Abstract

CPX-351 is a liposomal formulation of cytarabine/daunorubicin with a 5:1 fixed molar ratio. We investigated the safety and efficacy of escalating doses of CPX-351 in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) at high risk of induction mortality with standard chemotherapy determined through assessment of leukemia and patient-related risk factors for intensive chemotherapy in an open-label, phase II trial. Patients were randomized to receive 50 or 75 units/m2 on days 1, 3 and 5. Once safety was established, a 100 units/m2 arm was opened. Fifty-six patients were enrolled, 16, 24 and 16 in the 50, 75, and 100 units/m2 arms, respectively. The composite complete remission rate (complete remission + complete remission with incomplete blood count recovery) was lowest with 50 units/m2 (19%) compared to 75 units/m2 (38%) and 100 units/m2 (44%) (P=0.35). The 50 units/m2 arm had a median overall survival of 4.3 months, compared to 8.6 and 6.2 months for the 75 and 100 units/m2 respectively (P=0.04). Non-hematologic grade 3/4 treatment-emergent adverse events included febrile neutropenia (34%), pneumonia (23%), and sepsis (16%). CPX-351 at 75 units/m2 has favorable safety and efficacy for AML patients at high risk of induction mortality with some tolerating the standard dose of 100 units/m2.

Introduction

Treatment of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with standard chemotherapy in older patients or those with significant co-morbidities remains a challenge. Low response rates and high risk of complications or treatment-related death are common features in such patients (1). Furthermore, AML evolving from an antecedent hematological malignancy (secondary AML or s-AML) or as a complication of previous chemotherapy or radiation (therapy-related AML or t-AML) are more frequently seen in older patients (2). These AML subsets are inherently resistant to standard therapy as they are frequently associated with adverse risk cytogenetics and multidrug resistance (3, 4). Older patients with poor performance status or with poor organ function are frequently excluded from clinical trials and thus have few available treatment options (5). Dose reduction of standard treatment in order to mitigate those risks could also compromise treatment efficacy (6).

CPX-351 (VYXEOS; Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Paolo Alto, CA) is a liposomal formulation of cytarabine and daunorubicin in a fixed 5:1 molar ratio (7–9). Preclinical studies have shown preferential delivery of this drug formulation into leukemia cells compared to normal bone marrow cells, providing enhanced killing of leukemia cells (7). CPX-351 at the dose of 100 units/m2 has been recently approved for treatment of adults of any age with newly diagnosed t-AML or AML with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS)-related changes. Treatment with CPX-351 in such patients with ages 60 to 75 years produced improved overall survival compared to 7+3 in a randomized phase III study (10). The safety and efficacy of CPX-351 for treatment of AML in patients considered at high risk of induction mortality with intensive chemotherapy regardless of an age limit has not been explored given that these patients were not included in the randomized phase III trial. We designed a phase II, open-label trial exploring escalating doses of CPX-351 to investigate safety and efficacy in such patients.

Methods

Patients

Eligible patients were adults with newly diagnosed AML (≥20% myeloblasts) except acute promyelocytic leukemia, who were predicted to be at high risk for induction mortality based on previously described risk factors (5). For this purpose, every patient had to have at least one of the following leukemia-specific risk factors: adverse cytogenetics according to the European LeukemiaNet risk stratification, sAML, tAML, or AML with MDS-related changes (11). Patients with an age <60 years were required to have at least one patient-related risk factor in addition to the required leukemia-specific risk factor. Patient risk factors included Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) 2–3, serum creatinine between 1.3 and 2.0 mg/dL, or age ≥70 years. Other inclusion criteria included serum creatinine ≤2.0 mg/dL, and adequate hepatic [serum bilirubin ≤2.0 mg/dL; serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) <3x upper limit of normal (ULN), unless deemed disease related, where ALT could be <5x ULN] and cardiac functions (ejection fraction or EF ≥50%). Patients with uncontrolled infections, active central nervous system (CNS) leukemia or uncontrolled intercurrent illness were excluded.

The study was approved by the MD Anderson Cancer Center institutional review board. All patients provided informed consent according to institutional guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study Design and Treatment

This was a single-center, open-label, randomized phase 2 trial (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT02286726). Patients enrolled on the initial part of the study were randomized with a 1:1 ratio to a starting dose of 50 units/m2 or 75 units/m2 (with 1 unit equivalent to 1 mg cytarabine and 0.44 mg of daunorubicin) (12). If both dose schedules were found to have acceptable safety, the 75 units/m2 cohort was to be expanded, and if safety confirmed, a third cohort was to be opened with a starting dose of 100 units/m2. Acceptable safety was assessed based on the toxicity during the first cycle, and was defined as a dose limiting toxicity (DLT) rate of <33%. DLT was defined as either induction mortality (death occurring during the first 60 days from start of study therapy), grade 3–4 non-hematologic toxicity, or a dose-limiting hematologic toxicity (defined as bone marrow and peripheral blood examination at day ≥ 56 showing absence of detectable leukemia, persistent hypocellular bone marrow, and neutrophils <0.5 ×109/L and/or platelets <10 ×109/L) at least possibly related to the study drug, all occurring during the first 60 days from the start of the first cycle of therapy.

CPX-351 was given during induction on days 1, 3 and 5 as a 90-minute infusion. A second induction course was allowed for patients who did not achieve blasts ≤5% on day 28 bone marrow assessment. The second induction course consisted of the same dose administered in cycle 1, given on days 1 and 3. For patients in complete remission (CR) or complete remission with incomplete blood count recovery (CRi) after 1 or 2 induction cycles, consolidation was given at a dose of 65 units/m2 on days 1 and 3 for up to 4 cycles. Delay in consolidation treatment start was allowed, and subsequent start dates were adjusted based on time to response and time to count recovery. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) was performed at the discretion of the treating physician.

Assessments

The primary objective of this study was to determine efficacy, with the primary endpoint being the rate of CR/CRi, of escalating CPX-351 doses in patients at high risk of induction mortality. Responses were defined according to the 2017 European LeukemiaNet (ELN) recommendations (11). Secondary endpoints included rate of DLTs, induction mortality (by day 60), and description of the safety profile of the different dose levels. Other endpoints included event-free survival (EFS), defined as time from treatment start to treatment failure, relapse or death, whichever came first, and overall survival (OS), defined as time from treatment start to death from any cause. Complete remission duration (CRD) was defined as time from achievement of CR/CRi to relapse. Measurable residual disease (MRD) was determined using multi-parameter flow cytometry on bone marrow samples at the time of remission following induction, as previously described (13). Mutation status was assessed using targeted, next-generation sequencing panels, including genes recurrently mutated in hematologic malignancies (14).

Statistical Analyses

The planned sample size for the 50 and 75 units/m2 dose arms was 15 patients equally randomized per arm. One additional patient was erroneously randomized to the 50 units/m2 dose arm. This sample size would give the trial 87% power to test the difference between the null hypothesis (CR/CRi ≤5%) and the alternative hypothesis (CR/CRi of 30% or greater) at a one-sided type I error of 0.05, achieved independently in these dose arms. The study monitored futility and toxicity using a Bayesian method, and the monitoring rules were applied to each arm separately (15). Specifically, if at any time during the study, it was determined that there was a greater than 95% chance that the response rate was less likely to improve by 25% than the null hypothesis in one arm, enrollment on that arm would be terminated. Categorical variables were compared using the Fisher Exact Test, and continuous variables were compared using the Kruskal-Wallis test. The distributions of EFS and OS were calculated by the Kaplan Meier method, and were compared by the log-rank test. The data analyses were done with GraphPad Prism version 6 and SAS v9.4 (SAS institute Inc., Cary NC).

Results

Patient Population

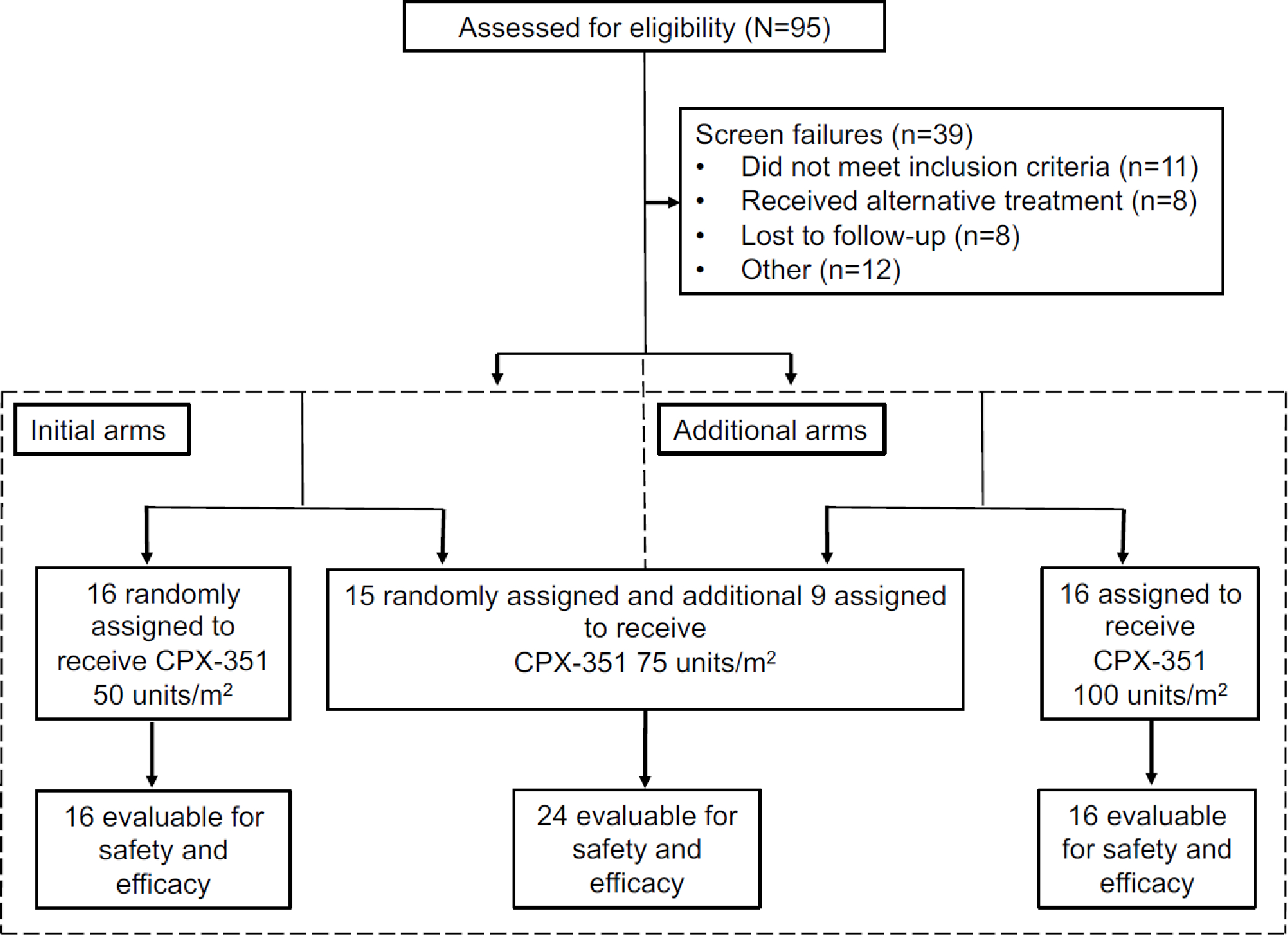

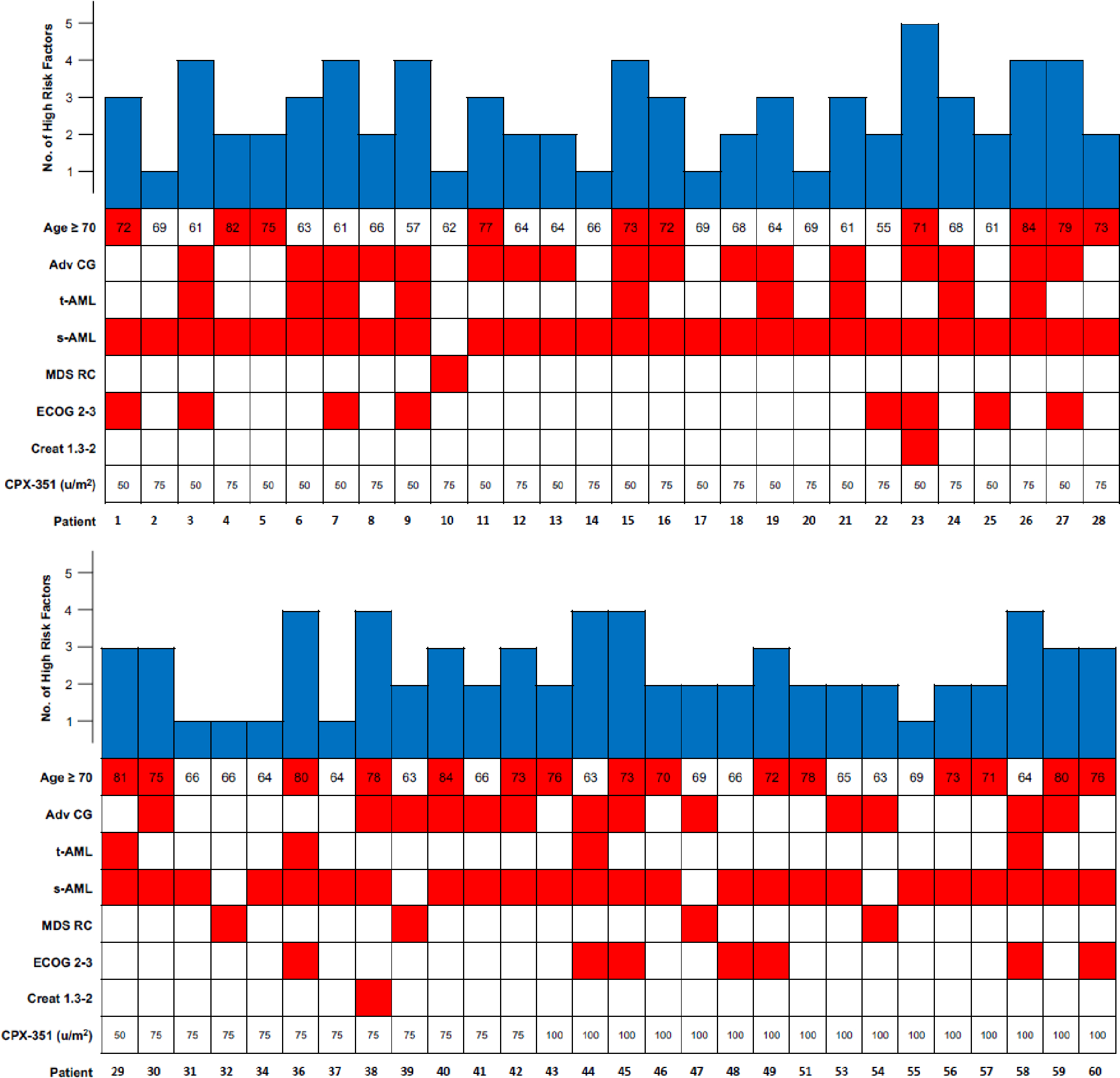

Between June 4, 2015 and December 11, 2018, a total of 56 patients were enrolled. During the initial randomized portion of the study, 16 patients were randomized to the 50 units/m2 cohort, and 15 to the 75 units/m2 cohort (Figure 1). Once safety and efficacy were established in both arms, the 75 units/m2 dose arm was expanded to include a total of 24 patients, and the 100 units/m2 cohort was subsequently opened with a total of 16 patients enrolled. Baseline characteristics were well balanced across treatment groups (Table 1). Two patients younger than 60 years were enrolled in the 50 units/m2 and 75 units/m2 dose arms, ages 55 and 57 years respectively. These patients met eligibility criteria for high risk for induction mortality because one had t-AML and a PS of 2, and the other had AML transformed from MDS, a mutation in TP53 and a PS of 2. The median number of risk factors for induction mortality considered as eligibility criteria was 2 (range: 1–5) (Figure 2). The median age of all patients enrolled was 69 years (range: 55–84 years), and 66% were male. High risk features for the overall population included a PS of 2–3 in 15 (27%) patients, and adverse cytogenetics according to ELN in 30 (54%) patients. In addition, 46 (82%) patients had received prior treatment with a hypomethylating agent (HMA) for their antecedent hematologic malignancy, all but one of them had progressed following their HMA treatment. The median duration of follow-up for all enrolled patients was 27.8 months (range, 0.5 to 39.2 months).

Figure 1:

Trial consort. All patients who received treatment were considered evaluable for safety and efficacy assessment.

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics

| Characteristic | All (CPX-351) | 50 units/m2 | 75 units/m2 | 100 units/m2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| No. of patients | 56 | 16 | 24 | 16 | |

| Median age, years (range) | 69 (55–84) | 67 (57–81) | 68 (55–84) | 70 (63–80) | 0.41 |

| Female, no. (%) | 19 (34) | 7 (44) | 8 (33) | 4 (25) | 0.52 |

| Male, no (%) | 37 (66) | 9 (56) | 16 (67) | 12 (75) | |

| WBC, median × 109/L (range) | 2.5 (0.3–61) | 3.5 (1.3–61) | 2.5 (0.3–27) | 1.8 (0.3–56) | 0.15 |

| Hg, median g/L (range) | 8.8 (6.9–10.5) | 9.0 (7.4–9.8) | 9.0 (6.9–10.5) | 8.3 (7.0–10.1) | 0.09 |

| Platelets, median × 109/L (range) | 27 (2–129) | 18 (9–99) | 35 (2–129) | 21 (5–96) | 0.10 |

| Creatinine > 1.3 g/dL, no. (%) | 2 (4) | 1 (1) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 0.46 |

| ECOG performance status score, no. (%) | 0.005 | ||||

| 0–1 | 41 (73) | 9 (56) | 22 (92) | 10 (62) | |

| 2–3 | 15 (27) | 7 (44) | 2 (8) | 6 (38) | |

| s-AML/t-AML, no. (%) | 51 (91) | 16 (100) | 21 (88) | 14 (88) | 0.56 |

| AML MRC, no. (%) | 5 (9) | 0 | 3 (12) | 2 (12) | |

| Prior HMA exposure* | 46 (82) | 15 (94) | 18 (75) | 13 (81) | 0.38 |

| Cytogenetics, no. (%) | 0.45 | ||||

| Diploid | 6 (11) | 2 (13) | 3 (13) | 1 (7) | |

| Adverse^ | 30 (54) | 10 (62) | 12 (50) | 8 (50) | |

| Other | 14 (25) | 4 (25) | 6 (25) | 4 (25) | |

| IM or not done | 6 (10) | 0 | 3 (12) | 3 (18) | |

| Median no. of induction mortality factors (range)# | 2 (1–5) | 3 (1–5) | 2 (1–4) | 2 (1–4) | 0.04 |

| Mutations, no. (%) | |||||

| ASXL1 | 16 (29) | 5 (31) | 6 (25) | 5 (33) | 0.87 |

| TP53 | 14 (25) | 3 (19) | 6 (25) | 5 (33) | 0.69 |

| KRAS/NRAS | 13 (23) | 6 (38) | 4 (16) | 3 (19) | 0.32 |

| TET2 | 10 (18) | 5 (31) | 1 (4) | 4 (25) | 0.05 |

| IDH1/2 | 6 (11) | 1 (6) | 4 (16) | 1 (7) | 0.64 |

| RUNX1 | 6 (11) | 3 (19) | 2 (8) | 1 (1) | 0.55 |

| DNMT3A | 5 (9) | 2 (12) | 3 (12) | 0 (0) | 0.50 |

| EZH2 | 4 (7) | 2 (12) | 0 (0) | 2 (13) | 0.20 |

| JAK2 | 2 (4) | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 1 (7) | 0.32 |

Abbreviations: WBC, white blood cell; Hg, hemoglobin; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; s-AML/t AML, secondary or therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia; MDS RC, myelodysplastic syndrome-related changes; HMA, hypomethylating agent; IM, insufficient metaphases.

Adverse risk cytogenetics according to the European LeukemiaNet (ELN) classification.

All received HMA for prior MDS, CMML or MPN and all but one had no benefit or disease progression following therapy with a hypomethylating agent.

Factors used as eligibility criteria indicating a high risk of induction mortality.

Figure 2:

Distribution of risk factors for induction mortality used as eligibility criteria for patients enrolled on this trial.

Efficacy

There was a non-statistically significant trend for a higher response rate with higher doses of CPX-351 (Table 2). CR was achieved in 3 (19%) of 16 patients in the 50 units/m2 cohort, 6 (25%) of 24 in the 75 units/m2 cohort, and in 7 (44%) of 16 in the 100 units/m2 cohort. A similar trend was observed for overall remission rate (CR+CRi) (19%, 38%, and 44%, respectively; P = 0.35). Four patients received a second induction cycle (2 in the 75 units/m2 dose cohort and 2 in the 100 units/m2 cohort) and none achieved CR/CRi. Four (21%) of the 19 patients that achieved CR/CRi had undetectable MRD following induction, 3 of the 4 were treated at 100 units/m2. The median time to achieve CR/CRi was 37 days (range: 27–118 days). Among patients not previously treated with an HMA, 5 (50%) of 10 patients achieved CR/CRi, compared to 14 (30%) of the patients with prior HMA exposure. Among responders, the median number of all cycles received per patient was 2 (range: 1–5 cycles). The median number of consolidation cycles was 2 (range: 1–4 cycles).

Table 2:

Responses

| CPX-351 | All | 50 units/m2 | 75 units/m2 | 100 units/m2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| CR | 16 (29) | 3 (19) | 6 (25) | 7 (44) | |

| CRi | 3 (5) | 0 | 3 (13) | 0 | |

| CR+CRi | 19 (34) | 3 (19) | 9 (38) | 7 (44) | 0.35* |

| Treatment failure | 37 (66) | 13 (81) | 15 (62) | 9 (56) | |

| No response | 36 (64) | 13 (81) | 14 (58) | 9 (56) | |

| Death in aplasia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Death from indeterminate cause | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (4) | 0 | |

| MRD negative | 4 (21)^ | 0 | 1 (4) | 3 (19) | 0.16 |

Values are n (%). Abbreviations: CR, complete response; CRi, CR with incomplete hematologic recovery; MRD, minimal residual disease: assessed following induction.

Comparison of CR+CRi among 3 cohorts.

Four (21%) of the 19 patients that achieved CR/CRi had undetectable MRD following induction.

The median duration of response for all patients was 8.9 months (range: 1.1–37.9 months) (Supplemental figure 1). Patients who received 50 units/m2 had a trend for a shorter CRD (median 5.3 months), compared to 9.4 and 14.3 months for those who received 75 units/m2 and 100 units/m2, respectively (P = 0.2) (Supplemental figure 1). Among the patients who achieved CR/CRi, 11 (67%) of the 19 patients relapsed (3 in the 50 units/m2 arm, 4 in the 75 units/m2 arm and 4 in 100 units/m2 arm). The median remission duration for the 8 patients with ongoing remission was 15.7 months (range, 1.6 to 37.9 months).

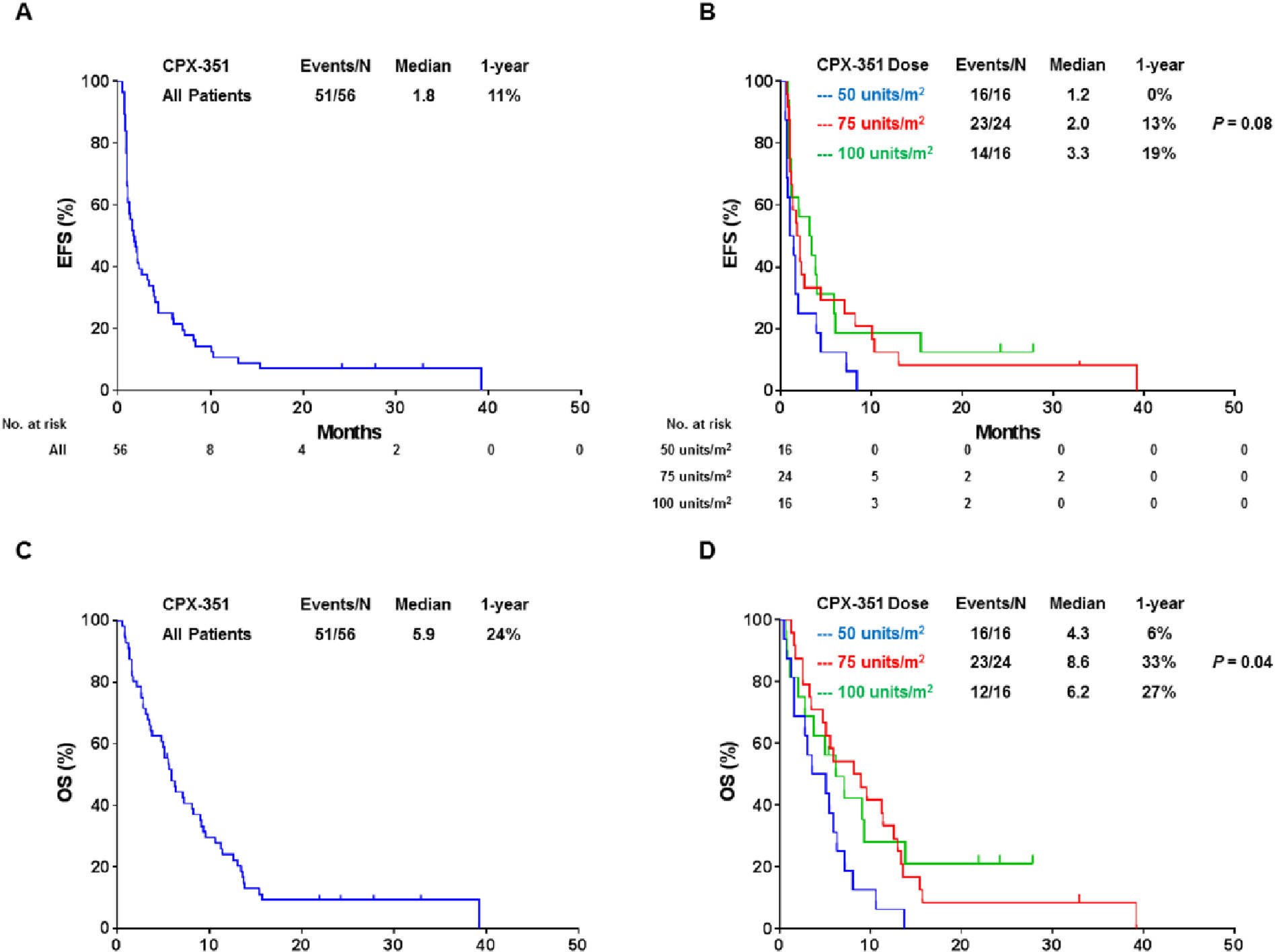

The median EFS for all patients was 1.8 months, with a 1-year EFS rate of 11 % (Figure 3A). The 50 units/m2 had a trend for a shorter EFS (median 1.2 months) while the other two cohorts had a median EFS of 2.0 and 3.3 months (for the 75 and 100 units/m2 cohorts, respectively) (Figure 3B). The median overall survival of all patients enrolled on the trial was 5.9 months with a 1-year OS rate of 24% (Figure 3C). OS was shorter for patients in the 50 units/m2 cohort (median of 4.3 months), and it was 8.6 and 6.2 months in the 75 and 100 units/m2 cohorts, respectively (P = 0.04) (Figure 3D).

Figure 3:

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS). (A) EFS for all patients on study. (B) EFS by treatment cohort. (C) OS for all patients on study. (D) OS by treatment cohort.

Five patients who achieved CR/CRi received HSCT (9% of enrolled patients). With the limitations of the small sample size, among patients who achieved CR/CRi, those that received HSCT had similar OS to those who did not (median OS of 13 months and 12.4 months, respectively). Similarly, censoring patients at the time of HSCT yielded a similar EFS (1.75 months; data not shown). At last follow-up, five patients were still alive (one in the 75 units/m2 arm, and 4 in the 100 units/m2 arm; one received HSCT).

Patients with a diploid karyotype had significantly better OS compared to those with a non-diploid karyotype with a median OS of 14.5 months vs 5.5 months, respectively (P = 0.04). Those with prior exposure to HMA had a trend for a shorter OS compared to those not previously treated with HMA (median OS of 5.6 vs 8.6, respectively). Patients with mutations in TP53 had an inferior OS with a median of 2.6 months compared to 6.3 months for those with the wildtype gene (P = 0.002).

Safety

The 60-day mortality rate was 20% (11/56 patients enrolled) (Table 3). The 50 units/m2 dose cohort had the highest 60-day mortality rate of 31% (5 deaths among 16 patients), compared to 12% (3 among 24 patients) for the 75 units/m2, and 19% (3 among 16 patients) for the 100 units/m2 (P = 0.37). No death was judged to be related to the study drug (Supplemental table 1).

Table 3:

Induction mortality

| CPX-351 | All | 50 units/m2 | 75 units/m2 | 100 units/m2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| 30-d mortality | 4 (7%) | 2 (12%) | 0 (0) | 2 (13%) | 0.20 |

| 60-d mortality | 11 (20%) | 5 (31%) | 3 (12%) | 3 (19%) | 0.37 |

Values are n (%)

Grade 3–4 treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) occurred in 70% (39/56) of patients enrolled. The most frequently (>5% of patients) reported non-hematologic grade 3–4 TEAEs were febrile neutropenia (34%, n=19), pneumonia (23%, n=13), and sepsis (16%, n=9) (Table 4). Serious adverse events (SAEs) occurred in 31 (55 %) patients (10 patients in the 50 units/m2 cohort, 8 patients in the 75 units/m2 cohort and 13 patients in the 100 units/m2 cohort). There were no DLTs.

Table 4:

Non-hematologic toxicities, grades 3–5.

| CPX-351 (units/m2) | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 5 | Grade 3–5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | 75 | 100 | 50 | 75 | 100 | 50 | 75 | 100 | All | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Febrile neutropenia | 1 (6) | 12 (50) | 6 (38) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 (34) |

| Pneumonia | 0 | 8 (33) | 5 (31) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (13) | 0 | 0 | 15 (27) |

| Sepsis | - | - | - | 2 (13) | 5 (21) | 2 (13) | 0 | 0 | 1 (6) | 10 (18) |

| Respiratory failure | - | - | - | 0 | 2 (8) | 0 | 0 | 1 (4) | 2 (13) | 6 (11) |

| Skin infection | 1 (6) | 1 (4) | 1 (6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (5) |

| ALT/AST elevation | 0 | 2 (8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (4) |

| Bilirubin increased | 0 | 1 (4) | 1 (6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (4) |

| Hypertension | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4) | 1 (6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (4) |

| Multi-organ failure | - | - | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4) | 1 (6) | 2 (4) |

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 1 (6) | 0 | 1 (6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (4) |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 0 | 1 (4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Hypotension | 0 | 0 | 1 (6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Pancreatitis | 0 | 1 (4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Pleural effusion | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Enterocolitis infectious | 0 | 0 | 1 (6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Joint effusion | 0 | 1 (4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Edema limbs | 1 (6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) |

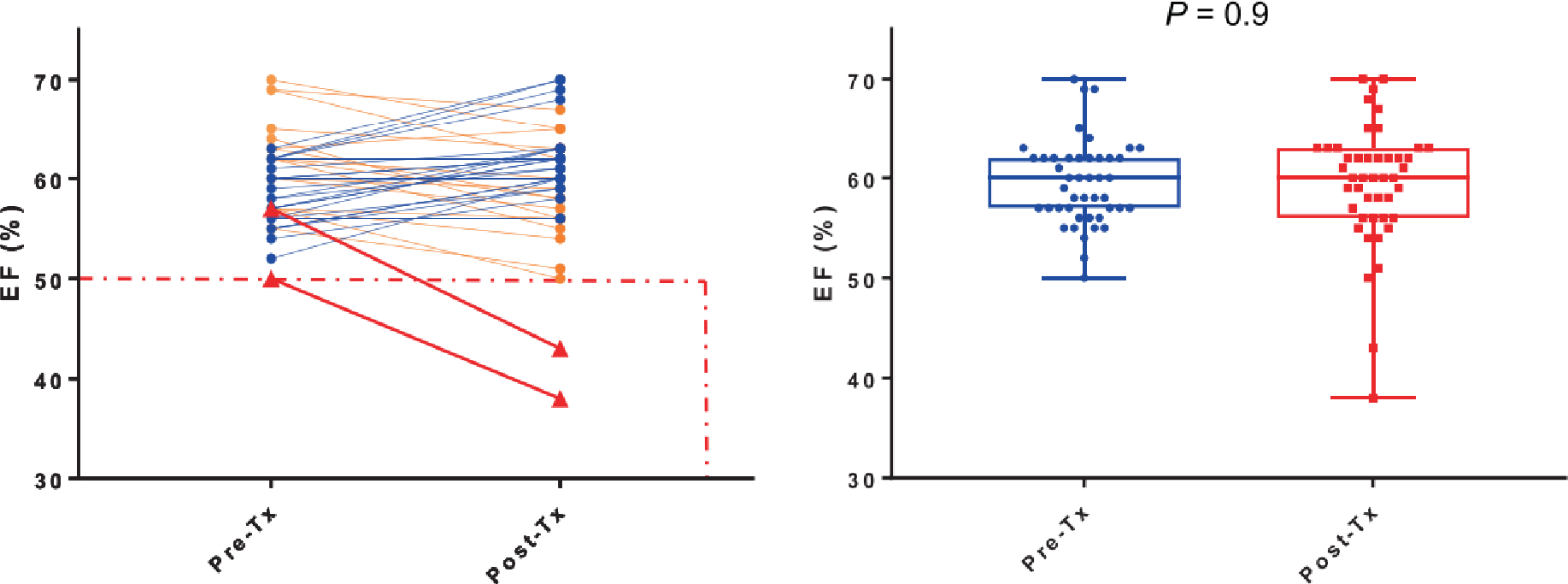

There was no statistically significant change in the EF pre- and post-therapy with CPX-351 (P = 0.9) (Figure 4). However, one patient enrolled on the 100 units/m2 had his EF transiently decrease to 38% from a baseline of 50%; 30 days later, it increased back to 52%.

Figure 4:

Change in ejection fraction pre and post-treatment with CPX-351. (A) Each line represents a patient with EF evaluation done pre and post-treatment. Blue lines represent those with unchanged or increased EF, orange lines represent those with decreased EF, red lines represent 2 patients with decrease >10% EF to ≤50%. (B) Comparing pre and post-treatment with CPX-351, change in EF was not statistically significant.

The median time to absolute neutrophil count (ANC) recovery (≥1 ×109 neutrophils/L) for all patients with CR/CRi was 36 days (mostly similar among dose arms with median times of 39, 35, and 34 days for the 50, 75, and 100 units/m2 cohorts, respectively). The median time to platelet count recovery (≥100 ×109 platelets/L) in patients with CR was 35 days (median times of 32, 35, and 37 days, respectively) (Supplemental figure 2).

Outcomes of patients older than 75 years

There were 14 patients older than 75 years of age enrolled on this study. The median number of risk factors for induction mortality used as eligibility criteria was 3 (range 2–4) in this cohort. Four patients were enrolled on the 50 units/m2 cohort, six on the 75 units/m2 cohort and four on the 100 units/m2 cohort. Ten of these fourteen patients had an ECOG PS score of 1 and four a PS of 2. The CR/CRi rate for this group of patients was 43% (6 of the 14 patients, the rest had no response to treatment). These responses were seen in 1 patient who received the 50 units/m2 dose, 2 who received the 75 units/m2 dose and 3 who received the 100 units/m2 dose. Among these patients, the 60-day mortality rate was 29% (4/14 patients, 0% 30-d mortality). None of these patients had a HSCT. The median EFS was 2.0 months and the median OS was 7.1 months.

Discussion

We conducted a phase II trial to evaluate the efficacy of escalating doses of CPX-351 in patients with AML considered at high risk of induction mortality with intensive chemotherapy. Our results suggest that these patients can tolerate therapy with CPX-351 at the same standard dose as approved for patients with secondary AML. The pivotal trial of CPX-351 for patients with secondary AML enrolled patients up to age 75 years, and excluded patients with a creatinine of 2 mg/dl or higher or with PS ≥3 (10). In addition, although prior therapy with HMA was acceptable on that trial, only 32–35% of patients had received such therapy and 34% were considered fit for and underwent HSCT. Our study aimed to include more of such patients. Overall, 14 (25%) patients were age ≥75 years, 2 (4%) had a PS of 3, 46 (82%) had received prior HMA, and only 5 (9%) were considered fit and underwent HSCT. With these considerations in mind, the CR/CRi rate in the CPX-351 arm of the pivotal study was 47.7% with a median OS of 9.5 months (10). Thus, patients with such high-risk features can receive therapy with CPX-351 at the same dose as those enrolled in the pivotal study.

Although dose had no noticeable impact on safety, there appeared to be an influence on efficacy measures. Our results suggest that CPX-351 in this setting had higher efficacy at the 75 or 100 units/m2 doses compared to the 50 units/m2 dose. The CR/CRi rate in the 50 units/m2 dose was 19%, compared to 38% with 75 units/m2 and 44% with 100 units/m2 doses, respectively. CPX-351 at 50 units/m2 had the highest 60-day mortality rate in addition to the lowest efficacy and shortest survival. This was likely due to lower efficacy at this dose, and inadequate disease control in most patients. The rate of MRD negative response was relatively low in this study, highlighting the difficulty of balancing efficacy and depth of response with safety in this patient population where the majority had progression of their disease following HMA therapy. The median OS of patients who received CPX-351 at 50 units/m2 was 4.3 months. The median survival for the 75 and 100 units/m2 cohorts was 8.6 months and 6.2 months, respectively. This may suggest a possible benefit for these patients, particularly considering the other high-risk features as defined in the eligibility criteria. Such possible benefit should be confirmed in a randomized setting.

To provide context, in a retrospective analysis of patients with AML or MDS who had failed HMA, patients with AML treated with 7+3 had an overall response rate (ORR) of 39% and a median OS of 8.0 months, compared to 64% and 6.9 months with intermediate-dose cytarabine, and 34% with a 4.4 months median OS for those treated with purine analogues (P = 0.06) (16). In another series, patients who failed prior decitabine for MDS and were treated with various subsequent regimens including standard chemotherapy, stem cell transplant or supportive care had a median survival of 4.3 months (17). Recognizing the limitation of the retrospective nature of these reports and possible differences in risk features (e.g., 42% with favorable risk cytogenetics in the first series compared to 11% in our study), our results, particularly with the 75 or 100 units/m2 doses seem to compare favorably. In addition, outcomes with 75 or 100 units/m2 of CPX-351 seem to be better than those reported with the combinations of LDAC/imatinib (4.6 months), LDAC/lintuzumab (4.7 months), or LDAC/volasertib (phase II 8.0 months, phase III 4.8 months) (18–22), but similar to those reported with low-dose cytarabine (LDAC) plus glasdegib (median OS of 8.8 months, ORR 26.9%) (18). This trial shares some similarities with a phase II randomized clinical trial performed at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center investigating CPX-351 for a similar patient population albeit some differences (23). The Fred Hutchinson trial was designed to investigate attenuated doses of CPX-351 (32 or 64 units/m2 vs 101 units/m2) in less fit adults with myeloid neoplasms (though the majority of patients had AML, patients with MDS or CMML were included). Patients with a treatment-related mortality (TRM) score of >13.1 were enrolled (24). This score, composed of weighted information from 8 covariates including age, performance status, WBC, peripheral blood blast percentage, type of AML, platelet count, albumin, and creatinine, corresponds to the estimated probability of death within 28 days of receiving intensive chemotherapy for newly diagnosed AML (24). Compared to our study, the Fred Hutchinson trial had a higher percentage of patients with poor performance status (ECOG PS > 2 of 15% vs 90%) and probably more patients with decreased renal function (unlike our trial, no upper creatinine limit was included in the eligibility criteria). In contrast, fewer patients with s-AML were enrolled in that study (60% vs 91%), and the doses of CPX-351 used in their study were lower than the ones investigated in ours. The 28-day mortality rate was 31%, with a CR/CRi rate of 23% and a median OS of 3 months for their entire cohort. Acknowledging the difficulties in comparing across trials with differences in baseline patient variables treatment doses and study design, this difference in outcomes perhaps highlights the larger impact of factors such as performance status and organ dysfunction on safety and efficacy outcomes with chemotherapy compared to other risk factors for induction mortality similar to what has been described (24). This also highlights the need to include more of these patients in clinical trials and the need develop more novel treatment strategies.

Combination strategies containing the oral Bcl-2 inhibitor venetoclax with low-intensity treatment are emerging as standard of care in the older AML population. Use of venetoclax in combination with either HMA or LDAC has yielded improved outcomes for older patients with AML. Venetoclax combined with either azacitidine or decitabine led to a CR/CRi rate of 66% in older patients with AML and a median overall survival of 17.5 months (only 9–25% had an antecedent hematological disorder) (25), although results of ongoing randomized trials are currently unavailable. In addition, venetoclax/LDAC in older AML patients, ineligible for intensive chemotherapy led to a CR/CRi rate of 54% and a median OS of 10.1 months (49% had secondary AML, 29% had received prior HMA), however those with prior HMA exposure (which represent more than 80% of our study population) had significantly lower OS with a median of 4.1 months which is similar to what we describe in this analysis with CPX-351 (26). Ultimately, CPX-351 would have to be compared to options such as LDAC + glasdegib or venetoclax + LDAC or HMA as these are currently approved treatment options for patients considered unfit for standard chemotherapy.

In conclusion, we show in this study that CPX-351 can be delivered safely in patients with AML with risk features considered at high-risk of induction mortality with intensive chemotherapy. The 50 units/m2 dose yielded sub-optimal results in this setting. Based on our results, CPX-351 at 75 units/m2 or 100 unit/m2 is a relatively safe and effective option for patients at high risk of induction mortality. Beyond comparing CPX-351 with standard available options, these results can be built upon in the future, through incorporation of CPX-351 in strategies aimed at improving outcomes for older AML patients, such as combinations with venetoclax or targeted therapies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

GCI received funding through the K12 Paul Calabresi Clinical Scholarship Award (NIH/NCI K12 CA088084).

Funding source:

The study was supported in part by Celator/Jazz, and by the Cancer Center Support Grant (NCI Grant P30 CA016672).

Footnotes

Competing Interests

GCI received research funding from Celgene and served on an advisory board for Novartis. HMK received research funding from Ariad; Astex; Bristol-Myers Squibb; Cyclacel; Daiichi-Sankyo; Pfizer; Immunogen; Jazz; Novartis and honoraria from Pfizer; Immunogen; Actinium and Takeda. YA received research funding from Jazz and honoraria from Abbott. GB received research funding from AbbVie; Incyte; Janssen; Cyclacel; BioLine Rx; NKarta: and consulting honoraria from BioLine Rx; NKarta; PTC Therapeutics; Oncoceutics, Inc. ND received research funding from Sunesis Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Karyopharm; Immunogen; Pfizer; Incyte; Bristol-Myers Squibb; Daiichi-Sankyo; Kiromic and consulting honoraria from Sunesis Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Karyopharm; Pfizer; Incyte; Bristol-Myers Squibb; Novartis; Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc. CDD received research funding from Agios; Novartis; Celgene; Daiichi-Sankyo; Calithera Biosciences and consulting honoraria from AbbVie; Agios; Novartis; Celgene; Daiichi-Sankyo; Jazz; Notable Laboratories and is a Scientific Advisory Board member of Notable Laboratories. PB received research funding from Incyte; Celgene; CTI BioPharma; Blueprint Medicines; Constellation Pharmaceuticals; Kartos Therapeutics; Astellas; Pfizer; NS Pharma; Promedior and consulting honoraria from Incyte; Celgene; CTI BioPharma; Blueprint Medicines; Kartos Therapeutics. NJ received research funding and consulting honoraria from AbbVie; Pharmacyclics; Genentech; Bristol-Myers Squibb; Pfizer; ADC Therapeutics; AstraZeneca; Servier; Cellectis; Verastem; Precision Biosciences; Adaptive. NP received research funding from Stemline; Novartis; Abbvie; Samus; Cellectis; Plexxikon; Daiichi-Sankyo; Affymetrix; and received consulting honoraria from Celgene; Stemline; Incyte; Novartis; MustangBio; Roche Di, LFB. KT received research funding from Onconova; MEI, served on an advisory board for Symbio Pharmaceuticals; GSK; Celgene and received honoraria from Dava Oncology; Kyowa Hakko Kirin. MA received research funding from Daiichi Sankyo, Inc.; Jazz; and consultancy honoraria from Jazz; Celgene; Amgen; AstaZeneca; Dimensions Capital; and equity ownership from Reata; Aptose; Europics; Senti Bio; Oncoceutics; Oncolyze. FR received research funding from Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Seattle Genetics, Sunesis Pharmaceuticals; Pfizer; and honoraria for consulting or advisory role for Jazz; Amgen; Seattle Genetics; Sunesis Pharmaceuticals. JEC received research funding (to the institution while at the MD Anderson) and consulting honoraria from Celator/Jazz, Novartis, Daiichi, Astellas, Daiichi, Merus, Immunogen, Biopath Holdings.

References

- 1.Appelbaum FR, Gundacker H, Head DR, Slovak ML, Willman CL, Godwin JE, et al. Age and acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2006;107(9):3481–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Østgård LSG, Medeiros BC, Sengeløv H, Nørgaard M, Andersen MK, Dufva IH, et al. Epidemiology and Clinical Significance of Secondary and Therapy-Related Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A National Population-Based Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2015;33(31):3641–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leith CP, Kopecky KJ, Godwin J, McConnell T, Slovak ML, Chen IM, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia in the elderly: assessment of multidrug resistance (MDR1) and cytogenetics distinguishes biologic subgroups with remarkably distinct responses to standard chemotherapy. A Southwest Oncology Group study. Blood. 1997;89(9):3323–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grimwade D, Hills RK, Moorman AV, Walker H, Chatters S, Goldstone AH, et al. Refinement of cytogenetic classification in acute myeloid leukemia: determination of prognostic significance of rare recurring chromosomal abnormalities among 5876 younger adult patients treated in the United Kingdom Medical Research Council trials. Blood. 2010;116(3):354–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kantarjian H, O’Brien S, Cortes J, Giles F, Faderl S, Jabbour E, et al. Results of intensive chemotherapy in 998 patients age 65 years or older with acute myeloid leukemia or high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome: predictive prognostic models for outcome. Cancer. 2006;106(5):1090–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Othus M, Kantarjian H, Petersdorf S, Ravandi F, Godwin J, Cortes J, et al. Declining rates of treatment-related mortality in patients with newly diagnosed AML given ‘intense’ induction regimens: a report from SWOG and MD Anderson. Leukemia. 2014;28(2):289–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim WS, Tardi PG, Dos Santos N, Xie X, Fan M, Liboiron BD, et al. Leukemia-selective uptake and cytotoxicity of CPX-351, a synergistic fixed-ratio cytarabine:daunorubicin formulation, in bone marrow xenografts. Leukemia research. 2010;34(9):1214–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim HP, Gerhard B, Harasym TO, Mayer LD, Hogge DE. Liposomal encapsulation of a synergistic molar ratio of cytarabine and daunorubicin enhances selective toxicity for acute myeloid leukemia progenitors as compared to analogous normal hematopoietic cells. Experimental hematology. 2011;39(7):741–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tardi P, Johnstone S, Harasym N, Xie S, Harasym T, Zisman N, et al. In vivo maintenance of synergistic cytarabine:daunorubicin ratios greatly enhances therapeutic efficacy. Leukemia research. 2009;33(1):129–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lancet JE, Uy GL, Cortes JE, Newell LF, Lin TL, Ritchie EK, et al. CPX-351 (cytarabine and daunorubicin) Liposome for Injection Versus Conventional Cytarabine Plus Daunorubicin in Older Patients With Newly Diagnosed Secondary Acute Myeloid Leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(26):2684–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Döhner H, Estey E, Grimwade D, Amadori S, Appelbaum FR, Büchner T, et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood. 2017;129(4):424–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feldman EJ, Lancet JE, Kolitz JE, Ritchie EK, Roboz GJ, List AF, et al. First-in-man study of CPX-351: a liposomal carrier containing cytarabine and daunorubicin in a fixed 5:1 molar ratio for the treatment of relapsed and refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(8):979–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu J, Jorgensen JL, Wang SA. How Do We Use Multicolor Flow Cytometry to Detect Minimal Residual Disease in Acute Myeloid Leukemia? Clin Lab Med. 2017;37(4):787–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luthra R, Patel KP, Reddy NG, Haghshenas V, Routbort MJ, Harmon MA, et al. Next-generation sequencing-based multigene mutational screening for acute myeloid leukemia using MiSeq: applicability for diagnostics and disease monitoring. Haematologica. 2014;99(3):465–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thall PF, Simon RM, Estey EH. Bayesian sequential monitoring designs for single-arm clinical trials with multiple outcomes. Stat Med. 1995;14(4):357–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ball B, Komrokji RS, Ades L, Sekeres MA, DeZern AE, Pleyer L, et al. Evaluation of induction chemotherapies after hypomethylating agent failure in myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Adv. 2018;2(16):2063–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jabbour E, Garcia-Manero G, Batty N, Shan J, O’Brien S, Cortes J, et al. Outcome of patients with myelodysplastic syndrome after failure of decitabine therapy. Cancer. 2010;116(16):3830–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cortes JE, Heidel FH, Hellmann A, Fiedler W, Smith BD, Robak T, et al. Randomized comparison of low dose cytarabine with or without glasdegib in patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia or high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome. Leukemia. 2019;33(2):379–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Döhner H, Lübbert M, Fiedler W, Fouillard L, Haaland A, Brandwein JM, et al. Randomized, phase 2 trial of low-dose cytarabine with or without volasertib in AML patients not suitable for induction therapy. Blood. 2014;124(9):1426–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sekeres MA, Lancet JE, Wood BL, Grove LE, Sandalic L, Sievers EL, et al. Randomized, phase IIb study of low-dose cytarabine and lintuzumab versus low-dose cytarabine and placebo in older adults with untreated acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2013;98(1):119–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeAngelo DJ, Sekeres MA, Ottmann OG, Sanz MA, Naoe T, Taube T, et al. Phase III randomized trial of volasertib combined with low-dose cytarabine (LDAC) versus placebo plus LDAC in patients aged ≥65 years with previously untreated, acute myeloid leukemia (AML) ineligible for intensive remission induction therapy. Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma and Leukemia. 2015;15:S194. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heidel F, Cortes J, Rucker FG, Aulitzky W, Letvak L, Kindler T, et al. Results of a multicenter phase II trial for older patients with c-Kit-positive acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (HR-MDS) using low-dose Ara-C and Imatinib. Cancer. 2007;109(5):907–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walter RB, Othus M, Orlowski KF, McDaniel EN, Scott BL, Becker PS, et al. Unsatisfactory efficacy in randomized study of reduced-dose CPX-351 for medically less fit adults with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia or other high-grade myeloid neoplasm. Haematologica. 2018;103(3):e106–e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walter RB, Othus M, Borthakur G, Ravandi F, Cortes JE, Pierce SA, et al. Prediction of Early Death After Induction Therapy for Newly Diagnosed Acute Myeloid Leukemia With Pretreatment Risk Scores: A Novel Paradigm for Treatment Assignment. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(33):4417–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DiNardo CD, Pratz KW, Letai A, Jonas BA, Wei AH, Thirman M, et al. Safety and preliminary efficacy of venetoclax with decitabine or azacitidine in elderly patients with previously untreated acute myeloid leukaemia: a non-randomised, open-label, phase 1b study. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(2):216–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wei AH, Strickland SA Jr., Hou JZ, Fiedler W, Lin TL, Walter RB, et al. Venetoclax Combined With Low-Dose Cytarabine for Previously Untreated Patients With Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Results From a Phase Ib/II Study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(15):1277–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.