Abstract

Existing literature on the resource theory of marital power has focused on the relative resources of spouses and overlooked the resource contributions of spouses’ extended families. We propose an extended resource theory that considers how the comparative resources of a couple’s natal families are directly associated with marital power, net of the comparative resources of the couple. Using data from the China Panel Family Studies, we examine how the relative education of a couple’s respective parents affects the wife’s decision-making power, net of the relative education of the couple. Results suggest that the higher the wife’s parental education relative to her husband’s parental education, the more likely she is to have the final say over household financial decisions. Our study underscores the importance of situating the study of marital power in the extended family context and highlights the significance of social origins and intergenerational exchanges for marital power.

Introduction

The resource theory of marital power (Blood and Wolfe, 1960) has been one of the primary theoretical frameworks for understanding marital power dynamics. The theory posits that the balance of decision-making power depends upon the relative resources each spouse brings into the marriage. Existing research utilizing the resource framework has examined marital power from the perspective of nuclear families and has thus overlooked the wide variety of resources that the extended family, i.e. spouses’ respective natal families, contribute to the marriage (Liu, Hutchison and Hong, 1973; Li, 2010). Parental resources are often integral to the foundation of a new marriage and may affect its power allocation (Brown, 2009). Therefore, marital power may be determined by both the relative resources of spouses and the relative resources of spouses’ parents. In this article, we propose an extended resource theory that situates the discussion of marital power in the extended family context. We argue that the comparative resources of the couple’s natal families are directly associated with marital power, net of the comparative resources of the couple. We apply this theoretical framework to the empirical case of contemporary rural China and examine how the relative education of a couple’s respective parents affects the division of decision-making power, net of the relative education of the couple.

Our study reintroduces a longstanding perspective that considers the importance of parental resources in the study of marital power (Fox, 1973; Liu, Hutchison and Hong, 1973; Katz and Peres, 1985). The prevailing approach considers the power bargain as a negotiation between the two partners (Blood and Wolfe, 1960). Yet, a marriage joins not just two persons but two families of origin (Hu, 2016). From the evolutionary social science perspective (Hughes, 1988; Tanskanen and Danielsbacka, 2018), humans are cooperative breeders. Marriage connects the two families through common descendants, which motivates support exchanges among extended kin. As we will demonstrate in this article, partners’ bases of power consist of both the resources they themselves bring and the resources their parents contribute to the marriage. Our theory reaffirms a commonly accepted wisdom in family research that we need to study marriage not in isolation but in the proper social context within which it takes place (Goode, 1963). In many societies today, nuclear families are embedded in extended families (Helms, 2013). Thus, a fuller understanding of marital power needs to consider the social context of the extended family.

The proposed extended resource theory also contributes to the literature on social stratification, assortative mating, and intergenerational support. In marital exchange, each partner is valued for both their own socioeconomic status and the status of their natal family (Fox, 1973). Therefore, social origin not only matters in the intergenerational transmission of socioeconomic inequality (Brown, 2006) but can also influence marital power. The education of the parents’ generation may have a lingering impact on the marital power of their children’s generation. Furthermore, marital sorting on parental backgrounds is an important process of stratification (Charles, Hurst and Killewald, 2013; Hu, 2016; Schwartz, Zeng and Xie, 2016), but its implications for marital experience are understudied. Cultural practices of assortative mating on social origins may affect marital power dynamics. For example, women marrying husbands from higher status families may be disadvantaged in power negotiations. Finally, intergenerational exchange, downward or upward, has become increasingly common (Bengtson, 2001), partly because life expectancy improvement has increased the mutual exposure of generations (Song and Mare, 2019). Many studies have examined how intergenerational exchange affects older parents’ well-being (Silverstein, Cong and Li, 2006), but less is understood about how it affects adult children’s marital relationships.

We situate our study in the setting of rural Chinese households. The hukou (household registration) system, first established in 1955, distinguishes two types of households, rural/agricultural and urban/non-agricultural, with differential rights and benefits in land, housing, education, employment, medical insurance, and pensions (Wu and Treiman, 2007). Rural households have strong cultural traditions of extended families and high interdependence between generations in land, labour, childcare, and old age support (Chen, 2004; Silverstein, Cong and Li, 2006), providing a unique opportunity to study the influence of the extended family on marital power. Rapid socioeconomic development and new social policies have brought about drastic changes in how extended and nuclear families interact in rural China.

The traditional Chinese family was patriarchal, patrilineal, and patrilocal (Thornton and Lin, 1994). Parents were heavily involved in their sons’ post-marital lives (Greenhalgh, 1985) on the basis of filial piety, i.e. the norm that children, especially sons, should respect and take care of their parents later in life (Whyte, 2004). In contrast, a daughter was merely a temporary member of her natal family before she married into her husband’s family, with no right to inherit parental property and no obligation to support her parents in their old age (Greenhalgh, 1985). After marriage, she was described colloquially as ‘spilled water’ and became an outsider to her natal family (Zhang, 2009). In recent decades, however, parent-daughter relations have grown much stronger in rural China (Zhang, 2009; Gruijters, 2017). Rural married women now maintain more intensive relationships with their natal families, receive more financial, emotional, and childcare support from their parents, and have equal legal rights to inherit parental property (Zhang, 2009; Li, 2010). The growing significance of parent-daughter relationships may be attributed to the changing norms of parent-daughter relationships, women’s empowerment, improved socioeconomic status since the economic reform, reduced family size, and rapid technological advancements (Zhang, 2009; Wu, Ye and He, 2014; Gruijters, 2017). As intergenerational ties become more bilateral in rural China, it is important to consider how the relative resources of the couple’s respective natal families influence their power dynamics.

Furthermore, family backgrounds have a strong influence on marriage formation in rural China. The tradition of ‘marriages of matching doors’, i.e. marriages between families of equal social standing, prevails in contemporary China; individuals tend to marry those from similar socioeconomic family backgrounds (Hu, 2016). Homogamy based on individuals’ own education has significantly increased over time (Dong and Xie, 2023), in tandem with the rapid improvement in women’s education (Treiman, 2013) and higher returns to education since the economic reform (Han, 2010). However, women’s preference for marrying men of higher status persists (Mu and Xie, 2014). Our study thus underscores the implications of the cultural practice of homogamy based on ascribed status and female hypergamy based on achieved status for marital power dynamics.

Theoretical framework

In this section, we will begin with an introduction to the original resource theory of marital power and its limitations in the conceptualization of resources and marital exchanges. Next, we will propose an extended resource theory to address these limitations and discuss the theoretical mechanisms by which the relative resources of a couple’s respective parents affect power dynamics above and beyond the relative resources of the couple themselves. Finally, we will apply the extended resource theory framework to study how relative parental education, as an indicator of relative parental resources, affects marital power above and beyond relative spousal education.

Resource theory of marital power

The resource theory of marital power (Blood and Wolfe, 1960), closely related to social exchange theory (Thibaut and Kelley, 1959; Nye, 1980), posits that the balance of power in marriage is determined by the comparative resources of the two partners.1 Resources are exchanged between spouses (Sabatelli and Shehan, 1993), and the partner with the most resources is more likely to have the final say in household decisions. Within the power-dependence framework (Emerson, 1962), the partner with fewer resources is more dependent on their spouse and thus has less bargaining power. Conversely, the partner with more resources has the greater potential to dominate and change the other partner’s behaviour. Prior studies have found empirical support for the resource theory of marital power in China (Carlsson et al., 2013; Yang and Zheng, 2013; Chien and Yi, 2014; Qian and Jin, 2018; Cheng, 2019).

Partners may exchange various resources to meet each other’s needs. Blood and Wolfe (1960) focused primarily on resources related to socioeconomic status, including individual income, education, and occupational prestige. Social psychological research has emphasized the exchange of informational resources (e.g. knowledge of certain decision domains) and psychological resources (e.g. interpersonal skills) (Foa, 1971; Kulik, 1999). Safilios-Rothschild (1976) further discussed the exchange of resources in the emotional and sexual sphere of marriage, including affective, expressive, and sexual companionship resources. Services, such as the performance of housework and childcare, are also important in marital exchange (Foa, 1971; Safilios-Rothschild, 1976). Household labour may be performed in exchange for economic resources (Brines, 1994; Bittman et al., 2003). Prior research finds that comparative advantages in economic resources tend to increase power over major family decisions (Klesment and Van Bavel, 2022). On the other hand, the partner performing more services, most often the wife, has more control over mundane decisions (Shu, Zhu and Zhang, 2013). The power to make less frequent but important family decisions is construed as orchestration power; those with orchestration power may delegate more time-consuming, mundane decisions to their spouse (Safilios-Rothschild, 1976).

From the resource theory perspective, either spouse can attain more power in marriage by contributing more resources. However, household decision-making is a gender-coded activity (Shu, Zhu and Zhang, 2013). Gender role ideologies are also instrumental in the allocation of decision-making power (Blumberg and Coleman, 1989). The gender display hypothesis argues that gendered normative expectations can override relative resources in organizing marital power relations when the wife contributes significantly more economic resources than the husband (Klesment and Van Bavel, 2022). Couples with reversed gender roles in which the husband is more economically dependent on the wife may maintain male dominance in decision-making to compensate for gender deviance (Tichenor, 2005). However, the empirical evidence of gender display is mixed (Killewald and Gough, 2010; Yu and Xie, 2011; Shu, Zhu and Zhang, 2013; Klesment and Van Bavel, 2022).

The original resource theory of marital power, however, has certain limitations. First, it conceptualizes resources as the partners’ individual resources, i.e. resources stemming from their own attributes. The partners’ parents, however, also make important contributions to a marriage, which are often integral to the foundation of the marriage and affect the allocation of power (Brown, 2009). Second, it conceptualizes marriage as an intimate relationship only involving the two partners. Marital relationships, however, are embedded within extended family relationships (Helms, 2013). A marriage joins not just two partners but also their natal families. The marital power bargain involves negotiations between the two partners as well as their respective natal families.2

Extended resource theory of marital power

We propose an extended resource theory of marital power that incorporates resources contributed by the couple’s respective natal families in the resource exchange: the relative resources of the couple’s respective parents are directly associated with the balance of marital power, net of the relative resources of the couple themselves. The more resources one’s parents have than one’s parents-in-law, the more likely it is that one would have the final say in household decisions. In the extended resource theory framework, a resource may be anything the couple’s parents make available to the couple to satisfy their needs, in addition to anything the couple makes available to each other. Parents provide such resources in the hopes of improving their child’s welfare and enhancing their child’s leverage in marriage. The partner with more parental support than the other is less dependent on the marital relationship and thus has more power in the marriage. Table 1 outlines the major differences between the original resource theory and the proposed extended resource theory in their propositions, conceptualizations, and mechanisms.

Table 1.

Conceptual frameworks of resource theory vs. extended resource theory of marital power

| Resource theory | Extended resource theory | |

|---|---|---|

| Proposition | An individual with more resources relative to his/her partner has more power in marriage. | In addition to an individual’s own resources relative to those of his/her partner, the resources of the individual’s parents relative to his/her partner’s parents increase his/her power in marriage. |

| Concept of resource | A resource may be anything that one partner may make available to the other to satisfy the latter’s needs. | A resource may be anything one partner’s parents make available to the couple to satisfy the couple’s needs. |

| Concept of marriage | A marriage is an intimate relationship involving the two partners. | A marriage joins two partners and their respective natal families. |

| Mechanism | The partner with more resources has the greater potential to dominate and change the other partner’s behaviour by making resources available to the latter. | Parents with more relative resources provide their child with more access to resources outside the marriage and supply their child-in-law with resources that their child-in-law’s parents cannot provide. Hence the partner with more parental resources is less dependent on the marriage and has more power. |

| Resource examples | ||

| Economic | Education, occupation, and personal income of a partner | Financial support and housing assistance provided by a partner’s parents |

| Informational | Information and knowledge provided by a partner | Job information and decision-making advice provided by a partner’s parents |

| Psychological | Interpersonal skills of a partner | Interpersonal skills socialized by a partner’s parents |

| Expressive | Affective, expressive, and sexual companionship provided by a partner | Emotional support provided by a partner’s parents |

| Services | Housework and childcare performed by a partner | Housework and childcare performed by a partner’s parents |

Parents’ contribution to their children’s marriages may take various forms. First, parents may contribute economic resources to the financial foundation for their children’s marriages, such as financial support, dowry, housing assistance, and economic cooperation (Brown, 2009; Zhang, 2009; Li, 2010). Second, parents mobilize their social capital to access valuable informational resources that help improve the status of their children and children-in-law (Coleman, 1988; Kailaheimo-Lönnqvist et al., 2019). For example, parents may introduce their child-in-law to job opportunities (Li, 2010) and advise on financial and other household decisions (Zhang, 2009). Third, parents also provide psychological resources through further socialization. Parents socialize their children with interpersonal skills that help them improve marital communication and achieve their goals in marital negotiations (Benjamin and Sullivan, 1999; Topham, Larson and Holman, 2005). Fourth, parents supply expressive resources that safeguard their children’s emotional well-being in marriage. Parents help their children adjust to marital life, act as a deterrent against maltreatment (Li, 2010), and offer emotional support and provide a refuge in times of marital conflicts (Zhang, 2009). Finally, parents perform various services to meet their children’s needs, such as farm labour (Chen, 2004), housework (Yu, 2014), and childcare (Chen, Liu and Mair, 2011; Yu and Xie, 2018).

Parental resources may influence couples’ decision-making at various stages of marriage, such as living arrangements (Chu, Xie and Yu, 2011), housing (Yu and Cheng, 2022), fertility (Ji et al., 2020), child education (Zeng and Xie, 2014), internal migration, old age support (Giles and Mu, 2007), as well as financial decisions, the focus of this study. Parents living with their child and child-in-law act as allies of their own child in household decision-making, increasing the power of their own child (Liu, Hutchison and Hong, 1973; Szinovacz, 1987). In the Chinese context of generation-based patriarchy, patrilocal residence can compromise the wife’s power (Zuo, 2009; Cheng, 2019). Migrant couples often continue to rely on their parents for financial, emotional, and childcare support but are disadvantaged in access to local support networks (Li, 2006).

The relative resources of the couple’s respective parents affect the balance of decision-making power in the marriage by influencing the couple’s relative level of dependence on the marital relationship. While one’s power resides in the other partner’s dependency, the level of dependency hinges on the availability of alternative resources beyond the marriage (Emerson, 1962; Szinovacz, 1987). Parents serve as an important alternative source of resources outside the marriage. Children with limited resources themselves may obtain essential economic and social resources from their parents (Zhang, 2009). An individual with greater parental resources than his/her partner has access to more resources outside the marriage, is less dependent on the marriage, and thus possesses more power to resist obligations to his/her partner (Szinovacz, 1987; Sabatelli and Shehan, 1993). Furthermore, one may receive more essential support from their parents-in-law with relatively more resources than from their own parents (Kailaheimo-Lönnqvist et al., 2019). For example, in the traditionally patrilocal society of rural China, wives’ parents, who often live in another village, can utilize their social capital to acquire diversified informational resources not available to husbands’ parents and support husbands’ careers (Zhang, 2009; Li, 2010). By providing scarce resources to their child-in-law, parents who possess more relative resources gain appreciation from their child-in-law, thereby enhancing their own child’s power. Conversely, the partner with fewer parental resources than the other may be more dependent on the marriage and have less bargaining power.

Parental education and decision-making power

We apply the extended resource theory framework to examine how relative parental education, as an indicator of relative parental resources, affects marital power above and beyond relative spousal education. The partner whose own parents are more educated than their parents-in-law has access to more parental economic, informational, psychological, and expressive resources described in Table 1. Parental education reflects parents’ ability to provide their children with not only financial support (Lei et al., 2015) but also interpersonal skills, knowledge, experience, and expertise (Furstenberg and Kaplan, 2004), which can help to improve decision-making efficiency and the family’s collective well-being (Zuo and Bian, 2005). Furthermore, parental education is a marker of the natal family’s social status (Katz and Peres, 1985), which conveys community respect and esteem (Foa, 1971). Thus, the high social status of a woman’s natal family offers her more emotional support and ensures against maltreatment by her husband and parents-in-law (Brown, 2009). Educated parents are also more skilled at mobilizing their social capital (Furstenberg and Kaplan, 2004) to acquire privileged informational resources that help enhance their children’s marital power. Education is associated with the quantity, quality, and diversity of parents’ social connections (Astone et al., 1999; Zhang, 2009). Less educated parents tend to have smaller networks that are often confined to close family ties or connections with low levels of education and limited resources. In contrast, highly educated parents tend to have a more extensive scope of contacts beyond kinship networks that can generate greater benefits (Furstenberg, 2005). Men from lower social origins may marry women from higher social origins for the social capital of their wife’s parents (Schwartz, Zeng and Xie, 2016). As discussed earlier, the partner whose own parents have more limited resources than their parents-in-law may be more dependent on the marriage and have less power. Thus, the partner whose own parents are more educated than their parents-in-law may enjoy more parental resources and higher decision-making power.

Admittedly, parental education is only one of the many possible indicators of parental resources. We focus on education for several reasons. First, education is known to be highly correlated with other indicators of social status and to play a critical role in social stratification. In rural China, parental education strongly predicts both monetary and time investments on child development (Brown, 2006). Data on individuals’ education are also widely available in social surveys. Understanding how parental education affects marital power provides important insights into the intergenerational transmission of inequality from the perspective of marital power. Second, both own education and parental education are important considerations in mating (Schwartz, Zeng and Xie, 2016; Cheng and Zhou, 2022). Our study contributes to the knowledge of how assortative mating on parental education and own education affects marital power. Third, we are able to construct comparable measures of the education of spouses and their parents. This allows us to directly compare the effect of relative spousal education and the effect of relative parental education on marital power. Finally, both own education and parental education reach stability before marriage, and thus are not susceptible to reverse causality.

There is evidence from past research in support of our theory in China. Focusing on the relative premarital economic conditions of natal families, prior studies have found that a wife has more decision-making power if the premarital economic conditions of her natal family are better than those of her husband’s natal family (Yang and Zheng, 2013; Qian and Jin, 2018). Although informative, these studies have several limitations. First, age and cohort differences between the couple’s respective parents may confound the association between relative economic conditions of natal families and marital power. Although older parents may accumulate more wealth over longer time spans, younger parents may benefit more from the economic reform and rapid educational expansion (Wu and Zhang, 2010; Xie and Jin, 2015) and may be healthier and more capable of providing instrumental support (Ma and Wen, 2016). Our study adjusts for the dramatic improvement in education in China in recent decades (Treiman, 2013) and the resulting large compositional differences in education by age, cohort, and gender by rescaling education levels into continuous percentile scores using census distributions (Xie and Zhang, 2019; Dong and Xie, 2023). Second, compared to the natal family’s premarital economic conditions, parental education has a clearer comparable measure for the couple, i.e. the couple’s own education, which enables us to test the direct effect of parental resources net of the comparable resources of the couple. The educational percentile scores we constructed allow us to test the direct effect of relative parental education net of relative spousal education and compare the effect of relative spousal education and the effect of relative parental education on marital power.

In summary, we introduce the extended family perspective to the marital power literature that has hitherto focused primarily on individual attributes and nuclear families. We propose an extended resource theory of marital power: the comparative resources of the couple’s respective parents are directly associated with the balance of power in a marriage, net of the comparative resources of the couple themselves. We hypothesize that there is a direct association between the relative education of partners’ parents and partners’ decision-making power. Specifically, the more educated the wife’s parents are relative to her parents-in-law, the more likely it is that she has the final say over household decisions, net of the explanatory power attributable to the relative education of herself and her husband.

Method

Data

We used data from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS), a nationally representative longitudinal biennial survey conducted since 2010 (Xie and Hu, 2014). The survey consists of individual questionnaires for household members and a family questionnaire. We used the 2014 wave because it included questions on household decision-making in the family questionnaire. To construct the analytic sample of married couples, we linked each partner’s questionnaire and the family questionnaire. We restricted the analysis to 3,436 married couples in which both partners were interviewed and lived in the same household,3 the wife was aged 24–44, and the husband was aged 24–60. We limited the couple’s age range to focus on the life stage when a couple is more likely to experience downward transfers from their parents than to provide upward transfers. Of these couples, 36 had missing values on the decision-making outcomes. They were included in the imputation but excluded from the analyses. The final analytic sample consisted of 2,369 couples in which both partners had rural hukou. As discussed earlier, this study focuses on rural households as defined by hukou. Couples of rural hukou are highly interdependent with their natal families with respect to major economic resources such as land and housing (Zhang, 2009; Jiang, Zhang and Sanchez-Barricarte, 2015) and maintain close ties with their natal kin in their home villages even in the case of migration (Li, 2006), providing a unique opportunity to study the influence of the extended family on marital power. Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations was applied to handle missing data; fifty imputations were computed.

Decision-making outcomes

This study measured the balance of decision-making power by whether the wife has the final say on the following household financial decisions: i) household expenditure, ii) savings, investment, and insurance, iii) housing, and iv) purchasing expensive goods (such as refrigerators, air-conditioners, and furniture sets). The four decision outcomes had very high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha =0.9). We also constructed a composite measure of whether the wife has the final say on at least one of the four decisions. The analyses combined households where husbands had the final say with those where another household member had the final say. The results were substantively similar when we restricted the analyses to households where either the wife or the husband had the final say.

Decision-making outcomes were reported by the family respondents. The survey asked the family respondent ‘who has the final say’ on each of the decisions. When choosing the family respondent, the interviewer asked who was the most appropriate person to answer family-level questions, especially those concerning family finances, and chose such a household member aged 18 and over. Of the final analytic sample, 36 per cent of the decision-making outcomes were reported by the wife, 41 per cent by the husband, and 23 per cent by others such as coresident parents. The models controlled for who the respondent was. Prior research suggests that the association between education and decision-making power is similar across husbands’ and wives’ reports, although their reports of who has the final say differ slightly (Chien and Yi, 2014).

The final-say measure denotes a specific power dimension, i.e. overt power outcomes (McDonald, 1980; Komter, 1989). In the CFPS survey interview, the family respondent was instructed to select one final decision-maker from the household members and did not have the option to report that no one had the final say or that household members had an equal say. This measure is thus limited in not allowing for joint decision-making. Collectivized families that value collective well-being tend to make joint decisions through cooperative interactions (Zuo and Bian, 2005). Power may be reflected in the decision-making process, though those participating in the process may not have the final say (Safilios-Rothschild, 1970). This study examines the association between relative parental education and overt power outcomes. Higher relative parental education may also empower spouses in the decision-making process. Our results using the final-say measure shed light on how relative parental education is related to decision-making power.

Measurement of education

The main predictors were the relative education between the wife’s parents and parents-in-law and the relative education between herself and the husband. The relative education between the wife’s parents and parents-in-law reflects marital sorting on parental education, i.e. the extent to which the wife’s parental education differs from the husband’s parental education. The relative education between spouses reflects the degree to which spouses sort on their own education.

To construct relative parental education and relative spousal education, we first rescaled each individual’s education level into a continuous percentile score using Chinese census data (Xie and Zhang, 2019; Dong and Xie, 2023). The education percentile score, theoretically ranging from 0 to 100, is a percentile rank of one’s educational attainment in his/her age-specific, sex-specific birth cohort. Based on census distributions of education by sex and birth year, we constructed the percentile scores as the cumulative percentages of individuals who completed each education level in the population by sex and age minus half of the percentages of individuals at that education level. We used tabulation data from the 1982 Census for the pre-1950 cohorts, the 2000 Census for the 1950–1969 cohorts, the 2010 Census for the 1970–1984 cohorts, and the 2015 one-percent inter-census survey for the post-1985 cohorts.

We constructed the relative education between spouses by subtracting the husband’s education percentile score from the wife’s. The relative education between spouses thus logically ranged from –100 to 100. We constructed the relative education between spouses’ parents by subtracting the husband’s father’s education percentile score from the wife’s father’s. We measured the relative education between spouses’ parents by the relative education between the wife’s father and father-in-law, given the pervasive patriarchal tradition in rural China where the eldest male has the most power (Greenhalgh, 1985; Zuo, 2009). The relative education between spouses’ fathers theoretically ranged from –100 to 100.

The purpose of a percentile score is to purge age and cohort effects on education by obtaining a measure of relative education that is comparable by generation, birth cohort, and gender (Dong and Xie, 2023). This normalization enables us to compare the effect of relative education between spouses’ parents with the effect of the relative education between spouses. Levels of education, however, would not be comparable by generation, birth cohort, and gender given China’s rapid educational expansion and narrowing gender gap in education (Wu and Zhang, 2010; Treiman, 2013). Education percentile scores, standardized by birth cohort and gender, adjust for compositional differences in age and sex among the wife, her husband, her parents, and his parents, thereby facilitating cross-generational comparisons (Zeng and Xie, 2014; Dong and Xie, 2023). For sensitivity analyses, we replicated the models measuring education as the highest level attained and obtained qualitatively similar results.

Covariates

All models controlled for the following variables. First, we controlled for the average education percentile of the couple and that of their fathers. Second, we controlled for couples’ relative individual resources, including income, occupation, homeownership, and migrant status. Relative income was the wife’s annual income divided by the couple’s combined income. We used a spline function with a knot at 0.5 to distinguish the effect of relative income when the wife contributed less than half of the couple’s income and when she contributed more than half (Shu, Zhu and Zhang, 2013; Qian and Jin, 2018), while controlling for the couple’s total income. We measured the couple’s respective occupations by whether they were in professional jobs, their respective homeownership by whether they were listed as owners of their current residence, and their respective migrant status by whether their hukou location was in the same county as their current residence. We also adjusted for the couple’s respective housework hours, as spouses may gain power in routine decisions through housework performance (Zuo and Bian, 2005).

Third, we adjusted for additional indicators of relative parental resources, including whether the couple’s respective parents held professional jobs and communist party memberships.4 We also controlled the wife’s dowry, a form of economic resources from her parents that may increase her power (Brown, 2009). As intergenerational coresidence can alter household power dynamics (Zuo, 2009; Cheng, 2019), we controlled for whether the couple lived with their respective parents. Fourth, we included the following demographic characteristics of the couple and their parents: the wife’s age, the couple’s age difference, the difference between the wife’s age and the mean age of her parents, the difference between the mean age of her parents and parents-in-law, whether either spouse was an ethnic minority, and whether it was the first marriage for both spouses.5 Finally, we controlled for several household characteristics: whether the household was in an urban area, whether it engaged in farm work, whether it engaged in family business, number of the couple’s children in the household, and who the family respondent was (wife, husband, or another household member). To adjust for regional variations in educational opportunities (Wu and Zhang, 2010) and family and gender values (Hu and Scott, 2016), we controlled for the region in which the household was located (North, Northeast, East, South Central, Southwest, or Northwest).

Analytic strategy

We estimated a series of logistic regressions to examine the association between relative parental education and decision-making power. Let Y denote whether the wife has the final say over household financial decisions, WP the wife’s parental education, HP the husband’s parental education, W the wife’s education, and H the husband’s education. X represents a vector of control variables. Assuming Y follows a Bernoulli distribution with probability of success π, we estimated the following logistic models:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

In Model 1, estimates the effect of the relative education between the wife’s parents and parents-in-law on the likelihood of the wife having the final say, net of the mean education of her parents and parents-in-law. In Model 2, estimates the effect of the relative education between the wife and her husband, net of the couple’s mean education. In Model 3, estimates the effect of relative parental education, net of relative spousal education; estimates the effect of relative spousal education, net of relative parental education.

Results

Descriptive results

In Table 2, we present sample outcome distributions; among 34.5 per cent of the couples in the analytic sample, the wife had the final say on at least one of the financial decisions. Among the four financial decisions measured, wives were the least likely to have the final say on housing and more likely to have the final say on household expenditure and expensive purchases. In Supplementary Tables A1 and A2 in Supplementary Appendix, we provide sample distributions of couples’ own and parental education and the covariates, respectively. On average, wives had lower education percentile scores than their husbands; wives’ parents had lower percentile scores than husbands’ parents.

Table 2.

Sample descriptive statistics of decision-making outcomes (N = 2,369)

| Variables | % |

|---|---|

| Wife had the final say on at least one of the following decisions | 34.5 |

| Who had the final say on household expenditure | |

| Wife | 23.3 |

| Husband | 55.2 |

| Other | 21.5 |

| Who had the final say on savings, investment, and insurance | |

| Wife | 21.5 |

| Husband | 59.4 |

| Other | 19.1 |

| Who had the final say on housing | |

| Wife | 17.3 |

| Husband | 64.4 |

| Other | 18.4 |

| Who had the final say on buying expensive consumer goods, such as refrigerators, air-conditioners, and furniture sets | |

| Wife | 27.0 |

| Husband | 56.4 |

| Other | 16.6 |

Note: Numbers were weighted by survey sampling weights to adjust for sampling design and combined across 50 imputations.

Regression results

In Table 3, we present the multivariate logistic regression results. As the first step, Model 1 is intended to examine how the relative education between the wife’s father and father-in-law is associated with the likelihood of the wife having the final say without adjusting for the education of her and her husband. As hypothesized, the more educated the wife’s father was relative to her father-in-law, the more likely it was that she would have the final say. In Model 2, we alternatively focus on the effect of the relative education between the wife and her husband without adjusting for the education of her father and father-in-law. As hypothesized, the more educated the wife was relative to her husband, the more likely it was that she would have the final say.

Table 3.

Logistic regressions of whether wives had the final say over financial decisions (N = 2,369)

| Predictor | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE B) | B (SE B) | B (SE B) | |

| Wife’s father’s education – husband’s father’s education (in percentile score/100) | 0.51* (0.21) |

0.49* (0.21) |

|

| (Wife’s father’s education + husband’s fathers’ education)/2 (in percentile score/100) | 0.08 (0.33) |

0.11 (0.34) |

|

| Wife’s education – husband’s education (in percentile score/100) | 0.83*** (0.25) |

0.80** (0.25) |

|

| (Wife’s education + husband’s education)/2 (in percentile score/100) | –0.11 (0.38) |

–0.16 (0.38) |

|

| Wife’s income share spline | |||

| 50% or less | 0.85 | 0.84 | 0.83 |

| (0.62) | (0.63) | (0.63) | |

| More than 50% | –0.61 | –0.51 | –0.54 |

| (0.73) | (0.73) | (0.73) | |

| Couple’s total income in 10,000 yuan | 0.07* | 0.07* | 0.07* |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.03) | |

| Couple’s occupation (ref. = neither partner in a professional job) | |||

| Only wife is in a professional job | 0.32 | 0.27 | 0.24 |

| (0.31) | (0.32) | (0.32) | |

| Only husband is in a professional job | 0.13 | 0.20 | 0.18 |

| (0.24) | (0.24) | (0.24) | |

| Both partners are in professional jobs | 0.27 | 0.31 | 0.30 |

| (0.47) | (0.49) | (0.48) | |

| Couple’s homeownership (ref. = neither partner is an owner) | |||

| Only wife is an owner | 1.13 | 0.99 | 1.07 |

| (0.64) | (0.62) | (0.64) | |

| Only husband is an owner | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| (0.15) | (0.15) | (0.15) | |

| Both partners are owners | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.17 |

| (0.29) | (0.29) | (0.29) | |

| Couple’s migrant status (ref. = hukou location of both partners is in the same county as the current residence) | |||

| Only wife’s hukou location is in a different county | –0.82 | –0.95* | –0.89* |

| (0.43) | (0.42) | (0.43) | |

| Only husband’s hukou location is in a different county | –1.18* | –1.14 | –1.19* |

| (0.57) | (0.60) | (0.58) | |

| Both partners’ hukou locations are in a different county | –0.90* | –0.85* | –0.89* |

| (0.37) | (0.38) | (0.37) | |

| Couple’s party membership (ref. = neither partner is a party member) | |||

| Only wife is a communist party member | 0.66 | 0.63 | 0.63 |

| (0.83) | (0.85) | (0.84) | |

| Only husband is a communist party member | –0.41 | –0.26 | –0.23 |

| (0.30) | (0.30) | (0.30) | |

| Both partners are communist party members | –1.29 | –1.39 | –1.38 |

| (1.08) | (0.95) | (0.97) | |

| Couple’s parents’ occupationa (ref. = neither partner has parents in professional jobs) | |||

| Only wife has at least one parent with a professional job | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.02 |

| (0.29) | (0.28) | (0.29) | |

| Only husband has at least one parent with a professional job | –0.46 | –0.51 | –0.44 |

| (0.29) | (0.28) | (0.29) | |

| Both partners have at least one parent with a professional job | 0.91* | 0.94* | 0.93* |

| (0.45) | (0.45) | (0.45) | |

| Couple’s parents’ party membershipa (ref. = neither partner has parents who are party members) | |||

| Only wife has at least one parent who is a party member | –0.07 | –0.02 | –0.08 |

| (0.26) | (0.25) | (0.26) | |

| Only husband has at least one parent who is a party member | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.20 |

| (0.24) | (0.24) | (0.24) | |

| Both partners have at least one parent who is a party member | –0.14 | –0.13 | –0.10 |

| (0.53) | (0.55) | (0.54) | |

| Living arrangements of wife’s parents (ref. = both were deceased) | |||

| Either parent of the wife lives in the household | 0.88* | 0.85* | 0.82 |

| (0.43) | (0.43) | (0.43) | |

| Either parent of the wife is alive but neither lives in the household | 0.33 | 0.36 | 0.34 |

| (0.29) | (0.29) | (0.29) | |

| Living arrangements of husband’s parents (ref. = both were deceased) | |||

| Either parent of the husband lives in the same household | –0.16 | –0.12 | –0.13 |

| (0.24) | (0.25) | (0.25) | |

| Either parent of the husband is alive but neither lives in the household | 0.41 | 0.42 | 0.43 |

| (0.23) | (0.23) | (0.23) | |

| Wife’s dowryb | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.20 |

| (0.14) | (0.14) | (0.14) | |

| Wife’s housework hours | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| (0.04) | (0.04) | (0.04) | |

| Husband’s housework hours | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| (0.05) | (0.05) | (0.05) | |

| Wife’s age | 0.06*** | 0.07*** | 0.07*** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| Wife’s age – husband’s age | –0.03 | –0.04 | –0.04 |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| Mean age of wife’s parents when wife was born | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| Mean age of wife’s parents when wife was born – mean age of husbands’ parents when wife was born | –0.01 | –0.01 | –0.01 |

| (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | |

| Either wife or husband is an ethnic minority | –0.24 | –0.21 | –0.22 |

| (0.21) | (0.20) | (0.20) | |

| First marriage for both partners | 0.49 | 0.63 | 0.57 |

| (0.42) | (0.43) | (0.42) | |

| Number of children in the household | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.12 |

| (0.07) | (0.08) | (0.08) | |

| The household is in an urban area | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| (0.15) | (0.15) | (0.15) | |

| The household engages in farm work | –0.12 | –0.10 | –0.12 |

| (0.16) | (0.16) | (0.16) | |

| The household engages in family business | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.21 |

| (0.20) | (0.20) | (0.20) | |

| Family questionnaire is answered by (ref. = wife) | |||

| Husband | –2.03*** | –2.00*** | –2.01*** |

| (0.15) | (0.15) | (0.15) | |

| Other | –2.28*** | –2.29*** | –2.29*** |

| (0.22) | (0.22) | (0.22) | |

| Region where the household is located (ref. = North) | |||

| Northeast | 0.60* | 0.60* | 0.58* |

| (0.26) | (0.26) | (0.26) | |

| East | –0.33 | –0.30 | –0.31 |

| (0.21) | (0.21) | (0.22) | |

| South Central | –0.70*** | –0.67*** | –0.69*** |

| (0.20) | (0.20) | (0.20) | |

| Southwest | –0.28 | –0.31 | –0.30 |

| (0.23) | (0.23) | (0.23) | |

| Northwest | –0.34 | –0.29 | –0.35 |

| (0.29) | (0.30) | (0.30) | |

| Constant | –2.92** | –3.12*** | –3.01** |

| (0.93) | (0.93) | (0.93) | |

Note: Numbers were weighted by survey sampling weights to adjust for sampling design and combined across 50 imputations.

aEach partner’s parental occupation and party membership were measured by whether his/her parents had professional jobs and party membership when he/she was at the age of 14.

bDowry was measured as the square root of the real value in 100 yuan.

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 (two-tailed tests).

In Model 3, our full model, we examine how relative parental education is associated with the wife’s decision-making power, net of relative spousal education. Once relative spousal education was adjusted for, the coefficient of the relative education of the wife’s father and father-in-law was slightly smaller (0.49 vs. 0.51) and remained significant. In other words, the association between relative parental education and the wife’s decision-making power was minimally mediated by relative spousal education. Analogously, once relative parental education was controlled, the coefficient of relative spousal education was slightly smaller (0.80 vs. 0.83) and remained significant. The coefficient of the difference in fathers’ education was about three-fifths of the size of the coefficient of the difference in the couple’s own education (0.49 vs. 0.80).

In Table 4, we provide results for repeating the main analysis of Model 3 by the type of financial decision, denoted as Models 3a to 3e. For each decision type, we observe that the coefficient of the relative education of the wife’s father and father-in-law was positive, suggesting that the more educated the wife’s father was relative to her father-in-law, the more likely it was that the wife would have the final say over household expenditure, savings, housing, or expensive purchases. Furthermore, the coefficients were higher for decisions on savings and housing, suggesting that relative parental education was especially relevant for financial decisions involving larger transactions.

Table 4.

Coefficients from logistic regressions of whether wives had the final say on types of financial decisions: household expenditure, savings/investment/insurance, housing, or expensive purchases (N = 2,369)

| Predictor | Model 3a Any |

Model 3b Household Expenditure |

Model 3c Savings, Investment, Insurance |

Model 3d Housing |

Model 3e Expensive Goods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE B) | B (SE B) | B (SE B) | B (SE B) | B (SE B) | |

| Wife’s father’s education – husband’s father’s education (in percentile score/100) | 0.49* (0.21) |

0.47* (0.23) |

0.69** (0.23) |

0.51* (0.24) |

0.41* (0.21) |

| Wife’s education – husband’s education (in percentile score/100) | 0.80** (0.25) |

0.64* (0.26) |

0.80** (0.28) |

0.89** (0.30) |

0.51* (0.25) |

Note: All models controlled for the mean education of the wife and her husband, the mean education of her father and father-in-law, her income share, the couple’s total income, the couple’s respective occupation, parental occupation, homeownership, migrant status, party membership, parental party membership, and housework hours, living arrangements with her parents and parents-in-law, her dowry, her age and its difference with her husband’s age, mean age of her parents when she was born and its difference with mean age of her husbands’ parents when she was born, whether either spouses was an ethnic minority, whether it was non-first marriage for either spouse, whether the household was in an urban area, whether the household engaged in farm work, whether the household engaged in family business, number of children in the household, who the family respondent was, and the region in which the household was located. Numbers were weighted by survey sampling weights to adjust for sampling design and combined across 50 imputations.

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 (two-tailed tests).

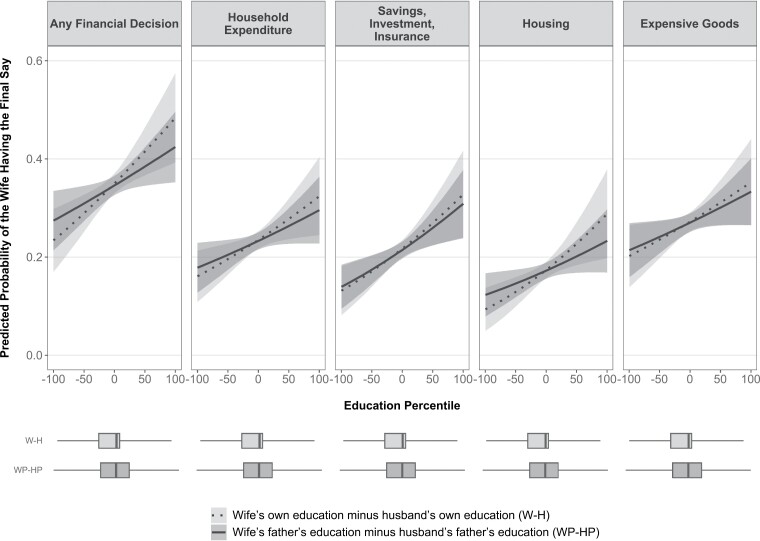

To facilitate the interpretation of these coefficients, we plotted in Figure 1 the predicted probabilities of the wife having the final say by the relative education of her father and father-in-law and the relative education of herself and her husband, derived from Models 3a to 3e in Table 4, alongside boxplots showing the sample distributions of relative spousal education and relative parental education. All else constant, the predicted probability of the wife having the final say over any financial decision was 0.35 when there was no difference in education percentile between her father and father-in-law and between herself and her husband. When the education percentile difference between her father and father-in-law increased by one standard deviation (i.e. when her father’s education percentile was 36 points higher than her father-in-law’s), the predicted probability of her having the final say increased to 0.37. When the education percentile difference between herself and her husband increased by one standard deviation (i.e. when her education percentile was 27 points higher than her husband’s), the predicted probability of her having the final say increased to 0.38. The increase in the probability of the wife having the final say associated with relative parental education was the largest for decisions on savings or investment. The predicted probability of the wife having the final say over savings or investment decisions was 0.21 when the educational percentile difference between her father and father-in-law was zero. When the educational percentile difference between her father and father-in-law increased by one standard deviation, the probability of her having the final say over savings or investment decisions increased to 0.25.

Figure 1.

Predicted probability of the wife having the final say on financial decisions by the difference between the wife’s and the husband’s parental education and the difference between the wife’s and the husband’s own education (N = 2,369) Note: Predicted probabilities were derived from Models 3a to 3e in Table 4. Solid lines plot the predicted probabilities by the difference between the education of the wife’s and the husband’s fathers when all other covariates are at their observed values. Darker grey shaded areas plot the 95-per cent confidence intervals of these probabilities. Dotted lines plot the predicted probabilities by the difference between the wife’s and the husband’s education when all other covariates are at their observed values. Lighter grey shaded areas plot the 95-per cent confidence intervals of these probabilities. The boxplots show the minimum, lower quartile, median, upper quartile, and maximum of relative spousal education and those of relative parental education, respectively. Numbers were weighted by survey sampling weights to adjust for sampling design and combined across 50 imputations. Source: China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) 2014.

Sensitivity analyses

To ensure the robustness of the findings, we further conducted the following sensitivity analyses. First, we added squared terms of relative parental education to examine the potential non-linear association between relative parental education and decision-making power. The squared terms were not significant (results not shown). Second, we included interaction terms between relative parental education and living arrangements to examine whether the association between relative parental education and decision-making power varied by whether the couple lived with the husband’s or the wife’s parents and whether the couple had any living parents. The interactions were not significant (results not shown), suggesting that the association between relative parental education and decision-making power may not be contingent on the physical presence of parents. Educated parents engage in frequent contact and resource transfers with their non-coresident children (Lei et al., 2015). The education of deceased parents may also influence their children’s marital power, since children inherit not only their parents’ wealth and status, but also their values, attitudes, and social connections (Fox, 1973; Glass, Bengtson and Dunham, 1986; Robison, Schmid and Siles, 2002), which can have long-lasting impacts on their lives. Third, we included an interaction term between relative parental education and urban residence to examine whether the association between relative parental education and decision-making power differed by whether couples with rural hukou lived in rural or urban areas. The interaction term was not significant (results not shown). Finally, we included interaction terms between relative parental education and relative spousal education to examine whether marital sorting on parental education and marital sorting on own education affect decision-making power in a multiplicative way. The interactions were not significant (results not shown).

We also tested how the association between relative parental education and decision-making power may vary by different measurements of parental education, as shown in Supplementary Appendix Table A3 in Supplementary Appendix. The relative education between the wife’s mother and mother-in-law, the relative education between her least educated parent and parent-in-law, and the difference in the mean education of her parents and parents-in-law were not associated with her decision-making power. Only the relative education between her father and father-in-law and the relative education between her most educated parent and parent-in-law were associated with her power. The results based on years of education were substantively similar as the results based on percentile scores.

We conducted parallel analyses for couples in which either partner had urban hukou, but did not find a significant association between relative parental education and decision-making power. Supplementary Tables A4 and A5 in the Appendix show the descriptive statistics and regression results of these couples, respectively. The insignificant finding, however, does not necessarily negate the potential effect of relative parental resources on urban couples, as education is only one possible proxy for parental resources. It is possible that urban parents may influence their married children through housing assets, strongly predicted by parents’ income, cadre status, and type of danwei (work units) (Song and Xie, 2014). Limited by available data, we were unable to further explore these possibilities. Prior research based on twelve selected cities in urban China suggests that a wife has more decision-making power if the economic conditions of her natal family are better than those of her husband’s natal family (Qian and Jin, 2018), which lends support to our proposed extended resource theory of marital power.

Conclusion and discussion

An influential sociological theory on gender and family over seven decades, the resource theory of marital power (Blood and Wolfe, 1960) posits that the balance of power in marriage depends on the relative resources each spouse contributes. The partner with more resources gains more power over the other partner by making resources available to the latter. However, the original theory is limited in conceptualizing marriage as an intimate relationship involving only the two partners, with the partners’ individual resources alone as bases of the power bargain. We propose an extended resource theory of marital power that takes into account the extended family context within which the nuclear family is embedded. The marital power bargain involves not just the two partners but also their respective natal families. The resources of the couple’s respective natal families, too, constitute bases of power. Marital power, therefore, is determined not only by the relative resources of spouses but also by the relative resources of spouses’ parents. Parents may provide their child with more access to resources outside the marriage and supply their child-in-law with resources that their child-in-law’s parents cannot readily provide. Hence the partner with more parental resources is less dependent on the marriage and has more power.

Based on the extended resource theory framework, we examine how the relative education of the couple’s respective parents affects the balance of household decision-making power in rural China, net of the relative education of the couple themselves. Results suggest that relative parental education has a direct positive effect on wives’ power. The higher the wife’s parental education relative to her husband’s parental education, the more likely it is that she has the final say over household financial decisions. The effect of relative parental education on decision-making power is not explained away by relative spousal education. Substantively, the effect of relative parental education is more than half of the effect of relative spousal education.

Our results contribute to the study of marital power by introducing a new perspective: the extended family context should be taken into account in understanding marital power. The balance of marital power depends on the relative resources of the couple’s respective parents above and beyond the relative resources of the couple themselves. Furthermore, our findings carry important implications for the study of social stratification, assortative mating, and intergenerational support. Social origins matter not only for children’s attainment of socioeconomic status but also for their power after marriage. Marital sorting on parental backgrounds has significant consequences for the distribution of power in marriage. In light of growing intergenerational contacts, our study, by examining parental influence on children’s marital experience, highlights the consequential implications of intergenerational relationships for adult children’s marital relationships.

The extended resource theory framework points to several directions of future research. In addition to parental education, occupation, and party membership measured in this study, parental income and wealth are also markers of parental socioeconomic status and important mate selection criteria (Charles, Hurst and Killewald, 2013) and may affect marital power. As parents contribute a wide variety of resources to their children’s marriage, future studies may explore how the relative contributions of various resources from parents affect marital power in different ways. Our results suggest that relative parental education is associated with decision-making power, net of the couple’s own education, income, occupation, party membership, homeownership, and migrant status. Future research may examine the underlying mechanisms of how parental socioeconomic status translates into power and how the effect of relative parental education may be mediated through other spousal characteristics. Further work is also needed to consider how parental involvement varies by education and individualistic and familial values. Parents with more individualistic attitudes that value independence may be less involved in their children’s marital life, and their children may be less dependent on parental resources for marital power. While education is associated with more individualistic attitudes (Chen, 2015), educated parents in China are also more invested in their adult children’s well-being (Lei et al., 2015). Future research may explore how the coexistence of individualistic and familial values (Song and Ji, 2020) may modify the effect of relative parental education on marital power.

Our study focused on the final-say measure of decision-making power, which reflects overt power outcomes. When families engage in joint decision-making, power may be reflected in the decision-making process (Safilios-Rothschild, 1970). A partner’s higher relative resources can enhance the representation of his/her personal preferences in joint decisions (Carlsson et al., 2013). Future research may examine how relative parental resources may empower spouses in the joint decision-making process. Another direction for future research is to examine how resources of kin networks beyond parents and parents-in-law may affect marital power. Qualitative work in China suggests that support from natal kin ties can increase women’s power (Zhang, 2009). When conflicts with the husband’s family arise, the wife’s natal kin will intervene, protect, and support her (Li, 2010). Exploring the influence of wider kin networks on marital relationships would further expand the extended resource framework.

The extended resource theory we have proposed in this article underscores the importance of studying marriage not in isolation but within its proper social context and highlights the significance of social origins and intergenerational exchanges for marital power. A marriage joins not just two persons but two sets of natal families. Parental characteristics, in addition to personal characteristics, are considered in marriage decisions. Family decision-making may thus be subject to multigenerational influences. In some societies—such as contemporary China, the site of our study—what constitutes bases of marital power include not only individual attributes but also parental backgrounds. The relative resources between two sets of parents affect marital power dynamics above and beyond the relative resources of the two partners. Women’s status in the family is thus subject to both gender and intergenerational hierarchies. In China, husbands tend to have more influence over major financial decisions, whereas wives have more control over mundane decisions (Shu, Zhu and Zhang, 2013; Yang and Zheng, 2013). However, as our research shows, higher relative parental education enhances wives’ power over financial decisions, especially those decisions involving large transactions, such as housing, savings, and investment. While our study shows how parental resources matter for couples’ financial decisions, other research finds similar evidence of parental influence on couples’ fertility intentions (Ji et al., 2020) and grandchildren’s education (Zeng and Xie, 2014).

In the context of growing intergenerational contacts, our research underscores the need to consider extended family processes in the design of government family policies, such as those related to housing, fertility, child education, and old age support, and in the study of family decision-making and gender inequality.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data are available at ESR online.

Acknowledgements

We thank Sara McLanahan, Noreen Goldman, Margaret Frye, and the audience of our presentations at the ASA 2019 Meeting and the RC28 2019 Summer Meeting for helpful comments on earlier versions of this article, as well as Chunni Zhang for help on Chinese census data on education.

Footnotes

The classic exchange theory in sociology was later reinforced by theoretical work in family economics that focused on specialization between spouses in a nuclear family setting (Becker, 1991).

In this article, one’s natal family refers to their biological or adoptive parents, as opposed to their parents-in-law, who are related to them through marriage.

Decision-making patterns in households where couples lived apart were reported by Zuo (2008). In households comprising multiple couples, such as multigenerational households of older parents and married children, we selected the youngest couple as defined by the wife’s age, given our primary interest in how parental resources influence the younger generation’s decision-making power. In our sample, both partners of a couple were CFPS gene members, i.e. family members identified at baseline to have blood/marital/adoptive ties with the household.

The 2012 wave of CFPS asked what the respondent’s parents’ occupation and party membership were when the respondent was 14.

The CFPS collected information on respondents’ sibship size at the 2010 baseline. As a robustness check, we further controlled for each partner’s sibship size. Our results remained robust, and the coefficients for each partner’s sibship size were not significant (results not shown).

Contributor Information

Cheng Cheng, School of Social Sciences, Singapore Management University, 10 Canning Rise Level 5, Singapore 179873, Singapore.

Yu Xie, Department of Sociology and the Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544, USA.

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in Peking University Open Research Data Platform, at https://doi.org/10.18170/DVN/45LCSO.

Funding

This work was supported by The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P2CHD047879. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Astone, N. M. et al. (1999). Family demography, social theory, and investment in social capital. Population and Development Review, 25, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, G. S. (1991). A Treatise on the Family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson, V. L. (2001). Beyond the nuclear family: the increasing importance of multigenerational bonds. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, O. and Sullivan, O. (1999). Relational resources, gender consciousness and possibilities of change in marital relationships. The Sociological Review, 47, 794–820. [Google Scholar]

- Bittman, M. et al. (2003). When does gender trump money? Bargaining and time in household work. American Journal of Sociology, 109, 186–214. [Google Scholar]

- Blood, R. O. and Wolfe, D. M. (1960). Husbands & Wives: The Dynamics of Married Living. Glencoe, IL: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg, R. L. and Coleman, M. T. (1989). A theoretical look at the gender balance of power in the American couple. Journal of Family Issues, 10, 225–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brines, J. (1994). Economic dependency, gender, and the division of labor at home. American Journal of Sociology, 100, 652–688. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, P. H. (2006). Parental education and investment in children’s human capital in rural China. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 54, 759–789. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, P. H. (2009). Dowry and intrahousehold bargaining. Journal of Human Resources, 44, 25–46. [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson, F. et al. (2013). The influence of spouses on household decision making under risk: An experiment in rural China. Experimental Economics, 16, 383–401. [Google Scholar]

- Charles, K. K., Hurst, E. and Killewald, A. (2013). Marital sorting and parental wealth. Demography, 50, 51–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F. (2004). The division of labor between generations of women in rural China. Social Science Research, 33, 557–580. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R. (2015). Weaving individualism into collectivism: Chinese adults’ evolving relationship and family values. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 46, 167–179. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F., Liu, G. and Mair, C. A. (2011). Intergenerational ties in context: Grandparents caring for grandchildren in China. Social Forces, 90, 571–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, C. (2019). Women’s education, intergenerational coresidence, and household decision‐making in China. Journal of Marriage and Family, 81, 115–132. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, C. and Zhou, Y. (2022). Wealth accumulation by hypogamy in own and parental education in China. Journal of Marriage and Family, 84, 570–591. [Google Scholar]

- Chien, W. and Yi, C. (2014). Marital power structure in two Chinese societies: measurement and mechanisms. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 45, 93–111. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, C. Y. C., Xie, Y. and Yu, R. R. (2011). Coresidence with elderly parents: a comparative study of Southeast China and Taiwan. Journal of Marriage and Family, 73, 120–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, S95–S120. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, H. and Xie, Y. (2023). Trends in educational assortative marriage in China over the past century. Demography, 60, 123–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, R. M. (1962). Power-dependence relations. American Sociological Review, 27, 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Foa, U. G. (1971). Interpersonal and economic resources. Science, 171, 345–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox, G. L. (1973). Another look at the comparative resources model: assessing the balance of power in Turkish marriages. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 35, 718–730. [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg, F. F. (2005). Banking on families: how families generate and distribute social capital. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 809–821. [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg, F. F. and Kaplan, S. B. (2004). Social capital and the family. In: Scott, J., Treas, J. and Richards, M. (Eds.), The Blackwell Companion to the Sociology of Families. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, pp. 218–232. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, J. and Mu, R. (2007). Elderly parent health and the migration decisions of adult children: evidence from rural China. Demography, 44, 265–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass, J., Bengtson, V. L. and Dunham, C. C. (1986). Attitude similarity in three-generation families: Socialization, status inheritance, or reciprocal influence? American Sociological Review, 51, 685–698. [Google Scholar]

- Goode, W. J. (1963). World Revolution and Family Patterns. New York: Free Press of Glencoe. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh, S. (1985). Sexual stratification: the other side of ‘growth with equity’ in East Asia. Population and Development Review, 11, 265–265. [Google Scholar]

- Gruijters, R. J. (2017). Intergenerational contact in Chinese families: structural and cultural explanations. Journal of Marriage and Family, 79, 758–768. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H. (2010). Trends in educational assortative marriage in China from 1970 to 2000. Demographic Research, 22, 733–770. [Google Scholar]

- Helms, H. M. (2013). Marital relationships in the twenty-first century. In: Peterson, G. W. and Bush, K. R. (Eds.), Handbook of Marriage and the Family. Boston: Springer, pp. 233–254. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y. (2016). Marriage of matching doors: marital sorting on parental background in China. Demographic Research, 35, 557–580. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y. and Scott, J. (2016). Family and gender values in China: generational, geographic, and gender differences. Journal of Family Issues, 37, 1267–1293. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, A. L. (1988). Evolution and Human Kinship. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Y. et al. (2020). Young women’s fertility intentions and the emerging bilateral family system under China’s two-child family planning policy. China Review, 20, 113–142. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Q., Zhang, Y. and Sánchez-Barricarte, J. J. (2015). Marriage expenses in rural China. China Review, 15, 207–236. [Google Scholar]

- Kailaheimo-Lönnqvist, S. et al. (2019). Behind every successful (wo)man is a successful parent-in-law? The association between resources of the partner’s parents and individual’s occupational attainment. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 64, 100438–100438. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, R. and Peres, Y. (1985). Is resource theory equally applicable to wives and husbands? Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Killewald, A. and Gough, M. (2010). Money isn’t everything: Wives’ earnings and housework time. Social Science Research, 39, 987–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klesment, M. and Van Bavel, J. (2022). Women’s relative resources and couples’ gender balance in financial decision-making. European Sociological Review, 38, 739–753. [Google Scholar]

- Komter, A. (1989). Hidden power in marriage. Gender & Society, 3, 187–216. [Google Scholar]

- Kulik, L. (1999). Marital power relations, resources and gender role ideology: a multivariate model for assessing effects. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 30, 189–206. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, X. et al. (2015). Living arrangements of the elderly in China: evidence from the CHARLS national baseline. China Economic Journal, 8, 191–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, B. (2006). Floating population or urban citizens? Status, social provision and circumstances of rural–urban migrants in China. Social Policy & Administration, 40, 174–195. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. (2010). Niangjia and Pojia: Women’s Living Space and Backstage Power in a North China Village. Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press China. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W. T., Hutchison, I. W. and Hong, L. K. (1973). Conjugal power and decision making: a methodological note on cross-cultural study of the family. American Journal of Sociology, 79, 84–98. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, S. and Wen, F. (2016). Who coresides with parents? An analysis based on sibling comparative advantage. Demography, 53, 623–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, G. W. (1980). Family power: the assessment of a decade of theory and research, 1970-1979. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 42, 841–854. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, Z. and Xie, Y. (2014). Marital age homogamy in China: a reversal of trend in the reform era? Social Science Research, 44, 141–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nye, F. I. (1980). Family mini theories as special instances of choice and exchange theory. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 42, 479–479. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, Y. and Jin, Y. (2018). Women’s fertility autonomy in urban China: the role of couple dynamics under the universal two-child policy. Chinese Sociological Review, 50, 275–309. [Google Scholar]

- Robison, L. J., Schmid, A. A. and Siles, M. E. (2002). Is social capital really capital? Review of Social Economy, 60, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatelli, R. M. and Shehan, C. L. (1993). Exchange and resource theories. In: Boss, P. G., et al. (Eds.), Sourcebook of Family Theories and Methods. New York: Plenum Press, pp. 385–417. [Google Scholar]

- Safilios-Rothschild, C. (1970). The study of family power structure: a review 1960-1969. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 32, 539–552. [Google Scholar]

- Safilios-Rothschild, C. (1976). A macro- and micro-examination of family power and love: an exchange model. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 38, 355–362. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, C. R., Zeng, Z. and Xie, Y. (2016). Marrying up by marrying down: status exchange between social origin and education in the United States. Sociological Science, 3, 1003–1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu, X., Zhu, Y. and Zhang, Z. (2013). Patriarchy, resources, and specialization: marital decision-making power in urban China. Journal of Family Issues, 34, 885–917. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein, M., Cong, Z. and Li, S. (2006). Intergenerational transfers and living arrangements of older people in rural China: consequences for psychological well-being. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 61, S256–S266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song, J. and Ji, Y. (2020). Complexity of Chinese family life: individualism, familism, and gender. China Review, 20, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X. and Mare, R. D. (2019). Shared lifetimes, multigenerational exposure, and educational mobility. Demography, 56, 891–916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song, X. and Xie, Y. (2014). Market transition theory revisited: changing regimes of housing inequality in China, 1988-2002. Sociological Science, 1, 277–291. [Google Scholar]

- Szinovacz, M. E. (1987). Family power. In: Sussman, M. B. and Steinmetz, S. K. (Eds.), Handbook of Marriage and the Family. New York: Plenum Press, pp. 651–693. [Google Scholar]

- Tanskanen, A. O. and Danielsbacka, M. (2018). Intergenerational Family Relations: An Evolutionary Social Science Approach. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Thibaut, J. W. and Kelley, H. H. (1959). The Social Psychology of Groups. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, A. and Lin, H.-S. (1994). Social Change and the Family in Taiwan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]