Abstract

The common pochard (Aythya ferina) is a freshwater diving duck found in the Palearctic region that has been classified as vulnerable by the IUCN due to continuous and rapid population declines across their distribution. To gain a better understanding of its genetic mechanism of adaptive evolution, we successfully sequenced and assembled the first high-quality chromosome-level genome of A. ferina using Illumina, Nanopore and Hi-C sequencing technologies. A total assembly length of 1,130.78 Mbp was obtained, with over 98.81% (1,117.37Mbp) of sequence anchored to 35 pseudo-chromosomes. We predicted 17,232 protein-coding genes, 95.9% of which were functionally annotated. We identified 339 expanded and 937 contracted gene families in the genome of A. ferina, and detected 95 genes that have been positively selected. The significantly enriched Gene Ontology and enriched pathways were related to energy metabolism, immune, nervous, and sensory systems, suggests that these factors likely played an important role in its evolution. Importantly, we recovered signatures of positive selection on genes related to vasoconstriction that may be associated with thermoregulatory adaptations of A. ferina for underwater diving. Overall, the high-quality genome assembly and annotation in this study provides valuable genomic resources for ecological and evolutionary studies, as well as toward the conservation of A. ferina.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12864-024-10846-6.

Keywords: Aythya ferina, Whole-genome sequencing, Evolution, Diving, Positive selection

Background

Aquatic birds have been secondarily adapted to live and forage in water environment during their evolution. Birds are endotherms with extremely high basal metabolic rates [1], which pose evolutionary challenges to species adapting to environments characterized by faster heat transfer rates and lower temperatures (e.g., genus Aythya) [2]. In particular, many aquatic birds are challenged by their capacity for oxygen storage and elevated levels of hydrostatic pressures as they dive [3]. Underwater, these birds rely solely on the oxygen reserves within their bodies for generating ATP through aerobic processes, with oxygen stores primarily bound to hemoglobin (Hb) and myoglobin (Mb) [4]. Notably, observations of physiological characteristics in diving birds have revealed a positive correlation between myoglobin concentration and increased dive durations [5], emphasizing the critical role that these oxygen-binding molecules play in the adaptation of aquatic birds to their submerged lifestyles.

The common pochard (Aythya ferina) is a freshwater diving duck found across the Palearctic region, and is known to be able to have a diving depth of up to 5 m [6], and dive durations typically under 20 s [7]. Unfortunately, more recent and constant population declines across their range resulted in its reclassified from least concern to vulnerable by the IUCN in 2015 [8]. Specifically, common pochard has undergone a significant decrease across its habitat, particularly in key migration routes, with average annual declines of 5.97% and 2.16% from 2003 to 2012 in the Northwestern and Central European Flyways, respectively [9]. Population declines have been attributed to increasingly unbalanced sex ratio [10], human-induced habitat destruction and loss, as well as influenza virus infection [11]. The species is dichromatic with males possessing a distinctive red head and neck, red eyes, black breast, grey back and dark bill-band, while females being largely brown and gray throughout (https://birdsoftheworld.org/). To date, few molecular studies exist for the common pochard, many of which predominantly centered around few microsatellite loci [12, 13].

Here, we successfully sequence and assemble a high-quality genome of the common pochard, and aim to shed light into the evolutionary adaptations associated with its aquatic ecology and diving habits. To do so, we conducted comparative genomics analyses with the tufted duck (Aythya fuligula), as well as other Anatidae relatives. Through this exploration, we aim to identify genetic modifications in the common pochard that played pivotal roles in their evolution.

Methods

Genome sequencing and assembly

A A. ferina was opportunistically sampled and sourced from Jiangsu, China and was done under the Biomedical Ethics Committee of Qufu Normal University (approval number: 2021096). The samples were stored at -80 ℃ and used for DNA extraction, sequencing, and Hi-C library construction. Paired-end Illumina sequencing libraries with insertion sizes of 350 bp were constructed with a KAPA HyperPlus kit (Illumina) and sequenced (2 × 150 base pairs, bp) on the Illumina Novaseq 6000 platform, and single-molecule real-time sequencing of long reads was conducted using the PromethION platform (ONT, Oxford, UK). Transcriptome sequencing was performed on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 for samples of heart, liver, muscle, blood, and pancreas, with the combined data subsequently used for gene prediction. We generated a total of 63.24Gbp Illumina reads, 122.3 Gbp Nanopore reads, and 185.54 Gbp of Hi-C reads for common pochard. The genome size of common pochard was predicted by k-mer distribution analysis (k = 17) of jellyfish v2.2.7 (parameters: -G 2 -m 17 -o kmercount). Then we assembled the common pochard genome based on the filtered Nanopore sequencing data using NextDenovo v2.4.0 (https://github.com/Nextomics/NextDenovo) with default parameters. Following, NextPolish v1.3.1 [14] was used to correct error based on the Illumina raw data and Nanopore sequencing data. We applied Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO v5.2.1) [15] analysis to evaluate genome quality and completeness with the bird ortholog library (aves_odb10).

Genome annotation

De novo and homology-based predictions were used to annotate respective elements in A. ferina. First, we constructed a de novo transposable element database using RepeatModeler v1.0.8 (-engine ncbi -pa 15) [16], LTR-FINDER v1.0.6 (-C -w 2) [17], and RepeatScout v1.0.5 [18], and then used RepeatMasker v4.1.0 (-a -nolow -no_is -norna -parallel 64) [19] to detect the repeat elements in the database. For homologous annotations, RepeatMasker and RepeatProteinMasker v4.0.5 were used to predict transposable elements via the compare with data from Repbase. Then we used Tandem Repeats Finder v4.0.7 to make predictions for tandem repeat sequences.

The repeat masked genome was used for the next protein-coding genes annotation. We used a combination of ab initio predictions, homology-based prediction and RNA-Seq prediction to identify genes structure on the common pochard genome. First, Augustus v3.2.3 (--species = chicken) [20], GlimmerHMM v3.04 [21], Geneid v1.4 [22], SNAP [23], and Genescan v1.0 [24] were implemented to generate ab initio predictions. Then for homology-based predictions, we downloaded the protein sequences from seven species from the NCBI database and applied TblastN v2.2.26 [25] to align genomic sequences. Moreover, RNA sequence data derived from heart, liver, muscle, and pancreatic tissue, as well as blood were matched to the genomic sequences using TopHat v2.0.11 [26]. GeneWise v2.4.1 (-tfor -genesf -gff -sum) [27] was applied to inference gene models with all the aligned sequences against the homologous genomic sequence. Finally, the non-redundant predict reference gene set was integrated from above three methods using Evidence Modeler (EVM) v1.1.1(--segmentSize 200000 –overlapSize 20000 --min_intron_length 20) [28]. To assess the function of the predicted genes of A. ferina, we mapped them to Nr form NCBI, KEGG [29], GO [30], Pfam [31], InterPro [32] and SwissProt [33] databases using BLAST [34] with an E-value cutoff of 1E-5.

Additionally, snRNA and miRNA were predicted through a search of the Rfam database [35] using INFERNAL (http://infernal.wustl.edu/) with the default parameters. Human rRNA sequences were chosen as a reference and BLAST was applied to inference the rRNA sequences of A. ferina. The program tRNASCAN-SE [36] were used to predict the tRNAs of A. ferina.

Phylogenetic analysis and divergence time estimation

OrthoFinder v2.4.0 (-f pep -S diamond -t 64 -a 64) [37] was used to identify orthologous genes from A. ferina and from the mallard (Anas platyrhynchos), Swan goose (Anser cygnoides), White-winged Duck (Asarcornis scutulata), tufted duck (Aythya fuligula), southern screamer (Chauna torquata), black swan (Cygnus atratus), mute swan (Cygnus olor), rock ptarmigan (Lagopus muta), and chicken (Gallus gallus). All comparative species were chosen based on genome quality and close relatedness to our target species. The Diamond v2.0.13 program [38] was used for sequence similarity searches. MUSCLE v3.8.31 [39] was applied to align the amino acid coding sequences of the single-copy orthologous genes. Then the sequence alignments were translated into codon alignments using the Perl script PAL2NAL [40].A phylogenetic trees was then constructed with single-copy orthologous genes using RAxML v8.1.12 (-m GTRGAMMA -f a -x 12345 -N 100 -p 12345 -T 64) [41], and with the application of a GTR-GAMMA substitution model, Nodal support was based on 1,000 bootstrap replicates. Next, we used the recovered maximum-likelihood trees as input for ASTRAL v5.5.9 (-i all.gene.tree -o astral.bs.tre -b bootstrap.txt) [42], and with the divergence times estimated using the MCMCtree program (-clock 2 -alpha 0.5 -model 3) in PAML v4.7 [43]. Note that we first applied baseml program to estimate the alpha parameter under REV substitution model and substitution rate per time unit. Four calibration time points were used for the estimation of divergence time based on the Timetree database [44].

Gene family and evolutionary analyses

We estimated the expansion and contraction of gene families using CAFE5 (-i gene_families_filter.txt -t tree.txt -p -k 3 -c 30 -o k3) [45], with a random birth and death model applied to infer gene loss and gain in gene families within the specific lineages. The global parameter λ (lambda) was estimated using maximum likelihood method. The gene family with conditional p-values < 0.05 was defined as the “significantly expanded and contracted gene family”. The comparisons of nonsynonymous (dN)/synonymous (dS) substitution ratios (ω) have proven to be an efficient approach to estimate the impact of natural selection on molecular evolution by examining the selective constrains on candidate genes. Values of ω > 1, ω = 1 and ω < 1 represent positive selection, neutral selection and purifying selection, respectively. The codon-based maximum likelihood models performed in the CODEML program of PAML were used to compute the ω value. Branch (two-ratio) model (model = 2, NSsites = 0) that allows foreground and background branches to have different ω, were performed to evaluate the ω values between A. ferina and other relatives. To detect A. ferina specific positive selection, we used A. ferina as the foreground branches and the remaining lineages as the background branches. Two ratio model was compared with the one-ratio model (model = 0, NSsites = 0) that enforces a same ω ratio for all lineages, and these two nested models are compared using the likelihood ratio test (LRTs). A chi-square (χ2 distribution) was used to test between models. GO and KEGG enrichment analyses were applied on the significant expanded gene families and PSGs (positively selected genes), and Fisher’s test was used to enhance the accuracy of the conducted χ2 test.

Demographic history reconstruction

The demographic history of A. ferina was analyzed using the PSMC (pairwise sequentially Markovian coalescent) version v 0.6.5-r67 method [46]. First, diploid genome references were constructed with Samtools and bcftools using parameters “samtools mpileup -C 30” and “vcfutils.pl vcf2fq -d 10 -D 100”. Changes in the effective population size (Ne) of A. ferina were then inferred by PSMC, employing the parameters “-N25 -t15 -r5 -p “4 + 25*2 + 4 + 6””, following the approach described by Warren et al. [47]. The variation in the simulation outcomes was evaluated using 100 bootstrap replicates. The estimated generation time (g) of four years and the mutation rate per generation per site (µ) of 6.4*10− 9 [48–50] were applied to visualize the PSMC graph using “psmc_plot.pl” script.

Results

Genome size estimation and genome assembly

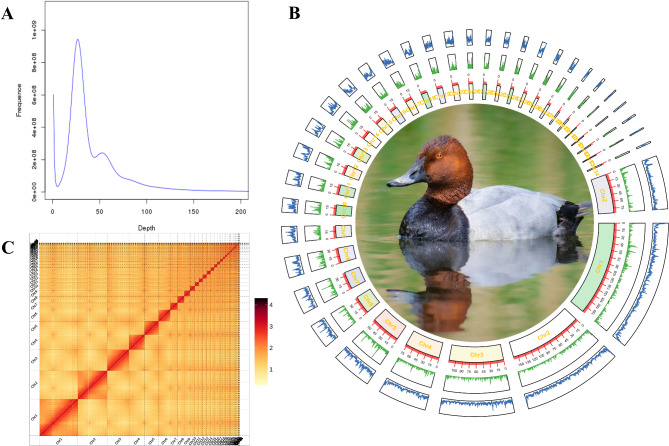

We achieved a chromosome-scale genome assembly for the common pochard with high quality, contiguity, and accuracy by coupling Illumina, Oxford Nanopore, and Hi-C sequences. A total of 185.54 Gb reads (63.24 Gb Illumina reads and 122.30 Gb Nanopore) were generated (Table S1) prior to additional cleaning. The k-mer (k = 17) depth frequency distribution analysis of the 44.51Gb clean Illumina data was used to evaluate the genome size and heterozygosity of common pochard. Based on the total number of 31,523,925,616 17-mers and a peak 17-mer depth of 26 (Fig. 1A), the evaluated genome size of common pochard was ~ 1,189.33 Mb, with an estimated heterozygosity of ~ 0.49%.

Fig. 1.

Genome analysis of Aythya ferina. A: Genome survey using 17-mer analysis. B: Circos plotting for inner to outer: A. ferina image from the web “Birds of the World” (https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/home), Chromosome, gene density, and GC content. C: Hi-C interaction heatmap

All reads were assembled into the 1,130.78 Mb genome, which consisted of 159 contigs with an N50 size of 31.43 Mb, representing a high-quality assemble of A. ferina genome. The assembled genome size was smaller than the estimated one by k-mer analysis, and this might be caused by deletion of the highly overlapped contigs. Our assembled genome is 1.13 Gbp, consistent with genome size of other species in the Anatidae [51, 52]. For the chromosome-level assembly, the Hi-C library data were anchored and orientated onto 35 pseudo-chromosomes (Fig. 1B), and the mapping length is 1,117.37 Mb (range in size from 1.62 to 207.33 Mb) and covering ~ 98.81% of all sequences (Table S2). The heatmap of the pseudo-chromosome crosstalk demonstrated that the genome assembly of A. ferina was complete and robust (Fig. 1C). The GC content of this genome was 41.91% (Table S3) that is consistent to other genomes (e.g., A. fuligula 41.72%, GenBank ID: GCA_009819795.1). The BUSCO analysis suggested that 97.0% (single-copied gene: 96.5%, duplicated gene: 0.5%) of 8338 groups in the aves_odb10 database were identified as complete, 0.6% of genes were fragmented, and 2.4% of genes were missing in the assembled genome (Fig. 2A). Then, CEGMA analysis found that 234 complete conserved genes (94.35% of the core eukaryotic genes) indicated the completeness of the assembled genome. Next, Illumina reads were mapped to the genome using BWA v0.7.8, with 99.45% of reads mapped covering 99.8% of the assembled genome (Table S4).

Fig. 2.

A: BUSCO assessment results of A. ferina genome. B: Flower plot of single-copy genes and specific genes of each species. C: Maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis of A. ferina and other relative species.Each branch site shows the estimated species divergence time. D: Phylogeny with expanded/contracted gene families. The blue bars indicate the number of gene families that expanded during the evolution of the species and the orange bars indicate the number of gene families that contracted

Genome annotation

After the integration of TRF, RepeatMasker and RepeatProteinMasker results and deletion of redundancy, repeat sequence prediction analysis found that the proportion of repeat sequences is 12.39% of A. ferina genome (Table S5). Among the classified repeat elements, LRT elements are most abundant in A. ferina genome (7.40%), followed by LINE repeats (5.45%) and DNA repeats (0.12) (Table S6). After masking the repeat elements, we combined the de novo gene predictions, homologous sequence searches and RNA-assisted annotations to get a total of 17,232 protein-coding genes in the A. ferina genome. Annotation results showed that the average transcript length was 24,112.25 bp, with the average CDS (coding sequence) length of 1,671.71 bp. The average exon per gene was 10.03, with an average exon length of 166.73 bp and average intron length of 2,486.08 bp (Table S7). Comparing CDS length, exon length, exon number, gene length and intron length with those of other six avian species suggests that our annotation of A. ferina genome was comprehensive (Figure S1). A total of 16,522 genes, which account for 95.9% of the predicted genes, were finally annotated with predicted function (Table 1). Our functional annotation showed that 15,345(89%), 15,891(92.2%), 14,347(83.3%), 16,338(94.8%) and 14,261(82.8%) genes had significant hits with Swissprot, Nr, KEGG, InterPro and Pfam, respectively. In addition, 350 miRNA, 409 tRNA, 170rRNA and 310 snRNA were identified in A. ferina genome, which have an average length of 88.93, 75.02, 206.72 and 127.55 bp, respectively (Table 2).

Table 1.

Annotation of predicted genes in A. ferina genome

| Number | Percent (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 17,232 | 100.00 |

| Swissprot | 15,345 | 89.00 |

| Nr | 15,891 | 92.20 |

| KEGG | 14,347 | 83.30 |

| InterPro | 16,338 | 94.80 |

| GO | 11,841 | 68.70 |

| Pfam | 14,261 | 82.80 |

| Annotated | 16,522 | 95.90 |

Table 2.

The statistical result of non-coding RNA in A.ferina genome

| Type | Copy number | Average length(bp) | Total length(bp) | Percent of genome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miRNA | 350 | 88.93 | 31,126 | 0.002753 | |

| tRNA | 409 | 75.02 | 30,685 | 0.002714 | |

| rRNA | rRNA | 170 | 262.72 | 44,663 | 0.003950 |

| 18 S | 24 | 509.79 | 12,235 | 0.001082 | |

| 28 S | 91 | 283.49 | 25,798 | 0.002281 | |

| 5.8 S | 7 | 141.57 | 991 | 0.000088 | |

| 5 S | 48 | 117.48 | 5,639 | 0.000499 | |

| snRNA | snRNA | 310 | 127.55 | 39,540 | 0.003497 |

| CD-box | 122 | 94.80 | 11,565 | 0.001023 | |

| HACA-box | 84 | 144.64 | 12,150 | 0.001074 | |

| splicing | 82 | 145.89 | 11,963 | 0.001058 | |

| scaRNA | 21 | 181.10 | 3,803 | 0.000336 | |

| Unknown | 1 | 59 | 59 | 0.000005 | |

Genome comparison

Based on the identified orthologous gene sets, 10,051 core orthologous genes were obtained and the specific genes of each species was displayed in Fig. 2B. Combining published genome data (Table 3) with our A. ferina genome, we were able to provide a reliable phylogenomic reconstruction. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using 8,757 single-copy orthologs of A. ferina and nine other birds. The overall phylogenetic relationship of ten birds is consistent with previous studies [53]. Specifically, we found that A. ferina was sister to A. fuligula, with a divergence time of ~ 5.36 million years ago (Mya) (Fig. 2C).

Table 3.

Genome information of nine relative species

| Species | Version | Accession | Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anas platyrhynchos | ZJU1.0 | GCA_015476345.1 | 143.0x |

| Anser cygnoides | GooseV1.0 | GCA_002166845.1 | 56.2x |

| Asarcornis scutulata | ASM1339847v1 | GCA_013398475.1 | 110x |

| Aythya fuligula | bAytFul2.pri | GCA_009819795.1 | 64.03x |

| Chauna torquata | ASM1339947v1 | GCA_013399475.1 | 45x |

| Cygnus atratus | Cygnus_atratus_primary_v1.0 | GCA_013377495.1 | 90X |

| Cygnus olor | bCygOlo1.pri.v2 | GCF_009769625.2 | 60.23x |

| Lagopus muta | bLagMut1 primary | GCF_023343835.1 | 57.8 |

| Gallus gallus | bGalGal1.mat.broiler.GRCg7b | GCF_016699485.2 | 102.0x |

We next explored the expansion and contraction of gene families in A. ferina lineage. Gene family analysis of A. ferina and other relatives recovered a core set of 16,277 gene families, with 12,981 gene families were shared by the two Aythya species. In short, we recovered a total of 339 expanded gene families and 937 contracted gene families were identified in A. ferina (Fig. 2D), with 101 and 228 gene families found to have undergone significant expansion and contraction (p < 0.05), respectively. The enrichment analysis of the expanded genes showed that they were significantly enriched in 55 GO terms and 118 KEGG pathways. Importantly, we recovered expanded gene families to be significantly enriched in ATP binding (GO:0005524), oxidoreductase activity (GO:0016491), and protein kinase activity (GO:0004672) terms (Fig. 3A). Moreover, KEGG functional enrichment analysis (Fig. 3B) showed that these expanded gene families were mainly related to lipid metabolism (ko00071, atty acid degradation), Amino acid metabolism (ko00310, Lysine degradation; ko00310, Arginine and proline metabolism), Glycan biosynthesis and metabolism (ko00514, other types of O-glycan biosynthesis; ko00534, Glycosaminoglycan biosynthesis), immune system (ko04610, Complement and coagulation cascades; ko04611, Platelet activation; ko04620, Toll-like receptor signaling pathway and ko04625 C-type lectin receptor signaling pathway etc.), nervous system, sensory system, and multiple diseases-related pathways (Table S8). Gene family analysis also identifies 254 gene families that participated in diverse biological processes that may be important for pochard lineage-specific adaptations.

Fig. 3.

Enrichment analysis for expanded gene families by GO (A) and KEGG (B), and for positively selected genes by GO (C) and KEGG (D). The top items in each class were displayed

Applying positive selection analyses using branch model in PAML, we detected 95 and 79 positively selected genes (PSGs) in A. ferina and genus Aythya, respectively. And there were 57 PSGs in both. The GO enrichment analyses of PSGs in A. ferina showed significant terms associated with vasoconstriction (GO:0042310), transcription regulator complex (GO:0005667), G protein-coupled receptor activity (GO:0004930) and RNA methyltransferase activity (GO:0008173) etc. (Fig. 3C). The KEGG enrichment analyses revealed significant pathways related to metabolism, including Caffeine metabolism (ko00232), Phosphonate and phosphinate metabolism (ko00440), Cyanoamino acid metabolism (ko00460), Vitamin B6 metabolism (ko00750), Biotin metabolism (ko00780) and Sulfur metabolism (ko00920). The significant pathway also related to Cellular Processes (Quorum sensing, ko02024; Cell cycle, ko04110), immune system (Antigen processing and presentation, ko04110), Environmental adaptation (Circadian rhythm, ko04711), Sensory system (Phototransduction, ko04744) and immune disease (Asthma, ko05310; Allograft rejection, ko05330; Graft-versus-host disease, ko05332) (Fig. 3D).

Demographic history

The PSMC indicated that the population of A. ferina reached its peak at the boundary between Gelasian (2.6 million − 1.8 million years ago) and Calabrian (1.8 million-781,100 years ago) in the early Pleistocene (2.6 million – 781,000 years ago). After that, two substantial population decrease during the early Pleistocene age and the middle Pleistocene age (781,100–126,000 years ago). And then the population decreased to its minimum at the early stage (about 71,000 years ago) of the late Pleistocene age (126,000–11,700 years ago) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Historical effective population size of A. ferina based on PSMC analysis. The thick red line represents the primary PSMC estimate derived from the original genomic data, while the lighter red lines depict bootstrap replicates, illustrating the variability and robustness of the PSMC estimates

Discussion

Here, we provided the first high-quality genome assembly to serve as an invaluable resource for studying evolution and adaptation of common pochard, as well as a resource for their future conservation. To date, molecular data on the common pochard have been scarce, with only the mitochondrial genome available [54]. In short, we employed a comprehensive sequencing strategy, integrating Illumina, Nanopore and Hi-C techniques, to assemble a chromosome-level genome of common pochard with high completeness. Doing so, we achieved a final total genome size of 1.13 Gb, with a super-scaffold was assembly for 35 pseudo-chromosomes. The assembly’s contig N50 is 31.43 Mb, which surpasses that of the tufted duck (17.8 Mb) [55], Pekin duck (5.46 Mb) [56] and chicken (16.72 Mb) [57]. The completeness of our assembly is further exemplified through BUSCO analysis that indicated remarkable completeness and accuracy for our A. ferina genome.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the expansion of certain pathways and gene families can impact diverse physiological processes and enhance a species’ adaptability to its environment [58, 59]. Unlike their terrestrial counterparts, diving birds have evolved to long interruptions in breathing that enable them to sustain an oxygen-based metabolism and physiological homeostasis while underwater [60]. In A. ferina, we hypothesize that under diving stress, the expansion of the lipid metabolism, glycan biosynthesis and metabolism, and amino acid metabolism pathways may play a role in regulating energy metabolism. Similarly, the common loon (Gavia immer), a freshwater aquatic diving bird, has evolved for underwater diving by regulating metabolic and oxidative pathways, with genes related to ATP metabolism, G-protein coupled receptors, and immunoglobulin function experiencing positive selection within the Gavia genus [61]. Indeed, we recovered similar trends when conducting a computational analysis of gene family sizes to estimate gene family expansion and contraction between A. ferina and the other nine species included in analyses. The expansion of immune-related pathways, such as toll-like receptor signaling pathway, suggests that A. ferina’s immune system has adapted to diving environment as found in other bird species (e.g., penguins [62]). Additionally, selection pressure analysis revealed that genes involved in vascular constriction have undergone strong positive selection in A. ferina as well. Previous research strongly suggests that multiple vasoconstriction-related genes in cetaceans have undergone adaptive evolution, enhancing their ability for vasoconstriction for reducing blood flow to the skin [63]. This suggest that, despite the short diving time and shallow diving depth, A. ferina has evolved robust vasoconstriction abilities to tolerate low-oxygen underwater environments and regulate its body temperature. We hypothesize that genes involved in metabolism and immunity in A. ferina may have been duplicated or positively selected to enhance the capability of energy production capabilities for diving adaptation. We also identified expanded gene families shared by A. ferina and A. fuligula, which may contribute to the adaptation of the Aythya genus to diving behavior under low oxygen and water condition. Finally, the expansion of nervous system, sensory system and diseases-related pathways may help A. ferina to cope with environmental challenges more efficiently [64]. We conclude that our genome recovers the genetic basis of diving adaptation in the metabolic, immune, and the sensory system, showing evidence for co-evolution of multiple system specific to the underwater environments.

Estimating the historical effective population size is fundamentally interconnected with our comprehension of a species’ evolutionary history [65]. This information provides valuable insights into the historical population dynamics and the impact of past events such as environmental shifts, hybridization, migrations, or disease outbreaks [66]. The PSMC model estimates coalescent time distributions between alleles across chromosomes using heterozygous site density in a diploid genome, which can be converted into effective population size. We recovered two substantial population declines during Pleistocene, potentially attributable to glacial and interglacial cycles of the Pleistocene era. The regular occurrence of population bottlenecks, followed by expansions, is anticipated to have diminished the effective population sizes. Findings on historical dynamics in A. ferina can inform conservation planning decisions for its wild populations.

Conclusions

In summary, we have successfully assembled a high-quality genome for the A. ferina, with genomic comparisons revealing that A. ferina is closely related to A. fuligula, with a divergence time estimated at ~ 5.36 Mya. Our evolutionary analysis has identified expanded gene families and positively selected genes that are likely associated with adaptations to underwater environments. These findings significantly enhance our understanding of diving adaptation of A. ferina. Highlighted genes provide a crucial foundation for further investigations into the molecular mechanisms that drive the diving adaptation of A. ferina and other diving birds. Meanwhile, our study provides a good example of how diving birds adapt to underwater environments and provides a valuable and comprehensive genomic resource for future population genomes research. In essence, our work provides a genomic resource that will benefit evolutionary biology and conservation genetics within the pochard lineage. The high-quality genome assembly and annotation are pivotal for deepening our understanding of the genetic basis of diving adaptations and will support future studies in this field.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

T.X., X.D.G., and H.H.Z. wrote the main manuscript text, L.Z., S.Y.Z., Z.H.Z. and J.Q.D. prepared figures, G.L.S. and X.F.Y. prepared tables. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32200407 and 32270444), the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2023ZD47), and the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF (GZC20231395).

Data availability

The data that support the findings in this study have been deposited into National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI: PRJNA951943). The genome annotation was submitted to Figshare. URL: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25663320.v1.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The A. ferina sample obtained in Jiangsu, China died unexpectedly during rescue and was used for whole genome sequencing. The experimental procedures were approved by the Biomedical Ethics Committee of Qufu Normal University (Approval number: 2021096).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Tian Xia, Xiaodong Gao and Lei Zhang contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Xu X, Zhou ZH, Dudley R, Mackem S, Chuong CM, Erickson GM, Varricchio DJ. An integrative approach to understanding bird origins. Science. 2014;346(6215):1253293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pelletier D, Guillemette M, Grandbois J-M, Butler P. To fly or not to fly: high flight costs in a large sea duck do not imply an expensive lifestyle. Proc Biol Sci / Royal Soc. 2008;275:2117–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butler PJ, Jones DR. Physiology of diving of birds and mammals. Physiol Rev. 1997;77(3):837–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butler PJ. Metabolic regulation in diving birds and mammals. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2004;141(3):297–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wright TJ, Davis RW. Myoglobin oxygen affinity in aquatic and terrestrial birds and mammals. J Exp Biol. 2015;218(14):2180–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Leeuw JJ, Van Eerden MR, SIZE SELECTION IN DIVING TUFTED DUCKS AYTHYA-FULIGULA EXPLAINED BY DIFFERENTIAL HANDLING OF SMALL AND LARGE MUSSELS DREISSENA-POLYMORPHA. Ardea 1992.

- 7.Stephenson R, Butler PJ, Woakes AJ. Diving behaviour and heart rate in tufted ducks (Aythya fuligula). J Exp Biol. 1986;126:341–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mischenko A, Fox AD, Svazas S, Sukhanova O, Czajkowski A, Kharitonov S, Lokhman Y, Ostrovsky O, Vaitkuviene D. Recent changes in breeding abundance and distribution of the Common Pochard (Aythya ferina) in its eastern range. Avian Res 2020, 11(1).

- 9.Nagy S, Flink S, Langendoen T. Waterbird trends 1988–2012. Results of trend analyses of data from the International Waterbird Census in the African-Eurasian Flyway 2014.

- 10.Carbone C, Owen M. Differential migration of the sexes of Pochard Aythya ferina: results from a European survey. In: 1995; 1995.

- 11.Keller I, Korner-Nievergelt F, Jenni L. Within-winter movements: a common phenomenon in the common Pochard Aythya ferina. J Ornithol. 2009;150(2):483–94. [Google Scholar]

- 12.St’ovicek O, Cizkova D, Liu Y, Albrecht T, Heckel G, Vyskocilova M, Kreisinger J. Development of microsatellite markers for a diving duck, the common pochard (Aythya ferina). Conserv Genet Resour. 2011;3(3):573–6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stovicek O, Kreisinger J, Javurkova V, Albrecht T. High rates of conspecific brood parasitism revealed by microsatellite analysis in a diving duck, the common pochard Aythya ferina. J Avian Biol. 2013;44(4):369–75. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu J, Fan J, Sun Z, Liu S. NextPolish: a fast and efficient genome polishing tool for long-read assembly. Bioinformatics. 2020;36(7):2253–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simão FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(19):3210–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flynn JM, Hubley R, Goubert C, Rosen J, Clark AG, Feschotte C, Smit AF. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(17):9451–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu Z, Wang H. LTR_FINDER: an efficient tool for the prediction of full-length LTR retrotransposons. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(Web Server issue):W265–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Price AL, Jones NC, Pevzner PA. De novo identification of repeat families in large genomes. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(Suppl 1):i351–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen N. Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Curr Protoc Bioinf 2004, Chap. 4:Unit 4.10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Stanke M, Waack S. Gene prediction with a hidden Markov model and a new intron submodel. Bioinformatics. 2003;19(Suppl 2):ii215–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Majoros WH, Pertea M, Salzberg SL. TigrScan and GlimmerHMM: two open source ab initio eukaryotic gene-finders. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(16):2878–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parra G, Blanco E, Guigó R. GeneID in Drosophila. Genome Res. 2000;10(4):511–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korf I. Gene finding in novel genomes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004;5:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burge C, Karlin S. Prediction of complete gene structures in human genomic DNA. J Mol Biol. 1997;268(1):78–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gertz EM, Yu YK, Agarwala R, Schäffer AA, Altschul SF. Composition-based statistics and translated nucleotide searches: improving the TBLASTN module of BLAST. BMC Biol. 2006;4:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trapnell C, Pachter L, Salzberg SL. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(9):1105–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Birney E, Clamp M, Durbin R. GeneWise and Genomewise. Genome Res. 2004;14(5):988–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haas BJ, Salzberg SL, Zhu W, Pertea M, Allen JE, Orvis J, White O, Buell CR, Wortman JR. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the program to assemble spliced alignments. Genome Biol. 2008;9(1):R7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(1):27–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25(1):25–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Finn RD, Bateman A, Clements J, Coggill P, Eberhardt RY, Eddy SR, Heger A, Hetherington K, Holm L, Mistry J, et al. Pfam: the protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(D1):D222–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Finn RD, Attwood TK, Babbitt PC, Bateman A, Bork P, Bridge AJ, Chang HY, Dosztányi Z, El-Gebali S, Fraser M, et al. InterPro in 2017-beyond protein family and domain annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(D1):D190–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bairoch A, Apweiler R. The SWISS-PROT protein sequence database and its supplement TrEMBL in 2000. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(1):45–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215(3):403–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Griffiths-Jones S, Moxon S, Marshall M, Khanna A, Eddy SR, Bateman A. Rfam: annotating non-coding RNAs in complete genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(Database issue):D121–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chan PP, Lin BY, Mak AJ, Lowe TM. tRNAscan-SE 2.0: improved detection and functional classification of transfer RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(16):9077–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Emms DM, Kelly S. OrthoFinder: phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics. Genome Biol. 2019;20(1):238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buchfink B, Xie C, Huson DH. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat Methods. 2015;12(1):59–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(5):1792–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suyama M, Torrents D, Bork P. PAL2NAL: robust conversion of protein sequence alignments into the corresponding codon alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(Web Server issue):W609–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(9):1312–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mirarab S, Reaz R, Bayzid MS, Zimmermann T, Swenson MS, Warnow T. ASTRAL: genome-scale coalescent-based species tree estimation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(17):i541–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang Z. PAML: a program package for phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Comput Appl Biosci. 1997;13(5):555–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kumar S, Stecher G, Suleski M, Hedges SB. TimeTree: A Resource for timelines, timetrees, and divergence Times. Mol Biol Evol. 2017;34(7):1812–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mendes FK, Vanderpool D, Fulton B, Hahn MW. CAFE 5 models variation in evolutionary rates among gene families. Bioinformatics. 2020;36(22–23):5516–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li H, Durbin R. Inference of human population history from individual whole-genome sequences. Nature. 2011;475(7357):493–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Warren WC, Kuderna L, Alexander A, Catchen J, Pérez-Silva JG, López-Otín C, Quesada V, Minx P, Tomlinson C, Montague MJ, et al. The Novel evolution of the sperm whale genome. Genome Biol Evol. 2017;9(12):3260–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lavretsky P, Peters J, Winker K, Bahn V, Kulikova I, Zhuravlev Y, Wilson R, Barger C, Gurney K, McCracken K. Becoming pure: identifying generational classes of admixed individuals within lesser and greater scaup populations. Mol Ecol. 2015;25:n/a-n/a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bird J, Martin R, Akcakaya HR, Gilroy J, Burfield I, Garnett S, Symes A, Taylor J, Sekercioglu C, Butchart S. Generation lengths of the world’s birds and their implications for extinction risk. Conserv Biol 2020, 34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Zhang G, Li C, Li Q, Li B, Larkin DM, Lee C, Storz JF, Antunes A, Greenwold MJ, Meredith RW, et al. Comparative genomics reveals insights into avian genome evolution and adaptation. Science. 2014;346(6215):1311–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gao G, Zhao X, Li Q, He C, Zhao W, Liu S, Ding J, Ye W, Wang J, Chen Y, et al. Genome and metagenome analyses reveal adaptive evolution of the host and interaction with the gut microbiota in the goose. Sci Rep. 2016;6:32961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou SY, Xia T, Gao XD, Lyu T, Wang LD, Wang XB, Shi LP, Dong YH, Zhang HH. A high-quality chromosomal-level genome assembly of Greater Scaup (< i > Aythya marila). Sci Data 2023, 10(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.González JA, Düttmann H, Wink M. Phylogenetic relationships based on two mitochondrial genes and hybridization patterns in Anatidae. J Zool. 2009;279:310–8. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhai H, Meng D, Li Z, Si Y, Yu H, Teng L, Liu Z. Complete mitochondrial genome of the common Pochard (Aythya ferina) from Ningxia Hui autonomous region, China. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 2022;7(1):62–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mueller RC, Ellström P, Howe K, Uliano-Silva M, Kuo RI, Miedzinska K, Warr A, Fedrigo O, Haase B, Mountcastle J et al. A high-quality genome and comparison of short- versus long-read transcriptome of the palaearctic duck Aythya fuligula (tufted duck). Gigascience 2021, 10(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Zhu F, Yin ZT, Wang Z, Smith J, Zhang F, Martin F, Ogeh D, Hincke M, Lin FB, Burt DW, et al. Three chromosome-level duck genome assemblies provide insights into genomic variation during domestication. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):5932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li M, Sun C, Xu N, Bian P, Tian X, Wang X, Wang Y, Jia X, Heller R, Wang M et al. De Novo Assembly of 20 chicken genomes reveals the undetectable phenomenon for thousands of Core genes on microchromosomes and subtelomeric regions. Mol Biol Evol 2022, 39(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Geda F, Declercq A, Decostere A, Lauwaerts A, Wuyts B, Derave W, Janssens GPJ. β-Alanine does not act through branched-chain amino acid catabolism in carp, a species with low muscular carnosine storage. Fish Physiol Biochem. 2015;41(1):281–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kralik G, Sak-Bosnar M, Kralik Z, Galović O. Effects of β-Alanine Dietary supplementation on concentration of Carnosine and quality of broiler muscle tissue. J Poult Sci. 2014;51(2):151–6. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Davis RW. A review of the multi-level adaptations for maximizing aerobic dive duration in marine mammals: from biochemistry to behavior. J Comp Physiol B-Biochemical Syst Environ Physiol. 2014;184(1):23–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gayk ZG, Le Duc D, Horn J, Lindsay AR. Genomic insights into natural selection in the common loon (Gavia immer): evidence for aquatic adaptation. BMC Evol Biol 2018, 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Fiddaman SR, Vinkler M, Spiro SG, Levy H, Emerling CA, Boyd AC, Dimopoulos EA, Vianna JA, Cole TL, Pan HL et al. Adaptation and cryptic pseudogenization in Penguin Toll-Like receptors. Mol Biol Evol 2022, 39(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Tian R, Wang Z, Niu X, Zhou K, Xu S, Yang G. Evolutionary Genetics of Hypoxia Tolerance in cetaceans during diving. Genome Biol Evol. 2016;8(3):827–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wan Q-H, Pan S-K, Hu L, Zhu Y, Xu P-W, Xia J-Q, Chen H, He G-Y, He J, Ni X-W, et al. Genome analysis and signature discovery for diving and sensory properties of the endangered Chinese alligator. Cell Res. 2013;23(9):1091–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nadachowska-Brzyska K, Burri R, Smeds L, Ellegren H. PSMC analysis of effective population sizes in molecular ecology and its application to black-and-white Ficedula flycatchers. Mol Ecol. 2016;25(5):1058–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.García-Berro A, Talla V, Vila R, Wai HK, Shipilina D, Chan KG, Pierce NE, Backström N, Talavera G. Migratory behaviour is positively associated with genetic diversity in butterflies. Mol Ecol. 2023;32(3):560–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings in this study have been deposited into National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI: PRJNA951943). The genome annotation was submitted to Figshare. URL: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25663320.v1.