Abstract

We have used a random hexamer phage library to delineate similarities and differences between the substrate specificities of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) proteases (PRs). Peptide sequences were identified that were specifically cleaved by each protease, as well as sequences cleaved equally well by both enzymes. Based on amino acid distinctions within the P3-P3′ region of substrates that appeared to correlate with these cleavage specificities, we prepared a series of synthetic peptides within the framework of a peptide sequence cleaved with essentially the same efficiency by both HIV-1 and FIV PRs, Ac-KSGVF↓VVNGLVK-NH2 (arrow denotes cleavage site). We used the resultant peptide set to assess the influence of specific amino acid substitutions on the cleavage characteristics of the two proteases. The findings show that when Asn is substituted for Val at the P2 position, HIV-1 PR cleaves the substrate at a much greater rate than does FIV PR. Likewise, Glu or Gln substituted for Val at the P2′ position also yields peptides specifically susceptible to HIV-1 PR. In contrast, when Ser is substituted for Val at P1′, FIV PR cleaves the substrate at a much higher rate than does HIV-1 PR. In addition, Asn or Gln at the P1 position, in combination with an appropriate P3 amino acid, Arg, also strongly favors cleavage by FIV PR over HIV PR. Structural analysis identified several protease residues likely to dictate the observed specificity differences. Interestingly, HIV PR Asp30 (Ile-35 in FIV PR), which influences specificity at the S2 and S2′ subsites, and HIV-1 PR Pro-81 and Val-82 (Ile-98 and Gln-99 in FIV PR), which influence specificity at the S1 and S1′ subsites, are residues which are often involved in development of drug resistance in HIV-1 protease. The peptide substrate KSGVF↓VVNGK, cleaved by both PRs, was used as a template for the design of a reduced amide inhibitor, Ac-GSGVFΨ(CH2NH)VVNGL-NH2. This compound inhibited both FIV and HIV-1 PRs with approximately equal efficiency. These findings establish a molecular basis for distinctions in substrate specificity between human and feline lentivirus PRs and offer a framework for development of efficient broad-based inhibitors.

The use of drug therapy regimens that include both protease inhibitors and reverse transcriptase inhibitors is now the standard for treatment of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection. However, rapid mutation that occurs during HIV replication leads to the development of drug-resistant strains of the virus. The combination of horizontal transmission of these drug-resistant strains of HIV-1 and evolution of drug-resistant variants has led to the highest-ever frequency of patients harboring drug-resistant versions of HIV-1. Mechanisms of resistance include alteration of the protease structure, which decreases the binding affinity of anti-HIV protease drugs (for reviews, see references 8 and 22). It is also postulated that the alteration of the primary structures of the natural cleavage sites for HIV-1 protease (PR) results in substrates that are more easily cleaved by the protease and therefore compete better against competitive inhibitors for the protease (4, 5, 18, 32).

Our efforts are centered on the development of broad-based inhibitors for HIV-1 PR that will inhibit wild-type (wt) HIV-1 PR, as well as drug-resistant mutants that may arise in response to drug treatment. We focused on the development of inhibitors that bind both HIV-1 PR and feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) PRs. By targeting PRs with similar alpha-carbon structures and diverse substrate specificities, we hope to develop antagonists that will inhibit both wt and drug-resistant forms of HIV-1 PR. This structure-based approach has been used in the development of TL-3, a competitive inhibitor that binds FIV PR with a Ki of 41 nM and HIV-1 PR with a Ki of 1.5 nM (15), with the reduced amide inhibitors (7) and with statine-based inhibitors (31). TL-3 also inhibits FIV, simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), HIV-1, and many drug-resistant clinical HIV-1 isolates ex vivo (B. Buhler, Y.-C. Lin, G. Morris, C.-H. Wong, D. D. Richman, J. H. Elder, and B. E. Torbett, unpublished data), and the crystal structures of both HIV-1 PR and FIV PR have been solved, cocrystallized with TL-3 (16). However, mutants of HIV-1 that are resistant to TL-3 have been generated (Buhler et al., unpublished). It is anticipated that studies to better understand the molecular basis for substrate-inhibitor specificities will provide a means to design inhibitors less susceptible to resistance development.

Due to the distinctions between HIV and FIV PRs, a comparative analysis can tell us much regarding the molecular basis for substrate specificity. Furthermore, at least six amino acid mutations common to drug-resistant mutants of HIV-1 PR are the same amino acids found in the homologous locations of wt FIV PR (15). Thus, learning more about the basis for differences in the substrate specificities between these two PRs may give insights into the mechanisms for drug resistance development.

In this study we use a combinatorial approach to identify substrates that are efficiently cleaved by HIV-1 PR and FIV PR. A random hexamer peptide library displayed on the phage gene III product was screened with wt HIV-1 PR for one round of selection followed by three rounds of selection with FIV PR. Substrates were selected from the library that were cleaved by FIV PR. Cleaved phage were individually regrown and screened with wt HIV-1 PR and FIV PR, along with phage clones that were previously selected by a screen of only HIV-1 PR (2). From these studies we identified substrates that are only efficiently cleaved by FIV PR or HIV-1 PR and substrates cleaved by both PRs. In addition, a peptide series was synthesized to define single amino acid changes in substrates that are responsible for the observed preferences of HIV-1 PR or FIV PR. This has aided in the development of rules regarding the molecular basis for specificity differences between HIV-1 PR and FIV PR using a combination of molecular modeling and substrate cleavage experiments.

Substrates that are efficiently cleaved by HIV-1 PR have been shown to serve as models for tightly binding inhibitors of HIV-1 PR (2). One of the substrates cleaved by both HIV-1 PR and FIV PR was used as a model for the design of a hydroxyethylene inhibitor and a reduced amide inhibitor to test for the ability to inhibit both HIV-1 PR and FIV PR. FIV PR had a greater affinity for the reduced amide inhibitor and HIV-1 PR had a greater affinity for the hydroxyethylene inhibitor, suggesting that retroviral PRs may not necessarily have a preference for the same transition state analogue.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Panning and selection of phage.

The random hexamer peptide phage library, fTC-LIB-N6, was constructed by insertion of an antibody epitope for antibody 3-E7 (Gramsch Laboratories, Schwabhausen, Germany) and a random hexamer peptide into the gene III product of the phage as described previously (24). Cleavage of phage at the random hexamer region results in loss of the antibody epitope and subsequent inability to detect the epitope with a combination of antibody 3-E7 and chemiluminescent reagents (Fig. 1). For the first round of phage selection, 2 × 1010 infective phage were incubated with 5 μg of HIV-1 PR/ml in 0.2 M NaCl and 0.1 M MES (morpholineethanesulfonic acid) for 2 h at 37°C as described previously (2), and the selected phage pool was designated as round 1.

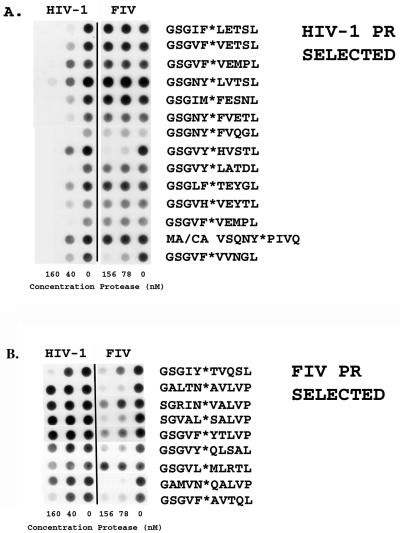

FIG. 1.

(A) Phage selected with wt HIV-1 PR, as described by Beck et al. (2) and cleaved with (from left to right) 160, 40, and 0 nM HIV-1 PR and 156, 78, and 0 nM FIV PR for 1 h at pH 6.7 in 0.2 M NaCl–0.1 M MES buffer. Cleavage of the phage at the random hexamer region results in loss of antibody epitope and loss of chemiluminescent signal on blots. (B) Phage selected with FIV PR and wt HIV-1 PR (see Materials and Methods). Phage were incubated according to the conditions described in the text.

FIV PR.

The round 1 library was amplified, and 2 × 1010 infective phage were then placed in a reaction with 1,200 nM FIV PR at 37°C for 1 h in 0.2 M NaCl and 0.1 M MES at pH 6.7. The cleaved phage were enriched and amplified according to described protocols (2), resulting in an FIV round 2 library. Infective phage, 2 × 1010, from the resulting amplified library were screened using the same protocol except with 200 nM FIV PR to produce FIV round 3 library. Infective phage (2 × 1010) from the resulting amplified library were then screened with 120 nM FIV PR under the same conditions described to produce an FIV round 4 library.

Phage titers were determined after each round of phage panning. Individual phage from each titer were picked from the titer plates and amplified using the methods described below in the phage dot blot section and then subjected to the dot blot procedure.

Phage dot blots of HIV-1 PR-selected phage: amplification of previously selected phage.

A total of 10 μl of phage at a titer of ca. 2 × 109 phage/μl that were previously selected by HIV-1 PR as described previously (2) were used to inoculate 100 μl of Escherichia coli (K91+) cells. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 30 min and then transferred to 10 ml of Circle Grow medium containing 20 μg of tetracycline/ml, and the culture was grown at 37°C overnight. The following day, the cells were spun at 2,600 rpm for 30 min. The supernatant (containing phage) was transferred to a fresh tube and was then spun at 2,600 rpm for an additional 30 min. Phage were precipitated with 20% (vol/vol) solution of 20% (wt/vol) polyethylene glycol 6000 containing 2.5 M NaCl. Phage were then resuspended in 1 ml of water. Approximately 10 μl of phage was used for each dot blot. The phage clone with the random hexamer sequence VFVVNG was selected as described previously (2). The phage MA/CA VSQNYPIVQN was generously provided by Affymax.

(i) HIV-1 PR.

A total of 10 μl of each phage strain (prepared as described above) was incubated in 0.2 M NaCl at pH 6.7 and 37°C for 1 h with two HIV-1 PR concentrations (40 and 160 nM). The control reaction for each dot blot contained no enzyme. Reactions were then transferred to nitrocellulose using a dot blot apparatus, and the 3-E7 antibody epitope was detected using the 3-E7 antibody, anti-mouse secondary antibody, and the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) (2). A loss of signal indicates cleavage (see Fig. 1 for an example).

(ii) FIV PR.

Reaction conditions were the same as the reaction conditions for HIV-1 PR, except for the substitution of FIV PR for HIV-1 PR. The two FIV PR concentrations used were 78 and 156 nM. Each phage cleavage was performed at the same time by all three enzymes under the same conditions and blotted onto the same nitrocellulose to undergo identical processing conditions.

Peptide synthesis and purification.

Peptides were synthesized using methods for Fmoc (9-fluorenylmethoxy carbonyl) peptide synthesis as described previously (1) with the substitution of N-methylpyrolidinone for N,N-dimethylformamide as the coupling solvent. Peptides 1 and 6 and all peptides based on phage substrates were synthesized by The Scripps Research Institute core facility using standard 1-butoxycarbonyl (Boc)-protected amino acid coupling procedures. All peptides were purified on a Vydac C-4 semiprep column using reversed-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) and analyzed by mass spectrometry. The gradient for purification was 0 to 70% acetonitrile over 50 min.

Peptide cleavage kinetics.

The cleavage of the peptide Ac-KSGVF↓VVNGK-NH2 (where “Ac” stands for acetyl) was analyzed by assuming Michaelis-Menten kinetics and fitting all data to the Henry-Michaelis-Menten equation using Kaleidagraph (see Table 5). Peptides were cleaved for 30 min at pH 6.7 in 0.2 M NaCl and 0.1 M MES by using either 78 nM HIV-1 PR or 156 nM FIV PR. The reaction mixtures were terminated by the addition of 2 μl of trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) to the reaction mixture. Products were subjected to HPLC, and the product concentration was determined by comparison to a standard.

TABLE 5.

Kinetics of cleavage of Ac-KSGVFVVNGK-NH2 with HIV-1 PR and FIV PRa

| PR type | Mean Km (μM) ± SD | Mean kcat (s−1) ± SD | Mean kcat/Km (μM−1 s−1) (10−4) ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| FIV | 2,100 ± 300 | 0.70 ± 0.08 | 3.4 ± 0.8 |

| HIV-1 | 420 ± 40 | 0.35 ± 0.02 | 8 ± 1 |

Peptide cleavage kinetics of HIV-1 PR and FIV PR cleavage of Ac-KSGVF↓VVNGK-NH2 at pH 6.7 in 0.2 M NaCl and 0.1 M MES are shown. Errors are shown as 1 standard deviation of the data from three trials.

Cleavage of fluorescent substrates designed for HIV-1 PR, Abz-Thr-Ile-Nle↓Phe(NO2)-Gln-Arg-NH2 (26), and FIV PR, NH2-Arg-Ala-Leu-Thr-Lys(Abz)-Val-Gln↓Phe(NO2)-Val-Gln-Ser-Lys-Gly-Arg-NH2 (9), was assessed at pH 5.6 in 0.2 M NaCl–0.1 M MES at 37°C. FIV PR at 368 nM or HIV-1 PR at 297 nM was used in the reactions (see Table 2). The cleavage of substrates was monitored at an excitation wavelength of 320 nm and an emission wavelength of 420 nm. The cleavage sites were verified by HPLC-mass spectrometry.

TABLE 2.

Cleavage of fluorescent substrates designed for HIV-1 PR and FIV PRa

| PR | Substrate | Mean Km (μM) ± SD | Mean kcat (s−1) ± SD | Mean kcat/Km (μM−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-1 | HIV-1b | 2.2 ± 0.7 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 0.4 |

| HIV-1 | FIVc | 8 ± 2 | 0.026 ± 0.006 | 0.003 |

| FIV | FIV | 13 ± 5 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 0.008 |

| FIV | HIV-1 | NDd | ND | NAe |

Cleavage reactions were conducted at pH 5.6 in 0.2 M NaCl–0.1 M MES at 37°C with 368 nM FIV PR or 297 nM HIV-1 PR.

Abz-Thr-Ile-Nle↓Phe(NO2)-Gln-Arg-NH2 (26).

NH2-Arg-Ala-Leu-Thr-Lys-(Abz)-Val-Gln↓Phe-(NO2)-Val-Gln-Ser-Lys-Gly-Arg-NH2 (9).

ND, cleavage of the HIV-1 PR substrate by FIV PR was undetectable after 1 h by fluorescence increase or HPLC.

NA, not applicable.

Peptide cleavage.

All peptide sequences were derived from phage selected as described above. A 500 μM concentration of each peptide was digested with 312 nM FIV PR or 160 nM HIV-1 PR for 2 h at pH 6.7 in 0.2 M NaCl (see Tables 3 and 4). Peptides were subjected to digestion with 78 nM HIV-1 PR and 156 nM FIV PR for 4 h at pH 6.7 in 0.2 M NaCl (see Table 4). All peptides were acetylated at the N terminus, and amides were acetylated at the C terminus. All cleavages were run on 100 μM substrate except cleavages 5, 6, and 7, which were done at 500 μM. All terminated reaction mixtures were analyzed by Vydac C18 reversed-phase analytical HPLC to identify the amount of cleavage product. Cleavage sites were determined by overnight cleavage of each peptide with either HIV-1 PR or FIV PR, and the resulting fragments were analyzed by C18 reversed-phase analytical HPLC, followed by mass spectrometry. All of the peptides tested except Ac-KGSGVYQLSALVPK-NH2 were cleaved in one location. The latter peptide was cleaved at two sites by FIV PR (see Table 3).

TABLE 3.

HIV-1 and FIV PR cleavage of FIV PR selected phage-derived peptidesa

| Peptide | Peptide sequencec | HIV-1 PR cleavageb | FIV PR cleavageb |

|---|---|---|---|

| R3 20 | KGSGVF↓AVTQLVPK | ++ | +++ |

| R2 13 | KGSGIY↓TVQSLVPK | ++ | +++ |

| R1 8 | KGSGLTM↓VTQLVPK | − | +++ |

| R3 21 | KGSGVY↓QL d SALVPK | + | ++, ++d |

| R2 20 | KGSGALTN↓AVLVPK | − | +++ |

| R3 14 | KGSGAMVN↓QALVPK | − | +++ |

| R3 25 | KGSGTW↓MVHSLVPK | − | +++ |

| R3 30 | KGSGGRIN↓VALVPK | + | +++ |

All peptide sequences listed above were derived from phage selected as described in Materials and Methods. A 500 μM concentration of each peptide was digested with 312 nM FIV PR or 160 nM HIV-1 PR for 2 h at pH 6.7 in 0.2 M NaCl.

−, peptide cleavage not detected by HPLC; +, peptide cleavage detected at <5%; ++, peptide cleavage detected at between 10 and 90%; +++, 100% cleavage of the peptide.

Cleavage site for both HIV-1 PR and FIV PR is denoted by an arrow as determined by mass spectrometry of the cleaved fragments.

FIV PR cleaved peptide R3 21 at two sites, the second marked by this footnote reference. None of the starting peptide remained after cleavage, and each product was identified at >20% of the original peptide concentration.

TABLE 4.

Comparison of HIV-1 PR and FIV PR substrate selectivities: cleavage of the peptide series based on the peptide Ac-KSGVFVVNGLVK-NH2a

| Peptide

|

PRb

|

HIV-1 PR/ FIV PRc | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cleavage | Sequenced | FIV | HIV-1 | |

| 1 | KSGVF↓VVNGLVK | ++ | ++ | 0.85 |

| 2 | KSFVF↓VVNGLVK | ++ | ++ | 0.74 |

| 3 | KSGIF↓VVNGLVK | ++++ | ++++ | |

| 4 | KSGNF↓VVN ∗ GLVK | − | +++ | >100 |

| 5 | KSGVN↓VVNGK | − | − | |

| 5b | KSRVN↓VVNGK | + | − | <1/50 |

| 6 | KSGVQ↓VVNGK | − | − | |

| 6b | KSRVQ↓VVNGK | + | − | <1/15 |

| 7 | KSGVF↓HVN ∗ GLVK | ++ | ++++ | |

| 7b | KSGVF↓HVNGK | ++++ | ++++ | |

| 8 | KSGVF↓SVNGLVK | ++++ | + | <1/3.5 |

| 9 | KSGVF↓QVN ∗ GLVK | ++ | ++ | |

| 10 | KSGVF↓VNNGLVK | − | − | |

| 11 | KSGVF↓VENGLVK | + | ++++ | >10 |

| 12 | KSGVF↓VQNGLVK | − | ++++ | >74 |

| 13 | KSGVF↓VVQGLVK | ++++ | ++++ | |

| 14 | KSGVF↓VVTGLVK | ++++ | ++++ | |

Peptides were subjected to digestion with 78 nM HIV-1 PR and 156 nM FIV PR for 4 h at pH 6.7 in 0.2 M NaCl. All peptides were acetylated at the N terminus, and amides were acetylated at the C terminus. All cleavages were run on 100 μM substrate except cleavages 5, 6, and 7, which were cleaved at 500 μM.

++++, 100% cleavage of substrate; +++, >70% cleavage of substrate but <100% cleavage; ++, <70% cleavage but >30% cleavage; +, <30% cleavage; −, no detection of cleavage by HPLC. Quantitation based on cleavage at the arrowed site only.

The ratio of concentration of cleavage product for HIV-1 PR cleavage to the concentration of cleavage product for FIV PR cleavage.

The arrow indicates the scissile bond which was used for the determination of cleavage results. The peptide in italics was the model for identifying differences in specificity between HIV-1 PR and FIV PR. The underlined amino acid is the single amino acid change from the starting peptide sequence (in italics). The asterisk indicates a cleavage at an alternate site by FIV PR. The peptide Ac-KSGNFVVNGK-NH2 (peptide 5) was incubated with FIV PR for 5 h without cleavage.

Inhibitor synthesis.

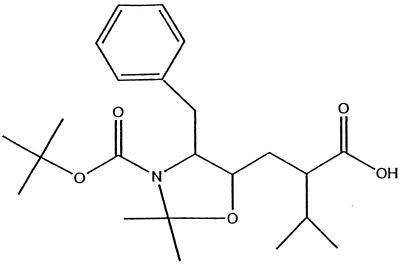

The core structure for JEB hydroxyethylene inhibitor was synthesized using methods described in European Patent Application 90103930.5 (Fig. 2). The fraction containing the S form of the hydroxyl was collected. The carboxy-terminal peptide VNGL for the hydroxyethylene inhibitor was synthesized on MBHA resin using Boc-protected amino acid protocols as described previously (23). The hydoxyethylene core was activated with HOBt and PYBOP and coupled by using standard coupling procedures (see Novabiochem Catalog 2000, p. P2 and P3). The protecting groups on the core were removed by treatment with TFA. The remaining amino acids were sequentially coupled by using the Boc-protected amino acid coupling procedures listed above. The reduced amide inhibitor (RQB) was synthesized as described previously (2). The inhibitors were both purified on a Vydac C18 semiprep column and analyzed by mass spectrometry to identify the mass of the desired product.

FIG. 2.

JEB inhibitor core structure.

Inhibitor kinetics.

The inhibitors were used to compete against cleavage of the fluorogenic substrate Abz-Thr-Ile-Nle-Phe(NO2)-Gln-Arg-NH2 (26) in investigations of wt HIV-1 PR and G48V HIV-1 PR at pH 6.7 in 0.2 M NaCl–0.1 M MES (see Table 6). The Km values for that substrate for HIV-1 PR were determined. We used 7 nM wt HIV-1 PR as determined by active-site titration with inhibitor TL-3. With FIV PR, inhibitors were competed against cleavage of the fluorescent substrate Arg-Ala-Leu-Thr-Lys(Abz)-Val-Gln↓Phe (NO2)-Phe-Val-Gln-Ser-Lys-Gly-Arg-NH2. We used 20 nM FIV PR in the inhibitor assays, as determined by active-site titration with the inhibitor TL-3. Fluorescence was monitored at an excitation wavelength of 320 nm and an emission wavelength of 420 nm on a 96-well fluorimeter. The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) values for each inhibitor were determined in triplicate. The errors are given as the standard deviation of three trials. The IC50 values were converted into Ki values using the following equation: IC50 = Ki (1 + [S]/Km).

TABLE 6.

Kinetics of inhibition of HIV-1 PR, G48V HIV-1 PR, and FIV PRa

| Inhibitor | Mean IC50 ± SD (nM) of:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| HIV-1 PR | FIV PR | |

| JEB [GSGVFΨ(CH2OH)VVNGL] | 160 ± 20 (60) | 5,000 ± 1,000 (3,500) |

| RQB [GSGVFΨ(CH2NH)VVNGL] | 700 ± 200 (262) | 400 ± 100 (287) |

Binding constants for the inhibition of HIV-1 PR and FIV PR by the inhibitors JEB and RQB are shown. Errors are shown as 1 standard deviation of the data from three trials. Nanomolar Ki values are given in parentheses.

PR constructs and purification.

wt HIV-1 PR was constructed, based upon the SF2 strain of HIV-1, and contained the Q7K mutation for autolysis resistance. The PRs were purified as inclusion bodies and refolded in active form, as previously described (15). FIV PR was expressed and purified in active form, as previously described (14).

RESULTS

Although FIV and HIV-1 PRs have markedly similar three-dimensional structures (16), they have quite unique substrate preferences that are reflected in the considerable diversity among the natural cleavage sites within each viral genome (Table 1). Some substrates, such as the matrix-capsid (MA/CA) junction of HIV-1 GAG, are cleaved by both enzymes, but the actual cleavage site is shifted, a finding indicative of distinctions in substrate binding within the S4-S4′ binding pocket of each enzyme (17). Analysis of cleavage by HIV-1 PR of a fluorescent substrate designed for FIV PR [Arg-Ala-Leu-Thr-Lys-(Abz)-Val-Gln↓Phe (NO2)-Phe-Val-Gln-Ser-Lys-Gly-Arg-NH2 (9)] revealed that this substrate is cleaved by HIV-1 PR although >100 times less efficiently than it cleaves an HIV-specific fluorescent substrate (Table 2). The Km for HIV-1 PR on the FIV substrate is only fourfold higher than the Km for cleavage against the HIV-1 substrate. However, the kcat for the cleavage of the FIV substrate is 30-fold lower than for the cleavage of the HIV-1 substrate.

TABLE 1.

Gag and Gag-Pol cleavage sites for HIV-1 and FIV

| Virus | Gag and Gag-Pol cleavage sites

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P4a | P3 | P2 | P1 | P1′b | P2′ | P3′ | P4′ | |

| FIV | ||||||||

| MA/CA | P | Q | A | Y | P | I | Q | T |

| CA/NC1 | K | M | Q | L | L | A | E | A |

| CA/NC2 | T | K | V | Q | V | V | Q | S |

| NC (internal) | V | N | Q | M | Q | Q | A | V |

| NC/PR | G | F | V | N | Y | N | K | V |

| PR/RT | R | L | V | M | A | Q | I | S |

| RT/RNase H | A | E | T | W | Y | I | D | G |

| RNase H/DU | C | Q | T | M | M | I | I | E |

| DU/IN | T | G | V | F | S | S | W | V |

| HIV-1 | ||||||||

| MA/CA | S | Q | N | Y | P | I | V | Q |

| CA/P2 | A | R | V | L | A | E | A | M |

| P2/NC | A | T | I | M | M | Q | R | G |

| P1/P6 | P | Q | N | F | L | Q | S | R |

| in P6 | K | E | L | Y | P | L | T | S |

| TF/PR | S | F | N | F | P | Q | I | T |

| PR/RT | T | L | N | F | P | Q | I | T |

| in RT | A | E | T | F | Y | V | D | G |

| RT/IN | R | K | I | L | F | L | D | G |

Berger and Schechter nomenclature.

Hydrolysis occurs between the P1 and P1′ amino acids.

In order to further define substrate specificity in the absence of factors related to virus maturation, a phage display library was employed to allow for selection of substrates either selectively cleaved by FIV or HIV-1 PR or cleaved by both enzymes. Selection relies on the ability of the PR to cleave the Gene III protein within a random hexamer region engineered into the protein, resulting in the loss of an antibody epitope at the distal end of the protein and facilitating the negative selection of susceptible phage using Staphylococcus protein A (see Materials and Methods). Phage clones from each round of selection were individually screened for cleavage by FIV PR by using the dot blot method initially described by Smith et al. (24), as modified by Beck et al. (2). The random hexamer regions of phage cleaved by FIV PR are displayed in Fig. 1. Those phage, along with phage identified as being efficiently cleaved phage by HIV-1 PR (2), were cleaved in a “rank order” dot blot assay in a side-by-side comparison of HIV-1 and FIV PRs (Fig. 1). The concentration of enzyme used in the digests was standardized with respect to the phage substrate containing the random hexamer region VFVVNG (Fig. 1), which was cleaved similarly by HIV-1 PR and FIV PR. (This phage was selected as described previously [2].) The phage substrate labeled MA/CA VSQNY*PIVQ was constructed based on the amino acid sequence surrounding the MA/CA cleavage site of HIV-1 (Table 1; Fig. 1).

Eight peptides were constructed, based on the amino acid sequences of phage substrates that were cleaved in the FIV PR screens, in order to determine the actual cleavage site in each amino acid sequence and to verify specificity differences for HIV-1 PR and FIV PR (Table 3). Substrates were constructed as Ac-KGSGXXXXXXLVPK-NH2, where X represents any of the commonly occurring amino acids. Three amino acids of the phage fusion were incorporated into either side of the random hexamer region. Lysine was placed at either end of the phage-based peptides in order to increase solubility. Each substrate (500 μM) was digested for 2 h with 160 nM HIV-1 PR or 312 nM FIV PR at pH 6.7 in 0.2 M NaCl–0.1 M MES, the same salt and pH conditions as for the phage digests (Fig. 1). Analysis of the peptide versions of the phage substrates that were cleaved by both HIV-1 PR and FIV PR (Fig. 1)—Ac-KGSGVF↓AVTQLVPK-NH2, Ac-KGSGIY↓TVQSLVPK-NH2, and Ac-KGSGVY↓QL*SALVPK-NH2—revealed that all three were cleaved by both HIV-1 PR and FIV PR at the sites indicated by the arrow. The peptide Ac-KGSGVY↓QL*SALVPK-NH2 was cleaved by HIV-1 PR and FIV PR at the site marked with an arrow. FIV PR also cleaved at the site marked with an asterisk. Consistent with the phage dot blot analysis, the peptides corresponding to phage substrates (Ac-KGSGALTN↓AVLVPK-NH2, Ac-KGSGAMVN↓QALVPK-NH2, and Ac-KGSGGRIN↓VALVPK-NH2; Table 3) were also cleaved relatively efficiently by FIV PR. In addition, the peptide substrates based on phage selected from the FIV PR screen—Ac-KGSGLTM↓VTQLVPK-NH2 and Ac-KGSGTW↓MVHSLVPK-NH2—were cleaved 100% by FIV PR but not at all by HIV-1 PR.

Relative substrate specificities of FIV and HIV-1 PRs.

A set of peptides was designed to determine differences in the substrate specificities of HIV-1 PR and FIV PR (Table 4). The phage substrate containing the hexamer peptide sequence VFVVNG (Fig. 1), as well as peptides modeled after the phage substrate, i.e., Ac-KSGVF↓VVNGLVK-NH2 and Ac-KSGVF↓VVNGK-NH2, were cleaved well by both HIV-1 PR and FIV PR. The Km and kcat values for cleavage of the peptide Ac-KSGVF↓VVNGK-NH2 for FIV PR were 2,100 μM and 0.7 s−1, respectively (Table 5). The Km and kcat values for cleavage of the same substrate by HIV-1 PR were 420 μM and 0.35 s−1, respectively (Table 5). Single amino acid changes, based on differences between the phage substrates select by HIV-1 PR and FIV PR, were placed into the context of the peptide sequence Ac-KSGVFVVNGLVK-NH2 to determine how each change would affect the relative cleavage rate by each PR (Table 4). A shortened peptide form, Ac-KSGVFVVNGK-NH2, was used in some cases to avoid a second site of cleavage by FIV PR, identified in substrates 4, 7, and 9 (Table 4). The amount of FIV PR and HIV-1 PR used was the concentration required to cleave 100 μM peptide Ac-KSGVFVVNGLVK-NH2 at approximately the same rate (the ratio of HIV-1 PR cleavage product to FIV PR cleavage product was 0.85).

The findings show that specific changes eliminated or markedly reduced the cleavage of the peptides by FIV PR under the conditions tested (Table 4). These changes include the substitution of Asn at P2 (peptide 4), Asn at P1 in the context of Gly at P3 (peptide 5), Gln at P1 in the context of Gly at P3 (peptide 6), Glu at P2′ (peptide 11), Gln at P2′ (peptide 12), or Asn at P2′ (peptide 10). In contrast, substitution of Asn at P1 (peptides 5 and 5b), Gln at P1 (peptides 6 and 6b), or Asn at P2′ (peptide 10) abolished all cleavage by HIV-1 PR. Enhancement of cleavage was seen for both PRs after the substitution of Ile at P2 (peptide 3), His at P1′ (peptide 7b), Qln at P3′ (peptide 13), or Thr at P3′ (peptide 14), relative to cleavage of peptide 1.

Substitution of Ser at P1′ (Table 2, peptide 8) resulted in <30% cleavage by HIV-1 PR, whereas 100% cleavage was observed with FIV PR. The substitution of Asn (peptide 5) or Gln at the P1 position (peptide 6) resulted in abolition of cleavage by FIV PR. However, three of the phage substrates efficiently cleaved by FIV PR that were not cleaved by HIV-1 PR (R2-20, R3-14, and R3-30; see Table 3) contained Asn at the P1 position. Upon inspection, it was noted that the phage substrates that were cleaved by FIV PR all contained amino acids at P3′ that were larger (Leu, Met, and Arg) than the Gly contained at the P3 position of peptide 5. In addition, the fluorescent substrate Arg-Ala-Leu-Thr-Lys (Abz)-Val-Gln↓Phe-(NO2)-Gln-Arg-NH2 and the CA/NC2 cleavage site of FIV (Thr-Lys-Val-Gln↓Val-Val-Gln-Ser) contain Gln at the P1 position, but they also contain large P3 residues (underlined).

Peptides 5a (Arg P3, Asn P1) and 5b (Arg P3, Gln P1) were synthesized with Arg at the P3 position to determine whether cleavage could be restored for these peptides by insertion of a larger P3 residue. FIV PR cleaved peptides 5a and 5b, but cleavage was not detected for HIV-1 PR. FIV PR cleaved peptide 5a with an excess of 50-fold more product than the HIV-1 PR cleavage, and FIV PR cleaved peptide 5b with an excess of 15-fold more product than the HIV-1 PR cleavage.

Substitution of Asn at P2 (peptide 4), Glu at P2′ (peptide 11), or Gln at P2′ (peptide 12) resulted in an increase in the cleavage rate for HIV-1 PR. However, those substitutions resulted in either a complete loss of cleavage or a drastic reduction in rate of cleavage for FIV PR. A summary of the cleavage specificities for all phage and peptide substrates is shown in Table 7.

TABLE 7.

Summary of phage and peptide substratesa

| Substrate | HIV-1 PR only | FIV PR only | Both HIV-1 PR and FIV PR | Neither PRc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phage | GSGIF↓LETSL | GALTN↓AVLVP | GSGIY↓TVQSL | |

| GSGVF↓VETSL | SGRIN↓VALVP | GSGVF↓VVNGL | ||

| GSGVF↓VEMPL | GAMVN↓QALVP | GSGVY↓HVSTL | ||

| GSGIM↓FESNL | SGVAL/SALVP | GSGVF↓AVTQL | ||

| GSGLF↓TEYGL | GSGVF/YTLVP | |||

| GSGVH↓VEYTL | GSGVY↓QL↓SAL | |||

| GSGNY↓FVETL | ||||

| GSGNY↓FVQGL | ||||

| GSGNY↓LVTSL | ||||

| VSQNY↓PIVQL | ||||

| GSGVY↓LATDL | ||||

| Peptideb | KSGNF↓VVNGLVK | KSGNFVVN↓GLVK | KSGVF↓VVNGLVK | KSGVN / VVNGK |

| KSGVF↓VENGLVK | KSGVF↓SVNGK | KSFVF↓VVNGLVK | KSGVQ / VVNGK | |

| KSGVF↓VQNGLVK | KSGVFHVN↓GLVK | KSGIF↓VVNGLVK | KSGVF / VNNGLVK | |

| KSGVFQVN↓GLVK | KSGVF↓HVNGK | |||

| KSGVF↓QVNGLVK | ||||

| KSGVF↓VVQGLVK | ||||

| KSGVF↓VVTGLVK |

Phage substrates were divided into the categories listed above based on an analysis of Fig. 1.

Peptide substrates were only listed in columns if at least a 100 μM concentration of the substrate was cleaved better than 30% under the conditions listed in Materials and Methods and in Table 2.

Products of the cleavage of substrates listed in the neither PR column were not detected at all.

Inhibitor studies.

The peptide Ac-GSGVF↓VVNGL-NH2 also served as the basis for design of two inhibitors. Care was taken to introduce transition state analogues that did not extend the C-α backbone of the inhibitor, compared to the peptide, and only l-amino acids were used. The incorporation of a reduced amide at the scissile bond resulted in the inhibitor RQB [Ac-GSGVFΨ(CH2NH)VVNGL-NH2]. However, the reduced amide transition state analogue has not served as the best type of transition state analogue in previous studies of HIV-1 PR (25). Therefore, the scissile bond was also replaced with a hydroxyethylene transition state analogue (as contained in ritonavir) for the design of inhibitor JEB [GSGVFΨ(CH2OH)VVNGL-NH2].

The results for the IC50 of each inhibitor with HIV-1 PR and FIV PR are listed in Table 6. The IC50 for wt HIV-1 PR decreased when the reduced amide transition state analogue was replaced by the hydroxyethylene transition state analogue. The Ki and IC50 values for FIV PR increased 12-fold upon switching from the reduced amide transition state analogue to the hydroxyethylene transition state analogue. The Ki values for the reduced amide inhibitor were approximately within a standard deviation for HIV-1 PR and FIV PR.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, phage-displayed hexapeptide substrates were identified that were preferentially cleaved by HIV-1 PR, FIV PR, or both PRs similarly. In order to investigate single amino acid changes that dictate selectivity differences for these two PRs, single amino acid changes were substituted into the peptide substrate Ac-KSGVFVVNGLVK-NH2, a substrate efficiently cleaved by both PRs. A summary of the phage substrates cleaved by FIV PR, HIV-1 PR, or both PRs (Table 7) revealed that failure of FIV PR to cleave most of the HIV-1 PR-only phage substrates can be explained by the presence of Asn at P2 and Glu at P2′. Consistent with the phage selection results, when Asn was substituted in the P2 position (peptide 4) of the peptide Ac-KSGVFVVNGLVK-NH2, HIV-1 PR cleaved the substrate much faster than FIV PR (Table 4). Likewise, when Glu (peptide 11) or Gln (peptide 12) was substituted at the P2′ position, HIV-1 PR cleaved the substrates faster than did FIV PR.

The cleavage site of most of the phage peptide substrates includes the phage fusion peptide Gly-Ser-Gly from the P5-P3 positions. Previous studies have shown that glycine is not a preferred P3 amino acid (3). Of the 20 commonly occurring amino acids, glycine substitution at the P3 position of a peptide based on the matrix-capsid cleavage site of HIV-1 (S-X-N-Y↓P-I-V) is the 15th most efficiently cleaved substrate of the 20 substrates that can be generated (3). However, the difference in kcat/Km between the substrate containing Gly at the P3 position and the most efficiently cleaved substrate in that series was only fivefold (3). In a similar study, when Ser was substituted into the P4 position of a peptide based on the MA/CA cleavage site of HIV-1, the most efficiently cleaved substrate was the Ser-containing peptide (28). Therefore, the tolerance of Gly at the P3 position is probably due to the preference of Ser at the P4 position. The presence of Ser at P4 and Gly at P3 may bias the preference of the other subsites of HIV-1 PR and FIV PR. From the few substrates that were selected that do not contain the phage fusion peptide from the P5-P3 amino acids (Table 3), one can learn something about the preferences of the S4 and S3 subsites. Phage peptide substrates that contained Asn at P1 all contained nonfusion amino acids at the P4 and P3 positions. That is, the P4 and P3 amino acids were part of the random hexamer and all contained a large amino acid at the P3 position (Leu, Met, or Arg) and a small amino acid at the P4 position (Ala or Gly). As noted below, this may indicate the necessity of either small amino acids at the P4 position, large amino acids at the P3 position, or both, in the context of Asn at the P1 position.

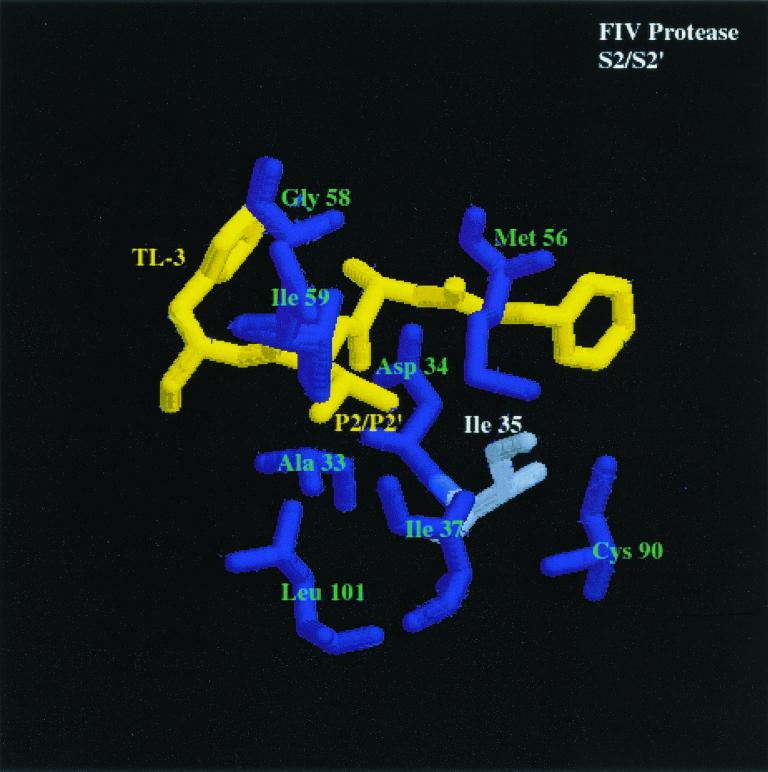

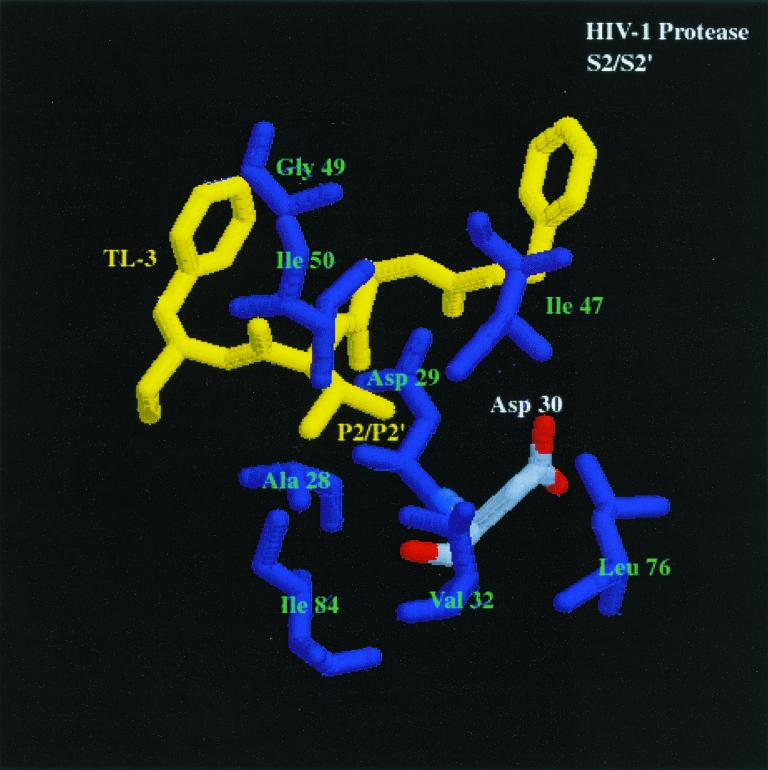

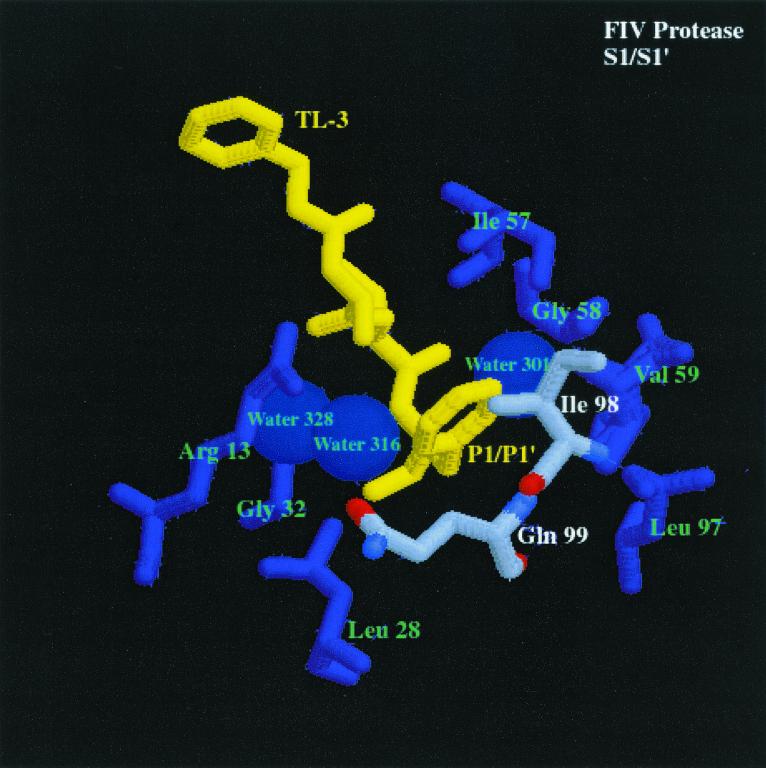

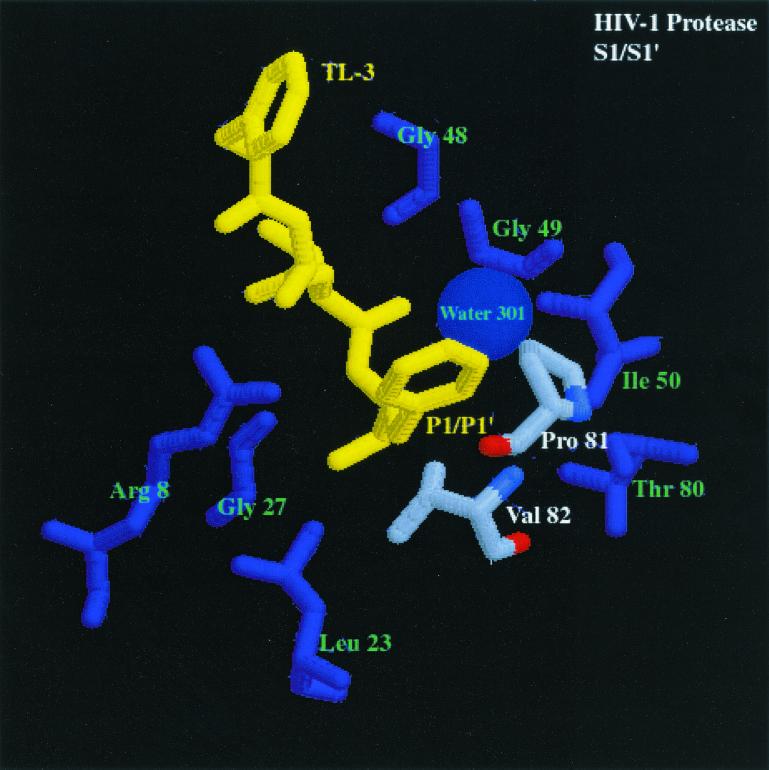

How do the enzymes distinguish between substrates? The cocrystal structures of HIV-1 and FIV PR bound to the dihydroxyl-containing inhibitor TL-3 have been determined (16). Analysis of these structures yields an explanation for the differences between the specificities of FIV PR and HIV-1 PR (Fig. 3, first and second panels) at the S2 and S2′ subsites. The S2 and S2′ pockets of both HIV-1 PR and FIV PR contain amino acids with mostly hydrophobic side chains. FIV PR amino acids Ala-33 (HIV-1 PR Ala-28), Asp-34 (HIV-1 PR Asp-29), Ile-35 (HIV-1 PR Asp-30), Ile-37 (HIV-1 PR Val-32), Met-56 (HIV-1 PR Ile-47), Ile-59 (HIV-1 PR Ile-50), and Leu-101 (HIV-1 PR Ile-84) make up the S2 and S2′ pockets. FIV PR Ile-35 (HIV-1 PR Asp-30) may be the cornerstone of substrate and inhibitor specificity of the P2 and P2′ pockets. As previously noted (6), HIV-1 PR has a preference for Glu and Gln at the P2′ position, based on favorable H-bonding of the side chains of Glu and Gln to residues Asp-29 and Asp-30 of HIV-1 PR. In addition, the crystal structure of saquinavir bound to HIV-1 PR (21a) reveals that the Asn side chain of the inhibitor, located in the S2 subsite, is within 3.5 Å of Asp-30, which is a favorable distance for H bonding. Another important difference between FIV PR and HIV-1 PR is that the S2 and S2′ pockets are smaller in FIV PR, which could contribute to a specificity preference for smaller amino acids in the substrate or inhibitor at the corresponding P2 and P2′ positions.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of the S2/S2′ and S1/S1′ subsites of HIV-1 PR and FIV PR bound to the dihydroxyl-containing inhibitor TL-3 (yellow) (pdb file TL3H for HIV-1 PR and pdb file 1b11 for FIV PR). The first panel shows S2/S2′ subsites of FIV PR bound to TL-3. Residues composing the S2/S2′ pocket are labeled in green and white, and the corresponding residues are enlarged. The differences highlighted between FIV PR and HIV-1 PR (shown in the second panel), bound to TL-3 with structurally homologous amino acids highlighted similar to FIV PR, are residues Ile-35 (FIV PR)/Asp-30 (HIV-1 PR). The differences in Ile-35 (FIV PR) and structurally homologous Asp-30 (HIV-1 PR) may create the ability for HIV-1 PR to cleave substrates with Asn at the P2 position and with Glu or Gln at the P2′ position at a higher rate than FIV PR cleaves the same substrates. In the third panel, S1/S1′ subsite of FIV PR bound to TL-3. Residues composing the S1/S1′ pocket are labeled in green and white, and the corresponding residues are enlarged. The highlighted amino acids in the binding pockets of FIV PR and HIV-1 PR (shown in the fourth panel), bound to TL-3 with the structurally homologous amino acids to FIV PR highlighted in the same fashion as FIV PR, are residues Ile-98 (FIV PR)/Pro-81 (HIV-1 PR) and Gln-99 (FIV PR)/Val-82 (HIV-1 PR) (oxygen, red; nitrogen, blue; carbon, gray). The difference in the charge and structure of these residues is proposed to create the ability of FIV PR to cleave substrates with Asn and Gln in the S1 pocket and Ser in the S1′ pocket better than HIV-1 PR.

For peptides listed in Table 4 that contained Asn substituted at the P2 position (peptide 4), Gln substituted at the P1′ position (peptide 9), or His substituted at the P1′ position (peptide 7), FIV PR cleaved at a site other than the expected cleavage site [i.e., Ac-KSG(N)F↓(Q/H)VN*GLVK-NH2, where the arrow indicates the expected site of cleavage and the asterisk denotes FIV PR cleavage]. The phage-based substrates Ac-KGSGALTN↓AVLVPK-NH2, Ac-KGSGAMVN↓QALVPK-NH2, and Ac-KGSGRIN↓VALVPK-NH2 (the arrow represents confirmed cleavage by FIV PR) all contained amino acids at the P3-P3′ positions that were found in natural substrates of HIV-1 PR, with the exception of Asn at P1. Therefore, it is likely that Asn at the P1 position confers selectivity for FIV PR over HIV-1 PR. However, when Asn was substituted into the P1 position of the peptide series represented in Table 4, i.e., KSGVN↓VVNGK (peptide 5), there was no cleavage by either FIV PR or HIV-1 PR under the conditions tested. When the relatively large amino acid Arg was substituted for Gly at the P3 site (peptide 5b, Table 4), cleavage was restored for FIV PR, but there was still no detectable cleavage by HIV-1 PR. Therefore, the ability of FIV PR to cleave substrates with Asn at P1 is dependent on the amino acid residue in the P3 position. Context dependence of substrate specificity has not been shown for FIV PR, but it has been identified in several studies related to HIV-1 PR substrate specificity (11, 20, 21, 27, 29).

Peptides 8, 5b, and 6b (Table 4) were all cleaved to a greater extent by FIV PR than HIV-1 PR. Analysis of the sequences revealed that all contain polar P1 and P1′ residues. Inspection of the cocrystal structure of FIV PR complexed with the inhibitor TL-3 (Fig. 3, third panel) reveals a more hydrophilic environment at the S1 and S1′ subsites than observed for the S1 and S1′ subsites of HIV-1 PR complexed with TL-3 (Fig. 3, fourth). Three waters in the FIV PR structure are within 5 Å of the Phe side chain at the P1 position. Only one water is within 5 Å of the Phe side chain in the HIV-1 PR structure. The structurally homologous amino acid in FIV PR is Gln-99, which can act as a potential hydrogen-bond donor or acceptor for the side chain of polar residues in the P1 position.

The flexibility of the side chains Ile-98 and Gln-99 may allow FIV PR to tolerate either hydrophobic or hydrophilic residues at the P1 position (Fig. 3, third panel). In the TL-3-bound structure of FIV PR, the Gln side chain is pointing away from the Phe at P1, whereas the Ile-98 side chain is within 4.5 Å of the Phe side chain. With a polar side chain at the P1 position, Gln-99 has the potential to swing toward the P1 amino acid to make H-bond contacts, while Ile-98 has the flexibility to change conformation to create more space at the S1 pocket. The structurally homologous amino acids to Ile-98 and Gln-99 in FIV PR are Pro-81 and Val-82 in HIV-1 PR. The Q99V mutant of FIV PR has been constructed and purified and the peptide substrate Ac-KGSGRIN↓VALVPK-NH2 was cleaved by the Q99V at a lower rate than the wt FIV PR (unpublished data). In addition, the substrates Ac-KSRVN↓VVNGK-NH2 and Ac-KSRVQ↓VVNGK-NH2 were cleaved more efficiently by wt FIV PR than by the Q99V FIV PR mutant, and the control substrate Ac-KSRVF↓VVNGK-NH2 was cleaved with approximately the same efficiency by both the Q99V mutant of FIV PR and wt FIV PR, supporting the hypothesis that Gln-99 aids in the binding of polar residues in the S1 pocket of FIV PR. In addition, major determinants for P1 substrate specificity for Rous sarcoma virus (RSV) PR have been identified as the amino acids Arg-105 and Gly-106, which are structurally homologous to positions Pro-81 and Val-82 in HIV-1 PR (Fig. 3, fourth panel) and Ile-98 and Gln-99 in FIV PR (12). Conversion of residues Arg-105 and Gly-106 of RSV PR to residues corresponding to the structurally homologous amino acids Pro-81 and Val-82 of HIV-1 PR changes the specificity of the RSV PR to be more like HIV-1 PR (12). In a similar study, myeloblastosis-associated virus PR amino acids Arg-105 (HIV-1 PR Pro-81) and Gly-106 (HIV-1 PR Val-82) were converted to the corresponding HIV-1 PR amino acids, along with three other mutations. These changes resulted in a shift in the specificity of the mutant PR to more closely resemble HIV-1 PR specificity (13).

Based on the present study, two of the major determinants of differential specificities between HIV-1 PR and FIV PR appear to be a combination of FIV PR Ile-98 (HIV-1 PR Pro-81) and FIV PR Gln- 99 (HIV-1 PR Val-82) for the S1/S1′ subsites (Fig. 3, third and fourth panels) and FIV PR Ile-35 (HIV-1 PR Asp-30) for the S2/S2′ subsites (Fig. 3, first and second panels). Importantly, these residues are often found in mutant PRs obtained from viruses broadly resistant to anti-PR drugs. Residue 82 of HIV-1 PR can mutate from Val to Ala, Phe, Thr, Ser, or Ile in response to Food and Drug Administration-approved inhibitors, including saquinavir, ritonavir, and indinavir (22). The mutation of V82A has been noted as the first mutation in the evolution of resistance to the inhibitor TL-3 (Buhler et al., unpublished). Surprisingly, all of the drugs approved for clinical use (indinavir, nelfinavir, ritonavir, saquinavir, and amprenavir) contain either a Phe side chain at the P1 or P1′ position or another moiety of the same or a larger size. The presence of large P1 and P1′ residues in the current drugs on the market may dictate a common pathway of resistance. Perhaps development of inhibitors with smaller and/or more flexible moieties at the P1 and P1′ positions will lead to a different class of inhibitors capable of better inhibiting drug-resistant mutants with alterations at Val-82.

Analysis of the natural substrates of FIV PR (Table 1) reveals that Gln is located at the P2′ position of two of the natural substrates (NC [internal] and PR/RT) and Asn is located at the P2′ position of one of the substrates (NC/PR). In this study, FIV PR was shown to prefer the nonpolar amino acid Val more than Gln or Glu at the P2′ position, relative to HIV-1 PR. In addition, two natural substrates contain Gln at the P2 position (CA/NC1 and NC [internal]). However, these data are not in conflict with the findings. There is a range of cleavage efficiency for the natural substrates of HIV-1 PR that may be necessary for proper viral maturation (10, 19). The cleavage efficiencies of the FIV PR substrates also vary. Preliminary analysis of relative cleavage rates of the peptide models of the natural substrates with FIV PR revealed that the substrates described above are less efficiently cleaved than peptide models of the DU/IN and CA/NC2 natural substrates of FIV PR (unpublished data) and therefore are not optimized for the most efficient cleavage. In addition, the context dependence of the substrate amino acids has been known to influence the PR substrate preference, and it is likely that the natural substrates contain amino acids that are complementary to one another.

We have been successful at generating both hydroxyethylene-based and reduced amide-based inhibitors. The analysis of the two inhibitors synthesized elucidated some potentially interesting differences between HIV-1 PR and FIV PR. The substrate GSGVF↓VVNGL was used as the basis for inhibitor design. The similar Ki values for HIV-1 PR and FIV PR binding of the reduced amide inhibitor are not surprising because the kcat/Km values for HIV-1 PR and FIV PR cleavage of the related peptide Ac-KSGVF↓VVNGK-NH2 are within threefold of one another (Table 5). However, when the hydroxyethylene transition state analogue was inserted in place of the scissile amide bond, the inhibitor bound HIV-1 PR with a Ki ca. 12 times lower than the Ki for FIV PR (Table 6). Chemically, the major difference between the two inhibitors is the presence of the secondary amine near the P1′ position in the reduced amide inhibitor and the presence of the S-hydroxyl in the inhibitor containing the hydroxyethylene transition state analogue. The nitrogen in the reduced amide inhibitor could potentially hold a positive charge at neutral pH (30). The polar nature of the S1′ pocket of FIV PR may facilitate better binding in that case. The reduced binding affinity of the hydroxyethylene transition state analogue inhibitor for FIV PR may be due to differences in the geometry of the molecules in the active site of HIV-1 PR and FIV PR, with the attacking water taking a slightly different geometry in its attack on the carbonyl carbon in the two PRs. Alternatively, the hydroxyl may be positioned in a direction that is not favorable for H bonding to other molecules within the binding pocket of FIV PR.

When Ile is substituted at P2, His is substituted at P1′, Gln is substituted at P3′, or Thr is substituted at P3′ in the context of the peptide Ac-KSGVFVVNGLVK-NH2, the resulting rates of cleavage for the peptides increased for both HIV-1 PR and FIV PR. Further studies may include substitution of these amino acids into the framework of the reduced amide inhibitor to increase potency for both HIV-1 PR and FIV PR. In addition, the substitution of different transition state analogues into the backbone may result in tighter binding. The best transition state analogues for HIV-1 PR and FIV PR binding have been the dihydroxyl and the allophenylnorstatine transition state analogues (15; V. D. Le, Mak, L.Y.-C. Chi Ching, J. H. Elder, and C.-H. Wong, unpublished data). However, use of these transition state analogues will result in a slight alteration of the backbone of the inhibitors. With the dihydroxyl synthesis methods used thus far, one may only synthesize C2 symmetric inhibitors. The C2 symmetry excludes making the direct conversion of the asymmetric substrates selected in this study into inhibitors. The allophenylnorstatine extends the backbone by an additional single bond. In addition, the allophenylnorstatine contains a proline analogue at the P1′ position, which means that one may not substitute any other amino acid into that position.

We have identified substrates that are cleaved well by both HIV-1 PR and FIV PR in addition to substrates that are only cleaved by HIV-1 PR or FIV PR. Determining the molecular basis for the specificities of PRs is required in the design of inhibitors for these PRs. The information generated is relevant to broad-based inhibitor design and gives insight into the basis for HIV-1 PR drug-resistant mutants. The specificities identified will aid in our design of tighter-binding inhibitors for HIV-1 PR and FIV PR. With an inhibitor with dual efficacy for both lentiviruses, one may use the feline-FIV system to test inhibitors prior to testing them in humans.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Edwin Madison of Corvas for guidance in phage display methodologies; Van-Duc Le of The Scripps Research Institute for synthesis of the JEB core structure; Douglas Daniels for computational assistance and valuable discussions; Garrett Morris for assistance with graphics; Phillip Dawson, John Offer, Benjamin Cravatt, Carlos Barbas, Bruce Torbett, and Arthur Olson for assistance with laboratory equipment and valuable discussions; and Jackie Wold for administrative assistance.

This work was partially supported by grants R01 40882 (J.H.E.) and P01 GM48870 (J.H.E.) from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alewood P, Alewood D, Miranda L, Love S, Meutermans W, Wilson D. Rapid in situ neutralization protocols for Boc and Fmoc solid-phase chemistries. Methods Enzymol. 1997;289:14–29. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)89041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beck Z Q, Hervio L, Dawson P E, Elder J H, Madison E L. Identification of efficiently cleaved substrates for HIV-1 protease using a phage display library and use in inhibitor development. Virology. 2000;274:391–401. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Billich A, Winkler G. Analysis of subsite preferences of HIV-1 proteinase using MA/CA junction peptides substituted at the P3–P1′ positions. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1991;290:186–190. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(91)90606-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doyon L, Croteau G, Thibeault D, Poulin F, Pilote L, Lamarre D. Second locus involved in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 resistance to protease inhibitors. J Virol. 1996;70:3763–3769. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3763-3769.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doyon L, Payant C, Brakier-Gingras L, Lamarre D. Novel Gag-Pol frameshift site in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants resistant to protease inhibitors. J Virol. 1998;72:6146–6150. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.6146-6150.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunn B M, Gustchina A, Wlodawer A, Kay J. Subsite preferences of retroviral proteinases. Methods Enzymol. 1994;241:254–278. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)41068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunn B M, Pennington M W, Frase D C, Nash K. Comparison of inhibitor binding to feline and human immunodeficiency virus proteases: structure-based drug design and the resistance problem. Biopolymers. 1999;51:69–77. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(1999)51:1<69::AID-BIP8>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erickson J W, Burt S K. Structural mechanisms of HIV drug resistance. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1996;36:545–571. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.36.040196.002553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fitzgerald M C, Laco G S, Elder J H, Kent S B. A continuous fluorometric assay for the feline immunodeficiency virus protease. Anal Biochem. 1997;254:226–230. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gowda S D, Stein B S, Engleman E G. Identification of protein intermediates in the processing of the p55 HIV-1 gag precursor in cells infected with recombinant vaccinia virus. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:8459–8462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griffiths J T, Phylip L H, Konvalinka J, Strop P, Gustchina A, Wlodawer A, Davenport R J, Briggs R, Dunn B M, Kay J. Different requirements for productive interaction between the active site of HIV-1 proteinase and substrates containing -hydrophobic*hydrophobic- or -aromatic*pro- cleavage sites. Biochemistry. 1992;31:5193–5200. doi: 10.1021/bi00137a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grinde B, Cameron C E, Leis J, Weber I T, Wlodawer A, Burstein H, Bizub D, Skalka A M. Mutations that alter the activity of the Rous sarcoma virus protease. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:9481–9490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Konvalinka J, Horejsi M, Andreansky M, Novek P, Pichova I, Blaha I, Fabry M, Sedlacek J, Foundling S, Strop P. An engineered retroviral proteinase from myeloblastosis associated virus acquires pH dependence and substrate specificity of the HIV-1 proteinase. EMBO J. 1992;11:1141–1144. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05154.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laco G S, Fitzgerald M C, Morris G M, Olson A J, Kent S B, Elder J H. Molecular analysis of the feline immunodeficiency virus protease: generation of a novel form of the protease by autoproteolysis and construction of cleavage-resistant proteases. J Virol. 1997;71:5505–5511. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5505-5511.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee T, Laco G S, Torbett B E, Fox H S, Lerner D L, Elder J H, Wong C H. Analysis of the S3 and S3′ subsite specificities of feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) protease: development of a broad-based protease inhibitor efficacious against FIV, SIV, and HIV in vitro and ex vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:939–944. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li M, Morris G M, Lee T, Laco G S, Wong C H, Olson A J, Elder J H, Wlodawer A, Gustchina A. Structural studies of FIV and HIV-1 proteases complexed with an efficient inhibitor of FIV protease. Proteins. 2000;38:29–40. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(20000101)38:1<29::aid-prot4>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin Y C, Beck Z, Lee T, Le V D, Morris G M, Olson A J, Wong C H, Elder J H. Alteration of substrate and inhibitor specificity of feline immunodeficiency virus protease. J Virol. 2000;74:4710–4720. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.10.4710-4720.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mammano F, Petit C, Clavel F. Resistance-associated loss of viral fitness in human immunodeficiency virus type 1: phenotypic analysis of protease and gag coevolution in protease inhibitor-treated patients. J Virol. 1998;72:7632–7637. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7632-7637.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mervis R J, Ahmad N, Lillehoj E P, Raum M G, Salazar F H, Chan H W, Venkatesan S. The gag gene products of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: alignment within the gag open reading frame, identification of posttranslational modifications, and evidence for alternative gag precursors. J Virol. 1988;62:3993–4002. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.11.3993-4002.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pettit S C, Simsic J, Loeb D D, Everitt L, Hutchison C A D, Swanstrom R. Analysis of retroviral protease cleavage sites reveals two types of cleavage sites and the structural requirements of the P1 amino acid. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:14539–14547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ridky T W, Cameron C E, Cameron J, Leis J, Copeland T, Wlodawer A, Weber I T, Harrison R W. Human immunodeficiency virus, type 1 protease substrate specificity is limited by interactions between substrate amino acids bound in adjacent enzyme subsites. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:4709–4717. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.9.4709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21a.Roberts N A, Martin J A, Kinchington D, Broadhurst A V, Craig J C, Duncan I B, Galpin S A, Handa B K, Kay J, Krohn A. Rational design of peptide-based HIV proteinase inhibitors. Science. 1990;248:358–361. doi: 10.1126/science.2183354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21b.Schechter I, Berger A. On the size of the active site in proteases. I. Papain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1967;27:157–162. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(67)80055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schinazi R F, Larder B A, Mellors J W. Mutations in retroviral genes associated with drug resistance. Int Antiviral News. 1997;5:129–142. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schnolzer M, Alewood P, Jones A, Alewood D, Kent S B. In situ neutralization in Boc-chemistry solid phase peptide synthesis. Rapid, high-yield assembly of difficult sequences. Int J Pept Protein Res. 1992;40:180–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1992.tb00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith M M, Shi L, Navre M. Rapid identification of highly active and selective substrates for stromelysin and matrilysin using bacteriophage peptide display libraries. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:6440–6449. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.12.6440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tomasselli A G, Olsen M K, Hui J O, Staples D J, Sawyer T K, Heinrikson R L, Tomich C S. Substrate analogue inhibition and active site titration of purified recombinant HIV-1 protease. Biochemistry. 1990;29:264–269. doi: 10.1021/bi00453a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Toth M V, Marshall G R. A simple, continuous fluorometric assay for HIV protease. Int J Pept Protein Res. 1990;36:544–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1990.tb00994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tozser J, Bagossi P, Weber I T, Louis J M, Copeland T D, Oroszlan S. Studies on the symmetry and sequence context dependence of the HIV-1 proteinase specificity. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16807–16814. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.27.16807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tozser J, Gustchina A, Weber I T, Blaha I, Wondrak E M, Oroszlan S. Studies on the role of the S4 substrate binding site of HIV proteinases. FEBS Lett. 1991;279:356–360. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80186-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tozser J, Weber I T, Gustchina A, Blaha I, Copeland T D, Louis J M, Oroszlan S. Kinetic and modeling studies of S3–S3′ subsites of HIV proteinases. Biochemistry. 1992;31:4793–4800. doi: 10.1021/bi00135a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wlodawer A, Erickson J W. Structure-based inhibitors of HIV-1 protease. Annu Rev Biochem. 1993;62:543–585. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.002551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wlodawer A, Gustchina A, Reshetnikova L, Lubkowski J, Zdanov A, Hui K Y, Angleton E L, Farmerie W G, Goodenow M M, Bhatt D. Structure of an inhibitor complex of the proteinase from feline immunodeficiency virus. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2:480–488. doi: 10.1038/nsb0695-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Y M, Imamichi H, Imamichi T, Lane H C, Falloon J, Vasudevachari M B, Salzman N P. Drug resistance during indinavir therapy is caused by mutations in the protease gene and in its Gag substrate cleavage sites. J Virol. 1997;71:6662–6670. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6662-6670.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]