Abstract

Although alphaviruses have been extensively studied as model systems for the structural organization of enveloped viruses, no structures exist for the phylogenetically distinct eastern equine encephalomyelitis (EEE)-Venezuelan equine encephalomyelitis (VEE) lineage of New World alphaviruses. Here we report the 25-Å structure of VEE virus, obtained from electron cryomicroscopy and image reconstruction. The envelope spike glycoproteins of VEE virus have a T=4 icosahedral arrangement, similar to that observed in Old World Sindbis, Semliki Forest, and Ross River alphaviruses. However, VEE virus has pronounced differences in its nucleocapsid structure relative to nucleocapsid structures repeatedly observed in Old World alphaviruses.

Alphaviruses (family Togaviridae) can be partitioned into several major phylogenetic lineages or serocomplexes. The eastern equine encephalomyelitis (EEE) and Venezuelan equine encephalomyelitis (VEE) lineages are sisters and are restricted to the New World, while the Sindbis-like (with the exception of Aura), Semliki Forest (with the exception of Mayaro and Una), Barmah Forest, Middelburg, and Ndumu lineages occur in the Old World (2, 16, 17). Each lineage is associated with a characteristic pathogenicity, with infections by EEE-VEE lineage viruses a leading cause of viral encephalitis in humans and horses in the Americas (6). The molecular determinants responsible for this phylogenetically dependent pathogenicity are unknown.

Alphaviruses are small enveloped viruses (6, 12) that package an ∼11.5-kb, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA genome. The viral genome encodes four nonstructural (nsP1, nsP2, nsP3, and nsP4) and five structural (capsid, E1, E2, E3, and 6k) proteins. This relatively simple protein composition has made alphaviruses model systems ideal for studying enveloped virus assembly and structure (3, 6, 9, 13). Electron cryomicroscopy and image reconstruction of Sindbis, Semliki Forest, Ross River, and Aura viruses show that the envelope glycoproteins are arranged on the outer surface of the virus as 80 trimers in a T=4 icosahedral lattice (3, 5, 9, 10, 15, 18). The capsid proteins form a T=4 icosahedral nucleocapsid and are arranged into distinct pentameric and hexameric capsomeres on the exterior of the nucleocapsid (3, 9, 10). The envelope and nucleocapsid structures are separated by a lipid bilayer and likely interact through specific one-to-one interactions between the capsid protein and the membrane-spanning tail of the E2 glycoprotein (7, 9, 14, 19). All currently known alphavirus structures are from the Aura-Sindbis and Semliki Forest-Ross River lineages (termed Old World lineage) and show very similar envelope and nucleocapsid organization.

In this paper, we report the three-dimensional structure of VEE virus, a New World virus from the EEE-VEE virus lineage, determined using electron cryomicroscopy and image reconstruction. Comparison of the VEE and Sindbis viruses showed that their envelope glycoproteins were arranged similarly. However, the capsomere orientations within the VEE and Sindbis virus nucleocapsids were different, implying that alphavirus structures may differ according to their major phylogenetic lineages.

Purification, electron cryomicroscopy, and image reconstruction of Sindbis and VEE viruses.

The structure of the Sindbis virus was obtained from previous studies (9), with three-dimensional image reconstructions performed using the cross-common-line method (4). The Sindbis virus structure was reconstructed with data truncated to 25 Å, with this resolution determined using a value of 0.5 in the Fourier shell correlation coefficient method. This structure was used in all comparisons with the VEE virus structure.

The TC-83 attenuated vaccine strain of VEE virus was a generous gift from R. Shope and R. Tesh (Arbovirus Reference Center collection, University of Texas Medical Branch). The TC-83 strain differs from its virulent parent, Trinidad donkey VEE virus, by single-amino-acid changes in the nsP4 and E1 proteins and 5-amino-acid changes in the E2 protein (8). Baby hamster kidney cells were grown to confluency and were inoculated with virus at a multiplicity of approximately 1.0. Infected cells were incubated at 37°C for ∼2 days until cytopathic effects appeared; then the supernatant was pooled and centrifuged for 10 min at 5,000 × g to remove cellular debris. The virus was concentrated by precipitation with 7% polyethylene glycol 8000 and 2.3% NaCl at 4°C for 8 to 16 h and was gently resuspended in TN buffer (20 mM triethanolamine, pH 7.4, and 100 mM NaCl). Following centrifugation at 6,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C, the resuspended pellet was purified by centrifugation through a 20 to 70% continuous sucrose gradient for 60 min at 270,000 × g. Fractions containing the visible virus band were pelleted through a 30% sucrose cushion for 120 min at 270,000 × g and were resuspended in TN buffer.

Purified VEE virus was applied to carbon-coated fenestrated grids, flash cooled in a liquid ethane slush to preserve the sample in vitreous ice, and transferred into a JEOL 1200 electron cryomicroscope. Virus images were recorded at 100 kV using flood beam imaging and a nominal magnification of ×30,000. To prevent specimen damage from electron irradiation, the illumination of the specimen with the beam was limited to five to seven electrons/Å2 per image. Two images per specimen area were recorded, with the first image being closer to 1.0-μm defocus and the second being closer to 2.0-μm defocus. Reconstruction utilized hierarchical wavelet transformation and projection matching to determine initial orientations as described previously (11). Previously determined Sindbis virus reconstructions were used to generate the initial projections needed for the projection matching protocol. VEE virus reconstructions were used in subsequent iterative cycles of orientation refinement using the Fourier cross-common-line procedure, which was then used in the final image reconstruction.

To ensure accurate comparisons of the VEE and Sindbis virus structures, both structures were reconstructed at equivalent resolutions (1). The final VEE virus structure was reconstructed to 25 Å. Resolution was determined by the Fourier shell correlation coefficient where a value of 0.5 was used to assign the resolution limit.

Structure of VEE virus.

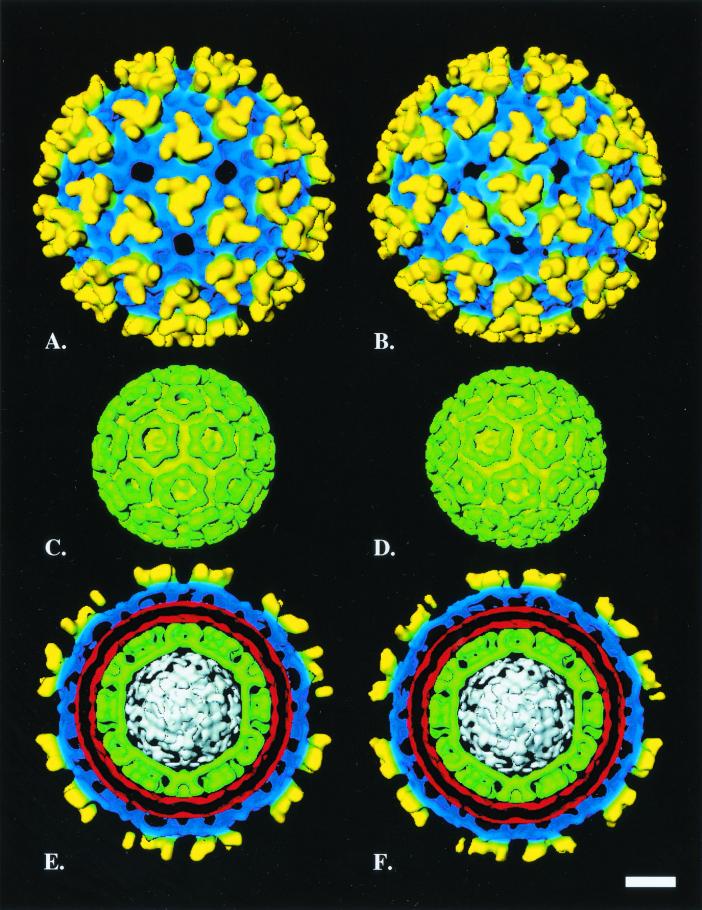

X-ray solution scattering data for VEE virus and micrographs of tobacco mosaic virus were both used to accurately determine the magnification of the electron cryomicroscope and the pixel size of the digitized electron micrographs (data not shown). Based on this calibration, the diameter of VEE virus was calculated as 684 Å, in agreement with the diameter of Sindbis virus (9). The VEE virus structure was composed of 80 envelope protein trimers on the surface of the virion. Each trimer formed part of a series of overlapping pentameric and hexameric capsomeres arranged on a T=4 icosahedral lattice (Fig. 1A). Similar arrangements of the envelope glycoproteins were observed for Sindbis virus (Fig. 1B) and other published alphavirus structures (3, 9, 10, 15, 18). The envelope trimers had the characteristic counterclockwise twisted hand typical of all alphaviruses and rose ∼50 Å above the envelope protein planar skirt (denoted by blue regions in Fig. 1). All trimers had an outer diameter of ∼139 Å, with their tips separated from one another by ∼107 Å.

FIG. 1.

Structure of VEE and Sindbis viruses as determined by image reconstructions of electron micrographs. (A) Isosurface view along a threefold axis of the VEE virus reconstruction. Yellow indicates the outer spike trimers, and blue indicates the skirt region of the envelope. (B) Isosurface view along a threefold axis of the Sindbis virus reconstruction. Yellow indicates the outer spike trimers, and blue indicates the skirt region of the envelope. (C) Isosurface representation of VEE virus nucleocapsid viewed along a threefold-symmetry axis. (D) Isosurface representation of Sindbis virus nucleocapsid viewed along a threefold-symmetry axis. (E) Cross-section through VEE virus perpendicular to the threefold axis and in plane with a vertical fivefold axis. The structural components of the virus are color-coded: yellow indicates the trimers, blue indicates the skirt region, red indicates the virus membrane, green indicates the nucleocapsid, and white indicates the RNA genome. (F) Cross-section through Sindbis virus perpendicular to the threefold axis and in plane with a vertical fivefold axis. The structural components of the virus are color-coded: yellow indicates the trimers, blue indicates the skirt region, red indicates the virus membrane, green indicates the nucleocapsid, and white indicates the RNA genome. Scale bar corresponds to 100 Å.

The radial distributions of the structural proteins were similar in both VEE and Sindbis viruses (Fig. 1E and F). In both structures, the envelope skirt was ∼50 Å thick and its outer edge was situated at a radius of 294 Å. The envelope skirt was adjacent to the outer leaflet of the virus membrane. The ∼40-Å virus membrane occupied the region between a radius of 201 and 240 Å and separated the nucleocapsid from the envelope of the virus.

The capsid proteins forming the surface of the VEE and Sindbis virus nucleocapsids were arranged as both pentameric and hexameric capsomeres on a T=4 icosahedral lattice (Fig. 1C and D). The nucleocapsids of both VEE and Sindbis viruses were ∼392 Å in diameter. The capsid protein making up the nucleocapsid structure measured ∼60 Å thick and extended inward to a radius of 136 Å. The inner tier of the nucleocapsid, composed of the capsid N-terminal region (CNR; residues 1 to ∼115) complexed with viral RNA, adopted a similar shape in both the VEE and Sindbis viruses. Although this region was difficult to observe through rendering, radial density plots examining several VEE and Sindbis virus maps indicated that this region extended down to a radius of ∼125 Å. As shown in the cross-sections normal to the threefold axis of the icosahedral reconstructions, the inner tier of the nucleocapsid had a distinct polyhedral outline in the VEE and Sindbis viruses (Fig. 1E and F). The CNR complexed with bound RNA likely adopted an extended planar structure in the icosahedral sides that bound the nucleocapsid inner tier. The remainder of the virus core is believed composed of the RNA genome.

Differences in nucleocapsids of VEE and Sindbis viruses.

The envelope glycoprotein surfaces of VEE and Sindbis viruses overlapped extensively when superimposed, demonstrating that their structures and orientations were similar at the resolution of these reconstructions (data not shown). In addition, the agreement in their surface structures demonstrated that no systematic errors were preferentially propagated in either of these reconstructions.

Unexpectedly, the nucleocapsid surfaces of VEE and Sindbis viruses did not overlap when superimposed on one another (Fig. 2). Pronounced differences in the VEE and Sindbis virus nucleocapsid capsomere orientations and structure were observed (Fig. 1C and D). Reconstructions of VEE virus at different resolutions and from data collected on different electron cryomicroscopes operating at different accelerating voltages were calculated (data not shown) and were compared to all the published nucleocapsid structures before we concluded that the differences between the Sindbis and VEE virus nucleocapsid structures were consistent, significant, and real. Since TC-83 and wild-type VEE virus capsid proteins have identical primary structures, their tertiary and quaternary structures will likewise be identical. Thus, the wild-type VEE virus will likely have the same nucleocapsid capsomere arrangement observed for the TC-83 VEE virus.

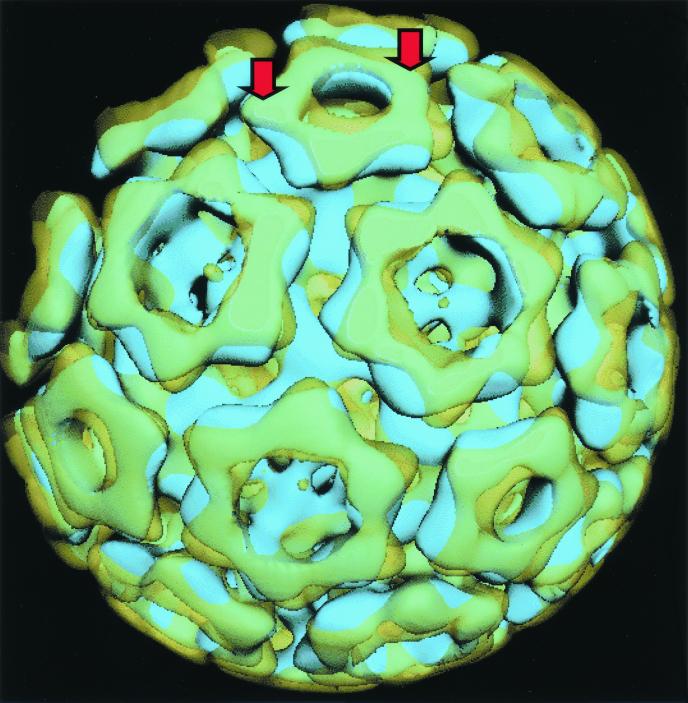

FIG. 2.

Superposition of isosurfaces of nucleocapsids from VEE (yellow) and Sindbis (blue) viruses showing the different orientations of their pentameric and hexameric capsomeres. Arrows indicate the positions of representative CCD proteins within the capsomeres.

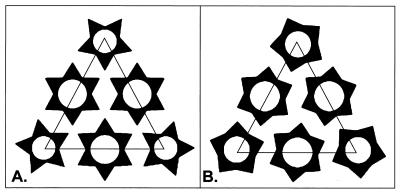

The pentameric and hexameric capsomeres that formed the VEE virus nucleocapsid were rotated counterclockwise ∼11 and ∼4°, respectively, relative to the corresponding Sindbis virus capsomeres. Comparable rotational differences were observed when higher-resolution reconstructions of the Sindbis virus structure were compared to the VEE virus structure. The triangular projections that comprise the outer ring structure of the nucleocapsid capsomeres (indicated by arrows in Fig. 2) are believed to correspond to the capsid C-terminal domain (CCD) (3, 9). The organization of these domains in VEE virus was symmetrically directed towards one another, giving the nucleocapsid a mirrored, symmetrical appearance from the tip of the fivefold capsomere to the strict threefold axis (Fig. 3A). As a result, the VEE virus CCDs appeared organized about threefold axes at all junctions of three mutually adjacent capsomeres (Fig. 1C and 3A). In contrast to the VEE virus capsomere arrangement, adjacent Sindbis virus capsomeres adopted a gearlike arrangement whereby the triangular projection of one capsomere was directed towards an indentation on an adjacent capsomere (Fig. 1D and 3B). The relative positioning of the Sindbis virus CCDs differed at the different capsomere junctions, with only pseudothreefold symmetry maintained at junctions between one pentameric and two hexameric capsomeres (Fig. 3B). Thus, regions of the capsid protein involved in intercapsomeric contacts will likely be different for VEE and Sindbis viruses.

FIG. 3.

Schematic representation of capsomere organization within a triangular face of the nucleocapsid icosahedral structure. The small triangular elements within each capsomere represent CCD molecules. (A) Pentameric and hexameric capsomere organization within the nucleocapsid of VEE virus. (B) Pentameric and hexameric capsomere organization within the nucleocapsid of the Sindbis virus.

To determine how symmetrical the strict threefold and quasithreefold trimers were, sections normal to these trimers were isolated, cross-correlation coefficients were calculated between each section and the same section rotated 120° about the normal axis of symmetry. As expected, the strict threefold positions demonstrated threefold symmetry with correlation coefficients of ∼0.9. In addition, both viruses had correlation coefficients of ∼0.9 at the quasithreefold positions of the envelope trimers that extended outwards from the envelope skirt region. The correlation coefficient dropped to ∼0.65 at the quasithreefold positions occupied by the Sindbis virus CCD, while the correlation coefficient was >0.9 for the corresponding region of VEE virus. Comparison of these structures showed that the quasithreefold positions in the Sindbis virus nucleocapsid were disrupted by an inherent handedness or skew of the CCD structure. In contrast to Sindbis virus, the threefold arrangement of VEE virus capsid proteins closely mirrored the organization of the trimeric envelope proteins on the virus surface. This arrangement implies a one-to-one interaction between envelope and capsid proteins and suggests that capsid trimers may mediate nucleocapsid assembly either as nucleation structures or by cross-linking capsomeres.

The capsomere triangular projections were more pronounced in VEE virus than in the Sindbis virus (Fig. 2B). The electron density connecting these projections within the VEE virus capsomeres was weaker than within the Sindbis virus capsomeres. These observations suggested that capsid protein orientations and intermolecular contacts may be different in VEE and Sindbis viruses. Approximately 65% of the residues proposed to form intermolecular CCD contacts within Old World alphavirus capsomeres (3, 4, 9) were found conserved in VEE virus. Similar levels of sequence conservation were calculated for CCDs from VEE and Old World alphaviruses (Table 1), implying that putative intracapsomere CCD contacts were not perferentially conserved and thus may not be necessary for capsomere assembly.

TABLE 1.

Amino acid sequence identity between alphavirus structural proteinsa

| Virus | Identity with:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VEE | Sindbis | Semliki Forest | Ross River | Aura | |

| VEE | 51/40/54b | 52/37/56b | 53/39/51b | 50/40/56b | |

| Sindbis | 34/58/47c | 50/40/44b | 50/42/44b | 62/57/59b | |

| Semliki Forest | 35/63/51c | 42/67/56c | 78/68/71b | 48/38/53b | |

| Ross River | 33/62/49c | 39/66/55c | 64/91/80c | 48/39/51b | |

| Aura | 33/54/47c | 56/76/68c | 41/63/55c | 40/63/52c | |

Protein sequences were obtained from Swiss-Protein database entries and correspond to the VEE (strain TC-83; accession number P05674), Sindbis (strain HRSP; accession number P03316), Semliki Forest (accession number P03315), Ross River (strain NB5092; accession number P13890), and Aura (accession number Q86925) viruses.

These values represent percent amino acid identify from separate best-fit pairwise alignments (W. Pearson, www.ch.embnet.org/software/LALIGN_form.html) of the E1, E2, and E3 proteins.

These values represent percent amino acid identify from separate best-fit pairwise alignments (W. Pearson, www.ch.embnet.org/software/LALIGN_form.html) of the CNR (residues 1 to ∼115), CCD, and the complete capsid protein.

Divergence of alphavirus structural proteins.

The Old World Sindbis, Semliki Forest, and Ross River alphaviruses have homologous structures. In contrast, the phylogenetically distinct New World VEE virus has pronounced differences in its nucleocapsid structure relative to nucleocapsid structures repeatedly observed in Old World alphaviruses. This structural divergence likely arose from lineage-dependent differences that evolved long ago in the component protein and/or RNA structures. Sequence comparisons between alphavirus structural proteins (Table 1) showed that the E1 glycoprotein and the CCD were highly conserved and thus may adopt similar structures. In contrast, the E2 glycoprotein and the CNR had limited sequence conservation between alphaviruses and may adopt different structures. The E2 glycoprotein of Ross River virus had sequence identity similar to that of the E2 glycoprotein of VEE and Sindbis viruses, while the CNR of Ross River virus was more closely related to Sindbis virus than to VEE virus. Thus, the structure of the CNR may be lineage dependent and ultimately responsible for the nucleocapsid structural differences observed between phylogenetically distinct alphaviruses. The secondary and tertiary structure of the viral RNA may also contribute to the observed nucleocapsid structural differences. Additional structural studies of New World alphaviruses will help determine if the observed nucleocapsid capsomere orientations are related to either the encephalitic potential of these viruses or to their association with common reservoir vectors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the John Sealy Memorial Endowment Fund for Biomedical Research (2551-99, S. J. Watowich), the National Center for Macromolecular Imaging (P41R02250, W. Chiu), Robert Welch Foundation (Q-1242, W. Chiu), National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID; T32-AI 07471, A. Paredes), and the Sealy Center for Structural Biology (University of Texas Medical Branch).

We thank V. Popov and M. Kunkel for assistance with electron microscopy of negative-stained particles; R. Shope, B. V. V. Prasad, S. Ludtke, and J. Brink for helpful discussions; R. E. Johnston, D. Brown, and H. Heidner for access to the Sindbis virus structure; A. McGough for providing tobacco mosaic virus for magnification calibration; and M. Baker and W. Jiang for assistance in determining the cross-correlation coefficients of the strict and quasithreefold trimer positions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baker T S, Olson N H, Fuller S D. Adding a third dimension to virus life cycles: three-dimensional reconstructions of icosahedral viruses from cryo-electron micrographs. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:862–922. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.4.862-922.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calisher C H, Karabatsos N. Arbovirus serogroups: definition and geographic distribution. In: Monath T P, editor. The arboviruses: epidemiology and ecology. Vol. 1. Boca Raton, Flo: CRC Press; 1988. pp. 19–57. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng R H, Kuhn R J, Olson N H, Rossmann M G, Choi H-K, Smith T J, Baker T S. Nucleocapsid and glycoprotein organization in an enveloped virus. Cell. 1995;80:621–630. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90516-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi H-K, Lu G, Lee S, Wengler G, Rossmann M G. Structure of Semliki Forest virus core protein. Proteins Struct Func Genet. 1997;27:345–359. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(199703)27:3<345::aid-prot3>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fuller S D. The T=4 envelope of Sindbis virus is organized by interactions with a complementary T=3 capsid. Cell. 1987;48:923–934. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90701-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnston R E, Peters C J. Alphaviruses. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 843–898. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kail M, Hollingshead M, Ansorge W, Pepperkok R, Frank R, Griffiths G, Vaux D. The cytoplasmic domain of alphavirus E2 glycoprotein contains a short linear recognition signal required for viral budding. EMBO J. 1991;10:2343–2351. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07773.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kinney R M, Johnson B J B, Welch J B, Tsuchiya K R, Trent D W. The full-length nucleotide sequences of the virulent Trinidad Donkey strain of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus and its attenuated vaccine derivative, TC-83. Virology. 1989;170:19–30. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90347-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mancini E J, Clarke M, Gowen B E, Rutten T, Fuller S D. Cryo-electron microscopy reveals the functional organization of an enveloped virus, Semliki Forest virus. Mol Cell. 2000;5:255–266. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paredes A M, Brown D T, Rothnagal R, Chiu W, Schoepp R, Johnston R E, Prasad V. Three-dimensional structure of a membrane-containing virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9095–9099. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.9095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saad A, Zhou Z H, Jakana J, Chiu W, Rixon F J. Roles of triplex and scaffolding proteins in herpes simplex virus type 1 capsid formation suggested by structures of recombinant particles. J Virol. 1999;73:6821–6830. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.8.6821-6830.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schlesinger S, Schlesinger M J. Togaviridae: the viruses and their replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 825–841. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strauss J H, Strauss E G. The alphaviruses: gene expression, replication, and evolution. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:491–562. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.3.491-562.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suomalainen M, Liljestrom P, Garoff H. Spike protein-nucleocapsid interactions drive the budding of alphaviruses. J Virol. 1992;66:4737–4747. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.8.4737-4747.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vogel R H, Provencher S W, von Bonsdorff C H, Adrian M, Dubochet J. Envelope structure of Semliki Forest virus reconstructed from cryo-electron micrographs. Nature. 1986;320:533–535. doi: 10.1038/320533a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weaver S C, Dalgarno L, Frey T K, Huang H V, Kinney R M, Rice C M, Roehrig J T, Shope R E, Strauss E G. Family Togaviridae. In: van Regenmortel M H V, Fauquet C M, Bishop D H L, Carstens E B, Estes M K, Lemon S M, Maniloff J, Mayo M A, McGeogh D J, Pringle C R, Wickner R B, editors. Virus taxonomy: classification and nomenclature of viruses. Seventh report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 2000. pp. 879–889. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weaver S C, Kang W, Shirako Y, Rümenapf T, Strauss E G, Strauss J H. Recombinational history and molecular evolution of western equine encephalomyelitis complex alphaviruses. J Virol. 1997;71:613–623. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.613-623.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang W, Olson N, McKinney B, Kuhn R, Baker T. Cryo-electron microscopy of aura viruses. Proc Microsc Microanal. 1998;4:946–947. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao H, Lindqvist B, Garoff H, von Bonsdorff C-H, Liljestrom P. A tyrosine-based motif in the cytoplasmic domain of the alphavirus envelope protein is essential for budding. EMBO J. 1994;13:4204–4211. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06740.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]