Abstract

Background

Robust and accurate prediction of cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk facilitates early intervention to benefit patients. The intricate relationship between mental health disorders and CVD is widely recognized. However, existing models often overlook psychological factors, relying on a limited set of clinical and lifestyle parameters, or being developed on restricted population subsets.

Objectives

This study aims to assess the impact of integrating psychological data into a novel machine learning (ML) approach on enhancing CVD prediction performance.

Methods

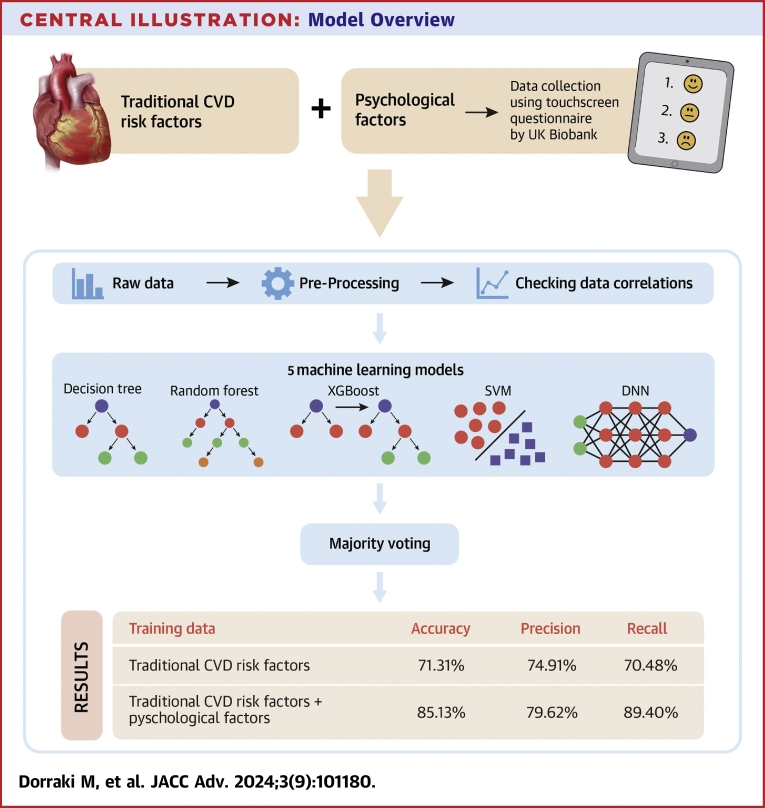

Using a comprehensive UK Biobank data set (n = 375,145), the correlation between CVD and traditional and psychological risk factors was examined. CVD included hypertensive disease, ischemic heart disease, heart failure, and arrhythmias. An ensemble ML model containing 5 constituent algorithms (decision tree, random forest, XGBoost, support vector machine, and deep neural network) was tested for its ability to predict CVD based on 2 training data sets: using traditional CVD risk factors alone, or using a combination of traditional and psychological risk factors.

Results

A total of 375,145 subjects with normal health status and with CVD were included. The ensemble ML model could predict CVD with 71.31% accuracy using traditional CVD risk factors alone. However, by adding psychological factors to the training data, accuracy increased to 85.13%. The accuracy and robustness of the ensemble ML model outperformed all 5 constituent learning algorithms.

Conclusions

Incorporating mental health assessment data within an ensemble ML model results in a significantly improved, highly accurate, CVD prediction model, outperforming traditional risk factor prediction alone.

Key words: artificial intelligence, cardiovascular disease, cardiovascular prediction, machine learning, mental health

Central Illustration

Coronary heart disease and cerebrovascular disease are the world’s leading cause of death.1 Early intervention is highly effective for people at risk of developing the disease, and a widely used approach is to screen at-risk populations.2 Several cardiovascular disease (CVD) prediction models have been developed during the past 4 decades. The Reynolds Risk Score in women, used in the United States, is based on data from the Women’s Health Study.3 Another multi-marker risk model assesses the contribution of 10 genetic markers, including B-type natriuretic peptide and C-reactive protein.4 SCORE (Systematic Coronary Risk Evaluation), introduced by the European Society of Cardiology, was developed retrospectively from data originating from 12 European cohorts undergoing baseline examination.5 QRISK, a cardiovascular risk prediction algorithm, is recommended in Europe for estimating the risk of heart attacks and strokes in a given population.6,7

Most prediction models follow a statistical regression approach that relates CVD risk with an individual’s characteristics,8 but the number of factors used for prediction is often limited. New approaches, covering a more comprehensive range of markers that do not rely solely on traditional clinical and lifestyle factors, could improve precision in identifying CVD risk.

The pooled cohort equations were created later and served as gender- and race-specific tools designed for estimating the 10-year absolute rates of atherosclerotic CVD events in primary prevention populations in individuals without prior atherosclerotic CVD incorporating gender and race.9 Over the past few decades, these models have been extensively validated within different populations, which provided mounting evidence that local tailoring is often necessary to obtain accurate predictions.10

The Framingham Risk Score is a cornerstone and extensively employed method for estimating the 10-year likelihood of experiencing cardiovascular events, especially coronary heart disease, among individuals without pre-existing CVDs.11 Over time, the Framingham Risk Score has been refined through successive updates to improve its accuracy and broaden its relevance to various populations. This has solidified its role as a critical tool in clinical settings for categorizing risk levels and guiding decisions on preventive measures.

In addition to traditional, recognized risk factors for CVD, such as smoking, high cholesterol levels, hypertension (HT), and obesity, there is also evidence of a significant association between psychological factors and CVD.12 The association is bidirectional, in that psychological factors may be common in certain CVDs and portend worse outcomes, regardless of whether the psychological disorder or CVD occurs first.13

The important role of psychological stress has been previously investigated in myocardial ischemia,14 coronary artery disease,15,16 acute and reversible cardiomyopathy,17 and ventricular arrhythmias.18 Prospective evidence implies that depression plays a major role in CVD development.19,20 The association of depression has also been reported with coronary artery disease,21,22 heart rate reactivity,23 myocardial infarction,24 and respiratory sinus arrhythmia fluctuation.25 A considerable number of studies have shown that anxiety is an independent risk factor for cardiac mortality and coronary heart disease.26, 27, 28

Numerous guidelines within the CVD literature focus on the psychological aspects of care.29,30 A guideline dedicated to the care of patients with both CVD and mental health issues highlights the elevated prevalence of CVD risk factors among individuals with mental illnesses. This underscores the importance for mental health practitioners to systematically screen, monitor, and manage these risk factors on a regular basis. Such proactive measures in screening and monitoring cardiovascular risk factors are anticipated to contribute significantly to national targets and have a substantial impact on reducing cardiovascular morbidity and mortality among individuals with mental illness.29

Although the link between psychological factors and CVD is recognized, no method had been developed to utilize these factors for CVD prediction due to the absence of suitable data and analysis tools. This study seeks to bridge this gap by developing an ensemble machine learning (ML) model for CVD risk prediction. Initially, the model uses traditional risk factors such as body mass index (BMI), blood pressure, diabetes, and smoking status. Subsequently, it incorporates psychological data like depression, anxiety, and stress to enhance its accuracy. This iterative approach demonstrates the model's ability to handle data sets with varying complexity, showcasing the potential of integrating psychological factors into CVD risk assessment.

Methods

Study design

The UK Biobank is a large-scale biomedical database and research resource containing in-depth genetic and health information. It comprises a large, long-term (since 2006) data set from the United Kingdom, recruiting >500,000 participants from the general population; the design and participant population are described in.31 Data were collected through a combination of questionnaires, interviews, and blood, urine, and saliva samples and describes these physical measurements, together with lifestyle, medical history, and a series of health risk factors. The clinical characteristics of these diverse patient cohorts are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics (N = 375,145)

| Participants | 375,145 |

| Female | 200,012 (53.32%) |

| Male | 175,133 (46.68%) |

| Age, y | 56.43 ± 8.05 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27.39 ± 4.75 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 140.11 ± 19.57 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 82.82 ± 10.91 |

| Arrhythmia | 16,038 (4.28%) |

| Hypertensive diseases | 1,985 (0.53%) |

| Ischemic heart diseases | 25,820 (6.88%) |

| Heart failure | 5,642 (1.50%) |

| At least 1 CVD | 37,388 (9.97%) |

| Diabetes | 18,501 (4.93%) |

| Smoke history | 130,377 (34.75%) |

| Psychological factors | |

| Mood swings | 157,198 (41.90%) |

| Miserableness | 150,691 (40.17%) |

| Irritability | 101,104 (26.95%) |

| Sensitivity/hurt feelings | 175,103 (46.68%) |

| Fed-up feelings | 141,013 (37.59%) |

| Nervous feelings | 81,225 (21.65%) |

| Worrier/anxious feelings | 174,310 (46.46%) |

| Tense/highly strung | 62,152 (16.57%) |

| Suffering from nervousness | 75,106 (20.02%) |

| Loneliness | 63,919 (17.04%) |

| Guilty feelings | 102,917 (27.43%) |

| Risk taking behavior | 103,145 (27.49%) |

| Depressed | 83,352 (22.22%) |

| Lack of enthusiasm | 75,039 (20.00%) |

| Restlessness | 93,731 (24.99%) |

| Tiredness | 183,742 (48.98%) |

| Seen a doctor for mental health | 122,057 (32.54%) |

| Seen a psychiatrist for mental health | 41,013 (10.93%) |

Values are n (%) or mean ± SD.

CVD = cardiovascular disease.

We considered 2 categories as training data for our ML model. The first consisted of traditional CVD risk factors, such as gender, age, smoking status, BMI, HT, diabetes, systolic blood pressure (SBP), and diastolic blood pressure (DBP). The second category contained data from the UK Biobank touchscreen questionnaire on psychological factors and mental health. The UK Biobank Touch Screen Questionnaire is a vital component of the assessment center process. This comprehensive questionnaire covers diverse aspects, including consent, hearing tests, and cognitive function tests. The touch screen operation involves participants responding to inquiries related to various health domains, including mental health. Participants are guided through potentially sensitive questions, such as those pertaining to nerves, anxiety, tension, or depression, as well as their history of seeing a general practitioner or psychiatrist for mental health concerns.

The study utilized data from the UK Biobank touchscreen questions, focusing on various psychological factors. These factors include mood swings, miserableness, irritability, sensitivity/hurt feelings, fed-up feelings, nervous feelings, worrier/anxious feelings, tense/highly strung, worry duration after embarrassment, suffering from nerves, loneliness/isolation, guilty feelings, risk-taking, frequency of depressed mood, unenthusiasm/disinterest, tenseness/restlessness, tiredness/lethargy, and seeking medical help for mental health issues. The study explores participants' neuroticism scores derived from twelve related questions. The data set also includes information on depression status, neuroticism, episodes of depressive symptoms, and experiences of manic/hyper episodes, providing valuable insights into the relationship between psychological factors and mental health outcomes (full data details and UK Biobank codes in Supplemental Table 1).

CVDs considered in this study included a wide selection of diagnoses: atrial fibrillation and flutter, ventricular arrhythmias, atrioventricular and left bundle-branch block, angina pectoris, acute and subsequent myocardial infarctions and subsequent complications, chronic and acute ischemic heart diseases, hypertensive heart disease, and heart failure (Supplemental Table 2).

After preprocessing to remove entries with incomplete data, the data from 375,145 subjects were analyzed using a Pearson correlation. The median diagnosis age of included patients was 58.0 years (IQR: 37-73 years). We separated the data into training and test sets with 90% and 10% of subjects.

Modeling and predictive analyses

We developed an ensemble model containing 5 ML methods: decision tree, random forest, XGBoost, support vector machine, and deep neural networks (DNNs). Briefly, a decision tree algorithm32 employs a tree-like model of decisions and their possible consequences, including chance event outcomes, resource costs, and utility. Random forest33 is a learning method operating by constructing a multitude of decision trees at training time and XGBoost34 is a scalable end-to-end tree boosting system. A support vector machine35 is a supervised ML approach that maps training examples to points in space to maximize the width of the gap between the 2 clusters of points. A neural network recognizes hidden patterns in a data set by mimicking the human brain, and DNNs36 possess multiple layers to progressively extract higher-level patterns from raw input.

Our proposed ensemble-learning model collected results from each individual learning approach and produced a final output prediction by adopting a majority voting strategy; each model makes a prediction (votes) for each test instance and the final result is the one that receives more than half the votes. The process of UK Biobank data collection and our model overview are shown in the Central Illustration.

Central Illustration.

Model Overview

Our ensemble machine learning approach, including decision tree, random forest, XGBoost, SVM, and DNN models, was developed to predict CVD risk from psychological factors. DNN = deep neural networks; SVM = support vector machine; other abbreviation as in Figure 1.

Software and hardware

The analysis was conducted utilizing several libraries including Pandas,37 NumPy,38 Scipy,39 and Scikit-Learn.40 Plotting was performed using the Matplotlib41 and Seaborn42 libraries. All programming codes were written in Python programming language (3.9.x).43 The models were trained on the Phoenix High Performance Computing service provided by the University of Adelaide. The High Performance Computing had Intel X86-64 Haswell and Skylake CPUs with NVidia GPUs.

Results

Risk factor correlation

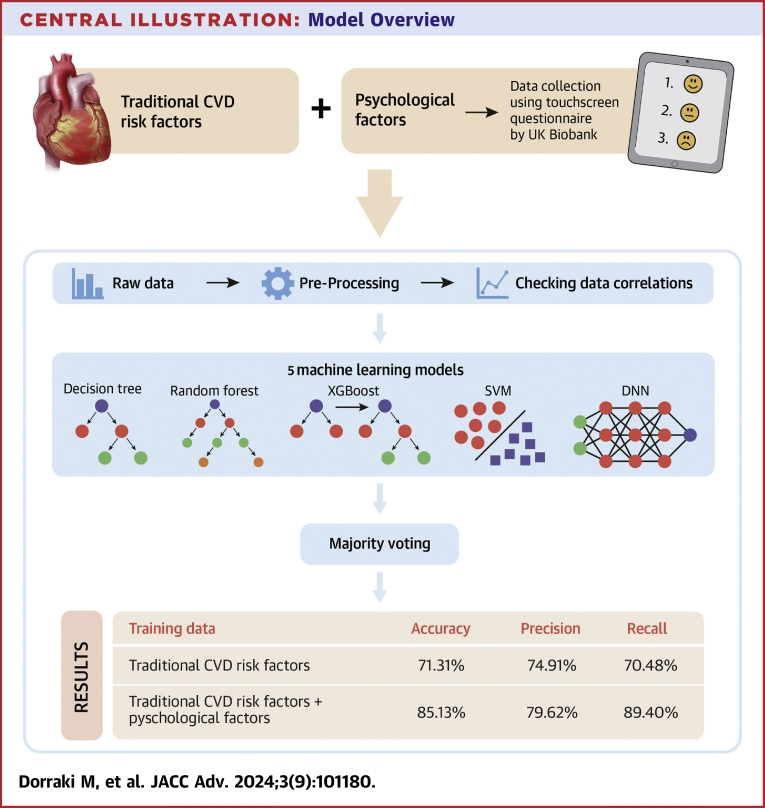

Our correlation analysis (Figure 1A) shows that almost all psychological factors are highly correlated, with the exception of risk taking (code: 2040). There is generally a negative correlation between age and psychological disorders, which may imply that psychological illnesses are not a natural part of ageing, and that psychological disorders predominantly affect younger adults.

Figure 1.

CVD Risks for Participants From the UK Biobank

(A) The correlation between CVD and a selection of psychological factors and traditional CVD risk factors. descriptions for psychological factor codes are provided in Supplemental Table 1. (B) The association of 4 traditional CVD risk factors by sex: age, BMI, SBP, and DBP. (C) The prevalence of CVD by sex and smoking status. BMI = body mass index; CVD = cardiovascular disease; DBP = diastolic blood pressure; SBP = systolic blood pressure.

Positive associations were observed between CVD and the traditional risk factors, especially for HT (Figure 1A). Figure 1B depicts the distribution of key physical factors (age, BMI, SBP, DBP) by gender. The incidence of CVD in females is lower than in males and CVD incidence increases for previous and current smokers (Figure 1C).

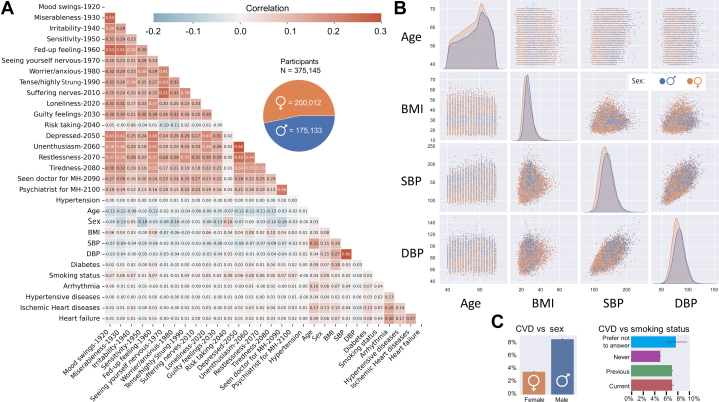

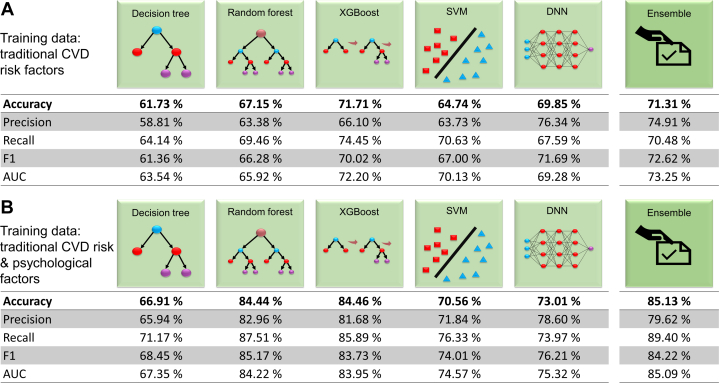

Ensemble ML for CVD prediction

We explored the ability of our model to predict CVD from 2 different groups of training data, namely traditional CVD risk factors only, and the combination of traditional and psychological factors. We separately trained the model on each data set, and then evaluated its accuracy with unseen test data.

Trained using traditional CVD risk factors only (sex, age, BMI, HT, SBP, DBP, diabetes, and smoking status), our ensemble model was able to predict CVD with an accuracy of 71.31% (precision 74.91%; recall 70.48%), which exceeded the performance of each individual ML model, particularly in precision (Figure 2A; metrics defined in Supplemental Table 3).

Figure 2.

Results From Different ML Models for 2 Training Data Categories

Accuracy, precision, recall, F1, and area under the curve (AUC) results from our ensemble model and 5 individual learning approaches are shown for training data comprising (A) traditional CVD risk factors only; and (B) the combination of traditional CVD risk and psychological factors. All metrics are described in Supplemental Table 3. ML = machine learning; other abbreviation as in Figure 1.

A second, independent training using combined traditional and psychological risk factors significantly increased CVD prediction accuracy of the ensemble model to 85.13% (precision 79.62%; and recall 89.40%) (Figure 2B). The accuracy and recall of our ensemble model outperformed any of the 5 constituent learning algorithms; intriguingly, the precision of the individual random forest and DNN algorithms were higher than for the ensemble model, suggesting the appropriate data classification of the ensemble model.

Thus, adding amassed psychological data to train our ensemble model increased the baseline 71.31% accuracy of CVD prediction by over 10%, to be 85.13% accurate. All other performance metrics also increased significantly after adding psychological factors to the training data, indicating their value in improving the identification of patients at-risk of CVD.

Bone disease prediction cross-check

To examine whether the predicted results were not generated spuriously, we performed a control experiment using the UK Biobank data set. Using our model trained on traditional and psychological CVD risk factors, we tested its accuracy in predicting bone diseases such as tuberculosis of bones and joints, disorders of bone density and structure, and osteopathies (see Supplemental Table 4). The ensemble model returned performance results similar to those of the 5 individual approaches; none were effective at predicting bone disorders using CVD risk factors (Supplemental Figure 1).

CVD prediction via logistic regression analysis

Logistic regression, a well-established statistical method, adds a layer of interpretability to the predictive model. Unlike the complex and often opaque nature of ensemble methods, logistic regression provides a clear understanding of the relationship between input features and the likelihood of CVD occurrence. By introducing logistic regression into the ensemble, the aim is to compare its performance with the existing ensemble approach. This comparative analysis not only contributes to the model's transparency but also provides insights into the strengths and weaknesses of each approach.

In order to enhance the predictive capabilities of CVD prediction, a logistic regression approach has been employed. The decision to incorporate logistic regression into our predictive modeling framework was driven by the need for interpretability and transparency in the prediction of CVD. Logistic regression, being a classical statistical method, offers a straightforward and intuitive understanding of the relationship between input features and the likelihood of CVD occurrence. We aimed to leverage the simplicity and interpretability of logistic regression to enhance the overall understanding of the predictive model. However, it is essential to note that despite its interpretative benefits, the results of the logistic regression (accuracy: 63.82%, precision: 62.61%, and recall: 65.43%) model did not surpass that of the ensemble model (accuracy: 85.13%, precision: 79.62%, and recall: 89.40%). The ensemble, with its combination of diverse ML algorithms, exhibited superior predictive performance, demonstrating the ability to capture complex patterns within the data. While logistic regression adds a layer of transparency, the hybrid model's primary strength lies in the amalgamation of predictive power from the ensemble.

Discussion

In this prospective study, we developed an ensemble ML approach that can accurately predict CVD risk from traditional risk factors alone. The accuracy of CVD prediction substantially improved to more than 85% by including mental health assessment data in the model, which explored participant symptoms and disorders such as depression, anxiety, and stress.

Prediction of CVD risk is a critical domain within CVD prevention. Several CVD risk prediction systems, such as SCORE,5 work with traditional risk factors, eg, age, gender, smoking, SBP, and total cholesterol. While these factors correlate well with CVD, their number is limited. Furthermore, some prediction systems have been developed on narrow data sets, eg, subjects with age of 40 to 65 years for SCORE and 40 to 69 years for SCORE2, limiting their validity to subjects outside that range.

Because of the relatively limited performance of state-of-the-art models, and variation on the individual level, new approaches are needed to guide primary prevention with features that do not rely solely on a limited number of clinical and lifestyle factors, and that can be applied to a broader range of individuals. Psychological studies have shown that mental health factors can be used for CVD prediction, which was demonstrated via correlation analysis and statistical prediction.44 In this study, we have used for the first time an ML approach that exploits these relationships to improve CVD prediction to impact management and early intervention.

ML approaches have the capability to interpret hidden patterns and structures within psychological and CVD data that cannot be detected by traditional statistical approaches. These approaches have the power to analyze very large quantities of data to generate data-driven recommendations, rather than hypothesis-driven answers. These intelligent methods do not discount the value of conventional diagnosis assessments to evaluate CVD risks; rather, they provide opportunities to predict or make diagnoses faster, more convenient, and more accurate by analyzing larger volumes of data than would be possible by humans.

Over the past few years, ML researchers have studied ensemble ML schemes that employ multiple approaches to provide more accurate performance than could be returned from any single constituent learning algorithm. In this study, we have developed an ensemble ML model to analyze UK Biobank data that improved the decision robustness and accuracy over any individual approach.

For the first time, we show that adding mental health factors to traditional CVD risk factors can improve the accuracy of ML prediction models. Our results may open new avenues for medical researchers and clinicians to predict CVD risk more precisely, more affordably, and apply early intervention strategies for at-risk individuals using a single time point mental health assessment. The principles demonstrated here can be readily applied to more complex ML models with more input data. Comprehensive Biobank data sets are necessary for training and validation, and these are becoming more available in health care settings through several sources such as hospitals. Our ensemble ML approach can be used to automate analysis and management of these big data sets to derive meaningful information to benefit clinical outcomes.

The findings of this study present promising opportunities for the prediction and prevention of CVD. By incorporating psychological factors into CVD risk models, we can enhance their accuracy and more effectively pinpoint individuals at higher risk. Leveraging AI techniques on mental health questionnaire data streamlines and improves the risk assessment process, rendering it both cost-effective and widely accessible, which could transform the field. This research highlights the importance of including mental health data in patient evaluations, suggesting that early intervention on psychological factors could markedly improve patient outcomes and cardiovascular health overall.

Study limitations

We have focused on the prediction of CVD using traditional and psychological factors regardless of CVD diagnosis timing. Although the date of first CVD diagnosis and the date of completing mental health questionnaires are available for individual patients, it is difficult to conclude with certainty whether the reported psychological disorders preceded or followed the development of CVD, especially as the mental health questionnaires only began in August 2016 (Supplemental Figure 2). Addressing this question is challenging as many patients reported with psychological disorders have unknowingly already developed CVD or vice versa. Investigations typically assume that the personality structure occurred before the appearance of heart disease,45 however, a longitudinal study of the personality of individuals prior to CVD would be required to address this question, opening future opportunities to investigate causal relationships.

Another limitation of our study is the lack of inclusion of medication data in the analysis. Certain medications used to treat psychiatric conditions may exacerbate or predispose CVD conditions. However, we did not have access to CVD and mental health medication data in the Biobank used for our study, which restricted our ability to investigate the potential impact of medications on CVD risk. Future research should consider incorporating medication data to provide a more comprehensive assessment of CVD risk factors.

In addition, the inclusion of mental health questions in our study was guided by the integration of all UK Biobank mental health questionnaire data. These data may not be fully captured by standardized psychological tests or confirmed psychiatric diagnoses. Therefore, it is crucial to interpret these self-reported measures cautiously, as they may be influenced by individual biases, cultural differences, or varying levels of insight into one's mental health.

Conclusions

We have developed a new CVD prediction ensemble ML model that improves CVD prediction outcomes relative to all 5 constituent algorithms when trained on traditional CVD risk factors. The accuracy remarkably increased to more than 85% when the model was trained using mental health data in addition to traditional CVD risk factor data. The findings imply that psychological assessment can become a reliable, easy to digitally acquire and affordable contribution to improving CVD prediction and management in primary and hospital care with the help of ML approaches.

Perspectives.

COMPETENCY IN MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE: Incorporating mental health assessment data within an ML model results in significantly improved, highly accurate prediction of CVD risk beyond traditional risk factors.

COMPETENCY IN SYSTEMS-BASED PRACTICE: ML approaches allow computers to analyze vast amounts of data and generate data-driven recommendations and decisions using population health data, helping interpretation of hidden patterns and structures in psychological factors and clinical outcome data.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK 1: This study's findings have promising implications for CVD prediction and prevention. Including psychological factors in CVD risk models can enhance accuracy and identify at-risk individuals effectively. Applying AI approaches on mental health questionnaire data makes risk assessment simple, cost-effective, and accessible, potentially transforming the field. Mental health is often overlooked in traditional CVD risk assessments, leaving gaps in understanding individual risk profiles. By objectively integrating mental health data into CVD risk models, this research stresses the importance of holistic patient assessment. Early addressing of psychological factors could lead to significant benefits, improving patient outcomes and overall cardiovascular health.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK 2: To overcome the barrier of translating innovations from computing labs to bedside care and enhance AI/ML adoption in health care, a 2-pronged approach is crucial. First, prioritizing randomized prospective studies and seamless integration and deployment in clinical workflows can bridge the gap between research and practical implementation. These studies will help establish causality between reported psychological disorders and CVD while revealing the temporal relationship between mental health characteristics and CVD diagnosis. By understanding this relationship, tailored prevention strategies can be developed, leading to improved patient care and outcomes. Embracing this approach has the potential to drive personalized and effective cardiovascular risk assessment and prevention strategies, ultimately contributing to a healthier and more resilient population.

Funding support and author disclosures

The authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

Appendix

For supplemental tables and a figure, please see the online version of this paper.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Task F.M., Piepoli M., Hoes A., et al. 2016 European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: the Sixth joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and other Societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts) developed with the special contribution of the European association for cardiovascular prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR) Atherosclerosis. 2016;252:207. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Casto G., Mastropieri M.A. The efficacy of early intervention programs: a meta-analysis. Except Child. 1986;52:417–424. doi: 10.1177/001440298605200503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ridker P.M., Buring J.E., Rifai N., Cook N.R. Development and validation of improved algorithms for the assessment of global cardiovascular risk in women: the Reynolds Risk Score. JAMA. 2007;297:611–619. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.6.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang T.J., Gona P., Larson M.G., et al. Multiple biomarkers for the prediction of first major cardiovascular events and death. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2631–2639. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conroy R.M., Pyörälä K., Fitzgerald A.P., et al. Estimation of ten-year risk of fatal cardiovascular disease in Europe: the SCORE project. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:987–1003. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(03)00114-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hippisley-Cox J., Coupland C., Vinogradova Y., Robson J., May M., Brindle P. Derivation and validation of QRISK, a new cardiovascular disease risk score for the United Kingdom: prospective open cohort study. BMJ. 2007;335:136. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39261.471806.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hippisley-Cox J., Coupland C., Vinogradova Y., Robson J., Brindle P. Performance of the QRISK cardiovascular risk prediction algorithm in an independent UK sample of patients from general practice: a validation study. Heart. 2008;94:34–39. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.134890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Altman D.G., Royston P. What do we mean by validating a prognostic model? Stat Med. 2000;19:453–473. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000229)19:4<453::aid-sim350>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goff D., Lloyd-Jones D., Bennett G. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American heart association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2014;63:S49–S73. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437741.48606.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whelton P.K., Carey R.M., Aronow W.S., et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:e127–e248. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson P.W., D’Agostino R.B., Levy D., Belanger A.M., Silbershatz H., Kannel W.B. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation. 1998;97:1837–1847. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.18.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rutledge T., Linke S.E., Krantz D.S., et al. Comorbid depression and anxiety symptoms as predictors of cardiovascular events: results from the NHLBI-sponsored Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) study. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:958. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181bd6062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piña I.L., Di Palo K.E., Ventura H.O. Psychopharmacology and cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:2346–2359. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.03.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang W., Babyak M., Krantz D.S., et al. Mental stress—induced myocardial ischemia and cardiac events. JAMA. 1996;275:1651–1656. doi: 10.1001/jama.275.21.1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bosma H., Peter R., Siegrist J., Marmot M. Two alternative job stress models and the risk of coronary heart disease. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:68–74. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheps D.S., McMahon R.P., Becker L., et al. Mental stress–induced ischemia and all-cause mortality in patients with coronary artery disease: results from the Psychophysiological Investigations of Myocardial Ischemia study. Circulation. 2002;105:1780–1784. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000014491.90666.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharkey S.W., Lesser J.R., Zenovich A.G., et al. Acute and reversible cardiomyopathy provoked by stress in women from the United States. Circulation. 2005;111:472–479. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000153801.51470.EB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lampert R., Jain D., Burg M.M., Batsford W.P., McPherson C.A. Destabilizing effects of mental stress on ventricular arrhythmias in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Circulation. 2000;101:158–164. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.2.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuper H., Marmot M., Hemingway H. Systematic review of prospective cohort studies of psychosocial factors in the etiology and prognosis of coronary heart disease. Semin Vasc Med. 2002;2:267–314. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-35401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salomon K., Clift A., Karlsdóttir M., Rottenberg J. Major depressive disorder is associated with attenuated cardiovascular reactivity and impaired recovery among those free of cardiovascular disease. Health Psychol. 2009;28:157. doi: 10.1037/a0013001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ford D.E., Mead L.A., Chang P.P., Cooper-Patrick L., Wang N.-Y., Klag M.J. Depression is a risk factor for coronary artery disease in men: the precursors study. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1422–1426. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.13.1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.York K.M., Hassan M., Li Q., Li H., Fillingim R.B., Sheps D.S. Coronary artery disease and depression: patients with more depressive symptoms have lower cardiovascular reactivity during laboratory-induced mental stress. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:521–528. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3180cc2601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knight B.G., McCallum T. Heart rate reactivity and depression in African-American and white dementia caregivers: reporting bias or positive coping? Aging Ment Health. 1998;2:212–221. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pratt L.A., Ford D.E., Crum R.M., Armenian H.K., Gallo J.J., Eaton W.W. Depression, psychotropic medication, and risk of myocardial infarction: prospective data from the Baltimore ECA follow-up. Circulation. 1996;94:3123–3129. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.12.3123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rottenberg J., Clift A., Bolden S., Salomon K. RSA fluctuation in major depressive disorder. Psychophysiology. 2007;44:450–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Compare A., Germani E., Proietti R., Janeway D. Clinical psychology and cardiovascular disease: an up-to-date clinical practice review for assessment and treatment of anxiety and depression. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2011;7:148. doi: 10.2174/1745017901107010148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janszky I., Ahnve S., Lundberg I., Hemmingsson T. Early-onset depression, anxiety, and risk of subsequent coronary heart disease: 37-year follow-up of 49,321 young Swedish men. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zafar M.U., Paz-Yepes M., Shimbo D., et al. Anxiety is a better predictor of platelet reactivity in coronary artery disease patients than depression. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1573–1582. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Michal M., Beutel M. Mental disorders and cardiovascular disease: what should we be looking out for? Heart. 2021;107:1756–1761. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2019-316379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gaffey A.E., Harris K.M., Mena-Hurtado C., Sinha R., Jacoby D.L., Smolderen K.G. The Yale Roadmap for health psychology and integrated cardiovascular care. Health Psychol. 2022;41:779–791. doi: 10.1037/hea0001152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sudlow C., Gallacher J., Allen N., et al. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 2015;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Safavian S.R., Landgrebe D. Vol. 21. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics; 1991. A Survey of Decision Tree Classifier Methodology; pp. 660–674. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ho T.K. Proceedings of 3rd international conference on document analysis and recognition. IEEE; 1995. Random decision forests; pp. 278–282. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen T., He T., Benesty M., Khotilovich V., Tang Y., Cho H. Xgboost: extreme gradient boosting. R Package Version 04-2. 2015;1:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cortes C., Vapnik V. Support-vector networks. Mach Learn. 1995;20:273–297. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmidhuber J. Deep learning in neural networks: an overview. Neural Network. 2015;61:85–117. doi: 10.1016/j.neunet.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McKinney W. pandas: a foundational Python library for data analysis and statistics. Python Perform Sci Comput. 2011;14:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harris C.R., Millman K.J., Van Der Walt S.J., et al. Array programming with NumPy. Nature. 2020;585:357–362. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2649-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Virtanen P., Gommers R., Oliphant T.E., et al. SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat Methods. 2020;17:261–272. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0686-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pedregosa F., Varoquaux G., Gramfort A., et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in Python. J Mach Learn Res. 2011;12:2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hunter J.D. Matplotlib: a 2D graphics environment. Comput Sci Eng. 2007;9:90–95. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waskom M, Gelbart M, Botvinnik O, et al. mwaskom/seaborn: v0. 12.0 a1. Zenodo. 2022. 10.5281/zenodo.6609266. [DOI]

- 43.Van Rossum G. USENIX annual technical conference; 2007. Python Programming Language; pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cunningham R., Poppe K., Peterson D., Every-Palmer S., Soosay I., Jackson R. Prediction of cardiovascular disease risk among people with severe mental illness: a cohort study. PLoS One. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fisher S.H. Psychological factors and heart disease. Circulation. 1963;27:113–117. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.27.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.