Abstract

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are associated with an array of intestinal injuries: erosions, ulcers, enteropathy, strictures and diaphragm disease. The diagnosis of diaphragm disease is challenging. Diaphragm disease can cause thin, concentric and stenosing strictures, which can induce intermittent or complete bowel obstruction. NSAID-induced lesions are reversible following discontinuation of the offending agent. Treatment of diaphragm disease can be conservative, endoscopic or surgical through stricturoplasty and/or segmental resection. We report a case of a 59-year-old female presenting with intermittent right lower quadrant pain diagnosed with diaphragm disease upon combined ileo-colonoscopy and histopathological analysis. Her diaphragm disease was successfully treated conservatively through drug cessation, avoiding more invasive procedures like endoscopic and surgical interventions.

LEARNING POINTS

The incidence of diaphragm disease has been soaring due to the widespread use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Diaphragm disease is characterized by diaphragm-like mucosal projections and annular constrictions that induce luminal narrowing and result in bowel obstruction.

Physicians should get acquainted with diaphragm disease and include it in their differential diagnosis when approaching a patient with obstruction-like symptoms or non-specific and vague abdominal pain in the setting of chronic NSAIDs usage.

Keywords: Diaphragm disease, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, subacute bowel obstruction, inflammatory bowel disease, case report

INTRODUCTION

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have grown in popularity, and, in the foreseeable future, their use will continue to increase. NSAIDs are used in inflammatory conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. They are associated with adverse effects, such as inflammation, ulceration, bleeding and perforation[1]. Diaphragm disease is characterized by diaphragm-like mucosal projections causing luminal narrowing of the bowel and inducing obstructive symptoms. Diaphragm disease is more common in middle-aged and elderly patients and it often presents insidiously over many years. It has a preponderance to females with a ratio of 3:1[2]. Diaphragm disease can cause abdominal pain, weight loss, anemia and altered bowel habits. Rarely, it can manifest as a surgical emergency that warrants emergency laparotomy and resection of the affected bowel segment. The diagnosis of diaphragm disease is confirmed histopathologically by the presence of submucosal fibrosis sparing the muscularis propria, serosa and mesentery with absence of granulomata. We describe a case of a 59-year-old female patient diagnosed with diaphragm disease treated conservatively with drug cessation, avoiding invasive endoscopic and surgical interventions.

CASE PRESENTATION

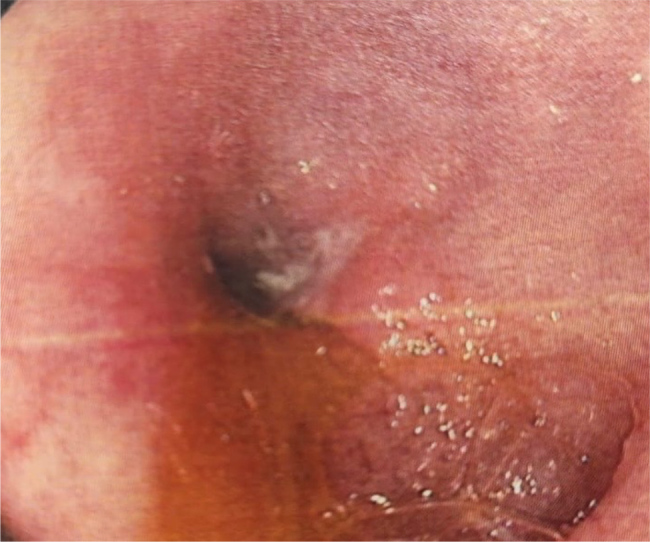

A 59-year-old female presented with a 3-month history of intermittent right lower quadrant pain. The patient had osteoarthritis of the right knee for which she was taking oral celecoxib 200 mg daily preceded by a proton pump inhibitor (PPI). She was on NSAIDs for the past 3 years after she failed non-pharmacologic treatment. She had no history of smoking or alcohol consumption. She described her bouts of right lower quadrant pain as “colicky” in nature. She reported no nausea or vomiting and no changes in bowel habits. Upon physical examination, the patient had right lower quadrant tenderness upon palpation. The remainder of the physical exam was normal. Blood test results, including serum iron and albumin, were unremarkable. Ultrasound of the abdomen was normal. A computed tomography scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed mildly prominent and thickened ileal loops with terminal ileal wall thickening, suggestive of ileitis vs. inflammatory bowel disease. An ileo-colonoscopy was subsequently performed and revealed erythematous mucosa at the level of the terminal ileum with a stenosed lumen through which the colonoscope could not be passed (Fig. 1). Multiple biopsies were taken from the affected segment and sent for histological analysis. The colonic mucosa was unremarkable. Histopathology revealed submucosal fibrosis sparing the muscularis propria, serosa and mesentery with absent granulomata. A diagnosis of diaphragm disease of the terminal ileum was made. Thereafter, celecoxib was discontinued, and the patient was started on duloxetine 30 mg once daily for 1 week. No adverse effects were reported. Therefore, duloxetine was increased to 60 mg once daily. A repeat ileo-colonoscopy was performed 6 months following the diagnosis with diaphragm disease, which was normal. The lumen of the terminal ileum was patent and the colonoscope was advanced effortlessly. Multiple biopsies were taken from the terminal ileum, and they were sent to histopathological analysis which revealed normal findings. Her abdominal pain had resolved. The patient was advised to continue duloxetine and refrain from taking NSAIDs.

Figure 1.

An endoscopic view of the terminal ileum revealing a diaphragm-like stenosing stricture that was not traversable.

DISCUSSION

Diaphragm disease was first described by Lang et al. in 1988[3]. It has been hailed as an uncommon etiology for recurrent subacute bowel obstruction. Diaphragm disease is characterized by thin, circumferential, concentric and stenosing intestinal strictures. Histology demonstrates submucosal fibrosis with increased neutrophils polymorphs, lymphocytes, eosinophils and plasma cells in the affected mucosa[4].

Diaphragm disease-induced stenoses and strictures can present with varying degrees of bowel obstruction.

The pathogenesis of diaphragm disease remains unclear. One plausible theory is that NSAIDs inhibit the secretion of prostaglandins by cyclooxygenase inhibition, which distorts mucosal integrity. This leads to submucosal fibrosis that changes the pliability of the plicae circularis. As a result, the mucosa becomes vulnerable to bacterial products and toxins[3]. NSAIDs compromise villous microcirculation which potentiates the permeability of the intestinal mucosa. This heightened mucosal permeability is further potentiated by the enterohepatic circulation of some drugs. This process draws enteric bacteria and their products and bile to the affected mucosa. Inflammation ensues due to neutrophilic infiltration and endothelial cell injury resulting in the production of reactive oxygen species and tissue damage[5]. Collagenous rings of scar tissue form as a healing process. Over time, these rings can contract forming diaphragm-like strictures[6]. Diaphragm disease can cause iron-deficiency anemia and protein-losing enteropathy by means of NSAIDs-induced mucosal damage. Our patient had neither iron deficiency anemia nor hypoalbuminemia. NSAIDs-induced diaphragm disease is rare. It occurs in around 2% of NSAIDs-damages[7].

It is worth mentioning is that our patient was on a PPI that starkly did not confer protection against mucosal damage to the small intestine. Capsule endoscopy is useful in diagnosing diaphragm disease. However, it is contraindicated in the setting of stenosing strictures due to restricted passage of the capsule, which makes it prone to retention and thus precipitating bowel obstruction. Double-balloon endoscopy aids in the diagnosis of diaphragm disease and double-balloon endoscopy dilatation has proven to be effective in treating diaphragm disease[8]. In case of multiple strictures, laparotomy with stricturoplasty or segmental bowel resection are warranted. Rarely, diaphragm disease can present as a more dramatic scenario in the context of a life-threatening bowel obstruction. Therefore, diaphragm disease should be included in the differential diagnosis when approaching a patient presenting with bowel obstruction.

Our patient did not present with obstructive symptoms; rather, she was complaining of bouts of right lower quadrant pain. An ileo-colonoscopy demonstrated a stenotic terminal ileum that favored a diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease. Histopathology corroborated a diagnosis of diaphragm disease instead of inflammatory bowel disease. Therefore, diaphragm disease can mimic inflammatory bowel disease, thus posing a diagnostic challenge. This case has demonstrated that diaphragm disease is the “great imitator” due to its mimicry of inflammatory bowel disease.

CONCLUSION

NSAIDs-induced small bowel enteropathy is not well-documented in literature. Diaphragm disease is characterized by diaphragm-like mucosal projections and annular constrictions that induce luminal narrowing and result in bowel obstruction. Diaphragm disease often presents insidiously with non-specific symptoms. Rarely, diaphragm disease can manifest as an emergency in a setting of a full-blown bowel obstruction. Physicians should be aware of diaphragm disease and include it in their differential diagnosis when approaching a patient with obstruction-like symptoms or non-specific and vague abdominal pain in the setting of chronic NSAIDs usage.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interests: The Authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Patient Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patients to publish this report in accordance with the journal’s patient consent policy.

REFERENCES

- 1.McNally M, Cretu I. A Curious Case of Intestinal Diaphragm Disease Unmasked by Perforation of a Duodenal Ulcer. Case Rep Med. 2017;2017:5048345. doi: 10.1155/2017/5048345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bennett S, Martin J, Mahler-Araujo B, Gourgiotis S. Diaphragm disease of the terminal ileum presenting as acute small bowel obstruction. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13:e233537. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2019-233537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lang J, Price AB, Levi AJ, Burke M, Gumpel JM, Bjarnason I. Diaphragm disease: pathology of disease of the small intestine induced by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Clin Pathol. 1988;41:516–526. doi: 10.1136/jcp.41.5.516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peacey SR, Walls WD. Steatorrhoea and sub-total villous atrophy complicating mefenamic acid therapy. Br J Clin Pract. 1992;46:211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Petris G, López JI. Histopathology of diaphragm disease of the small intestine: a study of 10 cases from a single institution. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;130:518–525. doi: 10.1309/7DDT5TDVB5C6BNHV. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Y-Z, Sun G, Cai F-C, Yang YS. Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment strategies of gastrointestinal diaphragm disease associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016;2016:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2016/3679741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chernolesskiy A, Lanzon-Miller S, Hill F, Al-Mishlab T, Thway Y. Subacute small bowel obstruction due to diaphragm disease. Clin Med. 2010;10:296–298. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.10-3-296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayashi Y, Yamamoto H, Taguchi H, Sunada K, Miyata T, Yano T, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced small-bowel lesions identified by double-balloon endoscopy: endoscopic features of the lesions and endoscopic treatments for diaphragm disease. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:57–63. doi: 10.1007/s00535-008-2277-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]