Abstract

Trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) has emerged as a newly identified gut microbiota-dependent metabolite contributing to a variety of diseases, such as diabetes, atherosclerosis, and cardiovascular diseases. The aim of our study was to determine whether a relatively high TMAO level is associated with an increased risk of poor outcome in ischemic stroke patients. From June 2018 to December 2018, we prospectively recruited acute ischemic stroke patients diagnosed within 24 h of symptom onset. The plasma TMAO level was measured at admission for all patients. Functional outcome was evaluated at 3 months after the stroke using the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) and then dichotomized as favorable (mRS 0–2) or unfavorable (mRS 3–6). A multivariate logistic regression analysis was conducted to evaluate the association between TMAO concentration and poor functional outcome and mortality at 3 months. Of the 225 acute ischemic stroke patients included in the analysis, the median TMAO concentration was 3.8 µM (interquartile range, 1.9–4.8 µM). At 3 months after admission, poor functional outcome was observed in 116 patients (51.6%), and 51 patients had died (22.7%). After adjusting for potential confounders, patients with TMAO levels in the highest quartile were more likely to have higher risks of poor functional outcome [compared with the lowest quartile, odds ratio (OR) 3.63; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.34–9.82; P = 0.011] and mortality (OR 4.27; 95% CI 1.07–17.07; P = 0.040). Our data suggest that a high plasma TMAO level upon admission may predict unfavorable clinical outcomes in acute ischemic stroke patients.

Keywords: Trimethylamine N-oxide, Gut microbiota-dependent metabolite, Clinical outcome, Ischemic stroke

Introduction

Ischemic stroke is the major cause of acquired adult disability and mortality in China (Bonita et al. 2004; Liu et al. 2007). There are approximately 1.5 to 2 million newly diagnosed and recurrent strokes each year, causing a tremendous burden on health resources (Liu et al. 2011). Accordingly, an early risk assessment with an estimate of disease severity and prognosis is crucial in providing effective interventions and allocating health care resources to improve stroke outcomes.

Gut microbes impact human health and diseases, at least in part, by metabolizing dietary and host-derived substrates and generating biologically active compounds such as signaling compounds, biological precursors, and toxins (Clemente et al. 2012; Tremaroli and Bäckhed 2012; Dinan and Cryan 2017). Trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) is an oxidized metabolite mediated by the gut microbial metabolism of choline-containing lipids and carnitine-based molecules (Wang et al. 2011; Craciun and Balskus 2012; Tang et al. 2013). Numerous prospective clinical studies have demonstrated that TMAO is predictive of adverse cardiovascular events, including myocardial infarction, stroke, and death (Tang et al. 2013; Schiattarella et al. 2017; Haghikia et al. 2018). More recently, TMAO has been reported to enhance thrombosis potential with induced platelet hyperreactivity, linking increased levels of circulating TMAO to a potential increased risk of an acute ischemic event (Zhu et al. 2016). Additionally, basic science evidence indicates that high TMAO levels in the brain may increase oxidative stress, induce mitochondrial dysfunction, and inhibit mTOR signaling, all of which may contribute to neurological function impairment (Li et al. 2018). To date, the relationship between circulating TMAO concentration and stroke outcome has not yet been specifically detected. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess whether the circulating TMAO level can predict 3-month clinical outcomes in patients with acute ischemic stroke.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

From June 2018 to December 2018, we conducted a prospective cohort investigation enrolling acute ischemic stroke patients who were admitted within 24 h after the onset of symptoms. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) age less than 18 years; (2) pre-onset modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score more than 2; (3) usage of antibiotics and probiotics for less than 1 month after stroke; and (4) presence of malignant tumor, autoimmune disease, immunosuppressive therapy, active or chronic inflammatory disorders, severe renal disease, and hepatic disease. We also excluded subjects who underwent intravenous thrombolysis and endovascular therapy after admission. Informed consent was obtained from participants or legal representatives, and the protocol was approved by the ethical committee of the Affiliated Huai’an Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University.

Baseline Data Collection

Baseline data were recorded, including age, sex, comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and coronary heart disease), smoking status, previous stroke, pre-stroke mRS, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, body mass index, stroke severity, and stroke subtype. Stroke severity was assessed by a certified neurologist using the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) (Goldstein and Samsa 1997). Each patient was classified into one of four stroke subtype categories as specified in the Trial of the ORG 10172 in the Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) study: large artery atherosclerosis, cardioembolism, small vessel occlusion, and stroke of other determined or undetermined etiology (Adams et al. 1993). The volume of the infarction was estimated by the DWI-based Alberta Stroke Program Early CT (DWI-ASPECT) score. The DWI-ASPECT score was dichotomized as 0–7 versus 8–10 (de Margerie-Mellon et al. 2013). Laboratory data, including fasting plasma glucose (FPG), hypersensitive C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), homocysteine, and lipid profile results, were also recorded.

TMAO Concentration Assessment

After informed consent was obtained, blood samples were collected in EDTA tubes from all patients. The specimens were centrifuged at 1500×g for 10 min, and the isolated plasma was frozen at − 80 °C for further analysis. As previously described (Wang et al. 2011, 2014), plasma TMAO levels were quantified by stable-isotope dilution liquid chromatography with online tandem mass spectrometry using an 8050 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, Columbia, MD, USA).

End Points and Follow-Up

The follow-up determination of the mRS at 3 months was implemented through telephonic conversations or outpatient visits by one investigator who was blinded to the clinical data. According to previous studies (Duan et al. 2018; Tóth et al. 2018), poor functional outcome was defined as a mRS of 3–6. The secondary end point was death at 3 months.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical significance was established at P values < 0.05. Differences in baseline characteristics between the TMAO level quartiles were determined using the Chi square test or Fisher’s exact test, analysis of variance, or the Kruskal–Wallis test where appropriate. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to describe TMAO concentration as a potential predictive factor for poor functional outcome and mortality. The area under the curve (AUC) was calculated based on the ROC curves. We also performed a binary logistic regression analysis to evaluate the possible contributing factors to unfavorable outcomes at 3 months after ischemic stroke. Variables with statistically significant associations at P < 0.1 in univariate analyses were forced into the multivariate analysis. The results were calculated as adjusted odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results

In all, 225 consecutively admitted patients (55.1% male; mean age, 68.5 years) with acute ischemic stroke confirmed by clinical diagnosis and brain CT results were included for the final analysis. Among these patients, 68.9% had hypertension, 28.0% had diabetes mellitus, and 11.1% had hyperlipidemia. For clinical outcomes at 3 months, poor functional outcome and mortality were 51.6% and 22.7%, respectively.

The median TMAO level was 3.8 μM at admission, with quartile levels as follows: < 1.9 μM (first quartile), 1.9–3.7 μM (second quartile), 3.8–4.8 μM (third quartile), and > 4.8 μM (fourth quartile). The baseline data of the 225 patients according to TMAO quartiles are presented in Table 1. Increasing quartile of TMAO was associated with hypertension (P = 0.030), coronary heart disease (P = 0.042), poor functional outcome (P = 0.012) and mortality (P = 0.001) at 3 months, higher level of body mass index (P = 0.027), and homocysteine levels (P = 0.018).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the ischemic stroke patients according to TMAO quartile

| Variables | First quartile (n = 56) | Second quartile (n = 56) | Third quartile (n = 56) | Fourth quartile (n = 57) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |||||

| Age, years | 66.5 ± 11.2 | 67.9 ± 10.3 | 69.5 ± 10.0 | 70.0 ± 8.9 | 0.238 |

| Male sex (%) | 33 (58.9) | 30 (53.6) | 29 (51.8) | 32 (56.1) | 0.883 |

| Vascular risk factors (%) | |||||

| Hypertension | 30 (53.6) | 39 (69.6) | 42 (75.0) | 44 (77.2) | 0.030 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 13 (23.2) | 11 (19.6) | 19 (33.9) | 19 (33.3) | 0.223 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 8 (14.3) | 6 (10.9) | 4 (7.1) | 7 (12.3) | 0.673 |

| Coronary heart disease | 3 (5.4) | 6 (10.9) | 10 (17.9) | 13 (22.8) | 0.042 |

| History of stroke | 5 (8.9) | 5 (8.9) | 6 (10.7) | 12 (12.1) | 0.151 |

| Current smoking | 18 (32.1) | 24 (44.4) | 21 (37.5) | 20 (35.1) | 0.586 |

| Clinical data | |||||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 131.4 ± 18.4 | 137.9 ± 20.1 | 139.4 ± 18.0 | 140.4 ± 19.9 | 0.165 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 85.0 ± 14.2 | 87.5 ± 15.0 | 89.5 ± 14.3 | 87.2 ± 17.2 | 0.863 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.1 ± 3.0 | 23.2 ± 3.2 | 23.5 ± 3.5 | 24.8 ± 3.6 | 0.027 |

| NIHSS score | 5.0 (4.0, 9.0) | 5.0 (3.0, 8.0) | 7.0 (3.0, 11.0) | 7.0 (4.0, 11.5) | 0.132 |

| DWI-ASPECT 0–7a (%) | 20 (37.7) | 26 (50.0) | 30 (54.5) | 34 (64.2) | 0.053 |

| Stroke subtypes (%) | 0.658 | ||||

| Large artery atherosclerosis | 16 (28.6) | 14 (25.0) | 21 (37.5) | 24 (42.1) | |

| Cardioembolism | 16 (28.6) | 13 (23.2) | 12 (21.4) | 11 (19.3) | |

| Small artery occlusion | 14 (25.0) | 20 (35.7) | 16 (28.6) | 16 (28.1) | |

| Others | 10 (7.9) | 9 (16.1) | 7 (12.5) | 6 (10.5) | |

| Laboratory data | |||||

| Hs-CRP (mg/L) | 7.5 (2.4, 15.5) | 5.1 (2.3, 12.1) | 5.3 (2.3, 10.5) | 5.2 (2.5, 12.0) | 0.538 |

| Fasting blood-glucose (mmol/L) | 6.3 ± 1.5 | 5.9 ± 2.5 | 6.7 ± 2.4 | 6.8 ± 2.9 | 0.242 |

| Homocysteine (mmol/L) | 12.9 ± 5.0 | 12.1 ± 3.1 | 15.4 ± 3.7 | 14.2 ± 5.8 | 0.018 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.1 ± 1.0 | 4.4 ± 1.0 | 4.3 ± 1.4 | 4.5 ± 1.3 | 0.213 |

| Triglyceride (mmol/L) | 1.2 (1.0, 1.9) | 1.2 (0.8, 1.7) | 1.1 (0.8, 1.8) | 1.5 (0.9, 1.9) | 0.361 |

| Low-density lipoprotein (mmol/L) | 2.4 (1.8, 2.9) | 2.7 (2.2, 3.2) | 2.4 (2.0, 3.2) | 2.8 (2.0, 3.8) | 0.060 |

| High-density lipoprotein (mmol/L) | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 0.300 |

| Clinical outcomes at 3 months (%) | |||||

| Unfavorable functional outcome | 20 (35.7) | 26 (46.4) | 34 (60.7) | 36 (63.2) | 0.012 |

| Mortality | 6 (10.7) | 9 (16.1) | 13 (23.2) | 23 (40.4) | 0.001 |

Hs-CRP hypersensitive C-reactive protein, NIHSS National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

aData available for 213 patients

Table 2 summarizes the results of the binary logistic regression of the clinical outcomes. Univariate logistic regression analysis demonstrated that the highest quartile of TMAO level (using the lowest quartile as the reference value) was identified as a prognostic marker of unfavorable functional outcome [OR 3.09; 95% CI 1.45–6.65; P = 0.004] and mortality (OR 5.64; 95% CI 2.08–15.30; P = 0.001). Furthermore, this association remained highly significant in the multivariable model adjusted for demographic characteristics, hypertension, coronary heart disease, body mass index, NIHSS score, stroke subtypes, homocysteine, and low-density lipoprotein levels.

Table 2.

Logistic regression analyses of the association between TMAO levels and clinical outcomes

| OR (95% CI) for 3-month unfavorable functional outcome | P value | OR (95% CI) for 3-month mortality | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted model | ||||

| TMAO level | ||||

| First quartile | Reference | Reference | ||

| Second quartile | 1.56 (0.73–3.33) | 0.250 | 1.60 (0.53–4.83) | 0.408 |

| Third quartile | 2.78 (1.29–5.98) | 0.009 | 2.52 (0.88–7.20) | 0.084 |

| Fourth quartile | 3.09 (1.43– 6.65) | 0.004 | 5.64 (2.08–15.30) | 0.001 |

| Adjusted model | ||||

| TMAO level | ||||

| First quartile | Reference | Reference | ||

| Second quartile | 2.01 (0.79–5.11) | 0.143 | 1.43 (0.34–6.05) | 0.627 |

| Third quartile | 2.65 (0.96–7.34) | 0.061 | 1.89 (0.48–7.39) | 0.320 |

| Fourth quartile | 3.63 (1.34–9.82) | 0.011 | 4.27 (1.07– 17.07) | 0.040 |

The multivariate model was adjusted for demographic characteristics, hypertension, coronary heart disease, body mass index, NIHSS score, DWI-ASPECT score 0–7, stroke subtypes, and homocysteine and low-density lipoprotein levels

Based on the ROC curve, the optimal TMAO level cut-off value for predicting an unfavorable outcome was estimated to be 3.9 µM, which yielded a sensitivity of 60.3%, a specificity of 65.1%, and an AUC of 0.63 (95% CI 0.56–0.70). Additionally, the optimal TMAO level cut-off value for predicting mortality was projected to be 4.0 µM, which yielded a sensitivity of 64.1%, a specificity of 61.5%, and an AUC of 0.69 (95% CI 0.60–0.77).

Discussion

In this prospective clinical study, we tested the hypothesis that the plasma concentration of TMAO was associated with clinical outcomes in patients with acute ischemic stroke. The key finding in our study was the dose-dependent association of plasma TMAO level with unfavorable functional outcome and mortality at 3 months. Furthermore, these associations remained robust after adjusting for traditional risk factors, including body mass index, NIHSS score, stroke subtypes, homocysteine levels, and low-density lipoprotein levels, in the multivariate logistic analysis.

TMAO is a gut microbiota-dependent metabolite of dietary trimethylamines. The production of TMAO involves a two-step process. First, gut microbes enzymatically generate trimethylamine from dietary constituents such as choline or carnitine (Craciun and Balskus 2012). TMA then enters the circulation and is oxidized to TMAO in the liver by flavin-containing monooxygenase (Wang et al. 2011). It is now believed that TMAO is a potentially important mediator of the pathogenesis of atherosclerotic disease and the occurrence of major atherothrombotic complications, such as stroke and myocardial infarction (Bennett et al. 2013; Tang et al. 2013; Wilson et al. 2016). Although nutrition has always been linked to the outcomes of cardiovascular patients, the pivotal role of the gut microbiome and its metabolites has only recently been recognized in ischemic stroke. Nie et al. demonstrated that higher TMAO levels may portend an increased risk of first-ever stroke in hypertensive patients, even after adjustment for choline, L-carnitine, and other important covariates, including baseline SBP and time-averaged SBP during the treatment period (Nie et al. 2018). More recently, another study found that, in patients with carotid artery stenting (CAS), increased TMAO levels were associated with an increased risk of new ischemic brain lesions on post-CAS MRI scans (Wu et al. 2018). These studies add to the growing body of data demonstrating that TMAO level may serve as a clinically useful and potentially modifiable prognostic marker in ischemic stroke, even beyond the currently used risk factors and laboratory testing. To the best of our knowledge, our study was the first to assess the relationship between TMAO level and short-term functional outcome in Chinese patients after acute ischemic stroke. Importantly, this preliminary result confirmed an interesting conclusion: an elevated TMAO level at admission was correlated with a poor functional outcome and mortality at 3 months, indicating that a disturbance in this biomarker was prognostically unfavorable.

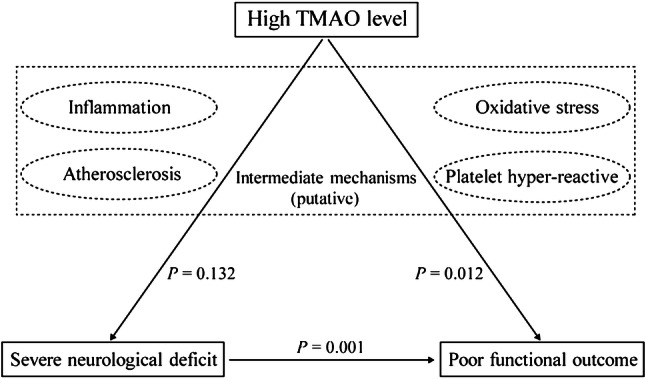

The potential biological mechanisms underlying the deleterious effects of TMAO level on stroke outcome are outlined in Fig. 1. This observation might be partly explained by activating inflammatory status that plays a crucial role in the development and propagation of stroke (Wang et al. 2007; Siniscalchi et al. 2016). Previous studies have advanced the notion that the physiological level of TMAO can induce the expression of inflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules and activate the NLRP3 inflammasome (Seldin et al. 2016; Boini et al. 2017; Chen et al. 2017), which are all involved in the disruption of the blood–brain barrier and neuronal regeneration (Yang et al. 2019). Thus, higher circulating TMAO levels may reflect ongoing inflammatory processes and lead to poor outcomes after ischemic stroke. Furthermore, a recent study in animal models and healthy volunteers has demonstrated that increasing TMAO is directly involved in enhancing platelet reactivity (Zhu et al. 2016). Given the detrimental impact of platelet hyperreactivity on stroke severity and clinical outcome in patients with cardiovascular diseases (Angiolillo et al. 2007; Schwammenthal et al. 2008), we proposed that increased TMAO levels may induce poor functional outcomes by modulating platelet function in cerebrovascular disorders. However, platelet function was not evaluated in our study. More detailed studies are required to determine the mechanism underlying the adverse impact of TMAO levels on functional outcome after ischemic stroke.

Fig. 1.

Putative mechanisms for the association of high TMAO level with severe neurological deficit and poor functional outcome. P values are indicated for the measured associations in our study. Putative intermediate mechanisms are shown in the middle of the figure with dashed lines

The strengths of this study lie in the strict inclusion criteria, the relatively large, homogeneous patient series, and the prospective design. Nevertheless, this study has several limitations. First, the study was performed in one stroke center. This selection bias would probably reduce the power of the study. In addition, as a single-center observational cohort, these findings need to be replicated in other validation cohorts. Second, our measurement method was not able to reflect potentially dynamic changes in the TMAO level. Further studies are needed to assess how TMAO levels change over time after stroke and whether the level drawn at later points provides improved prognostic information. Finally, we were unable to control for postdischarge medication that might have impacted the clinical outcomes. Therefore, the interpretation of our data must be done cautiously.

In summary, our study demonstrated that plasma TMAO levels at admission were independently associated with clinical outcomes in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Further longitudinal studies are needed to comprehensively detect these associations to verify whether a diet-induced reduction in TMAO levels could be beneficial for acute stroke patients.

Acknowledgements

We also express our gratitude to all the researchers and patients who participated in this study.

Author Contributions

QZ: designed the study, conducted the statistical analysis, and wrote the draft of the manuscript. XW: conducted the statistical analysis and acquired data. CC: conducted the statistical analysis and acquired data. YT: acquired data. YW: acquired data. TJ: revised the manuscript. YZ: conducted the statistical analysis and supervised this study. XL: conceived and designed the study, conducted the statistical analysis, and supervised this study.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Affiliated Huai’an Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University. The study was carried out according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from participants or legal representatives.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Qijin Zhai, Xiang Wang, and Chun Chen have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Ying Zhao, Phone: +86 0517-80871790, Email: yingzhao613321@163.com.

Xinfeng Liu, Phone: +86 2584801861, Email: xfliu2@vip.163.com.

References

- Adams HP Jr, Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ, Biller J, Love BB, Gordon DL, Marsh EE 3rd (1993) Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Stroke 24:35–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angiolillo D, Bernardo E, Sabaté M, Jimenez-Quevedo P, Costa M, Palazuelos J, Hernández-Antolin R, Moreno R, Escaned J, Alfonso F, Bañuelos C, Guzman L, Bass T, Macaya C, Fernandez-Ortiz A (2007) Impact of platelet reactivity on cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 50:1541–1547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett B, de Aguiar Vallim T, Wang Z, Shih D, Meng Y, Gregory J, Allayee H, Lee R, Graham M, Crooke R, Edwards P, Hazen S, Lusis A (2013) Trimethylamine-N-oxide, a metabolite associated with atherosclerosis, exhibits complex genetic and dietary regulation. Cell Metab 17:49–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boini K, Hussain T, Li P, Koka S (2017) Trimethylamine-N-oxide instigates NLRP3 inflammasome activation and endothelial dysfunction. Cell Physiol Biochem 44:152–162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonita R, Mendis S, Truelsen T, Bogousslavsky J, Toole J, Yatsu F (2004) The global stroke initiative. Lancet Neurol 3:391–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Zhu X, Ran L, Lang H, Yi L, Mi M (2017) Trimethylamine-N-oxide induces vascular inflammation by activating the NLRP3 inflammasome through the SIRT3-SOD2-mtROS signaling pathway. J Am Heart Assoc 6:e006347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemente J, Ursell L, Parfrey L, Knight R (2012) The impact of the gut microbiota on human health: an integrative view. Cell 148:1258–1270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craciun S, Balskus E (2012) Microbial conversion of choline to trimethylamine requires a glycyl radical enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:21307–21312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Margerie-Mellon C, Turc G, Tisserand M, Naggara O, Calvet D, Legrand L, Meder JF, Mas JL, Baron JC, Oppenheim C (2013) Can DWI-ASPECTS substitute for lesion volume in acute stroke? Stroke 44:3565–3567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinan T, Cryan J (2017) Gut instincts: microbiota as a key regulator of brain development, ageing and neurodegeneration. J Physiol 595:489–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Z, Wang H, Wang Z, Hao Y, Zi W, Yang D, Zhou Z, Liu W, Lin M, Shi Z, Lv P, Wan Y, Xu G, Xiong Y, Zhu W, Liu X (2018) Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio predicts functional and safety outcomes after endovascular treatment for acute ischemic stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis 45:221–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein L, Samsa G (1997) Reliability of the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale. Extension to non-neurologists in the context of a clinical trial. Stroke 28:307–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haghikia A, Li X, Liman T, Bledau N, Schmidt D, Zimmermann F, Kränkel N, Widera C, Sonnenschein K, Haghikia A, Weissenborn K, Fraccarollo D, Heimesaat M, Bauersachs J, Wang Z, Zhu W, Bavendiek U, Hazen S, Endres M, Landmesser U (2018) Gut Microbiota-dependent trimethylamine N-oxide predicts risk of cardiovascular events in patients with stroke and is related to proinflammatory monocytes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 38:2225–2235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Ke Y, Zhan R, Liu C, Zhao M, Zeng A, Shi X, Ji L, Cheng S, Pan B, Zheng L, Hong H (2018) Trimethylamine-N-oxide promotes brain aging and cognitive impairment in mice. Aging Cell 17:e12768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Wu B, Wang W, Lee L, Zhang S, Kong L (2007) Stroke in China: epidemiology, prevention, and management strategies. Lancet Neurol 6:456–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Wang D, Wong K, Wang Y (2011) Stroke and stroke care in China: huge burden, significant workload, and a national priority. Stroke 42:3651–3654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie J, Xie L, Zhao B, Li Y, Qiu B, Zhu F, Li G, He M, Wang Y, Wang B, Liu S, Zhang H, Guo H, Cai Y, Huo Y, Hou F, Xu X, Qin X (2018) Serum trimethylamine N-oxide concentration is positively associated with first stroke in hypertensive patients. Stroke 49:2021–2028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiattarella G, Sannino A, Toscano E, Giugliano G, Gargiulo G, Franzone A, Trimarco B, Esposito G, Perrino C (2017) Gut microbe-generated metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide as cardiovascular risk biomarker: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Eur Heart J 38:2948–2956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwammenthal Y, Tsabari R, Shenkman B, Schwartz R, Matetzky S, Lubetsky A, Orion D, Israeli-Korn S, Chapman J, Savion N, Varon D, Tanne D (2008) Aspirin responsiveness in acute brain ischaemia: association with stroke severity and clinical outcome. Cerebrovasc Dis 25:355–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seldin M, Meng Y, Qi H, Zhu W, Wang Z, Hazen S, Lusis A, Shih D (2016) Trimethylamine N-oxide promotes vascular inflammation through signaling of mitogen-activated protein kinase and nuclear factor-κB. J Am Heart Assoc 5:e002767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siniscalchi A, Iannacchero R, Anticoli S, Pezzella F, De Sarro G, Gallelli L (2016) Anti-inflammatory strategies in stroke: a potential therapeutic target. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 14:98–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W, Wang Z, Levison B, Koeth R, Britt E, Fu X, Wu Y, Hazen S (2013) Intestinal microbial metabolism of phosphatidylcholine and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med 368:1575–1584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tóth N, Székely E, Czuriga-Kovács K, Sarkady F, Nagy O, Lánczi L, Berényi E, Fekete K, Fekete I, Csiba L, Bagoly Z (2018) Elevated Factor VIII and von Willebrand factor levels predict unfavorable outcome in stroke patients treated with intravenous thrombolysis. Front Neurol 8:721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremaroli V, Bäckhed F (2012) Functional interactions between the gut microbiota and host metabolism. Nature 489:242–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Tang X, Yenari M (2007) The inflammatory response in stroke. J Neuroimmunol 184:53–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Klipfell E, Bennett B, Koeth R, Levison B, Dugar B, Feldstein A, Britt E, Fu X, Chung Y, Wu Y, Schauer P, Smith J, Allayee H, Tang W, DiDonato J, Lusis A, Hazen S (2011) Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature 472:57–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Levison B, Hazen J, Donahue L, Li X, Hazen S (2014) Measurement of trimethylamine-N-oxide by stable isotope dilution liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem 455:35–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson A, McLean C, Kim R (2016) Trimethylamine-N-oxide: a link between the gut microbiome, bile acid metabolism, and atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol 27:148–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Li C, Zhao W, Xie N, Yan F, Lian Y, Zhou L, Xu X, Liang Y, Wang L, Ren M (2018) Elevated trimethylamine N-oxide related to ischemic brain lesions after carotid artery stenting. Neurology 90:e1283–e1290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Hawkins K, Doré S, Candelario-Jalil E (2019) Neuroinflammatory mechanisms of blood–brain barrier damage in ischemic stroke. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 316:C135–C153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W, Gregory J, Org E, Buffa J, Gupta N, Wang Z, Li L, Fu X, Wu Y, Mehrabian M, Sartor R, McIntyre T, Silverstein R, Tang W, DiDonato J, Brown J, Lusis A, Hazen S (2016) Gut microbial metabolite TMAO enhances platelet hyperreactivity and thrombosis risk. Cell 165:111–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]