Abstract

Lipids are important skin components that provide, together with proteins, barrier function of the skin. Keratinocyte terminal differentiation launches unique metabolic changes to lipid metabolism that result in the predominance of ceramides within lipids of the stratum corneum (SC)—the very top portion of the skin. Differentiating keratinocytes form unique ceramides that can be found only in the skin, and generate specialized extracellular structures known as lamellae. Lamellae establish tight hydrophobic layers between dying keratinocytes to protect the body from water loss and also from penetration of allergens and bacteria. Genetic and immunological factors may lead to the failure of keratinocyte terminal differentiation and significantly alter the proportion between SC components. The consequence of such changes is loss or deterioration of skin barrier function that can lead to pathological changes in the skin. This review summarizes our current understanding of the role of lipids in skin barrier function. It also draws attention to the utility of testing SC for lipid and protein biomarkers to predict future onset of allergic skin diseases.

Keywords: Lipids, ceramides, skin, keratinocytes, atopic dermatitis, eczema, allergens

INTRODUCTION

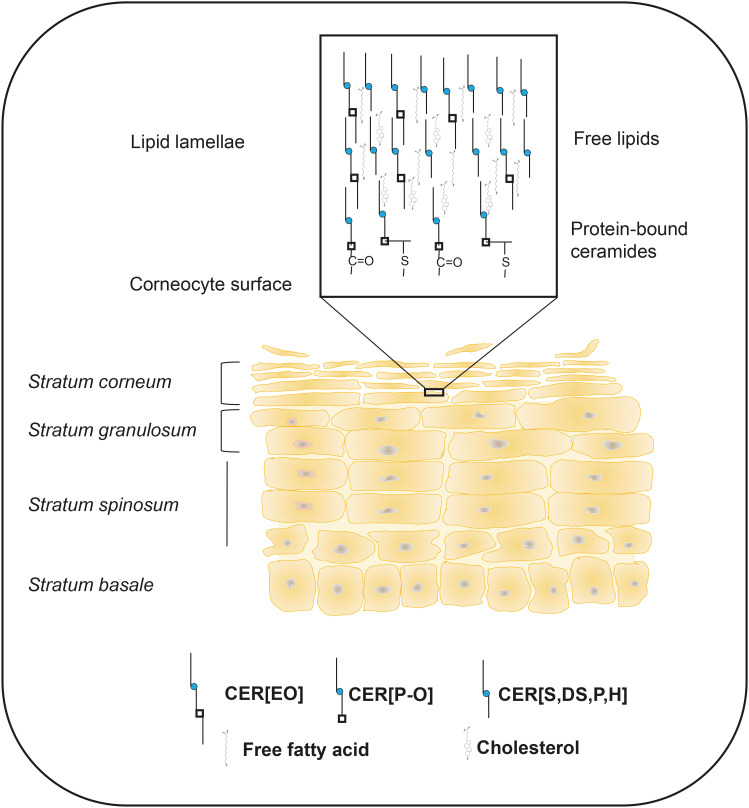

Evolutionary pressures have led life from the marine environment to the “dry” terrestrial land. The conquering of dry environments by animals would have been impossible without the creation of a very specialized organ, the skin, which protects the body from not only water loss but also from the penetration of harmful external elements such as allergens, bacteria, and viruses. To create such a physical barrier, major skin cells, keratinocytes, undergo a program of terminal differentiation that completely changes cellular biochemistry. These changes result in the formation of multiple layers of highly hydrophobic lipid membranes, known as lamellae, which are interspersed among dead cornified keratinocytes (Fig. 1). Changes in keratinocyte lipid biochemistry include the launch of biosynthesis of ultra long-chain, mostly saturated, fatty acids (C28–C36, ULCFA) which are much more hydrophobic and biophysically rigid than the “ordinary” C14–C24 fatty acids (FAs). Differentiating keratinocytes also start to synthesize unique, skin-specific ceramides with ω-hydroxy FAs esterified with linoleic acid (CER[EO]) that are destined in part to be modified, bound to special proteins, and form a scaffold to lay upon free lipids in highly organized fashion. Keratinocyte terminal differentiation functions in tight interaction with cells of the immune system that monitor for “intruders” and initiate specialized immunological responses when such an intrusion happens. When over-activated, the excessive immune response leads to the failure of keratinocytes to terminally differentiate and to form a proper skin barrier. This failure facilitates the penetration of bacteria and allergens deep into skin layers that further propagates immune cell hyperactivation and the loss of skin barrier function. Without resolving immune hyperactivation, this sequence of events leads to physical damage to the skin and to a variety of allergic skin diseases such as eczema (atopic dermatitis, or AD) and psoriasis. These 2 common skin disorders affect millions of people around the globe. This review will focus on the lipid composition of the stratum corneum (SC), lipid metabolism in the skin and its modifications by cytokines, which alters skin barrier function. Additionally, it will examine the unique benefits of skin tape stripping for collecting samples of SC that can be used to study SC components and to look for lipid and protein biomarkers that predict future onset of allergic diseases in early human life.

Fig. 1. Skin stratum corneum as a barrier-forming region in the skin. Skin keratinocytes undergo a program of terminal differentiation as they move from the basal layer towards the skin surface. Special structures, known as lamellae are formed from secreted lipids and are positioned between dying keratinocytes. Part of ceramides becomes chemically bound to the proteins of the cornified envelope and serves as a scaffold upon which free lipids are laid. Multiple layers of cornified cells and lamellae form a tight barrier that protects against water loss and prevents the penetration of allergens, bacteria and viruses into the body.

SC LIPIDS

In skin epidermis, basal cells are constantly dividing and forming new layers of yet undifferentiated keratinocytes. Undifferentiated keratinocytes have a lipid composition similar to other cells in the human body. Their FAs are mostly C16–C24 in carbon chain length, while phospholipids account for about half of the cellular lipids with sphingomyelin (SM), phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylethanolamine, and phosphatidylserine being the major phospholipids present.1 However, the translocation of keratinocytes from basal skin layer towards the surface of the skin initiates cell reprogramming towards terminal differentiation. This metabolic shift is orchestrated by eIF2α kinase GCN2, which leads to the activation of epidermal differentiation complex in chromosome 1q21 and the expression of critical skin barrier proteins such as involucrin, filaggrin, keratins 1 and 10.2,3 Lipid metabolism also dramatically changes during this process. One of the primary hallmarks of SC lipids is the appearance, in the high abundance, of C22–C26 FAs with even longer C28–C34 FAs specifically present in skin ceramides.4,5,6 Another characteristic of FAs in differentiated SC is the prevalence of saturated molecules over monounsaturated ones with virtually no polyunsaturated FAs present. Substantial amounts of α-hydroxy- and odd-chain FAs also appear with differentiation.6 Changes in the FA profile of SC result in an overall increase in hydrophobicity of the skin. The prevalence of saturated molecular species has an important consequence for biophysical properties of the membranes as the increase in hydrophobicity increases membrane rigidity by reducing molecule’s lateral movement and contributes to core skin barrier properties. However, the most unique characteristic of SC lipids is the diversity and abundance of ceramides, which represent half of the lipid pool and are present together with free cholesterol and free FAs in an approximate ratio 2:1:1.1,7,8 The abundance of ceramides is ensured through differentiation-dependent activation of neutral and acid sphingomyelinases and primarily through the activation of β-glucocerebrosidase (GBA1).9 Commensal bacteria, Staphylococcus epidermidis, contribute to free ceramide generation (mostly CER[NS] and CER[AS]) and improving skin barrier by secreting bacterial sphingomyelinase that facilitates SM hydrolysis to ceramides.10 At the same time, the sphingoid bases in ceramides become more diverse due to the activation of the biosynthesis of phytoceramides and 6-hydroxysphingosine-containing ceramides, in addition to the “usual” ceramides that contain sphingosine (Sph) and dihydrosphingosine (DHSph). Moreover, their chain length becomes longer, with C20- and C22-sphingoid bases becoming as abundant or even more abundant than C18-sphingoid bases.11 However, the most unique characteristic of SC ceramides is the biosynthesis of highly hydrophobic and long CER[EO]. These ceramides span in between membrane layers, enforcing a general structure stability, and importantly, CER[OS] are immediate precursors of protein-bound P-OS ceramides (CER[P-O]) that bind to involucrin, forming a scaffold to lay upon free lipids in the lamellae (Fig. 1).12,13,14 Such a complexity and prevalence of ceramides in lipids of SC largely defines its biophysical properties. However, optimal functionality of SC requires all involved elements, including proteins and lipids, to be balanced and properly arranged. Therefore, any change in the proportion of the involved components and in their arrangement may lead to alterations and insufficiency of skin barrier function and the onset of skin pathology/diseases. If present, genetic factors play a major role in skin disease; however, outside of this, it is the immune system that is the main player affecting proper skin barrier function through lipid metabolism and protein expression. As a result of such influence, SC can be considered as a window towards the state of our immune system. This leads to the understanding that SC can be examined and used to identify people at risk of developing allergic skin diseases, get mechanistic indications at potential dysregulation in the immune system, and develop tools for preemptive interventions that can lower the severity of the disease or potentially prevent its onset.

SPHINGOLIPID METABOLISM IN DIFFERENTIATING KERATINOCYTES

FA elongation

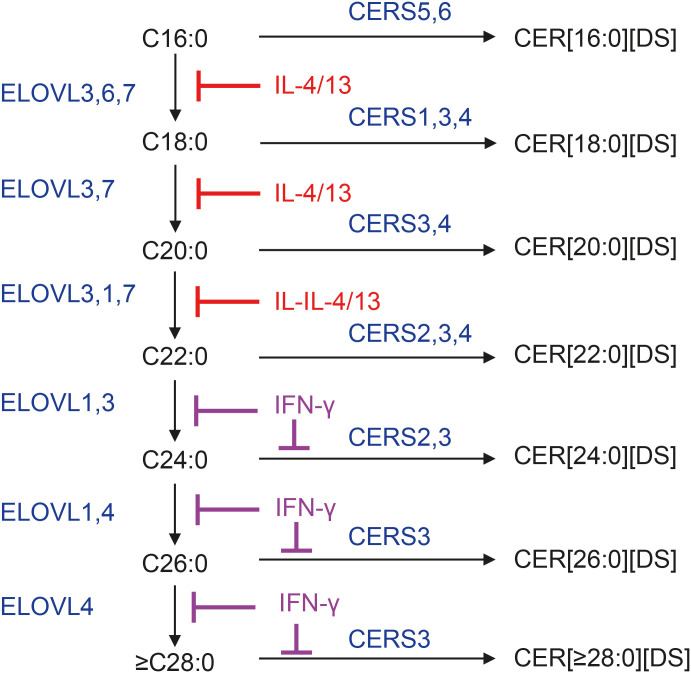

In addition to dietary palmitic acid (C16:0), cytosolic and mitochondrial FA synthases complexes (FAS-I and FAS-II, respectively) form palmitic acid from acetyl-coenzyme A (CoA) and malonyl-CoA. Palmitic acid is the main saturated FA in mammalian tissues and serves as a substrate for further elongation. Seven FA elongases (ELOVL1–7) sequentially operate on the cytosolic part of endoplasmic reticulum to extend FA chain length using FA-CoA and malonyl-CoA. These enzymes form 3-ketoacyl-CoAs as the first step in FA elongation, which occurs in coordination with 3 other enzymes: 3-ketoacyl-CoA reductase, 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase, and trans-2-enoyl-CoA reductase.15,16 The ELOVLs have specificity towards their corresponding substrates. Elongation from C16-FA to C18-FA is ensured by ELOVL6 and ELOVL3, while elongation from C18-FA to C20-FA is performed by ELOVL3 and ELOVL7. ELOVL3 and ELOVL1 convert C20-FA into C22-FA and then to C24-FA. Both ELOVL1 and ELOVL4 can convert C24-FA to C26-FA; however, further elongation, up to C36-FA, is ensured only by ELOVL4 (Fig. 2).17 Mutations in ELOVL4 gene lead to neonatal death.18 All mentioned ELOVL enzymes can work on saturated and monounsaturated FA, but only ELOVL2, 5, and 7 can extend the chain length of polyunsaturated FA.

Fig. 2. FA elongation and incorporation into DSs. FA elongation enzymes ELOVL1–7 sequentially increase fatty acid chain-length by 2 carbons using FA-CoAs and malonyl-CoA. Only ELOVL4 is capable of producing ULCFAs with chain lengths of 28 carbons and above, which are critical for the formation of CER[EO] and CER[P-O]. Elongation of saturated FA is shown in Fig. 2. CER synthases CERS1–6 link FA-CoAs with the amino group of DS to form CER[N,A][DS]. CERS3 is the only enzyme that can incorporate ULCFA-CoA into CER structures. Type 2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-13 block fatty acid elongation by inhibiting the expression of ELOVL3 and ELOVL6, while type 1 cytokine IFN-γ blocks fatty acid elongation by inhibiting ELOVL1 and CERS3. Both types of inhibition lead to the accumulation of short-chain FAs and CERs with short-chain FAs.

FA, fatty acid; ELOVL, fatty acid elongase; CoA, coenzyme A; ULCFA, ultra long-chain fatty acid; CER, ceramide; CERS, ceramide synthase; IL, interleukin; IFN-γ, interferon-γ; DS, dihydrosphingosine.

Serine palmitoyltransferase (SPT) and long-chain/odd-chain sphingoid base formation through phytoceramide metabolism and FA elongation

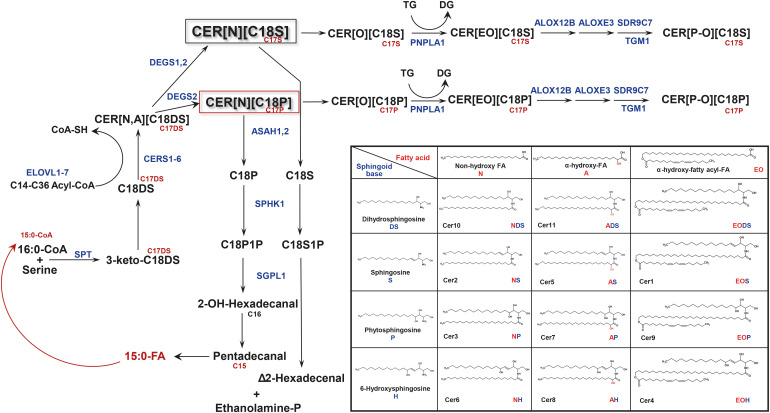

A characteristic property of SC ceramides is the presence of significant amounts of ceramides with C20- and C22-sphingoid bases, as well as sphingoid bases with odd number of carbons. Less known is the fact that SC lipids contain free sphingoid bases of up to C28 carbons, especially as DHSph. The first identification of free C24–C25–C26 DHSphs, published in 1995 by Stewart and Downing,19 demonstrated that these DHSphs comprise a substantial portion of free sphingoid bases in human SC. This observation brings attention to the enzyme SPT, which initiates the biosynthesis of all sphingoid bases by condensing amino acid serine with acyl-CoAs, usually forming C18-sphingoid bases (Fig. 3).16,20

Fig. 3. Sphingolipid turnover and formation of odd-chain sphingoid bases in differentiating keratinocytes. The turnover of sphingolipid metabolites features ceramides CER[NS] and CER[NP] as major hubs in differentiating keratinocytes. Steps involving ceramide glucosylation/deglucosylation and conversion to sphingomyelins are omitted in Fig. 3. Notably, the degradation of CER[NP] into phytosphingosine, followed by its phosphorylation to phytosphingosine-1-phosphate and subsequent degradation by SGPL1, lead to the loss of 3 carbons. This process generates odd-chain fatty acids that re-enter sphingolipid biosynthesis and form odd-chain sphingoid bases (indicated in red). An insert depicts the current classification of skin ceramides, based on combinations of sphingoid base and the type of fatty acid. Cer1–11 in the insert table: denomination of ceramides based on their order during separation by thin-layer chromatography.

ALOXE3, arachidonate lipoxygense 3; ALOX12B, arachidonate 12-lipoxygenase, 12R type; ASAH, N-acyl-sphingosine hydrolase; CER or Cer, ceramide; CERS, ceramide synthase; CoA, coenzyme A; CoA-SH, free coenzyme A; DEGS, dihydroceramide Δ4-desaturase; DG, diacylglycerol; DS, dihydrosphingosine; ELOVL, fatty acid elongase; ethanolamine-P, ethanolamine phosphate; P1P, phytosphingosine-1-phosphate; PNPLA1, patatin-like phosphatase domain-containing-1; SDR9C7, dehydrogenase/reductase family 9C member 7; Sph, sphingosine; SPHK1, sphingosine kinase 1; S1P, sphingosine-1-phosphate; SPT, serine palmitoyltransferase; TG, triacylglycerol; TGM1, transglutaminase 1; SGPL1, sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase 1.

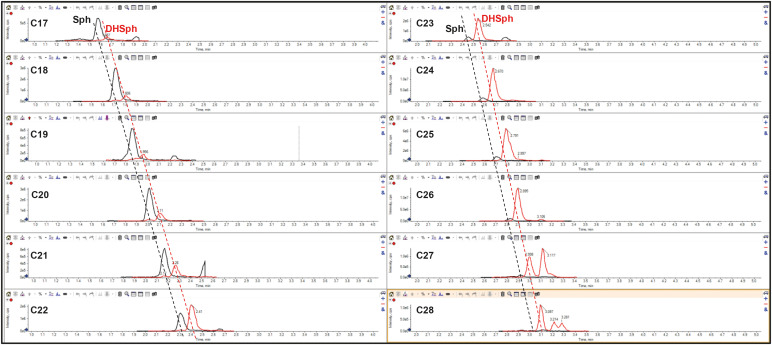

SC lipids also contain a substantial amount of odd-chain FAs, as free FA and N-linked in ceramide molecules.6 Usually, odd-chain FAs are characteristic of bacterial lipids. However, skin surface bacteriome is insufficient to cause such ‘massive contamination,’ especially in deep SC layers. The presence of odd-chain FAs and sphingoid bases suggests that odd-chain FAs may be incorporated into the biosynthesis of sphingoid bases by substituting palmitic acid. This would lead to the formation of odd-chain sphingoid bases. As mentioned above, the presence of free odd-chain sphingoid bases in SC lipids was demonstrated 30 years ago, with C25-DHSph constituting more than 10% of the free Sph-DHSph species, while all odd-chain Sph species accounted for no more than 5%.19 This study also described the unusually high level of C24–C26 DHSphs in human SC, with the lack of corresponding Sph molecules. To ensure the biosynthesis of such long-chain sphigoid bases, SPT must undergo certain changes.

SPT is a multi-subunit enzyme that always contains a catalytic STLC1 subunit, either SPTLC2 or SPTLC3 subunit, and one of 2 small accessory SPTSSA or SPTSSB subunits.21,22 In most tissues, SPT is composed of SPTLC1, SPTLC2, and SPTSSA, which ensures SPT specificity towards palmitoyl-CoA and biosynthesis of C18-sphingoid bases. However, in differentiating keratinocytes, the upregulation of all SPT subunit expression is noticeable that signifies the increase in sphingolipid biosynthesis in general, with the increase in SPTSSB expression being substantially greater than that of SPTSSA.11 A different combinatorial overexpression of all SPT subunits in HEK 293T cells revealed that the presence SPTSSB subunit in SPT complex unlocks broad specificity of SPT towards acyl-CoAs and allows SPT, as a combination of SPTLC1, SPTLC3, and SPTSSB, to generate ceramides with C22- and C24-Sphs.11 Thus, this work explains how differentiating keratinocytes are able to form long-chain sphingoid bases that are more beneficial for lamellae barrier properties from a biophysical point of view (see below). It still remains unexplained whether SPTLC1/3/SPTSSB combination ensures the biosynthesis of free C25–C26 DHSphs,19 or whether an as-yet-unidentified SPT subunit is needed to ensure this reaction. Stewart and Downing19 explained the lack of C24–C26 Sphs by the inability of ceramide synthases (CERSs) to utilize C24–C26 DHSphs for dihydroceramide biosynthesis, resulting in the accumulation of free long-chain DHSphs. In fact, long-chain C24–C28 Sphs and, consequently, corresponding CER[NS] (as they are obligatory immediate precursors for free Sphs) (Fig. 3), are formed but present at very low levels (Fig. 4). This analysis also shows that the ability of CERSs to use long-chain DHSphs for CER[DS] biosynthesis starts to diminish at C21–C22-DHSph and becomes minimal at C26-DHSph (Fig. 4), thus supporting the original assumption by Stewart and Downing.19

Fig. 4. Scheduled MRM profile of free sphingoid bases in stratum corneum lipids. Sphingoid bases (Sph [in black] and DHSph [in red]) are detected through their transition from [M+H]+ to [M+H-H2O]+ ions using liquid chromatography electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Typical MRM profile of Sphs and DHSphs in the stratum corneum of healthy subject is shown (unpublished data). The full chromatography conditions are described in the reference 66. It is important to note the gradual disappearance of free Sphs starting from C23-Sph.

MRM, multiple reaction monitoring; Sph, sphingosine; DHSph, dihydrosphingosine.

Human SC LC-MS/MS analysis of free sphingoid bases, as presented in Fig. 4, also demonstrates a high abundance of odd-chain sphingoid bases, especially that of DHSph. This signifies the involvement of odd-chain acyl-CoAs at the step of 3-keto-DHSph formation. The source of odd-chain FAs in differentiating keratinocytes remained unclear until the elegant work of Kihara’s group.23 The authors used yeast and mammalian cell in vitro systems to demonstrate that C18-phytosphingosine metabolism leads to the production of 15:0-FA (pentadecanoic acid) through the formation of phytosphingosine-1-phosphate, its degradation by Sph-1-phosphate lyase, the generation of 2-hydroxypalmitoyl-CoA and it’s subsequent α-oxidation, while C18-DHSph metabolism results in the formation of hexadecanal and then hexadecanoic (palmitic, 16:0-FA) acid. As a result of such metabolic conversions, even-chain phytoceramides CER[NP][AP] generate odd-chain FAs, which have 3 fewer carbon atoms than the original phytosphingosine in the phytoceramide. These formed odd-chain FAs can be elongated, desaturated, and enter sphingolipid and glycerolipid metabolism. As differentiating keratinocytes actively produce phytoceramides through the action of dihydroceramide desaturase 2 (DEGS2) and are able to incorporate different chain length FAs by SPT, the abundance and phytosphingosine chain-length diversity ensure the formation and incorporation of odd-chain FAs into all ceramide groups present in the SC.

CERSs and desaturases

There are 6 enzymes called CERSs (CERS1–6) that N-link FAs to DHSph (Fig. 3). Each CERS exhibits certain specificity towards acyl-CoAs used in this reaction (for review16). In keratinocytes, CERS5 and CERS6 exhibit specificity towards 16:0-CoA. CERS1 exhibits high specificity towards 18:0- and 18:1-CoAs while CERS4 forms dihydroceramides with 20:0- and 20:1-FA, demonstrating lesser activity with C18-CoA. CERS2 is critical for the formation of dihydroceramides with C22 and C24 FAs. Yet, the most important for skin barrier function CERS is CERS3. It is the only CERS that is able to link ULCFAs (≥ C26) and DHSph thus being unique for the biosynthesis of CER[EOS][EOP]EODS] and protein-bound P-OS,OP,ODS ceramides. Understandably, as those ceramides are critical for a proper lamellae formation, any abnormality in CERS3 expression leads to severe perturbations in skin barrier properties. As an example, disruption of Cers3 in mice is embryonically lethal.24

Desaturation of dihydroceramides by desaturases DEGS1 and DEGS2 is the next step in ceramide de novo biosynthesis (Fig. 3). Both enzymes are able to incorporate a double bond between C4 and C5 of DHSph portion of the molecule by acting as Δ4-desaturase. However, only DEGS2, acting as Δ4-hydroxylase, is able to incorporate additional hydroxy group at C4 of DHSph in CER[NDS] molecule thus forming a phytoceramide (CER[NP]). Furthermore, in DEGS2, the hydroxylase activity prefers CER[DS] with long-chain (C24) vs. shorter chain (C16–C22) FAs.25 It is worth mentioning that in DEGS2-KO mice and DEGS2-KO keratinocytes, CER[NP] as well as their ω-hydroxy homologs are still present at low level suggesting the existence of alternative mechanism(s) of phytoceramide formation.25

CER[EO] and protein-bound ceramides

The hallmark characteristic of SC lipids is the high-level presence of so-called acyl ceramides, CER[EO]. Their role in skin barrier function is so important that any interference with the biosynthesis of CER[EO] leads to serious or even fundamental problems with the skin barrier function. The first prerequisite for the biosynthesis of CER[EO] is the production of ULCFAs (≥ C26), ensured by ELOVL4, whose functional loss leads to neonatal death.18 Then, enzyme CYP4F22 oxidizes the terminal carbon in FAs to form ω-hydroxy ULCFA.26 CYP4F22 is localized in the endoplasmic reticulum and prefers FAs with carbon chain length of 28 or above. After conversion to the acyl-CoA derivative, ω-hydroxy ULCFAs are incorporated into dihydroceramides by CERS3, the only CERSs capable of linking ULCFA-CoA with DHSph to form CER[ODS].24,27 The expression of ELOVL4 and CERS3 is upregulated during keratinocyte differentiation, and CERS3 positively regulates the activity of ELOVL4.28 After desaturation of CER[ODS] by DEGS1 or DEGS2, CER[OS] containing ω-hydroxy ULCFA are esterified at the terminal hydroxyl group by the enzyme PNPLA1 (patatin-like phosphatase domain-containing-1), which transfers linoleic acid from triglycerides to CER[OS], thus forming CER[EOS].29 CER[OH] and CER[OP] can also be used as substrates.30 Such a transfer can also occur after the glycosylation of CER[OS][OH][OP], as glycosylated CER[EO] has also been identified. Notably, ceramide glycosylation is a required step in lamellae granule formation.31

The acylation of CER[O] leads to 2 very important outcomes. The first is the formation of CER[EO] that are highly hydrophobic but also can extend between lipid layers, thus enforcing an overall lamellae structure. However, the most important consequence of CER[EO] formation is their binding to proteins in the cornified envelope through several steps of linoleic acid oxidation. Lipoxygenases ALOX12B and ALOXE3 acting at linoleic acid moiety sequentially transform CER[EO] into epoxy-hydroxy ceramides. Then, enzymatic and non-enzymatic routes of epoxy-hydroxy ceramide transformations lead to the binding of CER[OS] to proteins such as involucrin, periplakin, and desmoplakin. Epoxy-hydrolase 3 is involved in mediating enzymatic pathway, converting epoxy-hydroxy ceramides into trihydroxy derivatives,32 followed by the hydrolysis of trihydroxylinoleic acid by a yet-to-be-identified esterase and binding of the freed CER[O] to glutamine in involucrin and other acceptor proteins. It is suggested that transglutaminase 1 (TGM1) is mediating the final step of the CER[EO] transformations through the enzymatic pathway.33 The non-enzymatic pathway is ensured by the action of dehydrogenase/reductase family 9C member 7, which acts on epoxy-hydroxy ceramide to form epoxy-ketone ceramides.34 Epoxy-ketone derivatives are very reactive and can react with sulfhydryl group of cysteine or amino groups of histidine, serine, lysine, or arginine through Schiff base formation or through Michael addition. However, recent work by Kihara’s group successfully identified only Cys-bound epoxy-enone ceramides in mouse epidermis by mass spectrometry analysis of protease-digested epidermis samples.13 It is proposed that the formation of protein-bound CER[P-O] serves as a scaffold to lay upon free lipids in an organized fashion and properly form lamellae structures in the SC.35

BIOPHYSICAL PROPERTIES OF SKIN LIPIDS

The main purpose of keratinocyte terminal differentiation is to create a physical barrier between ‘wet’ internal and ‘dry’ external environments. The most efficient molecules to create such a barrier are saturated non-polar lipids. The metabolic reprogramming that occurs during differentiation is designed to ensure the elimination of unneeded polar lipid molecules and to upregulate the production of ceramides—the main building blocks of a ‘hydrophobic wall.’ However, merely assembling hydrophobic lipids is not enough to create an efficient barrier; the reprogramming also includes the formation of specialized proteolipid complexes, with filaggrin acting as a central core protein to properly organize the assembly of other proteins, among which involucrin plays a special role. Involucrin is the primary acceptor of protein-bound P-O[S][P][H] ceramides that form a chemically bound hydrophobic layer over mostly hydrophilic proteins, with desmoplakin, envoplakin, and periplakin also identified as binding to P-O ceramides.36,37,38 Such an assembly is initiated in intracellular lamellae granules which also contain newly synthesized ceramides in glycosylated form, cholesterol, and free FAs. Upon fusion with the keratinocyte plasma membrane, lamellae granules release their content into intercellular space and initiate the process of cornified envelope formation through deglycosylation of ceramide molecules and dehydration. This facilitates the reorganization of ceramides into an extended configuration, with hydrocarbon tails pointing in opposite directions, and with cholesterol and free FAs occupying empty space in opposite lipid layers.39,40,41 The sequential release of lamellae granules leads to the formation of multiple lamellae in the space between corneocytes that becomes a foundation for skin barrier function.

An overall increase in the chain length of ceramides in the SC serves a special, barrier-enhancing purpose. It was shown that the decrease in the proportion of long-chain ceramides vs. short-chain ceramides is detrimental for skin barrier function as it leads to an aberrant lipid organization.42 Between N-linked FAs and sphingoid bases, the decrease in the chain length of sphingoid bases seems to be more important. For example, in 10% CER[NS]/palmitoyl-oleoyl-phosphocholine (POPC) bilayer, an incremental decrease from d20:1- to d14:1-Sph in CER[NS] with palmitic acid had a much larger effect on end melting temperature than a decrease in N-linked FA from C20 to C14 in d18:1-based ceramide analogs.43 In 15% CER[NS]/POPC bilayer, an increase in the chain length of sphingoid base from d12:1 to d20:1 in ceramide with N-linked palmitic acid significantly increased the order of POPC bilayer, with d20:1-analog allowing the formation of ceramide-containing gel-phases stronger than d18:1 analog.44 The permeation experiments using artificial SC membrane or porcine skin demonstrated an increase in permeation of theophylline and indomethacin when short chain CER[d12:1-d15:1][2-6:0] were applied to the skin or the artificial membrane.45 Furthermore, the comparison of DHSph-, Sph-, and phytosphingosine-based ceramides revealed that both unsaturation and hydroxylation at C4 of sphingoid base increased membrane permeability properties of ceramide molecule; at the same time, C4-hydroxylation led to the formation of stronger hydrogen bonds and thermostable domains.46 In CER[NS]/cholesterol/free FA/cholesterol sulfate artificial membrane, the replacement of CER[d18:1][24:0] with CER[d18:1][16:0] had a negative impact on membrane structure and led to increased permeability.47 As to the ceramides with 6-hydroxysphingosine, they were found to exert a bimodal effect on skin barrier function. On one side, in comparison to CER[NS][DS][NP], CER[NH] increased permeability to water and lipophilic molecules, but they also decreased permeability to ions and increased thermal stability of the membrane.48 All these studies indicate that skin barrier function requires the presence of ULCFAs and long-chain sphingoid bases to create highly ordered and tightly packed lipid lamellae. Their decrease or shift in balance between different components within lamellae lipids lead to skin barrier dysfunction that is observed in different allergic and inflammation-related skin diseases.49 Mojumdar et al.50 exemplifies the importance of proper proportions between different components of the lamellae lipids. They showed that the lipid barrier properties of an artificial membrane decreased due to a reduced packing density of lipids, which occurred with an increase in the proportion of monounsaturated free FAs.

CAUSATIVE FACTORS AND BIOMEDICAL IMPLICATIONS OF THE FAILING SKIN BARRIER FUNCTION

The failing skin barrier function can lead to very serious consequences. It is hypothesized that the impaired skin barrier in early human life allows allergen penetration through the skin, stimulating excessive production of cytokines by keratinocytes and immune cells.51 This ‘hyperactivation’ of the immune system in the skin may lead to the onset of so-called “atopic march”—a sequential transition of allergic diseases throughout human life, from eczema and food allergy to asthma and allergic rhinitis.52 The underlying causes of such failure are not yet fully understood, but genetic factors and interference of the immune system with keratinocyte terminal differentiation program are the most evident and studied factors.

Mutations in genes critical for CER[P-O] and CER[EO] generation are known to be associated with congenital ichthyosis or dry itchy skin. For instance, congenital ichthyosis is caused by mutations in the CYP4F22 and TGM1 genes.26,33 Nonbullous congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma is associated with mutations in ALOX12B, ALOXE3, and PNPLA1 genes.53,54 Null-mutations in ELOVL1 and ELOVL4 are embryonically lethal,18 and mutations in ALOXE3 or ALOX12B genes lead to neonatal death in mice due to severely impaired barrier function.55,56,57 However, a hyperactivated immune response in the skin has a much broader influence on skin ceramides and skin barrier function that leads to such widespread diseases as eczema, or AD, and psoriasis.

One of the first studies to demonstrate significant abnormalities with SC ceramides in AD was conducted by Imokawa et al.,58 which found a significant reduction in SC ceramides not only in lesional but also in non-lesional skin of AD patients in comparison to healthy controls. The authors noted the decline in all ceramides, but strongest decline was observed for the ceramide 1 (CER[EOS]). Later, their original findings and similar observations by others obtained using thin-layer chromatography were confirmed using mass-spectrometric identification of ceramides,59,60,61 and they also correlated changes in SC lipids with alterations in transepidermal water loss (TEWL).61 It was shown that the decrease in SC ceramides in AD is associated with impaired lamellae lipid organization.62 This group further demonstrated that in AD, there is an increase in the relative proportion of short-chain ceramide species and a decrease in that of long-chain species.42 The reason for this shift towards short-chain ceramide molecular species was later demonstrated to be linked to the action of type 2 cytokines interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13, which are the main drivers of AD, affecting keratinocyte FA biosynthesis.63 It was shown that IL-4/IL-13 interfere with FA elongation by blocking the expression of ELOVL3 and ELOVL6, halting elongation at C16-FA and preventing the synthesis of ULCFAs, despite increased expression of ELOVL1 and ELOVL4 (Fig. 2).64 This block of FA elongation at C16-FA has dramatic consequences for sphingolipid biosynthesis. First, 16:0-CoA becomes more abundant for incorporation into dihydroceramides by CERSs (Fig. 3). Second, the same increase in intracellular C16-FA pool feeds into sphingolipid biosynthesis at the level of SPT (Fig. 3). As a consequence, the absolute amount and relative proportion of CER[16:0/C18S] increase as this molecular species of ceramides receives a ‘double hit’ from the IL-4/IL-13-induced block of FA elongation.64 Third, IL-4/IL-13-induced block of FA elongation has dramatic consequences for the formation of CER[EO] and CER[P-O], as these SC lipids contain only ω-hydroxy ULCFA. Thus, type 2 cytokines impair the formation of CER[EO], their binding to proteins in cornified envelope as CER[P-O], and shorten an overall chain length of ceramide molecules, including their sphingoid bases. The damage caused by excessive type 2 cytokine production in the skin is in fact even more severe because IL-4/IL-13 block the expression of filaggrin, the core protein that controls the assembly of corneodesmosome and, at the end, the entire lamellae organization.65 Therefore, the block of IL-4/IL-13-induced signaling by dupilumab, the antibody to the α-subunit of IL-4 receptor, normalizes ceramide chain length, CER[EOS] production, and TEWL in AD subjects.66

Surprisingly, similar phenotypical changes in SC lipids can be caused by type 1 cytokine interferon-γ (IFN-γ) that is also found to be elevated in AD skin. It was shown that IFN-γ decreases the proportion of the long-chain CER[NS] by inhibiting the expression of ELOVL1 and CERS3, enzymes essential for the biosynthesis of ULCFA and their incorporation into ceramides.67 Although not examined in this study, the described mechanism of IFN-γ action on FA and ceramide biosynthesis likely inhibits the production of CER[EO] and CER[P-O].

Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) was also shown to decrease the level of long-chain free FA and CER[EO] in human skin equivalents.68 However, the exact mechanism of TNF-α interference with skin ceramide metabolism has not been identified.

Thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) is a pleiotropic cytokine released by keratinocytes in response to multiple stimuli, including mechanical stimulation, and is best known for its promotion of type 2 immune response.51,69 Therefore, in vivo, TSLP exerts similar effects on skin lipid metabolism as those attributed to IL-4/IL-13. However, TSLP was recently shown to independently interfere with CER[P-O] biosynthesis by inhibiting the expression of ALOXE3 and ALOX12B enzymes.70 This suggests that therapies targeting IL-4/IL-13 may have limited efficacy in improving CER[P-O] content in the skin of AD patients.

Psoriasis is largely an IL-17-driven disease with hyperproliferative epithelium that forms scaly patches in the affected skin.71 Recent findings indicate that in psoriatic lesions, relative proportion of ULCFA-containing ceramides and free FA as well as the proportion of CER[NP] are decreased.72,73 These changes lower the structural transformation temperature that is characteristic to reduced barrier function. In differentiating keratinocytes, there is a global increase in the biosynthesis of all ceramide subclasses,74 prompting a more detailed investigation into the IL-23/IL-17 signaling pathway and its regulation of keratinocyte metabolism during terminal differentiation.

SC COMPOSITION PREDICTS FUTURE ONSET OF AD

The tight interplay between the immune system and skin barrier supports the hypothesis that skin and SC components can serve as a window into our immune system, particularly as it pertains to skin and allergies. The numerous interactions between cytokines and lipid metabolism could reveal unique cytokine effects detectable in the SC before clinical manifestations of disease appear. This hypothesis is particularly relevant to AD and food allergy, which typically begin early in human life, usually between 6 and 12 months of age. Since the failure of skin barrier function is considered one of the drivers for the onset of exaggerated immune responses and allergen sensitization,75 early detection of AD and food allergy could help in designing preventive strategies to alleviate or even completely prevent these conditions. Possible approaches might include specialized emollients to reinforce the skin barrier or the use of dupilumab (anti-IL4Rα antibody), which is already approved for use from 6 months of age.76 Therefore, there is significant interest in finding such biomarkers. Skin tape stripping offers a minimally invasive approach to collect SC as it is simple and easy enough for use even on newborns.

Using skin-based biomarkers, 3 studies have attempted to predict future onset of AD70,77,78 and one study aimed to predict food allergy79 in 1.5−2 month-old infants with monitoring for the clinical onset of these diseases for up to 2 years. Rinnov et al.77 found a significant decrease in SC content of free phytosphingosine in children who later developed AD when SC samples were collected at 2 months. However, 2 other studies did not confirm this observation.70,78 The methodology used by Rinnov et al.,77 which involved indirect quantitation of ceramide subgroups, complicates the comparison between the studies. Zhang and co-authors78 studied dynamic changes in SC lipids over the first year of life but did not directly assess their observations to predict later development of AD. Furthermore, their data were collected in relative proportion mode rather than performing absolute quantitation, lacking data separation by the sphingoid bases present in each ceramide subgroup. Although they found some differences—such as an increase in monounsaturated FA vs. saturated FA and a small decrease in the relative percent of CER[AS]—between infants with future AD and healthy controls at 42 days, the conflicting nature of the data presents challenges for comparison with other studies. It should be noted that the populations in these studies were distinct, with the Rinnov et al.’s study77 conducted on Danish infants and the Zhang et al.’s study78 on Chinese infants. In a more recent study on Korean infants, SC samples from the inner forearm were collected by tape stripping at the age of 2 months.70 Infants who developed food allergy were excluded from data analysis in this report. Free and protein-bound ceramides as well as SC cytokines were evaluated as potential predictors for the future onset of AD. One of the pronounced differences observed was in the levels of CER[P-O], which significantly declined in infants who later developed AD. In contrast, levels of unsaturated SMs (24:1-SM and 26:1-SM) and short-chain CER[AS] as well as the ratio of short-chain and long-chain CER[NC18S] were elevated in children with future AD. TSLP and IL-13 levels were also significantly increased in the SC of infants who later developed AD. This confirmed earlier findings that reported elevation of TSLP in the SC collected at 2 months of age in infants who later developed AD.80 A combination of factors−family history for allergic diseases, CER[P-O], 26:1-SM and IL-13 or TSLP−provided strong predicting power, with the odds ratio reaching above 50.70 Furthermore, in vitro investigations exploring the mechanisms leading to the decrease in CER[P-O] in the SC of infants with future AD revealed that TSLP could block the expression of lipoxygenases ALOX12B and ALOXE3 that are required to prepare CER[EO] for protein binding in the cornified envelope.70

In a separate analysis within the same birth cohort of Korean infants, a surprising difference was found between the biomarkers predicting future AD and future food allergy.79 In particular, infants who later developed food allergy alone did not exhibit decreased levels of CER[P-O]. On the contrary, these infants showed increased levels of CER[P-O], while those who developed both food allergy and AD exhibited no change in CER[P-O] level, in contrast to the decrease observed in infants who later developed only AD. In addition, infants with future onset of food allergy alone did not show an increase in unsaturated SMs but did exhibit increased levels of unsaturated CER[NS]. Interestingly, the concomitant development of food allergy and AD negated the association usually seen between unsaturated SM and the future onset of AD.

The SC cytokine analysis in this study provided very important clues regarding possible associations between changes in cytokines and SC lipids. TSLP levels were increased in infants who later developed AD or both AD and food allergy, but not in those who developed food allergy alone. On the contrary, IL-33 levels were elevated in infants with future food allergy alone or food allergy with AD, but not in those with future AD alone. This suggests a unique link: TSLP with AD, and IL-33 with food allergy. TNF-α, IL-13, and microphage-derived chemokine levels were increased in all allergic groups, and their combination with IL-33 and unsaturated CER[NS] in the prediction model gave rise to outstanding odds ratios up to 101 for predicting food allergy.79

Research for predictive biomarkers for the future onset of allergic diseases in infancy is still in its early stages. The observed findings must be verified across different ethnicities and regions. However, it is evident that SC samples collected via minimally invasive skin tape stripping provide a powerful tool for predicting the early onset of allergic diseases when cytokines, lipids, and proteins are analyzed. This approach could lead to the development of preventive strategies aimed at mitigating or even halting the onset of allergic diseases.

CONCLUSION

Lipids are important skin components that ensure the barrier function of the skin. Keratinocyte terminal differentiation launches unique metabolic changes in lipid metabolism, resulting in the predominance of ceramides within lipids of the SC. Differentiating keratinocytes form unique ceramides and generate specialized extracellular structures known as lamellae that are positioned between corneocytes. Part of the ceramides becomes chemically bound to the proteins of the cornified envelope and serves as a scaffold upon which free lipids are laid. Multiple layers of cornified cells and lamellae form a tight barrier that protects against water loss and prevents the penetration of allergens, bacteria and viruses into the body. Hyperactivated immune response in the skin perturbs keratinocyte lipid metabolism and diminishes skin barrier properties. A full understanding of the relationship between immune system, keratinocyte terminal differentiation and lipid metabolism is required to develop the use of SC lipids as a tool to diagnose the future onset of allergic skin diseases or to monitor the efficacy of therapeutic interventions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author thanks Dr. Doug Bibus for helpful suggestions during preparation of this manuscript. This work was in part funded by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants 5UM1AI130780, 1UM1AI151958, 1U01AI152037, and 1UM1TR004399.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The author has research grants and contracts from Sanofi-Genzyme and from LEO Pharma.

References

- 1.Lampe MA, Williams ML, Elias PM. Human epidermal lipids: characterization and modulations during differentiation. J Lipid Res. 1983;24:131–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collier AE, Wek RC, Spandau DF. Human keratinocyte differentiation requires translational control by the eIF2α kinase GCN2. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:1924–1934. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abhishek S, Palamadai Krishnan S. Epidermal differentiation complex: a review on its epigenetic regulation and potential drug targets. Cell J. 2016;18:1–6. doi: 10.22074/cellj.2016.3980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nicollier M, Massengo T, Rémy-Martin JP, Laurent R, Adessi GL. Free fatty acids and fatty acids of triacylglycerols in normal and hyperkeratotic human stratum corneum. J Invest Dermatol. 1986;87:68–71. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12523574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laffet GP, Genette A, Gamboa B, Auroy V, Voegel JJ. Determination of fatty acid and sphingoid base composition of eleven ceramide subclasses in stratum corneum by UHPLC/scheduled-MRM. Metabolomics. 2018;14:69. doi: 10.1007/s11306-018-1366-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Smeden J, Janssens M, Kaye EC, Caspers PJ, Lavrijsen AP, Vreeken RJ, et al. The importance of free fatty acid chain length for the skin barrier function in atopic eczema patients. Exp Dermatol. 2014;23:45–52. doi: 10.1111/exd.12293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lampe MA, Burlingame AL, Whitney J, Williams ML, Brown BE, Roitman E, et al. Human stratum corneum lipids: characterization and regional variations. J Lipid Res. 1983;24:120–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elias PM, Gruber R, Crumrine D, Menon G, Williams ML, Wakefield JS, et al. Formation and functions of the corneocyte lipid envelope (CLE) Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1841:314–318. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2013.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holleran WM, Ginns EI, Menon GK, Grundmann JU, Fartasch M, McKinney CE, et al. Consequences of beta-glucocerebrosidase deficiency in epidermis. Ultrastructure and permeability barrier alterations in Gaucher disease. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:1756–1764. doi: 10.1172/JCI117160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zheng Y, Hunt RL, Villaruz AE, Fisher EL, Liu R, Liu Q, et al. Commensal Staphylococcus epidermidis contributes to skin barrier homeostasis by generating protective ceramides. Cell Host Microbe. 2022;30:301–313.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2022.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzuki M, Ohno Y, Kihara A. Whole picture of human stratum corneum ceramides, including the chain-length diversity of long-chain bases. J Lipid Res. 2022;63:100235. doi: 10.1016/j.jlr.2022.100235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krieg P, Fürstenberger G. The role of lipoxygenases in epidermis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1841:390–400. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohno Y, Nakamura T, Iwasaki T, Katsuyama A, Ichikawa S, Kihara A. Determining the structure of protein-bound ceramides, essential lipids for skin barrier function. iScience. 2023;26:108248. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2023.108248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirabayashi T, Murakami M, Kihara A. The role of PNPLA1 in ω-O-acylceramide synthesis and skin barrier function. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2019;1864:869–879. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2018.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kihara A. Very long-chain fatty acids: elongation, physiology and related disorders. J Biochem. 2012;152:387–395. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvs105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kihara A. Synthesis and degradation pathways, functions, and pathology of ceramides and epidermal acylceramides. Prog Lipid Res. 2016;63:50–69. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sassa T, Kihara A. Metabolism of very long-chain fatty acids: genes and pathophysiology. Biomol Ther (Seoul) 2014;22:83–92. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2014.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vasireddy V, Uchida Y, Salem N, Jr, Kim SY, Mandal MN, Reddy GB, et al. Loss of functional ELOVL4 depletes very long-chain fatty acids (> or =C28) and the unique omega-O-acylceramides in skin leading to neonatal death. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:471–482. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stewart ME, Downing DT. Free sphingosines of human skin include 6-hydroxysphingosine and unusually long-chain dihydrosphingosines. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;105:613–618. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12323736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linn SC, Kim HS, Keane EM, Andras LM, Wang E, Merrill AH., Jr Regulation of de novo sphingolipid biosynthesis and the toxic consequences of its disruption. Biochem Soc Trans. 2001;29:831–835. doi: 10.1042/0300-5127:0290831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanada K. Serine palmitoyltransferase, a key enzyme of sphingolipid metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1632:16–30. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(03)00059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han G, Gupta SD, Gable K, Niranjanakumari S, Moitra P, Eichler F, et al. Identification of small subunits of mammalian serine palmitoyltransferase that confer distinct acyl-CoA substrate specificities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:8186–8191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811269106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kondo N, Ohno Y, Yamagata M, Obara T, Seki N, Kitamura T, et al. Identification of the phytosphingosine metabolic pathway leading to odd-numbered fatty acids. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5338. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jennemann R, Rabionet M, Gorgas K, Epstein S, Dalpke A, Rothermel U, et al. Loss of ceramide synthase 3 causes lethal skin barrier disruption. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:586–608. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ota A, Morita H, Naganuma T, Miyamoto M, Jojima K, Nojiri K, et al. Bifunctional DEGS2 has higher hydroxylase activity toward substrates with very-long-chain fatty acids in the production of phytosphingosine ceramides. J Biol Chem. 2023;299:104603. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2023.104603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohno Y, Nakamichi S, Ohkuni A, Kamiyama N, Naoe A, Tsujimura H, et al. Essential role of the cytochrome P450 CYP4F22 in the production of acylceramide, the key lipid for skin permeability barrier formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:7707–7712. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503491112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sassa T, Ohno Y, Suzuki S, Nomura T, Nishioka C, Kashiwagi T, et al. Impaired epidermal permeability barrier in mice lacking elovl1, the gene responsible for very-long-chain fatty acid production. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33:2787–2796. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00192-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mizutani Y, Sun H, Ohno Y, Sassa T, Wakashima T, Obara M, et al. Cooperative synthesis of ultra long-chain fatty acid and ceramide during keratinocyte differentiation. PLoS One. 2013;8:e67317. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hirabayashi T, Anjo T, Kaneko A, Senoo Y, Shibata A, Takama H, et al. PNPLA1 has a crucial role in skin barrier function by directing acylceramide biosynthesis. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14609. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Masukawa Y, Narita H, Sato H, Naoe A, Kondo N, Sugai Y, et al. Comprehensive quantification of ceramide species in human stratum corneum. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:1708–1719. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D800055-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akiyama M. Corneocyte lipid envelope (CLE), the key structure for skin barrier function and ichthyosis pathogenesis. J Dermatol Sci. 2017;88:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Edin ML, Yamanashi H, Boeglin WE, Graves JP, DeGraff LM, Lih FB, et al. Epoxide hydrolase 3 (Ephx3) gene disruption reduces ceramide linoleate epoxide hydrolysis and impairs skin barrier function. J Biol Chem. 2021;296:100198. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA120.016570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang H, Ericsson M, Weström S, Vahlquist A, Virtanen M, Törmä H. Patients with congenital ichthyosis and TGM1 mutations overexpress other ARCI genes in the skin: part of a barrier repair response? Exp Dermatol. 2019;28:1164–1171. doi: 10.1111/exd.13813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takeichi T, Hirabayashi T, Miyasaka Y, Kawamoto A, Okuno Y, Taguchi S, et al. SDR9C7 catalyzes critical dehydrogenation of acylceramides for skin barrier formation. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:890–903. doi: 10.1172/JCI130675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Breiden B, Sandhoff K. The role of sphingolipid metabolism in cutaneous permeability barrier formation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1841:441–452. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2013.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marekov LN, Steinert PM. Ceramides are bound to structural proteins of the human foreskin epidermal cornified cell envelope. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:17763–17770. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.28.17763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nemes Z, Marekov LN, Steinert PM. Involucrin cross-linking by transglutaminase 1. Binding to membranes directs residue specificity. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:11013–11021. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.11013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nemes Z, Marekov LN, Fésüs L, Steinert PM. A novel function for transglutaminase 1: attachment of long-chain ω-hydroxyceramides to involucrin by ester bond formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:8402–8407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wennberg CL, Narangifard A, Lundborg M, Norlén L, Lindahl E. Structural transitions in ceramide cubic phases during formation of the human skin barrier. Biophys J. 2018;114:1116–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.12.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Norlén L, Lundborg M, Wennberg C, Narangifard A, Daneholt B. The skin’s barrier: a cryo-EM based overview of its architecture and stepwise formation. J Invest Dermatol. 2022;142:285–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2021.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmitt T, Neubert RH. State of the art in stratum corneum research. Part II: hypothetical stratum corneum lipid matrix models. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2020;33:213–230. doi: 10.1159/000509019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Janssens M, van Smeden J, Gooris GS, Bras W, Portale G, Caspers PJ, et al. Increase in short-chain ceramides correlates with an altered lipid organization and decreased barrier function in atopic eczema patients. J Lipid Res. 2012;53:2755–2766. doi: 10.1194/jlr.P030338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Al Sazzad MA, Yasuda T, Murata M, Slotte JP. The long-chain sphingoid base of ceramides determines their propensity for lateral segregation. Biophys J. 2017;112:976–983. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maula T, Artetxe I, Grandell PM, Slotte JP. Importance of the sphingoid base length for the membrane properties of ceramides. Biophys J. 2012;103:1870–1879. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Školová B, Janůšová B, Vávrová K. Ceramides with a pentadecasphingosine chain and short acyls have strong permeabilization effects on skin and model lipid membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1858:220–232. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Školová B, Kováčik A, Tesař O, Opálka L, Vávrová K. Phytosphingosine, sphingosine and dihydrosphingosine ceramides in model skin lipid membranes: permeability and biophysics. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr. 2017;1859:824–834. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2017.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pullmannová P, Pavlíková L, Kováčik A, Sochorová M, Školová B, Slepička P, et al. Permeability and microstructure of model stratum corneum lipid membranes containing ceramides with long (C16) and very long (C24) acyl chains. Biophys Chem. 2017;224:20–31. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kováčik A, Šilarová M, Pullmannová P, Maixner J, Vávrová K. Effects of 6-hydroxyceramides on the thermotropic phase behavior and permeability of model skin lipid membranes. Langmuir. 2017;33:2890–2899. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.7b00184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Joo KM, Hwang JH, Bae S, Nahm DH, Park HS, Ye YM, et al. Relationship of ceramide-, and free fatty acid-cholesterol ratios in the stratum corneum with skin barrier function of normal, atopic dermatitis lesional and non-lesional skins. J Dermatol Sci. 2015;77:71–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mojumdar EH, Helder RW, Gooris GS, Bouwstra JA. Monounsaturated fatty acids reduce the barrier of stratum corneum lipid membranes by enhancing the formation of a hexagonal lateral packing. Langmuir. 2014;30:6534–6543. doi: 10.1021/la500972w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leung DY, Berdyshev E, Goleva E. Cutaneous barrier dysfunction in allergic diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145:1485–1497. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Davidson WF, Leung DY, Beck LA, Berin CM, Boguniewicz M, Busse WW, et al. Report from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases workshop on “atopic dermatitis and the atopic march: mechanisms and interventions”. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143:894–913. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eckl KM, de Juanes S, Kurtenbach J, Nätebus M, Lugassy J, Oji V, et al. Molecular analysis of 250 patients with autosomal recessive congenital ichthyosis: evidence for mutation hotspots in ALOXE3 and allelic heterogeneity in ALOX12B. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1421–1428. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nohara T, Ohno Y, Kihara A. Impaired production of skin barrier lipid acylceramides and abnormal localization of PNPLA1 due to ichthyosis-causing mutations in PNPLA1. J Dermatol Sci. 2022;107:89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2022.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Epp N, Fürstenberger G, Müller K, de Juanes S, Leitges M, Hausser I, et al. 12R-lipoxygenase deficiency disrupts epidermal barrier function. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:173–182. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200612116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moran JL, Qiu H, Turbe-Doan A, Yun Y, Boeglin WE, Brash AR, et al. A mouse mutation in the 12R-lipoxygenase, Alox12b, disrupts formation of the epidermal permeability barrier. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:1893–1897. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Krieg P, Rosenberger S, de Juanes S, Latzko S, Hou J, Dick A, et al. Aloxe3 knockout mice reveal a function of epidermal lipoxygenase-3 as hepoxilin synthase and its pivotal role in barrier formation. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:172–180. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Imokawa G, Abe A, Jin K, Higaki Y, Kawashima M, Hidano A. Decreased level of ceramides in stratum corneum of atopic dermatitis: an etiologic factor in atopic dry skin? J Invest Dermatol. 1991;96:523–526. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12470233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Di Nardo A, Wertz P, Giannetti A, Seidenari S. Ceramide and cholesterol composition of the skin of patients with atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:27–30. doi: 10.1080/00015559850135788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Farwanah H, Raith K, Neubert RH, Wohlrab J. Ceramide profiles of the uninvolved skin in atopic dermatitis and psoriasis are comparable to those of healthy skin. Arch Dermatol Res. 2005;296:514–521. doi: 10.1007/s00403-005-0551-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ishikawa J, Narita H, Kondo N, Hotta M, Takagi Y, Masukawa Y, et al. Changes in the ceramide profile of atopic dermatitis patients. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:2511–2514. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Janssens M, van Smeden J, Gooris GS, Bras W, Portale G, Caspers PJ, et al. Lamellar lipid organization and ceramide composition in the stratum corneum of patients with atopic eczema. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:2136–2138. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hassoun D, Malard O, Barbarot S, Magnan A, Colas L. Type 2 immunity-driven diseases: towards a multidisciplinary approach. Clin Exp Allergy. 2021;51:1538–1552. doi: 10.1111/cea.14029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Berdyshev E, Goleva E, Bronova I, Dyjack N, Rios C, Jung J, et al. Lipid abnormalities in atopic skin are driven by type 2 cytokines. JCI Insight. 2018;3:e98006. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.98006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Howell MD, Kim BE, Gao P, Grant AV, Boguniewicz M, Debenedetto A, et al. Cytokine modulation of atopic dermatitis filaggrin skin expression. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Berdyshev E, Goleva E, Bissonnette R, Bronova I, Bronoff AS, Richers BN, et al. Dupilumab significantly improves skin barrier function in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Allergy. 2022;77:3388–3397. doi: 10.1111/all.15432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tawada C, Kanoh H, Nakamura M, Mizutani Y, Fujisawa T, Banno Y, et al. Interferon-γ decreases ceramides with long-chain fatty acids: possible involvement in atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:712–718. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Danso MO, van Drongelen V, Mulder A, van Esch J, Scott H, van Smeden J, et al. TNF-α and Th2 cytokines induce atopic dermatitis-like features on epidermal differentiation proteins and stratum corneum lipids in human skin equivalents. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1941–1950. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ebina-Shibuya R, Leonard WJ. Role of thymic stromal lymphopoietin in allergy and beyond. Nat Rev Immunol. 2023;23:24–37. doi: 10.1038/s41577-022-00735-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Berdyshev E, Kim J, Kim BE, Goleva E, Lyubchenko T, Bronova I, et al. Stratum corneum lipid and cytokine biomarkers at age 2 months predict the future onset of atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2023;151:1307–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2023.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mosca M, Hong J, Hadeler E, Hakimi M, Liao W, Bhutani T. The role of IL-17 cytokines in psoriasis. ImmunoTargets Ther. 2021;10:409–418. doi: 10.2147/ITT.S240891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Uchino T, Kamiya D, Yagi H, Fujino-Shimaya H, Hatta I, Fujimori S, et al. Comparative analysis of intercellular lipid organization and composition between psoriatic and healthy stratum corneum. Chem Phys Lipids. 2023;254:105305. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2023.105305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yokose U, Ishikawa J, Morokuma Y, Naoe A, Inoue Y, Yasuda Y, et al. The ceramide [NP]/[NS] ratio in the stratum corneum is a potential marker for skin properties and epidermal differentiation. BMC Dermatol. 2020;20:6. doi: 10.1186/s12895-020-00102-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Goleva E, Berdyshev E, Bronova I, Hall CF, Richers BN, Leung DY. Th2 cytokines and IL-17 have distinct effects on sphingolipid metabolism in differentiated primary human keratinocytes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:AB272. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Marques-Mejias A, Bartha I, Ciaccio CE, Chinthrajah RS, Chan S, Hershey GKK, et al. Skin as the target for allergy prevention and treatment. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2024;133:133–143. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2023.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Müller S, Maintz L, Bieber T. Treatment of atopic dermatitis: recently approved drugs and advanced clinical development programs. Allergy. 2024;79:1501–1515. doi: 10.1111/all.16009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rinnov MR, Halling AS, Gerner T, Ravn NH, Knudgaard MH, Trautner S, et al. Skin biomarkers predict development of atopic dermatitis in infancy. Allergy. 2023;78:791–802. doi: 10.1111/all.15518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhang Y, Gu H, Ye Y, Li Y, Gao X, Ken K, et al. Trajectory of stratum corneum lipid subclasses in the first year of life and associations with atopic dermatitis: a prospective cohort study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2023;34:e14045. doi: 10.1111/pai.14045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Berdyshev E, Kim J, Kim BE, Goleva E, Lyubchenko T, Bronova I, et al. Skin biomarkers predict the development of food allergy in early life. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2024;153:1456–1463.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2024.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kim J, Kim BE, Lee J, Han Y, Jun HY, Kim H, et al. Epidermal thymic stromal lymphopoietin predicts the development of atopic dermatitis during infancy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:1282–1285.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.12.1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]