0000), whereas quadruply boron-doped nonacene exhibits an allowed S1 → S0 transition with a large oscillator strength of 0.7386, which is responsible for its high ΦF (Supplementary Tables 8–10).

Fig. 4. Photophysical and electrochemical properties of quadruply boron-doped acenes.

a–c UV-vis absorption (c = 1.0 × 10−5 M) and normalized fluorescence (c = 1.0 × 10−6 M) spectra of tetrahydrotetraboraacenes in toluene solutions. Excitation wavelength: 380 nm for TBP, 400 nm for TBH, 490 nm for TBN-Hex. d Cyclic voltammograms (scan rate: 100 mV s−1) of tetrahydrotetraboraacenes in tetrahydrofuran at room temperature with 0.1 M n-Bu4NPF6 as the supporting electrolyte. The potential was externally calibrated by the ferrocene/ferrocenium redox couple.

The electrochemical properties of TBP, TBH, and TBN-Hex were characterized by cyclic voltammetry (CV) and differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) measurements in tetrahydrofuran (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 27). All compounds exhibit two reversible reduction waves, with the first half-wave potentials (E1/2red) at −1.38 V for TBP, −1.51 V for TBH, and −1.57 V for TBN-Hex, indicating that these tetrahydrotetraboraacenes have higher electron affinities than their corresponding dihydrodiboraacenes with the first E1/2red values ranging from −2.03 to −2.05 V (Supplementary Table 4). According to the DPV data, the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) energies of TBP, TBH, and TBN-Hex are determined as −3.43, −3.30, and −3.23 eV, respectively, which are lower than those of dihydrodiboraacenes with the same backbone lengths (−2.72 to −2.78 eV).

The Lewis acidity of boron suggested us to investigate the binding constants of quadruply boron-doped acenes with a Lewis base (pyridine). Titration experiments were performed by monitoring the UV-vis absorption spectra in toluene solutions (Supplementary Fig. 29). Upon adding pyridine from 0 to 2.0 × 10−3 M, the low-energy absorption bands of TBP, TBH, and TBN-Hex gradually decrease, showing isosbestic points at 370, 401, and 486 nm, respectively. By contrast, the absorption spectra of dihydrodiboraacenes remain almost unchanged even upon addition of excess pyridine, demonstrating that increasing the number of boron centers boosts the Lewis acidity of boraacenes (Supplementary Fig. 34). To investigate the upper limit of pyridine coordination with the quadruply boron-doped acenes, we have measured the absorption and fluorescence spectra in pure pyridine, which show different changes compared with the titration results in toluene solutions. Further single-crystal X-ray analysis confirms a 1:2 coordination mode (one boraacene coordinated with two pyridine molecules) for TBP with pyridine (Supplementary Fig. 32). Two pyridine molecules coordinate to the boron atoms in a meta-anti mode (Supplementary Fig. 33). This experimental observation is in accordance with DFT calculations, which reveal that the meta-anti coordination mode has the lowest energy among all the possible 1:2 coordinated complexes (Supplementary Table 11). Moreover, the titration experiment of the quadruply boron-doped acenes with a stronger pyridine base 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) in toluene solutions was performed (Supplementary Fig. 35). As increasing the concentration of DMAP, the absorption spectra of the three compounds exhibit similar changes to the pyridine titration results, with the absorption isosbestic points at 372 nm for TBP, 401 nm for TBH, and 486 nm for TBN-Hex. Further adding DMAP leads to new absorption and emission maxima, with new absorption isosbestic points at 350 nm for TBP, 361 nm for TBH, and 371 nm for TBN-Hex. The absorption curves match well with those in the pyridine solution, indicating the formation of 1:2 complexes (Supplementary Fig. 36). Therefore, the first isosbestic points in the initial titration process suggest the formation of 1:1 complexes. The similar absorption changes in the pyridine titration process to the initial DMAP titration results indicate that these quadruply boron-doped acenes can only form 1:1 complexes with pyridine in toluene solutions.

Based on these results, the binding constants K for the three quadruply boron-doped acenes with pyridine and the two-step binding constants K1 and K2 with DMAP are calculated and summarized in Supplementary Table 12. For the DMAP complexes, the ratio of 4K2/K1 (that is, the α value) is smaller than one, demonstrating that the formation of 1:1 complexes is favorable over 1:2 complexes56. Therefore, stepwise coordination is observed in toluene. Differently, for the pyridine complexes, the small K values (884 ± 31 M−1 for TBP, 687 ± 16 M−1 for TBH, and 146 ± 3 M−1 for TBN-Hex) of the quadruply boron-doped acenes with pyridine determine that only the 1:1 complexes are observed in toluene, while the 1:2 complexes can be achieved with pyridine as the solvent. The gradually decreased K values from TBP to TBH and TBN-Hex are attributed to the enhanced electron-donating effect of the terminal groups (from benzene to naphthene and anthracene), which decrease the Lewis acidity of the boron atoms. These results are in accordance with the gradually increased LUMO energies and the decreased antiaromaticity of the C4B2 rings57.

Stimuli-responsive multicolor emission of quadruply boron-doped acenes

The emission of boron-containing chromophores can be finely adjusted by dynamic coordination of boron with Lewis bases, which makes them promising candidates as stimuli-responsive materials41. Nevertheless, this behavior has rarely been investigated in the solid state. Exposing the solids of tetrahydrotetraboraacenes to pyridine vapors results in the changes of λem from 489 to 508 nm for TBP, from 519 to 504 nm for TBH, and from 576 to 514 nm for TBN-Hex (Fig. 5a–c). Obviously, TBP and TBH exhibit small emission wavelength changes, while TBN-Hex shows a pronounced blue-shifted emission maximum. The corresponding Commission International de l’Eclairage (CIE) coordinates change from (0.26, 0.47) to (0.22, 0.50) for TBP, from (0.33, 0.54) to (0.21, 0.48) for TBH, and from (0.52, 0.48) to (0.31, 0.59) for TBN-Hex (Supplementary Fig. 40). Moreover, the emission colors can be restored by annealing the exposed solids at 80 °C for three hours. To shed light on the coordination mode in the solid state, the emission spectra of the pyridine-fumed TBP sample and the single crystal of TBP•2pyridine complex are compared (Supplementary Fig. 41). The difference in the emission spectra excludes the possibility of forming the 1:2 complex. In addition, the pyridine-fumed TBP sample shows negligible emission changes compared with the pristine TBP sample. Such a phenomenon is consistent with the titration result of TBP in toluene solutions in the 1:1 coordinated state with pyridine bases, indicating that only a 1:1 complex of TBP with pyridine is formed in the solid state. Because the binding constants with pyridine is decreasing from TBP to TBH and TBN-Hex, it is reasonable to conclude that only the 1:1 complexes can be formed upon pyridine fuming in the solid state for all the three compounds. Furthermore, the different emission spectra of TBN-Hex in the pristine and the fumed states indicate that the pyridine-fumed quadruply boron-doped boraacenes are completely converted to the 1:1 complexes.

Fig. 5. Pyridine-responsive solid state fluorescence of quadruply boron-doped acenes.

Normalized fluorescence spectra of a TBP, b TBH, and c TBN-Hex powders in the pristine, pyridine-fumed, and heated states. Excitation wavelengths for TBP, TBH, and TBN-Hex samples (in the pristine state: 420, 350, and 510 nm; in the pyridine-fumed state: 390, 350, and 430 nm; in the heated state: 400, 350, and 490 nm). The images above the spectra show the corresponding photoluminescence photographs under 365 nm UV light.

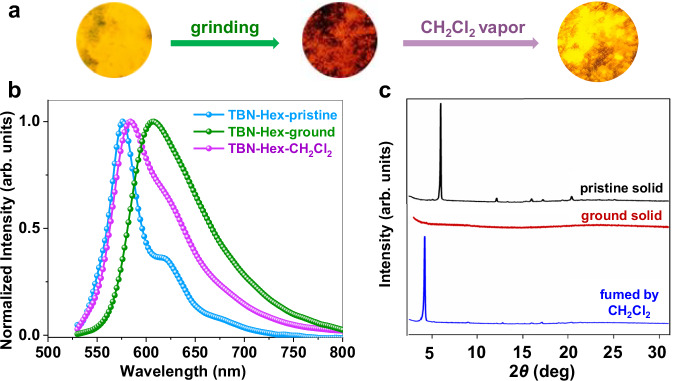

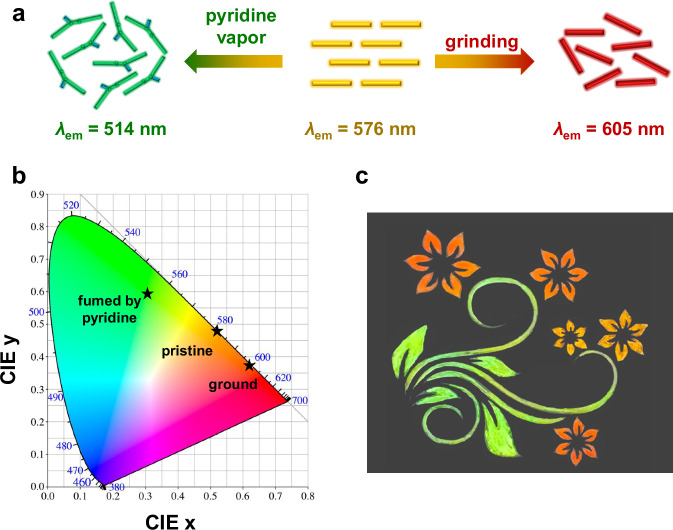

Upon grinding the TBN-Hex powder, the emission color dramatically changed from yellow (λem = 576 nm) to red (λem = 605 nm) (Fig. 6a, b). Further fuming the ground TBN-Hex solid with dichloromethane led to an emissive solid with λem at 583 nm. By contrast, grinding TBP and TBH powders did not substantially alter the emission colors (Supplementary Fig. 43). Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) was performed to give more insights into the mechanochromic luminescence process (Fig. 6c). The pristine TBN-Hex solid exhibits an intense first-order diffraction peak at 6.0° and several weak peaks at around 10°–25°, indicating an ordered packing structure with a d-spacing of 7.4 Å. Upon grinding the solid in a mortar, all diffraction peaks disappear, revealing the amorphous nature. Interestingly, a diffraction peak at 4.2° (corresponding to a d-spacing of 10.5 Å) is observed in the dichloromethane-treated TBN-Hex solid, indicating the formation of a new crystalline phase different from the pristine solid. Such stimuli-responsive properties are related to the loose lamella-type packing structures (Supplementary Fig. 25)58,59.

Fig. 6. Mechanochromic luminescence of TBN-Hex.

a The photoluminescent photographs under 365 nm UV light, b normalized fluorescence spectra, and c powder X-ray diffraction patterns of TBN-Hex powder in the pristine, ground, and dichloromethane-fumed states. Excitation wavelength: 510 nm.

TBN-Hex represents an unusual boron-doped chromophore showing both mechanochromic luminescence and Lewis-base-responsive emission in one compound, which makes it a molecular system for increasing the magnitude of stimuli-responsive fluorescence changes in the solid state. Notably, TBN-Hex solid exhibits remarkable fluorescence change (λem from 514 to 605 nm) and high color contrast (from green to red in the CIE coordinate diagram) (Fig. 7a, b). The large λem shift (∆λem = 91 nm) of the TBN-Hex solid represents a record for stimuli-responsive boron-doped PAHs (∆λem < 80 nm)60,61. The utilization of a single compound TBN-Hex to draw a painting with multiple emission colors is thus demonstrated (Fig. 7c), highlighting the potential of quadruply boron-doped acenes as responsive luminescent materials.

Fig. 7. Stimuli-responsive multicolor emission of TBN-Hex.

a Schematic illustration and b CIE coordinate diagrams of TBN-Hex solid in different states. CIE Commission International de l’Eclairage. c A painting on a filter paper (under 365 nm UV light) drawn with the single compound TBN-Hex. Red and yellow-orange flowers are accessible by controlling the grinding strength with a lab spoon.

Discussion

In summary, we have achieved the synthesis of quadruply boron-doped acenes, including pentacene, heptacene, and nonacene, realizing the highest doping level of boron in acenes. Compared with the previously reported dihydrodiboraacenes, these tetrahydrotetraboraacenes with a higher number of boron centers exhibit higher Lewis acidity, resulting in stimuli-responsive emissions in the solid state. Moreover, the nonacene homolog shows mechanochromic luminescence properties due to its loose lamellar packing, leading to high-contrast multicolor emission with the largest λem shift (91 nm) among all boron-doped PAHs. The work thus represents a step forward in the development of boron-doped acenes and opens up an avenue to exploit heteroacenes as smart luminescent materials in the future.

Methods

Synthesis of TBP

To a solution of 2 (602 mg, 2.71 mmol) and 1 (497 mg, 1.35 mmol) in n-heptane (2 mL) was added BBr3 (1.0 mL, 10.8 mmol) at room temperature under an argon atmosphere. The solution was stirred at 120 °C in a sealed tube for 48 h. After cooling down to room temperature, the mixture was filtrated and the resulting residue was washed with dry hexane for three times and used for the next step directly without further purification.

The obtained solid (125 mg, 0.212 mmol) was suspended in toluene (2 mL) at 0 °C under an argon atmosphere. MesMgBr (1.7 mL, 1.70 mmol, 1.0 M in THF) was slowly added, and the solution was stirred at room temperature for 18 h. Then, the reaction was quenched with aqueous NH4Cl (5 mL), and the mixture was extracted with dichloromethane three times. The combined organic layers were dried over anhydrous MgSO4. After removal of the solvents under reduced pressure, the residue was purified via column chromatography over neutral Al2O3 (eluent: PE/DCM = 1: 0 to 10: 1, V/V), giving TBP as a yellow solid (25 mg, 2.5%) and dihydrodiboraanthracene (DBA, see Supplementary Fig. 1) as a white solid (90 mg, 16%). TBP: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD2Cl2, 298 K, ppm) δ 7.65–7.58 (m, 6H; Ar-H), 7.47 (dd, JH,H = 5.6 and 3.6 Hz, 4H; Ar-H), 6.77 (s, 8H; Ar-H), 2.35 (s, 12H; CH3), 1.91 (s, 24H; CH3). 13C NMR (400 MHz, CD2Cl2, 298 K, ppm) δ 149.4, 148.2, 145.7, 140.4, 139.4, 137.8, 137.1, 133.9, 127.0, 22.7, 21.3. The 11B NMR spectrum was not obtained due to the low solubility. HRMS (MALDI) m/z: Calcd. for C54H54B4Na: 769.4495; Found: 769.4511 [M + Na]+. DBA: The characterization data were in accordance with those in the literature62.

Synthesis of TBH

To a solution of 3 (816 mg, 2.99 mmol) and 1 (550 mg, 1.50 mmol) in n-heptane (5 mL) was added BBr3 (1.2 mL, 12.0 mmol) at room temperature under an argon atmosphere. The solution was stirred at 120 °C in a sealed tube for 48 h. After cooling down to room temperature, the mixture was filtrated and the resulting residue was washed with dry hexane for three times and used for the next step directly without further purification.

The obtained solid (630 mg, 0.914 mmol) was suspended in toluene (8 mL) at 0 °C under an argon atmosphere. MesMgBr (4.6 mL, 4.60 mmol, 1.0 M in THF) was slowly added, and the solution was stirred at room temperature for 18 h. Then the reaction was quenched with aqueous NH4Cl (15 mL), and the mixture was extracted with dichloromethane for three times. The combined organic layers were dried over anhydrous MgSO4. After removal of the solvents under reduced pressure, the residue was purified via column chromatography over neutral Al2O3 (eluent: PE/DCM = 1: 0 to 5: 1, V/V), giving TBH as a yellow solid (22 mg, 1.7%) and dihydrodiborapentacene (DBP, see Supplementary Fig. 1) as a yellowish solid (190 mg, 25%). TBH: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD2Cl2, 298 K, ppm) δ 8.20 (s, 4H; Ar-H), 7.82 (dd, JH,H = 6.4 and 3.6 Hz, 4H; Ar-H), 7.72 (s, 2H; Ar-H), 7.53 (dd, JH,H = 6.4 and 3.2 Hz, 4H; Ar-H), 6.81 (s, 8H; Ar-H), 2.40 (s, 12H; CH3), 1.95 (s, 24H; CH3). 13C NMR (400 MHz, CD2Cl2, 298 K, ppm) δ 150.2, 148.6, 142.1, 141.5, 140.7, 138.1, 137.0, 136.3, 130.1, 128.9, 127.0, 22.8, 21.4. The 11B NMR spectrum was not obtained due to the low solubility. HRMS (MALDI) m/z: Calcd. for C62H58B4Na: 869.4808; Found: 869.4817 [M + Na]+. DBP: The characterization data were in accordance with those in the literature53.

Synthesis of TBN-Hex

To a solution of 4 (500 mg, 0.777 mmol) and 1 (143 mg, 0.390 mmol) in n-heptane (1 mL) was added BBr3 (3.1 mL, 3.10 mmol, 1.0 M in n-heptane) at room temperature under an argon atmosphere. The solution was stirred at 120 °C in a sealed tube for 48 h. After cooling down to room temperature, the mixture was filtrated and the resulting residue was washed with dry hexane for three times and used for the next step directly without further purification.

The obtained solid (238 mg, 0.166 mmol) was suspended in toluene (5 mL) at 0 °C under an argon atmosphere. MesMgBr (0.8 mL, 0.800 mmol, 1.0 M in THF) was slowly added, and the solution was stirred at room temperature for 18 h. Then the reaction was quenched with aqueous NH4Cl (6 mL), and the mixture was extracted with dichloromethane for three times. The combined organic layers were dried over anhydrous MgSO4. After removal of the solvents under reduced pressure, the residue was purified via column chromatography over neutral Al2O3 (eluent: PE/DCM = 10: 1 to 5: 1, V/V), giving TBN-Hex as an orange solid (78 mg, 13%) and dihydrodiboraheptacene (DBH-Hex, see Supplementary Fig. 1) as a green solid (125 mg, 26%). TBN-Hex: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD2Cl2, 298 K, ppm) δ 7.99 (s, 4H; Ar-H), 7.89 (s, 2H; Ar-H), 7.77 (dd, JH,H = 6.4 and 3.2 Hz, 4H; Ar-H), 7.35 (dd, JH,H = 7.2 and 3.2 Hz, 4H; Ar-H), 7.25 (d, 3JH,H = 8.0 Hz, 8H; Ar-H), 7.19 (d, 3JH,H = 7.6 Hz, 8H; Ar-H), 6.64 (s, 8H; Ar-H), 2.72 (t, 3JH,H = 8.0 Hz, 8H; CH2) 2.30 (s, 12H; CH3), 1.86 (s, 24H; CH3), 1.76-1.67 (m, 8H; CH2), 1.50–1.38 (m, 24H; CH2), 0.98 (m, 12H; CH3). 13C NMR (400 MHz, CD2Cl2, 298 K, ppm) δ 150.8, 148.6, 142.8, 142.6, 140.5, 139.8, 137.9, 136.6, 135.1, 132.0, 131.6, 131.4, 128.4, 128.3, 127.9, 126.7, 126.5, 36.2, 32.2, 32.1, 29.8, 23.2, 22.9, 21.4, 14.4. The 11B NMR spectrum was not obtained due to the low solubility. HRMS (MALDI) m/z: Calcd. for C118H126B4: 1587.0232; Found: 1587.0288 [M]+. DBH-Hex: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD2Cl2, 298 K, ppm) δ 8.10 (s, 4H; Ar-H), 7.80 (dd, JH,H = 6.8 and 3.2 Hz, 4H; Ar-H), 7.35 (dd, JH,H = 6.8 and 2.8 Hz, 4H; Ar-H), 7.25 (d, 3JH,H = 8.0 Hz, 8H; Ar-H), 7.22 (d, 3JH,H = 8.0 Hz, 8H; Ar-H), 6.66 (s, 4H; Ar-H), 2.71 (t, 3JH,H = 7.6 Hz, 8H; CH2), 2.31 (s, 6H; CH3), 1.91 (s, 12H; CH3), 1.72 (m, 8H; CH2), 1.51–1.40 (m, 24H; CH2), 0.99 (m, 12H; CH3). HRMS (MALDI) m/z: Calcd. for C94H102B2: 1252.8168; Found: 1252.8203 [M]+.

Synthesis of TBN-iPr

To a solution of 5 (404 mg, 0.628 mmol) and 1 (115 mg, 0.313 mmol) in n-heptane (1 mL) was added BBr3 (2.6 mL, 2.60 mmol, 1.0 M in n-heptane) at room temperature under an argon atmosphere. The solution was stirred at 120 °C in a sealed tube for 48 h. After cooling down to room temperature, the mixture was filtrated and the resulting residue was washed with dry hexane for three times and used for the next step directly without further purification.

The obtained solid (110 mg, 0.0769 mmol) was suspended in toluene (2 mL) at 0 °C under an argon. MesMgBr (0.4 mL, 0.400 mmol, 1.0 M in THF) was slowly added, and the solution was stirred at room temperature for 18 h. Then the reaction was quenched with aqueous NH4Cl (3 mL), and the mixture was extracted with dichloromethane for three times. The combined organic layers were dried over anhydrous MgSO4. After removal of the solvents under reduced pressure, the residue was purified via column chromatography over neutral Al2O3 (eluent: PE/DCM = 20: 1 to 10: 1, V/V), giving TBN-iPr as an orange solid (57 mg, 12%) and dihydrodiboraheptacene (DBH-iPr, see Supplementary Fig. 1) as a green solid (24 mg, 6%). TBN-iPr: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD2Cl2, 298 K, ppm) δ 7.90 (s, 4H; Ar-H), 7.82 (s, 2H; Ar-H), 7.69 (dd, JH,H = 6.8 and 3.2 Hz, 4H; Ar-H), 7.34 (dd, JH,H = 6.8 and 3.2 Hz, 4H; Ar-H), 7.09 (s, 4H; Ar-H), 6.92 (d, 3JH,H = 1.2 Hz, 8H; Ar-H), 6.56 (s, 8H; Ar-H), 2.87 (m, 8H; CH), 2.27 (s, 12H; CH3), 1.79 (s, 24H; CH3), 1.21 (t, 3JH,H = 6.4 Hz, 48H; CH3). 13C NMR (400 MHz, CD2Cl2, 298 K, ppm) δ 149.0, 142.9, 141.4, 138.0, 137.6, 136.4, 131.9, 131.6, 128.1, 126.8, 126.44, 126.37, 124.1, 34.5, 24.2, 24.1, 22.9. The signals of the carbon atoms connected to the boron were not observed due to the quadrupolar relaxation of the boron atom. The 11B NMR spectrum was not obtained due to the low solubility. HRMS (MALDI) m/z: Calcd. for C118H126B4: 1587.0232; Found: 1587.0298 [M]+. DBH-iPr: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD2Cl2, 298 K, ppm) δ 7.97 (s, 4H; Ar-H), 7.71 (dd, JH,H = 6.4 and 3.2 Hz, 4H; Ar-H), 7.34 (dd, JH,H = 6.8 and 3.2 Hz, 4H; Ar-H), 7.09 (s, 4H; Ar-H), 6.93 (d, 3JH,H = 1.2 Hz; 8H; Ar-H), 6.52 (s, 4H; Ar-H), 2.88 (m, 8H; CH), 2.27 (s, 6H; CH3), 1.80 (s, 12H; CH3), 1.22 (m, 48H; CH3). HRMS (MALDI) m/z: Calcd. for C94H102B2: 1252.8168; Found: 1252.8196 [M]+

Spectroscopy analysis

Absorption spectra were recorded on an Analytikjena Specord 210 Plus UV-vis spectrophotometer. Photoluminescence spectra were recorded on an Edinburgh FS5 Spectrofluorometer. The photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) was measured by using an integrating sphere. The electrochemical measurements were carried out in anhydrous THF containing 0.1 M n-Bu4NPF6 as supporting electrolyte (scan rate: 100 mV s–1) under an argon atmosphere on a CHI 620E electrochemical analyzer. A three-electrode system with glassy carbon as the working electrode, Ag/AgCl as the reference electrode, and platinum wire as the counter electrode was applied. The potential was calibrated against the ferrocene/ferrocenium couple.

Supplementary information

Source data

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 22071120, 92256304, and 22221002 to X.-Y.W.), the National Key R&D Program of China (2020YFA0711500 to X.-Y.W.), the Beijing National Laboratory for Molecular Sciences (BNLMS2023013 to X.-Y.W.), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (to X.-Y.W.). The authors cordially thank Dr. Haibin Song and Mr. Hua Rong (College of Chemistry, Nankai University), as well as Dr. Dieter Schollmeyer (Department of Chemistry, Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz) for single-crystal X-ray structural analysis.

Author contributions

X.-Y.W. conceived the project. C.C., Y.G., and Z.C. synthesized the compounds and conducted all characterizations and theoretical studies under the supervision of X.-Y.W. C.C., K.M., and X.-Y.W. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors commented on it.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers 2284558 (TBP), 2220546 (TBH), 2259158 (TBN-Hex), 2220548 (TBN-iPr), and 2331286 (TBP•2pyridine). These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. Synthetic procedures and data, experimental details, photophysical and electrochemical characterizations, and theoretical calculations are provided in the Supplementary Information. Additional data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-024-51806-8.

References

- 1.Anthony, J. E. Functionalized acenes and heteroacenes for organic electronics. Chem. Rev.106, 5028–5048 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anthony, J. E. The larger acenes: versatile organic semiconductors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.47, 452–483, (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tönshoff, C. & Bettinger, H. F. Pushing the limits of acene chemistry: the recent surge of large acenes. Chem. Eur. J.27, 3193–3212 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, W., Yu, F., Xu, Q., Zhou, G. & Zhang, Q. Recent progress in high linearly fused polycyclic conjugated hydrocarbons (PCHs, n > 6) with well-defined structures. Adv. Sci.7, 1903766 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ye, Q. & Chi, C. Recent highlights and perspectives on acene based molecules and materials. Chem. Mater.26, 4046–4056 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kitao, T. et al. Synthesis of polyacene by using a metal–organic framework. Nat. Synth. 2, 848–854 (2023).

- 7.Parenti, K. R. et al. Quantum interference effects elucidate triplet-pair formation dynamics in intramolecular singlet-fission molecules. Nat. Chem. 15, 339–346 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Watanabe, M. et al. The synthesis, crystal structure and charge-transport properties of hexacene. Nat. Chem. 4, 574–578, (2012). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Jancarik, A., Holec, J., Nagata, Y., Samal, M. & Gourdon, A. Preparative-scale synthesis of nonacene. Nat. Commun.13, 223 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Urgel, J. I. et al. On-surface light-induced generation of higher acenes and elucidation of their open-shell character. Nat. Commun. 10, 861 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Zeitter, N. et al. Persistent ambipolar heptacenes and their redox species. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202200918 (2022).. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Eimre, K. D. et al. On-Surface synthesis and characterization of nitrogen-substituted undecacenes. Nat. Commun. 13, 511 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Chen, C., Du, C.-Z. & Wang, X.-Y. The rise of 1,4-BN-heteroarenes: synthesis, properties, and applications. Adv. Sci.9, 2200707 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li, W. et al. BN-anthracene for high-mobility organic optoelectronic materials through periphery engineering. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202201464 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Zeng, W. & Wu, J. Open-shell graphene fragments. Chem7, 358–386 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang, Z. & Zhang, Q. Recent progress in well-defined higher azaacenes (n ≥ 6): synthesis, molecular packing, and applications. Mater. Chem. Front.4, 3419–3432 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dong, S. et al. Extended bis(anthraoxa)quinodimethanes with nine and ten consecutively fused six-membered rings: neutral diradicaloids and charged diradical dianions/dications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 62–66 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Borissov, A. et al. Recent advances in heterocyclic nanographenes and other polycyclic heteroaromatic compounds. Chem. Rev. 122, 565–788 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Richards, G. J. & Hill, J. P. The pyrazinacenes. Acc. Chem. Res.54, 3228–3240 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franceschini, M. et al. peri-Acenoacene ribbons with zigzag BN-doped peripheries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 21470–21484 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Wang, Y. et al. Synthesis and characterization of oxygen-embedded quinoidal pentacene and nonacene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 2169–2176 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Cai, Z., Awais, M. A., Zhang, N. & Yu, L. Exploration of syntheses and functions of higher ladder-type π-conjugated heteroacenes. Chem4, 2538–2570 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bunz, U. H. F. & Freudenberg, J. N‑heteroacenes and N-heteroarenes as N‑nanocarbon segments. Acc. Chem. Res.52, 1575–1587 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miao, Q. Ten years of N-heteropentacenes as semiconductors for organic thin-film transistors. Adv. Mater.26, 5541–5549 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Noda, H., Furutachi, M., Asada, Y., Shibasaki, M. & Kumagai, N. Unique physicochemical and catalytic properties dictated by the B3NO2 ring system. Nat. Chem.9, 571–577 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu, Y. et al. A BN-doped U-shaped heteroacene as a molecular floating gate for ambipolar charge trapping memory. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202303335 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Li, P. et al. New platform of B/N-doped cyclophanes: access to a π-conjugated block-type B3N3 macrocycle with strong dipole moment and unique optoelectronic properties. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202200612 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Ito, M. et al. Fluorescent organic π-radicals stabilized with boron: featuring a SOMO-LUMO electronic transition. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202201965 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Shimoyama, D., Baser-Kirazli, N., Lalancette, R. A. & Jäkle, F. Electrochromic polycationic organoboronium macrocycles with multiple redox states. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.60, 17942–17946 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mützel, C., Farrell, J. M., Shoyama, K. & Würthner, F. 12b,24b-diborahexabenzo[a,c,fg,l,n,qr]pentacene: a low-LUMO boron-doped polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.61, e202115746 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang, J.-J. et al. A modular cascade synthetic strategy toward structurally constrained boron-doped polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 25695–25700 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Lee, J. J. C., Chi, C. & Wu, J. Synthesis of a highly fluorescent Bis(1,4-oxaborine)pentacene. Chempluschem86, 836–839 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farrell, J. M. et al. Tunable low-LUMO boron-doped polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by general one-pot C-H borylations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 9096–9104 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Liu, Y. et al. Photonic modulation enabled by controlling the edge structures of boron‐doped molecular carbons. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202306911 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Guo, J. et al. Diradical B/N‐doped polycyclic hydrocarbons. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202217470 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.von Grotthuss, E., John, A., Kaese, T. & Wagner, M. Doping polycyclic aromatics with boron for superior performance in materials science and catalysis. Asian J. Org. Chem.7, 37–53 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kawashiro, M., Mori, T., Ito, M., Ando, N. & Yamaguchi, S. Photodissociative modules that control dual-emission properties in donor-π-acceptor organoborane fluorophores. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.62, e202303725 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun, W. et al. Ribbon-type boron-doped polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: conformations, dynamic complexation and electronic properties. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202209271 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Oshimizu, R., Ando, N. & Yamaguchi, S. Olefin-borane interactions in donor-π-acceptor fluorophores that undergo frustrated-Lewis-pair-type reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.61, e202209394 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang, X. et al. Electrophilic C-H borylation of aza[5]helicenes leading to bowl-shaped quasi-[7]circulenes with switchable dynamics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 22316–22324 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Mellerup, S. K. & Wang, S. Boron-based stimuli responsive materials. Chem. Soc. Rev.48, 3537–3549 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mukherjee, S. & Thilagar, P. Stimuli and shape responsive ‘boron-containing’ luminescent organic materials. J. Mater. Chem. C.4, 2647–2662 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ito, S., Gon, M., Tanaka, K. & Chujo, Y. Recent developments in stimuli-responsive luminescent polymers composed of boron compounds. Polym. Chem.12, 6372–6380 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen, C. et al. Pushing the length limit of dihydrodiboraacenes: synthesis and characterizations of boron-embedded heptacene and nonacene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202200779 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Jin, T. et al. Exploring structure–property relations of B,S-doped polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons through the trinity of synthesis, spectroscopy, and theory. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 13704–13716 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Kotadiya, N. B., Blom, P. W. M. & Wetzelaer, G.-J. A. H. Efficient and stable single-layer organic lightemitting diodes based on thermally activated delayed fluorescence. Nat. Photon.13, 765–769 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu, T.-L. et al. Diboron compound-based organic light-emitting diodes with high efficiency and reduced efficiency roll-off. Nat. Photon. 12, 235–240 (2018).

- 48.Guo, Y., Chen, C. & Wang, X.-Y. Recent advances in boron-containing acenes: synthesis, properties, and optoelectronic applications. Chin. J. Chem.41, 1355–1373 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barker, J. E., Obi, A. D., Dickie, D. A. & Gilliard, R. J. Jr Boron-doped pentacenes: isolation of crystalline 5,12- and 5,7-diboratapentacene dianions. J. Am. Chem. Soc.145, 2028–2034 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dietz, M. et al. Structure and electronics of a series of CAAC-stabilized diboron-doped acenes from 1,4-diboranaphthalene to 6,13-diborapentacene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 15001–15015 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Metzler, M., Bolte, M., Virovets, A., Lerner, H.-W. & Wagner, M. Vicinal vinylation of boron-doped acenes via heck coupling. Org. Lett.25, 5827–5832 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kirschner, S. et al. How boron doping shapes the optoelectronic properties of canonical and phenylene-containing oligoacenes: a combined experimental and theoretical investigation. Chem. Eur. J. 23, 5104–5116 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Chen, J., Kampf, J. W. & Ashe, A. J. Syntheses and structures of 6,13-dihydro-6,13-diborapentacenes: π-stacking in heterocyclic analogues of pentacene. Organometallics27, 3639–3641 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zettler, F., Hausen, H. D. & Hess, H. Die kristall-und molekülstruktur des triphenylborans. J. Organomet. Chem.72, 157–162 (1974). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Allen, A. D. & Tidwell, T. T. Antiaromaticity in open-shell cyclopropenyl to cycloheptatrienyl cations, anions, free radicals, and radical ions. Chem. Rev.101, 1333–1348 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brynn Hibbert, D. & Thordarson, P. The death of the job plot, transparency, open science and online tools, uncertainty estimation methods and other developments in supramolecular chemistry data analysis. Chem. Commun.52, 12792–12805 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Iida, A., Sekioka, A. & Yamaguchi, S. Heteroarene-fused boroles: what governs the antiaromaticity and Lewis acidity of the borole skeleton? Chem. Sci.3, 1461–1466 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Niu, C. et al. Solvatochromism, reversible chromism and self-assembly effects of heteroatom-assisted aggregation-induced enhanced emission (AIEE) compounds. Chem. Eur. J. 21, 13983–13990 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Han, Y., Zhang, T., Chen, Q., Chen, X. & Xue, P. π-Stacking conversion and enhanced force-stimuli response of a divinylanthracene derivative in a hydrogen-bonded framework. Cryst. Growth Des.21, 1342–1350 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Meng, G. et al. Triazole functionalized 5,9-dioxa-13b-boranaphtho[3,2,1-de]anthracene: a new family of multi-stimuli responsive materials. J. Mater. Chem. C. 8, 7749–7754 (2020).

- 61.Huang, H. et al. Precise molecular design for BN-modified polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons toward mechanochromic materials. J. Mater. Chem.A8, 22023–22031 (2020).

- 62.Hoffend, C. et al. Effects of boron doping on the structural and optoelectronic properties of 9,10-diarylanthracenes. Dalton Trans. 42, 13826–13837 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers 2284558 (TBP), 2220546 (TBH), 2259158 (TBN-Hex), 2220548 (TBN-iPr), and 2331286 (TBP•2pyridine). These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. Synthetic procedures and data, experimental details, photophysical and electrochemical characterizations, and theoretical calculations are provided in the Supplementary Information. Additional data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.