Abstract

Social factors like family background, education level, financial status, and stress can impact public health outcomes, such as suicidal ideation. However, the analysis of social factors for suicide prevention has been limited by the lack of up-to-date suicide reporting data, variations in reporting practices, and small sample sizes. In this study, we analyzed 172,629 suicide incidents from 2014 to 2020 utilizing the National Violent Death Reporting System Restricted Access Database (NVDRS-RAD). Logistic regression models were developed to examine the relationships between demographics and suicide-related circumstances. Trends over time were assessed, and Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) was used to identify common suicide-related social factors. Mental health, interpersonal relationships, mental health treatment and disclosure, and school/work-related stressors were identified as the main themes of suicide-related social factors. This study also identified systemic disparities across various population groups, particularly concerning Black individuals, young people aged under 24, healthcare practitioners, and those with limited education backgrounds, which shed light on potential directions for demographic-specific suicidal interventions.

Index Terms—: Social Determinants of Health, Social Factors, Suicide

I. INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization estimates that over 700,000 individuals die each year by suicide [1]. Historically, the African-American community in the United States (U.S.) has had lower suicide rates than their Caucasian counterparts [2]. However, recent years have witnessed a significant increase in the suicide rate among Black youth, with the suicide rate among Black children aged 5–11 experiencing a two-fold increase from 1993 to 2012 [3]. Moreover, suicide has become the second leading cause of death among individuals aged 10–24 in the U.S., making it a critical public health concern [4].

Besides suicide disparities in racial and age groups, studies also reveal that people with certain occupations are more likely to commit suicide. Physicians are shown to be a high-risk population for suicide as they demonstrate a higher likelihood of suicide due to a variety of factors, such as the high-stress nature of their profession [5] and specific personality traits of this population, with 28.8% of resident physicians reporting depression symptoms through clinical interviews or self-reporting instruments [6]. Previous studies suggest that besides the psychosocial work environment issues such as conflicts with colleagues and lack of social support, physicians often have to face breaking bad news, illnesses, anxiety, suffering, and death. Additionally, perfectionism, great attention to detail, exaggerated sense of responsibility and duty are highly appreciated qualities for physicians but are also contributors to stress and depression for this population [7], [8], [9], [10].

Moreover, previous work have explored the relationships between education level and suicide risk, and suggested the associations between suicide risk and various Social Determinants of Health (SDoH) factors, such as relationship problems, substance abuse problems, mental health problems, and job problems, etc. [11], [12]. However, several limitations remain as a result of outdated data, small sample sizes, and not being representative of the whole U.S. population [13]. Consequently, comprehending the social factors that potentially lead to suicide and identifying the variances across population groups is key to shaping effective prevention initiatives and offering appropriate assistance to individuals at risk.

To bridge this gap, our study analyzed the prevalence of 58 suicide-related circumstances and 19 suicide-related crises in the U.S. from 2014 to 2020. The primary objective of this study was to identify the influences of various social factors on suicidal ideation among different population groups, including groups with various races, age ranges, education levels, and job occupations. This study also analyzed the recent trends of the identified suicide-related social factors in order to capture the evolving dynamics of suicidal ideation. A detailed understanding of these suicide-related social factors and the suicide triggers involved will allow public health professionals, educators, and policymakers to design more targeted interventions and consequently significantly reduce suicide rates worldwide.

II. MATERIALS AND METHODS

A. National Violent Death Reporting System

This study analyzed a total of 172,629 suicide incidents from 2014 to 2020 (Table I) utilizing the National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS). The NVDRS database is the sole incident-based state reporting system in the U.S., and it records the demographic information of the victims, de-identified information on the precipitating circumstances and crises leading to violent deaths (e.g., suicide, homicide), etc. [14]. The data from NVDRS are collected from primary source documents, such as death certificates, medical examiner reports, and law enforcement reports, as well as secondary sources. By 2019, NVDRS has become a national database encompassing all 50 U.S. states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico.

TABLE I.

NVDRS statistics.

| Characteristic | Count | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 172,629 | |

| Age | ||

| Youth (10–24) | 24,119 | (14.0) |

| Non-Youth (≥25) | 148,500 | (86.0) |

| Race | ||

| Black | 10,229 | (5.9) |

| White | 152,069 | (88.1) |

| Other | 10,331 | (6.0) |

| Education (non-Youth) | ||

| College Degree | 43,789 | (25.4) |

| No College Degree | 103,713 | (60.1) |

| Job Occupation | ||

| Health Services | 12,771 | (7.4) |

| Other | 159,858 | (92.6) |

| Year | ||

| 2014 | 14,587 | (7.5) |

| 2015 | 20,227 | (10.4) |

| 2016 | 25,469 | (13.1) |

| 2017 | 29,332 | (15.0) |

| 2018 | 34,490 | (17.8) |

| 2019 | 32,881 | (16.8) |

| 2020 | 38,162 | (19.6) |

| Black youth | 2,664 | (1.5) |

To ensure data quality and focus the analysis on pertinent incidents, we excluded 22,519 incidents lacking comprehensive demographic or social information (Appendix Fig A.1). This includes suicide incidents where race (413), age (34), occupation (18,757), or education level (5,888) was unknown. Additionally, incidents involving both suicide and homicide were excluded from this study to maintain a clear distinction between the two types of violent deaths. This study has been approved by the NVDRS Restricted Access Database (RAD) Proposal.

The detailed investigative information gathered in NVDRS can provide an overall picture of the circumstances contributing to the violent deaths. Specifically, each incident in NVDRS is accompanied by two death investigation narratives written respectively by a coroner or medical examiner (CME) and law enforcement (LE) reporter describing the circumstances (e.g., social contexts, interpersonal relationships, life events, and mental illness, etc.) relevant to the incident. Such suicide-related circumstances are judged as the potential causes of suicide deaths [15]. In addition to the suicide-related circumstance variables, the crisis variables added to NVDRS after 2013 are also important as they identify suicide incients that appear to involve an element of impulsivity. Formally, a “CRISIS” is defined as an acute event (within two weeks before the suicide) that is indicated in at least one of the CME or LE reports to have contributed to the suicide. Table II shows the hierarchy of the suicide-related circumstances and crises [16] adopted in this work.

TABLE II.

Main circumstances, crises, and their categories.

| Categories | Circumstances | Crises |

|---|---|---|

| Violence and conflict | Victim used weapon, precipitated by other crime, fight between two people, argument, walk by assault, terrorist attack, stalking, prostitution, gang related, other crime inprogress, abused as child, intimate partner problem, intimate partner violence, interpersonal violence, traumatic brain injury history | Intimate partner problem, stalking, prostitution |

| Interpersonal relationship | Caregiver burgen, family stressor, family relationship problem, other relationship problem, jealousy | Family relationship problem, other relationship problem, jealousy |

| Psychosocial factors | Mental health problem, mental illness treatment history, current mental illness treatment, depressed mood, death abuse, recent criminal legal problem, recent friend/family suicide, death of friend/family, traumatic anniversary, disaster exposure, other legal problem, household substance abuse, household known to authorities, prior CPS report, physical health problem, school problem | Mental health problem, disaster exposure, recent criminal legal problem, civil legal problem, physical health problem, school problem, recent friend/family suicide |

| Substance use and treatment adherence | Other addiction, substance abuse, alcohol problem, treatment non-adherence, drug involvement | Alcohol problem, substance abuse, other addiction |

| Economic distress | Financial problem, job problem, eviction or loss of home, living transition | Job problem, financial problem, eviction or loss of home |

| Suicide disclosure | Suicide attempt history, suicide thought history, history self harm, suicide note, suicide intent disclosure (to intimate partner, healthcare worker, friend, neighbor, family, social media, other) | – |

B. Logistic Regression Models

In this study, we employed logistic regression models to examine the relationship between the prevalence of suicide-related circumstances and demographic/social variables, such as race, age, education level, occupation. One distinct logistic regression model was developed for each suicide-related circumstance.

In our setting, the predictor variable represented the specific comparison group (i.e. Black, youth, adults without a college degree, or those working in healthcare) and was coded as 1. This was then contrasted with the reference group (i.e. White, adults, adults with college degrees, or those not working in healthcare), coded as 0. Using the corresponding logistic regression model, we calculated the Odds Ratio (OR) for each comparison group from the coefficient estimate affiliated with the predictor variable.

The OR quantifies the likelihood of the specific circumstance occurring in a comparison group versus the reference group. The formula for computing the OR is as follows:

| (1) |

ORs greater than 1 indicate that the comparison group had higher circumstance rates than the reference group. To assess the precision of the OR estimates, we calculated a 95% confidence interval (CI) for each OR. The lower and upper bounds of these intervals were derived from the standard error of the coefficient estimate and the Z-score, corresponding to a 95% confidence level (Z = 1.96).

| (2) |

| (3) |

where “SE” refers to the standard error. We used the p-value to validate the statistical significance of the correlation between each circumstance and the comparison group. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Circumstances with OR greater than 1 and statistically significant p-values were selected from each comparison group for further analysis and discussion.

C. Circumstance and Crisis Trend Analysis

To assess the OR trends of relevant circumstances over time, we calculated the OR yearly from 2014 to 2020. From these ratios, we developed an OR graph for every category; quadratic regression modeling was used for fitting and visualization. The purpose was to gain a more thorough understanding of how the ORs of these circumstances have evolved over the specified time period.

Given that the number of examples for each circumstance may be too small to facilitate a robust statistical conclusion, we grouped them into six major categories for circumstances, and five major categories for crises (Table II) adopting the hierarchy defined in [16]. Within each category, if at least one circumstance in that category was present in an incident, the category was considered as present for that incident.

In addition, we also calculated the 3-year rolling ORs. Specifically, we aggregated overlapping three-year intervals, namely (2014–2016), (2015–2017), (2016–2018), (2017–2019), and (2018–2020) to assess the trends in the OR of the major categories over time. By employing this rolling analysis, we hoped to mitigate the potential impact of short-term fluctuations and random variations that might occur within individual years.

D. Latent Dirichlet Allocation

To uncover the common themes among the circumstances associated with suicide, we employed Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA), a probabilistic topic modeling technique on the 58 circumstance variables [17]. LDA uncovers latent topics present in a collection of documents. In our study, documents corresponded to individual suicide incidents, and topics were thematic clusters of the circumstances leading to suicide. The model input consisted of a matrix of binary values, where each row represented an individual incident, and each column represented one of the 58 circumstance variables. The LDA model was employed to cluster the 58 circumstances into 10 topics, which were subsequently reviewed and categorized through manual analysis.

III. RESULTS

A. Leading Causes of Suicide in Black Population

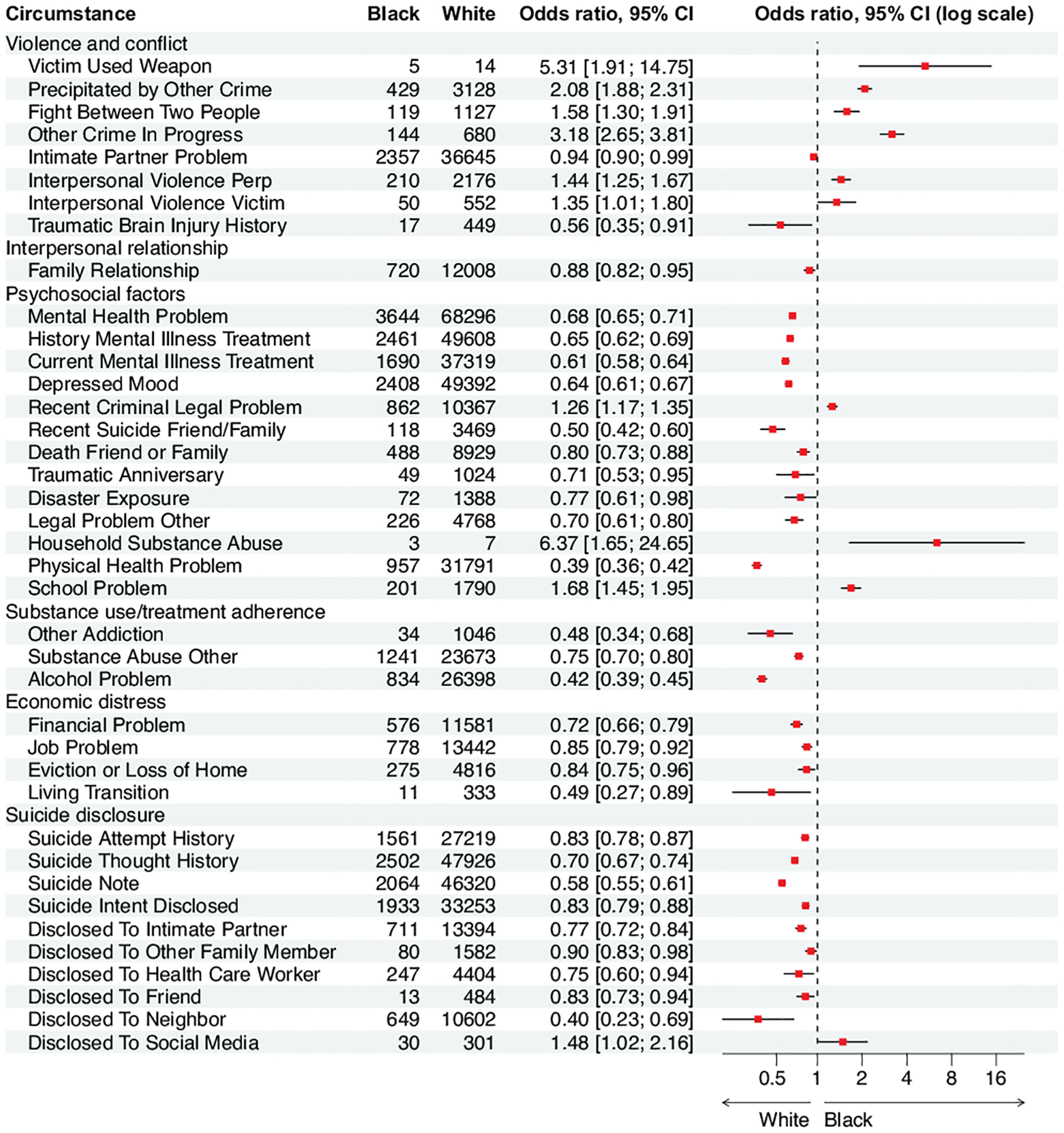

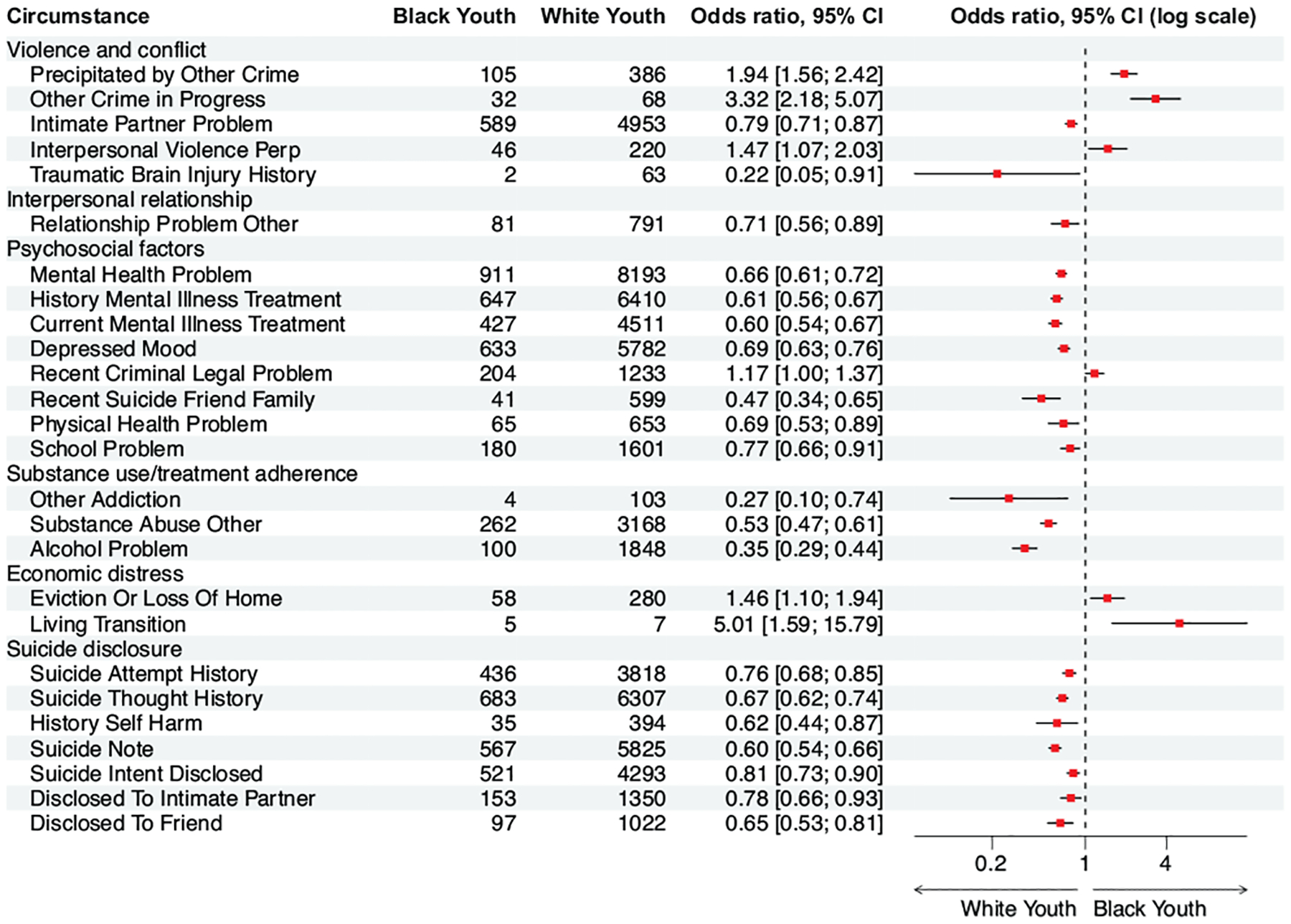

In terms of suicide-related circumstances, Black individuals who committed suicide were significantly more likely to have encountered certain circumstances than their White counterparts (Fig 1). When it comes to Violence and conflict, the top 3 circumstances with greater odds for Black individuals were: the use of a weapon (OR = 5.3, 95% CI = 1.9–14.7), in-progress crimes (OR = 3.1, 95% CI = 2.7–3.8), or precipitated by other crimes (OR = 2.1, 95% CI = 1.9–2.3). Regarding Psychosocial factors, such as adverse life experiences and stress, Black individuals were significantly more likely to have suffered from household substance abuse (OR = 6.4, 95% CI = 1.6–24.6), school problems (OR = 1.7, 95% CI = 1.5–1.9), and recent criminal legal problems (OR = 1.3, 95% CI = 1.2–1.4). Black individuals were also slightly more likely to have disclosed suicidal intentions to social media (OR = 1.5, 95% CI = 1.0–2.2).

Fig. 1.

Odds ratios for circumstances among Blacks, as compared with Whites. Estimates are in the center of the box and lines represent 95% confidence intervals. Log 2 is used to scale the x-axis. Insignificant ORs (p ≥ 0.05) were excluded.

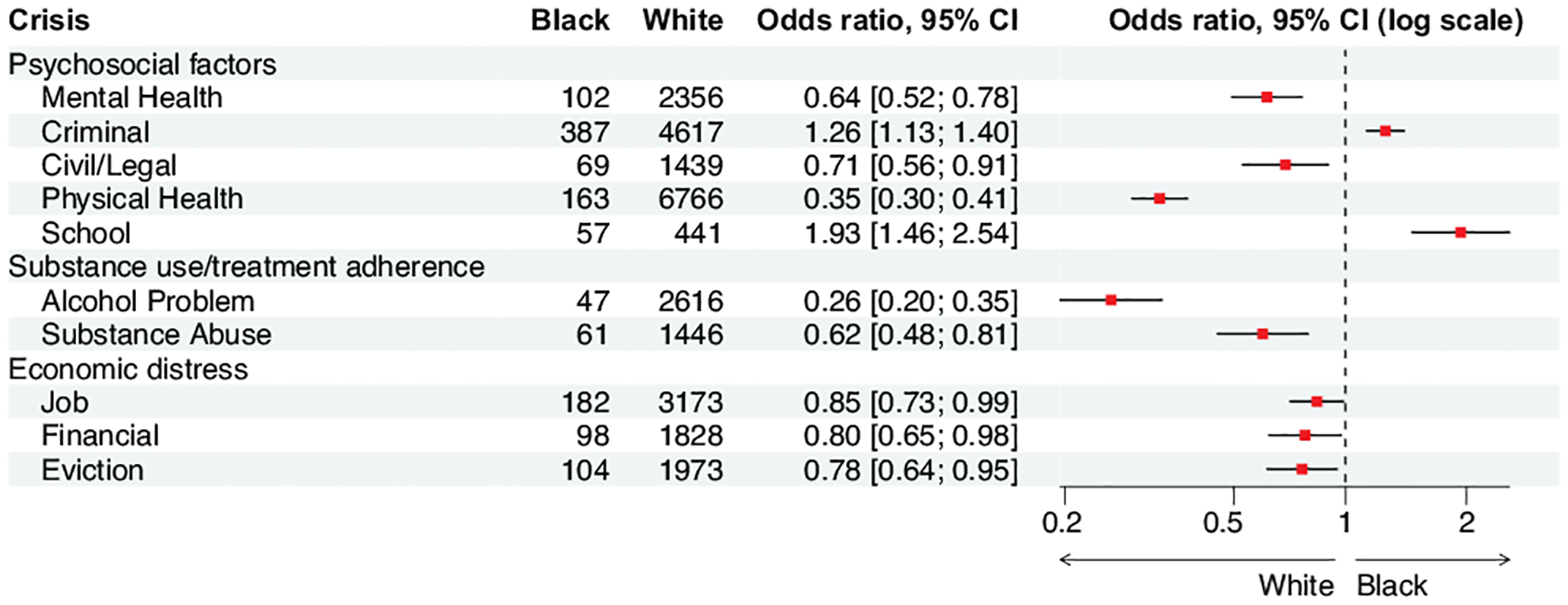

In terms of crises, criminal crises (OR = 1.3, 95% CI = 1.1–1.4), and school-related crises (OR = 1.9, 95% CI = 1.5–2.5) were found to be more prevalent for Black individuals, compared to those in the White population (Fig 2).

Fig. 2.

Odds ratios for crises among Blacks, as compared with Whites.

B. Leading Causes of Suicide in Youth Population

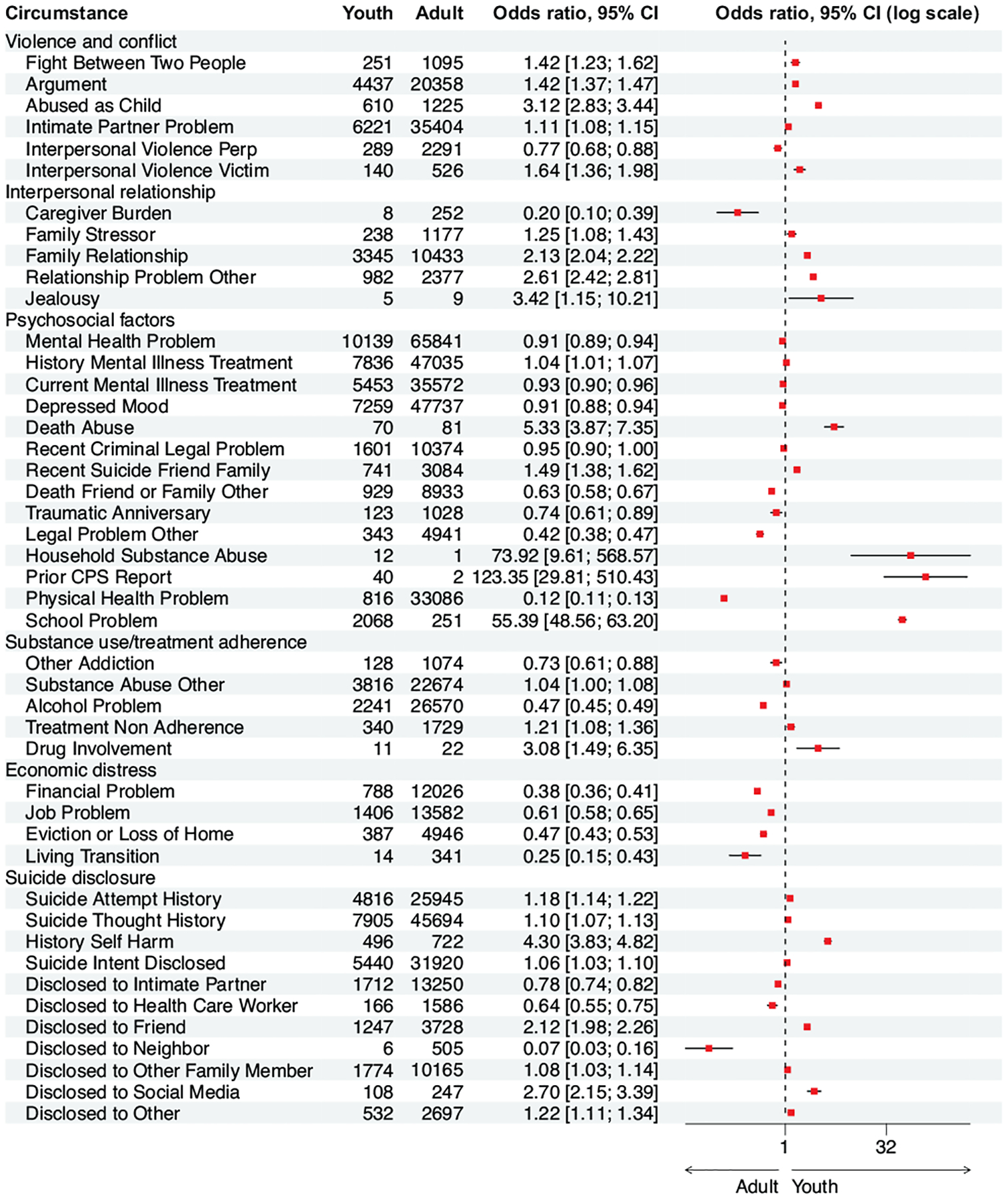

Regarding the youth population, the top three circumstances linked with Violence and conflict were child abuse (OR=3.1, 95% CI=2.8–3.4), interpersonal violence victim (OR=1.6, 95% CI=1.4–2.0), and argument (OR=1.4, 95% CI=1.4–2.5) (Fig 3). Within the category of Interpersonal relationships, jealousy (OR=3.4, 95% CI=1.1–10.2), family relationship problems (OR=2.1, 95% CI=2.0–2.2), and other relationship distress (OR=2.6, 95% CI=2.4–2.8) were more prevalent in the youth population than those in the adult population. When it comes to Psychosocial factors, the top three circumstances found among youth individuals were households for alleged child abuse (OR=123.4, 95% CI=29.8–510.4), household substance abuse (OR=73.9, 95% CI=9.6–568.6), and school-related problems (OR=55.4, 95% CI=48.6–63.2). For Substance use, youth individuals demonstrated higher rates of drug involvement (OR=3.1, 95% CI=1.5–6.4) and non-adherence to treatment for a mental health or substance abuse problem (OR=1.2, 95% CI=1.1–1.4). Furthermore, youth individuals were more likely to have revealed their suicidal intent to a friend (OR=2.1, 95% CI=2.0–2.3) or social media (OR=2.7, 95% CI=2.2–3.4). They were also more likely to have had a history of self-harm (OR=4.3, 95% CI=3.8–4.8).

Fig. 3.

Odds ratios for circumstances among youth (10–24 years old), as compared with adults.

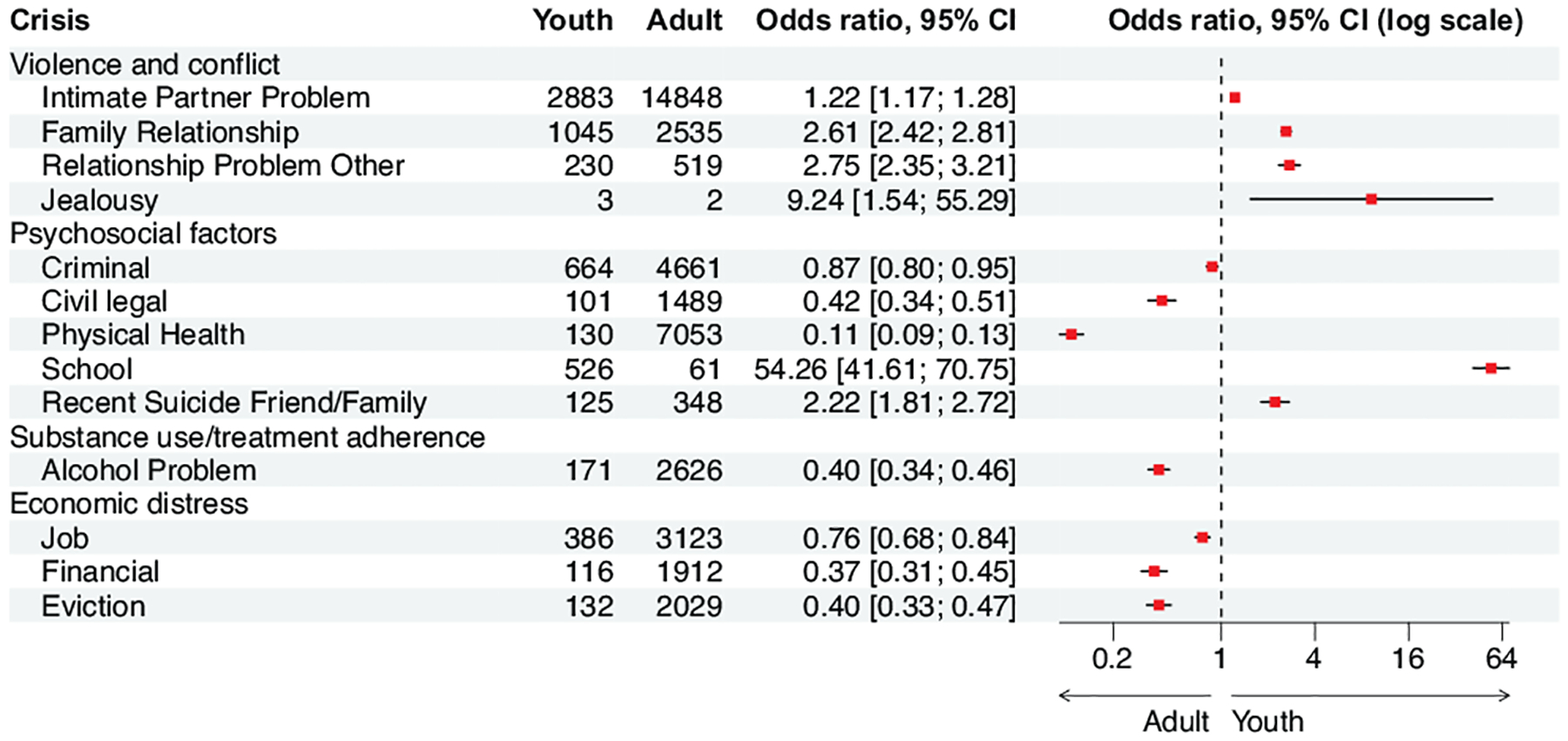

When analyzing crises of Violence and conflict, intimate partner crisis (OR=1.2, 95% CI=1.2–1.3) was found to be more common among youth decedents than adults. For Interpersonal relationships, young suicide decedents showed a higher prevalence of crises related to jealousy (OR=9.2, 95% CI=1.5–55.3), family relationship problem (OR=2.6, 95% CI=2.4–2.8), and other relationship problem (OR=2.7, 95% CI=2.3–3.2). Additionally, among Psychosocial factors, school-related crises (OR=54.3, 95% CI=41.6–70.8) and recent suicide incidents involving friends or family (OR=2.2, 95% CI=1.8–2.7) were more prevalent in the youth population (Fig 4).

Fig. 4.

Odds ratios for crises among youth (10–24 years old), as compared with adults.

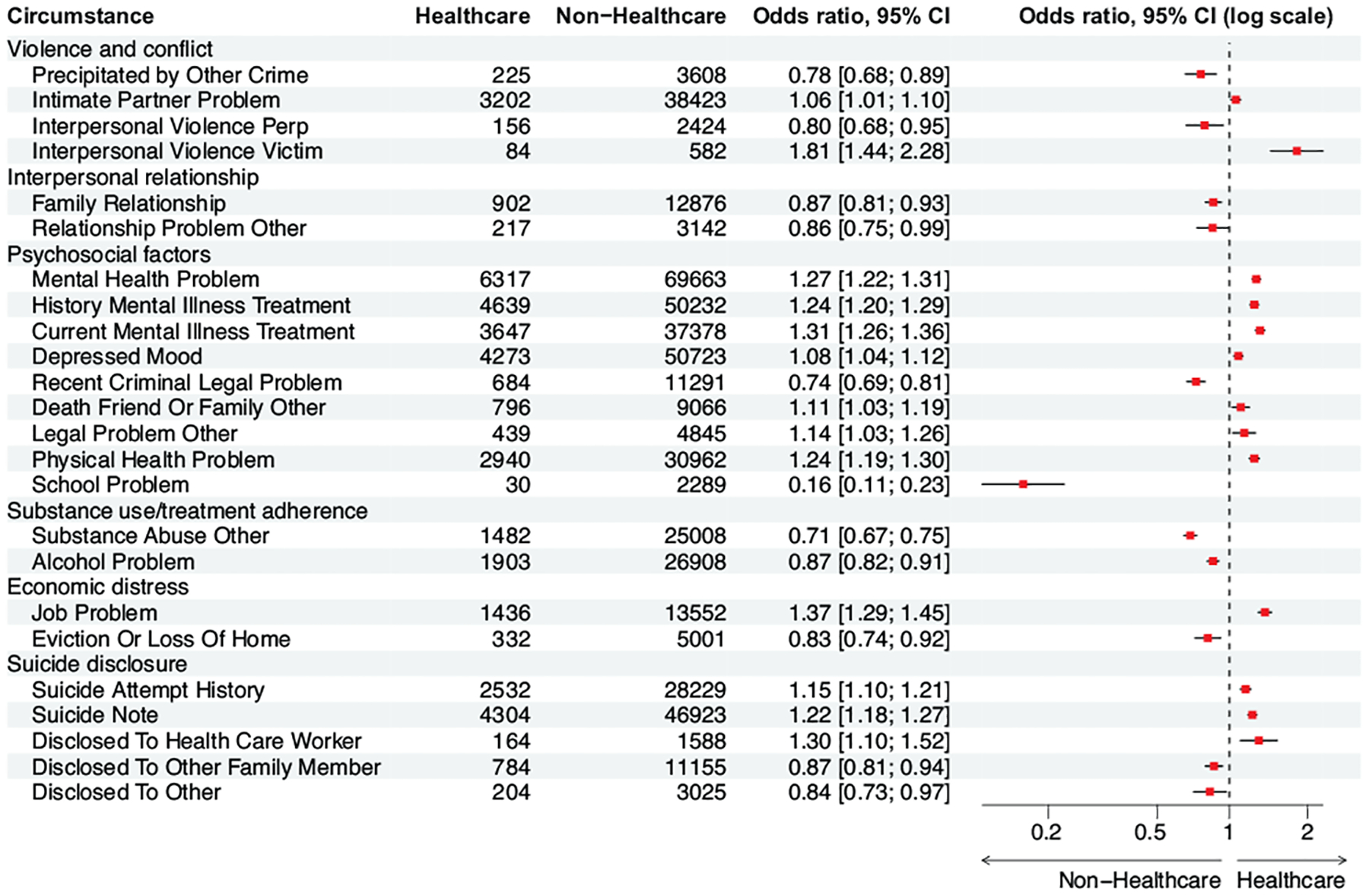

C. Leading Causes of Suicide in the Healthcare and Protective Service Workers

For Violence and conflict, victims of interpersonal violence (OR=1.8, 95% CI=1.4–2.3), as well as issues with an intimate partner (OR=1.1, 95% CI=1.0–1.1) were found to be more prevalent in healthcare and protective service workers (Fig 5). In terms of Psychosocial factors, the top circumstances included current mental illness (OR=1.3, 95% CI=1.3–1.4), past mental illness (OR=1.2, 95% CI=1.2–1.3), physical health complications (OR=1.2, 95% CI=1.2–1.3), and the death of friend or family (OR=1.1, 95% CI=1.0–1.2). Job-related problem (OR=1.4, 95% CI=1.3–1.4) was also more prevalent among those experiencing economic distress. As for Suicide disclosure, individuals working in the healthcare and protective service industry had higher odds of suicide attempt (OR=1.2, 95% CI=1.1–1.2), including leaving suicide notes (OR=1.2, 95% CI=1.2–1.3) or disclosing their suicidal thoughts to healthcare worker (OR=1.3, 95% CI=1.1–1.5).

Fig. 5.

Odds ratios for circumstances among healthcare and protective service workers, as compared with individuals not in healthcare or protective service industry.

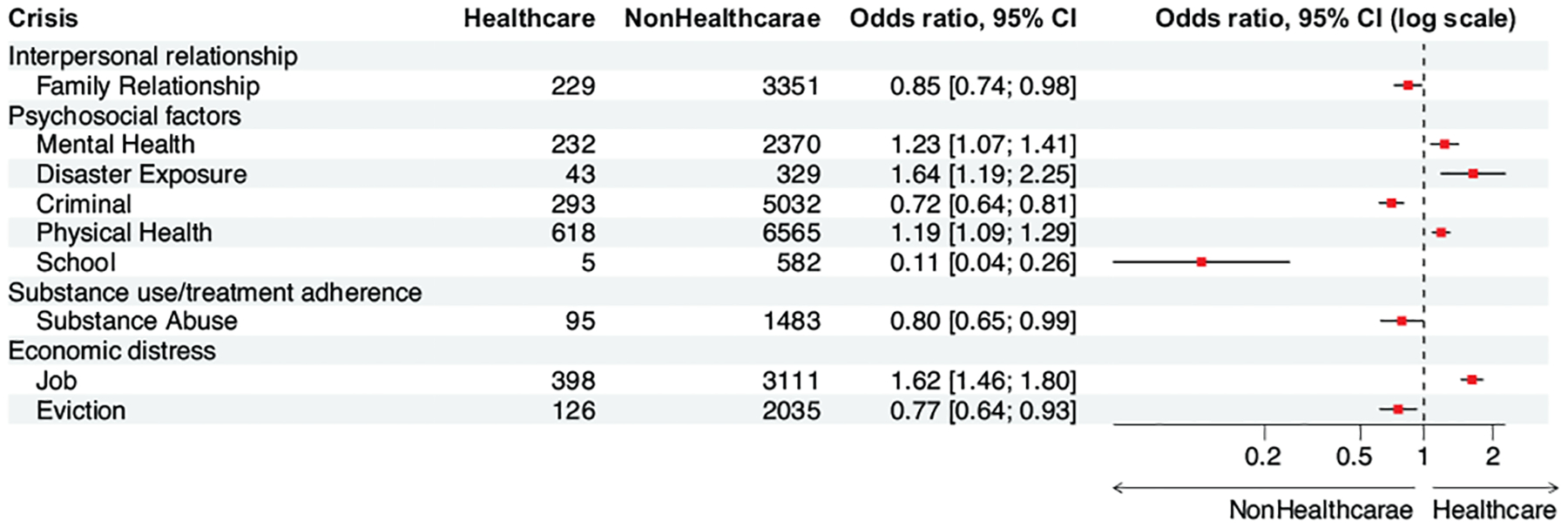

As for crises, mental health crises (OR=1.2, 95% CI=1.1–1.4) and physical health crises (OR=1.2, 95% CI=1.1–1.3) were more prevalent (Fig 6). Also, job crises (OR=1.6, 95% CI=1.5–1.8) appeared to be more prevalent in relation to Economic distress.

Fig. 6.

Odds ratios for crises among healthcare and protective service workers, as compared with individuals not in healthcare or protective service industry.

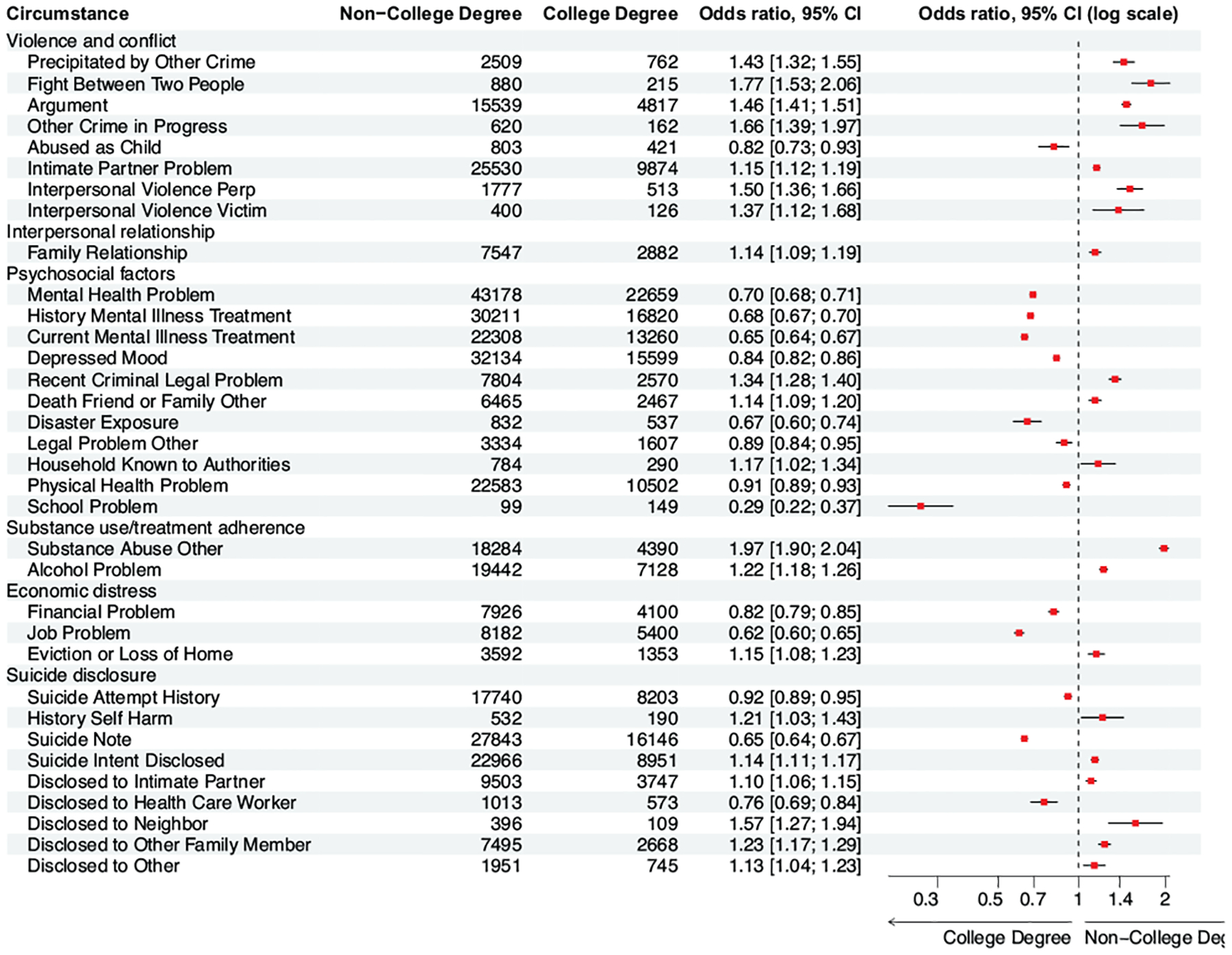

D. Leading Causes of Suicide in Adults without a College Degree

For Violence and conflict, the top three circumstances for adults without a college degree were fighting between two people (OR=1.8, 95% CI=1.5–2.1), in-progress crime (OR=1.7, 95% CI=1.4–2.0), and interpersonal violence perpetrator (OR=1.5, 95% CI=1.4–1.7) (Fig 7). For Interpersonal relationship, family relationship problems (OR=1.1, 95% CI=1.1–1.2) were found to be more prevalent among adults without a college degree. In terms of Psychosocial factors, adults without a college degree had higher odds of having recent criminal or legal problems (OR=1.3, 95% CI=1.3–1.4) and the death of a friend or family member (OR=1.1, 95% CI=1.1–1.2). Additionally, households with non-college degree adult decedents were more likely to have had contact with local authorities in the past 12 months (OR=1.2, 95% CI=1.0–1.3). For Substance use, alcohol problems (OR=1.2, 95% CI=1.2–1.3) and other substance abuse problems (OR=2.0, 95% CI=1.9–2.0) were more prevalent among this group. For Economic distress, non-college degree adults were more likely to have suffered from eviction or home loss (OR=1.2, 95% CI=1.1–1.2). Finally, these individuals had higher odds of having had a history of self-harm (OR=1.2, 95% CI=1.0–1.4), and were more likely to have disclosed their suicide intent to a neighbor (OR=1.6, 95% CI=1.3–1.9) or a family member (OR=1.2, 95% CI=1.2–1.3).

Fig. 7.

Odds ratios for circumstances among adults without a college degree, as compared with adults with at least a college degree.

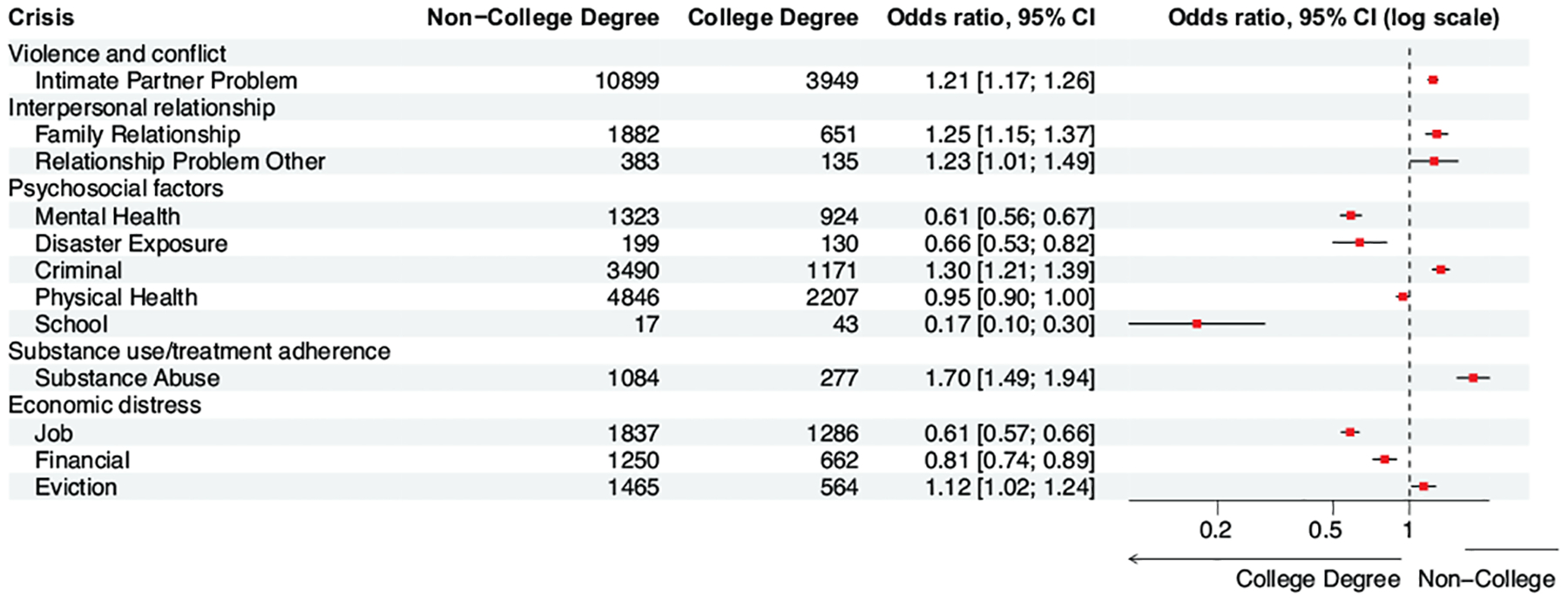

For crises, adults without a college degree were more likely to have had intimate partner problems (OR=1.2, 95% CI=1.2–1.3) in the Violence and conflict category. For Interpersonal relationship, these individuals had higher odds of family relationship crises (OR=1.3, 95% CI=1.1–1.4), or other relationship problem crises (OR=1.2, 95% CI=1.0–1.5). For Psychosocial issues, criminal crises (OR=1.3, 95% CI=1.2–1.4) were more common among this group. For Substance use, non-college degree adults were more likely to have had substance abuse crises (OR=1.7, 95% CI=1.5–1.9). Finally, in terms of Economic distress, eviction crises (OR=1.1, 95% CI=1.0–1.2) were found to be more prevalent (Fig 8).

Fig. 8.

Odds ratios for crises among adults without a college degree, as compared with adults with at least a college degree.

E. Leading Causes of Suicide for Black Youth

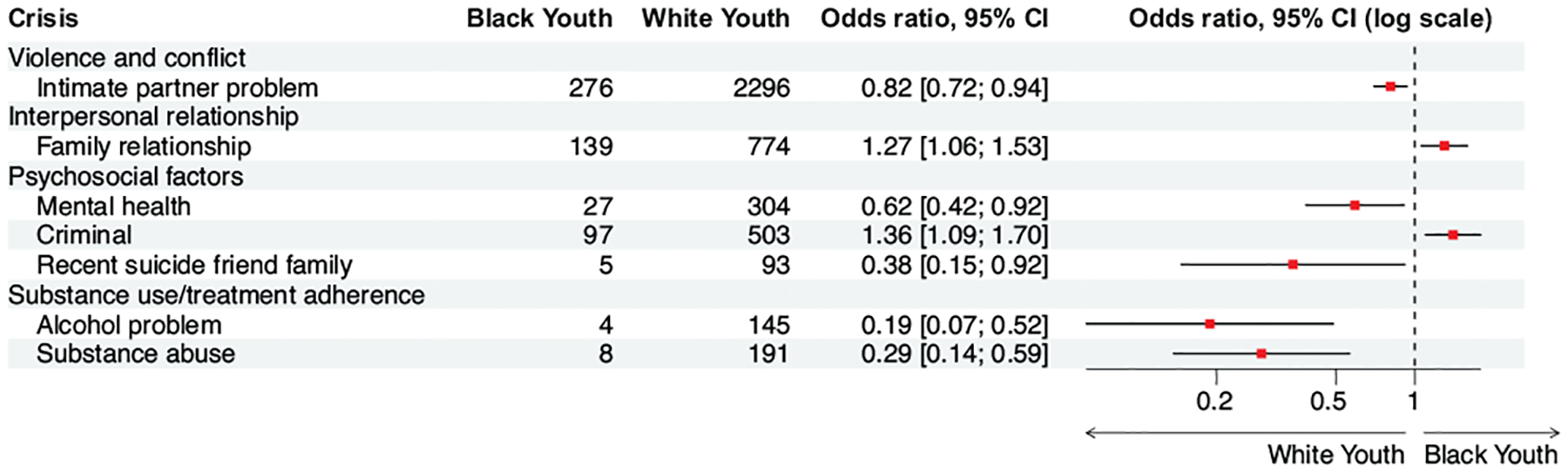

Besides analyzing individual subgroups, we also conducted experiments on intersectional data to better understand how social factors affected youths of color (Fig 9). Compared to White youth, Black youth were more affected by Violence and conflict factors such as in-progress crime (OR = 3.3, 95% CI = 2.2–5.1) and other serious crimes, specifically felonies (e.g., drug dealing, robbery) (OR = 1.9, 95% CI = 1.6–2.4), as well as interpersonal violence perpetrator (OR = 1.5, 95% CI = 1.1–2.0). For Psychosocial factors, Black youth were more likely to have encountered recent criminal or legal issues (OR = 1.2, 95% CI = 1.0–1.4). In terms of Economic distress, Black youths who committed suicide had a higher probability of having experienced transitional living situations (OR = 5.0, 95% CI = 1.6–15.8) and eviction or loss of home (OR = 1.5, 95% CI = 1.1–1.9) compared to their White youth counterparts.

Fig. 9.

Odds ratios for circumstances among Black youth, as compared with White youth.

Compared to White youths, Black youths had higher odds of having experienced criminal crises (OR = 1.4, 95% CI = 1.1–1.7) and family relationship crises (OR = 1.3, 95% CI = 1.1–1.5).

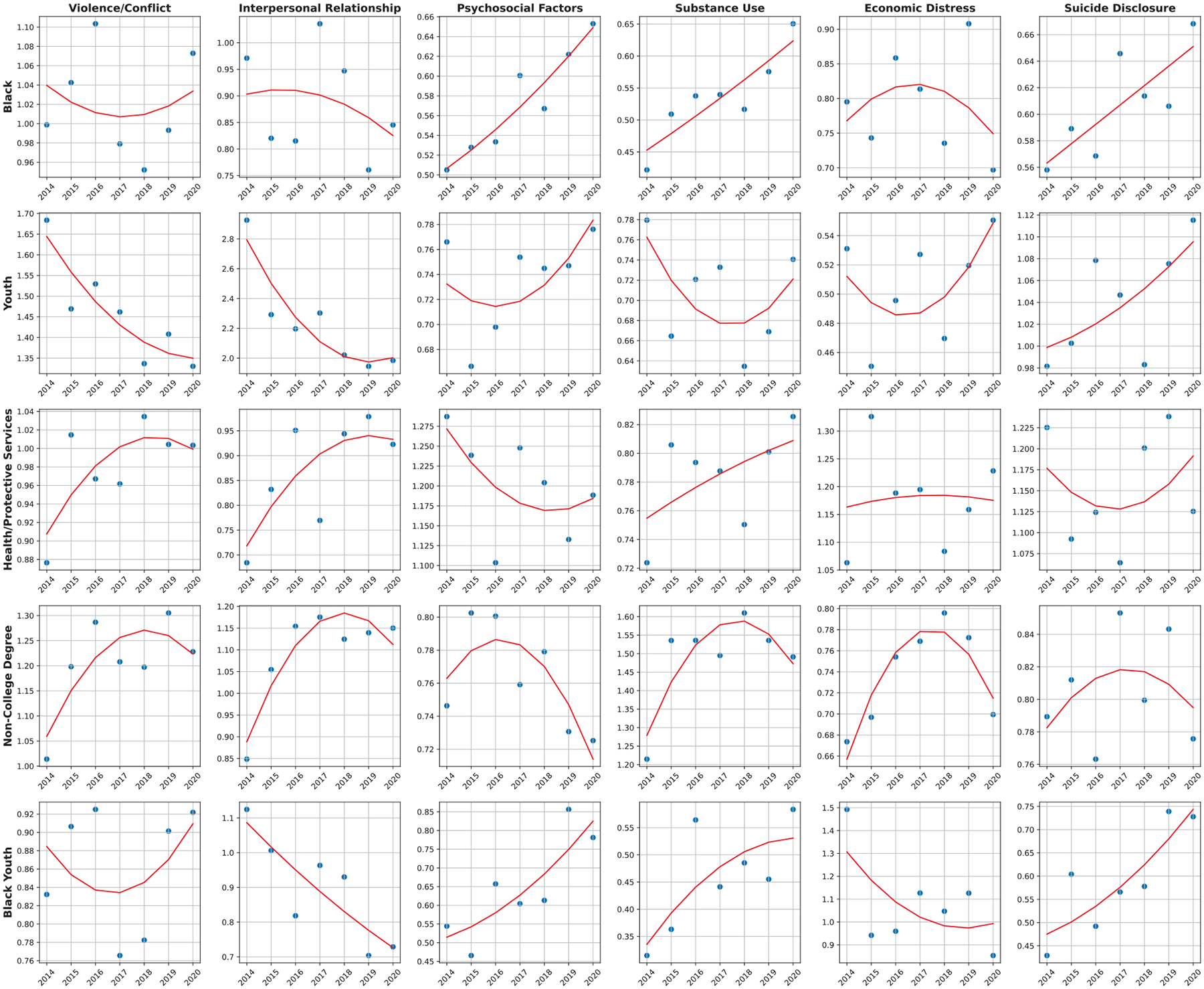

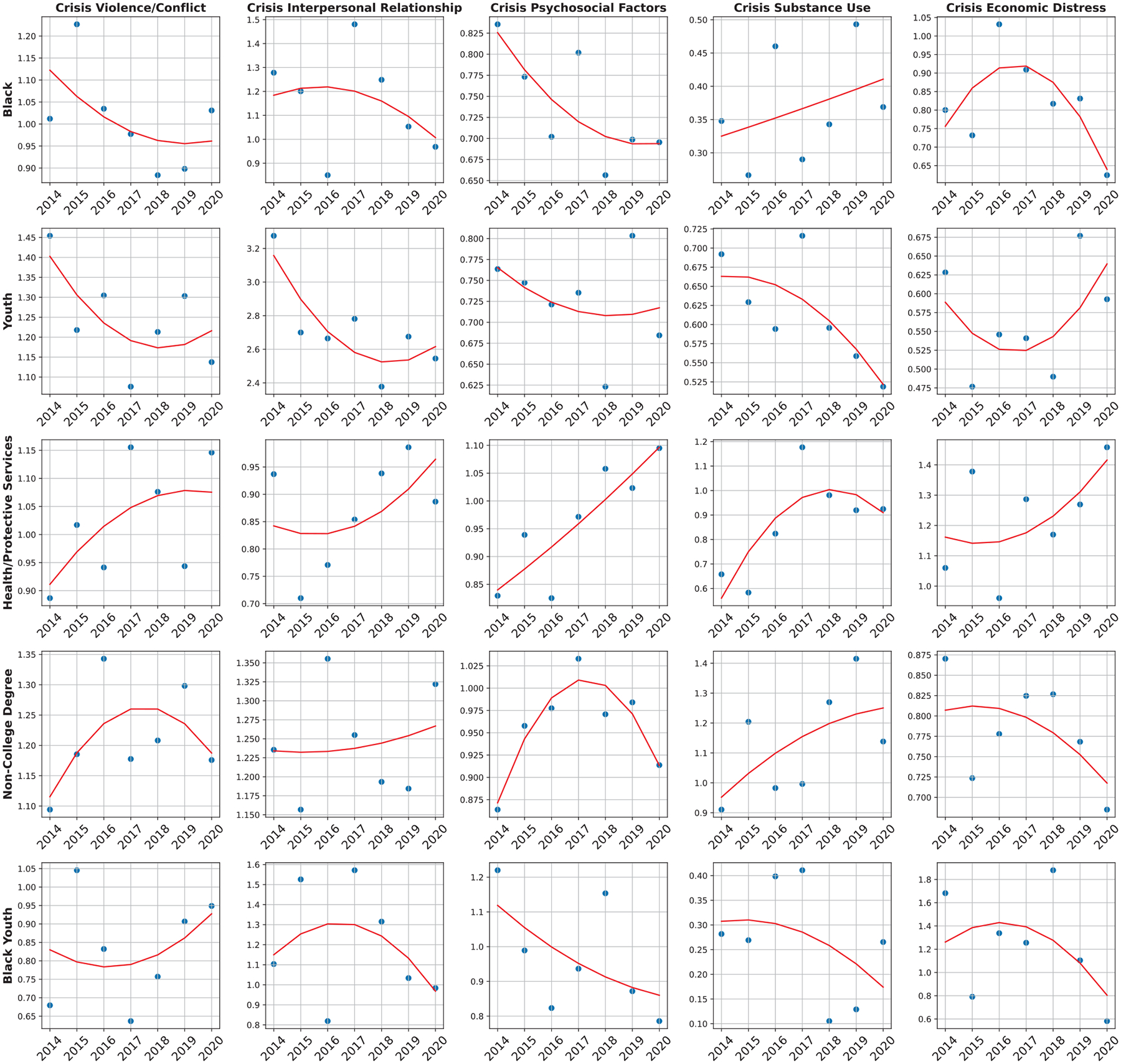

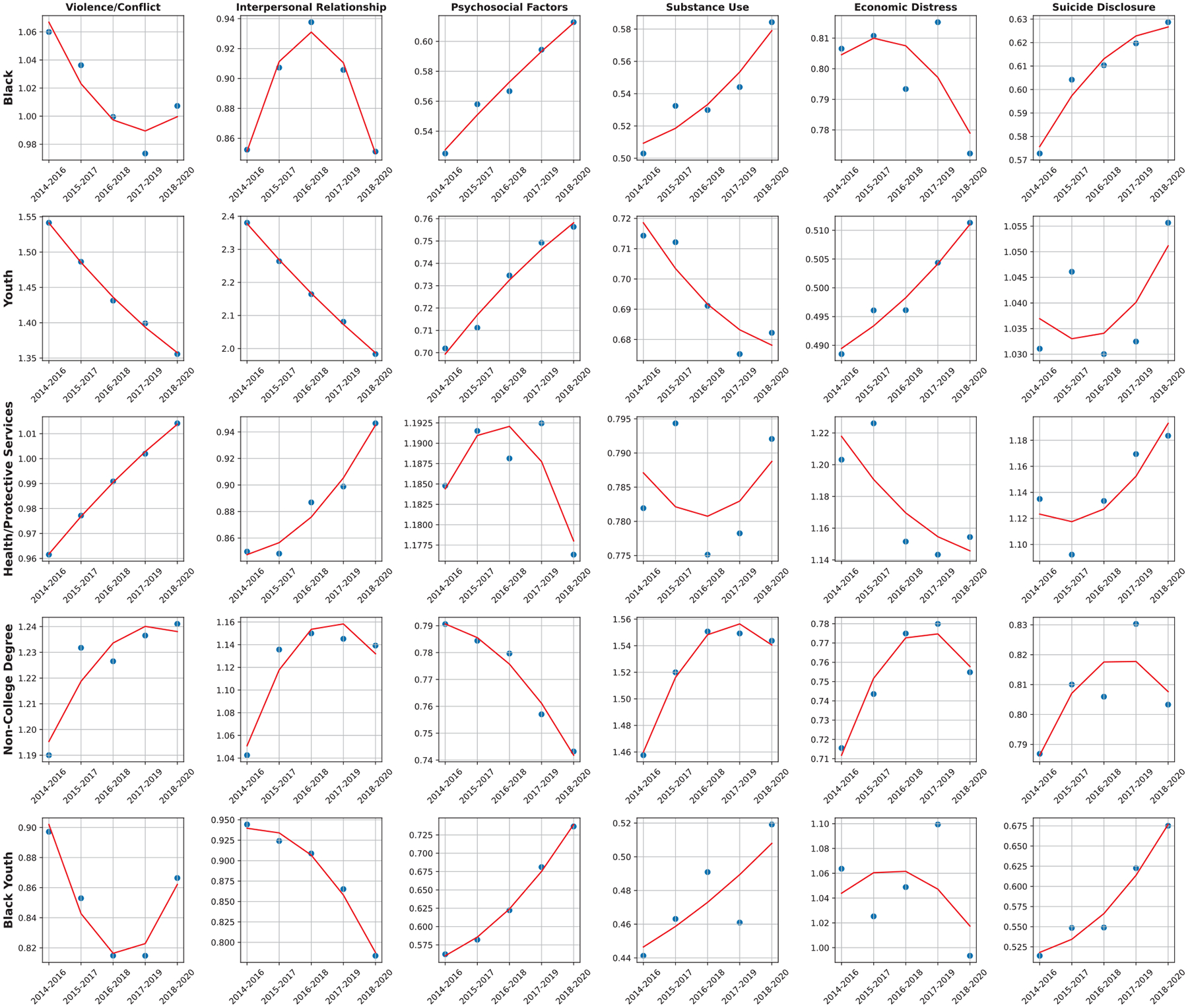

F. Trends of Social Risks

From 2014 to 2020, there has been a noticeable decline in the OR for Violence and conflict circumstances faced by youth suicide decedents, reducing from 1.7 in 2014 to 1.3 by 2020 (Fig 11). Similarly, the OR for Interpersonal relationship factors among youth decedents has declined from 2.9 in 2014 to 2.0 in 2020. Meanwhile, an increasing trend has been observed in the OR for Suicide disclosure among youth decedents.

Fig. 11.

The OR trends for each comparison group based on the six main circumstance categories.

For adult decedents without a college degree, the OR for Violence and conflict has stayed consistent at around 1.2–1.3 since 2015. For Interpersonal relationship circumstances, the OR has increased from 0.8 in 2014 to 1.1–1.2 in recent years. The OR for Substance use and Treatment adherence circumstances has similarly remained around 1.5 since 2015.

In terms of crises, from 2014 to 2020, there has been a decline in the OR for Violence and conflict crises among youth decedents, dropping from 1.5 in 2014 to 1.1 in 2020 (Fig 12). For individuals with health and protective services, the OR for Psychosocial crises has increased from 0.8 in 2014 to 1.1 by 2020. For non-college degree adults, the OR for Substance abuse crises has increased from 0.9 in 2014 to 1.1 in 2020. Lastly, there has been a decrease in the OR of Psychosocial crises for Black youth, falling from 1.2 in 2014 to 0.8 in 2020. These trends highlight the changing prevalence of crises across different demographics and sectors over time.

Fig. 12.

The OR trends for each comparison group based on the five main crisis categories.

In addition, the 3-year rolling ORs are shown in Appendix Fig A.2. Specifically, we aggregated overlapping three-year intervals, namely (2014–2016), (2015–2017), (2016–2018), (2017–2019), and (2018–2020) to assess the trends in the OR of the major categories over time. By employing this rolling analysis, we aimed to mitigate the potential impact of short-term fluctuations and random variations that might occur within individual years.

G. Thematic Clusters Identified from LDA Topic Modeling

By analyzing ten distinct topics generated through LDA, we uncovered several important insights that shed light on the complex nature of suicide and its associated triggers (Table III). The first cluster of topics (1, 4, 6) highlighted the significant role of mental health and emotional factors in suicidal ideation. Our findings reinforce the well-established connection between mental health problems, such as depressed mood and mental health disorders, and the risk of suicidal thoughts. Moreover, the prevalence of substance abuse and its link to suicide attempts emphasizes the need for integrated mental health and addiction treatment approaches. Interpersonal relationships and communication emerged as another crucial theme (2, 5, 7). Arguments, intimate partner problems, and family relationships were frequently associated with suicidal ideation. Furthermore, the presence of legal problems in this cluster serves as a reminder that strained relationships can exacerbate stressful environments. Mental health treatment and disclosure were central to understanding suicidal tendencies (9, 10). Professional and school-related stressors were recurring issues in suicide cases (3, 8), reflecting the broader societal stressors that individuals face. The presence of various thematic clusters in suicidal ideation underscores the intricate web of factors that contribute to suicide.

TABLE III.

Ten topics generated from LDA clustering with top five circumstances.

| Topic | Top-5 Terms | Topic | Top-5 Terms |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Physical Health Problem Suicide Note Depressed Mood Mental Health Problem Suicide Thought History |

6 | Substance Abuse Other Alcohol Problem Suicide Attempt History Mental Health Problem Suicide Thought History |

| 2 | Argument Intimate Partner Problem Recent Criminal Legal Problem Family Relationship Alcohol Problem |

7 | Intimate Partner Problem Depressed Mood Legal Problem Other Mental Health Problem Argument |

| 3 | Job Problem Financial Problem Depressed Mood Alcohol Problem Mental Health Problem |

8 | Suicide Note Family Relationship Depressed Mood Eviction Or Loss Of Home School Problem |

| 4 | Death Friend Or Family Other Depressed Mood Disclosed To Friend Suicide Intent Disclosed Suicide Thought History |

9 | History Mental Illness Treatment Mental Health Problem Current Mental Illness Treatment Suicide Thought History Suicide Attempt History |

| 5 | Disclosed To Intimate Partner Suicide Intent Disclosed Suicide Thought History Intimate Partner Problem Argument |

10 | Suicide Intent Disclosed Disclosed To Other Family Member Suicide Thought History Disclosed To Other Depressed Mood |

IV. DISCUSSION

A. Factors Driving Disparity

In this study, we examined the relationship between the prevalence of 58 circumstances and 19 crises leading to suicide and variables such as age, race, education level, occupation. Our findings identified significant disparities in the circumstances and risk factors between Black suicide decedents and their White counterparts. For example, our results show that Black suicide decedents had significantly higher odds of circumstances related to crime and legal issues like ongoing crime activities. Also, it was observed that suicides among Blacks were more likely to have been precipitated by other crimes compared to White decedents. Previous research pointed out that Black individuals experience a greater impact on their well-being after interactions with the criminal justice system [18]. To this end, our results align with the wider discussion surrounding social inequalities among racial groups.

In terms of youth suicide, our findings revealed the associations between suicide and family-related issues like child abuse, family relationship problems, and household substance abuse. This emphasizes the crucial role a healthy family environment plays for young people. Given the importance of family-related issues in youth, it is essential to develop and implement relevant interventions to build and maintain positive and meaningful family relationships, as previous research suggests mindful parenting activities and other empirically validated parenting programs are effective at enhancing parent-child relationships and family relationship risk protections [19]. Additionally, youth decedents were found to have higher encounters with interpersonal relationship problems such as feelings of intense jealousy, severe relationship conflicts, and other relationship problems. This observation highlights the potential impact of emotional and social difficulties on the well-being of young individuals, underlining the necessity for targeted interventions and support systems to address these issues promptly. This approach encourages the development of healthy relationships among youth. Furthermore, the higher incidence of school-related issues among youth suicide decedents underscores the critical influence education environments can have in shaping the mental health outcomes of students. Our results align with a prior study that reports a negative correlation between school connectedness, academic success and suicidal thoughts, based on the 2010 Minnesota Student Survey [20].

Interestingly, we also found that while youth decedents had lower rates of substance abuse problems overall, drug involvement was more common among this group, demonstrating the unique risks faced by this population. Many factors have been found to influence drug involvement in youth, such as psychological adversities, peer influences, and family environments, forming a complex network of influences. Effective prevention programs and family-based therapies targeting at-risk individuals are necessary to develop for this population in order to reduce risks for drug involvement. Additionally, the data pointed to a trend that youth decedents were more likely to disclose their suicide intent to friends and social media. Such patterns underline the potential opportunities for early detection and intervention by closely monitoring and reporting any such suicide disclosures. This emphasizes the importance of creating awareness and establishing vigilance protocols in social and digital environments frequented by youths.

Regarding suicide among healthcare and protective service workers, previous studies have indicated that physicians typically experience higher levels of depression [6] and suicide [5], [6] than the general public. This is of great concern, as medical errors have been found to be associated with personal distress and burnout among resident physicians [21]. Our study found that healthcare workers experienced elevated rates of depressed mood, physical health crises, and an array of additional stressors. These include job-related challenges, mental health crises, and the death of close ones. These results support previous claims [7] that doctors are subject to higher degrees of personal and professional stress than the general population. Our results also indicate the importance of designing and implementing mental health care interventions specifically for health care workers for emotional support, identification of stressors, and timely response to mental health crises. Interestingly, it was found that healthcare workers were more likely to face both intimate partner problems and legal problems. These results underscore the intricate relationship between the demands of these high-stress professions and the personal struggles experienced by health workers.

B. Analysis of OR for Intersectional Groups

In recent years, there has been a significant increase in suicide rates among Black youths [15]. Our study found that compared to White youth, Black youth decedents were more likely to have been involved in criminal or legal issues and interpersonal violence. In contrast, Black youth decedents were less likely to seek mental health treatment. Many factors specific to this racial group that limit mental health services utilization have been identified in previous studies, such as stigma/shame, religion, and mental health care affordability. This discrepancy highlights a critical disparity in access to mental health care among different racial groups. The higher incidence of criminal or legal issues, coupled with a lower likelihood of seeking mental health treatment, suggests the existence of systemic barriers that hinder appropriate interventions among Black youth [15]. Addressing these disparities requires not only efforts to destigmatize mental health support within Black communities but also a comprehensive examination of structural inequalities that contribute to the higher incidence of involvement in criminal or violent situations.

For adults over the age of 25, differences in educational attainment led to significant disparities in certain suicide risk factors. In terms of educational attainment, relationship problems, such as family relationship issues or the death of a friend or family, are more common among less educated decedents, while mental health issues and job problems are more typical among college-educated decedents [22]. Our analysis also found that individuals without a college degree are more susceptible to facing intimate partner crises, engaging in criminal activities, and being involved in interpersonal violence. This suggests a noteworthy correlation between lower levels of education and an increased likelihood of experiencing various forms of violence and conflict. Furthermore, individuals with lower levels of education seem to face a higher risk of grappling with substance abuse problems, like alcohol, which could stem from a combination of socioeconomic factors, including limited access to resources and reduced awareness about the consequences of such behaviors. Finally, while individuals with lower education levels encounter fewer job and financial issues, the higher prevalence of eviction crises suggests a vulnerability within this demographic related to housing issues.

C. OR Trends for Major Circumstance Categories

Our study observed a downward trend in the OR for Violence and conflict circumstances among youth decedents. This suggests a promising change for this vulnerable group. Moreover, reducing the OR for Interpersonal relationship factors implies possible mitigation of relationship stressors contributing to suicidal outcomes among youth. These declines could reflect the effectiveness of preventive measures, educational initiatives, and community outreach to curb violence and foster healthy relationships among youth.

On the other hand, higher rates of Violence and conflict, Interpersonal relationships, and Substance use among non-college-educated adults have seen little change in the past several years since 2015. This observation underscores the persistence of certain social challenges among individuals with lower educational backgrounds, highlighting the limitations of current measures in suicide prevention for this demographic group.

D. Limitations

There are several limitations in this study. This study incorporates data from 2014 to 2020, while the NVDRS reporting system did not achieve national coverage until 2019. For example, Hawaii was excluded from the data for the years 2017, 2018, and 2020 due to incomplete case reporting. New York was not included in the 2019 data for the same reason. This means that the geographical spread covered in our analysis might limit the applicability of findings to these regions in the U.S. Secondly, for many variables in the NVDRS dataset, unknown or missing information is frequently coded as “no”, which introduces ambiguity for researchers. Details of circumstance and crisis variables are only included if the information is available in the source documents. The absence of information in the narrative does not mean that a specific circumstance was not present; it simply means that assumptions cannot be made beyond what is indicated in the source documents. Therefore, results and findings should be interpreted with caution.

Moreover, variables such as history of or treatment for mental illness may be incomplete. Often, data related to mental and physical health are derived from individuals who knew the victim rather than healthcare professionals or medical records. The data is sourced from coroner or medical examiner reports and law enforcement documents, which may gather information from informants such as friends and others. This lack of information can also result in a void of specific details on mental illnesses in this study. Finally, this study mainly focuses on odds ratios analysis, allowing comparisons between comparison groups and reference groups. However, it does not directly measure the magnitude or overall trend in the suicide rate. Future research might benefit from incorporating additional statistical techniques to understand the scale and general trajectory of suicide rates among different groups.

V. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this study’s analysis of suicide risk factors among various demographic groups provides valuable insights for future suicide prevention efforts. The disparities identified among racial groups, age cohorts, education backgrounds, and occupation sectors shed light on the multifaceted nature of suicide risk. These findings underscore the need to address the specific challenges faced by each group, such as systemic inequalities in the criminal justice system for Black individuals, family and relationship issues for at-risk youth, and the unique stressors faced by healthcare professionals and individuals with limited education backgrounds.

Fig. 10.

Odds ratios for crises among Black youth, as compared with White youth.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Library of Medicine under Award No. 4R00LM013001, NSF CAREER Award No. 2145640, Amazon Research Award, and National Institutes of Health Aim-Ahead Award No. OT2OD032581.

Appendix

Fig. A.1.

Data filtering of the NVDRS dataset.

Fig. A.2.

The three-year rolling average of the OR trends for each comparison group based on the six main circumstance categories.

References

- [1].WHO. Suicide; 2023. Accessed: 2023-8-17. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide.

- [2].Ivey-Stephenson AZ, Crosby AE, Jack SPD, Haileyesus T, Kresnow-Sedacca MJ. Suicide Trends Among and Within Urbanization Levels by Sex, Race/Ethnicity, Age Group, and Mechanism of Death — United States, 2001–2015. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017. Oct;66(18):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bridge JA, Asti L, Horowitz LM, Greenhouse JB, Fontanella CA, Sheftall AH, et al. Suicide Trends Among Elementary School–Aged Children in the United States From 1993 to 2012. JAMA Pediatr. 2015. Jul;169(7):673–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].CDC. Facts About Suicide; 2023. Accessed: 2023-8-17. https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/facts/index.html.

- [5].Dutheil F, Aubert C, Pereira B, Dambrun M, Moustafa F, Mermillod M, et al. Suicide among physicians and health-care workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2019;14(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Mata DA, Ramos MA, Bansal N, Khan R, Guille C, Di Angelantonio E, et al. Prevalence of Depression and Depressive Symptoms Among Resident Physicians A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015. Dec;314(22):2373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kalmoe MC, Chapman MB, Gold JA, Giedinghagen AM. Physician Suicide: A Call to Action. Mo Med. 2019;116(3):211. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Gold KJ, Sen A, Schwenk TL. Details on suicide among US physicians: data from the National Violent Death Reporting System. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35(1):45–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Naumovska K, Gehl A, Friedrich P, Püschell K. [Suicide among physicians–a current analysis for the City of Hamburg]. Arch Kriminol. 2014;234(5–6):145–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Gerada C. Doctors, suicide and mental illness. BJPsych Bull. 2018. Aug;42(4):165–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Raschke N, Mohsenpour A, Aschentrup L, Fischer F, Wrona KJ. Socioeconomic factors associated with suicidal behaviors in South Korea: systematic review on the current state of evidence. BMC Public Health. 2022. Jan;22(1):1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Phillips JA, Hempstead K. Differences in U.S. Suicide Rates by Educational Attainment, 2000–2014. Am J Prev Med. 2017. Oct;53(4):e123–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lorant V, Kapadia D, Perelman J, DEMETRIQ study group. Socioeconomic disparities in suicide: Causation or confounding? PLoS One. 2021. Jan;16(1):e0243895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].CDC. National Violent Death Reporting System; 2023. Accessed: 2023-7-28. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/datasources/nvdrs/index.html.

- [15].Sheftall AH, Vakil F, Ruch DA, Boyd RC, Lindsey MA, Bridge JA. Black Youth Suicide: Investigation of Current Trends and Precipitating Circumstances. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022. May;61(5):662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wang S, Dang Y, Sun Z, Ding Y, Pathak J, Tao C, et al. An NLP approach to identify SDoH-related circumstance and suicide crisis from death investigation narratives. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2023. Apr. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Liu L, Tang L, Dong W, Yao S, Zhou W. An overview of topic modeling and its current applications in bioinformatics. SpringerPlus. 2016;5(1):1–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Blankenship KM, del Rio Gonzalez AM, Keene DE, Groves AK, Rosenberg AP. Mass Incarceration, Race Inequality, and Health: Expanding Concepts and Assessing Impacts on Well-Being. Soc Sci Med. 2018. Oct;215:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Coatsworth J, Duncan L, Greenberg M, Nix R. Changing Parent’s Mindfulness, Child Management Skills and Relationship Quality With Their Youth: Results From a Randomized Pilot Intervention Trial. Journal of child and family studies. 2010. April;19:203–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Borowsky IW, Taliaferro LA, McMorris BJ. Suicidal Thinking and Behavior Among Youth Involved in Verbal and Social Bullying: Risk and Protective Factors. J Adolesc Health Care. 2013. Jul;53(1):S4–S12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].West CP, Huschka MM, Novotny PJ, Sloan JA, Kolars JC, Habermann TM, et al. Association of Perceived Medical Errors With Resident Distress and Empathy: A Prospective Longitudinal Study. JAMA. 2006. Sep;296(9):1071–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Phillips JA, Robin AV, Nugent CN, Idler EL. Understanding Recent Changes in Suicide Rates Among the Middle-aged: Period or Cohort Effects? Public Health Rep. 2010;125(5):680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]