Abstract

A duplication of the polypurine tract (PPT) at the center of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) genome (the cPPT) has been shown to prime a separate plus-strand initiation and to result in a plus-strand displacement (DNA flap) that plays a role in nuclear import of the viral preintegration complex. Feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) is a lentivirus that infects nondividing cells, causes progressive CD4+ T-cell depletion, and has been used as a substrate for lentiviral vectors. However, the PPT sequence is not duplicated elsewhere in the FIV genome and a central plus-strand initiation or strand displacement has not been identified. Using Southern blotting of S1 nuclease-digested FIV preintegration complexes isolated from infected cells, we detected a single-strand discontinuity at the approximate center of the reverse-transcribed genome. Primer extension analyses assigned the gap to the plus strand, and mapped the 5′ terminus of the downstream (D+) segment to a guanine residue in a purine-rich tract in pol (AAAAGAAGAGGTAGGA). RACE experiments then mapped the 3′ terminus of the upstream plus (U+)-strand segment to a T nucleotide located 88 nucleotides downstream of the D+ strand 5′ terminus, thereby identifying the extent of D+ strand displacement and the central termination sequence of this virus. Unlike HIV, the FIV cPPT is significantly divergent in sequence from its 3′ counterpart (AAAAAAGAAAAAAGGGTGG) and contains one and in some cases two pyrimidines. An invariant thymidine located −2 to the D+ strand origin is neither required nor optimal for codon usage at this position. Although the mapped cPPTs of FIV and HIV-1 act in cis, they encode homologous amino acids in integrase.

During infection of a cell by a retrovirus, reverse transcription converts the encapsidated genomic mRNA to a double-stranded DNA molecule, which is then integrated into the host genome. A host-derived tRNA primes minus-strand synthesis, yielding a (−)DNA-(+)RNA duplex. The primer used to initiate subsequent plus-strand DNA synthesis is derived from the remnant of genomic RNA in this hybrid molecule through specific reverse transcriptase-associated RNase H cleavage of the RNA at the polypurine tract (PPT), a short (ca. 11 to 19 nucleotides [nt]) string of purines located at the upstream border of the 3′ long terminal repeat (31; for reviews, see references 6 and 34). For clarity, this PPT is referred to subsequently as the U3PPT.

The lentiviruses visna and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), as well as human and simian spumaviruses, contain precise copies of their U3PPTs within the distal end of the pol open reading frame (ORF) (28, 36). A plus-strand gap has been detected at this central duplication (cPPT) in the preintegration complexes of each of these viruses, corresponding to a second site of plus-strand initiation (2, 8, 13, 18, 21, 22, 30, 35). After the second strand transfer, the net result of cPPT use in reverse transcription is formation of two discrete half-genomic DNA segments in the plus strand of the preintegration complex. A short region of downstream (D+) strand displacement also occurs when upstream (U+) strand synthesis terminates at the central termination sequence (CTS) ca. 100 nt beyond the origin of the HIV-1 D+ strand (9). The resulting overlap of 88 to 98 nt in the HIV-1 preintegration complex has been termed the central DNA flap (9).

A series of studies have elucidated a requirement for the cPPT and CTS for optimal replication of HIV-1 (7, 9, 17, 38). Evidence exists for a specific role in facilitation of HIV-1 nuclear import in both dividing and nondividing cells (38). In a recently proposed model based on this evidence (38), cPPT-minus viruses become blocked at the step of nuclear translocation; both replicating virus studies and experiments with replication-defective HIV-1 vectors have lent support to this model (10, 38). In addition to this nucleotide-level, cis-acting mechanism, peptide signals in the HIV-1 matrix, integrase, and Vpr proteins have been implicated in nuclear translocation of the preintegration complex (reviewed in reference 11). Notably, a recently identified signal in HIV-1 integrase displays a phenotype similar to the central DNA flap since it functions in both dividing and nondividing cells (3). While the relative importance of these mechanisms has engendered debate, the existence of more than one pathway to facilitate nuclear import is compatible with a view that redundant mechanisms have evolved in lentiviruses to ensure infection of nondividing cell targets (e.g., macrophages, an important reservoir for all lentiviruses in vivo) (4, 11). This ability to traverse an intact nuclear membrane is not shared by type C (e.g., murine leukemia) viruses and vectors, which require disassembly of the nuclear membrane during mitosis to complete infection (24).

Feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) is an AIDS-causing lentivirus that infects nondividing cells, and vector systems capable of transducing such cells have been derived from FIV (26). However, although many similarities exist between FIV and HIV-1, such as similar disease causation and use of common chemokine receptors (25, 37), there has been little specific study of the intermediate structures that are generated during reverse transcription by FIV. Whether FIV also uses a cPPT or other second site of plus-strand initiation upstream of the U3PPT has been unknown. The FIV U3PPT has been located by analogy but has not been specifically mapped, and the termini of unintegrated FIV genomes or strong-stop DNAs have not been studied; therefore, the actual ribonucleotides involved in plus-strand strong-stop DNA priming have not been identified. Assuming from analogy to other retroviruses that FIV reverse transcription results in an unintegrated linear molecule from which two terminal nucleotides are removed prior to integration, the probable site of (+) strong-stop DNA initiation can be inferred to be the A nucleotide located −2 in relation to the start of U3 (see Fig. 1A). A 19-nt U3PPT sequence (AAAAAAGAAAAAAGGGTGG) that is highly conserved between FIV strains is located immediately upstream. Analysis of feline lentivirus nucleotide sequences available in the GenBank database identified multiple oligopurine runs in pol but no copies of the FIV U3PPT or regions with significant nucleotide sequence homology. We therefore began by investigating whether a single-strand discontinuity could be detected in the FIV preintegration complex.

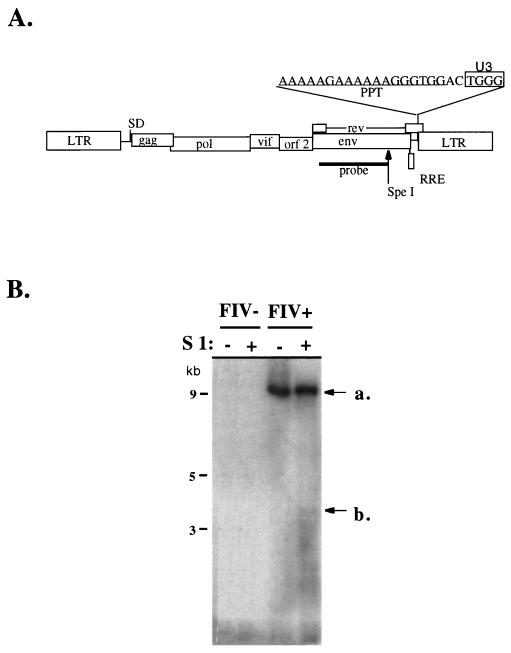

FIG. 1.

S1 nuclease analysis of LMW DNA from FIV-infected and uninfected cells. (A) Structure of provirus showing the sequence of the U3PPT (underlined) and the nearby sequence. U3 element nucleotides present in integrated proviruses are boxed. The Southern blot probe used in the S1 nuclease analysis (Fig. 1B) is illustrated. The SpeI site is unique. (B) Southern blot of S1 nuclease-digested and undigested unintegrated DNA from infected and uninfected cells. A band is detectable at ca. 3.3 kb in S1 nuclease-digested Hirt DNA from infected cells. The band is not present in the absence of S1 nuclease treatment in Hirt DNAs from infected cells or in either uninfected cell Hirt DNA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Numbering of the FIV genome follows the method of Talbott et al. (33). 293T cells and Crandell feline kidney cells (CrFK) were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium with 10% fetal calf serum. Virions were produced by transient transfection of chimeric FIV clones into 293T cells as previously described (25, 26).

To maximize survival of heavily infected CrFK cells for the recovery of preintegration complexes, as well as to maximize infectious virus production from 293T cells, a single round of infection was carried out with pseudotyped virions produced with CT5efs. CT5efs (“efs” represents “envelope frameshift”) is a proviral plasmid that contains an env-frameshifting 29-bp insertion at nt 7146 of the full-length proviral construct CT5 (25). CT5 expresses FIV 34TF10 (33) in human cells from a previously described (25, 26) fusion of the cytomegalovirus immediate-early promoter between the TATA box and the viral R repeat. The frameshift in CT5efs prevents the extensive cytopathicity that results in all CXCR4+ cells from expression by CT5 of the Env protein (25), while maintaining a full-length genome suitable for unbiased detection of potential cis-acting elements involved in reverse transcription. Env function was supplied by pseudotyping in trans with the VSV-G expression plasmid, pCMV-G (5), as described previously (26). The viral titer was scored using a focal infectivity assay that detects FIV Gag/Pol expression (29) as described previously (25).

For isolation of preintegration complexes, 1.4 × 106 CT5 virus-infected CrFK cells were plated together with 4.2 × 106 CrFK cells. At 6 h after being plated, these cells were infected with the noncytopathic pseudotyped CT5efs virus at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 7.5.

Hirt extraction, S1 nuclease digestion, and Southern blotting.

Low-molecular-weight (LMW) DNA was harvested by the method of Hirt (14) at different times after infection. DNA was digested first with SpeI and then with S1 nuclease (4 U/mg of DNA) for 1 h at 37°C in buffer containing 250 mM M NaCl, 50 mM C2H3O2Na, 1 mM ZnSO4, and 50 mg of bovine serum albumin (BSA)/ml. DNA was separated on a 1.2% agarose gel and analyzed by Southern blotting according to the scheme shown in Fig. 1A. The probe was a 32P-labeled BglII-SpeI restriction fragment spanning nt 6457 to 8287 of env.

Primer extension analysis.

5′-to-3′ primer extension was performed in reaction mixtures containing 10 μg of LMW DNA, 25 mM concentrations of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 10 U of Taq polymerase, 10 mM Tris-HCl, 15 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, and 10 pmol of a 5′-end-labeled primer (5′-ATAATAAATCCACTGTGC-3′) predicted to anneal to the plus strand about 100 bp 3′ of the approximate location of the cPPT. Reaction conditions were similar to a cycle sequencing protocol: 95°C for 30 s, 45°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 60 s, with 30 cycles of 5 min of denaturation at 95°C preceding the first cycle. Reactions were stopped with formamide loading dye. Extension reactions were run on a 6% acrylamide–7 M urea gel in parallel with Sanger sequencing reactions generated from the CT5 plasmid using the same end-labeled primer.

RACE PCR to map 3′ terminus of U+ strand.

A total of 1 μg of heat-denatured LMW DNA from infected cells and from uninfected control cells was poly(dA)-tailed by incubation with 50 U of terminal deoxynucleotide transferase at 37°C for 30 min in a 20-μl reaction mixture containing 5 M dATP, 0.75 mM cobalt chloride, 200 mM potassium cacodylate, 0.25 mg of BSA/ml, and 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.6) (12). After organic extraction and ethanol precipitation, one-third was amplified using FIV4576 (5′-CTGGTATCTGGCAAATGGATTGC-3′) and an antisense primer with a 17-bp oligo(dT) sequence (5′-TCTAGACCATGGAGATCTCGATCGTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT-3′) for 25 cycles (56°C annealing), using Platinum Taq (Gibco-BRL). Nested amplification was performed with 0.1% of the first reaction, the same oligo(dT) primer and either FIV4702 (5′-CTGTCTTACAATTGTTGAGTGC-3′) or, in the second experiment, FIV 4674 (5′-CAAGAAACTGCTGACTGTACAG-3′). Products were directly cloned and sequenced.

RESULTS

We hypothesized that a second site of plus-strand initiation in addition to the PPT would result in a plus-strand gap in the FIV preintegration complex which should not be repaired by cellular DNA-repairing enzymes until after the preintegration complex gains entry to the nucleus. Such single-strand discontinuities in the unintegrated DNA duplex have been detected for HIV-1 and visna with S1 nuclease, which cleaves single-stranded DNA selectively (2, 8, 18).

Recovery of FIV preintegration complexes in a single-round infection assay.

Detection of a plus-strand discontinuity requires isolation of adequate viral preintegration complexes, which in turn requires high-level infection of target cells. Maximal FIV titers achieved in viral preparations harvested during spreading virus infection in CrFK cells ranged from 104 to 105/ml, which limited subsequently achievable MOIs (data not shown). We previously constructed an FIV expression system (plasmid CT5 and derivatives) that enables transient high-level protein expression from genetically defined proviral constructs in transfected 293T cells (25, 26). However, initial experiments using CT5 to produce FIV 34TF10 virions in this manner revealed that it was difficult to detect preintegration complexes by Southern blotting in cells infected at MOIs of 1 or less (data not shown). In addition, as found previously (25), higher MOIs were difficult to achieve with virus produced by CT5 transfection because profuse, early, CXCR4-dependent FIV envelope protein-induced cytopathicity limits the amounts of infectious virions produced from transfected 293T cells. Fusion also begins to occur early in target CrFK cells infected at MOIs of >3 with replication-competent virus (25, 37).

Therefore, to maximize two critical parameters, i.e., yields of produced virus and peak yield of preintegration complexes in target cells, we developed a single-round infection assay that employs a VSV-G pseudotyped, env frameshifted modification of CT5 (CT5efs; see Materials and Methods). In plasmid CT5efs, a 29-nt insertion in the env ORF causes a frameshift without deletion of any FIV sequences; hence, this construct permitted unbiased analysis in the present study because it abrogates Env-induced cytopathicity but does not delete any potential internal plus-strand initiation sites. The titers of VSV-G pseudotyped, replication-defective CT5efs particles produced in 293T cells were then determined on CrFK cells by using immunoperoxidase staining for Gag/Pol. The endpoint dilution titer of unconcentrated CT5efs(VSV-G) on CrFK cells was found to be 0.9 × 107/ml, several logs higher than replication-competent virus produced either in 293T cells or after spreading infection in CrFK cells.

To maximize preintegration complex generation, uninfected CrFK cells were plated at a 3:1 ratio with chronically infected CrFK cells; 6 h later the replication-defective CT5efs(VSV-G) was used to infect the culture at an MOI of 7.5. As intended, no cytopathicity was observed in the target cells prior to harvesting the DNA samples. Preintegration complexes could be readily detected by Southern blotting as a provirus-sized band in Hirt extracts of these cells (e.g., Fig. 1B, lanes 3 and 4, top bands) but were inconsistently detected in cells infected with CrFK-produced wild-type FIV 34TF10 (data not shown).

Detection of a plus-strand discontinuity.

To isolate reverse-transcribed genomes separately from integrated viral DNA, LMW DNA was isolated by Hirt extraction (14) from the cultures at 12, 24, 42, 48, and 60 h after infection. Simultaneous control Hirt extracts were made from uninfected CrFK cells. The precipitated DNAs were pooled from the different time points for infected and uninfected cells to maximize detection of a plus-strand break. They were restricted with SpeI, which cleaves the genome once in the distal env ORF as illustrated in Fig. 1A, and then treated or not treated with S1 nuclease as described in Materials and Methods. After S1 nuclease digestion, DNAs were separated by electrophoresis and analyzed by Southern blotting with a labeled DNA probe derived from a fragment of env (Fig. 1).

As shown in Fig. 1B, a prominent 8- to 10-kb band representing reverse-transcribed unintegrated proviral DNA was detected in the Hirt extracts from infected but not uninfected CrFK cells. In addition, a band of ca. 3.5 kb was detectable in the S1 nuclease-digested LMW DNA from infected cells, but not in LMW DNA from uninfected cells or from infected cells in the absence of S1 nuclease treatment. The size of this band suggested a single strand gap in the center of the genome. The approximate location was estimated to be the 3′ region of pol, a region consistent with the location of previously described cPPTs (8, 13, 18).

Mapping of the initiation site of the internal plus-strand synthesis.

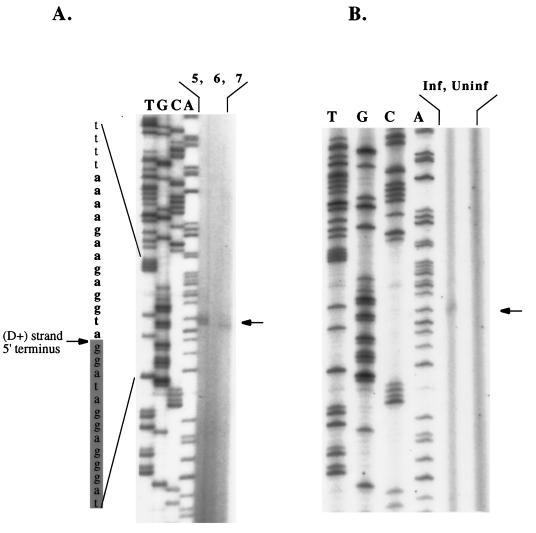

To verify the presence of a discontinuity, to map its precise location, and to establish plus- versus minus-strand polarity, we purified LMW DNA from infected and uninfected cells and performed primer extension analyses. Reactions were analyzed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in parallel with Sanger sequencing reactions performed with the same primer but using proviral plasmid DNA as a template. As shown in Fig. 2, a stop in primer extension was detected in LMW DNA from infected cells but not in LMW DNA from uninfected control cells. This stop maps the 3′ boundary of the putative gap (i.e., the 5′ terminus of the internally initiated D+ strand) to a G residue in a purine-rich tract in pol (nt 4972; underlined G in AAAAGAAGAGGTAGGA). The stop was detected in three separate primer extension reactions under the same conditions. In one reaction (Fig. 2A, lane 5), a doublet band was seen, with the upper band corresponding to the A nucleotide immediately 5′ to the underlined G. In two of the three reactions, the lower band was seen (Fig. 2A, lane 7, and Fig. 2B). The doublet detected in one of the three reactions may result from heterogeneous initiation of the D+ strand at both the A and G residues or from an extra adenine nucleotide added artifactually by Taq polymerase (12) in this primer extension.

FIG. 2.

Primer extension analysis identifies the 5′ terminus of the D+ strand. The deduced D+ strand is shaded gray at left. The stop was detected in each of three separate primer extension reactions, which are shown in lanes 5 and 7 in panel A and in the second lane from right in panel B. See the text for discussion of the doublet in panel A, lane 5. A termination band was not seen in control, uninfected cell LMW DNAs analyzed in parallel (A, lane 6, and B, right lane).

The identified 16-nt sequence (AAAAGAAGAGGTAGGA; designated the FIV cPPT hereafter) is located centrally at nt 4959 to 4974. The D+ strand origin at nt 4972 is 235 nt 3′ of the precise center of the 9,474-nt provirus and 269 nt 5′ of the terminus of pol. The cPPT is a run of mostly purines in the distal portion of the integrase gene. A comparison of this sequence with the same region in other FIV strains and in other lentiviruses is shown in Table 1. An invariant pyrimidine (a thymidine nucleotide) is located −2 to the gap, and some FIV cPPTs contain an additional pyrimidine (a C nucleotide). Additional properties of the cPPT are discussed and compared to sequences in other viruses in the Discussion.

TABLE 1.

Alignment of the identified FIV 34TF10 cPPT with polypurine regions in retroviruses and lentiviral and spumaviral cPPT region comparison

| Analysis group and virus or clonea | Function mappedb | Sequencec | Predicted aa sequenced |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integrase gene alignment | |||

| Primate lentivirus group | |||

| HIV-1 | Yes (8) | TTTTAAAAGAAAAGGGGGGATTGGG | KRKGGIG |

| HIV-2Ben | No | TTTTAAAAGAAGGGGAGGAATAGGG | KRKGGIG |

| SIVmac239 | No | TTTTAAAAGAAGGGGAGGAATAGGG | KRRGGIG |

| SVImac251 | No | TTTTAAAAGAAGGGGAGGAATAGGG | KRRGGIG |

| Feline lentivirus group | |||

| FIV34Tf10 | Yese | TTTTAAAAGAAGAGGTAGGATAGGA | KRRGRIG |

| FIVPPR | No | TTTTAAACAAAGGGGTAGAATAGGA | KQRGRIG |

| FIVNCSUJSY | No | CTTTAAACAAAGGGGTAGACTAGGA | KQRGRLG |

| FIV Oma | No | CTTTAAACAAAGGGGTAGAATAGGG | KQRGRIG |

| FIVZ1 | No | TTTTAAAAGAAGAGGTAGGATAGGA | KRRGRIG |

| FIVTM2 | No | TTTTAAACAAAGGGGTAGACTAGGG | KQRGRLG |

| FIVGVEPX | No | TTTTAAACAAAGGGGTAGACTAGGG | KQRGRLG |

| Ungulate lentivirus group | |||

| Visna virus | Yes (13) | ATATAAAAAGAAAGGGTGGGC | KRKGGLG |

| EIAV | Yes (32) | TTGTAACAAAGGGAGGGAAAGTATG | GRESMGG |

| BIV | No | AAATAAAAAAAGAGGGGGAATAGGG | KKRGGIG |

| CAEV | No | TATAAAAAGAAAGGGTGGGCTGGGG | KRKGGLG |

| Spumavirus group | |||

| HFV | Yes (22) | GTCCAGGAGAGGGTGGCTAGG | RRG |

| Retroviral U3PPT comparisons | |||

| HIV-1 | TTTTAAAAGAAAAGGGGGGACTGGAA | ||

| HIV-2Ben | TTTTATAAAAGAAAAAGGGGGACTGCAA | ||

| SIVmac239 | TTTTATAAAAGAAAAGGGGGGACTGGAA | ||

| SVImac251 | TTATAAAAGAAAAGGGGGGACTGGAA | ||

| FIV 34Tf10 | TCCTAAAAAAGAAAAAAGGGTGGACTGGGA | ||

| FIV PPR | TCCTAAAAAAGAAAAAAGGGTGGACTGGGA | ||

| FIVNCSUJSY | TCCTAAAAAAGAAAAAAGGGTGGACTGGGA | ||

| FIV Oma | AAATAAAAAGAAGGGGTGGACTGGGA | ||

| FIVZ1 | TCCTAAAAAAGAAAAAAGGGTGGACTGGGA | ||

| FIVTM2 | CTGCAAAAGAAAAAAGGGTGGACTGGGA | ||

| FIVGVEPX | CTGCAAAAGAAAAAAGGGTGGACTGGGA | ||

| Visna virus | AAAAGAAAAAAGAAAGGGTGGACTGTCA | ||

| EIAV | GTTTAGAAAAACAAGGGGGGAACTGTGGG | ||

| BIV | TTTTAAACTTAAAAGGGTGGACTGTGGG | ||

| CAEV | AAATAAAAAAAGAAAGGGTGACTGTGAG | ||

| Spuma virus | AACGAGGAGAGGGTGTGGTG | ||

| MLV | TTTTATTTAGTCTCCAGAAAAAGGGGGGAATGAAAG |

BIV, bovine immunodeficiency virus; CAEV, caprine arthritis encephalitis virus; HFV, human foamy virus; MLV, murine leukemia virus.

This column denotes whether any cPPT function in reverse transcription has been identified for the listed sequence; references are given in parentheses.

For integrase gene alignment, the cPPT sequence is indicated in boldface. For retroviral U3PPT comparisons, the U3 of the integrated provirus is underlined and the PPT is in boldface.

The predicted amino acid (aa) sequence encoded by the boldface nucleotides in column 3.

Mapped in the present study.

Identification of a CTS: the upstream plus-strand segment terminates after a short region of strand displacement synthesis.

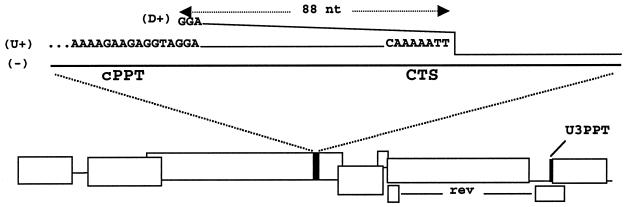

After the second strong-stop DNA transfer, synthesis of the upstream (U+) segment of the plus strand occurs. Termination of U+ synthesis could occur at or before the FIV D+ strand origin, resulting in a true gap. Alternatively, U+ strand synthesis could proceed further, causing some degree of displacement of the D+ strand previously initiated at the FIV cPPT. The latter situation occurs in HIV-1 reverse transcription, in which two predominant sites of 3′ termination (88 and 98 nt downstream) are termed the CTS and the resulting intermediate is called the central DNA flap (9). To identify 3′ termini of FIV U+ strands, anchor PCR was performed. First, terminal deoxynucleotide transferase was used to attach a homopolymeric poly(dA) tail to 3′ ends of LMW DNAs in Hirt extracts from infected cells and from uninfected control cells. Heminested PCR was then carried out with sequential use of two sense primers complementary to the minus strand several hundred nucleotides upstream of the cPPT. An antisense oligo(dT) primer complementary to the synthesized poly(dA) tail was employed in both reactions of the nested set. The resulting second-round, heminested products were directly cloned without any purification or size fractionation and then sequenced. In such an analysis, the 3′ terminus of the U+ strand is revealed by the position of the poly(dA) tail attached by terminal transferase. This assignment is unambiguous provided the terminal FIV nucleotide is not an A.

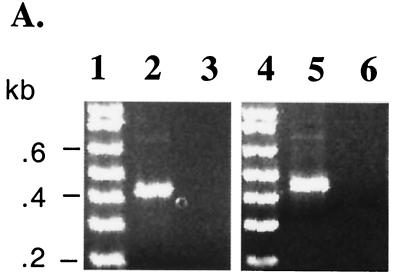

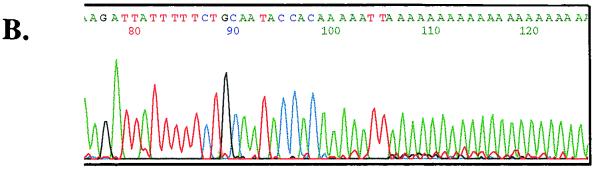

A total of 24 randomly picked insert-containing clones from two separate terminal transferase tailings and nested-PCR amplification experiments with different nesting primers were sequenced. Prior to cloning, PCR products were composed of single prominent bands (lanes 2 and 5, Fig. 3A) that placed the site of joining of the oligo(dA) tail ca. 80 to 120 nt downstream of the cPPT depending on the exact site of oligo(dT) annealing to the tail. No products were detected in amplifications of LMW DNA from uninfected cells (Fig. 3A, lanes 3 and 6). The precise 3′ terminus of the U+ strand was determined in all 24 clones to occur at the second T nucleotide in a CA5T2 sequence downstream of the cPPT. A sequence analysis of one of the anchored PCR fragments and an alignment of this region with other lentiviruses are shown in Fig. 3B and Fig. 4, respectively. Because the U+ terminus is at a T nucleotide, which in the native sequence is preceded by a T and followed by GC, the determination by poly(dA) tailing of the precise stop site is unambiguous, and further analysis with a different homopolymeric tailing than poly(dA) was not required. While a very faint band ca. 200 nt longer than the main band was seen in lanes 2 and 5 of Fig. 3A, it was not detected in any sequenced clones and resulted from nonspecific annealing of the poly(T) primer to the FIV genome because it was also seen in control amplifications of poly(dA)-tailed, uninfected cell LMW DNA spiked with 0.1 ng of FIV plasmid DNA and in amplifications of infected cell LMW DNA not subjected to poly(dA) tailing.

FIG. 3.

Identification of the CTS and alignment with other lentiviruses. (A) Heminested PCRs. Hirt DNA from infected cells (lanes 2 and 5) and uninfected cells (lanes 3 and 6) was homopolymerically tailed with dATP and terminal deoxynucleotide transferase prior to the PCR. PCR was performed with a 90-s extension time using an antisense oligo(dT)-containing primer and the following 5′ nesting primers upstream of the identified cPPT sequence (nt 4959 to 4974): an outer sense primer beginning at nt 4576 in the first round and an inner primer at either nt 4702 (left panel) or nt 4674 (right panel) in the second round. The size of the single bands produced places the site of joining of the oligo(dA) tail ca. 80 to 120 nt downstream of the cPPT depending on the exact site of oligo(dT) annealing to the tail. A very faint larger band of between 600 and 700 bp, possibly representing a minor U+ strand termination, can be seen in both panels but was not detected in any sequenced clones. (B) The site of attachment of the poly(dA) tail by terminal deoxynucleotide transferase unambiguously identifies the 3′ terminus of the U+ strand. An electropherogram from 1 of the 24 clones sequenced is shown. The CTS in the pol gene is CA5T2. No other terminations were present in 24 clones (12 were sequenced from each of the two separate amplifications shown in left and right panels of Fig. 3A).

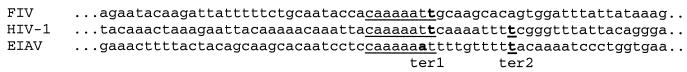

FIG. 4.

The identified FIV CTS. The CTS is aligned with those of the two other viruses for which a CTS has been established, i.e., HIV-1 (9) and EIAV (32). Termination nucleotides are in boldface. There is no significant nucleotide sequence homology downstream of the FIV cPPT except at the CTS (CA5T2, underlined), which corresponds to ter1. FIV lacks a sequence equivalent to the ter2 sites reported for HIV-1 and EIAV, a finding which is consistent with the single U+ strand 3′ terminus established in the present study.

These results establish that the outcome of FIV reverse transcription in infected cells is an unintegrated DNA molecule with a discontinuous plus strand and a central region of plus-strand displacement (Fig. 5). Two notable similarities to HIV-1 are apparent. The region of strand displacement synthesis is the same length (88 nt) as that reported for the first termination site (ter1) in HIV-1, and it occurs at an oligonucleotide sequence identical to ter1 (CAAAAATT, hereafter referred to as the FIV CTS) (9). In contrast to the CTS, the 88-nt sequence preceding it displays little homology to the analogous 88 nt in HIV-1 (Fig. 4). The ter1 stop is used in only 30% of HIV-1 U+ terminations (9), compared to 100% of FIV U+ terminations detected in the present work. The majority of HIV-1 U+ terminations occur within ter2, a CA4T4 sequence located just downstream of ter1 (Fig. 4). In addition, as illustrated in Fig. 4, two similar sites have also been found to act as strong pause determinants on synthetic plus-strand DNA templates for purified equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV) reverse transcriptase (32). FIV lacks any sequence resembling ter2, however, which is consistent with the single stop used by FIV (Fig. 4).

FIG. 5.

Structure of the central DNA flap in FIV. The minus, U+, and D+ strands are labeled, and relevant nucleotides are shown. The region of overlap is 88 nt, extending from the 5′ end of the D+ strand to the 3′ terminus of the U+ strand.

DISCUSSION

The present experiments identify both a cPPT and a CTS for FIV and show that reverse transcription in FIV-infected cells results in a preintegration complex containing a central DNA flap defined by these elements. As in HIV-1, the 16-nt (AAAAGAAGAGGTAGGA) sequence is purine-rich and is located in the distal portion of the integrase gene. However, in contrast to the situation in HIV-1, visna, and spumaviruses, the FIV cPPT mapped in the present study is considerably divergent in sequence from its 3′ counterpart (AAAAAAGAAAAAAGGGTGG). All of the feline lentivirus cPPT sequences diverge at multiple positions from their respective U3PPT sequences (Table 1).

The FIV cPPT also contains one strongly conserved pyrimidine, a thymidine residue located at position 4970, −2 relative to the G nucleotide that defines the D+ strand terminus (AAAAGAAGAGGTAGGA). This thymidine (uracil in the RNA primer) is neither required nor optimal for the glycine codon (GGU) at this position. As in other lentiviral genomes, codon usage for the 88 glycines in FIV pol is strongly biased toward a purine, particularly adenine, at the third position (GGU, 15%; GGA, 64%; GGC, 5%; GGG, 17%). GGU is also the least-favored glycine codon in overall mammalian usage (GGU, 16%; GGA, 24%; GGC, 36%; GGG, 24%) (15). The T nucleotide is highly conserved across numerous FIV strains, including FIV-OMA (1), a virus which is more closely related to lion and puma lentiviruses than to domestic cat strains. Taken together, these considerations suggest that the thymidine at position 4970 is preserved by strong selection pressure at the nucleic acid level. A conserved thymidine nucleotide is also present in the FIV U3PPT, −3 relative to the start of plus-strand strong-stop DNA synthesis. Here, however, it is required for encoding of a conserved valine residue in Rev. In the Pallas' cat and other strains of FIV, an additional pyrimidine (a C at position 4) is present in the cPPT sequence (Table 1).

Four thymidine nucleotides are located upstream of the cPPT (Table 1). A similar “U box” is present in many of the U3PPT and cPPT regions of the primate lentiviruses (16, 19, 27). However, unlike HIV-1, the U box is absent upstream of any FIV U3PPT, where TCCT or, less commonly, AAAT or CTGC is found (Table 1). When the U box is included, 20 contiguous nucleotides are exactly duplicated at the U3 and central PPTs of HIV-1 (see Table 1), a finding which underscores the sequence dissimilarity between the U3 and central PPT regions of FIV. Selection pressure for protein coding may contribute to the lack of identity between the FIV cPPT and U3PPT. While the HIV U3PPT resides within the nef, the FIV U3PPT resides within FIV rev, where it encodes a basic amino acid sequence of undetermined role (Fig. 5). These results also establish an invariant overlap in all three lentiviral groups of the cis-functioning cPPT with a conserved coding sequence (Table 1, right column), which is not fully explained by current models.

The CTS identified here for FIV is a CA5T2 sequence with termination occurring at the second T (Fig. 3), which is identical to the HIV-1 ter1 site (9) and similar to a strong pause site determined for EIAV reverse transcriptase on synthetic DNA templates (32). FIV lacks a ter2 site, which is consistent with the single termination detected in the RACE experiments. In addition, as shown in Fig. 4, the CA5T2 sequence is the only region of high nucleotide level homology between HIV-1 and FIV in the region of the integrase gene involved in the strand overlap, which is consistent with strong selection at the nucleotide level. The strand terminus observed at this particular A/T-rich duplex is also in agreement with data that specific HIV-1 DNA template sequences are capable of interrupting processive synthesis by HIV-1 reverse transcriptase (20, 23).

The functional significance of the identified flap in import of the FIV preintegration complex into the nucleus remains to be determined. We are currently investigating the influence of cPPT-CTS mutations on FIV replication and import of the FIV preintegration complex, as well as the effects of incorporating this element within FIV-based lentiviral vectors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank I. Kemler, N. Loewen, and M. Llano for helpful suggestions.

This work was supported by NIH grant R01 AI47536 (E.P.) and a Pfizer Scholars Grant for New Faculty (E.P.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Barr M C, Zou L, Holzschu D L, Phillips L, Scott F W, Casey J W, Avery R J. Isolation of a highly cytopathic lentivirus from a nondomestic cat. J Virol. 1995;69:7371–7374. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.7371-7374.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blum H E, Harris J D, Ventura P, Walker D, Staskus K, Retzel E, Haase A T. Synthesis in cell culture of the gapped linear duplex DNA of the slow virus visna. Virology. 1985;142:270–277. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(85)90335-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouyac-Bertoia M, Dvorin J, Fouchier R, Jenkins Y, Meyer B, Wu L, Emerman M, Malim M H. HIV-1 infection requires a functional integrase NLS. Mol Cell. 2001;7:1025–1035. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00240-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bukrinsky M I, Sharova N, Dempsey M P, Stanwick T L, Bukrinskaya A G, Haggerty S, Stevenson M. Active nuclear import of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 preintegration complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6580–6584. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burns J C, Friedmann T, Driever W, Burrascano M, Yee J K. Vesicular stomatitis virus G glycoprotein pseudotyped retroviral vectors: concentration to very high titer and efficient gene transfer into mammalian and nonmammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8033–8037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.8033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Champoux J. Role of ribonuclease H in reverse transcription. In: Skalka A, Goff S, editors. Reverse transcription. Cold, Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charneau P, Alizon M, Clavel F. A second origin of DNA plus-strand synthesis is required for optimal human immunodeficiency virus replication. J Virol. 1992;66:2814–2820. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.5.2814-2820.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charneau P, Clavel F. A single-stranded gap in human immunodeficiency virus unintegrated linear DNA defined by a central copy of the polypurine tract. J Virol. 1991;65:2415–2421. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.5.2415-2421.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charneau P, Mirambeau G, Roux P, Paulous S, Buc H, Clavel F. HIV-1 reverse transcription: a termination step at the center of the genome. J Mol Biol. 1994;241:651–662. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Follenzi A, Ailles L E, Bakovic S, Geuna M, Naldini L. Gene transfer by lentiviral vectors is limited by nuclear translocation and rescued by HIV-1 pol sequences. Nat Genet. 2000;25:217–222. doi: 10.1038/76095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fouchier R A, Malim M H. Nuclear import of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 preintegration complexes. Adv Virus Res. 1999;52:275–299. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60302-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frohman M. RACE: rapid amplification of cDNA ends. In: Innis M, Gelfand D, Sninsky J, White T, editors. PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1990. pp. 28–38. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris J D, Scott J V, Traynor B, Brahic M, Stowring L, Ventura P, Haase A T, Peluso R. Visna virus DNA: discovery of a novel gapped structure. Virology. 1981;113:573–583. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(81)90185-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirt B. Selective extraction of polyoma DNA from infected mouse cell cultures. Mol Biol. 1967;26:365–369. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(67)90307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holm L. Codon usage and gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:3075–3087. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.7.3075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huber H E, Richardson C C. Processing of the primer for plus strand DNA synthesis by human immunodeficiency virus 1 reverse transcriptase. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:10565–10573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hungnes O, Tjotta E, Grinde B. Mutations in the central polypurine tract of HIV-1 result in delayed replication. Virology. 1992;190:440–442. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)91230-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hungnes O, Tjotta E, Grinde B. The plus strand is discontinuous in a subpopulation of unintegrated HIV-1 DNA. Arch Virol. 1991;116:133–141. doi: 10.1007/BF01319237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ilyinskii P O, Desrosiers R C. Identification of a sequence element immediately upstream of the polypurine tract that is essential for replication of simian immunodeficiency virus. EMBO J. 1998;17:3766–3774. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.13.3766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klarmann G J, Schauber C A, Preston B D. Template-directed pausing of DNA synthesis by HIV-1 reverse transcriptase during polymerization of HIV-1 sequences in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:9793–9802. . (Erratum, 268:13764.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kupiec J J, Sonigo P. Reverse transcriptase jumps and gaps. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:1987–1991. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-9-1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kupiec J J, Tobaly-Tapiero J, Canivet M, Santillana-Hayat M, Flugel R M, Peries J, Emanoil-Ravier R. Evidence for a gapped linear duplex DNA intermediate in the replicative cycle of human and simian spumaviruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:9557–9565. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.20.9557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lavigne M, Roux P, Buc H, Schaeffer F. DNA curvature controls termination of plus strand DNA synthesis at the centre of HIV-1 genome. J Mol Biol. 1997;266:507–524. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewis P F, Emerman M. Passage through mitosis is required for oncoretroviruses but not for the human immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1994;68:510–516. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.1.510-516.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poeschla E, Looney D. CXCR4 is required by a nonprimate lentivirus: heterologous expression of feline immunodeficiency virus in human, rodent, and feline cells. J Virol. 1998;72:6858–6866. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.8.6858-6866.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poeschla E, Wong-Staal F, Looney D. Efficient transduction of nondividing cells by feline immunodeficiency virus lentiviral vectors. Nat Med. 1998;4:354–357. doi: 10.1038/nm0398-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Powell M D, Levin J G. Sequence and structural determinants required for priming of plus-strand DNA synthesis by the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 polypurine tract. J Virol. 1996;70:5288–5296. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5288-5296.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ratner L, Haseltine W, Patarca R, Livak K J, Starcich B, Josephs S F, Doran E R, Rafalski J A, Whitehorn E A, Baumeister K, et al. Complete nucleotide sequence of the AIDS virus, HTLV-III. Nature. 1985;313:277–284. doi: 10.1038/313277a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Remington K M, Chesebro B, Wehrly K, Pedersen N C, North T W. Mutants of feline immunodeficiency virus resistant to 3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine. J Virol. 1991;65:308–312. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.1.308-312.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sonigo P, Alizon M, Staskus K, Klatzmann D, Cole S, Danos O, Retzel E, Tiollais P, Haase A, Wain-Hobson S. Nucleotide sequence of the visna lentivirus: relationship to the AIDS virus. Cell. 1985;42:369–382. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80132-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sorge J, Hughes S H. Polypurine tract adjacent to the U3 region of the Rous sarcoma virus genome provides a cis-acting function. J Virol. 1982;43:482–488. doi: 10.1128/jvi.43.2.482-488.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stetor S R, Rausch J W, Guo M J, Burnham J P, Boone L R, Waring M J, Le Grice S F. Characterization of (+) strand initiation and termination sequences located at the center of the equine infectious anemia virus genome. Biochemistry. 1999;38:3656–3667. doi: 10.1021/bi982764l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Talbott R L, Sparger E E, Lovelace K M, Fitch W M, Pedersen N C, Luciw P A, Elder J H. Nucleotide sequence and genomic organization of feline immunodeficiency virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5743–5747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.15.5743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Telesnitsky A, Goff S. Reverse transcriptase and the generation of retroviral DNA. In: Coffin J, Huges S, Varmus H, editors. Retroviruses. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 121–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tobaly-Tapiero J, Kupiec J J, Santillana-Hayat M, Canivet M, Peries J, Emanoil-Ravier R. Further characterization of the gapped DNA intermediates of human spumavirus: evidence for a dual initiation of plus-strand DNA synthesis. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:605–608. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-3-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wain-Hobson S, Sonigo P, Danos O, Cole S, Alizon M. Nucleotide sequence of the AIDS virus, LAV. Cell. 1985;40:9–17. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Willett B J, Picard L, Hosie M J, Turner J D, Adema K, Clapham P R. Shared usage of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 by the feline and human immunodeficiency viruses. J Virol. 1997;71:6407–6415. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6407-6415.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zennou V, Petit C, Guetard D, Nerhbass U, Montagnier L, Charneau P. HIV-1 genome nuclear import is mediated by a central DNA flap. Cell. 2000;101:173–185. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80828-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]