Abstract

Background

Working long consecutive hours’ is common for anaesthesia and critical care physicians. It is associated with impaired medical reasoning’s performance of anaesthesiology and serious medical errors. However, no study has yet investigated the impact of working long consecutive hours’ on medical reasoning.

Objective

The present study evaluated the impact of working long consecutive hours’ on the medical reasoning’s performance of anaesthesiology and intensive care physicians (residents and seniors).

Methods

This multicentric, prospective, cross-over study was conducted in 5 public hospitals of Normandy region. Two groups of anaesthesia and critical care physicians were formed. One was in a rest group, RG (after a 48-hours weekend without hospital work) and the other in Sleep Deprivation Group (SDG) after a 24 h-consecutives-shift. Changes in medical reasoning’s performance were measured by 69-items script concordance tests (SCT) through to the two tests. Group A completed the first part of the assessment (Set A) after a weekend without work and the second part (Set B) after a 24 h-shift; group B did the same in reverse order. The primary outcome was medical reasoning’s performance as measured by SCT in RG and SDG. The secondary outcomes included association between the performance with the demographic data, variation of the KSS (Karolinska sleepiness scale) daytime alertness score, the number of 24 h-shift during the previous 30 days, the vacations during the previous 30 days, the presence of more or less than 4 h consecutives hours slept, the management of a stressful event during the shift, the different resident years, the place where the shift took place (University hospital or general hospitals) and the type of shift (anaesthesia or intensive care).

Results

84 physicians (26 physicians and 58 residents) were included. RG exhibited significantly higher performance scores than SDG (68 ± 8 vs. 65 ± 9, respectively; p = 0.008). We found a negative correlation between the number of 24 h-shifts performed during the previous month and the variation of medical reasoning’s performance and no significant variation between professionals who slept 4 h or less and those who slept more than 4 h consecutively during the shift (-4 ± 11 vs. -2 ± 11; p = 0.42).

Conclusion

Our study suggests that medical reasoning’ performance of anaesthesiologists, measured by the SCT, is reduced after 24 h-shift than after rest period. Working long consecutive hours’ and many shifts should be avoided to prevent the occurrence of medical errors.

Keywords: Medical reasoning’s performance, Shifts, Script concordance test

Introduction

Extended shift durations and interrupted sleep are integral parts of anaesthesiologists’ professional lives. Anaesthesiology requires complementary technical and non-technical skills, including communication, decision making and stress management, which are essential in daily practice and especially in crisis management. However, sleep deprivation is one factor potentially leading to impaired performance and practice [1].

Few studies regarding technical skills exist and have shown contradictory results in our specialty. No impact of sleep deprivation on technical tasks (e.g. epidural catheter placement) has been observed among anaesthesiology residents [2] but the risk of a blood exposure accident appears greatly increased after a 24-hours shift [3]. Sleep deprivation is associated with impaired medical performance of anaesthesiology residents in managing simulated crisis situations : more pharmacological errors (dosing and administration errors), delays in identifying hypotension, and lack of adequate communication [4]. Other studies showed an alteration of the residents’ cognitive abilities after sleep deprivation [5, 6]. Moreover, after a nightshift, vigilance disorders with increased sleepiness as well as mood disorders were observed in anaesthesiology residents [7]. Landigran et al. showed that residents working 24-hours shifts or more in an intensive care unit made 36% more serious medical errors than those working shorter shift [8]. In a self-reporting survey, 86% of New Zealand anaesthetists declared that they did errors in patient care attributed to fatigue [9]. Finally, other specialties, such as surgery, find similar results. A large retrospective study suggested that sleep deprivation led to an increased complication rate during surgical procedures [10]. This was also reported during laparoscopic surgery simulation, showing that sleep deprivation increased operating time and error rates during complex surgical tasks [11].

It is well thus established that nightshift fatigue has a professional impact on practitioners’ abilities. However, no study has yet investigated the impact of nightshifts on anaesthesiologists’ medical reasoning’s performance. The primary end point of this study was to assess the medical reasoning’s performance assessed by SCT before and after a 24hours-shift. The performance in SCT was expresses as degree of concordance with the panel of 20 experts (expressed out of 100 points). We hypothesize that sleep deprivation could affect the medical reasoning’ performance of anaesthesiologists.

Methods

Study procedures

This prospective, cross-over study was conducted among anaesthesiology residents and physicians. The working hours were based on the shift schedules of critical care and all anesthesia specialties, including obstetrical anesthesia. After inclusion, residents and physicians were included in two groups, depending of SCT set (A or B), allowing for a 1:1 cross-over randomization (groups A and B), stratified by different curriculum‘s years of resident or physician senior. As a cross-over design, each group answered by email each to the two tests, in 2 situations. The rest group (RG) was defined by 48-hours weekend without hospital work. The Sleep Deprivation Group (SDG) was defined by a time of 24 h-consecutives-shift that had to be on a Monday, Tuesday or Wednesday, so as not to add to the fatigue accumulated by the work week to the evaluation. To avoid the bias of one test session being easier than the other, group A completed the first part of the assessment (Set A) after a weekend without work and the second part (Set B) after a 24 h-shift; group B did the same in reverse order. Participants completed each test in the morning before engaging in any other hospital activities. For our primary outcome, we measured the medical reasoning’s performance using TCS. Our secondary outcomes were measured using the Karolinska Sleepiness Scale (KSS) daytime alertness score to evaluate the daytime vigilance of the practicians at the time of the test [12].

Population selection

We included anaesthesiology’s residents and physicians practicing in department of anaesthesiology and critical care in 5 public hospitals of Normandy region (Rouen, Le Havre, Dieppe, Elbeuf, and Evreux) during the collection period. The exclusion criteria were refusal to participate or the presence of any element leading to a sleep disorder defined in this work by continuous sleep of less than 6 h per night.

Design of the script concordance test

The SCT is a tool used to evaluate medical reasoning’s performance in conditions of uncertainty [13]. The SCT format allows for incorporating the uncertainty that characterizes medical practice, and it is considered that the required cognitive tasks are closer to the reality of medical reasoning than in other kind of tests [14, 15]. This methodology has been already use for anaesthesiology residents [16–19]. As previously described, SCTs confronted the responders with authentic uncertain clinical situations concerning anaesthesiology and intensive care which were described in vignettes [16]. The TCS (Sets A and B) are taken from a local bank which has been used for several other published works [16–19], written and reviewed by MR, TC and VC. The clinical situations (haemorrhagic and septic shock, obstetric field, usual emergency anaesthesia and critical care) were problematic even for experienced clinicians, either because there were not enough data, or the situations were ambiguous. There were several options for diagnosis, investigation, or treatment. The items (questions) were based on a panel of questions that an experienced clinician would consider relevant to this type of clinical setting. The item was consistent with the presentation of relevant options and new data (not described in the vignette). The task for the responder was to determine the effect these new data on the status of the option. The respondent’s task was to assess, using a 5-points Likert scale, the influence of this new element on the diagnostic hypothesis, the plan for investigation, or the treatment. The different points on the scale corresponded to positive values (the option was enhanced by the new data), neutral values (the data did not change the status of the option), or negative values (this option was ruled out by the data). The scoring system was based on the principle that any answer given by one expert had an intrinsic value, even if that answer did not coincide with those of other experts. A group of 20 experienced anaesthesiologists and intensive care physicians formed the expert panel and SCTs were designed as previously described [16, 17, 19]. The principles of SCT are that for each item, the answer entitled the responder to a credit corresponding to the number of experts who had chosen it. All items had the same maximum credit, and raw scores were transformed proportionally to obtain a one-point credit for the answer that was chosen by most experts. Other choices received a partial credit. Thus, to calculate the scores, all results were divided by the number of individuals who had given answers chosen by the largest number of respondents. The total score for the test was the sum of all credits earned for each item. The total score was then transformed into a percentage score. An automatic correction software of the University of Montreal (freely accessible on the website of the University of Montreal: https://cpass.umontreal.ca/recherche/axes-de-recherches/concordance/tcs/presentation_tcs/) was used for scoring.

SCTs optimization

For evaluation, SCTs including 31 scenarios for a total of 93 items were submitted to a panel of 20 experts. According to the recommendations of Lubarsky et al., we optimized SCT by performing a post-hoc analysis [13]. Items with high variability, low variability, or binomial responses were excluded. We obtained a final version with 28 scenarios and 69 items. The final assessment consisted of 69 SCTs divided in Set A and Set B (38 SCTs and 31 SCTs), with the different clinical situations being balanced in the two groups, and Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (index of consistency and reliability) was 0.64. The test is considered to be adequate when Cronbach’s alpha coefficient reaches a value of 0.64 20.

Study outcome

The primary end point was the medical reasoning’s performance assessed by SCT before (RG) and after a 24 h-shift (SRG). The performance in SCT was expresses as degree of concordance with the panel of 20 experts (expressed out of 100 points).

We researched too if the performance of medical reasoning’s performance before (RG) and after a 24 h-shift (SRG) is associated with the demographic data, variation of the KSS (Karolinska sleepiness scale) daytime alertness score, the number of 24 h-shift during the previous 30 days, the vacations during the previous 30 days, the presence of more or less than 4 h consecutives hours slept, without considering the hours of non-consecutive sleep that occurred before or after these hours, the management of a stressful event during the shift (suggested as examples: cardiac-arrest, death during emergency care, initial management of polytrauma, intubation of acute respiratory distress, code red for cesarean), the different resident years, the place where the shift took place (University hospital or general hospitals), the type of shift (anaesthesia or intensive care).

Ethical considerations

In accordance with French laws, the Ethics and Evaluation Committee for Non-Interventional Research approved this study (N°E2020-92). All participants received information before any study procedures were undertaken, and practicians were invited to participate as subjects in the study. All participants gave informed consent (by e-mail or telephone) and were informed that they could stop participating at any time, the tests were anonymous.

Statistical analysis

With regard to previous publications [17, 19], we assumed that a difference of 6% for SCT test between the two groups would be pedagogical significant (a difference at least of 3% between two groups would be significant for the SCT). Based on these findings, assuming that the SD were similar, and using a power of 0.90 with a level of statistical significance at 0.05, it was estimated that at least 38 anaesthesiologists should be analyzed before (RG) and after a 24 h-shift (SRG) (i.e. a total of 38 anaesthesiologists, because of the crossover design). Considering the likelihood of dropouts, we enrolled 90 anaesthesiologists.

The values are presented as number and percentage values for qualitative variables, as mean and SDs for quantitative variables with a normal distribution, and as median and interquartile range for quantitative variables with a non-normal distribution. Residents and physicians who did not respond to the two sets of tests were excluded from the final analysis. After performing a Shapiro-Wilk normality test, the quantitative variables were compared using a Wilcoxon test or a student t-test. For the primary outcome, the TCS performance before (RG) and after a 24 h-shift (SRG) was compared with student t-test. For the secondary outcomes, a multivariable analysis using a linear regression model, including demographic characteristics and variables, described in previous paragraph, presenting a p-value < 0.2 in the univariable analysis, was realized to identify the factors associated with the variation of medical reasoning’s performance before (RG) and after a 24 h-shift (SRG). The Pearson correlation test was used to assess the strength of the association between two quantitative variables. A Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, including area under the ROC curve (AUC), was used to determine a number of shifts/month threshold able to discriminate professionals with and without clinically significant alteration of medical reasoning’s performance (defined as a SCT score reduction of at least 6%) before (RG) and after a 24 h-shift (SRG). The significance threshold was set at 0.05. All statistics were analyzed using GraphPad PRISM software 9.1.2.

Results

Population characteristics

Ninety anaesthesiology residents and physicians from five hospitals agreed to participate and were included, from March to July 2021. Then they were included in two groups (45 in each group. Five anaesthesiologists in Group A and one in Group B were excluded from analysis (no or incomplete response)). Finally, 40 participants in Group A and 44 in Group B were analyzed. Their characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the population analyzed

| Characteristic | Population (n = 84) | Group A (n = 40) |

Group B (n = 44) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 30 ± 5 | 30 ± 6 | 30 ± 5 |

| Sex | |||

|

Male Female |

45 (53%) 39 (47%) |

21 (53%) 19 (47%) |

24 (54%) 20 (46%) |

| Status | |||

|

Resident Physician |

58 (69%) 26 (31%) |

29 (72%) 11 (23%) |

29 (66%) 15 (44%) |

| Resident’s year | |||

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

8 (9%) 13 (15%) 16 (19%) 14 (17%) 7 (8%) |

4 (13.8%) 7 (24.1%) 8 (27.6%) 7 (24.1%) 3 (10.3%) |

4 (13.8%) 6 (20.6%) 7 (24.1%) 7 (24.1%) 4 (13.8%) |

| Number of 24 h-shifts in the previous month | 5 [4 ; 6] | 5 [4 ; 6] | 5 [4 ; 6] |

| KSS score | |||

|

before a 24 h-shift (RG) after a 24 h-shift (SRG) |

3 [3 ; 4] 6 [6 ; 7] |

3 [3 ; 4] 7 [6 ; 7] |

3 [3 ; 4] 6 [6 ; 7] |

| Number of hours consecutively slept during 24 h-shift | |||

|

< 4 h > 4 h |

49 (59%) 35 (41%) |

25 (62%) 15 (38%) |

24 (55%) 20 (45%) |

| Vacations during the previous month | |||

|

Yes No |

28 (34%) 56 (66%) |

17 (42%) 23 (58%) |

11 (25%) 33 (75%) |

Values are presented as number and percentage (n, %) for qualitative variables, and as mean ± SD or median [interquartile range] for quantitative variables. Groupe A and B depending of SCT set (A or B). Group A completed the first part of the assessment (Set A) after a weekend without work (rest group, RG) and the second part (Set B) after a 24 h-shift (The Sleep Deprivation Group, SRG); group B did the same in reverse order

Concerning the residents, they performed on average 5 shifts per month, including 1 on weekends for most of them. 50% them did their shift in critical care and the other 50% in anaesthesia. Concerning the physicians, 88% of the population was composed of seniors working at the Rouen University Hospital, 73% of them had less than 5 years of experience, and they worked an average of 5 shifts per month, including 1 on weekends for most of them. 38% of them did their shift in intensive care and the 62% other in anaesthesia.

Impact of a 24 h-shift on medical reasoning’s performance

RG exhibited significantly higher performance scores than SDG (68 ± 8 vs. 65 ± 9, respectively; p = 0.008). We found no significant variation in medical reasoning’s performance (expressed as variation in SCTs performance between the RG and SDG) between residents and physicians (-4 ± 11 vs. -2 ± 10, respectively; p = 0.40). Overall, There is a difference in SCT score between 2 groups for year 1 and 2 residents (Table 2).

Table 2.

Residents and physicians’ SCT performance

| SCT performance before vs. after | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| Years 1–2 (n = 21) | 65 vs. 60 [0.2 ; 9.6%] | 0.04 |

| Years 3–4 (n = 30) | 66 vs. 62 [− 0.8 ; 9.6%] | 0.1 |

| Year 5 (n = 7) | 71 vs. 70 [− 8.5 ; 10.2%] | 0.8 |

| Physicians (n = 26) | 71 vs. 69 [− 5.9 ; 2.0% ] | 0.3 |

Values are presented as mean; IC 95%

Impact of the previous month’s activities on medical reasoning’s performance

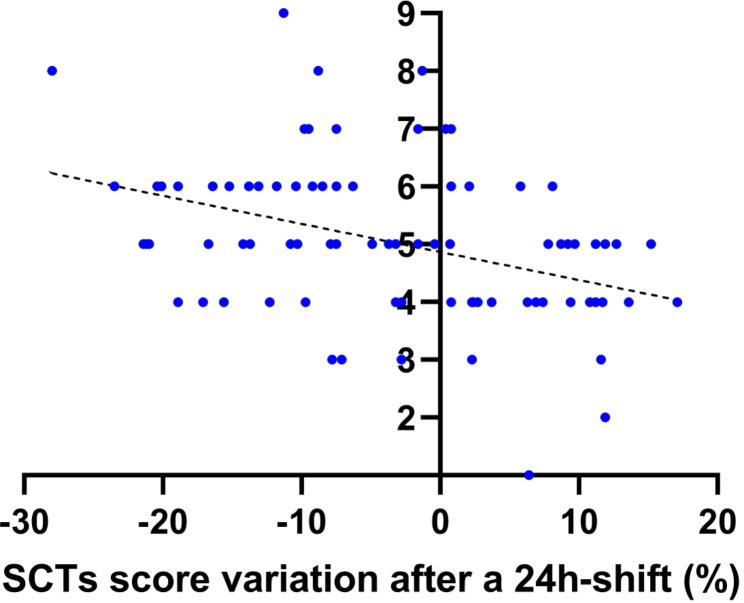

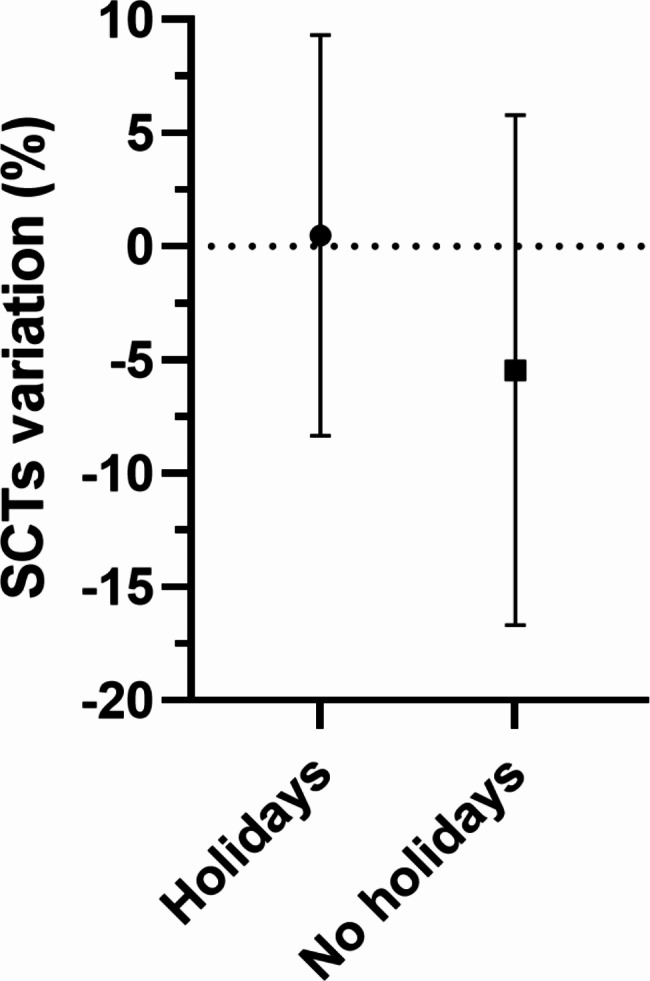

We found a negative correlation between the number of 24 h-shifts performed during the previous month and the variation of medical reasoning’s performance before (RG) and after a 24 h-shift (SRG) (Fig. 1). Professionals who had at least one week of vacations in the month preceding the 24 h-shift didn’t decrease the medical reasoning’s performance before (RG) and after a 24 h-shift (SRG) unlike those who had no vacations (0.4 ± 8 vs. -5 ± 11, respectively; p = 0.02). In multivariable analysis, the number of 24 h-shifts performed during the previous month was the only factor associated with a decrease of medical reasoning’s performance before (RG) and after a 24 h-shift (SRG) (Table 3).

Fig. 1.

Correlation between medical reasoning variation (script concordance tests (SCTs) scores variation between a rest period vs. after a 24 h-shift) and the number of 24 h-shifts during the month preceding the evaluation. Result is presented as Pearson correlation coefficient with 95% confidence interval

Table 3.

Multiple linear regression model to predict the variation of medical reasoning after a 24 h-shift

| Variable | Variation of medical reasoning (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | 95% Confidence Interval | p | |

| Sex (female) | -2.03 | -6.49; 2.42 | 0.37 |

| Age (years) | -0.20 | -0.74; 0.35 | 0.47 |

| Status (physician) | 4.03 | -2.27; 10.33 | 0.21 |

| Holidays during the previous month (yes) | 4.06 | -0.71; 8.83 | 0.09 |

| Number of 24 h-shift during the previous month | -2.92 | -4.5; -1.26 | 0.0008 |

Values are presented as mean; IC 95%

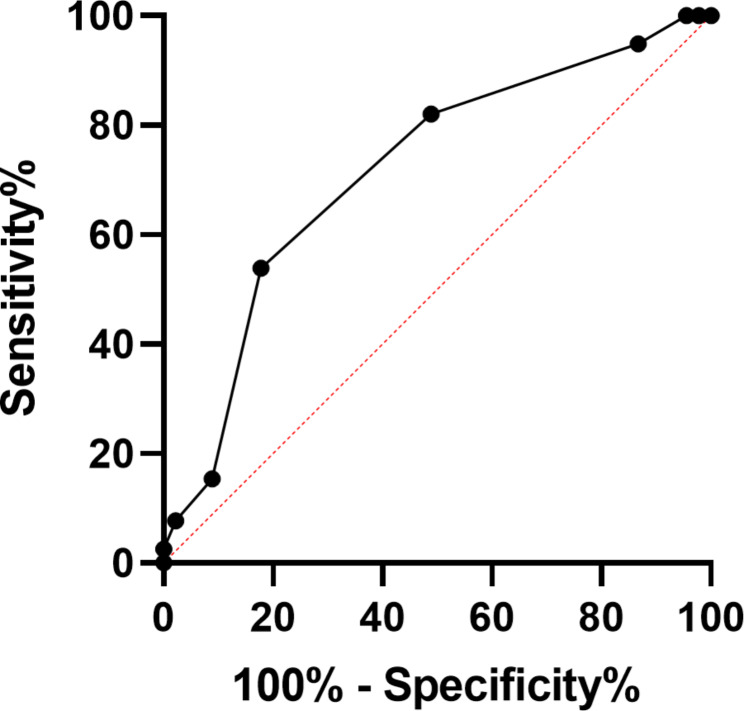

Concerning the number of 24 h-shifts performed during the previous month, the AUC for discriminating professionals with clinically significant alteration of medical reasoning’s performance after a 24 h-shift (reduction of SCTs score ≥ 6%) to professionals without medical reasoning’s performance alteration before (RG) and after a 24 h-shift (SRG) was 0.72 [0.61–0.83] (p = 0.0007; Fig. 2). With a number of shifts ≥ 5/month, the sensitivity was 82.1 [67.3–91.0]% and the specificity was 51.1 [37.0–65.0]% (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Receiver operator characteristic curve generated with the number of 24 h-shifts performed during the previous month in professionals with clinically significant alteration of medical reasoning after a 24 h-shift and those without. The receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve is the plot of the true positive rate (sensitivity) vs. the false positive rate (100 − specificity) for different positivity thresholds (different cutoff levels of shifts/month). The calculated value of the area under the ROC curve (AUC) was 0.72 (superior to the random value of 0.5), indicating that the number of 24 h-shifts performed during the previous month discriminated professionals with and without alteration of medical reasoning after a 24 h-shif

Fig. 3.

Medical reasoning variation (script concordance tests (SCTs) scores variation between a rest period vs. after a 24 h-shift) among professionals having holidays (at least one week) in the preceding month vs. those who had no holidays. Data are presented as mean ± SD. *, p < 0.05

Impact of shift associated factors with medical reasoning’s performance variation

We found no significant medical reasoning’s performance variation before (RG) and after a 24 h-shift (SRG) between professionals who slept 4 h or less and those who slept more than 4 h consecutively during the shift (-4 ± 11 vs. -2 ± 11; p = 0.42). There was no difference of medical reasoning’s performance variation before (RG) and after a 24 h-shift (SRG) between professionals who experienced a stressful event during the shift and those who did not (-5 ± 10 vs. -3 ± 11; p = 0.30). There was no correlation between evolution of fatigue level (measured by the variation of KSS before and after the 24 h-shift) and medical reasoning’s performance variation before (RG) and after a 24 h-shift (SRG) (r=-0.02 [-0,23;0,20]; p = 0.86).

Discussion

Medical reasoning’s performance of anaesthesiologist, measured by the SCT, was reduced after 24 h-shift than after rest period. This performance is also affected negatively by the number of shifts in the month preceding the assessment or positively by previous holidays. The 24 h-shift affected year 1 to 2 residents more than other residents or physicians. The fatigue or sleeping more or less than 4 consecutive hours during the 24-shift have no impact on the performance of medical reasoning.

To our knowledge, we report for the first time that a 24 h-shift is associated with a decrease of medical reasoning’s performance evaluated by SCTs among anaesthesiologists. Arzalier-Daret et al. used a 2 validated simulated scenario in residents in anaesthesia, showing that sleep deprivation after a night shift significantly decreased global performance in managing simulated events [4]. In addition, sleep deprivation increased the time required to identify and correct events, as well as pharmacological errors. For Neuschwander et al., sleep deprivation after a nightshift was associated with impaired non-technical skills of anaesthesia residents in a simulated anaesthesia intraoperative crisis scenario [7]. This reduced mobilization of nontechnical skills was associated with impaired team working, increased sleepiness, and decreased confidence in anaesthesia skills. Interestingly, the medical reasoning’s performance is more affected by sleep deprivation in young residents (Years 1 and 2). This result could be explained by Kahneman theory. Although Daniel Kahneman is not a physician, he is a Nobel Prize Economist for his work on decision-making under uncertainty, which has important implications for medicine [20]. Kahneman’s key concept is the distinction between two modes of thinking: system 1, which is fast, intuitive and automatic, and system 2, which is slow, analytical and conscious. In the medical context, system 1 can lead to cognitive biases and diagnostic errors, while system 2 can help to correct these biases and make more informed decisions [21]. Probably that the youngest residents base their decisions much more on system 2 than the other, and that this analytic approach is more affected by sleep deprivation. To improve clinical decision-making, it may be necessary to use systematic thinking strategies, based for example on cognitive aids, even more so during critical periods such as those of sleep deprivation and for the youngest doctors.

Surprising the performance of medical reasoning is decreased by 24 h-shift but independently of the number of consecutive hours of sleep or fatigue experienced, in contrast to the works done in the simulation framework. Sleep deprivation was defined as the lack of at least a four-hours period of consecutive sleep during the previous 24 h. This specific definition of sleep deprivation has not been fully tested in physician-subjects, but four hours of uninterrupted sleep seems to be the minimum requirement for a beneficial effect on cognitive performance in studies of non-physicians [22, 23]. Based on the physiology of sleep, four-hours period of consecutive sleep corresponds both to half of a normal night’s sleep and as the addition of the two sleep cycles that normally allow each person to access deep sleep, considered to be restorative sleep. In the literature, there is no consensus regarding this definition in sleep studies, but was often used as evidenced by these meta-analysis [24, 25].

Shift results in acute sleep deprivation, not infrequently approaching 24 h without sleep. Two comprehensive qualitative reviews of the effect of sleep loss in resident physicians, both reported a decline in performance after 24 h without sleep, but more precisely, studies have shown that alertness is higher, and errors are lower if continuous wakefulness is limited to 16 h [26, 27]. Persico et al. tested four cognitive abilities, they were significantly altered after a 24-hours shift, whereas they were not significantly different from the rested condition after a 14-hour nightshift [28]. These studies suggest that performance is not related to sleep time during shift, as we have shown, but that there may be a threshold at which performance appears to be impaired.

Certainly, the organization of medical work is an important factor that can impact the quality of patient care and the well-being of healthcare providers. The French guidelines on human factors in critical situations provide recommendations for optimizing the organization of medical work in critical situations [29]. These guidelines suggest that healthcare organizations should consider factors such as staffing levels, workload, communication, and teamwork when designing work schedules and organizing care. Several studies have examined the impact of working hours on patient care and healthcare provider outcomes. A study published in 2023 found that acute care surgeons preferred shorter shift lengths and that longer shifts were associated with increased fatigue and decreased performance [30]. Similarly, a systematic review found that longer shift lengths were associated with an increased risk of errors and adverse events, as well as negative effects on healthcare providers’ health and well-being [31]. Another systematic review found that shift length, protected sleep time, and night float were all associated with patient care, resident health, and education outcomes [32]. These findings suggest that optimizing the organization of medical work, including work schedules and staffing levels, is critical for ensuring high-quality patient care and promoting the well-being of healthcare providers. Healthcare organizations should consider evidence-based guidelines and best practices when designing work schedules and organizing care, and should regularly evaluate the impact of these practices on patient outcomes and provider well-being.

Our study suggests that the alteration of medical reasoning’s performance is not only related to the difficulty of the shift itself but seems to be more related to the accumulation of them. The number of shifts performed in a month appears to significantly alter the medical reasoning’s performance. There was indeed a linear correlation between the number of shift and the alteration of medical reasoning’s performance in our study. There appears to be a threshold beyond which the number of shifts appears to impair medical reasoning’s performance, estimated at 4 shifts a month. Moreover, practicians who had at least a week of vacations in the previous month had a medical reasoning’s performance that remained stable, unlike those who did not. Taken together, these results suggest that the impairment of medical reasoning may be related to chronic fatigue, rather than acute fatigue generated by a shift sleep deprivation. Good quality studies have shown that a reduction in the time worked by residents reduce errors in the ICU. However, these studies focused on the number of hours per week and not on the number of shifts per month, and were carried out in the USA, where the number of hours worked by residents are much more to than in France [8, 27]. The absence of impairment of medical reasoning’s performance in our study in physicians is probably associated with the decrease in working time in the month before the test.

Our study has several limitations. First, the Cronbach coefficient alpha in our SCT evaluation was slightly low. The limited number of SCT after optimization probably explains this low coefficient. This coefficient value remains adequate according to the guidelines concerning the SCT, supporting the validity of our study [33]. Second, our SCTs were sent by e-mail to the participants, in contrast to the Ducos et al. where the subjects answered the SCT during a one-hour test (one minute per item) and under supervision [34]. Thirdly, our population is small and from one region, which had received the same educating programs, composed of volunteers which exposes to a selection bias. Our population included only French anaesthesiologists, considering the difference of organization and rhythm of work between countries, it would be uncertain to generalize our results to other countries or other specialties. The residents and seniors included were all from the same region. Therefore, the residents had received the same education. Learning objectives for anaesthesiology residents are French National Guidelines for anaesthesia teaching, given to all participating residents at the beginning of their 5-year anaesthesiology program. The training program for all residents includes several types of learning with 10 days dedicated to specific topic lectures throughout the academic year. In addition, a weekly journal club and a weekly practice exchange group are organized. The university department has supervised other works related to SCT’s, which allowed all the residents and physicians to be already familiar with this assessment. Furthermore, although the participants share a common educational background, this does not imply uniformity in medical reasoning, as assessed by the SCTs. Medical reasoning is influenced not just by education, but also by individual clinical experiences and expertise levels. Fourth, we examined the impact of fatigue on professionals’ daytime vigilance using only the KSS score (this test was closely related to EEG and behavioral variables, indicating a high validity in measuring sleepiness), a more comprehensive and global approach to the participants’ fatigue would have been relevant to know the percentage of chronically fatigued individuals in our population, to try to highlight a correlation between medical reasoning’s performance variation and chronic fatigue felt by the professionals. We also considered an objective assessment of sleep quality via wrist actimetry allowing a continuous and prolonged assessment of sleep : duration, sleep efficiency (sleep time compared to theoretical sleep time in percentage), sleep fragmentation index [35].

In conclusion, this study suggests that a sleep deprivation after 24 h-shift decreases the medical reasoning’s performance of anaesthesiologists, and that this impairment is proportional to the number of shifts performed during the previous month. This observation reinforces the fact that the frequency of 24 h-shifts should be limited to prevent the occurrence of medical errors.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Glossary of terms

- ISNIH

Inter Syndical National Union of Hospital Interns.

- ANTS

non-technical skills for a population of anaesthesiologists.

- ICU

intensive care unit.

- MCQ

multiple-choice questionary.

- RG

Rest group.

- SCT

script concordance test.

- SDG

Sleep Deprivation Group.

- KSS

Karolinska sleepiness scale.

Author contributions

M.R.: study design, data collection, data analysis, and writing the first draft of the paper; T.C.: Study design, data analysis, student recruitment and data collection; E.A.: SCT and data collection; M.L.: SCT and data collection; B.D.: SCT and data collection. V.C.: study design, data collection, data analysis, and writing the first draft of the paper.

Funding

Support was provided solely from institutional and/or departmental sources.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

In accordance with French laws, the Ethics and Evaluation Committee for Non-Interventional Research approved this study (N°E2020-92). All participants received information before any study procedures were undertaken, and practicians were invited to participate as subjects in the study. All participants gave informed consent (by e-mail or telephone) and were informed that they could stop participating at any time, the tests were anonymous.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gaba DM, Howard SK. Fatigue among clinicians and the safety of patients. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1249–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cao CGL, Weinger MB, Slagle J, Zhou C, Ou J, Gillin S, Sheh B, Mazzei W. Differences in Day and Night Shift Clinical performance in Anesthesiology. Hum Factors. 2008;50:276–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ayas NT, Barger LK, Cade BE, Hashimoto DM, Rosner B, Cronin JW, Speizer FE, Czeisler CA. Extended work duration and the risk of self-reported percutaneous injuries in interns. JAMA. 2006;296:1055–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arzalier-Daret S, Buléon C, Bocca M-L, Denise P, Gérard J-L, Hanouz J-L. Effect of sleep deprivation after a night shift duty on simulated crisis management by residents in anaesthesia. A randomised crossover study. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2017. 10.1016/j.accpm.2017.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maltese F, Adda M, Bablon A, Hraeich S, Guervilly C, Lehingue S, Wiramus S, Leone M, Martin C, Vialet R, Thirion X, Roch A, Forel J-M, Papazian L. Night shift decreases cognitive performance of ICU physicians. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42:393–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neuschwander A, Job A, Younes A, Mignon A, Delgoulet C, Cabon P, Mantz J, Tesniere A. Impact of sleep deprivation on anaesthesia residents’ non-technical skills: a pilot simulation-based prospective randomized trial. Br J Anaesth. 2017;119:125–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howard SK, Gaba DM, Smith BE, Weinger MB, Herndon C, Keshavacharya S, Rosekind MR. Simulation Study of rested Versus Sleep-deprived anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:1345–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landrigan CP, Rothschild JM, Cronin JW, Kaushal R, Burdick E, Katz JT, Lilly CM, Stone PH, Lockley SW, Bates DW, Czeisler CA. Effect of reducing interns’ work hours on Serious Medical errors in Intensive Care Units. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1838–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gander PH, Merry A, Millar MM, Weller J. Hours of work and fatigue-related error: a survey of New Zealand anaesthetists. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2000;28:178–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rothschild JM. Risks of complications by attending Physicians after performing Nighttime procedures. JAMA. 2009;302:1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taffinder NJ, McManus IC, Gul Y, Russell RCG, Darzi A. Effect of sleep deprivation on surgeons’ dexterity on laparoscopy simulator. Lancet. 1998;352:1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaida K, Takahashi M, Akerstedt T, Nakata A, Otsuka Y, Haratani T, Fukasawa K. Validation of the Karolinska sleepiness scale against performance and EEG variables. Clin Neurophysiol. 2006;117:1574–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lubarsky S, Dory V, Duggan P, Gagnon R, Charlin B. Script concordance testing: from theory to practice: AMEE Guide 75. Med Teach. 2013;35:184–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charlin B, van der Vleuten C. Standardized assessment of reasoning in contexts of uncertainty: the script concordance approach. Eval Health Prof. 2004;27:304–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charlin B, Brailovsky C, Leduc C, Blouin D. The diagnosis script questionnaire: a New Tool to assess a specific dimension of clinical competence. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 1998;3:51–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clavier T, Ramen J, Dureuil B, Veber B, Hanouz J-L, Dupont H, Lebuffe G, Besnier E, Compere V. Use of the Smartphone App WhatsApp as an E-Learning method for medical residents: Multicenter Controlled Randomized Trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019; 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Enser M, Moriceau J, Abily J, Damm C, Occhiali E, Besnier E, Clavier T, Lefevre-Scelles A, Dureuil B, Compère V. Background noise lowers the performance of anaesthesiology residents’ clinical reasoning when measured by script concordance: a randomised crossover volunteer study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2017;34:464–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Compère V, Moriceau J, Gouin A, Guitard P-G, Damm C, Provost D, Gillet R, Fourdrinier V, Dureuil B. Residents in tutored practice exchange groups have better medical reasoning as measured by the script concordance test: a pilot study. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2015;34:17–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Compère V, Abily J, Moriceau J, Gouin A, Veber B, Dupont H, Lorne E, Fellahi JL, Hanouz JL, Gerard JL, Sibert L, Dureuil B. Residents in tutored practice exchange groups have better medical reasoning as measured by script concordance test: a controlled, nonrandomized study. J Clin Anesth. 2016;32:236–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kahneman D. Thinking, fast and slow. New York, NY, US, Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 2011. p. 499.

- 21.Norman GR, Monteiro SD, Sherbino J, Ilgen JS, Schmidt HG, Mamede S. The causes of errors in clinical reasoning: cognitive biases, knowledge deficits, and dual process thinking. Acad Med. 2017;92:23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haslam DR. Sleep loss, recovery sleep, and military performance. Ergonomics. 1982;25:163–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Opstad PK, Ekanger R, Nummestad M, Raabe N. Performance, mood, and clinical symptoms in men exposed to prolonged, severe physical work and sleep deprivation. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1978;49:1065–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Samkoff JS, Jacques CH. A review of studies concerning effects of sleep deprivation and fatigue on residentsʼ performance. Acad Med. 1991;66:687–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Philibert I. Sleep loss and performance in residents and nonphysicians: a Meta-Analytic examination. Sleep. 2005;28:1392–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gottlieb DJ, Parenti CM, Peterson CA, Lofgren RP. Effect of a change in house staff work schedule on resource utilization and patient care. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:2065–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lockley SW, Cronin JW, Evans EE, Cade BE, Lee CJ, Landrigan CP, Rothschild JM, Katz JT, Lilly CM, Stone PH. Effect of reducing interns’ weekly work hours on sleep and attentional failures. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1829–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Persico N, Maltese F, Ferrigno C, Bablon A, Marmillot C, Papazian L, Roch A. Influence of Shift Duration on Cognitive Performance of Emergency Physicians: a prospective cross-sectional study. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;72:171–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bijok B, Jaulin F, Picard J, Michelet D, Fuzier R, Arzalier-Daret S, Basquin C, Blanié A, Chauveau L, Cros J, Delmas V, Dupanloup D, Gauss T, Hamada S, Le Guen Y, Lopes T, Robinson N, Vacher A, Valot C, Pasquier P, Blet A. Guidelines on human factors in critical situations 2023. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2023;42:101262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kepros J, Haag S, Lewandowski K, Bauer F, Ali H, Markowski H, Green D, Najafi K, Sheppard T. Shift length and shift length preference among Acute Care surgeons. Am Surg. 2023;89:372–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Estabrooks CA, Cummings GG, Olivo SA, Squires JE, Giblin C, Simpson N. Effects of shift length on quality of patient care and health provider outcomes: systematic review. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:181–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reed DA, Fletcher KE, Arora VM. Systematic review: association of shift length, protected sleep time, and night float with patient care, residents’ health, and education. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:829–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taber KS. The Use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Res Sci Educ. 2018;48:1273–96. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ducos G, Lejus C, Sztark F, Nathan N, Fourcade O, Tack I, Asehnoune K, Kurrek M, Charlin B, Minville V. The script concordance test in anesthesiology: validation of a new tool for assessing clinical reasoning. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2015;34:11–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Zambotti M, Goldstone A, Claudatos S, Colrain IM, Baker FC. A validation study of Fitbit Charge 2™ compared with polysomnography in adults. Chronobiol Int. 2018;35:465–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.